Archive for the 'The Ten Best Films of…' Category

The ten best films of … 1923

Le brasier ardent.

Kristin here:

Six years ago David and I celebrated the 90th birthday of the classical Hollywood cinema with a post that included a list of what we considered the ten greatest (surviving) films of 1917. Choosing the ten best films of 90 years ago has become a custom, one which helps us avoid doing a ten-best list for the current year. It’s a way of drawing attention to some wonderful but often little-known films, for those who are interested in exploring the treasures of silent cinema.

For previous entries, click here: 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, 1921, and 1922.

For some reason, that 1917 list was pretty easy to put together. In recent years, I’ve had more trouble. As I wrote last year, “For the past two years, I’ve noted that it was difficult to fill out the list of ten masterpieces. I keep thinking that I’ll get to a year where I won’t have to say that, but 1922 turns out not to be that year. Some titles were obvious, but the last one or two took some hunting.” Well, 1923 still isn’t that year. I’ve again had some trouble filling out the top ten.

Why? 1923 should be packed with worthy candidates. But oddly, some of the most significant directors of the era didn’t make films that year. This seems to have been partly because success brought greater ambitions. In 1923 Fritz Lang was preparing his epic two-part Die Nibelungen, guaranteed to show up in next year’s list. Abel Gance had embarked the long road to the release of Napoléon, four years later.

Carl Dreyer, who had made three films in 1919 and two each in 1920 and 1921, was bouncing around among companies and countries in the mid-1920s, and didn’t again release anything until his 1924 German-produced film, Michael.

Others made relatively unremarkable films. F. W. Murnau’s surviving film from 1923, Die Finanzen des Grossherzogs, serves mainly to prove that comedy was not his strong suit. Victor Sjöström’s Eld ombord (The Hell Ship) doesn’t match the masterpieces we find elsewhere in his career. Louis Feuillade’s 1923 feature Le Gamin de Paris is likewise unexceptional, though it’s of interest for showing his abandonment of complex staging and his conversion to American-style cutting, including angled shot/reverse-shots. (Of Feuillade’s 1923 installment film Vindicta, we can’t speak; we haven’t been able to see it.)

Other films are lost. John Ford made four films that year, only one of which survives: an incomplete, beat-up version of Cameo Kirby that doesn’t make it look like anything special. Murnau’s first 1923 film, Die Austreibung, seems to be gone. Mauritz Stiller’s The Blizzard is lost, and he, too, was probably already involved in his own 1924 two-part epic, The Saga of Gösta Berling.

[December 29: Brian Darr tweets that The Blizzard is not lost, which I am glad to learn. Its Wikipedia entry confirms that it is only partially lost, with about two-thirds of the film known to be preserved.]

Finally, the Soviet cinema, which was to make such major contributions to 1920s cinema, had not yet gotten off the ground.

Still, with some help from David, I’ve concocted a list with some great films and some near-great ones. The place to start was obvious.

From the ridiculous to the sublime

Some years now we’ve been watching the careers of Charles Chaplin, Harold Lloyd, and Buster Keaton delivering wonderful short films and inching toward even greater things. This was the year they blossomed.

Chaplin made a charming short feature, The Pilgrim, this year, but he also surprised everyone by making a sophisticated sex comedy (appearing only in an unrecognizable cameo as a porter). The title role of A Woman of Paris features Chaplin’s regular leading lady, Edna Purviance, as a village girl, Marie, who loses her young boyfriend Jean through a misunderstanding. She runs off to the city to become a rich man’s mistress and realizes too late what she has lost.

The plot centers largely around this romantic triangle and Marie’s indecision about whether to return to her boyfriend, who has become an impoverished artist in Paris, or to stay in the luxurious life that Pierre provides her. The affair between Marie and Pierre is handled in a sophisticated and yet subtle way. There are no love scenes, but at one point Pierre finds himself without a handkerchief and goes into the bedroom to pluck one casually out of drawer. Clearly he spends a lot of time in their love nest.

At the same time, the film deals more generally with the gulf between the very wealthy and the working-class people who who serve them. In one well-known scene, a woman gives Marie a massage, and the camera stays mainly on the masseuse as she tries to maintain a neutral expression while obviously being shocked by the lurid gossip between Marie and a friend. In another, a kitchen assistant in a swanky restaurant cannot bear the odor of the aging game bird he has to fetch for the chef, but the chef and Pierre consider it a prime delicacy.

At the same time, the film deals more generally with the gulf between the very wealthy and the working-class people who who serve them. In one well-known scene, a woman gives Marie a massage, and the camera stays mainly on the masseuse as she tries to maintain a neutral expression while obviously being shocked by the lurid gossip between Marie and a friend. In another, a kitchen assistant in a swanky restaurant cannot bear the odor of the aging game bird he has to fetch for the chef, but the chef and Pierre consider it a prime delicacy.

One of the strengths of the film is that it does not take the obvious approach of making Pierre into a fat, obnoxious oaf. On the contrary, Adolphe Menjou plays him as a witty, unflappable figure. He thinks nothing of arranging a marriage with a rich woman while planning to carry on his affair with Marie, but he puts up with her shifting moods and does genuinely seem to love her. The touch of having him play his saxophone while Marie has a tantrum and orders him out (right) typifies the light touch Chaplin applies to what is ultimately a tragic story.

A Woman of Paris was not well received upon its release, at least by the ticket-buying public, who expected a Chaplin film to star the Little Tramp and to be straightforwardly funny. The title at the beginning, where Chaplin explains that he does not appear in the film undoubtedly did little to appease them. Many critics were respectful, however, and other filmmakers recognized the new type of sophisticated comedy that he had introduced. Lubitsch, who was working on Rosita at the same studio, United Artists, was definitely influenced by it–as we shall see next year when his The Marriage Circle figures in the top ten of 1924. That film includes Menjou, playing a similar role, and in fact after playing minor roles for nearly ten years, he became a star with Chaplin’s film.

[February 10, 2014: Paul Duncan, Film Book Editor for Taschen, has kindly supplied figures showing that A Woman of Paris was profitable, if not as much as Chaplin’s other films: “It earned United Artists $634,000, of which $608,868.91 went to Regent Film (the company Chaplin formed to produce films for Edna Purviance). So with a production cost of $351,853.03, A Woman of Paris made a healthy profit, though, as you write, obviously it would have been more if it had been a comedy starring Chaplin.” Paul also informs me that Taschen’s The Charlie Chaplin Archives, which he is editing, will be published later this year.]

By 1923, Harold Lloyd had already done some shorts featuring nail-biting but hilarious comedy high up on skyscrapers. (See High and Dizzy in our 1920 entry.) In 1923 he took the same sort of premise into the feature-length Safety Last and created an indelible image: a brash young man hanging from a tilting clock. The gags go on story by story. After surviving the clock, Harold manages to get to the next level, only to be chased out a flagpole by a dog (left). Looking back, people tend to remember the vertiginous climb as the whole film, though remarkably, it takes place only over the last third. Earlier scenes involve a romance and misunderstandings that arise from the hero’s job at a department store.

By 1923, Harold Lloyd had already done some shorts featuring nail-biting but hilarious comedy high up on skyscrapers. (See High and Dizzy in our 1920 entry.) In 1923 he took the same sort of premise into the feature-length Safety Last and created an indelible image: a brash young man hanging from a tilting clock. The gags go on story by story. After surviving the clock, Harold manages to get to the next level, only to be chased out a flagpole by a dog (left). Looking back, people tend to remember the vertiginous climb as the whole film, though remarkably, it takes place only over the last third. Earlier scenes involve a romance and misunderstandings that arise from the hero’s job at a department store.

Safety Last wasn’t Lloyd’s greatest film, but it launched the greatest period of his career. He’ll probably be joining us for these nostalgic lists every year now until 1927. The film is still available as part of New Line’s big box set of Lloyd’s films on DVD. (Buy that one, and you’ll be a step ahead of those future lists.) This summer the Criterion Collection brought Safety Last out on DVD and Blu-ray. There’s only that one feature on the disc, but it includes several supplements, including three newly restored Lloyd shorts and Kevin Brownlow’s 104-minute documentary, The Third Genius.

Keaton, too, entered a hugely creative streak in 1923. He made an amusing satire on Intolerance, the feature-length The Three Ages, in which Buster traces love through the stone age, the Roman era, and the Roaring Twenties. As Keaton himself acknowledged, “Cut the film apart and then splice up the three periods, and you will have three complete two-reel films.” He followed it up, however, with a masterpiece that displayed a complete command of story structure in the classical Hollywood mold: Our Hospitality. It’s arguably as fine as anything he ever made, except The General, which just edges it out.

Interestingly, Our Hospitality and The General are Keaton’s only two period pieces. (that is, if one excepts The Three Ages, which is far more farcical and does not attempt to recreate a realistic period atmosphere.) Both also take place in the South, and outdoors to a considerable extent. The milieu seems to have inspired him. Dealing with old-fashioned trains and other technology generated a lot of clever gags, and the fields, forests, and rivers helped give these two films a pictorial beauty that separates them from the Keaton’s other films.

Way back in 1978, when David and I were working on the first edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we wanted to include an extended analysis of a single film in each of the chapters on film technique. For mise-en-scene we chose Our Hospitality, which contains numerous uses of setting, costume, acting, and lighting brilliant enough to inspire a teacher and straightforward enough for students to notice and understand. Plus what better way to win over students who think that old black-and-white silent movies aren’t worth watching?

The story is simple. Willie McKay, the hero, travels from New York to the deep South, under the impression that he has inherited a mansion. The trip south on a very old-fashioned train supplies a long string of marvelous sight gags. There Willie meets the heroine, who shares his coach. Upon arrival, Willie discovers that his “mansion” is really a decaying house. Since the heroine has invited Willie to dinner, he wanders around to pass the time, unaware that he has inherited something else: a feud. The heroine’s family has a longstanding grudge against the McKays, and the father and two brothers are determined to shoot Willie. The only catch is that Southern hospitality dictates that they cannot kill him while he’s in their home.

In our analysis in Film Art, we pointed to the many motifs Keaton uses in service of the narrative, such as the moment of the hero’s rescue of the heroine as an echo of the earlier fishing pole/waterfall gag. One stylistic motif of staging comes back several times: Keaton using foreground doors or walls to create depth staging of moments when people spy or eavesdrop on others. In the frame on the left below, one of the brothers waits to ambush Willie, who is unaware of his presence (or indeed of the feud itself). In the one on the right, Willie eavesdrops on the brothers in their house, learning that they intend to kill him but that he is safe inside the house. Now Willie learns what’s going on, while the brothers don’t realize that he’s overhearing their plan. Such compositions are a motif in the film, forming a way of manipulating the narration–usually giving us more information than the characters onscreen have.

Like Safety Last, Our Hospitality ushered in the prime of the comedian’s career. Keaton made a string of marvelous features that lasted until The Cameraman in 1928. He didn’t always sign the films as director (he’s listed as co-director of Our Hospitality, along with John Blystone), but his unerring sense of how to compose images for the entire frame, both its surface composition and in depth, suffuses all his films of this period.

I’ve mentioned that Lubitsch was working at United Artists in 1923. Rosita was his first American film, starring Mary Pickford. It’s certainly not a masterpiece on the level of The Marriage Circle or Lady Windermere’s Fan, but Rosita is a charming and impressive film, certainly at least as good as Lubitsch’s other lesser films of the decade, Forbidden Paradise and Three Women.

As I discuss in my book, Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, the director had already been tentatively using classical Hollywood style in his last two German films, Das Weib des Pharao and Die Flamme. In Rosita, he managed to balance a typical historical epic from his German period (Madame Dubarry, Anna Boleyn) with the light, vivacious appeal of his star. She plays the title character, a cheerful street musician who is in love with Don Diego, an impoverished nobleman and military officer. Rosita catches the eye of the lecherous king. Don Diego ends up condemned to death, and Rosita plots to save him.

The sets were built on the enormous backlot of United Artists, where Douglas Fairbanks’ castle for Robin Hood had stood. The day after Rosita wrapped, the construction of the sets for The Thief of Bagdad began on the same lot. Indeed, one can detect a distinct similarity between Rosita’s big sets–city streets and a large prison–and those of the two Fairbanks films. This frame is a shot of the prison interior emphasizing a gallows in the background:

Given that this giant set was built in the open air, Lubitsch must have filmed this and other scenes at night, using the giant arc spotlights that had recently become a standard tool of Hollywood filmmaking to throw great swathes of illumination across the scene. In general, Rosita‘s style demonstrates that by 1923, Lubitsch had come fully to understand the American approach.

As a vehicle for Pickford, the film also is skillfully done, permitting her numerous intimate scenes that show off her charm. Given her star persona, the dramatic situation is leavened with humor in the interior scenes. Rosita’s poor family, a large, rowdy bunch, provides much of this, as when Rosita brings home a perfumed handkerchief and the impressed parents and children in turn bury their noses in it and sniff deeply. Rosita’s reactions to the King’s attempts to seduce her are also somewhat comic, though there is definitely a threat hanging over the situation.

Unfortunately, like all too many of the films on this year’s list, Rosita is difficult to see. It seems to have survived only in a Russian print, and a rather contrasty, worn one at that, as the frame above demonstrates. As long as that is the sole available material, a restoration might be too daunting. Still, in this day of digital manipulation, perhaps something could be done to improve the image quality. I hope at some point it will become available on home video. That also goes for Lubitsch’s other somewhat lesser films of the mid-1920s, Forbidden Paradise and Three Women.

Rosita’s reputation has suffered from strange statements Pickford much later made to Kevin Brownlow and which he published in The Parade’s Gone By. There she claims she and Lubitsch did not get along and that the resulting film was bad and a commercial failure. With the film itself unavailable for viewing, Pickford’s condemnation was accepted at face value. In fact, documents in the United Artists archive at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research overturn Pickford’s supposed dislike for Lubitsch. For years she tried to find financing to make another film with him, and in 1926 she called upon him for help in editing Sparrows. With the discovery of the Soviet print, it becomes apparent that Rosita was far from the disaster Pickford later claimed. Why her memories of her work with Lubitsch became so distorted late in her life we shall probably never know.

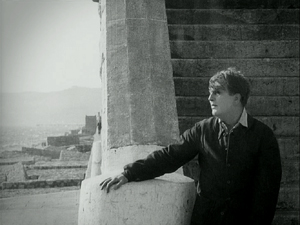

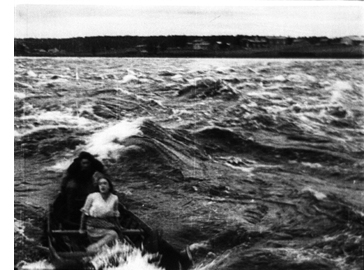

Overshadowed masters of French Impressionism

Abel Gance’s flashy La roue (on last year’s list) gets a lot of attention these days. He’s the high-profile representative of Impressionism. Yet 1923 saw the first fiction films from the director who was the movement’s modest heart: Jean Epstein. The very first, L’auberge rouge (“The Red Inn”) is a lovely film, but Cœur fidèle (“Faithful Heart”) epitomizes the quiet side of Impressionism. It’s story is as simple as they get: Marie is a barmaid whose foster parents try to force her to marry a thug, Petit Paul, while she is in love with the sensitive dock-worker Jean. The scenes around the waterside and the famous sequence in a carnival are all done with a realism blended with the subjective camera techniques that convey the characters’ thoughts, perceptions, and feelings in a way that was fresh at the time.

The exteriors were shot around the docks of Marseille, and Epstein uses superimpositions of the ocean to convey the lovers’ longing. Waves are sometimes superimposed over their figures, or one will look into the water and see the other’s face there, as when Jean envisions multiple images of Marie:

Shooting into a distorting mirror, Epstein uses the conventional Impressionist indicator of drunkenness as Petit Paul looks at a woman next to him in a bar:

Coeur fidèle has been released in the UK (Region 2) as a DVD/Blu-ray combo in Eureka!’s Masters of Cinema series. (This includes a helpful little booklet with excerpt from Epstein’s writings and a review of Cœur fidèle by René Clair.) It is also available as a Region 2 French DVD without English subtitles. As these frames indicate, the film survives in beautiful condition.

Along with La roue, Cœur fidèle proved hugely influential. It used the “unfastened camera” that later was credited to Murnau in The Last Laugh. Like Murnau, Hitchcock picked up Impressionist style, as reflected most obviously in his 1927 boxing film, The Ring. Hitchcock’s penchant for moving camera and subjectivity never went away. Hollywood, too, picked up the subjective techniques of Impressionism, especially in the 1940s films that David is studying now.

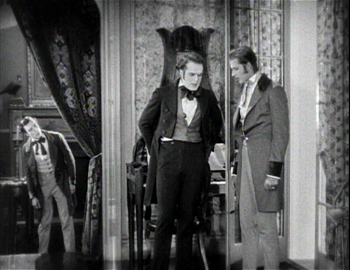

Unlike Cœur fidèle, Le brasier ardent (“The Burning Crucible”) was sophisticated, convoluted, and perplexing. It was one of two films directed in France by the Russian actor Ivan Mosjoukine for the émigré film company Albatros. (The earlier one is L’Enfant du carnaval, 1921; as far as I know, no print survives.) Earlier this year, upon the release of Flicker Alley’s box set of five Albatros films, I described Le brasier ardent:

It has a reputation as an audacious, surrealist, and almost incomprehensible film. This may be due to the fact that prints available in archives during the 1970s and 1980s lacked intertitles. The opening nightmare sequence is indeed disturbing, but at least with intertitles, we understand that it is only a dream. It begins with a wild-eyed man tied to a stake where he is about to be burned. The heroine stands looking on, resisting as the man pulls on her long hair, apparently intent on dragging her into the fatal flames to accompany him in death. Subsequent scenes of the nightmare show the heroine encountering different men, all played by Mosjoukine, culminating in a man in evening dress stalking her along a vaguely Expressionist street until she escapes and wakes up in bed.

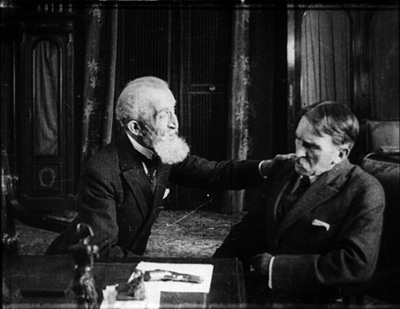

This nightmarish opening must have established vivid expectations in the spectators of 1923 as to what sort of film they were in for. After the heroine wakes up, however, what follows is quite different. The main plot is a stylized but quite amusing comedy. The heroine is a pampered wife, married to a rich man whom she does not love. She is faithful, but he is unreasonably jealous. He goes to a distinctly odd detective agency, one department of which is “Recovery of Lost Wives” (above), with “Success guaranteed!” and “Nothing to pay in advance!” Juxtaposed with the bizarre opening, this quirky humor might have eluded puzzled audiences of the day. Certainly the film itself was a failure, and Mosjoukine stuck to acting thereafter.

Unfortunately for the husband, Detective Z, whom he picks from the eccentric group pictured above, is the very man, again played by Mosjoukine, whom his wife has dreamed about. What follows is an odd tale with the detective and wife gradually falling love. Mosjoukine, known for his tragic, intense characters in the Russian cinema, plays such figures in the fantasy sequences–but in the main story he is allowed to play for laughs, gamboling and rolling on the floor like a puppy when the wife finally appears at his mother’s apartment and declares her love for him.

Mosjoukine should not, however, be allowed to overshadow his co-stars, Ermolieff actors who were also were to make their way into the wider French production of the day, including Impressionism. The wife is played by Nathalie Lissenko, one of the stars of the pre-Revolutionary cinema, who had acted opposite Mosjoukine in Russia. Among her 1920s roles was the protagonist of one of Epstein’s finest films, the largely unknown L’Affiche (1924). The husband is Nicolas Koline, who started his career with Ermolieff only after the company had left the Soviet Union. He will be familiar to silent-film fans from his performance as Tristan Fleury in Gance’s Napoléon.

By this point, stylistic influences were beginning to pass back and forth between France and Germany. Le brasier ardent shows distinct touches of Expressionism in its decor, as when the heroine flees through a distorted door. (See top.)

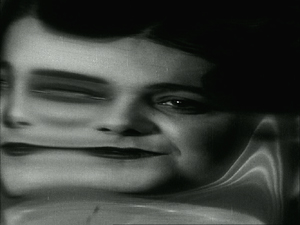

I have to admit that the third Impressionist film on our top-ten list, Germaine Dulac’s La souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet) is not one of my favorites. It hasn’t got much of a plot. A sensitive woman in a provincial town finds her husband crass and unpleasant until a final crisis brings them–at least temporarily–together. It’s not so much the simplicity of the story, however, as the rather heavy-handed use of subjective camera tricks to convey Mme. Beudet’s thoughts about her husband, as when a distorting mirror conveys her grotesque view of him (at right).

I have to admit that the third Impressionist film on our top-ten list, Germaine Dulac’s La souriante Madame Beudet (The Smiling Madame Beudet) is not one of my favorites. It hasn’t got much of a plot. A sensitive woman in a provincial town finds her husband crass and unpleasant until a final crisis brings them–at least temporarily–together. It’s not so much the simplicity of the story, however, as the rather heavy-handed use of subjective camera tricks to convey Mme. Beudet’s thoughts about her husband, as when a distorting mirror conveys her grotesque view of him (at right).

We’ve just seen a similar distortion in Cœur fidèle, above, to show a drunkard’s point of view. In Marcel L’Herbier’s El Dorado, from 1921, another distorted-mirror close-up suggests drunkenness without using a character’s point of view (see Film History: An Introduction, 3rd edition, p. 79).

The film has decided virtues, such as the lovely shots of the small provincial town in which the film’s exteriors were made, as well as the genuinely surprising and touching ending, which pulls back somewhat from the simplistic characterization of M. Beudet.

As with some of our choices from previous years, The Smiling Madame Beudet goes on the list partly because of its historical importance. Dulac was one of the early women directors to make a career in the cinema. Back in the days of 16mm, prints of this film were among the few Impressionist classics available for film club and classroom use, and the film became a staple in feminist-film courses.

Ironically, nowadays teaching the film is more difficult. Oddly enough, none of the mainstream labels has brought out a DVD with English subtitles. A German DVD, which includes two other short Dulac films, Invitation au voyage (1927) and the surrealist classic La coquille et le clergyman (1928), is available. The copy on this DVD is probably the same as the fairly good-quality Swiss archive print on YouTube, with bilingual French and German intertitles. For anyone with even an elementary knowledge of either language, the titles are not very challenging.

Caligarisme spreads

Caligarisme was the French word for cinematic Expressionism, which, as the example from Le brasier ardent shows, fascinating many French filmmakers.

Despite the lack of major contributions from Murnau and Lang, in 1923 the country’s cinema was going strong. Several films that fall slightly short of being masterpieces appeared. By this point the Expressionist film movement was well established, having begun in 1920 with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. Some of its greatest films–Der müde Tod, Nosferatu and Dr. Mabuse der Spieler–had already appeared.

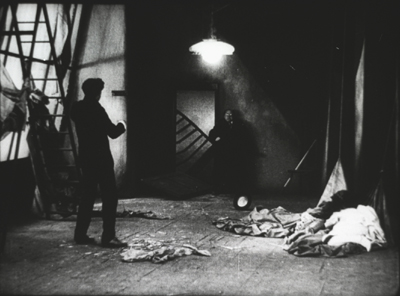

Three very good Expressionist films came out in 1923: Erdgeist (“Earth Spirit,” directed by Leopold Jessner), Schatten (“Shadows,” released abroad as Warning Shadows; Arthur Robison), and Raskolnikow (adapted from Crime and Punishment; Robert Wiene).

It’s really a toss-up as to which film should represent Expressionism on this year’s list. I give the edge to Erdgeist, largely because it and Von Morgens bis Mitternachts (“From Morn to Midnight”) are the two films from the movement that push the style the furthest. They come the closest to Expressionism as it existed in drama and the other arts. Most Expressionist cinema “tamed” the style a bit by applying it to genre tales: horror (Caligari, Nosferatu), fantasy (Der müde Tod), historical myth (Die Nibelungen), and science fiction (Algol, Metropolis). These two films, in contrast, depended on dramas where elemental human passions are released and taken to extremes, with the costumes, decor, makeup, and acting reflecting the characters’ inner states.

The film was based on the first of the two “Lulu” plays by Frank Wedekind: Erdgeist (1895) and its sequel Die Büchse der Pandora (Pandora’s Box, 1904). G. W. Pabst’s much better-known Pandora’s Box (1929) combines the two plays, which tell a continuous story about an amoral young woman who lives by exploiting wealthy men but drives them to extreme jealousy by flirting with other men.

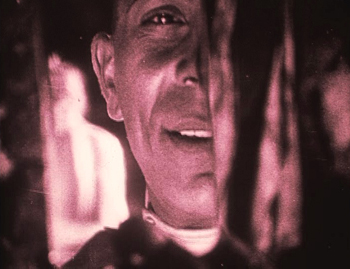

In Pabst’s film, Louise Brooks plays Lulu as a vivacious young woman, seemingly unaware of her disastrous effect on the men around her. Asta Nielsen plays the character in Jessner’s film as a ruthless, mature woman. The plot concerns Dr. Schön, a rich man who found Lulu on the streets when she was a child and has raised her with the intent of having her become his mistress. At the beginning, she is married to Dr. Goll but immediately begins seducing Schwartz, an artist hired to paint her portrait. In the image below, Goll bursts in on them in Schwartz’s studio and Lulu collapses at the right. The distorted stairway, the streaks of light painted on the set, and the jagged shadows all create the Expressionist look–as does the eerie blank glow of Goll’s glasses.

The acting is exaggerated and unnatural. Nielsen, foregoing all glamor, frequently holds a grimace on her face to the point where she almost looks like she is wearing a mask. In an early scene Goll moves his cane about, and she dances like a marionette attached to it by strings. (Puppet-like acting was a convention of Expressionist drama.)

Overall, the style is so grotesque and the characters so unpleasant as to make it clear why Erdgeist is one of the least remembered of the major Expressionist films. It is not available on home video. The print I saw about 16 years ago had Dutch intertitles and was somewhat dark. Perhaps, like Von Morgens bis Mitternachts, it will eventually be restored and released on DVD.

Two Expressionist films deserve brief mention as well.

Robert Wiene, the director of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari, launched the Expressionist movement in cinema but never made another film that gained nearly as much attention. That’s a pity, because Raskolnikow is quite a good film–of all the Wiene films I’ve seen, probably his second best (though The Hands of Orlac, 1924, has its virtues). I found it difficult to decide between it and Erdgeist.

Crime and Punishment turns out to be, not surprisingly, a good fit for the style, with the hero’s increasingly bizarre view of the world literalized in the settings. The film seems to have had a higher budget than Caligari, and the sets are sturdier looking and more three-dimensional. (See bottom.) Wiene also had the good fortune to work with a group of Russian emigré theatrical actors who had trained under Stanislawski and worked at the Moscow Art Theater. Clearly they had to adapt their approach distinctly to achieve Expressionist performances, but they managed well. The lead, Gregori Chmara, makes a haggard and mercurial Raskolnikow.

Back in the 1970s, when I became intrigued by German Expressionist cinema, Schatten was considered one of the main classics. That was no doubt partly due to the limited number of Expressionist titles available for viewing at the time. It’s a good film, but its prominence in film history has declined a bit in the intervening decades, especially as the full surviving work of Murnau and Lang has been discovered and restored.

Schatten is an atypical Expressionist film. Not that many of its sets are distorted or simplified in the usual ways. (This is also true to some extent of designer Albin Grau’s other notable Expressionist film, Nosferatu.) Its few exterior shots, including the opening, show the most strongly Expressionist decor (below left). Part of the action consists of a shadow-puppet show put on by a wandering entertainer (below right). Its plot seems to magically unleash the passions of the onlookers, who begin to behave in odd ways. The male guests (and a servant) try to seduce their hostess, driving the master of the house into a jealous rage.

The shadow play creates its own distortions and stark, black and white imagery. Once the show is over, Robison often frames the distorted shadows of the characters more prominently than their actual bodies (again echoing some of the scene with the vampire in Nosferatu). In this corridor scene one of the servants slyly creates cuckold’s horns on another man’s head:

Shadows, with their natural capacity for distortion, not surprisingly appeared in many Expressionist films, though never so pervasively as in this one.

Raskolnikow is unfortunately not available on home video, at least in an acceptable copy. (The reviews for the Alpha release on Amazon deem it “unwatchable.”) Warning Shadows is available on DVD from Kino or to stream on Amazon (free to Prime customers).

Returning to our top-ten list, I yield the floor briefly to David, who has been studying Sylvester for another project.

German silent cinema is more varied than a litany of the official classics, from Caligari to Metropolis, would suggest. One of the most intriguing trends of the period involved what was called the Kammerspiel, or chamber-play, film. Kammerspiel films were far more naturalistic than Expressionist films. They concentrate on a very few characters in a drastically limited number of locales. Performance is often slow and understated, though action may freeze into somewhat contorted poses. The action typically takes place in a short time span, and it is built up out of everyday activities in working-class households—chores, job routines, the habits of family life. Eventually, however, the mundane milieu is likely to explode into violence.

The versatile Carl Mayer (who worked on the script of Caligari) conceived of the early Kammerspiel film Scherben (Shattered, 1921), which defined the trend. In the same year the stage director Leopold Jessner released the remarkable Hintertreppe (Backstairs), which Kristin mentioned as a runner-up in her Best of 1921 list. Mayer also wrote the script for Sylvester (1923). Named for the feast day of St. Sylvester, 31 December, it’s known in English as New Year’s Eve. It’s not available on home video, but it’s worth seeking out in screenings. It remains a striking study in tabloid tragedy.

A café owner and his wife are busily serving crowds on New Year’s Eve. After a big meal and too many drinks, the wife and the mother-in-law fall to quarreling. The tensions around the table are constantly crosscut with the increasingly wild revelry in the café and the upper-class nightclub across the street. As midnight draws near, the women struggle for the husband’s loyalty. This petty quarrel will end in death.

Director Lupu Pick explores the limited space of the action by shooting the parlor from many angles, including ones that make daring use of a mirror (right). The street shots feature extravagant camera movements that look forward to the “unchained camera” made famous in Der letzte Mann (The Last Laugh, 1925), directed by F. W. Murnau and scripted by Mayer. With its strict limitation to a single night and its focus on domestic space, along with suggestions of the husband’s Freudian dependence on his mother, Sylvester showed how a fait divers could yield psychological drama.

The Kammerspiel film wasn’t a dead end. After Carl Dreyer’s borderline contribution to the trend, the Ufa production Michael (1924), back in Denmark he created probably the best of the lot: The Master of the House (Du Skal Aere Din Hustru, 1925). He later returned to the aesthetic in Two People (1945), and he continued to exploit its possibilities in his last features. Over the years after World War II, other directors were rediscovering Kammerspiel principles. We see fresh applications of the approach in Les Parents Terribles (Cocteau, 1948), Les Enfants Terribles (Melville, 1949), and of course Hitchcock’s Rope (1948) and Dial M for Murder (1954). As often happens, ambitious films of the sound cinema owe a good deal to innovative impulses of the silent era.

Welcome, experimental cinema!

One of the most remarkable films of 1923 is a mere three minutes long. Man Ray, an American painter and photographer who moved to Paris in 1921 and became involved in the Dadaist and Surrealist movements. He soon acquired a film  camera and later described how he shot bits of footage with it:

camera and later described how he shot bits of footage with it:

a few sporadic shots, unrelated to each other, as a field of daisies, a nude torso moving in front of a striped curtain with the sunlight coming through, one of [his] paper spirals hanging in the studio, a carton from an egg crate revolving on a string–mobiles before the invention of the word, but without any aesthetic implications nor as a preparation for future development: the true Dada spirit.

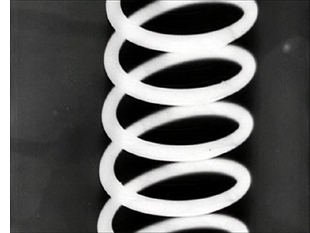

In 1923 Tristan Tzara advertised a Dadaist program in a Parisian theatre to be held the following evening, including a film by Man Ray as part of the entertainment. Ray had only a very small amount of footage ready. Faced with an overnight deadline, he supplemented it by using a technique he had already employed in still photography (the “rayograph”): placing small objects on a sheet of photographic paper in the dark, turning on the light briefly, and developing the image. The result was a series of sharply focused silhouette images of the objects against a plain background. This time Ray unrolled some raw negative film in a dark room, scattered nails, tacks, and other objects on it, exposed it to light, and developed the negative (right). Combined with the shots Ray had previously made, the result was a perfect Dada film, with randomly juxtaposed imagery that defied the audience to make any sense of what they were seeing. He titled it in ironic Dada fashion: Le retour à la raison (“The Return to Reason”).

Despite being cobbled together overnight, Ray’s film offers a broad exploration of the possibilities of abstract filmmaking. The opening, a rapidly shifting stippled screen, resembles the later flicker films of the 1960s avant-garde. The rayograph shots introduce an alien, high-contrast look–not surprising, given that these may have been the first cinema images produced without using a camera.

Ray also shifted between positive and negative imagery. This was not entirely new. Murnau had used short stretches of negative footage in Nosferatu the year before. But Murnau’s negative shots had a narrative function, to convey the eeriness of the environs of the vampire’s castle. In Le retour à la raison, Ray used negative imagery in an abstract way, to create startling juxtapositions of imagery that looked both similar and yet strikingly different. The tacks, nails, and springs in the rayograph stretches could be either stark white against black, as in the image to the right above, or the same shot repeated, but this time in black against white. The film ends with another positive/negative passage. The “nude torso moving in front of a striped curtain” is initially shown in a positive image, then in the same image flipped and shown in negative:

Ray was not the first to create an abstract film. In 1921 German filmmaker Walter Ruttmann probably made that conceptual leap in 1921 with Opus 1, a one-reeler with painted shapes moving around against a dark background. He followed this up with three further films, Opus 2 (1923), Opus 3 (1924), and Opus 4 (1925). (Good-quality prints with toning and appropriate musical accompaniment are available on YouTube: Opus 1 here, Opus 2 here, Opus 3 here, and Opus 4 here.)

I must confess that I probably should have at least mentioned Opus 1 in my entry on the best films of 1921. Still, Ruttmann’s films are far less daring than Le retour à la raison. It and its successors are basically efforts to do what so many filmmakers have tried since: to create the equivalent of a painting, but with motion. Ray’s film went much further, pushing the limits of the young art form in ways that had little precedent in the other arts, apart from Ray’s own highly experimental approach to still photography. There are even two fleeting stretches of film leader with illegible writing on them–a tactic one thinks of more in relation to, say, Bruce Conner’s A Movie (1958) than to the silent era. Much of the experimental cinema to come decades later was briefly probed here.

There are several copies of Le retour à la raison on YouTube. The best was posted by Dimitri Shubin, who also provides a piano score. The film is also available on disc 3 of the Unseen Cinema set of American experimental cinema. Unfortunately this copy has a considerable amount of breakup, particularly in the early flicker portions. (An HD version would perhaps help.) The version on Kino’s “Avant-Garde: Experimental Cinema of the 1920s and ’30s” set has the same problem and is distinctly shorter, apparently because it is running at sound speed. The copy provided by Shubin has the clearest, steadiest video image of the film I have seen. Ideally, of course, Ray’s film should be viewed on 35mm.

I regret that so many of our choices for this year’s list are not available on home video or even, except in very rare circumstances, for viewing on 35mm in archive screenings. Still, part of the purpose of this ongoing series is to call attention to obscure but worthy and important films. Perhaps an archivist or an enterprising DVD publisher will be inspired to restore some of the ones described here.

The quotation concerning The Three Ages comes from p. 217 of Rudi Blesh’s biography, Keaton (New York: Collier, 1966).

Mary Pickford’s strangely distorted claims about Rosita and her relationship with Lubitsch are expressed on pp. 129-34 of Brownlow’s The Parade’s Gone By (New York: Knopf, 1968). I go into more detail about the continuing Pickford-Lubitsch collegiality in the 1920s in Herr Lubitsch Goes to Hollywood, pp. 24-26.

For more examples of unusual German silent films, go elsewhere on this site here and here and here and here and here and here and here and here. Criterion has a new, authentic version of Dreyer’s Kammerspiel-influenced Master of the House forthcoming.

The Man Ray quotation comes from a detailed study of Le retour à la raison by Deke Dusinberre in the collection Unseen Cinema: Early American Avant-Garde Film 1893-1941 (New York: Anthology Film Archives, 2001), published to coincide with the release of the DVD set mentioned above.

Raskolnikow.

The ten best films of … 1922

Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler, Part 1.

Kristin here:

As the end of the year approaches and critics are posting their ten-best lists for the year, David and I once again fail to follow that tradition. Instead, we follow our own custom, now six years old, and turn our historians’ eyes back ninety years to offer ten great films from 1922. Of course, there are many films from the silent era that are lurking in archives, waiting to be discovered. Still, pointing to some noteworthy films we do have may help viewers to explore that rich period of cinema’s past.

Our previous lists can be found here, for 1917, 1918, 1919, 1920, and 1921.

For the past two years, I’ve noted that it was difficult to fill out the list of ten masterpieces. I keep thinking that I’ll get to a year where I won’t have to say that, but 1922 turns out not to be that year. Some titles were obvious, but the last one or two took some hunting.

As usual, one problem is that so many films are lost. Not one of John Ford’s three films of 1922 survives. In other cases great directors made lesser films. Important though Das Weib des Pharao was in Ernst Lubitsch’s career, partly because it shows him quickly picking up influences from Hollywood films, I can’t rank it among his first-rate titles. The same is true of Victor Sjöström, whose Vem dömer isn’t up to the level of other films like The Outlaw and His Wife.

Some of the films here, then, we consider classics but not masterpieces. Still, they have been influential and are well-regarded by other critics and historians. We’ll just call attention to them and let people form their own opinions.

Germany rules

But here are two full-fledged masterpieces, both from the German Expressionist movement. They demonstrate the potential for popular genres—here the horror and master-criminal genres—to achieve the highest level of filmmaking.

Few of F. W. Murnau’s early films survive, but there’s no doubt that he hit his stride in or before 1922. He made two outstanding films that year, Der brennende Acker (“The Burning Earth”) and Phantom, along with one of his very finest, Nosferatu. It is the earliest surviving film adaptation of Bram Stoker’s Dracula. (“Nosferatu” is Rumanian for “vampire.”)

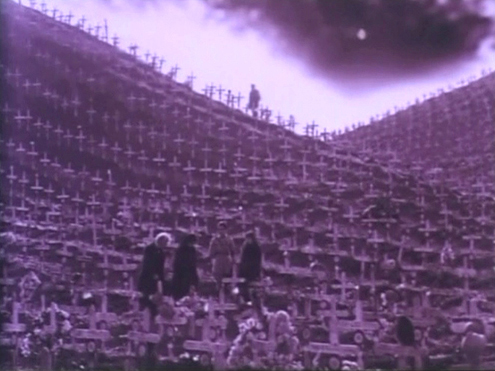

Nosferatu is generally considered an Expressionist film, though there are only a few of the stylized sets that we tend to think of as vital to that artistic movement. Murnau instead mostly uses a combination of staging and framing in real locales to create echoes of shapes between characters and their surroundings, something usually accomplished through more painterly means in films like Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari and Die Nibelungen. The nested arches in the left image frame Hutter’s arms, while Ellen’s forlorn slump on the bench as she awaits her husband’s return is juxtaposed with the leaning crosses that hint at fruitless vigils in the past.

One of my favorite moments in Nosferatu comes during the scene where Count Orlock is about to attack Hutter in one of the bedrooms in his castle. Ellen, at home in Wisburg, somehow senses this and in a panic throws out her arms in a desperate appeal for mercy. Orlock turns and looks away from Hutter, and the next shot again shows Ellen’s appeal.

It is a classic shot/reverse-shot situation, and yet the two are in different countries, many miles apart. The situation is ambiguous. Does Orlock sense Ellen’s appeal? Does he somehow magically see her from afar? Whichever is the case, he does leave Hutter’s room, and the clear implication is that her gesture has caused that withdrawal. Such a treatment of space is unusual, to say the least.

“False” eyeline matches or shot/reverse-shot passages linking distant characters were already fairly conventional. Hoping to put another of Maurice Tourneur’s films on our ten-best list, I watched his 1922 Lorna Doone. Though it has some marvelous passages, especially in the final battle, I couldn’t justify including it. Still, it provided a more conventional version of the false shot/reverse shot. In a scene where the hero thinks of Lorna, looking off front right, the following shot shows her thinking of him and looking off left.

They are in houses on neighboring estates, but they certainly cannot see each other. Moreover, there’s no indication that either suspects the other one is thinking of him/her. There is no ambiguity. Clearly the lovers are simply daydreaming about each other. The Nosferatu scene is more puzzling and evocative.

There is much more that once could say about Nosferatu—especially the experimentation with fast motion, negative footage, and pixillation to render the supernatural nature of the vampire—but I leave that for the reader to discover. There are a number of DVD versions available, but the Kino one contains the restored print and a documentary about the film’s production; the restoration is also available in the UK from Eureka!.

If this blog is still functioning in ten years, our list will definitely include a second great vampire film, Carl Dreyer’s Vampyr.

While Nosferatu plays on exotic, historic fantasy, Fritz Lang’s Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler (“Dr. Mabuse, the Gambler”) places its bizarre crime story squarely in contemporary Berlin. Mabuse (the incomparable Rudolf Klein-Rogge) is a master criminal with hypnotic powers, a man of innumerable disguises who lures his victims into gambling, whether in casinos or on the stock exchange. He also steals crucial documents to manipulate stock prices and controls the lives of many of the main characters. Throughout the lengthy plot, Detective von Wenk follows Mabuse’s trail, himself eventually falling under the criminal’s spell before exposing Mabuse’s identity.

Unlike with Murnau, we now have all of Lang’s early films and can judge his entire career. Arguably his first great film was Der müde Tod, which was on last year’s list. The first of his three Dr. Mabuse films (the others being Das Testament des Dr. Mabuse, 1933, and his last film, Die tausend Augen des Dr. Mabuse, 1960) was a step upward. It was made as a two-part serial: Der grosse Spieler—Ein Bild der Zeit (“The Great Gambler—A Picture of the Time”) and Inferno: Ein Spiel von Menschen unserer Zeit (“Inferno: A Play about People of Our Time”); together the parts run about four and a half hours.

The plot of Dr. Mabuse, der Spieler is very complicated and demonstrates Lang’s extraordinary ability to present a narrative visually. His sets, lighting, and staging are impeccable and already recognizably Langian. Consider the frame at the top of this entry.

In a gambling den, von Wenk, at the center top, and two important female characters, Countess Told, beside von Wenk, and Cara Carozza, left foreground, are staring at a rich old lady who has just gambled away a huge amount of money, caught by Mabuse’s spell. Her loss is the central action, yet she is placed so low in the frame as to be recognizable primarily by her silly beaded hat. Her gigolo, partly offscreen at the right, considers his position in the light of this disaster. Cara reacts with horror, the Countess and von Wenk with distress and sympathy. The other woman is an onlooker.

The tableau style of staging, keeping all the significant characters onscreen and moving them by slight increments to stress each character in turn, is still in play here, but the camera is closer to the actors, and they don’t move much. This isn’t just a tiny moment caught in the midst of a shifting composition. This is the composition. It looks remarkably modern. Each character, in his or her own way, is wondering, as we are, what has brought this minor character to such a pass. And she is tucked into a corner of the frame, as Lang will do in later films.

Dr. Mabuse‘s stress on “Our Time,” contemporary Weimar Germany, brings in the film’s Expressionistic elements. Expressionism here isn’t an all-encompassing filmic treatment that reflects a fantasy world or the psychological extremes of the characters. Instead, it is a tangible decorative impulse pervading the modern city. Below, von Wenk responds with distaste upon first viewing Count Told’s collection of modern art; yet in another scene, he calmly dines with an associate in a thoroughly Expressionist restaurant:

The bits of set visible in the background of this entry’s top frame indicate that the casino is another Expressionist locale.

The restored two-part film is available from Kino in the USA and in “The Complete Fritz Lang Dr. Mabuse Box Set” and from Eureka!’s “Masters of Cinema” series in the UK.

The grandiose and the modest as French Impressionism defines itself

The French Impressionist film movement can be said to have begun in 1918 with Abel Gance’s La Dixième Symphonie, though it has relatively few moments of the sort that came to define the style. It primarily uses superimpositions and split screen to convey a sense of the composer’s musical performances. Films by critic and theorist Louis Delluc followed, and Marcel L’Herbier explored pictorial and poetic effects in his early films. Highly subjective uses of film technique, which we think of as crucial to Impressionism, appeared in a really consistent way in El Dorado (1921), which was the first film of the movement to appear on our ten-best lists.

In 1922, the movement gained momentum with Gance’s monumental La roue. Many critics and historians consider this and Gance’s Napoléon masterpieces. I consider them more uneven, with brilliant stretches mixed in with melodramatic, sentimental, even occasionally maudlin scenes mixed in. Few people have seen all the surviving footage from La roue. The shorter versions available tend to eliminate the sentimental bits, which often run on and on. I’ve already voiced my opinions, favorable and less so, in the entry “An old-fashioned, sentimental avant-garde film,” posted when the longest version available on DVD was released by Flicker Alley.

I mentioned there that the footage cut from the shorter versions of the film seemed to be some of the sentimental moments. One such scene seems to me unintentionally risible. The hero, Sisif, is a veteran train engineer; he has suffered an injury that is slowly causing him to go blind. Unable to face turning his beloved engine over to a rival engineer, he ponders destroying it. Sitting on the engine, he asks whether it would not prefer being wrecked to being turned over to another driver. The replies to his questions are given as titles superimposed over the train:

This is, I think, representing Sisif’s delusion that the engine speaks to him, but I’m afraid it comes across as if the train is suddenly talking out loud. In a sound film it’s easy to understand that a sound can originate subjectively in the mind of a character. People don’t, however, tend to imagine sounds as written words!

There’s no question that La roue has some extraordinary scenes. The opening train wreck and its aftermath are justly famous, as is the accelerating editing in the scene in which Sisif drives his stepdaughter Norma, with whom he is secretly in love, into the city to marry another man; his agitation and thoughts of crashing the train are reflected by the increasingly shorter shots. And although it’s dangerous to make claims about any film having the first use of a given technique (usually someone will find an earlier one), Gance seems to have been the first to use stretches of single-frame editing. These occur at a moment when one character in a crisis situation (trying to avoid spoilers here) recalls a cluster of scenes from his past. Maybe the Soviet Montage directors would have come up with that idea on their own—but maybe not. Along with El Dorado, La roue helped define what were to be the main traits of Impressionism.

One thing I didn’t mention in my entry on La roue is the striking contrast between the romance plot and the many scenes shot around the train-yard, which were shot on location. They add a gritty realism that does much to make up for the melodrama—a realism that largely disappears in the final portion, when Sisif is transferred to a mountain location to run a funicular train.

Most of the French Impressionist directors, and particularly Gance, L’Herbier, and Delluc, were concerned to prove that cinema was an art form. Their films tended to be serious, poetic, and based more on in-depth psychological portraits than on the more action-oriented films of Hollywood. They were also clearly made by Artists with a capital A. Gance and L’Herbier liked to start their films with close-ups of themselves staring into the lens with artistic fervor. L’Herbier’s photos included autographs. The films were designed to appeal to an intellectual crowd, though Gance’s were also highly successful at the box-office. Other directors’ films weren’t hits, however, and as the decade progressed more of them played only in the ciné-clubs and art theaters that sprang up.

Another Impressionist film of 1922, Jacques Feyder’s Crainquebille, took a very different tack. I remember seeing Crainquebille decades ago and not thinking much of it, though it has long been considered a classic. Now, however, watching the 2005 restoration by Lenny Borger and Lobster Films, I think it’s much more interesting. That’s not surprising, given that the print I originally saw was probably the 50-minute American release version, and the restoration adds half again as much footage, bringing it to 76 minutes. (The Internet Movie Data Base lists the original Belgian release print as 90 minutes, so presumably what we have is still not complete.)

Crainquebille has been admired for its realism and for the performance of a well-known stage actor of the day, Maurice de Féraudy in the title role. Jérôme Crainquebille is an elderly vegetable peddler, and much of the film was shot in the streets and markets of Paris, sometimes using long lenses to capture scenes of crowds and passers-by, unaware of the camera’s presence. But what struck me upon seeing it again is that Feyder was trying to make an Impressionist film for ordinary cinema-goers, perhaps the working-class people who could relate best to Crainquebille’s situation and milieu.

True, the film has a prestigious pedigree, being an adaptation of an Anatole France novel and starring a famous theater actor. Yet the story is simple and told in a relatively straightforward manner. Most of the action arises from a misunderstanding: A gendarme, thinking Crainquebille has insulted him, arrests him. A leisurely scene shows the protagonist enjoying the unusual luxury of his prison cell: a comfy bed, free meals, a toasty radiator, hot and cold water in a pristine sink, and a floor clean enough to eat off. A working-class audience would probably find this wryly amusing.

More telling, though, is the fact that when the typical camera techniques of Impressionism are used, Feyder inserts explanatory intertitles just before the subjective shots occur. This particularly happens in the long central trial scene. When the gendarme steps up to testify, a title informs us, “In Crainquebille’s eyes the Constable looked as important as his testimony.” We see Crainquebille gazing forlornly off right front and then his point-of-view of the witness, looming like a giant over the courtroom:

Subsequently a passerby from the scene of the “crime,” Dr. Mathieu, testifies on Crainquebille’s behalf. A title informs us, “To Crainquebille this testimony seemed to carry little weight.” We see a similar pair of shots, with the witness a tiny figure in the midst of the court. Naturally Crainquebille is found guilty and goes off to two further weeks of free room and board.

The next scene begins with an intertitle, “Dr. Mathieu’s Nightmare.” We see Mathieu in bed and then are taken into his nightmare, which depicts the court as a stylized, hellish place with the judges fearsome figures who leap onto their desk in extreme slow motion. (I have no way of knowing what the source of these intertitles is, so I must simply assume here that they reflect what was in the original film.)

Such heavily signaled experiments wouldn’t in themselves make Crainquebille a real masterpiece, but at a time when Impressionism was just gelling as a recognizable style, it seems a laudable attempt to find a non-elitist way to use it. In addition, the shots of the market where Crainquebille goes each morning are quite lovely, taken from neighboring rooftops with telephoto lenses.

As to what was restored in this version, there is remarkably little information on the internet. My notes from an archive viewing of the shorter version in 1984 suggests that the entire opening sequence in the restored version is “new.” It consists of Crainquebille and other vegetable peddlers pushing their carts across Paris to the main market. They pass through a wealthy district, which is characterized with vignettes of rich people’s decadence. The peddlers then pass through a high-crime district, with police rounding up criminals and prostitutes. (The inclusion of prostitutes suggests why this scene was cut for the American version.) The shorter version begins with the market scene and leads quickly to a scene in which Crainquebille rescues a poor newsboy from bullies, and the the scene where he is arrested follows. The entire character of Dr. Mathieu, the sympathetic witness, was cut, so the short version has a briefer trial scene and no nightmare. The action that follows Crainquebille’s release from prison is the same as in the restored version.

Crainquebille is available as part of a set, “Rediscover Jacques Feyder French Film Master,” along with restored versions of two of his other major films of the period, L’Atlantide (as “Queen of Atlantis,” 1921) and Visages d’enfants (as “Faces of Children,” 1925).

Hollywood dramas: The somewhat old and the somewhat new

The two Hollywood films on this year’s list are very familiar Hollywood classics, so I won’t spend much time introducing them.

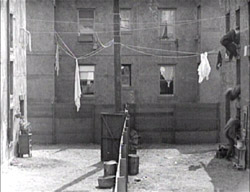

D. W. Griffith probably appears for the last time in our 90-year-ago lists with his historical epic, Orphans of the Storm. This tale of the French Revolution featured the last appearances for Griffith of Lillian and Dorothy Gish, whose first film roles had been in his American Biograph short, An Unseen Enemy, in 1912. They play apparent sisters, Henriette and Louise (though Louise is in fact adopted) living in a Normandy village. Louise becomes blind, but Henriette takes her to Paris in the hope of finding someone who can restore her sight. Upon arriving, they are separated and victimized, Henriette by the decadent nobility, Louise by the dishonest poor. Eventually they are caught up in the Revolution, and Henriette is nearly executed at the guillotine.

As in his best features, Griffith combines an ability to represent melodramatic stories of idealized, virginal heroines alongside naturalistic, convincing images of the poor:

Orphans of the Storm represents the lingering influence of the Victorian theater on Griffith. The slightly later Naturalistic strains of nineteenth-century literature are evident in the cynical narratives of Erich von Stroheim. His first film, and the most completely preserved, was Blind Husbands, featured in our 1919 ten-best list. As I said there, Blind Husbands is my favorite von Stroheim film, with its relative light take on attempted seduction, near marital infidelity, and retribution. Foolish Wives took the theme much further, with the director again playing the heartless rake, Count Wladislaw Sergius Karamzin. Rather than pursuing one vulnerable wife, he seduces every woman in sight, including a hotel maid and an invalid, bedridden girl (above whose bed a crucifix hangs, to make sure we grasp the sinfulness of Karamzin’s lust).

Von Stroheim famously reconstructed the casino and surrounding buildings of Monte Carlo, resulting in a budget overrun. Universal made the best of his profligacy by advertising Foolish Wives as the first million-dollar movie ever. (Whether it really was or not we shall probably never know.)

Although much of the film is fairly conventional, with shot/reverse-shot conversations, von Stroheim experimented occasionally. At the left below, he shoots into a small mirror as Karamzin secretly ogles the heroine, who is behind him, as she undresses. In a number of shots von Stroheim films through a scrim to give a canvas-like effect to a composition. Here the invalid girl whom the villain eventually tries to rape is seen with her doting father.

As with all of von Stroheim’s films after Blind Husbands, Foolish Wives was taken out of his hands by the studio and shortened considerably. Much of this was done by trimming the lengths of individual shots. The original film apparently does not survive, so it is impossible to assess the director’s style thoroughly, especially when it comes to editing. The revisions were not nearly as great, however, as with his 1924 film Greed, which was cut by well over half. Thus of all von Stroheim’s 1920s films, Foolish Wives is probably closer to what he intended than most. The standard version of the film (restored by the American Film Institute but not of sterling visual quality) is available from Kino in an edition that includes a 78-minute documentary, The Man You Loved to Hate, written by von Stroheim expert Richard Koszarski.

Hollywood silent comedy

Every year our list visits the great three slapstick comedians: Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd. Sometimes it’s all three, sometimes two. They have all been working their way through shorts to the great features of the 1920s. Chaplin made it there last year with The Kid. In 1922 he had a light year, reverting to two-reelers with The Idle Class and Pay Day, so we’ll skip him here and pick him up again later.

In 1922 it was Harold Lloyd who moved up to features with Grandma’s Boy. Not on a level with some of his later films, like Girl Shy (sure to be high on our 2014/1924 list), but a real charmer with some classic Lloyd routines.

Lloyd is undoubtedly best known for his “thrill” comedies like Safety Last (1923 and heavily favored to feature on this list next year), where he climbs a skyscraper. Still, his more typical roles in the features show him beginning as a timid or socially inept young man who gains courage or skill in the course of the narrative. In Grandma’s Boy, an amusing and touching scene introduces the hero as a perpetually frightened child, unable to stand up even to littler boys who steal his lunch. Once he has grown up, his diminutive grandmother manages to chase off an intruding hobo with her broom after the Boy (none of the characters is named) has failed do so:

Despite his timidity, the Boy has managed to attract a Girl, and a Lloydian string of gags occurs when she invites him and his thuggish Rival to visit her at home. Grandma polishes the Boy’s shoes with goose grease and dresses him in an antiquated suit with mothballs in the pockets. Once at the Girl’s house, the Boy attracts the unwanted attentions of a litter of kittens determined to lick his shoes. When the Girl reacts badly to the mothball-scented suit, the Boy hides the balls in a box of candy. This leads to a hilarious scene in which he and the Rival both accept some “candy” from the Girl and end up grimacing in sync and trying to smile every time the Girl glances at them.

As with many good classical films, almost exactly halfway comes a turning point: the sinister hobo has robbed a jewelry store and shot a man. The film’s second half becomes an extended chase in which the reluctant Boy is enlisted as a deputy. Thanks to a little psychological trick played by the Grandmother, he wins out.

Grandma’s Boy is available in the indispensable “The Harold Lloyd Collection,” one of New Line Home Entertainment’s finest achievements, or separately with some other features as Volume 2 of the same set, or even more separately with seven shorts from Kino.

Buster Keaton was still making shorts in 1922, but this doesn’t put him at a disadvantage in our list. Experts agree that of Keaton’s twenty starring shorts (after his work as sidekick to Fatty Arbuckle), the best are The Boat (1921) and Cops (1922). Both are strongly touched by the streak of surrealism that frequently shows up in Keaton’s work—as in the dream-within-a-film scene that forms the bulk of Sherlock Junior (1924).

In Cops, Keaton plays a young man trying to impress his beloved by making good in some fashion. He is duped by a crook pretending to be evicted, who sells him the furniture of a family moving house, along with the horse and wagon that has come to transport it. Taking off through the city with the furniture he intends to resell at a profit, Keaton finds himself in the midst of a police parade and innocently accused of throwing a bomb actually lobbed by an anarchist. Chaos breaks loose. No matter where our hero runs, everyone he encounters turns out to be a cop—including his sweetheart’s father and the owner of the furniture.

The film is full of wonderful sight gags. Keaton hangs his hat on the protruding hip bone of a scrawny horse, and he tries to make a mustache disguise out of a clip-on tie.

Cops is available in Kino’s collection of Keaton shorts and in its collection of most of the features and shorts. Also available in the UK in the Eureka! “Masters of Cinema” box set of all Keaton’s shorts.

Next year, Our Hospitality!

Documentary and storytelling

Although we’re not overwhelmed with admiration for our final two films, they demanded inclusion because they are recognized as canonical classics.

Nanook of the North has frequently been described as the first feature-length documentary. Here’s an example where it was dangerous to call something first. There is in fact at least one earlier, filmed at the opposite end of the Earth: Frank Hurley’s South (1919), a record of Ernest Shackleton’s famous shipwrecked expedition to the Antarctic. But Nanook found a much wider public and became a classic, while South disappeared until 1998, when it was restored by the British Film Institute.

Nanook also had the advantage of a charismatic central figure and his attractive family, a picturesque depiction of Inuit life, and a carefully scripted story that included moments of danger during a walrus hunt and humor during a visit to a trading post.

Still, the film has drawn criticism for its extensive manipulation of reality. “Nanook” was in fact an Inuk named Allakariallak, and the woman represented as his wife was not married to him. Scenes were staged, as when an already-dead seal was used in a hunt. Nanook expresses amazement at a phonograph, though he was already familiar with such devices. The Inuit had already adopted firearms for hunting by the time Flaherty filmed them, but he requested that they use spears instead.

As has been pointed out, however, Flaherty was trying to present a slightly earlier phase of the Inuit culture, preserving a lifestyle that was rapidly changing. Moreover, the documentary mode had previously consisted largely of actualities and travelogues, and there was little precedent for what Flaherty was doing. For decades after Nanook (originally subtitled A Story of Life and Love in the Actual Arctic), documentaries tended to be structured fairly explicitly as tales with entertainment value. In the wake of cinéma vérité, the issue of filmmakers interfering with their subjects and staging scenes has become controversial, but it was not a great concern in the 1920s.

If we accept the notion that this is a documentary with considerable manipulation, we can credit the film with conveying a good deal of information about the Inuit of a slightly earlier period. The igloo-building scene is interesting and informative, even if we know that the interior shots had to be made in an igloo actually open on one side to provide light for the camera.

Nanook of the North was restored and released by the Criterion Collection in 1999.

Although it also appeared in 1922, Benjamin Christensen’s Häxan tends not to get equal credit as the supposed first feature-length documentary. Perhaps that is because it barely qualifies as a documentary. It’s not clear what other genre or mode it belongs to, though it tends to be admired mostly by fans of horror films.

Häxan purports to be a lecture on the history of witchcraft. Its English title is Witchcraft through the Ages, though the original title means simply “Witches.” The first reel consists of a series of images from books both scholarly and sensational, showing ancient images of supposed witches or witch-like creatures. The claim is that witchcraft has been a universal concept in cultures throughout history. Whether this is true I can’t say, but the images shown of ancient Egyptian deities are not witches but protective figures.

In the second reel, Christensen begins to illustrate the points being made with staged scenes of witches, surrounded by animal skeletons and other macabre items, many of them used in potions. Gradually the staged scenes develop into a narrative set in the Medieval or early Renaissance era, with one old woman being accused of witchcraft and tortured. She finally admits to being a witch and names her accusers as witches, and the imprisonment and torture spread. Like Dreyer in Leaves from Satan’s Book and Day of Wrath, Christensen condemns the very notion of witch-hunting and the hypocrisy and cruelty of the Church. Yet he shows a considerable fascination with torture methods—although in place of graphic scenes he presents static shots of contorted limbs and exhausted victims.

The true strangeness of the film, however, comes from its visualization of demons and devils as real beings. They conducting orgies, fly on broomsticks, and attempt to seduce people into evil and madness. Perhaps we are to take these images as what the Church assumes is happening, but there is no indication of that. One has to suspect that ultimately the educational “lecture” premise of the film, which is handled in a perfunctory way, is an excuse for staging scenes that range from quite powerful (see below) to merely cartoon-like, with people dressed up in crudely made costumes.

At the end the lecture mode returns, with an unconvincing series of comparisons of witchcraft with modern-day activities.

Whatever one thinks of the subject matter and its treatment, the film’s cinematography is extraordinarily beautiful.

Häxan has been restored by the Svenska Filminstitutet and was released on DVD with optional English subtitles. The restoration is available in the USA from the Criterion Collection, but I haven’t seen it or its extras. The Criterion package includes a version of the film narrated by William S. Burroughs. I haven’t seen it, but according to David’s memory of the croaky, world-weary voice-over, it adds another layer of weirdness to the proceedings.

For many years Häxan, as the only film by Christensen that was available for viewing outside archives, gave a rather distorted view of this director. Then his two earlier films, Det hemmelighedsfulde X (“The Mysterious X,” 1914) and Hævnens Nat (“Night of Revenge,” 1916) became more widely available. They were revelations—beautifully shot, tightly scripted, exciting movies. Those who don’t like Häxan should definitely watch these; they are quite different. Both are available on a single DVD from the Danske Filminstitut. The DVD has English intertitles, and the online shop is bilingual, Danish and English.

Häxan

The ten best films of … 1921

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse.

Kristin here:

To end the year, we’re continuing our tradition of picking the ten best films not of the current year but of ninety years ago. Our purpose is twofold. We want to provide guidance for those who may not be particularly familiar with silent cinema but who want to do a bit of exploring. We also want to throw in occasional unfamiliar films to shake up the canon of classics a bit.

Like last year, it was strangely difficult to come up with ten equally great films. There were some obvious choices, but beyond them there were a lot of slightly less wonderful items jostling for the other places on the list. The problem had several causes. Some master directors who routinely figure in our year-end ten choices had off-years. In 1921 D. W. Griffith released only one film, Dream Street, a notably weak item. (What I have to say about it can be found on pp. 108-113 of the British Film Institute’s The Griffith Project, Vol. 10.) Ernst Lubitsch released two films that seem like less interesting attempts to repeat earlier successes: Anna Boleyn (a pale imitation of Madame Dubarry) and Die Bergkatze (nice, and I was tempted to include it, but it’s less amusing than the Ossi Oswalda comedies, here and here). Cecil B. DeMille’s The Affairs of Anatol is not nearly as well structured as his earlier sophisticated rom-coms.

In other cases, films simply don’t survive. John Ford released seven films in 1921, all of which are lost.

Death comes calling, twice

Probably the easiest decision was to include The Phantom Carriage (also known as The Phantom Chariot), by Victor Sjöström. As I noted recently, the Criterion Collection has recently issued a beautiful restoration of it (DVD and Blu-ray).

When I first saw The Phantom Carriage, I was probably still an undergraduate. Given its reputation as a great classic, I was somewhat disappointed. No doubt it was partly the battered 16mm copy I watched, but the film is a bit formidable for someone not accustomed to the aesthetic of silent cinema–and especially of the great Swedish directors of the era. Its protagonist, played by Sjöström himself, is a thoroughly, determinedly unlikeable fellow, and the complex flashback structure can be a bit disconcerting on first viewing. But the effort to watch until one “gets” Sjöström is well worth it, since he’s undoubtedly one of the half dozen greatest silent directors.

The story opens on New Year’s Eve with Edit, a young Salvation Army volunteer, on her deathbed. She unexpectedly begs her colleague and mother to fetch the town drunk, David Holm, to her bedside. At the same time, Holm sits drinking in a graveyard as midnight approache. He tells two fellow inebriates the legend of the phantom carriage, the vehicle that picks up the souls of the  newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

newly dead; it is driven each year by the last person to die at the end of the previous year. Holm then dies, and the carriage arrives, with its current driver ready to turn over the job to him. Flashbacks enact both the circumstances of how the heroine met Holm and the happy family whom Holm had alienated through his drunkenness.

It’s a deeply affecting story, wonderfully acted and staged. In most scenes the lighting and staging are impeccable, and the famous superimpositions that portray the carriage and the dead are highly ambitious for the period and impressively executed. The filmmakers have managed to make the carriage, superimposed on real landscapes, appear to pass behind rocks and other large objects. In short, a film that has everything going for it.

Death himself appears in Der müde Tod (literally “The Tired Death,” often called Destiny, or occasionally in the old days, The Three Candles). Here the great German director Fritz Lang hits his stride, and you can expect him to figure on most of our lists from now on.

In Destiny (available on DVD from Image Entertainment) a young woman’s fiancé is killed early on. Death, a sympathetic figure who regrets what he must do, gives her three chances to find another person whose demise can substitute for her lover’s. The three episodes in which she tries take place in Arabian-Nights Baghdad, Renaissance Venice, and ancient China; each story casts her as the heroine and her lover as the hero.Things don’t go well, and Death actually gives her a fourth chance when she returns to the present.

This was Lang’s first venture into the young German Expressionist movement, which had been launched the year before with Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari. The style shows up only intermittently, perhaps most dramatically in the Venetian episode when the lover shinnies up a rope along a wall painted with a gigantic splash of light. (See bottom.)

Each film has a “happy ending.” I leave it to you to determine which is grimmer.

I’m turning over the keyboard to David now, to describe a film he knows better than I do.

More Northern European drama

Mauritz Stiller alternated urban comedies (Thomas Graal’s Best Film, 1917; Thomas Graal’s Best Child, 1918; Erotikon, 1920) with more lyrical dramas and romances set in the countryside (Song of the Red Flower, 1919; Sir Arne’s Treasure, 1919). Johan (1921) is in the pastoral vein. Its integration of landscape into the drama suggests it was an effort to recapture the production values that overseas critics had praised in Sjöström’s Terje Vigen (1917) and The Outlaw and His Wife (1918). Like the Sjöström films, however, Johan offers more than splendid spectacle; it’s the study of the undercurrents of a marriage.