The enemy next door

Thursday | August 8, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

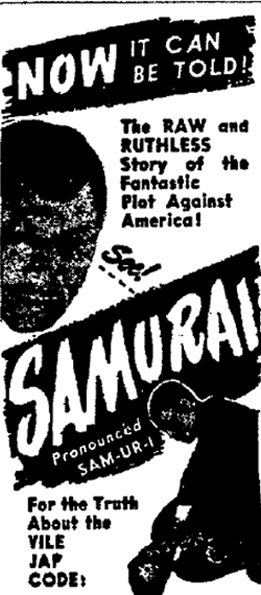

Left: Original caption: “Enforced farewell–These Japs wave farewell to relatives as they leave for Manzanar reception camp” (Los Angeles Times, 24 March 1942, p. B). Right: Advertisement for Samurai (Fitchburg [MA] Sentinel, 23 January 1946, p. 5).

DB here:

World War II never goes away, as the current attention given to Hollywood’s relation to Nazi Germany indicates. Thomas Doherty’s Hollywood and Hitler and Ben Urwand’s The Collaboration: Hollywood’s Pact with Hitler trace how the American studios responded to the rise of Nazism and the launching of hostilities. While working on 1940s Hollywood, I ran across two films that deal with another member of the Axis. They remind us of some painful incidents in our history, and they show how inflamed patriotism can burst into racial panic and oppressive public policy.

Call it a mass migration

Soon after Japan bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, there arose a fear that saboteurs were at work in America. No solid evidence of this was demonstrated, but the most powerful decision-makers were not in a mood to be tentative. In February 1942, President Roosevelt signed an executive order that authorized the Secretary of War and military commanders to demarcate areas from which anyone could be excluded. The Pacific coast was declared such a zone.

In early 1942, the US Army rounded up 110,000 California residents of Japanese ancestry and sent them to what were called concentration camps. (At that point the term simply meant a camp in which enemy populations were “concentrated.”) The evacuees were dispersed to makeshift camps throughout California, as well as in Wyoming, Arizona, Oregon, and Washington state.

Some of the internees were first-generation immigrants, but about 90,000, were citizens. A 1942 government documentary film presents the “relocation” process as necessary for national security, and it shows the evacuees accepting, in a spirit of patriotic submission, the need for such measures. In the film the evacuees effortlessly re-create their communities in their new locations.

Bizarre as it sounds today, the film takes pride in showing that a democracy can create humane concentration camps. But a reading of Richard Lingeman’s Don’t You Know There’s a War On? points up some things the film doesn’t say. The film doesn’t mention that the people rounded up were forced to abandon their homes, businesses, and farms and were permitted to take only what they could carry. (Newspapers often described the relocation as “voluntary.”) The film doesn’t show that the relocation centers were jerry-built, some by the inmates themselves, and were often located in harsh climates. The camp at Heart Mountain, Wyoming, was subject to sandstorms, blizzards, and subzero temperatures. Nor does the documentary note that the camps were enclosed in barbed wire and watched over by armed guards in security towers. Nor does the documentary show that, because Japanese-American farms produced 40 percent of the California vegetable crop, rival growers pressed for the internment and then snapped up the displaced farmers’ lands at what Lingeman calls “eviction–sale prices.”

The Japanese weren’t unique in undergoing internment; other ethnic groups were subject to investigation, confinement, and relocation. But no other minority was subjected to such a comprehensive roundup. It’s estimated, for example, that about 11,000 German-Americans, innocent or suspected, were interned–a significant violation of their rights, but nothing on the scale of Japanese internment. White people of European extraction, German-Americans had become pillars of American society, and were very numerous. (They were and remain the largest U. S. minority self-identified by descent.) Japanese-Americans, a much tinier and more vulnerable minority, were more easily marked as potentially alien to American values.

Late in 1942, the government began resettling Japanese-American internees outside the camps, spreading them to several states. In December of 1944, partly as a result of a Supreme Court decision the government could not consign “concededly loyal” citizens to camps, authorities declared that the west coast was no longer a war zone. But fears of Japanese espionage didn’t subside, as we can see from a 1945 independent film called Samurai.

Pledged to the God of War

Samurai shows an adopted Japanese boy growing into a traitor and spy. In September 1923, Mr. and Mrs. Morrey rescue Kenkichi from the ruins of the Tokyo earthquake and bring him home to San Francisco. While attending school and assimilating into American society, Kenkichi secretly visits a Buddhist temple where the priest inculcates him in the martial tradition of Bushido, the way of the samurai. Studying to be a doctor, Kenkichi becomes a proficient painter. At the same time, he swears to live and die by the sword, repeating the priest’s pledge that “The God of War presents the key to eternal life!”

The unsuspecting Morreys send Kenkichi to Italy and Germany for his studies, and the priest exhorts him make contacts that will train him as a secret agent. Back in America he begins painting abstract landscapes that conceal military information in coded form–a strange version of that motif of paintings and portraits that winds through 1940s American cinema (The Two Mrs. Carrolls, Suspicion, The Ministry of Fear). When the painting is abstract and nonrepresentational, it usually suggests that the painter may be mad.

Telling his parents that he will be a curator of Asian art, Ken goes to Tokyo and there, at the Black Dragon Society, he decodes his paintings. The Dragon Society’s leader suspects that his visitor is an American spy, but the doubts are dispelled when Kenkichi alters photos from Shanghai to appear that the Japanese are aiding the Chinese. Ken further proves his loyalty by murdering a journalist. He is assigned to the unit of General Sujiyama as a full-fledged spy.

Back at home, Kenkichi tells his priest of his mission, and shows what his reward will be: When the Japanese take over the west coast, he will become governor of California. Explosives are smuggled in, and Japanese farmers (“another link in the chain,” the voice-over narrator tells us) are coordinating domestic spies and saboteurs. The Morreys’ younger son Frank discovers Ken’s plot and tips off the police, while Kenkichi tries to convince the parents that he’s a double agent—before stabbing his father to death. Meanwhile, the invasion has been synchronized with the Pearl Harbor attack. At the climax, the temple priest realizes that his spy network has been arrested and his plan has failed. He commits ritual suicide, but Kenkichi, after brandishing the long samurai sword boldly, doesn’t follow the warrior’s way and instead flees to the beach. There he’s shot down by the police.

Premiered in New York in August 1945, after the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Samurai seems to have gotten a very limited release. It’s a cheap production, filled out with montages of newsreel footage, feeble special effects (the back-projection of the Kanto earthquake is especially jarring), and minimalist studio sets. Chinese actors, some with prior Hollywood experience, played the Japanese characters. The device of Kenkichi’s coded paintings seems to be borrowed from illustrative examples of espionage techniques filed as evidence in the 1942-1943 Dies Committee investigation. The We-want-your-white-women motif is made salient in a scene in which Ken and General Sujiyama disport with women captives. Ken toys with a blonde before tripping her.

During the same scene, a Chinese woman fights off the General’s advances before tearing up the Japanese flag. As was typical of the period, the Chinese were presented as courageous and defiant in the face of the Japanese invasion.

Samurai was planned in 1943 under the title “Confessions of a Japanese Spy,” an echo of Warners’ Confessions of a Nazi Spy of 1940. According to the AFI entry, another working title was Orders from Tokyo. Producer Ben Mindenburg supplied the story, and the director Raymond Cannon (who worked intermittently at Fox, Monogram, and elsewhere) is credited with the screenplay. Scenes suggesting rape of the General’s captive women displeased the Production Code Administration. The picture was awarded a PCA seal eventually, so perhaps some portions were omitted.

110,000 people inconvenienced

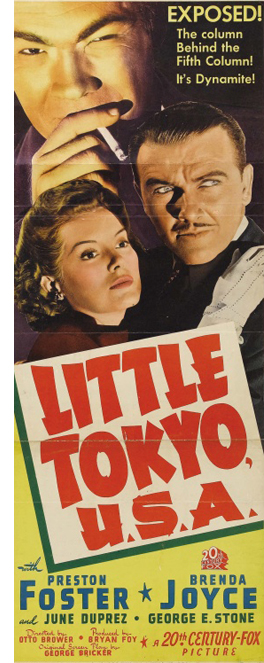

As a minor independent production with small circulation, Samurai can be dismissed as an outlier. It apparently wasn’t reviewed in Variety, but the New York Times called it “an example of opportunistic filmmaking . . . lurid and sensational. At this late hour, a motion picture should do something more than just shout, ‘The Japanese are brutal, scheming beasts.’” Yet three years before, in summer of 1942, Twentieth Century-Fox released a B-film that is hardly less virulent, and the Times, though finding it a “mediocre melodrama,” paid homage to its authenticity in pinpointing “details about incidents of espionage plotted in Los Angeles’s Japanese colony.”

Little Tokyo, U.S.A. (1942) centers on plainclothes detective Michael Steele, who suspects a Japanese family of receiving radio messages from Tokyo. After Steele’s friend Oshima agrees to check around, his corpse is found decapitated. Pursuing the case, Steele is brought up against a gang led by Takimura, an obsequious importer, and a German-American called Hendricks. As head of the local radio station, Hendricks allows the Japanese agents to use the transmitter to send messages to Tokyo. Hendricks also happens to be the boss of Steele’s girlfriend Mavis, a radio commentator.

Little Tokyo, U.S.A. (1942) centers on plainclothes detective Michael Steele, who suspects a Japanese family of receiving radio messages from Tokyo. After Steele’s friend Oshima agrees to check around, his corpse is found decapitated. Pursuing the case, Steele is brought up against a gang led by Takimura, an obsequious importer, and a German-American called Hendricks. As head of the local radio station, Hendricks allows the Japanese agents to use the transmitter to send messages to Tokyo. Hendricks also happens to be the boss of Steele’s girlfriend Mavis, a radio commentator.

Steele’s investigation is blocked when he can’t find the radio used by one of the gang to receive instructions from Tokyo. Takimura murders Teru, Hendricks’ Japanese mistress, and Steele is framed for the crime. Steele is in prison when Pearl Harbor is attacked. As “dangerous aliens” are rounded up, he escapes and finds Takimura’s hideout. Mavis, who has been skeptical of Steele’s suspicions, is taken captive by the gang. Takimura finds Steele hiding out in the city morgue. But when they confront Steele he springs a trap of his own: cops burst in and seize the conspirators. The film concludes with Mavis broadcasting the need to stay vigilant.

If Samurai crudely employs techniques of current semidocumentary (voice-over narrator, newsreel footage, some location shooting), Little Tokyo, USA remakes the G-man film into an affair of domestic espionage. We get the familiar frame-ups, the silhouettes and night streets, and the montages of headlines and police dispatches. Given how supple Fox’s B-pictures often were in the 1930s, with the Moto and Chan films and the Sherlock Holmes series, this is a very routine affair. The major Japanese villains are played by Caucasians in Yellowface; even the ubiquitous Abner Biberman (in the poster at right) is recruited to look Japanese.

Unlike Samurai, Little Tokyo, USA indicates that there are loyal Japanese-Americans like Steele’s friend Oshima. Nonetheless, the film buys wholly into the notion of a pervasive Japanese menace. A voice-over prologue presents this as a “film document,” and provides a montage of Japanese men photographing industrial and military sites much like those Kenkichi scouted in Samurai. More subtly, after Pearl Harbor, members of Takimura’s gang are shown putting up signs in their shops claiming to be patriotic citizens—something that many innocent Japanese-Americans did to forestall reprisals. Takimura even establishes a charity that purportedly finances the building of bomber planes.

Beyond spreading a general mistrust, the film aims to justify Japanese-American internment. To do this, it has to show that, as the prologue’s voice-over puts it, before Pearl Harbor Americans had been lulled into a false sense of security by “the mouthing of self-styled patriots.” So we meet several characters who exhibit fatal naivete. Early in the film, Mavis’ broadcast voices her hopes for peaceful negotiation with the Japanese. After Japanese-Americans protest Steele’s investigation, his superior claims:

The Japanese are peaceful, harmless, industrious citizens. They’re loyal too—most of ‘em. ‘Course there may be some rats in the bunch, but that’s nothing to get excited about. I was reading only this morning that 93 percent of the vegetable crop of California is in the control of the Japanese.

Steele replies:

Yeah, I know. They’ve got farms right next to all the airplane factories, and the dams, and the oil-storage concentrations.

He goes on to claim that the farmers lose money, but they’re subsidized by funding from a Tokyo bank.

On the other side, Takimura warns his gang that internment is what he fears most. “Mass evacuation will defeat our operation here.” Fortunately, he remarks confidently, evacuation will be blocked by Japanese civic groups and “certain sympathetic American interests.” This phrase casts anyone who might object as an unwitting tool of the Axis.

A new problem arises when the film must admit that not all 110,000 people of Japanese ancestry on the coast could be Fifth Columnists. So, like the government documentary, and like the LA Times news photo of grinning men bound for a resettlement camp, Little Tokyo, USA treats the innocent evacuees as accepting internment in a cheerful spirit. It’s proof of their patriotism and their contribution to the war effort. Here are the film’s final scenes, including some documentary footage of relocation and the empty streets of Little Tokyo.

At the denouement Steele punches Takimura (“That’s for Pearl Harbor, you slant-eyed–“) and Steele’s captain abandons his misplaced sympathy by clobbering the “squarehead” Hendricks. In the final scene, Mavis, her eyes now open, uses her broadcast to explain the need for some to sacrifice.

And so in the interests of national safety, all Japanese, whether citizens or not, are being evacuated from strategic military zones on the Pacific Coast. Unfortunately, in time of war the loyal must suffer inconvenience for the disloyal.

As happens today, those calling for sacrifice from others usually give up nothing themselves.

I offer no fancy analysis of these humdrum films. It simply seemed to me that, on the eve of the anniversary of the US bombing of Nagasaki, it would be worth remembering how quickly Americans in a state of war could find enemies among civilians overseas and in our cities here. Among us today there are many who would happily call for some American minority to be rounded up, locked up, sent away, put out of sight somehow. Look around you, as Resnais and Cayrol remind us in Night and Fog, and you will see the eager faces of future jailers.

Thanks to the staff of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium for permitting me to view Samurai. On the role of race in the Pacific War, see John Dower’s War without Mercy. The Dies Committee, later known as the House Un-American Activities Committee, produced a report on Japanese espionage that makes astonishing reading. Here is one passage:

California, with its mild climate and extraordinary agricultural resources, delighted the industrious Japanese. In fact, some of their vernacular newspapers went so far as to call California ”the New Japan.” They were not content to remain day laborers, as had the Chinese, but rapidly acquired their own land, or leased farm land which they frequently worked to depletion. Their women worked alongside the men in the fields for long hours, often with their babies strapped to their backs. Whole towns became Japanese, the native white population gradually leaving areas where the Japanese settled, since competition with them was so difficult if not impossible. They were assertive and aggressive, and did not achieve the reputation for honesty and faithfulness that was enjoyed by the Chinese. California fearfully envisioned the complete control of her agricultural land by the acquisitive Japanese, and became thoroughly aroused. Feeling ran high, but there was little of the violence against the Japanese which had unfortunately marked the agitation for exclusion of the Chinese.

The New York Times review of Samurai appeared on 24 August 1945, p. 7. Variety‘s review of Little Tokyo, U.S.A. appeared in the issue of 8 July 1942, p. 8, and the Times review was published on 7 August 1942, p. 13.

Interestingly, the documentary Japanese Relocation appropriates portions of Virgil Thomson’s scores for Pare Lorentz’s documentary The River (1938), and I think I heard a bit from The Plow That Broke the Plains (1936) as well. Presumably the government owned the rights.

Every day brings a fresh example of highly-placed and lunatic bigotry against immigrants to the US. Consider this. Or this.

The photograph below of a Nagasaki in 1946 is from the National Archives; I have taken it from the site About Japan. The quotation at bottom is from Life magazine, 20 August 1945, 27.

Seventy-five hours after the world’s first atomic bombing, an interval marked by President Truman’s demand for unconditional surrender, the second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, shipbuilding port and industrial center. This bomb was described as an “improved type,” easier to construct and productive of a greater blast. It landed in the middle of Nagasaki’s industries and disemboweled the crowded city. Unlike the Hiroshima bomb, it dug a huge crater, destroying a square mile–30% of the city.

When the bomb went off, a flier on another mission 250 miles away saw a huge ball of fiery yellow erupt. Others, nearer at hand, saw a big mushroom of smoke and dust billow darkly up to 20,000 feet and then the same detached floating head observed at Hiroshima. Twelve hours later Nagasaki was a mass of flame, palled by acrid smoke, its pyre still visible to pilots 200 miles away.

The bombers reported that black smoke had shot up like a tremendous, ugly waterspout. Physicists at the bomber base theorized that this smoke was the pulverized fragments of the Mitsubishi Steel and Arms Works. With grim satisfaction they declared that the “improved” second atomic bomb had already made the first one obsolete.