Archive for the 'FilmStruck' Category

Time-shifting: THE PHANTOM CARRIAGE on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

Today our comrades at the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck have posted Kristin’s new installment of our series, “Observations on Film Art.” It’s devoted to one of the most complex and intriguing of all silent films, Victor Sjöström’s Phantom Carriage (1921).

Sjöström was one of the greatest directors of the silent cinema. Although many of his films haven’t survived, we’re lucky to have several of his masterpieces, including Ingeborg Holm (1913), Terje Vigen (A Man There Was, 1917), The Girl from Marshy Croft (1917), The Outlaw and His Wife (1918), The Sons of Ingmar (1919), The Scarlet Letter (1926), and The Wind (1928). He mastered tableau staging in the early 1910s, then quickly learned the nuances of continuity editing, all the while drawing splendid, subtle performances from his actors.

The Phantom Carriage is a sort of horror fantasy. The premise is that the last person to die in a year becomes the escort for the dead of the following year. To this striking idea, taken from a novel by Selma Lagerlöf, the film adds an exceptionally intricate flashback structure.

Silent films made frequent use of flashbacks, usually brief ones to remind the audience of things seen earlier in the film, or longer ones that supplied backstory for the current situation. (In this respect, our films today are rather similar to silent movies.) The Phantom Carriage pushes farther, building its plot out of blocks of flashbacks that are presented out of chronological order, and not all representing memories. It was as daring in its time as The Power and the Glory (1933) and Citizen Kane (1941) were in theirs.

Because of its complexity, The Phantom Carriage long circulated in versions that were cut and rearranged. Once it was restored, we could appreciate just how ambitious a movie it was. Kristin traces the film’s various time schemes and shows that the shifts of chronology and point of view powerfully enrich a story of a man’s hard-won redemption. Her comments are enhanced by some excellent graphics from the keyboard wizards at Criterion.

As ever, we thank our Criterion collaborators: Kim Hendrickson, Peter Becker, Grant Delin, and their team.

A complete listing of our thirteen “Observations” entries is here. For more on Sjöström’s films, see our director tag.

The Celestial Arthouse: FilmStruck and Criterion Channel with an offer hard to refuse

DB here:

Here’s the big news. FilmStruck has instituted a student rate for subscriptions: 35% off the monthly rate, which means $39.99 for six months, or less than $7 a month. The Criterion Channel is included in this deal. Not only students but educators are eligible; it applies to anyone with an email address ending in .edu. You can get more information here.

In the current context, this seems to me a real bargain. Cord-cutting and cord-shaving are making streaming more and more common. But at least your cable subscription bundled a lot of channels offering movies from a wide range of sources. Now we face the prospect of each “content owner” setting up a dedicated streaming service.

Netflix and Amazon and Apple and YouTube are funding and buying exclusive rights to films and TV shows. Hulu remains as a source of Disney, Fox, and Warners properties, but that bundle is coming untied. Disney is planning to claw back most of its films for its proprietary streaming service. How soon before other studios mount their own streaming services?

The total cost of subscribing to your favorite services may rival a cable bill. Recognizing this, the studios have banded together to merge access to several of these sources in an app called Movies Anywhere. But that’s for convenience; you’re still paying out to many providers.

Ten years ago, Kristin and two major archivists expressed skepticism about the arrival of the Celestial Multiplex. Never would everything–really, everything–be available. In fact, as licenses expire and Peak TV drives streaming, Netflix and other services have trimmed their foreign and classic libraries.

This makes film FilmStruck an even more stupendous opportunity for film lovers. It remains a big, fat aggregator. Where else can you see, on a single night, a cache of 80s indies, eight movies by Phil Karlson, seven by Herzog, seven from Tunisia, Toshiro Mifune slicing and dicing his adversaries, a rare trove of French films made under Nazi Occupation, and several debut films by major filmmakers? And that’s before you get to the Criterion Channel, which currently offers Belle de Jour, Kore-eda’s Still Walking, The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (with a unique le Carré interview), The Color Wheel, and hundreds of other titles. Not the Celestial Multiplex, but close to a Celestial Arthouse. It’s what the prophets of cable TV told us to expect, but never arrived: access to world culture, at the time and place of your choosing.

I get it, dude. Movies.

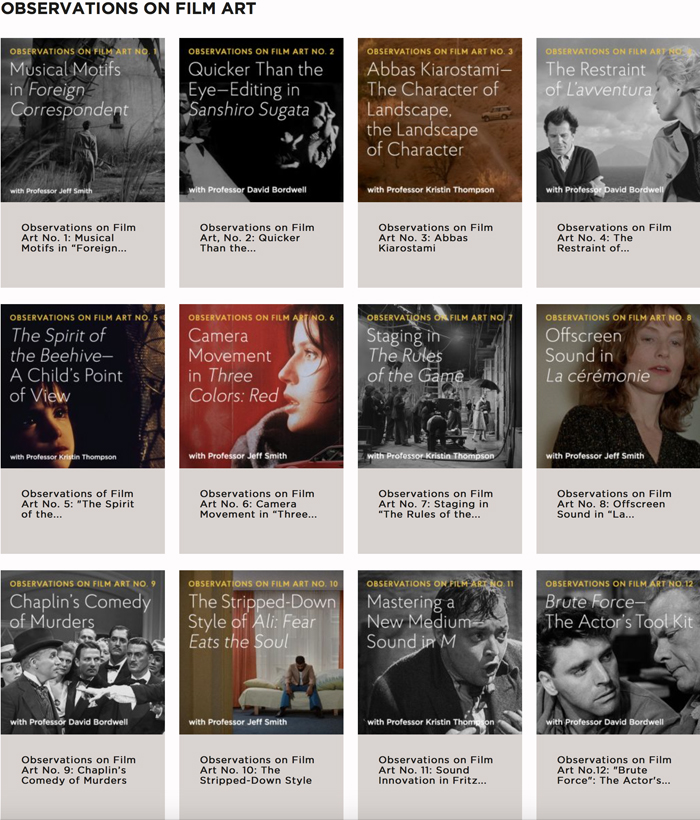

Criterion’s new deal comes at the one-year anniversary of our series, “Observations on Film Art.” Kristin, Jeff Smith, and I have posted twelve installments, with more in the works. You can access them here, if you’re a FilmStruck subscriber. Several of these are developed further in blog entries; just go to our FilmStruck tag.

The anniversary set me thinking about streaming as a way of accessing movies. For home viewing I prefer discs, but more and more I watch streaming, usually to help my research. Several obscure 40s films I studied for my new book were available only on Amazon Prime, so those got my attention. Likewise, while revising our film history text, we checked on foreign-language titles not available on disc. But now I realize that to keep up with independent films I need to stream. The quite good I Don’t Feel at Home in This World Anymore didn’t get a theatrical release and doesn’t seem to be on DVD.

What startles and sort of dismays me most is the way Netflix and other services let recent releases swamp the classics and imports they still have. I’m also a bit put off by the vastness of the choice, the grid of thumbnails like stamps in a huge album. A friend told me of her husband browsing titles for so long that they give up deciding on a movie and opt for the latest episode of a TV show.

Video stores were also vast, but they came with benefits. Rereading Tom Roston’s enjoyable I Lost It at the Video Store: A Filmmakers’ Oral History of a Vanished Era, I was reminded how important gatekeepers and tastemakers are. The best rental shops had knowledgeable clerks, wild categories, and displays that highlighted choices by staff. What we now call “curation” was in place, sometimes in a gonzo way, to guide people through the mass of VHS boxes. Kevin Smith:

I’d try to tell people what to rent even if it was the same stupid shit over and over. I was like, “I get it, dude. Movies. Who gives a fuck what they are.” I loved talking with people. There was no Internet, so you couldn’t jump on a message board or Twitter. “This is what I loved about Guardians of the Galaxy. I am Groot! #fuckin’thismovierocks.” You didn’t get to do that. You gotta do that in person with people.

FilmStruck, while offering hundreds of titles, has regained some of that curatorial function. You can still wander freely through the catalogue, but there are also interviews, talking-head introductions, categories both obvious and imaginative, and video essays of the sort you’d find in DVD supplements. For our series, we try to hold onto a personal touch. The installments are monologues, but we think we’re steering you toward what to appreciate in the movies we talk about. At least there’s a little more sense of human contact that way. And we hope our enthusiasm shows that analyzing film aesthetics doesn’t have to be dry and bloodless.

Thanks as ever to our collaborators at Criterion: Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and their colleagues.

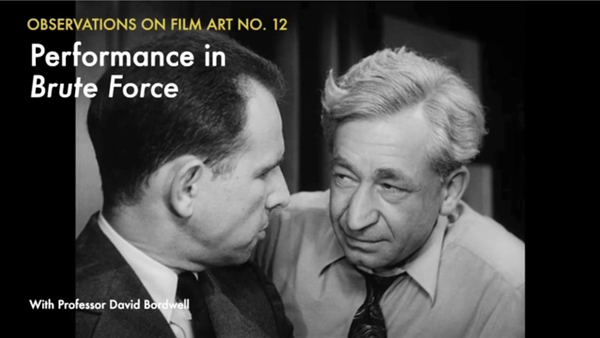

Biomechanics goes to the Big House: BRUTE FORCE on the Criterion Channel

DB here:

If there’s one film technique that probably everybody notices, it’s acting. Reviewers are obliged to judge performances, and viewers often comment that this or that actor was admirably controlled, or wooden, or over the top. Yet acting is surprisingly hard to describe; the critic who can do it engagingly, as Pauline Kael could, wins plaudits.

I think it’s fair to say that film analysts haven’t on the whole found good ways to analyze acting. There are books about historical acting styles, and there’s a very good theoretical overview by—no surprise—Jim Naremore. Our colleagues Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs have produced a superb study of acting in the early feature film, with careful attention to the conventions of the period. But I think there’s still more to be done in terms of analyzing how performers achieve their expressive effects.

Or so I suggest in the newest installment of our series, “Observations on Film Art,” on the Criterion Channel of FilmStruck. Using Brute Force as an example, I try to lay out in brief compass some primary tools that actors wield. There’s an excerpt here. Today I’ll sketch out what I tried to do.

Bits selected and amplified

Talk about acting tends to set “realism” or “verisimilitude” against “artifice” or “stylization.” The Method, we sometimes say, is an example of realism, while Expressionist acting à la Caligari is at the opposite pole. Classic Hollywood acting, from the late 1910s into the 1940s, we might say ranges across the middle.

Accordingly, some theorists of acting are realists, favoring one zone and finding the other too artificial. Others are conventionalists; they argue that all acting, even the most apparently realistic, is actually stereotyped. It looks realistic because we accept the conventions of a time or tradition as the way people actually behave.

I think it’s worth suspending this polarity and simply looking at how performances are built up out of pieces. Like Meyerhold’s Biomechanics and Kuleshov’s engineering approach to acting, my perspective here is that of seeing performances as clusters of controlled choices about specific bodily behaviors.

As a first approximation, I propose that acting of any sort starts with some norms of human facial, vocal, and bodily expression.

Many of those norms might be universal. I’m risking disagreement here, since the US humanities are predicated on a fairly radical relativism. But I think that’s implausible. Is there any culture where smiling reliably indicates unhappiness? When frowning and shaking your fist in someone’s face indicates affection? Where pointedly turning your back on someone shows a willingness to engage socially? Where sloping your shoulders, tipping up your inner eyebrows, rearing back your head, turning down your mouth, and wailing indicates joy rather than misery? (The guitar-hugging rocker’s cry of anguished teen spirit draws on the ensemble of cues we see in the mother cradling her wounded child.) Nobody expresses pride by dropping to a crawl.

The context can qualify or negate these signals, of course. One may smile and smile and be a villain. But exactly because cordial smiling isn’t the default signal of villainous purpose, Shakespeare is able to make his point about deception. Any expression can be faked; that’s what acting is. At bottom, though, taken singly and reinforced by other inputs and circumstance, there are some reliable expressive cues in the typical case.

But even if you believe in the social construction of everything, my point still carries. Humans in any community emit a stream of behaviors in face, voice, hands, posture, stance, and so on. Maybe those bits are wholly constructed socially, or maybe universal proclivities play a role too. In any case, what the actor does, I posit, is survey the range of such behavioral possibilities for the role she is to play. She then does two other things.

First, she selects only a few. Any performance depends on picking a few behavioral bits to carry expressive impact.

Second, at any given moment, the selected features are emphasized, even exaggerated. The actor bears down on the selected behavioral bit, dwelling on it. The clumsy, sometimes contradictory flow of real-life behavior gets simplified and streamlined for easy uptake.

For example, certain body parts may dominate the impression. If we’re to watch the hands, the face can be fairly neutral.

Correspondingly, in cinema the shot can be scaled to stress the one gesture—in this case, a pat of comradeship.

If we’re to watch the face, keep the hands and body still. Film technique can help you by recruiting our old friend the facial view. I talk about several examples in Brute Force, of which this is one of my favorites—two frontal faces, blatantly unrealistic but riveting (as Eisenstein knew; see below).

Only the eyes move, and one mouth, barely.

Or, if we’re to watch an eye-flick, keep the face neutral.

Indeed, you can argue that the development of the intensified continuity style, which concentrates on facial close-ups, gave the actors less to do with their hands and bodies than did the greater range of shot scales available to studio cinema from the 1910s to the 1960s.

To smack us with a bigger impact, the filmmakers add up the channels. In this scene of Brute Force, the commissioner takes control of the prison from the warden, and the two men’s facial expressions—determination on one, fear on the other—are amplified by their paired gestures of wrestling for the loudspeaker.

The effort shows not only in their postures and fingers but their faces.

At high points, we can go for all-over acting, face and gesture and bearing and voice, as when the snitch faces his fate in the machine shop.

But note that even here, as an ensemble element, other factors are neutralized. The attackers are seen from the rear and poised or moving stiffly and inexorably. Similarly, the pure animal outburst of Lancaster’s performance at the climax depends on several factors of expressive movement swept together.

Wounded, he lets his boiling rage explode; even the frame can’t contain him. But even here there’s selection and emphasis. The head and voice and straining neck do all the work, while the arms remain taut.

The tools I survey are simple ones: eye areas (not so much the eyes as the lids and brows), mouth, tilt of the chin; bearing and stance; hand gestures; and rhythm of walking. In the Observations installment, I look at how the performances in Brute Force play off against one another, and I sum up the resources in Lancaster’s fierce performance, using all of the tools he had. That wedge of a back. Those mitts. Those slightly shifting eyes.

For preparing the Criterion Channel installment, thanks as usual to Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, Peter Becker, and all their colleagues.

The theatrical tradition is discussed by Alma Law and Mel Gordon in Meyerhold, Eisenstein, and Biomechanics (new ed., McFarland, 2012). On Kuleshov, see Kuleshov on Film, ed. Ron Levaco (University of California Press, 1974), pp. 99-115. I discuss Eisenstein’s approach to these problems, what he called mise en geste, in The Cinema of Eisenstein, pp. 144-160.

On actors’ use of eyes, go here; on hands, try this. I’ve discussed Lancaster’s skills before, here. More generally, when it comes to pictorial representation I defend a moderate constructivism against pure relativism here.

Ivan the Terrible Part II (1958).

Mmm, M good

DB here, boasting about Kristin:

Our series on the Criterion Channel on FilmStruck continues with this month’s entry, Kristin on M as an exceptionally rich sound film. She talks about how Lang adapted silent-film techniques to the demands of sound while also using sound to achieve effects that couldn’t be achieved purely through images.

Watching her discussion and the clips, I was reminded of what a precise director Lang was–a unique mixture of stylistic flamboyance and swift economy. You see that mix in silent masterpieces like the Mabuse films, Metropolis, The Niebelungen, and Spione. In various entries (here and here and here) I’ve dwelt on his poised, meticulous compositions that use the entire frame area. Sound gave him a new set of resources for dynamic expression. Rather than becoming more conventional, Lang’s American films seem to subtly absorb the discoveries of M. Examples are the tapping of the “blind” man’s cane in Ministry of Fear and the ominously croaking frogs in You Only Live Once. And the propulsive sound cuts in his last film, The Thousand Eyes of Dr. Mabuse, show that he never forgot that sound could be edited as freely as images.

You can sample a clip from the episode at On the Channel at Criterion’s site. A complete list of the Observations on Film Art series (eleven already!) is here. Go here for blog entries offering background on those installments.

Thanks as ever to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and all their teammates at Criterion.