Archive for the 'Experimental film' Category

Catching up with the past: Recent DVD and Blu-ray releases

Behind the Door (1919).

Kristin here:

David and I have moved house recently, which has caused a long lag in my getting around to doing a DVD/Blu-ray roundup of recent releases. Some are not so recent anymore, but I shall call attention to them nonetheless.

Behind the Door (1919)

Our friends at Flicker Alley have been busy, as usual.

Way back in February of last year, they released Behind the Door, a notoriously grim and brutal drama of World War I that long survived only in incomplete form. Using tinting rolls from the Library of Congress, some scenes from star Hobart Bosworth’s collection, and a re-edited Russian distribution print, as well as a copy of the continuity script, the restoration by the San Francisco Silent Film Festival, the Library of Congress, and Gosfilmofond approximates the original American release version fairly closely. (Two brief missing sections are filled in by photos and the texts of the original titles.) The tinting and toning, based on the Library of Congress material, is authentic and effective (see top), as is the new score by Stephen Horne.

The Russian version is included in the two-disc set, so we have one of those rare cases where it is possible to compare the foreign and domestic versions–to a degree. Most of the shots, of course, were made with a second camera, and there are inevitably differences of framings and even takes between those versions. Given that the new restoration depends heavily on the Russian print, the comparison must be made primarily on the basis of the differences in the order of the scenes and the other narrative changes made by the Russian editors.

Behind the Door tied for Best Single Release in Il Cinema Ritrovato’s DVD Awards, announced just last month. Congratulations to Flicker Alley and to other organizations we have ties to, which also won awards. The Criterion Collection tied for Best Box Set for its 100 Years of Olympic Films: 1912-2012. This massive set (32 discs on Blu-ray, 43 on DVD) contains 53 films, including those by Leni Riefenstahl, Kon Ichikawa, Claude Lelouch, Carlos Saura, and Miloš Forman. Belgium’s Cinematek won Best Discovery of a Forgotten Film for its Marquis de Wavrin (1924-1937), actually a series of films shot in South America by this major anthropologist and filmmaker. German Concentration Camps Factual Survey (from the BFI and the Imperial War Museum), which David commented on last year, won Best Special Features.

Das alte Gesetz (1923)

I have a particular interest in German silent cinema of the post-World War I era, so I was happy to see Flicker Alley’s release of Ewald André Dupont’s Das alte Gesetz (“The Ancient Law”). Most people know Dupont only from his most famous and successful film, Variety (1925), known for its spectacular camera movements taken from trapezes.

Dupont had a long career, however, starting as a scriptwriter in the 1910s and becoming a director as well in 1918. Das alte Gesetz is mainly known as one of a small group of Jewish-themed films made in Germany in the period 1919-1924. More familiar to most would be Der Golem:Wie er in der Welt kam, co-directed by Paul Wegener and Carl Boese (1920) and to some, Die Gezeichneten, Carl Dreyer’s first German film (aka Love One Another, 1922). A helpful essay in the accompanying booklet by Cynthia Walk gives the political context of die Judenfrage (“the Jewish question) as it was being debated in Europe at the time.

Set in the 1860s, the film concerns Barush, the son of a rabbi in a shtetl in western Russia. He suddenly and somewhat implausibly conceives a desire to leave home and become a famous actor. Naturally his father disowns him. Joining a small traveling troupe, Barush ends up in Vienna, where an archduchess, played by Henny Porten, is impressed by his performance as Romeo and attracted to him as well. She arranges for him to join her court-theatre troupe, where he becomes a star as a classical actor.

The scenes in the shtetl (above) are done with considerable attention to authenticity and without the sort of ethnic humor that one might expect. Although Barush encounters prejudice in Europe, he does not evenually learn a lesson about assimilation and go back to his home with his tail between his legs. Far from it; his father is induced to read Shakespeare and suddenly realizes that there are indeed more things in heaven and earth than he had dreamed of in his philosophy. A happy reunion results, and Barush continues his career.

Das alte Gesetz was clearly a big-budget period piece, with several large sets. Moreover, the influence of classical Hollywood films, which began to be shown in Germany in 1921, is quite apparent. Dupont has mastered three-point lighting and analytical editing, including shot/reverse shot, as this scene between Barush and his father demonstrates.

Barush is played by Ernst Deutsch, a major actor of the day, including in Expressionist films. He’s the rabbi’s son in Der Golem as well, and he plays the bank-cashier protagonist in Karl-Heinz Martin’s From Morn to Midnight.

MOD

Flicker Alley has also developed a healthy list of manufactured-on-demand titles. Many of these are out-of-print films from the Blackhawk Collection. The 51 titles currently on the list include many silent classics, some of them difficult to see on disc otherwise, such as Lubitsch’s The Marriage Circle and Abram Room’s Bed and Sofa.

The new offerings lately have branched out somewhat to include more recent films. On September 3 of last year, the company released Alex Barrett’s London Symphony (2017) for its home-video debut. In the press release for the disc, the director describes it as “a love letter to a city, but it is also a film about life in the modern era.” As the title indicates, Barrett places his film in the city symphony genre, and its release was timed to coincide with the 90th anniversary of the premiere of Berlin: Symphony of a City. City symphonies tend to be associated with the 1920s, when the genre originated and its most famous exemplars, Berlin and Vertov’s Man with a Movie Camera, were made. The genre has never disappeared, but Barrett has written that he chose “to make the film in a style associated with the filmmakers of the 1920s.”

For me, it captures well the style of the 1920s, and particularly Berlin. Shot in black-and-white, London Symphony falls into four movements, following a day in the life of the city–with, as in Berlin, pauses for lunch and dinner particularly dwelt upon. The opening section concentrates on buildings, and there are the inevitable juxtapositions of old and new (see bottom). Multiple cinematographers filmed the footage, but their work blends into a unified visual whole with many striking compositions.

Ruttmann injects occasional implicit political commentary, as when he juxtaposes shots of beggars in the streets with the well-fed Berliners in restaurants. Barratt concentrates on the beautiful and peaceful side of London–historic buildings, quiet parks, pleasant markets, and river scenes. The rather grubby and crowded atmosphere of, say, the West End of London is nowhere to be seen, which befits “a love letter.”

In January The Indomitable Teddy Roosevelt joined the MOD catalog. This is a reissue of a 1983 television documentary that mixes documentary footage (Roosevelt was the first president to be filmed) and staged scenes.

Edition Filmmuseum

This series continues its steady release of experimental filmmaker James Benning’s works with a sixth two-disc set (DVD only) that goes back to his earliest features, films that solidified his international reputation. The new two-disc set contains two films from the late 1970s, 11 x 14 (1977) and One Way Boogie Woogie (1978). Jim followed up the latter, a series of sixty shots of Milwaukee cityscapes, with 27 Years Later (2005), which presents the same series of locations, and One Way Boogie Woogie 2012, which further documents the changes in the filmmaker’s hometown. All three films are included in this set.

11 x 14 flirts with presenting a narrative without ever really concentrating on it. We see some of the same people at intervals, but no causal events link them, and their actions create situations rather than developing stories. Instead, the film’s shots, some quite lengthy, others brief, explore the urban and rural landscapes of Chicago and Milwaukee, as well as rural roads and fields in the surrounding area. (A familiar highway sign pointing the way to Madison is glimpsed at one point.)

For the most part the urban images concentrate on run-down areas, with motifs of travel (billboards, airplanes) and drinking (bars and more billboards) hinting at contrasting modes of escape. The shot above captures both motifs at once.

Given that Jim’s films seldom play outside festivals and museum venues, the Filmmuseum series is vital–though many of the images in these films are long or even extreme long-shots and benefit from being seen on a big screen. The last time we had a chance to do so was when RR (2007) was shown at the 2008 Vancouver International Film Festival. The Austrian Filmmuseum also published a book on Jim’s work, which David discusses here.

London Symphony (2017)

Barely moving pictures: Kiarostami’s 24 FRAMES

24 Frames (2017).

DB here:

It might seem an act of vandalism. To overwrite one of the world’s most famous paintings, the elder Pieter Bruegel’s Hunters in the Snow, with digital effects could be condemned as vulgar at best and scandalous at worst. In the lower left, we see a dog pissing on a tree. Yet no one ever accused the late Abbas Kiarostami of bad taste. Of weirdness, yes: His Lumière tribute (1995) consisted of a close-up of a frying egg.

Eggs aside, Kiarostami’s experiments mostly have a stubborn stringency. He made a film wholly out of reaction shots, and another out of static takes of landscapes. Yet neither was an arid exercise. Shirin (2008) yielded poignancy as it let us study women responding to a romantic spectacle (film? theatre piece?). The minimalist Five Dedicated to Ozu (2003) was at once meditative and sensuous, speckled with moments of relaxed humor (the parade of the ducks) and building to a curious suspense, as we stare at brackish water trembling in a downpour.

So when the first segment of Kiarostami’s 24 Frames (2017) decorates Bruegel’s masterwork, we ought to expect that something’s up. The explanation offered in the film’s prologue is that the filmmaker is curious about what happens around the instant portrayed in the image.

For 24 Frames I started with famous paintings but then switched to photos I had taken through the years. I included about four and a half minutes of what I imagined might have taken place before or after each image that I had captured.

This declaration, apparently opposed to Cartier-Bresson’s doctrine of the “decisive moment,” leaves creative wiggle room. Kiarostami and his colleagues used digital manipulation to alter his stills, adding layers of figures and movements.

But how do we determine the punctual instant of each of the twenty-four shots? What’s the before or after? Many shots contain several moments of pause that might be the original frozen moment, but Kiarostami doesn’t give them special emphasis. After the Bruegel, we get twenty-three gradually changing natural scenes, nearly all mini-narratives based on stasis, rhythmic cycles, hesitations, and bursts of action. Five showed Kiarostami venturing into the territory of Structural Film, and especially the open-air tendency mastered by James Benning. With 24 Frames we get that monumental impulse recast by photorealistic animation: landscapes teased into little stories by the miracle of rendering, mo-cap, and drag-and-drop.

The birds and the beasts were there

The Bruegel is defaced for a reason. The original painting lays out strategies that the following sequences will pursue. Human bodies will play a subsidiary role; they appear in only two sequences, and, like Bruegel’s hunters, they are mostly turned away from us. We’ll also see snow, birds, dogs, trees, a scraggly bush, and water (the frozen pond). Just as important, Bruegel’s composition warns us how to watch. He draws our eye into the distance, and there lots of tiny figures will grace the scenes ahead.

Kiarostami’s decorations insert more previews. He introduces a herd of cows, blatantly fake falling snow, smoke that prepares us for mist and cloud formations. Dogs and birds are set into motion and given sounds; we’ll spend a lot of time tracking these vagrant creatures, and their cries will help us navigate the frames. The revised painting becomes a matrix of pictorial and auditory motifs that will be combined and varied throughout the movie.

Eventually the landscapes will include a wider menagerie, including lions and horses. At one point a duck seems to size up a possible mate, who approaches from the distance.

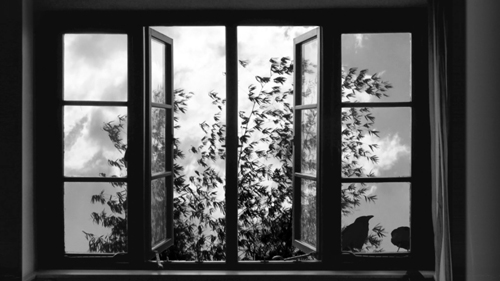

As here, most shots are centered, with the primary action taking place in the central third and sometimes accentuated by an aperture. The apertures often get geometrical. After several open landscape shots, the sixth sequence introduces a major compositional formula–the grid, typically a window, that will striate and cross-hatch our view. It yields a sort of Advent-calendar effect, as we follow birds or beasts hopping from one cell to another.

More variation: Most of the shots are planimetric. The camera is fixed at right angles to a background plane, and figures move horizontally. As the film goes along, though, an oblique angle may show up, as with the duck courtship. Kiarostami applied planimetric framing brilliantly in Through the Olive Trees (1994), but there too it interacted dynamically with less rigid compositions.

Maybe this is Kiarostami’s real Lumière homage. As in the earliest staged films, the single shot is given a simple arc. Figures arrive in the frame, do something, then depart. But sound is tremendously important too. Quiet activity is interrupted by brusque action–too often, a gunshot. More than you might expect, violence provides a spike of action before calm returns.

What holds these crisp, gorgeous shots together? Pairings, for one thing. The creatures we see often become couples. Lions mate, birds scrap with each other, ducks flirt, deer double up, and one gull mourns a fallen companion. Yes, I’m indulging in anthropomorphism. This movie firmly encourages you to try mind-reading Nature’s kingdom.

There’s a trace of surrealism. Some dreamlike images, impossibly hard-edged, are reminiscent of Rousseau. Sheep in a snowstorm huddle while a dog stares out at us and a wolf prowls in the distance. You might think of Paul Delvaux when you see a balustrade that has been built athwart rolling surf, as gulls squat placidly on the poles beyond.

Not least, I think, Kiarostami is responding to one problem of digital cinema–the way that a fixed digital shot makes certain portions of the frame go dead. Photographic film keeps the whole frame nervous, thanks to its teeming granular structure, but image compression simply reiterates “unchanging” information until something moves. When an area doesn’t harbor motion, it looks like a slice of stillness.

Kiarostami exploits this feature of the medium. Again and again, his image seems preternaturally frozen, a nature morte, before it twitches back to life. The effect, to recall his before-and-after idea, is of a still image reanimated. An inert animal seems dead to the world before we detect a breath or a shift of position. The most striking example seems to me the soft silhouette of a bird, a mere lump for seconds on end.

Rudolf Arnheim would have loved the fluid play of Gestalts that this simple composition arouses.

To show you more would spoil the pleasures of this delightful, melancholic, rapturous film. Let’s just say that it ends with a human figure slumped over and turned from us while the wind shakes trees outside a window. Warmth and drowsiness inside, a mild tempest outdoors. But in that same shot, a radiant human face, brought to slow-motion life, turns to us before it surrenders to a kiss. The fact that the face belongs to Teresa Wright, in one of the greatest films of the 1940s, ends Kiarostami’s career on a note of gentle jubilation.

Thanks to Brian Belovarac of Janus Films for help with this entry. Thanks as well to Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser of the Wisconsin Cinematheque.

24 Frames is being circulated to theatres and museums; please try to see it on the big screen, where all the little details can pop out at you. Eventually, it will show up on disc and FilmStruck‘s Criterion Channel.

For background on the making of the film, see the Janus press page. Imogen Sara Smith offers a sensitive appreciation in “In Our Time: Abbas Kiarostami’s 24 Frames” on the Film Comment site. For more on Kiarostami, including Certified Copy (2010), see our blog’s tag. I discuss his planimetric approach in Through the Olive Trees in On the History of Film Style, soon to appear on this site in an updated pdf.

24 Frames.

The ten best films of … 1927

Underworld.

Kristin here:

Once again it’s time for our ten-best list with a difference. I choose ten films from ninety years ago as the best of their year. Some are well-known classics, while others are gems I have found while doing research for various projects–though I have to admit that most of the films on this year’s list are pretty familiar.

One purpose of this yearly exercise is to call attention to great films of the past, for those who are interested in exploring classic cinema but aren’t sure where to start. (Previous lists are 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, 1922, 1923, 1924, 1925, and 1926.)

Hollywood dominates this year, with half the list being American-made.

There are reasons for the lack of international titles. This year was was the tenth anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but although Vsevolod Pudovkin’s celebratory film The End of St. Petersburg is here, Sergei Eisenstein did not finish October in time and it came out in 1928. (I remember the third anniversary film, Boris Barnet’s Moscow in October, as good but not necessarily top-ten material.) Some major directors didn’t release a film or made a lesser work. Dreyer was at work on The Passion of Joan of Arc, but it, too, wasn’t released until 1928. Lubitsch made The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg, a good but not great entry in his oeuvre. Japan’s output is largely lost. Yasujiro Ozu made his first film in 1927, but his earliest surviving one comes from 1929. Most of Kenji Mizoguchi’s 1920s films are gone, including those from 1927.

1927 was the year when Hollywood dipped its toe in sound filmmaking, but we need not worry about the talkies for now. Instead, all ten titles are examples of the state of sophistication that the silent cinema had achieved by the eve of its slow demise. (Sunrise‘s recorded musical track does not a talkie make.)

Hollywood, comic

The General is often listed as a 1926 film. This is technically true, in a sense, but I choose not to count its world premiere in Tokyo on December 31, 1926. Its American premiere was scheduled for January 22, 1927 but was delayed until February 5 by the popularity of Flesh and the Devil, which was held over in the theater where Keaton’s film was eventually to launch.

David recently posted an entry on how the great silent comics moved from shorts in the 1910s to features in the 1920s. His example was Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy, one of our ten best for 1924. Keaton moved into features slightly later than Lloyd, excepting The Saphead (1920), an adaptation of a play, in which Keaton was cast in the lead but over which he had no creative control. Once he did tackle features, he soon became adept at tightly woven plots with motifs and sustained gags. The General, based on a real series of events during the Civil War, has a solid dramatic structure that is more than just an excuse for a bunch of humorous bits. (A dramatic film, The Great Locomotive Chase, was produced by Disney in 1956 and based on the same events.)

The French title of The General is Le Mécano de la General. One might call Keaton that, since The General‘s comedy is essentially a long set of variations on the humor to be gotten out of the physical characteristics of a Civil-War-era train and its interactions with tracks and ties. Keaton had always been fascinated by modes of transportation and other mechanical sources of gags: an earlier train in Our Hospitality, boats in The Boat and The Navigator, a DIY house (One Week), film projection in Sherlock Jr., and so on.

At the beginning, Keaton’s character, Johnny Gray, tries to enlist in the Confederate army, but he is rejected without explanation. The officers consider him more valuable as a train engineer. Later, when Johnny is taking troops up to the front, a group of disguised Union soldiers steal his beloved engine, “The General.” Pursuing the thieves, he ends up deep in Union-occupied territory and takes his engine home, just in time to participate in a battle and prove his worth as a soldier.

The perfection of Keaton’s construction of gags is evident in one famous scene where Johnny’s engine is towing a cannon pointed up at an angle that would clear the cab if it were fired. Johnny has just loaded it with a cannon-ball and lit the fuse; he is returning to the engine when he foot becomes caught in the hitch attaching the cannon to the fuel car. The hitch drops, jolting against the ties so that the cannon slowly sinks to point straight ahead. A cut to a side view shows Johnny noticing this and panicking.

A view from behind the cannon emphasizes his danger as he starts to climb into the fuel car but gets his foot caught in the chain, a situation made clear by a cut-in. Once he is atop the wood-pile, he throws a log which fails to shift the cannon’s aim.

A cutaway establishes the Union soldiers who have stolen the General, approaching a lake in the background. Back at the pursuing engine, Johnny gets onto the cowcatcher, as far from the cannon as he can get. A return to the previous framing shows Johnny’s engine starting to turn on a curving stretch of track with the lake in the distance. The cannon follows.

As Johnny’s engine moves just out of the cannon’s trajectory, it fires. This would be enough for the pay-off of this elaborate gag, but the smoke quickly blows aside (possibly a wind machine offscreen left?) and we see the explosion in the distance near the General. As so often happens with Keaton’s gags, we are likely to gasp in amazement at the moment’s sheer physical complexity and ingenuity, as well as Keaton’s dexterity, before we start laughing.

The consensus among most critics and historians is that The General is Keaton’s finest film. In my opinion it goes beyond the top ten for a year to the top ten, period. Participating in the 2012 Sight & Sound poll of scholars and filmmakers, I put it in my list of ten films. It only made it to number 34 among voters, but then, my opinions didn’t coincide too well with the “winners.” Only two of the top ten were on my list. Such exercises are hardly definitive, given how difficult it is to choose among films at the highest levels of brilliance. That’s why David and I tend to stay away from them–except for films made ninety years ago.

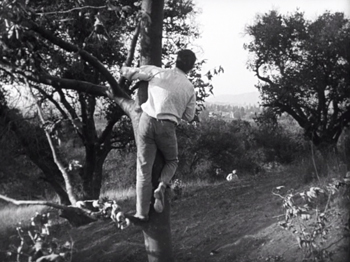

Harold Lloyd’s The Kid Brother is similarly one of his finest, along with Girl Shy (featured on my 1924 list and discussed by David in a FilmStruck introduction and his entry linked above). As David points out, Lloyd’s features usually give his character a flaw to overcome. Here, as a country boy overshadowed by his tough father and two older brothers, he believes himself to be timid and not worth much. He eventually proves himself, of course, partly from a desire to save his father, who is wrongly accused of stealing some money, and partly through the encouragement of Mary, owner of a medicine show passing through town, with whom he falls in love.

Harold Hickory is quickly set up as fantasizing that he is as capable as his father, the local sheriff, when he holds his father’s badge against his chest (see the top of this section). Not just a prop for character exposition, however, the badge leads him to be mistaken for the real sheriff. In trying to pass himself off as a convincing sheriff, he sets in motion a series of events that lead to the accusation of theft against his father and his attempts to recover the money from the real thieves.

As with Keaton, one of Lloyd’s strengths was an ability to plan a gag to use the whole frame, whether in depth or from side to side. The film stages several scenes in depth, as when the dishonest medicine-show men who will eventually steal the money arrive to try to get a permit to perform in town. As they arrive, Harold is seen in depth, wearing his father’s hat and badge, thus setting up the idea that they will believe that he is actually the sheriff. A more extended example occurs later, when he meets and is attracted to Mary, he climbs a tree to call after her as she leaves him, disappearing again and again behind a hill in the distance, and reappearing each time he climbs higher.

Lloyd skillfully employed shallow space equally well. When the medicine-wagon is destroyed by fire, Harold invites Mary to spend the night at his house. A disapproving neighbor lady soon takes her away, and Harold sleeps on the couch he had made up for Mary, complete with a tablecloth hung to give her privacy. Believing Mary still to be in bed, the two brothers separately sneak in to court her by primly handing her breakfast and gifts around the edge of the cloth. A shot from the other side shows Harold pretending to be Mary and enjoying being served food by the brothers when it is usually he who does the cooking.

Like The General, The Kid Brother demonstrates the sophistication that the great silent comedians had achieved by the late silent period.

As with the Lloyd films included in previous lists, The Kid Brother was released in the 2005 New Line boxed set, “The Harold Lloyd Comedy Collection,” now out of print and available only from third-party sellers. Sold separately, Volume 2 is still in print; it contains The Kid Brother and The Freshman, as well as other important Lloyd films. Volume 3 is still available new from third-party sellers. Volume 1 is available from third-party sellers, mainly in used (and higher-priced copies).

Hollywood, serious

The popular impression seems to be that the gangster genre originated in the early sound period. Wikipedia’s entry on the subject treats Public Enemy (1931), Little Caesar (1931), and Scarface (1932) as the first gangster films. There had been occasional silent films that could fit into that category, notably The Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912, D. W. Griffith) and Alias Jimmy Valentine (1915, Maurice Tourneur). In 1927, however, Josef von Sternberg made Underworld, which basically defined the genre that would soon become more prominent.

It has the gangster’s little mannerism, with “Bull” Weed bending coins to show off his strength (possibly the source of the cliché of the gangster flipping a coin). There’s the emblematic and ironic death, as when Bull’s nemesis “Buck” Mulligan is shot and falls at the foot of a cross-shaped memorial arrangement of flowers in the shop he uses as a front. There’s the thug with a heart of gold redeemed by the loyalty of a friend.

Von Sternberg is most often associated with Marlene Dietrich, whom he directed in seven films in the 1930s. He built three of his last four films of the late 1920s, however, around the burly star George Bancroft (below left). (We will encounter the second in next year’s list.) He’s also associated with beautiful design and cinematography, and the look of Underworld often anticipates the films noir of the 1930s (above, top, and below right).

I’ve already written about Underworld in greater detail than I have room for here–with additional pretty pictures. That was on the occasion of Criterion’s release of a set containing von Sternberg’s last three silents. Still indispensable but out of print and selling for high prices when you can find it. (Time for a Blu-ray?)

Late in her life, I asked my mother (born in 1922) what the earliest film she could remember seeing was. She replied that she couldn’t give me the title but recalled an image: a woman floating on a lake supported by reeds. I was quite astonished, partly because of all possible late 1920s films she had mentioned one which I could identify instantly from that brief description and partly because her memory had retained an impression of one of the great classics of the silent cinema. Living on a farm in Ohio, my mother probably saw it in a late run and so probably was six or seven at the time.

The presence of Sunrise on this list will hardly come as a surprise to anyone. Murnau has been a regular, appearing in our 1922, 1924, 1925, and 1926 entries. His first Hollywood film was thoroughly Murnauesque in style. It’s story of village versus country with a lingering touch of Expressionism in the rural scenes (below left) and modern design on ample display in the city (below right). The action could be set equally plausibly in Germany or the USA, except for the English-language signs in the city.

The plot is simplicity itself, with none of the characters even given a name. A Man is seduced by a Woman from the City, who convinces him to drown his Wife “accidentally” and flee with her to the gaiety of urban life. He nearly pushes his Wife into the lake while rowing across to the mainland but relents and tries to gain her forgiveness. This all occupies less than half the film, and most of the rest consists of the couple going forlornly to the city, with the Wife heartsick and the Man pathetically trying to reassure her. Once they reconcile, there is a long stretch of them having a good time in the city before heading home.

Yes, a good time. One might expect the city to be a hotbed of decadence that contrasts with their virtuous country life, but apart from an aggressively flirtatious gentleman, most of the people they meet are kind to them. A friendly photographer thinks they are a newly married couple and takes their portrait, sophisticated patrons at the dance-hall appreciate their performance of a country dance (below), and so on.

This meandering little set of unconnected vignettes does not conform to the Hollywood ideal. It presumably aims to guarantee that we believe in the husband’s redemption and the couple’s future happiness after their symbolic “re-marriage.” It holds our attention partly because of the charm of the two lead actors, George O’Brien and Janet Gaynor, and partly because the visual style always gives us something to look at. Murnau uses his “unfastened” German-style camera movements, not only in the famous track to the marsh early on but in a movement over diners’ heads accomplished by placing a camera on a support suspended from a track on the ceiling. (This technique was being widely adopted in Hollywood during the second half of the 1920s.)

Plus there’s that memorable scene of the Wife drifting on the lake, supported by reeds.

Sunrise is available in the elaborate 2008 12-disc boxed-set “Murnau, Borzage and Fox,” though the print is the usual soft, rather dark one available elsewhere. (The main gems of the box are the rare Borzage silents, including Lazybones, one of my 1925 picks.) Eureka! put out an edition of Sunrise as the first entry in its “Masters of Cinema” series. It contains not only the same print but a second print, a Czech release with distinctly better visual quality. (The image of the restaurant directly above was taken from it, while the others are from the “Fox Box.” I have not made a comparison between the two, but apparently the Czech version has significant differences from the American one.) This edition is out of print. Eureka! now offers the same two prints and supplements as a DVD/Blu-ray combination. Note that (despite what the Amazon.uk page says), this is a region 2 DVD and region B Blu-ray; both would require a multi-standard player in the USA and other regions.

The same “Fox Box” set contains Frank Borzage’s 7th Heaven, one of his best-loved films. By rights it should not be a great film. It is intensely sentimental, depends on huge coincidences, and has a thoroughly implausible ending, not to mention a saccharine religious theme that runs through it. Yet somehow it manages to be the greatest hypersentimental, coincidence-ridden, implausible, pious film ever. I cannot explain how or why.

Borzage’s film looks a lot like Sunrise, and it is often assumed that the resemblance arises from a straightforward influence of Murnau upon Borzage (e.g., his Wikipedia entry states that Borzage was “Absorbing visual influences from the German director F. W. Murnau, who was also resident at Fox at this time”), even though 7th Heaven was released four months earlier. There is something more complex at work here. The two films’ resemblances are not surprising, since German films had been drawing excited attention among American filmmakers for the past two years or so. The Last Laugh wasn’t a popular success, but its US distributor, Universal, showed it privately for cinematographers and others in the industry interested in studying it. Variety had been a hit. Its techniques of false perspective in sets and cameras moving freely through space soon caught on. For example, the sordid flat that the heroine Diane shares with her sister in 7th Heaven has a rough wooden floor sloping up toward the back (left). A similarly sloping floor appears in the bedroom in Sunrise (right)

German producer Erich Pommer’s first American film, Hotel Imperial (released by Paramount at the beginning of 1927), used a camera elevator, hanging sometimes from a track in the ceiling and sometimes from an improvised support on a dolly (see here for an image of it attached to the latter). The famous vertical elevator shot in 7th Heaven, following Chico and Diane as they ascend to his garret apartment at the top of the building was probably the most flamboyant use of the unfastened camera to that point. Below, in a later shot, the camera follows Chico back down as he goes to fetch water.

German style alone does not explain the film’s status as a great classic, though the slightly exotic look perhaps helped to make the garret romantic enough to be called “heaven” by its inhabitants as they fall in love. As with Sunrise, the Germanic look lends a certain fairy-tale quality that helps smooth over the plausibility issues.

Beyond this, there is again the charisma of the main actors. Janet Gaynor (who was in two of this year’s greatest films) and Charles Farrell (a slightly awkward but appealing actor) became the ideal couple of the late 1920s, co-starring eleven more times between 1927 and 1934. Equally, there is the ineffable directorial sincerity that comes across in Borzage’s best films, a trait often summarized as “romantic” or “naive.”

Unfortunately the print of 7th Heaven in the “Fox Box” is virtually unwatchable. Apparently the French DVD is from a better source than the Fox release; this DVD may be the source of a version which has been posted on YouTube with bright yellow Greek subtitles. The two frames above were extracted from that online copy. Another film calling out for restoration.

Germany: farewell to Expressionism

Expressionism probably would have ended in Germany in 1926, with the releases of Murnau’s Faust and Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Both films went over budget and schedule, with Lang’s being late enough to be released on January 10, 1927. Both films contributed to the decline of the large production company, UFA, which had to rely on loans from Hollywood to keep going. Murnau was by this point in America, and he never worked again in Germany. Lang had to produce his next film, Spione (destined for our 1928 list), himself, and he opted for a more streamlined modern look.

Metropolis mixes Expressionism with the sets representing the futuristic science-fiction city. The pleasure garden of the wealthiest class (above), as well as the catacombs and chapel of Maria far under the city are Expressionist, and even in the city sets the crowds often move in the choreographed fashion typical of the style.

Expressionism remained thereafter as a minor stylistic option. (Alexandre Volkoff’s 1928 French-German co-production Geheimnisse des Orients used Expressionist sets to create a fairy-tale Middle-East, rather like The Thief of Bagdad [1924].)

Metropolis has received so much attention that there is no need to plug it again as a great classic. In fact, it has been hyped to the point of being over-valued. Any of Lang’s other films from 1922 to 1928 is arguably better. It has a mawkish main premise (the heart must mediate between head and hands in labor disputes) and plot flaws (why would Fredersen destroy the substructure of his city when his power and dominance depend on maintaining it?), neither of which is a problem in Lang’s other films of this period. It deserves to be called a masterpiece for its audacity of vision, technical innovation, and many great moments.

Fans of the film will be aware that the long-lost scenes of the film were discovered in South America and restored to the film, rendering it nearly complete (running 148 minutes in Kino Lorber’s Blu-ray release). The recovered footage was unfortunately in very worn condition, and restoration can only do so much. The film is, however, much improved by having it.

David has already written on the strengths and weakness of this “great sacred monster of the cinema,” including a discussion of how the restored footage enhances it.

Back in 1970, when I was an undergraduate and first dipping a toe into film studies, G. W. Pabst was considered one of the major figures of German cinema, close to if not quite as great as Lang or Murnau. In my first film course the incomplete version of The Joyless Street was shown. (I liked it much better when it was restored.) I saw The Love of Jeanne Ney shortly thereafter. By now, however, The Joyless Street and Pandora’s Box have become the Pabst classics upon which his reputation is largely based. Whether Jeanne Ney‘s gradual fall into relative obscurity is the cause or the effect of its being difficult to see is hard to say. (I could only find it as a 2001 DVD by Kino, so-so but acceptable in quality.) Either way it’s a pity, since it deserves to be better known.

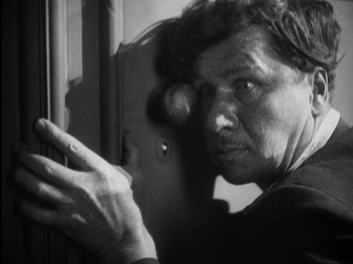

An adaptation of Ilya Ehrenburg’s novel of the same name, Jeanne Ney is set in the Civil War period that followed the Russian Revolution of 1917. The story begins in the Crimea, where Jeanne’s anti-Bolshevik father is a political observer. During the capture of the town by the Red forces, Jeanne’s lover, Labov, kills her father in self-defense. She forgives him and flees to Paris. Jeanne gets a job as a secretary in her miserly uncle’s detective agency, primarily to be a companion to her blind cousin. (Gabriele is played by Brigitte Helm, who was also Maria in Metropolis, thus making her our second actress appearing in two of this year’s top ten films.) A rascally opportunist, Khalibiev (played with sleazy relish by Fritz Rasp, see bottom) tries to marry Gabriele for her money, even though he actually lusts after Jeanne. Killing and robbing the uncle, he pins the murder on Labov.

Stylistically the film is a fascinating mix typical of the late 1920s, when influences were passing rapidly among European countries. It strives for a certain degree of the realism characteristic of the Neue Sachlichkeit movement that Pabst had helped to establish with The Joyless Street. The first part is influenced by the Soviet films that had become popular in Germany only the year before, and the Crimea-set portion could pass for a Soviet film, though not one of the more daring ones. The execution scene (below left), with the rifles sticking into the frame dramatically, was already calling upon a composition typical of the Montage movement. The interrogation of Jeanne takes place in a cluttered headquarters just set up by the conquering Reds (complete with authentic costumes and “typage” casting); the framing emphasizes both Bolshevik ideals and realism, placing in the foreground a soldier trying to make tea.

For the longer Parisian portion of the film, Pabst shot on location, as the French Impressionists were doing. He mixed this sense of realism (below left) with subjective scenes, including Jeanne’s superimposed vision of her wrongly-accused lover being executed. The film has one great set-piece, the cousin’s gradual discovery of her father’s murder as Khalibiev stands watching, thoroughly spooked by her blind staring face (below right).

Time to bring this film back into the canon.

Much more familiar is Berlin, die Sinfonie der Grossstadt, with which Walter Ruttmann brought the city symphony into the mainstream and solidified a growing strain of realism in German cinema. There had been short films and features that wove together visual motifs from urban life (e.g., Charles Sheeler and Paul Strand’s Manhatta, 1921), mostly captured on the fly though occasionally staged.

Ruttmann has been mentioned on previous ten-best lists for his abstract animation. Berlin begins with some moving abstract shapes that gradually give way to a train journey. During this real objects create abstract patterns, as when the girders of a bridge create a flicker effect as they flash by (below left).

The journey ends in a major station in the city. From there on, Ruttmann cuts together scenes to create what was to become a familiar city-symphony time-frame, a day in the life of a metropolis. Empty, silent streets lead to an early-morning dog-walker (above right) and then the bustle of the workday, lunch, and finally nightlife.

To this point most experimental films had been short and either abstract or surrealist. That experimentation could emerge from the documentary mode was a new concept, and Berlin, though it may not seem very radical to us today, helped to establish this new approach. The fact that it was co-produced by Fox Europa gave it distribution in mainstream theaters, and it has had a great influence on subsequent filmmaking, right up to the present. Coincidentally, that influence is demonstrated by the recent release of Alex Barratt’s London Symphony: A Poetic Journey through the Life of a City (2017). Flicker Alley’s liner notes include:

The release of this Blu-ray coincides with the 90th anniversary of Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, Symphony of a Great City (1927), one of the most important examples of the original city symphonies. Ruttmann was one of the great pioneers of experimental film, and Barrett and [James] McWilliam [composer] have worked hard to bring a similar sense of poetic playfulness to London Symphony, while also updating the form for the 21st Century.

Berlin is available in several DVD editions, but the definitive one is in a two-disc set including Ruttmann’s Die Melodie der Welt, the first German sound film, both in restored versions from the Filmmuseum series, as well as Ruttmann’s short abstract films. I note that this is available on Amazon in the USA, but be aware that it’s PAL and so requires a multi-standard player.

The essence of French Impressionism in 38 minutes

I know most readers will expect a much, much longer French film about Napoléon to be in this spot, but I’m opting for Jean Epstein’s modest but brilliant short feature, La Glace à trois faces (“The three-sided mirror”). Perhaps no other film of the Impressionist movement managed to create a plot that combines the subjective techniques that delve into character psychology with the presentation of events through fleeting impressions rather than linear causality. Most Impressionist films today seem a bit old-fashioned, adhering to the modernism of the era. La Glace seems familiar to aficionados of Resnais or Antonioni.

Epstein divides his brief tale of his protagonist, an unnamed playboy, into three parts devoted to the women–a wealthy society woman, a modern sculptor, and a modest working-class woman–who are all having affairs with him at the same time. Each tells her tale of his callousness and neglect to a sympathetic listener, and each presents a very different view of him. Intercut with their stories are scenes of the protagonist taking a solo ride in his sports car (above), speeding through the countryside and stopping at a local fair. Throughout he seems happier than he had with any of his lovers.

The individual scenes are brief, with quick cutting presenting glances and gestures, often from angles that prevent our getting a good look at what is happening, as with this moment in a restaurant.

We grasp what is going on primarily because the events are extremely simple. In each case the protagonist is with one of the women and abruptly walks out on her. The third tale, told by the working-class Lucie, is cut together in nearly random chronological order and with parts of the action missing. Lucie has prepared a romantic dinner at her home, but the man arrives, greets her, looks over the table, and leaves. In this snippet, however, his looking over the table is followed immediately by a shot of him just after his arrival, as Lucie embraces him and removes his hat.

The narrative achieves closure, but the film ends with an emblematic shot of the hero superimposed over a three-sided mirror, emphasizing the differences in the three women’s perceptions of him. La Glace à trois faces goes perhaps as far as any silent film does in using challenging modernist tactics, frustrating the viewer with a lack of clarity about causes and traits. It was a new form of narration that had little immediate impact on the cinema. The film was barely seen at the time. It would not be until decades later that similar techniques became common.

La Glace is available in the boxed-set of several of Epstein’s films, which I described and linked here. It is also included in Kino’s “Avant Garde” set on the 1920s and 1930s.

Tracing the birth of a Bolshevik

One can see why the Soviet government liked Pudovkin best among the major Montage directors. His films, while employing the fast cutting, dynamic angles, and other stylistic traits of the movement, are fairly straightforward and comprehensible compared to, say, Eisenstein’s pyrotechnics in October.

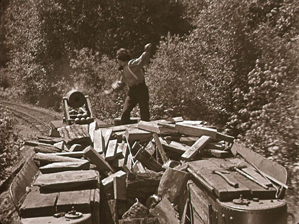

While the latter concentrates on the events of the Revolution proper, with no single character singled out for us to identify with, Pudovkin works up to the Revolution by following the radicalization of a peasant. The unnamed “Village Lad” sets out from his impoverished rural home to find work at a factory in the big city. We see the fomenting of a strike over dangerous working conditions and extended work hours, which begins as the Lad arrives. Ignorant of politics and the class struggle, he seizes his chance to join the scabs replacing the workers. Even worse, he betrays some of the strike’s leaders to police.

The story moves away from the Lad, who really is not very prominent in the narrative and is never characterized enough to gain much sympathy. As World War I begins, the film focuses on stock-market manipulation and war profiteering. Using typical typage casting, Pudovkin caricatures the capitalists as fat cats out for themselves (above). Eventually we see the Lad again, now wiser in the ways of the world and ready to serve the Bolshevik cause. By the end, the Reds attack the Winter Palace in a suspenseful scene, though one much shorter than the one in October.

Pudovkin featured on our list last year, for his best-known film, Mother. There the hero and his mother gain a good deal more sympathy than the Lad does, and The End of St. Petersburg is as a result perhaps a less entertaining film than Mother. Still, it is a masterly film and one of the gems of Soviet Montage.

While rewatching End on DVD, I realized that the main editions available used the same version of the film, a sonorized “restoration” done by Mosfilm in 1969. What other changes might have been made are not apparent (some films “restored” in that period were recut), but the images are severely cropped. The left side of the frame is missing, more than what one would expect would be necessary to add a sound track. The top and bottom, too, are missing portions. Only the right edge seems more or less intact.

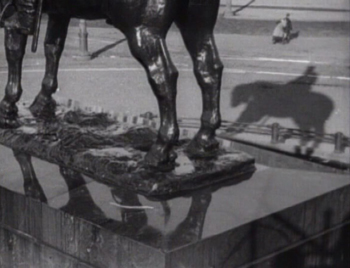

Take this famous image. The film has set up a motif of statues that come to stand for the imperial-era city. At one point there is a depth shot past an equestrian statue looming in the foreground while the Lad and his companion are seen as tiny figures walking across the square in the background. Compare the DVD image with one taken from an archival 35mm print.

This is bad enough, but when Pudovkin starts using the edges of the frame to make ideological points, the result nearly negates the his meaning. A famous shot shows a row of seated military officials with their heads offscreen. The 35mm image cuts them off precisely at the collar. The DVD print goes down to mid-chest, while losing much of the fourth man on the left. One might say that the same simple metaphor is being presented, but it’s not as instantly apparent what Pudovkin is implying here.

So while I recommend this film, I have to caution readers that it is not currently easy to see it in an acceptable print. An older 16mm copy or a 35mm screening in an archive would be ideal but not accessible to very many. If you want to see it, even in this faulty version, the Image and Kino releases both contain the Mosfilm print. The Image DVD has End paired with Pudovkin’s very worthwhile first sound film, Deserter (1933). Since it was a sound film to begin with, Deserter is not significantly cropped here and is quite good visually. Unfortunately this version is long out of print. The Kino DVD includes Dovzhenko’s Earth (1930) and Pudovkin’s short comedy Chess Fever (1925). It is available for sale and streaming on Amazon. Perhaps our friends at one of the home-video companies dedicated to putting out restorations on DVD and Blu-ray might consider tackling this key title.

For readers who prefer streaming, The Kid Brother, Sunrise, and Metropolis are currently available at FilmStruck on The Criterion Channel. Underworld, The General, The Love of Jeanne Ney, Berlin: Symphony of a Great City, La Glace à trois faces, and The End of St. Petersburg are held in MUBI‘s library, but none is currently playing there. We haven’t checked any of these versions.

Flicker Alley’s London Symphony is available for streaming here and on MOD Blu-ray.

Our colleague Vance Kepley has written a book in the Taurus Film Companion series on The End of St. Petersburg. It seems to be slipping out of availability on amazon.com, can still be had at amazon.co.uk, and is available directly from the publisher. Malcolm Turvey discusses some of the films on our list in his The Filming of Modern Life: European Avant-Garde Film of the 1920s.

December 28, 2017: Our thanks to Manfred Polak, who sends some good news about a restoration and possible upcoming availability of one of our films: “A restored version of “The Love of Jeanne Ney” was shown in an open-air event in Berlin last August. This version also aired on German-French TV station Arte, and it was available for legal download and streaming in HD for three months. I think there might be a DVD or Blu-ray of this version in a few months.”

The Love of Jeanne Ney

Ladies at all levels

La cigarette (1919)

Kristin here:

Earlier this month Flicker Alley released another of its ambitious collections of historic films, Early Women Filmmakers: An International Anthology. The dual-format edition contains three discs DVDs and three Blu-ray discs. Its ambitions are reflected in part by the volume of material included (652 minutes) and in part by the range of its contents, from well-known classics to obscure titles.

The collection was one of the last projects curated and produced by the late David Shephard. As with many of Flicker Alley’s releases, it was a joint project with Film Preservation Associates (Blackhawk Films) and Lobster Films of Paris, working with several film archives. The films are arranged chronologically, with the earliest being Les chiens savants (1902), a music-hall dog act attributed to Alice Guy Blaché, and the latest Maya Deren’s classic experimental film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943).

The publicity for the collection emphasizes that “More women worked in film during its first two decades than at any time since” (from the slipcase text). I would be interested in how such a claim was arrived at. It seems unlikely to me, if only because the film industries of the major producing countries have grown enormously since the silent and early sound periods. Still, despite this claim, the notes in the accompanying booklet (written by Kate Saccone, Manager of the Women Film Pioneers Project) describe how the DVD/Blu-ray release “reclaims that stature of ‘woman director’ and celebrates it in all its glory.” (One film included, Discontent [1916], is listed as “by Lois Weber”; in this case she wrote the screenplay, which was directed by Allen Siegler.) Thus the program does not survey the range of filmmaking work women performed–but such a survey would be essentially impossible. The lack of detailed credits on early films makes it difficult to determine even the director of a given film.

The silent films

It is not really possible to discuss all the films, but I’ll mention some and link to earlier entries where we’ve discussed some of them.

Of the 25 titles on the three discs, fourteen are silent. Six of these give an overview of work of Blaché, with three French films and three made after her move to the US.

Lois Weber is represented by three films, starting with perhaps her best-known work, Suspense (1913). With its unusual angles (see above), elaborate split-screen phone conversations, and action shown in the rear-view mirror of a speeding car, this is one of those films you show people to demonstrate how wonderfully inventive directors around the world became in that incredible year. I am also very fond of her feature, The Blot (1921).

The third Weber film, Discontent (1916), may surprise those familiar with her socially conscious features. In the mid-1910s Weber worked in a variety of genres. While David was doing research recently at the Library of Congress, he watched some incomplete or deteriorated Weber films that haven’t been seen widely. He wrote about False Colors here and here. Discontent is a comedy with a moral. An elderly man is living in a home for retirees, but he envies his well-to-do family. Finally they invite him to live with them, and naturally everyone ends up annoyed by the situation–including the protagonist, who winds up returning to the home and his friends.

Mabel Normand apparently directed quite a number of her films for Mack Sennett, and Mabel’s Strange Predicament (1914) is one of them. Its cast also includes Charles Chaplin and was his third film to be released, although it was the second shot and the first one in which he wore a version of his Little Tramp costume. Not surprisingly, he steals every scene he’s in. Normand even plays second fiddle to him, with her character forced for a stretch of the action to hide under a bed, where she is barely visible while Chaplin performs some funny business in the same room. (The print seems to have been assembled from two different copies, the bulk of the film being in mediocre condition with the ending abruptly switching to a much clearer image.)

One curious item in the program is Madeline Brandeis’ The Star Prince (1918). According to her page on the Women Film Pioneer’s Project, Brandeis was a wealthy woman who made films, mainly centering around children, as a hobby. Some of these were apparently intended for educational use. The Star Prince, her first film, is clearly aimed at children. A few of its adult characters are played by young adults, while children play both children and adults. This becomes a bit disconcerting when we assume for a long time that the prince and princess are perhaps seven or eight, until they fall in love and become engaged.

Despite the amateur filmmaking, there are some attempts at superimpositions and other special effects to convey the fantasy, as well as an charmingly clumsy pixillation of a squirrel puppet, the position of which is changed far too much between exposures.

This is the sort of local production, made outside the mainstream industry, that so seldom survives, and it is a welcome balance to the more sophisticated works that make up the bulk of this collection.

Speaking of which, the next part of the program consists of two features by one of the best-known female directors, Germain Dulac. The first, La cigarette, appeared in 1919. It’s melodrama about an fifty-ish Egyptologist, who has just acquired the mummy of a young princess who was unfaithful to her older husband. The professor begins to imagine that he is suffering a similar fate when his young and beautiful wife (see top) begins spending time with an athletic young fellow.

I remember seeing this film nearly forty years ago and thinking it was pretty weak. Luckily I have seen many films from this era since and know better how to watch them. Seeing it again I liked it quite a bit. It’s beautifully shot and well acted, and its sympathetic depiction of the doubting husband and the clever and resourceful wife is more subtle, in my opinion, than that of the marriage in The Smiling Madame Beudet (which is also included in this set). I was glad to have a chance to see the film again and recognize it as being among Dulac’s best work.

The silent section of the program ends with Olga Preobrazhenskaia’s The Peasant Women of Ryazan (1927). The title emphasizes that Preobrazhenskaia’s film is set in a provincial area. Ryazan, the capitol, is about 120 miles southeast of Moscow, so it is not one of the far-flung regions of the USSR. Still, it would have been distant enough at the time to have its own distinctive culture. Peasant Women gives us plenty of local costumes and customs without giving the sense of this being ethnography first and narrative second. Exotic though it may seem to us, this would have been recent history to Russians when it first came out.

Although most synopses claim that the story runs from 1916 to 1918, it actually begins shortly before World War I, probably in 1914, as the heroine Anna marries Ivan in a lively wedding scene including a carriage ride for the bridal couple (below). Shortly thereafter news of the war comes, and Ivan reluctantly departs for to serve in it. Anna is left in the household of her lecherous father-in-law, who rapes and impregnates her. The war goes on and ends, with the Revolution taking place entirely off-screen.

The second woman of the title is Wassilissa, a tougher sort, who applies to convert a decaying local mansion (we are left to assume that it was confiscated in the wake of the Revolution). She is seen at the end as being the prototype of the new Soviet woman, though Preobrazhenskaia throughout avoids hitting us over the head with overt propaganda.

The sound films

Perhaps not surprisingly, most of the directors on the third disc, devoted to sound films, are likely to be more familiar to modern viewers. Nevertheless, Marie-Louise Iribe and her film Le Roi des Aulnes (1920), were completely unknown to me. She was the niece of designer Paul Iribe and worked primarily an actress during the 1920s, and this seems to have been her only solo directorial effort. (IMDb lists her as the co-director of the 1928 version of Hara-Kiri, which she also starred in.)

Le Roi des Aulnes is one of the musically based movies that were popular in the early sound era, being based on both Goethe’s and Schubert’s versions of “Der Erlkönig.” It’s nicely photographed, and the part of the father is played by Otto Gebühr, known for being trapped by his resemblance to Friederick der Grosse into playing that role time after time from 1921 to 1941. He’s predictably excellent here, though the stretching of the short poem into a 45-minute film forces him to register worry and eventually grief throughout. Indeed, despite extrapolated incidents, such as the injury of the father’s horse and the need to procure a new one, a great deal of repetition occurs: lots of riding through marshes and menacing appearances by the Erlkönig, who is portrayed as a large man in chain-mail.

The special effects are the most impressive thing about the film, using double superimpositions in widely different scales, with the giant king holding a small fairy on his palm.

Despite its problems, the film is a valuable addition to our examples of this mildly avant-garde trend that flourished for a short time.

Most of the rest of the directors are well-known and can be mentioned more briefly.

The great animator and innovator of silhouette animation Lotte Reiniger is represented by three short films: Harlequin (1931), The Stolen Heart (1934), and Papageno (1935). I have written about Reiniger’s complex compositions, including her subtly shaded backgrounds. Of the directors represented here, she is the one who enjoyed the longest career, from 1916, when she would have been 17, to 1980, when she was 81. I discuss a BFI boxed set of some of her 1950s films here. I haven’t been able to find a complete filmography, but William Moritz estimates that she made “nearly 70 films.”

Alexandre Alexeieff and Claire Parker’s A Night on Bald Mountain is similarly familiar. Like Iribe’s Le Roi des Aulnes, it falls into the genre of illustrations of existing musical pieces, being an illustration of a piece of the same name by Modest Mussorgsky, as arranged by Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov. It was created by manipulating hundreds of pins on a large frame called a pinboard, invented by Alexeieff, his first wife Alexandra Grinevsky-Alexeieff (whom he divorced in order to marry Parker in 1940), and Parker. The textured effect is quite unlike that of any other type of animation.

Dorothy Davenport was a prolific actress from 1910 to 1934. She is perhaps most remembered as the widow of Wallace Reid, a star who died from the effects of morphine in 1923. She directed seven films over the next decade, ending with the film in this set, The Woman Condemned (1934), mostly either uncredited or signing herself Mrs. Wallace Reid.

The Woman Condemned is a B picture, produced independently and distributed through the states’ rights system. It’s a competently done murder mystery that gains some interest by withholding a great deal of information from the audience. There are two main female characters, the victim and the accused (seen below in an interrogation scene), and we have very little idea of their motives and goals until the climax of the film. The revelations involve a twist on the same level of groan-worthiness as “and then she woke up.” But again, having a little-known B picture adds to the wide variety of films presented here.

One can hardly study early women directors and skip over the favored documentarist of the Third Reich, Leni Riefenstahl. Day of Freedom (1935) is a good choice for inclusion, occupying only 17 minutes of screen time and amply demonstrating Riefenstahl’s undeniable gift for creating gorgeous images from ominous subjects.

Experimental animator Mary Ellen Bute is represented by two contrasting abstract shorts, the lovely black-and-white ballet of shapes, Parabola (1937) and the vibrant and humorous Spook Sport (1939), the latter (below) made with the collaboration of Norman McLaren.

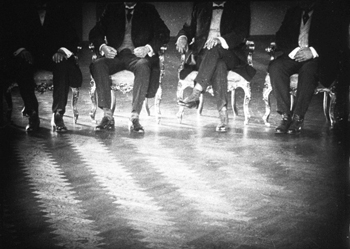

Dorothy Arzner, the only woman to direct mainstream Hollywood A films from the 1930s to the and 1940s, is introduced via a clip from one of her most famous films, Dance, Girl, Dance (1940). In the scene, Maureen O’Hara’s character interrupts her dance routine to tell off an audience of mostly men who are cat-calling her.

Maya Deren’s first film, Meshes of the Afternoon (1943) ends the program (see bottom). It is a happy choice, since of all the films in the program, it has undoubtedly had the greatest influence on the cinema. Much of the subsequent avant-garde cinema has turned away from music-inspired abstraction and opted for ambiguity, psychological mystery, and impossible time, space, and causality.

Valuable though this collection is, I cannot help but think that some of the directors represented have been oversold. Saccone sums them up:

Together, these 14 early women director have produced bodies of work that are inspiring, controversial, challenging, invigorating, and thought provoking. These women were technically and stylistically innovative, pushing narrative, aesthetic, and genre boundaries.

Surely not all of them meet these criteria. We would hardly expect one hundred per cent of the male directors of the same era to be “technically and stylistically innovative,” so why should we expect all of the work by fourteen varied female directors to be so? Saccone quotes Tami Williams’ book, Germaine Dulac: A Cinema of Sensations. on how the director searched “for new techniques that, in the light of official discourse of governmental and social conservatism, and the modernity of the new medium, were capable of expressing her progressive, antibourgeois, nonconformist, and feminist social vision.” Saccone sees this search in The Smiling Madame Beudet, where “Dulac utilizes cinema-specific techniques such as irises, slow motion, distortion, and superimposition, as well as associative editing, to give visibility to the inner experiences and fantasies of an unhappily married woman …”

Readers might infer that Dulac innovated these techniques. Yet they had already been established as conventions of French Impressionist cinema, notably in Abel Gance’s J’accuse (1919) and La roue (1922) and Marcel L’Herbier’s El Dorado (1921). For example, Dulac surely derived the distorted image of Beudet that conveys his wife’s disgust (below left) from a similar shot of a drunken man in El Dorado (right).

This is not to say Dulac isn’t a fine filmmaker or that she had no new ideas of her own. Only that she didn’t single-handed discover these techniques, but rather she turned the emerging repertoire of Impressionist techniques toward portraying a woman’s experience.

In some cases films that were co-directed by these women are presented as their sole efforts. Lois Weber’s Suspense was directed, as were many of her early shorts, with her husband, Phillips Smalley. Quotations from interviews with both Weber and Smalley make this clear. In 1914, Smalley said of his wife, “She is as much the director and even more the constructor of Rex pictures than I.” “Even more” because Weber often wrote the screenplays for their films and in at least some cases edited them. Weber later described how Smalley worked from her scripts: “Mr. Smalley got my idea. He painted the scenery, played the leading role and helped direct the cameraman.” Directing the cameraman is part of the job of a director.

The list of films in the booklet attributes Night on Bald Mountain entirely to Claire Parker, though on the backs of the disc cases the credit is to Claire Parker and Alexandre Alexeieff. Alexander Hackenschmied (aka Hammid) is not mentioned in the list of films, and the booklet refers to him as having a “close collaboration ” with Deren, even though he and Deren are both listed as directors on the original credits of Meshes of the Afternoon.

Still, if the collection does not make the case that all of the women represented were wildly talented and innovative, it does show the variety of ways in which women managed to work both in and out of the mainstream industry. It’s valuable collection of historical examples and should be welcomed by anyone interested in the silent and early sound eras.

It is worth noting in closing that viewers should not expect all of these films to be presented in the usual beautiful restorations we are used to from Flicker Alley. Some of these films are indeed gorgeous, including the two Mary Ellen Bute shorts, Peasant Women of Ryazan, Day of Freedom, Meshes of the Afternoon, and La cigarette (though the latter has some small stretches of severe nitrate decomposition). Other prints are quite good or at least acceptable. A few of the films simply do not survive in any but battered or faded prints, notably Discontent and The Star Prince. But we are lucky to have them at all.

The quotations from the Smalley and Weber interviews are from Shelley Stamp’s Lois Weber in Early Hollywood (University of California Press, 2015), pp. 26-27.

[May 23] Many thanks to Manfred Polak, who has drawn my attention to a higher estimate of Reiniger’s lifetime production of silhouette films. Her friend and executor, Alfred Happ, put the figure at about 80. The source is an exhibition catalog from the Stadtmuseum Tübingen, which houses Reiniger’s archived material: Lotte Reiniger, Carl Koch, Jean Renoir. Szenen einer Freundschaft. Die gemeinsamen Filme. ed. Heiner Gassen and Claudine Pachnicke (Stadtmuseum Tübingen, 1994).

Carl Koch was Reiniger’s husband and collaborator; Reiniger created an animated sequence for her supporter and friend Jean Renoir’s La Marseillaise. According to Manfred, “Alfred Happ and his wife Helga were Reiniger’s closest friends and caretakers in her last years in Dettenhausen (near Tübingen, Germany). After Reiniger’s death, Alfred Happ was the administrator of her estate. If you ever come to Tübingen, visit the Stadtmuseum (City Museum), where her estate is hosted now. A part of it is shown in a permanent exhibition.” He also provided a link to a touching account of Reiniger’s friendship with the Happs.

Meshes of the Afternoon (1943)