JCC

Friday | September 9, 2011 open printable version

open printable version

The Milky Way (La Voie lactée, 1969)

DB here, writing from a gray Brussels:

All the problems of a film are in the script.

When a film is made, the screenplay disappears.

When you consider what a scene needs to express, ask: How can the actor act it?

When you’re writing a scene, try to act it out yourself.

Rather than letting dialogue explain the action, let the action explain the dialogue.

It will always be possible to make films. Don’t forget to make cinema.

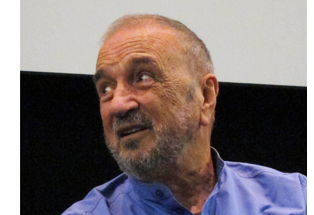

These and other epigrammatic insights flowed easily from Jean-Claude Carrière during his visit to the Cinematek of Belgium and the annual conference of the Screenwriting Research Network. I hope to devote a later blog to other attractions of this stimulating get-together. For now, a brief tribute to the volcanic charm of the legend known as JCC.

JCC entered cinema under the aegis of Jacques Tati. Tati wanted someone to turn M. Hulot’s Holiday and Mon Oncle into novels, and the very young writer seemed the right candidate. But Tati quickly learned that JCC didn’t know how a film was made. So he assigned Pierre Etaix and the editor Suzan Baron to tutor the lad in the ways of cinema. First lesson: Go through M. Hulot on a flatbed viewer, examining the script line by line while watching shot by shot. As a result, JCC says, he began to understand “the film that you don’t see.”

In the course of his career, JCC has written novels, plays, essays, screenplays, even a scenario for a graphic novel. In the process he became one of the most distinguished and respected screenwriters of the last fifty years. His most famous collaborations were probably with Buñuel, from Belle de Jour (1967) to the master’s last film, That Obscure Object of Desire (1977). He worked with Etaix (The Suitor, 1962), Forman (Taking Off, 1971), Schlöndorff (The Tin Drum, 1979), Godard (Every Man for Himself, 1980), Wajda (Danton, 1983), Oshima (Max mon amour, 1986), Kaufman (The Unbearable Lightness of Being, 1988), Peter Brook (The Mahabarata, 1989), Malle (Milou en Mai, 1990), and Haneke (The White Ribbon, 2007). He has also become known for his work on major French costume pictures and adaptations, such as Cyrano de Bergerac (1990) and The Horseman on the Roof (1995), as well as work with younger directors, including Wayne Wang (Chinese Box, 1997) and Jonathan Glazer (Birth, 2005). His TV scripts are numberless.

Directors both young and old come to him for the unique forms of collaboration that he offers. Instead of going off to write the screenplay, JCC meets frequently with the director. (Sometimes the director stays in his house.) He might ask the director to write the script for him, and they go over the result. Through these methods, JCC tries to help the director “find the film that he wants to make.” But his methods are flexible, tailored to the director’s temperament. When he was working with Buñuel, the men met daily to tell each other their dreams, some of which wound up in The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972). Similarly, JCC prefers to meet with the actors before production, letting them try out the parts so that he can revise things for each one’s habits of speaking. For Cyrano, Depardieu read the entire play aloud, taking all the parts, and then listened to it over and over on cassettes to refine his interpretation.

Brussels gave JCC a busy twenty-four hours. In conversation with the critic Louis Danvers he introduced a Cinematek screening of The Milky Way. He gave a keynote address for the Screenplay Network conference, and he participated in a panel discussion with members of the Flemish Screenwriters Guild at the film school RITS. These sessions ranged freely over his career and his conceptions of filmmaking. He believes that there is a language of film that sets it apart from other arts. That language is grounded in the play of meaning and emotion that comes from putting one shot after another.

He explained the point through an example that seems at first to be a restatement of the classic Kuleshov effect. In Shot 1, a man in his apartment looks out the window. Shot 2: The street. A woman is walking with another man. We’ll assume that our man is seeing them. Shot 3: Our man reacts.

But contrary to Kuleshov’s dictum, his facial expression should not be neutral. In fact, his expression tells us how to understand the scene. If the man looks upset, we surmise that he’s jealous. If he’s benevolent, we assume that the woman is a friend, his daughter—or a flirt. The filmmaker needs not only techniques like framing and cutting, but also the performances of actors.

Now cut to the woman in her bedroom brushing her hair. We need to make sure the audience understands that it’s the same woman, so maybe we have to go back and add a shot to the earlier scene, a closer view of her in the street. This constant flow and readjustment of images is based on guiding the spectator discreetly but firmly through the action. The audience isn’t aware of this “secret film,” but it governs everything the viewer thinks and feels.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

For this reason, the young screenwriter needs to learn everything about how a film is made. When JCC was acting in The Wedding Ring (1971), a film starring Anna Karina, he learned that simply getting up from a couch can be a complicated matter. When he stood up spontaneously, dipping forward to lift his body, the cinematographer had to correct him: It looked awkward on film. JCC learned that he had to stand up in an unnatural way, with his feet spaced and his back rigid, so that it looked smooth on film. The screenwriter must know that even the smallest moment of action, easy to write in the comfort of a study or a café, is subject to the contingencies of production.

Where to get ideas for films? From the classics, of course. (“Balzac is the greatest screenwriter—every character is vivid.”) But above all you must observe reality. Tati taught JCC to sit vigilantly in a café. Study everyone who passes. Notice details. Imagine the person as a character in a story. Give him or her some motivations. What you must do is “find the fiction in the reality.” When JCC presided over the French film school La FEMIS, he promoted an exercise that required students to move out into a public space, like a market, and come back with stories about the people they saw. JCC praised Tati’s genius for spinning gags and situations out of passing life—“as if God had created the world so that it could furnish a film by Jacques Tati.”

JCC must be one of the few screenwriters who doesn’t gripe about his work being changed in its final incarnation onscreen. He sees the screenplay as ephemeral, the chrysalis for the butterfly. Once you accept the fact that your text must be sloughed off on its way to becoming cinema, you can take joy in your work. For young people, JCC advised the same relaxed, exploratory attitude. Conceive of yourself as a writer, able to move across media. The venues for your writing are constantly changing, so be prepared to write for television as well as film, to write comics and documentaries and plays. Above all, “Don’t despair of the future of cinema. It’s wide open.”

Jean-Claude Carrière turns eighty next week.

The best introduction to Carrière’s career and ideas that I know is his book The Secret Language of Film (Faber, 1995). Some of this text overlaps with Exercice du scénario (FEMIS, 1990), coauthored with Pascal Bonitzer. That book is worth reading too, but it hasn’t to my knowledge found English translation. An illuminating interview is here.

P.S. 11 September 2011: Thanks to Jonathan Rosenbaum for correcting an error in JCC’s filmography, which I’ve rectified above. Jonathan also remarks:

I assume that you know, by the way, that Carrière appears in a scene of Certified Copy, playing something similar to the “wise old guru” role played by the Turkish taxidermist in Taste of Cherry and the doctor in The Wind Will Carry Us.

I did know and should have worked it in!

P.P.S 22 September 2011: A panel discussion with Jean-Claude Carrière held during the conference is available here. Although the site is in Dutch, the discussion is in English. Thanks to Ronald Geerts for the information.

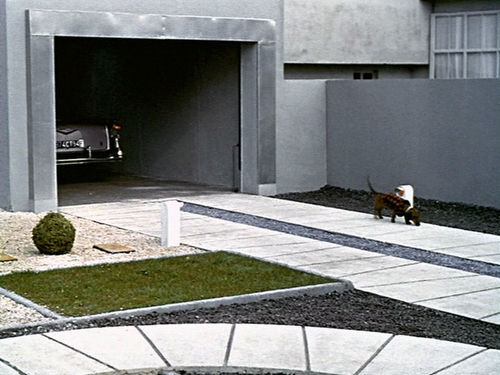

Mon Oncle (1958). “I followed Tati more or less everywhere, usually with Etaix, attending projections followed by long anxious discussions. (‘Can we clearly see the dog’s tail go past the electric eye that shuts the garage door? Yes? Clearly? You’re sure people will see it?’)