Archive for the 'Narrative: Suspense' Category

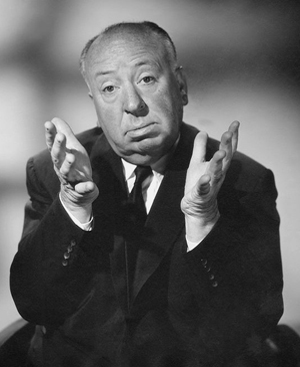

Hitchcock, Lessing, and the bomb under the table

DB here:

Every good cinephile knows Alfred Hitchcock’s famous distinction between suspense and surprise. In articles and interviews from the 1930s on, he explained that situations are more gripping if the audience has more knowledge than the characters do. His classic example, in conversation with Truffaut, was a bomb under a table.

We are now having a very innocent little chat. Let us suppose that there is a bomb underneath this table between us. Nothing happens, and then all of a sudden, “Boom!” There is an explosion. The public is surprised, but priot to this surprise, it has seen an absolutely ordinary scene, of no special consequence. Now, let us take a suspense situation. The bomb is underneath the table and the public knows it, probably because they have seen the anarchist place it there. The public is aware that the bomb is going to explode at one o’clock, and there is a clock in the decor. The public can see that it is a quarter to one. In these conditions this innocuous conversation becomes fascinating because the public is participating in the scene. The audience is longing to warn the characters on the screen: “You shouldn’t be talking about such trivial matters. There’s a bomb beneath you and it’s about to explode!”

In the first case we have given the public fifteen seconds of surprise at the moment of the explosion. In the second case we have provided them with fifteen minutes of suspense.

In Film Art, we invoke Hitchcock’s example to illuminate how narration can be more or less restricted. You can confine the narration to what only a character knows, or you can expand it to give the viewer story information that a character doesn’t have. By widening the audience’s knowledge somewhat, you can build suspense; by confining it, you can make the audience share the character’s surprise.

After Hitchcock came to the United States, he often invoked this distinction in interviews, and it became part of craft lore among writers of screenplays and genre fiction. I trace the idea’s fortunes a little in the online essay, “Murder Culture.” In practice, though, Hitchcock didn’t always follow through. Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941) confine our knowledge very closely to the protagonist’s, without providing that wider perspective he advocates in his remarks to Truffaut. And surprise is central to some Hitchcock works, notably Psycho.

In other films, of course, he did follow his own advice. When Johnny Jones detours to the Tower of London in Foreign Correspondent, we know that the little man steering him there intends to kill him. Shadow of a Doubt lets us see Uncle Charlie in a sinister light before he visits Santa Rosa, and glimpses of his behavior strongly hint that he will menace Young Charlie when she starts to investigate him. And of course The Greatest Film Ever Made (or is it?) tips us off to what’s really going on with Madeleine/ Judy before poor Scottie grasps it.

I’ve wondered: Is this suspense/surprise distinction original with Hitchcock? In the tapes of the original interview with Truffaut, he notes: “You know, there has always been this dispute between suspense and surprise. . . . What I’m saying is not new, I’ve said this many times before.” He then launches into a more expansive account of the bomb-table scenario.

His formulation is ambiguous. Is the distinction “not new” because it’s been around a long while (“always”), or because he’s reiterated it many times? And is his preference for suspense an uncommon opinion? Exact answers may lie in the vast Hitchcock literature, but so far I haven’t found them. Here’s what I came up with.

What enduring disquietude

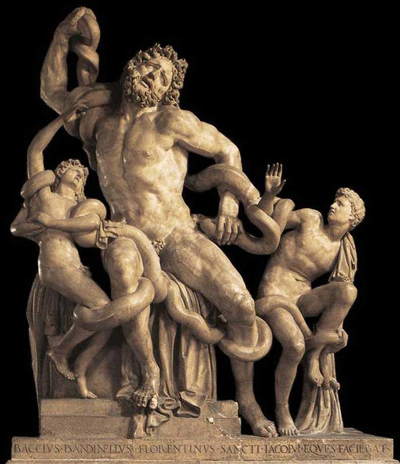

Gotthold Ephriam Lessing was a playwright and drama theorist. His Miss Sarah Sampson (1755) is sometimes considered the first “bourgeois tragedy” in German, and his best-known play is perhaps Nathan the Wise (1779), a classic that was made into a notable silent film. Lessing is also famous for his influential book-length essay Laocoön: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry (1766), which has been a center of debate in aesthetics ever since.

In that piece he argued for a fundamental distinction between time-based arts (drama, literature) and arts of space (painting, sculpture). From that distinction Lessing inferred a principle of decorum, or expressive fitness, for different media. He claimed that the famous sculpture showing Laocoön and his sons caught in the serpent’s coils could express only a split-second of pain, not the extended agony of their struggle. As a three-dimensional image, the father’s scream is vivid, but it lacks “all the intermediate stages of emotion” that a poem could have rendered as it unfolded in time. The great film theorist Rudolf Arnheim argued that the sound film obliges us to ask whether moving images and recorded dialogue cover different expressive territories, so he called his essay “The New Laocoön.”

Lessing also ruminated on the drama, and his thoughts about playwriting, set down in notes written between 1767 and 1769, contain many intriguing observations. In one passage, he replies to writers who have criticized ancient Greek playwrights for giving away too much in their prologues. These critics have implied that audiences would be more satisfied if big events took them by surprise. So, says Lessing mockingly, let’s simply reedit the plays and chop out all the information that sets up the final reversals.

His serious point is that a surprise yields only a transitory thrill. In the passage below, he uses “poet” and “poem” in a general sense, including storytellers and dramatists, plays and prose fiction.

For one instance where it is useful to conceal from the spectator an important event until it has taken place there are ten and more where interest demands the very contrary. By means of secrecy a poet effects a short surprise, but in what enduring disquietude could he have maintained us if he had made no secret about it! Whoever is struck down in a moment, I can only pity for a moment. But how if I expect the blow, how if I see the storm brewing and threatening for some time about my head or his?. . .

[By not preparing the spectator] the whole poem becomes a collection of little artistic tricks by means of which we effect nothing more than a short surprise. If on the contrary everything that concerns the personages is known, I see in this knowledge the source of the most violent emotions.

Lessing is evidently thinking of classic cases of recognition, plot twists that reveal connections among characters that they were long unaware of. (Oedipus is actually the son of the man he killed!) At another point, Lessing’s English translators find the word Hitchcock uses: “Our participation will be all the more lively and strong the longer and more confidently we have foreseen the issue.” “Foreseeing” here might be too strong, because in Hitchcock’s parable of the bomb we don’t really know the outcome. Will the men at the table escape in time, or halt the bomb, or be blown up? The inevitability of catastrophe that we expect in Greek tragedy produces a different sort of suspense than we experience in modern narratives. Yet it remains suspense nonetheless.

Lessing goes on to suggest that Aristotle valued Euripides most among dramatists not because of the plays’ gruesome endings but at least partly because “the author let the spectators foresee all the misfortunes that were to befall his personages, in order to gain their sympathy.” In other words, we have that sort of unrestricted narration we usually call omniscience. That’s what is at stake in Hitchcock’s bomb example.

Clairvoyant aloofness

It’s a long stretch from the late eighteenth century to Hitchcock’s time. Thanks to Google, and especially its wondrous Ngram software, we can get a rough sense of what happened to the duality of suspense and surprise in those intervening years.

A quick sampling shows that they were conjoined by the late nineteenth century. An anonymous 1884 critic finds that in Tennyson’s plays “the elements of suspense, of surprise, are altogether wanting.” In 1882, J. Brander Matthews, towering authority on theatre history, praises Hugo’s vibrant play Cromwell:

There is the familiar use of moments of surprise and suspense, and of stage-effects appealing to the eye and the ear. In the first act Richard Cromwell drops into the midst of the conspirators against his father,–surprise; he accuses them of treachery in drinking without him,–suspense; suddenly a trumpet sounds, and a crier orders open the doors of the tavern where all are sitting,–suspense again; when the doors are flung wide, we see the populace and a company of soldiers, and the criers on horseback, who reads a proclamation of a general fast, and commands the closing of all taverns,–surprise again. A somewhat similar scene of succeeding suspense and surprise is to be found in the fourth act.

Throughout this period writers fairly often counterpoised suspense and surprise as two essential strategies of plotting. But do the writers recognize the narrational implications they harbor, and do writers display Hitchcock’s preference for suspense? Yes to both.

George Pierce Baker, early twentieth-century drama macher, weighed in with his book Dramatic Technique (1919). He notes that in Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part I, a revelation of the Countess’s plan yields “a momentary sensation, surprise.” Baker reimagines two versions of the situation: When we know more than one of the antagonists does, and when we know more than both of them do.

Suppose we had been allowed to know the plans of the Countess, and they had seemed very dangerous for Talbot. Then, as she played with him, there would have been more suspense than in Shakespeare’s text, because an audience would have been wondering, not merely “What is the blow Talbot will strike?” but “Can any blow he will strike overcome the seemingly effective plans of the Countess?” Suppose we had been allowed to know the plans of both. Then, as we watched the Countess playing her scheme off against the plan of Talbot, of which she would be unaware, might there not easily be even more suspense? At every turn of their dialogue we should be wondering: “Why does not Talbot strike now? Can he save the situation, if he delays? With all this against him, can he save it in any case?”

Baker concludes that surprise enlivens the situation, but suspense allows for deeper characterization: awaiting an outcome, we must speculate on the characters’ temperaments, motives, and strategies.

Baker has already cited the Lessing passage I’ve mentioned, and he goes on to quote another authority of his period, William Archer. Archer’s Play-Making (1912) became something of a Bible for aspiring playwrights. (Preston Sturges swore by it.) Without explicitly mentioning suspense or surprise, Archer celebrates the pleasures of lording it over the characters.

The essential and abiding pleasure of the theatre lies in foreknowledge. In relation to the characters of the drama, the audience are as gods looking before and after. Sitting in the theatre, we taste, for a moment, the glory of omniscience. With vision unsealed, we watch the gropings of purblind mortals after happiness and smile at their stumblings, their blunders, their futile quests, their misplaced exultations, their groundless panics. To keep a secret from us is to reduce us to their level, and deprive us of our clairvoyant aloofness.

All of these drama theorists are promoting the well-made play as the best model for plot construction. They’re reacting against popular melodrama, with its episodic construction, wild coincidences, and startling twists–a model of what our colleague Lea Jacobs calls “situational” dramaturgy. The preference for suspense is a recognition of the playwright’s adroit shaping of the plot, preparing the later revelations carefully but also creating a steady arc of tension rather than a firecracker string of surprises. Suspense, it’s implied, is just more difficult to achieve than surprise, and a successful passage of suspense testifies to the writer’s skill.

In sum, by the time Hitchcock started his film career, the suspense/surprise couplet was fairly common in discussions of playwriting, and the superiority of suspense was more or less assumed. A 1922 essay concedes, “Whether or not surprise has a legitimate place in the drama is debated by commentators.” But the author, one Delmar Edmundson, suggests that an “entirely unexpected” turn of events in a one-act play can yield a valid thrill, just as in an O. Henry story. Still, the author suggests that even such a twist needs to be subtly prepared for.

In 1922 as well, Howard T. Dimick’s Modern Photoplay Writing: Its Craftsmanship devotes a whole chapter, “Suspense, Excitement, and Crisis,” to the need to make the viewer “participate” in the action. The melodrama Lady X, then recently adapted to film, affords an example. The attorney defending an older woman is in fact her son, though neither of them knows it. (Shades of ancient Greek theatre.) The result is double suspense: we, like the characters, worry about the outcome of the trial, but we also wonder whether they will discover their kinship. “Had the woman’s identity been kept from the spectators till the end and then ‘sprung’ with explosive suddenness, fully half the emotional effect would have been stripped from the play.” Lessing had already anticipated the power of situations of unknown identity: “None of the personages need know each other if only the spectator knows them all.”

At this point, I can’t say precisely how Hitchcock learned of the distinction between suspense and surprise. Clearly, though, the idea was circulating in the theatrical and cinematic milieu of his early career. It’s entirely possible that he read Archer, Dimick, or some comparable source.

In any event, the distinction isn’t original with him. He is, however, the person who made it central to conversations about filmic construction. Recall that he always denied making detective stories. As the Master of Suspense, he wanted to play down the startling solution to a mystery and instead emphasize slowly building tension. And his continuing reliance on the distinction reminds us that the man always in search of what he thought was “purely cinematic” owed a great deal to the theatre. Some critics complained about divulging Judy/ Madeleine’s secret partway through Vertigo, but here, as in most of his films, Hitchcock was adhering to lessons learned from the well-made play. The result was a “disquietude” that endures.

Hitchcock’s remarks appear in Truffaut, Hitchcock, p. 52 of my 1967 edition. There he somewhat qualifies his position about superior knowledge, adding at the end of the passage I’ve quoted: “The conclusion is that whenever possible the public must be informed. Except when the surprise is a twist, that is, when the unexpected ending is itself the highlight of the story.” I take it that this plot construction is different from that of a mystery plot, which poses questions explicitly (whodunit?). A twist ending, by contrast, catches us by surprise because we didn’t suspect that certain aspects of the situation were in question. Central examples would be Stage Fright, Psycho, and, more recently, The Sixth Sense.

Truffaut’s Hitchcock book (the first hardcover film book I ever owned, I think) is a considerable condensation of the extensive interview. The sessions, punctuated by sounds of cigars being lit and snacks being eaten, are preserved on tape. Thanks to the Internets, they are available here. Hitchcock’s slightly more elaborate version of the bomb scenario occurs in session 4, starting at 17:44.

You can read the books I’ve cited in free digital versions: Lessing’s Laocoon and his essays on theatre; J. Brander Matthews’ French Dramatists of the 19th Century; William Archer’s Play-Making; George Pierce Baker’s Dramatic Technique; and Howard T. Dimick’s Modern Photoplay Writing: Its Craftsmanship. Print editions are also available, of course. Other passages I’ve quoted come from Anon., “New Editions of Tennyson,” The Critic and Good Literature (15 March 1884), 123; and Delmar J. Edmundson, “Writing the One-Act Play VIII: Suspense and Preparation,” The Drama 12, 7 (April 1922), 258. Arnheim’s essay “The New Laocoön” is in Film as Art. For more on situational dramaturgy, see Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema (Oxford, 1998).

Thanks to Hitchcock adept Sidney Gottlieb for helpful advice on this entry. Anyone interested in Hitchcock needs to consult Sid’s excellent collections Hitchcock on Hitchcock and Alfred Hitchcock Interviews. The suspense/surprise duality recurs throughout them in varied forms.

Google’s Ngram software is here. It’s a tremendously useful tool for historical research.

I’d be grateful to anyone who can help pin down sources for Hitchcock’s acquaintance with the suspense/surprise couplet. As ever, feel free to correspond and I’ll update the entry as necessary.

P.S. 30 November 2013: Correspondence incoming! Richard Allen, NYU professor, lead guitarist, and Hitchcock expert, suggests in an email: “One suspects that the person who probably introduced Hitchcock to this was Eliot Stannard.” Stannard participated in writing all but one of Hitchcock’s all-silent films, and he published a short manual on screenplay technique, Writing Screen Plays (1920), derived from columns he published in Kine Weekly.

I haven’t been able to determine whether Stannard opined on the suspense/surprise duality, as the manual is extraordinarily rare, and the writing on Stannard that I’ve seen doesn’t explore this aspect of his work. Nonetheless I can recommend Charles Barr, English Hitchcock (Cameron & Hollis, 1999), 22-26; Barr’s article, “Writing Screen Plays: Stannard and Hitchcock,” in Young and Innocent? The Cinema in Britain, 1896-1930 (Exeter University Press, 2002), ed. Andrew Higson, 227-241; and especially Ian W. Macdonald’s chapter, “Hitchcock’s Forgotten Screenwriter: Eliot Stannard,” in his brand-new and enlightening Screenwriting Poetics and the Screen Idea (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), 132-160. Further information on Stannard, or other sources of Hitchcock’s idea, remains welcome.

P.P.S. 2 December 2013: Ian Macdonald writes: “It’s very difficult, as you know, to trace the development of ideas such as the bomb in the briefcase/suspense-surprise thing. Stannard is surprising in that he clearly thought about how best to tell stories on screen, and came close to insights like Russian montage before those ideas became known in London (as Charles Barr has already pointed out). Unfortunately he did not continue to publish ideas after the early 20s, and his work is of course mixed up with ideas from everyone else in his ‘work group’. My picture of Stannard is built up from scraps, and his manual I have only seen in the British Library. This is tantalisingly aimed at the wannabe, so does not take ideas very far either. However, I’m sure he was aware of the prevailing doxa of play construction through such as William Archer, as others (like Brunel) were, and I’m sure that Hitch hoovered up Stannard’s ideas along with everyone else’s. As an inveterate theatre-goer, Hitch would also have been aware of ideas on suspense also. I will also have another look at my material specifically on this suspense question, for further clues, and let you know.” Thanks to Ian, Richard, and Sid Gottlieb for writing! More as things develop.

P.P.S. 5 December 2013: Oh, boy, have things developed. See the next entry.

P.P.P.S. 12 December 20113: Ashish Mehta has found evidence for the suspense-surprise duality in another eighteenth-century figure. He writes:

“Here’s what Samuel Johnson had to say in essay #3 of The Idler, published April 29, 1758, accessible here:

It has long been the complaint of those who frequent the theater, that all the dramatic art has been long exhausted, and that the vicissitudes of fortune, and accidents of life, have been shewn in every possible combination, till the first scene informs us of the last, and the play no sooner opens, than every auditor knows how it will conclude. When a conspiracy is formed in a tragedy, we guess by whom it will be detected ; when a letter is dropt in a comedy, we can tell by whom it will be found. Nothing is now left for the poet but character and sentiment, which are to make their way as they can, without the soft anxiety of suspense, or the enlivening agitation of surprise. (Emphasis added.)”

Thanks to Ashish for this!

Vertigo (1958).

David Koepp: Making the world movie-sized

Stir of Echoes (1999).

DB here:

For a long time, Hollywood movies have fed off other Hollywood movies. We’ve had sequels and remakes since the 1910s. Studios of the Golden Era relied on “swipes” or “switches,” in which an earlier film was ripped off without acknowledgment. Vincent Sherman talks about pulling the switch at Warners with Crime School (1938), which fused Mayor of Hell (1933) and San Quentin (1937). Films referred to other films too, sometimes quite obliquely (as seen in this recent entry).

People who knock Hollywood will say that this constant borrowing shows a bankruptcy of imagination. True, there can be mindless mimicry. But any artistic tradition houses copycats. A viable tradition provides a varied number of points of departure for ambitious future work. Nothing comes from nothing; influences, borrowings, even refusals–all depend on awareness of what went before. The tradition sparks to life when filmmakers push us to see new possibilities in it.

From this angle, the references littering the 1960s-70s Movie Brats’ pictures aren’t just showing off their film-school knowledge. Often the citations simply acknowledge the power of a tradition. When Bonnie, Clyde, and C. W. Moss hide out in a movie theatre during the “We’re in the Money” sequence from Gold Diggers of 1933, the scene offers an ironic sideswipe at their bungled bank job, and a recollection of Warner Bros. gangster classics. When a shot in Paper Moon shows a marquee announcing Steamboat Round the Bend, it evokes a parallel with Ford’s story about an older man and a girl. Even those who despised the tradition, like Altman, were obliged to invoke it, as in the parodic reappearances of the main musical theme throughout The Long Goodbye.

But tradition is additive. As the New Hollywood wing of the Brats—Lucas, Spielberg, De Palma, Carpenter, and others—revived the genres of classic studio filmmaking, they created modern classics. The Godfather, Jaws, Star Wars, Carrie, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and others weren’t only updated versions of the gangster films, horror movies, thrillers, science-fiction sagas, and adventure tales that Hollywood had turned out for years. They formed a new canon for younger filmmakers. Accordingly, the next wave of the 1980s and 1990s referenced the studio tradition, but it also played off the New Hollywood. For “New New Hollywood” directors like Robert Zemeckis and James Cameron, their tradition included the breakthroughs of filmmakers only a few years older than themselves.

So today’s young filmmaker working in Hollywood faces a task. How to sustain and refresh this multifaceted tradition? One filmmaker who writes screenplays and occasionally directs them has found some lively solutions.

From the ’40s to the ’10s

The Trigger Effect (1996).

David Koepp was fourteen when he saw Star Wars and eighteen when he saw Raiders. By the time he was twenty-nine he was writing the screenplay for Jurassic Park. Later he would provide Spielberg with War of the Worlds (2005) and Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008). Across the same period he worked with De Palma (Carlito’s Way, 1993; Mission: Impossible, 1996; Snake Eyes, 1998), and Ron Howard (The Paper, 1994), as well as younger directors like Zemeckis (Death Becomes Her, 1992), Raimi (Spider-Man, 2002), and Fincher (Panic Room, 2002). The young man from Pewaukee, Wisconsin who grew up with the New Hollywood became central to the New New Hollywood, and what has come after.

He spent two years at UW–Madison, mostly working in the Theatre Department but also hopping among the many campus film societies. He spent two years after that at UCLA, enraptured by archival prints screened in legendary Melnitz Hall. The result was a wide-ranging taste for powerful narrative cinema. He came to admire 1970s and 1980s classics like Annie Hall, The Shining, and Tootsie. As a director, Koepp resembles Polanski in his efficient classical technique; his favorite movie is Rosemary’s Baby, and one inspiration for Apartment Zero (1988) and Secret Window was The Tenant. You can imagine Koepp directing a project like Frantic or The Ghost Writer.

Old Hollywood is no less important to Koepp. Among his favorites are Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, and Sorry, Wrong Number. In conversation he tosses off dozens of film references, from specifically recalled shots and scenes to one-liners pulled from classics, like the “But with a little sex” refrain from Sullivan’s Travels.

It’s not mere geek quotation-spotting, either. The classical influence shows up in the very architecture of his work. He creates ghost movies both comic and dramatic, gangster pictures, psychological thrillers, and spy sagas. The Paper revives the machine-gun gabfests of His Girl Friday, while Premium Rush gives us a sunny update of the noir plot centered on a man pursued through the city by both cops and crooks.

One of the greatest compliments I ever got (well, it seemed like a compliment to me, anyway) was when Mr. Spielberg told me I’d missed my era as a screenwriter–that I would have had a ball in the 40s.

Like his contemporary Soderbergh, Koepp sustains the American tradition of tight, crisp storytelling. He also thinks a lot about his craft, and he explains his ideas vividly. His interviews and commentary tracks offer us a vein of practical wisdom that repays mining. It was with that in mind that I visited him in his Manhattan office to dig a little deeper.

Humanizing the Gizmo

Today, the challenge is the tentpole, the big movie full of special effects. A tentpole picture needs what Koepp calls its Gizmo, its overriding premise, “the outlandish thing that makes the big movie possible.” The Gizmo in in Jurassic Park is preserved DNA; the Gizmo in Back to the Future is the flux capacitor. “The more outlandish the Gizmo, the harder it is to write everybody around it.” The problem is to counterbalance scale with intimacy. “You need to offset what’s ‘up there’ [Koepp raises his arm] with things that are ‘down here’ [he lowers it].” This involves, for one thing, humanizing the characters. A good example, I think, is what he did with Jurassic Park.

Crichton’s original novel has a lot going for it: two powerful premises (reviving dinosaurs and building a theme park around them), intriguing scientific speculation, and a solid adventure framework. But the characterizations are pallid, the scientific monologues clunky, and the succession of chases and narrow escapes too protracted.

The film is more tightly focused. In the novel, Dr. Grant is an older widower and has no romantic relation to Ellie; here they’re a couple. In the original, Grant enjoys children; in the film, he dislikes them. Accordingly, Koepp and Spielberg supply the traditional second plotline of classic Hollywood cinema. Alongside the dinosaur plot there’s an arc of personal growth, as Grant becomes a warmer father-figure and he and Ellie become short-term surrogate parents for Tim and Alexa.

Similarly, Crichton’s hard-nosed Hammond turns into a benevolent grandfather; in the film, his defensive attitude toward the park’s project collapses when his children are in danger. Even Ian Malcolm, mordantly played by Jeff Goldblum (stroking some of the most unpredictable line-readings in modern cinema), can be seen as the wiseacre uncle rather than the smug egomaniac of the novel.

Crichton’s tale of scientific overreach becomes a family adventure. Koepp’s consistent interest in the crises facing a family meshes nicely with the same aspect of Spielberg’s work, and it gives the film an appeal for a broad audience. In the original, Tim is a boy wonder, well-informed about dinosaurs and skilled at the computer. Koepp’s screenplay shares out these areas of expertise, making Lex the hacker and letting her save the day by rebooting the park’s defense system. There’s a model of courage and intelligence for everybody who sees the movie.

While giving Crichton’s novel a narrative drive centered on the surrogate family, Koepp also creates a more compressed plot. For one thing, he slices out the chunks of scientific explanation that riddle the novel. The main solution came, Koepp says, when Spielberg pointed out that modern theme parks have video presentations to orient the visitors. Koepp and Spielberg created a short narrated by “Mr. DNA,” in an echo of the middle-school educational short “Hemo the Magnificent.” The result provides an entertaining bit of exposition that condenses many scenes in the book. Why Mr. DNA has a southern accent, however, Koepp can’t recall.

Compression like this allows Koepp to lay the film out in a well-tuned structure. Most of his work fits the four-part model discussed by Kristin and me so often (as here). In Storytelling in the New Hollywood, she shows how Jurassic displays the familiar pattern of goals formulated (part one), recast (part two), blocked (part three), and resolved (part four). When I visited Koepp, he was laying out 4 x 6 cards for his screenplay for Brilliance, seen above. He remarked that the array fell into four parts, with a midpoint and an accelerating climax.

For a smaller-scale example of compression, consider a classic convention of heist movies: the planning session. In Mission: Impossible, Ethan Hunt reviews his plan for accessing the computer files at CIA headquarters. As he starts, the reactions of the two men he’s recruiting foreshadow what they’ll do during the break-in: the sinister calculation of Krieger (Jean Reno), in particular, is emphasized by De Palma’s direction. Ethan’s explanation of the security devices shifts to voice-over and we leave the train compartment to follow an ineffectual bureaucrat making his way into the secured room. (The room and the gadgets were wholly made up for the film; the Langley originals were far more drab and low-tech.)

Everything that will matter later, including the heat-sensitive floor and the drop of moisture that can set off the alarms, is laid out visually with Ethan’s explanation serving as exposition. Like the Mr. DNA short, this set-piece, extravagant in the De Palma mode, serves to specify how things in this story will work. Here, however, the task involves what Koepp calls “baiting the suspense hook. “ Each detail is a security obstacle that Hunt’s team will have to overcome.

The world is too big

Panic Room.

The overriding problem, Koepp says, is that the world is too big for a movie. There are too many story lines a plot might pursue; there are too many ways to structure a scene; there are too many places you might put the camera. You need to filter out nearly everything that might work in order to arrive at what’s necessary.

At the level of the whole film, Koepp prefers to lay down constraints. He likes “bottles,” plots that depend on severely limited time or space or both. The Paper ’s action takes 24 hours; Premium Rush’s action covers three. Stir of Echoes confines its action almost completely to a neighborhood, while Secret Window mostly takes place in a cabin and the area around it. Even those plots based on journeys, like The Trigger Effect and War of the Worlds, develop under the pressure of time.

Panic Room is the most extreme instance of Koepp’s urge for concentration. He wanted to have everything unfold in the house during a single night and show nothing that happened outside. (He even thought about eliminating nearly all dialogue, but gave that up as implausible: surely the home invaders would at least whisper.) As it worked out, the action in the house is bracketed by an opening scene and closing scene, both taking place outdoors, but now he thinks that these throw the confinement of the main section into even sharper relief. The result is a tour de force of interiority—not even flashbacks break us out of the immense gloom of the place—and in the tradition of chamber cinema it gives a vivid sense of the overall layout of the premises.

Panic Room, like Premium Rush, relies on crosscutting to shift us among the characters and compare points of view on the action. But another way to solve the world-is-too-big problem is to restrict us to what only one characters sees, hears, and knows. This is what Polanski does in Rosemary’s Baby, which derives so much of its rising tension from showing only what Rosemary experiences, never the plotting against her. Koepp followed the same strategy in War of the Worlds. Most Armageddon films offer a global panorama and a panoply of characters whose lives are intercut. But Koepp and Spielberg decided to show no destroyed monuments or worldwide panics, not even via TV broadcasts. Instead, we adhere again to the fate of one family, and we’re as much in the dark as Ray Ferrier and his kids are. Even when Ray’s teenage son runs off to join the military assault, we learn his fate only when Ray does.

Less stringent but no less significant is the way the comedy Ghost Town follows misanthropic dentist Bertram Pincus (Ricky Gervais). After a prologue showing the death of the exploitative exec played by Greg Kinnear, we stay pretty much with Pincus, who discovers that he can see all the ghosts haunting New York. Limiting us to what he knows enhances the mystery of why these spirits are hanging around and plaguing him.

Yet sticking to a character’s range of knowledge can create new problems. In Stir of Echoes, Koepp’s decision to stay with the experience of Tom Witzky (Kevin Bacon) meant that the film would give up one of the big attractions of any hypnosis scene—seeing, from the outside, how the patient behaves in the trance. Koepp was happy to avoid this cliché and followed Richard Matheson’s original novel by presenting what the trance felt like from Tom’s viewpoint.

The premise of Secret Window, laid down in Stephen King’s original story, obliged Koepp to stay closely tied to Mort Rainey’s range of knowledge. In his director’s commentary, Koepp points out that this constraint sacrifices some suspense, as during the scene when Mort (Johnny Depp) thinks someone else is sneaking around his cabin. We can know only what he sees, as when he glimpses a slightly moving shoulder in the bathroom mirror.

Having nothing to cut away to, Koepp says, didn’t allow him to build maximum tension. Still, the film does shift away from Mort occasionally, using a little crosscutting during phone conversations and at the climax. During the big revelation, Koepp switches viewpoint as Mort’s wife arrives at the cabin; but this seems necessary to make sure the audience realizes that the denouement is objective and not in Mort’s head.

Once you’ve organized your plot around a restrictive viewpoint, breaking it can be risky. About halfway through Snake Eyes, Koepp’s screenplay shifts our attachment from the slimeball cop Rick Santoro (Nicolas Cage) to his friend Kevin (Gary Sinese). We see Kevin covering up the assassination. In the manner of Vertigo, we’re let in on a scheme that the protagonist isn’t aware of. This runs the risk of dissipating the mystery that pulls the viewer through the plot. Sealing the deal, Snake Eyes then gives us a flashback to the assassination attempt. Not only does this sequence confirm Kevin’s complicity, it turns an earlier flashback, recounted by Kevin to Rick, into a lie. Although lying flashbacks have appeared in other films, Koepp recalls that the preview audience rejected this twist. The lying flashback stayed in the film because the plot’s second half depended on the early revelation of Kevin’s betrayal.

Because the world is too big, you need to ask how to narrow down options for each scene as well as the whole plot. Fiction writers speak of asking, “Whose scene is it?” and advise you to maintain attachment to that character throughout the scene. The same question comes up with cinema.

Say the husband is already in the kitchen when the wife comes in. If you follow the wife from the car, down the corridor, and into the kitchen, we’re with her; we’ll discover that hubby is there when she does. If instead we start by showing hubby taking a Dr. Pepper out of the refrigerator and turning as the wife comes in, it’s his scene. Note that this doesn’t involve any great degree of subjectivity; no POV shot or mental access is required. It’s just that our entry point into the scene comes via our attachment to one character rather than another.

Here’s a moment of such a directorial choice in Stir of Echoes. Maggie comes home to find her husband Tom, driven by demands from their domestic ghost, digging up the back yard. Koepp could have gotten a really nice depth composition by showing us a wide-angle shot of Tom and his son tearing up the yard, with Maggie emerging through the doorway in the background. That way, we would have known about the mess before she did.

Instead, Koepp reveals that Tom’s mind has gone off the rails by showing Maggie coming out onto the back porch and staring. We hear digging sounds. “Oh…kay…” she sighs.

She walks slowly across the yard, passing their son and eventually confronting Tom, who’s so absorbed he doesn’t hear her speak to him.

Once you’ve made a choice, though, other decisions follow. So Maggie provides our pathway into the scene, but how do we present that? Koepp asks on his commentary track:

What do you think? Is it better to do what I did here, which is pull back across the yard and slowly reveal the mess he’s made, or should I have cut to her point of view of the big messy yard right in the doorway? I went for lingering tension rather than the sudden cut to what she sees. You might have done it differently.

Sticking with a central character throughout a scene can have practical benefits too. Koepp points out that his choice for the Stir of Echoes shot was affected by the need to finish as the afternoon light was waning. Similarly, in the forthcoming Jack Ryan, Koepp includes an action scene showing an assault on a helicopter carrying the hero. Koepp’s script keeps us inside the chopper as a door is blown off and Ryan is pinned under it. Rather than including long shots of the attack, it was easier and less costly to composite in partial CGI effects as bits of action glimpsed in the background, all seen from within the chopper.

Saving it, scaling it, buttoning it

Ghost Town.

Because the world is too big, you can put the camera anywhere. Why here rather than there?

Standard practice is to handle the scene with coverage: You film one master shot playing through the entire scene, then you take singles, two-shots, over-the-shoulders, and so on. Actors may speak their lines a dozen times for different camera setups, and the editor always has some shot to cut to. Alternatively, the director may speed up coverage by shooting with many cameras at once. Some of the dialogues in Gladiator were filmed by as many as seven cameras. “I was thinking,” said the cinematographer, “somebody has to be getting something good.”

Koepp opposes both mechanical and shotgun coverage. Whenever he can, he seizes on a chance to handle several pages of dialogue in a single take (a “one-er”). “There’s a great feeling when you find the master and can let it run.” Sustained shots work especially well in comedy because they allow the actors to get into a smooth verbal rhythm. The hilariously cramped three-shot in Ghost Town (shown above) could play out in a one-er because Koepp and Kamps meticulously prepared its rapid-fire dialogue exchange.

When cutting is necessary, Koepp favors building scenes through subtle gradations of scale, saving certain framings for key moments. He walked me through a striking example, a five-minute scene in Panic Room.

Meg Altman and her daughter Sarah have been besieged by home invaders. Meg has managed to flee from their sealed safety room, but Sarah is trapped there and is slipping into a diabetic coma while the two attackers hold her captive. Now two policemen, summoned by Meg’s husband, come calling. The criminals are watching what’s happening on the CC monitor. Meg must drive the cops away without arousing suspicion, or the invaders will let Sarah die.

Koepp’s scene weaves two strands of suspense, the peril of the girl and Meg’s tactics of dealing with the cops. One cop is ready to leave her alone, but another is solicitous. Meg offers various excuses for why her husband called them—she was drunk, she wanted sex—but the concerned cop persists. The scene develops through good old shot/ reverse-shot analytical editing, with variations in scale serving to emphasize certain lines and facial reactions.

At the climax, the concerned officer says that if there’s anything she wants to tell them but cannot say explicitly, she could blink her eyes as a signal. When he asks this, Fincher cuts in to the tightest shot yet on him. The next shot of Meg reveals her decision. She refuses to blink.

Fincher saved his big shot of the cop for the scene’s high point. The cop’s line of dialogue motivates the next shot, one that keeps the audience in suspense about how Meg will respond. What I love about this shot is that everybody in the theatre is watching the same thing: her eyes. Will she blink?

Building up a scene, then, involves holding something back and saving it for when it will be more powerful. An extreme case occurs in Rosemary’s Baby. I asked Koepp about a scene that had long puzzled me. Rosemary and Guy have joined their slightly dotty older neighbors, the Castevets, for drinks and dinner. Having poured them all some sherry, Castavet settles into a chair far from the sofa area, where the other three are seated.

Mr. Castevet continues to talk with them from this chair, still framed in a strikingly distant shot.

Koepp agreed that virtually no director today would film the old man from so far back. Can’t you just see the tight close-up that would hint at something sinister in his demeanor?

We found the justification in the next scene, the dinner. This is filmed with one of those arcing tracks so common today when people gather at a table, but here it has a purpose. The shot’s opening gives us another instance of the Castevets’ social backwardness, as Rosemary saws away at her steak. (You’d think people in league with Satan could afford a better cut of meat.)

Mr. Castevet proceeds to denounce organized religion and to flatter Guy’s stage performance in Luther. As the camera moves on, the fulcrum of the image becomes the old man, now seen head-on from a nearer position.

“He was saving it,” said Koepp. “He was making us wait to see this guy more closely—and even here, he’s postponing a big close-up.”

Yet having given with one hand, Polanski takes away with the other. Next Rosemary is doing the dishes with Mrs. Castevet while the men share cigarettes in the parlor. Because we’re restricted to Rosemary’s range of knowledge, we see what she sees: nothing but wisps of smoke in the doorway.

We’ll later realize that this offscreen conversation between Roman and Guy seals the deal over Rosemary’s first-born.

Empty doorways form a motif in the film (the major instance has been much commented on), and they too point up Polanski’s stinginess—or rather, his economy. He doles his effects out piece by piece, and the result is a mix of mystery and tension that will pay off gradually. Koepp likewise exploits the sustained empty frame, most notably at the end of Ghost Town.

Building up scenes in this way encourages the director to give each shot a coherence and a point. Koepp recalls De Palma’s advice: “For every shot, ask: What value does it yield?” Spielberg comes to the set with clear ideas about the shots he wants, and when scouting or rehearsing he’s trying to assure that the set design, the lighting, and the blocking will let him make them. As Koepp puts it, Spielberg is saying: “This is my shot. If I can’t do X, I don’t have a shot.”

Compared to the swirling choppiness on display in much modern cinema–say, at the moment, Leterrier’s Now You See Me–Koepp’s style is sober and concentrated. For him, the director should strive to turn a shot into a cinematic statement that develops from beginning to end. The slow track rightward in Stir of Echoes has its own little arc, following Maggie leaving the porch, moving past their son, concluding on Tom as she speaks to him and he suddenly turns to her (at the cut).

Accordingly a shot can end with a little bump, a “button” that’s the logical culmination of the action. Something as simple as Rosemary turning her head to look sidewise is a soft bump, impelling the POV shot of the doorway. Something more forceful comes in Stir of Echoes, when the people at the party chatter about hypnosis and the camera slowly coasts in on Tom, gradually eliminating everybody else until in close-up he says cockily, “Do me.”

Shooting all the conversational snippets among various characters would have required lots of coverage, and it was cleaner to keep them offscreen as the camera drew in on Tom. With the suspense raised by the track-in (a move suggested by De Palma), Koepp could treat Tom’s line as a dramatic turning point and the payoff for the shot.

In a comic register, the button can yield a character-based gag. Bertram Pincus is warming to the Egyptologist Gwen; he’s even bought a new shirt to impress her. They discuss how his knowledge of abcessed teeth can help her research into the death of a Pharaoh. A series of gags involves Pincus’ discomfiture around the mummy, with Gwen making him touch and smell it. The two-shot, Koepp says, is still the heart of dialogue cinema, especially in comedy.

Bertram offers Gwen a “sugar-free treat” and shyly turns away. The gesture reveals that he’s forgotten to take the price tag off his shirt.

This buttons up the shot with an image that reveals the characters’ attitudes. Pincus’s error undercuts his self-important explanation of the pharoah’s oral hygiene. Yet it’s a little endearing; he was in such a hurry to make a good impression he forgot to pull the tag. At the same, having Gwen see the tag shows her sudden awareness that Bertram’s offensiveness masks his social awkwardness. As Koepp puts it: “He bought a new shirt for their meeting, she realizes it, and she finds it sweet.” She’s starting to like him, as is suggested when she turns and matches his posture.

Koepp gives the whole scene its button by cutting back to a long shot as Pincus murmurs, “Surprisingly delightful.” Is he referring to his candy, or his growing enjoyment of Gwen’s company? Both, probably: He’s becoming more human.

Like the Movie Brats and the New New Hollywood filmmakers, Koepp is inspired by other films. And as with them, his usage isn’t derivative in a narrow sense. He treats a genre convention, a situation, an earlier Gizmo, or a fondly-remembered shot as a prod to come up with something new. Borrowing from other films isn’t unoriginal; in mainstream filmmaking, originality usually means revising tradition in fresh, personal ways.

There’s a lot more to be learned about screenwriting and directing from the work of David Koepp. He told me much I can’t squeeze in here, about the Manhattan logistics of shooting Premium Rush and about the newsroom ethnography behind The Paper, written with his brother Stephen. What I can say is this: He really should write a book about his craft. I expect that it would be as good-natured as his lopsided grin and quick wit. It would illuminate for us the range of the creative choices available in the New Hollywood, the New New Hollywood, and the Newest Hollywood.

Thanks to David for giving me so much of his time. We initially came into contact when he wrote to me after my blog post on Premium Rush, which now contains a P.S. extracted from his email. We had never met, and I’m glad we finally caught up with each other.

I’ve supplemented my conversation with David with ideas drawn from his DVD commentaries for Stir of Echoes, Secret Window, and Ghost Town. Soderbergh provides intriguing observations on the commentary track for Apartment Zero. I’ve also found useful comments in these published interviews: “David Koepp: Sincerity,” in Patrick McGilligan, ed., Backstory 5: Interviews with Screenwriters of the 1990s (University of California Press, 2010), 71-89; Joshua Klein “Writer’s Block, [1999],” at The Onion A.V. Club; Steve Biodrowski, “Stir of Echoes: David Koepp Interviewed [2000]” at Mania; Josh Horowitz, “The Inner View–David Koepp [2004]” at A Site Called Fred; “Interview: David Koepp (War of the Worlds)[2005]” at Chud.com; Ian Freer, “David Koepp on War of the Worlds [2006],” at Empire Online; “Peter N. Chumo III, “Watch the Skies: David Koepp on War of the Worlds,” Creative Screenwriting 12, 3 (May/June 2005), 50-55; E. A. Puck, “So What Do You Do, David Koepp? [2007]” at Mediabistro; Nell Alk, “David Koepp, John Kamps Talk Premium Rush, Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s Fearlessness and Pedestrian ‘Scum’ [2012]” at Movieline; and Fred Topel, “Bike-O-Vision: David Koepp on Premium Rush and Jack Ryan [2012]” at Crave Online.

Vincent Sherman discusses screenplay switching in People Will Talk, ed. John Kobal (Knopf, 1986), 549-550. My quotation from Gladiator‘s DP comes from The Way Hollywood Tells It, p. 159. For more on David Fincher’s way with characters’ eyes, see this entry on The Social Network.

The 1940s, mon amour

The Dark Mirror (1944).

DB here:

With the indispensable assistance of our web tsarina Meg Hamel, I’ve just put up an essay on Hollywood film of the 1940s. It’s called “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense.” It’s long, I warn you. But if you’re interested in American film history, thrillers, Alfred Hitchcock, or all of the above, you could find it worth checking out.

Now for a flashback. Cue track-in, soft dissolve, ominous music.

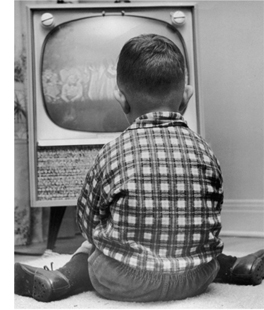

I was born in 1947, so the Hollywood cinema of that day really belonged to my parents’ generation. Yet why do I feel that the 1940s-early 1950s cinema is “my Hollywood” in a way that the 1960s and 1970s aren’t?

I was born in 1947, so the Hollywood cinema of that day really belonged to my parents’ generation. Yet why do I feel that the 1940s-early 1950s cinema is “my Hollywood” in a way that the 1960s and 1970s aren’t?

TV is a big part of the answer. Living on a farm, I saw far more movies on TV than in theatres. That’s why I don’t have as absolute a fetishism for 35mm as my baby-boom peers who grew up in cities. They could amble down to the local Bijou every day after school and soak up current movies and classics. I couldn’t, so I can sympathize with kids today who see most of their movies on monitors. That’s what I did, and—truth be told—what many urban cinephiles did too.

What I could see, thanks to Rochester and Syracuse television stations, were those films that had sold in packages of 16mm prints. Fattened out by with commercials, sometimes trimmed to fit schedules, old movies were treated as filler. And while some of the 1930s movies, chiefly the Bs featuring Mr. Moto and Charlie Chan, became lifelong favorites, it was mostly the 1940s and early 1950s films that stuck with me.

There were Citizen Kane and Magnificent Ambersons, of course, which movie books steered me toward. But there was also Ball of Fire, For Whom the Bell Tolls (in black and white), and Suspicion. Those I remember most vividly, but today, watching some obscure 40s item, I find dim memories of that sometimes flaring up too.

From college through graduate school, I made 1940s Hollywood a touchstone. My first published essay, back in 1969, was on Notorious. As a film collector, I favored 1940s things, from His Girl Friday and Fallen Angel to Ministry of Fear (below) and The Shop around the Corner. When I started teaching at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research enabled me catch up on Warners, RKO, and even the stray Monogram. In my courses we showed prizes like Meet Me in St. Louis and The Locket. I was happy when several of my students, such as Diane Waldman, Brian Rose, and Fina Bathrick, took up 1940s topics for their research.

The era pulled in my research too. In Narration in the Fiction Film my preferences were exposed; some friends noticed that most of my prime American examples (The Big Sleep, In This Our Life, Murder My Sweet, The Killers, Secret beyond the Door, Shadow of a Doubt, Rear Window, etc.) came from the 1940s and early 1950s. The conversation sort of went like this. Q: So I guess for you, David, every narrative is a mystery? A: Yes.

In The Classical Hollywood Cinema I could justify my 40s emphasis because that era saw significant changes in storytelling. I couldn’t avoid all those flashbacks, all that deep focus, all that noir and melodrama. Still, as my examples of ordinary Hollywood sound picture I picked Play Girl (1940) and The Black Hand (1949). Likewise, when I wrote an article about how we’re led to forget key story information, I fastened on Mildred Pierce. And one theme of The Way Hollywood Tells It, a book purportedly about contemporary moviemaking, is the debt that the Movie Brats and their successors owe to the 1940s.

No surprise, then, that when I was asked in 2011 to prepare some lectures for Belgium’s summer film college, I decided to revisit 1940s Hollywood. I began preparing in the spring, and had plenty of time to watch films while I was hospitalized with pneumonia. The more I watched, the more I came to believe that we still don’t know this period in its full artistic richness–and peculiarities.

True, we have plenty of studies that see all sorts of 40s films as reflections of the war or postwar malaise. Certainly, as well, the literature on film noir and the female Gothic will continue to grow. (Indeed, these categories weren’t available to people of the time; they just called those movies “melodramas.”) But I wanted to explore broader trends in cinematic storytelling that were pioneered or consolidated after 1940 or so. That meant looking at family sagas like How Green Was My Valley (see Kristin’s post here), as well as dramas like Daisy Kenyon and All About Eve and other things that caught my interest.

During a July week in Antwerp, I delivered the lectures. It was exhilarating to re-see the films in 35 and discuss them with a lively bunch of participants. But my ideas kept developing. I couldn’t shake the films and the spell they cast on me. Over two years I’ve continued to watch and read and turn ideas over.

End of flashback. Cue soft dissolve, track out, music with warmer harmonies.

I’m now writing a book, one that’s relatively short (honest!) and that, I hope, creates an original perspective on American film of the 1940s. Although the new piece centers on the suspense thriller, the book will look at other genres too. You can get the flavor of the project from these entries on the 1940s and early 1950s:

“Intensified continuity revisited.” The Shop around the Corner vs. You’ve Got Mail.

“Creating a classic, with a little help from your pirate friends.” How His Girl Friday acquired its stature today.

“Foreground, background, playground.” This is a trailer for “William Cameron Menzies: One Forceful, Impressive Idea.”

“Chinese Boxes, Russian dolls, and Hollywood movies.” On embedded flashbacks.

“Julie, Julia, and the house that talked.” On narrational strategies and wild time schemes.

“Puppetry and ventriloquism.” Bits and pieces from the 2011 lectures, focusing on anti-realism and competition among directors.

“Despoiling the movies.” On 1940s attendance habits.

“Pike’s peek.” Imaginary product placement.

“Play it again, Joan.” Analyzes the technique of replaying scenes seen or heard earlier.

“Bette Davis eyelids.” Joan’s rival and her performance tactics.

“Hand jive.” General piece on performance and gesture, with discussion of All the King’s Men.

“I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading.” A sort of dry run for the web essay.

“Alignment, Allegiance, and Murder.” How Lang attaches us to characters in House by the River.

“DIAL M FOR MURDER: Hitchcock frets not at his narrow room.” Touches on Dial M‘s debt to 1940s experiments.

“A dose of DOS: Trade secrets from Selznick.” On Selznick’s films, including those directed by Hitchcock.

“SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past.” On current thrillers’ debt to the 1940s; ties to today’s web essay.

Most of these and much of the new “Murder Culture” essay probably won’t surface in the final book. I wrote the pieces in order to clarify some research questions and to sketch out some answers. If you have any suggestions or corrections, feel free to correspond.

Meet Me in St. Louis (1944).

SIDE EFFECTS and SAFE HAVEN: Out of the past

Safe Haven; Side Effects.

DB here:

Occasionally someone will ask me how I watch a movie. Here’s a stab at an answer. If the film presents a story, fictional or nonfictional, I try to get engaged by it, as most viewers do. I also try to watch for how the filmmaker shapes sounds and images. Such things are hard to analyze on the fly, but we can at least be shot-conscious. I suppose as well there’s a small part of me asking whether what I’m watching is good or bad. Another part takes notice of what many viewers spot today: the sorts of story roles allotted to women and members of minorities.

At the same time, one module in my head seems to be looking for historical precedents and parallels to what I’m seeing. The purpose isn’t to dismiss current movies with “Aw, this has been done long ago.” Instead, I think I’m looking for ways in which earlier forms and styles are accepted, recast, or rejected by the creative choices being made today.

For instance, as I was watching Safe Haven and Side Effects, I was thinking of the 1940s.

Not that other periods haven’t left their traces. Both movies depend on crosscutting, something that goes back to the 1910s, as does the goal-oriented protagonist. Both rely as well on analytical editing, with Soderbergh in his usual spare way minimizing establishing shots in favor of compact constructive editing. The wobbly handheld shots cropping up in both films hark back to the 1960s and filmmakers’ periodic revival of them. Four-part structure: check. Rule of three: check. And so on.

But what popped out at me was something that I’ve noticed before. Films of the last twenty years or so borrow a lot of storytelling strategies that originated in the 1940s and carried through into the early 1950s.

In The Way Hollywood Tells It, I argued that 1990s Hollywood drew upon this heritage and in some ways pushed it farther. It isn’t just neo-noirs like Reservoir Dogs and Memento that owe a debt to the earlier period. Lots of films in many genres now casually use flashbacks, voice-overs, restricted points of view, multiple protagonists, network narratives, and replays of scenes from different perspectives—all strategies pioneered or consolidated in the 1940s. These techniques have become so accepted a part of mainstream moviemaking that we may forget that a comedy like The Hangover or a prestige drama like The Iron Lady presents fairly elaborate time schemes or tricks of character subjectivity.

We also tend to ignore the sheer eccentricity of the period. The 1940s introduced movies letting a house tell the story or embedding flashbacks within flashbacks within flashbacks. Characters dreamed things that came true, or realized that they were actually dead. Sometimes dead people narrated the story. All in all, things got pretty strange.

Part of that era’s legacy is the suspense thriller as we know it. I’ll be putting up a web essay on the development of the genre soon, but for now consider these two recent releases as heirs of that tradition. Of course there are big spoilers ahead.

Spooked

Like many 1940s thrillers, Safe Haven centers on a woman in peril. Most often the heroine is trapped in a house, and an unseen force or a ruthless husband is trying to kill or incapacitate her. The prototype is Gaslight (1944), where as often happens, the wife is rescued by a “helper male,” a romantic alternative to the husband. Variants of this plot include The Spiral Staircase (1946) and The Two Mrs. Carrolls (1947). This sort of domestic thriller, sometimes called a Gothic, tends to fill household spaces and everyday routines with vague threats.

Instead of confining its protagonist, Safe Haven builds its plot around a woman who has left home behind. Fleeing an abusive marriage, Erin arrives in a North Carolina town and slowly enters a love affair with Alex, a widower who runs a convenience store. Meanwhile her husband Kevin tries to track her down. The fairly conventional budding romance, as Erin joins Alex and his kids in forming a new family, is threatened by the prospect of Kevin finding her and dragging her back home. As a policeman, Kevin has unusual forces at his disposal: a crucial turning point is his putting out an unauthorized wanted poster. Not only does this endanger Erin’s new identity, but when Alex sees the poster, he breaks off their affair.

On-the-run plots are usually the province of male-centered thrillers like The 39 Steps and North by Northwest. It isn’t unknown, though, to make the woman a moving target. One of my favorites is Double Jeopardy (1999), in which Ashley Judd plays a wife convicted of her husband’s murder. When she learns that he faked his death, she realizes that she can’t be tried again for killing him. Released on parole, she pursues him, while her tenacious parole officer pursues her. An older example is Woman in Hiding (1949), in which Ida Lupino plays a wife who is supposedly murdered by her husband. Actually, she eludes death and tries to flee him, but he, discovering she’s still alive, catches up with her on a hotel staircase.

In such thrillers, there are two common ways you can generate suspense. Both depend on range of knowledge, as Alfred Hitchcock pointed out in 1947.

The author may let both reader and character share the knowledge of the nature of the dangers which threaten. . . . Sometimes, however, the reader alone may realize that peril is in the offing, and watch the characters moving to meet it in blissful ignorance and disquieting unconcern.

That is, the narration can attach us to a character and limit our knowledge to what she knows. Examples of this are Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940) and Suspicion (1941), which quite strictly confine us to the heroine’s range of knowledge.

Safe Haven, like Woman in Hiding, takes the alternative option: omniscience, or what Hitchcock calls “sharing the knowledge of the dangers.” Crosscut scenes show Erin in Southport while Kevin follows her trail. Other crosscut scenes introduce us to Alex’s problems of raising his kids and grieving for his wife.

As Erin gradually settles into the community, we know that Kevin is closing in. He arrives during a town celebration, and the crosscutting becomes tighter. Thanks to Kevin, the store catches fire and endangers Alex’s daughter, while Kevin drunkenly wrestles with Erin at gunpoint.

Suspense and mystery go hand in hand, and suspense films have a habit of suppressing information about past events. Woman in Hiding begins with the wife’s car plunging into the river; later we get a flashback explaining what led up to the accident. Safe Haven begins with a black-haired woman hysterically running out of a house and taking refuge with a neighbor. What has led to this? The woman, now a blonde, then boards a bus, while we see a man with police credentials questioning witnesses and stopping other buses.

The plot is organized so that we don’t know for quite some time why Erin is being pursued by this exceptionally zealous detective. And some fragmentary flashbacks, mostly in the form of dreams (a favorite 40s device), hint that she has killed a man. Gradually, however, there are hints that this cop isn’t what he seems. Not until the end of the third part (circa 80:00) do we learn from a full flashback that the cop is her husband. Kevin is a crazed alcoholic who began to strangle Erin one evening; she stabbed him and fled her home. The teasing flashbacks, along with the suggestion that Kevin’s pursuit is an official inquiry rather than a private vendetta, misled us. What we saw at the start was Erin escaping from an abusive marriage.

A lower-key form of delayed and distributed exposition involves Alex and his kids. Instead of filling us in immediately on Alex’s life with his wife, we learn of their married life gradually. After Alex has fallen in love with Erin, he retreats to a room kept in memory of his dead wife. He riffles through letters she left behind, to be given to Josh and Lexie when they grow up. Later, Alex abandons Erin because of the wanted poster, and he retreats to his wife’s room, where he has a change of heart and goes to bring her into the home.

Why the change of heart? An unusual aspect of Safe House is the injection of, ah, otherworldly intervention. While living in her cabin, Erin meets a neighbor, Jo, who encourages her to get to know Alex. In the epilogue, Alex gives Erin one of the letters from his wife’s desk, labeled simply, “To Her.” It’s a sympathetic message expressing the wife’s support for the next woman to be wife and mother to her family. The picture inside is of Jo. Earlier, in the sacred space of Jo’s room, Alex seems to grasp that he has to reunite with Erin. At the climax, Erin, dreams that Jo is warning her that Kevin has caught up with her. As angel, ghost, or spirit—you choose—Jo has brought everyone together.

Reviewers, in this cynical age, scoffed at this device. I didn’t mind it because I liked its tie to tradition. Ghosts and angels have haunted American cinema from the start, but in the 1940s they played very prominent roles—not just in comedies like Topper Returns (1941) but in dramas. Beyond Tomorrow (1940), Our Town (1940), Happy Land (1943), A Guy Named Joe (1943), The Uninvited (1944), It’s a Wonderful Life (1947), and many other films unashamedly introduced supernatural beings as moral guides to the living. True, those films build their spooks into the premises of the plot early on, while Safe Haven saves its for a Big Reveal. But after The Sixth Sense (1999), this sort of twist shouldn’t seem too upsetting. (A second viewing reveals that Jo is unnaturally disturbed when it looks like Erin won’t bond with the family, and a few lines of dialogue take on new meanings when you know that Jo is dead.) Perhaps the gimmick seems wimpier when it’s invoked in a romantic thriller than in a masculine investigation plot.

Recommended dosage

Steven Soderbergh is one of our most exploratory directors, a filmmaker who tries different things without making a big deal about it. He’s also a cinephile who, like Cameron Crowe, admires and quietly adapts classic studio traditions. He turns out lots of movies, a habit reminiscent of the contract director of yore.

I was skeptical of his pastiche The Good German (2006), but I do admire his compact, unfussy direction, as I mentioned here. I’m a big fan of Out of Sight (1998), and I think his last batch of films, from Contagion (2011) through Haywire (2012) and Magic Mike (2012), shows him to be a director whose every project is solid and intriguing. It’s a pity he’s announced his retirement after the upcoming Liberace project.

I doubt that in Safe Haven Lasse Hallström was consciously channeling 1940s suspense thrillers, but it seems likely that Soderbergh was trying his hand at something deliberately Hitchcockian. (Reviewers needed no nudging to make the comparison.) Beyond comparisons with the Master of Suspense, Side Effects’s debt extends to two plot patterns of the 1940-early 1950s that Scott Z. Burns’s script ingeniously combines.

The first is what I call the Crazy Lady plot. The Snake Pit (1948) is probably the clearest example, but there are many others, including Bewitched (1945), Dark Mirror (1946), The Locket (1946), Shock (1946), Possessed (1947), and Whirlpool (1950). The plot pattern can be found in literary thrillers too, such as Margaret Millar’s The Iron Gates (1945) and John Franklin Bardin’s fine Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948). Hitchcock didn’t tackle a Crazy Lady plot until Marnie (1964), but in the 1940s he tried a Crazy Gentleman variation in Spellbound (1945).

In such films, the woman is the mystery. What is wrong with her? Why do her problems have such horrible consequences for her and others? Often the woman displays an abnormal division in her mind: the prospect of a split personality is never far off. The key factor is that her behavior is inconsistent. A rich woman shoplifts (Whirlpool), a sweet girl fatally stabs her fiancé (Bewitched). Accordingly, only a psychoanalyst can probe the sick woman’s behavior and track down the founding trauma, typically something that happened in childhood. A crucial convention is the scene in which the woman breaks through and realizes what ails her, as in this moment from Whirlpool. It’s typical of this plot that therapeutic dialogue is often paralleled by police questioning.

Side Effects gives the Crazy Lady’s mental problems a modern spin. Emily is suffering from depression, and her husband Martin’s recent release from prison hasn’t helped her recover. After ramming her car into a parking-garage wall, she’s cared for by Jonathan, a hospital psychiatrist also in private practice. He starts her on antidepressants, eventually giving her one recommended by Emily’s previous psychiatrist, Victoria. This seems to help, although it induces Emily to sleepwalk. While she’s apparently sleepwalking, she stabs Martin to death.

Now Jonathan is in a bind. If the drug Ablixa has been misprescribed, Jonathan is responsible for Martin’s death and Emily’s fate. Jonathan defends Emily and his testimony helps win a verdict of not guilty by reason of insanity. He continues to supervise her recovery while his career collapses. His patients abandon him, his partners cast him out of their business, and he’s dropped from a lucrative experiment. He’s also being investigated by his professional association.

In other words, Jonathan is now fulfilling a second 1940s plot pattern: The innocent man trapped by circumstance. He might be a murder suspect (Stranger on the Third Floor, 1940; Phantom Lady, 1944; The Big Clock, 1948) or an ordinary guy dropped into international intrigue (Journey into Fear, 1943; The Ministry of Fear, 1944). Side Effects combines this noirish convention with the Crazy Lady plot. It turns out that Emily and Victoria have conspired to set up Martin’s death. Emily actually hates her husband, and she’s learned enough from his insider-trading schemes to understand that a scandal could drive down Ablixa’s stock price. She and Victoria, who have become lovers, can make millions as a result of the murder.

Yet suspecting all this doesn’t help Jonathan. Emily can’t be tried again, and as Jonathan begins to grasp their scheme, Victoria draws the net tighter around him. She sends his wife faked photos suggesting that he and Emily have had an affair.

In 1947, novelist Mitchell Wilson pointed out an important convention of the thriller. He claimed that the defining feature of the genre was a fear felt by the protagonist that is communicated to the reader: the protagonist is in continual danger. But when the threat reaches its peak, the worm must turn.

The framework of the suspense story is the continual struggle of the frightened protagonist to fight back and save himself in spite of his pervading anxiety, and in this respect he is truly heroic. The action of the story does not consist in mere activity, but in the hero’s change of mood in response to changing circumstances.

Jonathan’s desperation leads him to concoct a scam of his own. Since Emily is in prison and can’t communicate with Victoria, he is able to play them off against one another. Holding a physician’s control over Emily, he can convince her to double-cross Victoria and unmask her. Then he double-crosses Emily and consigns her to the asylum while returning to his family.

Again, I’ve ironed out the ups and downs of the film in order to lay out the plot’s design. In the actual telling, we’re attached first to Emily and then more closely to Jonathan. The overall pattern resembles that of Whirlpool, which concentrates first on the way the wife’s kleptomania draws her to the sinister therapist Korvo, and then shifts to the investigation undertaken by the police and her husband, a psychoanalyst. (Whirlpool, like Side Effects, centers on dueling shrinks.)

Here the Crazy Lady premise is a masquerade, and Soderbergh “plays fair” with us about it. The 1940s films rely on mental subjectivity—voice-over inner monologues, exaggerated sound effects, hallucinations, dream imagery—in order to show that the protagonist is truly wacko. Side Effects presents Emily objectively, relying on somber color schemes, top lighting, and Rooney Mara’s morose demeanor to suggest a young woman struggling against depression.

From the outside we watch Emily’s glum visits to Martin in prison, their frustrated sex when he gets out, her impassive crashing of her car, her confiding in her boss, and her breakdown at a cocktail party. There are a few optical POV shots, but those are justified as Emily’s numb stare–although Soderbergh does sneak past us a POV shot that, because of distorting glass, might seem to be projecting Emily’s state of mind expressionistically. (See above.) Virtually everything we see suggests a woman losing control, so that when Emily perks up after going on Ablixa, we, like Jonathan and Martin, think she’s recovering.

Safe Haven leads us to jump to a conclusion—that the cop pursuing Erin is doing so legitimately—only to rescind that by filling out the teasing fragmentary flashbacks. Side Effects does something similar, but through simple ellipsis. The plot lets us think that Emily is genuinely depressed by skipping over things it could have shown, such as her fake vomiting or her dumping the prescription pills down the toilet. Only at the climax, when Jonathan wrings the truth from Emily, do we get subjective imagery. There are artificially sun-sprayed flashbacks of her days with Martin just before his arrest, as well as glimpses of her therapy with Victoria, followed by replays of the suicide attempts, now revealed as faked.

The 1940s popularized this sort of filling-in flashback, in which a replay shows items that were left out of an earlier presentation. The most famous example is the return to the opening of Mildred Pierce (1945). Now as then, we can’t completely trust a thriller’s narration. There are mysteries in the story, but there are also mysteries in the storytelling. No matter how much a thriller seems to tell us, key information is usually held back, and the suppression won’t always be signaled. To get Rumsfeldian: there are always known unknowns, but thrillers trade in unknown unknowns, data we didn’t realize were there.

There’s a lot more to say about these movies. For example, both trade on a premise common to the 1940s and American movies thereafter. Call it the Margaritaville Rule: There’s a woman to blame. Erin brings calamity to Southport and trauma to her would-be family, and Jonathan’s travails are the result of two scheming women, seconded by a hard-edged wife who won’t hear out his explanations.

Moreover, I hope it’s clear that I don’t think these two recent releases are merely cloning 1940s conventions. They incorporate subjects and themes of our time, like spousal abuse and the insidious power of Big Pharma. They exhibit some innovative plotting, such as the revelation of a guiding spirit in Safe Haven and the combination of Crazy Lady premises with the Cornered Innocent in Side Effects. And Soderbergh’s offers an exercise in crisp direction, from its conventional opening shot to its grimly symmetrical closing one.

My point is simple: However new our films may seem, whether they’re accomplished (Side Effects) or banal (Safe Haven), in important respects they’re continuing traditions that go back decades.

Why then, you may ask, do so many academics and journalists insist that classical cinematic storytelling is dead? Why do they so resolutely ignore the evidence of continuity between today’s films and those that went before? That’s a mystery I can’t solve.

Hitchcock’s remark about the range of knowledge and suspense comes from “Introduction: The Quality of Suspense,” Alfred Hitchcock’s Fireside Book of Suspense (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1947), viii. Mitchell Wilson’s remarks on fighting back are in “The Suspense Story,” The Writer 60, 1(January 1947), 16. His novel None So Blind (1945) became the Renoir film Woman on the Beach (1947).

The idea of the “helper male” in the Gothic is developed by Diane Waldman in “’At last I can tell it to someone!’: Feminine Point of View and Subjectivity in the Gothic Romance Film of the 1940s,” Cinema Journal 23,2 (Winter 1984), 29-40.

For more background on the 1940s thriller, see the web essay, “Murder Culture: Adventures in 1940s Suspense” and this blog entry. Another blog entry discusses replays in 1940s and 1950s American film. For more arguments about the debts of today’s films to studio Hollywood, see The Way Hollywood Tells It and other entries on this site. I analyze the duplicitous opening of Mildred Pierce, along with its revelatory replay, in this entry and its accompanying video.

Today’s entry neglects another important component of Side Effects: the music. For that, see Roger Ebert’s acute review. Expressive scores are, needless to say, central to 40s thrillers too.

Mike Grost’s encyclopedic website supplies a great deal of information about the mystery genre.

Side Effects.

P. S. 24 March 2013: Thanks to Gabe Klinger for correcting a dumb date mistake!