Homunculus and his friends

Tuesday | July 28, 2015 open printable version

open printable version

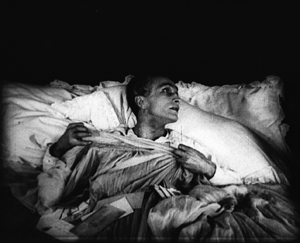

Sappho (1921).

DB here:

Of the big-ass explosion movies, only two items in this summer’s spate of them have intrigued me. I liked Mad Max: Fury Road well enough, but not as much as MM2 and 3. I look forward to Mission: Impossible—Rogue Nation, in a series for which I have much affection. As for the arthouse releases, the ones I’ve already seen are A Pigeon Sat… (good but not as sardonically bizarre as earlier Andersson, methinks) and About Elly. That one is a masterpiece.

I have stronger reasons than indifference for missing so much, and for tardy blogging besides. I’ve been on my annual trip to Belgium for research and lecturing in the Summer Film College. As a result, your recent movie experiences and mine have been divergent, perhaps even insurgent.

Apart from two screenings in the Brussels Cinematek’s Hou series (their restoration of Green, Green Grass of Home, gorgeous vintage print of City of Sadness), I spent the last four weeks watching 35mm prints of movies by Godard, movies starring Burt Lancaster, and assorted silent films from the 1910s and 1920s. I also re-met one of the most charming directors I know of, and in general had a hell of a time.

Today’s entry focuses on my archive work. Next up, a report on the Summer Film College.

Conrad’s many moods, mostly unhappy

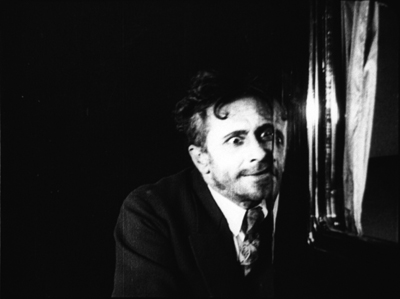

Landstrasse und Grosstadt.

The archive stuff was recherché. I’ve been trying to see as many 1910s and early 1920s features as I could, but this time around I didn’t catch anything as mind-bending as Jasset’s Au pays de ténébres (1911) or Doktor Satansohn (1916) or Fabiola (1919) or I.N.R.I (1920), encountered on earlier visits to the Cinematek. I did get further confirmation that in Germany the “tableau style” exploited so vigorously in Europe and somewhat in America in the 1910s, was pretty much replaced by Hollywood-style editing by 1920. And I got some welcome doses of Conrad Veidt, another favorite in this vicinity.

In Die Liebschaften des Hektor Dalmore (“The Liaisons of Hektor Dalmore,” 1921), Veidt plays a callous playboy who keeps on retainer a man who looks very much like him. It’s a lifestyle choice. When a compromised woman’s father demands that Hektor do the right thing, he sends out his double to marry her. Surprisingly, the double isn’t rendered through trick photography. Richard Oswald, always a fast man with a gimmick, found a pretty good Veidt lookalike, which can’t be easy to do.

The hero’s Casanova complex carries him from dalliance to dalliance, and as you’d expect in a twins situation, there are confusions between the real and the fake Hektor. Fights and abductions liven things up. The climax is a duel in which the real Hektor, overconfident, learns to his grief that an outraged husband is a better marksman. The scene is handled through brisk shot and reverse-shot, garnished with an over-the-shoulder shot as Hektor aims his pistol. And there are dashes of mildly Expressionist set design (furnished by Hans Dreier). Veidt in a phone booth does the décor proud. But he doesn’t need fancy sets to project a feeling: on his deathbed, his expression and his clutching fingers show a man bereft of erotic illusions.

The other Veidt vehicle lacked doubles but not ambition. Landstrasse und Grosstadt (“Village and City,” 1921) casts him as Raphael, a wandering violinist who teams up with Migal, an organ grinder. They become a popular act in the big city, and as Raphael’s playing improves, Migal becomes his manager. Nadia, a woman who joins them, falls for Raphael and shares his success. But in an accident he suffers a hand wound and his career slumps. Migal sees his chance to move in on Nadia. Perhaps this shot gives you a hint of his designs.

Actually, most of Landstrasse and Grosstadt isn’t as hammy as this. A very nice shot shows Raphael in silhouette approaching a mansion to hear his rival Cerlutti give a salon concert. And of course Conrad gives the blind violinist a delicate, spectral pathos, as shown above.

Artificial man lurks in the shadows, destroys humanity

Sappho.

All the films I saw broke down scenes into many close shots, reminding us that Caligari (released 1920) probably wasn’t typical of German staging or cutting of that moment. It now seems to me almost consciously anachronistic, rejecting the reverse angles and precise scene breakdown that were becoming common. In Die Ehe der Fürstin Demidoff (“The Marriage of Fürstin Demidoff,” 1921), when a governess drags a recalcitrant girl back to her bedroom, the action is split up into four shots, all of different scales from close-up to long-shot.

Although I saw a fragmentary print of Sappho (1921), it’s clear that in parts it has the audacious monumentality of a Joe May production. The most staggering shot is that of the Opera surmounting today’s entry, but there’s no shortage of striking images. Above I include a shot of a madman that, thanks to window reflections, suggests his split-up psyche.

Sappho also doesn’t shirk editing effects either. During a frantic automobile ride, there are glimpses of hands on a steering wheel, a foot on brakes, panicked passengers, and POV shots through the windshield. Forty-nine shots rush by in a flurry, anticipating similar sequences in French Impressionist films like L’Inhumaine (1924). Feuillade was experimenting with rapid cutting of action at about the same time.

The most impressive, and nutty, film in this batch came from Homunculus, the largely lost German serial released through 1916 and into early 1917. The script was written by one of the blog’s favorite peculiar directors, Robert Reinert. The plot involves an artifical man created in the lab, à la Frankenstein’s monster. He’s a superman, in both strength and ambitions. The only surviving episode of the serial is Die Rache des Homunculus (“The Revenge of Homunculus,” 1916). (But see the codicil.) In this installment, posing as Professor Ortmann, Homunculus decides to drive humanity to destroy itself. He assumes a disguise to rouse the rabble, even inducing them to turn against himself in his Ortmann guise.

As in Expressionist drama, this overachiever is pitted against a crowd that, in the end, pursues him maniacally.

Director Otto Rippert gives us splendid mass effects in a quarry and along a beach, but there are also deep tableau images and sustained chiaroscuro, particularly in a showing the heroine Margot shrinking from Homunculus as he locks his rival in a dungeon.

Fans of Metropolis will notice that Rippert anticipates Lang’s unison choreography of crowds, as well suggesting that mob frenzy can create a sort of ecstasy in the woman who’s swept along.

In her book The Haunted Screen Lotte Eisner traces the films’ mass spectacle back to the stage work of Max Reinhardt and other theatre directors of the era. On the basis of this episode alone, Homunculus ranks with Algol and May’s Herrin der Welt as an example of big-scale fantasy in German silent cinema. Who needs Ant-Man when we have Homunculus?

Next time: Burt and Jean-Luc, together again for almost the first time.

Thanks to Nicola Mazzanti, Francis Malfliet, Bruno Mestdagh, and Vico de Vocht for their assistance during my visit to the Cinematek.

Kristin analyzes stylistic conventions of German cinema of this period in her Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood (available for download here). She’s written on Caligari here and here.

A so-so copy of Sappho is on YouTube.

On Homunculus, Leonardo Querisima offers a wide-ranging discussion in “Homunculus: A Project for a Modern Cinema,” in A Second Life: German Cinema’s First Decades, ed. Thomas Elsaesser and Michael Weidel, pp. 160-167. Substantial excerpts can be found here.

Munich archivist Stefan Drössler has recovered a mass of Homunculus footage and has assembled a version of the serial, which premiered last year in Bonn. Nitrateville has the story.

The Brussels Cinematek will release its Hou restorations on DVD early next year: Cute Girl, The Boys from Fengkui, and Green, Green Grass of Home. As a reminder, my video lecture on Hou is here.

The still below, taken as the prints were readied for the Summer Film College, points ahead to our next entry–number 701, as it turns out.