Archive for the 'Digital cinema' Category

12 hours, Ritrovato time

DB here:

Reporting on the magnificent Cinema Ritrovato festival at Bologna has become a tradition with us, but it’s become harder to find time during the event to write an entry. The program has swollen to 600 titles over eight days, and attendance has shot up as well; the figure we heard was over 2000 souls. The organizers–Peter von Bagh, Gian Luca Farinelli, and Guy Borlée–have responded to requests for more repetition of titles by slotting shows in the evening, some starting as late as 9:45. (You can scan the daily program here.) There are as well panel discussions, meetings with authors, and some unique events, such as carbon-arc outdoor shows, the traditional screenings on the Piazza Maggiore, and Peter Kubelka’s massive and mysterious Monument Film. Add in time to browse the vast book and DVD sales tables, and the need to socialize with old friends.

In all, Ritrovato is becoming the Cannes of classic cinema: diverse, turbulent, and overwhelming. How best to give you a sense of the tidal-wave energy of the event? I’ve decided to take off one morning and write up just one day, Monday 29 June. I don’t know when Kristin and I will find time to write another entry, for reasons you will discover.

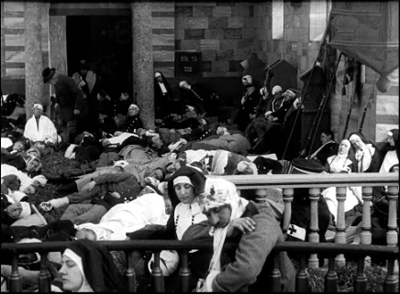

9:00 AM: Ned Med Vaabnene! (Lay Down Your Arms!, 1914) was a big Danish production, based on a popular anti-war novel by the German Bertha von Suttner. It’s a remnant of the days when the rich went to war along with the common folk. (Sounds quaint in today’s America, where the elite have other priorities.) The Nordisk studio specialized in “nobility films,” melodramas that show the upper class brought low by circumstances; Dreyer’s The President (1919) is another example. The film, directed by Holger-Madsen, shows a family devastated by war and its aftermath. It’s shot in tableau style, with the restrained acting and sumptuous, light-filled sets characteristic of Nordisk. The combat scenes are remarkably forceful, but the most harrowing scene, for me, is the shot showing a battlefront hospital, with exhausted nuns and wounded men strewn around the shot–a tangle of limbs and heads.

Premiered soon after the Great War broke out, Lay Down Your Arms! anticipates Nordisk’s wartime policy. Denmark was a neutral country, and the Danish industry depended on both the German and the American markets. As a result, most of the films studiously avoided taking sides. After the war, with the revival of the German industry and the circulation of American films in Europe, Nordisk lost its powerful position in the international market.

The entire film is available for viewing online at the Danish Film Institute site.

Programmer Mariann Lewinsky, in charge of the “100 Years Ago” thread, wisely included other pacifist films from the mid-teens. One of the high points was the evening screening, on the Piazza Maggiore, of the fine Belgian film Maudite soit la guerre (1914), in the hand-colored version I discussed some years back. Not by accident, I suspect, Lay Down Your Arms! featured several Lewinsky dogs.

10:30 AM: Werner Hochbaum was an unknown name to me, but after seeing Morgen beginnt das Leben (Life Begins Tomorrow, 1933), I realized that was my loss. This story of a cafe violinist released from prison is a sort of anthology of 1920s International Style devices: canted angles, rapid montages, City Symphony passages, flamboyant camera movements, multiple-image superimpositions, and huge close-ups of faces, hands, and objects. The work on sound is no less ambitious, with voice-overs, sound motifs (a carousel, a canary’s call-and-response to a chiming doorbell), offscreen dialogue, and harsh auditory montages of traffic and city life. Everything from Impressionist subjective-focus point-of-view to Expressionist shadow work comes into play.

The plot is gripping throughout. At first we don’t know why the violinist was imprisoned, and we learn about the case first from his gossiping neighbors (excellent run of whispers during fast-cut close-ups of housewives), then from his own flashbacks, which build up to a revelation of the murder he committed. Threaded with all this is another uncertainty: Has his wife begun a love affair while he was in jail? Giving us only glimpses of her life as a cafe waitress, Hochbaum leads us to suspect that he will come home to more misery–and perhaps another temptation to murder.

Along with all this were arresting side scenes of cafe life, like a fat woman ordering up a gigolo to dance with her, reminiscent of Georg Grosz and the New Objectivity’s cynical portrait of daily desperation. It’s a lot to pack into 73 minutes, but Morgen beginnt das Leben succeeds smoothly and made me want more. Alex Horwath‘s introduction confirmed that this is a director we should know better. We can hope that a DVD edition is coming soon.

Noon: A packed house for the panel of three American studio archivists: Schawn Belston of Twentieth Century Fox, Grover Crisp of Sony, and Ned Price of Warners. Too many ideas to summarize here, but one that emerged: Digital tools are great for restoration, not so reliable for preservation.

Ned (left) emphasized that now scanners are very sensitive to the oldest negatives, with their shrinkage and warpage. But Ned pointed out that today’s monitors don’t often render the full color scale needed to respect film’s tonal range, so that weak monitors mean that we are “working blind” and may “bake in” flaws that will be evident when display devices improve. Likewise, low bit-depths (often only 10-bit) in outputting to film for preservation can cause problems later. Grain reduction is another big problem. Grover (center) added: “When you do anything to grain, you’re denaturing the film.”

On the restoration front, Schawn showed clips from the 1959 Journey to the Center of the Earth, first from a beautiful photochemical restoration of twelve years ago, then from a recent digital one. To my eye, the warm skin tones of the 35mm image were more attractive than the almost porcelain surfaces of the digital version, but the latter was sharper and contained a healthy amount of grain. Grover screened A/B comparisons of the main titles of Only Angels Have Wings and Vaghe stelle dell’Orsa (Sandra ), both of which showed how handily digital restoration creates a rock-stable image, without the jitter and weave unavoidable with a strip of film.

All the panelists agreed that digital restorations are rapidly improving; ones finished only a few years ago could now be done better. A major problem coming up is that younger restoration workers know the digital tools better than the look and feel of photochemical, particularly the surface of older films. Grover recalled that one eager techie added flicker to a Capra silent because he thought that was how old movies looked.

1:15 PM: Hurried lunch with Schawn. Main topic: The Grand Budapest Hotel, but also the vagaries of the DVD and Blu-Ray market.

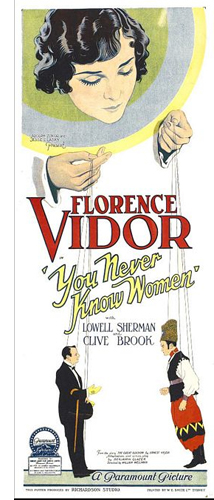

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

2:30 PM: Ritrovato has mounted an ambitious William Wellman series, and though I’d seen most of the films on the program, I had to catch two 1920s titles.

You Never Know Women (1926) is an exercise in good old classical storytelling. The plot presents Vera (Florence Vidor), star of a troupe of Russian entertainers, momentarily entranced by a no-good millionaire who wants to seduce her. The magician of the troupe, Norodin (Clive Brook) loves her, but she’s unaware of her feelings for him until the Lothario’s true nature is exposed. El Brendel adds spice as a clown devoted to his pet duck.

Variety‘s review was ecstatic, claiming that “Wellman at the megaphone lifts himself into the ranks of select directors with by his handling of this story, for his direction is never obvious or old-fashioned.” I’ll say. Filled with running gags, seesawing conflicts, and motifs (Ivan’s skill at knife-throwing, the expletive, “Ridiculous!”), You Never Know Women has a headlong pace. With nearly a thousand shots in 70 minutes, it relies on glances, gestures, and reactions to channel the dramatic flow. It needs only three expository titles, letting its 100 or so dialogue titles pinpoint key emotional transitions. In anticipating the sound cinema that was just around the corner, You Never Know Women resembles the more famous Beggars of Life (1928, given pride of place at Ritrovato), which as I recall uses dialogue titles exclusively.

The Man I Love (1929) tells the familiar story of a prizefighter who, as he rises in the game, leaves his loyal woman behind. As an early sound film, it relies on multiple-camera shooting for extended dialogue scenes, but Wellman enlivens the staging with unusual angles, including a view of a quarrel seen through a window in a dressing-room door. The Man I Love boasts the sort of ambitious, somewhat bumpy tracking shots we sometimes find in early talkies. One swaggering camera movement takes us from the locker room into an arena, down the aisle, past the ring, and to Dum Dum’s anxious wife in the crowd, a sketchy prefiguration of the celebrated Steadicam movement in Raging Bull. The fight scenes, not requiring sync sound, are shot with brio, while the dialogue scenes are extremely well-miked, allowing for fairly fast line readings and varied volume and emphasis in the voices.

Gina Teraroli and David Phelps, along with other colleagues, have assembled a wide-ranging dossier on Wellman’s work that serves as a fine complement to the Ritrovato thread.

5-something PM: One of the things in the first edition of our Film History: An Introduction that made me proud was the inclusion of sections on Indian cinema, a subject usually ignored in textbook surveys. I remember in the late 1980s and early 1990s watching the 1950s-1960s classics of Hindi filmmaking with a sense of discovery: How could we not have known this invigorating tradition? It was therefore with a sense of homecoming that I visited Raj Kapoor’s Awara (“The Vagabond,” 1951), in a pretty sepia-tinted print.

The young ne’er-do-well Raj (no last name, and this is important) is on trial for attacking a judge in his home. A female lawyer, Rita, takes up his defense and urges the judge, on the witness stand, to tell why he expelled his wife from his home many years ago. The wife had been kidnapped by the gangster Jagga, and the judge assumed that the child she was now expecting was Jagga’s. Before the courtroom, Rita recounts up the story of how young Raj, actually the judge’s legitimate son, took up a life of crime. To add spice, Rita is the judge’s ward and Raj’s lover.

No coincidence, no story, they say, and Awara offers plenty of timely misunderstandings and improbably neat encounters. No matter. We’re told that TV narrative, by stretching its tale over several hours, can introduce novelistic breadth, but so can Indian classics of the 1950s. This one takes us across twenty-four years and as many ups and downs as a mini-series might offer. Not to mention Kapoor’s vigorous visual style, with huge sets, vivacious fantasy sequences, and traces of 1940s Hollywood hysteria (chiaroscuro, fluid track-ins to overwrought faces, even thunder and lightning in the distance). Here Raj, about to stab the judge, shatters the childhood picture of Rita; her simple gaze checks his moment of revenge.

Then there are the songs, lusciously sung by Lata Mangeshkar and Mukesh. Of course the sprightly “Awara Hoon” is the official classic and Kapoor’s signature tune, but this time around my favorite was the duet, “I wish the moon…,” with Rita asking the moon to look away and Raj asking it to turn to him. With its glamorized social realism, its tale of a good boy gone wrong, unjustly punished, and eventually redeemed, and its primal themes of mothers, fathers, and sons, Awara is a milestone in the world’s popular cinema…. and just one of several Indian classics in this year’s Ritrovato.

That was one day. Now I’m off to…what? Polish films in widescreen? The Riccardo Freda retrospective? The rare Ojo Okichi? Or maybe the restored Oklahoma!? In any case, this afternoon an incontro on Nicola Mazzanti‘s book 75000 films, and tonight Guru Dutt’s glorious Pyaasa.

I tell you, it’s hard to keep up, running on Ritrovato time.

Nargis and Raj Kapoor sing to the moon in Awara.

Dispatch from another 35mm outpost. With cats.

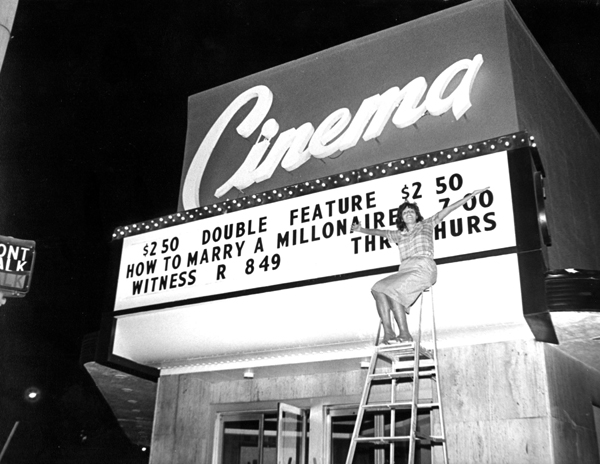

Cinema Theater, 1985, with JoAnn Morreale.

DB here:

For a while now I’ve been tracking the consolidation of digital cinema. After a blog series, I melded the entries with other information and created the e-book Pandora’s Digital Box. (To the readers who bought it, thanks!) Last year, in a blog called “End Times” I updated the information. Now we’re at post-End Times, I suppose.

David Hancock, who keeps meticulous account of these things, issued an IHS Technology Profile report on the state of things at end 2013.

*Of the world’s nearly 129,000 screens, over 112, 000, or 87%, are digital in some format. Most screens are compliant with the Digital Cinema Initiative standard used in the US, but India has pioneered the cheaper “electronic cinema” formats. Many of these e-screens will upgrade to the DCI standard.

*The UK and France have fully converted, along with most smaller European countries. Those countries benefited from various degrees of government support for the conversion.

*China now contains over half of the 32,642 digital screens in Asia.

*High concentrations of 35mm venues remain in Egypt, Morocco, Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and other areas with economic troubles. Other analog countries, such as Slovakia and Slovenia, lack public funding and contain mostly single-screen venues. The more multiplexes a country has, the greater the pressure to go DCI.

*In North America, out of about 40,000 screens, close to 93% have converted. That leaves about 3200 analog venues. It’s hard to know how many of those have closed or will close soon.

Most of the surviving analog sites, I suspect, are subsequent-run, like the five 35mm screens at our Landmark/Silver Cinemas ‘plex. And our Cinematheque and student-run Marquee continue to find and show excellent film prints. But clearly the moving finger has written. We at the University are striving for funding to make the changeover.

So too is a wonderful cinema I visited back in January. A family trip carried me back to my stomping grounds in New York’s Finger Lakes. I’ve already retailed some information about my hometown cinema, and a 1915 film that was discovered there. For now, let me tell you about a theatre I visited during a few days in Rochester.

Let George do it

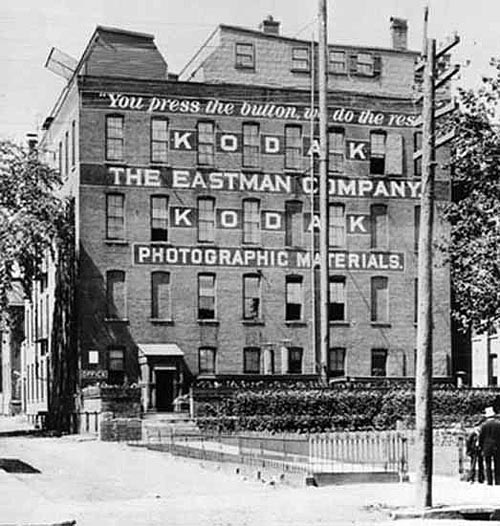

Eastman Company, 1892.

Before there was Hollywood film production there was New York film production. Before that, there was West Orange, New Jersey, where Mr. Edison and Mr. Dickson devised a movie machine. And somewhat before that, before movies themselves, there was Rochester.

Rochester was the home of the George Eastman company, founded in 1880. Eastman pioneered consumer still photography; he made up the word “kodak” to suggest the click of the shutter button. The company manufactured the flexible 35m film stock that formed the basis of the American cinema industry. Another Rochester industry, the venerable Bausch & Lomb provided camera and projector lenses, including those for CinemaScope in the 1950s.

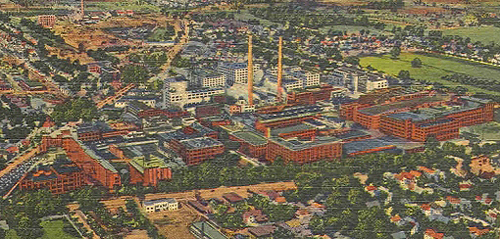

I suppose most people under thirty have never used a film-based camera, and for them the firm’s cheery yellow-and-red logo looks the way an ad for Packards looked to me in my teen years. Throughout most of the twentieth century, though, Eastman Kodak was one of America’s great technology firms. Here’s the Kodak Park facility ca. 1940.

The firm’s tragic decline will eventually get book-length treatments, but a short version is here.

Despite having invented the first digital camera, Kodak was overwhelmed by faster-moving competitors in that realm. As the firm mounted huge losses, the CEO, Antonio Perez, sought to leverage cash through Kodak’s many patents, but that tactic couldn’t stave off disaster. By 2011 Kodak stock was selling at about $1, down from the $25 it had been at when Perez arrived. In the same year, he was appointed to President Obama’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness. Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the following year.

Kodak has tried to reinvent itself, but its collapse has damaged Rochester badly. Growing up, I encountered in Kodak a supreme example of paternalistic capitalism; George Eastman even paid for dental care for all of Rochester’s children. In the 1980s over 60,000 people in Rochester worked at the firm; now fewer than 7,000 do. As the company imploded, its pension funds fell behind. During my stay I met former employees who had counted on a secure retirement and are now struggling to make ends meet. There were also plenty of salty epithets aimed at Perez, who is said to receive an annual salary of over $1 million, along with millions more in other compensation.

Some argue that Rochester as a whole is recovering. If so, it’s a slow climb.

Still, for cinephiles, Rochester remains a remarkable city. There is the historic Little Theater. It’s one of the oldest art houses in the country and now has several screens, all but one of them digital. The theatre has been taken over by the local NPR outlet and presents indie and foreign titles, along with some live music events. There’s also the magnificent Dryden Theatre operating under the auspices of the George Eastman House, one of the world’s great archives. Its programming has always been stellar, and it continues to bring rare films to the city.

Then there’s a real survivor: the Cinema Theater.

The South Wedge upstart

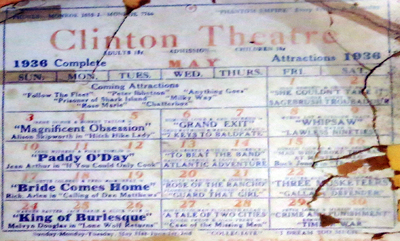

The Clinton Theatre, mid-1930s. The features are In Old Kentucky (1935) and The Return of Peter Grimm (1935).

It opened in 1914, smack in that period when motion pictures became the movies. It was initially called the Clinton Theatre because it occupies the corner of South Clinton Avenue and South Goodman Street. It offered minimal comforts. Donovan A. Shilling, in his colorful and nostalgic Rochester’s Movie Mania, tells of wooden benches and a dirt floor.

Those amenities couldn’t easily compete with the offerings of the Clinton’s more splendid rivals.

There was, for instance, the Piccadilly, opened in 1916. Advertised as a million-dollar house, the Piccadilly was built with a grand stairway and an orchestra pit for a sixteen-piece ensemble. Its auditorium could seat 1500 people in what the trade press announced as exceptionally comfortable seats. A beautiful exterior photo is here. Eventually the Piccadilly became the Paramount. Rochester was a pretty rich city then.

The Clinton closed in 1916, reopened briefly, closed again, and reopened in 1918. This time it held on. Located outside the central theatre district, in a neighborhood known as South Wedge or Swillburgh, the Clinton was a classic neighborhood second-run house. You might have to wait quite a while to see a release, which would play the downtown theatres first. But at least you benefited from a swift turnover. During one week of February 1929, you could see The Big Killing and Bachelor’s Paradise (on a double bill), Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Tim McCoy in Wyoming, The Crowd, and While the City Sleeps, starring Lon Chaney. These titles had been released in spring and early fall of the previous year.

The Clinton wasn’t part of a chain, but it hung on through Hollywood’s biggest studio years. In 1934 it was one of thirty-two Rochester theatres, some of them huge. The Century could hold 2500 people, the RKO Palace 3000. (Of course many such theatres hosted live shows as well.) With capacity of only 500 (about the same as the Little), the Clinton was in the same category as the Aster, the Broad, the Empress, the Hudson, the Lyric, the Majestic, and the Rexy. Admission was typically $.15, and that usually got you two pictures. Bills changed three times a week, with the big pictures running three days.

Surprisingly by our standards, the major films weren’t playing Friday and Saturday. I can’t prove this, but I’ve read that Sunday afternoons and evenings yielded the big audiences for neighborhood theatres–possibly because many people worked six-day weeks. (See the codicil for more information.)

But, as mentioned in an earlier entry, the late 1940s were problematic for exhibitors because attendance plummeted. In 1949, the Clinton was taken over by Jo-Mor Enterprises, a major Rochester chain. Renovated with the Art Deco façade it now has, the newly named Cinema played arthouse fare as well as subsequent-run Hollywood films.

The Cinema was headed for closure in the mid-1980s when it was saved by an unlikely heroine. Earth Science teacher JoAnn Morreale bought it and spent over $100,000 in improvements. She did everything from negotiating with distributors to cleaning toilets.

Her energy made the theatre what it had been in its heyday, a center for community activity. Locals came in with gifts and home-made treats. Some spent the day there, watching the double-feature matinee and the double-feature evening show. Six bucks got you four movies. Here’s the old beauty in 1992.

Two years ago the Cinema was bought by John Trickey. The house is still a second-run venue, but unlike most it still offers double bills. The night I visited with my sister Diane you could have seen Mandela and Gravity in one go. The prices have gone up only a little since the 1980s: $5 for adults, $3 for seniors, students, and kids under 12.

We met the Cinema’s majordomo Benjamin Tucker. By day Ben is a Curatorial Assistant at Eastman House, but he loves film history and is happy to help out the theatre.

The shows are still in 35mm, although Ben is coordinating a crowdfunding campaign to help out digital conversion.

Princesses

We met the staff, including the projectionists and the ticket lady Pat Russo, who has worked there for about ten years. She gives you real pasteboard tickets, not those flimsy, curly multiplex printouts.

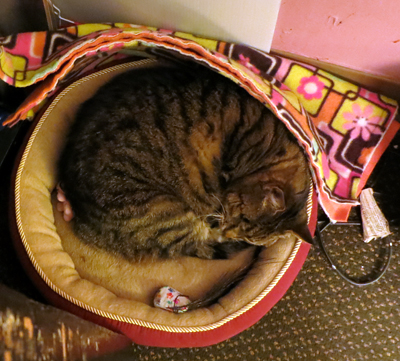

And there’s the proud lineage of Cinema Theater cats, starting with Princess to Princess the second (ruling for about fifteen years) up to Sue, who’s been in residence about six months.

The Princesses would circulate among the seats, startling patrons by rubbing up against their legs or leaping onto their laps. Sue has a habit of settling down for a snooze in the middle of the line at the concession stand, forcing customers to step over her on their way to the popcorn.

I never visited the Cinema in my salad days (the 1960s). It wasn’t playing so much arthouse fare, I think, so I tended to visit the Little or the Dryden. I wish I had sought out the Cinema. This is one of the oldest continuously operating theatres in the country. Long may it flourish.

Thanks to Ben Tucker for information and images, to Jim Healy for tipping me off to the theatre, and to Diane and Darlene Bordwell for their company.

The image of the mid-1930s Clinton comes from Shilling’s Rochester’s Movie Mania; Carl Baxter supplied the original photo. More Clinton/Cinema Theatre memories here. The Rochester Subway site hosts stupendous, recently discovered photos of the RKO and Loew’s picture palaces.

PS 16 March 2014: Alert reader Andrea Comiskey supplies some background on the Clinton’s scheduling three programs per week during the classic years.

Mae Huettig (Economic Control of the Motion Picture Industry, 1944) says that only theaters that did not have to block-book (majors’ affiliates, members of large chains, etc.) got to choose films’ playdates. Whether this was really as absolute as she makes it sound, who knows? But what this means for when the “best films” (typically the A pictures) would tend to appear is tough to determine. On the one hand, you could imagine that distributors would want the strongest, most appealing films showing on the weekends when they could bring in the biggest crowds. On the other hand, you could imagine distributors trying to force underperforming/weaker films onto bills on the busier days since there’d be higher baseline business regardless of the merits of the films on the program. Exhibitors that didn’t get to pick playdates certainly did complain.

In an interview published in Kings of the B’s, (1975) Monogram’s Steve Broidy says that Saturday is the busiest day, at least for small-town exhibs. He also says that these exhibs liked flat-rate rentals on Saturdays so they could run up the profits and echoes the idea that the particular film didn’t matter a ton since people were going out to the movies regardless.

As was the case with your Rochester example, theaters that changed programs 2 or more times a week (which, at least in big cities, were more likely to be sub-run houses) often split the weekend days across two programs, with many theaters adding an extra feature exclusively for the Saturday kiddie matinee. I’ve seen just about every possible permutation, but for a twice-weekly changeover, Sun-Wed & Thurs-Sat was a pretty common pattern. For thrice-weekly, Sun-Tues, Wed-Thurs, & Fri-Sat was common. But I’ve also got plenty of examples of theaters that showed the same program Sat. & Sun.

Andrea is writing a dissertation about distribution and playdate patterns in the 1930s. I’m happy to get her clarification here, which shows, as usual, that film history is always more complicated than it seems at first.

The Cinema, 2014. Photograph by Darlene Bordwell.

Picking up the pieces; or, a Blog about previous blogs

A not-so-intimate bedroom scene from Cinerama Holiday (1955).

DB here:

Many of our blog entries are written in response to current events–a new movie, a film festival in progress, a development in film culture. Later we sometimes add a postscript (as here) bringing an entry up to date. Today, though, enough has happened in a lot of areas to push me to post the updates in a single stretch. It’s a sort of aggregate of chatty tailpieces to certain entries over the last year or so. Should the impulse seize you, you can return to an original entry, and there are other peekaboo links to keep you busy.

Out and about

Drug War.

Kristin wrote in praise of Neighbouring Sounds when she saw it at the Vancouver International Film Festival in 2012. Roger Ebert gave it a five-star rating, and A. O. Scott placed it on his annual Ten Best list. This network narrative is Brazil’s official entry for the Academy Awards. Sample Neighbouring Sounds here; the DVD is coming in May.

The annual Golden Horse Awards at Taipei have finished, and the Best Picture winner was the Singaporean Ilo Ilo, which neither Kristin nor I have seen. It would have to be exceptionally good to match the other films nominated, all of which we’ve discussed: Tsai Ming-liang’s Stray Dogs, Wong Kar-wai’s The Grandmaster, Jia Zhang-ke’s A Touch of Sin, and (probably my favorite film of the year so far) Drug War, by Johnnie To Kei-fung. Stray Dogs did bring Tsai the Best Director award and his actor Lee Kang-sheng a trophy for best lead. Wong’s Grandmaster picked up six trophies, including top female lead and Best Cinematography. Jackie Chan won an award for Best Action Choreography. Although his CZ12 struck me as pretty dismal as a whole, its closing montage of Jackie stunts from across his career was more enjoyable than most feature-length films. In all, this has been a splendid year for Chinese-language cinema.

Back in the fall of 2012, I celebrated Flicker Alley‘s admirable release of This Is Cinerama, a very important film for those of us studying the history of film technology. Now Jeff Masino and his colleagues have taken the next step by releasing combo DVD-Blu-ray sets of two more big pictures, Cinerama Holiday (1955), the sequel to the first release, and South Seas Adventure (1958), the fifth and last of the cycle. Both are in the Smilebox format, which compensates for the distortions that appear when the curved Cinerama image is projected as a rectangle. Fortunately, Smilebox retains the outlandish optics to a great extent. The image surmounting today’s entry would give Expressionist set designers a run for their money, and it recalls the Ames Room Experiments. Cinerama wrinkles the world in fabulous ways.

Filled out with facsimiles of the original souvenir books and supplemented with a host of extras putting the films in historical context, these discs are fine contributions to our understanding of widescreen cinema. Because film archives don’t have the facilities to screen Cinerama titles (if they even hold copies), we have never been able to study, or even see, films that now look gloriously peculiar. Dare we hope that, from The Alley or others, we’ll get The Wonderful World of the Brothers Grimm (1962), a strange, clunky, likeable movie?

Bookish sorts

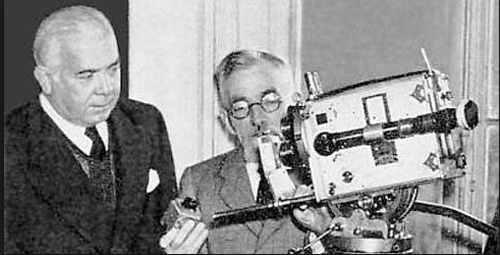

Spyros Skouras and Henri Chrétien.

2013 saw the first of our online video lectures, one on early film history and the other on CinemaScope. The response to them has been encouraging, but as usual nothing stands still. If I were preparing the ‘Scope one now, I would draw from the newly published CinemaScope: Selected Documents from the Spyros P. Skouras Archive. Skouras was President of 20th Century-Fox, and he kept close tabs on the hardware he acquired from Chrétien in 1953. This collection of documents, edited by Ilias Chrissochoidis, shows that Skouras saw ‘Scope as a way to follow Cinerama’s path and boost the studio’s profits. “I would hate to think what would have happened to us if we had not created CINEMASCOPE. . . . Certainly we could not have continued much longer with the terrific losses we have taken on so many of our pictures.” ‘

Scope didn’t rescue the industry, or even Fox, from the postwar doldrums, but some of the behind-the-scenes tactics of the format’s first years are revealed here. For example, Skouras hoped that filmmakers would put important information on the surround channels deployed by the format, in the hope that theatre owners would make more use of them. “Such scenes would have to be unusual ones, but even with my limited imagination I can visualize many scenes in which dialogue would be heard from only the rear or the sides of the theatre.” This seems fairly extreme even today.

Jeff Smith is a swell colleague here at UW–Madison. (He and I are teaching a seminar that’s just winding down. More about that, I hope, in a later entry.) In his May guest entry for us, Jeff wrote about the new immersive sound system Atmos. But he’s been busy filling hard covers too. Research articles by him have appeared in three new books on film sound.

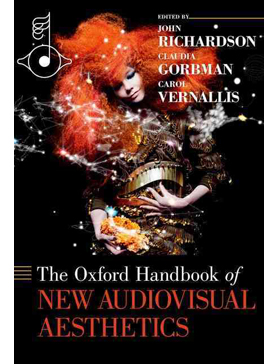

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

To Arved Ashby’s Popular Music and the New Auteur: Visionary Filmmakers after MTV Jeff contributed “O Brother, Where Chart Thou?: Pop Music and the Coen Brothers”–surely required reading in the light of Inside Llewyn Davis. He’s also a contributor to two monumental volumes that will set the course of future sound research. David Neumeyer has in The Oxford Handbook of Film Music Studies gathered a remarkable group of foundational chapters reviewing the state of the art. Jeff’s piece charts the changing relations between the film industry and the music industry, from The Jazz Singer to Napster and file-sharing. For another doorstop volume, The Oxford Handbook of New Audiovisual Aesthetics, edited by John Richardson, Claudia Gorbman, and Carol Vernallis (three more top experts), includes a powerful essay in which Jeff shows how techniques of intensified continuity editing have their counterparts in scoring, recording, and sound mixing. Not to mention his forthcoming book on an altogether different subject, Film Criticism, the Cold War, and the Blacklist: Reading the Hollywood Reds. All in all, a busy man–the kind we like.

My March essay, “Murder Culture,” devoted some time to the women writers of the 1930s and 1940s who created the domestic suspense thriller–a genre I believe has been slighted in orthodox histories of crime and mystery fiction. The piece brought friendly correspondence from Sarah Weinman, editor of a new anthology from Penguin: Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives. She has assembled a fine collection, boasting pieces by Vera Caspary, Dorothy B. Hughes, Charlotte Armstrong, Dorothy Salisbury Davis, Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, and Elisabeth Sanxay Holding (whom Raymond Chandler considered the best suspense writer in the business). These stories will whet your appetite for the excellent novels written by these still under-appreciated authors. Sarah’s wide-ranging introduction to the volume and her headnotes for each story will guide you all the way.

Finally, not quite a book but worth one: “The Watergate Theory of Screenwriting” by Larry Gross has been published in Filmmaker for Fall 2013. (It’s available online here to subscribers.) The essay is based on the keynote talk that Larry gave at the Screenwriting Research Network conference here in Madison.

Digital is so pushy

From Doddle.

Back in May, I provided an update on the progress of the digital conversion of motion-picture exhibition. Today, 90% of US and Canadian screens are digital, and over 80% worldwide are. (Thanks to David Hancock of IHS for these data.) I wish I could say the Great Big Digital Conversion was at last over and done with, but we know that we live in an age of ephemera, in which every technology is transitional. As I was finishing Pandora’s Digital Box in 2012, the chatter hovered around two costly tweaks.

The first involved higher frame rates. One rationale for going beyond the standard 24 fps was the prospect of greater brightness to compensate for the dimming resulting from 3D. Peter Jackson presented the first installment of his Hobbit film in 48 fps in some venues, and James Cameron claimed that Avatar 2 and its successor would utilize either 48 fps or 60 fps. And in January of this year some studio executives predicted that 48 fps would become standard.

Not soon, though. The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug will play in 48 fps on fewer than a thousand screens. Bryan Singer, who praised the process, has pulled back from handling the next X-Men movie at that frame rate. The problem is partly cost, with 48fps demanding more rendering and vast amounts of data storage. As far as I can tell, no one but Jackson and Cameron are planning big releases in the format.

The other innovation I mentioned in Pandora was laser projection. It too will brighten the screen, and according to its proponents it will also lower costs. Manufacturers are racing to build the machines. Christie has presented GI Joe: Retaliation in laser projection at AMC Theatres’ Burbank complex, and the firm expects to start installing the machines in early 2014. Seattle’s Cinerama Theatre is scheduled to be the first. NEC, the Japanese company, premiered its laser system at CineEurope in May. A basic NEC model designed for small screens (right) will cost about $38,000—an attractive price compared to the Xenon-lamp-driven digital projectors currently available. But the high-end NEC runs $170,000!

How to justify the costs? One Christie exec suggests branding: “Laser is a cool term that audiences immediately identify with.”

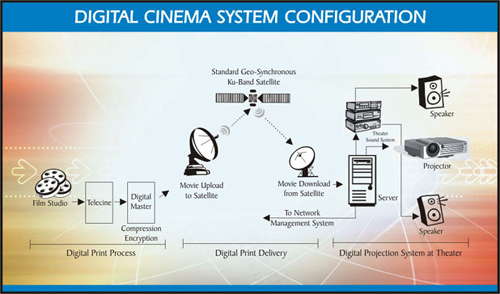

Perhaps the most important innovation since last spring’s entry involves an electronic delivery system. In October, the Digital Cinema Distribution Coalition, a consortium of the top three theatre chains along with Warners and Universal, launched a satellite and terrestrial network for delivering movie files to theatres. Theatres are equipped with satellite dishes, fiberoptic cable, and other hardware. The new practice will render the current system of shipping out hard drives obsolete, although the drives will probably continue for a time as backups. The DCDC has scheduled over thirty films to be sent out this way by the end of the year, and 17,000 screens in the Big Three’s chains are said to be hooked up. For more information, see David Hancock‘s IHS Analyst Commentary.

In the 1990s, satellite transmission was touted as the best way to send out digital films, and it was tried with Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones in 2001. Sometimes things move in spirals, not straight lines.

Speaking of the Conversion, an earlier entry pointed out the creative strategy used by the Lyric Theatre in Faulkton, South Dakota to finance its digital changeover. A gun raffle was announced on the Lyric’s Facebook page. Top prize was planned to be a set of three weapons: an AR-15 rifle, a shotgun, and a 1911 pistol.

The theatre’s screening season concluded, but the raffle is going forward, on New Year’s Eve, no less.

Television in public, movies in private

Dr. Who: Day of the Doctor (2013).

I can’t stand all this digital stuff. This is not what I signed up for. Even the fact that digital presentation is the way it is right now–I mean, it’s television in public, it’s just television in public. That’s how I feel about it. I came into this for film. —Quentin Tarantino

Spirals again. When attendance began to slump after 1947, Hollywood tried a lot of strategies–color, widescreen processes like Cinerama and ‘Scope, stereo sound, and not least “theatre television.” Prizefights, wrestling matches, and even operas were transmitted closed-circuit. Now theatre television is back, made possible by The Great Big Digital Convergence.

Godfrey Cheshire predicted some fourteen years ago that as theatres became “TV outside the home,” what we now call “alternative content” would become more common.

Pondering digital’s effects, most people base their expectations on the outgoing technology. They have a hard time grasping that, after film, the “moviegoing” experience will be completely reshaped by–and in the image of–television. To illustrate why, ponder this: if you were the executive in charge of exploiting Seinfeld’s last episode and you had the chance to beam it into thousands of theaters and charge, say, 25 dollars a seat, why in the hell would you not do that? Prior to digital theaters, you wouldn’t do it because the technology wouldn’t permit it. After digital, such transpositions will be inevitable because they’ll be enormously lucrative.

Godfrey’s prophecy has been fulfilled by all the plays, operas, and other attractions that run in multiplexes during the midweek or Sunday afternoon doldrums. His Seinfeld analogy was reactivated by last month’s screenings of Dr. Who: The Day of the Doctor in 3D. It was shown on 800 screens in seventy-five countries, from Angola to Zimbabwe, while also being broadcast on BBC TV (both flat and stereoscopic). The Beeb boasted that the per-screen average for the 23 November show beat that of The Hunger Games: Catching Fire. Globally, it took in $10 million, despite being available for free on TV and the Net. In the US, the event was coordinated by Fathom, a branch of National Cinemedia, a joint venture of the Big Three chains.

While some complained about dodgy 3D in the show, a surprisingly fannish piece in The Economist declared that “this landmark episode was buoyed up with fun, silliness, and hope.” The larger prospect is that other TV shows will take the hint and host season premieres or end-of-season cliffhangers in theatres. Many art house programmers would kill to show episodes of Game of Thrones or Mad Men, or even marathon runs of House of Cards. If it happens at all, I’d bet on Fathom getting there first.

I’ve had little to say, in this arena or in Pandora, about streaming and VOD, but these are becoming important corollaries of the Great Big Digital Convergence. Netflix in particular is expanding its reach, growing its subscriber base, creating original series, and enhancing its stock value, despite some ups and downs. At the same time, it’s pressing studios and exhibitors for the reduction in “windows,” the periods in which films are available on different platforms.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

The theatrical window was traditionally the first, followed by second-run theatrical, airline and hotel viewings, pay cable, and so on down the line. Now that households have fast web connections, streaming disrupts that tidy business model. In October Ted Sarandos, Chief Content Officer for Netflix (right, with Ricky Gervais), suggested that even big pictures should go day-and-date on Netflix.

“Why not follow with the consumer’s desire to watch things when they want, instead of spending tens of millions of dollars to advertise to people who may not live near a theater, and then make them wait for four or five months before they can even see it?” he added. “They’re probably going to forget.”

Exhibitors howled. Sarandos quickly recanted, saying only that he wanted people to rethink the current intervals between theatrical and ancillary release.

Some observers speculated that his October remarks were staking out an extreme position he intended to moderate in negotiations down the line–possibly to suggest that mid-budgeted pictures would be good ones to experiment with on day-and-date. Perhaps too Netflix was emboldened by the much-publicized remarks of Spielberg and Lucas in a panel last June, when they indicated that the future for most movies was VOD, with multiplexes furnishing more costly entertainments for the few. (In the same session, Lucas predicted that brain implants would allow people to enjoy private movies, like dreams.)

In any event, windows are already shrinking. In 2000, the average theatrical run was 170 days; now it’s about 120 days. With about 40,000 screens in the US, films play off faster than ever before. Video piracy, which makes new pictures available well before legal DVD and VOD release, puts pressure on studios to shorten windows. It seems likely that the windows and the intervals between them will shrink, perhaps allowing films to go to all video formats as quickly as 30-45 days after the theatrical release ends.

Studios have incentives to shorten the windows, if only because a single promotional campaign can be kept going long enough for both theatrical and home release. In addition, buying or renting a movie with a couple of clicks encourages impulse purchasing, and the cost feels invisible until the credit-card bill comes. Nonetheless, commitment to day-and-date home delivery would be risky for the studios.

Hollywood is more than ever before playing to the global audience. Even with the VOD boom, digital purchase and rental constitute a small portion of the world’s movie transactions. According to IHS Media and Technology Digest, theatrical ticket sales, purchase and rental of physical media (DVD, Blu-ray) add up to nearly 12 billion transactions, while Pay Per View, streaming, and downloads come to only about a billion or so. (These categories omit subscription services like cable television and basic VOD on Netflix, Hulu, Amazon, and the like.) Moreover, customers in 2012 spent about 61 billion dollars buying tickets to movies, buying DVDs, and renting DVDs. Tania Loeffler of the IHS Digest writes of North America, the most developed market for digital sales and rental:

Movie purchases made online in North America increased year-on-year by 36.6 per cent to reach 29.2m transactions. The rental of movies online also increased, to 112m transactions, an increase of 57.3 per cent over 2011. Despite this strong growth, movies purchased or rented via over-the-top (OTT) online movie services still only accounted for a combined $836m, or 3.3 per cent of total consumer spending on movies in North America.

By contrast, worldwide consumer spending on theatrical movies actually grew in 2012, to a whopping $33.4 billion–over 50 % of all movie transactions. (Thank you, Russia and China.) And despite the decline of disc purchases and rentals, Loeffler estimates that physical media will still comprise about thirty per cent of worldwide movie transactions through to 2016.

Theatrical releases continue to offer studios the best deal. Because the prices of streaming and downloaded films are low, there is less to be gained from them. True, if windows shrink, the studios will demand that Netflix and its confrères price VOD at high levels, say $25-50 for an opening-weekend rental. But consumers used to cheap movies on demand could balk at premium pricing.

At present, digital delivery of movies to the home provides solid ancillary income to the distributors, even if it doesn’t yet offset the decline in physical media. Add in Imax and 3D upcharges, and things are proceeding well for the moment. Like the rest of us, moguls pay their mortgages in dollars, not percentages or transactions. As long as some hits keep coming, we should expect that studios will maintain an exclusive multiplex run for major releases, as the most currently reliable return on investment.

Orpheum metamorphosis

The New Orpheum Theatre, 216 State Street, 1927.

Another note on exhibition relates to the last commercial picture palace in downtown Madison, Wisconsin. My July 2012 entry related the conspiratorial tale of how the grand old Orpheum Theatre on State Street fell on hard times. In fall of 2012 the building seemed slated for foreclosure, but then maybe not. Last month Gus Paras, a hero of my initial post, stepped forward and bought the old place. According to Joe Tarr in our politics and culture weekly Isthmus, there’s a lot of work to do.

Plaster is crumbling off sections of the ceiling, the result of years of water damage from a leaky roof. The walls are littered with scratches and marks, in bad need of a paint job. A plastic garbage can sits in the theater, collecting water leaking from an upstairs urinal. Paras even found dried-up vomit in two spots on the carpet.

Making matters worse, Monona State Bank, which controlled the property while it was in foreclosure, filled in the “vaults” behind the theater, which means replacing the building’s frail boilers and air conditioning will be much more complicated and expensive.

“I don’t have any idea how I’ll get the boiler in and out,” Paras says. “The stairs are not strong enough.”

Envoi

Have any of you worked on a film, say, 10 years ago, and it comes out on Blu-ray and you look at it and think, “This isn’t the film I’ve shot”?

Bruno Delbonnel (DP, Inside Llewyn Davis): Always. Always.

Barry Ackroyd (DP, Captain Phillips): I’ll be watching and it’s in the wrong format.

So what is it like to devote your lives and careers to creating images that you know exist only momentarily in their absolute best state, that may never be seen by most people the way you would like them to be seen?

Sean Bobbitt (DP, Twelve Years a Slave): At least you get a chance to see it once. All you can do is hope that people will see an approximation of that. I’ve been to screenings where I’ve had to get up and walk out because I just couldn’t bear to watch the film in the state it was in. But at the end of the screening, people say, “That was fantastic. That was beautiful. Well done!” and you’re thinking, “If only they had seen the real thing.” We would drive ourselves mad if we worried too much about it.

On shrinking windows, see Andrew Wallenstein and Ramin Setoodeh, “Exhibitors Explode over Netflix Bomb,” Variety (5 November 2013), 16. The chart on this page doesn’t appear in Variety‘s online edition of the story. Tania Loeffer’s report, “Transactional Movies: The Big Picture,” appeared in IHS Screen Digest (now IHS Media and Technology Digest) for April 2013, 123-126. Douglas Gomery discusses the theatre television plans of the 1940s-early 1950s in his Shared Pleasures: A History of Movie Presentation in the United States, pp. 231-234. My envoi comes from a revealing conversation among cinematographers at The Hollywood Reporter.

A 2012 catchup blog chronicling earlier phases of these developments is here.

P.S. 23 December 2013: David Strohmaier, the creative force behind the Cinerama restorations, has put online the stirring original trailers for Search for Paradise (low resolution and high-definition) . David attended the U of Iowa when Kristin and I did, though alas we didn’t meet him. He deserves a big thank-you for all his work in making these extraordinary films available to us.

The Grandmaster.

GRAVITY, Part 2: Thinking inside the Box

Kristin here:

In my previous entry, I described Gravity as an experimental film. I had thought of it that way ever since seeing trailers for it online back in mid-September. I described it as reminding me “of Michael Snow’s brilliant Central Region, but with narrative.”

Last time I developed that notion in more detail and analyzed the narrative structure of the film. Now I’ll analyze the experimental aspects of the film’s style and the dazzling means by which they were created. I don’t have the technical expertise to explain the inventions and ingenuity that went into creating Gravity, so I have sought to pluck out the best quotations from the many interviews and articles on the film and organize them into a coherent layout of how its most striking aspects were achieved.

As in that entry, SPOILER ALERT. This is not a review but an analysis of the film. Gravity does depend crucially upon suspense and surprise, and I would suggest not reading further without having seen the film.

Screaming on the set

I’ve written about Cuarón’s use of long takes, a stylistic device that has drawn a huge amount of attention in the press. Here the editing is so subtly done that even someone like me, who typically notices every cut, missed a lot of them during early viewings. There are bursts of rapid editing, as when the ISS is struck by debris and is destroyed, or more conventional cutting, as when the camera follows the Chinese pod and surrounding remnants of the station as they heat up in the atmosphere.

The long takes go beyond what Cuarón has done before. In Variety, Justin Chang describes one major difference: “As the movie continues, the filmmakers even add a new wrinkle, which Lubezki calls ‘elastic shots’: Takes that go from very wide shots to medium closeups, then segue seamlessly into a point-of-view shot, so the viewer is seeing the action through the character’s eyes, right down to the glare and reflections on a helmet visor.” Such moments are rare in Gravity, but one occurs in the “drifting” portion, shortly after the segment laid out above:

As Cuarón has pointed out, his long takes eliminate the need to cut in to closer views: “The language I have been working on with Chivo in these recent films is not one based on close-ups. We include close-ups as part of a longer continuous shot. So this all becomes choreography.” Another point he makes in this and other interviews is the influence of Imax documentaries on Gravity: “My process of exploring long takes fits in with that IMAX documentary notion, because when they capture nature it isn’t like they can go back and pick up the close-up afterward. There isn’t that luxury in space either. So then it falls to us to find a way to deliver that objective view, but then transform it into a more subjective experience.” Hence the “elastic shots.”

The long takes often dictate a refusal to cut in to reveal significant action. There is the moment in the epic opening shot, for example, when Shariff is suddenly killed in the background while in the foreground Kowalski tries to help Stone detach from her mechnical arm and into the shuttle. Did you see the flying piece of debris that struck his head? I didn’t, not until the fourth time I watched the film, knowing that it was coming and determined to spot it. It’s there, a little white dot that flashes through the frame in a split second. Shariff’s abrupt movement to the side, stopped with a jerk by his tether, is what we spot, since his bright white suit moves so suddenly and quickly, ending up against the pitch black of space:

A great deal happens in such moments of action, and we are left to spot what we can.

If these long takes are dazzling on the screen, think what they must have been like to witness being made. Lubezki has suggested how complicated the long takes in Gravity and earlier films were to shoot:

There are very few director/cinematographer teams working today as well known for a certain aspect of filmmaking as you and Alfonso are, which is that long extended take, or the seamlessly edited take. What it is like actually shooting those scenes?

I’m going to tell you something, the reality is that the movie was so new that when we finished a shot we would get so excited people would scream on set—probably me before anybody else. There were moments when we were shooting and Alfonso said ‘cut’ we would all just jump and scream out of happiness because we’d achieved something that we knew was very special.

In Children of Men, we also had moments like that. When we finished the first shot inside that car [the aforementioned ambush scene], the focus puller started crying. There was so much pressure that, when he realized he had done a great job, he just started crying.

There is something breathtaking about the achievement of complex long takes that seems not to arise from any other cinematic technique. I have seen Russian Ark three times now, and each time I feel an inexplicable tension, wondering whether the camera team will make it through the entire one-shot film without a mistake. I’ve already seen it happen, and yet it still seems unbelievable that they did.

In Gravity, of course, the “long takes” were not actual lengthy runs of the camera. Nor were they, as in Children of Men, several camera takes stitched together digitally to create lengthy single shots. Rather, they were created in the special-effects animation, with the faces of the actors being jigsawed into them through a complex combination of rotoscoping and geometry builds. (See this Creative Cow article for an example.)

The choice to present the action in long takes was crucial to the look of the film. Most films set in space rely heavily on editing, since for decades the special effects needed to convey space walking were best handled in a series of shots. In Star Trek Into Darkness, Kirk flies through space toward a spaceship breaking up and surrounded by debris, a situation somewhat comparable to that in Gravity. The sequence is built up of many short shots of Kirk against shots of dark space, point-of-view shots through his helmet, and cutaways to characters inside the Enterprise conversing with him via radio. Here’s a brief sample of four contiguous shots:

The sequence conveys little sense of weightlessness, partly because the actor adopts a traditional superhero-style flying pose. With no air in space, there would be no need to compact oneself into a streamlined shape. The fast cutting keeps repeating similar compositions, as with frames 2 and 4 above, with the fast editing presumably intended to generate excitement. (Star Trek Into Darkness has at least 2200 shots in a little over two hours, while Gravity has about 200 in 83 minutes.) Gravity‘s success in creating a realistic environment in space is dramatically evident when contrasted with this film’s more traditional outer-space conventions.

But it turns out that the commitment to the long take led Cuarón toward less common choices about editing, staging, and lighting.

Follow the bouncing axis

For much of the film, there is minimal spatial stability for the characters or for our viewpoint into the diegetic world. There is no ground, so we cannot imagine the camera resting on anything. When outside the space vehicles, the camera moves nearly all the time. In an interview with ICG Magazine, director Alfonso Cuarón was asked, “So with the camera and characters in constant motion and changing perspective, how did you figure up from down?” He replied:

There is no point of departure because there is no up or down; nobody is sitting in a chair to orient your eye. It took the animators three months to learn how to think this way. They have been taught to draw based on horizon and weight, and here we stripped them of both.

Undoubtedly many scenes contain an axis of action running between the characters, but it is not of a traditional kind. Unlike in a classically edited film, in Gravity‘s action scenes in space, the axis is in constant, fleeting motion, and any given center line between two characters must in quick succession run not only left and right but also up and down, diagonally, in almost any direction. Any given screen direction set up by the axis is ephemeral and offers little to help orient us spatially. Eyeline directions mean very little, since there are few cuts to things that the characters have seen offscreen. (True, when characters look offscreen, they establish eyelines, and the camera sometimes pans from Stone or Kowalski to some object they have been looking at. But a pan from a person to an object automatically establishes the spatial relations between them, whether or not the character is looking at the object.)

As a result, the spatial cues used in continuity editing system are not so much eliminated as made irrelevant for long stretches. That system is meant, after all, to guide our understanding of the story space across cuts. There are exceptions, such as a brief shot/reverse-shot exchange: Stone, loosely attached to the International Space Station (ISS) by ropes, pleads with Kowalski not to untether himself from her and float away to die in space, and he insists that it is the only way to allow her to live. When Kowalski and Stone, tethered together, travel toward the ISS, he is always at screen left, she at screen right, with the strap joining them stretched out as a sort of visible axis of action; straight cut-ins to close views of each character, and even at one point Kowalski’s point of view, obey the 180-degree rule and create an almost conventional scene. Actions inside the spacecrafts are more oriented as well. In the ISS Stone moves weightlessly through a series of pods, all the while maintaining screen direction. Similarly, inside the vehicles, especially late in the film when Stone is strapped into seats, she is usually upright, her head oriented toward the top of the frame. Some sustained actions in space also keep her right-side up, as when she removes the bolts holding the parachute cords to the Soyuz landing vehicle.

In part because of such orienting devices, we are seldom seriously confused about where the characters are, or at least not for long. Otherwise we would not be able to comprehend the story action. Still, compared to typical classical films, Gravity conveys little sense of spatial stability. The disorienting simulation of weightlessness for characters and camera dominates the scenes outside the vehicles and creates a style that can truly be called experimental.

Take the brief segment (about 14 seconds) below, from the 13-minute opening shot. Stone has been standing at the end of a large mechanical arm which gets knocked off the space shuttle by a piece of hurtling debris. It spins rapidly, with the camera framing it from long-shot distance. The camera is not entirely static, reframing slightly, but we can see the earth in the background fairly clearly. Stark sunlight comes from offscreen left, and as Stone’s body whips through space, the shadows move accordingly around her, with the back of her body in deep shadow in the first frame and then her front shadowed in the second:

The fact that the light source, the sun, is offscreen left during this spinning segment suggests that the camera and hence our viewpoint are in a stable position. Yet that position is maintained for only a short time. At this point in the shot, the camera is essentially waiting for her to draw near in order for it to execute a change that will govern the penultimate part of the lengthy shot.

That happens when, after she has spun wildly toward and away from us several times, the camera “attaches” to her, so that we are now seeing her in medium shot and spinning with her. Instead of seeing the earth clearly, we see her while the blurred surface of the earth and the blackness of space alternate rapidly. This was the technique that led me, when I first saw the film’s trailers, to compare Gravity to Michael Snow’s Central Region:

Being closer to Stone, we can see more clearly the shadows coming and going; her face is sometimes illuminated brightly by the sun and sometimes in near darkness:

The function of the attachment to Stone, apart from allowing us to see her fear and confusion, is to show us that her hands are working to detach her from the arm, as a tilt down reveals:

As she soars off the arm and tumbles into the black depths of space, the camera leaves its “attachment” to her, and she spins away from it:

Cuarón’s commitment to the long take thus made him rely more than usual on events taking place within the frame–camera movement and figure movement in particular. Yet these movements had to occur in a microgravity environment radically different from the earthbound surroundings of Children of Men and Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. This new constraint led to some technological innovations of remarkable originality.

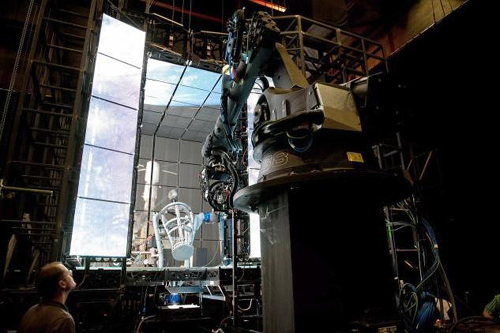

The LED Light Box

Early on it became clear that moving the actors through space on wires would not create the desired realism of weightlessness, and obviously they could not be whipped about and tumbled in ways that the film ultimately achieved. The actors would have to be relatively static, with the illusion of movement created through other means. One of the main challenges was to have the lighting on their stationery faces support that illusion. And it would have to be done perfectly in order to achieve the photorealistic depiction of space that the filmmakers were after.

Usually in watching a film heavily dependent on CGI, one notices elements that have been assembled into a single composition but don’t quite match each other. A matte painting that isn’t lit from precisely the same angle as all the other components stands out from the rest (as, it has to be admitted, happens in the best of CGI scenes, including those in The Lord of the Rings). The problem was solved for Gravity using the LED Light Box, a device frequently mentioned in the press coverage of the film but seldom explained. (See image at the top.) The concept is truly revolutionary, although I am not sure to what extent it would work for other films that did not present such peculiar challenges.

In American Cinematographer‘s article on Gravity, “Facing the Void,” cinematographer Emmanuel Lubezki explains why consistency of lighting is crucial and how he came up with his solution:

Lubezki emphasizes that Gravity‘s blending of real faces with virtual environments posed a tremendous challenge. “The biggest conundrum in trying to integrate live action with animation has always been the lighting,” he says. “The actors are often lit differently than the animation, and if the lighting is not right, the composite doesn’t work. It can look eerie and take you to a place animators call ‘the uncanny valley,’ that place where everything is very close to real, but your subconscious knows something is wrong. That takes you out of the movie. The only way to avoid the uncanny valley was to use a naturalistic light on the faces, and to find a way to match the light between the faces and surroundings as closely as possible.”

This challenge led Lubezki to imagine a unique lighting space that was ultimately dubbed the “LED Box.” He recalls, “It was like a revelation. I had the idea to build a set out of LED panels and to light the actors’ faces inside it with the previs animation.” Lubezki conducted extensive LED tests and then turned to [special effects head Tim] Webber and his team to build the 20′ cube and generate footage of the virtual environments, as seen from the actor’s viewpoint, to display inside it. While constructing the LED Box, the crew also solved problems involving LED flicker and inconsistencies.

Inside the LED Box, the CG environment played across the walls and ceiling, simulating the bounce light from Earth on the faces of Clooney or Bullock, and providing the actors with visual references as they pretended to float through space. This elegant solution enabled the real faces to be lit by the very environments into which they would be inserted, ensuring a match between the real and virtual elements in the frame.

This ingenious approach largely did away with traditional three-point lighting in the exteriors. As Lubezki explains in the AC article,

When you put a gel on a 20K or an HMI [Hydrargyrum medium-arc iodide], you’re working with one tone, one color. Because they LEDs were showing our animation, we were projecting light onto the actors’ faces that could have darkness on one side, light on another, a hot spot in the middle and different colors. It was always complex, and that was the reason to have the Box.

The crucial point here is that the lighting was being created by playing the previs animation of the earth, space, the moon, and the large reflecting objects like the space shuttle on the sides of this 20′ by 10′ box. In other words, the moving images from the nearly finished special effects were used to light the faces of the actors, and those faces were later joined to those very same special effects, in a more polished form, to create the final images.

Lubezki gives an excellent description of the Box in his interview with Bryan Abrams, a series of responses which is worth quoting at length. Note that Lubezki refers to the Box as an LED monitor–essentially a giant television screen turned inside out and surrounding the actor:

Can you touch upon some of the pieces of technology and equipment that were created to make Gravity possible?

To make this movie we used many different methodologies. For one of them, we invented this LED box that you’ve probably read about, which is basically this very large LED monitor that is folded into a cube. So all the information and images that you input into this monitor lights the actors, and you can input all of the scenes that were pre-visualized to create the movie—all the environments that we had created—and you can input them into this large cube so space itself is moving around the actors.

So it’s not Sandra Bullock spinning around like crazy, it’s your cameras.

Yes, instead of having Sandra turning in 360s and hanging from cables, what’s happening is she’s standing in the middle of this cube and the environment and the lighting is moving around her. The lighting on the movie is very complex—it’s changing all the time from day to night, all the color temperatures are changing and the contrast is changing. There were a lot of subtleties that you can capture with the box, subtleties that make the integration of the virtual cinematography and the live-action much better than ever before.

The effects of the LED projections are visible in the changes on Stone’s face in the extended example above. Here’s a brief example of changes on Kowalski’s face in the opening shot:

The harsh light in the right frame above is a real lamp. The LEDs could not produce a local, hard light intense enough to simulate the sun. The team placed “a small dolly and jib arm alongside the actors” with a lightweight spotlight. This was moved “according to the progression of the virtual sun.” Such harsh light was necessary because outside the atmosphere there is nothing to filter bright sunlight. Several moments where the actors’ faces and suits are severely overexposed reflect this technique:

The Box also contained a large video monitor, visible to the actor, which displayed the previs animation. Lubezki explains: “This was wonderful in a couple of different ways. The actor sees the environment and how objects are moving in that environment, and at the same time we can see the interaction of that light on the actor. We capture true reflections of the environment in the actor’s eyes, which makes the face sit that much better within the animation.”

Previs as environment

The fact that almost everything in the film was created digitally–including the space suits in which the actors bob and spin in the exteriors–necessitated an extraordinary amount of planning and pre-production. “Pretty much we had to finish post-production before we could even start pre-production, because of all the programming,” Cuarón says. This was one reason why there was such a long gap between Children of Men (2006) and Gravity. Four and a half years were spent in developing the new technology and preparing to shoot.

The team started with geography:

The filmmakers began their prep by charting a precise global trajectory for the characters over the story’s time-frame, so that Webber and his team could start creating the corresponding Earth imagery. Cuarón chose to begin the story with the astronauts above his native Mexico. From there, the precise orbit provided Lubezki with specific lighting and coloring cues. The cinematographer recalls, “I would say, ‘In this scene, Stone is going to be above the African desert when the sun comes out, so the Earth is going to be warm, and the bounce on her face is going to be warm light.’ We were able to use our map to keep changing the lighting.”

Next, the filmmakers defined the camera and character positions throughout the story so that animators at Framestore could create a simple previs animation of the entire movie. [“Facing the Void”]

Lubezki was completely involved in planning the digital lighting. He recalls, “I would wake up at 4 a.m., turn on my computer, I’d say good morning to my gaffer and start working on a scene. I would say, ‘Move the sun 60,000 kilometers to the north.’ That way I could put the lighting anywhere I wanted.”

The reference material for the earth imagery came in part from NASA reference footage and photos. You can get a sense of these from the NASA films posted online, although these are mostly done in fast motion, unlike the ones the filmmakers would have used. One good example is “Earth HD.” There, at 2:25 and again at 2:41, one of the most recognizable locations on earth, the Nile Valley and Delta, are visible:

A similar image of the Nile appears on earth as Kowalski and Stone slowly make their way from the space shuttle to the ISS, with him asking her about her hometown and any family she might have waiting for her. (I was also happy to see the area of the site where I work in Egypt, Tell el-Amarna, which lies about midway between the Delta at the upper left and the large bend in the river.)

This geographical plotting included some ellipses. Although commentators have suggested that the film takes place in real time, or nearly so, there are temporal gaps. Shortly after the first pass of the speeding debris field, Kowalski tells Stone to set her watch’s timer for 90 minutes, since he calculates that is when they will encounter the orbiting debris again. That happens when she exits the Soyuz vehicle to detach its parachute. She again sets her timer for 90 minutes, and the debris field shows up at the Chinese station, battering it to the point where it sinks into the atmosphere and breaks up into chunks melting from the friction of reentry. Thus a little over three hours should be passing in the 83 minutes of screen duration.

Cuarón more or less confirms this timetable when he describes the creation of the previs: “The screenplay describes a journey that takes place mostly in real time, with only a couple of time transitions. We travel around Earth three times, so in previs we planned out visuals with specific knowledge of where we’d be in orbit at any given point in the story, whether it was in sunlight or darkness.”

In the film there are very few places where we can assume a significant ellipsis occurs. After Stone enters the ISS, sheds her helmet and suit, and drifts in a fœtal position, there is a gap. It’s probably not long, since she still holds some hope of going to rescue Kowalski, but she pauses to recover after her trying experience. Later, there is a cut from her inside the landing module, not in the suit, to her emerging from the hatch fully suited up–a gap we might assume to be ten minutes or so. Most notably, the cut from the nighttime shot of the earth that includes the aurora borealis at the right to the extreme close-up of frost on the window ellides a longer stretch of time. Stone has become hoarse in the interval as she tries to send a mayday message via radio. In other cases, such as Stone and Kowalski’s slow journey toward the ISS, time seems to be somewhat compressed though not ellided.

Staging without a stage

A lack of depth cues hampered the animators charged with creating the previs. The absence of one major depth cue, aerial perspective (the tendency of layers of space in the distance to turn successively bluer and blurrier due to the filtering quality of the atmosphere), caused problems. Visual-effects supervisor Tim Webber, of the effects house Framestore, remarks:

You can’t rely on aerial perspective because without atmosphere there is no attenuation of image due to distance. And the lack of reference points [in space] can get you into trouble, like not being able to tell if the character is coming toward you or the camera is moving toward him. Even though we played it straight with respect to science and realism, we did put in more stars than you’d be able to see in daylight, just so there’d be some frame of reference to gauge movement.

Presumably Webber is referring here to the movement of the characters and objects through space, not the camera movement. (The lack of any “frame of reference” against which to sense movement is part of what makes the Star Trek scene illustrated above seem so unsophisticated.)

Naturally, since the actors were not standing on a floor or solid ground, the blocking was difficult, but it also had to be planned completely in advance:

Cuarón laughs as he recalls the surprises inherent in blocking characters in a zero-gravity environment. “The complications are really something because you have characters that are spinning. Say you want o start your shot with George’s face and move the camera to Sandra, who is spinning at a different rate. You start moving around her, and then you start to go back to George, only to realize that if you go back to George at that moment, you will be shooting his feet! So then you have to start from scratch. Sometimes you find amazing things accidentally, but sometimes you have to reconceive the whole scene.” [“Facing the Void”]

Finally, after all the planning, the previs animations were made. These had to be refined considerably so that they could adequately serve in the Light Box to illuminate the actors’ faces. According to Bill Desowitz, “The previs was so good, in fact, that the daughter of cinematographer Emmanuel (“Chivo”) Lubezki thought it was the real movie.”

The previs became so sophisticated because it evolved during preproduction. Cuarón recalled that Lubezki’s inspiration to create the LED Light Box changed the planning tactics:

Then that kind of had a ripple effect back into the previz, because originally they were going to just be a model that we could look back at, but we realized that the previz was more than that. That was something that [James] Cameron kept on talking about. He would say “I don’t use previz anymore, I use it as if it is the first painting on a canvas.” In other words it was the stuff that you kept on painting on top of and the thing with that is that it became very clear that in order to use these technologies, we needed to program stuff and the previz was going to have to be precise in terms of camera movements, choreography, timing and light.

As a result, the movie changed very little during principal photography. Senior visual-effects producer Charles Howell told American Cinematographer: “I think there were only about 200 cuts in the previs animation, [whereas] an average film has about 2,000 cuts. Because these shots had to be mapped out from day one, many of the lengthy shots didn’t really change in the three years of shot production. Because we did a virtual prelight of the entire film with, the whole film was essentially locked before we even started shooting.” [“Facing the Void”]

David counted 206 shots in Gravity, not including the two opening titles about life in space being impossible. This suggests that Howell is right, and that the film underwent little revision after the planning phase.

Several years ago I suggested on this blog that animated films, notably those of Pixar and Aardman, were on average better than mainstream live-action films because they had to be planned so carefully and thoughtfully. Gravity, being very close to an animated film, provides more evidence for that claim. Not that thought, time, and money can guarantee quality, but they certainly narrow the odds.

Iris in

The Light Box technology is astonishing enough, but within its confined space there also had to be a way to photograph the actors. In Lubezki’s interview with Bryan Abrams, he explains: