Archive for the 'Narrative: Suspense' Category

Open secrets of classical storytelling: Narrative analysis 101

Premium Rush (David Koepp, 2012).

DB here:

After nine years, over 700 entries, and many essays and other stuff, this contraption of a website has started to intimidate us.

If we’re intimidated, you might be flabbergasted. Although a set of categories sits on the right to guide your exploration of this tangled databank, those too loom large and discouraging. So we’ve decided to tidy up by–how else?–adding another entry.

We’ll occasionally offer a stripped-down guide to our writing on certain topics. We’ll steer you to entries that we think represent the core of our thinking on a problem, and then add some that probe more deeply, for those who want to go beyond the basics. Since one of our areas is narrative theory and analysis, a good first effort, we thought, would be to produce a sort of DIY syllabus that systematically surveys the topic as we’ve explored it. And since we’ve often written about classical Hollywood storytelling, and since many of our readers are interested in that…well, the syllabus sort of wrote itself.

We call these ideas open secrets of storytelling because by and large they aren’t acknowledged in the screenplay manuals that aspiring writers read. In most cases, we’ve had to devise our own concepts and terms, based on watching hundreds of movies. Yet these observations are wide open, available in our books and on this site.

Now comes our chance to pull them together. The result isn’t an utterly comprehensive theory of classical Hollywood narrative, but it does give a fair sampling of the range of questions we’ve tried to answer about it. The topics, linked to essays and blog entries, are arranged in three layers.

The most basic layer is an array of key ideas about story worlds, plot structures, and strategies of narration. These ideas are introduced in the first entry, “Understanding film narrative: The trailer.” Discussions of other basic concepts follow. Just reading the entries pegged to those topics, you could get a solid sense of what we’re aiming at. For most of those, we also propose a film you might view to test how the ideas work.

At a second level, for some topics we include some entries that dig deeper. They’re either more complex and advanced, or they provide some historical background.

Finally, after we’ve reviewed the key topics, we add a batch of case studies that use several of the tools we’ve laid out. These are usually very deep dives into particular films. They aim to show how the analytical ideas can bring out distinctive features of particular movies. The case studies are pretty wide-ranging, but they tend to hover around specific problems, such as adaptation or the creation of fantasy worlds.

How could you use this resource? A teacher in high school or college could draw on it as a partial syllabus or just a thumbnail list of supplementary material for a course. Teachers using Film Art: An Introduction could treat it as a supplement to our section of Chapter 3 on classical narrative. Or a student might find an idea for a paper in this vicinity.

Since we’ve always tried to link film studies and filmmaking, we hope that practitioners might be interested too. For example, an aspiring screenwriter could take this as a weekly reading/viewing agenda, treating it as a free course in story analysis. General readers who simply want to know more about the mechanics of cinematic storytelling should find something provocative here too. For everybody: Feel free to use it as Narrative Analysis 101.

We thank our many loyal readers of this blog, as well as the many more who have just dropped by once or twice. Your continued interest has helped us keep going.

Open Secrets of Hollywood Storytelling

The basics

Understanding film narrative: The trailer. Suggested viewing: The Wolf of Wall Street.

Advanced: Three Dimensions of Film Narrative: Narration, plot structure, and story worlds. Suggested viewings: The Godfather, Jezebel.

Advanced: Stories beget stories. Suggested viewing: American Hustle.

Actions and agents

Introduction to classical plot structure. Suggested viewing: Many possibilities listed.

Historical background: Is there a 3-act structure?

Action films: Did spectacle kill classical plotting? Suggested viewing: Mission: Impossible 3.

Advanced: Block construction. Suggested viewing: Kill Bill, Pulp Fiction.

How many protagonists? Suggested viewing: The Big Short.

The importance of coincidence. Suggested viewing: Serendipity.

Narrative parallels among characters and periods. Suggested viewing: Julie and Julia, Enchantment.

Advanced: Fine-grained parallels between scenes. Suggested viewing: The Prestige.

Time shifts: How flashbacks work. Suggested viewing: The Power and the Glory.

Advanced: Time shifts without flashbacks. Suggested viewing: Exodus.

Advanced: Nested flashbacks. Suggested viewing: Passage to Marseille, The Locket.

Historical background: Flashbacks and plot problems. Suggested viewing: The Great Moment, All about Eve.

Replays. Suggested viewing: Mildred Pierce.

Advanced: The auditory replay. Suggested viewing: Sudden Fear.

Network narratives. Suggested viewing: Grand Hotel.

Forking-path plotting. Suggested viewing: Source Code.

Advanced: Film Futures. Suggested viewing: Sliding Doors.

Historical background: What-if narratives. Suggested viewing: Dangerous Corner

Beginnings and endings: Molly Wanted More. Suggested viewing: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, The Silence of the Lambs.

Telling more or less

Visual storytelling. Suggested viewing: Mission: Impossible.

The hook between scenes. Suggested viewing: Dr. Mabuse, The Gambler; National Treasure.

Narration: omniscient versus restricted. Suggested viewing: Cloverfield.

Historical background: Hitchcock, suspense, and surprise.

Alignment and allegiance. Suggested viewing: House by the River.

Character subjectivity, optical and mental. Suggested viewing: The Silence of the Lambs.

Historical background: Subjectivity and sound. Suggested viewing: Nightmare Alley, The Fallen Sparrow.

Voice-over narration. Suggested viewing: All about Eve.

Advanced: Dead narrators. Suggested viewing: Laura, Confidence.

Historical background: Inner monologue. Suggested viewing: Strange Interlude.

Case studies in narrative analysis

These are exercises in film criticism that utilize several of the tools laid out above.

Boyhood and Harry Potter: The actors’ lives as part of the narrative.

Eastern Promises: Thematic echoes in an auteur’s narratives.

Gone Girl: Suspense and thriller conventions in fiction and film.

Gravity: Narrative innovation within mainstream cinema.

Inception: Goals and parallel construction; managing multiple plotlines.

Moonrise Kingdom: How to make a modern fairy tale (with some help from merchandising); furnishing alternative worlds.

Premium Rush: How goals and deadlines create tight construction.

Side Effects and Safe Haven: Fragmentary flashbacks and patterns of suspense.

Slumdog Millionaire: Adapting a novel to classical norms.

The Bourne Ultimatum: Plotting across franchise installments.

The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Ghost Writer: Classical structure in genre fiction.

The Hobbit: Adaptation and length; adaptation and change.

The Magnificent Ambersons: How to manipulate time without flashbacks.

The Prestige: Using sound to enrich flashback construction.

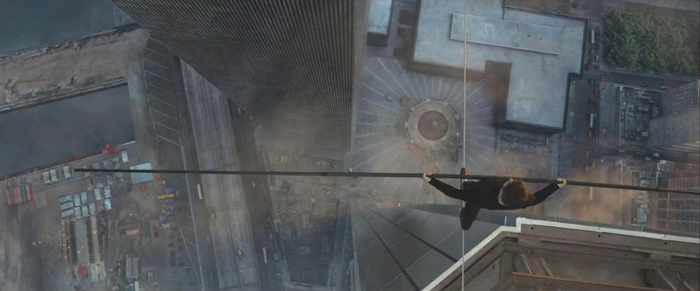

The Walk: Each act a different genre.

Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy: Elliptical narration: The viewer’s responsibility.

As we write more entries relevant to narrative, we’ll revisit this DIY syllabus.

Needless to say, we consider these matters more closely in several of our books. See The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, by Kristin, Janet Staiger, and me, and Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood and Storytelling in Film and Television. For my part, there’s Narration in the Fiction Film and The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. I’m at work on a book on narrative innovations in 1940s Hollywood, the central source of much that we encounter in today’s films.

Deadlier than the male (novelist)

DB here:

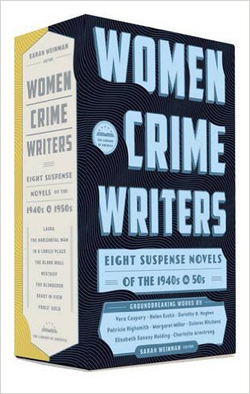

It’s about time! Sarah Weinman, editor of Troubled Daughters, Twisted Wives (already praised in these precincts) has brought out a two-volume set devoted to women crime writers of the 1940s and 1950s.

It’s not that these authors are utterly unknown. Popular in their day, some retained a following for a few decades, and Patricia Highsmith has become an enduring figure. Yet the never-ending frenzy for male-oriented noir in books and movies has led us to neglect what these writers and their peers accomplished. In the online essay “Murder Culture” I argued that we’ve probably overemphasized the hardboiled detectives and brutalized losers, and we’ve not paid enough attention to the accomplishments of other writers. The rise of the psychological thriller was central to 1940s popular culture.

Granted, it wasn’t only gynocentric. The thriller assumed exciting shapes in the hands of talented men like Patrick Hamilton, Cornell Woolrich and John Franklin Bardin. But the 1940s saw the emergence of a powerful cadre of women writers, many of whom started writing “pure” stories of detection but decided that suspense would be their forte. Surely they were encouraged by the success of Daphne du Maurier’s Rebecca, the best-selling mystery novel before Mickey Spillane came on the scene. But these suspense-mongers avoided mimicking Mignon Eberhart and other predecessors in the innocent-girl-in-a-spooky-house tradition. These new talents saw menace crouching behind the windows of drab houses and apartment blocks. Out of several tendencies I tried to sketch in that essay, they forged a tradition of what Weinman calls “domestic suspense.”

The Library of America volumes give us a fine occasion for appreciating what they accomplished.

Artisans of suspense

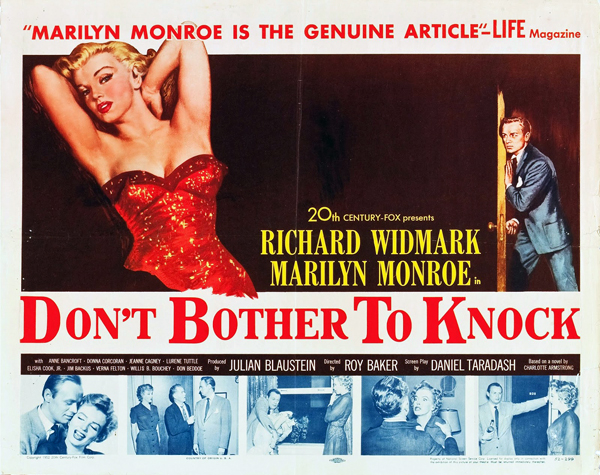

You might say that Double Indemnity and Out of the Past are quintessentially 1940s-1950s films, and I’d agree. But other important films were derived from works by women writers. The list of Highsmith adaptations, starting with Strangers on a Train (1951), is too long to recite here, but let’s remember that Charlotte Armstrong provided source novels for The Unsuspected (1947) and Don’t Bother to Knock (1952, from Mischief), as well as for Chabrol’s La Rupture (1970) and Merci pour le Chocolat (2000). Filmmakers produced now-classic versions of the Dorothy B. Hughes novels The Fallen Sparrow (1942), Ride the Pink Horse (1946), and In a Lonely Place (1950). The prolific but less famous Elizabeth Sanxay Holding gave us The Blank Wall (1947), adapted twice (The Reckless Moment, 1949, and The Deep End, 2001). Dolores Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold (1958) yielded the implausible basis for Godard’s Band à part (1964). Helen Eustis’s The Fool Killer (1954) became a 1965 film. And of course Vera Caspary’s Laura (1943) became a monument of studio moviemaking.

The thriller, you could argue, makes more engaging cinema than the straight detective story. Much as I admire cinematic sleuths like Sherlock Holmes, Nick Charles, Sam Spade, Philip Marlowe, and particularly Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto, pure mystery plots need a lot of bells and whistles to keep from being simply a matter of following the detective as he moves from place to place asking questions and dodging blows on the head. The 1940s tales of espionage, women in peril, serial killings, household anxieties, warped husbands and crazy wives and guileless governesses and all the rest have left a stronger legacy today. We live in the Age of the Thriller, as a glance at any bestseller list will indicate. The recent death of Ruth Rendell, arguably Highsmith’s only top-flight competitor, can only remind us of how the genre has flourished for decades.

As for the Library of America collection: You couldn’t much improve on Weinman’s selection, I think. All eight novels were appreciated in their day, and some won awards. A reader coming fresh to them will be surprised, I think, by the variety of treatment and the vigor of the writing. It’s to be hoped that encountering these will encourage readers to go on to other works by the same authors. In particular, I’d recommend Sanxay Holding’s The Death Wish (1934), a prefiguration of Highsmith’s dissection of male vulnerability; Margaret Millar’s Do Evil in Return (1950), which centers on a female doctor regretting not helping a woman obtain an abortion; Millar’s chilling The Fiend (1964); and of course almost anything by Dorothy B. Hughes, not least The Expendable Man (1963).

As for the Library of America collection: You couldn’t much improve on Weinman’s selection, I think. All eight novels were appreciated in their day, and some won awards. A reader coming fresh to them will be surprised, I think, by the variety of treatment and the vigor of the writing. It’s to be hoped that encountering these will encourage readers to go on to other works by the same authors. In particular, I’d recommend Sanxay Holding’s The Death Wish (1934), a prefiguration of Highsmith’s dissection of male vulnerability; Margaret Millar’s Do Evil in Return (1950), which centers on a female doctor regretting not helping a woman obtain an abortion; Millar’s chilling The Fiend (1964); and of course almost anything by Dorothy B. Hughes, not least The Expendable Man (1963).

The Library of America collection has rounded up several contemporary purveyors of suspense to write brief online appreciations of the titles in the collection. These are well worth reading. On each page further links take you to fresh material. There’s also a succinct introduction by Weinman. The print editions include her judicious career summaries, as well as notes on allusions and citations in each novel.

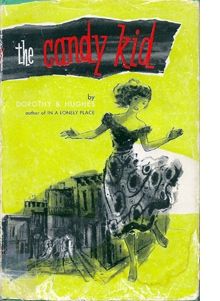

For readers interested in how women’s cultural roles are represented in fiction, these books provide a field day. Several of the professional commentaries suggest that the authors injected social criticism into their works. These writers are far more willing to get inside men’s heads than the hard-boiled boys are to think like a woman, so you can see the macho attitude in a new light. Here’s how Dorothy B. Hughes in The Candy Kid (1950, not in this collection) describes her hero:

Just as he was thinking that he’d better go in and buy a pack, wait for Beach in the air-cooled coffee shop, the girl came around the corner. She was tall, almost as tall as he, but he took a quick look at the pavement and saw that she was propped on heels. That made him feel more male.

Very often these writers take certain stereotypes, both male and female, and submit them to pressure through their craft. Others seem to accept those stereotypes and employ them for their own storytelling ends. Those ends are very much worth our attention.

We know that several of these writers were self-conscious artisans. Hughes and Armstrong wrote articles reflecting on mystery and suspense, while Hughes also wrote a sharp biography of Erle Stanley Gardner. Hughes also conducted a course on mystery writing at UCLA in the 1960s; she invited Vera Caspary in for a guest lecture, and Caspary’s advice makes for fascinating reading. Highsmith’s notebooks, preserved at the Archives littéraires in Switzerland, are filled with meditations on story problems, and she wrote as well a book-length manual, Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction (1966, 1981). I don’t think that any hard-boiled writers of the era have left such systematic reflections on the nuts and bolts of their work.

Once we pay attention to technique, we can see how these writers rework topics and concerns of the day. For example, we could talk a long time about how social roles induce women to assume a split identity: one face for friends and family, another that resists the masquerade. But these, after all, are mysteries, so that divided identity has to be dramatized—or better yet, played with and teased out for the sake of suspense and surprise. It’s remarkable that two of the books in the collection exploit the syndrome of Multiple Personality Disorder, which becomes part of the final surprise. Another, Laura, makes an enigma of the woman’s inner life by virtue of dispersed viewpoints.

If we want to learn about storytelling, we can usefully look at how writers manage traditional demands of craft. These books “say what they say” in and through technique—narrative form, literary style. The experience that results can be an enduring achievement.

Pronoun trouble

No use asking if the crime writer has anything of the criminal in him. He perpetuates little hoaxes, lies and crimes every time he writes a book.

Patricia Highsmith

Start with style—important in all storytelling, but posing some fascinating issues in the domestic thriller.

One problem faced by all these writers was: How to avoid the sentimental style of romantic suspense writers? Here’s a typical passage from Mignon G. Eberhart’s Another Woman’s House (1946).

She said, blindly choosing trite and inadequate words, “You cannot change your own sense of loyalty, of your own creed and code. It’s bred in your bone; it’s part of your body.”

He understood all the argument below it. He understood too that it was a fundamental argument in his own heart. His eyes deepened, searching her own. He said suddenly, “Myra, you must see this sensibly; you must be realistic and . . .”

“Oh, Richard, Richard!” She cried despairing, and put her head against his shoulder.

There’s some of this novelettishness in Armstrong, as in this bit from Mischief:

When a fresh scream rose up, out there in the other room in another world, Ruth’s fingertips did not leave off stroking into shape the little mouth that the wicked gag had left so queer and crooked.

Hughes and Hitchens, I think, leaned toward the hardboiled laconicism of Hammett and Cain, though without the slanginess. In The Horizontal Man, Eustis tries for a brittle, satiric tenor and some Hollywoodish banter between a reporter and a college woman. Highsmith was adamant in refusing what she called a “pulp” style. Hence her flat, spare simplicity. (Funny, though, since she started out writing comic books for the company that would become Marvel.)

Stylistic options can lie very far down. For years I’ve been curious about what fiction writers call their characters on first entrance. It’s a fundamental creative choice, and it’s absolutely forced: you have to call them something. And what you call them matters.

Here’s the beginning of Armstrong’s Mischief:

A Mr. Peter O. Jones, the editor and publisher of the Brennerton Star-Gazette, was standing in a bathroom in a hotel in New York City, scrubbing his nails. Through the open door, his wife, Ruth, saw his naked neck stiffen….

Cozy, our relation to this Mr. and Mrs. Jones: Mischief gives their first and last names. So far, no reason to be apprehensive. But here’s the start of Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold:

The first time they drove by the house Eddie was so scared he ducked his head down. Skip laughed at him.

Here a relationship is defined through laconic action: we’re on a first-name basis with the pair. It’s as if we’re riding in the back seat.  Compare the opening of Highsmith’s The Blunderer.

Compare the opening of Highsmith’s The Blunderer.

The man in the dark blue slacks and a forest green sportshirt waited impatiently in the line.

The girl in the ticket booth was stupid, he thought, never had been able to make change fast.

Highsmith is more ominous: No names, just a man as if seen from across the sidewalk. Yet we can’t say the presentation is “objective” because we’re given his annoyed thoughts about the ticket girl. So we are forced to ask: If I’m in his head, why don’t I know who he is? And why is he in a hurry?

And finally, the opening lines of Eustis’ The Horizontal Man:

The firelight played over all the decent, familiar objects of his everyday life; he viewed them desperately, looking for some symbol of succor. The firelight played on his rolling eyeballs, the careless tendrils of his black hair. “Oh now,” he said, “Oh now, I say, look here…” trying to summon a tone of commonplace to breast the tide of nightmare that was rising in that room.

Eustis dispenses with everything but he in describing something terrible going on. Not only do we not know who’s suffering, but we won’t know for some time. This, like the Highsmith, might be called “pronominal mystery”: not knowing anything about who’s in danger, we sense the danger as a pure force swallowing up trivialities of identity.

Most manuals of fiction-writing start by reviewing the bigger choices, like first- or third-person narration, but note that even within third-person storytelling, these passages bristle with different implications. Each of these openings puts us in a different relation to the characters picked out.

The storyteller makes a choice about how to name the actors in the scene, and that choice leads to others: the scene is built out the premises of what have launched it. Ruth, who studies her husband Peter at the mirror, will become one conduit of information within Mischief. Skip, who laughs at Eddie as they size up the home they’ll invade, will bully his partner throughout Fools’ Gold. The man in the slacks and sportshirt will drop out of The Blunderer for several chapters. So no need to name him yet; magnify the mystery. And the opening scene of The Horizontal Man will continue with personal but untagged pronouns—a she will be picked out too—as the full awfulness of the action emerges.

I suspect that the development of the suspense thriller in the 1940s sensitized writers to fine-grained choices like this. The verbal fabric became part of the suspense: not just what will happen next? but why is the action being presented in this way? This second layer of intrigue seldom occurs in the hardboiled detective novels. While Hammett, Chandler, and Ross Macdonald (married to Margaret Millar) slipped easily into first person and easygoing openings, these women writers were willing to try more oblique, tantalizing, and formally adventurous options. (Though we find them in Goodis, Woolrich et al. as well.) Without this newly cultivated sensitivity to names and non-names, proper nouns and pronouns, I doubt we would have the tour de force of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) and the shock of Hughes’ Expendable Man, or the brilliant opening of Ruth Rendell’s Wolf to the Slaughter (1967).

I suspect that the development of the suspense thriller in the 1940s sensitized writers to fine-grained choices like this. The verbal fabric became part of the suspense: not just what will happen next? but why is the action being presented in this way? This second layer of intrigue seldom occurs in the hardboiled detective novels. While Hammett, Chandler, and Ross Macdonald (married to Margaret Millar) slipped easily into first person and easygoing openings, these women writers were willing to try more oblique, tantalizing, and formally adventurous options. (Though we find them in Goodis, Woolrich et al. as well.) Without this newly cultivated sensitivity to names and non-names, proper nouns and pronouns, I doubt we would have the tour de force of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) and the shock of Hughes’ Expendable Man, or the brilliant opening of Ruth Rendell’s Wolf to the Slaughter (1967).

Fussy as these details are, they’re what I mean by craft. The verbal texture of any piece of fiction depends on dozens of such minute judgments. Just as in film every cut, camera movement, and actor’s glance matters, so does every word in a prose narrative. These writers understood that what we learn, syllable by syllable, can be a potent source of uncertainty and suspense.

Who sees and who knows?

The whole intricate question of method, in the craft of fiction, I take to be governed by the question of the point of view—the question of the relation in which the narrator stands to the story.

Percy Lubbock, The Craft of Fiction

In mystery fiction, management of point of view is critical. Not only will it weave the moment-by-moment verbal tissue, but it provides the large-scale parts that present the overall action. Where the Had-I-But-Known romance tends to be restricted to a single character, often through first-person narration, domestic suspense employs other options. It’s significant that of these eight novels, only one, Laura, employs first-person narration, and that in a distinctive way I’ll consider further along.

Unrestricted narration is a good strategy for maximizing suspense, as we see in Armstrong’s Mischief. A husband and wife leave their little girl with a babysitter in their hotel while they go off to an awards dinner. But the babysitter is one of those Crazy Ladies that the 40s produce in great profusion and the child is endangered.

Unrestricted narration is a good strategy for maximizing suspense, as we see in Armstrong’s Mischief. A husband and wife leave their little girl with a babysitter in their hotel while they go off to an awards dinner. But the babysitter is one of those Crazy Ladies that the 40s produce in great profusion and the child is endangered.

How to complicate this basic situation? Armstrong recruits a device—call it a narrative meme if you want—that emerges at the period: the eyewitness, typically in an urban setting, who glimpses possibly criminal doings and gets involved. This device finds its supreme filmic expression in Rear Window (1954), but it’s established in earlier films like Lady on a Train (1945), Shock (1946), and The Window (1949), and in the radio drama The Thing in the Window (1945), by Lucille Fletcher (another thriller queen, but of the airwaves). In Mischief, people in a building across the street from the hotel intervene in the doings of the babysitter, and the plot “intercuts” all their trajectories in order to create tension.

Hitchens’ Fools’ Gold similarly jumps from character to character, even within a single scene. This tale of a heist that is way above the skill sets of the thieves—a sort of humorless anticipation of an Elmore Leonard or Donald Westlake situation—uses unrestricted narration to build sympathy for the characters who are gulled into participating.

Central among these is Karen, pathetically happy that Skip is paying attention to her. One chapter starts with her meeting him after class, snuggling warmly into his arms (“Here was someone to whom she could confide the disaster with the coat”), before the narration switches brusquely to him:

Central among these is Karen, pathetically happy that Skip is paying attention to her. One chapter starts with her meeting him after class, snuggling warmly into his arms (“Here was someone to whom she could confide the disaster with the coat”), before the narration switches brusquely to him:

Skip listened, at first with indifference. He’d heard already from Eddie of Karen’s reaction to the money, her frightened excitement about it. It took a moment to realize that this wasn’t more of the same, the reaction of an inexperienced girl, but that a bad break had really occurred.

Throughout the chapter, this rather nineteenth-century version of omniscience will toggle between Karen and Skip, heightening the disparity between her lack of awareness and his harshness. “He was just having fun though she didn’t know it.” Arguably, a heist plot needs a certain wide-ranging narration (see The Asphalt Jungle), but Hitchens uses it to take us into the minds of all the characters, major and minor, and suggest both vulnerability and menace.

In a classic detective story, the identity of the culprit is concealed until the end. One Golden Age “rule” is that in the course of the action we must never be given the viewpoint of the killer. The rule was broken on occasion, notably in a certain novel by Agatha Christie, but it remained rather firm. In the thriller, by contrast, we can be in the killer’s mind, knowing full well that he or she is indeed the killer. A prototype is Patrick Hamilton’s Hangover Square (1941). Two books in this collection walk a line between detective story and thriller in this respect.

In Eustis’ The Horizontal Man, a popular professor has been murdered. The effects of his death ripple out across the campus, and the narration shifts among his colleagues, some students, and a reporter investigating the crime. In the midst of a corrosive satire of the academic life, we suspect that someone whose mind we have entered will turn out to be the culprit. So we have to probe the inner lives of the characters we encounter for psychological clues, not physical ones. The author must conceal the killer’s identity and “play fair,” in that what we learn at the end unexpectedly fits the characters’ stream-of-consciousness musings.

A similar problem confronts Margaret Millar in Beast in View. At the start the viewpoints aren’t quite so dispersed: initially, we shift between a woman plagued by threatening phone calls and an amateur investigator looking into the matter. As the mystery deepens, however, the range of knowledge spreads and we get “lateral” viewpoints on the central situation. This is partly to deflect us from the grim revelation that we have been quite thoroughly misled.

A similar problem confronts Margaret Millar in Beast in View. At the start the viewpoints aren’t quite so dispersed: initially, we shift between a woman plagued by threatening phone calls and an amateur investigator looking into the matter. As the mystery deepens, however, the range of knowledge spreads and we get “lateral” viewpoints on the central situation. This is partly to deflect us from the grim revelation that we have been quite thoroughly misled.

It is a pity that this edition didn’t include Millar’s 1983 Introduction and Afterward. The latter explains the origin of the book’s device, while the Introduction reports the effects the book had:

I was threatened with a libel suit, informed by a patient in a mental institution that at last she had found someone who really understood her, invited to join a coven of witches, asked to address a meeting of psychiatric social workers, and presented with the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Allan Poe award for best mystery of the year.

At the other extreme, two of these novels focus on extremely restricted viewpoints. Hughes’ In a Lonely Place is wholly locked within the mind of a hypermasculine ex-Air Force pilot who trails and murders women. Hughes gives us the pronominal tease: it’s he for the first five pages until, when he places a phone call, we learn he’s called Dix Steele. In a cat-and-mouse game reminiscent of films like Woman in the Window and Where the Sidewalk Ends, the killer gets close to the murder investigation. Dix’s army buddy is the chief cop on the case, so Dix can monitor things and even drop in on crime scenes. Strikingly, Hughes puts the killings “off-page.” This admirably eliminates any Spillane-ish sensationalism while keeping the focus wholly on the way Dix loses control of his masquerade. He’s worn away in a series of confrontations with two women who see, as no man can, something deeply wrong in him.

Closest to the traditional woman-in-peril plot is Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall. While her husband is away in the service, a middle-class housewife learns that her daughter has been seduced by a sleazy opportunist. The wife soon becomes the target of two blackmailers, one of whom grows to love her. Gifted with a pair of obnoxious and ungrateful children and an amiably oblivious father, the heroine is doubly trapped—within a confining household and a crime cover-up. We’re limited to her range of knowledge, so every encounter is charged with uncertainty about the motives of others. She can’t confide in her husband and so must write bland letters to him reporting that everything is just fine.

Closest to the traditional woman-in-peril plot is Sanxay Holding’s The Blank Wall. While her husband is away in the service, a middle-class housewife learns that her daughter has been seduced by a sleazy opportunist. The wife soon becomes the target of two blackmailers, one of whom grows to love her. Gifted with a pair of obnoxious and ungrateful children and an amiably oblivious father, the heroine is doubly trapped—within a confining household and a crime cover-up. We’re limited to her range of knowledge, so every encounter is charged with uncertainty about the motives of others. She can’t confide in her husband and so must write bland letters to him reporting that everything is just fine.

As you’d expect, Highsmith tries something more intricate in The Blunderer. Here we have two protagonists, each man given his own viewpoint. But after an opening introducing us to one man’s crime (in a scene that spares no violent detail), he drops out of the action for a hundred pages. We concentrate instead on the polished professional lawyer whose life unravels when his domestic skirmishes—nearly all petty and drab—come to a head. As with most Highsmith men, he is tempted to do something very trivial and very stupid, almost out of intellectual curiosity. Highsmith policemen take a dim view of such enacted thought experiments.

As the two protagonists’ worlds converge, we get the characteristic Highsmith themes of self-possessed men losing their nerve, the traps of respectable life, the risk of impulsive action, the ways in which friends turn away from you when they suspect you of lying. The lawyer is called by his first name, Walter, while his counterpart is known to us by his last name, Kimmel. In such subtle ways does an author align us a little more closely with one character than another. Both, though, are blunderers.

I should add that all the markers of 1940s fiction and film—dreams, hallucinations, false fronts, unstable families, untrustworthy lovers, socially adroit psychopaths—are woven into these novels with great skill. What more could you ask?

A frenzy of recapitulation

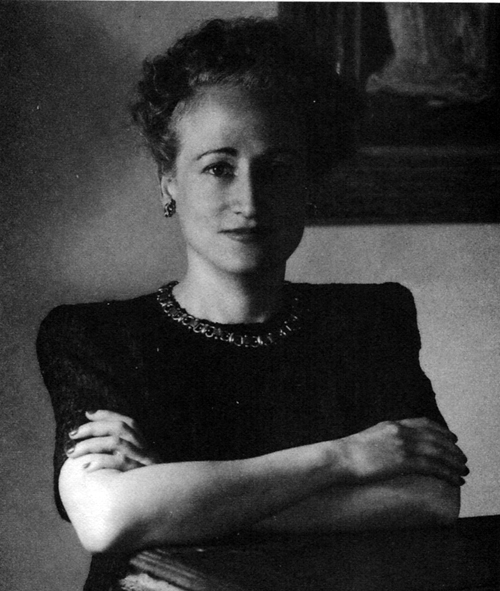

Vera Caspary, 1946.

The earliest novel in Weinman’s collection is also one of the most remarkable of the period. Vera Caspary was a woman to be reckoned with—Greenwich Village free-love practitioner, Communist party member, occasional screenwriter, boundlessly energetic purveyor of suspense fiction, passionate paramour of a married man, and advocate for women in prison. Our State Historical Society holds her personal collection, which includes fascinating notes on projects both realized and unrealized. Turning the pages of her files, you meet a crisp, professional artisan.

So let’s look at Laura the novel. If you know the film, as you probably do, nothing I say will spoil the book for you.

In 1942 Collier’s (“The National Weekly”) offered Caspary $10,000 for the serial rights to Ring Twice for Laura. That sum, equal to $150,000 today, didn’t include book publishing rights, movie rights, and any other ancillaries. The price tag tells us quite a bit about the robust slick-magazine market of the period and about Vera Caspary’s standing. After writing novels, plays, short stories, and screenplays, she was no novice, but her new manuscript set her on a path toward fame. Published as Laura in 1943, it found acclaim as “something quite different from the run-of-the-mill detective story.” The publisher called it a “psychothriller.”

Laura is both a mystery story and a romance. A woman is found murdered in her apartment. Although a shotgun blast has disfigured her face, she’s initially identified as ad executive Laura Hunt. After the funeral, while detective Lieutenant Mark McPherson is poking around her apartment, Laura returns from a trip and it’s revealed that the victim was actually Diane Redfern, a model to whom Laura had loaned the apartment.

The misidentified-victim convention triggers an investigation into the usual sort of suppressed backstory: How did Diane wind up in Laura’s place? Was she alone? Was she the target all along, or was she mistaken by the killer for Laura? Along the way, the cop—already half in love with Laura dead—begins to both woo and browbeat her.

At the same time, a cluster of suspects needs questioning: Laura’s flighty Aunt Susie, her fiancé Shelby Carpenter, and her lordly patron, the columnist Waldo Lydecker. Laura isn’t exonerated either, because she has reason to hate Diane. The usual array of clues—the murder weapon, a bottle of cheap bourbon, and a cigarette case—tugs McPherson this way and that, although his final discovery of the killer depends as much on intuition about personality as about physical traces. The plot hole in the film (why isn’t the artist Jacoby, who painted Laura’s portrait, an obvious suspect?) is there in the original novel as well, but few readers or viewers seem to notice it.

At the same time, a cluster of suspects needs questioning: Laura’s flighty Aunt Susie, her fiancé Shelby Carpenter, and her lordly patron, the columnist Waldo Lydecker. Laura isn’t exonerated either, because she has reason to hate Diane. The usual array of clues—the murder weapon, a bottle of cheap bourbon, and a cigarette case—tugs McPherson this way and that, although his final discovery of the killer depends as much on intuition about personality as about physical traces. The plot hole in the film (why isn’t the artist Jacoby, who painted Laura’s portrait, an obvious suspect?) is there in the original novel as well, but few readers or viewers seem to notice it.

What was striking about the book was its point-of-view structure. “Four persons tell this story and play the leading parts in it,” noted the New York Times reviewer. “McPherson questions all three, and all three tell him lies.” In presentation Caspary revived what has been called the casebook method of composition: a series of testimonies, written or transcribed from speech, that recount the mystery. Sometimes those are accompanied by police reports, newspaper coverage, and other documents.

The method is identified with Wilkie Collins’ two great novels The Woman in White (1860) and The Moonstone (1868), and was taken up occasionally by others, particularly within a trial situation (e.g., The Bellamy Trial, 1929). Before Laura, probably the most famous instance of a mystery collation is Dorothy Sayers and Robert Eustace’s Documents in the Case (1930). The technique also has affinities with multiple-viewpoint assembly in “straight” fiction influenced by Dos Passos; Kenneth Fearing had tried it in his experimental novels The Hospital (1939) and Clark Gifford’s Body (1942) as well as in his crime stories Dagger of the Mind (1941) and The Big Clock (1946).

To take us through the eight days of the investigation, Caspary’s casebook assigns each character a block of narration. Each block, told in first person, has its own distinctive tenor, representing a particular subgenre of mystery fiction.

If you didn’t know the Laura mystique already, you might suspect that the opening chunk, told from Waldo’s perspective, would announce him as the brilliant amateur detective who will solve the case and surpass the plodding McPherson. Waldo is a celebrity columnist, a connoisseur of murder and lethal banter. Like 1920s detective Philo Vance, he collects art and lords it over others through aggressive erudition. Waldo writes in periodic sentences of eloquent self-congratulation:

My grief in her sudden and violent death found consolation in the thought that my friend, had she lived to a ripe old age, would have passed into oblivion, whereas the violence of her passing and the genius of her admirer gave her a fair chance at immortality.

There are even the sort of fake footnotes that we find in S. S. Van Dine and Ellery Queen novels of the 1930s, attesting to the scholarly bona fides of this dilettante sleuth.

Waldo’s power over Laura, as her patron and guru, gets expanded to a remarkable authority over the narrative in this first part. He tells us things he did not witness, chiefly the early “offstage” phases of McPherson’s investigation, and his explanation is that of the artist as god.

Waldo’s power over Laura, as her patron and guru, gets expanded to a remarkable authority over the narrative in this first part. He tells us things he did not witness, chiefly the early “offstage” phases of McPherson’s investigation, and his explanation is that of the artist as god.

That is my omniscient role. As narrator and interpreter, I shall describe scenes which I never saw and record dialogues which I did not hear. For this impudence I offer no excuse. I am an artist, and it is my business to re-create movement precisely as I create mood. I know these people, their voices ring in my ears, and I need only close my eyes and see characteristic gestures. My written dialogue will have more clarity, compactness, and essence of character than their spoken lines, for I am able to edit while I write, whereas they carried on their conversation in a loose and pointless fashion with no sense of form or crisis in the building of their scenes.

This is an extraordinary passage. It opens the very-‘40s possibility that what follows may be Waldo’s fantasy. Only near the end of his text does Waldo assert that his knowledge of McPherson’s investigation is derived from what Mark later told him one night at dinner. We will soon learn that Waldo’s opening section was written directly after that dinner, but he actually didn’t know one key fact. His omniscience is an illusion.

McPherson takes up the tale in the second part. He has read Waldo’s account and treats it as a separate piece of evidence. As we follow McPherson’s investigation, we’re in the realm of the police procedural. The register shifts too. If Waldo’s style is showoffish, McPherson’s is laconic. Whereas Waldo celebrates how his prose will immortalize Laura, McPherson admits that his version of things “won’t have the smooth professional touch.”

Actually, though, it does. It reads hard-boiled.

As we stepped out of the restaurant, the heat hit us like a blast from a furnace. The air was dead. Not a shirt-tail moved on the washlines of McDougal Street. The town smelled like rotten eggs. A thunderstorm was rolling in.

Caspary gives us the voice of the tough but vulnerable cop, the voice we would later learn to call noir. There’s an echo of James M. Cain when McPherson signals that in retrospect he was wrong to trust this femme fatale: he sourly describes himself in the third person.

She offered her hand.

The sucker took it and believed her.

McPherson’s eventual victory over Waldo is prefigured in the cop’s reflections on writing up crime. When Waldo learned Laura was still alive, McPherson says, “The prose style was knocked right out of him.” So much for Wimseyish fops set down in a Manhattan murder.

Shelby gets his voice in as well. A brief third section consists of a police transcript of McPherson’s questioning. Aided by his attorney, Shelby withdraws some lies, dodges uncomfortable areas, and generally remains the most obvious suspect—as well as Mark’s rival for Laura. At this point in the book Caspary begins to play an intricate game of knowledge, in which we get, piecemeal, information that tests the string of deceptions and evasions confronting McPherson.

In the fourth section, Laura writes her testimony. Once more the circumstance of composition is explained to us. Laura confesses that she can’t understand what she thinks and feels unless she sets it down. She has burned her old diaries, but now she has to start over.

In the fourth section, Laura writes her testimony. Once more the circumstance of composition is explained to us. Laura confesses that she can’t understand what she thinks and feels unless she sets it down. She has burned her old diaries, but now she has to start over.

It’s always when I start on a long journey or meet an exciting man or take a new job that I must sit for hours in a frenzy of recapitulation.

Now the action is that of the woman in peril, the figure familiar from Eberhart and Rinehart and Sanxay Holding. And so the stylistic register is “feminine,” tracking fluctuations of feeling and noting costume details and shades of color. Laura’s narration is also suspenseful and contemplative, dwelling on moments that seem to radiate danger—McPherson’s trick questions, Waldo’s sinister manipulations, and Shelby’s pretense that he’s protecting her rather than himself.

The emphasis is less on external behavior than Laura’s growing realization of why she has clung to two failed men. She will gradually realize that McPherson, despite his coldness, is the best match for her. Waldo is “an old lady” and Shelby is an overgrown baby. Caspary the left-winger gives these portraits the taint of class corruption. Waldo and Shelby are ghoulish creatures of the high life, while Aunt Susie is the faded, self-indulgent beauty Laura might become.

Laura’s recognition of her entrapment is rendered in a choppy, spasmodic fashion. Waldo’s, McPherson’s, and Shelby’s accounts have all been linear. Laura’s is not. It skips around in time, replays scenes we’ve seen from other viewpoints, and incorporates dreams that seem as well to be flashbacks.

This is no way to write the story. I should be simple and coherent, fact after fact, giving order to the chaos of my mind. . . . But tonight writing thickens the dust. Now that Shelby has turned against me and Mark shown the nature of his trickery, I am afraid of facts in orderly sequence.

In a narrative dynamic we find throughout 1940s fiction and film, the strong career woman is thrown off balance and succumbs to confusion. The most notorious example is of course Lady in the Dark, the 1941 play that appeared on film in 1944, the same year as the film version of Laura.

The lady returned from the dead will need a real man to rescue her. That rescue is enacted, again, in prose when McPherson reassumes control of the narrative. The book’s fifth part consists of two sections: the classic summing up and denunciation of the culprit (Waldo) and the rescue of Laura from Waldo’s second attempt to kill her. McPherson’s hard-boiled diction has won out. As Waldo is taken away in the ambulance, however, he earns a degree of purely verbal revenge. McPherson’s narration quotes Waldo’s mumbled phrases as, dying, he fills in plot points. In the process, his style gets inserted, like an alien bacterium, into McPherson’s curt passages.

McPherson, who can afford to be gallant, gives Waldo the last convoluted word. It comes in a quotation from the manuscript found by McPherson at the climax, a passage that confirmed Waldo’s guilt. In Waldo’s unfinished account, Laura is an essence of womanhood, a modern Eve; but one who continually reminded him that he could never be Adam.

During production of the film version of Laura, the makers considered mimicking the novel’s block construction. Citizen Kane had made multiple-viewpoint narration more thinkable in the 1940s. In the end, though, only Waldo’s voice-over was retained, with results that have provoked several critical comments.

The film made many other changes, large and small, but during this reading of the novel two improvements stood out for me. Making Waldo a radio commentator as well as a columnist allows a rich play of sound that comes to a climax at the film’s dénouement. Secondly, Waldo drops out of the book for many stretches, largely because Caspary is concerned to throw suspicion on Shelby and Laura. But the film keeps Waldo onscreen a lot, even permitting him (against all plausibility) to tag along with McPherson on the investigation. His waspish interjections, delivered by a suave Clifton Webb, add a nice tang, while sustaining Caspary’s theme of class snobbery. The film adds several kinks, such as introducing Waldo writing in his bathtub. The situation includes one of those how-did-they-get-away-with-it? moments when, as Waldo climbs out of the water, Mark glances scornfully offscreen at Waldo’s privates.

Caspary would go on to other successes, notably the screenplays for A Letter to Three Wives (1948) and Les Girls (1957) and several other novels that play with block construction and shifting viewpoints. But Laura would remain her prime achievement. It’s a striking novel that became a landmark film and an enduring example of how female crime novelists could stretch and deepen the conventions of popular literature.

A useful and spoiler-free biographical survey of many of these writers is Jeffrey Marks’ Atomic Renaissance: Women Mystery Writers of the 1940s and 1950s (Delphi, 2003). See Mike Grost’s inevitably encyclopedic coverage as well.

Highsmith’s disdain for pulpish style is discussed in Andrew Wilson, Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith (Bloomsbury, 2003), p. 124; my quotation above comes from p. 256. I’m grateful to Ms. Stéphanie Cudré-Mauroux of the Archives littéraires suisses for other information about Highsmith.

Some craft advice from these authors can be found in Dorothy B. Hughes, “The Challenge of Mystery Fiction,” The Writer 60, 5 (May 1947), 177-179; Charlotte Armstrong, “Razzle Dazzle,” The Writer 66, 1 (January 1953), 3-5; and Patricia Highsmith, “Suspense in Fiction,” The Writer 67, 12 (December 1954), 403-406. Millar’s discussion of Beast in View is in the International Polygonics edition of the novel, 1983, pp. 1-2, 249.

Vera Caspary’s autobiography, The Secrets of Grown-Ups (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1979), is a captivating read that introduces us to a fascinating personality. (“Under the ready smiles were witches’ grimaces, beneath the padded bra a calcified heart.”) In Wilkie Collins, Vera Caspary and the Evolution of the Casebook Novel (McFarland, 2011) A. B. Emrys offers an excellent study of Caspary’s work in relation to mystery traditions. Caspary’s “official” response to Preminger’s film comes in “My Laura and Otto’s,” Saturday Review (26 June 1971), 36-37.

Hammett was no slouch at juggling proper names and pronouns either. I marvel that he could call Ned Beaumont “Ned Beaumont” all the way through The Glass Key. All the other characters are tagged with their first or last name, but this option maintains an unsettling middle distance on his psychologically opaque protagonist.

I discuss Waldo’s narration in the film version of Laura in more detail in this entry.

Talking THE WALK

Kristin here–

David and I saw Robert Zemeckis’ The Walk the day after it opened. The screening was 3-D Imax, since the film originally opened only in Imax theaters and went wider on October 9, already with the odor of box-office failure wafting over it. We enjoyed it. It’s not an undying masterpiece, but it’s certainly better than many of the reviewers seem to think. In particular, they largely ignore the first portions of the film and imply (or outright state) that you should sit through them because the climactic sequence, protagonist Philippe Petit’s very high-wire walk between the Twin Towers in New York is worth it. David Rooney’s review for The Hollywood Reporter boils down the dismissive attitude toward the early portions: “The film’s payoff more than compensates for a lumbering setup, laden with cloying voiceover narration and strained whimsy.” Peter Debruge’s Variety review is an exception, dealing with the earlier scenes insightfully.

The view from Lady Liberty

I was surprised to see that Matt Zoller Seitz, one of our best reviewers, gave The Walk a mere two and a half stars. Starting to read his review, I was expecting that he might dismiss the early part of the film as too lightweight and comic to balance the spectacular set-piece of Petit’s performance or something of that sort. Instead, his primary objection to the film is the voiceover and sometimes to-camera narration delivered by Petit, who is shown as standing atop the torch of the Statue of Liberty. More specifically, the film opens with a tight close-up of Joseph Gordon-Levitt as Petit staring directly into the camera against a pale-blue background and saying “Why?” What follows, he says, is to explain why he made his famous walk. The camera then pans to an extreme-long shot of the World Trade Center, pulls abruptly back to reveal the Statue of Liberty (above), and cranes up to Petit standing on the torch.

The rest of the film consists of a series of flashbacks told from this imaginary space, for surely we are not to imagine that Petit ever really climbed the torch. Like it or not, a certain whimsical tone is set up concerning the process of his telling his tale. The film returns to this narrating situation at intervals, usually only for a single shot and usually for a transition into a new scene, with what Petit says in the fantastical present bleeding over into that scene to set it up.

Seitz’s objections to the narration are two. First, he sees it as an attempt to, in a sense, “sell” us The Walk through the enthusiastic tone of the narration. Second, he considers the narration to be redundant, adding almost nothing to the visuals. His prime example of the latter is the scene in which a seagull briefly hovers over Petit and his voiceover comments on its sudden appearance.

The idea that the narration was annoying or redundant never occurred to me when I watched the film for the first time. After reading Seitz’s review, I considered writing this entry and went back to see the film again. I still didn’t find the narration problematic. I think that it contributes to The Walk in a variety of ways. Possibly some of it could be cut, but most of it functions in ways that go beyond what is conveyed through images and dialogue.

Take the seagull scene. Without narration, it could create suspense. Just before it appears, Petit has lain down on the wire, and the voiceover speaks of the serenity of the sky and clouds. Suddenly the bird is hovering right above our hero. The logical reaction would be to worry that it’s going to strike him, break his concentration, somehow threaten him. The voice continues: “Then, something appears. An apparition! A bird. This bird is looking at me! I feel this silent threat.” (The bright-red rims of the bird’s eyes may be a subjective rendition of Petit’s reaction.) The threat he feels, however, is not that the bird will harm him. Instead, he is “invaded by doubt” and decides that it is time for him to end his walk. His narration is not telling us simply that a bird has appeared, but that he takes it to be some sort of symbol of threat. It marks a turning point in the Walk, one which we can only grasp because he tells us that it does. If he had not spoken, what would we have? Presumably Petit seeing the bird, getting up, and continuing his walk. Perhaps he would have a look of doubt on his face, and the music might go into a minor key. Still, we would not know specifically that the bird has caused him to decided to end his walk, because he does not do so for some time after that point. The narration is not simply redundant.

More generally, I think the narrating situation and the treatment of the story as a series of flashbacks with occasional voiceover have two major functions. First, the narration clearly establishes that Petit survives the Walk. Sure, a lot of people walking into the theater know that the historical Petit did survive it and is still alive. Some of us are old enough to have seen or heard news coverage at the time, while others may have read his memoir To Reach the Clouds, upon which the film is based, or seen James Marsh’s 2008 documentary, Man on Wire. Younger moviegoers may have read infotainment coverage of Zemeckis’ film. But there are undoubtedly also people entering the theater knowing nothing about Petit. For them, the film needs to establish his survival if they are not to watch the Walk sequence in constant suspense over whether the protagonist will survive it. The very first word he speaks, “Why?” deflects us from anticipation of the Walk as a spectacular stunt to a curiosity about its significance.

Second, Petit-as-narrator sets the tone for the film, a tone which would perhaps be sufficiently conveyed by the visuals, the action, and the music in some scenes, but not, I think, in others. The tone is light and comic and enthusiastic in the first half of the film, though it shifts later, for reasons I’ll get to in a minute.

Third, the narration helps to break the parts of the film into three separate genres: a romantic comedy (the first half hour), a suspense film (from roughly 30 minutes to 86 minutes), and a lyrical, psychological character study thereafter. The narrational tone changes with each, from ebullience to simple reportage to reflective inner monologue.

David and others have suggested that overall The Walk is structured somewhat like a heist film. In heist films there is emphasis on planning and preparing, with everything explained ahead of time and in intricate detail. The long process of the lead-up is as much the point, or more so, than the actual moment of the theft. (In the review linked above, Debruge points out that “Much of what made ‘Man on Wire’ so thrilling was the fact that Marsh had approached Petit’s story like a caper film.”)

Even though Petit’s goal is not to steal some fabulous treasure from a seemingly impregnable location, his Walk is technically a crime. Still, it is a crime that he cannot conceal, and unlike the masterminds in heist films, he presumably is resigned to the fact that he will certainly be arrested. And unlike in the heist film, there is no planning for an escape and no escape scene. Petit will triumph as long as he completes the Walk before the arrest.

Yet some critics, whether or not they like the film, have ignored or dismissed the rest of the film and focused on the climactic walk as if it is (or should be) the whole film. Some of them, at least, want to treat The Walk as a suspense-filled action film. Yet this is not simply an action film with a boffo climax. Why, though, separate a film into acts in three genres? I think it is because the film wants to clear away the more obvious conventions of a Hollywood films of this type during the early portions of the film. These then drop away in order to allow the Walk sequence to be pared down, without romance and with muted suspense, to a lyrical focus on the peace and beauty of Petit’s perambulations back and forth above the city.

The rom-com

During the first half of the film Petit courts Annie, charms Rudy into helping him, and finds two other “accomplices” to help him fulfill his dream. It’s all a bit like Amélie in tone, with a hint of Jules and Jim in the music. We have to be won over by Petit to some extent if we are to take an interest in anything about the Walk except the facts that the man made it from one Tower to the other and back a few times and that it sure looks great in 3-D Imax.

Some critics clearly weren’t won over. Others were. Debruge points out, “Say what you will about the accent, but Zemeckis and co-writer Christopher Browne have captured Petit’s voice — the real, honest-to-God way he expresses himself — and by channeling that, the actor successfully wins us over from the outset, hanging out in the Statue of Liberty’s torch.” If my own reaction is any indication, one can find Petit a bit hard to take at times and still consider his narration, Lady Liberty’s torch and all, an asset to the tale.

In describing classical Hollywood cinema, David and I have repeatedly pointed out that films in this tradition usually have two plotlines, one a romance and the other to do with work or danger or some sort of project. These two plotlines tend to be connected, with the romance somehow linked to whatever else is happening in the protagonist’s life.

In The Walk, the romance is there, but it is minimized. The development of the attraction between Petit and Annie is squeezed largely into the first quarter of the film. It moves very quickly once we get past the meet-cute antagonism between them over Petit’s stealing the audience listening to Annie’s street singing. Almost immediately they are in a cafe, sipping wine and discussing his dream over a little improvised model (above left), and then in his apartment, with more wine by candlelight and discussion of the dream over a photo of the Twin Towers. The two seem already to be a couple. It’s as if the romance progresses offscreen, in scenes that we don’t witness–the first kiss, the moving in together.

Annie raises no objections to Petit’s crazy goal, as one might expect her to. There is little sense of how much time has passed. All we know is that Annie urges Petit to fulfill his dream, and she becomes his first accomplice. For the rest of the film, she will be little more than first among the accomplices and an onlooker to the preparations and the Walk. Apart from a quick kiss and her loyal overnight vigil outside the Towers as Petit and the other accomplices invade the buildings and set up for the Walk, Annie has almost nothing to do during the preparations for the Walk and the Walk itself. She does, however, get to characterize the lyrical part of Petit’s achievement. Later, when Barry remarks now New Yorkers love the Trade Towers, Annie adds that Petit has brought them to life for people and given them a soul. The romantic plotline is further undercut almost immediately, however, when Annie unexpectedly leaves Petit to return to France and find her own dream.

During the first half of the film, Petit’s narration is humorous, bumptious, perhaps a little too ingratiating, depending on your taste. He might seem a bit annoying and capricious, as young men often are in rom-coms. The implication may be that the quirks of his personality are part and parcel of the genius and drive that allow him to perform the feats he does, as his cocky little smile upon being arrested for walking between the towers of Notre Dame suggests. (Note that Barry, who eventually becomes the “insider” accomplice once the team arrives in New York, says he had witnessed Petit’s Notre Dame walk, and sure enough, there he is in the back of this shot and visible in another view of the crowd watching.)

If Petit is selling anything, it’s not the film but himself, and we do not need to like him to admire him.

The suspense film

Petit and his accomplices to go New York at roughly the midway point of the film, and The Walk segues temporarily into a suspense film. Where one might expect the Walk itself to be the section designed to ramp up suspense in the audience (as many critics did), the more conventional suspense-generating actions are more prominent in the preparation for it, which constitutes the third quarter of the film. This takes place from 55 to 86 minutes. It begins at the airport, with a comic scene of a customs official reeling off the contents of Petit’s equipment containers (above). When he asks what the equipment is for, Petit cheekily replies that he’s planning to use it to walk between the Twin Towers. The official unconcernedly allows him through.

Soon the tone becomes more serious, as Petit visits the Towers and is overawed and intimidated to the point of feeling that his plan must be abandoned. Standing in the lobby of the South Tower, he speaks of feeling that there is no way to get to the top. Immediately a service door behind him swings open, a worker appears and greets them, and the man departs, leaving Petit to investigate the room beyond, discovering a stairway to the top.

Soon he emerges on the top of the building, tries teetering over the void on a projecting metal girder, and is clearly ready to take up his dream again.

Eventually the tone of the Development turns more tense, as Petit obsessively goes over the plan with his accomplices and the day of the “Coup” approaches. Late on the night before the group invades the Towers, Petit awakens and nails shut the “coffin,” a crate containing the equipment, and expresses his doubts to Annie. Ebullience has become dead seriousness, though Petit determinedly avoids referring to death.

Once the actual invasion of the Towers begins, the tone ratchets up the tension and the delays typical of a Development portion occur. Although the team’s fake delivery truck is admitted to the loading docks, a lack of access to the elevators nearly scuttles the plan. Once Jeff and Petit are on the unfinished upper stories of the South Tower, a guard interrupts them as they unload their equipment in the unfinished upper stories of the South Tower. They end up hiding for fours astride a metal girder above an unfinished elevator shaft extending down so far that we can’t see the bottom. Jeff, who suffers from a terror of heights, becomes our identification figure briefly, as he suffers through this ordeal. Later, once they are on the roof in the dark of night, a guard comes up with a flashlight and nearly bumps into Jeff before being lured away to a lower floor by a colleague offering to share a pizza.

As dawn approaches, the threats to the success of the Walk continue. An arrow is shot from one Tower to the other to begin the process of hauling the wire across teeters on the corner of the building. The bracing wires are loose, and Petit must drag a terrified Jeff onto the side of the roof to help tighten them. At dawn, a mysterious man in a suit visits the roof, apparently just for the view, and sees them. After a nerve-wracking face-off, he ultimately leaves without challenging them.

Interestingly, during this face-off, Petit picks up a length of pipe. After the man leaves, Petit seems shocked to find that he has been holding it in a potentially threatening fashion. This is the only hint we ever get of the lengths to which he might go to make his dream succeed.

There is also a good deal of exposition in this section of the film, part of it accomplished by the narrating voice, setting up for what will happen during the Walk. As a result, we don’t need to be told about the technical details during the Walk itself. There is, however, a fairly long stretch with no voiceover leading up to the silent confrontation with the mysterious man. After he leaves, Petit’s narration notes, “And that was the moment in my adventure that I call ‘the mysterious visitor.'”

This last incident works in with the many other bits of good luck that have allowed Petit to accomplish his dream, including the fortuitous opening of the stairwell door mentioned above. It adds a touch of suspense, as well as realism. Such things do occur–and in this case, really did occur.

The lyrical walk

Romance and suspense having been presented and set aside, the film defies convention by switching into lyrical mode. In a conventional film, the grandeur of the mise-en-scene would become a terrifying void (especially in 3-D) into which we constantly fear Petit will fall. Instead, to a large extent because of the narrating voice and the music, we instead follow Petit’s exhilarated reaction and his every shift of mood. For instance, when he stands with one foot on the wire and pauses before beginning his Walk, subjective mist gathers (see bottom). It conveys his sense of the rest of the world disappearing and his attention focusing entirely on the wire. His voiceover describes all this. Would we otherwise perhaps take this mist to be an actual passing cloud?

Similarly, when he finishes the first crossing and starts back, would we understand why if we had only the image and music? Or when he kneels during the return trip to the South Tower, would we grasp that he is saluting the wire, the Towers, and so on, if his narrating voiceover did not tell us?

There are details that set up some suspense but are at the same time tied to Petit’s emotional reactions. He remarks that one of the the cavaletti holding the bracing lines onto the wire being upside down. This seems initially to be used as an occasion for Petit to mention his gratitude to Rudy, though it also sets up for the later moment when the plate threatens to buckle under the strain–a moment which ultimately comes to nothing.The detail shot of Petit’s shoe during this scene sets up some suspense, in that a small, wet patch of blood suggests that he may later be endangered by the wound from stepping on a nail. Later we see more blood on the shoe, but the wound in fact never causes him to falter. In this close shot, the shoe also conveys a visceral sense of the moment of the walk and reminds us of the practice that has gone into it, imprinting a channel where the wire has pressed into his foot.

Of course, we are unable entirely to view the scene without suspense, as our bodies naturally react to the strong illusion of height created by the extraordinary CGI imagery and the 3-D. The word “suspense,” after all, derives from the notion of dangling in space. Yet the film constantly backs us away from such jitters in part through the soothing voiceover.

Suspense also returns to some extent just after the salutes, when the police appear, initially on the South Tower end of the wire. An even greater threat, a police helicopter, eventually appears.

These authorities offer or threaten to help Petit off the wire, endangering him in the process. His evasive maneuvers and defiance create humor that somewhat dispels the suspense. Ultimately, by tossing his balance pole at the outstretched hands of the startled police, Petit manages to clear the way for a triumphant exit from his Walk. This conclusion assures that he controls the entirety of his feat, despite the fact that he is immediately arrested. The applause of the workmen on the lower levels as he is escorted out confirms his triumph, as does the praise offered by one of the arresting officers (seen at the left below). The voiceover description of his later minor “punishment” of performing a lower-wire act for children in Central Park confirms that he has successfully defied even the law.

Zemeckis, classical director

While Zemeckis has a reputation as a master of the action set-piece, he can also construct a tight classical narrative. Seeing The Walk a second time for the purpose of writing this entry, I realized that the script is very carefully put together to set up for everything that will happen, both causally and in terms of information.The arrest in Paris makes it clear to us that Petit will face a similar punishment after his Trade Towers Walk. Petit’s fall from the wire in the circus tent and Rudy’s emphatic advice that the last three or four steps are the most dangerous foreshadows the similar moment at the end of the Walk where Petit momentarily looses control and his trembling makes the wire itself shake. In many cases, the voiceover plays a vital role in setting up things to come.

Perhaps it’s not as perfectly put together as Back to the Future, but then, few films of the past decades in Hollywood are.

As David noted during our first viewing, the film also has a good, old-fashioned Hollywood visual motif. Round shapes are contrasted with straight lines, the round ones being associated with Petit’s early ground-based entertainment career and the lines with his high-wire acts. The lines may be obvious to viewers, as when Petit draws a line between the Towers in an image, or less so, as in the scene where an arrow is tested as a means for starting the process of sending the wire from on Tower to the other.

Unfortunately none of the video material currently online shows portions of the street-entertainment scene of the film’s early section, so I can provide no images of the round items. These include the perfect chalk circle that Petiti draws to delineate his performance space, the top hat in which he collects coins, the red-and-white candy mint, his unicycle’s wheel, the ring under the White Devils’ tightrope in the circus tent, the arch in the same ring that frames Petit when he juggles to impress Rudy, and the umbrella he uses to shelter Annie in a sudden rain shower.

Such imagery disappears in the second half, apart from repeated overhead shots of the circular fountain on the ground between the Towers, often with the lines of the wire and the balance bar juxtaposed with it (see top). It recalls Petit’s initial performance space on the ground and subtly reminds us of how far, and high, he has come since then. (During their first meeting, Annie remarked of Petit’s tightrope, “That was the lowest high-wire I’ve ever seen.”)

In the end, the answer to the original question, “Why?” is that “There is no why.” When Petit sees a beautiful place in which to place his wire, he feels compelled to do so. His motive is not to show off his derring-do or to spice up his life with risk-taking. His is an aesthetic compulsion, and the Walk is referred to a number of times as an artwork. The form of the film reflects that compulsion.

The last lines of the film return to the Towers themselves. Petit narrates over a shot of himself returning to visit the top of the Towers, telling us that an official gave him a pass to visit it. We return to the torch atop the Statue of Liberty, where he looks at the card and says, “He wrote on it ‘Forever.'” This could have been told visually, I suppose, but it would have meant close-ups of the card, probably a second person on the roof to whom Petit could explain his card–something, at least, more elaborate and less effective than simply having him tell us this information. A pan moves us toward the Towers, gleaming in the sunshine until the slow fade-out that conveys the fact that for the Towers, forever was cut brutally short. That final salute, at least, seems to have pleased everyone.

As I said at the outset, The Walk is not necessarily a masterpiece, but it is far better than some of the reviews would claim. Seeing the film a second time, I enjoyed it more and found new things to notice, which is always a good sign. I did not find the voiceover narration annoying during either viewing, and it isn’t really dispensable. The film is worth seeing, and its extraordinary climactic scene will suffer greatly from being seen on a video screen.

The Wire provides another example of a phenomenon which David discussed in relation to Paul Greengrass’ United 93: our inability to wholly suppress a feeling of suspense even when we know the outcome of an event. Simply seeing Petit on the wire high above the ground to some extent creates an involuntary state of tension.

Hitchcock again: 3.9 steps to s-u-s-p-e-n-s-e

Henry Edwards; Alfred Hitchcock.

DB here:

My previous entry reminded you that Hitchcock was notorious for distinguishing between suspense and surprise. To achieve suspense, he maintained, the audience has to be aware of more than the characters know. Surprise arises when we know as much as the characters, or less. Hitchcock also declared his general preference for suspense, since it provides prolonged tension while surprise produces merely a momentary buzz. The mystery was: Where do this distinction and this preference come from? Are they original with Sir Alfred, or can we find precedents?

The story so far:

Step 1: The distinction itself goes back at least to the eighteenth century and the playwright/theorist Gotthold Ephriam Lessing. Lessing likewise expressed his preference for suspense because it demanded superior craftsmanship and yielded stronger effects on the audience.

Step 2: The distinction and the preference for suspense was still circulating in late nineteenth and early twentieth-century commentaries on theatre. My entry also mentioned a 1922 screen playwriting manual by Howard Dimick that took the same stance.

So we’ve located general conditions for influence. By the early 1920s, the suspense/surprise doublet was still circulating in the worlds of film and theatre, when Hitchcock was starting his career. But influence, like its source-word influenza, requires close contact. It would be good to find the secret agent who might have passed along the idea to the young director.

Step 3: My P.S. to the entry ropes in one candidate: Eliot Stannard. Richard Allen proposed him as a possibility, and Ian Macdonald supplied information that strengthened the suspicion. Stannard was a busy screenwriter of the period, who worked closely with Hitchcock on nearly all his silent pictures, and he even wrote a manual on screenwriting. Although he apparently didn’t talk about suspense and surprise in print, he would have known William Archer and other drama theorists who did. Stannard could well have initiated Hitchcock into the idea.

Step 3.9: But do we have the wrong man? After I posted my P. S., another foreign correspondent weighed in. Charles Barr writes:

A key figure here is Henry Edwards. Director in British cinema 1916-1937, and actor for much longer. His (lost) feature film Lily of the Alley in 1923 made a big point of avoiding intertitles. Whether or not he saw it, Hitchcock must have at least been aware of it, even though later he always said that The Last Laugh was the first such film. And already in 1920 Edwards had spelled out the surprise/suspense distinction: see attachment from the trade paper The Bioscope.

Edwards was indeed a major figure, as producer, actor, and director during the 1910s and 1920s. At the British Film Institute site, Geoff Brown and Briony Dixon provide a lively account of his career. He was clearly in a position to influence younger filmmakers.

The 1920 Bioscope article, cited in the Brown/Dixon overview and supplied to Charles by Ph.D. student Michaela Mikalauski, is a revelation. Edwards writes:

We must so construct our story that suspense is created–suspense is the dread that something may happen, and it is on this that we must build our story.

We must so construct it, that by careful preparation impeding difficulties or dangers are looming up before our characters. We must show the audience these dangers, and keep our characters ignorant of them until the proper moment; and it is the nearing of the danger to the blissfully ignorant character, making us long to cry out and warn him, that give suspense.

Tellingly, Edwards uses an example of an explosion. Imagine that our hero, wandering in the wilderness, has taken shelter in a shack. He sits on a box and lights a cigarette. While he has a leisurely smoke, his match has ignited some dry rubbish by the box. He rises and leaves the shed, just as the box is blown to pieces. Now we realize that it contained dynamite.

Here is a case in which there is expectancy, and never for a moment suspense, because the audience does not know of the impending danger to the character.

Now let us defy the critics who clamour for “surprise” in film construction, and tell the incident in the language of the screen.