“Best Picture” ≠ “Live Action”

Saturday | July 8, 2023 open printable version

open printable version

Wreck-It Ralph (2012).

Kristin here:

Way back in 2006, I posted a long piece on the increasing prominence of animated features being released each year. This was in the infancy of the blog, and the entry shows it–few photos, inserted as thumbnails. We only gradually worked up to our format of posting plenty of illustrations. By contrast this current contribution offers plenty of visual pleasure.

Basically I argued three points. First, that by their nature animated films would tend to be among the highest-quality films in any given year, despite their relatively small number in those days.

My argument laid out some reasons for this high quality. First, the fact that animated films were perforce thoroughly planned in pre-production, meaning that every detail was carefully considered. This means that relatively few inadequate scenes are reworked in production. Live-action films these days tend to be heavily dependent on shooting lots of coverage and making many decisions in the editing stage. Not true of animated films. Similarly, the soundtrack is recorded in advance and the images animated to sync with it. Hence the sound is meticulously planned. The voice actors record their voices and leave, usually not hanging around to try and change their scenes during shooting or fluffing lines and thus requiring multiple retakes of scenes.

My second point addressed the opinion, widely circulating in the trade press, that the spread of animation, and particularly digital animation, was a mistake. I quoted a recent Screen International article: “Much has been made this year of the seeming over-saturation of studios’ computer-generated titles, with critics and analysts pointing to growing movie-goer apathy.” I pointed out that such a claim didn’t fit the facts: “As a proportion among the total number of films made, CGI’s box-office successes seem fairly high compared to live-action films.”

My third point was that American distributors did not know how to market films from abroad, so that Ghibli and Aardman titles did not get nearly the audiences they deserved. Since then the distributor GKIDS has shown that it’s possible, at least for a relatively small company, successfully to release such films. They currently offer films with eleven best-animated feature Oscar nominations (with one win, Spirited Away), having gained distribution rights to Ghibli films, previously controlled by Disney.

Since I wrote that entry, the number of animated films, mostly digital, released yearly has sharply increased. And the disproportionate number of those animated films that appear among the top hits of the year continues to demonstrate that people are not apathetic. The spread of streaming services, combined with the decline of theatrical attendance during the pandemic, make it difficult to judge the success of films. Going back to 2019, where it’s a bit easier to judge, the top ten films included two animated successes, Toy Story 4 and Frozen II. An additional two were in the top twenty, How to Train Your Dragon: The Hidden World and The Secret Life of Pets 2. Animated films did not make up 20% of all films released, but that’s the portion of the top twenty they occupied.

I followed up that entry with one that found additional evidence that animated features were doing well, including the fact that Ice Age: The Meltdown was, though not the top box-office film of 2006, the most profitable film of that year.

So many developments have occurred in the world of feature animation since that first post that I decided to write an update.

The neighborhood is getting crowded

To some extent today’s update was inspired by a recent online post concerning new competition for Disney, which had absorbed Pixar and easily led the box-office race for years, with Dreamworks a second-run. Current developments led Alexandra Canal to point out some interesting figures. In 2022, Disney’s box-office total was $1.93 billion in ticket sales, for 26% of market share. Universal, number two, generated $1.64 million, for 22%, and Sony’s box-office coming in at a mere $834.8 million, or 11%. But things are changing. Other studios’ investments in building animation wings have started to challenge Disney’s dominance of the market for these films.

So far in 2023, as of July 1, Universal has The Super Mario Bros. (released April 5) at number one on the top-grossing list and over $1.3 billion worldwide. Sony has Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse (June 2) at number four and approaching $620 million worldwide. By contrast, Disney has had two flops in recent memory: Lightyear (which I found mildly entertaining but not what I expect from Pixar) under-performed last summer, and Disney’s own Strange World (November 23) ended up with less than $74 million. Disney’s film in the top ten is the live-action version of The Little Mermaid (May 26), at number five with just over half a billion.

It will probably take several years for the long-term effects of streaming and the theatrical distribution recovery (if any) will have on Disney’s dominance. Still, it seems that the other Hollywood studios’ move toward creating their own animated departments is succeeding to some extent. The trend toward a greater variety of animated films may last.

Best Animated Feature or Best Picture? Which will win?

For this entry I have picked a rather arbitrary method of comparing quality animated films with quality live-action ones. I’m going to look at the Best Animated Films Oscar winners and nominees in comparison to the Best Picture ones.

Every now and then someone points out that such excellent animated films are now being turned out regularly that it would be logical to nominate the best of them for Oscars in the Best Picture category. There has never been a rule against such a crossover. So far it has only happened three times: Beauty and the Beast (1991, before the Best Animated Feature category existed), Up (2009), and Toy Story 3 (2010). None won, though they did take home Oscars in their own race. Other categories are technically open to animated films. Seven have been nominated for best screenplay, all Pixar films, with none winning.

A somewhat comparable situation has happened in the Foreign Language category. We tend to forget, but ten foreign-language films have been nominated for Best Picture: Grand Illusion (1938), Z (1969), The Emigrants (1972), Cries and Whispers (1973), Il Postino (1975), Life Is Beautiful (1998), Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), Babel and Letters from Iwo Jima (both 2006), Amour (2012), Roma (2018), Parasite (2019), Minari (2020), Drive My Car (2021), and All Quiet on the Western Front (2022). Oddly enough (maybe there was some change of rules), starting in 1998 with Life Is Beautiful, six of these also got nominated for Best Foreign Language film: Life Is Beautiful, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, Amour, Roma, Parasite, Drive My Car, and All Quiet on the Western Front. All of them won in the Foreign-Language category, but only one, Parasite, won Best Picture as well. Presumably if a film was good enough to be nominated for best picture, it certainly would be good enough to win the Foreign-Language Oscar.

The same was true for animated films. Up and Toy Story 3 were nominated in both categories and won just the animation awards. (The animated feature award was started in 2002 for films released in 2001, so Beauty and the Beast could not do the same.)

Now we turn to another way of looking at the Best Picture and Best Animated Feature categories. If one is on Facebook, as I am, or, presumably, other social-media sites, as I am not, in many years one reads many vociferous complaints about the quality of the Best Picture winners. Since online people love lists, there are plenty of people weighing in on the ten worst films to have won that prize. These ten are usually fairly recent, since these online commentators usually don’t watch older films. Occasionally someone mentions Cavalcade (1933), but those are the real cinephiles.

I’m going to compare the Best Picture and Animated Feature nominees and winners, starting in 2002, when the latter category originated (for films released the previous year). The questions are, are some of the animated nominees and/or winners better than the live-action films that won Best Picture in the same year, and if so, how often does this happen? This is not, of course, to say that the Oscars are a true reflection of the cream of the crop, especially in the live-action Best Picture category. The best animated films (at least, English-language) tend to rise to the surface in terms of nominations because there simply are so few of them in comparison.

Logically, having chosen the Oscars as a means of comparison, I should compare all the excellent nominated animated films with all the excellent nominated live-action films. After all, the film or films deserving to win seldom do so. Maybe some of them are better than the animation winner. I’m not going to include all the nominees, because first, it would make this entry more lengthy and convoluted than it already is. Second, I haven’t seen all the nominees in either category, though I have seen a higher portion of the animated ones. Still, I shall mention in parentheses live-action titles that in my opinion were more deserving of the Best Picture Oscar than the actual winner.

I have seen all the animated winners and all of the live-action ones apart from Crash. Thanks to the reviewers and friends who warned me off the latter. (To be honest, I turned Chicago off about twenty minutes in.)

The Face-off

So let’s go year by year and see how the Best Picture fares against the Best Animated Feature–or in some cases multiple nominees in that category.

Going by release years rather than the years when the awards were given, we start with 2001. A Beautiful Mind was the winner. I’ve actually seen it on a list of worst-ever Best Pictures, but I think it’s a fairly good film. Shrek, the animated champ that year, was much admired, but I was disappointed by it. Monsters, Inc., however, was up against Shrek, and in my opinion deserved to win. It’s arguably better than A Beautiful Mind.

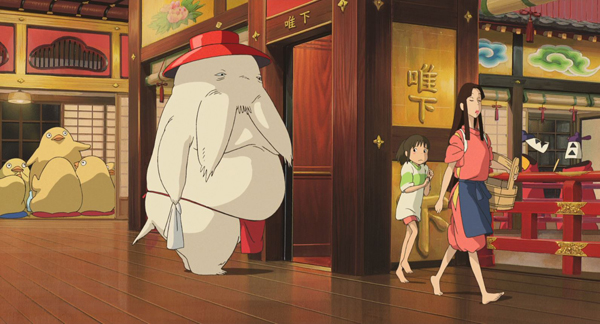

There’s no contest for 2002. Even today, awarding a foreign-language film the best-animated prize is nearly impossible–or indeed, a non-Hollywood one. (Non-American winners come from the UK and Australia.) To be sure, many Academy voters probably saw the dubbed version of Spirited Away. Nevertheless, the obvious sheer brilliance of Miyazaki’s film (above) won the day. Indeed, with Godard gone, Miyazaki may be our greatest living filmmaker–though no one can see enough films from around the world to make such a judgment.

2002 was the first year in which there were enough eligible animated features that five rather than three films were nominated, something that wouldn’t happen again until 2009. Nevertheless, the animated competition was pretty lackluster: Ice Age, Lilo and Stitch, Spirit: Stallion of the Cimarron, and Treasure Planet. Spirited Away, arguably one of the greatest films of our current century, is miles beyond Chicago. If there is any evidence that the animated films can top the live-action ones, this year provided it.

Unlike our Supreme Court and other federal judges, I shall recuse myself from judging the 2003 contest. Having written a book on the subject of The Lord of the Rings film franchise and having had extraordinarily generous cooperation from the filmmakers, I can’t really be objective. Quite possibly Finding Nemo is better than The Return of the King,

2004 saw a return to only three animated features–a situation that would last until 2007. Three nominations were enough, however, since The Incredibles was up against Crash, a film high on many lists of the worst-ever winners. I doubt many would dispute my claim that The Incredibles won this face-off by a mile. (Again, I haven’t seen Crash or some of the other nominees, but I very much suspect that Spielberg’s Munich should have won.)

I am less confident in calling the 2005 winner. Million Dollar Baby is a decent film, though I wish Eastwood had not injected the heavy-handed point that Maggie wins Frankie’s heart because she’s a substitute for the daughter who has willfully disappeared from his life. Frankie losing his prejudice against training women boxers would be more powerful if it was simply based on her skill and determination. Still, I hesitate to say that the animation winner, Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of the Were-Rabbit (above), is better. (One of the English-language imports that have won.) I am a huge Aardman fan, but Wallace and Gromit work better in the shorts (especially the sublime The Wrong Trousers). Of the other two nominees in the category, Tim Burton’s Corpse Bride isn’t a contender, but one could make a case for Howl’s Moving Castle (Miyazaki again) as the film of the year.

Scorsese’s The Departed is a more complicated case in the 2006 face-off. Those of us who know the Hong Kong film it’s based on, Andrew Lau and Alan Mak’s Internal Affairs (2002), know how very much Scorsese used from the original. Plus who can forgive that final shot? Being a George Miller fan, I was quite disappointed by Happy Feet (the second English-language import to win). Rather bland, I thought, and certainly no Babe: Pig in the City (1998). I think Cars should have won best animated feature, and it outdoes The Departed as well. For some reason a lot of people don’t like Cars all that much compared to other Pixar films, which I don’t understand. Certainly Cars 2 is awful and Cars 3 pleasant enough. But the original is terrific.

The 2007 contest must be a draw. It’s hard to choose between the Coen Brothers’ No Country for Old Men and Rataouille, the animated winner. (If Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood has won best picture, I would give it the edge over the Pixar film. It’s another of the great films of the current century.)

It’s safer to say that in 2008 WALL-E tops Danny Boyle and Loveleen Tandan’s Slumdog Millionaire. The first half hour of WALL-E, set on Earth, is perhaps the best thing Pixar has done. It falls apart a bit once the hero and Eve get onto the giant spaceship to which humanity has fled once the Earth became uninhabitable. It turns into a prolonged chase that isn’t nearly as interesting as the incredibly clever exploration of the detritus of civilization that WALL-E diligently searches through in that first half-hour. Still, for that half-hour, I give it the edge against Slumdog Millionaire.

In 2009, there were for the second time five animated nominees. The category would return to three in 2010, but thereafter there have always been five. Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker was probably one of the stronger films to win best picture in the period I’m covering. Still, can it really be said to be better than both Pixar’s Up (the winner) and Wes Anderson’s Fantastic Mr. Fox? And possibly Coraline or The Secret of Kells, Laika’s and Cartoon Saloon’s first entries into the fray respectively. (One benefit of writing this entry is that I watched for the first time all three of Tomm Moore’s lovely nominated Irish films, including The Song of the Sea and Wolfwalkers.)

My case is pretty strong in 2010. With only three nominees, the animated winner, Toy Story 3, easily tops Tom Hooper’s The King’s Speech. (We should remember we’re in the period when Harvey Weinstein was bludgeoning his company’s films into the winner’s circle.) Some would say How to Train Your Dragon would as well. (Among the live-action nominees, I would vote for Inglourious Basterds, but it would be a miracle if the Academy members chose such a film.)

With 2011 we reach another case where the best-picture winner is widely decried as among the worst to pick up the trophy: Michel Hazanavicius’ The Artist. The line-up of animated entries was pretty weak apart from Rango, directed by, of all people, Gore Verbinski. This brilliant outlier within the animation industry (produced by Nickelodeon), is a sort of cross between Chinatown and Once upon a Time in the West. That’s Rango with the villainous-tortoise mayor, above; the latter is a combination of Noah Cross in Chinatown and Mr. Choo-choo in Once upon a Time in the West.

Rango seems to have largely slipped from people’s memories, perhaps partly because it’s not a Disney or Pixar film that you buy on disc for your kids and have around forever. I don’t know what kids would make of Rango, but it’s definitely more aimed at adults. And hilariously imaginative.

2012 was a banner year for great animated films. The Oscar winner, Pixar’s Brave, was the first of six films in a row from Pixar and Disney, both at that point under the leadership of John Lasseter. I don’t find Brave among the best of these, but it’s OK and it no doubt benefited from all the fuss about it having Pixar’s first female protagonist. For me, there were no fewer than three wonderful nominees that were better: Laika’s Paranorman, Aardman’s The Pirates!: In an Adventure with Scientists! (the British title, changed to the much more boring The Pirates! Band of Misfits for North American release), and Disney’s Wreck-it Ralph. All three offer a flood of clever jokes and original concepts that could only be understood by adults. In Wreck-It-Ralph there’s the AA-style meeting of video-game villains that Ralph attends (top). Or in The Pirates!, the Pirate of the Year awards ceremony that puts the rival contestants in split-screen à la the Oscars show (second from top).

Any of them beats the “best picture,” Ben Affleck’s Argo. Remember that? (I haven’t seen all its live-action rivals, but Lincoln and Amour would have been creditable winners.)

Steve McQueen’s 12 Years a Slave fully deserved to win Best Picture. There’s certainly nothing to rival it in the somewhat set of nominations in the animation category. I did not find the winner, Disney’s Frozen, particularly interesting. It seems to be geared to appeal to small children. Miyazaki’s The Wind Rises was the only plausible nominee to go up against Sir Steve’s film, but I’m not going to make that argument. (It’s a real pity that Gravity was in the competition this year, since it truly is a great film and also deserved to win.)

Moving on to 2014, the live-action winner was Iñárritu’s Birdman or (The Unexpected Virtue of Innocence). The list of animated nominees was not as strong as some years, but I think Birdman is overrated, and Disney’s Big Hero 6 tops it. (I’ve only seen some of the live-action nominees, but The Grand Budapest Hotel and some of the others were pretty strong contenders.)

In 2015 the winners in the two categories were Tom McCarthy’s Spotlight and Pixar’s Inside Out. I don’t really have a preference. (Here’s another case, similar to Inglourious Basterds, of a marvelous but violent, over-the-top masterpiece deserved Best Picture: Mad Max: Fury Road. It pretty much swept the technical awards to end up with six, but Spotlight won only two–picture and screenplay. Go figure.)

I remember watching Barry Jenkins’ Moonlight in a theater in 2016. I sat there thinking that this film was made by a talented young man who someday might win an Oscar. To me, his The Underground Railroad was a more impressive achievement and deserved a slew of Emmys. Three excellent animated films were nominated in 2016: Disney’s Zootopia, Laika’s Kubo and the Two Strings (bottom), and Disney’s Moana. I was convinced that Kubo would finally win Laika it’s first, well-deserved Oscar. Zootopia won over what I think is a slightly better film, Moana, but one can’t really complain in this case. (My preferences for Best Picture would have been Arrival and La La Land.)

The situation was reversed in 2017. Much though I like many of Guillermo del Tor’s films, I’d have to give Pixar’s Coco the edge over The Shape of Water (talk about a Mexican stand-off!). (The true masterpieces among the nominees that year were Nolan’s Dunkirk and Paul Thomas Anderson’s Phantom Thread. At least, as so many of my friends have said, Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri didn’t win.)

Now we come to the notorious year of 2018, when Peter Farrelly’s (!) Green Book won best picture against competition that included Spike Lee’s BlacKkKlansman and Curaón’s Roma. This incomprehensible choice throws an even greater light on the high quality of the animated race that year. Three masterpieces were among the five nominees: Sony’s Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse, which won, Wes Anderson’s Isle of Dogs (above), and Disney’s Ralph Breaks the Internet. Any one of these rolls right over Green Book. Incredibles 2 is pretty good as well. I enoyed the fifth nominee, Mamoru Hosoda’s Mirai, but it hadn’t a chance against these three.

2019 is easy. Bong Joon Ho’s Parasite beats everything, even Pixar’s Toy Story 4. Probably a lot of people agreed with my assessment that the franchise was showing a bit of wear and tear, though not nearly as much as last year’s Lightyear. (Again, it’s a pity that two other masterpieces nominated that year couldn’t also win: Little Women and Once upon a Time in Hollywood.)

For 2020, when theater-going was difficult if not impossible, studios delayed many films or sent them straight to streaming. The result was a somewhat uninspired lineup of animated nominees. Soul almost inevitably won. I must admit that I preferred Pixar’s films as they were until recently–adventures of various sorts, whether involving actual superheroes, groups of toys, or an old man flying his house to South America to learn how to be sociable again. These had psychological depth, but they didn’t make it explicit by making emotions into characters or sending them to heaven. So Nomadland comes out ahead this time. (I would have preferred two other nominees, The Father or The Trial of the Chicago 7.)

In 2021 I found Sian Heder’s Coda as heartwarming as anyone, but Oscars are purportedly for picking great films that we assume till be watched in the future as classics. Not that they get it right very often, but, well, Oscar-bait ain’t what it used to be. The Danish animated documentary Flee leaves us with a tear in the eye as well, but the Academy stuck to its long habit of rewarding Pixar and/or Disney films and made Encanto its top animated film. This film had many good moments, but it annoyed me every time it got into a lively scene. Suddenly the characters (and virtual camera) started zipping about through the settings. Those settings were gorgeous, but we didn’t get a chance to look at them. Just compare it with Moana, which also had scenery worth lingering over while still managing to drip with exuberance. (For the live-action champ, I would have gone for Nightmare Alley, The Power of the Dog, or West Side Story. It was a pretty good year.)

There was, however, one animated feature nominated that year: the unmissable The Mitchells vs. the Machines–though many may have missed it when during the pandemic it skipped theatrical and went straight to Netflix. It was produced by Phil Lord and Chris Miller, who also did Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse for Sony Pictures Animation, and although a very different film, it has all the energy, imagination, and craziness of that film. It also plays out the potentially apocalyptic rebellion against humans by AI and the robots run by it. The premise is that an angry computing system being replaced by a new generation sends robots to put all humans in plastic cubes and fire them into space–including its own inventor. The dysfunctional Mitchells are humanity’s only hope. The funniest and most telling scene is when they stop at a mall and all the products in the stores, which have chips installed holding a kill order to destroy the family, start attacking them. This culminates in a bunch of Furbies going after them, led by the world’s largest Furby (above).

What happened in the 2022 category is sort of like what happened in 2002, when Spirited Away won. An outlier from outside the traditional Hollywood studio structure (Netflix) was nominated among a somewhat weak group of animated films and won the day. I settled down to watch the broadcast of the ceremony wondering if Academy members would recognize what a remarkable film Guillermo Del Toro’s Pinocchio is and not just reflexively vote for the Pixar film. That was Turning Red, which got a lot of attention for daring to show a teenager hitting puberty and experiencing her first period. I didn’t think it was a very good film and confirmed my sense that Pixar has declined in recent years. It’s probably better than The Good Dinosaur and now Lightyear, which is not saying much. (Carolyn Giardina’s recent “Elemental Steps into the Ring in Major Box Office Test for Pixar,” astutely sums up reasons for the aesthetic decline of Pixar–and, one might add Disney Animation.)

I know a lot of people for some reason are enthralled by Everything, Everywhere, All at Once, which won the 2022 Best Picture. I found it mildly entertaining but at least it gave Michelle Yeoh a career win for Best Actress. Pinocchio is miles beyond it. (Everything won against a slew of superior films. In alphabetical order: The Banshees of Inisherin, The Fabelsmans, Tár, and Women Talking.)

Totting up the live-action vs. animation winners in this face-off, we find one recusal, one draw, five decisions in favor of the live-action winners and fourteen for the animated winner or one or more of the animated nominees. As I mentioned at the start, the figures would be quite different if I had compared all the Oscar-worthy animation awards with all the Oscar-worthy Best Picture nominees. Still, in general this comparison may suggest that animated films are unfairly treated as one of the minor categories that people don’t pay much attention to.

I’m not suggesting that the Academy change their categories or rules. There’s probably no way to boost the prestige of the Animated Feature nominees.

The point here has simply been to add some evidence to my claim that a higher percentage of animated films tend to be excellent in a way that compares favorably with the live-action films nominated in the more prestigious category. Despite this, animated films are simply not taken seriously by most people, inclined cinephiles. They are still viewed as children’s fare, despite the successful appeal to adults built into many of the titles I’ve singled out here. They are also mostly comic to some extent and often involve fantasy, while Oscar bait leans toward drama and, with rare exceptions, away from fantasy/science fiction.

The conclusion is that if you think, for whatever reason, that live-action Oscar winners and films in general have declined in the past few decades, check out some ‘toons.

Kubo and the Two Strings (2016).