Archive for the 'Narrative strategies' Category

Madalena, Rosalind, and Suzanna: More Rotterdam revelations

Madalena (2021).

DB here:

A mixure of moods and tones for our final communiqué from the International Film Festival Rotterdam. Its fiftieth year has been a lively one.

The Madalena mystery

Madalena (2021).

In earlier entries (especially here) I’ve noted that the thriller genre is well-adapted to festival circulation. It doesn’t require the budget of a blockbuster. It can attract major actors who want tricky parts to play. It can be shot on contemporary locations. And the appeal to suspense and surprise fits comfortably with edgy narrative strategies favored by art cinema. At the limit, a filmmaker can arouse our thriller appetites and then try a bait-and-switch that not only warps the genre’s conventions but sets us thinking.

The Brazilian film Madalena, by Madiano Marcheti, starts as a classic mystery. In a vast field of soy, reas stalk gracefully as a monstrous pesticide-sprayer grinds toward them. But among the rows lies a corpse.

What follows is more fractured and prismatic. A first section attaches us to Luci, a friend of Madalena’s who works as manager of a club. She also picks up work dancing for TV commercials, one set in that very acreage. Then we follow Cristiano, whose father owns the land and demands he hustle to harvest. A third section takes us with trans woman Bianca and her girlfriends, who sort through Madalena’s belongings before setting out for a day of driving, swimming, gossiping, and teasing one another, the memory of Madalena never far from their thoughts.

Marcheti skips some of the standard scenes. We never see the police investigation, or even the discovery of the body. The crime plot has been a pretext to reveal a cross-section of life in the community, from the wealthy farmers to the cottages where the staff live. The resolution shifts the question of who did it to the broader impact of the death, and how it stands for a horrifying statistic: Brazil has the world’s biggest murder rate of transgendered people.

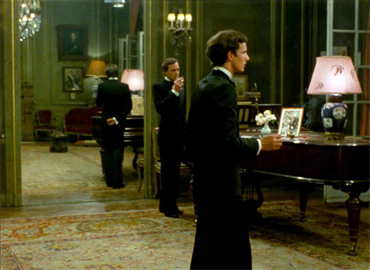

Throughout, sexualization of bodies is a central motif. Luci and her posse hang out at curbside, Bianca and her posse turn tricks and find boyfriends, and Cristiano, after sizing up the crowd at Luci’s bar, winds up dancing with himself in mirror reflection.

To say much more would spoil things, so I’ll just note that this story is filmed with a pictorial intelligence that one seldom sees these days. The imagery of the soy fields is at once magnificent and ominous. Drones hover over it like birds of prey, and its horizon haunts the people’s lives.

Overwhelming as the landscape is, it doesn’t blot out the characters’ routines and the crises that disrupt them. Moving from Luci’s aimless days and nights to Cristiano’s panic to Nadia’s quiet tribute to Madalena, a locket set adrift in the stream that runs along the field, the film pauses for intimate moments. It reminded me a bit of Varda’s great Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi), in which an enigmatic figure’s fate charts the range of human indifference, but also affords glimpses of sympathy.

An informative discussion of the film with Marcheti is provided by IFFR here.

As we too like it

As We Like It (2021).

This movie saw me coming a mile away. It does for As You Like It what Lurhmann did for Romeo and Juliet, but to an Asia-pop beat. Four romantic couples lose and rediscover one another in a magical milieu–not the Forest of Arden (currently under corporate development) but a district of Taipei with no Web connections. In Heaven, a sign informs us, there is no Internet.

Accordingly, people must deliver messages in person, seek out each other by dint of shoe leather and motorbikes, and actually meet face to face. So Rosalind’s quest to find her father the Duke (a genial tycoon) intertwines with Orlando’s search for her. But of course she’s disguised as a boy and aided by Celia, a fortune-teller who’s the dream girl of Orlando’s sidekick Dope.

The film’s world is maximum kawai, pushing beyond camp to a fangirl fantasy of irresponsible sweetness. This candy-colored city, with its pink blimps and anime posters, spills over with tweens, teens, and twentysomethings shopping in malls, flirting at stalls, and sipping bubble tea.

In the process, old stuff becomes cool. Tradition, in the form of calligraphy and handmade paper, is a retro decorator choice, while letting your date clean your ears old-style makes him a friend with benefits.

It might all seem sappy, but like Tati’s Play Time and Wong Kar-wai’s Chungking Express, the film seeks to distill authentic poignancy out of kitsch, schlock, consumer clichés, lethal cuteness, and the detritus of urban lives. Frivolity must be good for something; why else would God give us giggles? Comic form, as Shakespeare acknowledged, redeems a lot of silliness, especially if the gags are hurled at us with the ruthless conviction that anything goes.

Did I mention that all the roles are played by female performers?

In a switcheroo on Elizabethan theatre, globalization inverts the Globe. The film, a final title tells us, is dedicated to Shakespeare “but also to the patriarchy who would not allow female actors upon the stage.” The frisson is akin to that of Tsui Hark’s Peking Opera Blues and The East Is Red, where gender-blurring yields both humor and genuine feeling. From instant to instant, you see a character go male or female or something in between; a painted-on mustache and a swaggering gait become cosplay, not deep definitions of you. Unless you want it to be.

Identities are fluid. Okay, says Orlando, so he falls in love with Rosalind, then Roosevelt, and refinds him/her as Rose. What’s in a name? You get to call yourself, and be, what you wish, and love whoever.

Not a fresh-minted message these days, but the sparkle comes with how it’s all carried off. Every scene finds a clever way to amuse or bemuse. When Rosalind as Roosevelt slips into a trim suit, she pads out the crotch with a towel, and teeny gull-like waves waft out. That’s soft power, the equivalent of a mystic ring. Eventually she has to go along when Orlando visits the men’s room. While he stands at the pissoir, she ducks into a toilet pretending to take a dump, her groans covering the sound of peeling open a maxi-pad.

The project was co-directed. Wei Ying-chuan, a graduate of NYU’s Educational Theatre division, is a founder of Shakespeare’s Wild Sisters Group in Taiwan. Chen Hung-yi’s feature The Last Painting was chosen for IFFR in 2017 and won a best feature award at Cines del Sur. The pair bring an unflagging energy to the task of creating a paradise of easy living and loving–bereft of villains, open to any piece of harmless fun and heartbreak. As We Like It is a must for every LBGTQ film event, but its hella dirty fun for any festival whatsoever. Couples welcome.

Again, the IFFR provides a fine discussion of the film with the directors, moderated by our old friend Shelly Kraicer.

St. Tropez, mon amour

Suzanna Andler (2020).

Eric Bentley once described great serious literature as “soap opera plus.” Anna Karenina, Othello, and the rest offer us tormented love affairs, sexual jealousy, hidden schemes, and forced confessions of betrayal, but it’s all endowed with wider significance through characterization, implication, style. But can we have soap opera minus?

In Daisy Kenyon, Anatomy of a Murder, and other films, Preminger moves in this direction, banking the fires of conflicts drawn from lurid bestsellers, but other filmmakers have gone further in de-dramatizing melodrama. Dreyer’s Gertrud and some of Oliveira’s adaptations offer examples. Here we have the classic fraught situations, but muffled and fragmented and punctured through long pauses and wayward, looping, maddeningly banal conversations.

Marguerite Duras made this artistic strategy peculiarly her own, notably in her masterpiece India Song (1974) and its counterpart Son nom de Venise en Calcutta désert (1976). In a curious reversal, she often prepared the film first and then published the text as a quasi-play, as if scraping away the luscious imagery and ripe sound would create something even purer, soap opera distilled to Racinian starkness.

Suzanna Andler, a Duras theatre piece from 1968, has now been adapted to film featuring Charlotte Gainsbourg and three other players. The result isn’t as severe as the play reads, since director Benoît Jacquot has filmed it in a gorgeous villa overlooking the Mediterranean. It remains, however, in the tradition of kammerspiel. The bulk of the action takes place in a salon and the terrace outside, with one sequence, also in the play, set on a rocky beach.

The situation is sheer bourgeois melodrama. Suzanna is in a loveless marriage with the philandering Jean. She has apparently stayed with him for the sake of their children and the wealthy life they lead. Now Michel, a young journalist, has tempted her into a love affair, and she has for the first time cheated on Jean–who seems okay with it. Today’s crisis, if this counts as one, is her need to decide: Will she lease this villa for the summer with the kids? Or will she accept Michel’s invitation to go to Cannes? In the course of about four hours, she may make up her mind.

If some of my synopsis seems hazy, it’s partly because the exposition comes out in bits as Suzanna and others chat about her past, and partly because what she says may not be wholly truthful. She sometimes admits to lying. And what was her relation to the never-seen Bernard Fontaine, who has just been killed in a car crash? The blurry backstory is one strategy Duras uses to tamp down the melodrama, which usually gives its plots clear-cut contours and definite revelations.

In filming the play, Jacquot has taken an approach that approximates the rigor of Duras’s aesthetic. He has shot the blocks of action using slightly different techniques. Not for him obvious alternatives like color/ black-and-white or a range of tonalities. The differences are made harder to spot because Jacquot has not given us separate chapters corresponding to the act divisions; the scenes blend, punctuated only by long shots. So there are stylistic spoilers coming up.

At the start, Suzanna is shown the house by the real estate agent de Rivière. This segment is filmed in distant shots that emphasize the landscape and straight-on views of the sitting room opening out onto the terrace and the sea. The agent is seen from behind or at a distance, while the few close views we get concentrate on Susanna.

Staying behind alone, she falls asleep and awakes when Michel enters. This is a second phase of the play’s first act, and now Jacquot’s camera setups take a more oblique view of the room. The full-length windows dominate again, but now at an angle that recalls the magic mirror of India Song (on which Jacquot was an assistant).

The couple is often seen at a distance, but now closer views of Suzanna emphasize the mirror motif.

At a high point, the camera celebrates a momentary reconciliation with a track in to their embrace (the first such florid move in the film, I think).

In the sequence corresponding to the second act, Suzanna meets her friend (and Jean’s ex-lover) Monique. On the beach they talk of their pasts. Now the conversation is rendered in many rapid, tight shots of the two women. The orthodox shot/ reverse shot setups are sometimes given a strange emphasis when instead of A/B alternation we get two (but only two) variants of a view of each one as she speaks (A1/A2, then B1/B2). So a cut like this::

. . . is followed by ones like these:

Back at the villa, Suzanna answers a phone call from Jean, and they discuss their plans, with the uncertainty typical of all the film’s conversations. This scene is handled in circular tracking shots around Suzanna, from a moderately close distance.

As the conversation ends, Michel returns. After he reveals some key information about his relation to Jean, he stretches out on the sofa. In a long take running several minutes, the camera swings around them in a half-circle, clockwise and counterclockwise, often adjusting to her shifts in position.

The changing angle also captures Suzanna perched against a painting of very 60s boomerang shapes that echo the camera’s trajectory.

As the action approaches what might be a climax, Michel drifts out to the terrace and sits on the balustrade above the sea. Suzanna approaches.

Telling you what happens next would truly be a spoiler. On seeing it, I thought it was something that Jacquot added to the play, but nope . . . it’s there in the text, and he’s perfectly faithful to it.

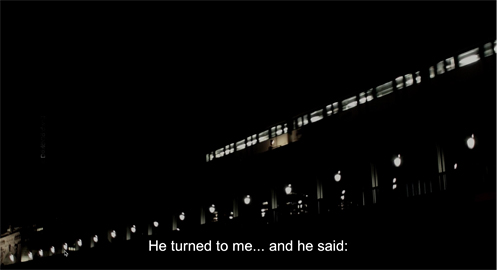

As if all this patterning doesn’t look finicky enough, the scene on the beach is punctuated by a single shot of the Quai de Passy with a Métro train rumbling by.

This bump comes exactly halfway through the film, at the moment Suzanna mentions the surge of attraction she felt when Michel looked at her on their first encounter. Believe it or not, the line in the play also comes midway through the text. This alien shot functions expressively, I think. It underscores the epiphany Susanna felt upon learning she might be loved. Another filmmaker might have stressed the moment with music under her monologue, but Jacquot goes for a formal bonus: breaking the visual texture just here further articulates the design of his film.

The rigorous geometry Jacquot has clamped down on the play is interesting in itself, and the abstract array of options adds, I think, to the hieratic quality Duras is after. Yet each style matches the tenor of the action it carries and doesn’t conceal the subdued feelings rippling through the scenes. This dimension depends on Gainsbourg–her slim silhouette, her microdress, and especially her face, with her alert chin and hard mouth. Her vacillations have nothing of the diva about them, but still she stands forth as a new avatar of The Confused Woman so beloved of art cinema (Voyage to Italy, L’Avventura, The Headless Woman). Without those closer shots, the film might fall flat.

Once asked what would be his ideal final shot, Jacquot replied: “A distinctive glance [un certain regard] in close-up.” His ending delivers that.

Duras is doing something similar to what Wei and Chen do in As We Like It. She is seeking genuine emotion in clichés (unfaithful husband, wrung-out wife, surly rescuer). But she hasn’t exempted her characters from social critique. Hiroshima, mon amour renders the meeting of two lovers as an intertwining of two national histories. The colonialists of India Song, drifting through their sparsely attended embassy parties, trying to replicate salon society in the tropics, cannot hear the voices offscreen of the people they subjugate. Likewise, Suzanna’s anxiety may or may not register some distant tremors. In summer of 1968 her world is sliding into something she isn’t prepared for. Far away from St. Tropez, in Paris students are hoping to find their own beach, but they’re doing it by tearing up the pavement.

Again, thanks to Gerwin Tamsma, Monika Hyatt, Frédérique Nijman, and their colleagues at the International Film Festival Rotterdam for allowing us to visit their event virtually. Here’s to another fifty years of ambitious programming!

A very helpful edition of Suzanna Andler has been published in conjunction with the film’s release. It contains a lot of stimulating background information and critical commentary. Bentley’s comment about “soap opera plus” comes from The Life of the Drama (Applause, 1991), 14. Thanks to Kelley Conway for sharing with me the Jacquot interview in “Réponses à tout,” Libération (14 May 2004), 1.

Jacqout’s rendition of Duras’s play exemplifies what I called in Narration in the Fiction Film “parametric narration.” This rare approach consists of playing out a range of expressive possibilities, scene by scene, in ways that both shape the ongoing plot and “anthologize” sharply contrasting cinematic techniques. Noël Burch first proposed this idea in his enduring Theory of Film Practice (1973), although Eisenstein and Bazin envisioned it. But then they envisioned everything.

P. S. later: The Rotterdam prize winners have been announced (per Variety).

As We Like It (2021).

THE TRIAL OF THE CHICAGO 7: Aaron Sorkin samples the menu

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

DB here:

Love him or hate him, you have to admit that Aaron Sorkin has carved out a unique position in contemporary Hollywood. If we want to understand craft practice from the position of media poetics—that is, the principles governing form, style, and theme in particular historical circumstances—we can usefully look at him as a powerful example.

He’s more than merely typical, of course. In an era when the f-word exchanges of Palm Springs pass muster as comic dialogue, it’s refreshing to watch a movie where smart characters, sparring for high stakes, make a retort that’s more stinging than a slap in the face. These movies are written through and through, and in distinctive ways.

More broadly, Sorkin’s distinctive career invites us to consider the nature of innovation and originality in the popular arts. Because of “progressive” accounts of art history, we’re inclined to emphasize the shock of the (utterly) new as the mainspring of change and the central source of quality. The history of modern painting is written as a series of breakthroughs after Post-Impressionism, from Cézanne through Picasso and Mondrian and so on—the leap to abandon the past, the “next logical step” in an advance toward…what? Abstract Expressionism? Then what? Similarly, from Wagner to Strauss to Schoebberg to Berg to Webern and then…? Boulez? And…?

If the history of an art is a surging procession of avant-gardes, what then do we do with the artists who don’t fit? There are eccentrics, such as Balthus or Satie, who turn out to “point forward” at angles and detours that the linear-progress story doesn’t allow. What about those artists who refine or revise tradition in fresh ways? Where do we put Deineka, recently noticed as no mere Socialist Realist hack, or Shostakovich and Sibelius? Or, in the orthodox history of the detective story (whodunits surpassed by hardboiled), Rex Stout?

In the popular arts particularly, we should expect to find historical patterns less like the Breakthrough Canon, a high-altitude survey of outsize rock formations, than something closer to the ground. Studying mass entertainments like film and popular fiction, we’re likely to find valleys revealing unexpected views of familiar landscapes. There are daisies in the crevices.

In contrast to the Breakthrough account, non-western art traditions valorize accumulation of options and preservation of precedent. An artist earns acclaim for finding fresh ways to realize long-standing craft principles. The Japanese renga poet, the Chinese painter or calligrapher, and the Ottoman carpet weaver revise inherited techniques to reveal new expressive possibilities. Actually, in the West we have the same situation. Come down from the bird’s-eye view, and we’ll see the same fine-grain fluctuations. E. H. Gombrich pointed out how painters, the masters and the minor players, develop their pictures on the basis of inherited patterns—schemas that they have learned and that provide a point of departure for original treatment.

In several places I’ve proposed that filmmakers work with schemas too—pictorial ones, but also narrative ones. The shot/reverse shot technique is a schema, but so is the framed flashback, the four-part plot, and the strategy of beginning your action at a point of crisis.

You see where I’m going with this. Sorkin is worth studying, I think, as a very skilled craftsman. Surveying just a few of his films showed me that he finds ingenious and sometimes powerful ways to rework the schemas from the tradition of American filmmaking—and, of course, from the theatre.

Ventilating the play

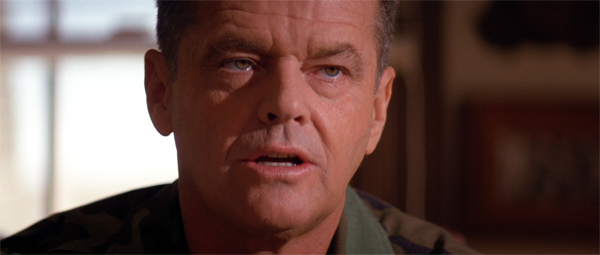

A Few Good Men (1992).

If you want to reach a broad audience in today’s American cinema, you need to either make films with large doses of physical action (as crossover indie directors have found) or to find a signature identity that cultivates a following. In Sorkin’s case, he has dared to rely on plot, dialogue, and a distinct worldview that he has managed to make entertaining. Sorkin’s first plays, followed by the huge stage success of A Few Good Men (1989), typed him as a “theatrical” talent. But over thirty years his film projects sought to “cinematize” what’s usually considered stage technique.

The obvious example is his reliance on “walk and talk,” the long backward tracking shot covering characters striding toward us and spitting out dialogue rapidly. This develops the verbal drama while also yielding some attention-grabbing visuals. But there are less apparent ways Sorkin has blended theatrical technique and cinematic narration.

Early twentieth-century playwrights tended to put the “point of attack”–the moment in the story when you start the play’s plot–fairly close to the climax. Associated with Ibsen and other pioneers of “new theatre,” the late point of attack was a solid convention by the 1910s. As in A Doll’s House and Ghosts, the action starts at a point of crisis, and offstage events leading up to it get revealed through dialogue, sometimes called “continuous exposition.”

The trial schema is a good example of the crisis structure. Typically a trial starts after a lot of stuff has already happened, so the continuous exposition is supplied through testimony and speeches by the defense and prosecution. By 1915, Elmer Rice’s play On Trial was inserting flashbacks that reenacted trial testimony, but some plays stick only to what happens in the courtroom. The Off-Broadway production of A Few Good Men used that linear, present-tense premise, in the vein of earlier plays like The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (1954) and Inherit the Wind (1955). The investigation of the death of a young Marine is pursued by a prosecution team running up against the military code and a couple of hard-headed officers.

But in preparing the film version, Sorkin adapted to the menu of storytelling options on offer in 1990s moviemaking. For instance, the opening scene could be a grabber, a strong moment that aroused curiosity or suspense. (This might have been a reaction to the need to grab the viewer who’d later see the movie on cable or video.) So instead of letting everything be recounted in the trial, Sorkin’s screenplay for A Few Good Men chose an earlier moment in the story action–a literal “point of attack” showing Dawson and Downey assaulting Santiago.

Later, Sorkin ventilates the play in a traditional manner, supplying scenes that present the prosecutors taking the case and investigating the circumstances. The courtroom scenes don’t begin until about an hour into the film, and they alternate with strategy sessions among the legal team and the defendants. The result is a “moving spotlight” narration, mostly attached to Kaffee the lead prosecutor and Lieutenant Commander Joanne Galloway, but ready to shift to other characters.

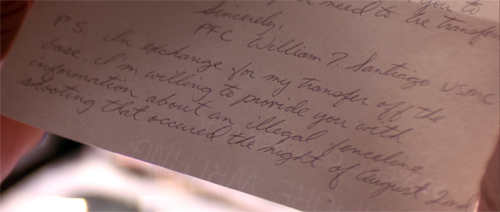

The timeline is chronological, except for a brief flashback dramatizing a letter initially voiced by Santiago. He appeals to Colonel Jessep to transfer him out of the unit for medical reasons. In exchange he offers to give information about an illicit fence-line shooting.

The flashback modulates to Jessep reading the letter aloud (an audio hook) and considering how to handle the situation.

This narration, shifting us from one group of characters to another, gives us a glimpse of the hidden story that the prosecutors need to uncover. The question will become not whether the officers overstepped their authority, but how they will be caught.

After A Few Good Men, we can see Sorkin’s cinematic career as exploring the creative space opened up in the 1990s, a space I’ve tried to map in The Way Hollywood Tells It and several blog entries. For one thing, there’s the matter of how to pick a protagonist.

It seems to me that the film version of A Few Good Men makes Kaffee the protagonist, with Joanne and Sam Weinberg as helpers–just as Jessep is the ultimate antagonist, with Kendrick as his helper. Centering on Kaffee and making him a gifted but glib and cocky young lawyer fits Cruise’s emerging star persona (Top Gun and The Color of Money of 1986, Cocktail of 1988). Sorkin has given us other single-protagonist plots, such as Charlie Wilson’s War (2007), Moneyball (2011), and Steve Jobs (2015).

We may identify Sorkin more with ensemble, or multiple-protagonist, plots because of the fame of his TV shows Sports Night (1998-2000), The West Wing (1999–2006), Studio 60 on the Sunset Strip (2006–2007), and Newsroom (2014-1016). A long-form series permits constant shifting of the protagonist role across a season. But in feature films, I think, a genuine equality among several protagonists is more common in “network narratives” than in crowded films like The Women (1939) and Ocean’s 11 (2001). In the latter, there tends to be a “first among equals”: one or two main characters whose fates are most important, even if subplots centering on others are woven in. Such is the case, I’ll argue, with The Trial of the Chicago 7.

Scanning the menu

Molly’s Game (2017).

Sorkin’s preferred artistic strategies emerge even more clearly, I think, in his handling of narrative structure. He has more or less systematically surveyed a range of storytelling possibilities.

Politically liberal but narratively conservative, The American President (1995) presents an utterly linear plot. As in other romantic comedies, the central couple shares the protagonist role. Their relationships change as they make decisions and respond to external forces. The film plays out the familiar Hollywood double plotline of love versus work: political pragmatism threatens the President’s affair with a lobbyist for environmental reform. There are no flashbacks or fancy time-juggling, and the dialogue is classic flirtation, wisecrack, and one-upsmanship. The one “Fuck you!” becomes a shocking turning point, a test of friendship.

The crisis structure in The American President is presented as a race against time to line up support for two White House bills. Moneyball (2011) creates a comparable pressure on its protagonist. After his baseball team’s loss and the departure of his top players, Billy Beane faces the need to rebuild his roster for the new season. In a classic problem/solution plot layout, he finds a helper in statistician Peter Brand. Again, the plot is mostly linear, though interspersed with summary montages of sports coverage and brief flashbacks to Billy’s own failed ballplaying career.

The fragmentary flashback that carries its own mystery was a common technique of 1990s cinema (e.g., The Fugitive) and remains a standard tool of filmic storytelling. Sorkin’s films use it often, usually to gradually reveals what’s driving the protagonist’s struggle. A version of “continuous exposition,” the flashback allows deeper character revelation; it can liven up the more static sections of the film; and it can provide its own little mystery revelation. In the Moneyball flashbacks we see Billy recruited, decide to give up a college career, and then face failure. This shows how he could have empathy for the second-tier players who are cast aside–and whom Brand’s moneyball algorithms give a second chance.

The time structure is a little more complicated in Charlie Wilson’s War. Here Sorkin samples another option in the schema menu. The story’s crisis is over; the plot starts at the epilogue. After a credits-sequence montage, we’re taken to a CIA awards ceremony, at which Charlie Wilson is honored for working strenuously against the USSR for thirteen years. This scene turns out to be a frame around an extensive flashback.

What follows deflates this high-flown tribute, as we go back to 1980 and see the reprobate congressman pressured into helping the Afghan people by finagling clandestine US investment in fighting the occupying Soviet troops. Other subplots, including an investigation of Charlie’s partying ways, are interwoven. The long flashback concludes and the film’s final sequence returns to the ceremony, with a replay of a grinning Charlie getting his award. The ABA structure makes the whole public event a charade, underscored by a final title: “And then we fucked up the endgame.”

By contrast, Molly’s Game is more fragmentary. We start with a teenage Molly Bloom in a skiing competition qualifying for the Olympics, but an accident knocks her out of the running. This early passage is in turn interrupted by brief flashbacks to earlier in her childhood, of other competitions and accidents and recoveries, overseen by her demanding father. Her first-person voice-over fills in the background, echoing the fact that the story is drawn from the book she’s written (both in real life and in the film).

“None of this has anything to do with poker,” a title ironically informs us, but it’s a tease. This prologue, mixing scenes from phases of Molly’s girlhood, characterizes her as having tenacity, determination, and not a little rage at her dad. Then the present-day action starts, as usual at a crisis. Molly is wakened from sleep by the FBI arresting her for illegal gambling. What has happened in the meantime? Even after the scene of her arrest, the film’s narration wedges in a VHS interview with young Molly in which she’s asked about her goals.

The revelation of the formative years, saved for late in Moneyball, is put up front in Molly’s Game. But now there’s a mystery: How does a promising athlete become a gambling queen?

The question is answered through another series of time shifts, and these occupy the bulk of the film. After Molly’s arrest, the narration fills in her arrival in Los Angeles and her job working for a sleazy entrepreneur who arranges poker games for rich men. Her rise in the world of underground gambling is intercut with present-time scenes of her consulting an attorney to take her case–a risky proposition, since her customers include Russian mafia. And the alternation of her legal problems and her gambling career continue to be interrupted by flashbacks to her as a little girl, as a teenager, and as witness to her father’s infidelities.

Sorkin has layered his plot within several time zones: present, immediate past, and distant past, with the earliest one including scenes scrambled out of chronological order. Again, the purpose is to reveal character motivation. The flashbacks suggest sources of Molly’s decision to triumph over weak men–perhaps, it’s suggested, as revenge for her father’s mistreatment of her and her mother. The time jumps also reveal her as a fierce competitor unwilling to give in. Athletics, it turns out, has a lot to do with poker.

The network as character prism

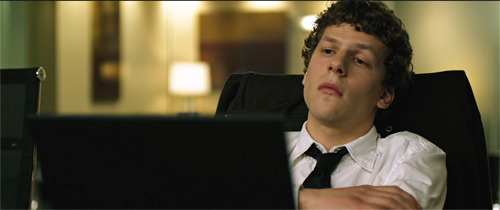

The Social Network (2010).

If there were a simple progress in Sorkin’s exploration of the menu of options, you’d expect that The Social Network would come later than it does. Yet before Molly’s Game yielded three principal time layers (the legal case, the career rise, the girlhood), Sorkin’s screenplay tracing the rise of Facebook had already fielded something more complicated than that.

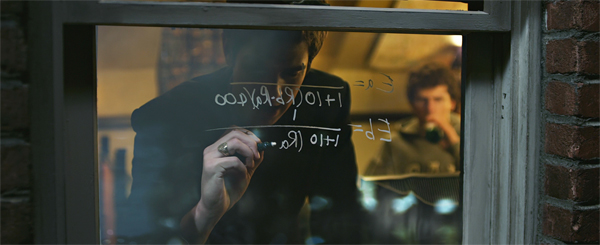

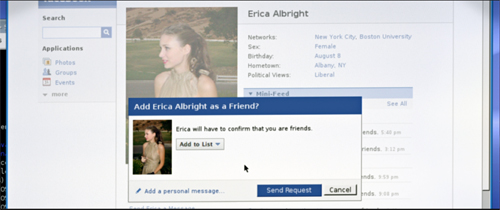

Still trying variants, Sorkin this time puts the motivating moment, the incident that drives the character, at the front of the film. In 2003, Mark Zuckerberg is on a date with Erica Albright. His arrogance provokes her to break up with him. In a burst of pique, he turns a blog into a page that denounces her and asks readers to rate local women. With the reluctant help of his friend Eduardo Savarin, the site crashes the Harvard server and Mark faces disciplinary action.

At this point the film splits into more time-tracks, again transmitted through legal proceedings. The Harvard disciplinary hearing is filtered through a deposition responding to Eduardo’s lawsuit against Mark, long after their partnership has collapsed. Sorkin could have picked this testimony as his point of attack for opening the film, then flashed back to the origins of the suit. Instead, like Molly’s Game, The Social Network starts its plot in the past, skips ahead to the future, and then fills in more of the past.

A second lawsuit is in progress, this time from the Winklevoss twins, and a second string of deposition scenes. Apparently more or less simultaneous with the Eduardo sessions, these also anchor us in an approximate present and cue up incidents in the past. For instance, in a past scene, after an ally of the twins tells of Mark’s successful webpage, the narration cuts to the opening of the Winklevoss case’s depositions, and then back to the brothers recruiting Mark to work on their project.

The dual-track depositions in the present allow Sorkin not only to segue into illustrative scenes in the past, but also to set up crosstalk between the two lawsuits. Immediately after Mark dodges questions from the Winklevii, we see him dodge questions in Eduardo’s session.

By the 2000s, audiences trained in the time-shifting of the 1990s could follow these quick alternations. It’s also up to the director to keep us oriented through differences in costume, angle, lighting, color design, and other elements.

If you take the opening portion as what sets the narrative Now, you could call the deposition scenes flashforwards. Alternatively, you might consider those scenes as Now, although the opening orientation to them has been deleted. Either way, Sorkin has provided a flexible, dynamic structure that allows us to study Mark’s behavior and others’ responses to it.

One of the dreams of storytellers who embraced multiple-viewpoint plots was the idea of letting us see different, even contradictory facets of a character. The prospect was broached by Henry James (in his novel The Awkward Age) and Joseph Conrad (in Lord Jim, Chance, and other books). On the stage, Sophie Treadwell had experimented with it in The Eye of the Beholder (1919). Herman Mankiewicz and Orson Welles played with the possibility of such a “prismatic” narration in Citizen Kane, perhaps as a result of Mankiewicz’s unproduced play about John Dillinger.

By using the trial schema a storyteller can present a character’s public self-presentation, the impression management that tries to win adherence. But the fact that different people testify about a situation also offers prismatic possibilities. Here, the chief contrast is between Mark’s snotty recalcitrance at the counsel table and his swagger in the past.

During the film’s opening, when Mark confides in Erica and Eduardo, we’re about as close to penetrating his mind as we’ll get in the film. Later the film’s narration offers less a study in how his mind works than a portrait of how he handles people–his social survival strategies. The range runs from sheer bluster, as when he tries to overwhelm Erica, through awkward acceptance of class ambition when he meets the Winkleviii, to evasion, threats, and bumbling efforts at friendship. At the end, he goes flat and legalistic, telling Eduardo: “You signed the papers.” The film’s denouement arrives when Eduardo’s lawsuit is launched. “Lawyer up, asshole.”

The opening sections began in the past, but the ending leaves us hanging in the present. At a pause in Eduardo’s suit, the film concludes on the image of blank-faced Mark staring at his monitor. Isolated by his betrayal of the one person close enough to have been a friend, he’s checking Erica’s Facebook page.

This conclusion lets us imagine that sexual and romantic frustration, exposed in the opening, have reinforced Mark’s low-affect aggressiveness. It’s also a suggestion that his slightly vampirish predation suits him for the age of the social network. But we’ll never be sure, because his disdainful indifference is his armor against everyone he encounters.

As with Molly’s Game, this cluster of parallel timelines is intelligible and forceful as a revision of a schema (present/ past/ present) that we know well. And careful cutting, sound work, and performance have kept us on track throughout.

End to end control

Steve Jobs (2015).

In films that don’t rely on chases, fights, explosions, time travel, fantasy, or extraterrestrials, what can hold your interest? For one thing, snappy talk. The old theatre adage claims that dialogue needs to do one of three things: advance the action, delineate the characters, or add humor. Sorkin’s dialogue does all of them at once.

Steve Jobs is braced by his assistant Joanna while he frets over a press story.

“’The only thing Apple’s providing now is leadership in colors.’”

“Don’t worry about it.”

“What does Bill Gates have against me?”

“I don’t know, you’re both out of your minds. Listen to me–”

“He dropped out of a better school than I dropped out of . . . but he is a tool bag and I’ll tell you why.”

“Make everything all right with Lisa.”

“You know–Joanna–boundaries.”

“You’ve come to my apartment at 1 AM and cleaned it, so tell me where the boundary is.”

“There, let’s say it’s there.”

“If I give you some real projections, will you promise not to repeat them from the stage?”

“What do you mean real projections? What have you been giving me?”

“Conservative projections.”

“Marketing’s been lying to me?”

“We’ve been managing expectations so that you don’t not.”

“What are the real projections?”

“We’re going to sell a million units in the first ninety days. Twenty thousand a month after that.”

Each reply shows that a strong line is like an arrow–feathered at the top, barbed at the tip. If your conflict is psychological, then the last part of the line should land with a punch. “We’ve been managing expectations so you don’t not.”

But the lines don’t exist in isolation. Every stretch of the film is a vivid lesson in whipping together bits of earlier conflicts, jumping from one to another as Jobs parries and ducks and changes the subject, all the while tension rises. One issue is picked up (Steve’s reaction to press coverage), interrupted by others (his rivalry with Gates, his friction with his daughter), followed up by a long-running relation with Joanna (“boundaries”), then a big piece of information: one goal, a sales target set in the first segment, has been achieved. But the others are left dangling, to be revisited, and we are looking forward to that.

This sort of repartee brings back the era of snappy chatter. The exchanges recall the films set in rehearsal halls (Footlight Parade), news offices (His Girl Friday), movie studios (Boy Meets Girl), gangster cafes (All Through the Night), and even a research institute (Ball of Fire). A few films of recent years, such as The Paper, successfully recapture the exhilaration of such fast, pungent dialogue. Sorkin delivers it consistently.

Steve Jobs is one of Sorkin’s most structurally ambitious projects. Here he tries out another menu item, that of block construction. In this layout, we get two or more marked-off chunks or chapters, sometimes without the same characters. Block construction came into fashion with Mystery Train (1989), Slacker (1990), and other indie works, and it remains a basic resource for Tarantino and Wes Anderson.

As ever, Sorkin rewrites the block premise as a drama convention, the division into spatially and temporally confined acts. The plot of Steve Jobs is organized around three public product launches: in 1984 (the Macintosh), 1988 (the NeXT Black Cube), and 1998 (the iMac). Each event teems with crises large and small, public and private. They’re all parallel, in that we see the few minutes of preparation leading up to the curtain-raising. Like a party or restaurant scene in a play, a product launch offers a confined space in which characters and story lines can mingle. The pressure of a product demo allows Sorkin to create deadlines and motivate many walk-and-talk passages through backstage corridors.

Just as theatrical is the flow of people into and out of Steve’s presence. From act to act the same associates are ushered into Steve’s presence: his former romantic partner Chrisann, his business partner Steve Wozniak, John Sculley, engineer Andy Hertzfeld, a journalist, and Lisa, the daughter that Steve is reluctant to acknowledge. The French phrase liaison des scènes, “scene linkage,” captures the way that within a single setting characters’ entrances and exits break the act into distinct pieces.

In addition, Sorkin doesn’t confine his time frame to the duration of the demos. As in other films, flashbacks interrupt the present. The 1984 segment uses only one flashback, a visit to garage-hacking days that sets up the dispute about open and close architecture. The flashbacks thicken in the second segment, which reveals the conflict that led Steve to break off with Sculley. That quarrel in the past is tightly crosscut with their confrontation in the present, and as the tension builds one man in the present is replying to an objection in the past. This rapid pacing is one way a “theatrical” premise can hold an audience accustomed to action movies.

Like Fincher’s intercut depositions in The Social Network, Danny Boyle’s handling keeps us oriented through staging, costume, color, lighting, and shot/ reverse shot eyelines.

The block most saturated with flashbacks is the third, the one launching the computer that brought Apple to marketplace triumph. This chapter incorporates glimpses of scenes shown in the first two segments, along with revelations of Steve’s first approach to Sculley. This last recollection is prompted by his admission that he long ago found the biological father who gave him up for adoption. (Many of Sorkin’s protagonists have Daddy Issues.) Again, a big revelation about character motivation is saved for a flashback late in the film.

In addition, other crises come to a head. Steve appears to break definitively with Wozniak, and he reconciles with Lisa, whom he hasn’t, after all these years, fully taken into his life. As he achieves his goals–a successful computer at last, a settling with Wozniak and Andy, and a tentative accceptance of Lisa–he displays more chastened and cautious behavior. He has admitted his fallibility (he was wrong about the Time cover), he has realized what he lost in challenging and trashing Sculley, and he’s ready to move to the next challenge (“music in your pocket”). True, he treats Woz brutally, but Woz gets the final word: “It’s not binary. You can be gifted and decent at the same time.” Steve doesn’t change completely; he just gets a bit more human.

Interestingly, these cadences fit the four-part structure that Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood has revealed governing many classical plots: Setup, Complicating Action, Development, and Climax, followed by an epilogue or tag. Sorkin has “cinematized” his three “acts” by letting the final one harbor Development, Climax, and an epilogue.

Kristin also points out that classical film story telling relies on motifs that weave their way through the film. Not only music but lines of dialogue and images recur to point up repeated actions, indicate changes in character, or add humor. (A running gag is a comic motif.) Yet movies didn’t invent this tactic. Novels, poems, and plays rely on recurring motifs. Macbeth circulates imagery of blood and ill-fitting garments, while The Importance of Being Earnest wrings a lot out of the mysterious word “Bunbury.”

Steve Jobs is packed with motifs, far more than most movies I can think of. Some bounce around one segment and into another, and several come back at intervals in all three. All the characters relitigate old complaints, and Steve masterfully deflects a conversation by returning to remarks he’s made before. Here’s a partial list of items that are recycled again and again.

Starting exactly on time, the controversial SuperBowl ad, the need to turn off the Exit signs, a bottle of ’55 Margot, the Time cover, the purported treachery of Dan Kottke, “a million in the first 90 days,” “I don’t have a daughter,” 28%, Woz’s request to acknowledge the Apple II, “playing the orchestra,” closed versus open systems, the name Lisa, “end to end control,” 2001, “a dent in the universe,” slots, Pepsi, the psychology of adopted kids, “You get a pass,” the threat of a press release, and “which Andy?”

For Sorkin, even “Fuck you” becomes a motif rather than a space-filler.

A significant cluster involves the arts, particularly music and painting. In their quarrel the two Steves compare themselves to the Beatles, and Bob Dylan’s image and songs float through the movie. This association with the arts helps offset the unpleasant side of Jobs’ temperament, his crisp, frosty bullying of others and his relentless imposition of his “reality distortion field.”

Another motif softens him a bit: his desire to bring computing to kids. The prologue, in which Arthur C. Clarke is interviewed about the future of computing, sets up several motifs–the idea of separating oneself from others (Steve in a nutshell), the importance of home (associated with Chrisann’s demands), and particularly childhood. The reporter interviewing Clarke has brought his boy along, and they discuss how a new generation will quickly grasp the power of personal computing.

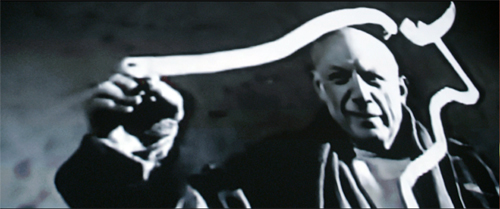

That motif is dramatized when, at first indifferent to five-year-old Lisa, Steve uses her as a demo to show Chrisann what the Mac can do. But his interest rises when Lisa intuitively understands that she can draw with it. “Lisa made a painting on the Mac,” he says thoughtfully. He seems to realize that she could be his brainy daughter, and he resolves to put her in a good school. Her drawing looks forward to Picasso’s swooping dab at a bull in the climactic montage of the 1998 launch.

The ping-ponging motifs are mostly in the dialogue, though. They push the action forward, recall earlier moments, and characterize the combatants while also yielding some laughs. Above all, the motifs chart Jobs’ character arc. We know that he’s more committed to Lisa at the end when he breaks his routine and says he’s willing to start the performance late. Soon he will reveal that he has saved her painting to give to her.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It I call Jerry Maguire a “hyperclassical” movie–more classical than it needs to be, flaunting a virtuosity of construction and motivic echo. I vote for Steve Jobs as another instance. Sorkin has used cinema to multiply motifs to a higher power.

Exporting ideas across state lines

The Trial of the Chicago 7.

One innovation of turn-the-century-theatre was the so-called “drama of ideas” or “problem play.” Ibsen, John Galsworthy, and Bernard Shaw sought to break away from standard intrigues of mystery and romance in order to dramatize women’s rights, labor struggles, and other social issues. Sorkin, with his liberal political bent, has brought that legacy to his film work. The subjects and themes he tackles have become as distinctive a marker of his work as any strategies of form and style.To be more precise, his formal and stylistic strategies work upon the ideas he wants to put forth.

How much private life is a US President entitled to? What is the duty of a politician who wants to enact social change? For a tech entrepreneur, where does idealism end and domination begin? Why should a woman not be able to compete on equal terms with men? Does social change come best through reform (reason, the ballot box) or revolution (change of consciousness)? Something like this last occupies him in The Trial of the Chicago 7.

The problem at the center of the film is: How to protest, and eventually stop, US involvement in the Vietnam war? The film’s prologue and epilogue announce the sweep of the issue. It begins with President Johnson ramping up troop commitments and establishing the draft lottery, all during a wave of assassinations. The film ends with Tom Hayden reading out the names of troops who have died while the trial was dragging on. Early on, Rennie Davis establishes the list because it’s “who this is about.”

The defendants in the trial are only loosely associated. Bobby Seale doesn’t know the others and was in Chicago just four hours; he’s also denied counsel. Sorkin carves out two major factions. Tom Hayden and Rennie Davis, as student activists out of SDS, are presented as preppy intellectuals, committed to antiwar action within the frame of protest and legal debate. Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, associated with the Yippies, are countercultural provocateurs. They anticipate a spectacle of innocence attacked by those in power. They will show the Chicago Democratic convention to be staged, as Walter Cronkite says at the end of the opening montage, in “a police state.”

Although Tom’s and Abbie’s factions communicate a little before the events, it’s the pressure of circumstances in Grant Park that pushes them into dispute. Alongside them Sorkin develops subplots that suggest other political alignments. David Dellenger’s commitment to nonviolence is tested by the flagrant repression of Bobby Seale. Richard Schultz goes along with orders to prosecute, knowing that the case is trumped up. Jerry Rubin falls briefly in love with an undercover policewoman. Fred Hampton tries to help Seale, only to be killed. Attorney William Kunstler discovers that he has a surprise witness to call. Editor Richard Baumgarten notes that in cutting all these lines of action together: “I feel like one of the great successes of how this film unfolds is that each of the characters does have a moment, or multiple moments.”

Tom and Abbie emerge as the “first among equals” because they most sharply articulate alternative accounts of what they’re facing. They aren’t dual protagonists, like a romantic couple tackling common problems. They’re at odds throughout. On the first day when Tom tries to get agreement on goals, Abbie challenges him.

Early court scenes show Tom annoyed by Abbie’s antics, but neither is really an antagonist for the other. Tom can half-humorously admit that he got a haircut to impress the judge, and clearly Abbie admires Tom. The antagonists are the government prosecutors and Judge Hoffman. Tom and Abbie function as what Kristin calls parallel protagonists. Like Mozart and Salieri in Amadeus, or Captain Ramius and Jack Ryan in The Hunt for Red October, they are at once opposed to one another and fascinated by each other. They both compete and cooperate.

What does each one want? This will become part of the drama’s problem, because the two men will be charged with coming to Chicago to stir up violence. Sorkin shrewdly postpones the question in the opening montage that brings some main players together through crosscutting. Incomplete dialogue hooks make their goals somewhat mysterious.

Tom: Young people will go to Chicago to show our solidarity, to show our disgust, but most importantly–

Abbie: –to get laid by someone you just met. . . .We’re going peacefully, but if we’re met there with violence, you better believe we’re gonna meet that violence with–

Dellenger: –non-violence. Always non-violence and that’s without exception. . . . (asking his son what to do in the face of police:)

Dellenger’s son: Very calmly and very politely–

Bobby Seale: –Fuck the motherfuckers up!

Seale’s capper would seem to negate the nonviolence of Dellenger’s position, but at the end of the montage Bobby refuses the pistol his colleague Sandra offers him. “If I knew how to use that, I wouldn’t need to make speeches.”

Unlike Dellenger, he’ll hit back if attacked first. So now only the positions of Tom and Abbie remain undefined.

Eventually, Tom exposes his rationale. If they can prove they were peaceful demonstrators within their rights, it will help “to end the war and not fuck around.” That demands treating the trial seriously. “We as a generation are serious people.” And he doesn’t want to raise police culpability. “We’re protesting the war, not the cops.”

From the start Abbie insists that the trial isn’t a matter of law but of contingency. “This is a political trial.” They were chosen to be examples, and the two lesser defendants are “give-backs,” people the jury can let off with a clear conscience. Abbie and Jerry came to Chicago knowing that police violence was very likely. (Cronkite said so too.) The best way to prove state oppression is to lay it bare, preferably with gonzo humor. After all, the whole world is watching.

The film’s structure supports Abbie’s analysis. Sorkin’s narration, using a moving-spotlight approach, has from the start tipped us that Attorney General John Mitchell has ordered Schultz to prosecute the 7 on flimsy grounds. Mitchell, a spiteful conservative, wants to crush antiwar protest, but he’s also petty. He’s miffed that Johnson’s AG Ramsey Clark insulted him on the way out of office. Mitchell has assembled a mixed bag of antiwar activists to charge with conspiracy. (In an ironic twist, they conspire most successfully after they have been thrown together for trial.)

So the problem play becomes a progress toward understanding political power. Tom Hayden (and to a lesser degree Kunstler) come to grasp the reality of an engineered police provocation and a show trial. Abbie’s privileged insight is further stressed by the fact that he’s the only character given a narrator role. Sorkin interrupts the trial with shots of Abbie at a mike in a club, telling the story of the fights during the riots, correcting the false testimony of the cops. In stage tradition, Abbie is the raisonneur, the explainer.

The conflict between Tom and Abbie gets specified gradually, sharpened in strategy sessions where Tom berates the Yippie contingent for clowning. If progressive politics is branded as childishness, “We’ll lose elections.” Abbie calmly replies that “We’re going to jail for who we are.” The debates are about tactics as well. Tom wants the demonstration to keep away from the convention hall, while Abbie insists that they go downtown. As it turns out, the police squeeze them out of the park and force them into a trap that yields the spectacle that Abbie and Jerry anticipated.

Through crosscutting Sorkin again creates several layers of time: the runup to the convention, the protests themselves, the trial, and a more unspecified moment when Abbie is at the microphone narrating. More linear than the time mosaics of Molly’s Game and Steve Jobs, the Chicago 7 array might seem a step back toward the classic trial schema. Basically, the court proceedings frame the flashbacks to the purported crimes.

The relative linearity is needed, however, to allow us to chart the progress of the parallel protagonists. In a neat balancing act, Sorkin dramatizes character change with Tom Hayden and character revelation with Abbie Hoffman.

Hayden’s character arc traces his realization that the trial is rigged. He has brought table manners to a revolution. He presents a wholesome appearance, and when pressed by Bobby he half-admits he’s rebelling against his upbringing. (Daddy Issues again.) Even his “reflex” action of rising when His Honor enters, violating the pact among the 7, shows that the impulse to behave well is struggling against his sincere urge to end the war through citizen action.

Yet Tom has an outlaw side as well. He releases the air from the tire of a cop car to allow Rennie to escape surveillance. At the climax, seeing Rennie beaten, he calls for blood to flow through the city–not, he tries to explain, the blood of others, but the blood freely given by the protesters. Still, he joins forces with Abbie, Jerry, and Dellenger as they are lured onto the footbridge and into the cops’ trap. The cops, having choreographed the street assembly, push them through the tavern window.

Tom, our main viewpoint vessel in the film, also visits Ramsey Clark with his attorneys. It’s then that he realizes the trial is Mitchell’s political charade aiming to override Clark’s decision not to prosecute the demonstrators. So, after Clark has testified (and sees his testimony suppressed by Judge Hoffman), Tom can redeem himself.

Judge Hoffman has offered Tom clemency before he makes his final statement. The good boy who had asked, “Why antagonize the judge?” rises in polite defiance to read the names of the dead. He will take the same punishment meted out to the others. He now understands revolution as spectacle.

So there’s a little of Abbie in Tom. In the same final stretches of the film, we learn that there’s a little of Tom in Abbie. Tom had planned to testify, but he can’t justify what he said on tape. So Abbie takes the stand. His slapstick persona drops. Behind the Jewish Afro and the wisecracks is revealed an intellectual who can quote the New Testament and gently praise Tom as a patriot. Schultz questions him: Was he hoping for a confrontation with the police? “I’ve never been on trial for my thoughts before.”

As in the opening montage, Sorkin cuts away before Abbie answers, and his pause and grave demeanor let us consider that for all his bravado, he has regrets about the crisis he saw coming.

Like any problem play, The Trial of the Chicago 7 can be criticized for stacking the deck, or oversimplifying, or recasting the problem in ways that favor certain interests (e.g., white college-educated men). But that critique is the risk artists run all the time, even in the most anodyne “nonpolitical” work. If critics study how films achieve their effects, viewers can be more aware of how the schemas we know are shaped by the movies we see and get a clearer sense of means and ends, purposes and fulfillment.

At the same time, artisanal skill in a robust tradition is intrinsically worth analysis. That analysis can reveal new possibilities in what cinema can do. In The Trial of the Chicago 7 Sorkin creates a dramaturgy that embodies ideas in characters’ conflicts, changes, and hidden facets. Once more a theatrical premise has been turned into classically constructed cinema. Sorkin’s work offers one way that this tradition can stay fresh–not through shocking breakthroughs but by highly skilled reworking of schemas accessible to a broad audience. You know, the way theatre used to be.

Thanks to conversations with Kristin and Jeff Smith, who helped me clarify my ideas.

For more background on this sort of narrative analysis, there’s a synoptic blog entry here. This earlier one might also be of use. Rory Kelly offers some nuanced analysis of the Hollywood character arc.

Cinema’s debts to theatre are considered in this entry, and some others in the category Film and other media. On the power of artisanal care, there’s this on Buster Scruggs.

Another entry discusses how actors use their faces in The Social Network.

P. S. 5 March 2021: I’ve just found some interesting remarks from Sorkin about what he calls “the puppy crate”–the need to focus a drama in a confined time and space. The Trial of the Chicago 7 is an obvious example, but so too is Steve Jobs. “I need four walls really badly.”

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

Borat: Keep it stupid, simple

Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan (2020).

DB here:

Defending some of his wildest films, Hong Kong director Tsui Hark pointed out: “Sometimes it’s fun to be stupid.” True enough. But we need to be stupid in sync. When a leader is being stupid and only some of our fellow citizens are, it’s a lot less fun.

The situation invites you to respond with meta-stupidity: Showing how invincibly stupid others are being by doing something stupid yourself. One option is silly satire (Saturday Night Live), but there’s a more deeply disturbing alternative. You can be stupid in a savage, no-holds-barred way.

This can disturb your audience. Shock defeats geniality, obliterates wit. You get called heavy-handed, on-the-nose, over-the-top, and other hyphenated things. You may even move into the realm of the grotesque.

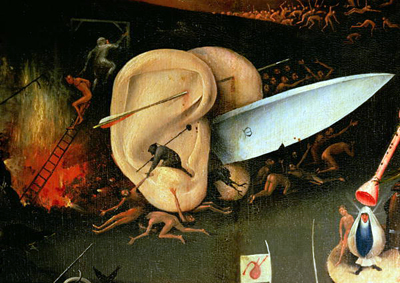

Blunt, tasteless, outrageous grotesquerie has been an important artistic strategy through the millennia. Bosch (below), Bruegel (next), Goya, and other artists have taken exquisite pains to present giddy images of human folly, bursting the limits of taste and sense.

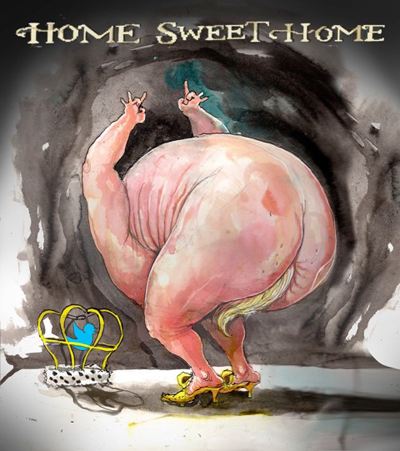

Unsurprisingly, in America the grotesque flourished during the 1960s, in Robert Crumb comix and Paul Krassner’s Disney orgy. Nowadays, Australia’s David Rowe has done fastidious work with slack jaws, skin blotches, and, inevitably, flab.

The realm of the stupid grotesque is one that Sacha Baron Cohen has made particularly his own. It suits our moment.

Friction between parts

The Republican Party’s steamrolling takeover of civil society, begun in earnest in the 1980s but turbocharged under Trump, has created a Golden Age of American agitprop. Responding to the lava flows of vile, vacuous sludge on social media, carefully crafted counterstrikes have shown a fair bit of wit. Call it the spontaneous genius of the American people. That usually comes down to jaunty disrespect.

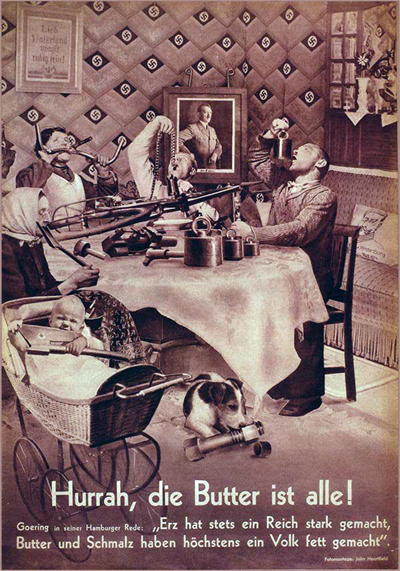

Caricature is the go-to format for those who can draw. But it’s striking that the photomontage techniques of John Heartfield, aimed at an earlier Reich, have been revived for the Age of Trump. Below, Heartfield’s 1933 portrait of Goering as butcher of the Reischstag, alongside an ailing Trump.

Photoshop makes the craft of photomontage easier than in earlier eras, but the trick is still to have an ingenious idea–a play on words, or a reference to a meme. Heartfield’s famous “Hurrah, the Butter’s All Gone!” defiles the guns-vs.-butter motto of classical economics by suggesting that we’re foolish enough to think we can survive on instruments of death. It also quotes Goering’s speech: “Iron has always made an empire strong, butter and lard have, at best, made a people fat.” While suggesting that Hitler’s followers have a hearty appetite for self-destruction, Heartfield has shrewdly created metaphors: handlebars like a corncob, a bandolier like spaghetti, a bomb like a coffeepot, a grenade serving as a doggy’s bone. The baby teething on an axe-blade is a bonus, as are the sprightly swastikas in the wallpaper.

In the gentler example, Trump isn’t just any baby, he’s the kid in Home Alone (covert reference to his cameo in the sequel), with the invaders as both the Blump and, for once, a smiling Bob Mueller.

Note that these aren’t deepfakes, undetectable blends. Montage promotes friction between parts. The juxtaposition bears the traces of the act of bringing disparate pieces together. (Trump’s hands are plausibly small, but that icebag is an awkward fit.) The pieces create a coherent spatial layout, but there’s enough mismatch to remind you of the act of assemblage.

Of course montage is also a film technique, and sometimes–as with the Soviet films of the 1920s, or found-footage films like those by Bruce Conner–we sense a jolt or abrasion between shots. By and large, though, a film like Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan is less an exercise in montage (despite all its jump cuts) than a faux-documentary mixing the casual norms of prosumer video and quickie tabloid-crime cable fodder.

Instead of the relatively softball treatment of POTUS seen in my images, Borat Subsequent Moviefilm gives us something much closer to Heartfield’s blood and bombs. As in a photomontage, bits of reality are turned into a cartoon that’s outrageous, even offensive. But like Heartfield, Baron Cohen reminds us of one crucial point. Fascism promises to make stupidity fun.

Just another movie?

Spoilers ahead, of course.

The grotesque is usually associated with deformation, but Borat Subsequent Moviefilm has a firm structure. At the risk of sounding silly, I insist that it’s a surprisingly tightly-knit classically conceived film.

The hero starts off with a goal. Ex-journalist Borat Margaret Sagdiyev will get a reprieve from penal labor if he will deliver Johnny the Monkey as a bribe to well-known “pussy hound” Mike Pence. Borat’s daughter Tutar joins Borat in the US by smuggling herself into Johnny’s cargo crate, and because she has eaten Johnny, she must replace him as Pence’s bride.

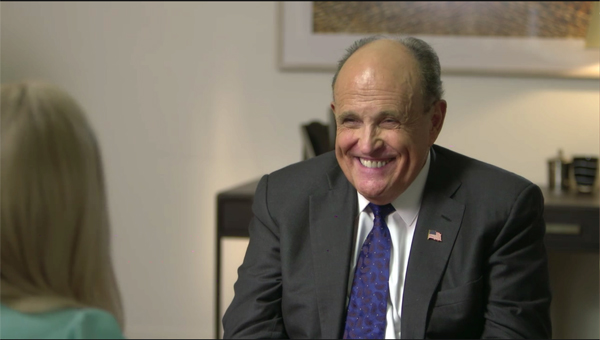

The film falls into the familiar four parts. The setup introduces Borat’s goal and peaks at the invasion of CPAC. As usual, the development section that follows redefines the initial goal. Turned away by Pence’s guards, Borat gets his boss’s permission to offer Tutar to Rudy Giuliani instead. This goal forms the through-line for the rest of the film, as Borat undertakes to make over Tutar into a submissive American woman.

The third section is occupied with various delays and stretches of character change. Tutar starts to liberate herself from Kazach patriarchy and Borat comes to accept his daughter as a person. At the climax, when Tutar decides to offer herself to Giuliani to save her father, he races to rescue her–prepared to sacrifice himself to save her from violation. The epilogue celebrates a new stability with a happy ending, if a worldwide pandemic counts.

The main thread is the familiar device of the naive traveler, the alien who reminds us of how strange our everyday world can seem to an outsider. Borat is introduced to smartphones (though he never figures out the camera), cyberporn, plastic surgery, QAnon, and Covid-19. Tutar learns that her vagina will not chomp her arm, that women can drive cars, and that fathers can walk hand in hand with their daughters.

As in a traditional film recurring motifs–raw onions, a chocolate cake, a plastic baby, strings in the brain–bind the scenes together. Stylistically, the apparently offhand shooting displays classic camera ubiquity. We always have the best view because multiple setups are covering the action (something not common in a true documentary), and probably scenes are retaken. Matches on action are the giveaway.

Many of the scenes, particularly those involving crowds at right-wing events, are made to cohere through the Kuleshov effect. Editing allows Pence to appear to react (stonily) to Borat’s appearance in a Trump fatsuit at the back of the hall.

Think Rudy really inspected these pages of Tutar’s book? He is very moved by receiving it.

And there’s a nice homage to Griffith-style crosscutting, when Borat scrambles to rescue Tutar from the clutches of America’s Mayor.

I grant that Borat Subsequent Moviefilm seems pretty episodic when you watch it, but I suspect that’s partly because of the inherent looseness of a road-movie plot, and partly because of the shock effect of individual scenes. That shock depends, I think, on the relentless grotesquerie on display. Classical clarity of presentation enables the film to chart two major types of stupidity at large in our world.

Leering in bestial degradation

The aesthetic of the grotesque centers on fanciful but disturbing deformation, an exaggeration that’s at once playful and threatening. Art critic John Ruskin, describing the carved heads he found on the Bridge of Sighs in Venice, was appalled to see them “leering in bestial degradation.” That’s not a bad description of Borat Subsequent Moviefilm. The operative word, of course, is leering. The grotesque, as James Naremore points out, mixes fear, disgust, and laughter.

The grotesque breaks categories. Borat’s main disguises as a spare-tired redneck make him implausibly cartoonish. Animals become human (Johnny the chimp is a porn star) and humans become animals, or simply raw material. The producer of Borat’s previous film has been turned into an armchair, with privates preserved.

Species transmogrify. Borat himself–hugely tall, loping like a moose, shitting in front of Trump Tower, with his inane grin and wobbly vocal pitches, high-fiving with hands like seal flippers–is a walking graffito, something you might see scrawled on a remote East European grotto. Tutar, like all Kazakh daughters, is kept in a cage. Grotesque art also breaks taboos. The film wallows in menstruation, incest, masturbation, animated POTUS erections, kinky birth stories, and sex toys, including a gag that pivots on Borat’s accent (Amazon delivers “fleshlights” instead of flashlights). In this context, Rudy Giuliani’s 1200-watt smile becomes wolfishly sinister.

Again, though, narrative processes provide some development. Tutar abandons her cage and (in a sign that Borat is warming to her) joins her dad in the trailer. She becomes a high-gloss Fox-babe interviewer. Borat correspondingly submits to a gender revision, showing up in a bikini to save her from Giuliani. The armor-plated gender roles assigned by Kazakh culture melt a bit in Borat’s odyssey, though again–faithful to the grotesque–father and daughter’s final slow-mo romp through Washington streets is less a lyrical reconciliation after two “character arcs” complete than another bit of tawdry public cosplay.

Eisenstein thought that the grotesque had two registers, the comic (say, slapstick) and the pathetic (say, The Hunchback of Notre Dame). So you could argue that the Borat film moves broadly from the first to settle on the second. In the very last scene, there’s even a hug as a “normalized” Tutar and Borat assume meritocratic professional identities.

Still, this normalization doesn’t really wipe away a cruel Boschian vision of a hellscape seething with grotesques. The film sets up two parallel cultures, Kazakhstan and the USA, each deeply committed to imposing stupidity on its populace.

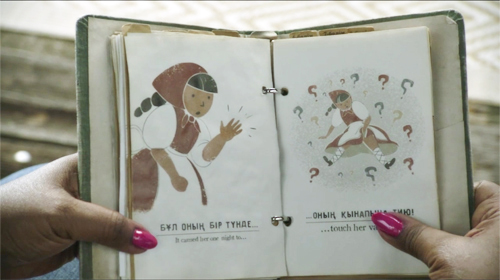

Kazakhstan is a parody of traditional folk patriarchy as recast by a Communist state. Fathers treat daughters as livestock while corrupt officials execute their enemies. Social life is ruled by a guidebook that Tutar dutifully carries everywhere. It details all the powers due to men and all the roles allotted to women, with special instructions about areas they must not touch.

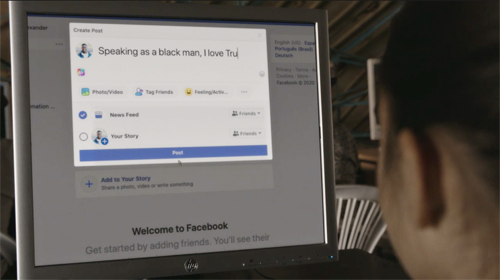

The USA, for all its wealth, is filled almost completely with deadpan imbeciles who advise Borat on how to cage his daughter and gas gypsies. Women instruct Tutar in finding a sugar daddy and behaving at a debs’ ball. True, Tutar learns that the Kazakh manual is bunk, but her new vessel of truth is Facebook, which assures her that the Holocaust didn’t happen.

Armed only with a barbaric yawp, Borat visits anonymous malls and bland bakeries. This moronic inferno houses the pious women of a Republican club, the well-heeled attenders of a CPAC meeting, and Gadsden flag-wavers. As the virus spikes, Borat takes refuge with conspiracy theorists who claim that the Clintons drain children’s adrenaline and feast on blood. Crashing a Second Amendment rally, Borat can quickly teach the audience a song which urges that members of the press be chopped up “like the Saudis do.”

Does an elderly Jewish woman provide a glint of light? After all, she assures Borat that the Holocaust really happened. But the twist is that he’s comforted because her news vindicates his countrymen’s historic role working in the camps. And the image remains pure grotesquerie: a Nosferatu-like Borat measures the lady’s nose, in an echo of the visit to the obliging plastic surgeon who discusses Jewish noses.

If the Kazakhs have been regimented in the service of the state, the American social default is freewheeling, blank indifference. You can tell someone you’re chaining up your daughter, you can send a penis image by fax, you can walk into a conservative gathering in KKK robes, and at best people raise an eyebrow. Stupidity is stolidity. Behind every reaction shot is the unspoken American version of tolerance: Whatever.

The French call us les grands enfants, the big kids. In a country where you do whatever you want until somebody says you can’t (and then you will demand to do it as an expression of freedom), why shouldn’t a man suggest paying for breast implants by letting perverts watch the procedure? (“The perverts,” the staff member explains, “have to be medical personnel.”) Why shouldn’t a birth counselor overlook the father’s apparent confession of impregnating his daughter? You want “Jews will not replace us” squiggled on a cake, with a happy face underneath? No problem. Why shouldn’t the President’s personal lawyer claim on the record that the Chinese invented the virus and deliberately unleashed it on the world? Maybe. Might be something to that. I’m just saying. Check out the retweet.

The most redemptive moments come with Jeanise Jones. As Tutar’s babysitter she nudges the girl away from having breast implants and sets her on the way to thinking independently. Jeanise also teaches Borat that the pain he feels in his heart is love for Tutar. Another way this is a classical movie: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm has its own Magic Negro.

Narrative being narrative, the climax brings a change. Borat returns home, expecting execution, but he learns that his mission has actually been accomplished. His real purpose was to spread the coronavirus, developed in Kazakh labs to punish the world for laughing at the homeland after his first film. He has been the Typhoid Mary of the pandemic (his middle name is Margaret), and with his success Kazakhstan recovers a place of honor in the world community. It has moved forward to the digital age. Instead of playing ostrich, cut off from the outside world, the people are now staffing troll farms.

Now the daughters have joined globalization and have something important to do: overturn American democracy.

And instead of the Running of the Jew, the honorable tradition revealed in the first film, the homeland can afford to look down on a new scapegoat: America. In a colossal magnification of the grotesque, the ballcap hillbilly and the gun-toting Karen terminate Dr. Fauci.

Satire gone gross, pranks and punking pushed to randy delirium: No wonder Sacha Baron Cohen was so suitable for the role of the Yippie Abbie Hoffman in The Trial of the Chicago 7. In Borat Subsequent Moviefilm, I think he has done something important. He has made the 1960s put-on a vehicle of political criticism, by simply demonstrating how scary the pleasures of being stupid can be.

The movie cons its subjects, people say. No, they con themselves, aided by the Whatever principle. It’s not always very amusing, detractors say. Right. The grotesque never is. Being thoroughly stupid isn’t thoroughly fun. We are going to learn this over and over in the days and years ahead.

For enlightening commentary on Heartfield, visit here. On comix, the authoritative source is James P. Danky, Underground Classics: The Transformation of Comics into Comix (Abrams, 2009).

The standard survey of the grotesque is Wolfgang Kayser’s The Grotesque in Art and Literature. Jim Naremore makes the case for Stanley Kubrick as an artist of the grotesque in On Kubrick (British Film Institute, 2007). My quotation from Ruskin comes from p. 26 of that.

On the camera-ubiquity convention of pseudo-documentary, as it bears on The Office, you can see this entry. There’s also this one, on the Paranormal Activity series. The Kuleshov effect is discussed throughout our entries, especially here and in this video.

A noun, a verb, and . . . copping a feel in Borat Subsequent Moviefilm.

Vancouver envoi: What happens in movies happens between your ears

Summer 85 (2020).

DB here:

One of the nicest things anybody ever said to me came from Jacques Aumont, the distinguished French film scholar. He was visiting us in the early 1980s and I showed him a book manuscript I had just sent to the publisher. He read the first three chapters and said, “You remind us of something important. The spectator is thinking.” The book eventually came out as Narration in the Fiction Film.

In emphasizing that the spectator thinks, at least a little, I was driven to pay special attention to openings. The opening is where a film sets up information about its story world, about the action that will take place in it. We usually call this exposition. But a film also attunes us to the how as well as the what: how the story will be told. Exposition, in other words, includes introducing us to the characters and their situation but also to the ways we’ll learn about them. In the book I called the latter the “intrinsic norms” of narration.

But exposition isn’t simply a part of the plot, a chunk of opening material we need to digest. Exposition, the narrative theorist Meir Sternberg shows, is a process. In revealing what we call “backstory,” circumstances that predate the first scenes we see, exposition can go on throughout a film. (Kristin talks about this in her entry on Inception, and in revised form in our Nolan book.) So it turns out that the spectator has to keep thinking, keep reevaluating what’s being told about the story world and the way the story is told.

Three films showcased at the Vancouver International Film Festival set me thinking about these matters. Two depended on surprises, and these stemmed from the way exposition was handled. The third had very sparse exposition, asking us to gradually fill in story background through drifts and whiffs of information. In all cases, our enjoyment depends on thinking.

Surprise!

Bettina Oberli’s My Wonderful Wanda updates the ingredients of classic bourgeois comedy for the modern world of migratory caregivers. Josef and Elsa Wegmeister-Gloor oversee their pampered and confused son and daughter. Into the household comes a servant who is exploited for sexual favors by the old man. Wanda, the nurse brought in from Poland, is today’s equivalent of the chambermaid lusted after by both father and son.

As in most domestic comedies of class relations, Wanda the worker is no fool. Her duties help support her father, mother, and sons back home, and she proves herself a shrewd negotiator from the start. When Elsa asks her to perform extra chores, she demands more money. And when Elsa’s stroke-felled husband is willing to pay for sex, she agrees. Their secret bargain will, in good farce fashion, come to light in the most embarrassing way possible.

I went into the film knowing much less of the plot than I’ve just told you, so I want to keep back the rest. (Alas, the trailer overshares.) I was able to appreciate the way that Oberli’s tight script kept the surprises coming. Her script finds an admirable balance between clear structure and unpredictable turns.