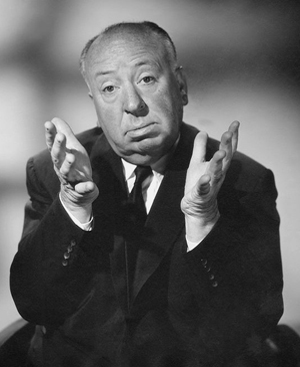

Hitchcock, Lessing, and the bomb under the table

Friday | November 29, 2013 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

Every good cinephile knows Alfred Hitchcock’s famous distinction between suspense and surprise. In articles and interviews from the 1930s on, he explained that situations are more gripping if the audience has more knowledge than the characters do. His classic example, in conversation with Truffaut, was a bomb under a table.

We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let us suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, “Boom!” There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but priot to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware that the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock, and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions this innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: “You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There’s a bomb beneath you and it’s about to explode!”

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second case we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense.

In Film Art, we invoke Hitchcock’s example to illuminate how narration can be more or less restricted. You can confine the narration to what only a character knows, or you can expand it to give the viewer story information that a character doesn’t have. By widening the audience’s knowledge somewhat, you can build suspense; by confining it, you can make the audience share the character’s surprise.

After Hitchcock came to the United States, he often invoked this distinction in interviews, and it became part of craft lore among writers of screenplays and genre fiction. I trace the idea’s fortunes a little in the online essay, “Murder Culture.” In practice, though, Hitchcock didn’t always follow through. Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941) confine our knowledge very closely to the protagonist’s, without providing that wider perspective he advocates in his remarks to Truffaut. And surprise is central to some Hitchcock works, notably Psycho.

In other films, of course, he did follow his own advice. When Johnny Jones detours to the Tower of London in Foreign Correspondent, we know that the little man steering him there intends to kill him. Shadow of a Doubt lets us see Uncle Charlie in a sinister light before he visits Santa Rosa, and glimpses of his behavior strongly hint that he will menace Young Charlie when she starts to investigate him. And of course The Greatest Film Ever Made (or is it?) tips us off to what’s really going on with Madeleine/ Judy before poor Scottie grasps it.

I’ve wondered: Is this suspense/surprise distinction original with Hitchcock? In the tapes of the original interview with Truffaut, he notes: “You know, there has always been this dispute between suspense and surprise. . . . What I’m saying is not new, I’ve said this many times before.” He then launches into a more expansive account of the bomb-table scenario.

His formulation is ambiguous. Is the distinction “not new” because it’s been around a long while (“always”), or because he’s reiterated it many times? And is his preference for suspense an uncommon opinion? Exact answers may lie in the vast Hitchcock literature, but so far I haven’t found them. Here’s what I came up with.

What enduring disquietude

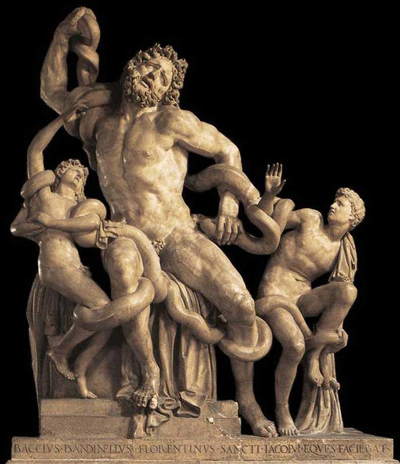

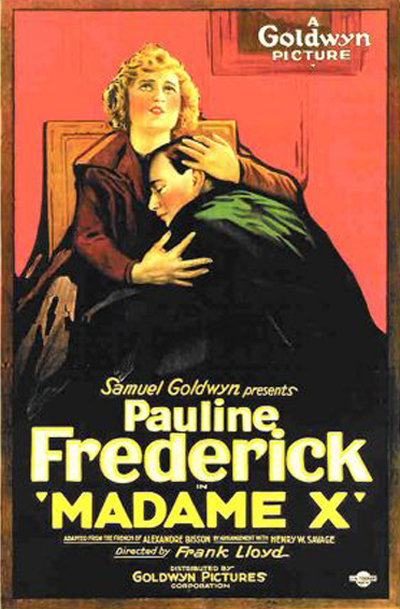

Gotthold Ephriam Lessing was a playwright and drama theorist. His Miss Sarah Sampson (1755) is sometimes considered the first “bourgeois tragedy” in German, and his best-known play is perhaps Nathan the Wise (1779), a classic that was made into a notable silent film. Lessing is also famous for his influential book-length essay Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (1766), which has been a center of debate in aesthetics ever since.

In that piece he argued for a fundamental distinction between time-based arts (drama, literature) and arts of space (painting, sculpture). From that distinction Lessing inferred a principle of decorum, or expressive fitness, for different media. He claimed that the famous sculpture showing Laocoön and his sons caught in the serpent’s coils could express only a split-second of pain, not the extended agony of their struggle. As a three-dimensional image, the father’s scream is vivid, but it lacks “all the intermediate stages of emotion” that a poem could have rendered as it unfolded in time. The great film theorist Rudolf Arnheim argued that the sound film obliges us to ask whether moving images and recorded dialogue cover different expressive territories, so he called his essay “The New Laocoön.”

Lessing also ruminated on the drama, and his thoughts about playwriting, set down in notes written between 1767 and 1769, contain many intriguing observations. In one passage, he replies to writers who have criticized ancient Greek playwrights for giving away too much in their prologues. These critics have implied that audiences would be more satisfied if big events took them by surprise. So, says Lessing mockingly, let’s simply reedit the plays and chop out all the information that sets up the final reversals.

His serious point is that a surprise yields only a transitory thrill. In the passage below, he uses “poet” and “poem” in a general sense, including storytellers and dramatists, plays and prose fiction.

For one instance where it is useful to conceal from the spectator an important event until it has taken place there are ten and more where interest demands the very contrary. By means of secrecy a poet effects a short surprise, but in what enduring disquietude could he have maintained us if he had made no secret about it! Whoever is struck down in a moment, I can only pity for a moment. But how if I expect the blow, how if I see the storm brewing and threatening for some time about my head or his?. . .

[By not preparing the spectator] the whole poem becomes a collection of little artistic tricks by means of which we effect nothing more than a short surprise. If on the contrary everything that concerns the personages is known, I see in this knowledge the source of the most violent emotions.

Lessing is evidently thinking of classic cases of recognition, plot twists that reveal connections among characters that they were long unaware of. (Oedipus is actually the son of the man he killed!) At another point, Lessing’s English translators find the word Hitchcock uses: “Our participation will be all the more lively and strong the longer and more confidently we have foreseen the issue.” “Foreseeing” here might be too strong, because in Hitchcock’s parable of the bomb we don’t really know the outcome. Will the men at the table escape in time, or halt the bomb, or be blown up? The inevitability of catastrophe that we expect in Greek tragedy produces a different sort of suspense than we experience in modern narratives. Yet it remains suspense nonetheless.

Lessing goes on to suggest that Aristotle valued Euripides most among dramatists not because of the plays’ gruesome endings but at least partly because “the author let the spectators foresee all the misfortunes that were to befall his personages, in order to gain their sympathy.” In other words, we have that sort of unrestricted narration we usually call omniscience. That’s what is at stake in Hitchcock’s bomb example.

Clairvoyant aloofness

It’s a long stretch from the late eighteenth century to Hitchcock’s time. Thanks to Google, and especially its wondrous Ngram software, we can get a rough sense of what happened to the duality of suspense and surprise in those intervening years.

A quick sampling shows that they were conjoined by the late nineteenth century. An anonymous 1884 critic finds that in Tennyson’s plays “the elements of suspense, of surprise, are altogether wanting.” In 1882, J. Brander Matthews, towering authority on theatre history, praises Hugo’s vibrant play Cromwell:

There is the familiar use of moments of surprise and suspense, and of stage-effects appealing to the eye and the ear. In the first act Richard Cromwell drops into the midst of the conspirators against his father,–surprise; he accuses them of treachery in drinking without him,–suspense; suddenly a trumpet sounds, and a crier orders open the doors of the tavern where all are sitting,–suspense again; when the doors are flung wide, we see the populace and a company of soldiers, and the criers on horseback, who reads a proclamation of a general fast, and commands the closing of all taverns,–surprise again. A somewhat similar scene of succeeding suspense and surprise is to be found in the fourth act.

Throughout this period writers fairly often counterpoised suspense and surprise as two essential strategies of plotting. But do the writers recognize the narrational implications they harbor, and do writers display Hitchcock’s preference for suspense? Yes to both.

George Pierce Baker, early twentieth-century drama macher, weighed in with his book Dramatic Technique (1919). He notes that in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I, a revelation of the Countess’s plan yields “a momentary sensation, surprise.” Baker reimagines two versions of the situation: When we know more than one of the antagonists does, and when we know more than both of them do.

Suppose we had been allowed to know the plans of the Countess, and they had seemed very dangerous for Talbot. Then, as she played with him, there would have been more suspense than in Shakespeare’s text, because an audience would have been wondering, not merely “What is the blow Talbot will strike?” but “Can any blow he will strike overcome the seemingly effective plans of the Countess?” Suppose we had been allowed to know the plans of both. Then, as we watched the Countess playing her scheme off against the plan of Talbot, of which she would be unaware, might there not easily be even more suspense? At every turn of their dialogue we should be wondering: “Why does not Talbot strike now? Can he save the situation, if he delays? With all this against him, can he save it in any case?”

Baker concludes that surprise enlivens the situation, but suspense allows for deeper characterization: awaiting an outcome, we must speculate on the characters’ temperaments, motives, and strategies.

Baker has already cited the Lessing passage I’ve mentioned, and he goes on to quote another authority of his period, William Archer. Archer’s Play-Making (1912) became something of a Bible for aspiring playwrights. (Preston Sturges swore by it.) Without explicitly mentioning suspense or surprise, Archer celebrates the pleasures of lording it over the characters.

The essential and abiding pleasure of the theatre lies in foreknowledge. In relation to the characters of the drama, the audience are as gods looking before and after. Sitting in the theatre, we taste, for a moment, the glory of omniscience. With vision unsealed, we watch the gropings of purblind mortals after happiness and smile at their stumblings, their blunders, their futile quests, their misplaced exultations, their groundless panics. To keep a secret from us is to reduce us to their level, and deprive us of our clairvoyant aloofness.

All of these drama theorists are promoting the well-made play as the best model for plot construction. They’re reacting against popular melodrama, with its episodic construction, wild coincidences, and startling twists–a model of what our colleague Lea Jacobs calls “situational” dramaturgy. The preference for suspense is a recognition of the playwright’s adroit shaping of the plot, preparing the later revelations carefully but also creating a steady arc of tension rather than a firecracker string of surprises. Suspense, it’s implied, is just more difficult to achieve than surprise, and a successful passage of suspense testifies to the writer’s skill.

In sum, by the time Hitchcock started his film career, the suspense/surprise couplet was fairly common in discussions of playwriting, and the superiority of suspense was more or less assumed. A 1922 essay concedes, “Whether or not surprise has a legitimate place in the drama is debated by commentators.” But the author, one Delmar Edmundson, suggests that an “entirely unexpected” turn of events in a one-act play can yield a valid thrill, just as in an O. Henry story. Still, the author suggests that even such a twist needs to be subtly prepared for.

In 1922 as well, Howard T. Dimick’s Modern Photoplay Writing: Its Craftsmanship devotes a whole chapter, “Suspense, Excitement, and Crisis,” to the need to make the viewer “participate” in the action. The melodrama Lady X, then recently adapted to film, affords an example. The attorney defending an older woman is in fact her son, though neither of them knows it. (Shades of ancient Greek theatre.) The result is double suspense: we, like the characters, worry about the outcome of the trial, but we also wonder whether they will discover their kinship. “Had the woman’s identity been kept from the spectators till the end and then ‘sprung’ with explosive suddenness, fully half the emotional effect would have been stripped from the play.” Lessing had already anticipated the power of situations of unknown identity: “None of the personages need know each other if only the spectator knows them all.”

At this point, I can’t say precisely how Hitchcock learned of the distinction between suspense and surprise. Clearly, though, the idea was circulating in the theatrical and cinematic milieu of his early career. It’s entirely possible that he read Archer, Dimick, or some comparable source.

In any event, the distinction isn’t original with him. He is, however, the person who made it central to conversations about filmic construction. Recall that he always denied making detective stories. As the Master of Suspense, he wanted to play down the startling solution to a mystery and instead emphasize slowly building tension. And his continuing reliance on the distinction reminds us that the man always in search of what he thought was “purely cinematic” owed a great deal to the theatre. Some critics complained about divulging Judy/ Madeleine’s secret partway through Vertigo, but here, as in most of his films, Hitchcock was adhering to lessons learned from the well-made play. The result was a “disquietude” that endures.

Hitchcock’s remarks appear in Truffaut, Hitchcock, p. 52 of my 1967 edition. There he somewhat qualifies his position about superior knowledge, adding at the end of the passage I’ve quoted: “The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. Except when the surprise is a twist, that is, when the unexpected ending is itself the highlight of the story.” I take it that this plot construction is different from that of a mystery plot, which poses questions explicitly (whodunit?). A twist ending, by contrast, catches us by surprise because we didn’t suspect that certain aspects of the situation were in question. Central examples would be Stage Fright, Psycho, and, more recently, The Sixth Sense.

Truffaut’s Hitchcock book (the first hardcover film book I ever owned, I think) is a considerable condensation of the extensive interview. The sessions, punctuated by sounds of cigars being lit and snacks being eaten, are preserved on tape. Thanks to the Internets, they are available here. Hitchcock’s slightly more elaborate version of the bomb scenario occurs in session 4, starting at 17:44.

You can read the books I’ve cited in free digital versions: Lessing’s Laocoon and his essays on theatre; J. Brander Matthews’ French Dramatists of the 19th Century; William Archer’s Play-Making; George Pierce Baker’s Dramatic Technique; and Howard T. Dimick’s Modern Photoplay Writing: Its Craftsmanship. Print editions are also available, of course. Other passages I’ve quoted come from Anon., “New Editions of Tennyson,” The Critic and Good Literature (15 March 1884), 123; and Delmar J. Edmundson, “Writing the One-Act Play VIII: Suspense and Preparation,” The Drama 12, 7 (April 1922), 258. Arnheim’s essay “The New Laocoön” is in Film as Art. For more on situational dramaturgy, see Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema (Oxford, 1998).

Thanks to Hitchcock adept Sidney Gottlieb for helpful advice on this entry. Anyone interested in Hitchcock needs to consult Sid’s excellent collections Hitchcock on Hitchcock and Alfred Hitchcock Interviews. The suspense/surprise duality recurs throughout them in varied forms.

Google’s Ngram software is here. It’s a tremendously useful tool for historical research.

I’d be grateful to anyone who can help pin down sources for Hitchcock’s acquaintance with the suspense/surprise couplet. As ever, feel free to correspond and I’ll update the entry as necessary.

P.S. 30 November 2013: Correspondence incoming! Richard Allen, NYU professor, lead guitarist, and Hitchcock expert, suggests in an email: “One suspects that the person who probably introduced Hitchcock to this was Eliot Stannard.” Stannard participated in writing all but one of Hitchcock’s all-silent films, and he published a short manual on screenplay technique, Writing Screen Plays (1920), derived from columns he published in Kine Weekly.

I haven’t been able to determine whether Stannard opined on the suspense/surprise duality, as the manual is extraordinarily rare, and the writing on Stannard that I’ve seen doesn’t explore this aspect of his work. Nonetheless I can recommend Charles Barr, English Hitchcock (Cameron & Hollis, 1999), 22-26; Barr’s article, “Writing Screen Plays: Stannard and Hitchcock,” in Young and Innocent? The Cinema in Britain, 1896-1930 (Exeter University Press, 2002), ed. Andrew Higson, 227-241; and especially Ian W. Macdonald’s chapter, “Hitchcock’s Forgotten Screenwriter: Eliot Stannard,” in his brand-new and enlightening Screenwriting Poetics and the Screen Idea (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 132-160. Further information on Stannard, or other sources of Hitchcock’s idea, remains welcome.

P.P.S. 2 December 2013: Ian Macdonald writes: “It’s very difficult, as you know, to trace the development of ideas such as the bomb in the briefcase/suspense-surprise thing. Stannard is surprising in that he clearly thought about how best to tell stories on screen, and came close to insights like Russian montage before those ideas became known in London (as Charles Barr has already pointed out). Unfortunately he did not continue to publish ideas after the early 20s, and his work is of course mixed up with ideas from everyone else in his ‘work group’. My picture of Stannard is built up from scraps, and his manual I have only seen in the British Library. This is tantalisingly aimed at the wannabe, so does not take ideas very far either. However, I’m sure he was aware of the prevailing doxa of play construction through such as William Archer, as others (like Brunel) were, and I’m sure that Hitch hoovered up Stannard’s ideas along with everyone else’s. As an inveterate theatre-goer, Hitch would also have been aware of ideas on suspense also. I will also have another look at my material specifically on this suspense question, for further clues, and let you know.” Thanks to Ian, Richard, and Sid Gottlieb for writing! More as things develop.

P.P.S. 5 December 2013: Oh, boy, have things developed. See the next entry.

P.P.P.S. 12 December 20113: Ashish Mehta has found evidence for the suspense-surprise duality in another eighteenth-century figure. He writes:

“Here’s what Samuel Johnson had to say in essay #3 of The Idler, published April 29, 1758, accessible here:

It has long been the complaint of those who frequent the theater, that all the dramatic art has been long exhausted, and that the vicissitudes of fortune, and accidents of life, have been shewn in every possible combination, till the first scene informs us of the last, and the play no sooner opens, than every auditor knows how it will conclude. When a conspiracy is formed in a tragedy, we guess by whom it will be detected ; when a letter is dropt in a comedy, we can tell by whom it will be found. Nothing is now left for the poet but character and sentiment, which are to make their way as they can, without the soft anxiety of suspense, or the enlivening agitation of surprise. (Emphasis added.)”

Thanks to Ashish for this!

Vertigo (1958).