Archive for the 'Digital cinema' Category

Il Cinema Ritrovato: A final entry

The courtyard outside the Cineteca di Bologna, during Il Cinema Ritrovato.

DB here:

Some initial figures are in, and they’re fairly stupendous.

There were about 85,000 admissions to all screenings of this year’s Cinema Ritrovato, which ended ten days ago. That figure includes the big public shows on the Piazza Maggiore, but the day-in, day-out screenings were heavily attended as well. There were 2500 or so festival passes sold. Assuming that those people stayed for four of the festival’s eight days and attended four shows a day, we can surmise that at a minimum 40,000 of overall admissions came from dedicated cinephiles surging from venue to venue. And of course many passholders stayed seven or eight days and squeezed in more than four viewings on each one.

Broiling heat—one day approached 100 degrees Fahrenheit—didn’t seem to keep many away from the films, panels, book talks, and other events that crowded the schedule. Between 9 AM and 1 PM, each two-hour block offered six to eight choices, and the afternoon blocks, running from 2:30 to about 8 PM offered even more. Now that the festival has another space, a nearby university auditorium fitted for DCP projection, a whole new column of events was slotted in. Below, a bit of the queue for the Isabella Rossellini interview in the auditorium.

Next year, planners are hoping to add screenings at a renovated 100-year-old theatre on the Maggiore. There seems no doubt that the Cannes of Classic Cinema will get even bigger.

For the first time, I felt the pace was a bit rushed. Getting together with old friends was somewhat harder than before, unless you came a day or so early. (Even then, there were tempting Maggiore evening shows.) But the atmosphere was still easygoing. The courtyard of the Cineteca was an island of steamy relaxation, boasting more tables than in past years. The tent cafe provided snacks and drinks for those who simply decided not to be obsessive. Even I stopped and sat down, twice.

Word is out. A new wave of young film lovers has discovered Ritrovato. What had been dominated by hip (or hip-replaced) baby boomers was now teeming with students. The festival has added a Kids section and another devoted to older teens, and it was a pleasure to see them winding through the corridors of the Cineteca. The World Press has finally woken up too. The Guardian ran a rapturous encomium. Loyal blog sites such as Photogénie provided extensive coverage.

Just speaking for us, this was the first year Kristin and I had almost no time to blog during the event. Hence this, the last of our catch-up entries. (Click back for the earlier ones.) And I will leave out a lot.

All in favor of film, raise your hands

Has everything been said about digital cinema and its differences from photochemical cinema? Maybe so. Nonetheless, the two panels I visited on the subject raised a lot of intriguing points, in quite different formats.

The first session compared 35mm prints with digital restorations. Through clever maneuvering, the Ritrovato boffins were able to switch back and forth between versions as both were running, and the results were pretty compelling. Schawn Belston of Twentieth Century Fox provided a sample of Warlock, a twenty-year old print. It was contrasty but had saturated color; this was the sort of image I remember seeing in theatres. The digital restoration, a work in progress, was paler, with sharper edges, more solid-black shadows, and a more pastel color design. Pretty Poison was a much newer print, on Vision stock, and looked fine, as did the DCP.

Grover Crisp of Sony brought a Kubrick-approved print of Dr. Strangelove, considered best-quality in 1990s. He ran it in tandem with the recent 4K restoration managed by Cineric. The difference was very striking. For black-and-white, at least, the DCP seemed to me to have all the better of it. Kubrick, a major otaku on matters photographic, would I think have approved.

Further proof of the Crisp-Sony finesse was available in the utterly dazzling DCP we saw of Cover Girl (1944) on the big Arlecchino screen. I was surprised to find some of my circle disdaining this movie, but I think it’s wonderful. It seems to me a rough draft for many of Gene Kelly’s MGM pictures, from the trio boy-girl-stooge we get in Singin’ in the Rain (with Phil Silvers as Donald O’Connor) to the mind-bending doppelganger dance that looks forward to Anchors Aweigh and Jerry the Mouse. I also like the clever motifs of feet and faces, and the flashbacks, and …well, I must stop, because I expect to use Cover Girl as a major example in my still-unfinished book on Hollywood in the 1940s. Suffice it to say that I have never seen a better DCP rendering of Technicolor than was on display in Grover’s new edition.

Davide Pozzi rounded out the session with a pairwise comparison of different versions of Rocco and His Brothers. A vintage print from the camera negative had been vinegared, so the shots had rippling focus; the DCP restoration was fairly sharp and bright. This was a real work of reclamation.

The panelists agreed on a lot. Don’t try to banish grain; film is grainy. Don’t expect to match everything. No two prints ever looked alike anyhow, and variations among screens, lamps, and other exhibition factors don’t let us capture a pristine original experience. Because of the advances of digital restoration, there are new frustrations. Archivists are aware that older restorations may not look good today, while cinephiles who forgive scratches on “vintage” 35mm copies howl if a restoration doesn’t look smooth as silk.

Film has many futures. Pick one.

Serge Bromberg introducing the Lobster Films anniversary program, which included several “faux Lumières.”

Another panel, “The Future of Film” (let’s ban this as a title, shall we?), was less focused but more provocative. No fewer than fifteen critics, archivists, manufacturers, and filmmakers gathered before a standing-room crowd to discuss the prospects for the photochemical medium formerly known as film.

The panel’s speakers worked in shifts, three at a time. Everybody was lucid and brief. Some general points:

On the manufacturing front, Kodak and Orwo are committed to producing motion-picture stock. Christian Richter of Kodak noted that in 2006 his firm produced 11.8 billion feet of motion-picture film, while last year it produced only 450 million feet. The demand may be plateauing, but it’s too soon to be sure. The crucial problem may be the absence of labs, although boutique labs are starting to appear.

Some filmmakers, such as Gabe Klinger, consider film an essential part of their aesthetic. Alexander Payne prefers to shoot on film, but more important is film projection. He restated his view that “flicker will always be superior to glow.” By contrast, archivist Grover Crisp proposed that the standard of film projection had sunk so low that he prefers to see digital presentations, although those too can be substandard.

Some archives are preserving on film recent movies, including those shot digitally. Sony does, as does the CNC. Eric Le Roy reported that all French films receiving subsidy must deposit a print and the negative there, even if the project originated digitally. Mike Pogorzelski of the Academy archive spoke of the ongoing “Film to Film” effort, begun in 2012.

More generally, two archivists argued that the future of film lay in museums. José Manuel Costa of the Portuguese film archive argued that the basic principle had to be a respect for the nature of the medium. Cinema has changed, but it has existed in a specific technological environment since the nineteenth century, and it’s the mission of a film museum to retain that technology as long as possible. Accordingly, a film should be shown in the format in which it was made.

Belgian film archivist Nicola Mazzanti (on left above, with Pietro Marcello and Alexander Payne) seemed in accord. He remarked, in the wake of the earlier session, that digital treatment, or film restoration generally, can’t duplicate tinting, toning, stencil color, Technicolor, and other older processes. The originals are what they are—imperfect—but that imperfection is inherent in their material history. More acutely, the world outside the archive is entirely digital, so it will be a big task to keep analog alive. It will take money. And no European archive’s budget equals the cost of a single season of La Scala.

Scott Foundas, who chaired the sessions with easy good humor, indicated that perhaps the state of play was this. Digital capture and storage would not wholly replace film. By now film is recognized as distinct and worth its own attention. It’s going to exist alongside digital media for some time to come, although in niches and in more rarefied forms than before; like vinyl records.

Bologna, it became clear, is one of those places where film will continue to flourish. Fifty percent of screenings this year were analog, and the programmers included showings of Vertigo, The Heroes of Telemark, All That Heaven Allows, and other titles on “vintage” prints from earlier eras. Audiences packed in to see them and cheered.

What they saw, we must see

With all the talk of film’s enduring powers, two screenings reminded me of the power of photochemical recording as a record of history, both en masse and individual.

German Concentration Camps Factual Survey was overseen by Sidney Bernstein and involved several skilled filmmakers, including Hitchcock. It was designed to be shown to the German people as a record of what they had ignored over the last dozen years. But it remained unfinished when it was shelved in 1945.

In recent years the surviving reels have been shown occasionally under the title Memory of the Camps. In 2008 several staff at London’s Imperial War Museum began to restore the original and fill out the final reel. The filmmakers added a new recording of the original commentary, previously not attached to the footage.

Friends of Andy Warhol often commented that he used his ever-present Polaroid to keep his distance from his surroundings. You wonder if a similar strategy didn’t insulate, to some minimal degree, the American, British, and Russian cameramen who filmed the liberation of the camps. Their images show shriveled corpses covering the ground, flung into pits, shoveled into heaps. Spindly survivors move like ghostly marionettes. When I saw the first images of the bland camp officials smoking and chatting under guard, I immediately wondered: What self-control it must have taken not to have killed these men on sight.

The film is structured as a sort of anti-Grand Tour, starting in Bergen-Belsen, where SS officers seem genuinely annoyed at being forced to clear out the dead. The film moves eastward, guiding us by maps, to end in the abandoned Nazi extermination camps built in German-occupied Poland. Here shoe brushes, spectacles, and children’s toys fill warehouses. The names of German companies proudly adorn ovens.

One of the film’s main points, apparently suggested by Hitchcock, is the fact that the camps existed very close to population centers. Did the people celebrating Oktoberfest in Munich ever think of Dachau, half an hour away by train? Did the people breathing the mountain air of Ebensee spare a thought for the camp nearby? Arriving Allies insisted that people from surrounding towns be brought to witness what they had ignored. In the footage, men, women, and children file by the carnage.

Some seem moved, but eerie shots show town elders standing stiff and impassive before heaps of bodies.

Toby Haggith, one of the film’s restorers, was on hand for a follow-up session, something really demanded by the intensity of the experience. He answered questions with great seriousness and eloquence. He explained that the restoration team had decided to leave in the film’s original errors, based on contemporary reports of the size or uses of certain camps, as well as the film’s avoidance of focusing on Jewish victims. The film stresses the Nazis’ crimes against humanity at large, an emphasis, as Haggith pointed out, in tune with the United Nations initiative of the moment. “The very historicity of the film is what seizes us.”

Godard has suggested that there must be footage of the day-to-day running of the camps. Would the society that devised Agfa film and Arriflex cameras have failed to document the industrial-scale slaughter of which the Reich was so proud? Were there no amateur cineastes among the SS-men leading comfortable lives in their cottages? Was there no Leni Riefenstahl to cheerfully lend credibility to these charnel houses? Even if such footage exists, German Concentration Camps Factual Survey will serve as an unforgettable reminder that humans have a terrifying gift for brutality, and for ignoring horrors enacted right beside them.

Many doubts, much faith

Visita ou Memórias e Confissões.

In 1982, financial setbacks forced the Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira to sell the house he had lived in for forty years. Before leaving, he decided to record his affection for the place. The result, Visita ou Memórias e Confissões was the quietest film I saw at Ritrovato. It was also one of the best.

We start at the gateway, coming in as if guests. But who owns the voices we hear? The murmuring man and woman who seem to be our surrogates passing along the path? We never see them as they enter the magnificently curvilinear house. But is it right to say they? Although we hear two voices, we hear only one person’s footsteps. The somewhat whimsical uncertainty that haunts so many Oliveira films is summoned up here by the simplest of means.

Eventually Oliveira greets us, standing in his study before his typewriter, and he explains some of the house’s history. He also runs some footage on a 16mm projector that coaxes him into discussing death, women, virginity, and sanctity. “I’m a man of many doubts and much faith.” Occasionally we hear the couple whispering as we coast past art objects and family pictures.

Oliveira tells us of his 1963 arrest while making Rite of Spring and his 1974 conflict with workers in his family’s factory—a tumultuous event that, we learn rather late, is the cause of his financial distress. These revelations come in the midst of a fascinating account of his family, accompanied by a tribute to his wife, to whom the film is dedicated. Individual history and social history blend in his recollections and the flow of visual memorabilia.

The spectral visitors glide out with us, and the film that Oliveira has been showing halts, leaving us a blaring white frame. According to his wishes, Visita wasn’t shown until after his death. Perhaps in 1982 he expected that event to come rather soon; he was seventy-three, after all.

He couldn’t have known, surely, that he would live another thirty-three years and make twenty-four more films. As José Manuel Costa pointed out, the great director wanted the film to be shown posthumously not as a final boast, but rather a wry, modest memoir of an exceptionally full life. By turns ironic and confessional, Oliveira’s testament demonstrates that we can be moved by a soft-spoken, patient peeling back of layers of the past.

Of course it was shown on film.

Kristin and I thank the many staff members who make Ritrovato such a wonderful experience. Special thanks to Gian Luca Farinelli, Guy Borlée, and Cecilia Cenciarelli. We are particularly grateful to Marcella Natale for her many moments of assistance, including giving us preliminary attendance figures.

German Concentration Camps Factual Survey will play several film festivals and public venues during the rest of the year and will eventually be distributed on DVD. Night Will Fall (2014), André Singer’s documentary on the making and restoration of the original film, is already available.

P.S. 31 July: Danny Kasman has an illuminating interview with Toby Haggith on the Factual Survey, along with important background information, at Cineaste.

The waning thrills of CGI

Kristin here:

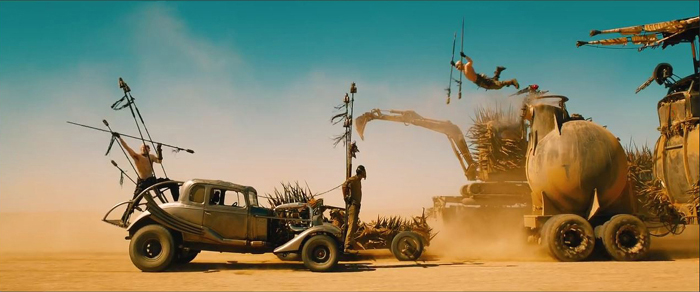

There have been rumblings lately about the surfeit of CGI-heavy films, especially superhero movies, and about a certain monotony in the results. Critics and fans are hailing Mad Max: Fury Road, in no little part because George Miller did stage much of the action, with real fantasy vehicles and hair-raising stunts, and employed CGI only when necessary. Among the diehard Peter Jackson fans over on TheOneRing.net, many argue that the emphasis on practical effects over digital in the Lord of the Rings trilogy should have been carried over to the Hobbit trilogy, despite the advances in CGI technology in the nine-year gap between them.

Earlier this month, Variety‘s Brian Lowry published an editorial laying out the problem. He concentrated on the superhero movies that have increasingly come to dominate the tentpole level of big-studio filmmaking:

The ability to mount enormous battles featuring multiple super-powered characters, however, has become its own trap. And while the results can be visually astounding, the movies regularly feel as lifeless and mechanized as the technology responsible for bringing those visions to fruition.

The why of it remains something of a mystery, but the outcome is frequently a hugely expensive–if often enough quite lucrative–tentpole release that certainly puts the money onscreen, yet nevertheless proves more numbing than exciting, even during what should be the show-stopping sequences.

The original “Avengers” was mostly a happy exception, even with its prolonged alien-invasion climax. “Age of Ultron,” while ambitious in exploring relationships among characters, becomes drearily repetitive as the heroes mow down another CGI horde, this time consisting of artificially intelligent robots.

[…]

The pattern has become predictable. “Iron Man,” a terrific movie overall — particularly in capturing the origin story — degenerated into a mundane brawl between two armor-clad characters. Ditto the “Hulk” reboot with Edward Norton, which culminated with the title character’s ho-hum showdown with another green behemoth, the Abomination.

One can argue, in fact, that the much-maligned second “Star Wars” trilogy sacrificed an element of its humanity in George Lucas’ embrace of a wholly digital filmmaking approach. At a certain point, watching droid armies being whacked to pieces begins to yield diminishing returns.

Put more simply, just because CGI wizardry allows you to do something, whether hoisting an entire city into the air or leveling skyscrapers willy-nilly, doesn’t always mean you should. Because while the box office figures might suggest otherwise, there is an audience out there that’s weary of these movies precisely because of the hollow quality to the inevitable final 30 minutes of unrelenting mayhem.

This struck a chord with me, because since the beginning of the year I have seen trailers for several CGI-heavy films. (How many of them begin with an ominous “helicopter shot” high over a CGI city, usually at night?) Most of them melt into each other in my memory, but I do recall that they included Insurgent (the teaser, below left) and Jupiter Ascending (trailer #3, below right).

My reactions to the Insurgent and Jupiter Ascending images were: 1) another burning cityscape with a CGI person flying through the air, and 2) wild horses couldn’t drag me to these.

Compare these two frames with the image at the top of this entry. My reactions to the Mad Max: Fury Road teaser, which I only saw in HD on my computer, were: 1) what a gorgeous shot, 2) why is that guy doing that–he’s crazy, 3) George Miller and all these other people are crazy, and 4) I must see this film ASAP. The same qualities attracted me to The Road Warrior, but this time Miller had a far bigger budget, allowing him to create more vehicles and make them more elaborate.

The increasingly same old-same old quality about superhero films extends to science-fiction films and dystopian future ones.

CGI is a marvelous technology and has been used to create wonderful films, scenes, and characters. Gollum remains one of its most successful and memorable creations. I suspect that many, like me, remember that initial jolt of amazement in the scene in The Two Towers when the mild “Smeagol” and villainous “Gollum” sides of his nature talked to each other, and a sudden switch to shot/reverse shot made his split visible, as if he had two bodies:

It was a brilliant way to handle the scene, but it also depended on us accepting Gollum as a character on the same plane of existence as Frodo and Sam. Yes, the technology for Gollum was improved for his reappearance in The Hobbit, but it wasn’t dramatically better, and the first trilogy was the real breakthrough.

Smaug was another creation where one could hardly deny that CGI was used with astonishing complexity and skill (see bottom). The same is true for The Dawn of the Planet of the Apes and The Rise of the Planet of the Apes (also with effects by Weta Digital, which also managed to fill in scenes involving the late Paul Walker in Furious 7 without barely anyone noticing).

Lest all this become too Weta-centric, I also have seen the teaser for Robert Zemickis’ The Walk a few times. Again there’s a computer-generated cityscape, as in Insurgent and Jupiter Ascending, but the effect is quite different. It’s an attempt to create realism in a story based on actual events; the actor obviously can’t be placed high above New York, and the Trade Towers are gone. The effect is anything but clichéd. That I was to see, too.

Another well-reviewed current science-fiction film, Ex Machina, uses CGI in an original way. David liked it less well than I did, but whatever one thinks of the film as a whole, the robot character Ava is not something we’ve seen on the screen before–at least, not done this way.

Historically, any art form goes through cycles. Hugely successful films will give rise to many imitators, and imitation eventually leads to cliché. The question is, will the filmmakers called upon to make big effects-heavy films make the effort to use CGI in an imaginative way? With sequel after sequel in the largest franchises already planned by the studios for years into the future, will the apparent assumption that flashy CGI is enough to attract the action-movie crowd prove wrong?

The madness of Mad Max

Despite the critics’ emphasis on the practical effects and real locations in Fury Road, it should be pointed out that Miller used quite a bit of CGI in the film. Indeed, he was no stranger to digital effects. For Babe (1995), his team used CGI to achieve the most realistic talking animals in films to that time. (Miller produced and wrote the script, with Chris Noonan directing; he directed Babe: Pig in the City.) Previously talking animals were usually done with puppets and animatronics, but Miller’s team used 3D scans of animals snouts and muzzles and manipulated the results. Babe won the 1996 Oscar for best visual effects. There were no exploding cities, giant armies, or battling superheroes, but experts recognized those moving animal mouths as cutting-edge stuff.

In Fury Road, CGI is used for effects that would be difficult, impossible, or prohibitively expensive otherwise. Furiosa’s missing left wrist and hand are an obvious example, as is the massive sandstorm that hits the fugitives and pursuers.

The blue night scene was shot day for night and then enhanced digitally, presumably with tinting and the addition of stars. The city which is the Citadel’s source of gasoline and is supposedly Furiosa’s goal as her truck sets out early in the film, is shown on the distant horizon but clearly was not built, since none of the action takes place there. The Citadel scenes were done in Australia, while most of the desert material was shot in Namibia. Some parts of the Citadel were built full-scale (e.g., the winch room), while green-screen replaced by digital set extensions supplied the rest. I think I spotted some digital matte paintings in some of the landscapes. But on the whole, Miller stuck to real locations, and most of the scenes of the chases were done with real vehicles and actors, chasing each other around the Namibian desert.

Miller commented, “We don’t defy the laws of physics–there are no flying human beings, no spacecraft–so it doesn’t make sense to do it as CGI. We’ve got real vehicles and real humans in a real desert, and you hope that all that texture will be up there on the screen.” Miller had in fact assumed that he would have to create the “pole cat” sequence, which has men perched on long, swaying poles atop speeding vehicles (above). Action unit director Guy Norris, however, shot a test scene on video, with no CGI. Miller was thrilled: “There were 10 pole cats swaying, coming down the road at speed, all of them on cars, and Guy was on one of the poles filming them. I choked up. I thought, ‘Wow, it’s real. It’s absolutely real.”

According to Simon Gray’s “Max Intensity” in the latest American Cinematographer (not yet online), “Months of rehearsals enabled the stunt crew to perform their choreographed sequences while the vehicles traveled at speeds up to 50 miles an hour.” (AC, June 2015, p. 42)

The reality of it comes through, as in this scene of one of many explosions. The stunt man flinching in the foreground is not the sort of thing you’d see if this were all being faked.

And some of the stunts are not all that different from what we saw in The Road Warrior or Beyond Thunderdome, both made in the pre-CGI days. This scene, for example, among the best in the film, where a motorcycle gang chases Furiosa’s rig.

One reason why Fury Road looks so good is results from Miller’s and and his cinematographer’s decision to avoid the look of most post-apocalyptic movies. Anne Thompson describes their approach: “The cliches of the genre were to desaturate the cinematography. So he and great Australian cinematographer John Seale (dragged out of retirement), saturated the color. ‘We were able to change the skies, and go against the idea that because it’s the apocalypse, there’s no longer any beauty in the world.'” (AC, June 2015, p. 48)

There are desert areas of Africa where the sand is the rich, peachy color that appears in the film. The Namibian desert, however, is not so colorful.

(George Miller, in the official Warner Bros. making-of publicity short)

The film’s senior colorist, Eric Whipp, describes the challenge of differentiating the largely brown, beige, and grey colors of the costumes and vehicles from such backgrounds: “The desert sand in Namibia is, in reality, closer to be gray color, but pushing it toward rich gold colors complemented the characters and vehicles, providing a strong, graphic look. The only other dominant color in the film was blue sky, which we embraced.”

The transformation of the desert into rich yellow and orange tones was done with what was obviously aggressive digital color grading. It runs marvelously counter to the dull blues, browns, and grays that form the dominant look of so many action films.

[May 31: On fxguide, Ian Failes has posted an excellent piece that lays out the practical vs. the digital effects in Fury Road.]

LOTR vs. The Hobbit

Reading Lowry’s comments made me think of Andrew Lesnie, who died recently at the young age of 59. Lesnie had unintentionally played a small but pivotal role in my attempts back in 2002-2003 to get permission to interview the Lord of the Rings filmmakers for my book, The Frodo Franchise. I needed to contact someone high in the production who could be a sort of sponsor for me, helping to gain New Line’s cooperation. The only people I figured could do that would be producer Barrie Osborne or Peter Jackson or Fran Walsh.

In November 2002, I was at a conference in Adelaide, Australia and met Annabelle Sheehan, who at that time was an administrator at the Australian School of Film, Radio and Television. When I told her of my potential project, she offered to put me in touch with Lesnie. I hesitated before responding. I knew that it would be wonderful to interview him, but my subject didn’t relate to cinematography at all. Moreover, he wasn’t in a position to sponsor such a project. Then Annabelle offered to introduce me to Barrie Osborne, which subsequently happened via email. The project became real at that point.

I’ve always regretted that I had no excuse to interview Lesnie. From interviews and his appearances in the supplements for the extended DVD editions of LOTR, he seems a genial man. I also admire the cinematography for LOTR. There’s a great variety in the lighting schemes, and he contributed some very striking moments to the film.

It’s of course very difficult to pin down exactly what Lesnie’s contributions to LOTR were in many scenes, given the considerable dependence on CGI. Still, I think he probably had more affect on the final look of LOTR than he did on The Hobbit. As the three parts of The Hobbit came out, it became increasingly clear that there were no shots or sequences that could stand comparison with the best things in LOTR. I think of well-conceived, dramatic shots like the one in The Fellowship of the Ring where a scene begins with a bucolic view out over a misty morning in the Shire, which is suddenly interrupted by ominous music and the entry from offscreen of one of the Black Riders’ horses.

Another shot I admire is the first exterior after the long sequence of the passage through the Mines of Moria in Fellowship. Gandalf has just fallen into the abyss with the Balrog, and the others flee. The cut to an extreme long shot of the rocky terrain (filmed on Mt. Owen) outside the eastern gate to the Mines is jolting, seemingly switching from a color film to a black-and-white one. A trace of green plants at the lower left is virtually unnoticeable, and only as the camera arcs around to follow the remaining Fellowship’s movements away from the gate (which was added digitally) does a bit of blue sky appear at the upper right and eventually the green of the landscapes in the distance.

Although there are plenty of New Zealand locations in The Hobbit, I can’t think of any that are used as effectively as some of the ones in LOTR–most memorably the Edoras set, which was built full-size on Mount Sunday on the South Island. The swooping helicopter shots around the rocky promontory, with the snowy mountains revolving slowly around it, became iconic moments in the film.

Viewers might think that those background mountains were added digitally, and certainly some scenes, including the ones set at Orthanc, did have backgrounds built up of mountains from a variety of places. The extreme long shots of Rivendell are a patchwork of elements. Not so for Edoras, however. David and I were privileged to fly around Mount Sunday in a small plane–after the Edoras set had been removed–and we saw more or less what one sees in the film.

It was a different time of year, November (the Southern Hemisphere’s equivalent of May), but the mountains are clearly the same ones.

There was a helicopter camera team, so Lesnie might have had nothing to do with these circling shots, nor with the mountain photography for the magnificent Beacons Sequence in The Return of the King (to which the fires were added digitally).

Again, there is nothing to compare with this in The Hobbit, which, I would say, suffers from having so many sequences with CGI-created landscapes.

The only really memorable shot I can think of from The Hobbit is entirely digital, the emergence of Smaug from Erebor, covered in gold, at the end of The Desolation of Smaug. He bursts through the door and soars up away from the camera, shaking the gold off in sparkling droplets.

The shot of the dragon’s death is nearly as impressive, as Smaug falls slowly downward away from the camera.

The problems with The Hobbit arise, I think, because so much of it, especially in the third part, has been conceived as almost entirely digital. Compare these two pre-battle moments from The Return of the King and The Battle of the Five Armies.

As Théoden addresses his troops before their charge during the Battle of the Pelennor, we are clearly watching real riders on real horses, their spears held at various angles. To be sure, the MASSIVE program was used to multiply horses and riders, but primarily in the extreme long shots. Hundreds of real ones were used in the scene. In the background we again see impressive non-CGI snow-covered mountains. There are four characters here about whom we care: Théoden, Éowyn, Merry, and Éomer. The Battle of the Five Armies shot of Thranduil’s troops, in contrast, involves perfect ranks of anonymous Elves, moving in synchronization. There is no actual landscape behind them, just vague patches of blue, brown, and white.

MASSIVE was used here as well, but for far more figures. Wasn’t the program devised to allow digital “extras” to move independently of each other rather than replicating a very limited number of gestures? It’s ironic, since in the film’s endless battle, characters moving in synchronization seem to be the rule. See the moment when the dwarves assemble their shields into a wall against the orcs, with Elves leaping effortlessly over them.

Which brings up the matter of seemingly weightless characters and creatures. There has been much discussion of the fact that Legolas and Tauriel leap about, stand on other characters’ heads while fighting, and bound up collapsing stone staircases. Admittedly, Tolkien says in the blizzard scene of The Fellowship of the Ring that Legolas’ “feet made little imprint in the snow.” But even assuming that Elves are very light, some of the antics in The Hobbit look plain silly.

And it’s not just Elves that zip about in this fashion. Partway through the Battle of the Five Armies, large rams appear out of nowhere. (I gather that their presence will be explained in the extended edition.)

Thorin, Kili, Fili, and Dwalin ride the rams up the sheer pinnacle to reach Azog’s command post. The rams bounce weightlessly and effortlessly up the steep cliffs, looking more like ping-pong balls than heavy animals. Indeed, gravity seems to be defied quite a bit in the films–even putting aside from the fact that the characters are able to survive impossibly long falls without a scratch. I can’t think of cases in LOTR where such things happen.

Much has been made of the fact that The Hobbit contains many echoes of LOTR, in terms of characters, scenes, and even specific repeated lines. I’ve complained about that myself. Yet there are many fans who prefer The Hobbit to LOTR–many of them fangirls obsessing over Richard Armitage (Thorin), Aidan Turner (Kili), Dean O’Gorman (Fili), and/or Lee Pace (Thranduil). Such fans proudly point to the “fact” that the second trilogy had higher box-office totals than did LOTR. In unadjusted dollars, yes. In adjusted dollars, LOTR made considerably more, and that without the benefit of 3D surcharges. I suspect this disparity arose from the fact that LOTR was so extraordinarily original, and because it balanced CGI and practical effects so effectively. The Hobbit tipped far in the direction of CGI, and it shows.

Many studios and filmmakers will continue to rely on the standard look of action/sci-fi/fantasy CGI, at least until it becomes so obviously repetitive that audiences lose interest. But films like Fury Road and LOTR offer models of how CGI and practical effects can be balanced for a much livelier film.

[April 18, 2016: Ex Machina, to the surprise of many, won the Academy Award for best special effects. This was probably because it was so original in its use of effects. After all, most special effects doesn’t equal best special effects.]

BIRDMAN: Following Riggan’s orders

DB here:

In a Broadway bar, the New York Times drama critic has just told Riggan Thomson that her review will destroy his play. Riggan snatches up her review of another production, reads it quickly, and declares it packed with meaningless “labels.”

There’s nothing in here about technique. There’s nothing in here about structure. Nothing here about intention.

Happy to oblige, Mr. Thomson. Spoilers ahead.

Structure: Icarus rises

Birdman’s plot covers six days at a critical period in Riggan’s life. He’s an over-the-hill movie star identified with playing the crime-fighting superhero Birdman. Now he’s directing and starring in a play he has based on Raymond Carver’s short story “What We Talk about When We Talk about Love.” The film’s plot starts on the day before the first preview, when during a rehearsal Riggan hires the arrogant but talented actor Mike Shiner. Three nights of more or less bungled preview performances follow. The climax comes on opening night. In the play’s suicide scene, the despondent Riggan shoots off his nose. The Times critic publishes a rave review and Riggan, recovering in the hospital, finds that he has a Broadway triumph. His response to that, however, is rather ambivalent.

The film feels a little odd—“quirky” is the official term—but its blend of comedy and drama is constructed along familiar lines. The major characters have goals. Riggan wants to prove he can do something valuable, while paying homage to Raymond Carver, who encouraged him when he was starting out on the stage. Riggan is also disturbed by his failures as a father and husband; mounting this play about love would seem to be an act of penance. The protagonist’s search for authentic success and psychological stability might remind you of 8 ½ and All That Jazz, which also endow their protagonists with flamboyant fantasy lives.

The other characters state their goals in that confessional mode typical of melodrama. (Extra motivation: in the world of the theatre people are always ready to overshare.) Mike wants to express himself artistically and to make Riggan’s play conform to his standards of honest realism. Lesley, the female lead and Mike’s girlfriend, wants to make her Broadway debut a success. Jake, Riggan’s producer, is trying to pull the whole thing off. Riggan’s scowling daughter Sam is looking for a settled life after a stint in rehab, while Riggan’s girlfriend and second lead Laura wants to have a child. As the plot develops, in true Hollywood fashion, the major characters achieve their goals.

Structurally, the plot falls into the four parts that Kristin has found to be common in Hollywood features.

The Setup lays out the premises for the action—identifying characters, explaining their motives, and articulating their goals. It’s packed with exposition, ranging from the old standby in which a character announces what the other character knows (“You’re my attorney. You’re my producer. You’re my best friend”) to the meeting with the press in which Riggan’s past as a movie star and his hope for this production are redundantly laid out. The thirty-minute setup ends with the first botched preview and Riggan’s moment with his ex-wife Sylvia. He explains that the production means everything to his self-respect.

The Complicating Action, a counter-setup which redirects character goals, centers mostly on the effects that Mike has on the show. Since he drunkenly improvised during the first preview, Riggan realizes they have to come to some understanding. Mike’s onstage antics in the second preview threaten Lesley’s hopes for a breakout career. They break up, and Mike and Sam begin flirting. Mike also steals the spotlight in a newspaper feature about the production, even swiping Riggan’s story about Carver’s encouragement. More deeply, Mike’s rants against Hollywood make Riggan feel even more fearful that his play will be a disaster and he’ll be a laughingstock. All of these anxieties come to focus in an extended inner dialogue between Riggan and Birdman, who insists that he will fail and will have nothing left. Riggan is ready to cancel the show, but Jake pushes him forward.

About an hour in, near the midpoint, we get the Development. This typically consists of a holding pattern. The plot doesn’t advance much. Riggan’s conflict with Mike deepens and his worries about the show mount. Lesley thanks him for giving her a chance, he reprimands himself again for being a bad dad to Sam, and Sam and Mike become a couple. A comic interlude, probably the film’s most widely-known scene, adds to Riggan’s debasement. He’s locked out of the theatre and, wearing just his underpants, races around the block through a Times Square crowd.

Reentering the theatre, he plays the crucial motel scene by lurching down the aisle and onto the stage, where he enacts the suicide. It’s also during the Development that Riggan meets Tabitha, the Times critic, and learns that, sight unseen, she plans to roast his play. The next morning his fantasies take over and, urged by Birdman, he enjoys a swooping and soaring flight around the theatre district.

The fourth part, the Climax, begins with the intermission during the premiere. The audience drifts onto the sidewalk, praising the first act. Backstage Riggan tries to calm his nerves. After confessing to Sylvia that he once tried suicide, he takes the pistol on stage and prepares for the motel scene. On stage, as if succumbing to Birdman’s rhetoric, Riggan confesses, “I don’t exist.” He blasts off his nose. After a brief montage, the epilogue shows us the result. Recovering in the hospital, Riggan has a successful play, a sympathetic ex-wife, and a daughter reconciled to loving him. Even Birdman, sitting on the toilet, is for once silent.

But the very last moments are equivocal and for once you won’t get the spoiler from me. Suffice it to say the tag is ambiguous in magical-realist fashion.

The plot helps us trace character change along classical lines. Key locales mark phases of the action. Sam and Mike meet on the rooftop twice, Riggan visits the bar twice, and Riggan’s ex Sylvia comes to his dressing room once in the Setup and once in the Climax. Whenever we return to the stage we see a version of either the apartment quarrel or the motel suicide. (We do glimpse, also twice, a hallucinatory scene of dancing reindeer, associated with Laura.) The main arenas are the stage and Riggan’s dressing room, which is the site of eight major scenes. The corridors snaking around the theatre serve as transitional spaces. As the film goes on, González Iñárritu tells us, the corridors get narrower and dingier. The fairly rigid time-structure of the plot finds a counterpart in a to-and-fro spatial pattern that measures Riggan’s jagged decline.

I’ve barely mentioned one of the crucial factors in the film’s narration. From the start Riggan hears the voice of Birdman admonishing him to return to superhero movies and give up this arty stuff. At certain points, it seems that Riggan gains some telekinetic powers, enabling him to smash flower pots, furniture, and light bulbs with the wave of a hand. These moments can be construed as subjective, in the sense that he “actually” destroyed them in a normal rage but felt that he was disposing of them through a superhero’s powers.

These powers are suggested at the start with an image of him levitating during meditation. They come to a kind of climax when he launches himself, a trench-coated Birdman, into the air, in a flight that serves as a counterweight to the humiliation of his naked canter through Times Square. Again, the film’s narration suggests that it’s all in his mind: after he lands and returns to the theatre, a cab driver pursues him demanding his fare.

The nagging voice of Birdman supports another kind of structure, a thematic one pitting East Coast and West Coast values. The material is traditional, being given sharp expression in The Band Wagon. The opposition goes back at least to Twentieth Century (1934, a Hollywood satire on Broadway pretensions) and Merton of the Movies (1922, a Broadway satire on Hollywood vulgarity). Of course the two artforms feed off one another. Twentieth Century started as a play, and Merton was made into a movie. The Producers began as a movie mocking Broadway, it became a hit Broadway musical, and the musical was made into another movie.

Birdman revisits these well-worn themes. Mike and Tabitha excoriate Riggan for his trashy films; only the theatre is real art. By contrast, Birdman’s croaking whispers remind Riggan that millions of ordinary folk like his blockbuster movies, while the theatre is for phonies. Mike’s narcissism and pretentiousness, the absurdity of his notion of realism, and the snobbishness of Tabitha all support Birdman’s point. As is common in such movies, the Eastern elite is shown as a pushover for superficial seriousness and ham acting. At the same time, Riggan sincerely wants to pay homage to the emotional core of Carver’s story; he may just not realize how bad the idea is.

The eternal Hollywood/Broadway opposition is sharpened in the light of new entertainment trends. Birdman tells Riggan that old superheroes—presumably those of the vintage of Michael Keaton in Batman (1989)—have it all over “posers” like Downey and the new generation. This motif refers, I think, to the modern trend toward troubled superheroes, set up in Burton’s Batman and carried to neurotic extremes in later comic-book sagas. But of course Riggan personifies the troubled superhero himself.

The sense of Riggan being old-school is reinforced by another familiar thematic duality, that of the young versus their elders. Riggan’s conflict with his daughter recycles the motif of a father so obsessed with work and seduced by false values that he ignores his daughter. (What is it with our filmmakers and this father/daughter thing? Is it just a way to pair older men with cute younger women in a safe way?) Sam berates him for being invisible in today’s world.

You hate bloggers, you mock Twitter, you don’t even have a Facebook page. You’re the one who doesn’t exist. . . . You’re not important. Get used to it.

The modern definition of entertainment includes the Internet, a realm that Riggan enters only by accident during his skivvy promenade. Sam’s denunciation reiterates Birdman’s insistence that Riggan doesn’t exist, except that she makes it worse: even if he returned to the Birdman role, no one would care.

The presentation of superheroics in Riggan’s fantasy mocks summer tentpoles, and would appear to express director Alejandro González Iñárritu’s distaste for action extravaganzas. But the movie is pretty hard on the theatre world too. It’s unfair for Mike and Tabitha to castigate Riggan now that playing a superhero has become artistically legitimate. The only performers Riggan can imagine replacing his wounded cast member are accomplished actors (Harrelson, Fassbender, Renner) who also star in franchise entertainments. The new entertainment economy shows that Riggan was a pioneer; now everybody wears a cape. But these stars routinely do serious films, even Broadway drama, along with tentpole movies. Why can’t Riggan cross over too?

The disruption that arrives when popular entertainment invades the sacred space of the theatre finds a hallucinatory expression during the climactic montage. Now street drummers and superheroes crowd the stage of the St. James. What price Tabitha’s Art of the Theatre with Spidey drawing big crowds?

At the end, Riggan earns his accolades as an actor, but what he’s been after, hinted at in the references to Icarus and the liberation of his flight over the city, is validation of his worth. Once he realizes he is indeed loved (by ex-wife, daughter, best friend), he’s happy to pay the price of his nose. He gains a new superhero cowl, a gauze-bandage mask, and a surgical version of Birdman’s beak. And now that flight is no longer fleeing, he can consider all his options.

Technique; or, Intensified continuity without cutting

This plot could easily have been presented in a manner typical of today’s moviemaking, both indie and mainstream. That is, there might have been hundreds or probably thousands of shots. But Birdman, we’re told by people who should know better, consists of a single shot.

Any viewer can see that’s not true. Depending on how you count the opening quotation from Raymond Carver (is it part of the credits, or a separate shot?), there are sixteen discernible shots in the movie. Apart from the titles, the opening gives us three quick images—a seaside landscape with jellyfish, two shots of a plunging comet—and the final portion of the film provides a montage of nature scenes, interiors, and stage performers.

Admittedly, these shots account for little of the running time. The bulk of Birdman consists of what appears as a continuous shot running a little over 101 minutes. In production, several shots were merged seamlessly into the one that we perceive. The hospital epilogue consists of another long take, that lasting about eight minutes, and it too may have been assembled from separate takes.

Filmmakers confront a lot of options for handling long takes. The boldest, probably, is the static framing that doesn’t use camera movement. This option is employed in early cinema (viz. the Lumiêre films), in the tableau tradition I’ve gabbled about fairly often, and by some very rigorous directors like Hou Hsiao-hsien, Andy Warhol, and Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet. But most films using long takes rely upon camera movement.

In Birdman, unsurprisingly, the camera movements are typical of Hollywood’s modern intensified continuity style. For example, we often get the push-in on a character close-up.

We get orthodox Steadicam movements trailing a character from behind or backing up as he or she strides toward us. This yields the familiar walk-and-talk.

And we get the standard treatment of people around a table, with the camera circling it to pick up each one’s reaction at a critical point.

To a great extent, then, Birdman’s long-take style stitches together schemas that are well-established in contemporary Hollywood. Another current device is the occasional depth shot yielded by wide angle lenses. This technique was well-established in Hollywood in the 1940s, and today’s filmmakers rely on the same sort of tools that classic cinematographers used: strong lighting and wide-angle lenses.

The wide-angle lenses used on Birdman, only 14mm and 18mm, don’t always create wire-sharp focus in depth, but they provide enough visibility to create depth effects. Sometimes the rear plane is made sharper through racking focus.

More pervasively, in many long-take films, the camera movements replicate the patterns we find in an edited scene. Editing gives the camera a kind of ubiquity: it can go anywhere. Tethered to unfolding time, the long take sacrifices the ability to change views instantly. Yet in such films the action is staged and framed so that nothing important escapes our notice. The action gets spelled out as precisely as it would if the scene were edited.

People have wondered a lot about the hidden edits that blend Birdman‘s long takes, but more important, I think, are the ways that the style adheres to standard editing patterns within its long takes. For example, the over-the-shoulder angles of shot/reverse-shot are mimicked by a camera arcing to favor first one character, then another.

We can get shot/ reverse-shot effects via mirrors.

A pan can also approximate a point-of-view shot, as when Tabitha sees Riggan at the other end of the bar.

Throughout, the ensemble staging motivates shifts that would normally be covered by cuts. Mike and Riggan are seen from behind the bar, but when customers spot Riggan and ask Mike to take a picture, the camera sidles around the bar.

As Mike and Riggan turn back to the bar we are effectively 180-degrees opposite to the first setup.

With cutting, a similar shift would have been motivated by changing the axis of action through shifts in staging.

Long-take shooting can’t mimic editing perfectly. An unbroken shot doesn’t yield the instantaneous change of angle supplied by a cut. But the scene can’t be allowed to go dead while the camera operator shifts to a new spot. So the interval between one sustained angle and another has to be filled up by dialogue and physical action. One way to motivate the change of camera position is through the actors’ changing positions. In the bar scene, the fan’s photo op motivates the camera move.

Alternatively, the actor’s gestures can provide some wedged-in bits. When Riggan and his wife have an intimate talk at his dressing table, he executes some business with a beer bottle that justifies shifting the angle to favor him.

Once we’re on him, he turns serious and the dialogue and facial expression motivate a push-in.

In normal shooting and cutting, the technique is fitted to the unfolding action. With a commitment to the long take, the director must fit the action to the technique. This is why, I think, González Iñárritu and his DP Emmanuel Lubezki spent months blocking the action on a sound stage and hiring stand-ins to move around the sets they’d built. Long before the actors came on the set, the filmmakers had mapped out many wedged-in bits of action they’d execute.

Giving up cutting forces other storytelling decisions. A narrative film typically distributes knowledge among its characters, and so the long-take camera must carve a path through the story world that either restricts or expands what we know. The mobile long take sticking with one character tends to restrict our knowledge. The long take that shifts among characters gives us a wider range of information. And whenever one character leaves another, there’s a forced choice: Which one does the narration follow? This is a choice in any storytelling medium, but in the long-take film the options are narrower: the issue is which one the camera will follow.

Birdman stays mostly with Riggan, but in the Complicating Action and Development sections, the narration needs to give us information on the doings of Mike, Lesley, and Sam. So, in another act of fitting and filling, the choreography must make those characters adjacent to some other action. The mazelike playing space of the film, in the bowels of the theatre, facilitates these comings and goings, so that we can drop one character and pick up another. When Lesley and Laura kiss, Mike interrupts them and Lesley hurls a hair dryer at him. He ducks out.

We could stay with Lesley and Laura, or follow Mike. We follow Mike so that we can shift to the new scene, with him visiting Riggan to complain about the pistol and then joining Sam on the roof. Nothing more of consequence will happen between Lesley and Laura; following Mike will lead us to the next story bit. The camera sees all that matters.

The long take’s muffled mimicry of orthodox editing pays some dividends. Arcs and short pans work when characters are close together, but if an encounter is played out in medium shot and one character pulls away, the camera is forced to pick a target. Whom will it follow? This effort becomes quite expressive when Mike is punching up Riggan’s table scene. Just as Mike takes over the rewriting of the lines, he hijacks the camera.

Things start with the usual circling shot.

As Mike’s pitch builds, he breaks from the neutral two-shot and circles Riggan. The camera favors him as he walks off, returns to the table and exhorts Riggan to turn up the tension. (“Fuck me!”)

Now that the two are in proximity, we can see Riggan, infected by Mike’s energy, deliver a more spirited line reading.

The scene ends with a segue to the next passage of walk-and-talk, as Sam comes onto the stage in depth.

In such scenes, the obstinate commitment to the long take itself motivates a dramatic effect. Later, Sam’s tirade about Riggan’s irrelevance gains force because the camera swings to her and stays fastened there.

In a cutting-based scene, there would have been the temptation to show Riggan’s reaction while Sam is unloading on him. True, we could get the same delayed revelation of his response by letting her tirade play out before cutting to him. But given our tacit adherence to the long take, and given the initial framing, we can’t see both of them. The refusal of editing itself justifies holding on her and suppressing his response. In the same way, showing her somewhat chastened pause and then following her walking past him motivates finally revealing his reaction.

A bonus: This scene’s concealment of the reverse angle—what is Sam seeing?—anticipates the film’s final image.

What about the long take’s effect on time? The plot’s tension relies upon the pressure of time. A great many actions are jammed into a short, continuous span. This is a common effect in films built around both a deadline and a confined space. Birdman‘s long take, with its rapid tracking movements and hurly-burly entrances and exits, enhances the pressure. But we need to note how much this result relies on another sort of “hidden editing.”

We often hear that the long take ties us to “real time.” And clock duration, with one minute onscreen equaling one in the story, is indeed a convenient, normative default. Yet suitably cued, a long take can halt duration in the present to give us flashbacks, as we’ve seen at least since Caravan (1934). Films by Angelopoulos, Jancsó, and others have shown that the long take can compress or expand story duration, and even replay events. The remarkable Iranian single-shot feature Fish and Cat of 2013 is full of ribbon-candy time wrinkles.

Once more, Birdman plays it straight. Like a normal movie, it uses sound bridges and night-to-day transitions to skip over stretches of story time. The film is a clear-cut example of the difference between story time (the years of Riggan’s career and the others’ lives), plot time (six days), and screen time (about 110 minutes). The central long take creates ellipses akin to traditional scenic links, and it does so in ways that are easy to grasp as we’re watching.

Intention: The expected virtues of ignorance

The crucial creative decision behind the film was the choice to shoot the extended take. González Iñárritu asserts that he didn’t model the technique on Rope but rather on the long takes of Max Ophuls. He also acknowledges that he was enraptured by Aleksandr Sokurov’s Russian Ark, a feature film that was indeed shot in one long take (thanks to video, but without CGI blending).

The status of the long take has changed across the history of film. In the first twenty years or so, it was more or less taken for granted as the most basic way to shoot a scene. Longer takes became rarer in most national cinemas during the 1920s, with editing becoming the preferred technique for building up action. Even complicated camera movements were consigned to comparatively brief shots.

The long take in today’s sense emerges most vividly in the early sound period, when directors began to use it creatively. During the 1930s, some long takes would be static or relatively so, in films like John Stahl’s Magnificent Obsession (1936) or musicals, especially those featuring Fred Astaire. Other long takes would make extensive use of camera movement. A great many early talkies begin with a fancy traveling shot before moving to more orthdox, editing-driven scenes. And the musicals of Busby Berkeley flaunted outrageous crane shots. In Japan, the USSR, France, Germany, and many countries, the sound cinema brought a renaissance of long takes, propelled by camera movement.

For the most part, this technical choice was felt to serve the story. You sustained the shot because the rhythm of performance benefited, or because you wanted to explore a space through a camera movement. In Dreyer’s Vampyr (1932), the tracking shots are designed to create uncertainties about where characters are when they go offscreen.

Behind the scenes, though, the filmmakers felt a certain pride in making a solid tracking or crane shot. A lengthy camera movement was a challenge because the cameras were big and bulky, they had to roll smoothly on tracks or other supports, lighting had to be controlled carefully, and equipment noise might be picked up.

Despite the difficulties, in the 1940s, some American directors seemed to have welcomed longer takes. The new interest probably owed something to new technology, such as the crab dolly’s ability to edge the camera through narrow spaces and turn in many directions. With complex camera movements easier, the takes could become longer. At a time when most films averaged eight to ten seconds per shot,Otto Preminger could make Daisy Kenyon (17 seconds), Centennial Summer (18 seconds), Laura (average 21 seconds), and Fallen Angel (33 seconds). There were as well Billy Wilder with Double Indemnity (14 seconds) and A Foreign Affair (16 seconds), Anthony Mann with Strange Impersonation (17 seconds) , and John Farrow with The Big Clock (20 seconds). This isn’t to mention the big long-take films of the period from The Lady in the Lake to Rope and Under Capricorn. The opening of Ride the Pink Horse contains a remarkable long-take tracking shot, and one shot in Welles’ Macbeth consumes a full camera reel.

It seems that for some directors sustaining the take was itself the main concern. The more complex the locale—a crowded room, a busy street, an overgrown landscape—the more that the sustained camera movement would be considered, at least by those in the know, as a difficult technical accomplishment.

The result was virtuosity, but with an alibi. Long takes are flashy. But…they can save money. (All those script pages covered fast, no need for editing.) They can be justified as realism. (The action can build over “real time.” Besides, don’t we see reality in a “continuous shot,” not cuts?) They can be motivated as subjective. (By staying with a character over a stretch of time, we become identified with him or her.) Regardless of these reasons, or excuses, there’s an undeniable bragadoccio associated with the protracted camera movement. Your peers in the industry will recognize what you’ve done, and cinephiles will applaud your bravado.

The Movie Brats seized on the virtuoso camera movement and long take as a mark of prowess. A new competition sprang up between Scorsese and DePalma, encompassing Raging Bull, Bonfire at the Vanities, Goodfellas, and Snake Eyes. Even a straight-to-video heist movie like Running Time (1997), choosing to hide its cuts in the Rope manner, has a bit of playground swagger. (Bruce Campbell is in it too.) No wonder that Christine Vachon remarks that shooting a whole scene in one is a “macho” choice.

It’s in this context that we can appraise González Iñárritu’s declared intentions. He was clearly drawn to the virtuosic side of the very long take, and his DP Emmanuel Lubezki had made the complex camera movement his signature with Children of Men and Gravity. After Snake Eyes showed that CGI could stitch together several long takes into a seamless whole, many directors saw that digital filmmaking could extend the shot beyond anything in analog cinematography. A new level of virtuosity was called for, not only the logistics of choreography but the skills of hiding the cuts. Do it right, you might even get tossed an Oscar or two.

The filmmakers justify Birdman‘s technique on familiar grounds. There’s realism:

We are trapped in continuous time. It’s only going in one direction. . . .This continuous shot [yields] an experience closer to what our real lives are like. (González Iñárritu)

There’s subjectivity.

I thought [the continuous take] would serve the dramatic tension and put the audience in this guy’s shoes in a radical way. (Lubezki)

To really not only understand and observe, but to feel, we have to be inside him. [The one shot] was the only way to do that. (González Iñárritu)

Is it showoffish? No, it serves the story.

All the choices we made were serving the purpose and dramatic tension of the characters, not about “Look how impressive we can be.” All the shots were meant to serve the narrative of the film. (González Iñárritu)

But there’s still virtuosity—art conceived as a triumph over self-imposed obstacles.

It was risky! Every scene—good or bad—I had to leave in. It was an endless strand of spaghetti that could choke me! Every note had to be perfect. (González Iñárritu)

I’ve never cared much for González Iñárritu’s films; they always seem too close to their influences. (My remarks on Babel are here.) Still, Birdman seems to me a fascinating example of how traditions can be revisited, or at least repackaged. I can also appreciate the skill with which the whole affair has been brought off. But I also wish that critics and mainstream filmmakers would be more accurate and comprehensive when talking about film form and style. Birdman isn’t a single-shot movie, and to insist on that point isn’t just pedantry. Part of the critic’s job is to look at what’s there, and a full account of the movie (which mine isn’t) would need to reckon in the other shots the film presents.

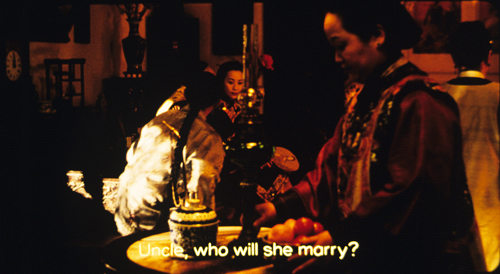

Critics should acknowledge that the long take has other expressive possibilities, some of them impossible to reduce to the patterns of continuity editing. To go back to Hou Hsiao-hsien, Flowers of Shanghai consists of thirty-five shots, nearly all made with a gently shifting camera. But Hou’s mobile long takes retain the intricacy of his static shots in earlier films. The camera may circle the action, but at each moment it’s not only following one character’s movement but drawing into view other movements, greater and lesser, nearer and farther off–the whole thing building up gestures and dialogue and facial reactions, as if by brush strokes, into a rich sense of characters coexisting in a story world and a social system. The result is a gradation of emphasis, to use Charles Barr’s neat phrase, that enriches our sense of the drama.

And sometimes the camera will not see all. Hou accepts the limits of the long take by making some action visible, some action partly visible, and some action unseen, even within the frame. Characters and props slide in to block the main action, sometimes shifting “against the grain” of the camera’s movement. The film’s visual flow doesn’t replicate the schemas of traditional scene analysis; often we must strain to see a gesture or reaction.

Hou’s isn’t the only way to use long takes, but it’s one that deserves more attention. Granted, he and other explorers in this vein will never win an Oscar. But our critics, too often dutifully repeating PR talking points, should signal that the enjoyable virtuosity of Birdman is only one way to employ the rich resources of cinema.

I’ll save for another time a reply to Riggan’s question to Tabitha: “What has to happen in a person’s life for them to become a critic anyway?”

My background information on Birdman‘s technique comes mostly from Jean Oppenheimer’s article, “Backstage Drama,” American Cinematographer 95, 12 (December 2014), 54-67. So does the quote from Lubezki above. A shooting script for the film is here. Information about the concealed digital cuts is in Bill Desowitz’s Indiewire piece.

Kristin’s model of four-part plot structure is discussed in several entries and in my essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture” and the book chapter “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.”

The idea that a camera movement can recapitulate the pattern of analytical editing was floated by André Bazin and developed in detail by John Belton, “Under Capricorn: Montage Entranced by Mise-en-scène,” in his Cinema Stylists (Scarecrow, 1983), 39-58.

For more on the long take, see our entry “Stretching the shot.” The Christine Vachon quotation is linked there, as is De Palma’s sense of competing with Scorsese. The first essay in my Poetics of Cinema discusses trends in long-take shooting and camera movement in the 1940s. See as well Herb A. Lightman, “The Fluid Camera,” American Cinematographer 27, 3 (March 1946), 82, 102-103, and “‘Fluid’ Camera Gives Dramatic Emphasis to Cinematography,” American Cinematographer 34, 2 (February 1953), 63, 76-77. On Dreyer’s camera movements in Vampyr, see my book The Films of Carl Theodor Dreyer. I discuss Angelopoulos, Hou, and long-take staging generally in Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging. On this site, I discuss Hou’s staging practices here and here. And for discussions of intensified continuity style, see The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Two frames from Flowers of Shanghai (1998) are below, showing the camera’s slight movement around the central lantern and Pearl’s face, as well as the shift in the young man’s posture as he waits for an answer to his question. He’s in the process of clearing a bit of space for us to glimpse the older man, Hong, who’s sitting between him and Pearl.

P.S. 24 Feb 2015: Thanks to Paul Mollica for a name correction!

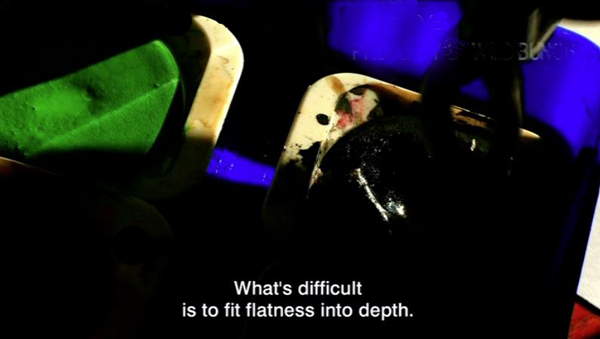

ADIEU AU LANGAGE: 2 + 2 x 3D

Adieu au langage (2014).

DB here:

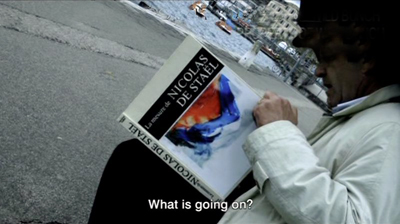

Godard’s Adieu au Langage is the best new film I’ve seen this year, and the best 3D film I’ve ever seen. As a Godardolater for fifty years, I’m biased, of course. And I might feel that I have to justify taking a train from Brussels to Paris to watch it (twice). But the film seems to me superb, and it gets better after several more (2D) viewings.

People complain that Godard’s movies are hard to understand. That’s true. I think they provide two different sorts of difficulty. He lards his dialogue and intertitles with so many abstract (some would say pretentious) thoughts, quotations, and puns that we’re tempted to ask what he is implying about us and our world. That is, he poses problems of interpretation—taking that to mean teasing out general meanings. What is he saying?

I think that this type of difficulty is well worth tackling, and critics haven’t been slow to do it. Scholars have diligently tracked the sources of this image or that barely-heard phrase. Adieu au langage provides another field day; there are movie clips, some quite obscure, and citations (maybe some made-up ones) to thinkers from Plato and Sartre to Luc Ferry and A. E. van Vogt. Ted Fendt has discovered a massive list of works cited in the film, and even his list, he acknowledges, is incomplete.

I confess myself less interested in interpretive difficulties. I don’t go so far as my friend who says, “Godard is a poet who thinks he’s a philosopher.” But I do think that he uses his citations opportunistically, scraping them against one another in collage fashion. In particular, I think that by having characters quote, quite improbably, deep thinkers, he’s trying for a certain dissonance between the abstract idea and the concrete situation.

What situation? That brings us to the second sort of difficulty. It’s often rather hard to say just what happens, at the level of plot, in a Godard film. From his “second first film,” Sauve qui peut (la vie) (1980), “late Godard” (which has lasted over thirty years, much longer than “early Godard”) has made the story action quite hard to grasp. Oddly enough, most reviewers pass over these difficulties, suggesting that story actions and situations that we scarcely see are fairly obvious. (Reviewers do have the advantage of presskits.)

The brute fact is that these movies are, moment by moment, awfully opaque. Not only do characters act mysteriously, implausibly, farcically, irrationally. It’s hard to assign them particular wants, needs, and personalities. They come into conflict, but we’re not always sure why. In addition, we aren’t often told, at least explicitly, how the characters connect with one another. The plots are highly elliptical, leaving out big chunks of action and merely suggesting them, often by a single close-up or an offscreen sound. Godard’s narratives pose not only problems of interpretation but problems of comprehension—building a coherent story world and the actions and agents in it.

We ought to find problems of comprehension fascinating. They remind us of storytelling conventions we take for granted, and they push toward other ways of spinning yarns, or unraveling them.

Case in point: Adieu au langage.

Since the film will be appearing in the US this fall, under the title Goodbye to Language, I want to encourage people to see this extraordinary work. But I’m also eager to talk about it in detail. So here’s my compromise, a four-layered entry.

I’ll start general, with some sketchy comments on some of Late Godard’s narrative strategies. In a second section I make some speculative comments on Godard’s use of 3D. No real spoilers here.

Then I’ll offer an account of the opening fifteen minutes. If you haven’t yet seen the film, this section might be good preparation. But part of experiencing the film is feeling a bit at sea from the start, so this section might make the film more linear than it would appear on unaided viewing. You decide how much of a preview you want.

The last section briefly surveys the overall structure of the film, and it is littered with spoilers. Best read it after viewing.

Spoilers notwithstanding, nothing stops you from eyeing the pictures.

Ecstasy of the image

Film Socialisme (2010).

Much in Adieu au langage is familiar from other Godard films. There are his nature images–wind in trees, trembling flowers, turbulent water, rainy nights seen through a windshield–and his urban shots of milling crowds. All of these may pop in at any point, often accompanied by fragments of classical or modern music. Again he returns to ideas about politics and history, particularly World War II and recent outbreaks of violence in developing countries. His standard techniques are here too. The film begins before, and during, the credits, which appear in brusque slates often too brief to read. Music rises, often just enough to cue an emotional response, before being snapped off by silence or an abrasive noise.

In his narrative films, as opposed to the collage essays like Histoire(s) du cinéma, we get scenes, but those are handled in unusual ways. He tends to avoid giving us an establishing shot, if we mean by that a shot which includes all the relevant dramatic elements. He often has recourse to constructive editing, which gives us pieces of the space that we are expected to assemble. Although Godard’s early films relied on this a fair amount, it became pronounced in his later work, where he tweaks constructive cutting in unusual ways. I discuss one example here.

Often we get an image of one character but hear the dialogue of an offscreen character. And the shot of the lone character may hang on quite a while, so that we wait to see who’s speaking. By delaying what most directors would show immediately, Godard creates, we might say, a stylistic suspense. I can’t prove it, but I suspect the influence of Bresson, who said to never use an image if a sound will suffice.

When Godard doesn’t give us unanchored close-ups or medium-shots, he may do something more drastic. A signature device of his later work is the shot which stages its action in ways that make the characters hard to identify. He may shoot in silhouette (Notre musique, 2003).

More outrageously, he may frame people from the neck or shoulders down (Bresson again?) and make us wait to discover who they are (Éloge de l’amour).

Such decapitated framings are disconcering, since orthodox cinema highlights faces above all other body areas. When we can’t access facial expressions, then the dialogue, gestures, postures, and clothes become very important. Godard can, of course, combine these strategies (below, Éloge de l’amour; also the Film Socialisme image above). In this shot, the man standing in the background is an important character but we never see him clearly.

Godard’s opaque “establishing” shots may be very condensed and laconic; he jams in a lot of information, partial though it is. In one shot of Adieu au langage, a dog approaches a couple on a rainy night and the woman urges her partner to take him in. All we see, however, is the man gassing up the car (and we don’t see him all that clearly).

We hear (dimly) the dog’s whimpering and the woman’s plea, but we see neither one.

Godard frets and frays his scenes in other ways. He creates ellipses, time gaps between shots that may leave us uncertain. What happened in the interval? How much time has passed? He also interrupts the scene through cutaways to black frames, objects in the scene, or landscapes; the scene’s dialogue may continue over these images, or something else may be heard.

At greater length, the scene can open up onto a digression, a collage of found footage, intertitles, or other material that seems triggered by something mentioned in the scene. In Film Art: An Introduction, we argued that one alternative to narrative form is associational form, a common resource of lyrical films or essay films. Godard embeds associational passages in his narratives, the way John Dos Passos embedded newspaper reports in the fictional story of his USA trilogy. Sometimes, though, the associations are textural or pictorial. At one point in Adieu au langage, Godard associates licked black brushstrokes on a painting with churned mud and the damp streaks on the coat of the dog Roxy.

By fragmenting his scenes, Godard gets a double benefit. We get just enough information to tie the action together somewhat, and our curiosity about what’s happening can carry our narrative interest. But the opaque compositions and the bits and pieces wedged in call attention to themselves in their own right. Blocking or troubling our story-making process serves to re-weight the individual image and sound. When we can’t easily tie what we see and hear to an ongoing plot, we’re coaxed to savor each moment as a micro-event in itself, like a word in a poem or a patch of color in a painting.

But those images and sounds can’t be just any image or sound; they hook together in larger patterns that sometimes float free of the plot, and sometimes work indirectly upon it. The best analogy might be to a poem that hints at a story, so that our engagement with the poetic form overlaps at moments with our interest in the half-hidden story.

Where, some will ask, is the emotion? We want to be moved by our movies. I suggest that with Late Godard, we are mostly not moved by the plot or the characters, though that can happen. What seizes me most forcefully is the virtuoso display of cinematic possibilities. The narrative is both a pretext and a source of words and sounds, forms and textures, like the landscape motifs that painters have used for centuries. From the simplest elements, even the clichés of sunsets and rainy reflections, the film’s composition, color, voices, and music wring out something ravishing.