Archive for the 'Narrative: Suspense' Category

Can the science of mirror neurons explain the power of camera movement? A guest post by Malcolm Turvey

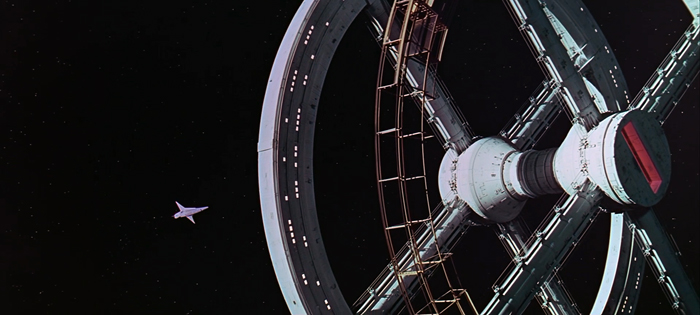

2001: A Space Odyssey (1968).

DB here:

Over the years we’ve brought you several guest posts from friends whose research we admire. The list includes Matthew Bernstein, Kelley Conway, Leslie Midkiff DeBauche, Eric Dienstfrey, Rory Kelly, Tim Smith, Amanda McQueen, Jim Udden, David Vanden Bossche, and our regular collaborator Jeff Smith (most recently, on Once Upon a Time in Hollywood…).

Today our guest is Malcolm Turvey, Sol Gittleman Professor in Film and Media Studies at Tufts University. Malcolm has long been a voice calling for rigorous humanistic study of film. His books include Doubting Vision: Film and the Revelationist Tradition (2008) and The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s (2011). Just this year he published Play Time: Jacques Tati and Comedic Modernism. (More on this in a future blog entry.) Among his many specialties, Malcolm applies the philosophical tools of conceptual analysis to problems of film criticism and theory.

My previous entry discussed some ways psychological research has helped me understand how films work, and I touched on the recent efforts to invoke mirror neurons to explain some effects that movies have on us. Today Malcolm takes a deeper plunge into this line of thinking, and the result is an exciting instance of how careful intellectual debate can be carried out in film studies. It’s also a cautionary tale about relying on scientific research to explain the appeal of artworks. A more extensive version of this piece is slated for publication in Projections: The Journal of Movies and Mind.

In Alfred Hitchcock’s Notorious (1946), Alex Sebastian (Claude Rains) is one of a group of Nazis who have relocated to Brazil after WWII. He has unwittingly married Alicia Hubermann (Ingrid Bergman), an undercover American agent seeking his circle. When Alicia learns that their scheme somehow involves the wine bottles locked in her husband’s cellar, she decides to procure the key so that she and her handler (and lover), Devlin (Cary Grant), can investigate.

Her opportunity comes in a characteristically suspenseful scene. Alicia nervously contemplates her husband’s keychain lying on a bureau as he finishes taking a shower nearby. She bravely steals the key and barely escapes discovery as Alex emerges from the bathroom. But what is the source of the scene’s suspense?

In a provocative new book titled The Empathic Screen, Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra claim the suspense should be attributed primarily to a brief, “human-like” camera movement toward the keys that occurs as Alicia looks at them. Moreover, they draw on neuroscience, specifically the science of mirror neurons, to make their case.

Here is the scene.

Are Gallese and Guerra right about the role played by the camera movement? For reasons I’ll give shortly, I doubt they are. More importantly, I question whether the neuroscientific evidence they lean on supports their case. This may seem like nit-picking, but I think their appeal to neuroscience contains valuable lessons about how students of film should–and shouldn’t–engage with scientific research.

Science and film studies

Readers of this blog are likely familiar with the idea that science has an important role to play in film studies. Since 1985, David Bordwell has drawn on contemporary cognitive psychology to answer questions about perceiving and understanding narrative films, thereby launching a new paradigm in film theory that has come to be known as cognitivism. In his previous entry, David offers an overview of his current thinking about cognition and movies.

Cognitivism has generated much heat in academic film studies. But at its heart is what should be an uncontroversial principle: that those who wish to understand the perceptual, cognitive, and affective capacities with which we engage with art should turn to the work of those who know something about these capacities, namely, the psychologists and other scientists who study them empirically and propose theories about them in light of their findings.

This is because our pre-scientific, “folk” understanding of our psychological capacities is usually non-existent or flawed. It is, for instance, hard to explain why we see still frames as moving images when they are projected above a certain speed merely by reflecting on our “phenomenological” experience of watching movies.

Perceptual psychologists, however, have studied this phenomenon empirically and have proposed explanations for it, such as critical flicker fusion frequency and the phi phenomenon (although like all scientific explanations, these are open to revision and even falsification in the light of new evidence and theorizing). The same is true of other features of our experience of films, and cognitive film scholars have built on David’s work by drawing on contemporary scientific knowledge of emotion, music, moral psychology and much else.

This does not mean that film studies is or should be a science. As David and Kristin’s blog entries repeatedly demonstrate, many of the things we want to know about cinema and the other arts can be discovered through non-scientific, humanistic methods such as analyzing films and researching the context in which they were made. In other words, our methods should be tailored to the questions we ask. Cognitivism argues that some important questions about the cinema can be answered by science, not that all or even most can.

The deceptive authority of Science

That said, I worry that engaging with science in a responsible manner is much more difficult than some of my cognitivist colleagues acknowledge. That difficulty is due, in part, to the “authority” of science.

Because of this authority, many non-scientists might assume that science is more settled than it often is, especially in a human science such as psychology. Those of us who aren’t scientists could be tempted to think that a scientific argument must be true because, well, there are scientific data to support it.

But as the recent “repligate” controversy in psychology and elsewhere shows, just because a scientist can present evidence for their views does not make them true. Data can be unreliable and the conclusions drawn from themunwarranted, as we are witnessing on a daily basis during the coronavirus pandemic.

Although there are occasional scientific revolutions, if science makes progress, something that some ph0ilosophers have questioned, it usually does so incrementally through trial and error, and there is much more failure than success. Those of us who don’t participate in this dialectical process might be apt to forget the provisional, tenuous status of much scientific research and accord it more certainty than it warrants.

Mirror neurons: The controversy

This has happened, I believe, with mirror neurons, a new scientific paradigm that has emerged over the past few decades and that some film scholars have started to draw on to explain some of our responses to films, such as empathizing with characters.

Mirror neurons are neurons that fire both when a subject executes a movement and when the subject sees the same movement executed by another. They were first discovered in the early 1990s in the motor cortex of pigtail macaque monkeys by a group of neuroscientists in Parma, Italy, and they have been invoked to explain a wide array of human behaviors such as language, imitation, empathy, art appreciation, and autism.

This is because mirror neurons appear to provide an explanation for how macaques and human beings understand the actions of their conspecifics. Researchers speculate that, if the same neurons fire when a subject reaches for an object, say food, and when the subject observes another agent reaching for food, the subject must be simulating the observed reaching-for-food action in its brain without actually executing it.

By simulating the observed reaching-for-food movement in its neurons, the subject knows the meaning of the movement–reaching for food–because it has performed the movement itself in the past, and attributes that meaning to the action being executed by the agent it observes, thereby comprehending it. As Marco Iacoboni puts it in a popular treatment of the subject:

To see . . . athletes perform is to perform ourselves. Some of the same neurons that fire when we watch a player catch a ball also fire when we catch a ball ourselves. It is as if by watching, we are also playing the game. We understand the players’ actions because we have a template in our brains for that action, a template based on our own movements.

Yet within neuroscience, mirror-neuron explanations of human behavior are controversial and contested, and no less an authority than Steven Pinker has referred to them as “an extraordinary bubble of hype.” Meanwhile, cognitive scientist Gregory Hickock has written an exhaustive book on the subject with a title that says it all: The Myth of Mirror Neurons.

Film scholars who appeal to the mirror neuron paradigm have not engaged with criticisms of it. Hence, their neural explanations of cinema appear to be supported by a scientific consensus that is in fact lacking, and they may not be drawing on the best current science.

For example, the philosopher of film Dan Shaw maintains that “The discovery of the existence and emotive function of mirror neurons confirms that we simulate other people’s emotions in a variety of ways, even in cinematic contexts,” and he views mirror neurons as the neurophysiological foundation for cinematic empathy. Notice how Shaw makes a strong claim here by using the word “confirms.”

Yet, although Shaw writes that “it is a cliché that monkeys are good imitators,” Pinker suggests that macaques do not imitate and they have “no discernible trace of empathy.” This is despite their possession of mirror neurons. Thus, the mere presence of mirror neurons or a mirror system in a creature cannot be evidence, in and of itself, for the creature’s capacity for empathy. While it might provide one of the neural foundations for empathy or contribute to its realization in some way, much more is needed than mirror neurons or a mirror system for a creature to empathize. Their presence certainly doesn’t “confirm” that we empathize with characters in film.

It is, however, a different, equally pernicious consequence of the authority of science that I wish to highlight here using mirror neurons. The apparent authority of a scientific paradigm can lead scholars to cherry-pick and mischaracterize our artistic practices in order to fit the science. This brings us back to Gallese, one of the co-discoverers of mirror neurons, and Guerra, and their claims about camera movement.

Camera movement and mirror neurons

Gallese and Guerra argue that our mirror neurons not only simulate the emotions of film characters but also the anthropomorphic movements of the camera recording them.

We maintain that the functional mechanism of embodied simulation expressed by the activation of the diverse forms of resonance or neural mirroring discovered in the human brain play an important role in our experience as spectators. Our ability to share attitudes, sensations, and emotions with the actors, and also with the mechanical movements of a camera simulating a human presence, stems from embodied bases that can contribute to clarifying the corporeal representation of the filmic experience. [My emphasis.]

In support of their contention that the mirror neurons of film viewers simulate human-like camera movements, Gallese and Guerra cite an experiment they participated in. This measured the motor cortex activation of nineteen subjects who were shown short video clips of a person grasping an object. The action was filmed in four different ways: with a still camera, a zoom, a dolly, and a Steadicam.

“The results were positive,” Gallese and Guerra conclude. “Shortening the distance between the participant and the scene by moving the camera closer to the actor or actress resulted in a stronger activation of the motor simulation mechanism expressed by the mirror neurons” relative to the clips shot with a still camera. Moreover, the subjects rated those scenes filmed with a moving camera as more “involving.”

Gallese and Guerra rely on this single experiment to make a bold argument about the role of camera movement in the design of films and its effect on the experience of film viewers. “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” This is because “the sense of participation in the camera action is undoubtedly enhanced by the fact that its behavior is interpreted by both filmmakers and spectators according to evident and automatic anthropomorphological analogies.”

When scenes are recorded with human-like camera movements, they seem to be suggesting, our mirror neurons simulate these camera movements because they are like actions we ourselves have performed. This in turn results in a feeling of “involvement” or “participation” in the scene on the part of the film spectator.

There is much one could question about this experiment and the conclusions Gallese and Guerra draw from it. For example, if it is camera movement that elicits mirror neuron simulation which in turn gives rise to a sense of immersion, viewers should feel involved in the camera movement, not the sceneit films. Indeed, what is depicted in the scene should be irrelevant to the viewer’s feeling of involvement if it is the camera movement that gives rise to this feeling by eliciting mirror neuron simulation.

Making the art fit the science

It is, however, the theory’s cherry-picking and mischaracterization of the artistic practice of cinema that most concern me here. According to this theory, as we have seen, “the involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.” The explanatory claim is that anthropomorphic camera movements, in other words those that resemble the human action of walking through space, elicit the mirror neuron simulation that gives rise to the viewer’s immersion in the film.

This is a strong claim, and if it were true it would have profound implications for both the study of film and filmmaking. It would mean that the more anthropomorphic camera movements that films contain, the more involving they would be for viewers. It would also mean that scenes filmed with human-like camera movements would be more involving than those shot with a still camera, and that scenes filmed with non-anthropomorphic camera movements would be less involving than those shot with anthropomorphic ones.

The latter is due to the mirror neuron simulation theory’s argument that we can only simulate movements we ourselves have performed. Hence, camera movements must be like ones we have executed ourselves in order for our mirror neurons to simulate them and produce the requisite sense of immersion.

Before assessing this claim, one question needs to be answered. What, exactly, is meant by involvement, participation and immersion? After all, there are a number of different kinds of possible involvement in a film.

We can be cognitively immersed in a film when we are intensely interested in the outcome of the plot or the revelations of a documentary. We can also be emotionally involved, as when we feel strong emotions toward the people or events depicted in the film. There is also aesthetic involvement when we pay close attention to and evaluate the design properties of a film. Then there’s physical or corporeal involvement, as when we are physically impacted by film techniques, such as the startle effect or bright lights and loud sounds. Doubtless there are other kinds of involvement too.

Gallese and Guerra never explicitly define what they mean by involvement, although on occasion they mention a “sensation of immersion in the spatiotemporal dimension of film.” In an earlier text they claimed that, by using the camera to mimic bodily movement, filmmakers make audiences feel that “we are inside the diegetic world, we experience the movie from a sensory-motor perspective and we behave ‘as if’ we were experiencing a real life situation.”

Personally, I am not sure what they mean by this. I have never felt immersed in the space and time of a film in the sense of somehow thinking or feeling that I am actually inside it. More importantly, it is not clear that the subjects of the experiment on which their theory is based meant spatiotemporal involvement as opposed to cognitive, emotive, aesthetic or other kinds of immersion when they rated how involved they felt in the clips they were shown. Thus, Gallese and Guerra’s experiment may provide no empirical evidence at all for their occasional references to spatiotemporal participation.

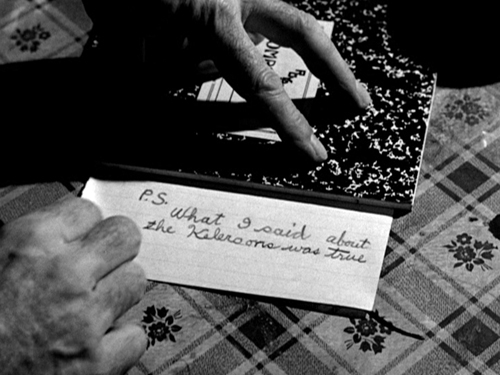

Confusingly, however, Gallese and Guerra sometimes seem to mean involvement in another sense of the term I have clarified. Regarding the brief camera movement toward the keychain in the scene from Notorious of Alicia stealing the key, they contend that “The problem that Hitchcock had to solve in this complex sequence was how to bring the spectator to an almost unbearable level of suspense.” They suggest that if Hitchcock had only used “classical editing” to film the scene, “our level of involvement would not be nearly so high.” They conclude: “This is why Hitchcock uses camera movement; it is this movement that creates the overpowering tension.”

Here, Gallese and Guerra seem to be using “involvement” in the emotive sense of feeling strong emotions such as “tension” and “suspense” about the characters and events in the scene, and they make no mention of “spatiotemporal immersion.” Either way, Gallese and Guerra provide no evidence at all that it is this brief camera movement “that creates the overpowering tension” in the scene. While the camera movement is certainly effective in drawing our attention to the keys and conveying Alicia’s anxious focus on them, I conjecture that there is a far more obvious, broadly “cognitive” reason for the scene’s suspense.

This is the possibility that Alicia, with whom we sympathize, will be caught stealing the key by her husband, who is a ruthless Nazi. Gallese and Guerra, however, discount such a narrative-based explanation for the suspense. They argue that “What strikes us most in films like Notorious is Hitchcock’s almost complete indifference to the plot” and that “the state of suspense in which we find ourselves at every viewing of Notorious has nothing whatsoever to do with the story.”

Yet, according to Hitchcock biographer Donald Spoto, Hitchcock himself wrote the outline for Notorious in late 1944, and then spent three weeks closeted with Ben Hecht writing the script, which was further modified in late-night script sessions with David O. Selznick before the project was eventually sold to RKO and filming began in October 1945. While it may be true that Hitchcock tended to see the plots of his films as merely a means to creating the arresting images and eliciting the strong emotions from his audiences that truly interested him, this does not mean he was “indifferent” to plot. He spent considerable time developing his scripts, and he was keen to work with talented screenwriters such as Hecht.

Nor is it plausible that the suspense in Notorious “has nothing whatsoever to do with the story.” Indeed, suspense is usually defined as a state of anxious uncertainty about what will happen in the story. If suspense has nothing to do with the story, it is hard to know what viewers feel suspense about. In the key-stealing scene in Notorious, it is surely the case that we are anxious about the possibility that Alicia will be caught in the act of stealing the key by her husband, an event that might happen in the narrative. If not, what else might the suspense be directed at?

Of course, the suspense in this scene is not solely dependent on the story but also on the scene’s style. But there are other stylistic techniques that play a much bigger role than the camera movement in the creation of suspense in the scene. For example, Alex’s shadow is visible on his partially open door as he towels himself dry and moves around the shower room.

This activity suggests that he has finished his shower and will emerge at any second. It starts to seem more likely that Alicia will be caught stealing the key, thereby intensifying the suspense. Meanwhile, other than delaying the scene’s outcome by a few seconds, it is not clear how the camera movement toward the keychain itself intensifies the scene’s suspense.

What is happening in the narrative and what is conveyed by other stylistic techniques, such as Alex’s shadow on the door and the music on the soundtrack, are the factors that intensify the scene’s tension. It seems highly unlikely that “our level of involvement would not be nearly so high” in the absence of the camera movement, in the sense of feeling tension and suspense about the scene’s outcome. Certainly, Gallese and Guerra provide no evidence to this effect.

Furthermore, as I’ve already mentioned, Gallese and Guerra’s theory at best explains our sense of involvement in the camera movement, not the scene it films. Recall that it is the camera movement itself that our mirror neurons simulate. It is unclear from their theory, therefore, how our putative feeling of immersion in the camera movement, if indeed we do feel immersed in it, can yield suspense about the concrete actions being filmed.

The category of human-like camera movement, if such a category is functionally relevant to cinema, comprises many fine-grained variations with different effects. Camera movements, for example, can elicit curiosity by making us wonder what they will reveal, as well as surprise when they come to rest on something unexpected. They can startle through their rapidity, as when swish pans suddenly disclose something off-screen, or they can uncover information at an agonizingly slow pace. They can reveal characters’ mental states through push-ins that show us that a character is concentrating hard on something, or they can hide information from us by moving away from it. They can also be aesthetically pleasing, as when we marvel at their gracefulness or the intricacy with which their movements are coordinated with those of the characters. None of these sources of the power of camera movement are explained by arguing that mirror neurons fire in response to anthropomorphic camera movements, if indeed they do.

Most broadly, as David points out in his previous entry, there is much that their theory cannot capture or explain about the power of framing. A static camera can evoke tremendous suspense, as David’s example from Hou’s Summer at Grandpa’s illustrates. It is hard to see what a tracking shot would add at such a moment.

The lessons of film history

Of course, just as damaging to the theory are the countless examples from the rich history of film of highly suspenseful, tension-filled, and in other ways involving scenes that lack anthropomorphic camera movements or that contain non-anthropomorphic ones.

In Notorious, right after the scene in which Alicia steals the key and is nearly caught by Alex, there is a crane shot in which the camera, having panned across the party in the hallway below from a first-floor landing, glides smoothly down toward Alicia talking to Alex and some guests in the hallway and ends in a close-up on her hand holding the key to the cellar.

Given that no human being could perform this movement, our mirror neurons shouldn’t be able to simulate it and produce a feeling of involvement in it. Yet, I hypothesize that, for most viewers, this camera movement creates a strong sense of cognitive, emotive, aesthetic, and other forms of engagement in the scene.

Among other things, this movement prompts us to wonder how Alicia is going to gain entry to the wine cellar without her husband noticing, thereby intensifying our sympathetic concern for her and our suspense about whether she will be caught. And in its overtness, it might make us think about Hitchcock’s choice of technique and the reasons behind it. For some, it might even induce that sense of “spatiotemporal immersion” that Gallese and Guerra mention given that it brings our perceptual perspective close to Alicia’s in the midst of the party, although I personally don’t feel this.

Either way, in this case, it cannot be due to mirror neuron simulation that we experience these forms of immersion. This is a non-anthropomorphic camera movement that human beings cannot execute themselves and therefore cannot simulate with their mirror neurons.

An example from a film by a different director would be the shots in 2001: A Space Odyssey (Stanley Kubrick, 1968) of Dr Floyd (William Sylvester)’s ship docking with a space station while Strauss’s Blue Danubewaltz plays on the soundtrack. (See image surmounting today’s entry.) For many, the smooth camera movements through space in this sequence evoke an intense sense of weightlessness, thereby creating a physical or corporeal form of involvement in the film. Yet, very few of us have moved in space or have experienced weightlessness, meaning that our mirror neurons should not be able to simulate these camera movements.

Then there are the copious examples of involving scenes that lack camera movement. Hitchcock’s oeuvre contains many, such as the infamous shower scene in Psycho (1960), which is devoid of camera movement during the 20 seconds or so in which the stabbing of Marion Crane takes place. Another example is the highly suspenseful sequence in Strangers on a Train (1951) in which Bruno (Robert Walker) drops Guy (Farley Granger)’s cigarette lighter down a drain while he is on his way to plant the lighter at the amusement park where he murdered Guy’s wife, Miriam (Kasey Rogers). Bruno wishes to implicate Guy in the murder, and Guy, who is a professional tennis player, has guessed Bruno’s plan and is trying to complete a tennis match in time to stop him from planting the lighter. Hitchcock cuts back and forth between the tennis match and Bruno’s efforts to reach down into the drain and retrieve the lighter.

Interestingly, while there is some camera movement at the beginning of the sequence, as the suspense builds, the camera movement lessens. Hitchcock relies largely on still shots of Bruno’s grimacing face as he reaches into the grate, his hand inside the grate and the lighter below it, and the faces of the referees and spectators at the tennis match. Only the shots of Guy and the other tennis player contain a little movement when the camera slightly reframes them as they move to hit the tennis ball.

This sequence is considered one of the most suspenseful (and thereby emotionally involving) in Hitchcock’s oeuvre, yet it defies Gallese and Guerra’s prediction that “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements.”

So does the astonishing sequence in William Wyler’s The Little Foxes (1941) in which Horace (Herbert Marshall), having told his estranged wife, Regina (Bette Davis), of his plans to leave his fortune to their daughter, begins experiencing painful symptoms of his heart disease as she tells him how much she despises him.

Horace reaches for his heart medication but knocks over the bottle and its contents and begs his wife to fetch another bottle of medication from upstairs. She, however, sits immobile while Horace, realizing she will not help him and wants him to die, staggers around her, clinging to the wall, and stumbles upstairs before collapsing on the staircase. An agonizing long take lasting about forty seconds shows Regina in medium shot sitting while her husband, who is out of focus, moves toward the stairs, and the shot is immobile except for slight reframings to keep Horace partly visible in the shot.

This is an intensely suspenseful, emotionally involving moment as we wonder whether Horace will reach his medication in time, or Regina or someone else will take action to help him. Yet, there is no anthropomorphic camera movement to elicit our sense of involvement in the scene. On the contrary, according to many critics, it is precisely the lack of camera movement that contributes to its emotional intensity. As André Bazin noted, “Nothing could better heighten the dramatic power of this scene than the absolute immobility of the camera,” in part because it mirrors and emphasizes the “criminal inaction” of Horace’s wife, Regina, who is hoping he will fail to reach his medication and die so that she can be rid of him and claim his fortune.

Gallese and Guerra could perhaps protest that I have misconstrued their theory. Although their claim that “The involvement of the average spectator [in a film] is directly proportional to the intensity of camera movements” seems to suggest that anthropomorphic camera movement is both a necessary and sufficient condition for occasioning involvement in a film, they might admit that immersion can be elicited in other ways. Instead, they could allow, human-like camera movement is merely a sufficient condition for involvement, not a necessary one. When it is present, we feel immersed in films, although this is not the only route to immersion.

However, it is not difficult to think of films containing lots of camera movement of both the anthropomorphic and non-anthropomorphic kinds that fail to engage viewers. An example is Kenneth Branagh’s Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1994), a film in which, as David Ansen of Newsweek put it, “The camera, and the actors, are always in a mad dash from here to there” (Ansen 1994). Nevertheless critics, who according to Gallese and Guerra “usually get much more excited” when camera movement is present, largely panned the film. (For what it’s worth, the film has a critics’ score of 38% and audience score of 49% on Rotten Tomatoes.) As Ansen put it:

What we get is Romanticism for short attention spans; a lavishly decorated horror movie with excellent elocution. [Branagh’s] strategy undermines itself–there’s a lot of sound and fury, but all the grand passions are indicated rather than felt. Watching the movie work itself into an operatic frenzy, one remains curiously detached: the grand gestures are there, but where’s the music? [My emphasis.]

Anthropomorphic camera movements do not, therefore, even appear to be a sufficient condition for immersion in a film, let alone a necessary one.

The way forward?

Gallese and Guerra, it seems to me, cherry-pick examples from films that appear to support their theory, and ignore obvious counterexamples even in the films they examine. They also mischaracterize scenes such as the one in which Alicia steals the keys, overlooking other evident sources of “involvement,” a term they fail to define consistently. They do, I suspect, because they are in thrall to the mirror neuron theory, and they therefore force the art to fit the theory.

None of this means that cognitivism should be abandoned and that film scholars shouldn’t be turning to science. Nor does it mean that camera movement doesn’t sometimes elicit and intensify emotions such as suspense. Moreover, neuroscience may well be able to shed light on some of the reasons why this happens, although many more experiments are needed to demonstrate this than the single one relied on by Gallese and Guerra.

But it does suggest that our engagement with the sciences should be governed by two principles.

First, when drawing on a scientific theory, it is crucial that film scholars also consider criticisms of it. Despite its authority, scientific research is typically provisional. Those of us in the humanities are not usually in a position to determine who is right in a scientific debate. So we should entertain criticisms of the scientific theory, in case they reveal pitfalls and other problems in applying the theory to cinema, or show the theory to be on far less secure ground than it may seem to be.

Second, those of us who are humanistic scholars of film should trust the knowledge we have gleaned from decades of work on the cinema. We shouldn’t simply accept conclusions that contradict this knowledge because they are supposedly scientific. We should not, in other words, be cowed by the authority of science. While we haven’t gotten everything right, most of us know from a little reflection, for example, that anthropomorphic camera movements aren’t required for greater “involvement” in a film.

Of course, we should allow for the possibility that our assumptions about these and other matters are incorrect. But given the weight of experience and knowledge behind them, the evidentiary bar should be set very high for their disconfirmation by empirical scientific research.

Thanks to Malcolm for all his work in preparing this version of his paper for our blog. Another essay of his along these lines is “Can Scientific Models of Theorizing Help Film Theory?” in Philosophy of Film: Introductory Texts and Readings, ed. Angela Curran and Tom Wartenberg (Blackwell, 2004), 21-32

Quotations from Vittorio Gallese and Michele Guerra’s Empathic Screen come from pp. 68, 111, 91, 94, and 114. Their claims about Notorious are found on pp. 53-58. The quotation from their earlier piece can be found in “Embodying Movies: Embodied Simulation and Film Studies,” Cinema: Journal of Philosophy and the Moving Image (2012) 3: 188.

The crucial experiment is documented in Katrin Heimann et al., “Moving Mirrors: A High-Density EEG Study Investigating the Effect of Camera Movements on Motor Cortex Activation during Action Observation,” The Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience (2014), 26,9: 2087-2101. with the discussion of involvement coming on p. 2097. The Marco Iacobobi citation comes from Mirroring People: The New Science of How We Connect with Others (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), 5.

Pinker’s remarks about mirror neurons and empathy are to be found in The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (Penguin, 2011), 577. The quotations from Dan Shaw are from “Mirror Neurons and Simulation Theory: A Neurophysiological Foundation for Cinematic Empathy,” in Current Controversies in Philosophy of Film, ed. Katherine Thomson-Jones (Routledge, 2016), 148, 151.

André Bazin discusses The Little Foxes in “William Wyler, or the Jansenist of Directing,” in Bazin at Work, ed. Bert Cardullo (Routledge, 1997) 3, 4. A blog entry here supplies further thoughts on the famous scene, which DB also analyzes in On the History of Film Style.

Donald Spoto discusses Hitchcock’s working methods in The Dark Side of Genius: The Life of Alfred Hitchcock (Da Capo, 1999; Centennial Edition), 284-287. David Ansen’s strictures on Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein appeared in “Monster Mush,” Newsweek (6 November 1994). More on Notorious is here.

During the current health crisis, Berghahn has made all issues of Projections: The Journal of Movies and Mind freely available. Several articles over the years debate issues around cognitive film theory and brain-based explanations of media effects. Malcolm Turvey has made many contributions to Projections; see especially his book review here.

2001: A Space Odyssey.

Cornell Woolrich: The overstrained imagination goes to the movies

DB here:

Can a storyteller be maladroit in using his or her medium and still be worth reading? Can a novelist with a clumsy style be a “good writer”? I’ve posed this question before on this site, and developed an argument about it at length in our book on Christopher Nolan.

Here’s a test case. These are real sentences from books by a novelist many consider one of the great crime/mystery writers of all time.

The knob felt cold and glibly elusive under his touch.

His face was an unbaked cruller of rage.

La Bruja lidded her eyes acquiescently.

I began treacherously touching up my hair via the mirror.

I crawled up onto the seat by means of my hands.

She could feel her chest beginning to constrict with infuriation.

This time the man got up off the bench, taking Quinn’s hand on his shoulder along with him.

Smoke suddenly speared from her nostrils in two malevolent columns. She looked like Satan. She looked like someone it was good to stay away from.

I was probably just a blurred bottle-green offside to her retinas.

“Made it,” Joan Bristol exhaled relievedly.

Seconds went by in packages of sixty.

The foaming laces that cascaded down her were transparent as haze against the light bearing directly on her from the room at her back. Her silhouette was that of a biped.

These passages, and many more like them, were published in books issued by major houses and still in print today. Can anything redeem them?

I’m currently trying to write a book on principles of popular narrative, with a focus on genres of crime and mystery. The project stems from arguments in Reinventing Hollywood and The Way Hollywood Tells It, but I wanted to broaden my inquiry to include theatre and literature as well. One section is about crime writers of the 1940s and 1950s. So naturally I had to include the widely renowned Cornell Woolrich.

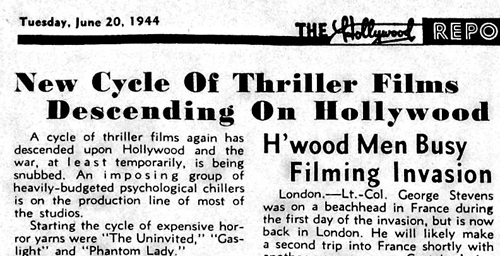

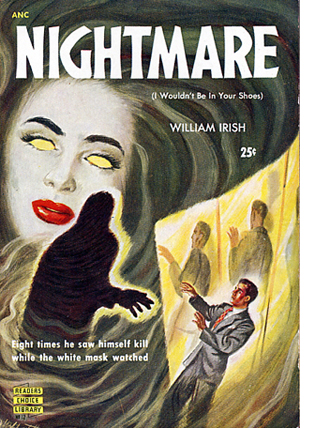

Despite his struggles with syntax and word choice, Woolrich has been a perennial source of popular storytelling. Nearly all the novels were brought to the screen soon after publication, and radio versions of the books and short stories were plentiful. By the 2010s his work had inspired over a hundred movies and television shows (directed by, among others, Hitchcock, Truffaut, Fassbinder, and Jacques Tourneur).

That research has led me two further questions. Are there aspects of his work that counterbalance howlers like those above? And what might have led to those stylistic problems? Readers looking for more direct and detailed studies of film versions of his work can go to Francis M. Nevins’ exhaustive biography and Thomas C. Renzi’s careful consideration of adaptations. (And my studies of The Chase, if you want.) Meanwhile, tackling the questions that interest me, I’ll touch on aspects of cinema a little bit. File this blog under Questions of Narrative Across Media.

Breathless reading

Cornell Woolrich is usually treated as an author with a uniquely haunting voice. Alcoholic and homosexual, he lived for decades in a hotel with his mother. After she died, he lost a leg to untreated gangrene. He dedicated one book to the typewriter on which he pounded out pulp stories and thriller novels, the most famous of them published in the years 1940-1948. His tales of suspense cultivated a hothouse morbidity. At his limit, Woolrich projects a paranoid vision of life without hope and death without dignity.

Cornell Woolrich is usually treated as an author with a uniquely haunting voice. Alcoholic and homosexual, he lived for decades in a hotel with his mother. After she died, he lost a leg to untreated gangrene. He dedicated one book to the typewriter on which he pounded out pulp stories and thriller novels, the most famous of them published in the years 1940-1948. His tales of suspense cultivated a hothouse morbidity. At his limit, Woolrich projects a paranoid vision of life without hope and death without dignity.

Despite his distinctive sensibility, Woolrich epitomizes some broader narrative strategies of his time. Like all popular writers, he inherited situations, techniques, and themes. To present a bleak, aching world of precarious love and doomed lives, he twisted those conventions into eccentric shapes that added to the Variorum of 1940s mystery storytelling.

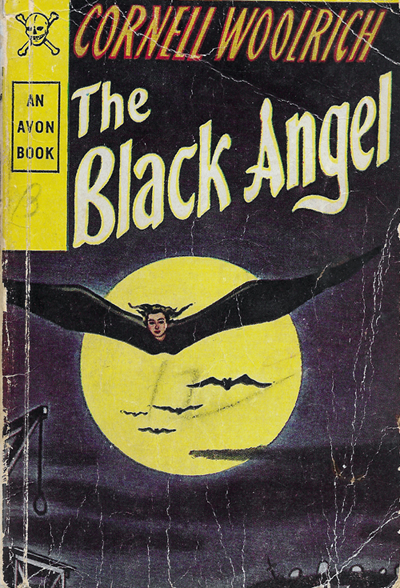

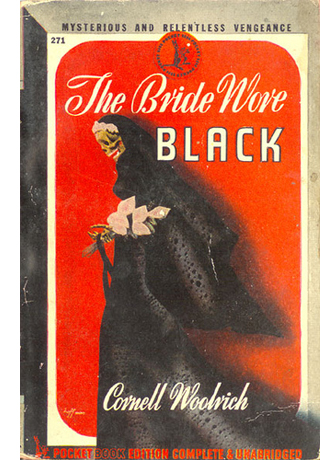

For him, one bout of amnesia isn’t enough, so The Black Curtain (1941) doubles it: the hero, already having forgotten his previous identity, is clobbered by some falling bricks and now can’t remember who he just was. The prototypical serial killer of the 1940s is a man, but The Bride Wore Black (1940) lets a woman stalk her victims. Most thriller novelists are content to put one woman in jeopardy per book, but Black Alibi (1942) lines up six. Alternatively, when a woman tries to save her husband from the chair by investigating four suspects, she’s plunged into danger every time she meets one (The Black Angel, 1943).

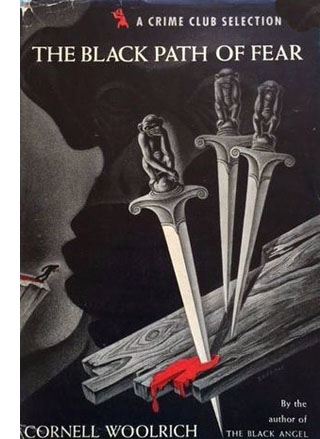

Woolrich’s plots flout police procedure (his cops are exceptionally willing to help suspects), and the authorities often flounder. Suspense thrillers usually invoke the supernatural only to dispel it, but in Night Has a Thousand Eyes (1945) the authorities fail to save a life because one old man really can predict the future. Not that amateur sleuths fare much better. The unheroic hero of The Black Path of Fear (1945) could hardly be more ineffective; he has to be rescued by the Havana police.

Sometimes the straining for originality snaps. Critics have long pointed out improbabilities and contradictions in the plots. Woolrich’s most devoted chronicler, Francis M. Nevins, warns of “chaotic ambiguities.” The chronology of Rendezvous in Black (1948) is impossible, while the climactic revelation of I Married a Dead Man (1948) is arguably incoherent. Convenient coincidences abound. Add to this a hypertrophied style that in every book slips into unabashed weirdness. (See above.)

Both the plot problems and the vagaries of language can partly be attributed to the rush of Woolrich’s production, his transport while hammering at his Remington Portable. Pulp author Steve Fisher recalled: “Sitting in that hotel room he wrote at night—continuing through until morning, or whenever the story was finally completed. He did not revise, polish, and I suspect did not even read the story over once it was committed to paper.” Although Woolrich was grateful to editors who corrected his hundreds of errors in spelling and punctuation, he apparently resisted efforts to touch up his prose. When an editor suggested a change to a single paragraph, he replied, “I knew you wouldn’t like it,” and left the publisher forever.

Both the plot problems and the vagaries of language can partly be attributed to the rush of Woolrich’s production, his transport while hammering at his Remington Portable. Pulp author Steve Fisher recalled: “Sitting in that hotel room he wrote at night—continuing through until morning, or whenever the story was finally completed. He did not revise, polish, and I suspect did not even read the story over once it was committed to paper.” Although Woolrich was grateful to editors who corrected his hundreds of errors in spelling and punctuation, he apparently resisted efforts to touch up his prose. When an editor suggested a change to a single paragraph, he replied, “I knew you wouldn’t like it,” and left the publisher forever.

Admiring readers excuse the faults by testifying that Woolrich’s evocation of tension keeps the pages turning. “Headlong suspense created by total, unrelieved anxiety,” noted Jacques Barzun. “Breathless reading is the sole pleasure.” Raymond Chandler called him the “best idea man” among his peers, but admitted, “You have to read him fast and not analyze too much; he’s too feverish.”

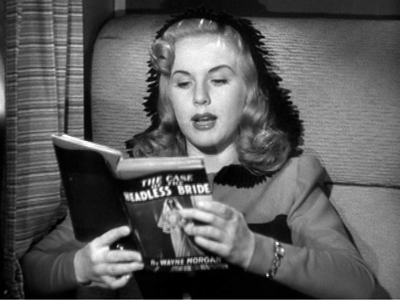

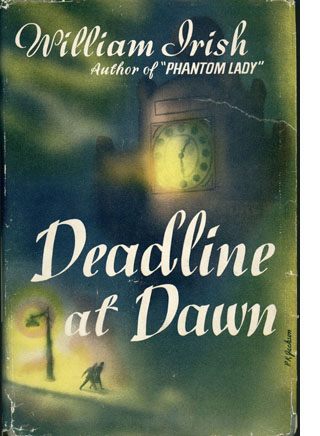

What keeps us reading? For one thing, the outré story situations. A couple hurrying to leave New York must clear the man of murder before the bus leaves (Deadline at Dawn, 1945). A killer stalks a city, but it’s not a human: it’s (apparently) a black jaguar escaped from a sideshow (Black Alibi). A mail-order bride seems unacquainted with things she wrote in her letters (Waltz into Darkness, 1947). Most famously, a man laid up in his apartment thinks he sees traces of a killing through a window across the courtyard (“Rear Window,” 1942).

Outrages to plausibility carry their own allure. What, we ask, might come of these wild mishaps? A train crash kills a husband and his pregnant wife. In the melée an abandoned woman, also pregnant, is mistaken for her and welcomed by the husband’s family. Conveniently, the in-laws have never seen the wife (I Married a Dead Man, 1948) A man accused of murder has an alibi, to be provided by a woman he met in a bar and took to a show. Trouble is, she’s vanished. All the witnesses deny she existed (Phantom Lady, 1942).

The development of the action also presents intriguing reversals. The man gulled by the fake mail-order bride falls in love with her. People who claim not to have seen the phantom lady wind up dead. The woman trying to exonerate her husband falls in love with the real killer and dreams about him even after he has killed himself.

The game is afoot

Woolrich’s novels tend to rely on two basic plot patterns, both based on the hunt. In one, amateurs try to solve a crime and move from suspect to suspect. Our viewpoint is mostly tied to the investigators. In the other pattern, a serial killer stalks a string of victims, and here Woolrich is more innovative. Normally, the serial-killer plot either concentrates on the killer’s viewpoint, as in the novels Hangover Square (1941) and In a Lonely Place (1947), or concentrates on the investigators, as in Ellery Queen’s Cat of Many Tails (1949). A few constantly bounce the spotlight among all the parties—killer, victims, and investigators—as in Fritz Lang’s film M (1931) and Philip MacDonald’s novel X v. Rex (1933).

Woolrich by contrast emphasizes the victims’ viewpoints. The killer might appear only at the beginning and end (Rendezvous in Black) or get introduced at intervals in brief, objective scenes (The Bride Wore Black). Less space is devoted to the investigators, although they gain prominence as the crimes pile up. Woolrich puts his energies into building waves of suspense as one target after the other confronts death.

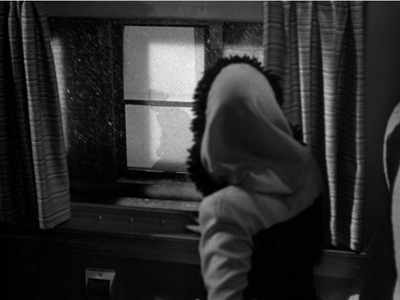

The shooting-gallery structure enables Woolrich to fulfill Mitchell Wilson’s demand that the thriller devotes its energies to showing what fear feels like. The 1940s interest in intense subjectivity of narration helps out here, and Woolrich sustains it in detailed description of victims’ reactions. In Black Alibi, Teresa is being stalked by an unseen figure.

The shooting-gallery structure enables Woolrich to fulfill Mitchell Wilson’s demand that the thriller devotes its energies to showing what fear feels like. The 1940s interest in intense subjectivity of narration helps out here, and Woolrich sustains it in detailed description of victims’ reactions. In Black Alibi, Teresa is being stalked by an unseen figure.

Something else now assailed her, again from without herself, but of a different sensory plane than hearing this time. A prickly sensation of being watched steadily from behind, of something coming stealthily but continuously after her, spread slowly like a contraction of the pores, first over the back of her neck, then up and down the entire length of her spine. She couldn’t shake it off, quell it. She knew eyes were upon her, something was treading with measured intent in her wake.

This passage is part of a ten-page account of the woman’s wary progress through a night street, rendered wholly from her viewpoint.

Woolrich’s other basic plot pattern, the investigation of a murder, plays up the role of fear as well. His amateur detectives, lacking official firepower, are constantly facing danger from the suspects they track.

Fright was like an icy gush of water flooding over them, as from burst pipe or water-main; like a numbing tide rapidly welling up over them from below. [Deadline at Dawn]

In both of his favored plot schemes, the plunges into characters’ minds and bodies help fill out a full-length novel. If you play down other lines of action (professional police investigation, killer’s mental life), you need to dwell on the reactions of the victims or amateur detectives.

Yet this very emphasis is one source of the stylistic howlers. In expanding his suspense scenes, Woolrich’s prose sometimes fails him. Needing to spin out lots of words evoking an ominous atmosphere, he’s tempted to pileups like this:

And the path that had led me to it through the night had been so black and so full of fear, and downgrade all the way, lower and lower, until at last it had arrived at this bottomless abyss, than which there was nothing lower. [The Black Path of Fear]

Such rodomontade carries the 1940s emphasis on subjectivity to paroxysmic limits.

He recruits other techniques of popular storytelling. They keep his action moving forward through time and plunging inward into the unfolding scenes. And some can help mask story problems.

By hinging his story around a search for a killer or a victim, Woolrich’s plots tend create a string of one-on-one encounters. Rather than disguising the episodic quality of these, he sharpens them by breaking the action into distinct blocks. Those blocks are presented as a checklist agenda, Woolrich’s equivalent to the closed circle of suspects we find in the classic weekend-house-party detective story.

The Black Angel is a simple instance.

After an initial cluster of five chapters presenting Kirk Murray sentenced to death, we follow Kirk’s wife Alberta as she seeks the true killer. Her efforts are given in five parallel chapters, each indented and tagged with a telephone number. One that Alberta finds scratched out in an address book is presented just that way in the chapter title: “Crescent 6-4824.” Because at the climax she returns to one of the four suspects, another title gets recycled: “Butterfield 9-8019 Again (And Hurry, Operator, Hurry!).”

A more complicated example of modularity is The Bride Wore Black. It’s broken into five parts, each titled with the name of a victim. Each part contains three sections.

“The Woman” shows the vengeful bride launching a new false identity. The part’s second section, titled with the victim’s name, shows how the murder is accomplished. A third section offering “Post-Mortem” on the victim consists of documents and conversations among the police. Viewpoints are rigidly channeled as well. Each “Woman” section is handled in objective description, while each victim section presents the targeted man as the center of consciousness. The book could be mapped out on a spreadsheet.

The modular layout and rigorous moving-spotlight narration risk choppiness, yielding something like a set of short stories. But the tidy exoskeleton can make the plot seem rigorously organized, even while it masks problems of time and causality. And the very arbitrariness of the pattern creates a sort of meta-curiosity. Like the teasing tables of contents in 1920s and 1930s detective fiction, a Wooolrich checklist of suspects or victims makes us aware of a larger rhythm. How will this pattern be filled out?

An overarching unity is provided as well by the demands of a deadline (another Hollywood-friendly feature). Thanks to this classic device, Woolrich can use time tags to trigger anticipation and yield a sense of shape. Long before the husband in Phantom Lady gets accused of the crime, the first chapter bears the title, “The Hundred and Fiftieth Day before the Execution,” effectively dooming him from the start. Deadline at Dawn replaces chapter titles with illustrated clock faces to impose a strict structure.

An overarching unity is provided as well by the demands of a deadline (another Hollywood-friendly feature). Thanks to this classic device, Woolrich can use time tags to trigger anticipation and yield a sense of shape. Long before the husband in Phantom Lady gets accused of the crime, the first chapter bears the title, “The Hundred and Fiftieth Day before the Execution,” effectively dooming him from the start. Deadline at Dawn replaces chapter titles with illustrated clock faces to impose a strict structure.

Facing a ticking clock wedded to a clear-cut pattern, we become sensitive to variations among the modules. The victim-centered chapters of The Bride contrast the personalities and private lives of the male victims, along with Julie’s resourceful methods of murder, and the last chapter breaks the three-part format by inserting a flashback dramatizing the fatal wedding. Rendezvous in Black revives the shooting-gallery structure of Black Angel and The Bride, adding a schedule that sets each murder on May 31st of different years. Within this regularity (“The First Rendezvous,” etc.), viewpoints multiply gradually so that the interplay of characters’ range of knowledge becomes richer.

The modular structure shows up in milder ways. Black Alibi tags its chapters with victims’ names and concentrates on one woman’s terror at a time, with each chapter concluding with an exchange among investigators. Deadline at Dawn and Phantom Lady alternate scenes between two characters embarked on parallel investigations. Night Has a Thousand Eyes, in some ways the most ambitious of the books, embeds the checklist within the police investigation. As teams of cops trace parallel leads, their efforts are crosscut with the target under threat, waiting with his daughter and a cop.

A simpler, more poignant, rhyme-and-variations effect is supplied by a prologue and epilogue in I Married a Dead Man. The prologue’s first-person narration, set off from the central chapters’ third-person narration, finishes: “We’ve lost. That’s all I know. We’ve lost, we’ve lost.” An epilogue rewrites the prologue and yields closure: “We’ve lost. That’s all I know. And now the game is through.” In such ways, Woolrich brings the overt compositional symmetry of both “serious literature” and the puzzle-driven detective story into the thriller.

Sweating the small stuff

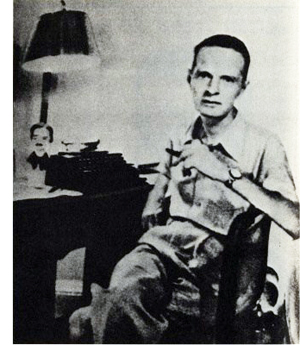

Henry James, 1913; Cornell Woolrich, ca. 1927.

By the 1920s, ambitious Anglo-American writers in both popular genres and “advanced” literature had fallen under the sway of a new model of the novel. Henry James had argued that if the novel was to be a true art form, it needed more compositional rigor, a patterned architectural solidity. He also advocated for a self-conscious control of viewpoint and a greater commitment to concrete presentation of action. (“Dramatize, dramatize!”) A little later, Joseph Conrad’s books had demonstrated the power of shifting viewpoints and multiple narrators, as well as an emphasis on the power of sight.

Popular writers of the nineteenth century, notably Dickens and Wilkie Collins, had already made use of some of these techniques, as did more highbrow efforts, like Robert Browning’s verse novel The Ring and the Book (1868-1869). But in the wake of James and Conrad, tastemakers erected these principles into strict norms for well-made novels. These precepts were set out explicitly in Percy Lubbock’s The Craft of Fiction (1922), and they were picked up in popular writing manuals as well.

Many mainstream fiction writers (and dramatists) took up the techniques promoted by the James-Conrad-Lubbock tradition. Middlebrow novels employed block construction, played with multiple viewpoints, and included an explicit “exoskeleton” of labeled parts pointing up a self-conscious architecture. Joseph Hergesheimer’s Java Head (1919) spreads nine characters’ viewpoints across ten parallel chapters. Detective fiction wasn’t immune to the new methods. Conrad’s exploration of optical viewpoint has a contemporary counterpart in the Chestertonian grandeur of the mystery story “The Hammer of God” (1910). Father Brown is standing at the top of a church.

Immediately beneath and about them the lines of the Gothic building lunged outwards into the void with a sickening swiftness akin to suicide. . . . When they saw [the church] from below, it sprang like a fountain at the stars; and when they saw it, as now, from above, it poured like a cataract into a voiceless pit.

The writers of High Modernism revised the James-Conrad-Lubbock norms, pushing toward more difficult manipulations of time, viewpoint, and subjective states. Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury assigns different narrational voices to its four-block layout, but these make the story world and the time scheme opaque. (Even if you master the stream-of-consciousness technique, you still have to figure out that one character is called by two names and two characters have the same name.)

Like many other writers, Woolrich pulls several post-James techniques into genre literature. His block construction, marked by strict times and viewpoints, along with his labeling of plot phases, owes something to this tradition, as well as to the clever construction of detective stories of the 1920s and 1930s (Ellery Queen, Anthony Berkeley, et al.). He borrows another narrative strategy as well: granular scene description keyed to a character’s sensations and feelings. We get a kind of hypertrophy of Lubbock’s “Show, don’t tell.” In reply to James, Woolrich in effect declares, “Overdramatize, overdramatize!”

In his uncompleted autobiography, Woolrich reflected on his early efforts to compose scenes. A man takes a hotel elevator, and instead of writing, “He got in, the car started; the car stopped at the third and he got out again,” the young Woolrich would pad the trip out to a page or more. This was amateurish, he thought at the end of his life. Yet this sort of expansion of action moment by moment is a hallmark of his 1940s novels. Perhaps it’s what Chandler had in mind when referred to Woolrich “getting deep into every scene.”

As we’ve seen, moments of terror and suspense are rendered in detail. So are the necessary touches of atmosphere. In The Black Path of Fear, the man on the run has told his story to Midnight.

As we’ve seen, moments of terror and suspense are rendered in detail. So are the necessary touches of atmosphere. In The Black Path of Fear, the man on the run has told his story to Midnight.

When I’d finished telling it to her the candle flame had wormed its way down inside the neck of the beer bottle, was feeding cannibalistically on its own drippings that had clogged the bottle neck. The bottle glass, rimming it now, gave a funny blue-green light, made the whole room seem like an undersea grotto.

We’d hardly changed position. I was still on the edge of her dead love’s cot, inertly clasped hands down low between my legs. She was sitting on the edge of the wooden chest now, legs dangling free. . . .

The behavior of light, the insistence on color, the description of the characters’ postures and gestures—these are typical of Woolrich’s scenes.

Even the simplest action employs Lubbock’s “scenic method” to a disconcerting degree. To quote adequately would take pages, but some samples can suggest just how distended and detailed even minimally functional scenes are.

I reached out for a little lamp he had there close beside the bed and clicked it on. Twin halos of light sprang out, one at each end of the shade, and showed up our faces and a little of the margin around them. The shade itself was opaque, to rest the eyes.

Then I just sat back and waited for the shine to percolate through to him, sitting on the bias to him. It took some time. He was sleeping like a log. [The Black Path of Fear]

Any other writer would have retained just the first sentence and the last (but maybe not with the clichéd phrasing). Who cares about the design of a light fixture, or whether the shade rests the eyes? Yet Woolrich feels the need to show and tell as much as he has room for.

A woman comes to a Bowery bar looking for a murder suspect. After a page and a half of banter with the bartender, she finds her quarry hunched over a tabletop. Another page is devoted to rousing him.

He moved slightly, and I saw him looking downward at the floor around his feet. Looking around for something on that filthy place where people stepped and spat all day long. In a moment more I had guessed what he was looking for and I opened my handbag and took out the cigarettes I had provided myself with and held the package ready, with one protruding, as my first silent overture.

His eyes stopped roaming suddenly, and they had found the small arched shape of my shoe, planted there unexpectedly on that floor beside him, and the tan silk ankle rising from it. [The Black Angel]

It takes another page for the drunk to accept the cigarette, and three more for the woman to question him. But he’s too incoherent, so she parks him in a hotel and resumes questioning him the next day—a process that takes fifteen pages and includes detailed descriptions of the hotel room, the light filtering in, and the two characters’ shifting positions in space.

This writer has Roderick Usher’s “morbid acuteness of the senses.” Scenes are thick with smells and sounds. One virtuoso section of Rendezvous in Black is all noises and speech because our center of consciousness is a blind woman. Above all, Woolrich’s scenes revel in optical point of view.

Movies on the page

Sometimes the observer is imaginary, looking at things alongside the character. Detective Wanger enters a murder scene.

They seemed to be playing craps there in the room, the way they were all down on their haunches hovering over something in the middle of the floor. You couldn’t see what it was, their broad backs blotted it out completely. It was awfully small, whatever it was. Occasionally one of their hands went up and scratched the back of its owner’s rubber-tired neck in perplexity. The illusion was perfect. All that was missing was the click of bone, the lingo of the dicegame. [The Bride Wore Black]

Actually, the policemen are interrogating a boy whose father has been murdered. Presumably Wanger doesn’t take the huddle for a craps game. We’re given the mistaken impression of a novice observer who’s watching from a particular angle.

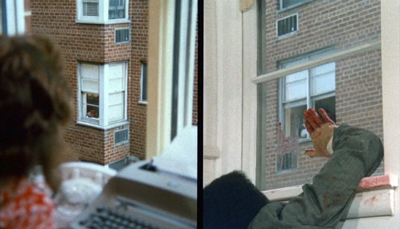

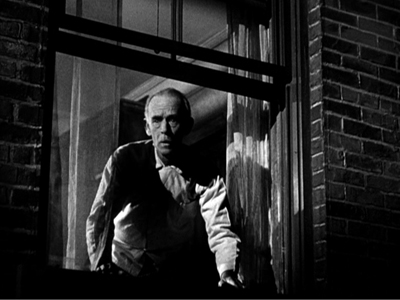

More often, it’s the character who occupies a definite station point, determined by foreshortening and perspectival distortion. The supreme example is of course the short story “Rear Window” (1942) whose original title was “Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint.” One of his clumsy passages in another story tries for the same kind of positioning: “He turned and looked up, startled, ready to jump until he’d located the segment of her face far up the canal of opening between them.”

Woolrich’s interest in the geometry of looking, what can and can’t be seen, finds a natural home in eyewitness plots, of which there were several in 1940s film and fiction (and even radio). In “Rear Window,” the protagonist Jeff tracks his neighbor’s progress from window to window as if studying an Advent calendar. Woolrich strives to capture the exact geometry of Jeff’s field of view.

Woolrich’s interest in the geometry of looking, what can and can’t be seen, finds a natural home in eyewitness plots, of which there were several in 1940s film and fiction (and even radio). In “Rear Window,” the protagonist Jeff tracks his neighbor’s progress from window to window as if studying an Advent calendar. Woolrich strives to capture the exact geometry of Jeff’s field of view.

There was some sort of a widespread black V railing him off from the window. Whatever it was, there was just a sliver of it showing above the upward inclination to which the window sill deflected my line of vision. All it did was strike off the bottom of his undershirt, to the extent of a sixteenth of an inch maybe. But I hadn’t seen it there at other times, and I couldn’t tell what it was.

Jeff’s tightly focused attention contrasts with his neighbor Thorwald’s casual sweeping looks toward the courtyard. The climax will come when Thorwald realizes he’s been Jeff’s target, and Jeff sees in the murderer’s look “a bright spark of fixity” that “hit dead-center at my bay window.”

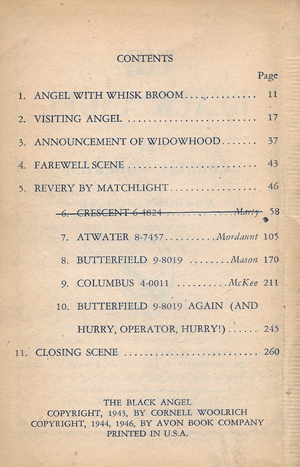

A similar effect occurs at the climax of “The Boy Cried Murder” (aka “Fire Escape”) of 1947, the source of the film The Window (1949). Buddy has been sleeping on a fire escape and is awakened by a murder he watches through a slit in the window shade. The woman comes toward him.

She started to come over to where Buddy’s eyes were staring in, and she got bigger and bigger every minute, the closer she got. Her head went way up high out of sight, and her waist blotted out the whole room. He couldn’t move, he was like paralyzed. The little gap under the shade must have been awfully skinny for her not to see it, but he knew in another minute she was going to look right out on top of him, from higher up.

Again, there’s a stylistic slip (of course she’ll be higher up if she looks out on top of him), but it’s a byproduct of an effort to capture a character’s optical viewpoint.

Sometimes that effort seems pure gimmickry.

I hurried down the street, and the intermittent sign back there behind me kept getting smaller each time it flashed on. Like this:

MIMI CLUB

Mimi Club

mimi club

I could tell because I kept looking back repeatedly, almost in synchronization with it each time it flashed on. . . . [The Black Angel]

Yet even the gimmick seems an effort toward a peculiar kind of vividness—that of a film. The passage imitates alternating shots of the woman looking and the withdrawing club sign. If Woolrich’s modular structure is indebted to strains in modernism and popular fiction, the dense, over-visualized scenes inevitably suggest cinema.

Woolrich worked as a Hollywood screenwriter for a few years and had a lifelong affinity for movies. The books often use cinematic analogies and metaphors, and the characters are frequent moviegoers. (In a 1936 story, “Double Feature,” a gangster takes a woman hostage in a projection booth.) Supposedly Woolrich spent his last years holed up drinking and watching old films on TV. No surprise, then, that some passages echo the look and feel of Hollywood scenes.

Granted, many writers, highbrow and lowbrow, were imitating cinema in Woolrich’s day. Some incorporated filmlike montage sequences to suggest dreams and stream of consciousness. But Woolrich goes farther than most. In Fright (1950), two paragraphs headed “Still Life” survey an empty room that shows signs of interrupted activity—a crumpled newspaper, a note, a burning cigarette, a swaying lamp chain. The passage mimics the sort of tracking shot over details we find in 1940s cinema, continuing for a page until it climaxes in a close-up panning over a body jammed against the door.

When a man realizes his beloved woman lies dead on the bed, a dash can imitate a cut:

But her eyes were still blurry with slee—

His hand stabbed suddenly downward toward the hairbrush, there before her. [Rendezvous in Black]

In Night Has a Thousand Eyes, a woman waits in her car while her father visits the telepath over a period of weeks. Each brief scene starts with the same imagery and phrasing, creating a string of rhyming “shots” across three pages.

In Night Has a Thousand Eyes, a woman waits in her car while her father visits the telepath over a period of weeks. Each brief scene starts with the same imagery and phrasing, creating a string of rhyming “shots” across three pages.

I sat there waiting for him, cigarette in my hand, light-blue swagger coat loose over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, rust-colored swagger coat loose over my shoulders. . . .

I sat their waiting for him, plum swagger coat over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, fawn swagger coat over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, green swagger coat over my shoulders. . . .

I sat there waiting for him, black swagger coat over my shoulders, as I’d already sat waiting so many times before.

The modular approach ruling the books’ overall architecture gets carried down into the texture of scenes, creating parallel mini-blocks that convey the daughter’s anxious acquiescence to her father’s obsession.

Woolrich’s literary optics have strong affinities with cinema. We get an effort to mimic a subjective tracking shot as one heroine circles a garden.

The little rock-pool in the center was polka-dotted with silver disks, and the wafers coalesced and separated again as if in motion, though they weren’t, as her point of perspective continually shifted with her rotary stroll. [I Married a Dead Man]

Likewise, a woman approaching a man slowly tapers into focus.

She was up to him eye to eye before he could even take her in in any kind of decent perspective. His visualization of her had to spread outward in concentric, radiating circles for those eyes, staring into his at such close-range.

Brown eyes.

Bright brown eyes.

Tearfully bright brown eyes.

Overflowingly tearful bright brown eyes.

Suddenly a handkerchief had come up to shut them off from his for a moment, and he was able to steal a full-length snapshot of her. Not much more. [The Black Curtain]

This is just showboating, but it’s uniquely Woolrich showboating.

The same goes for a passage struggling to describe people at a bar as if they were framed in the flattening view of a telephoto shot.

There were eight people paid out along it. They broke into about three groups, each self-contained, oblivious of the others, but he had to look close to tell where the divisions came in. Physical distance had nothing to do with it; they all stretched away from him in an unbroken line. It was the turn of the shoulders that told him. The limits of each group were marked by a shoulder turned obliquely to those next in line beyond. They were like enclosing parentheses, those shoulders. In other words, the end men in each group were not postured straight forward, they turned inward toward their own clique. The groupings broke thus: first three, then a turned shoulder, then three again, then another turned shoulder, then finally two, standing vis-à-vis. [Deadline at Dawn]

Few writers would strive so hard to capture the exact look of figures in space. It will take another page for the viewpoint character to realize that a left-handed drinker has stepped out, because one beer mug isn’t empty and the handle is pointing in a different direction than the others.

It’s not hard to imagine such scenes as Hitchcockian POV shots. In Waltz into Darkness, Durand notices a colonel and his lady in the reflection of the “thick, soapy greenish” window of a café. At first the view yields a blob sporting “three detached excrescences”: a feather in a hat, a bustle, and “a small triangular wedge of skirt.” Eventually this monstrosity draws away “into perspective sufficient to separate into two persons.” Conrad’s “impressionism,” aiming to capture the limits of physical point of view, reaches a new height with Woolrich’s account of exact but imperfect vision.

Some provisional answers to my Woolrich questions run like this. The ingenuity of structure and the inherent fascination of the situations somewhat offset the problems of style. Most of his novels tap our primal interest in the hunt, and if things don’t always pay off neatly, the pursuit has enough detours, hurdles, and pitfalls to sustain interest.

And the writing isn’t totally disastrous. There are well-written passages in every Woolrich novel. Many of the howlers arise from the keyed-up emotion he tries to squeeze out of every scene. Others stem from sheer overwriting and padding, and probably the habit Fisher notes of seldom revising. But other errors are a byproduct of his effort to put every bit of action starkly before us. Straining for sensory vividness lures him into clumsiness (“triangular wedge,” as if all wedges weren’t triangular).

More generally, in both virtues and faults, he displays a dogged, frenzied obedience to the narrative traditions he inherited, and an urge to innovate within them, however eccentrically. Henry James asserted that “a psychological reason is, to my imagination, an object adorably pictorial.” A Woolrich character puts it in a typically convoluted way: “Every time you think of anything, there’s a picture comes before you of what you’re thinking about.”

Beyond the books of Nevins and Renzi, valuable appreciations of Woolrich include Nevins’ essay in his collection Cornucopia of Crime: Memories and Summations (Ramble House, 2010), 53-71; Geoffrey O’Brien’s comments in Hardboiled America: Lurid Paperbacks and the Masters of Noir, second ed. (Da Capo, 1997), 97-100; and James Naremore’s essay on his site, “An Aftertaste of Dread: Cornell Woolrich in Noir Fiction and Film.” For a topical overview of Woolrich’s output, see Mike Grost’s entry on him.

I took Steve Fisher’s account of Woolrich’s writing process from “I Had Nobody,” The Armchair Detective 3, 3 (1970), 164. The quotation from Jacques Barzun comes from Barzun and Wendell Hertig Taylor, A Catalogue of Crime, rev. ed. (New York: Harper & Row, 1989), 561. The Raymond Chandler remarks appear in a 1949 letter to Alex Barris in Raymond Chandler Speaking, ed. Dorothy Gardner and Kathrine Sorley Walker (Plainview, New York: Books for Libraries, 1971), 55. I’ve discussed Mitchell Wilson’s essay, “The Suspense Story,” The Writer 60, 1 (January 1947) at greater length in the online essay “Murder Culture.” More generally, Woolrich’s narrative strategies accord with several I chart in Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling, including the notion of the Variorum.

Woolrich’s early, Fitzgerald-influenced novels reveal seeds of the style to come. A random page from Manhattan Love Song (1932) yields a scene of the hero talking to two women: “Instantly I saw a gleam of admiration light each of their four eyes.”

Astonishingly, Woolrich’s prose glitches don’t rate a mention in Bill Pronzini’s hilarious compilations of bad writing, Gun in Cheek: A Study of “Alternative” Crime Fiction (Coward McCann, 1982) and Son of Gun in Cheek (Mysterious Press, 1987). Pronzini tactfully limits his citations of the classics, only mentioning one Raymond Chandler line: “In spite of his weathered appearance, he looked like a drinker.” Pronzini can find no faults in my personal Style canon: Rex Stout, Donald Westlake (here and here), and Patricia Highsmith.

There’s more on these issues in the entry “The 1940s are over, and Tarantino’s still playing with blocks.” I discuss The Window in “The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt.”

The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt

Looking is as important in movies as talking is in in plays. Thanks to optical point-of-view shots (POV) and reaction-shot cutting, you can create a powerful drama without words.

Everybody knows this, but sometimes it’s good to be reminded. (I did that here long ago.) Now I have another occasion to explore this terrain. But first: How I spent my summer vacation.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

Because I was fussing with my own lectures, I missed the Rohmer events, unfortunately. I did catch all the De Palma lectures and some of the films. Cristina and Adrian offered powerful analyses of De Palma’s characteristic vision and style. I especially appreciated the chance to watch Carlito’s Way again (script by friend of the blog David Koepp) and to see on the big screen BDP’s last film Passion, which looked fine. I confess to preferring some of his contract movies (Mission: Impossible, The Untouchables, Snake Eyes) to some of his more personal projects, but he takes chances, which is a good thing.

Two of my lectures had ties to my book Reinventing Hollywood. “The Archaeology of Citizen Kane” (should probably have been called “An Archaeology…) pulled together things touched on in blogs, topics discussed at greater length in books, and things I’ve stumbled on more recently. Maybe I can float the newer bits and pieces here some time.

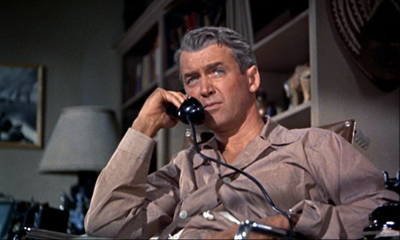

The other lecture took off from my book’s discussion of the emergence of the domestic thriller in the 1940s. We screened The Window (1949), a film that I hadn’t studied closely before. If you can see or resee it before reading on, you might want to do that. But the spoilers don’t come up for a while, and I’ll warn you when they’re impending.

Exploring the how

It is to the thriller that the American cinema owes the best of its inspirations.

Eric Rohmer

One strand of argument in Reinventing Hollywood goes like this.

During the 1930s Hollywood filmmakers mostly concentrated on adapting their storytelling traditions to sync sound and to new genres (the musical, the gangster film). By 1939 or so, those problems were largely solved. As a result, some ambitious filmmakers returned to narrative techniques that were fairly common in the silent era but had become rare in talkies. Those techniques–nonlinear plots, subjectivity, plays with viewpoint and overarching narration–were refined and expanded, thanks to sound technology and quite self-conscious efforts to create more complex viewing experiences.

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book: