Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Comic-Con: The end of an era, and other highlights

Kristin here:

Long-time readers of this blog may recall that in 2008 I went to Comic-Con for the first time. I can’t recall exactly what led me to take the plunge. It may have been that by that time it was evident that the con had grown into a major opportunity for Hollywood studios to publicize their upcoming blockbusters to their core audience and I wanted to witness the process in person. Until this year, I hadn’t returned to Comic-Con. I was motivated in part by the fact that this was the last big promotional event for a film in the Lord of the Rings/Hobbit franchise. I had briefly discussed Comic-Con in relation to LOTR in The Frodo Franchise, but I had not witnessed any of the appearances of cast and crew promoting the first trilogy. This was my final chance, the end of an era.

I blogged about my first visit four times. I wrote about the LOTR/Hobbit presence on the Frodo Franchise blog. On this blog I gave an overview of the Comic-Con experience, analyzed why Hollywood poured so many resources into an event nominally about comic books, and posted a conversation between Henry Jenkins and me. Henry, who had helped found the area of fan studies back in the 1990s with such widely cited publications as Textual Poachers, was also a Comic-Con newbie that year, and we shared our reactions. (This year Henry was on a panel, “Creativity Is Magic: Fandom, Transmedia, and Transformative Works,” one of a number of panels on fan culture. I missed it because I was in line for Hall H. More on that below.)

A friend of mine who has a press pass assured me that they were not as hard to obtain as I had feared, so, based on my collaboration on this blog and my position on the staff of TheOneRing.net, I applied. To my delight, I was granted one, so I set out to cover Comic-Con more officially.

Going to Comic-Con alone isn’t nearly as fun, and I was lucky enough this year to meet up there with my friends, Professors Jonathan Kuntz and Maria Elena le las Carreras and their irrepressible daughter Rebecca, who are always terrific company.

Preview night

On the Wednesday evening before Comic-Con begins, there is a preview. This means that people with various special passes can get into the big exhibition hall where most of the booths are set up. These range from dealers in rare comic books to the biggest entertainment companies, like Warner Bros. and Lego. Many of them offer unique items only for sale or give-away at Comic-Con.

Many attendees have realized this, and they buy tickets that include the preview evening. The floor was much more crowded than when I attended the preview night in 2008. There were lots of lines with people trying to get those unique collectibles.

Others were there to look at comics. Yes, there are still plenty of comics at Comic-Con. There are dealers offering rarities, as in the image above. There are comics publishers with their latest offerings.

A particular favorite of ours is Fantagraphics, which specializes in reprinting comics. They’ve launched a set of hard-cover volumes of Walt Kelly’s syndicated Pogo strips. They also, I discovered, are doing a series of Don Rosa comics, also in hardback. In fact, when I was strolling around the booth, I realized that Rosa himself was signing autographs until 8 pm. It was then 7:59, so I grabbed volume 1 and was the last person to get my copy signed. By the way, it includes “Cash Flow,” one of the Uncle Scrooge stories I mentioned in our first blog entry on Inception. Volume 1 hasn’t actually been published, but it’s available for pre-order on Amazon.

The big moment of my evening, entirely by chance.

My first press conference

Once you’re granted a press pass, your name is put on a list made available to the exhibitors and publicists planning events. Companies big and small send you announcements about signings, press  conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

conferences, swag available at booths, parties in downtown venues, and so on. Many of these events promote video games, graphic novels, and television, but one sounded intriguing to my film interests: a press conference for Penguins of Madagascar, an entry in Dreamworks’ animated Madagascar franchise. The odd thing was that the event was scheduled in the morning at 11:15, fifteen minutes before the DreamWorks panel in Hall H. If we came to the conference, we couldn’t get into Hall H–unless the PR people reserved seats there for us. The big attraction was that some of the voice talent, including Benedict Cumberbatch and John Malkovich, as well as the two directors would be there.

I showed up and got a front-row seat off to the side. The room filled up (right).

The event itself started somewhat late, and two gentlemen who were not Benedict Cumberbatch or John Malkovich appeared and answered some questions. (I would give their names, but the usual signs put on the table in front of guests were not in evidence.) We were approaching 11:25. John Malkovich and another gentleman appeared. Another couple of questions were asked, and someone announced that Benedict Cumberbatch’s plane had gotten in late the night before and besides we had to leave to make room for the next event scheduled in the room. We were not escorted to reserved seats in Hall H, where I hear that Benedict Cumberbatch did appear.

I can only trust that this is not how most press conferences turn out. Perhaps I will be invited to another one and find out.

Bill Plympton in person

Given that I had no option to go to the Hall H DreamWorks Animation presentation, I sought out an alternative among the several items offered during the noon slot. I had had my eye on a panel which had as its guests the well-known animator Bill Plympton, as well as Jim Lujan, the co-director of the feature-length Revengeance, in progress. David and have long been fond of Plympton’s work, especially his laugh-out-loud classic, Your Face (1987), which was nominated for an Oscar. It’s just a series of distortions of a man’s face as he sings an utterly wimpy love ditty (above).

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Plympton continues to be remarkably prolific. He has worked on fourteen episodes of The Simpsons, including doing twelve couch gags. Now he has a feature, Cheatin’, which will be shown for a week starting on August 15 at the downtown independent in Los Angeles. (Earlier this year it played at Slamdance, but I can find no theatrical release date.) You can see a short appeal animated by Plympton for the film’s Kickstarter appeal; its quite informative about the animation techniques used. The campaign itself is over, having raised $100,916, exceeding the goal of $75,000.

Apart from clips from Revengeance, Plympton also showed a brand new short, Footprints, a charming tale of a man’s search for a mysterious house invader. It will be shown on August 14 as part of the Hollyshorts Film Festival, which will honor Plympton with the Indie Animation Icon Award. The film was entirely hand-drawn in black and white and then colored digitally.

During the panel there was a contest for a T-shirt. The question was: What is Bill Plympton’s middle name? Despite a plethora of cell phones, laptops, and tablets in the audience, no one could come up with the right answer. A second question was put forth: what was Plympton’s first theatrically released film? “The Tune,” came a cry from the audience. It was Sam Viviano, art director of Mad Magazine; he walked off with the shirt. Plympton then sheepishly confessed that his middle name is Merton.

Plympton’s films have been hard to find online, but this fall they will become available on Source HD: “It’s the entire catalog, everything I’ve ever done.” That includes about 60 shorts. As a result of this online exposure, he says, “I expect that when I come back to San Diego next year they’re going to have to give me one of those huge 2000-seat rooms.” I hope so, and I hope it will be filled–but not so jammed that I could not get a seat.

Plympton offered all attending his panel a free autographed drawing. I went to collect mine at his booth in the exhibition hall and found him drawing (right), as he must constantly be doing. Note the Cheatin’ poster behind him at the left and the usual bustle of Comic-Con in the background. He paused to dash me off a delightful image of his famous Dog character. (An animator who doesn’t use cels has to be really fast at drawing.)

Plympton DVDs are not all that easy to find, though you can get them and other merchandise at his website’s shop. If you don’t know his work, it’s time to start catching up.

A new experience: The Indigo Ballroom

Seeking to accommodate more fans without violating fire regulations, Comic-Con has expanded into nearby buildings. One of the facilities utilized this year was the Hilton San Diego Bayfront, just across from the Convention Center on the Hall H end. That’s where the DreamWorks press conference sort of took place. Its biggest room was the Indigo Ballroom. I’m not sure it had 2000 seats, but I wouldn’t be surprised.

My colleagues at TheOneRing.net have been presenting panels on the Hobbit series for several years now. In fact, my visit to Comic-Con in 2008 was as a participant on one of those panels, speculating much before the fact on the shape that the Hobbit project would take. At that point the cast hadn’t even been chosen. I suggested that Wisconsin’s own Mark Ruffalo would make an excellent Thorin. I still think he would have, but Richard Armitage has gained a large fan following in that role. I’m not sure that at that early stage Martin Freeman was everyone’s favorite candidate for Bilbo, but he soon became so–including mine. The man is a born hobbit.

That 2008 panel took place in a relatively small room in the Convention Center. In more recent years, the TORn panel has been joined by such luminaries from the filmmaking team as Richard Taylor. It has gained such a following that this year it was booked into the Indigo Ballroom.

Then we learned that George R. R. Martin was booked into the same room in the time-slot directly before TORn. (I’m sure you all know who he is, but for the few who don’t, I’ll just say, he’s the author of the “A Song of Fire and Ice” series, of which Game of Thrones is the first book.) We were all convinced that Martin’s session would be jammed and furthermore that an overlap in fandoms would mean that the audience there for Martin would stay for the TORn panel, excluding those who showed up just before the TORn session. There was much discussion as to how TORn staff not on the panel (like me) could get in and be sure of a seat. How many seats could be reserved? We didn’t know.

I determined to support my colleagues and attend the TORn panel. The question was, how many sessions would I have to sit through to make sure I could get a seat? (Rooms are never cleared between sessions at Comic-Con, since doing so would take too much time and would mean that people in one room for a session would not be able to get in line for the next session in that room. Hence the strategy of sitting through multiple panels in the same room to guarantee a seat at the one you really want to see.)

I arrived early in the afternoon in the middle of a session about some show on Comedy Central. This finally ended and the George R. R. Martin panel began. To my surprise, it was only about two-thirds full. I learned later that Martin often attends Comic-Con. Moreover, this time he wasn’t talking specifically about Game of Thrones. The session was billed as “George R. R. Martin Discusses In the House of the Worm.” The title in question is a new comic-book series that Martin is involved with. (Above, William Christensen, publisher at Avatar Press, interviews Martin.)

I had expected to sit through Martin’s session merely waiting for the TORn one to begin. I had read Game of Thrones, widely assumed to be heavily influenced by The Lord of the Rings. Game of Thrones was entertaining, but by the end I found it repetitious. I figured that the series could only become more so, so I quit there. I haven’t seen the TV episodes. Yet Martin turned out to be quite entertaining. He is a long-time fan, and his reminiscences about fandoms during the 1960s and onward were fascinating. He’s a lively, knowledgeable, and entertaining speaker with a wide experience in both reading and creating fantasy works in those days. His presentation made me wish that I liked that first book better.

The next session was “An Unofficial Look at the Final Middle-earth Film: The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies.” (Actually in the program the title said “Final Middle-Earth Film,” but I’m sure my colleagues did not make that capitalization error when they proposed the panel.)

The panel consisted of, from the left, Chris “Calisuri” Pirotta, a TORn co-founder; John Tedeschi, long-time staffer; Cliff “Quickbeam” Broadway, frequent contributor to the site; Kellie Rice, staffer and half of the “Happy Hobbits” fan duo; and Larry D. Curtis, another long-time staffer and frequent contributor. Chris and Cliff were among several TORn interviewees when I was researching The Frodo Franchise.

TORn has made annual appearances at Comic-Con, usually speculating in expert fashion on what might be included–or not–in the next film. Staffers comb the previous films, trailers, Peter Jackson’s production diaries, publicity photos, and cast and staff interviews, seeking for clues. While presenting their findings, they point out things in the earlier parts that people might not have noticed or may have forgotten.

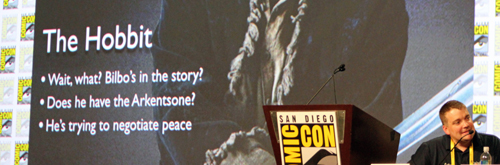

The first line in the Powerpoint image above refers to widespread fan annoyance that Bilbo seems to have been pushed to the periphery of his own story in The Desolation of Smaug. This is a topic of frequent comment on the website. The TORn panel was held on Thursday, two days before any of us had a chance to see the first teaser-trailer’s premiere on Saturday in Hall H. (More on that below.) Although there are shots of Bilbo in that trailer, they mainly show him staring offscreen and reacting. I was left hoping that this is not an indication of more sidelining of our protagonist. In Tolkien’s book Bilbo decides to sit out the Battle of Five Armies and gets knocked unconscious early in the fighting; given that he’s our point-of-view figure, the battle is mainly told through other characters describing it afterward. No one expects Peter Jackson to stay true to that action and sacrifice the chance for another epic battle scene, so maybe Bilbo will get to do his share of fighting.

This year’s celebrity guest made an appearance at the end and took a few questions: Jim Rygiel, multi-Oscar-winning visual effects supervisor for The Lord of the Rings (and more recently Godzilla and The Amazing Spider-Man):

Whether the panel members were right in their speculations will not be known until December 17 (in the USA). Right or not, it was an entertaining and informative session.

What were they really there to see?

There are many rooms devoted to Comic-Con events, not to mention the various open-air booths and attractions set up in open spaces near the convention center. Room 25ABC is fairly large, but it’s considerably smaller than the Indigo Ballroom, 23ABC, and of course, Hall H. I was not alone in being puzzled as to why the panel “Fight Club: From Page to Screen and Beyond,” was scheduled in 25ABC at 7 pm on Saturday evening. Sure, the topic was an older film, and the panel was largely devoted to a forthcoming graphic-novel sequel to the story. Still, the participants included David Fincher, making his first Comic-Con appearance. I can only suspect that Fincher was a late addition to the panel’s line-up and it was too late to change the venue.

The result was that anyone determined to hear what Fincher had to say was bound to line up for the panels just before the Fight Club one and sit through them in order to see it. I decided to line up for “Disney’s Gargoyles 20th Anniversary” at 5 pm, having no idea what the Gargoyles are, and “Publishing 360: Building a Bestseller” at 6 pm, having no intention of trying to build a bestseller.

I got into a line that looked fairly short and was defined by lines of tape laid down on the carpets in the broad corridor outside 25ABC. It turned out to be one of those Disneyland-style ribbon-candy set-ups, where the line folds back on itself time after time, and you end up walking in one direction, turning around to walk in the opposite direction, only to realize that there is another group of people doing the same thing ahead of you in the same line. Fortunately most people seem to stick to the rules pretty closely, perhaps being aware of the wrath they would call down upon themselves by attempting to cut ahead of others.

I ended up about ten people back in line when the room was full. I never did learn what the Gargoyles were, but I suspected some people behind me had been hoping to get into that panel and were not there for the Fincher event. Indeed, as it became clear that no seats were going open up, a small number of people departed, leaving me about six people back from the front. It was looking good for me to get into “Publishing 360.”

At this point, from behind me I heard “Pardon me, but are you Kristin Thompson?” or words to that effect. Thus I met Ryan Gallagher, one of the stalwarts of The Criterion Cast, which describes itself as “A podcast network and website for fans of quality theatrical and home video releases.” (It is not officially associated with The Criterion Collection.) I recognized his name because he has sent many a reader to Observations on Film Art. Ryan’s latest podcast is a preview of Comic-Con, and I expect he will add one looking back on his experiences there.

What are the odds, I thought, and still think, that with 125,000+ visitors to Comic-Con, I would end up in line next to someone who recognized me? Turns out Ryan had been in line for the Gargoyles panel, so after a brief conversation, he departed. Eventually I was among the first into the room for the “Publishing 360″ panel, though there were people already there who didn’t leave, and I suspect the audience for Gargoyles doesn’t overlap all that much with the audience of people longing to write a bestseller. The procedure for building a bestseller, by the way, seems to consist primarily of getting the best agents and editors in the world. Aspiring writers, take note. Before the session began, I located an unoccupied electrical outlet and recharged my recorder. (This is a serious business at Comic-Con. The convention center is full of cell phones, tablets, and cameras dangling from outlets.)

The panel as pictured above consists of, from the left: moderator Rick Kleffel, Doubleday executive editor Gerald Howard, Fight Club author Chuck Palahniuk, David Fincher, and three artists and/or editors from Dark Horse Comics, which will bring out the Palahniuk-penned ten-part sequel starting in May, 2015.

A lot of the panel was about the graphic-novel sequel, of course. The main bit of new information about the film was that although it didn’t do particularly well at the box-office, Fincher finally got 20th-Century Fox to give him figures on how many DVDs were sold. Sales totaled around 13 million, so Fincher reckons the film must have made a profit in the long run. Probably the quotation from Fincher that will be remembered is: “My daughter had a friend called Max. She told me Fight Club is his favorite movie. I told her never to talk to Max again.” Fincher may not have been to Comic-Con before, but he knows how to please the fans.

Check out the Film website for an audio recording of the panel.

Hall H: Getting in

Hall H tends to draw much of the attention accorded to Comic-Con in the media. It’s the largest venue, with 6500 seats–including a large number reserved for representatives of the studios presenting publicity events there. That’s a big venue, but compared to the roughly 125,000 people attending the con each day, it’s not big enough. Although not everyone at Comic-Con wants to get into Hall H, most days the lines snake down and across the street, along the sidewalks. (A video moving along an entire Hall H line at a walking pace was posted on Youtube last year. It runs for over fourteen minutes, despite the fact that the people toward the front of the line are walking forward past the camera; if they were standing or sitting still, it would have run even longer.) In previous years the only way to guarantee getting into the hall for the first events of a day was to get there the previous evening and stay in line overnight. Short departures were possible if someone held your place, but basically you were there for the duration.

I was lucky enough to benefit from the innovation of a new policy on Hall H admissions. Color-coded wristbands would be handed out as the line formed, pausing at 1 am and resuming at 5am. The first portion of the line got a red band, with other colors for the next portions. The purposes were 1) the management could gauge how many people were lined up; 2) those in line could know whether they would get in or not; and 3) for the first time some people could leave for longer stretches of time than required for a rest-room break, as long as someone from their group with the same color wristband remained.

At least, that was how it was described in the online announcement. Those charged with distributing the bands and keeping order informed us that “a majority” of the group had to remain. To what degree that was enforced, we never learned. Fortunately that worked for Jonathan, Maria Elena, and I, since Rebecca had formed a “Hall H-line” group on Facebook and assembled a bunch of friends to camp out in line together. We adults, with our less flexible bones, departed for dinner and some sleep at our hotel. The next morning when we came to rejoin our group, the people in charge of keeping order asked if we had been to the rest room. Yes, we had. That and other things. Apart from everything else, the parking garage under the convention center has to be cleared after 10 pm, so the Kuntzes had to leave to get their car out. Clearly some clarifications of the guidelines are in order, but based on our experience the new wristband policy has improved the Hall H-line experience considerably.

The announced wristband-distribution schedule also had to be adapted. In the past, the Hall H line has started forming in the late afternoon or early evening, depending on the popularity of the first event scheduled for the following morning. Jonathan presciently went and got in line at 2:30 pm, and he was far from the first. Our party gradually grew as other members arrived, and inevitably groups ahead of us also swelled. Soon the line was very, very long. (A small portion of it is pictured above; the line had taken a U-turn a few hundred feet behind us, off right here.) Somewhere around 6:00 the wristbands started to be handed out, and small groups were escorted across the street to line up in the relatively luxurious area on the grass near the entrance to Hall H. There were white canopies overhead and the inevitable red plastic barriers dividing the area into rows approximately one reclining person wide. Those further back in line were less fortunate, having the sidewalk to call their bed. Our group of young stalwarts settled in for games, sleep, and an endless supply of trail mix and donuts. Rumor has it that anyone who arrived after about 9:30 pm didn’t get in. The last wristbands were handed out at around 2:30am. Presumably the handout did not pause at 1 am as planned, since clearly everyone who was going to get in when the hall opened was already there.

The next morning we received a call from Rebecca saying the group had been moved into the “chutes,” a process which had started at 7 am. These are slightly narrower strips of grass with the same plastic barriers; the chutes are opened one at a time, allowing the people in each to go in before the next chute is opened. More people are moved into the emptied chutes, and the process continues until the hall is full.

Although the handlers had said we would be let in at 9:30 for a 10:00 start, they got the process going at 9 am. By 10 we were all seated and ready for the Warner Bros. extravaganza to begin. There I am, wearing my vintage licensed Fellowship of the Ring T-shirt and the crucial pink wristband:

Expensive flash

Warner Bros. had two hours in Hall H on Saturday morning to promote their films. The full program is not announced in advance. People were assuming that The Hobbit: The Battle of Five Armies, as the biggest item on tap, would be saved for the end. That turned out to be correct.

The event started with curtains sliding back to reveal a long, panoramic screen on either side of the big central one. This surrounded about the front half of the audience in a U-shaped set of images. Warners installed these screens at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars; naturally no other studios were allowed to use them.

Some short presentations opened the program, beginning with Zack Snyder coming onstage. He introduced Ben Afleck, Henry Cavill, and Gal Gadot, none of whom spoke. We saw a very brief clip from Batman vs. Superman. The two lead characters’ first meeting had them glaring at each other with glowing eyes, white and red respectively. (Naïve me, wondering why if they’re both good guys, they don’t just join forces to fight evil.) My main impression was that Batman looks like he’s wearing a small tank turret on his head. The fans were apparently pleased with what they saw.

The moderator then introduced Channing Tatum, who stood below the screen as a montage of footage from Jupiter Ascending was shown. This made no impression on me, and I have no memory of it, except that the big action scene looked pretty conventional.

The event really got going with a much longer promotion with George Miller talking about Mad Max: Fury Road. This used the side panels to good effects (above). David and I have been fans of Miller and the Mad Max series ever since Mad Max II (aka The Road Warrior in the USA) appeared. It was a treat to hear him talk about the new film, though what he said is pretty much what he has said in other interviews: there’s little CGI in the film, he storyboarded the whole thing rather than writing a script, it’s an attempt to do a continuous chase sequence for an entire film, etc.

Miller presented a montage of quick scenes from the film. It looked good but familiar. There’s Max, chained up on the front of one of the villains’ vehicles, as were some of the captives in The Road Warrior. A lot of the minor characters recall those of the same film. The digital image looked brighter and sharper than the previous films–not necessarily a good thing, since the three first films were muted, conveying a sense that everything and everyone was coated with dust. Unseasonal rains in Australia forced the new film’s shoot to move to Namibia, which looks like it stands in for the Outback pretty well. We must trust that, just as the first three films were significantly different from each other, this fourth film will have a unique flavor not apparent in the footage shown.

This was, by the way, the second preview I’ve seen recently of a film that imitates the awesome (in the old and literal meaning of that word) dust-storm in this well-known National Geographic clip online. And why not, though CGI can never equal the real thing in this case.

Hall H for Hobbit

Quasi-Spoilers ahead:

The second half of Warners’ slot was given over to The Battle of Five Armies. An opening blast of music accompanied the appearance from left to right of a panorama of images from all three Hobbit films:

Even this fairly comprehensive view of the screens leaves out two or three images on the far right. The most revelatory of these shows Galadriel, Elrond, and Saruman at Dol Guldur, rescuing Gandalf. The panorama stayed up throughout the presentation. (A rather juddery pan around the whole things can be seen on Youtube.)

Steven Colbert, widely known as a devoted and highly knowledgeable Tolkien fan, MCed the panel, dressed in his costume from the third film, in which he has a nonspeaking bit part. He expressed his love for Tolkien and the films and showed the brief scene in which he appears. Then he introduced the impressive eleven-person panel Warner Bros. had managed to assemble:

From the left, Colbert, Peter Jackson, Philippa Boyens, Benedict Cumberbatch, Cate Blanchett, Orlando Bloom, Evangeline Lilly, Luke Evans, Lee Pace, Graham McTavish, Elijah Wood, and Andy Serkis

Of course, most of us couldn’t see them this clearly with the naked eye. Seated about a third of the way back in the auditorium, my view was as shown in the image at the top of this entry. Peter (that’s he in the lower left corner) looked mighty small in reality, but in Hall H three large screens magnify the proceedings for the crowd. (Similar video screens are used in the other very large auditoriums, notably the Indigo Ballroom.)

One highlight was the first screening of the long-awaited teaser trailer. This was released online two days later; the best place to see a large, sharp image that starts streaming almost instantly is on Peter’s Facebook page. I have to say that it looks pretty promising, apart from the continued presence of the distracting and tedious Azog and Bolg.

I won’t give a complete run-down on this panel, since a good video of it has been posted on Youtube (with the two screenings of the teaser trailer cut out). Much of it consists of typical star chit-chat. The most interesting thing said came from Peter. There has been considerable speculation among fans as to whether the filmmakers will stick to the book and let some characters die during the battle. Peter stated that the grim parts of the book are being retained and implied that several characters will indeed die. (This should mean that here will be much lamentation among the “hot Dwarves” aficionados.)

I won’t give a complete run-down on this panel, since a good video of it has been posted on Youtube (with the two screenings of the teaser trailer cut out). Much of it consists of typical star chit-chat. The most interesting thing said came from Peter. There has been considerable speculation among fans as to whether the filmmakers will stick to the book and let some characters die during the battle. Peter stated that the grim parts of the book are being retained and implied that several characters will indeed die. (This should mean that here will be much lamentation among the “hot Dwarves” aficionados.)

There has also been much speculation as to whether Peter Jackson or anyone else will be filming other adaptations of Tolkien’s work. This question wasn’t addressed during the panel, but the obvious answer is no. The production and distribution rights to The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings were sold by Tolkien and his publisher Allen and Unwin to United Artists in 1969. Rather than placing a time limit on the rights, as is customary, they sold them in perpetuity, and any control over the use of those rights forever passed out of the hands of Tolkien and subsequently of his estate. His son Christopher Tolkien has objected to the films that have been made, and he quite possibly will find a way to prevent any sale of film rights relating to the other books, even after his death. The Silmarillion, which takes place primarily in the First and Second Ages of Middle-earth, is, I think, virtually unfilmable. The most filmable single work, The Children of Hurin, is unremittingly grim and would be unlikely to attract any support within the industry. Apart from all that, Peter probably has no desire to prolong the franchise, either as a director or a producer.

In short, we have almost certainly seen the final “Middle-earth” presentation at Comic-Con. I’m glad I was there to see it. The franchise as a whole will undoubtedly have a presence at Comic-Con for years to come. Weta Ltd. has become a major force in the world of film and its future seems assured in a way that it did not a decade ago, when Peter Jackson’s projects were its main customers. Weta Workshop now has taken over making the collectible figures not only for Peter’s work but for other films, and it develops its own original projects for collectibles, television, and publishing. Its booth this year (below) was considerably bigger than the one I saw in 2008. (See the top image here.) It was doing very good business every time I passed by. The full-size Smaug head (above right) attracted considerable attention.

It’s still the case that the vast majority of Comic-Con attendees are not in costume.

All photos down to the one of George R. R. Martin, plus the two of lines for Hall H and the Smaug head on the Weta booth were taken by me.

My camera failed me during the Fight Club panel, so I have borrowed one from Anie Bananie’s Tumblr site, “David Fincher Stole My Life.” The photo of the panoramic screen with the Mad Max image is by Albert L.Ortega for Getty Images and illustrates the Variety story linked as “Warners installed …” in the second paragraph below it.

I mentioned that I was at the con with my friends Jonathan, Maria Elena, and Rebecca. Jonathan and Rebecca provided all the photos taken inside Hall H. (That’s Maria Elena’s TA James Shetty beside me in the green shirt.) Rebecca took the photos of the TORn panel, and Jonathan the ones directly above and below.

Many thanks to Jonathan for booking me a San Diego hotel room while I was in Egypt this past spring, and to Rebecca and her Facebook group for heroically camping out and holding our place in the Hall H line.

The San Diego Convention Center: an escalator’s point of view

Proof! and a minor mystery

DB here, sort of:

Even doggedly determined readers of this blog may not have seen the codicil to my infuriatingly long entry on The Grand Budapest Hotel. I revisit those remarks now, only because coming back from my trip to Yurrrp, I have evidence of a version that many cinephiles may not see. Here’s what I appended to the old post:

Flying here the other evening, I watched The Grand Budapest Hotel on the plane, just to see what adjustments might have been made. (“This film has been modified to fit this screen and edited for content.”) Surprisingly, the aspect ratios were all preserved. The cuss words were cut out, as was the fellatio shot (but not the guillotined fingers). The most startling change was that the painting of female sexual congress had become a big, blank white one in the Rauschenberg mold. Was it an alternative shot for the airline version, or was the naughty one digitally whitewashed?

Flying back, diligent film researcher that I am, I took a shot of the bowdlerized image. My questions remain. I could imagine it as an Anderson joke, but also as a default for a censorious post-production.

Caught in the acts

Kiss Kiss Bang Bang (2005).

DB here:

If you’re interested in how films tell stories, I think that you’re interested in several dimensions of narrative. Those include the story world (characters, settings, action), narration (how story information is parceled out as the film unrolls), and plot structure (the arrangement of parts).

Plot structure matters because a movie’s parts, like parts of a song or a symphony, help shape our experience. Just as a “curtain line” makes us return after intermission, a cliff-hanging climax to a TV episode makes us tune in next week–or click to continue, if we’re binge-watching. Accordingly, storytellers reflect on how to chop up and lay out sections of their plots. Novelists fret over chapter divisions, TV writers massage their scripts to allow for commercial breaks, and playwrights map action into acts.

The idea of act-structure has passed into commercial screenwriting as well. Just when that happened is hard to say, but certainly by the 1980s scriptwriters consciously broke their screenplays into big chunks. That trend was largely the result of Syd Field’s 1979 book Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting, although some of his points had been anticipated in Constance Nash and Virginia Oakley’s Screenwriter’s Handbook (1974). From these books came the idea that a feature film script had a three-act structure, measured by time segments (30 minutes/ 60 minutes/ 30 minutes). The prototype was a 120-minute film, with each script page running about one minute of screen time. Field fleshed the model out by noting that “plot points” at the ends of acts one and two turned the conflicts in a new direction. Although other writers argued for other templates, and Field’s model was refined (what’s the “inciting incident” in Act One?), versions of the three-act model still rule the international film industry.

Field presented his anatomy as an analysis of hit films like Chinatown and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. He suggested it as a template for a successful plot. As Field’s book gained prominence, his guidelines gave production companies an heuristic for triaging submissions. Now a story analyst could simply check pages 25-35 and 55-65 for turning points, and “incorrect” scripts could be discarded immediately. (But see P.S. below.) Through a feedback cycle, the Field model became a guide to both screenwriters and industry decision-makers. Inevitably, the whole thing got mocked. The day-by-day structure of Shane Black’s Kiss Kiss Bang Bang parodies Field’s scheme, and it closes with a self-conscious epilogue. “So,” says the narrator, “that’s pretty much that….”

To what extent, though, was the three-act structure employed in earlier eras? Field’s original edition drew its examples from current hits, but he implied that classics would display the same underlying architecture. Kristin, in Storytelling in the New Hollywood, claimed that four parts were more common than three, and she supported her analysis with examples from films from the silent era and the classic studio years.

But film analysis depends on your perspective. In any movie you can find patterns different from the ones I find, and each of us can make persuasive cases. It would be valuable to know whether American screenwriters in the studio system consciously worked with an act-based model. If they did, what assumptions did they make about the length and organization of each act?

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

Steven Price’s new book, A History of the Screenplay, surveys the practices of screenplay composition in America and Europe. It traces the early years of outlines and scenarios through the continuity script of the silent years, the sound screenplay, and postwar European models, up to the New Hollywood and contemporary standards. It’s a fascinating study and sure to set a benchmark in our understanding of the conventions of screenwriting. For the 1930s and 1940s in America, Steven shows that filmmakers used two formats, either the “master-scene” one or a format involving more explicit instructions about camerawork, lighting, and other aspects. But he finds little direct evidence that screenwriters of the studio era consciously applied a three-act structure.

For some time, I’ve held the same view. I couldn’t find any script draft broken into acts. Some veteran screenwriters admitted using a three-act model in plotting, but their testimony came long after the era. So, for instance, Philip Dunne says he used a three-act organization for his 1940s screenplays, but he makes the claim in an interview published in 1986. Billy Wilder says he “wrote [Charles Boyer] out of the third act” of Hold Back the Dawn (1941), but the remark comes in an interview given decades later. There’s always the possibility that older writers, newly aware of the Fieldian template, were projecting it backward onto their work—assuring us that they conform to contemporary standards, or even asserting precedence.

Similarly, we can’t rely too much on secondary sources. True, screenplay manuals, from at least 1913 onward, have recommended a three-part structure, purportedy corresponding to Aristotle’s idea that a plot must have a beginning, a middle, and an end. But this rests on a misunderstanding. As I’ve mentioned before, Aristotle isn’t talking of acts; ancient Greek plays didn’t have act divisions. And almost none of the manuals use the term “acts” to describe the parts.

Richard Brooks’ novel The Producer (1951), about a weak-willed executive trying to do the right thing, offers some hints along similar lines. He mentions that a screenplay should run to 120 pages, confirming the canonical length that Field proposes. Likewise, Brooks obliquely appeals to Aristotle.

Some poor sucker of a screenwriter has to create a beginning, a middle and an end, and all the dialogue.

Perhaps there’s an intentional irony in the fact that Brooks’ Hollywood exposé is itself broken into three parts, labeled “The Beginning,” “The Middle,” and “The End.”

Unlike many authors of manuals, Brooks was an established screenwriter, and we might expect his novel to refer to acts. It doesn’t. But Lewis Herman, a minor scribe with three screen credits (including Anthony Mann’s Strange Impersonation), does. His 1952 manual declares that a feature-length film is built upon “a three-act theme outline.” The context suggests that the Hollywood studios demand this as a step toward developing a full screenplay. Herman usefully illustrates the outline with a hypothetical example.

Still, manuals or novels aren’t ironclad sources for studio practice. Better would be contemporaneous evidence from memos, story conferences, and similar unpublished documents. Claus Tieber has done extensive research into such sources and has found no discussions of three-act structure. I’ve found a few, but they’re fairly sketchy.

Overseeing Casablanca, Hal Wallis told Michael Curtiz, “The Epsteins have agreed to deliver the film’s ‘second act’ the following day.” Darryl F. Zanuck mentioned the “last act” in correspondence about Viva Zapata! and On the Waterfront. Supposedly John F. Seitz asked Preston Sturges about the flashback structure of The Great Moment: “Why did you end the picture on the second act?” As I noted in an earlier entry, David Selznick’s papers record a story conference on Portrait of Jennie in which Jed Harris remarks: “The second act–he must get the picture back because that’s all he’ll ever have of her.” He adds that at this point the film “is about 1/3 gone.” This suggests that some practitioners thought of the parts as roughly equal in length. (Kristin’s model proposes that this was the case.)

It may be, of course, that three-act structure of some sort was so ingrained in studio writers’ habits that they didn’t have to discuss it explicitly. Field was addressing aspiring screenwriters who wanted inside knowledge, but as intuitive craft workers, the old contract writers wouldn’t be likely to spell out rigid rules about length and dramatic patterning.

Since corresponding with Steven for his book, I’ve found that one screenwriter explicitly invoked three-act structure in his working notes. And I’m embarrassed not to have noticed it earlier.

Coupling, recoupling, and Joe Breen

F. Scott Fitzgerald and Sheilah Graham.

NICOLAS: Marriage has its phases–its acts–like anything else. This is another act, that’s all.

F. Scott Fitzgerald, screenplay for Infidelity.

F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Hollywood career was mostly a fiasco. Thanks to temperament, a mentally disturbed wife, bouts of breakdown and alcoholism, and an implacable industry, he worked his way down the hierarchy to unemployment. From July 1937 to his death in 1940, he earned screen credit for just one film, Three Comrades (1938). He also started, but didn’t finish, the best Hollywood novel I know, The Love of the Last Tycoon (aka The Last Tycoon). I think it spells out some features of the Hollywood aesthetic with special vividness.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

In early 1938 Fitzgerald began a screenplay for MGM producer Hunt Stromberg (right). Given a title, Infidelity, Fitzgerald came up with a script centered on a dead marriage. What has turned happy young lovers into a polite, numb couple? An extended flashback shows that two years earlier the husband Nicolas re-met his former secretary while his wife Althea was abroad taking care of her sick mother. The secretary, Iris, spent one night at Nicolas’ luxurious home, and it’s implied that they had sex. At breakfast, Althea returned home unexpectedly and found Iris at breakfast. After this, Althea remained married to Nicolas, but simply lived with him in detached ennui.

Back in the present, to ramp up his mood, Nicolas decides to hold a party in the country estate he had more or less abandoned. At the same time, Althea rekindles her friendship with a former suitor, Alex. She can’t arouse herself to passion, though, and Alex leaves her. As she drives more or less hysterically to the estate where the party is in full swing, Nicolas is wandering through his mansion among the shrouded furniture.

At this point, because of objections from the Production Code office, Stromberg halted Fitzgerald’s work on the screenplay. Aaron Latham’s biography tells us that Fitzgerald had planned to present a reconciliation, in which a photographic trick presents Althea seeing herself as Iris and thus forgives Nicolas. But this ending would suggest that the husband’s sin went unpunished. Fitzgerald suggested an alternative, but this too was rejected by Joseph Breen. He tried to redraft the script later in 1938, but the project dissolved.

Fitzgerald had systematically studied Hollywood releases, even filing plot synopses on index cards. Accordingly, the Infidelity screenplay we have shows an awareness of 1930s storytelling conventions: montage sequences, wordless scenes, and revealing visual detail. We learn that Nicolas’ ardor is cooling when we notice that he has stopped opening Althea’s letters. Fitzgerald’s acquaintance with current trends led him to a thumbnail characterization of Althea’s friend Alex:

He is the type played by Ralph Bellamy in The Awful Truth–handsome, attractive, worthy, thoroughly admirable, but somehow too heavy in manner to grip the sympathy of an audience if playing opposite a man of charm.

Occasionally, voice-over dialogue in the present is matched with images in the past, in the manner of Sturges’ “narratage” in The Power and the Glory. (See our entry here.) And the large-scale flashback structure, leaving a key action in the present suspended for nearly an hour, anticipates a mode of construction that would be common in the 1940s.

Despite its up-to-date air, the plot of Infidelity creaks a bit. It relies on a great many coincidences and introduces rather late a major menace, a sinister surgeon who seems slated to play the disruptive role of George Wilson in Gatsby. But what’s of special interest to us is a schedule of work that Fitzgerald sent to Stromberg during the planning stages.

Fitzgerald groups his scenes into clusters, and alongside each one he notes a date on which he expects to complete it. Since each scene usually runs only a couple of pages, the groupings present a feasible day-by-day timetable. These clusters of scenes are gathered into eight “sequences,” labeled with Roman numerals. In the 1930s, a “sequence” meant, according to screenwriter Frances Marion, “a series of scenes in which the action is continuous without any break in time.” Each of Infidelity‘s sequences presents a unified phase of the action and is more or less continuous in time, although there are some ellipses as well.

Here’s the news: Fitzgerald’s timetable assembles the sequences into acts. Sequences I through IV are labeled “FIRST ACT 45 pages.” Sequences V through VIII are labeled “SECOND ACT 50 pages.” Sequence VIII is continued to form “THIRD ACT 25 pages.”

The first act establishes the loveless marriage and launches the flashback. While Althea is away, Nicolas re-encounters Iris. Meanwhile, as Althea and her mother are on their way home, they conveniently run into her old beau Alex. Their departure for the United States ends this setup. In the screenplay Fitzgerald has typed: “The First Act may be said to end here.”

The second act develops the conflict to a point of crisis. Althea returns a week early to find Iris at breakfast with Nicolas. She resigns herself to a loveless union. Back in the present, he plans the party and at the instigation of Althea’s mother Alex starts to woo her. But he abandons Althea, and by chance she’s found by Dr. Borden, whom she starts kissing. In the notes for Sequence VIII, Fitzgerald cryptically ends the act on an alternation between the couples:

CUT TO husband and back to old beau [Alex]

[Alethea] with beau [Alex]

Crisis with beau and switch [to the surgeon, Dr. Borden?]

CUT TO husband

After presenting this alternation in scenes, the manuscript concludes:

Full shot of a bedroom, large and luxurious like everything else in this house. Soft lighting, everything covered with cloth or canvas.

Nicolas Gilbert is standing in the middle of the floor.

Close shot of Nicolas.

This is presumably the end of the passage labeled “CUT TO husband.” In the Stromberg schedule, this last portion marks the end of Act Two. Act Three isn’t in the canonical version of the screenplay.

A couple of final points about the structure. Although the screenplay is estimated at 120 pages, its proportions don’t conform to the Field paradigm. At 25 pages or minutes, the third act is short. This is a characteristic of both modern and older Hollywood climax sections. But Act One was projected to be very long at 45 pages, and Act Two approximates it at 50. Fitzgerald’s layout is perhaps more characteristic of a stage play, which can afford a longish exposition and equivalent second act. In the script version we have, both acts run equivalent page lengths.

Fitzgerald may have expected some trimming and compression at later stages. In The Producer, Brooks’ protagonist notes that a 120-page script would usually be cut down to 90 minutes because exhibitors wanted films at about that length. It’s true that few films of the studio era run to two hours.

Set aside brute measurements. What, in Infidelity, makes an act a coherent unit? Not a specific span of time. Act One breaks off partway through the flashback, and Act Two ends before the evening party does. The first act ends when we know a crisis is coming: Althea is returning home early and hasn’t told Nicolas, whom we’ve seen flirting with Iris. Act Two ends at another high point. Nicolas confronts the emptiness of his life without his wife, and nearby Althea is heedlessly making love to a stranger with dubious designs. We could easily imagine the script as a stage play, with a curtain ringing down on each of these teasing situations.

In sum, we have one clear-cut case of a studio screenwriter laying out his plot in three acts. We can’t generalize from a single instance, of course, and we would need many more pieces of evidence to consider this a widespread writing strategy. Perhaps Fitzgerald isn’t typical. Did his relative inexperience as a screenwriter make him rely on a theatrical template that others could do without? Did he employ it more as a rhetorical device to convince Stromberg that the plot was firmly constructed? Still, taken with the reminiscences of Dunne, Wilder, et al. and the sketchy mentions we have in production records, the Infidelity project suggests that some conception(s) of three-act structure were operative in the studio period.

Needless to say, we’ll need even more evidence before we can begin to consider whether the filmmakers’ craft practice matches the structural patterns that today’s analysts disclose in the films. The search continues!

The Fitzgerald outline is reproduced on pp. 161-162 of Aaron Latham, Crazy Sundays: F. Scott Fitzgerald in Hollywood (Viking, 1971). This book is not only a stimulating account of the novelist’s Hollywood years but also a helpful view of the movie colony’s culture. My discussion relies upon the version of Infidelity published in Esquire 80, 6 (December 1973), 193-200, 290-304. It is available in a digitized version here. The original manuscripts are in the University of South Carolina library.

Philip Dunne’s remarks about three-act structure are in Pat McGilligan, Backstory (University of California Press, 1988), 158. Billy Wilder’s remarks come in George Stevens, ed., Conversations with the Great Moviemakers of Hollywood’s Golden Age (Knopf, 2006), 316. (In the same interview Wilder claims that Some Like It Hot has four acts.) Richard Brooks’ The Producer (Simon & Schuster, 1951) is worth reading for its almost documentary survey of the process of production at the period. Lewis Herman’s Practical Manual of Screen Playwriting for Theater and Television Films (World, 1952) is an unusually detailed guidebook.

On Wallis’ memo about Casablanca‘s second act, see Marshall Deutelbaum, “The Visual Design Program of Casablanca,” Post Script 9, 3 (Summer 1980), 38. For Zanuck’s comments see Memo from Darryl F. Zanuck: The Golden Years at Twentieth Century-Fox, ed. Rudy Behlmer (Grove, 1993), 173, 226. Seitz’s remark to Sturges about The Great Moment is quoted in James Curtis, Between Flops: A Biography of Preston Sturges (Harcourt, Brace, 1982), 172. There’s more discussion in our blog entry on The Great Moment.

I take Frances Marion’s definition of “sequence” as a bundle of scenes from her How to Write and Sell Film Stories (Covici-Friede, 1937), 373. Tamar Lane offers a comparable definition in his New Technique of Screen Writing (McGraw-Hill, 1936), 123. Interestingly, Lane adds that some scenarists think of each sequence as moving toward a high point, like an act in a play; but this seems only a rough analogy, and the comparison entails that a script would have several more “acts” than three. Steven Price suggests that the “sequence” as an extended script segment emerged in the silent period and hung on in some sound screenplays; see A History of the Screenplay, especially 63, 115-116, and 153-157. At the same time, “sequence” could refer to a single brief segment, as in “action sequence” or “montage sequence.”

Thanks to Steven Price and Claus Tieber for correspondence about act structure. Claus has a relevant case study of Grand Hotel, “‘A Story Is Not a Story But a Conference’: Story Conferences and the Classical Studio System,” in Journal of Screenwriting vol. 5, no. 2 (2014): 225-237. More generally, I’m grateful to researchers at the Screenwriting Research Network for what I’ve learned from their conferences in Brussels in 2011 and in Madison in 2013.

Other entries on this site have considered act structure. Kristin explains her model, based on goal formulation and injections of new information. She expands on this as it affects character subjectivity and point of view. I illustrate her model with reference to what is supposedly the most wayward and narratively fragmented modern genre, the action picture. I offer some general reflections on how the four-part structure informs not only current films but best-selling novels. For a more general discussion of the dimensions of film narrative, you can download this chapter from my Poetics of Cinema. Also, too: there’s the precept that form follows format. Finally, I consider modern trends in screenplay construction, including act structure, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

After a while you see the triplicate scheme everywhere. In Case History of a Movie (1950), p. 30, Dore Schary says that Charles Schnee turned in the script of The Next Voice You Hear in thirds. Acts? I’ll have to get back to you.

P.S. 19 May 2014: In reply to this post, Greg Beal comments that my discussion of rejecting screenplays based on Field’s plot points is inaccurate.

My claim was, I now think, an overstatement. I should not have suggested that the absence of canonical plot points would be sufficient to doom a screenplay. Naturally, I realize that the analyst would still be obliged to write fuller coverage. I meant simply that the Field template could set up expectations that the script wasn’t written to standard. Other factors would surely be taken into account in a final decision. The larger point, that three-act structure along Field’s lines shapes analysts’ judgment, remains to be determined.

My most concrete evidence for the saliency of the three-act, plot-point model in this production context comes from two manuals by story analysts. T. L. Katahin’s Reading for a Living: How to Be a Professional Story Analyst for Film and Television (Blue Arrow, 1990) recommends that analysts look for three acts, including a ten-page initial setup followed by a development and two further acts that forward the protagonist’s goals. But Katahin doesn’t propose exact page counts for further twists.

More specific is Jennifer Lerch’s 500 Ways to Beat the Hollywood Script Reader: Writing the Screenplay the Reader Will Recommend (Simon and Schuster, 1999). In following the three-act layout, she suggests that Act One, the setup, be consummated between pages 20 and 30 (ideally consisting of two scenes 10-15 pages each). Act 2, as per Field, is said to run long, up to pages 80-90, and typically consists of four to eight sequences (each 10-15 pages or so). This act is said to lead to a point of no return, the pivot-point for Act 3.

Lerch, who was a professional story analyst for the William Morris Agency for eight years, claims, “Your script’s setup can literally make or break your project in the Hollywood Reader’s eyes, particularly at some companies that instruct readers to stop at page thirty of a script if it looks substandard. You may have a great second act and climactic sequence, but Hollywood will never see it unless you give it a savvy setup” (91). Passages like this one led me to think that the Field template weighs quite strongly in analysts’ judgment. But I’ve never supervised story analysts, so I welcome Greg’s expert comment on the matter.

P.P.S. 20 May 2014: More information on Fitzgerald’s Infidelity screenplay and its act breaks. In a letter to Hunt Stromberg dated 22 February 1938, Fitzgerald wrote:

The first problem was whether, with a story which is over half told before we get up to the point at which we began, we had a solid dramatic form–in other words whether it would divide naturally into three increasingly interesting “acts” etc. The answer is yes. . . .

This point, the decision to sail, also marks the end of the “first act.” The “second act” will take us through the seduction, the discovery, the two year time lapse, and the return of the old sweetheart–will take us, in fact, up to the moment when Joan [later, Althea] having weathered all this, is unpredictably jolted off her balance by a stranger. This is our high point–when matters seem utterly insoluble.

Our third act is Joan’s recoil from a situation that is menacing, both materially and morally, and her reaction toward reconciliation with her husband.

Evidently the timetable reprinted in Crazy Sundays was prepared after this letter was sent. This letter is printed in F. Scott Fitzgerald: A Life in Letters, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli (Scribners, 1994), 348-349.

P.P.P.S. 30 May 2014: I always enjoy getting correspondence from readers, and I must catch up by noting some other responses I’ve received. David Cairns, whose wonderful blog Shadowplay is always worth checking on (his latest post is on Hannibal, the TV show), writes with this comment:

Hold Back the Dawn (1941).

Back in THE Place

View of Hong Kong harbor from the Convention and Exhibition Centre. Above, the flag of the People’s Republic of China; below, the Hong Kong flag bearing the Bauhinia emblem. According to official protocol the national flag must be larger and be mounted more prominently.

“For us, Hong Kong will always be the place.”

Chuck Norris, The Octagon (1980)

DB here:

After missing two editions because of some minor health problems, I’m back in Hong Kong for their annual festival. As customary, it kicked off with the Filmart, now the biggest film market in Asia. It gathers producers, distributors, and financiers for discussions and dealmaking. There are panels, equipment demos, and displays of media items for sale. There’s the Hongkong-Asia Film Financing Forum, a competition that funds planned projects. (This year’s winners are here.)

Some booths are huge. The TVB display was towering, dwarfing the TV chat show being shot underneath.

Since its founding in 1997, Filmart has been so successful that it spawned an umbrella event. The Hong Kong Entertainment Expo, now in its tenth year, is a jamboree for the international entertainment industry, including music and digital entertainment of all sorts.

Filmart is now very big. This year it packed in over 760 exhibitor stalls from over 30 countries (including Brunei and Malta). It attracted over 6500 attendees, and most, unlike me, were there to buy and/or sell films, TV shows, and video games.

National film organizations use Filmart to coax production into their territory. Government agencies like KOFIC can put producers in touch with prime locations and service firms.

The opening reception was graced by Chief Executive C. Y. Leung, who while extolling the rule of law in the territory did not mention the recent violent attack on a major journalist. A characteristically blank-faced Leon Lai looked on. In the crowd, you might also meet Bruce Lee, or at least his avatar.

On the market floor, a Chinese vampire squared off against Donnie Yen, immortalized by Madame Tussaud.

Who would win in a face-off? The movie is probably being shot as we speak.

China ahead

Out of Inferno (2013).

The big news this year was, as ever, mainland China. By any measure it just keeps growing. Back in 2012 it became the world’s second-biggest market, yielding $2.74 billion in box-office grosses. (US and Canada were at $10.8 billion.) In 2013 Chinese grosses were $3.6 billion, a growth of 25%. (North American grosses grew only about 3%.) In tandem, the number of exhibition sites expanded hugely. China added over 5,000 screens in 900 new multiplexes, yielding a total of 18,195 screens. That is still remarkably few for such a populous country; North America has over twice that number. So we can expect still further growth. More generally, another sign of the times was that last year Asia-Pacific became the most lucrative region outside North America, and of course China is the centerpiece of that.

You see the China syndrome in the films as well. For several years Hong Kong producers and directors have partnered with mainland talent and business groups. Two of last year’s best Hong Kong films, Johnnie To Kei-fung’s Drug War and Wong Kar-wai’s Grandmaster, epitomize cross-border initiatives, mixing HK and PRC stars in stories that hold appeal for both audiences.

A new wrinkle: Now even films that might seem purely of Hong Kong interest credit major Chinese companies as coproducers, and they may feature mainland stars. Tim Youngs, local HK film expert, suggests that because some big-budget Chinese films haven’t succeeded in Hong Kong, mainland investors may be interested in financing small films that will catch on in the territory.

Yet some films persist without mainland financing. An example I saw at Filmart is the modest indie Dot 2 Dot, by first-time director Amos Why.

The story is rooted in local history and geography. Chung, returning from Canada to take a job in a design firm, recalls how much he enjoyed connect-the-dots puzzles as a boy. Now he discreetly puts up speckles on walls, marking sites that were significant to him and his city. Xue, a young teacher, discovers them, puzzles them out, and draws out the abstract patterns that Chung embedded in them. When he spots her graceful graffiti he determines to find who has cracked his code. What gives the story contemporary currency is the fact that Xue has emigrated from the mainland and is teaching Mandarin to Hong Kongers, and she is played by Meng Tingyi.

Dot 2 Dot interrupts its lovers-at-a-distance plot with images from Hong Kong’s past. Xue’s supervisor, an elderly teacher, and Chung, a nostalgia buff who treasures his childhood comics, recall moments in local history, such as when the Daimaru department store closed after a gas explosion. The émigré Xue, in finding her way around this imposing city, comes to appreciate its past. Eventually we learn through a degrees-of-separation device that both Chung and Xue have shared Hong Kong kid culture–two dots, in effect, waiting to be connected in adulthood. Those interested in allegory could see here a claim that for decades, China’s modern popular culture has been imported from Hong Kong, and that fact fosters cross-border bonds.

On a bigger budget there are other more or less “pure” Hong Kong films–in tone and genre, despite mainland backing–being made. Even the cockeyed English title Out of Inferno (2013) brings back the 1980s and 1990s, as does the premise. Two brothers dedicated to firefighting fall out; one (Lau Ching-wan) becomes obsessed with his job, the other (Louis Koo) leaves to form a company specializing in modern fire-protection equipment. When a skyscraper catches fire during a party demonstrating the equipment, Koo and Lau’s pregnant wife, along with many others, are trapped inside. The brothers must reconcile, inside and outside, to save innocent lives. In short: Towering Inferno + Backdraft + Johnnie To’s Lifeline. Indeed, certain shots and the very presence of Lau Ching-wan, recall To’s genre masterpiece. So what’s new? Well, it’s set in Guangzhou and it’s in 3D.

Out of Inferno comes to us co-funded by the HK company Universe and the mainland company Bona. It grossed about US$2.6 million in Hong Kong and over $20 million in China, which says all you need to know about the relative power of the two markets.

Nobody I respect seems to like this movie. Most critics have written off the directors, the brothers Danny and Oxide Pang, as hacks. Kozo’s review at LoveHKFilm states the case against. Granted, the film is routine in many ways and can’t match Lifeline, but I enjoyed its almost unceasing bursts of clear, cogent action. I began to realize that one benefit of a firefighting movie is that rooms can explode, ceilings and floors can collapse, and elevators can stop or plunge–at any time, whenever you something to goose a scene. After all, it’s a fire, right? Who can predict what a fire will do? In 3D, many shots were splendid, and I will watch Lau Ching-wan doing sullen integrity in nearly anything. Still, Tim Youngs alerts me (so I alert you) to another action-filled firefighter movie, As the Light Goes Out–not screened at Filmart, not yet available on disc, and with more admirers, at least in my vicinity, than Out of Inferno.

A future for Retro

The White Storm (2013).

Universe and Bona, who seem to team up for blockbusters, offered a more delirious example of the Hong Kong flavor in The White Storm, which also screened at the Filmart. It’s another exercise in mixing. We have Bullet in the Head: three boyhood friends undergo a harrowing trip to wilder Asia, expending much sweat and tears, and even more blood. We have Infernal Affairs too, with the deadly game of undercover work and the possibility that a Triad mole has infiltrated the police. The three buddies consist of the familiar pairing of Lau Ching-wan and Louis Koo, along with the ever-dependable Nick Cheung as the apparently weakest member of the trio.

Unusually long at nearly 140 minutes, The White Storm (the title refers to the heroin plague that has descended on Hong Kong) is really three movies in one. The first centers on Koo in the now-familiar role of the cop who wants to come in from the cold. After a frantic drug bust gone wrong, he’s forced to return to the underworld and lead his comrades to a Thai kingpin. The second stretch takes place in Thailand. There after a savage assault on the dealer’s compound, our three are captured. The dramatic weight shifts to Lau, who must choose to kill either Koo or Cheung. His decision gains complexity because we know something he doesn’t about his partners’ loyalty. The film’s last portion returns to Hong Kong, with a few surprises and a bloody casino finale.

While building suspense in the Infernal Affairs mode–will the gang discover the mole in their midst?–director Benny Chan also tries to recover the searing romanticism of Woo’s heroic bloodshed films. As far back as The Big Bullet (1996) he showed a flair for shocking, precise action, and his Jackie Chan vehicle New Police Story (2004) is an exhilarating piece of work. Benny Chan shows his skill in each of the three sections’ violent set-pieces. Add in the 1980s-1990s Hong Kong excess–bodies thrown into pools of crocodiles, a sexy transsexual, outrageous haircuts–and you have an almost purely retro exercise.

Another throwback is the shameless but stirring tear-jerking moment in which the three men comfort Cheung’s dying mother. She thinks that Lau is her son, back from study abroad with his buddies. They spontaneously accept her delusion, each pretending to be another member of the trio. The film’s play with false identities turns melancholy, and in comforting her the men apologize, obliquely, to one another. Chan’s use of singles and two-shots deftly traces out the flow of feeling, as the men exchange glances and Cheung starts to weep in shame.

The old Hong Kong cinematic energy resurfaced in another, stranger film, Fruit Chan’s new release The Midnight After. It’s based on a popular internet novel by Pizza (yes, you read that right). The premise is apocalypse, the time is now. A minibus driving from downtown Hong Kong to the New Territories passes through a tunnel and emerges into an urban landscape from which everyone seems to have vanished. A mass extinction? An evacuation? A time warp? The mystery deepens after we get an occasional glimpse of dark figures in protective gear monitoring the frantic efforts of the survivors to make sense of their fate. Some of the passengers die–crumbling to bits, suffering giant boils, bursting into flame. Even a compassionate bicyclist is drawn into the desperate struggle for survival.

A Hong Kong director often asks us to take his or her film as reflecting a general mood in the territory. Fruit Chan says:

It feels as though Hong Kong is suffering the worst of times. People’s lives, people’s businesses and the political climate are all seriously depressed. The impact hit us harder than anything else in the past century. Through The Midnight After I’d like to tell the est of the world something about the problems that Hong Kong faces in this period of social upheaval.

The tone, as well as the plethora of familiar landmarks, may give the film some local resonance. More broadly, the film also joins a tradition of horror-fantasy that hearkens back to classic Hong Kong movies about the supernatural and even dystopian exercises like The Wicked City (1992). The latter was rendered with typical Tsui Hark brio, though, and The Midnight After is more sober and straightforward, at times perilously close to flat. Nor does it have the conciseness and growing creepiness of Chan’s Dumplings (2004).

I didn’t find The Midnight After particularly compelling. The characters are viewed from the outside and don’t solicit much sympathy; they’re mostly collections of types and tics, including a mysterious young woman who is given I-may-be-a-demon treatment by the expedient of momentarily billowing hair. As usual when a Cantonese film doesn’t know what else to do, it sets its characters screeching, quarreling, running around, and punching. Moreover, I couldn’t figure out what made the unfortunate victims die in different ways. And what’s behind the mysterious watchers? My friends say: “There aren’t any rules.” Maybe they’re right. But it’s fairly easy to pile on mysteries in your plot; the task is to tie them up in the end.

To be fair, we don’t really have the end. The film adapts only the first part of Pizza’s cybernovel, so perhaps everything will get straightened out in a sequel. What matters, for better and worse, is that many Hong Kong filmmakers still resort to Reboot mode.

You can read the trade papers’ Filmart daily publications here. Also visit Film Business Asia for many articles on deals announced at Filmart. Peter Martin reports on a panel on the Asian industry at Twitchfilm. Perhaps most important, Patrick Frater of Variety signals an important upcoming change in PRC distribution policy.

My information on the 2013 growth in Chinese screens is gleaned from David Hancock’s survey in of world exhibition in IHS Media and Technology Digest no. 504 (September 2013), 9-12. Additional information comes from Jeremy Kay’s CinemaCon report in Screen International and Patrick Frater’s account of screen expansion in Variety. Derek Elley offers a very thorough analysis of the contemporary Chinese industry in “Mainland Cinema’s New Maturity,” in Film Business Asia.

The trailer for Dot 2 Dot is here. Kozo, as you’d expect, has a nuanced review of The White Storm.

In other welcome news related to The Place, Grady Hendrix is back with Kaiju Shakedown. The inital entry is a full-blooded overview of the career of mystery auteur Jeff Lau.

P.S. 1 April 2014 (HK time): This entry has been revised to correct my original claim that Dot 2 Dot had some financing from the mainland. Director Amos Why wrote to explain that despite the credited participation of two companies based in Beijing, there was no investment from Chinese sources; the funding came entirely from Hong Kong. I thank Amos for the correction.

Smoke from a towering inferno? The creeping miasma of The Midnight After? No, just a low-lying cloud settling on Central after a rainstorm.