Archive for the 'Narrative strategies' Category

Lie to me: MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE

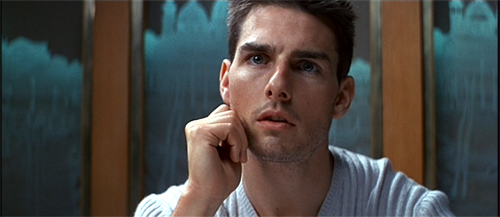

Mission: Impossible (1996).

DB here:

Filmmakers rightly consider themselves problem-solvers. They deal with budget limits, scheduling constraints, temperamental staff and casts, and balky equipment. Some problems come with financial demands; others are self-imposed, such as: “Tell a story confined to a single room.” The artistic problems often demand solutions that guide viewers toward clarity, comprehension, and emotional impact.

Suppose your story situation is this. Character A is telling a story, but it’s a lie. Character B realizes it’s a lie, but doesn’t signal that recognition. This is really two problems in one: How do you tell the audience A is lying? And how do you convey that B knows but doesn’t reveal that knowledge?

These are at the crux of in an intriguing sequence in Mission: Impossible. The solutions found by screenwriter David Koepp and director Brian DePalma show how even a straightforward “entertainment movie” can pose interesting questions about cinematic expression.

Spoilers ahead. But I bet you’ve seen this movie.

The problem(s)

The Impossible Mission team has been sent to Prague, purportedly to retrieve a digital disc listing all CIA agents in Europe. They don’t know that this assignment is a pretext for finding a mole, a rogue agent who is selling secrets to foreign interests. While infiltrating a state gala, most of the team is killed. Only Ethan Hunt, point man in the mission, and Claire Phelps, the wife of the team leader Jim Phelps, survive. The IMF chief Kittridge accuses Ethan of being the mole so Ethan, along with Claire, needs to flee. But out of devotion to duty he insists on finding the mole. He learns that the mole under the alias of Job has offered to sell the NOC list to Max, a dealer in covert information. The bulk of the plot revolves around Ethan’s efforts to induce Max to reveal Job, which Ethan can do only by offering Max the NOC list—while at the same time making sure that it doesn’t really fall into Max’s hands.

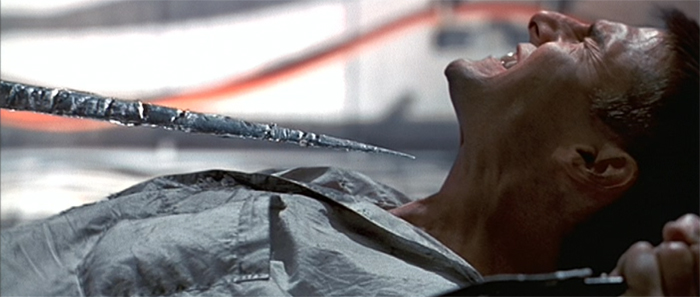

After a prologue, which I discussed in an earlier entry, the film’s first stretch revolves around the team’s invasion of the embassy party. As the scheme collapses, we see the deaths of the team members. Through cross-cutting and a moving-spotlight narration, the film shows us the technician Jack killed in an elevator shaft, Jim Phelps shot on a bridge and tumbling into the river, Sarah stabbed at a gate, and Hannah killed by a car bomb. The effects of these killings are registered largely through Ethan’s response. He hears Jack lose contact, watches video transmission of Jim’s bloody hands, finds Sarah impaled by a knife, and sees Hannah’s car explode. Later he, and we, will learn that Claire escaped.

At the start of the film’s climax, Ethan discovers that Jim Phelps is still alive. In a café, Jim explains that he survived the shooting and that he saw the killer: Kittridge. Kittridge is the mole, he claims. Jack brings Jim into his plan to meet Max on the Eurostar train and apparently give her the NOC list he’s stolen from Langley.

The twist is that Jim–Ethan’s mentor, friend, and surrogate father–is lying. He is Job the mole, and he has eliminated his own team, faking the attack on himself. Thanks to crosscutting, the first version of the attacks concealed from us the actions Jim takes to kill his colleagues. The narrative problems are: How and when to tell us of Jim’s treachery? And how to represent Ethan’s state of awareness? Is he misled by Jim’s account, or does he doubt it? And what is Claire’s role in all this?

Three solutions

Singin’ in the Rain (1952).

Every creative choice eliminates alternatives, and I’ve compared classical filmmaking to selecting from a menu of more or less favored options. That menu can offer filmmakers ways of solving narrative problems. One choice for the M:I revelation is simply to present Jim telling Ethan his lies in the café. Ethan then can react in horror, leaving us to assume that he doesn’t doubt him.

This option was actually tried out in an early script draft. Jim explains and Ethan, despite some hesitation (“Hold on, it’s taking me a minute to adjust here“), seems to accept his story. Only in their final confrontation on the Eurostar does Ethan reveal that he had long before figured out that Jim had betrayed the team. We had no inkling that in the café Ethan was merely pretending to accept Jim’s account. His awareness of Jim’s scheme was held back as a surprise.

Another narrative option appears in a later script draft. This time Jim’s explanation is accompanied by flashbacks illustrating his lies. He claims to have swum to shore, patched up his gunshot wound, and followed Ethan’s trail. He then tells Ethan it was Kittridge who shot him and killed Sarah, and these moments are illustrated with quick flashback imagery. These are lying flashbacks. As a neat fillip, two of these shots replay Ethan finding Sarah’s body nearby, as if to certify Jim’s story. “Ethan just stares at Phelps, his eyes wide with surprise.” Again, we’re led to think that Ethan trusts Jim’s tale, making the train confrontation a revelation of Ethan’s outplaying Jim.

We should remember that the Hollywood menu provides the lying flashback as an option, albeit rare. In Singin’ in the Rain, for instance, Don Lockwood’s voice-over interview portrays his early career as one of refined show-business accomplishment. “Dignity—always dignity.” But the images undercut this by showing him performing slapstick routines in burlesque. Since this is a comedy, we can understand that the film’s flashbacks are debunking his pretension. As for the second problem, that of conveying a listener’s skepticism, the present-time scenes reinforce the impression of Don’s puffery by showing his pal Cosmo’s eye-rolling reaction. Still, the interviewer and presumably the radio audience are taken in.

This second M:I script variant doesn’t include such hints that Ethan doubts Jim, so the problem of the conveying the listener’s true reaction is bypassed. But the final film supplies yet another solution.

After I drafted what you’ve just read, I heard from screenwriter David Koepp. I had written him to ask about the alterations, and he talked with De Palma about them.

Brian reminded me that the intention of the scene was built around an idea — can we show Jim lying, and simultaneously see Ethan figuring out those lies in his own mind? Without telling Jim that he knows it’s a lie, Ethan is picturing for us what the truth must (or might) have been. It’s a cool idea, and, typical of DePalma, highly visual. Actually seeing on screen versions of events that may or MAY NOT have happened is something we started playing around with in M:I, and then did to a greater degree in Snake Eyes, which we wrote right after that.

Neither one of us can remember in useful detail about why we might have tried several other versions first, but my guess is that the one with Jim simply verbalizing the lie was jettisoned in favor of images for obvious (and again, DePalma-esque) reasons, i.e., it’s better to see something than to hear it. The flashback showing Kittridge as the perpetrator was likely because we wanted to keep going for as long as possible with the character I’ve come to call the Principled Antagonist — POSSIBLY a villain, turns out not to be, but always diametrically opposed to the hero and his goals.

It was good to have my hunch confirmed, and to watch filmmakers sampling the menu of options from draft to draft. The final shooting script presents the new variant. Ethan, not Jim, spells out the scheme in dialogue. This leads Jim to assume that Ethan accepts Kittridge as the culprit. But the image track shows Jim committing the crimes. As the script puts it:

A reprise of PHELPS’s narrative only now ETHAN’S telling it and camera is showing the events as ETHAN sees they actually happened.

There’s still a potential obstacle, though. What if the viewer takes the flashbacks to show what really happened but doesn’t grasp that they’re Ethan’s imaginings? They might be only “the film telling us what really happened,” as in Singin’ in the Rain. How to establish that we’re following Ethan’s train of thought while he lies during his dialogue with Jim?

How to lie to a liar

Here’s the sequence as it appears in the film.

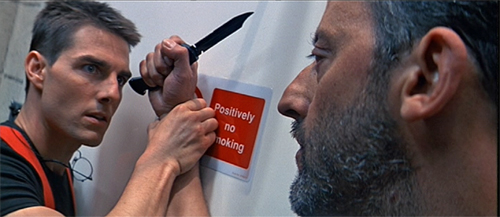

On the first problem, the sequence makes clear that Jim’s accusation of Kittridge is false. We’re introduced to Jim’s treachery with several shots showing Jim engineering Jack’s death in the elevator. Several more shots, stressed through slow-motion, illustrate how Jim faked his own death. And the knifing of Golitsyn and Sarah is attributed to Krieger. You can also argue that wily viewers will take Jim’s sidelong glance at Ethan as a tip-off to his treachery–a classic shot lingering on the Guilty One (as we’ve seen elsewhere).

Still, how can we be sure that Ethan sees “events as they actually happened”–especially since his shock and puzzlement at hearing Jim’s tale seem so genuine?

The sequence solves the second problem with two passages that strongly imply that the flow of images reflects what’s in Ethan’s mind.

First, among phases of the stabbings at the gate, there’s the interpolated shot of Ethan pinning Krieger’s wrist to the wall during the Langley heist.

The two-shot of Ethan and Krieger, a flashback not part of Jim’s story, indicates Ethan’s realization that the knife he found in Sarah’s side was one of Krieger’s. Interestingly, this shot isn’t in the shooting script.

A stronger cue that we’re in Ethan’s mind comes with the “revised and corrected” version of Hannah’s death. Did “backup” take her out? The answer comes with a shot of Claire triggering the explosion and turning to look at the camera.

Claire’s look defies plausibility. It’s as if she is turning to glare, almost defiantly, at the Ethan who’s imagining this. Because he’s attracted to Claire, he wants to give her the benefit of the doubt. His imagination immediately proposes an alternative in which Jim sets off the bomb.

In the train at the climax, Jim will confirm Ethan’s hesitation: he was reluctant to suspect Claire. In the later stretch of the café scene, not included in my extract, the question of her loyalty is evoked as Jim urges Ethan to keep quiet about the scheme. When Ethan returns to Claire at the safe house, there remains the issue of whether her seduction of him is sincere or a further act of betrayal.

More immediately, the two problems are solved. Not only do we have the exposure of Jim’s lie, but we also get glimpses of how Ethan reconstructs what really happened. What makes this all particularly clever is that Ethan’s dialogue seems to confirm Jim’s tale. Ethan’s verbal duplicity is consistent with his talent for bluffing (as with Krieger and the fake NOC disc) and the earlier twinge of suspicion he had about Jim’s Palmer House Bible. When image and sound contradict one another here, we’re obliged to trust the image.

All of which charges Ethan’s final question–“Why, Jim? Why?”–with a double significance. Apparently asking about Kittridge’s motive, Ethan is pressing his mentor, almost desperately. Jim’s answer, about a refusal to accept the end of the Cold War, applies as much to him as to a CIA bureaucrat. We may not fully recognize it at the moment, but Ethan’s question marks the end of their friendship.

Someone might ask if every audience member will realize that the sequence solves both problems. Presumably even a ninny understands that Jim is lying; but maybe some viewers don’t get that Ethan is aware of the lie. My own inclination is to see the cues of Krieger’s knife and the revised version of Hannah’s death as pretty solid hints. Still, we might be in the realm, not unknown to Hollywood cinema, of a film that includes subtleties that not every viewer catches. I’m reminded of a screenwriter’s remark: “It’s not necessary that every viewer understand everything, only that everything can be understood.” This is presumably one reason we return to films and find more in them.

It’s also one reason it’s fun to analyze them.

Thanks to David Koepp and Brian De Palma for responding to my questions. David’s script archive is here.

The remark about understandable stories comes from Ted Elliott, as quoted in Jeff Goldsmith, “The Craft of Writing the Tentpole Movie,” Creative Screenwriting 11, no. 3 (May/ June 2004):, 53.

Mission: Impossible (1996).

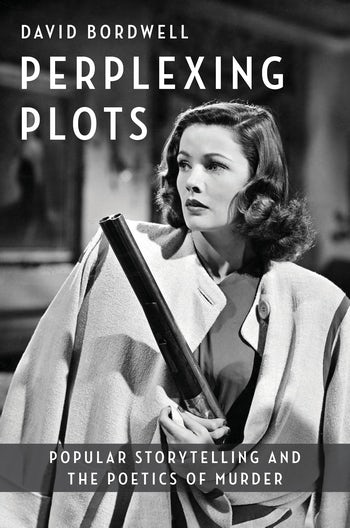

PERPLEXING PLOTS: On the horizon

DB here:

In the Before Times, I didn’t watch much fictional TV. Our modest monitor was chiefly a delivery device for news, DVDs, and Turner Classic Movies. We followed The Simpsons, and I came to like Deadwood and Justified, but usually the time commitment demanded by long-form series put me off. I gave my curmudgeonly reasons long ago on a blog entry.

But over the last nine months, forced to stay home, I dipped my toe in the water. Streaming made it easy to catch up with shows I’d never seen and offered a plethora, or rather a glut, of original series. This still-limited experience of long-form shows confirms the presence, if not the dominance, of what Jason Mittell in his excellent book calls Complex TV.

Many shows mix timelines with abandon. Both the documentary WeWork; or, The Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn (2021) and the docudrama WeCrashed (2022) open near the end of the story action and then flash back to show what led up to it. (This crisis structure became especially common in 1940s Hollywood.) Billions, an older series I’d never followed, contains an episode (Season 2, 2016) that jumps to and fro among a funeral, scenes taking place before it, and scenes afterward, several attached to different characters. In the Hulu series Dopesick (2021) a sliding timeline graphic shifts among many periods and character viewpoints; to keep track of it all you’d need to make a spreadsheet. (It would amount to something like the whiteboard used in writers’ conference rooms to map out the unfolding series.) I can’t recall all the shows that friends have recommended as examples of daring play with narrative.

Of course all this isn’t news. For years both indie films and Hollywood blockbusters have offered complicated segmentations, broken timelines, and splintered viewpoints, with contradictory replays and unreliable narration. Still, it was good to be reminded that the problem I’m tackling in my latest book is still current—indeed, dominant. We may have to wait for the new Justified series to see a return to straightforward linear storytelling.

When and how did viewers develop the skills that lets them appreciate the New Narrative Complexity? This is at the center of Perplexing Plots: Popular Narrative and the Poetics of Murder.

Maybe we were always smart

Intolerance (1916).

There’s a view, most eloquently posed by Steven Johnson in Everything Bad Is Good for You, that these comprehension skills are a fairly recent development. They stem from rising IQ levels, growing facility with video games, and other cultural phenomena after the 1970s. People are now smarter consumers of narrative than they were in the days of I Love Lucy.

I argue instead that popular narrative has been cultivating these skills across a much longer period, and they firmly took hold in mass culture at the start of the twentieth century. You can get a summary of my argument here on the Columbia University Press site.

Most broadly, a lot of (now-forgotten) mainstream plays and novels were as experimental in shifting point-of-view and juggling time frames as any we find today. For example, we celebrate backwards stories as typical of the demands of modern storytelling. The play and film Betrayal and the films Memento and Shimmer Lake are among many recent media products presenting the scenes in 3-2-1 order. But this possibility was discussed by a prominent critic in 1914, and soon a major woman actor wrote a play that used reverse chronology. There followed other examples, not least W. R. Burnett’s novel Goodbye to the Past (1934) and the Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (1934).

Some will argue that innovations of popular narrative are dumbed-down borrowings from modernist or avant-garde trends. I try to show this process as a two-way dynamic: modernism borrowing from popular forms, mainstream storytellers making modernist techniques more accessible. But we also find that popular storytelling has its own intrinsic sources of innovation, as with the reverse-chronology tale and Griffith’s application of crosscutting to different time frames in Intolerance (1916).

So it seems to me that audiences have long been capable of tracking the sort of fancy narrative devices we find now. They encountered them in many types of stories, and I devote the first part of Perplexing Plots to a quick survey of developments in novels and plays. (Yes, Stephen Sondheim is involved.) Audiences have learned to enjoy self-conscious artistry, an awareness of form and technique–what one disapproving reviewer of Wilkie Collins called “the taste of the construction.”

Such a taste was cultivated in depth in one mega-genre. That was a major training ground for giving us the skills to follow complex, sometimes deceptive storytelling.

Mystery on my mind

Pulp Fiction (1994).

Ever since my teenage years I’ve been a fan of mysteries on the page and on the screen. I’ve smuggled discussions of detective stories and crime thrillers into many of my books, and my last one, on 1940s Hollywood, did a lot with this form of storytelling–largely because it was so central to the films of that era.

Perplexing Plots in a way turns Reinventing Hollywood inside out. The earlier book put movies at the center while showing how filmmakers borrowed from mysteries in other media. The new one puts fiction, theatre, radio, and even comic books at the center, discussing how mystery conventions developed–and showed up in films as well. The two books complement each other, I guess, although the historical sweep of the new one runs from the 1910s to the present.

Mystery was essential to many classic novels, from Wuthering Heights to the tales of Henry James and Joseph Conrad. Dickens and Wilkie Collins made mystery a major attraction of “sensation fiction.” In the twentieth century, the Anglo-American whodunit, the suspense thriller, and the hardboiled detective tale–to take the three most well-known genres–trained audiences in appreciation of nonlinear plotting, misleading narration, and subterfuges of concealment.

A Western or a science-fiction tale may include a mystery, but it doesn’t have to. In mystery fiction, the suppression and misinterpretation of information is foundational to the genre itself. A mystery depends on a “hidden story,” which will often be revealed out of chronological order and refracted through the minds of several characters. At a meta-level, the genre cultivates a gamelike approach, where we expect the author to give with one hand and take away with the other. Across history, a mass audience became sophisticated consumers of complex narratives.

I trace how this happened with Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, Marie Belloc Lowndes, E. C. Bentley, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Daphne du Maurier, Cornell Woolrich, and many other authors. I spend a lot of time analyzing both plot structure and the texture of the writing. If nothing else, I hope to show that this genre encourages not only great ingenuity in plotting but also subterfuges of style.

I trace this process into the 1940s, when in my view the basics of contemporary techniques crystallized and become widespread. The book then looks at some case studies of how crime novels and films have explored the various possibilities of broken timelines, disparate viewpoints, and misleading narration. I devote chapters to Erle Stanley Gardner, Rex Stout, Patricia Highsmith, Ed McBain, Donald Westlake, Quentin Tarantino, and Gillian Flynn.

I could have gone much farther. Every reader will have a long list of authors I’ve omitted. But I had to stop somewhere! And I decided to concentrate on some of my favorites. The result is, if nothing else, appreciations of the verbal artistry of some underestimated storytellers.

This isn’t to say that audiences of 1920 could have easily followed Inception (2010) or Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022). Storytellers have pushed forward, revising schemas that are widely known and teaching us to recognize the tweaks they’ve introduced. Audiences have accumulated a repertory of skills, built upon their experiences of other formal experiments. Those experiences, I want to show, have been crucially shaped by the conventions of mystery narratives.

Looking back on other things I’ve written, I find that I’m repeatedly concerned with finding beauty in popular genres and modes of storytelling. My studies of Hollywood, Hong Kong cinema, Japanese films, and other forms of cinema have taught me that mass entertainment harbors not only pleasures but also precise craft and daring artistry. While I’ll never give up my love of disruptive and “difficult” work, I find that films appealing to wide audiences, from His Girl Friday and Meet Me in St. Louis to the masterworks of Ozu and Hitchcock and Lang, have a unique power. Fortunately, we don’t have to choose.We can have them all. Perplexing Plots is my effort to show that storytelling craft in its humblest forms can yield its own rapture.

Advance appraisals of the book can be found here. (Click on “Reviews.”) It’s due to be published in January 2023. In the months ahead, from time to time I hope to blog more about the ideas in the book. In the meantime, I wait for the new installment of Slow Horses.

There are too many people to thank here; my debts are recorded in the book’s Acknowledgments. But at least I want to thank John Belton for supporting the project, and Philip Leventhal and Monique Briones at Columbia University Press for their swift and efficient work on the manuscript. And love to Kristin, who took care of me while I finished the book and recuperated from surgery.

The Lady Vanishes (1938).

Crime in the streets and on the page

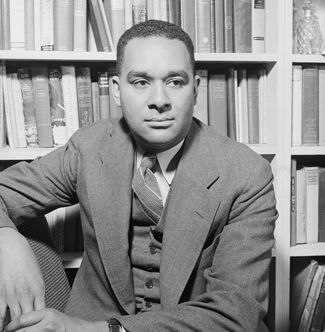

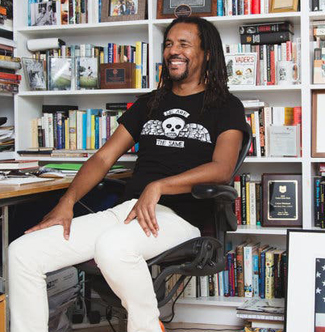

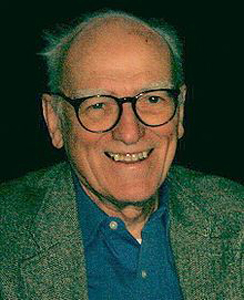

Richard Wright (Britannica.com); Colson Whitehead (New York Times).

DB here:

In the 1940s, Richard Wright was one of America’s most distinguished writers. His shocking novel Native Son (1940), in which a young Black man kills and decapitates a white woman, became a best-seller. After Citizen Kane, Orson Welles mounted a flamboyant Broadway version. Wright’s memoir Black Boy (1945) was a milestone in depicting the experience of a modern African American migrating from the South to Chicago. Yet a book Wright wrote between these two failed to find a publisher and has only recently been revealed.

The Man Who Lived Underground was inspired by a report about a Los Angeles burglar who launched his missions from a bunker in the sewer system. In Wright’s book, this Underground Man is Fred Daniels, a Black laborer who’s been arrested for a murder he didn’t commit. The police torture Fred into making a confession. But when Fred is allowed to accompany his pregnant wife to the hospital, he escapes into the sewers.

There follows an extraordinary adventure in exploring city life literally from below. Fred builds himself a sanctuary and begins to survey, in a cross-sectional panopticon, the lower depths of churches, movie theatres, markets, furnace rooms, and office buildings. As he grows more confident, he pillages food, furniture, and money, decorating his man-cave with dollar bills and jewels. But he also has an urge to return to the world above, if only to show what a free Black man can do.

There follows an extraordinary adventure in exploring city life literally from below. Fred builds himself a sanctuary and begins to survey, in a cross-sectional panopticon, the lower depths of churches, movie theatres, markets, furnace rooms, and office buildings. As he grows more confident, he pillages food, furniture, and money, decorating his man-cave with dollar bills and jewels. But he also has an urge to return to the world above, if only to show what a free Black man can do.

Why Wright’s manuscript was rejected is unclear. His agent and his customary publisher Harper left notes suggesting that the more symbolic, hallucinatory dimensions of the book didn’t blend with its social realism. One reader thought that the portrayal of Fred’s beating by the police was “unbearable.” That might refer to the harsh violence of the scenes, but also because Wright shows something seldom acknowledged, then or now: the routine, sadistic police brutality directed at Black citizens.

In any event, Wright set the book aside, but he did turn it into a 1944 short story of the same title. The Man Who Lived Underground was finally published this last spring by the Library of America, with very good contextualizing essays and Wright’s stimulating and wide-ranging “Memories of My Grandmother,” in which he traces the personal influences on the book.

He doesn’t dwell on one of the most obvious ingredients, probably because it was so pervasive in 1940s media: the power of a crime plot. Native Son had centered on a homicide, rendered from the killer’s viewpoint. This novel does the same with robbery, sinking us thoroughly into Fred’s mind and registering everything that happens in personal, sensuous detail. The cops of the opening come out of hard-boiled tradition, and Fred becomes another of all those wrong men fleeing the police in film and fiction. Hitchcock might well have agreed with a point Wright makes in his memoir: “I believe that the man who has been accused of a crime he has not committed is the very person who cannot adequately defend himself.”

I don’t want to trivialize a powerful book by saying it’s “just a thriller.” For one thing, Wright shows that thriller premises can be valid vehicles for social critique. But just as important, a crime plot can draw readers to engage more deeply with the action. If the book lacked the pressure of the police pursuit, and simply showed Fred as a vagrant touring the underground life of LA, it would be more episodic and diffuse. When Fred evades the police or embarks on his raids on the subterranean city, there’s a level of suspense that is of value in its own right.

Tempted by mystery

Over the last few years, I’ve been writing a book about how popular storytelling techniques in twentieth-century media have shown their experimental side. I try to trace how nonlinear time schemes, complexities of viewpoint, and unconventional strategies of segmentation have come to create what some have called the “New Narrative Complexity.” These maneuvers, it’s claimed, now attract audiences in themselves: “Form is the new content.”

I’ll try to show that this trend, however striking it seems to us, has important precedents. Since the end of the nineteenth century Anglo-American prose fiction, theatre, and film have at all levels of taste, tried out innovative methods. Audiences mastered them and some demanded more, so the pressure of competition led storytellers to try to surpass themselves and their peers. This process, I suggest, is vividly seen in the way in which mystery plots characteristic of detective stories, suspense tales, and kindred genres were escalated, mixed, and varied across the decades.

In addition, the conventions of mystery have long been incorporated into “serious” or prestigious western literature as well. Crime and its investigation have sustained plots from from Oedipus to Dostoevsky and Dickens and Henry James. Modernists haven’t resisted either. Not only did Faulkner write bona fide detective stories, most famously Intruder in the Dust (1948), but his more canonical novels depend on laying bare, through a process of investigation, family secrets. Mystery, and the puzzles and suspense it generates, pervades storytelling both High and Low and in-between.

Wright, composing his books in the Murder Culture of the 1940s, is a good example. But so too is another novel published this year, Colson Whitehead’s Harlem Shuffle.

A rising entrepreneur

Ray Carney owns a furniture store in Harlem, selling both new and used items on the installment plan. Most of his inventory is legitimate, and he prides himself on helping struggling families afford nice things. He lives comfortably with his wife Elizabeth, who’s expecting their second child. The book traces three phases of Ray’s life in tagged blocks: 1959, 1961, 1964.

Ray is part of a social milieu richly evoked by Whitehead’s exposition of the neighborhood and its politics. Period details, shop-window displays, and dynamics in the local Black hierarchy are gracefully integrated. Elizabeth’s well-off parents live on Strivers’ Row and her father looks down on Ray as a “rug merchant.” Backstory about people and places is sometimes supplied by wide-ranging external narration, but most of the descriptions are filtered through Ray’s perception. The splendor of the Theresa Hotel, the “Waldorf of Harlem,” is summoned up in his childhood memories of the spectacle of guests and performers parading in, cheered by adoring crowds.

Ray is part of a social milieu richly evoked by Whitehead’s exposition of the neighborhood and its politics. Period details, shop-window displays, and dynamics in the local Black hierarchy are gracefully integrated. Elizabeth’s well-off parents live on Strivers’ Row and her father looks down on Ray as a “rug merchant.” Backstory about people and places is sometimes supplied by wide-ranging external narration, but most of the descriptions are filtered through Ray’s perception. The splendor of the Theresa Hotel, the “Waldorf of Harlem,” is summoned up in his childhood memories of the spectacle of guests and performers parading in, cheered by adoring crowds.

From the start, we’re introduced to this social texture through a day in Ray’s life. The second sentence of the opening is:

Ray Carney was having one of his run-around days–uptown, downtown, zipping across the city. Keeping the machine humming. First up was Radio Row. . . .

At Radio Row, Ray brings some damaged radios to electronics dealer Mr. Aronowitz. There he buys TVs that supposedly “fell off the truck.” This establishes the blurred boundaries of Ray’s business, which includes a gray-market side hustle. The very full description of Aronowitz’s shop and his relation to Ray is typical of the book’s texture.

Next Ray visits a high-school friend who’s selling her sofa and chair before moving to DC. This chapter allows Whitehead to fill in Ray’s younger days and include a scene in which he reveals a surprising capacity for violence. Then Ray drives to his shop, where we’re introduced to his salesman Rusty, and the day proceeds. It’s important to establish Ray’s routines of pickup, delivery, and selling because very soon they will be disrupted.

Ray is more than a register of his surroundings; he’s an active protagonist. He is mildly driven to rise in the world. He vows to move his family to Riverside Drive “one day, when he had the money.” But he won’t turn ruthless. He’s convinced himself that he is a decent person, helping his customers, supporting his family, aiding his feckless cousin Freddie when he can. “I may be broke, but I ain’t crooked.” When he occasionally takes some sketchy merchandise or fences a few pieces of jewelry Freddie has stolen, he calls himself merely “a middleman.”

By now the reader suspects that this is a story about a decent man’s slide into high-risk compromise. The book’s first part bears the ominous epigraph: “”Carney was only slightly bent when it came to being crooked . . .” Only slightly bent may be bent too much.

Not a spoiler, a teaser

What I haven’t told you is that each of the book’s three parts depends on a plot schema derived from the mystery tradition. Part One centers on a heist, a bold jewel robbery of the landmark Hotel Theresa (above). The second part is a story of political bribery and the revenge taken for a double cross, in the vein of Hammett’s Glass Key. Part three starts with a robbery but becomes a man-on-the run plot. These conventional action arcs give propulsion to the social and psychological dimensions of Ray’s activities.

Whitehead acknowledges the influence of the crime tale. According to a profile in the Times:

Whitehead steeped himself in novels by Chester Himes, Patricia Highsmith and Richard Stark, one of Donald Westlake’s pen names.

These three writers neatly parallel the book’s three parts: Stark for the heist, Himes for the Harlem backroom intrigue, and Highsmith for the suspense-driven finale. Whitehead’s editor notices the blend and sees the genre dimension as a vehicle for the book’s themes:

“What Colson does with the heist genre, he hits all the marks, the dialogue is fabulous, but as you get further into the story, you begin to realize the depths of what he’s up to,” said Bill Thomas, editor in chief and publisher of Doubleday. “You begin to see he’s using the tropes of the crime genre to tell a much larger and deeper story.”

It works the other way too. Without these “tropes,” readers would be less gripped by the social critique. (By the way, I’d argue that a lot of genre fiction does “tell a much larger and deeper story,” while also offering other pleasures.)

Whitehead smoothly integrates the crime elements with the tradition of the twentieth-century American social-psychological novel (Wharton, Fitzgerald, O’Hara, et al. up to Bellow and Updike). He pulls a bait-and-switch in the very opening. I reported the opening’s second sentence, but I left off the very first one.

His cousin Freddie brought him on the heist one hot night in early June. Ray Carney was having one of his run-around days–uptown, downtown zipping across the city. Keeping the machine humming.

We won’t hear of the heist again for another twenty pages, but that first sentence is enough to prime us to keep going.

We’re eased into the crime plot by another addition to Ray’s itinerary on that first day, a visit to the somewhat shady bar Nightbirds, which is revealed as part of his common routine. Soon enough Freddie is pitching his plan, and the book moves into the canonical heist pattern I’ve discussed before.

The bulk of the first part’s action takes place in the aftermath phase of the heist, a common option. Like classic caper stories, Harlem Shuffle plays with time and viewpoint, shifting to a flashback that renders Freddie’s experience during the robbery–all of which enhance the classic effects of suspense and surprise. Back in the present, the tension rises. Ray gets a visit from a rival gang, rendered in pure hardboiled prose, filtered through Ray’s panic.

He’d have to satisfy himself with making it through the meeting in one piece.

The safecracker dismissed the class.”We keep our mouths shut,” Arthur said, “see how it shakes out. Then divvy it up like we planned. ” Miami Joe never closed a job unless he was satisfied they were free and clear.

The meeting ends with Ray facing a deadline: “Four days for Carney to come up with an angle.”

I’ve gone a little too far into the action, maybe, but please consider this as parallel to the way Whitehead treats his first sentence. I’ve offered not so much a spoiler as a tease. I can’t see any other way to show how elegantly the book absorbs genre conventions while aiming at a broader analysis of Harlem life and Ray’s character.

Thick local history

Barber shop; The Undefeated.

Since I’m interested in style, I was struck by several strategies that Whitehead uses to pursue the “larger and deeper strategies” that “purer” crime fiction seldom attempts. One strategy is more elaborate description, often thickened through adding a historical dimension.

Contrast Chester Himes’ wild tale of a single night of cascading crime, A Rage in Harlem (1957), set roughly in the middle of the three eras Whitehead presents. Himes’  book is driven by spurts of dialogue and frantic pursuits, captures, escapes, fights with fists and knives and pistols. The plot is kicked off by a preposterous machine that can transform ten-dollar bills into hundreds, and it ends with a hearse tearing through night streets bearing (supposedly) a trunk full of gold. Before things go spinning out of control, however, the hapless protagonist Jackson calls on his brother Goldy, whose scam is to dress up like a nun and beg in front of the Teresa Hotel. A chapter starts:

book is driven by spurts of dialogue and frantic pursuits, captures, escapes, fights with fists and knives and pistols. The plot is kicked off by a preposterous machine that can transform ten-dollar bills into hundreds, and it ends with a hearse tearing through night streets bearing (supposedly) a trunk full of gold. Before things go spinning out of control, however, the hapless protagonist Jackson calls on his brother Goldy, whose scam is to dress up like a nun and beg in front of the Teresa Hotel. A chapter starts:

The plate-glass front of Blumstein’s Department Store, exhibiting eye-catching items of wearing apparel and house furnishings for the residents of Harlem, extended from the back of the Hotel a half block down 125th Street.

A Sister of Mercy sat on a campstool to one side of the entrance, shaking a round black collection-box at the passersby and smiling sadly.

So much for the milieu. Before Elmore Leonard explained, “I tend to leave out the parts that readers tend to skip,” Himes was practicing a minimal functional description of the wares in Blumstein’s window. Now here is Whitehead on another shop display:

Sterling Gold & Gem was a venerable jewelry store on Amsterdam, ten blocks up. The dusty orange bulbs in the sign out front blinked on and off to simulate movement, like a greyhound dashing around a track. Young lovers knew the engagement rings and wedding bands out front, while the drawers of uncut stones and hot merch in the back catered to a more disreputable clientele. Given his insulting rates, the owner, Abe Evans, was a fence and Shylock of last resort. . . .

…and so on, with several more sentences about Evans’ business conduct, eventually bringing us back to Carney’s mind with a button: “Fancy that.”

Whitehead gives us a sharp picture of the display as a visual attraction, complete with a simile, followed by an account of innocent lovers, before taking us back to the dirty part of the business. He provides a glimpse of the “deep history” of the store, while Himes is minimally concerned to anchor his new scene geographically.

The contrast isn’t simple. Whitehead needs to establish Abe on his entrance into Carney’s situation, as Himes needed to set up Goldy–which Himes soon does through backstory after the passage I quoted. To supply a more dense backstory to the window display would slow up Himes’ grim comic extravaganza as it’s building steam. And Whitehead isn’t above using a classic scenic hook, a mention of Sterling Gold & Gem, in the paragraph just before, which smoothly justifies filling in Evans’ backstory. I just want to suggest that Whitehead’s back-and-fill description, showing that patterns of social behavior pervade even consumer goods, is typical of a register of writing that tries to steep plot action in cultural implication.

If Himes asks us to tease significance out of howlingly outrageous situations, Whitehead points us toward innocuous items as a cluster of signs that need deciphering. It’s an effort to saturate every moment with implicit meanings that merge with the broader themes of the book. This story of the gnawing corruption of an ordinary man depends on the same disparity: the innocent hearts of young lovers and the man who uses them as pretexts for more or less petty crimes.

Thick description, laced with metaphor, is only one strategy for “lifting” crime schemes to the level of “serious writing.” Chandler got credit for the same thing, as does John le Carré now. Wright employs the same technique in The Man Who Lived Underground.

Style of this sort is exactly what the mainstream prestige novel has promoted for over a century, but it needn’t supply our only criteria for exciting narrative. The virtues of the Himes approach are can be found in Hammett, particularly in the Continental Op stories. Minimalism has its own power, in speed, force, and the creation of a pulsating rhythm.

There are dimensions to The Man Who Lived Underground, A Rage in Harlem, and Harlem Shuffle that experts in African American literature could detect and that I can’t. Of course those dimensions should be explored; we should strive to know artworks as intimately as possible. To that end, I’m interested in how formal and stylistic techniques available to many storytellers of different sorts can be mobilized to engage audiences–and to straddle the boundary between “high art” and “mass art.”

More specifically, my book is an effort to show the formal and stylistic achievements of a genre that in its most intriguing experiments modifies or challenges canons of Serious Literature. A robust storytelling tradition forges its own tradition of craftsmanship, and that tradition is open to borrowing from anyone. Of course we cinephiles have known about this possibility for a long time.

As several critics have pointed out, Whitehead has blended genre conventions into other work, notably The Underground Railroad, with its alternative-reality/ steampunk premise of a real railway helping runaway slaves escape. I’d just add that the novel and the streaming series based on it adhere to classic mystery schemas: an investigation pursued by an implacable tracker, and a couple on the run.

The book I mention is currently titled Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder. It’s slated to be published by Columbia University Press, with no release date yet established.

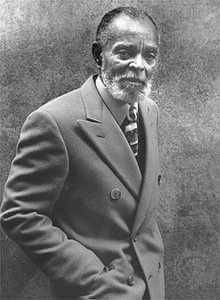

Donald Westlake; Chester Himes; Patricia Highsmith.

Learning to watch a film, while watching a film

The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992).

DB here:

“Every film trains its spectator,” I wrote a long time ago. In other words: A movie teaches us how to watch it.

But how can we give that idea some heft? How do movies do it? And what are we doing?

Many menus

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (2011).

In my research, I’ve found the idea of norms a useful guide to understanding how filmmakers work and how we follow stories on the screen. A norm isn’t a law or even a rule; it’s, as they say in Pirates of the Caribbean, more of a guideline. But it’s a pretty strong guideline. Norms exert pressure on filmmakers, and they steer viewers in specific directions.

Genre conventions offer a good example. The norms of the espionage film include certain sorts of characters (secret agents, helpers, traitors, moles, master minds, innocent bystanders) and situations (tailing targets, pursuits, betrayal, codebreaking, and the like). The genre also has some characteristic storytelling methods, like titles specifying time and place, or POV shots through binoculars and gunsights.

But there are other sorts of norms than genre-driven ones. There are broader narrative norms, like Hollywood’s “three-act” (actually four-part) plot structure, or the ticking-clock climax (as common in romcoms and family dramas as in action films). There are also stylistic norms, such as the shoulder-level camera height and classic continuity editing, the strategy of carving a scene into shots that match eyelines, movements, and other visual information.

Thinking along these lines leads you to some realizations. First, any film will instantiate many types of norms (genre, narrative, stylistic, et al.). Second, norms are likely to vary across history and filmmaking cultures. The norms of Hollywood are not the same as the norms of American Structural Film. There are interesting questions to be asked about how widespread certain norms are, and how they vary in different contexts.

Third, some norms are quite rigid, as in sonnet form or in the commercial breaks mandated by network TV series. Other norms are flexible and roomy (as guidelines tend to be). There are plenty of mismatched over-the-shoulder cuts in most movies we see, and nobody but me seems bothered.

More broadly, norms exist as options within a range of more or less acceptable alternatives. Norms form something of a menu. In the spy film, the woman who helps the hero might be trustworthy, or not. The apparent master mind could turn out to be taking orders from somebody higher up, perhaps somebody supposedly on your side. One scene might avoid continuity editing and instead be presented in a single long take.

Norms provide alternatives, but they weight them. Certain options are more likely to be chosen than others; they are defaults. (Facing a menu: “The chicken soup is always safe.”) An action film might present a fight or a chase in a single take (Widows, Atomic Blonde), but it would be unusual if every scene in the film were played out this way. Not forbidden, but rare. Avoiding the default option makes the alternative stand out as a vivid, willed choice.

Very often, critics take most of the norms involved for granted and focus on the unusual choices that the filmmakers have made. One of our most popular entries, the entry on Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, discusses how the film creates a demanding espionage movie by its manipulations of story order, characterization, character parallels, and viewpoint. It isn’t a radically “abnormal” film, but it treats the genre norms in fresh ways that challenge the viewer.

Because, after all, viewers have some sense of norms too. Norms are part of the tacit contract that binds the audience to creators. And the viewer, like the critic, looks out for new wrinkles and revisions or rejections of the norm–in other words, originality.

Picking from the menu

Norms of genre, narrative, and style are shared among many films in a tradition or at a certain moment. We can think of them as “extrinsic norms,” the more or less bounded menu of options available to any filmmaker. By knowing the relevant extrinsic norms, we’re able to begin letting the movie teach us how to watch it.

The process starts early. Publicity, critical commentary, streaming recommendations, and other institutional factors point up genre norms, and sometimes frame the film in additional ways–as an entry in a current social controversy (In the Heights, The Underground Railroad), or as the work of an auteur. You probably already have some expectations about Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch.

Then, as we get into the film, norms quickly click into place. The film signals its commitment to genre conventions, plot patterning, and style. At this point, the film’s “teaching” consists largely of just activating what we already know. To learn anything, you have to know a lot already. If the movie begins with a character recalling the past, we immediately understand that the relevant extrinsic norm isn’t at that point a 1-2-3 progression of story events, but rather the more uncommon norm of flashback construction, which rearranges chronology for purposes of mystery or suspense. Within that flashback, though, it’s likely that the 1-2-3 default will operate.

As the film goes on, it continues to signal its commitment to extrinsic norms. An action scene might be accompanied by a thunderous musical score, or it might not; either way, we can roll with the result. The characters might let us into their thinking, through voice-over or dream sequences, or we might, as in Tinker, Tailor, be confronted with an unusually opaque protagonist whose motives are cloudy. The extrinsic norms get, so to speak, narrowed and specified by the moment-by-moment working out of the film. Items from the menu are picked for this particular meal.

That process creates what we can call “intrinsic norms,” the emerging guidelines for the film’s design. In most cases, the film’s intrinsic norms will be replications or mild revisions of extrinsic ones. For all its distinctiveness, in most respects Tinker, Tailor adheres to the conventions of the spy story. And as we get accustomed to the film’s norms, we focus more on the unfolding action. We’ve become expert film watchers. We learn quickly, and our “overlearned” skills of comprehension allow us to ignore the norms and, as we stay, get into the story.

Narration, the patterned flow of story information, is crucial to this quick pickup. Even if the film’s world is new to us, the narration helps us to adjust through its own intrinsic norms. The primary default would seem to be “moving spotlight” narration. Here a “limited omniscience” attaches us to one character, then another, within a scene or from scene to scene. We come to expect some (not total) access to what every character is up to.

In Curtis Hanson’s Hand That Rocks the Cradle, we’re initially attached to the pregnant Claire Bartel, who has moved to Seattle with her husband Michael and daughter Emma. When Claire is molested by her gynecologist Dr. Mott, she reports him. The scandal drives him to suicide, and his distraught wife miscarries. She vows vengeance on Claire. Thereafter, the plot shuttles us among the activities of Claire, Mrs. Mott, Michael, the household handyman Solomon, and family friends like Michael’s former girlfriend Marlene. The result is a typical “hierarchy of knowledge”–here, with Claire usually at the bottom and Mrs. Mott near the top. We don’t know everything (characters still harbor secrets, and the narration has some of its own), but we typically know more about motives, plans, and ongoing action than any one character does.

More rarely, instead of a moving spotlight, the film may limit us to only one character’s range of knowledge. Again, scene after scene will reiterate the “lesson” of this singular narrational norm. That repetition will make variations in the norm stand out more strongly. Hitchcock’s North by Northwest is almost completely restricted to Roger Thornhill, but it “doses” that attachment with brief asides giving us key information he doesn’t have. Rear Window and The Wrong Man, largely confined to a single character’s experience, do something similar at crucial points.

Sometimes, however, a film’s opening boldly announces that it has an unusual intrinsic norm. Thanks to framing, cutting, performance, and sound, nearly all of Bresson’s A Man Escaped rigorously restricts us to the experience of one political prisoner. We don’t get access to the jailers planning his fate, or to men in other cells–except when he communicates with them or participates in communal activities, like washing up or emptying slop buckets.

The apparent exception: The film’s opening announces its intrinsic norm in an almost abstract way. First, we get firm restriction. There are fairly standard cues for Fontaine’s effort to escape from the police car that’s carrying him. Through his optical POV, we see him grab his chance when the driver stops for a passing tram.

The film’s title and the initial situation let us lock onto one extrinsic norm of the prison genre: the protagonist will try to escape. Knowing that we know this, Bresson can risk a remarkable revision of a stylistic norm.

Fontaine bolts, but Bresson’s visual narration doesn’t follow him. The camera stays stubbornly in the car with the other prisoner while Fontaine’s aborted escape is “dedramatized,” barely visible in the background and shoved to the far right frame edge. He is run down and brought back to be handcuffed and beaten.

The shot announces the premise of spatial confinement that will dominate the rest of the film. The narration “knows” Fontaine can’t escape and waits patiently for him to be dragged back. In effect, the idea of “restricted narration” has been decoupled from the character we’ll be restricted to. This is the film’s first, most unpredictable lesson in stylistic claustrophobia.

Got a light?

Most intrinsic norms aren’t laid out as boldly as the opening of A Man Escaped, but ingenious filmmakers may provide some variants. Take a fairly conventional piece of action in a suspense movie. A miscreant needs to plant evidence that incriminates some innocent soul.

In Strangers on a Train, that evidence is a cigarette lighter. Tennis star Guy Haines shares a meal with pampered sociopath Bruno Antony, whose tie sports colorful lobsters. Bruno steals Guy’s distinctive cigarette lighter.

Bruno has proposed that they exchange murders: He will kill Guy’s wife Miriam, who’s resisting divorce, and Guy will kill Bruno’s father. Bruno cheerfully strangles Miriam at a carnival, aided by the lighter.

When Guy doesn’t go through with his side of the deal, Bruno resolves to return to the scene of Miriam’s death and leave the lighter to incriminate Guy. The film’s climax consists of the two men fighting on a merry-go-round gone berserk. Although Bruno dies asserting Guy’s guilt, the lighter is revealed in his hand. Guy is exonerated.

Once the lighter is introduced in the early scenes, it comes to dominate the last stretch of the film. In scene after scene, Hitchcock emphasizes Bruno’s possession of it. Sometimes it’s only mentioned in dialogue, but often we get a close-up of it as Bruno looks at it thoughtfully–here, brazenly, while Guy’s girlfriend Ann is calling on him.

When Bruno picks up a cheroot or a cigarette, we expect to see the lighter.

One of the film’s most famous set-pieces involves Bruno straining to retrieve the lighter after it has fallen through a sidewalk grating.

Bruno has dropped it before, during Miriam’s murder, but then he notices and retrieves it. It’s as if this error has shown him how he might frame Guy if necessary. The image of the lighter in the grass previews for us what he plans to do with it later.

What does the lighter have to do with norms? Most obviously, Strangers on a Train teaches us to watch for its significance as a plot element. It’s not only a potential threat, but also Bruno’s intimate bond to Guy, as if Bruno has replaced Ann, who gave Guy the lighter. The film also invokes a normalized pattern of action–a character has an object he has stolen and will plant to make trouble–and treats it in a repeated pattern of visual narration. The character looks at the object; cut to the object; cut back to the character in possession of the object, waiting to use it at the right moment. Our ongoing understanding of the lighter depends on the norm-driven presentation of it.

Once we’re fully trained, Hitchcock no longer needs to show us the lighter at all. En route to the carnival to plant the lighter, Bruno lights a cigarette with the lighter, although his hands conceal it. But then the train passenger beside him asks for a light.

In order to hide the lighter, Bruno laboriously pockets it and fetches out a book of matches.

If we saw only this scene, we might not have realized what’s going on, but it comes long after the narrational norm has been established. We can fill out the pattern and make the right inference. Bruno wants no witness to see this lighter.

The hand that cradles the rock

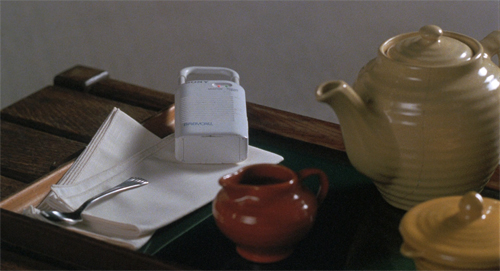

In The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, under the name Peyton Flanders, Mrs. Mott becomes nanny to Claire’s daughter and infant son. Pretending to be a friendly helper, she subverts Claire’s daily routines and her trusting relationship with Michael. As in most domestic thrillers, the accoutrements of upper-middle-class lifestyle–a baby monitor, a Fed Ex parcel, expensive cigarette lighters, asthma inhalers, wind chimes–get swept up in the suspense. Peyton weaponizes these conveniences, and through a somewhat unusual narrational norm the film trains us to give her almost magical powers.

We get Peyton’s early days in household filtered through her point of view. Classic POV cutting is activated during her job interview. She notices that Claire’s pin-like earring drops off and she hands it back to her.

Attachment to Peyton gets more intense when she sees the baby monitor and then fixates on the baby.

We’re then initiated into her tactics, and to the film’s way of presenting them. Serving supper, Claire doesn’t notice that her earring drops off again. Peyton does.

Breaking with her POV, the narration shifts to Claire and Michael talking about hiring her. But this cutaway to them has skipped over a crucial bit of action: Peyton has picked up the earring. Unlike Hitchcock, director Curtis Hanson doesn’t give us a close-up of the important object in the antagonist’s hand. In a long shot we simply see Peyton studying her fingers. Some of us will infer what she’s up to; the rest of us will have to wait for the payoff.

After another cutaway to the couple, Peyton “discovers” the earring in the baby’s crib. Her show of concern for his safety seals the hiring deal and begins her long campaign to prove that Claire is an unfit mother.

This elliptical presentation of Peyton’s subterfuges rules the middle section of the film. Selective POV shots suggest what she might do, but we aren’t shown her doing it–only the results. For instance, Claire lays out a red dress for a night out. Peyton sees it, then sees some perfume bottles.

Cut to Claire and then to an arriving guest, and presto. When she returns to the mirror, her dress is suddenly revealed as having a stain.

Later, Claire agrees to send off Michael’s grant application during her round of errands. Once she gets to the Fed Ex office, she will discover the missing envelope. Before that, though, we get another variant of the intrinsic norm showing Peyton’s trickery.

In the greenhouse, while Claire is watering plants, Peyton spots the envelope in her bag. We don’t see her take it, and there’s even a hint that she hasn’t done so. A nifty shot lets us glimpse her yanking her arm away as Claire approaches. It’s not clear that she has anything in her hand.

In what follows, the narration confirms Peyton’s theft while building up the threat level.

If she’s caught, this woman will not go away quietly.

While cozying up to the children–Peyton cuddles with Emma and even secretly breast-feeds baby Joe–Peyton eliminates all of Claire’s allies. By now we know her strategy, so after she suggests to Claire that the handyman Solomon has been molesting little Emma, all the narration needs is to show us Claire discovering a pair of Emma’s underwear in his toolbox. As with Bruno’s pocketing the lighter in Strangers on a Train, we’re now prepared to fill in even more of what’s not shown: here, Peyton framing Solomon.

Michael, a furtive smoker, sometimes shares a cigarette with Marlene. So it’s easy for Peyton to plant Marlene’s lighter in Michael’s sport coat for Claire to discover. Again, the moment of the theft has given her quasi-magical powers. She sees Marlene’s lighter in her handbag in the front seat.

Again thanks to a cutaway, we don’t see her take it. Indeed, it’s hard to see how she could have; she comes out of the back seat with an armload of plants.

But later Marlene will tell Michael (i.e., us) that she’s lost her lighter, and a dry cleaner will find it and show it to Claire.

The attacks have escalated, with Claire now suspecting Michael of infidelity. She confronts him without knowing that Michael has invited friends to a surprise party for her. Her angry accusations are overheard by the guests, and this public display of her anxieties takes her to a new low.

Peyton’s revenge plan is almost wholly consummated, so we stop getting the elliptical POV treatment of her thefts. Instead, the plot shifts to investigations: first Marlene discovers Peyton’s real identity, with unhappy results, and at the climax Claire does. Her POV exploration of the empty Mott house counterbalances Peyton’s early probing of Claire’s household. When she sees Mrs. Ott’s breast pump–another domestic object now invested with dread–she realizes why baby Joe no longer wants her milk.

This is the point, fairly common in the thriller, when the targeted victim turns and fights back.

In The Hand That Rocks the Cradle, a familiar action scheme–someone swipes something and plants it elsewhere–is handled through an unusual narrational norm. The scenes showing Peyton’s pilfering skip a step, and they momentarily let us think like her, nuts though she is. Thanks to editing that deletes one stage of the standard shot pattern, the film trains us to see how banal domestic items, deployed as weapons, can destroy a family. In the course of learning this, maybe the movie makes us feel smart.

Arguably, we’re able to fill in the POV pattern in The Hand That Rocks the Cradle because we’ve learned from encounters with movies that used the standard action scheme, including Strangers on a Train. This is one reason film style has a history. Dissolves get replaced by fades, exposition becomes more roundabout, endings become more open. As audiences learn technical devices, intrinsic norms recast extrinsic ones and some movies become more elliptical, or ambiguous, or misleading. All I’d suggest is that we get accustomed to such changes because films teach us how to understand them. And we enjoy it.

The passage about training us comes from my Narration in the Fiction Film (University of Wisconsin Press, 1985), 45. I discuss norms in blog entries on Summer 85, on Moonrise Kingdom, on Nightmare Alley, and elsewhere. A book I’m finishing applies the concept to novels as well as films.

The example of mismatched reverse angles comes from The Irishman (2019) In the first cut, Frank is starting to settle his coat collar, but in the second, his arms are down and the collar is smooth. In a later portion of that second shot, Hoffa gestures freely with his right hand, but in the over-the-shoulder reverse, his arm is at his side and it’s Frank who gets to make a similar gesture. To be fair, I should say that I found some striking reverse-angle mismatches in Strangers on a Train too.

For more on conventions of the domestic thriller, go to the essay “Murder Culture.”

Radomir D. Kokeš offers an analysis of how Kristin and I have used the concept of norm. We are grateful for his careful discussion of our work and his exposition of the achievement of literary theorist Jan Mukarovský. See “Norms, Forms and Roles: Notes on the Concept of Norm (not just) in Neoformalist Poetics of Cinema,” in Panoptikum (December 2019), available here.

Strangers on a Train (1951).