Archive for August 2021

Is there a blog in this class? 2021

Kristin here:

The year since I posted our previous “Is there a blog in this class?” entry has been a strange one for filmmaking, film-going, film reviewing, film journalism, and film teaching. We managed to keep on blogging about film, though some of our usual sources of inspiration for subject matter were far less active. Fewer films to see, of course. But also less for the trade papers like Variety and The Hollywood Reporter to publish about.

Journalists have to keep filling those column inches, so many turned to speculating about the impact of the pandemic on the cinema, discussing measures productions were using to resume filming, and profiling a lot of actors. With filmmaking on hold for a long time, there was less coverage of actual industry events–the kind of reportage that sometimes goaded us to write a retort to claims made by a writer. Streaming, both from commercial services and festivals, provided fewer new releases and restorations than we would usually see. (From five in-person film festivals in 2019, we dropped to zero in 2020 and are still looking forward to having a safe way to attend one in the future.)

Nevertheless, we managed to write fairly regularly, and some of the entries might be of use to teachers as sources of information for their lectures or as readings they might assign to their students.

As always, the entries listed here might also be of use to readers who have not visited the blog on a regular basis. The earlier entries in this series can be found here: 2007, 2008, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, and 2020.

Chapter 1 Film Art and Filmmaking

In “Five critics, one of them a killer,” David examines four books on individual films by critics. The fifth, But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct, is by Ken Kwapis, TV and film director (The Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants); he considers it one of “the most acute personal reflections on Hollywood directing.”

Chapter 3 Narrative Form

Aaron Sorkin is widely admired as a skillful scriptwriter and director. On the occasion of the release of his third directorial effort, David surveys his major films and discusses how they draw upon and play with the conventions of Hollywood narrative in “THE TRIAL OF THE CHICAGO 7: Aaron Sorkin samples the menu.”

Narration is a key part of narrative. Filmmakers can create their own intrinsic norms of point-of-view and lead the spectator to notice them. David analyzes such norms in Robert Bresson’s A Man Escaped, Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (above), and Curtis Hanson’s The Hand that Rocks the Cradle in “Learning to watch a film, while watching a film.”

David examines the differences between Quentin Tarantino’s novelization, entitled Once upon a Time in Hollywood, of his film Once upon a Time . . . in Hollywood. He suggests various functions played by the considerable changes in the presentation of the central story: “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, again: Tarantino revises his fairy tale.”

Chapter 5 The Shot: Cinematography

Guest blogger Barbara Flueckiger contributed an epic entry on her and her research team’s work on the history of color technology, culminating in the creation of a website offering a vast collection of images taken from archival prints. For a generous selection of these gorgeous images and a link to the site, see her “Historical film colors: A guest entry by Barbara Flueckiger.”

Chapter 7 Sound in the Cinema

Our Film Art and Film History collaborator Jeff Smith continued his tradition of doing brief analyses of the Oscar-nominated songs in “Oscar’s Siren Song (A Slight Return): Best Original Song” and scores in “Oscar’s Siren Song (A Slight Return): Best Original Score.” His predictions of the winners went one for two, but the analyses are the real point of these entries.

Chapter 9 Film Genres

Anyone teaching a unit on the western is likely to consider showing at least one by a master of the genre, John Ford. Most of his early features in the 1910s were westerns, but only two survive more-or-less complete. The release of Hell Bent (1918) and particularly Straight Shooting (1917) on Blu-ray finally makes good prints of these two major films available. Hell Bent is more a film of great sequences and shots, while Straight Shooting has a tight story and great style throughout. I discuss them both in “When John was Jack: Ford’s early westerns rescued.”

David is a big Stephen Sondheim fan, ans he blogged about how the composer-lyricist-playwright adapted various genres into musicals, for both stage and screen in “Merrily he rolls along: A belated birthday tribute to Stephen Sondheim.”

Chapter 10 Documentary, Experimental, and Animated Films

Oskar Fischinger’s short abstract animated films straddle the categories of animation and experimental cinema. Almost all of them are set to musical pieces, both classical and popular. If you want to convince your students that experimental films can be accessible and entertaining, include a few Fischingers in your program. His work is still too little known, having become less available with the decline of 16mm rental prints. (We, like other fans, still cling to the marvelous video disc that was released back in the 1990s.)

Now most of the surviving films are available on two DVD collections, which I describe in “German classics for the pandemic and beyond.” If you show only one, it probably should be the gorgeous Motion Painting No. 1 (bottom), though I recommend throwing in Study No. 7, an irresistibly lively tango which would only add a few minutes to your program.

One abstract film we saw during the Vancouver International Film Festival is Jóhann Jóhannsson’s Last and First Men, but in this case the abstraction is created with black-and-white cinematography of real objects. “The filmmaker builds a film out of patterns of sensuous visual qualities,” as David writes in his analysis of the film in “Vancouver: First sightings.

“The “documentary” label has come to include “mockumentary” as well. Sacha Baron Cohen’s Borat Subsequent Moviefilm: Delivery of Prodigious Bribe to American Regime for Make Benefit Once Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan is a unconventional amalgam of staged fictional mockumentary scenes and candid conversations involving real people who participate in improvised scenes on the assumption that Borat is a real person and they are in a real documentary. In “Keep it stupid, simple,” David explores how Cohen’s film fits into the satirical tradition of the grotesque.

Chapter 12 Historical Changes in Film Art: Conventions and Choices, Tradition and Trends

The entry “”When John was Jack: Ford’s early westerns rescued” mentioned in the Chapter 9 section could also be useful for the “Development of the Classical Hollywood Cinema (1908-1927)” section of the film history chapter. Straight Shooting (above) is an excellent example of a classical film from 1917, the year when the conventions of the continuity style fully gelled.

“German classics for the pandemic and beyond,” mention in the Chapter 10 section, also contains my discussion of the Blu-ray of the restored Waxworks (1924), Paul Leni’s contribution to the German Expressionist movement.

At the end of each year, I post our only ten-best list–ten great films from ninety years ago. Last December it was 1930’s turn, with “The ten best films of … 1930.” I usually try to mix well-known classics with a few less known but worthwhile films. For 1930 there’s a range from The Blue Angel and Earth to Ozu’s That Night’s Wife and Duvivier’s Au Bonheur des Dames.

One of David’s main areas of interest has been Hong Kong cinema. Last year a Chinese long-form translation of his Planet Hong Kong: Popular Cinema and the Art of Entertainment was published. He took the occasion to update his account for the blog in “PLANET HONG KONG comes to … Hong Kong.”

We wish teachers and students well in what promises to be another difficult year of pandemic-era education!

Motion Painting No. 1

Dietrich before von Sternberg and von Sternberg before Dietrich

Thunderbolt (1929)

Kristin here–

In my entry on the ten best films of 1929, I suggested that that particular year, hovering as it did between silents and talkies, was relatively poorly represented on home video. Now Kino Lorber has released two films from that year that both entertain us and contribute to our knowledge of the late 1920s cinema.

In that entry I lamented the fact that Josef von Sternberg’s marvelous early talkie Thunderbolt had not had a proper DVD or Blu-ray released. I expressed hope that one of the home-video companies specializing in historically important classics would finally make it available. The Kino Lorber release finally allows historians and cinephiles access to this little-known masterpiece.

If Thunderbolt was a legendary film that called out for such a release, the 2012 Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung restoration of Kurt Bernhardt’s The Woman One Longs for reveals this previously forgotten film to be, if not a masterpiece, a very good film. It’s also completely typical of a trend of the late 1920s that I have termed the International Style.

Coincidentally, von Sternberg and Dietrich, so closely connected in our minds, link the two releases. Thunderbolt was the director’s last film before beginning his series with Dietrich, and The Woman One Longs for was Dietrich’s last (and first) starring roll before she worked with von Sternberg for the first time.

I’ll deal with it first, since I don’t want it to be overshadowed by Thunderbolt.

The Woman One Longs for

The standard story has Marlene Dietrich claiming that The Blue Angel was her first film. Seemingly she wanted to suggest that von Sternberg’s use of her in a series of star vehicles created her career. The image above, of her staring through a frosty train window, might easily be mistaken for a von Sternberg shot. In fact it’s from her previous film, The Woman One Longs for (Die Frau, das der man sich sehnt, aka The Three Lovers), directed by Bernhardt.

The Jewish director barely made his escape from the Nazis, working during the 1930s in France and then shifting to Hollywood. There, under the name Curtis Bernhardt, he made many films up to the 1960s, perhaps most notably the Joan Crawford psychological drama Possessed (1947) and the Rita Hayworth vehicle Miss Sadie Thompson (1953). That was an adaptation of Somerset Maugham’s “Miss Thompson” (previously filmed by Raoul Walsh as Sadie Thompson, starring Gloria Swanson, in 1927 and by Lewis Milestone as Rain [a new title that had replaced the original name of the short story], starring Joan Crawford).

The plot of The Woman One Longs for is straightforward melodrama. The protagonist, Leblanc, is expected to rescue his family’s factory, tottering on the brink of bankruptcy, by marrying a wealthy heiress who loves him but who leaves him cold. He marries her, but on their honeymoon trip aboard a train to the south of France, he suddenly becomes fascinated by a mysterious beauty, played by Dietrich. She seemed to be under the sadistic control of Dr. Karoff. The latter is played by the great actor of the Expressionist theater, Fritz Kortner, familiar to most modern spectators as Dr. Schön, who keeps Lulu as his mistress in Pandora’s Box (also 1929). Leblanc becomes obsessed with saving Dietrich from her captor.

The plot is entertaining enough, but the real interest in the film, at least for David and me, is Bernhardt’s direction. It’s quite skillful, even flashy. Moreover, Bernhardt had clearly been seeing many of the major films of the 1920s from Germany, the USSR, and France. Like many other directors of the late 1920s, he blends them seamlessly into what I have called the “International Style.” (See Chapter 8 of Film History: An Introduction.)

The film starts in a setting done in a style familiar from many German films of the era, with a camera following a character through an atmospheric, faintly Expressionist street clearly built in a studio (below left). Even after the Expressionist movement ended in early 1927 with Metropolis, German films continued to use settings influenced by the style to represent old buildings or poor neighborhoods. Compare the opening shot of The Blue Angel (below right), the only Expressionistic setting in the whole film.

But Bernhardt has seen Soviet films as well. The early montage establishing the Leblance family’s factory uses the quick cutting, dramatic angles, and dissolves that such scenes have in so many Soviet and European films of the era (below left). A fight scene between Leblanc and Karoff uses fast editing, canted compositions, and camera reframing (below right).

Bernhardt has almost certainly seen L’Herbier’s L’Argent of 1928, with its streamlined sets (left) and low-angle framings shot with wide-angle lenses (right). Compare the latter with the low-camera-height shot of the Paris Bourse at the top of the L’Argent section in the 1928 entry linked immediately above.)

Bernhardt had also clearly seen Underworld, for the New Year’s party that forms the climactic scene of his film imitates von Sternberg’s party scene fairly obviously. The action centers around the two main male characters’ struggle over the heroine, with two count-downs raising the suspense: the beauty contest in Underworld and the approaching midnight signalling the new year in The Woman One Longs for. The hanging streamers that increasingly dominate the setting are, however, the giveaway for von Sternberg’s influence on Bernhardt (see bottom).

Speaking of influence, there is a moment in the party scene when the drunken Kaross pops a startled child’s balloon with a cigarette. Maybe this is a common trope in films, but the only other example I can think of is Bruno’s similar gesture of casual cruelty in Strangers on a Train.

The Woman One Longs for also contains a reference that we might today call an “Easter egg.” At the end, Karoff is arrested in the luxury hotel where the three main characters have been staying and where the New Year’s party take place. The manager insists that in order to avoid a scandal, the police must escort him out of the building via the “Hintertreppe” (backstairs). One of Kortner’s major roles had been the devious, obsessed postman in Leopold Jessner’s Hintertreppe (1921), one of the few other classics by which Kortner is known today.

Thunderbolt

I have already sung the praises of von Sternberg’s pre-Dietrich films on this blog. I find his naturalistic first feature, The Salvation Hunters (1925) heavy-handed, but with Underworld (1927) he abruptly hit his stride. To me it and The Docks of New York (1928) are his masterworks–those and Shanghai Express (1932), arguably the best of his Hollywood Dietrich films. The Last Command (1928) is excellent but not up to that level. I discussed these three when The Criterion Collection released them as a set in 2010. That set went out of print but is fortunately now available in Blu-ray. I put Underworld in my ten-best list for 1927 and The Docks of New York in the 1928 list. As I mentioned at the outset, Thunderbolt made the 1929 list.

There I briefly discussed the remarkable compositions and use of offscreen sound in the lengthy prison scenes of the title character on Death Row. Watching the new Blu-ray in preparing this entry, I was struck even more by the early scene in the Black Cat, a Black-run nightclub where we are introduced to Thunderbolt and his relationship to Ritzie, the heroine. As in the silents, von Sternberg’s habit of staging compositions with obstructing objects in the foreground is apparent. Note the entrance of Thunderbolt and Ritzie with a set element both framing and obstructing them (see top). Later a scene as two patrons of the club gossip about Thunderbolt partially blocks the faces, particularly of the one on the left.

The whole scene is marvelously enhanced, as I said in my 1929 entry, by the inclusion of Theresa Harris’ complete rendition of “Daddy, Won’t You Please Come Home.” It’s hard to think of another mainstream Hollywood film in which a Black cultural situation is used so naturally and with so much respect.

The Black Cat sequence ends with a police raid on the club. The cinematography at this point is pure film noir. (See image at the top of this section.)

As I said in the earlier entry, the one flaw in the film is the tepid central couple played by Richard Arlen and Fay Wray. Given the excellence of the Black Cat sequence and the lengthy prison scenes, that flaw is minor indeed.

The Woman One Longs for (1929)

Little things

Equinox Flower (Ozu, 1958).

DB here:

Academic critics and fans share a passion for looking closely at the movies we admire. A lot of film critics enjoy spiraling out from the film to ponder Big Ideas, which is okay, I guess. But I confess I particularly enjoy digging in for trouvailles (great word), lucky discoveries that passed me by on earlier encounters.

Across my career, many of the directors I admire seem to have tucked in little things just for me (or you). They don’t necessarily carry meanings; they’re quietly decorative, subtly off-center to the narrative. Tati slipped peculiar items into the corners of the frame. Sturges offered gags that only people with his sense of humor will find funny. A successful crowdsourcing enterprise exposed Welles’ homages to early film. Above all, Ozu nudged me toward red teakettles and surprising details. Who else lines up the levels of beverages in a table setting, and then matches that plane to the edge of a fruit bowl?

If you care enough about my movie, the director seems to say, I’ll reward you with a trouvaille. Here are two I found recently.

Showing the stitches

Sometimes a trouvaille is a felicity of craft. The director quietly shows off his virtuosity to those in the know. While studying Pulp Fiction for a book I’m finishing, I noticed that Tarantino sets up the ending in a sidelong way.

You’ll remember that the opening shows Honey Bunny and Pumpkin discussing how a restaurant is one of the safest robbery targets. Abruptly they launch an assault on the diner. Then they drop out of the film for a couple of hours.

Very likely we’ve forgotten about them when Jules and Vincent settle down for breakfast in a diner. After discussing the virtues of pork products and the prospects for Jules’ future, Vincent rises to go to the toilet. As he pauses, it’s possible, but not easy, to discern the larcenous couple out of focus in their booth behind him. Given their peripheral status and the centrality of Travolta’s performance, I suspect that almost no one notices them on a first viewing.

Soon after Vincent has left, we’ll hear a repetition of the final bits of the couple’s conversation and we’ll see a replay of their leaping up to announce the robbery. Tarantino has rewarded the sharp-eyed viewer with a slight anticipation of the replay, and a hint at how his film will fold back on its opening sequence.

But this echo is matched by a “pre-echo” during the opening sequence. As Pumpkin and Honey Bunny plan their heist, a close view of her includes a bulky man in a t-shirt walking into the distance.

At this point, a first-time viewer hasn’t been introduced to Vincent, so the t-shirt guy is just part of the scenery. Only in retrospect do we realize that here Tarantino is anticipating, and overlapping, the portion of the robbery that we’ll see in the final moments of the film.

Here the critic/fan is invited to appreciate how carefully made the film is. It’s a quality we don’t sufficiently recognize in Tarantino: a delight in fine-grained formal niceties.

Easter Egg, avant la lettre

In Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1950), tennis pro Guy Haines is introduced (implausibly) reading a book on his trip. Soon he’s accosted by the spoiled, marginally nuts Bruno Anthony, and the plot gets under way. Only a fan, or a critic, will want to know: What’s Guy reading?

It’s not easy to tell. We don’t get a close-up of the book. The best we can tell, from above, is that it’s a hardcover, with a photo on the back of the dust jacket. Later, after Guy and Bruno have shared a meal in a compartment, we can glimpse the spine.

Blown up, thanks to the glory of Blu-ray, the spine looks like this.

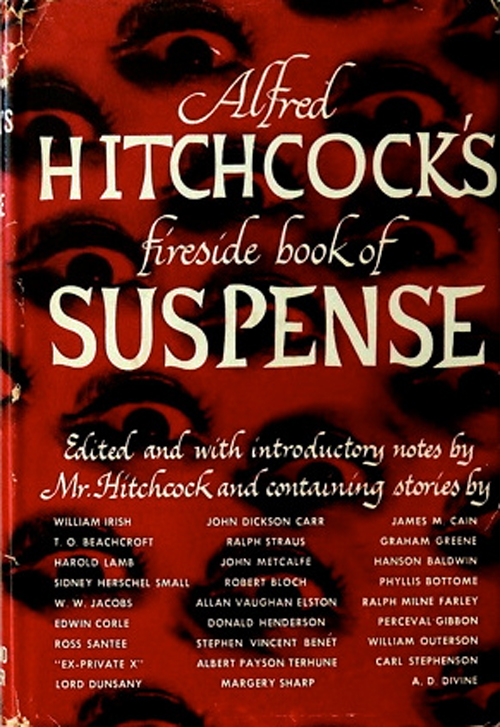

A little research reveals that the volume is Hitchcock’s collection of stories published in 1947 by Simon and Schuster.

Several anthologies were published under Hitchcock’s name from the 1940s onward, but most were in paperback. This was a more prestigious item, and I suspect it helped the branding effort that was underway during his Hollywood career. The picture on the back is of Hitchcock, of course. (My copy lacks a dust jacket, so I can’t supply that.) But the resonance comes from the fact that I was reading this very book as part of preparation for my own study of 1940s mystery culture.

It’s not exactly product placement; the book’s presence is too fleeting to register with audiences, surely. Including the book seems more in the nature of a private joke among Hitch and his team. Guy is a man of good taste, reading a book by the man directing the film he’s in.

Today we’re familiar with Easter Eggs, those bonus materials that establish a complicity between filmmmaker and viewer. Is this an early example? It could be a prize for fan connoisseurship. The book isn’t emphasized, being buried in the mise-en-scene, and so it encourages the devout to poke and probe. It also points outside the film to the production context. Still, how many 1950 viewers, lacking our ability to freeze and magnify the frame, could have spotted it? Perhaps only the devotion of a modern fan, aided by new technology, can bring this trouvaille to light. An incipient Easter Egg, then, awaiting digital technology to be discovered?

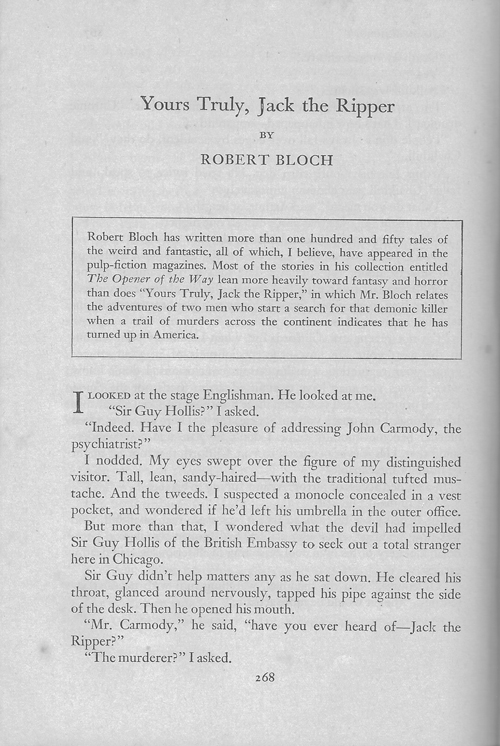

Once we’re down this rabbit hole, let’s scramble further. What stories might Guy be reading? There are two hints. We have the placement of the jacket flap in the shot above, and an earlier shot showing the book open.

As best I can tell, the story Guy’s reading is likely to be “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.” It tells of a psychiatrist who meets an Englishman called “Guy Hollis.” Sir Guy believes that Jack the Ripper has migrated to the US and is at large in Chicago. With the aid of the psychiatrist, Sir Guy finds him. Apart from the name Guy, the correspondence to Strangers it would seem to involve a peculiar bond between two men, one of whom is a psychopathic killer.

But there’s another, stranger affinity.

The author of “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” is Robert Bloch., whose novel Psycho would furnish Sir Alfred his 1960 film. Coincidence? In the land of trouvailles, are there any coincidences?

Fans have raked over these movies assiduously, so I can’t imagine I’m the first to notice these fine touches. No matter. When you discover them on your own, you still feel a tiny thrill of communicating with the filmmaker, behind the backs of all those folks who didn’t notice. Ozu, I often feel, is making movies especially addressed to me. It’s an illusion, of course, but I refuse to give it up.

Thanks to the University of Wisconsin–Madison Filmies listserv for helping me understand what counts as Easter Eggs, and for a reality check on my sanity.

This site includes lots more on Hitchcock, Ozu, Sturges, and Tarantino. My book on Ozu is available from the University of Michigan. It takes time to download, so be patient.

P.S. 15 August 2021: As I thought, I’m not the first. A mere twenty-one years ago, Dana Polan in his monograph on Pulp Fiction (British Film Institute) noticed the pre-echo of Vincent headed toward the toilet. Good going, Dana! Film analysis wins again.

Days of Youth (Ozu, 1929).

French silents from Il Cinema Ritrovato 2021

L’Arlésienne (1922)

Kristin here:

Like so many of our fellow festival-goers, David and I were not able to visit Bologna for Il Cinema Ritrovato, the annual festival of restored films and curated thematic threads. Fortunately the organizers made a selection of the films and events (interviews, discussions of films by archivists) available online.

We were not able to watch all of these, so we concentrated on an area in which we have both worked, French silent cinema. There were three of these, or six if you count the four episodes of the 1927 serial, Belphégor. They were beautiful restorations, all presented in black and white. (I must admit, beautiful though tinted and/or toned films are, I prefer the black-and-white versions. That’s mainly because if one is taking frame enlargements for reproduction in black and white in a publication, it is often impossible to get a decent copy from a tinted print.)

No doubt it is frustrating to read about films that are unavailable to see outside archives. Still, some of the Cinema Ritrovato films travel after their presentations at the festival, and some appear on DVD/Blu-ray. These are three to keep an eye open for.

L’Arlésienne

I must admit, this was the only title of the three that I recognized. David and I had been very impressed by André Antoine’s earlier films. (See our brief comments on and some frames from his extraordinary 1917 Le coupable here and here.)

While Le coupable was a courtroom melodrama set in Paris, L’Arlésienne follows his 1921 naturalistic film La terre by being shot in the French countryside. In this case the story takes place in and around Arles, at that time a village in the south of France, not far from the Mediterranean coast northwest of Marseilles. The familiar tale concerns the family of Rose Mamaï, a widow who runs her large farm, aided by her cheerful, naïve son Frédéri, who seems destined to marry Vivette, from a nearby farm, until he falls under the spell of the unnamed title character.

The film is not as splendid as the two earlier ones, but it is well worth seeing nonetheless. It gets off to a somewhat slow start, with a leisurely exposition of the locales and the characters. Frédéri’s growing obsession with l’Arlésienne takes its time. Still, conflict eventually creates greater drama as Rose learns of her son’s love for a woman “with a past” and the woman’s lover shows up to try and thwart her golddigging attempt to marry Frédéri.

The gorgeous cinematography and use of authentic locations, however, more than offset the plot problems (see frames above and at top). Like so many French directors of the silent era, Antoine took advantage of local carnivals and holidays, economizing by filming the crowds candidly. The frequent glances into the camera by locals testify to that.

To the far left of this frame, one can glimpse the well-known Roman amphitheatre of the town, used in L’Arlésienne for a bullfight scene, whither the villagers in their best clothes are headed.

Antoine’s film makes an interesting comparison with Alberto Capellani’s 1908 version, shown in the first Cinema Ritrovato season of his films. Capellani shot most of his excellent version in Arles as well, though in a very different style. (I discuss it briefly here and here; the latter entry gives information on the DVD releases of various Capellani films shown at the festival, including L’Arlésienne.)

Figaro (1927)

Gaston Ravel is a director whom many of us have heard of, but few of us have seen his films. His reputation is as a director of high-budget, prestigious films–comparable to Raymond Bernard, whose The Miracle of the Wolves (1924) is perhaps the most familiar of the epic period films of the period, excepting Napoléon vue par Abel Gance (1927).

With Figaro, Ravel manages to condense all three of Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais’s three Figaro plays (Le Barbier de Séville [1775], Le Mariage de Figaro [1781 but banned from performance until 1784], and La Mère coupable [1792]) into a two-hour film.

The result is a lavish spectacle. The costumes were designed by J. K. Benda, who later created those of La Kermesse héroïque (Jacques Feyder, 1935). The interior sets were studio-built (see bottom), though the exteriors of the later parts of the film were shot at a huge chateau with extensive grounds, the Rochefort-en-Yvelines. At least some French directors had by this point adopted and mastered Hollywood three-point lighting, as the frame above demonstrates.

Visually the film in fact looks like it could have been made in one of the big Hollywood studios, though the story is a bit too risqué to have been made there. (The young lady dancing and trailing a long, diaphanous veil in the frame at the bottom eventually spins until it drops off, leaving her completely nude.)

I found the casting of “artistic dancer” Edmond van Duren (as the program notes describe him) unfortunate. He reminded me of the overly merry Merry Men in Alan Dwan’s 1922 Robin Hood, bounding through nearly every scene. The rest of the actors were fine, particularly Arlette Marchal as Rosine, later the Countess Almaviva.

The tone also changes across the film, from comedy in the first part, to drama in the second, and then to tragedy (or melodrama?) in the third. The original plays premiered so far apart that the changes might have been less noticeable or made more sense. Mozart, however, was wise to confine himself to the middle play.

Apart from such problems, however, the film is entertaining, as well as being an important example of how ambitious a project French studios could occasionally manage–as does the film immediately below.

Belphégor (1927)

By the 1920s, Hollywood serials had declined from being the center of a program to being a low-budget side attraction. In France, however, serial storytelling remained quite central to the industry. Some serials were presented as discrete episodes, each involving a continuing set of characters, as in a television series. Other installment-films were “ciné-romans,” telling a continuous tale in blocks that might be published at the same time in newspapers and magazines.

Louis Feuillade’s death in 1925 ended his long string of beloved serials and ciné-romans for Gaumont. Other studios made equally popular, big-budget items, including Albatros, with Alexandre Volkoff’s 1923 La Maison du mystère. That film’s reputation lingered in film history despite the unavailability of complete prints until recently. By contrast, Henri Desfontaines’ Belphégor has remained largely forgotten.

Now it has been restored in a beautiful version. Although it, too, centers around a mysterious master criminal out to control the world, it is miles away from the wonderful mid-1910s serials of Feuillade. It’s instead a strange and impressive combination of various elements of French cinema of the 1920s. Where Feuillade shot in a rough-and-tumble way in the streets of Paris or the environs of Nice, with cheap sets for interiors, Belphégor‘s settings immediately remind one of L’Herbier’s L’Inhumaine and L’Argent. In particular, the exterior (above) and interiors (below) of the Baroness Papillon recall that of Claire Lescot in the former film.

Like Figaro, Belphégor has impressive production values and a grasp of Hollywood three-point lighting that creates dark, suspenseful shots. The film gained some prestige by supposedly being the first story to be set inside the Louvre. The interiors, of course, are sets, but ones that successfully convey the look of a major museum at night.

The script has a certain looseness, perhaps caused by the fact that the episodes were being released in parallel to the serialization of Arthur Bernède’s novel in Le Petit Parisien. That journal’s director also headed Cinéromans, a production firm making films exclusively for distribution by Pathé.

A meandering and repetitious plot is not the film’s main problem. The common–and probably correct–assumption that a film’s villain must be a strong, interesting character is completely ignored here. We see “Belphégor” only occasionally, looking like a person dressed in a burka with some checkered decoration around the head. Unlike Fantômas and other Feuillade villains, we never see Belphégor out of costume until the very end. Instead the villain’s machinations are largely carried out by a pair of thugs who have a faintly ludicrous, not-very-dangerous air. Belphégor, when encountered in the Louvre by the guards and investigators, invariably runs and, after a brief chase, escapes.

Oddly enough, the main detective, Chantecoq, is played by René Navarre, so memorable as Fantômas. (He was one of the co-founders of Cinéromans in 1919.) His presence hovers over the film, emphasizing that the main villain is barely present and does little.

Like the two other films discussed here, Belphégor’s pristine restoration, its beautiful sets and cinematography, and the expert lighting make it a pleasure to view. Complete serials from this era are so rare that as an historical document, it is welcome indeed.

Although these three films are not among the masterpieces of the 1920s (though L’Arlésienne comes closest), they give us more insight into French cinema of the day–a national cinema that has remained somewhat in the shadows of the German Expressionist and Soviet Montage movements of the same period.

As usual, the festival held its Il Cinema Ritrovato DVD Awards ceremony, though by this point the competition is dominated by Blu-ray releases. Our friends at The Criterion Collection, Flicker Alley, and Kino Lorber figured prominently in the awards and jury members’ favorites, as did international archives and companies. I have blogged about the two Flicker Alley jury favorites, Waxworks and Spring Night Summer Night.

Figaro (1928).