Archive for the 'Directors: Oliveira' Category

Another dispatch from Vancouver

Kristin here:

Surviving Life (Czech Republic; dir. Jan Švankmajer, 2010)

I became a fan of Švankmajer’s work back in 1988, when I saw Alice, his first feature. David and I gradually explored his shorts and discovered that some of them were among the great classics of the animation form, perhaps most notably Jabberwocky and Dimensions of Dialogue. Švankmajer mostly concentrated on object animation, often combining found objects like tools, stuffed animals, dentures, and food in bizarre ways to create figures.

But after Alice, Švankmajer continued to make features, and they contained less and less of what he was best at: animation. Faust was all right, but I suffered through Conspirators of Pleasure and skipped Lunacy altogether. The director has claimed that Surviving Life is to be his final film, so I thought I owed him a last chance. It’s lucky I did, since it’s a real comeback for him, and a return to what he does best.

Whether Švankmajer really wanted to eschew live-action filmmaking and take up animation again is a moot point. He appears in a prologue, not exactly as himself but as a pixillated cut-out photographic figure (apart from the same typical cut-ins to real speaking mouths that became rather tedious in Alice). He describes how he intended to make a live-action feature, but with a small budget could only afford cut-out animation. He demonstrates by hopping about the frame like a figure in a child’s TV show. At the end, he checks how much time the prologue has taken up–two and a half minutes–and mutters that it’s not very long. His mordantly amusing speech doesn’t suggest whether he really had tried to make the film with live action. Indeed, the actors who are represented by the cut-out photographs obviously had to act out their movements, in costume, and to provide their voices. How much cheaper all this could be is debatable.

The story is about dreams, and specifically about a man stuck in a dull desk job who dreams of an exotic woman in red. His doctor sends him to a psychiatrist whose office contains photos of Freud and Jung, each of whom listens and reacts with applause or contempt when his own or his rival’s theory is employed. The hero is horrified when he discovers that the psychiatrist is trying to rid him of his dreams when his own desire is to live within them.

We tend not to think of cut-out animation when we think of Švankmajer, but predictably he proves a master of it. At times the technique resembles that of Terry Gilliam in the animated interludes of Monty Python’s Flying Circus, especially in scenes shot in a black-and-white cityscape with surrealist objects emerging from the windows (see above and below). The “actors” appear as smoothly animated photographs except for close shots, when the actual actors are shown. The technique works brilliantly, with the cuts between the image and the real person being smoother than most Hollywood matches on action.

If Švankmajer has chosen this as his swan song, he has gone out reminding us why we admired him in the first place.

The White Meadows (Iran; dir. Mohammad Rasoulof, 2009)

There are probably a lot of indirect comments on the political situation in Iran in films from that country. Some are obvious to all, others no doubt only to people who live that situation every day. Few, however, can be so overtly allegorical as The White Meadows. Oddly, the allegorical implications are so clear that they can be grasped immediately and do not impinge on the intriguing strangeness of the tale being told.

The central figure is a man who rows his small boat across a highly saline sea, stopping at islands and coastal villages in deserts caked with salt formations. (Yes, another Iranian journey film.) At each stop he gathers the tears of the local people, gradually accumulating a small bottleful. Each stop also yields a fable-like incident that reflects the plight of certain sectors of Iran’s population: a beautiful virgin is sent as a sacrifice to a sea god, an unconventional artist who refuses to paint naturalistically is tormented and sent into exile, and so on. The overall impression is of universal suffering, and the ending suggests that this suffering benefits only the rich and privileged.

The white and tan landscapes and pale blue sky and sea provide stunning locales for this simple tale, shot around Lake Urmia in northeastern Iran.

While watching The White Meadows, one wonders how Rasoulof could get away with such an overt criticism of religious and governmental repression in Iran. He couldn’t, quite. He was arrested alongside Jafar Panahi (who edited The White Meadows) and about a dozen others on March 2. Fortunately he was released fairly soon, on March 17. What his future as a director in Iran is remains to be seen. The government has long tolerated having one set of films for local popular consumption and another that will be confined largely to the international festival circuit. Not surprising, since these days Iran’s filmmaking is one of the few areas in which the country is seen internationally in a positive light. Still, such a bitter yet appealing film clearly stretches such tolerance.

Every year it seems more and more likely that the increasingly tenuous new Iranian cinema will finally be snuffed out, and every year–so far–we see bold and imaginative films coming from that country. We can only hope that with the arrests earlier this year, we are not seeing the long-expected end.

The Strange Case of Angelica (Portugal/Spain/France/Brazil; dir. Manoel de Oliveira, 2010)

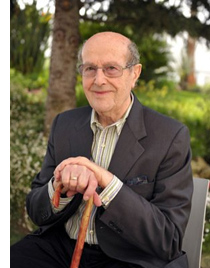

The fact that Oliveira was 101 when he made this film, as well as the fact that he is still directing at least a film a year (for last year’s Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, see here), is too extraordinary not to be remarked on. Yet we shouldn’t let it dominate our view of Angelica or tempt us to treat it as an old man’s film. Slowly paced and meditative it may be, but it is also imaginative and full of humor, despite being centered around a young man’s obsessive love for a dead woman.

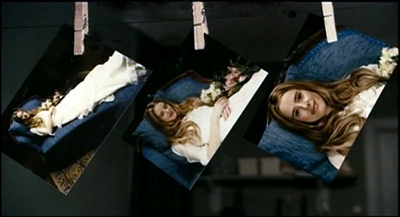

The protagonist, Isaac, is a photographer living in a boarding house in a town in the Duoro Valley region of Portugal. (Oliveira’s first film was a beautiful city symphony, Douro, Faina Fluvial, a poetic study of the river in the same valley made in 1931.) Called upon to photograph a beautiful woman who has died shortly after her wedding, through his viewfinder he sees the corpse open her eyes and smile at him. The same thing happens when he gazes at photos of her hung up to dry:

He falls in love with her, and her ghostly figure visits him at night, wafting him up into the air and flying over the river with him. Although he wakes from dreams several times, we are left in doubt as to whether Angelica really has been appearing to him.

The film seems to be set in contemporary times, and yet it has an old-fashioned look t it. The protagonist photographs men at work with hoes in a nearby vineyard, though his landlady remarks that no one does manual labor anymore. But most obviously, the film has the look and feel of a silent film. The shots of Angelica and the hero flying are superimposed ghostly figures straight out of Edwin S. Porter’s Dream of a Rarebit Fiend (1906). Camera movements are used sparingly, as in many silent films. Scenes often consist mostly of the hero taking his photographs or thinking of his phantom love, and his occasional cries of “Angelica!” could be rendered as intertitles. The use of solo piano music by Chopin reinforces the sense of watching a “silent” film.

(1906). Camera movements are used sparingly, as in many silent films. Scenes often consist mostly of the hero taking his photographs or thinking of his phantom love, and his occasional cries of “Angelica!” could be rendered as intertitles. The use of solo piano music by Chopin reinforces the sense of watching a “silent” film.

Yet there are occasional scenes of dialogue. The best scene in the film may be the one where over the breakfast table the other boarders discuss their concerns about Isaac’s state of mind. The scene ends amusingly with the camera holding on the landlady’s bird jumping around its cage, watched with great attention by her cat.

Oliveira will turn 102 on December 11. He is listed on Wikipedia has being in pre-production for A Missa do Galo.

Kawasaki Rose (Czech Republic; dir. Jan Hrebejk, 2009)

(Note: Many reviews and the VIFF program give the title as Kawasaki’s Rose, but the title on the film is as given above.)

This film creeps up on you. At first it seems poised to be yet another study of a failed relationship among upper-middle-class characters. A documentary is to be made about Pavel Josek, a noted professor famous for his past resistance to the Communists. The sound-man on the shoot is his son-in-law Ludek. His daughter Lucie has been told that a large tumor just removed is benign. Ludek confronts her with the fact that he has been cheating on her during her illness, and he undermines her efforts at disciplining their daughter.

But this conventional soap-opera material gradually opens out as files discovered during research for the documentary seem to reveal that Josek had in fact cooperated with the Communist regime, apparently including his participating in the torture of prisoners. From that point, Ludek recedes into the background and further political and personal revelations give the film considerable depth and complexity.

Kawasaki Rose was beautifully shot in full anamorphic widescreen, with images around the harbor in Göteborg, Sweden being particularly well composed.

While I was watching the film, I was reminded equally of Wajda’s Man of Marble and von Donnersmarck’s The Lives of Others. On the one hand, a film project that digs into the past of a heroic figure who turns out to be not quite so heroic, and on the other a study of the effects of interrogations into private lives under a totalitarian regime.

Kawasaki Rose (the title derives from an origami pattern and is given to a Japanese character in the film who paints flowers) is the Czech Republic’s entry for a foreign-film Oscar nomination. I wouldn’t be surprised if it gets one.

Revenge of the ROW

Sun Spots.

DB here:

Watching Congress on C-SPAN makes you realize that the dead outnumber the living. Likewise, going to a film festival like Vancouver’s drives home to you how many movies there are out there. The world produces about 5000 features per year. No more than fifteen per cent of those come from the United States. That leaves about 4300 from what Hollywood execs apparently, and disparagingly, call ROW—the Rest Of the World. And hundreds of those 4300 are fighting for spots at the film festivals that have sprung up around the globe. Hence the rise of the programmer, today’s art-film gatekeeper and tastemaker.

To be a programmer you must be knowledgeable, traveled, and well-networked. You have to be steeped in contemporary film, you have to make your way to obscure places, and you have to know the right people—filmmakers, producers, sales agents, critics you can trust. Hence the power of a festival like Vancouver’s. It has superb programmers like Tony Rayns, Shelly Kraicer, Mark Peranson, Terry McEvoy, Stephanie Damgaard, Tom Charity, Sandy Gow, Tammy Bannister, and their colleagues.

You could mount a perfectly respectable event by cherry-picking other festivals’ lineups, but Vancouver mixes current international hits with genuine discoveries. Vancouver’s recognized specialties, like new Asian film, documentary, and Canadian features, nicely counterbalance their obligation to bring to the community the latest in top-drawer films of all sorts. A user-friendly festival in an exceptionally welcoming and picturesque city, Vancouver remains a magnet for us and hundreds of other cinephiles. This is my fifth visit, and Kristin and I commented online in 2006 (start here), 2007 (start here), and 2008 (start here).

This year’s Vancouver doesn’t lack big-name attractions. Keeping up their dedication to Manoel de Oliveira (a ripe 100-plus years old), the programmers have brought us Eccentricities of a Blond Hair Girl, a sixty-minute package of pure pleasure. At first it seems a redo of Obscure Object of Desire. A man on a train recounts his frustrated efforts to marry a gorgeous young woman he glimpses at a window. But it turns out that this is an adaptation of a short story by Eça de Quieró, and things develop in very different directions than in Buñuel’s film. Oliveira’s characteristically chaste framings and sumptuous décor are enlivened by some errant formal devices that it would be a shame to divulge.

Okay, I’ll mention one because it kicks in from the start. On the train, Ricardo decides to tell his story to the woman sitting next to him. But while listening she usually looks straight into the camera. And every time she replies to his remarks, instead of turning to look at him, she delivers her lines directly to us. Ricardo looks at her, or sometimes just glances around as speakers do, but during her lines, the camera acts as a relay between her and him. You never quite get used to this strange displacement of dialogue, and it helps make Ricardo’s tale of archaic courtly love as subtly unnerving as the revelation that seals the couples’ fate. Whippersnapper directors a third Oliveira’s age would not dare so much.

Another much-awaited title was Bong Joon-ho’s Mother, and the hopes I expressed in the previous entry weren’t disappointed. A mentally handicapped boy is accused of murder, and his mother leaps into action to find the killer. As in Bong’s earlier Memories of Murder, a mystery intrigue ramifies into the lives of disparate characters, so that we’re skittering between physical clues (a golf club, inscribed golf balls, a strangely positioned corpse) and psychological ones, with bits of behavior serving to suggest multiple motives. Each character continues to surprise us—in particular, the sneering wastrel who takes advantage of the son. Driving the plot and passing through a spectrum of emotional changes, of course, is the title character. There’s no shortage of movies called Mother (though we’re told this one should properly be translated as Mother/Murder), but veteran actress Kim Hye-ja as the indefatigable guardian of her boy is as memorable as Pudovkin’s and Naruse’s protagonists.

Bong’s compact compositions are always at the service of his storytelling. I couldn’t see any fat on the scenes. His fluent pacing squeezes suspense and surprise out of each plot convolution. While the mother talks to her boy in jail, the lawyer stands at a distance from them, and, slightly out of focus, checks his watch. Instantly we know that he’s uninterested in the case. But Bong also knows how to linger. One of the most memorable slow dissolves I’ve seen in recent years counterposes mother and son, sleeping alongside each other off-center, against a horrific discovery tucked against the other edge of the anamorphic frame.

Mother has plot to spare; it could loan some to Sun Spots. What hath Hou wrought? I thought during the first few minutes of this exercise in Asian minimalism. This relentlessly dedramatized tale of a fugitive triad who meets a sulky girl in the countryside is determined to deny us any significant action, intense emotion, or old-fashioned enjoyment. Long shots, some very distant; thirty-one single-take scenes; impassive actors smoking, staring, turning from the camera, and generally hanging out: We have been here before. After twenty years of masterpieces by Hou, Kore-eda (Maboroshi), and Jia Zhangke (Platform), this style risks mannerism.

Eventually, though, I shifted gears and came to respect the movie. First, the landscapes are ravishing, worthy of a James Benning film. (8 ½ x 11, in which narrative gestures are swallowed up in immense spaces, wouldn’t be an irrelevant comparison.) Second, many compositions develop in unpredictable ways, and you’re given enough time to scan the frame for clues to what has happened before we join the scene. You’re obliged to notice handbags, cellphones, fishing poles, and cigarette butts strewn across the visual field. Third, director Yang Heng has exploited one powerful advantage of HD video: razor-sharp depth of field. This allows him to integrate distant hills and streams into the action. You see everything sharp and fresh, even actions hundreds of yards away. The final nine-minute shot forms a kind of climax of spatial acuity. A couple, trailed by a solitary figure, drift away from us into a grove of trees, and they remain visible as patches of white and black for an achingly long time before finally disappearing. Here “vanishing point” takes on its full meaning. Unthinkable on DVD, Sun Spots lives fully on the big screen, and one has to respect Yang’s single-minded commitment to making an anecdotal plot into something austere and sensuous.

Sun Spots was a world premiere, and it illustrates just how committed Vancouver is to continuous discovery. Also in the revelations category is Guan Hu’s Cow, which takes us into the territory so successfully covered by Jiang Wen’s Devils on the Doorstep. (2000). The Chinese countryside is under siege from the Japanese, and survival is the name of the game. A village comes into possession of a huge European heifer and revels in her apparently boundless supply of milk. But the Japanese army has other ideas, and it’s up to the fumbling but plucky farmer Niu Er to protect the cow while evading the enemy. Cow is currently filling Chinese theatres, and the poster suggests a light-hearted adventure, but actually the comedy comes in a rather violent context. If told chronologically, the plot would turn steadily dark, so Guan adroitly uses flashbacks to keep offsetting horror with humor. Once more, popular cinema shows itself able to handle emotional extremes with a steady hand.

Sun Spots was a world premiere, and it illustrates just how committed Vancouver is to continuous discovery. Also in the revelations category is Guan Hu’s Cow, which takes us into the territory so successfully covered by Jiang Wen’s Devils on the Doorstep. (2000). The Chinese countryside is under siege from the Japanese, and survival is the name of the game. A village comes into possession of a huge European heifer and revels in her apparently boundless supply of milk. But the Japanese army has other ideas, and it’s up to the fumbling but plucky farmer Niu Er to protect the cow while evading the enemy. Cow is currently filling Chinese theatres, and the poster suggests a light-hearted adventure, but actually the comedy comes in a rather violent context. If told chronologically, the plot would turn steadily dark, so Guan adroitly uses flashbacks to keep offsetting horror with humor. Once more, popular cinema shows itself able to handle emotional extremes with a steady hand.

Kristin and I have already seen plenty of other films we want to commend to you, but hitting four screenings a day hasn’t left us a lot of time to blog. Still, we’re determined to bring you more comments on this wondrous festival’s offerings.

Cow.

Movies that restore your faith in cinema, and audiences

David from Vancouver:

One of the pleasures of film festivals is the enthusiasm you pick up from the audiences. Queueing for a screening, you can talk with people about what they’ve seen or expect to see. This festival is so popular locally that some viewers take a week or two off work. Then sitting in the theatre and waiting for the show to start, you hear fascinating conversations. Last night, a young Taiwanese man (Frank) and a young Korean woman (Yuri) were sitting behind me and talked about what they were looking forward to, what they’d seen on DVD, how they came to Canada, and so on. Their love of cinema shone through plainly; somebody should make a movie about their lives.

People have every reason to be fired up about this festival. After five days here, I’m awash in fine movies. Besides the ones I’ve already noted, here are some standouts:

Opera Jawa: An ambitious reworking of an episode from the Ramayana, full of splendid imagery—everything from elaborate dance numbers to sudden appearances of shadow puppets. The soundtrack is equally lush, with gamelan mixing with more pop-flavored melodies, and the classic tale is intercut with current political struggles.

Monkey Warfare: A clear-eyed study of baby boomers stuck in late midlife, recalling their 1960s activism with both pride and guilt. It’s tough to make a movie with only three principal characters, but Reg Harkema pulls it off, blending comedy and drama and throwing in enough neo-Godardian flourishes to keep you off-balance. A very funny post-credits sequence. (But don’t Molotov cocktails also contain sand?)

The Magic Mirror: I tend to like about half of Manoel de Oliveira’s works, and I thought during the first forty-five minutes that this wouldn’t be one of them. Of course everything was filmed with his quiet majesty. (Advocates of the “clean image” furnished by HD should study what O’s films can squeeze out of Eastman stock: his etched, enameled images make every texture pop out at you.) But the early scenes feature rather repetitive dialogues about a wealthy woman who hopes to be granted a vision of the Virgin. I couldn’t see where all this was going and suspected that I was in the presence of what my friend J. J. Murphy, borrowing from Manny Farber, calls elephant art.

So I was squirming until a forger enters the scene with a plan to stage a vision for Mme Elfreda. Things get stranger and more elliptical, moving toward luminous glimpses of her final journey to Venice and Jerusalem. By the end I was completely won over by this grave, wise film. Now I have to go back and watch the beginning to see what I missed. You have to take these things on trust, especially from a director who’s lived nearly a hundred years.

Big Bang Love—Juvenile A: I’m not a big admirer of Miike Takeshi’s films, but I liked this better than most. Very stylized treatment of a young bully’s death in prison, with startling images and passages of brilliant cutting, and a landscape that haunts you. (Let’s just mention the pyramids and the rocket ship.)

Syndromes and a Century: A teasing, mesmerizing string of situations involving two doctors in a Thai hospital. Shot largely in long, distant takes, the film works out variations in its conversations among doctors, patients (including two Buddhist monks) and their lovers. Plot lines are sketched without being consummated, and the viewer is coaxed into imagining different futures for the people who drift into our ken. Apichatpong Weerasethakul, maker of Mysterious Object at Noon and Tropical Malady, has emerged as the major Thai director with his enigmatic and engrossing films. For those of you in the Midwest, take pride: He studied at the Film School of Chicago’s Art Institute.

Still Life: Jia Zhangke’s newest feature, crowned at Venice, has immediately become my favorite of his works. The city of Fengjie, being slowly demolished before it will be flooded by the immense Three Gorges Dam, becomes as vivid a presence as the theme park in The World. Day laborers take shelter in collapsing buildings, and prostitutes ply their trade in rooms with only three walls. One worker has come to town looking for his ex-wife; a woman has come from Shanghai seeking to divorce her husband.

The parallels aren’t forced, and the two stories are integrated by one of the most daring visual surprises I’ve seen in recent cinema. The stories are intimate, built out of small-scale encounters and daily routines, but they feel oddly epic too, as the hollowed-out city crumbles around the characters. In fewer than two hundred shots, many of them gliding along surfaces and faces, Jia presents a vision of humans obstinately seeking a better life. Shot on HD and projected on video, Still Life proves that digital filmmaking can evoke both thumping immediacy and poetic abstraction. (Keep your eye on the backgrounds.) It’s been acquired for Canada: What stateside distributor will pick it up?