Archive for the 'Film technique: Editing' Category

Hollywood starts here, or hereabouts

The Woman in White (1917). Toning by DB.

DB here:

Do you know Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White? I hope so.

The traps set by this novel of mystery and suspense–a prototype of what was called “sensation fiction”–are still ensnaring audiences. Serialized in 1859-1860, it became one of the best-selling books of the nineteenth century. Merchandisers pounced on it, offering Woman in White cloaks, bonnets, perfumes, and songs. Stage and film adaptations followed. The Brits, always eager to mine classics, have created no fewer than three TV versions (1982, 1997, and 2018). There’s a pretty good Warners “nervous A” picture from 1948, with Sydney Greenstreet as the deadly, jovial Count Fosco.

The 1917 version from the Thanhouser studio is, lucky us, currently streaming on Vimeo for free. It’s also available on DVD, as part of the excellent series of Thanhouser films. The print is a 1920 re-release, but nothing significant seems missing or altered.

Apart from its entertainment value, the Thanhouser Woman in White can teach us a lot about film history. Why? Because it sums up very forcefully what American narrative cinema could do in that crucial year 1917. Forget your Griffith, leave aside (regretfully, just a moment) your Webers and Harts and Fords and Fairbankses. The mostly unheralded team of screenwriter Lloyd Lonergan and director Ernest C. Warde have given us a concise demonstration of the power harbored by classical Hollywood from the start. The storytelling tools assembled in that era remain with us still.

Women in peril

The novel’s plot is a tale of–well, plots. Counterplots too.

Collins’ book is hugely complicated, swirling together secrets, hidden identities, abduction, impersonations, illegitimate birth, bigamy, insanity, forged records, fake tombstones, assorted hugger-mugger, and timetables that even the author had trouble keeping straight. The intricacy is magnified by Collins’ decision to adopt a “casebook” structure, in which participants and onlookers write up their accounts of what they witnessed. Each piece of testimony is restricted wholly to one character’s viewpoint, and the writers are forbidden to fill in material they learned later. “As the Judge might once have heard it, so the Reader shall hear it now.” This stricture isn’t fully observed, though, because at least one witness sneaks looks at what counterparts have written.

The book’s key image is, of course, the apparition that greets Walter Hartright on the road one sultry night.

There, in the middle of the broad, bright high-road–there, as if it had that moment sprung out of the earth or dropped from the heaven–stood the figure of a solitary Woman, dressed from head to foot in white garments; her face bent in grave inquiry on mine, her hand pointing to the dark cloud over London as I faced her.

Recovering his senses (“It was like a dream”), Hartright listens to her gap-filled story and helps her find a cab. But soon he sees two bravos halt their carriage and hail a policeman. They ask: Has he seen a woman in white? No. Why does it matter? What has she done?

“Done! She has escaped from my Asylum. Don’t forget: a woman in white. Drive on.”

The first installment ends here, and the adolescent window opens a little wider.

The main plot centers on Laura Fairlie and her half-sister Marian. Hartright is engaged as Laura’s drawing teacher and they fall in love. But Laura’s father has promised her to Sir Perceval Glyde, an apparently upright aristo. (Collins was opposed to marriage as an institution. His class hatred comes out as well, though perhaps not as scathingly as it does in his other masterpiece, The Moonstone.) Once the marriage takes place, Glyde introduces into the household Count Fosco, a suave “doctor” with the habit of letting his pet mice scamper around his waistcoat. It doesn’t take long for Marian to realize that Glyde has a Secret, and she must turn detective to protect Laura from him.

Without pressing into spoilers, you can already tell that this lays down a template for the sort of story Hollywood would later love to tell. The Woman in White is a prototype for the woman-in-peril plot that we’ll find in Suspicion (1941), Shadow of a Doubt (1943), The Spiral Staircase (1946), The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947), Sleep My Love (1948), and many 1940s classics. These in turn rely on literary works in Collins’ wake by Mary Roberts Rinehart, Mignon Eberhart, and other women authors who updated Gothic and sensation-fiction conventions for the twentieth century.

Lloyd Lonergan was said to have suggested reducing the eight-reel cut of The Woman in White to only six. It’s indeed a tightly coiled presentation of Collins’ sprawling plot. Swathes of backstory are dropped. Instead of Collins’ multiple narrators we get an omniscient narration that shifts freely across various intrigues. Fairly quickly we learn that Glyde and Dr. Cumeo (the Fosco of the novel) are scheming to switch Laura with her lookalike Anne, the woman in white. We also realize that Marian, as an obstacle to the plan, is in mortal danger. Thanks to crosscutting, we’re aware of several lines of action unfolding at once, and in a film full of spying and eavesdropping, compositions tell us who’s snooping on whom.

Still, some revelations are saved for the end, notably one that looks forward to the flashback-heavy 1940s. When Laura and Marian discover Glyde’s secret, their informant gives them the crucial information in a flashback, which precipitates a fiery climax. The flashback device was previewed when Marian, recovering from her collapse, recalled the plans she heard on the patio between Glyde and Cumeo; a nearly Surrealist dissolve superimposes that earlier scene.

In preferring to give us a lot of information, favoring suspense over surprise, this Woman in White is typical of Hollywood scriptwriting of the classical years. In particular, the film employs strategies later elaborated by Hitchcock (discussed here and here and here). One scene in particular displays the Hitchcock touch, years before Sir Alfred took up filmmaking. Even more specifically, let’s note that the basic situation looks forward to Notorious: a woman imprisoned by her husband and a confederate is slowly softened up for disposal.

Choreography, cutting, and showing us the door

Anyone who has viewed films with critical attention must be aware that in a film we are constantly, and without knowing it, being directed what to look at. In a stage play you may be looking at one moment at the actor who is speaking; at another moment watching the face of the person addressed, or observing the behaviour of other characters on the stage. If you go repeatedly to the same play, you may choose to look at different actors in a different order, for you certainly cannot observe everybody and everything simultaneously. But in a film, the lens of the camera is constantly telling you wha to look at–it may be a close-up of the actor’s hand, by the movement of which he betrays the emotion not visible in his face.

T. S. Eliot, 1951

The 1910s were an exciting era in cinema because, as I try to show in this video lecture, the foundations of “our cinema” were laid then. The film business, movie culture, and mass audiences settled into patterns that would hold for over a hundred years.

Just as important, the forms and styles of film craft were put in place. Among those changes was a transition from a style that relied on performance and staging to an approach more reliant on editing, on breaking scenes into many shots. The dominance of editing as a principle of guiding attention is evident from the Eliot quotation; he can’t conceive that staging, lighting, and other “theatrical” techniques could steer us to the important parts of the action.

The earlier, “tableau” approach to scenes was perfectly capable of funneling attention too, but editing had many advantages, both economic and aesthetic. By 1917, as Kristin and Janet Staiger and I argued in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, the editing-based approach had coalesced into the dominant style. The Woman in White is a nifty illustration of what an ordinary film from that year could accomplish with cutting–while still retaining vestiges of the tableau style.

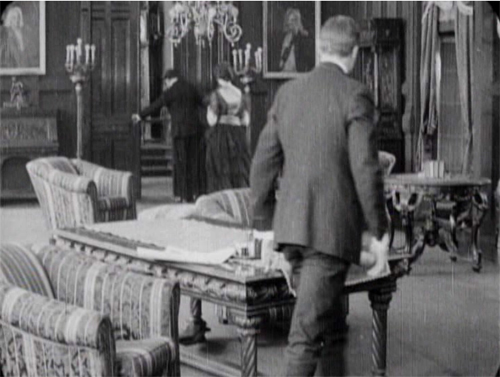

A simple example of the tableau technique comes when Sir Perceval Glyde calls on Laura and Marian. He has just kissed Laura’s unwilling hand, and Marian comes up from the rear of the shot to him. As she moves forward, Laura shifts aside slightly to clear our view of the others. This choreography doesn’t seem stilted because it expresses Laura’s withdrawal from her fiancé.

This is an example of the Cross, the staging technique that coordinates actors’ switching positions in the frame. Marian moves from frame left to frame right as Laura shifts to the left.

The tableau approach often plays between a lateral arrangement of characters in the foreground and a more diagonal array of figures packed into depth. As the shot unfolds, Marian is given a beat to take notice of Laura’s reaction as Glyde retreats to the background. She conveniently blocks his departure as she looks warily back at him.

But Glyde steps back into visibility in the distance as he says goodbye, with the women turning away from us so that we’re sure to concentrate on him. Then as the women turn back to react, he can be glimpsed leaving on the far right.

Doorways in the distance, characters advancing to and retreating from the camera, figures spreading themselves out horizontally but also blocking our view of things behind them, only to reveal them at the right moment–these tactics of the tableau became supple and subtle during the late 1900s and throughout the 1910s.

Eliot need not have worried that our attention would stray. Centering, frontality, movement vs. stasis, lighting, gesture, and other creative choices push us to notice the important elements of the scene. And these factors aren’t equivalent to what we see on the theatre stage; the optical properties of the camera lens create a very different playing space. (See here and here.)

Tableau staging hung on in editing-driven cinema, but it tended to be relegated to the role of an establishing shot. The first part of this scene consists of another tableau setup broken by a cut when the slimy Glyde kisses Laura’s hand.

Here the closer view underscores his gesture while isolating Laura’s concern.

The coordination of staging and cutting is nicely shown when Walter Hartright, having resigned from his post as Laura’s teacher, accidentallly encounters Glyde at the train station. Glyde is coming to arrange his marriage to Laura, so the plot needs to establish the friction between the two men early on. As they confront each other, Glyde’s assistant loads his luggage into the cab in the background.

The first phase of the scene choreographs the men’s encounter through the Cross.

Then close views underscore the significance of the encounter.

Cut back to a two-shot that reorients us.

The fact that it’s not the same framing as we saw at the start indicates the reliance of the style on editing; even the full view is re-calibrated in light of changing shot scales. And during the shot of Walter, Glyde’s position has changed from his orientation in his medium shot. That’s the sort of flexibility editing gives you. The new arrangement heightens the clash of the two men. (Typical of the 1910s emphasis on depth, Glyde’s assistant and the driver continue to load the cab in the background.)

Glyde’s enlarged hand kiss and the inserts of the two men in the station scene exemplify the axial cut. This is a cut made along the lens axis of the camera–a straightforward enlargement of a chunk of space. It’s very common in 1910s cinema, and it’s still around, though it’s not as common as it was. Editors came to prefer analytical cuts that were more angular, yielding less the sense of a sudden enlargement. Sometimes you’ll see claims that cut-ins or cut-backs should shift the angle by 30 degrees. Yet Kurosawa and Eisenstein made powerful use of the axial cut, and it’s sometimes used as a self-conscious device. During the 1910s, some directors began using the over-the-shoulder (OTS) framing as a way to assure distinct angle changes.

The cut to Glyde’s creepy kiss is also a match on action, smoothly linking Glyde’s gesture across the shot change. This too emerged in the 1910s and became a mainstay of classic editing technique, to this day. (See my earlier post on Watchmen for contemporary examples.)

The Woman in White has several adroit matches on action, which shows that the learning curve among directors was more or less complete by 1917. When Walter first encounters the mysterious woman on the road, his striking a match is carried across a cut, with the second shot introducing her coming toward in him n the distance.

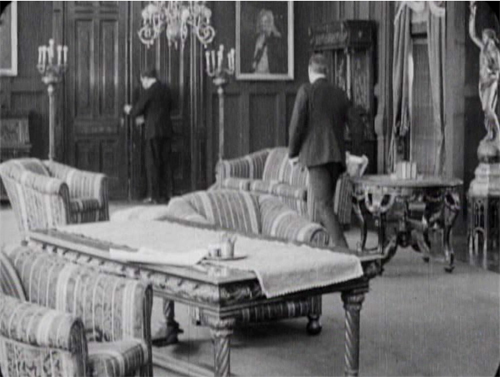

One of the most common editing devices of classical continuity is the eyeline match, and filmmakers were mastering this from quite early on. By 1917, it was part of every director’s tool kit. We can see how it works together with the other techniques in a fine, smooth scene that leads up to a crucial turning point in the action. Glyde and Dr. Cuneo are in the library, where Marian is uneasily reading a novel. Cuneo moseys over behind her, softly threatening, and an axial cut matching his movement lets us know she notices.

Another match on action brings her off the sofa. Love those delicately splayed fingers.

As she starts to leave, we get the Cross, as Glyde rises from his armchair and goes frame right. We now get the start of a major piece of business: Cuneo’s byplay with the sliding doors.

Securing their privacy, Cuneo prepares to consult with Glyde about their skulduggery. But a match on action, carried by a powerful axial cut–a huge enlargement from the extreme long shot setup–alerts us. He’s listening.

Another match on action as he busies himself with the door. A new diagonal composition prepares us for a shot of Glyde to come shortly. And yet again Cuneo is matched as he opens the door.

The payoff: Cuneo has detected Marian outside listening. She bluffs, saying she left her novel behind.

Now comes the shot that was prepared for by the over-the-shoulder long shot above. It’s not an axial cut, but a genuine reverse angle on Glyde, who’s suspicious about Marian’s return.

This is a killer shot because the camera can assume a drastically new position. It has put us in between the characters in a way we weren’t in the station scene. In effect, there’s an axis of action running from Glyde to the doctor and Marian at the door. The reverse angle is a one-off technique at this moment, but the possibility of penetrating the dramatic space in this way will be central to continuity cutting.

Now tableau principles can kick in. Marian comes forward and gets the book while Cuneo watches warily in the background.

In the course of the shot, Marian leaves, and this time, thanks to deep staging, we and the plotters can see she’s not eavesdropping. As she goes upstairs, Cuneo closes the door and the men can settle down to scheming.

Five matches on action, a striking eyeline match, restrained but pointed performances, and a cogent staging of the action have yielded a vigorous, engaging scene. By 1917, classical screen storytelling is well established in even a run-of-the-mill production. But there’s nothing run-of-the-mill about the suspense that follows this trim tension-builder.

1910s noir rides again

The Woman in White illustrates a lot of other 1910s innovations in pictorial storytelling. There are, for instance, some concise special effects, as when on Laura’s wedding day she sees herself and Walter in her vanity mirror.

There are also dramatic lighting effects, motivated by firelight, single lamps, and eventually lightning flashes.

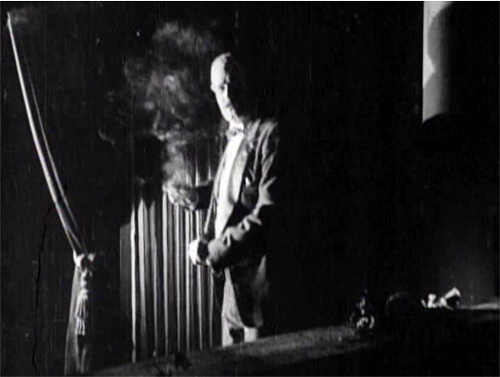

But more audacious is a sustained experiment in “1910s noir.” At that period filmmakers began associating crime and mystery with shadows and stark lighting. (See this entry.) When Glyde and Dr. Cuneo adjourn to the terrace to discuss their scheme, we get a remarkable instance. I won’t indulge my impulse to shower you with images, but I’ll try to suggest why you should try to see the sequence for yourself.

While the men smoke and talk outside, Marian has seen to the sleeping Laura before going to her own bedroom. (A sign of the film’s tidiness is the way it establishes the main characters’ rooms in the upstairs hallway. This geography becomes important when Glyde and Cuneo exchange Anne for Laura.) Opening her window, Marian hears the men outside and ventures onto the balcony above them. This yields a remarkable extreme long shot: She eavesdrops from above.

It’s a difficult shot by later standards. The main action is wildly decentered, set off on the right. But at least this framing has the virtue of preparing us for the later development of the scene, which will involve Marian sneaking along the balcony back to her room, where the light comes from.

The vertical layout of the action is immediately clarified by two closer shots, a lovely chiaroscuro image of the men and the other of Marian listening.

She hears just enough to suggest the men’s scheme before complications ensue. Glyde goes inside and upstairs, where he might discover her. Meanwhile, a rainstorm starts, and Marian dislodges a potted plant. Cuneo turns, in a new setup that emphasizes the railing in the right foreground, so that we can see the fallen plant. The shattered pot is given a close-up more or less from Cuneo’s viewpoint. His reaction supplies a moment of suspicion.

Marian, now drenched by rain, seems trapped between her two adversaries. Will one or both discover her?

Glyde who has gone to Laura’s window and is looking around outside. We’re reoriented through a new master shot of the house, a framing that varies from the original setup. The shot shows both Laura’s and Marian’s windows lit. There follows a dark passage in which Marian creeps up to Laura’s window. That action takes place in the shot I’ve put up above.

An extra twist: Glyde looks out, but then pulls the shade. Little things mean a lot. A soaked Marian manages to crawl back through her window.

Apart from its virtuosity in handling cutting and lighting, the sequence is crucial for the plot. Marian collapses from her exposure to the storm, and her illness provides a pretext for Cuneo to isolate her while he and Glyde proceed with their plan.

I invoke Hitchcock because this long passage of suspense depends on our knowing all the relevant factors in the situation, and the possibility of a giveaway–the smashed plant–drives up the tension. What I’m really saying, I guess, is that Hitchcock expanded and deepened story mechanics that were already in place in the silent era. Apart from refining them, he managed to brand them as his own.

No film from 1917 or thereabouts is faultless in executing the new editing-based style. The Woman in White has its share of mismatches. Then again, so do movies from the 1920s to the present. (Don’t get me started on the mismatched cuts in The Irishman, 2019.) The crucial point is that the system of Hollywood storytelling and style is in place, and not in a crude form. Talk all you want about post-classical cinema, chaos cinema, post-cinema–whatever. The variations we detect today arise against a background of stable norms that remain a lingua franca of world filmmaking, and they’re headed well into their next century.

Thanks to Ned Thanhouser for years of faithful service to the studio’s legacy. Now is an ideal time to visit his site for background on this remarkable company and the efforts to preserve its output. A staggering 132 Thanouser films are available for streaming on Ned’s Vimeo channel.

To find out more about what preceded this crystallization of techniques, see Charlie Keil’s Early American Cinema in Transition: Story, Style, and Filmmaking 1907-1913 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2002).

An excellent survey of Collins’ place in the history of dossier novels is A. B. Emrys, Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011). Her treatment of Caspary and Laura, both favorites of this blog, is just as valuable. My quotation from T. S. Eliot comes from “Poetry and Film: Mr. T. S. Eliot’s Views,” in The Complete Prose of T. S. Eliot: The Critical Edition, vol. 4: A European Society, 1947-1953, ed. Iman Javadi and Ronald Schuchard (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2018), 581.

For lots more on 1910s storytelling, see the categories 1910s Cinema and Tableau Staging. Flashbacks, the woman-in-peril plot, and other conventions that coalesce in the 1940s are discussed in my Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling.

The Woman in White (1917). Toning by DB.

Who will match the Watchmen?

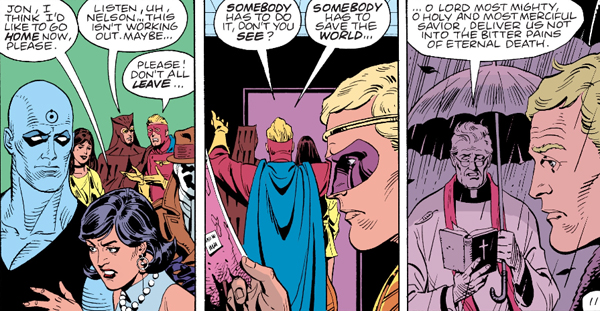

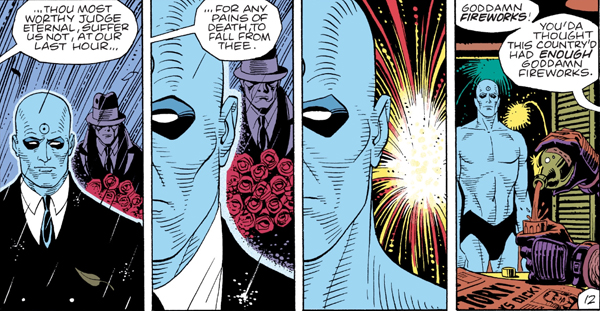

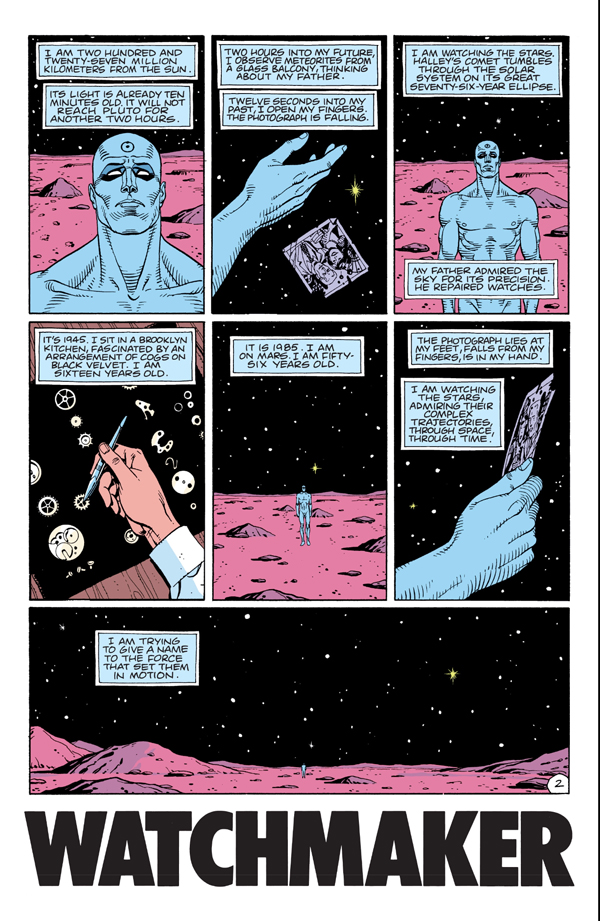

Watchmen (2019), Episode 7.

DB here:

If we want to understand the craft of filmmaking, we should pay attention to what filmmakers say about their technique. Sometimes we have to confirm what they tell us with other evidence and the onscreen results, but practitioners usually offer unique angles on their creative choices. For this reason I found it fascinating to come upon what Director of Photography Gregory Middleton had to say about his work on HBO’s limited-series Watchmen.

I had read the comic back in the 1980s and was intrigued by its experiments in pictorial storytelling. I’d also seen the movie, which I thought not as adventurous as the book and vitiated by the book’s adolescent nihilism. (Your mileage may vary.) But Middleton’s interview made me watch the series. So I thought I’d use this anxious pause in normal activities to share some ideas with you.

Middleton has a lot to say about the visual design, such as the sort of lenses he used to get startling depth effects. These echo some common graphic-novel compositions.

But I got more interested in other questions. How does the show adapt some classical cutting techniques? And how do those techniques square with the “editing” techniques we get in the original comic?

Here’s the relevant passage:

And transitions are the biggest tell when you cut from a beat of one thing to a beat of something else. In the case of the comics, one of the transitional devices we wanted to use to echo the graphic novel is the match cut. In the comic you’ve got one panel with a character in the foreground and someone in the background. The next panel is the same character in the foreground, but they are somewhere else — or somewhere else in a different outfit. And the background is something similar, but it’s something else, and you’re basically just jumping time because you’re really with the character and where their state of mind is, so the intervening time between how they went from here to there is irrelevant.

There is a great one in episode two where Angela walks back after they just sat down, and she sort of disagrees with the idea of going to rustle up the people at Nixonville, and she walks away, and she’s pacing as a match cut to her pacing at the police lineup at Nixonville. You go right where she’s thinking, like Okay, I don’t want to be here, but now I’m gonna be here, and suddenly you’re right there.

The match cut is also a way to instantly transport the audience without introducing a lot of other extraneous visual information. In episode four, we did her opening and closing her trunk when she is going to just get rid of the wheelchair she’s cut apart. She chucks it in the trunk, slams the trunk, and it’s a match cut to her opening the trunk, and she’s already somewhere else. And that just works — you don’t need to see her driving and parking and all that. The point is you just know she is dumping this thing, and it’s a nice, clever way to keep you on point with where she is with her intent.

Afterward, it’s like he’s just jumped ahead again — both places, same time. So it’s a way to sort of double-use that technique. It just takes a lot of planning and preparation. Nicole [Kassell, director/producer] and I worked hard on all the transitions in that episode to try and achieve that effect and make it interesting.

The transitions between scenes that Middleton is discussing are, I think, what have been since the 1940s called “hooks.” His comments open up some ideas about how editing works with them.

There are some spoilers, but not my usual quota.

Matchmaking

We can enhance our understanding of filmmakers’ creative options if we systematize a little bit the choices they face and the terms they use. That’s what I try to do in the online essay on hooks between scenes. There I suggest that we can have four sorts of palpable hooks from shot to shot: sound/sound, sound/image, image/sound, image/image. My examples come from National Treasure (2004), a movie that revels in tricky transitions.

For example, one transition in Watchmen creates a sound/ image hook. The Game Warden tells Adrian, “No Mercy” and we cut to a close-up of a Mercy perfume being tested on a focus group.

Middleton calls the cuts that create image/ image hooks “matches.” “Match” is a broad term that points up a general principle of cutting for continuity. In a match shot-change, which might be a cut or a dissolve, something in shot B picks up something that was in shot A. Without distinguishing different types of matching, Middleton is stressing how continuity editing techniques, normally applied within scenes, can be used as transitions between scenes as well.

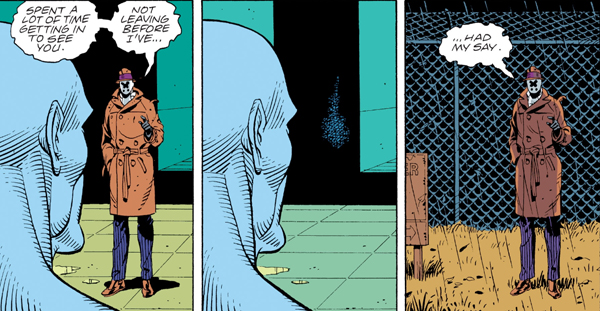

So let’s create an initial menu of possibilities. Within scenes, there’s the eyeline match, which shows a single character looking, followed by a shot of what the character sees (not necessarily from their optical viewpoint).

Shot/reverse exchanges like this one often rely on the eyeline match, but need not; you can have a shot/reverse pattern if the characters aren’t looking at each other. (Imagine two people talking with their backs to each other.) The eyeline match can link more than two characters within story space.

There’s also the match on action, where a bit of movement in A is carried over into B, despite the change of camera position. The scene between Wade and Angela continues with a combination of the eyeline match and the match on action.

Another sort of match plays upon the sheer pictorial qualities of the two shots. As Middleton says, shapes and color patches can be carried over from the background or foreground or both. Filmmakers don’t seem to have developed a specific term for this type of shot change, although they were clearly using it from at least the 1920s onward. (Eisenstein was the most explicit.) In Film Art: An Introduction, Kristin and I proposed calling the lining-up of compositional features from A to B a graphic match.

Precise graphic matches are common in experimental films, but they seldom show up within scenes of narrative films. Still, Eisenstein, Lang, Ozu (here, from An Autumn Afternoon), and a few other directors made bold use of them. And they’re obviously a matter of degree: Ozu can match an overall shot in some detail, as above, or just one portion of the frame.

We might add the possibility of the “category match,” as when a prop in shot A is followed by something comparable in shot B. Imagine cuts among wanted posters inside a sheriff’s office.

When we move beyond the individual scene, what are the possibilities? Clearly, all types of match-cutting can be used for transitions.

In Watchmen, an eyeline match shifts us from Angela, lying wounded on her living room floor, to a view of Judd looking down at her in the hospital when she awakens. Here the eyeline yields an optical POV.

A match on action takes us from one scene of Cal opening his hand to another as Angela reaches for the hydrogen-atom ring.

A hook can also exploit a graphic match. As Laurie lies sideways after a bomb blast, the image dissolves to a similar composition, a twisting view of a masked bust.

Middleton points to one striking moment that viewers are likely to notice: a match on action that’s also a bold graphic match. Angela strides away from one scene and continues her movement, and her compositional thrust, in a new location, Nixonville.

The “category match” is at work on occasion too, as when one scene ends on a pocket watch and the next starts on a clock face.

The category match blends with the graphic match when hands links scenes.

What seems to have sensitized the show’s creators to the possibilities of hooks is the fact that the Moore/Gibbons comic makes punchy use of graphic matches between panels. These are often used to signal character memories by opening and closing flashbacks.

Vivid as these examples and others are, the hook, even the graphically matched one, has a long lineage, as my essay tries to show. The creators of Watchmen are working in a distinct tradition of classic filmmaking.

Showing and showing off

More broadly, that classic tradition favors speed and quick pickup. The new Watchmen is essentially a police procedural, unlike the comic and the feature film. Accordingly, the investigation of a crime is interwoven with the personal lives of the police, the “cop soap opera” that brings in friends, family, lovers, and secrets from the investigators’ pasts.

The crucial backstory involves Angela Abar, who knits together many threads. The child of a US black soldier and a Vietnamese woman, she became a policewoman in Tulsa and underwent the new militarization of the force in response to white supremacy. Some of the earlier Watchmen team, notably Adrian Veidt and Dr. Manhattan, are still exercising their power, while Laurie Blake, the daughter of Silk Spectre, is now working for the FBI.

Like the comic, the series must move the plot swiftly between past and present. The comic splinters time more audaciously, jumping back and forth across its grid of nine vertical panels. But in a classical film, where you don’t normally pause or go back, the story must unwind linearly, and so other strategies come forward to impose a felt pattern.

Older films might dwell on the aftermath of a scene, letting the tension relax a little, and provide a cadence that marks off a distinct section. Modern films, especially if they’re presented in the distracting environment of home viewing, display a need to maintain a rapid pace. So scenes push to a high point, then provide a “button” like that close-up of Laurie, and then move swiftly to the next. Among other advantages, this tactic keeps people from pausing or changing the input. Still, the scene shifts need to be clear fairly quickly.

Hooks can help on both fronts. They snap up the pace, keep us alert, maintain interest from moment to moment. A less clear-cut hook can provide a bump of surprise that teases us into the next scene. Soon, though, we will get imagery, and especially dialogue, that anchors us in the ongoing action.

Hooks also provide motifs that can cascade through the film. Adrian’s ambitions to be the new Alexander the Great are provided by cuts that mock his pretentions.

And, as in the comic, the cinematic hooks facilitate subjectivity. The most common way classical storytelling justifies unrealistic or nonlinear narration is through getting into characters’ heads. (Middleton: “You’re really with the character and where their state of mind is.”) Abrupt and startling cuts can be motivated if what we see is a memory, a dream, or a hallucination. This is what we get when Angela embraces Judd’s legs: a match-on-action hook to a flashback of her slow-dancing with Cal.

The most elaborate hooks can provide something more: a certain elation in virtuosity. The precise matching of Angela’s stride across those two scenes above is a stylistic flourish that asks us to appreciate the care and bravado of the filmmakers.

Watchmen‘s hooks, however flamboyant, stand out against a pervasive backdrop of classically constructed scenes. We get lots of over-the-shoulder reverse angles, properly timed reaction shots, now-standard cuts to extreme distant shots that provide a “beat” for the scene, and other devices that have been around for decades. Plenty of other traditional strategies for narrative coherence are on display, from goal-oriented protagonists and deadlines to newspaper headlines and TV broadcasts as sources of impersonal narration. There’s even the inevitable Hollywood line: “What are you doing here?” As usual, striking moments emerge out of a familiar flow of narrative cause and effect, with some mysterious gaps eventually filled.

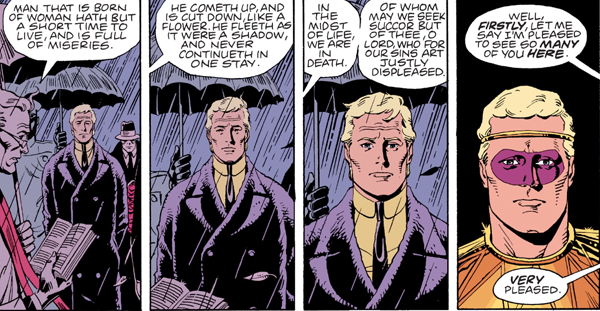

Paging the Watchmen

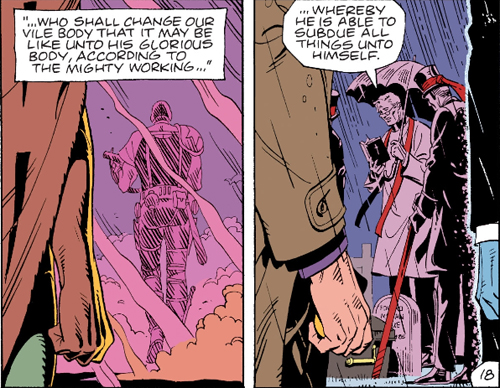

Comics artists absorbed the lessons of continuity filmmaking. If the hooks in films stand out by contrast with the overall smoothness and linearity of classic construction, something similar happens in comics. Here are three “continuity shots” from the Watchmen graphic novel, complete with obedience to the axis of action, reverse-angle cutting, and a “single” for emphasis on Rorschach’s reaction.

Even a match-on-action hook can be suggested, as when Laurie’s lifting a goblet on Mars “cuts” to her as a teenager lifting a dumbbell.

Graphic continuities and discontinuities can be motivated by science-fiction premises, as when Dr. Manhattan teleports Rorschach out of the facility. The sense of instantaneous change wouldn’t be so strong if Rorschach’s size and placement in the format weren’t kept constant.

In a way, the graphic continuities are almost needed for the time-shifting transitions. A new angle on Adrian at the start of the funeral flashback below would be more confusing than the frontal close-up that completes a gradual enlargement of his face. The new costume and the “offscreen” dialogue cue us to a new scene.

To keep things tidy, the flashback ends with a foreground graphic match on Adrian, leading us back to the funeral.

As ever, popular narrative maintains symmetry and redundancy to keep the action clear. Here’s a more “staggered” but no less symmetrical foreground graphic match–used, again, for subjectivity.

The rectilinear staging evokes either a track-in (the first two panels) and a track-back (the last two) or axial cuts in to and back from Dr. Manhattan. (The Soviets called these in-and-out edits “accordion” cuts.)

So there are some rough equivalents between film editing and the principles binding comic panels, especially ones this jammed with information. But comics have unique resources too–ones that Watchmen‘s creators were well aware of. Dave Gibbons notes that he exploited techniques articulated by the great Will Eisner, “where you could, say, hold the camera’s point of view and have characters walk past it, or follow the characters through a scene acrosss a changing background, where you could echo panel compositions . . . .”

The echoes Gibbons mentions depend on the fact that the book page and its role in a two-page spread create a force-field that displays the story both as a timeline and a spatial array. Panels are at once phases of action and a simultaneous order of images, and the interplay of story information and pictorial pattern can become quite rich, even baroque.

Consider when Rorschach rummages in the Comedian’s closet. Even if we could replicate the panels in a movie shot by shot, the page’s severe structure couldn’t be grasped as a simultaneous whole onscreen.

The echoes are striking. Panel 1, the establishing shot, is enlarged in panel 7 on the bottom row, as is panel 2 in panel 8. Each lower-tier mate is markedly closer than the top one, emphasizing the growing sense of discovery. Panel 2, with its sidelong strips of solid black, is echoed in panel 4 and panel 6 (a slight “pan” left from 4) and, with another enlargement, in panel 9, the climax. The color slabs (yellow/black, grey/purple) accentuate the repetitions and variations. The middle stretch, panels 3-6, forms a suite of variations as well (5 picks up 3, 6 picks up 4), while Eisensteinian cuts flip us back and forth across the axis formed by the straightened coat hanger. All the cuts are compass-point shifts, moving us in 90-degree multiples. The crisp geometry of the découpage renders the unhurried professionalism of Rorschach’s search, an effect accentuated by the snapshot imagery (no motion lines).

The effect depends in large part on the presence of all these images on the page at once. The alternation of shot scale and color fields can be discerned only by seeing the overall architecture of the page.

Panels 1, 3, and 5 build to the climax of the wide framing on the bottom as we pull farther back from Dr. Manhattan during his soliloquy. Panels 2 and 6, echoes of a close-up of the photograph, provide a sharp contrast to the landscape and emphasize the power of memory. That power is enacted in another variant of the hand image, as the young Jon Osterman arranges watch parts, like stars, on a velvet ground.

The page is one standard mid-size unit for the comics story, but the two-page spread is the next phase up. A continuous action can be spread across the open book, with echoes emerging. In the big fight scene, the shifting POV (occasionally objective, but also bouncing us among Rorschach, Adrian, and Daniel) is capped by symmetrical wide panels at the bottom of each page. The rose-tinted panels on the right page add their own fillip of pattern.

In a film such symmetries and variations unfold over time. We can make them apparent only through a “spatialized” analysis, spread out on the page like a comic-album layout. (Such were those pioneered by Raymond Bellour in the 1960s and 1970s.) In comics, these patterns strike us immediately, as a primary and palpable expressive vehicle. One-off devices like the graphic match can be sustained both on the screen and on the page, but each medium stamps its own structures on the flow of time.

There’s a lot more chop and change in the space-time continuum of the Watchmen comic than I can do justice to here. (Some pages run three time periods simultaneously.) But my main point should be clear. As usual, when we start to pay attention to the films and media artifacts that fascinate us, we always find more going on than we realized. Both movies and comics work on us so directly that their design subtleties can easily pass unnoticed. We can keep reverse-engineering them as long as we like, and we’ll learn a lot. And the creators can be very helpful guides about what to pay attention to.

I first became aware of Gregory Middleton’s comments by reading the review essay by Namwali Serpell, “In the Time of Monsters,” New York Review of Books (9 April 2020). I’m grateful to Serpell for calling my attention to the problem of cutting in the Watchmen series.

The essay is somewhat misleading in its account of match cutting, which is said to create “‘jumps’ rather than flows from shot to shot.” It’s actually just the opposite. The match cut creates continuity of time, space, and graphics between shots. It need not, as the essay claims, link two settings, and it’s not an alternative to a “splice cut,” which is a term with no currency I’m aware of. (A splice is simply the physical join between film strips, and it can govern any type of cut. Splices are increasingly rare with the dominance of digital editing.) The alternative to match cutting would be discontinuity cutting.

Serpell’s essay is worth reading for its interpretive dimension. She argues that for all the creators’ efforts to create strong images of minority heroes fighting white supremacy, there is a critical, antiheroic aspect to the original comic that isn’t picked up in the series. The sanctioned violence of Angela, Wade, and others is treated as unproblematically righteous.

I’d largely agree. Yet I’m not sure that the original book’s portrayal of superhero trauma (the result of the go-to source, childhood abuse) elevates these caped crusaders much. They seem to me best understood as part of that cycle of debunked superheroes we find in other 80s comics, notably The Dark Knight. Why would someone put on a mask to fight crime alone? What dignifies vigilantism? Are these “the heroes we need now”? These, we’re told, are deep questions, but they seem to me the tropes of a quickly standardized set of conventions. They signal a “new complexity” and “adult attitude” comparable to the romanticism of film noir and the cynicism about samurai ideals we find in Japanese swordplay movies. Bringing heroic genres low is itself a genre convention.

More broadly, I’d propose that the the storytelling strategy Serpell highlights is part of the common move within thematically ambitious mass-market movies to be strategically ambiguous. Creators, I’ve suggested here, often throw many things against the wall to see what will stick. They can then point to contradictory aspects which show balance. So yes, Angela tortures members of the Seventh Kavalry, but (a) they’d do the same to her; and (b) she’s driven by righteous vengeance for ancient wrongs; and (c) we want to make you a little uncomfortable with her vigilantism anyhow. Nowadays, it may be that what seem involuntary contradictions are deliberate efforts to have things many ways at once. This maximizes viewer outreach and gives critics fodder for debate. For another recent instance, see the previous entry on The Hunt.

The Dave Gibbons quotation comes from the supplement “The Phenomenon: The Comic That Changed Comics” available on the DVD of the Director’s Cut of Watchmen, 9:35-10:14.

Raymond Bellour’s “spatialized” analyses of repetition and variation can be found collected in The Analysis of Film (Indiana University Press, 2001). Some efforts of mine are in On the History of Film Style and in Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (available for free, if patient download here), as well as in other material on this site.

Watchmen (2019).

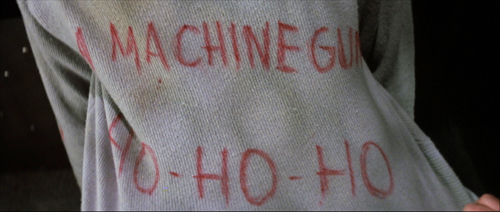

Not just a Christmas movie: DIE HARD on the big screen

Die Hard (1988).

DB here:

It’s been quite a fall season for UW–Madison film culture. There were visits from avant-garde legend Larry Gottheim, New York Times co-chief film critic Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston (Senior VP of Mastering at Disney), and Julia Reichert, whose American Factory is now routinely turning up on ten-best lists. The semester’s first screening at our Cinematheque was Kiril Mkhanosvsky’s Give Me Liberty, a Milwaukee movie also gracing year-end best lists. Our programs included restored films by African pioneer Paulin Soumanou Vieyra, retrospectives of Reichert and Kiarostami, a 3D double feature of Revenge of the Creature and Parasite (no, the other one), a program of early women directors in America, a selection of films conserved by the Chicago Film Society, and a miscellany ranging from Olivia and Near Dark to Tropical Malady and Red Rock West.

Travels to festivals, partly covered in our blog entries, forced us to miss too many of these shows. But we couldn’t miss the final one: Die Hard (1988).

It’s a film I’ve admired since I first saw it in summer of 1988. I’ve taught it in many classes, but never written about it. Seeing it again, in a pretty 35mm print from the Chicago Film Society, has made me want to say a few things as my final blog entry for this busy year.

The man between

Think-piece pundits like to say that Hollywood movies are about good guys versus bad guys. But usually things are more complicated. Very often the good guy is an outsider caught between two large-scale forces, good or bad or both–the cattle ranchers versus the townspeople, or the mob versus the cops. Often the protagonist is an outlier, forced to solve the problem using means that respectable social forces can’t.

Call it the problem of the House Democrats. When the lawbreaker can’t be brought to justice, how do you make him pay? The answer is one that William S. Hart movies provided in the 1910s. We need a “good bad man,” a rogue agent who knows the scheme from the inside but is willing to do the right thing. Which means that he has to be flawed too, a little or a lot, and that he can eventually reform.

In Die Hard, the forces of law and order line up as the Los Angeles police and the FBI. The threat is Hans Gruber’s gang, posing as terrorists but actually planning to rob the Nakatomi Corporation of $640 million in bearer bonds and kill lots of hostages in the process. The naive TV broadcasters support both, recycling official scenarios of how hostage-taking works and reinforcing the gang’s masquerade as a terrorist group.

The contrasts are marked. The forces of order are American, in alliance with a Japanese company, while the attackers are Europeans. At the start, we hear American music (the rap played by the limo driver Argyle), but Hans hums Beethoven. The cops’ technology notably fails, as when the assault vehicle and a helicopter are consumed by firepower. But the gang’s hi-tech expert Theo can crack the vault, assisted by Hans’ plan to push the Feds to cut the building power.

Above all, the forces of social order are strikingly inept, while the gang is ruthlessly efficient. Unlike the police, who “run the terrorist playbook,” Hans boasts that he has left nothing to chance. The cops can’t imagine an adversary that exploits the official by-the-book procedures. As for the business types, Takagi’s calm bluff and Ellis’s freewheeling jargon can’t cope with a gang leader who doesn’t get the Art of the Deal.

Clearly, America and Japan need help. That appears in the form of John McClane, the cop from the East Coast trapped in Nakatomi Plaza.

McLane is the man between, spatially and strategically. He witnesses the action from inside the skyscraper, and bit by bit he figures out the gang’s real scenario. And he’s caught between both forces. The gang tries to find and kill him, while the cops refuse to recognize him as an ally. Confronting Karl’s brother early on teaches McClane that he can’t play by procedure. (“There are rules for policemen,” says a thug who doesn’t believe in rules.) The LAPD’s ineptitude shows that McClane can’t expect help on that front. So he must become almost as reckless as his adversary, though in a virtuous cause. This principally means blowing stuff up.

McClane isn’t totally without resources. He has as helpers Al, the desk cop who comes on the scene and sustains his morale, and Argyle, who’s there to play a crucial role at the climax. But mostly he’s alone in facing problems. He needs weapons. He needs shoes. He needs to protect the hostages, most of all his wife Holly, who has climbed up the corporate ladder. (In another movie, she would be the in-between protagonist.) To keep Holly from becoming a bargaining chip, McClane needs to hide his identity. And he needs to figure out the gang’s ultimate plan, of seeding the rooftop with explosives that will destroy the building and cover their escape.

John’s solutions are notably low-tech. While the police and the gang depend on advanced firepower and computer finagling, McClane lashes an explosive to a desk chair and uses a fire hose as a rope. He has to improvise shoes by taping a maxi-pad to a bleeding foot. No holster for your automatic? How about some Christmas wrapping tape? And don’t forget to taunt your adversaries with Yankee wisecracks.

In the course of this drama, the very physical McClane becomes a model for his allies. Holly punches the reporter who revealed John’s identity, and Argyle cold-cocks Theo at the point of getaway. Most dramatically Al kills the revived Karl when he’s about to plug McClane. The people in between take up arms.

McClane and his allies solve the House Democrats’ problem. Law can’t be lawless, even in protecting itself. Business, always aiming at the bottom line, has to give up principles. (“Pearl Harbor didn’t work out, so we got you with tape decks.”) These forces of social order are inefficient, trusting, and superficial. They can’t stand up to sheer brutal onslaught. In a crisis they will fold, or simply choose the nuclear option: agents Johnson and Johnson are ready to lose a big chunk of hostages.

McClane is a mediating figure that permits the film to show you can be strategically lawless for the sake of lawfulness. The fly in the ointment, the monkey in the wrench, screws up plans on both sides, but for the benefit of everyone else.

The Big Dumb Action Picture isn’t so dumb

This thick array of thematic parallels would be interesting in itself, but it gets worked out through precise storytelling. There was a time when critics knocked action movies as simply ragbag assortments of fights, chases, and explosions. Die Hard, I think, changed ideas of just how well-wrought an action picture could be. About 53 minutes of it consist of physical action (including people sneaking around), leaving almost 70 minutes for other stuff: suspense, changing goals, surprise information, attention to parallel plotlines, and little moments like the thief pilfering candy just before an ambush.

The film typifies tidy classical Hollywood construction, beginning with an arrival (the jet) and ending with a departure (the McClanes in a limo). In between we get a big dose of the classic double plotline, romance and work. Holly’s job at Nakatomi threatens their marriage, and John takes on a temp job, that of fighting the gang, which also endangers the couple’s efforts to reconcile.

For every Superman, there’s a Kryptonite, and here the protagonist’s flaws include his fear of heights (set up in the second shot, reiterated throughout) and, more importantly, his resistance to Holly’s independence. By the end, he’s learned a lesson. The film’s streak of male sentimentality allows John to ask his wife’s forgiveness for blocking her career ambition. She’s ready to compromise too, reassuming his last name when she meets Al. The characters we care about change, at least a little. That could be the motto of most classical Hollywood plots.

As usual, we get crosscutting among several lines of action. John’s arrival is crosscut with Holly at work fending off Ellis, and in the rest of the film the gang’s stratagems are intercut with the cops’ plans and McClane’s efforts. At various points, five or six actions are alternating with one another.

All these escalating situations cluster into distinct parts, the four that Kristin has argued for as typical of Hollywood architecture.

The Setup runs about 33 minutes, culminating in the murder of Takagi and Hans’s promise that he can open the vault.

The Complicating Action, a counter-setup, coalesces around John’s goals of communicating with outsiders, avoiding capture, and attacking the thieves when he can. Through many chases and fights, the gang seeks to block all these efforts. The lines converge when John shoots Marco and tosses his body onto Al’s car. He gains the bag with the detonators, giving him the upper hand. Then the TV reporter gets involved, the cops arrive, and John is ordered to wait. Things seem to be stabilized.

After this midpoint, the Development supplies what Kristin calls “action, suspense, and delay.” Officer Dwayne Robinson arrives, pitting himself against Al and McClane. We can regard the police assault, Ellis’s clumsy attempt to broker a deal, and the arrival of the FBI men as a series of delays that endanger the stability of the standoff. At the end of this section, John meets Hans (posing as an escaped hostage): now both men know each other. And in the firefight that follows, John loses the detonators. Hans declares, “We’re back in business,” and the original plan can go forward.

The last twenty-five minutes constitute the Climax, launched by McClane’s “darkest moment.” He seems utterly beaten. Picking glass shards out of his feet, he gives Al a message for Holly over the CB radio. Al tells of his own burden, the accidental shooting of a child. The stakes are now very high.

Rapid crosscutting shows John finding the bombs on the roof and fighting with Karl, while the FBI helicopter attacks the building and Hans discovers that Holly is John’s wife. John stampedes the hostages down the stairs off the roof and escapes the strafing from the chopper before it blows. Argyle dispatches Theo, while John finds the surviving gang members in the atrium and shoots Hans, who falls to his death.

In the Epilogue, Al and John meet, Al dispatches Karl, Holly socks the newsman, and John and Holly drive off with Argyle.

These parts present a tight, logically building plot composed of swiftly changing situations. Along the way we encounter a great many motifs that create echoes or contrasts. Everyone notices the Rolex, at first a symbol of Holly’s talents but also of corporate swagger; only by unfastening it can they let Hans drop from the window. When Argyle floats the possibility that Holly will rush back into John’s arms for a movie ending, John murmurs: “I can live with that.” Agent Johnson speaks the same line, but for him it means an acceptable level of civilian casualties.

Holly’s unmarried name, Gennero, shows how a motif can develop in relation to the drama. At first it’s a sign of pride in her own identity (typical corporation, Nakatomi has misspelled it on the touch screen). Her name-change triggers the couple’s quarrel, but it has another narrative use: It conceals John’s identity from Hans. And at the end he introduces her to Al as Gennero but she reasserts her love by correcting him: “Holly McClane.”

Then there are differences of class and country. Hans reads Forbes, but McClane the US boomer references Roy Rogers and Jeopardy. (Hans is so unplugged from pop culture he thinks John Wayne was in High Noon.) Argyle the former cab driver and Al the cop know the downside of city life, but so does John the New York detective, who adapts Roy’s trademark phrase to the mean streets: “Yippee-ki-yay, motherfucker.”

Even a conventional Hollywood gesture, that of attacking a picture of a loved one, acquires a nifty plot function. Annoyed at John, Holly slaps down the family portrait on her shelf. Good thing too, because otherwise Hans would have seen it during the invasion. We’re reminded of that picture when in a moment of quiet John looks at the same snapshot in his wallet. Only after Hans has encountered John is he able to flip the portrait back up and realize that Holly is the “someone you do care about.”

There are lots more felicities like these–so many that I’d consider Die Hard a “hyperclassical film,” a movie that’s more classically constructed than it needs to be. It spills out all these links and echoes in a fever of virtuosity. Hard to believe that the makers started shooting without a finished script.

Intensified continuity, personalized

Die Hard is a good example of a stylistic approach I’ve called “intensified continuity.” It’s a modification of the classical method of staging, shooting, and cutting scenes. Here director John McTiernan and DP Jan de Bont tweak that approach in distinctive and powerful ways. You can find examples all the way through the movie, but I’ll draw most of my illustrations from the first hour, when the stylistic premises get laid out for us.

Cutting speeds accelerated sharply in Hollywood films from the 1960s onward, and for its time, Die Hard was a rapidly-cut movie. The average shot runs just under five seconds, about what you’d get in a 1920s silent film. By today’s standards, which fall more in the 3-4 second range (even for movies outside the action genre), it’s a bit sedate.

One factor that increases the cutting pace is a greater reliance on singles and close-ups. These are tighter than we’d expect in most studio films of the classic era.

Even in close-up, the shots aren’t snipped free of their surroundings, thanks to the wide frame and layers of focus–both important in the film’s overall style, as we’ll see.

Likewise, intensified continuity exploits a greater range of lens lengths than we’d find in studio films of the classic era. We get wide-angle shots like those above along with telephoto shots throughout. Here the long lens is used to pile up people around Holly, and an even longer lens shows her optical viewpoint on the bandits in the office.

And there’s a free-roaming camera, thanks chiefly to Steadicam technology. But interestingly, Die Hard avoids some of today’s most common camera movements, such as shooting a fixed conversation with a sidewise or circular tracking shot. These would become more common in the 1990s.

McTiernan thought a lot about his camera movements, as he explains in interviews and the commentary track on the DVD. He wanted to shape spectators’ attention, to use camera movement to nudge things into view. “The audience’s eye wants to go with you.” Accordingly, more than in many contemporary films, Die Hard‘s camera movements have a shape: they end on a point of information.

Sometimes it’s just a quick pan, doing duty for a cut. At other times, the reframing is a gentle nudge that prepares for a new scenic element, as when Holly enters her office.

In shooting Predator (1987), McTiernan wanted to cut moving shots together, but his editor resisted. For Die Hard, he refilmed his camera movements at different rates so that two would match. A good example is when Karl’s brother strides carefully into an area under construction. The camera tracks with him, but when he turns to find the source of a whining noise, the arcing movement at the end of one shot is picked up in the next as the framing circles to reveal the saw.

That reveal is given, characteristically, in rack focus. I could have added rack focus as another featured technique of intensified continuity. McTiernan and de Bont take it very far, making Die Hard one of the great rack-focus movies. The image is constantly shifting focus to guide our attention to the changing layers of the scene.

This neat, compact presentation not only preserves the commitment to long-lens close-ups we find in intensified continuity. The technique also gives each rack focus the snapping force of a cut. (And you don’t need to build big sets.) Needless to say, the rack-focusing wouldn’t work if McTiernan hadn’t committed himself to staging his action in depth. More on this below.

Staging in ‘Scope

Die Hard finds ingenious ways to “let the audience’s eye go with you” in the widescreen format. Sometimes it’s a matter of classic edge framing. Thanks to a low angle, John and Holly converse along a wide-angle diagonal.

Sometimes McTiernan reverts to a technique not enough directors use nowadays: blocking and revealing. In classic cinema that was usually a technique reserved for long shots, when actors could move aside as part of ensemble. Die Hard applies blocking and revealing to the tight framings of intensified continuity.

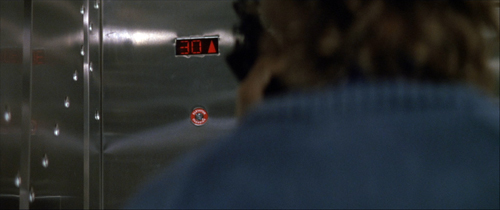

A thug in an elevator checks his weapon, pivots for an instant, and then moves aside to show the elevator arriving at the target floor.

Here again a rack focus helps. The moment reiterates the importance of the thirtieth floor in the skyscraper’s geography.

When Hans finds the body of Karl’s brother, we can study his expression. He flips the victim’s head to reveal a gunman, who looks to Hans before he says his line.

In a neat touch, the thug’s mouth isn’t shown. Today a director would probably show his whole face, but, really, who cares? The careful framing keeps him a secondary character, and a future target of McClane. And no need to rack focus on him, which would give him unwonted importance. All we need to remember him is that he’s the thug with long hair.

I can’t refrain from using one audacious example from late in the film. John and Hans have met, and Hans has revealed himself by targeting John with the pistol McClane has given him. In reverse shot, John reveals that it has no bullets and grabs it away from Hans.

But the pistol, and that gesture, have concealed the elevator behind them. When the pistol is knocked down, the elevator light pops on in the background. Our attention snaps to it, aided by that characteristic ping we hear throughout the movie (another motif).

The crisp turn of events, given visually and sonically, gets ampified by the acting. McClane’s cockiness turns to panic and Hans gets the upper hand. (“Think I’m fucking stupid, Hans?” Ping. “You vere saying?”)

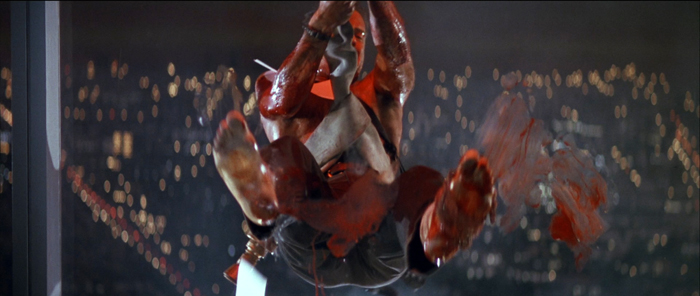

The most bravura rack-focus comes during the climax, when the firehose reel whizzes down behind McClane and he realizes that he’s being dragged through the shattered window.

The coordination of the long lens, camera movement, staging, and racking focus is especially rich when Hans drifts among the hostages searching for the man in charge. He recites Takagi’s life history as he passes from one possibility to another (including, comically, Ellis).

At the climax of the passage, McTiernan’s staging-in-layers sets up Takagi, Karl, and Holly before Takagi takes charge. Briefly blocked by Hans, he admits his identity by stepping out from behind and into focus.

McTiernan isn’t done. A reverse shot of Hans finishing his spiel (“…and father of five”) punctuates the suspense. McTiernan buttons up this passage by returning to his “moving master” shot and having Karl shove Takagi out.

That clears the way for us to see Holly’s reaction. A beat dwells on her as she shifts her eyes to Hans, foreshadowing her conflict with him at the climax.

This sort of layering of faces popping in and out of visibility has precedents in earlier cinema, chiefly of the “tableau” period of the 1910s. McTiernan has, I think, spontaneously rediscovered for modern times what William C. de Mille was up to in the party scene in The Heir to the Hoorah (1916). (For more on that, go here.)

Of course McTiernan also has to work with the 2.35:1 anamorphic format, which enables him to spread his layers out more. That format also allows some remarkable compositions, such as the one surmounting today’s entry. The cut to the shot of John in Holly’s office uses the abstract splash painting (seen here for the first time) as a visual analogy for the explosion of gunfire offscreen at the same time.

McTiernan and de Bont constantly find striking but cogent images, thanks to lighting as well as color and format. Here’s McClane on top of an elevator peering through the perforated grille; his POV is a striking but still informative composition. the cut between the two provides a little punch of contrasting light and shade.

There are felicities like these feathered all through this remarkable movie, but the momentum of storytelling never flags. This remains a masterpiece of Hollywood filmmaking.

Thanks to our readers for following us this year. Kristin will be weighing in soon with her annual list of best films from ninety years ago. In the meantime, HO-HO-HO.

Madison owes an enormous debt to our Cinematheque team: programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, Ben Reiser, and Zach Zahos, as well as veteran projectionist Roch Gersbach. Santa should reward them. You can too by visiting the Cinematheque’s Podcast, Cinematalk. There you’ll find conversations with Manohla Dargis, Schawn Belston, and James Runde.

For lots of background on the making of this film and the four sequels, there’s Die Hard: The Ultimate Visual History by Ronald Mottram and David S. Cohen. At rogerebert.com, Matt Zoller Seitz has a discerning appreciation on the occasion of the film’s twenty-fifth anniversary.

Jake Tapper has provided the definitive analysis of Die Hard as a bona fide Christmas movie.

McTiernan (with whom I share an alma mater) provides very good DVD commentaries (even for Basic). Prison also seems to have given him some pronounced political views. Alas, the website he created as a platform for them is apparently no longer available. Word is that McTiernan is preparing a new film, Tau Ceti 4, with Uma Thurman. A videogame promo is purportedly signed by him.

Of other McTiernan films, I also much admire The Hunt for Red October (1990). The Thomas Crown Affair (1999) seems to me better directed than the original, and The 13th Warrior (1999), despite being taken out of his hands, remains a pretty interesting film. (Name another Hollywood movie in which a Muslim poet visiting Northern Europe is justly appalled at its barbarism.) Nomads (1986) also has its good points.

I discuss the issues of narrative and style raised here at greater length in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. You can also search “intensified continuity” for blog entries hereabouts. On CinemaScope aesthetics, see this entry and this video.

Die Hard (1988).

Cognitive film studies: The Hamburg Variations

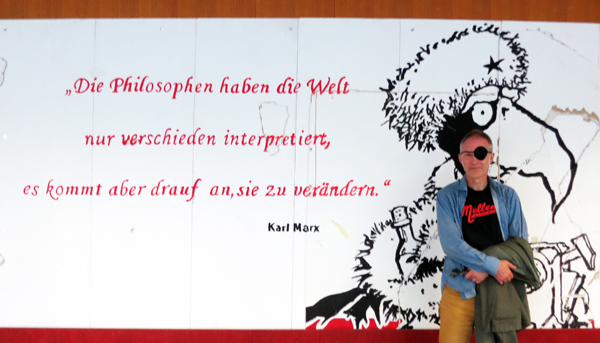

Lobby, Von-Melle-Park 9, Universität Hamburg, with Murray Smith.

DB here:

How many universities in the US would post a big quotation from Karl Marx in the lobby of a classroom building? (Answer: None.) But a cartoonish rendition of Marx’s killer app–the task of philosophy being not only to understand the world but also to change it–greeted the one hundred or so scholars attending the latest conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image last week at the Universität Hamburg.

How much we’ll change the world remains to be seen. What is clear now is that thanks to the superb organization of Kathrin Fahlenbach, Maike S. Reinerth, and their team, the SCSMI had a lively four days of papers, discussions, and excursions–as well as a screening of a strong film by a skillful director previously unknown to me. In all, every good reason to go to a conference.

Big questions, candidate answers

Carl Plantinga, Dirk Eitzen, and Kathrin Fahlenbach on the Hamburg Harbor cruise.

The range was huge, as usual, because this is a very diverse group. Our community, as I’ve mentioned in earlier reports, hosts film scholars, scholars of other media (television, games, internet), psychologists, and philosophers. Recurring questions include: How do viewers comprehend media presentations? What is the role of morality in film and television? How do practitioners conceive their craft? How do media present and trigger emotions? What appeals are specific to certain genres or historical periods? Not least: How may we construct good theories to answer such questions?

Three sessions ran simultaneously at each time slot, so I missed many good presentations. Kristin and I occasionally doubled up. Many of the talks will eventually become published papers, several in the Society’s journal Projections, so let me just highlight a few strands.

For those of us interested in how style interacts with narrative, there were several significant presentations. James Cutting, who has pioneered the use of Big Data techniques in scanning large batches of films, provided a compact account of how “sequences” (as opposed to scenes) displayed patterns of coherence and grouping. Karen Pearlman discussed her films, and James examined them to reveal fractal patterns in their rhythms–patterns that match the dynamics of footsteps, heartbeats, and breathing.

Two papers added to our understanding of the Kuleshov effect, much discussed on this site. Marta Calbi and her collaborators conducted EEG testing on spectators exposed to a Kuleshovian film scene, while Anna Kolesnikov, another member of the team, traced the contradictory versions of the “experiments” that Kuleshov and his students purportedly constructed. Both were exciting contributions to our understanding of Kuleshov’s legacy, which as the years go by looks more complex than we had thought.

Other papers on visual style included Barbara Flückiger’s tour of the staggering resource she and her colleagues have devoted to the history of color in film–a database of images from 400 films illustrating a range of technologies, periods, and genres. She has also mounted a magnificent array of tools for detailed analysis of color. (Significantly, she has taken the images from film prints, not video copies.) Here’s one of several stunning images she has taken from Helmut Käutner’s Grosse Freiheit Nr. 7 (1944, Agfa nitrate).

Stephen Prince, whose book Digital Cinema has just been published, surveyed the emergence of “deep fakes,” manipulated images that have no basis in reality but which are indiscernible from an accurate image. Steve was once skeptical that digital images would ever cut us off entirely from photographic reality, but now machine learning has managed to do it. Sped up by social media, the rise of unverifiable “records” creates what he called “an attack on an information system we call society.”

Hitchcock, everybody’s idea of a shrewd filmmaker (when will cognitivists discover Lang?), came in for his usual close treatment. Todd Berliner proposed five ways in which story information can be set up and paid off in a narrative, and he used Psycho as an instance of at least four of those methods. Maria Belodubrovskaya countered Hitchcock’s constant claim that he relied on suspense and not surprise. She showed that both single sequences and overall plots (e.g., Suspicion, Psycho) were heavily dependent on surprise effects.

In the first day, the range of the “humanistic” side of SCSMI was on vivid display. Malcolm Turvey asked whether the give and take of philosophers’ arguments converged on a consensus about truth, the way that much of science progresses. To illustrate the process, he considered the return of an “illusion” theory of images put forth by Robert Hopkins. Later that day, Jeff Smith used the cognitive theory of confirmation bias to show how characters in Spike Lee’s Clockers systematically misunderstand the story situation. The result, enhanced by genre conventions and a violation of some traditions of the detective story, enmeshes the viewer in the same error.

On the other end of the spectrum, there were papers mobilizing empirical research. Timothy Justus drew upon Lisa Feldman’s work in How Emotions Are Made to suggest that a biocultural account of facial expression should not rely too strongly on Paul Ekman’s classic argument about universal, basic expressions. More room, Justus proposed, should be given to cultural forces that build “emotion concepts” that filmmakers and viewers draw on.

A more hands-on empirical project was that coming from a team at Aarhus university. Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen posed the question: What if sympathy for a film’s villain varies with the personality of the spectator? As he put it, “If you are like a villain, will you like a villain?” So via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk the team ran questionnaires testing how personality types matched tastes in villains. Not to spoil their public announcement, I’ll just say that the results seem to confirm the belief that the most dangerous creatures on earth are young human males.

There was a lot more here than I can report, including provocative keynote addresses from Professors Anne Bartsch and Cornelia Müller (presenting work done with Hermann Kappelhoff). There was also a moving tribute to Torben Grodal, a central force in SCSMI and a leading-edge theorist applying evolutionary psychology and embodiment theory to traditional genre studies.

And, since SCSMI wants to understand how creators create, there was a film and its maker.

Without bullshit

In the past, our conferences have featured Lars von Trier and Béla Tarr, talking with us about their work. This time the guest was Thomas Arslan, a prominent “Berlin-school” director, who brought his 2010 film In the Shadows (Im Schatten) to the lovely Cinema Metropolis.

The film is a dry, hard-edged crime exercise. Trojan, fresh out of prison, comes to his boss to claim his share of the loot. In a tense confrontation he manages to get some of what he’s owed, but he’s now a target for elimination. He searches for a new robbery scheme and settles on the heist of an armored car. As usual, things don’t go as planned, particularly due to the intervention of a crooked cop.

Shot in a laconic style, In the Shadows took advantage of the Red One camera to produce remarkable depth in dark surroundings. (We saw it as a print because in 2010 theatres weren’t quite ready to show digital files. The print looked fine.) The drab locations complemented the anti-psychological impact of the story. Characters barely speak, the music is spare and almost subliminal, and the framing doesn’t accentuate the action expressively. In his post-film discussion, Arslan explained that the style grew out of the small budget and the rapid schedule. The result was a sort of modern B-film, avoiding the excess of CinemaScope and explosive chase sequences.

Arslan refuses to glamorize his gangsters, but he summons up sympathy for Trojan by minimal means. The protagonist is a solid, efficient professional, and he’s loyal to his boss until he realizes he’ll be betrayed. And as Hollywood screenwriters would remind us, you can sympathize with someone who’s been treated unfairly. I liked the unfussy handling of the story; it was a bit reminiscent of Rudolf Thome’s bare-bones Detective (1968). Arslan would be a good director to shoot a Richard Stark noir. “He does it without bullshit,” Arslan said of his thieving protagonist. It’s a good description of Arslan’s own technique.

SCSMI continues its tradition of merging humanistic inquiry with findings from empirical science. We can fruitfully ask questions that cut across traditional boundaries if we ground those questions in clear concepts and solid evidence. Our gathering next year moves back to the States–Grand Rapids, no less. More fun on the way.

Go here for earlier years’ coverage of SCSMI conferences.

On Richard Stark noir novels, see here and here. In the Shadows would fit nicely into my discussion of conventions of the heist film.

My own SCSMI contributions were two: a tribute to Torben Grodal and a little talk on contemporary women’s domestic thrillers (Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, etc.). I may post the latter as a video lecture later this summer.

James Cutting lecturing at the SCSMI conference.