Archive for the 'Narrative strategies' Category

Five critics, one of them a killer

Goodfellas (1990).

DB here:

Fourteen months of being house-bound gave me plenty of chance to catch up on my reading. But the reading was almost all devoted to the book I was writing on mystery plots in fiction, film, and other media. Now that it has been catapulted out to unwary publisher’s readers, it’s time for me to catch up on some 2020 books I like. In this batch, all have a connection to film criticism, and murder, attempted or consummated, creeps into more than one.

Movies for Muggles

Somebody ought to write a history of the one-movie monograph. Early on there were picture books, and roadshow attractions often produced pretty laminated books as souvenirs, filled with PR stories and color images. My vote for the first analytical monograph would be the very ambitious Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima! (1962). In the early 1970s, American academic presses began offering critical studies of single films; an early example was the FilmGuide series edited by Harry Geduld and Ron Gottesman. (My favorite entry was Jim Naremore‘s study of Psycho.) Since then many publishers have pursued the format, usually as part of a series.

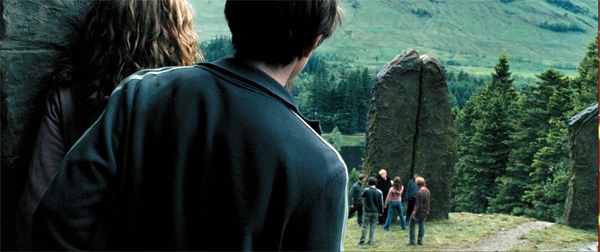

Now we have 21st Century Film Essentials, newly launched at the University of Texas Press. The first two entries are pretty canon-busting. Dana Polan writes on The Lego Movie, and Patrick Keating on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. I haven’t seen Polan’s book, but Keating directly takes up the challenge of the series.

As a franchise film, as a work of digital cinema, as a work of collaborative authorship, and above all as a thoroughly engaging demonstration of the art of storytelling, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is an essential work of twentieth-first century cinema.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

Keating’s argument for the film’s richness, I think, revolves around two central concepts. First is that of narrative viewpoint. Virtually all of Azkaban, unlike the earlier entries in the franchise, is filtered through the consciousness of Harry. We’re attached to him as he experiences the action. That doesn’t, Keating hastens to add, make the film radically subjective; indeed, there are relatively few shots from Harry’s optical viewpoint. Attaching the unfolding plot to a character doesn’t rule out a wider perspective, if only because cinema puts him within a wider frame of a shot or an edited sequence. There’s always the possibility of our registering action or other characters’ reactions. The end of the Quidditch flight is thick with these impacted viewpoints, and elsewhere Cuarón’s constantly moving camera nudges us toward implications that supplement, or sometimes contradict, what Harry is concentrating on.

Keating’s other main concept is connected to the broadening of viewpoint: worldbuilding. This idea is obviously central to Rowling’s achievement, as it has been to franchises since Star Wars. But Keating lifts the idea to a central role in how films engage us. The richly realized world of Potter is only an extreme instance of what every narrative does. Borrowing from critic V. F. Perkins, Keating suggests that any film narrative supplies us with the possibility of many stories that are only hinted at, or merely latent.

Most movies prune those secondary offshoots, the better to force us to concentrate on our protagonist. But Tom Stoppard showed that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern deserved their own play. Similarly, franchise films, with the ever-present prospect of sequels, crossovers, or reboots, make us aware that any character, even any item of furniture, secretes a new story, or a bunch of them. The Potter films are committed to this spinoff aesthetic, packing in as many suggestions of sidestories as the screen will bear. This principle finds tangible expression in the portraits jammed into the Gryffindor common room and dorms guarded by the Fat Lady.

Overwhelming us with characters and situations, many in motion, this gallery is perfectly in keeping with English traditions of floor-to-ceiling decor. It’s also a groaning feast of other stories that could yet, somehow, intersect with Harry’s fate. Keating’s shrewd commentary on worldmaking is one of the book’s highlights.

Keating ties these ideas to phases of production and division of labor, reviewing how the novel’s viewpoint and worldbuilding strategies are transposed and extended by script, camerawork, editing, performances, set and costume design, and music. Throughout he weaves what he takes to be the film’s binding theme, that of time. Is the future preordained, as Ms. Trelawney insists in her frantic, fumbling lectures? Or is it open, as Hermoine and others tell Harry? This makes the film’s tour de force climax with the Time Turner into a synthesis of restricted viewpoint (we’re with Harry as he witnesses an alternative future) and worldbuilding (the future is what you make it).

I might quarrel with Keating’s suggestion that the impulse driving Harry’s action is a struggle with the dementers. I saw his relation to Sirius Black as more than the subplot Keating considers it. Overall, though, Keating has produced not only a subtle, supple analysis of the film but also a model for how to understand cinematic storytelling in the age of the blockbuster.

Wiseguy’s progress

If Keating’s book is a classical sonata, Glenn Kenny’s Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas is bop. Keating offers a tidy analysis through crisply defined categories. Kenny provides a hardcopy approximation to a packed DVD.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

It’s overwhelming. Kenny has evidently read everything about the real-life sources of the story, and his interviews turn fan service toward crime reporting. It is no small thing to pursue hard cases who were recruited for bit parts. Kenny has also garnered a lot of information from staff like AD Joseph Reidy, who are seldom given much attention. Keating would probably be happy to see Kenny’s narrative splinter into stories leading to other stories, such as the effects of the film on the careers of Barbara De Fina and Ileanna Douglas.

I compared the book’s central chapter to a DVD commentary. Anybody delivering a voice-over play-by-play regrets that you have to keep up with the film and can’t devote as much time to a big scene as you might like. Thanks to the print format, Kenny is able to pause the film and spiral out from it to fill in backstory or behind-the-scenes dynamics.

Early on, he can give us three pages on Tuddy, both his original (who died in prison) and Frank DiLeo, the actor playing the role. Kenny explains that DiLeo was a music executive who oversaw Michael Jackson’s “Bad” video, which included a Wanted poster of Scorsese in a subway scene, which ties to a sneaky reference to the “Smooth Criminal” video featuring a character named Frank Lideo, played by Joe Pesci. . . well, you get the idea. Likewise, in an astonishing cadenza, Kenny identifies every actor and wiseguy in the long POV tracking shot in the Bamboo Lounge.

His account of the cast rummages through filmographies and personal histories, and adds the sort of oversharing we welcome: “Behind the placid mook mug seen in the movie was a remorseless killer.”

All these exfoliating tales don’t conceal a sustained performance of film criticism. Kenny’s governing idea is that Goodfellas cons us through a bait and switch. Lured in by a rapid-fire opening that arouses a bemused attraction to these bad boys, we’re gradually forced to a more sober, even horrified, realization of their moral and emotional brutality. I think that this fairly reflects most viewers’ experience. But how does the trap work?

Kenny plots an “arc of disengagement” between the killings of Tommy and Spider. A rise-and-fall pattern links the parallel scenes of the Bamboo Lounge, the Copacabana, and the shabby tavern where the gang meets to whack Morrie. Kenny draws nuanced comparisons with The Godfather and is very detailed on Scorsese’s visual techniques, particularly the freeze-frames and fadeouts, which usually get less attention than the flashy camera moves. One of the book’s main points is that Scorsese, newly aware of how TV commercials trained viewers in quick pickup, deliberately decided to make his fastest-paced movie. And of course the music is central to managing our mood and commenting on the story.

As a seasoned reviewer, Kenny can write. “Frisky newlyweds still hot for each other; you love to see it.” Henry (“a walking appetite”) eventually pulls Karen into his schemes: “The revitalized marriage will find its sense of twisted teamwork.” And digression is welcome when it humanizes the author. Listening to Sid Vicious’ version of “My Way” is comparable to “say, eating the fried chicken from the Kansas City restaurant Stroud’s for the first time.” (The “say” makes the sentence.) A movie about food begs the critic to sample a little synaesthesia, with music evoking mouth-watering chicken. Come to think of it, that linkage of music and food is in Goodfellas too.

I especially enjoyed Kenny’s rebuke to fans who bust this carefully constructed work into “movie moments.” You probably know that one school of criticism thinks that films are more or less loose assemblages of scenes, out of which certain instants become incandescent. Certainly there are such moments in many movies, and sometimes they stand out from a gray pudding. But often strong moments ravish us because they’ve been prepared for by careful craft. So Kenny’s guided tour of Goodfellas shows its affinities with Keating’s holistic approach:

Serrano and his crew reduce movies to anthologies of “cool” or shocking moments, as opposed to fictions whose circumscribed worlds aspire to create beauty or sorrow or horror or joy in some formally coherent whole.

Mon semblable, mon frère.

Dead end at the ocean’s edge

La La Land (2016).

On the other hand, I ought to be out of sympathy with Mick LaSalle’s Dream State: California in the Movies. It’s unabashedly reflectionist, tracing how films project contradictory images of the Golden State. The screen image of California promises pure self-fulfillment, but that leads to loneliness, danger, conformity, and loss of dignity. If Kenny and Keating see movies as made by an army of artisans, LaSalle treats them as springing full-blown from American mythology. There is barely a mention of a director, let alone a sound mixer, in his account.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

I’ve explained elsewhere (here and here) why I find such claims unpersuasive. I think that reflectionism is every smart person’s mistaken idea about cinema. But sometimes, as with Susan Sontag’s essay “The Imagination of Disaster,” a reflectionist account of a film can activate some valuable ideas and information along the way, and it can host some entertaining writing. These benefits, I think, emerge throughout Dream State. In kaleidoscopic bursts, LaSalle provides suggestive takes on movies familiar and obscure, and the way they link to one another.

For example, he tracks recurring plot patterns. There’s California’s version of the One Great Night, when individual transformation takes place in a few hours of turbid activity (Superbad, Modern Girls). American Graffiti is the prototype, and in just two pages LaSalle evokes the way audience knowledge races ahead of the characters, far into the future. (Curt winds up in Canada, which probably has to be explained to young viewers today.)He’s very good on the cost-of-stardom plot, from What Price Hollywood to La La Land, this last the only film that faces the fact “that every great advance requires sacrifice, and that even though there is nothing like the joy of first love , there is nothing more important than the fulfillment of one’s inner self.”

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

Another critical avenue that LaSalle opened up for me was iconographic: the differences between LA movies and San Francisco movies. He deftly contrasts the ambience and topography of the cities. Noir and disaster films are primarily anchored in LA, while San Franciso movies tend to be steeped in nostalgia (e.g., Jobs, Milk). He keeps finding new angles to comment on. Avoiding the obvious effort to discuss California’s boom during and after the war, he skips back to the months around Pearl Harbor to bring to light films, mostly exploitation quickies like Secret Agent of Japan and Little Tokyo, USA, that rushed to treat Japanese Americans as potential spies. Meanwhile, the unoffending citizens were shipped off to internment. On a lighter note, anybody who’s bold enough to praise Gidget as a more mature film than Easy Rider gets my admiration (and agreement).

LaSalle, who came to California from the east, weaves in bits of memoir that highlight his main theme. And like Kenny, he writes with conversational wit.

“Home is horrible. Oz is horrible, too. . . but at least it’s in color.”

On Saturday Night Fever and Grease: “One seems tough, but it’s soft. (Of course, that’s the New York film.) One seems soft, but it’s hard. (Of course, that’s the Los Angeles film.)”

In Hollywood “integrity is so original it might just work as a strategy.”

In Out of the Past, “sex can kill you, but it’s worth it anyway.”

In San Francisco (1936) “if only to get Jeanette MacDonald to stop singing, the Earth had to intervene.”

Contrasting Monterey Pop to Woodstock‘s utopian fantasy, LaSalle nearly had me on the floor.

This is a model? Hundreds of thousands of intoxicated people, unable to wash, all but sitting in their own slop, cheering for a series of aristocrats that swoop down to entertain them and then leave? Meanwhile, the army flies in food and the slave classes clean out the Port-O-Sans? That’s sustainable as a societal model?

In addition to all this, through engaging appreciation, LaSalle has prompted me to seek out a great many films I hadn’t heard of. That’s another duty of the good critic. After seeing so much–pounding the beat every day–the movie reviewer can steer you to new discoveries.

Cinephile into cineaste and back again

He Said, She Said (1991).

All of these critics have participated in filmmaking. Mick LaSalle has written and produced documentaries. Glenn Kenny has been an actor in several films (including Soderbergh’s Girlfriend Experience). Patrick Keating, who has an MFA in cinematography, has been a DP on independent projects. Reciprocally, director Ken Kwapis started out wanting to be a film critic–in third grade, no less.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

Kwapis intercuts three sorts of chapters. There is the chronological account of the filmmaking process, with advice on taking meetings, establishing rapport on the set, giving actors “playable notes,” and coping with postproduction and marketing. Kwapis insists at every turn that you need to be both firm and flexible, open to every suggestion from the production team but still adhering to your conception of the project.

But this is not auteurism on steroids. If you’re not a Spielberg or a Nolan, the director has to learn tact and strategy. Kwapis emphasizes not abstract technique but the interactive, interpersonal demands of filmmaking, He suggests ways of responding to producers’ notes or actors’ complaints that allow everyone to keep their dignity. Just stepping away from the Video Village, that cluster of people around the monitor, and positioning yourself by the lens is a way of proactively steering the scene. He even gives good advice about bad reviews. His creative process? “I want to stand behind the camera and make sure there’s something alive going on in front of it, something recognizably human.”

A second batch of chapters shows this aesthetic/ethos in action through case studies from Kwapis’ career. Starting with Follow That Bird (1985), the Big Bird movie, and running up to A Walk in the Woods (2015), these chapters are about concrete problem-solving. How do you direct puppets? Or orangutans? Or Rip Torn? How do you support an actor who’s just not physically up to the role? There’s a fascinating account of staging options in The Office, where different situations force choices between developing the action in the “bull pen” or in the conference room.

The 1990s were rife with narrative experiments, and He Said, She Said (1991) was one of them. Unfolding over two days, its first part uses flashbacks to present Dan’s memory of his romance with Lorie, while the second part shifts to her version, with replays and gap-filling scenes that show the biases of his account. Kwapis and his wife Marisa Silver (Permanent Record) decided to divide responsibilities, with him directing the man’s scenes and her directing the woman’s. They also built in stylistic differences.

We pre-visualized each version to create as much contrast between Lorie’s and Dan’s personaities as possible. For example, I often show Dan’s literal point of view of Lorie, while Marisa uses camera movement and choreography to underscore how Lorie feels about herself (i.e., insecure).

They created specific ground rules for shooting the scenes. Kwapis’ portion came first, so that Silver could see it and fine-tune the replay. Kwapis is admirably specific about how their strategy shaped performance and plot, with minor characters in one half becoming major in the second.

In other words, a cinephiliac idea. (Kwapis prepared for his task by watching Rashomon, The Killing, and Citizen Kane.) The third type of chapter he offers is pure, sharp film criticism, always informed by the demands of craft. His account of American Graffiti is quite different from LaSalle’s, but no less appealing, emphasizing Curt’s visit to Wolfman Jack as an epiphany that needs no formal underlining (“no ham-fisted push-in”).

Other chapters scrutinize 2001, Lawrence of Arabia, The Graduate, I Vitelloni, and other classics. Without being pretentious Kwapis manages to invoke the “objective correlative” (e.g., shoes in Jojo Rabbit) and reflexivity (no big deal). I especially appreciated his detailed analysis of staging in a scene often overlooked in The Magnificent Ambersons: George’s confrontation with a gossipy neighbor, handled in one deftly choreographed close framing.

Kwapis designed the book to explore these three dimensions, but he isn’t puritanical about keeping them apart. Case studies and problem-solving pop up in the general advice sections, and the critical acumen shines through even brief examples of on-set tips (e.g., decisions about a score for Traveling Pants). It all flows together.

The result ranks with Sidney Lumet’s Making Movies and Alexander MacKendrick’s On Film-Making, the most acute personal reflections on Hollywood directing. But like those, it’s more than a testament to the power of craft. It’s also a vision of how, as the first chapter says, to go “beyond success and failure in Hollywood.” You do it, Kwapis maintains, by knowing your plan, respecting your co-workers, inviting discovery through accidents, and staying humane. I like to think that studying films as a critic helped him get there. Not every director, after all, can quote Jean Renoir.

“Only a hack cares about the goddam script”

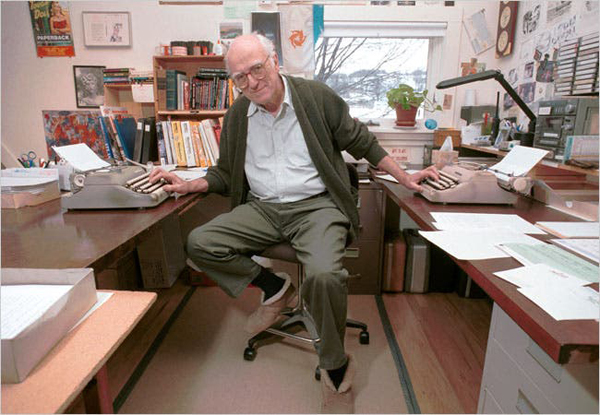

Donald Westlake (David Jennings for the New York Times).

I promised you a murderer, and he arrives in Donald E. Westlake’s Double Feature, a pair of novellas originally published as Enough (1977). The second, Ordo, takes place in Hollywood, when a sailor learns that his first wife has become a movie star and decides to look her up. It’s remarkable in several ways, but the story that grabbed me was A Travesty. On the first page a film critic kills his girlfriend.

True, it’s an accident, but even then he seems less distressed than he should be. He wipes down the crime scene and slips out. Of course he becomes a suspect. Once he seems to be cleared, the trusting cop lets him mosey along on later investigations. They discover that the critic has a knack for solving crimes, including an old-fashioned locked-room puzzle. He gets caught thanks to a plot twist that owes a good deal to Westlake’s early days writing happily overblown softcore porn.

True, it’s an accident, but even then he seems less distressed than he should be. He wipes down the crime scene and slips out. Of course he becomes a suspect. Once he seems to be cleared, the trusting cop lets him mosey along on later investigations. They discover that the critic has a knack for solving crimes, including an old-fashioned locked-room puzzle. He gets caught thanks to a plot twist that owes a good deal to Westlake’s early days writing happily overblown softcore porn.

The plot lives up to its title, being a travesty of whodunits and man-on-the-run thrillers. Westlake invokes mystery conventions like the dying message and the final twist: “As with all Least Likely Suspects, I was in reality the Murderer.” But this guilty protagonist is writing a profound essay on Top Hat and interviewing an over-the-hill director who undermines his belief in the auteur idea that “it’s up to the director to color and shape the material and so on.”

A: Yeah, that’s fine, but you got to have the material to start with. You got to have the story. You got to have the script.

Q: Well. . . . I thought the director was the dominant influence in film.

A: Well, shit, sure the director’s the dominant influence in film. But you still gotta have a script.

Well, that wasn’t any help. What was I supposed to do, go ask three or four screenwriters for suggestions?

A Travesty reveals that Westlake followed East Coast cinephile taste pretty closely. In the passage after this one, the killer regrets placing Brant so high in the Pantheon–a clear reference to Andrew Sarris’s writings. Better to ask a real director like Hawks or Ford or Hitchcock, or even Fuller.

Hip movie references are de rigueur in most mysteries today. (Grudge-reading The Woman in the Window, I thought: Just kill me now.) But how many thrillers in 1977 invoked Marion Davies or Manny Farber’s Negative Space? Our anti-hero argues with a girlfriend about circumstantial evidence in The Wrong Man and Call Northside 777. And as you’d expect, the big clues that reveal the killer to her come from Gaslight.

Westlake has long been one of my heroes; his Richard Stark novels get a chapter in that manuscript I mentioned at the outset. (Go here and here to gauge my dedication.) Like Elmore Leonard, he had a pragmatic approach to movie versions of his work. As far as I know, he complained only of Godard’s handling of The Jugger, which became Made in USA, not that anybody could tell. He wrote screenplays, notably The Stepfather (1987) and The Grifters (1990), and many of his stories have been adapted to the screen (Point Blank, The Outfit).

Nearly all his work I know has a zesty playfulness, and A Travesty is no different. It suggests that, after shooting down movies and destroying reputations, film critics have earned a chance to kill for real. They just turn out to be fairly bad at it.

My stack of reading has barely dwindled. I’ll try to file some more book reports as summer unfolds and the mosquitos discover our shady lawn.

Thanks to Patrick Keating and Mick LaSalle for sending me copies of their books, though I would have bought them anyway. Thanks especially to Patrick Hogan for telling me of his friend Ken Kwapis’s book.

Philip Pullman, a master of the sort of world-building Keating celebrates, argues against dwelling on the story spinoffs harbored by a richly realized milieu. He borrows the scientific idea of “phase space” to suggest that too great a concentration on the indefinitely large possibilities of a story world can freeze a narrative’s progress and distract the reader from the through-line. A story, he says, is a path through a forest and readers are best gripped by sticking to Red Riding Hood’s journey. (Compare Sondheim’s Into the Woods.) Interestingly, he compares this strategy to the cinematic idea of knowing the right spot for the camera, a spot that’s just as valuable for what it excludes as for what it shows. See Daemon Voices: On Stories and Storytelling (Vintage, 2017), 20-24, 122-123.

For more on Parker Tyler, see the chapter in my The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture. Avoiding straight reflectionism, Tyler saw the film world as its own sealed-off realm. If the movies reflect anything, it’s not what America thinks but what Hollywood thinks that America thinks. Or rather, what Hollywood imagines that America dreams.

In this entry I write about some of the anti-Japanese films Mick LaSalle discusses.

This entry analyzes the pseudo-documentary style of The Office. I write about 1990s as an era of narrative experimentation in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies.

No admirer of Westlake can ignore the addictive Westlake Review or, of course, the official webpage maintained by his son Paul. Westlake’s motto: “My subject is bewilderment. But I could be wrong.”

American Graffiti (1973).

Merrily he rolls along: A belated birthday tribute to Stephen Sondheim

Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (Tim Burton, 2007).

DB here:

Last month Stephen Sondheim celebrated his ninety-first birthday. By coincidence, I just finished a section on him in my current book on popular storytelling.

The argument there is that art at all levels, high and low, mass and elite, depends on novelty. That demanded accelerated in the twentieth century, with the explosion of book publishing, magazines, film, radio, theatre, and television. I see this process as a vast energy of crossover. Popular and “middlebrow” storytelling picked up on avant-garde innovations. But it seems to me that modernism, even the High Modernism of Joyce, Woolf, and Faulkner borrow more than is usually noted from conventions of popular storytelling. I hazard the view that it’s enlightening to look at how experimentation, innovations that open new avenues of artistic expression, emerge in mass-audience art.

Nowadays, most intellectuals have found something to love in mass culture. (“We are all nerds now.”) It wasn’t always so. In England and America, the “battle of the brows” had as one consequence the idea that true art, usually typified by High Modernism or the more radical avant-garde, was being squeezed. On one side was mass culture, manufactured as a commodity designed to sooth the masses. On the other was “middlebrow” art, which mimicked the techniques of modernism but made them simple enough for suburbanites to follow. By the 1960s, the people who believed in this trinity were in the minority, partly because they began to realize that centering on the most difficult side of modernism created too austere a prototype of all ambitious art. Irving Howe called this “The Decline of the New.”

Not that everything is a mashup. But I think now we all realize that crossover is a valid expressive option, probably the most pervasive one. The mass media make room for a huge amount of creativity that can’t simply be dismissed as lowbrow or middlebrow. And one reason it can’t is because we can still be excited by unexpected innovations.

Hence the importance of the nearly seventy-year career of a man who confessed a “taste for experiment in the commercial theatre.”

Experiments that are fun

Stephen Sondheim and Leonard Bernstein.

You couldn’t, I think, find a better case for the prospects for experiment in popular culture than his work. His fondness for stage games is part of a theatre tradition we might call “light modernism,” a merging of avant-garde strategies with traditions of popular entertainment. It stretches back to Cocteau’s Parade (1917) and includes the work of Pirandello. Similarly, a trend in British theatre fused aspects of modern theatre (Pinter, Beckett, Ionesco) with the comedy of P. G. Wodehouse and The Goon Show. Tom Stoppard’s Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead (1966) showed that what was “offstage” in one story could constitute the amusingly doom-laden plot of another.

Alan Ayckbourn dedicated his career to formal experimentation with space (three bedrooms as one in Bedroom Farce, 1975) and time (simultaneous action in How the Other Half Loves, 1969). Intimate Exchanges (1983) spreads forking-path plots across eight separate plays and sixteen possible endings. (Two of the variants are on display in Resnais’ films Smoking/ No Smoking of 1993.) House and Garden (1999) consists of two plays performed simultaneously in two auditoriums, with actors dashing between them. Ayckbourn’s most famous cycle, The Norman Conquests (1973) displays a “stacked” structure; each play gathers all the action taking place in one location and skips over scenes elsewhere, which are assembled in the other plays. The audience must construct the overall story, remembering what has happened just before the scene we see now.

Michael Frayn’s virtuoso Noises Off (1982) probably owes something to Stoppard and Ayckbourn, but it offers its own switcheroo. The opening scene of a sex farce is rehearsed in our first act, is performed skillfully in our second, and collapses in our third view. Crucially, the smooth show of the second act is presented to us in a backstage view displaying the intricate timing involved. Again, an abstract formal concept is mapped onto a conventional scenario, the comedy of a bungled stage production.

Michael Frayn’s virtuoso Noises Off (1982) probably owes something to Stoppard and Ayckbourn, but it offers its own switcheroo. The opening scene of a sex farce is rehearsed in our first act, is performed skillfully in our second, and collapses in our third view. Crucially, the smooth show of the second act is presented to us in a backstage view displaying the intricate timing involved. Again, an abstract formal concept is mapped onto a conventional scenario, the comedy of a bungled stage production.

Mystery plots make useful targets for this sort of popular experiment. Ayckbourn plotted some plays as quasi-thrillers, and Stoppard’s The Real Inspector Hound (1968) is a parody of the country-house murder. Stoppard undercuts the mystery by a Pirandellian device: two critics down in front are commenting as the performance unfolds. This gives Stoppard a chance to mock pretentious reviewing language. The standard whodunit device of reenacting the murder transforms into a replay of the opening act, but now with the critics taking the roles of detective and victim.

Also not surprisingly, both Ayckbourn and Stoppard declared themselves influenced by cinema, a reliable marker of crossover in modern media. Ayckbourn plays were adapted, with ingratiating wit, to film, while Stoppard wrote several scripts, most famously Shakespeare in Love (1998), which if the term means anything must count as defiantly middlebrow entertainment.

Sondheim is on the same frequency as these masters, but has, I think, greater bandwidth. He plunged into cinephilia more deeply. His early musical influences were Hollywood scores, notably that for Hangover Square (1945); Sweeney Todd, The Demon Barber of Fleet Street (1979) was his tribute to Bernard Herrmann. A Little Night Music (1973) and Passion (1994) were adapted from films. Many of his songs refer to movies, and he composed music for Stavisky (1974), Dick Tracy (1990), and other projects. He was even a clapper boy for John Huston on Beat the Devil (1953).

Instead of parodying mysteries, he has been deeply committed to them. Detective fiction is his favorite reading, and as a puzzle addict he has spent hours devising murder games. “I have always taken murder mysteries rather seriously.” Both Company (1970) and Follies (1971) were initially planned as mysteries, with the latter concerned not with “whodunit?” but “who’ll do it?” Sweeney Todd is a paradigmatic revenge thriller. Asked by Herbert Ross to write a film, Sondheim and Anthony Perkins (another admirer of “the trick kind” of mystery practiced by John Dickson Carr) came up with The Last of Sheila (1973).With George Furth, Sondheim wrote a play, Getting Away with Murder (1996), and with Perkins he planned the unproduced Chorus Girl Murder Case, an homage to 1940s Bob Hope movies. The clues would be hidden in the songs.

Fiddling with formula

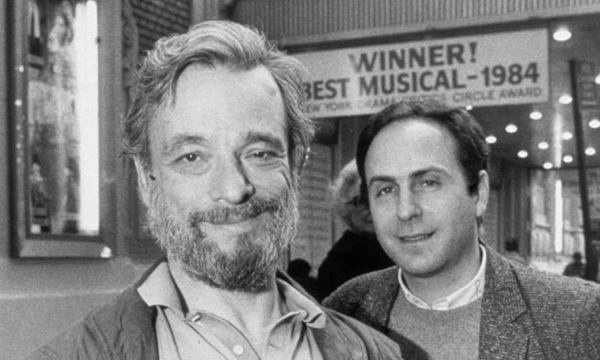

Sondheim and producer/director Hal Prince (left) during rehearsals for Merrily We Roll Along.

Sondheim’s zest for film and mystery fiction reflects a deep admiration for popular culture. It’s one thing to enjoy it, as Ayckbourn and Stoppard clearly do, while also poking fun at its silly side. It’s something else to appreciate its artistry in depth and try to master the conventions yourself. Despite learning “tautness” from the austere avant-gardist Milton Babbitt, Sondheim took as his mentor Oscar Hammerstein II. Tin Pan Alley, with its finger-snap rhythms and suave wordplay, pushed him toward a brisk cleverness. The virtuoso rhymes in his bouncy “Comedy Tonight” (A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, 1962) inevitably bring a grin: Panderers! Philanderers! Cupidity! Timidity! . . . Tumblers, grumblers, bumblers, fumblers!

While executing these pirouettes, the song provides a Cliffs Notes guide to Roman New Comedy by contrasting it with tragedy. Tonight, weighty affairs will just have to wait. Sondheim similarly lays bare a convention in his script for the unproduced movie Singing Out Loud, where the couple gradually learn that it’s okay to express emotion in song. “They have to learn to overcome the unreality of it and break into song in the conventional manner of all musicals.”

By taking fun seriously, Sondheim ransacks culture high and low for occasions for experimentation. He was crucially influenced by Allegro (1947), an ambitious Rodgers and Hammerstein musical he considered “startlingly experimental in form and style.” Its use of sliding screens to create “cinematic staging” would become standard in later musicals. He calls Hammerstein “the great experimenter” who used the verse sections of songs to explore possibilities of structure, melody, and harmony.

Sondhim’s breakthrough experiment was Company (1970). It consists of flashbacks framed by the protagonist Robert’s thirty-fifth birthday party. Sondheim claimed it offered “a story without a plot.” The flashbacks don’t supply a goal-directed character arc and instead sample Robert’s bachelor lifestyle and its effects on his three girlfriends and the five married couples in his circle. The result is a compare-and-contrast pattern of parallels. Complicating things further, bits of action are accompanied by a chorus-like commentary from characters not in the scene. Still, there is a certain progression to the whole, indicated by Robert’s disillusioned but faintly hopeful final song, “Being Alive.”

The nonlinearity of Company poimts up Sondheim’s impulse to play with time, viewpoint, and other techniques. Assassins (1990) moves freely back and forth across a hundred years. In Follies characters argue with their former selves. Sunday in the Park with George (1984), built on parallels between two painters, assigns inner monologues to artist and model; characteristically, Sondheim expresses jumbled thoughts by avoiding rhymes. Another duplex structure (Before/ After) shapes Into the Woods (1987), s a virtuoso braiding of classic folktales into a single plot.

Several plays utilize a narrator, who may take a role or converse with the characters. The Narrator of Into the Woods is killed fairly early in the action. Alternatively, Sondheim conceived Passion as an epistolary musical. Characters writing or reading letters operate “somewhere between aria and recitative,” rendering the emotional climaxes as “read rather than acted.” In this excerpt, Giorgio goes to bed with Clara while Fosca is reading his letter breaking up with her. This is a concert performance; in a full production the couple undress on one side of the stage, while Fosca reads the letter. Time floats uncertainly

Working in musical theatre gave Sondheim a layer of implication beyond what Stoppard and Ayckbourn had available with spoken dialogue. A score can evoke earlier scenes through leitmotifs and can enhance characterization. Starting with Anyone Can Whistle (1964) Sondheim created pastiche songs that vary from the show’s overall style. Merrily We Roll Along incorporates cabaret acts (“Bobby and Jackie and Jack”) while Assassins integrates various popular musical traditions, from vaudeville to melodrama. We might think of these pastiches as akin to the “polystylism” of the chapters of Ulysses, which Sondheim strongly admires.

Pacific Overtures (1976), a chronicle of Japan’s early engagements with the west, has the structure of a “portmanteau” film composed of exemplary episodes. It too has a narrator, the Reciter, and its experiments include turning renga linked verse into a passed-along song. The most formally daring scene, “Someone in a Tree,” stages the March 1854 signing of the treaty opening up ports to American ships. We do not see the ceremony, which is held in a secure house.

The Reciter questions an old man who claims that as a boy he watched the negotiations from a tree. During their dialogue, a boy clambers up the tree, and he and his older self collaborate in reporting the event he sees but cannot hear. Then the Reciter discovers a samurai guard hiding beneath the floorboards. He reports what he hears but cannot see. (Beware the YouTube ad at the start.)

As the singers’ accounts intertwine, a moment is assembled through partial perceptions. In a gesture reminiscent of Joseph Conrad’s novels, the event is broken up, made accessible only through partial viewpoints. And only the witnesses attest to the event; without them, we have no access to history. “I’m a fragment of the day./ If I weren’t, who’s to say/ Things would happen here the way/ That they’re happening?” In adapting novelistic techniques for relativistic point of view to the stage, Sondheim, as an experimental storyteller, is ready to plunder any tradition that can yield something fresh.

Form, “content,” and everything in between

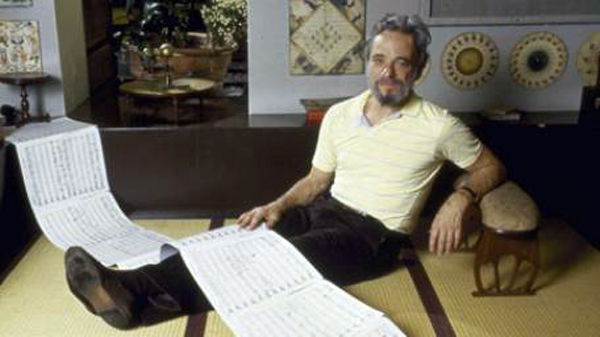

Sondheim and collaborator James Lapine.

In his invaluable creative memoirs, Finishing the Hat (2010) and Look, I Made a Hat (2011), Sondheim claims as a basic creative principle “Content dictates form.” But his puzzle-addict efforts to seek out difficulties to be overcome makes me think that this is more alibi than axiom.

I’d rather think that like many experimental artists, Sondheim uses “content” (whatever that is: subject matter, theme, bare-bones story) as at best one ingredient and often as a handy excuse. Sometimes audiences need help when faced with radical novelty. People may have been more receptive to Debussy’s daring pieces because of the “atmospheric” connotations of their titles. The stratagem of labeling one movement of “La Mer” as “From Dawn to Noon on the Sea” was pointed out by Erik Satie: “I liked the part at quarter to eleven best.”

Granted that Sondheim tries to suit his words and music to the genre and story he has selected, he often seems to take “content” as a pretext for solving problems he sets himself. Who else would decide to write all the songs for A Little Night Music in waltz tempo, not least for the challenge of avoiding monotony?

I think Merrily We Roll Along is a good example of how, accepting an initial problem, Sondheim complicates matters “unnecessarily.” This largely forgotten 1934 Kaufman and Hart comedy was formally daring: its scenes play out in reverse chronology, so the last scenes we see in the plot are the first events of the story. In adapting the play to a musical, Sondheim created a story of three twentysomethings trying to break into show business.

I think Merrily We Roll Along is a good example of how, accepting an initial problem, Sondheim complicates matters “unnecessarily.” This largely forgotten 1934 Kaufman and Hart comedy was formally daring: its scenes play out in reverse chronology, so the last scenes we see in the plot are the first events of the story. In adapting the play to a musical, Sondheim created a story of three twentysomethings trying to break into show business.

The purported rationale for telling their story backward is that it poignantly traces the loss of youthful idealism. But that arc could be just as poignant laid out in chronological order–or, if you want advance knowledge of how the struggles will turn out, via chronological flashbacks wrapped in a contemporary time frame. The reverse chronology seems both an experiment in whether audiences can follow the string of events and an effort to end a sad story in an upbeat way, with the characters still vigorous and hopeful–while we know what awaits them.

Sondheim faced an initial task of making the time scheme clear. He came up with transitional choral passages by the whole company that signal the shift to an earlier block of time. Different productions experimented with ways of reinforcing these musical tags, such as a synoptic slide show reminiscent of the “News on the March” sequence of Citizen Kane.

But the inverted chronology of Merrily We Roll Along also justifies experiments in musical texture. Because the play is about friendship, melodic motifs are swapped among the characters in their soliloquy songs. Moreover, in a 1-2-3 plot, Sondheim explains in Finishing the Hat, fully vocalized melodies are given reprises, shorter versions of the original number. Sondheim could have followed this convention. Instead, in relentless adherence to the reverse chronology, he made the reprises come first, as appetizers for songs yet to be fully heard. The puzzle addict will try to fit everything together in surprising ways, whether the audience realizes the fine points or not.

Solving one problem can launch a cascade of further problems. To introduce a 1980s audience to the musical ambience of Broadway’s heyday, Sondheim opted to revive the thirty-two bar song that he and his generation had “stretched out of recognition.” But then his penchant for pastiche posed a new problem. How to use that schmaltzy song form not just to satirize superficial characters like Joe the producer but to sustain connection to the sympathetic characters when they express authentic emotion?

Sometimes the problem is set not by “content” but by genre, tradition, or purely practical contingencies. Sondheim embraces show-biz conventions to discover what he can do with them. Hammerstein told him that the opening number can make or break a show, so Sondheim strives for a grabber when he can. The eleven o’clock number, a hangover from the days when shows began at eight-thirty, demands a show-stopping vehicle for the stars–e.g. “Anything You Can Do” in Annie, Get Your Gun. For Anyone Can Whistle, Sondheim wrote “There’s Always a Woman,” a rapid-fire comic confrontation between the two stars Angela Lansbury and Lee Remick, dressed identically. He conceived it as “the eleven o’clock number to end all eleven o’clock numbers.” It didn’t achieve what he wanted (“more like a ten-fifteen”) but it indicates his inclination to display virtuosity in response to purely formal demands.

Look, he made a show

Finishing the Hat and Look, I Made a Hat take us into the artisan’s kitchen–not only the studio or the stage where a team comes together but also the kitchen that’s the mind of the creator, who sweats out as much as possible beforehand. Sondheim shares with us the “choices, decisions and mistakes in every attempt to make something that wasn’t there before.”

This is a rarer accomplishment than you might think. Relatively few artists in any medium have the wish or ability to probe their creative process in detail, from conception to minutiae of execution. There are plenty of artists who talk of story sources and bursts of inspiration, but they seldom get down to the compromises, workarounds, and failed efforts. The best such books on popular storytelling, Sidney Lumet’s Making Movies and Patricia Highsmith’s Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction, are illuminating, but nothing compared to the multilayered self-consciousness Sondheim brings to the task. He notes: “The explication of any craft, when articulated by an experienced practitioner, can be not only intriguing but also valuable.”

It helps when the artist works in brief, segmented forms, such as the songs that make up a musical. They can be analyzed line by line, and can illustrate the challenges of word choice, rhythm, and rhyme as they relate to the ongoing story, the portrayal of character, and of course the score. This engineering side of construction, basic to popular art, is attractive to a practitioner who happens to be a puzzle fiend. He makes every choice a challenge to his ingenuity.

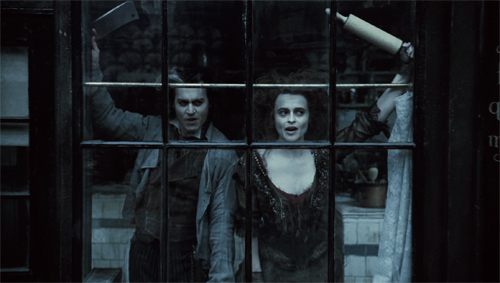

Take one example, “A Little Priest” from Sweeney Todd. Sweeney has decided to turn his lust for personal vengeance into random barber-chair homicide. This scheme suits Mrs. Lovett’s need to produce better meat pies. The result is a list song, a Sondheim favorite. Here’s the rendition of the Broadway original with Len Cariou and Angela Lansbury, for most of us the definitive version.

The couple deliriously catalogue what citizens might furnish appropriate ingredients. Sondheim’s founding choice: the list will consist not of individuals, who would need naming, but of social types whose titles can rhyme more easily. Sweeney role-plays a customer checking Mrs. Lovett’s imaginary wares.

Todd: What is that?

Mrs. Lovett: It’s priest./ Have a little priest.

Todd: Is it really good?

Mrs, Lovett: Sir, it’s too good, at least./ Then again, they don’t commit sins of the flesh./ So it’s pretty fresh.

Todd: Awful lot of fat.

Mrs. Lovett: Only where it sat.

Todd: Haven’t you got poet/ Or something like that?

Mrs. Lovett: No, you see the trouble with poet/ Is how do you know it’s/ Deceased?/ Try the priest.

Second choice: the song must be constructed so that the rhyming emphasis falls on the types, so the lines end on the name of the profession, as above. Third choice, new constraint: Throughout the play, Sondheim tries for triple rhymes, so one- or two-syllable professions (priest, poet) will allow for that. Fourth choice: the need to build the song out of short lines, which will permit “an increasingly intricate rhyme scheme.” That’s on display here, with priest–least–deceased–priest threaded with flesh–fresh and fat–sat–that and poet–know it.

The song surveys a range of social types, while reminding us of Sweeney’s main target Judge Turpin (“I’ll come again/ When you have judge on the menu”). The climax of the song declares a perverse commitment to equity. “We’ll not discriminate great from small/ No, we’ll serve anyone/ Meaning anyone–/ And to anyone/ At all.” The catalogue culminates in a sprightly celebration of mass murder.

Finicky as ever, Sondheim confesses that he never liked the line “Meaning anyone,” which is a place-filler, but now he says he knows how to improve it.

Why probe the artist’s craft in such detail? Sondheim notes that journalistic reviewers aren’t trained in technique or don’t know the trade secrets; they’re just declaring what they like or dislike. More intellectual and academic critics are inclined to write broad overviews, usually about the cultural sources and effects of the music. A practitioner who explains the cascade of decisions, freely made or imposed from without, can provide something rare. Just as the sports fan enjoys learning the fine points, learning the tricks of the artist’s trade can boost our appreciation. We can learn to enjoy “the spectacle of skill.”

No surprise: I was reminded of the historical poetics of cinema. This approach to film studies tries to analyze how filmmakers draw on the menus of options normalized in particular times and places. In trying to discover principles of craft practice, we seek out any information we can glean from artisans. For this purpose, we’ll not discriminate great from small.

At the movies

Sondheim with Steven Spielberg on the set of the remake of West Side Story.

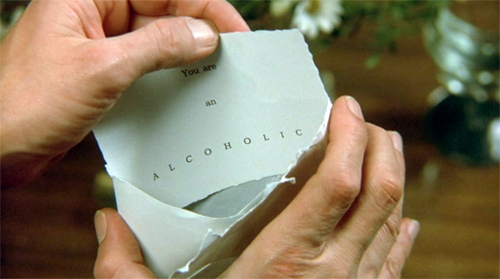

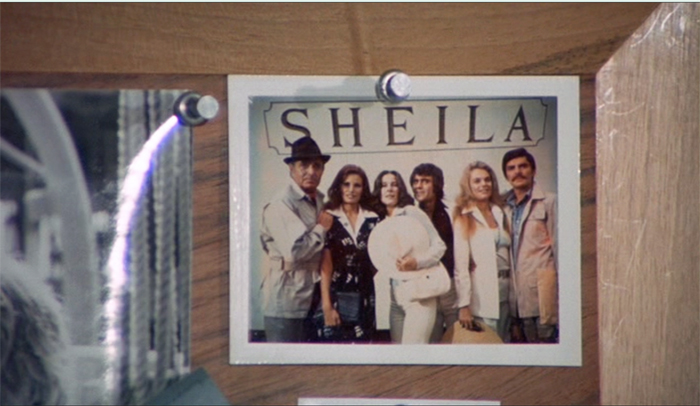

The Last of Sheila is a brittle, cynical satire on the film industry while being a well-designed classic mystery. Sheila Greene is struck down by a hit-and-run driver after she storms out of a party she and her husband Clinton have been holding. Under the promise of a potential movie deal, Clinton gathers six suspects on a pleasure cruise on the French Riviera. Once they’re are aboard, Clinton announces the entertainment: a mystery game. Each guest receives a card declaring a secret, such as “You are a homosexual” and “You are an alcoholic.” Clinton assures them that each is simply “a pretend piece of gossip,” but it becomes clear that the game is designed to expose someone, not necessarily the recipient, as guilty of the card’s charge. Meanwhile, Clinton tries to discover Sheila’s killer.

Every night, at the port they visit, the guests must follow clues to link one of them to a past transgression. The game is interrupted when one of the travelers is killed, and so the survivors embark on their own investigation. As in an Agatha Christie novel, the characters are stock types. There’s the vapid star, her hanger-on husband, the over-the-hill director, the rapacious talent agent, the second-tier screenwriter, and his heiress wife. Again, as in Christie novels like Death on the Nile and Murder on the Orient Express, the yacht cruise isolates the suspects and allows them to debate the identity of the culprit but also also to reveal Clinton’s scheme. In response, the killer has conceived a counterplot for baffling the other guests. Instead of these Christie novels, there is no designated Great Detective to take Hercule Poirot’s place. Any of the people hazarding solutions could be guilty.

In the spirit of the “fair play” detective novel, the audience is provided some clues that flit by, but can be checked on a replay. It’s not a spoiler to note the casual early appearance of an icepick, or the glimpses of some–but not all–of the clue cards.

By contrast, as John Dickson Carr points out, the really skillful mystery writer rubs your nose in the clues. It’s not a matter of a passing mention of the color of a man’s tie, or the way a character pronounced a word.

The masterpiece of detection is not constructed from “a” clue, or “a” circumstance. . . . It is not at all necessary to mislead the reader. Merely state your evidence, and the reader will mislead himself. Therefore, the craftsman will do more than mention his clues: he will stress them, dangle them like a watch in front of a baby, and turn them over lovingly in his hands.

The best example of this tactic in the film is the photograph at the bottom of this entry. The shot lets us dwell on Clinton’s apparently innocuous photo of his guests. Elsewhere the script plays up that old favorite, the discarded cigarette butt.

Sondheim and Perkins’ passion for classic detection is revealed in a long sequence of pure ratiocination. Across twenty-one minutes in the yacht’s lounge, one guest reconstructs the scenario behind Clinton’s game. The layout of space, in both long shots and shot/reverse shot, is quite precise and varied. Of course there are clues in the behavior of certain characters.

Part of the reconstruction turns out to be erroneous, as in the detective-novel convention positing an initial, faulty solution. In all, The Last of Sheila, while memorializing the sort of scavenger hunts and elaborate games Sondheim put his friends through, remains a rare example of an updating of the classic whodunit.

By contrast, the film adaptation of Sweeney Todd is a suspense thriller. The plot doesn’t hinge on an investigation but a pursuit (although that does yield a surprise revelation). Sondheim considers it the only satisfactory film version of one of his shows. “This is not the movie of a stage show. This is a movie based on a stage show.” But then what was the show? Opera? Operetta? No. “What Sweeney Todd really is is a movie for the stage.”

And a grim, brutal one at that. Tim Burton has developed Sondheim’s original through several cinematic strategies. One emphasizes Sweeney’s willed estrangement from humanity. If the stage Sweeney, often played by a large man, has a certain sweeping bravado, Sweeney on film scowls in soft-spoken fury. His puckered brows and pinched lips are set in a face as unearthly pale as a cadaver’s, or a clown’s. This seething little man is presented as virtually locked in his quarters, peering out at the world on which he will wreak vengeance.

Sweeney’s isolation is given a narcissistic cast when he unpacks his razors. He who has no human ties croons to “my faithful friends.”

Mrs. Lovett looks on, trying to secure a connection: “I’m your friend, too.” But he ignores her. Burton provides POV shots of Sweeney’s face reflected in his razor blade, a neat way of showing his self-absorption passing into violence.

At one point, he seems to register Mrs. Lovett’s gestures of affection, and Burton neatly shows the POV reflection shifting to her.

His contemplation of her as an ally can, it seems, only see her as another reflection of himself and an instrument of his vengeance–a tool, not a lover.

He rejects her affection (“Leave me”) and he twists the razor, turning the reflection back to him. He’s still locked in his solitary obsession.

He finishes the song alone, now even more committed to his mission. A final shot shows him gleefully peering out the window at the city he and his faithful friends will ravage.

Mrs. Lovett becomes his genuine accomplice in the song, “A Little Priest.” In the stage directions, Sondheim asks that Sweeney and Mrs. Lovett use pantomime to evoke the meat pies they want to harvest from Sweeney’s customers. In the film, however, the pies she has already made are surrogates for the ones she proposes.

Given the more tangible setting, Burton returns to the window motif; Mrs. Lovett’s shop becomes an extension of Sweeney’s enclosed world. The couple’s list-song takes place with the two of them at the windows, scanning the street for victims. As you’d expect, they spot a priest first.

If the barber shop upstairs is Sweeney’s mission control, the pie shop becomes his supply center. Mrs. Lovett realizes that she can get his friendship only by joining his plan for vengeance, and once he realizes her commitment, she becomes an attractive partner. They pledge their partnership in a rolling-pin waltz, and the sequence ends with a shot that echoes the earlier capstone, but including Mrs. Lovett.

There’s a lot more to be said about The Last of Sheila and Sweeney Todd, but I invoke them just to show that Sondheim’s talents can create robust, innovative, sometimes disturbing cinema.

I could imagine someone criticizing Sondheim as the ultimate middlebrow artist. Adapting foreign films (Smiles of a Summer Night, Scola’s Passion) and Grand Guignol to the American musical; turning Seurat’s Grande jatte into a living tableau (and naming the painter’s model Dot!); imposing games with time and viewpoint on a showgirls’ reunion; investing fairy-tale optimism with sinister implication–all can seem too clever by half. An objector might say that a Sondheim show doses schmaltz and hokum with just enough formal ingenuity to let audiences feel clever. But I think that sort of having-it-both-ways defines a great deal of popular entertainment, and it has its own value. Bergman and Seurat and Little Red Riding Hood remain unharmed by plays that take them as pretexts for ravishing music and cunning theatrical games. Formal ingenuity is not a small thing.

Sondheim opened new vistas for the musical to explore. I suppose you can call Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton middlebrow too, making rap and hip-hop safe for people who can afford a Broadway ticket. But if you think Miranda opened new paths, note that he thinks that Sondheim pointed the way. He took advice from Sondheim while writing the show, and he paid tribute in a preface to an interview:

He is musical theater’s greatest lyricist, full stop. The days of competition with other musical theater songwriters are done: We now talk about his work the way we talk about Shakespeare or Dickens or Picasso.

You don’t have to go that far to see that artists at all levels of taste innovate, and their efforts sometimes oblige us to see fresh expressive possibilities in their artforms. If we are all nerds now, we can become connoisseurs of the experimentation–sometimes subtle, sometimes bodacious–that pervades popular entertainment. Sondheim, meticulous and generous and tirelessly exploring, coaxes us to do that.

I’ve drawn most of my Sondheim quotations from Finishing the Hat: Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) with Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes (Knopf, 2010) and Look, I Made a Hat: Collected Lyrics (1981-2011) with Attendant Comments, Amplifications, Dogmas, Harangues, Digressions, Anecdotes and Miscellany (Knopf, 2011). Other remarks come from Craig Zadan, Sondheim & Company (Harper & Row, 1994) and Meryl Secrest, Stephen Sondheim (Knopf, 1998). Google Book Search should help you locate my citations by phrase. Steve Swayne provides a thorough analysis of the role of cinema in his career in How Sondheim Found His Sound (University of Michigan Press, 2005), 159-213.

More general books about the craft traditions Sondheim adopts and revises are Philip Furia’s The Poets of Tin Pan Alley: A History of America’s Great Lyricists (Oxford, 1992) and Jack Viertel, The Secret Life of the American Musical: How Broadway Shows Are Built (Farrar Straus Giroux, 2016. I’ve praised and applied Viertel’s account in this earlier entry.

Sondheim discusses the composition of “Someone in a Tree” in this interview with Frank Rich. The second part is especially revealing about Sondheim’s combining music and lyrics through a vamping figure. That accompaniment, detached from the sung melodies, depends on a “gradual change” principle that reminds me of the minimalist music of Glass (Einstein on the Beach, 1975) and Reich (Music for 18 Musicians, 1976) at the same period. A musicologist would probably correct me, but if the affinity holds good it would further show Sondheim’s pluralistic appropriation of many traditions. Thanks to Jeff Smith for discussions of this and for help with other musical matters.

The John Dickson Carr quotation comes from his 1946 essay, “The Grandest Game in the World.” The most complete version of it is in The Door to Doom and Other Detections, ed. Douglas G. Greene (Harper, 1980), 334-335.

Many fine appreciations of Sondheim appeared around his birthday, but I especially like this one by Jennie Singer, packed with clips.

For a long time Kristin and I have studied innovations in popular storytelling, as in her analysis of narrative in the New Hollywood, my book on the same area, her monograph on P. G. Wodehouse, our book on Christopher Nolan, my studies of Hong Kong cinema and 1940s Hollywood, and comments over the years on this blog (e.g., Paranormal Activity and Happy Death Day). For more on Into the Woods, go here.

The Last of Sheila (Herbert Ross, 1973). This shot harbors a clue–actually, more than one.

P. S. 18 April 2021: Sondheim has been extraordinarily generous in sitting for interviews describing his creative process, and many are stimulating. Alert reader and master interviewer Brian Rose kindly sent me a link to the remarkable 2020 interview with Adam Guettel that you might enjoy.

Let’s play God, imperfectly: BLOOD SIMPLE on the Criterion Channel

Blood Simple (1984).

DB here:

Over the last couple of years I’ve been writing a book on common strategies of popular storytelling in film and other media. I go on to trace how those strategies get worked out in detective stories and thrillers. If you follow this blog, you know that these genres are ones I enjoy and like studying.

So I was happy to offer as one installment of our Criterion Channel series, Observations on Film Art, a short analysis of storytelling strategies in Blood Simple. In it I suggest that although the film has the trappings of a neo-noir–the somewhat downmarket characters, the seedy milieu, the chiaroscuro lighting–in its narrative techniques it’s closer to a Hitchcock thriller. That’s because its manipulation of point of view, one of the resources of popular storytelling, is close to the “partial and misleading omniscience” of the thriller genre and Hitchcock’s narration in particular.

Put it another way. We aren’t restricted to what only one character knows, as in a detective story like The Big Sleep (1946). Instead, Blood Simple steers us selectively from one character to another. So we always know more than any one of them does. That creative choice increases suspense–knowing the dangers that lurk ahead–but it also summons up an ironic detachment from them, as we watch them make their foolish mistakes. In a word, if you know the film: fish. Here’s another: lighter.

This shifting viewpoint doesn’t give us absolute knowledge, though. There is still some information that slips through the cracks. So we can enjoy superior knowledge in long stretches, while still getting some sudden surprises, or even shocks. (Consider the climax with the perforated wall and the knife at the window.) In their first feature, the Coens prove themselves already fully in control of finely-tuned cinematic storytelling. We’re a step ahead of the characters, but the film is a step ahead of us.

The Coens are also aware of our pleasure in their control. The characteristic Coen awareness, a sly recognition of letting the audience share their power over our access to the story world, is everywhere in evidence. I didn’t have time to mention the shot that everybody remembers, the tracking shot down the bar that simply lifts over the drunk sprawled on the bar top. We become aware of how the movie’s unfolding narration is absolutely ruling how we see this world, and the Coens make a gag out of it. Even the camera-god has a sense of humor.

If you have a chance to watch it, Jeff Smith, Kristin, and I hope you enjoy it–and, of course, the film, which is endlessly rewatchable.

As usual, thanks to the team at Criterion: Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Penelope Bartlett, and their superb postproduction boffins. We recorded the commentary under Covid conditions, with the expert guidance of Erik Gunneson, Meg Hamel, and James Runde.

For more on the Coens’ mastery of storytelling technique, check out the analysis of their fine The Ballad of Buster Scruggs.

You can sample other blog entries on mysteries and thrillers in several entries, in particular our discussions of Hitchcock (of course), and the genre as a whole (here and here and here). An early version of one chapter of my book in progress is devoted to the great Rex Stout. Another chapter will revise what I said about Gone Girl. I also discuss Hollywood’s approach to crime and mysteries in the book Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

Blood Simple (1984).

A fast-paced cinematic impeachment trial

DB here:

Donald Trump did not lose the 2020 U. S. presidential election. He was inaugurated on 4 March. Joseph Biden was arrested and executed.

Or, if you like: Trump will be sworn in on 20 March, the anniversary of the founding of the Republican Party (in Ripon, Wisconsin). Or Trump is President already and working with the military to prepare the mass executions of Democrats. Meanwhile, the Pope was arrested, or will be.

These are among the many lies and delusions promulgated by fantasists, particularly QOnan (not a typo). But these are also narratives.

Narrative in many manifestations, from jokes to comic books, is one of my keen interests. While mostly studying storytelling in film, I noticed some years back how the term and concept of “narrative” became a part of political discourse. I used that buzzword as a path into analyzing the yarn-spinning around presidential campaigns (here and here) and, inevitably, stages in the fascist coup attempted by the fumbling but indefatigable Trump regime (here and here and here and here). The coup effort continues, now at the level of Republican state legislatures.

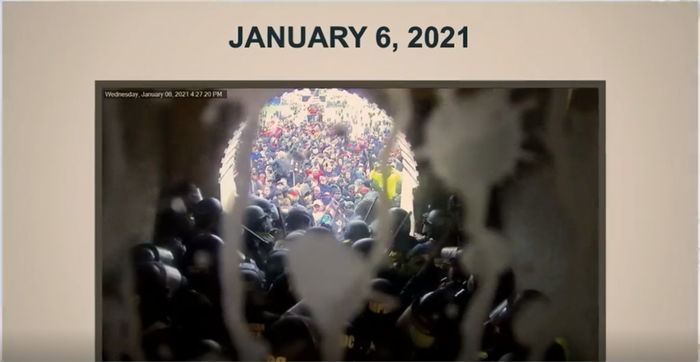

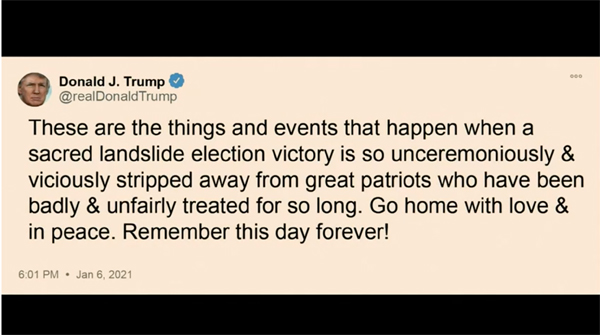

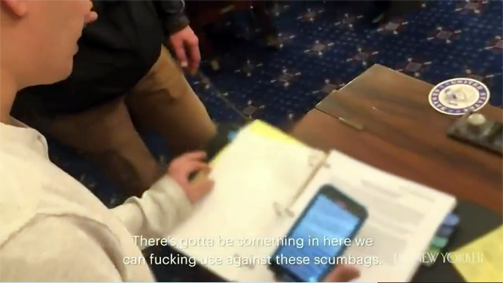

The 6 January assault on the US Capitol, an atrocity many of us followed in real time, has been recast as different stories. The versions range from treating it as an escalation of Trump’s seething rallies to brazenly caricatural accounts, notably the version promulgated by my senator Ron Johnson (R-Wisconsin), a man of invincible ignorance. The versions I want to look at are those laid out in last month’s impeachment trial (Trump’s second) by the Prosecutors from the House of Representatives and the ex-president’s legal Defense team.

The trial began on 9 February with consideration of whether the Senate could impeach a President no longer holding office. That issue was settled by a vote that impeachment could proceed. The trial proper began on 1o February. The charge was that Trump incited the riot that led to the invasion of the Capitol on 6 January 2021.

On 10 and 11 February, the House Impeachment managers presented their case. On 12 February, the Trump attorneys presented their defense, after which both sides entertained questions from senators. The final day, 13 February, was taken up with debates about whether witnesses and further testimony would be invited. After that was resolved, the proceedings ended with a vote on conviction. Sixty-seven votes would have been enough to convict Trump, but only 57 votes for that outcome were cast. Trump was acquitted.

Trump’s original speech to his followers is transcribed here. Official transcripts of the Senate sessions are available on the Congressional Record site. A video record of the proceedings, with good quality on the video clips, is on the C-Span site. This also includes a rolling transcript.

Both sides used film to make their arguments. The House team promised what the press called “a fast-paced cinematic case,” and the Defense responded with pieces of cinema of their own. What resources of cinema did they use? And how do the uses differ?

Narratio as you like it

In Film Art: An Introduction, Kristin and I contrast narrative form with other options. We suggest that a film (or a literary text or a TV show, etc.) could be organized in various ways. Take whales. Using categorical form, you might provide a taxonomy of whales. Using rhetorical form, you could make an argument about whale conservation. With associational form, you might provide a poetic meditation on whales as metaphors for strength and grace. With abstract form, you might film whales in ways that turn them into pure patterns of imagery and sound. And using narrative form, you might tell a story about how a stubborn young girl helped get a stranded whale back into the sea.

Any given film could combine these principles. An argument for conserving whales could include sequences that give us information about genus and species, while other sequences could poeticize the great behemoths in the Whitman manner, or let us appreciate their abstract beauty. Since we all like stories, there will be a strong temptation to “narrativize” when we can. Even a film that tries to make an argument is likely to include some passages involving agents and actions, goals and obstacles.

A rhetorical film doesn’t have to include a narrative component, but it may well do so. Our example in Film Art, Pare Lorenz’s The River, relies on the classic rhetorical structure of problem/ solution. But inserted in that structure we find stories about how the Dust Bowl came to be a disaster area and how the government has taken steps to improve things.

A court case is a prototype of rhetoric. Aristotle accorded little importance to storytelling in forensic rhetoric, but later thinkers recognized the powerful role that it plays. Theorists came to call narratio the portion of the argument that tells the story, or rather competing stories, of the matter in dispute.

All of which is a long-winded way of saying that we shouldn’t be surprised that the House Prosecutors and the White House Defense team would float some stories. But what stories were told? How did the advocates tell them? Do the presentations push beyond narrative to other types of form? And what implications do these strategies have for how political actors use moving-image media?

To analyze the cinematic strategies at work, it’s useful to know how they further the broader cases being made. So for each side, I’ll try to show how its use of cinema grows out of its general rhetorical/narrative strategies. Beyond that, we are in a strange re-creation of the situation dramatized in Fritz Lang’s staggering Fury (1936), a film for our moment if ever there was one. There people accused of lynching a man must watch a courtroom screening of their actions during the crime.

Needless to say, there was much less self-examination shown by Republican senators when confronted with powerful sounds and images showing the fury they unleashed and did nothing to forestall.

Witnesses, plenty, for the prosecution

Analyzing a piece of rhetoric demands that the audience be considered. Since rhetoric is centrally about persuasion, how is the argument shaped to suit the audience’s inclinations?

Almost no one expected that Trump would be found guilty, so were the House’s efforts to mount a case a hollow exercise? I think not. The House advocates, it seems to me, were addressing two audiences: the general public and, to put it grandiosely, history. Representative Jaime Raskin and his colleagues treated the matter as a criminal case, offering a detailed reconstruction of motive, method, and opportunity. Assuming that future analyses would be skeptical and rigorous, looking for holes in the Prosecution account, they tried to make it tight, evidence-based, and the most plausible explanation of the events of 6 January.

Their account can be revised in the light of new information (such as recent findings of who funded the rally and how it was coordinated with the White House). Still, it aspired to be a reliable first draft of the most accurate and comprehensive story of the event. The managers injected emotion into their account by emphasizing the casualties of the melée, the narrow escape that legislators made, and the damage to American ideals when the seat of government was ravaged.

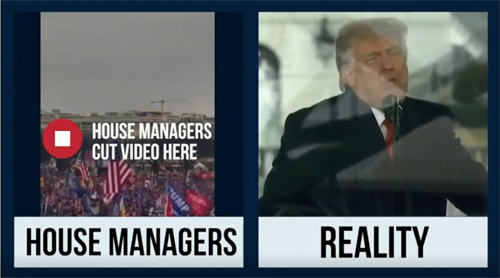

The Prosecution accordingly constructed a complex, time-looping, “novelistic” narrative. Taking advantage of the primacy effect, they laid out their story in a dense fifteen-minute video at the start of the first day, during the argument about constitutionality. I’ll consider that montage shortly, but the crucial point is that it concentrated on the attack, with immersive and brutal footage.

Over the next two days, the House managers spiraled out from the attack footage by means of a plot structure that starts with a crisis. This strategy introduces us to the action just before the story’s climax and then fills in what led up to it.

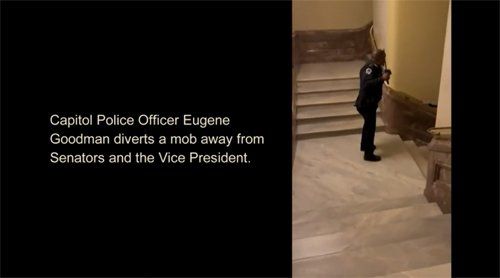

The Prosecutors’ first step was to establish the story’s antagonist, the “inciter in chief.” Trump was put front and center in a flurry of quotes pulled from moments before, during, and after the raid, ending with him declaring to his followers: “We love you, you’re very special.” Who opposed this central figure? Interestingly, the Protagonists initially cast the Capitol police, particularly the black officers who were stunned by the racism they confronted.