Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Could Hollywood possibly be in a box-office slump? Yet again?

Kristin here:

Speculative articles are presumably a lot cheaper for a news publication to run than are those pieces that involve travel, time-consuming research, and tracking down experts to weigh in on important events. The reporter need just sit at a computer, look at whatever evidence is at hand or a phone-call away, and opine on what one might expect to happen in the future. In part, of course, the opinion will be based on what happened in the past. The question is, what sort of information from the past would be most helpful in speculating with some likelihood of being right.

Not that it matters too much, since it’s pretty rare that months after events happen anyone goes back and checks on predictions made about them. That goes for prognosticators of award winners and of future hits and flops.

What might happen?

Facebook profile image for The Numbers research service

In this era of shrinking news media and burgeoning everything-else media, speculation has run rampant. It sustains the 24-hour news channels between breaking stories and a lot of print publications as well. Politics can generation all sorts of guesses and opinions, especially now, since there are so many players who can’t be expected to behave rationally. Variety and The Hollywood Reporter (both of which have advertising-supporting online versions) were once full of useful, hard-news articles that we film historians could snip and file away for, oh, say, cyclical revisions of a film-history textbook. Now David and I still subscribe to both and consider ourselves lucky if an issue has one or two truly informative pieces.

Not that these venerable publications are overwhelmingly full of speculative pieces. There’s the gossip, the real-estate section, the fashion section, the ten or twenty-five or one hundred most-powerful [fill in the blank] in show business, and so on.

But speculation seems to dominate in trade journals devoted to entertainment and film. There are obviously the predictions for Oscars and Emmys and other awards, which have become a year-round occupation. (The Oscars were given out in February, and almost ever since we’ve been getting lists of possible nominees for 2019, many for films not coming out for months.) Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and other trades indulge in awards-prediction coverage far more extensively than they used to, since it presumably extends the period during which film studios and distributors take out expensive “For your consideration” ads.

Box-office trends are often interesting and even useful to read after the fact, in the year-end analyses. They are, however, pretty vapid when presented piecemeal, month by month. There are a great many clichés that writers trying to fill page-inches with speculation can treat as if they are news. One particularly persistent and illogical one is that the industry must be in a slump when total grosses go down after a record-breaking year. We’re now at that stage in 2019 when enough films have come out to allow comparison with last year’s figures by this date.

Pamela McClintock recently wrote such an article for The Hollywood Reporter: “Will Red-Hot Avengers Blaze the Path to a Sizzling Summer?” in the April 30 print edition, and, with the strange habit that these trade papers have of changing articles’ titles for the online version, “‘Avengers: Endgame’ Will Need More Help to Save Summer Box Office”. Just after Avengers: Endgame opened, McClintock wrote that

North American revenue is still down 13.3 percent year-over-year during the January-to-April corridor, throwing cold water on predictions that 2019 could eclipse the best-ever $11.9 billion of 2018. (Before Disney’s Endgame unfurled April 26, revenue year-to-date was running nearly 17 percent behind last year, its lowest clip in at least six years.)

Nonetheless, analysts remain cautiously optimistic that Hollywood can at least match, if not best, 2018’s mark by Dec. 31, with predictions for the global haul settling a new benchmark of north of $41 billion.

These predictions are based on optimism about the plethora of upcoming sequel items and reboots: Aladdin, The Lion King, Toy Story 4, The Secret Life of Pets 2, Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw, Spider-Man, and Godzilla: King of the Monsters.

Let me point out three things.

First, in virtually all cases of year-to-year comparison are based on dollars unadjusted for inflation. Inflation is different in different countries, so trying to achieve a total global figure for any given year would involve a separate calculation for every country where movies are shown—which is close to, if not totally, impossible to do. Adjusted figures are helpful for some purposes, especially for comparing domestic grosses within the USA. For example, virtually everyone was claiming that the three Hobbit films outgrossed the original three Lord of the Rings films. In adjusted dollars, though, LotR is still the champ.

Here’s a helpful hint. Box Office Mojo has an inflation adjuster in its upper-right corner. If someone were to want to compare the domestic gross of Avengers: Endgame to that of some older film, say, Avatar, it would be informative to use the figure shown below instead of, or at least alongside, its gross in 2009 dollars: $749,766,139. (All figures in this entry stated to be in adjusted dollars were done using this feature, and all charts are from BoxOffice Mojo as well.)

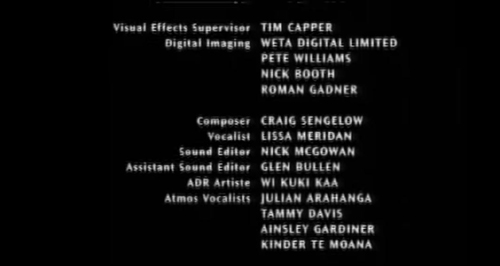

Seeing film grosses go up year after year can give the impression that the industry can go on expanding its earnings forever. Even after a record year like 2002 or 2009 or 2018, pundits seem to assume a slump if the following year sees lower box-office results. But every year can’t be a record year (except in movie executives’ dreams). The list at the left gives the total domestic gross of each year from 2001 to 2018 in millions of unadjusted dollars. Part of the rise is due to inflation. Part of it comes from ticket prices  being raised beyond the inflation rate—which is part of inflation, especially from the ticket-buyer’s point of view. We all know, however, that the number of actual tickets sold is flat or declining, even if it spikes in a record year.

being raised beyond the inflation rate—which is part of inflation, especially from the ticket-buyer’s point of view. We all know, however, that the number of actual tickets sold is flat or declining, even if it spikes in a record year.

Second, usually a very few high-grossing films determine when there are record years. Avatar was the big film of 2009–but it had some help. More on this below.

Third, those high-grossing films are usually released in the summer and in the Thanksgiving-Christmas seasons. True, that cycle is breaking down in the current attempts by studios to avoid releasing the biggest films opposite or even near each other. Black Panther, the top grossing film of 2018, came out in February 16. The studio probably didn’t expect it to do as well as it did, but the very fact that a traditionally “summer”-type film came out that early and topped the charts will just reinforce the industry decision-makers’ believe that there can be big hits at any time of year.

The point, though, is that if really big films come out late in the year, their grosses earned after the New Year are counted for the following year’s total. So for example, Avatar came out on December 18, 2009, and well over half of its domestic earnings came in 2010: $466,141,929 out of the $749,766,139 total. As the list shows, total domestic earnings across the industry jumped by close to a billion dollars between 2008 and 2009, but there was almost no decline in 2010, partly because all but the first two weeks of Avatar’s run came then and partly because Toy Story 3 came out. As for 2009, it may have been the year of (two weeks of) Avatar, but it was also the year of Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, and The Twilight Saga: Full Moon.

Thus in talking about record BO years and why they happened, it helps to look at when the top earners of the previous year were released.

Take another example, 2002, which for years was considered the target to shoot for when it came to setting new records for grosses. That was the first year that the domestic gross was over $8 billion, and 2001 had been the first year over $7 billion.

The year 2002 was cited as the benchmark for the industry because it had four really major films come out–a relatively rare event, or at least it was then. Three of them were from some of the top franchises of all time, and one established what is now the top franchise of all time: Spider-Man, Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

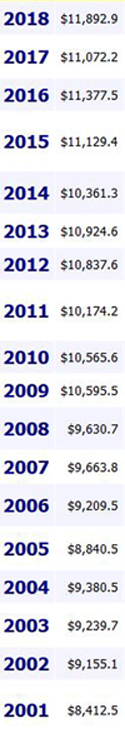

The last two titles were released on December 19 and November 15, so they helped make the 2003 total even slightly higher than the 2002 one—helped out by the top four of that year: The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Finding Nemo (is Pixar itself a franchise?), Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, and The Matrix Reloaded.

In fact, no year between 2002 and 2009 went below the 2002 gross except 2005. In 2003, three films had grossed over $300 million domestically (below right), while in 2005 only one, Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith did. The number two film, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, led to two sequels (from a seven-book series) that fared significantly worse at the box office.

Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith did. The number two film, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, led to two sequels (from a seven-book series) that fared significantly worse at the box office.

Beyond that, however, was the fact that there was relatively little continuing box-office income being generated by 2004 films in early 2005. The top three films had all been released early in 2004: Shrek (May 19), Spider-Man 2 (June 30), and The Passion of the Christ (Feb 25). The number four film, Meet the Fockers (Dec 22), contributed a healthy $103,501,600 to the 2005 grosses, but number five, The Incredibles (Nov 5) was largely played out by the end of 2004 and gave only $8,760,254 to the 2005 total.

Consider the calendar

I’m not going to say whether 2019’s gross domestic box office will surpass that of 2018, because it doesn’t matter that much. Annual figures fluctuate but have been remarkably steady over the years (adjusting for inflation). The industry will make a lot of money as a whole, and Disney will do extremely well. There will be the occasional modestly budgeted film that becomes a hit. Every year has its A Quiet Place or Crazy Rich Asians, numbers 16 and 17 among box-office leaders last year.

I can, however, point out some relevant contributing factors.

First, as in 2005, there’s an unusually small amount of money carried over from films released late last year and still playing early into 2019.

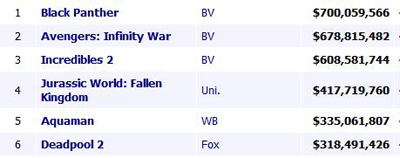

The top four films for 2018, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, Incredibles 2, and Jurassic Park: Fallen Kingdom all came out in the summer or earlier. The fifth, Aquaman, is the exception,  released on December 21, it grossed $335,061,807, of which $196,040,927 was earned in 2019. The next “late” release in the top ten, Dr. Seuss’s Grinch (Nov 9) carried over a mere $2,167,215 into 2019, and Bohemian Rhapsody (Nov 7) a bit more with $25,026, 514 earned after the New Year. Thus 2019 has far less carry-over money contributed by 2018 releases than most years would. That’s presumably one reason–probably the main reason–why the first few months of the year have shown such a drop from the comparable period last year. That’s a little strike against 2019’s total that the pundits tend to ignore. Thus the early-2019 “slump” doesn’t necessarily mean that people are less interested in movie-going or that streaming services have suddenly made a huge impact. It just means that the biggest hits were released too early in the year to carry over much late income. It’s not necessarily a slump. It’s just that box-office income doesn’t really go by calendar years, even though we measure it that way.

released on December 21, it grossed $335,061,807, of which $196,040,927 was earned in 2019. The next “late” release in the top ten, Dr. Seuss’s Grinch (Nov 9) carried over a mere $2,167,215 into 2019, and Bohemian Rhapsody (Nov 7) a bit more with $25,026, 514 earned after the New Year. Thus 2019 has far less carry-over money contributed by 2018 releases than most years would. That’s presumably one reason–probably the main reason–why the first few months of the year have shown such a drop from the comparable period last year. That’s a little strike against 2019’s total that the pundits tend to ignore. Thus the early-2019 “slump” doesn’t necessarily mean that people are less interested in movie-going or that streaming services have suddenly made a huge impact. It just means that the biggest hits were released too early in the year to carry over much late income. It’s not necessarily a slump. It’s just that box-office income doesn’t really go by calendar years, even though we measure it that way.

Given this rare disadvantage, can this year’s blockbusters make up the difference and match or top 2018’s total grosses? Let’s do what Box Office Mojo does: look at what the last film of the franchises made. Let’s do that in adjusted 2019 dollars.

I should note that now more big tentpole films are grossing a very large amount of the total box-office. The three top films that helped create last year’s record made over $600 million domestically: Black Panther at $700.1 million, Avengers: Infinity War at $678.8 million, and Incredibles 2 at $608.6 million. Compare this to the 2003 chart above, where the top earners were making in the $300+ million range. That shift can’t be wholly accounted for by inflation, which isn’t that high.

How many films this year can do that, or at least get over $500 million? Even as I post this, Avengers: Endgame is hovering on the brink of passing $800 million. How about Toy Story 4 (which deserves to, if only for its incredibly clever and funny trailers)? Toy Story 3 made, in 2019 dollars, $480.6 million. Beauty and the Beast made $511.8 million, and The Jungle Book $375.8 million. Disney has two of these remakes coming out this year, Aladdin and especially The Lion King. These three seem the likeliest possibilities.

Beyond that, The Secret Life of Pets made $389.0 in 2019 dollars. On the lower side, The Fate of the Furious made $227.5 and Godzilla $217.2.

The weirdest thing about the current speculation is that the prognosticators aren’t even talking about the entire year. Despite McClintock’s mention of total grosses for 2019 at least matching those of 2018 by December 31, the latest film that she mentions is Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbes & Shaw, due out August 2. But why are we worrying about a slump when it’s plausible that just the films released up to that point could by themselves bring the total at least close to last year’s? We’re witnessing a film that will make as much as two ordinary blockbusters and possibly become the top grosser of all time (in unadjusted dollars, at least). We’ve already seen one low-budget film become a hit. Us grossed $174,580,800–oddly enough, very close to the total for Crazy Rich Asians, which did the same last year. As I’ve suggested, we could anticipate at least two or three summer blockbusters grossing in the $500-600 million range.

But more importantly, there are, after all, films to come after August 2. Big films. Most notably, Frozen 2 on November 22. Frozen made $441.8 in adjusted dollars. There’s the untitled Jumanji sequel; the previous Jumanji entry made $404,515,480. (The BoxOffice Mojo adjuster isn’t adjusting 2017 or 2018 to 2019 dollars yet.) There’s Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. The last Star Wars movie, Solo, was an exception to the saga’s fortunes, making only $213,767,512; so let’s take the previous one, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, which made $620,181,382 domestically. Beyond these there is a bunch of somewhat more modest sequels (Terminator: Dark Fate, It Chapter Two), as well as some potentially big stand-alones (Cats, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, Rocketman). I personally am rooting for Jojo Rabbit (below) to become an unexpected hit. We’ll see.

The lack of attention to films coming out late in the year does make some sense. Right now the industry is concerned to promote its summer films. That’s what marketing people want to talk about with trade-media journalists. November is a long way off. Plenty of time to start speculating about holiday box-office and the awards season come August.

All in all, taking the factors that I’ve laid out into account, it looks like a pretty safe year for Hollywood. I can’t quite help feeling that the hand-wringing over this putative slump just makes for a more dramatic story than one declaring that the 2019 box office is doing fine, thanks. Of course, it’s especially fine for Disney. The heads of other studios might be doing some justifiable hand-wringing.

Update, July 3, 2019: Now we’re into the summer season, and the pundits are still worried because this year hasn’t caught up with last year, where the high-grossing films came earlier in the year than usual. That said, I tried watching The Secret Life of Pets 2 on a transatlantic flight and was so bored I turned it off after about half an hour. That part of Rebecca Rubin and Brent Lang’s Variety article I can believe.

David has written an entry about a related ongoing trope in trade-journal coverage of the movie business. The box-office coverage during “slumps,” real or imagined, often gets linked to the “death of cinema” notion, which David discusses here.

Jojo Rabbit.

Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker

Thor: Ragnarock (2017).

Kristin here:

Not every independent filmmaker secretly longs to direct a big Hollywood blockbuster. Jim Jarmusch made a name for himself 33 years ago with Stranger than Paradise (1984) and won well-deserved praise for Paterson last year. Like other independent directors, Hal Harley turned from filmmaking to streaming television, directing episodes of Red Oaks (2015-2017) for Amazon.

Still, in recent decades the big studios have picked young directors of independent films or low-budget genre ones to leap right into big-budget blockbusters, and those directors have taken the plunge. Doug Liman’s Go (1999) was one of the quintessential indie films of its decade, but his next feature was The Bourne Identity (2002). Colin Trevorrow’s modest first feature Safety Not Guaranteed (2012, FilmDistrict) led straight to Jurassic World (2015, Universal); Gareth Edwards’ low-budget Monsters (2010, Magnolia) was directly followed by Godzilla (2014, Sony/Columbia) and Rogue One (2016, Buena Vista); and Josh Trank went from a $12 million budget for Chronicle (2012, Fox) to ten times that for the $120 million Fantastic Four (2015, Fox).

Something similar happens occasionally with foreign directors. Tomas Alfredson went from the original Swedish version of Let the Right One In (2008, Magnolia) to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011), and the Norwegian team Joachim Ronning and Espen Sandberg, after making Bandidas (2006, a French import released by Fox) and Kon-Tiki (2012, a Norwegian import released by The Weinstein Company) were hired to do Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017, Walt Disney Pictures) and the upcoming Maleficent 2.

Recently women have followed this pattern as well: Patty Jenkins, going from Monster (2003, Newmarket Films) via a long stint in television to Wonder Woman (2017, Warner Bros.), and Ava DuVernay, from two early indie features and Selma (2014, Paramount), again via television, to A Wrinkle in Time (forthcoming 2018, Walt Disney Pictures).

Some of these directors have made the transition smoothly and successfully and some have not. Perhaps the most spectacular success has been that of Christopher Nolan, who went from Memento (2000) via Insomnia (2002) to Batman Begins (2005) and far beyond. But more about him later.

Why have indie filmmakers been able to make this move into the mainstream, often quite abruptly? What about their work appeals to the studios? Of course, there are a variety of reasons, depending on the project and the producers involved. It might be worth following one filmmaker’s career up to the transition to see if there are any clues.

A recent example of this trend is the box-office hit Thor: Ragnarok (released November 3), in the Marvel universe, owned by Walt Disney Studios. Its director, New Zealander Taika Waititi, had directed a handful of modestly budgeted films in his native country. The most successful of those, Boy (2010) made $8.6 million worldwide. After a month in release, Thor will cross $800 million this coming weekend, if not before, and will ultimately gross more than 100 times as much as Boy.

Every filmmaker takes his or her own path before making this leap into blockbuster projects. Waititi did not set out with the ambition to direct a superhero movie with an absurdly high budget. But his career was so full of luck early on that it hardly could have gone better if he had planned it. If you sought a model path to blockbuster fame, you could do no better than to imitate him.

Start by getting nominated for an Oscar

Waititi was actually preparing for a career as a painter, but he was also doing a lot of performing: stand-comedy and film and television acting, perhaps most notably as one of the young flatmates in Roger Sarkies’ 1999 classic, Scarfies. His first brush with superhero movies came with a small role in Green Lantern, 2011. He also, however, made some short amateur films for the 48-Hour film project in Wellington. (Possibly I saw one of them, since I attended the program of shorts during my first visit to Wellington in 2003.) That led to his first professional film, the 11-minute Two Cars, One Night (above).

Virtually all indies made in New Zealand are funded by the New Zealand Film Commission, and in this case the NZFC’s Short Film Fund financed Two Cars. In January, 2004 it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, with which Waititi soon became closely linked. It’s available on YouTube, but be prepared to pay close attention if you hope to understand the thick, rural Kiwi dialect of the charming non-professional child actors. (Waititi’s Wikipedia entry has a good rundown of his television and other work as well as his films.)

The film got nominated for a best live-action short Oscar, and although it didn’t win that, it picked up prizes from the Berlin, AFI, Hamburg, Oberhausen, and other festivals, as well as the New Zealand Film and TV Awards. In fact, the short effectively drove Waititi into filmmaking, as he described in a 2007 interview.

I spent years doing visual arts, doing painting and photography, and throughout that whole time I was acting quite a lot in theater and New Zealand film and television. But for that whole time I wasn’t really sure which one of those artforms I wanted to concentrate on, and eventually just started tinkering around with writing little short films. I made one short film which ended up doing really well, and then suddenly I was propelled into this job as a filmmaker. But actually I didn’t want to be a filmmaker, I just wanted to make short films to try it out! I still don’t really think I’m a filmmaker.

Perhaps not then, but the idea must be quite plausible to him by now.

Get support from the Sundance Institute ASAP

The short and its Oscar nomination launched Waititi’s move into feature filmmaking. In 2005 it was announced that Waititi had been accepted into the Sundance Directors and Screenwriters labs to develop A Little Like Love, which later became his first feature, Eagle vs. Shark.

It was really good for getting my feature made, because I kinda got fast-tracked in the funding process. In New Zealand, the only way of getting a movie done is through the Film Commission, the government agency that funds everything. So I got nominated for the Oscar in March 2005, I wrote the screenplay for Eagle vs Shark in May, then we went to the Sundance Lab in June, got funding from the Film Commission in August, and we were shooting in October.

In January, 2007, Eagle vs. Shark premiered at Sundance. It got a small release in the USA. Having followed filmmaking in New Zealand during work on my book The Frodo Franchise, I saw it here in Madison in a nearly empty theater.

Asked in the same interview about his experiences in the Sundance Directors and Screenwriters labs, Waititi replied:

It was just totally amazing, totally amazing! I think the biggest thing I took away from the lab was finding the tone for the film. In the marketing, it’s going to be presented as a comedy, and I think that’s where a lot of the problems will lie. Even in the criticism of the film, people don’t get that it’s not pure comedy.

The power of the Sundance Institute in supporting first feature films and in others ways promoting independent production worldwide is surprisingly little known. Most obviously the labs have aided the development of American indies like Miranda July’s Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005), as well as supporting Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash (2014) through the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program. The Institute’s impact goes beyond the USA. The first film made in Saudi Arabia, Haifaa Al Mansour’s Wadjda (2012), also was aided by the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program. Sundance’s website emphasizes that the grants and participation in labs is not just for a single film:

With more than 9,000 playwrights, composers, digital media artists, and filmmakers served through Institute programs over the last 35 years, the Sundance community of independent creators is more far-reaching and vibrant than ever before.

If you have been selected for any Institute lab program or festival, you are a member of this community. Sundance alumni receive support throughout their careers, including access to tools, resources and advice as well as artist gatherings and more. Alumni are also encouraged to actively contribute to the Institute’s creative community and to our mission to discover and develop work from new artists.

Waititi’s second feature, Boy, which premiered in January, 2010, carries the credit, “Developed With The Assistance Of Sundance Institute Feature Film Program.” What We Do in the Shadows, co-directed with comedy partner Jemaine Clement, premiered there in January, 2014, though without a credit to Sundance, but his most recent independent feature, Hunt for the Wilderpeople (January, 2016) gave “Special Thanks” to the Sundance Institute.

Asked about Sundance in 2016, when Hunt for the Wilderpeople had just premiered, he declared,

I’ve got a good relationship with them, I love coming here, and I do think that this festival suits my films rather than most of the festivals I’ve been to. I’m not going to Cannes, you know.

Waititi has taken his membership in this exclusive group seriously. In 2015, Sundance created the Native Filmmakers Lab, aimed at supporting Native American and other Indigenous filmmakers. Such support had been a policy in choosing filmmakers to participate in labs up to that point, and Waititi is mentioned as one of past participants. He also is listed as the only individual among a list of major institutions contributing to the Sundance Institute Native American and Indigenous Program:

The Sundance Institute Native American and Indigenous Program is supported by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, Surdna Foundation, Time Warner Foundation, Ford Foundation, Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, SAGindie, Comcast-NBCUniversal, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Embassy of Australia, Indigenous Media Initiatives, Taika Waititi, and Pacific Islanders in Communications.

Taika Waititi’s father was a member of the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui group of the Mãori people, and his mother was a Russian Jew. Waititi used the name Taika Cohen in his early years as an actor.

Live in Wellington, New Zealand

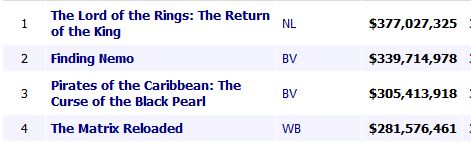

Part of Waititi’s luck consisted of starting his filmmaking career just as Peter Jackson and his team had transformed filmmaking in New Zealand by building up the state-of-the-art production and post-production facilities needed to made The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003). Peter Jackson, Richard Taylor, and Jamie Selkirk, the co-owners of The Stone Street Studios, Weta Workshop, and Weta Digital, offered services by these firms at cost to New Zealand filmmakers; Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh did the same with The Film Unit (later Park Road Post), a lab with sound-mixing and editing facilities. Indeed, it was the only lab for developing film in New Zealand.

From the start, Waititi could take advantage of this large support system. The credits for Two Cars, One Night (above) include Weta Digital for the special effects and The Film Unit for post-production. The credits of the 2005 short version of What We Do in the Shadows thanked Selkirk and Park Road Post, as well as Peter Jackson, who offered undisclosed further support. Beasts of the Southern Wild credits three companies for its special effects, including Weta Digital for the wild-pig episode and Park Road Post for sound-mixing, along with “Very Special Thanks” to the Sundance Institute.”

Having toured those companies in 2003 and 2004, I can state that few indie filmmakers have had access to such sophisticated facilities.

Make some good, eccentric films

Waititi’s first film to capture wide attention was Boy, based loosely on his experiences growing up in a village on the upper east coast of New Zealand’s north island. The director played the young protagonist’s irresponsible father, a comically incompetent gang leader who had deserted his family and returns home to dig up some stolen money he and his pals have buried in an enormous field–without marking where it is. He strives to be a good father, mostly by showing off, as when he tries to casually leap into his car through the window and ends up in a struggle that embarrasses Boy in front of his young friends (above).

It’s a film that brought the blend of poignancy and offbeat humor that Waititi had established in Eagle vs. Shark to maturity.

He followed it with a very different film, What We Do in the Shadows (2014), a mockumentary about three vampire flatmates living in Wellington. (The reference in Thor: Ragnarok to a three-pronged spear for killing multiple vampires is to the main characters of Shadows.) Here the poignancy is gone and the humor pushed to extremes in a fashion that recalls the Monty Python team. In fact, it’s similar to the silly humor of Thor.

Finally, Hunt for the Wilderpeople, a tale of a rebellious foster child going on the lam with his foster “uncle” in the wilds of New Zealand, ultimately made somewhat less money internationally than the other two but had an enthusiastic critical response in the US. There was some Oscar buzz surrounding it, though no nominations resulted. It was, however, a huge success at home, becoming the highest-grossing New Zealand film ever, taking that title away from Boy, which had taken it from the classic Once Were Warriors (1994). It also won best film, director, actor, supporting actress, and supporting actor at the New Zealand Film and TV Awards. Sam Neill’s participation in this film led to his cameo in Thor: Ragnarock.

Coming into the mid 2010s, Waititi had built a solid career as an independent maker of likable, entertaining, skillfully made–and funny– films.

Get tapped for a blockbuster

How and why did Marvel choose Waititi? One might suspect that it was because he already had a Disney connection. When Moana was in pre-production, they brought in many people native to Polynesia to help with planning and design. (Little-known fact: New Zealand is part of Polynesia.) Waititi was brought aboard and wrote a first draft of the script, most of which was altered in later drafts.

When asked if the Moana work had anything to do with the Marvel invitation, however, Waititi responded,

Well, they had not heard of the Disney thing so I know that wasn’t part of it. They have a record making out there and exciting choices and I think what they said to me was, “We want it to be funny and try a whole new tack. We love your work and do you think you can fit in with this?”

Waititi got the call from Marvel in 2015, when he was editing Hunt for the Wilderpeople. USA Today interviewed him in early 2016, when the film premiered.

“They were looking for comedy directors,” he says. “They had seen What We Do in the Shadows and Boy. They especially liked Boy.”

The result was exactly what the Marvel people were after, since the largely positive reviews have invariably cited the humorous, even self-parodic tone of the film. In interviews, Waititi has often spoken of the scene in which Thor and the Hulk have a fight and then sit down to talk about their feelings (top). He wanted to add it because it was the sort of thing that never happens in superhero movies. The Marvel people seem to have liked it. An excerpt provided the tag ending for the first official trailer.

Upstage your actors

I would wager that fans know more about what Taika Waititi looks like than they do about most of the other blockbuster directors mentioned above. He already enjoyed something of a fan base from his earlier films, largely the cult following of What We Do in the Shadows. He remains an actor, playing a major role in some of his own films (Boy, What We Do in the Shadows) and a minor one in others. He’s been a stand-up comic, so he can keep the patter going in interviews and fan-convention panels.

In July, he stole the Thor: Ragnarok Hall H panel at Comic-Con, cracking up the big stars on the panel and getting more laughs from the audience than all of them put together. Waititi’s public persona makes him resemble a character in one of his own films.

Indeed, he again played a supporting character in Thor: Ragnarok, though not exactly in persona proper: Korg, the fighter made of stone. Waititi did both the motion capture and the voice for Korg, and I found the first scene between him and Thor to be the funniest in the whole film.

Even before the release of the film, Waititi quickly gained a reputation for his eccentric clothing preferences. He wore a matching pineapple-print shirt and shorts to the Comic-Con panel (seen in two of the above images). Ava DuVernay was widely quoted as calling Waititi the “best-dressed helmer” in the entertainment world, including in The Hollywood Reporter‘s story on how the director has become a “fashion superhero.” Maybe Waititi is not yet as recognizable to the public as the stars in his film are, but that may not last long. On the day Thor: Ragnarok was released, GQ profiled him, with several photos in different outfits, declaring that he “drips with cool.”

Waititi does cool things that appeal to fans. To raise the money to release Boy in the North American market, he started a Kickstarter campaign with a goal of $90,000 and raised $110,796. He directed one of the popular series of comic Air New Zealand safety announcements based on The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, “The Most Epic Safety Video Ever Made,” with himself playing the Gandalf-like wizard (see bottom). He has 262 thousand followers on twitter and tweets frequently. (This does not count the many unofficial pages like TaikaWaititi Fashion, with 978 followers.)

One-for-them, one-for-me respectability

Once admired indie directors start making blockbusters, they often stress that it is a way of getting smaller budgets for more personal projects of the sort that made them admired to begin with. The generation of movie brats, such as Francis Ford Coppola, established this notion of trade-offs with the big studios.

Perhaps as successfully as anyone in Hollywood, Christopher Nolan has shown quite clearly that such trade-offs can work. Once Memento (2000) made his reputation, he followed it with one mid-budget film, Insomnia (2002) and reached the heights of superhero-dom with Batman Begins. The pattern of alternating personal and one-for-them films is evident from the budgets and worldwide grosses of his subsequent films–although he has become so popular that most studios would happily settle for his “one-for-me” grosses:

Memento (2000, reported budget $9 milion; worldwide about $40 million), Insomnia (2002, reported budget $46 million; worldwide $113 million), Batman Begins (2005, reported budget $150 million; worldwide $375 million), The Prestige (2006, reported budget $40 million; worldwide $110 million), The Dark Knight (2008, reported budget $185 million; worldwide, $1. 005 billion), Inception (2010, reported budget $160 million; worldwide $825 million), The Dark Knight Rises (2012, reported budget $250 million; worldwide $1.085 billion), Interstellar (2014, reported budget $165 million; worldwide $675 million), and Dunkirk (2017, reported budget $100 million, worldwide $525 million, with an Oscar-season re-release announced).

Waititi has invoked this notion of returning to his indie roots at intervals. In 2015 We’re Wolves, a sequel to What We Do in the Shadows, was announced, again to be co-directed by Jemaine Clement. Presumably, however, that project was put on hold, but not abandoned, for Thor. He has other scripts in the drawer and in one interview says, “I’m excited to go back and do those, and then I’d like to come back and do something else here. You know, a one-for-them, one-for-you kind of scenario.”

He has specifically said he would be up for another Thor film:

“I would like to come back and work with Marvel any time, because I think they’re a fantastic studio, and we had a great time working together,” Waititi told RadioTimes.com. “And they were very supportive of me, and my vision.

“They kind of gave me a lot of free reign [sic], but also had a lot of ideas as well. A very collaborative company.”

Specifically, he went on, “I’d love to do another Thor film, because I feel like I’ve established a really great thing with these guys, and friendship.

“And I don’t really like any of the other characters.”

The question is, will Hollywood let him go, at least for now?

Waititi’s first decade or so of filmmaking suggests some reasons why he was approached to make a $180 million epic. The Marvel producers were specifically looking for comedy. Comedies are supposedly harder to sell abroad, but put funny material into a big sci-fi film, and it can do just fine overseas. Many of the other indie filmmakers who made this transition started with genre films–low budget crime or sci-fi films.

Moreover, the Marvel producers who approached him were also willing to give him a free rein, so they were presumably trusting and open to someone whose work they admired. Not all producers would be so lenient. It no doubt helped that in this case, the studio was specifically looking for something original and funny–in short, different from the stolid reputation that the Thor films had gained among critics and viewers alike.

The Most Epic Safety Video Ever Made (c. 2014)

The Fabulous Forties once more: REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD spreads out on the Net

Daisy Kenyon (1947).

DB here:

A couple of weeks ago, when I was in New York for the Museum of the Moving Image series based on Reinventing Hollywood, I also met with Violet Lucca, who runs the admirable Film Comment podcast. She and Imogen Sara Smith talked with me about the book. Our conversation is here.

Our session helped me to develop, somewhat babblingly, points I only touched on in the book. For example, there’s the idea that 1940s films aimed at a certain “novelistic” density (or heaviness, if you’re not sympathetic to them). That’s opposed to the fast-paced “theatricality” of many 1930s films. Of course there are exceptions, and complete outliers like The Sin of Nora Moran, a favorite of mine that Imogen mentioned.

Likewise, I got to reemphasize how filmmakers transformed conventions from fiction, theatre, and radio. And Violet and Imogen were right to draw me out on the role of the screenwriter, which I emphasized more than in my previous research.

It was not only fun but illuminating. Violet and Imogen are very knowledgeable and offered me many good ideas that expanded or nuanced things I tried to say. For example, Violet asked whether the “competitive cooperation” of the 1940s has an echo today. That seems right. Imogen suggested that the emergence of voice-over allowed actors to develop an impassive, internalized acting style characteristic of the 1940s. I wish I’d thought of that. In fact, I wish I’d talked with this pair before I wrote the book.

And yes, Daisy Kenyon is involved.

Also a click away from you is an extract from the book put up on Lapham’s Quarterly. It pulls a section from the first chapter about how amnesia works in popular storytelling. Maybe you’ll find it interesting.

Finally, Daniel Hodges kindly spotlighted Reinventing Hollywood in his very serious, in-depth website devoted to problems of film noir. While my book doesn’t say much about noir, since that wasn’t an operative category for creators of the period, my discussion of the woman-in-peril plot chimes with his very detailed study of many films in this vein. In addition, Daniel offers subtle suggestions about less-discussed sources of noir visual style, and he makes a strong case for spy films as being as important to the trend as hardboiled detective stories.

Thanks to Violet and Imogen for a very enjoyable hour, to Daniel for the link, to Lapham’s Quarterly, and to Rodney Powell and Melinda Kennedy of the University of Chicago Press.

The Sin of Nora Moran (1933).

It’s all over, until the next time

Our Little Sister (Kore-eda Hirokazu, 2015).

DB here:

The perennial Silly Season topic, The Death of Film, is back.

In June, Huffington Post‘s Matthew Jacobs announced “The death of Movies As We Know Them.” He laments the loss of “solid storytelling and bankable stars.” In August, Brian Raftery asked: “Could this be the year that movies stopped mattering?” The author argues that now movies are “Something to Do When the Wi-Fi’s Down.” Echoing the virality theme, Ty Burr announced that two albums, Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” and Frank Ocean’s “Blonde,” “came packaged with better movies than anything in theatres.” For Burr, the summer season confirmed that audiences are more interested in grazing among YouTube clips and luxuriating in eight-hour video serials than watching a feature film. “The two-hour movie, especially in its larger and more commercial form, is becoming a relic.”

Richard Brody eloquently replied to Raftery, noting Beyoncé’s debt to Julie Dash and Khalik Allah’s films. Brody has been around this block before, as I noted in a 2012 blog entry.

The cinema-is-dead complaint, Richard Brody helpfully points out, is now an established genre of movie journalism. In the last few weeks David Denby, David Thomson, Andrew O’Hehir, and Jason Bailey have in different registers sought to revive this quintessentially empty polemic. I’ve gone on about the tired conventions of film reviewing about once every year on this soapbox. (Try here and here and here and here; Kristin got in some licks too). For now I’ll just say that I’m convinced that the Death of Cinema (or Hollywood, or the Intelligent Foreign Film, or Popular Movie Culture, or Elite Film Culture) is simply a journalistic trope, like Sequels Betray a Lack of Imagination or This Movie Reflects Our Anxieties. In short: an easy way to fill column inches.

But after four years, maybe things really have deteriorated. So let’s get specific. What’s really going down the tubes? The theatrical side of the industry? Quality? Cultural cachet?

Movies, your best entertainment value

Bar area of Orange Cinema Club, Beijing.

Let’s look at some current evidence about the industry, thanks to the redoubtable Cinema research division of IHS Media Technology.

The newest symptom of cinema’s demise, according to many, is the rise of Netflix and other streaming platforms. Serial TV is attracting a lot of attention, true, but streaming has long relied on licensing feature films from studios, independents, and overseas companies. TCM and Criterion are launching FilmStruck as a new channel chock-full of classic films from Hollywood and elsewhere. Amazon and Netflix have also begun acquiring and financing features to guarantee a supply of those two-hour films that for some reason people still want to watch.

But what about movies in theatres? Actually, things are pretty robust. Despite everybody viewing at home and on the go, for many years theatre growth has been phenomenal. In 2015 the world added about 12,000 screens, hitting a new high: 153,163. Not counting all our “second screens” (and third), there are more movie screens now than ever before.

By the way, those of us, me included, who worried that the rise of digital exhibition would cause a drop in screens were wrong. Digital was a shot in the arm to theatrical exhibition, and it made 3D a viable platform. That format shows signs of growth, chiefly because of China, and now 16-20% of box-office grosses come from 3D screenings.

In keeping with the expansion of exhibition, for the last decade, the global box office has risen steadily. Almost every year sets a record. The new height is $37.7 billion for 2015, and it seems likely that 2016 will beat that.

As for number of admissions, 2015 also set a record: 7.4 billion, a jump of 13% over 2014. This is a bit more than one ticket for every man, woman, and child on earth. The first half of 2016 is ahead of the same period last year.

Of course revenues don’t equal profits. Jacobs is especially concerned that some big films have been losing money in their domestic theatrical run. But most films lose money in that run. For a long time, ancillary markets (DVD, overseas cable, merchandising, etc.) made up for the deficits. More and more, overseas theatrical is helping in a big way. In a recent rundown, of the summer’s top twenty hits, a print story in The Hollywood Reporter indicates that foreign grosses outweigh US/Canadian ones in most cases, and sometimes by a lot.

For example, big as Captain America: Civil War was in the US, 65% of its $1.1 billion haul was due to the offshore market. X-Men: Apocalypse got half a billion theatrical, 71% of which came from the international audience. Ancillaries will still need to kick in, given the mammoth budgets of films like these, but those ancillaries piggyback on theatrical visibility. As ever, the big pictures pay for a lot of lesser films.

Moreover, so many costs are buried or dispersed in overhead, debt service, tax incentives, deferred payments, far-fetched studio expenses, and the like that it seems hard to know what final profits really are. Nor will we know what, if any, profits are yielded by films from countries with subsidized film industries.

There are many things to worry about in the exhibition business, but it doesn’t seem on the verge of collapse. Let’s keep a sense of proportion. Here is what the death of “our cinema” might really look like.

Theatre admissions fall 45% over six years. Studio profits fall 80% over the same period. One-sixth of theatres close. Major overseas markets refuse to remit the earnings of Hollywood films. Audiences turn increasingly to other leisure activities.

This was the state of the American film industry in 1953. The prosperous war years, culminating in the all-time admissions high of 1946, were over and the studios went into sharp decline. Thanks to the 1948 Supreme Court “Divorcement Decree,” the studios lost control of their theatres, relinquishing not only valuable showcases for their product but also millions of dollars of prime real estate.

Yet as we know, 1953 didn’t end cinema, not even American cinema. As the old studio system waned, a new one eventually replaced it. In the process, Hollywood continued to make major films. Filmmaking abroad—in Asia, Europe, and South America especially—flourished. Film festivals sprang up, and a new young public proved eager to watch movies from a variety of cultures. Avant-garde and documentary movements gained traction, partly because of the widespread dissemination of 16mm.

No one, so far as I can tell, predicted the end of cinema, or Hollywood, because of the 1947-1953 crisis. That person would have looked very foolish. Things today aren’t nearly so severe.

Long, hot summers

What about quality? A. O. Scott points out that the way to quell fears for the End of Good Cinema is to go to a film festival. It’s good advice that we’ve given as well. Richard Brody, who has I think seen everything, responds to Raftery by reminding us of many valuable films that the naysayers ignore. Another way to remain calm is to look at a little history.

What about quality? A. O. Scott points out that the way to quell fears for the End of Good Cinema is to go to a film festival. It’s good advice that we’ve given as well. Richard Brody, who has I think seen everything, responds to Raftery by reminding us of many valuable films that the naysayers ignore. Another way to remain calm is to look at a little history.

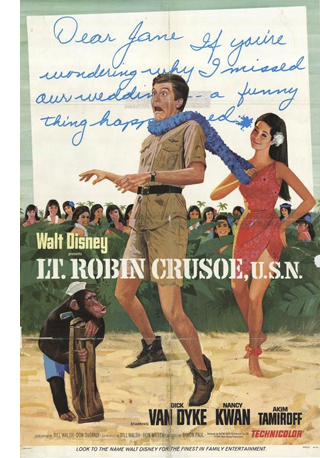

Things often seem grim at summer’s end. Let’s go back fifty years, to the summer of 1966. In those days, the blockbusters and prestige pictures were saved for fall and winter. Indeed, the blockbusters were largely the prestige pictures, the adaptations of novels and plays. The big grosser of the year was Hawaii, released in October. Two others were The Bible: In the Beginning (September) and A Man for All Seasons (December). But two of the top-grossers hit the jackpot in the summer: Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf? (July) and Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN (June).

Pause on this last title. Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN was an indisputably lowbrow hit, a Disney comedy starring Dick Van Dyke. The fact that it earned $10.1 million (about $75 million today) might well have set critics worrying about American tastes. Worse, they might have concluded there was no hope, because from 1950 to 1970, twenty Disney films appeared in the annual top five. That record includes not only animated classics but In Search of the Castaways, That Darn Cat, and Darby O’Gill and the Little People–enough to make intellectuals despair of American moviegoers. Robin Crusoe‘s summer success might have seemed another sign of End Times.

Summer 1966 also saw The Ghost and Mr. Chicken, Fantastic Voyage, the remake of Stagecoach, a Bob Hope comedy, the low camp of Batman, and the high camp of Modesty Blaise. The 1966 counterpart to our spate of superhero sagas was a cycle of spy movies, somber or spoofy. The summer yielded Blindfold, Arabesque, and even The Man Called Flintstone. Along with these came Nevada Smith, Khartoum, What Did You Do in the War, Daddy?, This Property Is Condemned, and Wild Angels.

Some of these are well-remembered, mostly by viewers exposed at an impressionable age. For prestige there was and remains Virginia Woolf. For auteurists, there was Three on a Couch and Torn Curtain, and perhaps Modesty Blaise. As for the rest, most were and are still decried as junk.

Things were not looking good for American cinema. The Sound of Music had just won the Best Picture Oscar, a middlebrow shot across critics’ bow, and Pauline Kael was turning angry firepower on the massive threat posed by The Singing Nun. In the summer, the Times lambasted Hitchcock and Jerry Lewis. As far as I can tell, the follow-ups to the Bond boom pleased hardly anybody.

In sum, we forget just how godawful summer movies can be, year in and year out. The few we remember after Labor Day bob up from a river of sludge. We should be grateful for Indignation, Finding Dory, Lights Out, The Shallows, Hell or High Water, Don’t Breathe, The BFG, Kubo and the Two Strings, and probably half a dozen others I haven’t seen. (But not Jason Bourne, which I have.) Ben-Hur wasn’t as terrible as I’d been led to believe.

And of course, everybody’s pumped for the fall, for Snowden and The Arrival and The Birth of a Nation and La La Land and Manchester by the Sea and all the rest. 1966 critics were looking forward as well, but to what? Not only Hawaii, The Bible, and A Man for All Seasons but also Is Paris Burning?, Grand Prix, Any Wednesday, The Sand Pebbles and more spy movies (Gambit, The Quiller Memorandum). Not so exciting by our standards; Big Pictures were more square then.

True, also coming up in the fall of ’66 were The Fortune Cookie, Seconds, A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum, Fahrenheit 451, The Professionals, Loves of a Blonde, and Blow-Up. But even then some critics stayed unhappy. Kael denounced Blow-Up, and Vernon Young intoned: “The party’s over. . . . Another phase of film history, in many ways the most creative, is drawing to a close.” Sound familiar?

Conversation starters and stoppers

End-of-movie writers argue that pop music and Quality Television are usurping the cultural place of film. But I’m skeptical, because I don’t think film is playing in the same arena.

Odd as it sounds, film has never been popular on the scale of other mass media. Before TV, radio listeners far outnumbered film audiences. Via radio and records, a hit tune reached more people than nearly any movie. Even today, radio audiences are surprisingly big. Nielsen reported in 2014 that just in the 18-35 age group, 65 million people listen to radio broadcasts each week. That’s nearly three times the average number of all viewers who attend movie theatres in a week.

Once TV came along, it became another truly mass medium. 73 million people, over a third of the US population, watched the Beatles on Ed Sullivan in 1964. TV is still the big game. More than 20 million people watch The Big Bang Theory each week. It’s reported that 8.9 million people watched the season finale of Game of Thrones in original cablecast, and 23 million in all its iterations. Yet, again, about 23 million people see all the movies playing in a given week.

The plain fact is that visiting a theatre to see a movie has been, throughout most of American history, a middle-class pastime. It’s relatively expensive, and getting more so. It’s not quite niche, not as rarefied as theatre or concert music or novels, but still not on the scale of other media. We ought to expect that memes will spread faster and more pervasively in pop music and television platforms.

Our critics are concerned that films aren’t part of what Raftery calls “the pop-cultural conversation.” “What in popular culture got people excited or even interested over the last few months?” asks Burr, going on to worry that movies didn’t do so. This is a strange criterion for judging films. Hula hoops, Rubik cubes, Chia pets, and Donald Trump’s coiffure have all been part of the cultural conversation. Some good films excite lots of people, and some don’t (partly because those people don’t know of them). And of course many people got excited by films Burr and Raftery considered bad, like Suicide Squad. Excitement may not be a great standard for excellence.

The cultural-conversation gambit suggests that mere popularity needs to be accompanied by a special jolt, the hum of nowness, the throb of hipness. Financially successful films like The Jungle Book or Finding Dory don’t give off much buzz. Where does that special ingredient come from? Apparently, now, the Netizens. It’s natural that critics, who are assigned to surf the waves of mass tastes, would identify important art with what’s trending on Facebook. It’s their job to hop on what’s hot.

Or in truth, help make it hot. When critics treat what’s buzzy as valuable, they agree with marketers, and cooperate with them. How many critics who loved The Dark Knight had been prompted by the campaign that played up “Why So Serious?” and other memes that publicists thought would stick? Kristin has documented how The Lord of the Rings marketers set the agenda for journalists by means of junkets and Electronic Press Kits (above), while wooing fans with carefully judged opportunities to participate online (a “pop-cultural conversation,” for sure). The typical big film is positioned by the marketing campaign, and even unanticipated responses, especially if the film is strategically ambiguous, can feed ticket sales.

The People don’t start the cultural conversation; they react to what they’re given. The conversation is started by the studios, and they try to channel it. They generate the “controversies” about making the protagonists of Star Wars Episode VII: The Force Awakens a woman and an African American man. The critics pick up the story. (Remember: column inches.) Viewers dutifully enter their opinions on blogs, tweets, and comments columns–which the critics then re-spin. As Brody points out of Quality TV, it’s all about expanding discourse, indefinitely. Criticism begets “comments” which beget chitchat. This is less a conversation than a perpetually chattering flashmob.

A side note: I wonder if making cultural buzz a criterion of worthwhile cinema doesn’t owe something to the influence of Pauline Kael. She sent contradictory signals on this score, worrying that audiences were too easily bought off; the industry jollied them into accepting junk as fun. But she thought that one reason to like, say, Bonnie and Clyde was the fact that it was “contemporary in feeling.” It brought into movies “things that people have been feeling and saying and writing about.”

For a moment let’s accept the assumption that worthy movies have some broader cultural impact. How could we measure that? I suggest the Tagline Test. A movie enters the culture when a line becomes instantly recognizable. At its best, the tagline applies to an immediate situation. You step into a startling new setting and tell your friend you don’t think you’re in Kansas any more. You talk about your boss making you an offer you can’t refuse. You’re bargaining and you say, “Show me the money.” TV gives us plenty of catchphrases, of course. (“You rang?” “Not that there’s anything wrong with that.” “Don’t have a cow, man.” “That’s what she said.”) This is one symptom of a show’s buzziness.

When I came up with the Tagline Test, I thought it supported the doomsayers’ diagnosis. I couldn’t think of many memorable lines from films after the 1980s. Had TV taken over the traffic in catchphrases? Crowdsourcing among two fairly diverse populations came up with a big set. Here’s a sample:

Hasta la vista, baby. Houston, we have a problem. That’ll do, pig; that’ll do. I drink your milkshake. The Precious (enunciated in a high voice). With great power comes great responsibility. Stop trying to make fetch happen. She doesn’t even go here. Stay classy. That escalated quickly. The first Rule of Fight Club… 60% of the time, it works every time. Little golden-haired baby Jesus in the crib. Schwing! Coffee is for closers. King of the World! Stay alive; I will find you.

The Big Lebowski is a virtual encyclopedia of them: The Dude abides. Obviously you’re not a golfer. That rug really tied the room together. Nobody fucks with the Jesus. So too Napoleon Dynamite: Whatever I feel like I wanna do GOSH! I’m pretty much the best in the world at it.

Maybe you don’t agree that these are all equally common; I didn’t know about the Mean Girls and Napoleon Dynamite ones. But all I need to show is that recent movies have entered the “cultural conversation” quite literally. Maybe it just takes months or years for movie taglines to replicate in everyday life. Anyhow, those who want movies to get all buzzy don’t have to worry. With Oscar season upon us, the frenzy will begin. In fact it already has, with Nate Parker’s The Birth of a Nation.

Who’s we?

In talking about “our” cinema, I’ve been too glib, though this angle fits with an assumption of the death-knoll critics (“Movies as We Know Them”). Of course, Jacobs, Raftery, and Burr all acknowledge that Hollywood isn’t making movies just for us; it’s a world industry. People elsewhere (many recently arrived in the local equivalent of the middle class) seem keen to participate in American popular culture, with fashion, music, TV, and websites. Hollywood entertainment, lame as it often is, is part of being cosmopolitan.

In talking about “our” cinema, I’ve been too glib, though this angle fits with an assumption of the death-knoll critics (“Movies as We Know Them”). Of course, Jacobs, Raftery, and Burr all acknowledge that Hollywood isn’t making movies just for us; it’s a world industry. People elsewhere (many recently arrived in the local equivalent of the middle class) seem keen to participate in American popular culture, with fashion, music, TV, and websites. Hollywood entertainment, lame as it often is, is part of being cosmopolitan.

Still, maybe it’s time to admit that we don’t own Hollywood. Maybe we never did, but it seems clear that with globalization “our” popular cinema is becoming something else–not exactly “theirs,” but not wholly ours either. Now You See Me 2 may have attracted only mild interest here: little cultural chitchat, except maybe among magicians, and $65 million box office (less than Lt. Robin Crusoe, USN). But it garnered $266 million internationally. Nearly a hundred million of that came from China, perhaps partly owing to long stretches set in Macau and short stretches featuring Jay Chou Kit-lun. And the director was Asian-American Jon M. Chu.

Now Lionsgate announces a Now You See Me spinoff, a feature co-production with China that will use local stars. So who owns this franchise? “Us” or “them”? If it disappoints us and pleases them, how does that mean that movies are so over? Maybe other countries’ cultural conversations are pulsing with talk of the Four Horsemen (one of whom is a woman).

It’s long been obvious that other film industries create their own versions of Hollywood. Europe, India, and Hong Kong have done it for decades. Current Chinese hits borrow from “our” rom-coms, action pictures, and comedies. In Stephen Chow Sing-chi’s The Mermaid, you can watch a blockbuster premise coming unglued. It’s a mixture of sentiment, message, slapstick, and bad taste; Hollywood twisted up in Chow’s characteristic funhouse mirror.

This won’t stop. One of the most astonishing and puzzling facts of contemporary cinema gets almost no press, maybe because it contravenes the death-of-film narrative. Over the last ten years, there has been a huge rise in the number of feature films.

In 2001, the world produced about 3800 features annually. The number passed 4000 in 2002, passed 5000 in 2007, and passed 6000 in 2011. In 2014, IHS estimates, over 7300 feature films were made in the world. There are now fifteen countries that produce over 100 features a year. As a result, only 18% of the world’s features come from North America. The boom took place despite the rise of home video, cable, satellite, DVD, Blu-ray, VOD, and streaming. And it happened despite the fact that American blockbusters rule nearly every national market. This may be a bubble, or it may be genuine growth. In any case, we ought to investigate the reasons that a great many people around the world stubbornly persist in making two-hour films. They don’t appear to care if We sense a summer slump.

While I was preparing this entry, Kristin and I went to Our Little Sister, Kore-eda Hirokazu’s 2015 film about three sisters abandoned, first by the father, then by their mother, and raised by the moderately stern oldest sister. The plot follows what happens when the trio takes in their half-sister after her mother dies. This is a movie that’s bereft of villains and almost totally lacking in conflict. The sisters’ misjudgments and flaws cause them problems, and sometimes they quarrel, but mostly we see decent people trying to lead happy lives, and largely succeeding. Compared to Kore-eda’s debut, Maboroshi (1995), it’s pictorially rather conventional. (That damn sidling camera.) But its episodic, open-textured plot, its quiet depiction of changes across seasons and years, and its casually serene vision of family and community make it one of the most enjoyable and moving films I’ve seen this year.

Based on the graphic novel Umimachi Diary, the film participated in Japan’s “cultural conversation.” It’s certainly a mainstream commercial movie, of a sort that Japanese studios have turned out for decades. It won solid attention on the festival circuit too. It earned a 92% rating on Rotten Tomatoes, up there with Kubo and Hell or High Water. But such a reserved, sentimental film will never get the edgy buzz that our doomsayers want. Sentiment, after all, is anathema to our dominant mode of consuming pop culture, that of cool, ironic knowingness.

I don’t want to oversell Our Little Sister: Kore-eda is no Ozu. But this film and many others remind us that worthwhile films are still made, and released, and available outside the circus tent of Entertainment Weekly cover stories. (In this case, Americans’ thanks should go to Sony Pictures Classics, now celebrating its 25th anniversary.)

In short: Forget the zeitgeist; it likely doesn’t exist, apart from marketers’ dreams and journalists’ deadlines. Forget the cultural conversation; there’s not only one. Seek out the films that matter to you, and not “to us.” Stay classy!

Thanks to correspondents on two listserves, that of Communication Arts film folk and that of the Art House Convergence. A great many people made many suggestions, with the inevitable duplication, so thanking everyone by name would be protracted. But you know who you are.

My information on worldwide production and exhibition comes from issues of IHS Media & Technology Digest and Cinema Intelligence Report. Special thanks to David Hancock, Director of IHS Cinema division. Pamela McClintock’s “Summer Anxiety Despite Near-Record Numbers” in the 16 September Hollywood Reporter print edition contains the top-twenty film list I mention; that chart isn’t included in the online version.

On the summer 1966 US releases, see The Film Daily Yearbook of Motion Pictures 1967 (Film Daily, 1967), 144-168. I charted the year’s top-grossers from Susan Sackett, The Hollywood Reporter Book of Box Office Hits (Billboard, 1996).

My quotations from Pauline Kael come from her Bonnie and Clyde review reprinted in Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (Atlantic Monthly Press, 1968), 47. My quotation from Vernon Young is the opening of his “The Verge and After: Film by 1966,” in On Film: Unpopular Essays on a Popular Art (Quadrangle, 1972), 273.

It’s probably irrelevant to mention that both Scorpio Rising and The Brig were released, in some sense, in summer 1966.

P. S. 18 September 2016: And see the practically real-time followup. Remember when blogs were like Twitter is now?

12,000 tickets are sold for premiere screenings of Baahubali (2015) in Hyderabad, India.