Archive for the 'PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book)' Category

Catching up

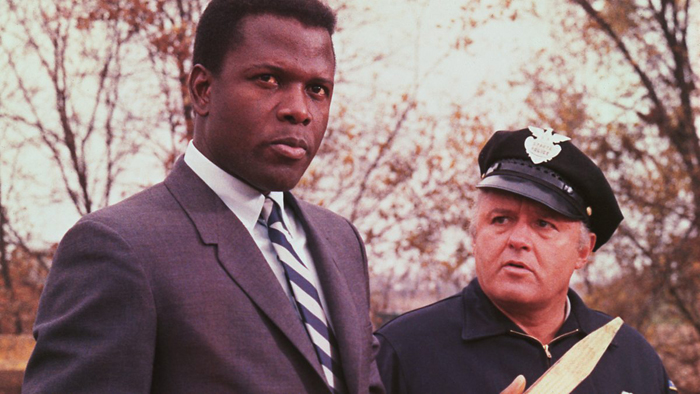

In the Heat of the Night (1967; production still).

DB here:

Some health setbacks have delayed my plans for a new blog entry, but as I clamber back from a bout of pneumonia, I thought I’d signal a couple of things I’ve read and enjoyed recently.

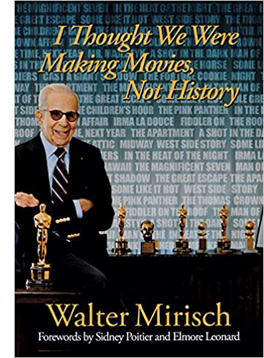

Walter Mirisch’s I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History is a discreet but still informative account of the career of a major producer (In the Heat of the Night, Some Like It Hot, West Side Story, The Magnificent Seven, and many other classics). Apart from offering some vivid vignettes of working with stars, Mirisch (UW grad) is very good on the corporate maneuvering that created, then sideswiped, United Artists. He swam with sharks and survived. Bonus: introduction by Elmore Leonard.

Stylish Academic Writing by Helen Sword is a lively guide to perking up your prose. Unlike most tips-from-the-top manuals, this is based on systematic research that yields some surprises. (Yes, scientific reports are allowed to use personal pronouns. No, literary theory isn’t the most opaque writing on earth: Educational research is.) There’s a lot of good advice here. I wish I’d read it before revising Perplexing Plots.

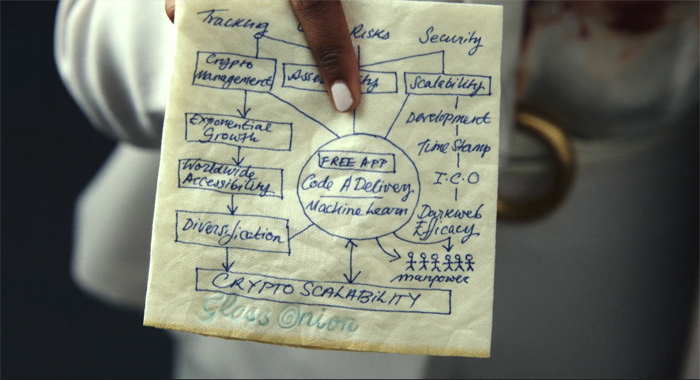

A shrewd, funny analysis of (a) the current prevalence of mystery stories and (b) streamers’ shotgun programming policies is offered by J. D. Conner in “Going Klear: A Glass Onion Franchise in the Wild” in the Los Angeles Review of Books. This wide-ranging essay ponders franchises, viewer tastes, and other current concerns. Extra points for noticing the Columbo revival.

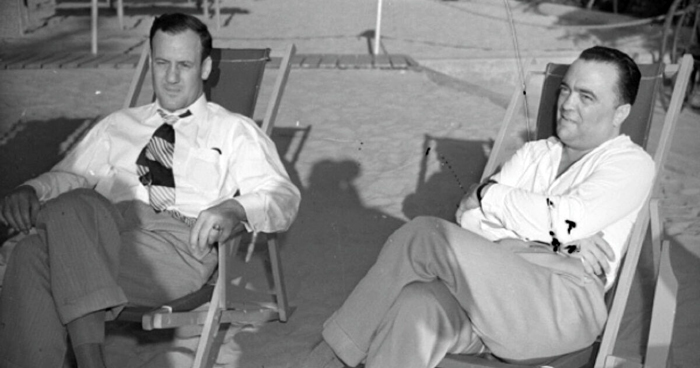

Way back in 1964, crime reporter Fred Cook caused a stir with The FBI Nobody Knows. After decades of celebrating the agency and its boss (a “confirmed bachelor” not yet revealed as in the closet), Cook’s chronicle of a frighteningly powerful force in the government inspired Rex Stout to write his top-selling Nero Wolfe book, The Doorbell Rang. Cook’s review of FBI history doesn’t out Hoover, and it does praise his ability to disclose WWII spy rings. But it concentrates on how his obsession with persecuting leftists had a long, ugly history. Today, when right-wingers are accusing the agency (staffed mostly with Republicans), it’s salutary to be reminded that the feds were long committed to ruining the lives of “communists” like Martin Luther King and ignoring the real danger of organized crime. Cook is helped by a whistleblower who reports mind-bending tales of peer pressure among agents. A lot of US history is crammed into this exciting, well-documented book.

I hope, when I can type (and think) more fluently, to post a new entry. On, I think, the power of crosscutting. Or maybe Puss in Boots: The Last Wish….

Clyde Tolson and J. Edgar Hoover in 1937. Source: The New Yorker.

P.S. 14 February 2023: In a stroke of serendipity, I learn that Paul Kerr’s new book, a historical-critical study of the Mirisch Company, is coming out next month. Knowing Paul, an expert on American independent production, I’m sure it will be deeply researched and an absorbing read. Congratulations, Paul!

P.S. 25 February 2023: Sad news: Walter Mirisch died yesterday. He was 101. The Variety report is here.

The reader is warned

Where the Crawdads Sing (2022; production still).

DB here:

When I wasn’t paying attention, along came Where the Crawdads Sing (2018 novel, 2022 film). The book was a huge bestseller, while the movie version was panned by critics but attracted a good-sized audience. It exemplifies how strategies of nonlinear storytelling have become deeply woven into mainstream entertainment.

It has an investigation plot, structured around the trial of “swamp girl” Kya, who’s accused of the murder of her boyfriend Chase in the marshlands of North Carolina. Through flashbacks we learn of her desperate childhood, as she is abandoned by her family and castigated by the townfolk. She learns to live alone in the family cabin and fills her days drawing precise images of the natural life around her. A well-meaning young man teaches her to read but he too he leaves her to struggle alone. Soon she meets Chase, a charming good-for-nothing. Is his fall from a swamp tower an accident, or did someone push him? A kindly local attorney takes her case, and the plot climaxes first in the jury’s verdict and then a twist that reveals what happened at the scene of the crime.

We’re so used to plots like this that we may forget how nonlinear they are. In the Crawdads film, the court investigation probes the circumstances of Chase’s death, but the flashbacks, instead of illustrating stages of the crime, supply Kya’s life story in chronological order. They contextualize the long-range causes of her dilemma. Accordingly, they’re narrated by her in voice-over. Titles supply the relevant timeline, dating episodes from 1963 through to 1970, the year of the trial.

All of these strategies have become familiar from a century of popular storytelling. A court case as an occasion to visit the past goes back at least to Elmer Rice’s On Trial (1914), although the play dramatizes testimony in a way that Crawdads doesn’t. (Its flashbacks, more boldly, are in reverse order.) The crosscutting of past and present has become common to explain (or obfuscate) ongoing story events. Tying us to a character’s viewpoint and letting the character’s voice narrate what we see is likewise a standard device in modern media. And of course an investigation plot is inherently nonlinear. The task is for someone to uncover the “hidden story” of what occurred in the past.

Simple though it is, Where the Crawdads Sing shows just how pervasive devices associated with mystery and detective fiction have become in mainstream storytelling. Told chronologically, the story would be a biography of Kya (and would presumably have to reveal how Chase died). Instead, the film becomes what Wikipedia calls “a coming-of-age murder mystery.”

By splitting the chronological story into two parts and interweaving them, manipulating viewpoint, and rearranging temporal order, the film tries to achieve interest and suspense. We know from the start that Chase is dead, so we watch every scene with him for clues as to what could have caused it. Tension gets amplified as time passes, when the shifts between the courtroom drama and the day of Chase’s death come faster and faster. These effects couldn’t be achieved with a linear layout.

One of the major points of Perplexing Plots is to remind us just how much of popular entertainment trades on narrative strategies forged in the big genre of mystery. Once we’re reminded, we can ask: How did those strategies get implemented? How did audiences come to understand and enjoy these highly artificial ways of telling stories?

I promise not to keep plugging the book on this blog, but allow me one more notice. A Q and A with me has been published on the Columbia University Press site. It tries to inform any souls whom fate has cast my way about the argument of the book. You may find it of interest.

I’m taking the occasion to note some features of the book not advertised elsewhere. Perhaps they too would appeal to you, especially if you’re interested in some of the choices a writer has to make.

Obscure is as obscure does

First, the book draws on some unorthodox sources. Most obviously, I tried to canvass obscure novels and plays that are now forgotten but that did try some experiments with nonlinear storytelling. Who’d expect a reverse-chronology play in 1921, years before Pinter’s Betrayal (1978)? A 1919 play anticipates Rear Window by offering testimony from a deaf witness and then a blind one. The first version plays out on stage in pantomime, the second in a completely dark setting. A 1936 novel offers a string of conflicting character viewpoints on a single situation, revising and correcting previous accounts, well in advance of Herman Diaz’s recent novel Trust. A 1919 play depicts a woman in different aspects, as seen by the people who know her. These instances of what we now call “complex narrative” belong to what literary scholars have called “the great unread,” the thousands of pieces of fiction and drama that haven’t become canonical through enduring popularity or academic favor.

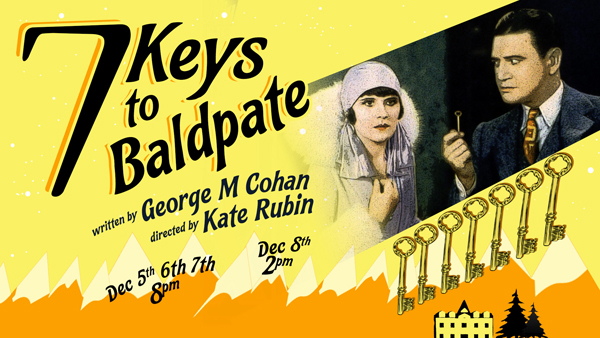

Other precedents are dimly recalled but seldom revisited, such as George M. Cohan’s play Seven Keys to Baldpate (1913) and W. R. Burnett’s Goodbye to the Past (1934). How many people would be aware of Kaufman and Hart’s reverse-chronology play Merrily We Roll Along (1934) if Stephen Sondheim hadn’t turned it into a musical? The very existence of these marginal works helps support the premise that a lot of what we consider innovative today has broad historical roots. They just aren’t as vivid to our memory as more recent instances. But fifty years from now, will many viewers remember contemporary experiments like Go (1999) and Shimmer Lake (2017)?

The book uses other unorthodox sources. I put craft technique at the center, and so it makes sense to look at the principles that writers of fiction and drama were using. Of necessity I review the emerging idea of the “art novel” at the end of the nineteenth century, with Henry James as spokesman for this trend. In addition, unlike most mainstream literary histories, Perplexing Plots consults contemporary manuals for aspiring writers. These books are the progenitors of all those how-to-get-published books that fill Amazon today, and they reveal a surprising sophistication. Manuals allow me to show how a new self-consciousness about linearity, particularly point of view, became central to popular writing as a craft. For example, a now-forgotten critic, Clayton Hamilton, epitomizes the willingness of ambitious writers to try out new possibilities.

So one choice I made was to search out fiction, drama, and films that have fallen into obscurity. Another was to look at the nuts and bolts of plotting, as practitioners seemed to be conceiving it. These help explain why many novels and plays, major and minor, began tinkering with innovative storytelling.

Time as space

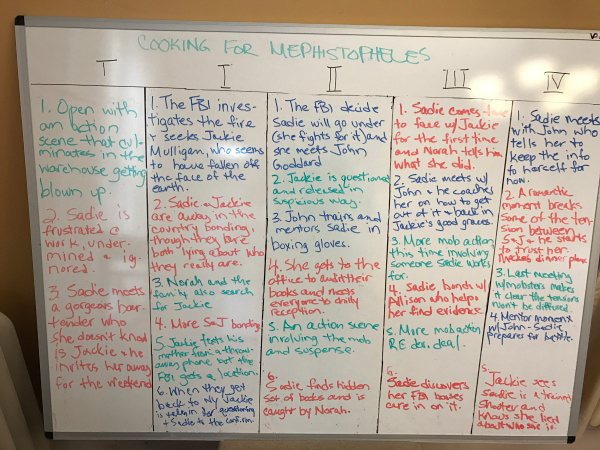

From Karen Loves TV: “Contemplations on the Whiteboard.”

A nonlinear plot has a geometrical feel to it, so one way of thinking about it is to envision it as a table or spreadsheet. Where the Crawdads Sing could be laid out in a double-column table, with each present-time scene aligned with the past sequence that follows it.

There are more complex possibilities as well. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) would constitute a four-column layout displaying each different historical epoch. Perhaps this is one sense of the term that came into use in the 1940s: “spatial form” as a description of unorthodox narratives. The principle is akin to the whiteboard “season arcs” and “episode outlines” used in writers’ rooms to lay out story lines threading through a film or TV series.

There are more complex possibilities as well. Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) would constitute a four-column layout displaying each different historical epoch. Perhaps this is one sense of the term that came into use in the 1940s: “spatial form” as a description of unorthodox narratives. The principle is akin to the whiteboard “season arcs” and “episode outlines” used in writers’ rooms to lay out story lines threading through a film or TV series.

Novelists have long made use of such charts. The most famous is that prepared by James Joyce for Ulysses, where each chapter is assigned a different color, body organ, and so on. This was published in Stuart Gilbert’s 1930 book. Because the rights to reproduction are obscure, we regrettably didn’t include it my book. No surprise, though, it’s available online.

I did, however, obtain rights to a less-known but rather brilliant table included in Anthony Berkeley’s Poisoned Chocolates Case (1929). Later chapters of Perplexing Plots use tables of my own devising to clarify the complicated layout of Richard Stark’s Parker novels, the chapter structures of Tarantino films, and the alternating viewpoints and time schemes of Gone Girl. There will always be readers who complain that these tables are just academic filigree, but I believe that they help us appreciate the intricate interplay of time, segmentation, and viewpoint. They show how precise the narrative architecture of mystery fiction can be.

To spoil or not to spoil

For decades, criticism of mystery fiction has labored under the expectation that a critic must not reveal a story’s ending, or the story’s central deception. In journalistic reviews of literature and film, the writer is expected to keep such things secret, but even academic studies of crime fiction put pressure on the critic to maintain the surprise of whodunit and howdunit.

But this limits our ability to study plot mechanics. I chose to preserve the secrets of the books, plays, and films as much as I could (as with my Crawdads sketch). Still, when the analysis demanded exposure of the “hidden story,” I did so. This doesn’t result in a lot of spoilers because some canonical texts, like The Maltese Falcon, Laura, and The Big Sleep, are very well-known. But I lay out some strategies of deception in novels by Christie and Sayers and films such as Gone Girl and The Sixth Sense. There really was no other way to show points of narrative craft at work in them, particularly the fine grain of writing or filming that shapes our response. I regret most exposing the central feint of Ira Levin’s novel A Kiss Before Dying, so readers who aren’t familiar with the book may want to read it before reading my account. Otherwise, I can only cite the title of one of Carter Dickson’s trickiest novels.

But this limits our ability to study plot mechanics. I chose to preserve the secrets of the books, plays, and films as much as I could (as with my Crawdads sketch). Still, when the analysis demanded exposure of the “hidden story,” I did so. This doesn’t result in a lot of spoilers because some canonical texts, like The Maltese Falcon, Laura, and The Big Sleep, are very well-known. But I lay out some strategies of deception in novels by Christie and Sayers and films such as Gone Girl and The Sixth Sense. There really was no other way to show points of narrative craft at work in them, particularly the fine grain of writing or filming that shapes our response. I regret most exposing the central feint of Ira Levin’s novel A Kiss Before Dying, so readers who aren’t familiar with the book may want to read it before reading my account. Otherwise, I can only cite the title of one of Carter Dickson’s trickiest novels.

Part of the justification for hiding the legerdemain is the doctrine of “fair play.” I trace how this idea emerged in the Golden Age of detective fiction, when a story was treated as a game of wits between author and reader. In principle, nothing necessary to the solution of the puzzle should be withheld, though it can be disguised or hinted at. One thing I learned in writing the book is that fair play has become a premise of most duplicitous narratives in any genre, from horror to science fiction. People don’t realize how much the maneuvers of Psycho and Arrival owe to the belief that the audience should in principle be able to go back and see how we were misled. (We can do this with the “missing clue” in Crawdads as well.)

Fair play encourages the author to be ingenious and entices the audience to appreciate artifice-driven construction. Both effects are legacies of classic detective fiction, and they still shape much mainstream entertainment.

Thanks to Maritza Herrera-Diaz of Columbia University Press for arranging for the Q & A published on the Press site.

The phrase “the great unread” is used by Margaret Cohen in The Sentimental Education of the Novel (Princeton, 1999) and cited in Franco Moretti, “The Slaughterhouse of Literature,” MLQ: Modern Language Quarterly 61, 1 (March 2000), 208.

As I’ve indicated in an earlier entry, Martin Edwards’ The Life of Crime is a vast and entertaining survey of the history of mystery fiction. It was crucial help to me in writing Perplexing Plots. Martin, an advance reader of the manuscript, has been kind enough to discuss my book on his blog.

Other early responses to the book have been encouraging. Michael Casey reviewed it for The Boulder Weekly, and Doug Holm discussed it on KBOO on his show Film at 11. My thanks to both these commenters.

Psycho (1960): Misdirection and fair play all in one shot.

GLASS ONION: Multiplying mysteries

Glass Onion (2022).

DB here:

Rian Johnson’s enthusiasm for classic mysteries made it inevitable that I’d get interested in writing about Knives Out. Although I merely allude to the film in Perplexing Plots, I devoted a blog entry to it. While thinking about a follow-up on Glass Onion, I began a rewarding correspondence with Jason Mittell, adroit blogger and author of Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. Today’s entry reflects my thoughts after this exchange of ideas.

Despite the near-universal acclaim received by Glass Onion, it didn’t whet my interest as much as its predecessor. It’s a little too campy and overproduced for my taste. But Johnson’s ingenuity in manipulating conventions of the Golden Age detective stories by Christie, Sayers et al. makes it ripe for the sort of analysis I try out in the book. So here we go.

Needless to say, there are spoilers for Glass Onion and Knives Out. But I bet you’ve seen both films.

Tools of the trade

Knives Out.

Plotting a story is a craft, and it has some essential tools. There is, for instance, the ordering of events. Will you present events in linear story sequence, or will you arrange them in a nonchronological pattern? You can’t avoid choosing one or the other or some combination of the two.

There’s also the matter of viewpoint. Will you attach the audience to what a single character experiences, or will you roam among several characters?

And there’s segmentation: How will you break your plot up into chunks? In literature, we have sentences, paragraphs, and chapters. In theatre, scenes and acts. In film, scenes and sequences (and sometimes reels or chapters). Even one-shot movies have moments of pause or shifts of viewpoint that mark off phases of the action.

These are forced choices that every storyteller must face. It’s these three–linearity, viewpoint, and segmentation–that Perplexing Plots relies on in order to analyze both mainstream storytelling and mystery fiction.

In addition, the craft requires the audience to be engaged–at least interested, at most emotionally moved. You must choose whether to get your audience to empathize with certain characters or to keep the characters remote and unknowable. Do you want to arouse anger, approval, or some other emotion? You must decide how the choices of linearity, viewpoint, and segmentation can trigger these responses.

For example, your plot can usually build empathy for a character by showing incidents in which that person is treated unfairly. Those actions will be more intense if they’re rendered from the character’s viewpoint. This is what Rian Johnson does in Knives Out when he shows Marta persecuted by the vindictive Thrombey family, and then exploited by Hugh. The disparity in power (David vs Goliath) heightens our sense of indignation and makes the finale seem to be poetic justice (My house/my rules).

Some emotions depend directly on choices about chronological sequence. If your plot signals that some past events are significant but then doesn’t reveal them, you’re using linearity to create curiosity. If the plot summons up anticipations about particular future story events, you create a degree of suspense. If your plot introduces an event that momentarily seems out of keeping with the linear story, you can summon up surprise.

Each of these “cognitive emotions” (“cognitive” because they rely on knowledge and belief) is shaped by perspective and segmentation. Creating curiosity, suspense, and surprise depends on viewpoint: each character will have different states of knowledge about the course of events. In Knives Out, Hugh Drysdale is not suffering curiosity about whodunit: he knows he did it. But because we’re attached to Marta and detective Benoît Blanc, we share their state of uncertainty–and suspense about what may come.

Similarly, decisions about segmentation will often be made based on the cognitive emotions in play. You might end a book chapter or a play’s act or a film’s scene on a note of curiosity (“Then whose body is in that grave?”), suspense (the stalker draws near the prey), or surprise (“I’m your father!”).

As my examples from Knives Out suggest, the three tools I’ve picked out have special purposes in a mystery story. Perhaps one reason for the enduring popularity of mystery as a narrative device is its ingenious use of linearity, viewpoint, and segmentation to build cognitive emotions, especially curiosity. But a perennial problem of the genre is to build up other emotions. So we need sympathetic detectives and victims along with unsympathetic suspects, cops, and gangsters to engage us. Some writers also vamp up the suspense factor by putting the investigator in danger, a hallmark of hardboiled stories and domestic psychological thrillers (Rinehart, Eberhart, and their modern counterparts). Perplexing Plots traces some of these creative options through the history of mystery fiction.

Hidden stories

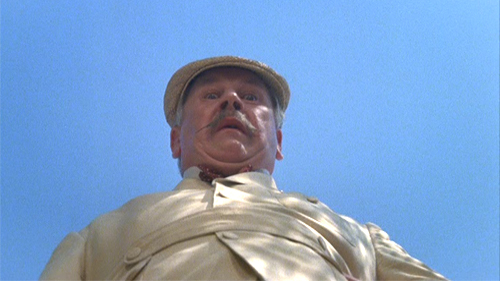

Evil Under the Sun (1982).

The mystery plot centered on an investigation tells two partial and overlapping stories. The investigation is presented as an effort to disclose what happened in the past, an incomplete and puzzling chain of events. Writers in the 1920s started to call this “the hidden story.”

In the standard case, the detective reveals those events and makes a single continuous story out of everything. The revelation is typically saved for the climax of the present-time story line, with the detective explaining the missing events in a summing-up. Often all the suspects are gathered and the detective reviews the evidence before presenting the solution to the puzzle. In other instances, the detective may confide the results to a friend or an official.

The summing-up is often a verbal performance, with the detective recounting the hidden story. A classic example is the Christie novel Evil Under the Sun (1941), in which Hercule Poirot explains to the assembled suspects how the crime was committed. To make this scene less monotonous onscreen, filmmakers often illustrate the hidden story by brief flashbacks, as in the 1982 film adaptation of the Christie novel. Johnson employs this strategy in Knives Out, supplying quick shots of how Hugh’s scheme was enacted.

The detective’s explanation often rests on yet another hidden story line: parts of the investigation we didn’t see. Very often the detective operates backstage, pursuing clues we didn’t notice. Sherlock Holmes absents himself for a good stretch of The Hound of the Baskervilles, leaving Watson to explore the mystery of the Moors. Only later do we learn what Holmes was up to. Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe likes to keep his assistant Archie, our narrator, ignorant of information that he asks other operatives to dig up for him.

As a result, in the final summing-up, the detective’s filling in of the plot may include telling us of his offstage busywork. Again, that may be rendered on film as flashbacks to make sure the audience appreciates the sleuth’s cunning. These might include flashbacks that replay parts of the inquiry, but from a new viewpoint. In the film version of Evil Under the Sun, we see Poirot’s first visit to the cliff’s edge.

But the replay during his summing up expands this by dwelling on the vertiginous effects he feels.

In Glass Onion, Johnson finds a fresh way to treat the detective’s offstage machinations, and that depends, as you’d expect, on exploiting the three basic tools.

A package of puzzles

The most obvious innovation involves segmentation. Johnson splits his plot into two almost exactly equal halves. The first, running about seventy minutes, is a more or less complete classic puzzle.

Tech magnate Miles Bron invites his old friends for a weekend party on his private island. Their affinities go back to their days hanging out together in a pub, the Glass Onion. A fifth friend, Cassandra “Andi” Brand, co-founded Alpha with Miles, but he cheated her out of her share when she refused to expand into questionable paths. Andi shows up at the island to join what Miles calls the Disruptors. There’s Claire, an ambitious politician; Lionel, a scientist working for Miles on a new energy source; Birdie, a scatty fashionista; and Duke, an aggrieved online spokesman for patriarchy. Famous detective Benoît Blanc joins the party, even though it’s unclear who invited him.

These characters are introduced in a rapid opening sequence that shuttles us from one to the other as each gets a puzzle box. Crosscutting and split-screen imagery yield an omniscient narration; we seem to know everything. Johnson points out the expositional advantages: “The box gave it an element of fun, a spine, and a way for all the characters to be on speaker phone solving the mystery of how to open it together, so you see the dynamics between them in real time.”

Then we see a so-far unnamed woman receive a box and break it open. Finally we find Blanc himself, stewing in boredom in his bathtub. In all, a shifting spotlight has introduced us to all but one of the major characters.

Once the group assembles on the pier to board the ship that will take them to Miles’s island, the narration narrows its range and concentrates mostly on Blanc’s reactions.

In what follows, Blanc observes the others, occasionally trailing them, and asks questions about their pasts. By and large, this half of the film will be attached to him, though sometimes the narration will stray briefly to others (chiefly to give each a motive for killing Miles). The first half assigns Blanc the conventional role of curious investigator.

Miles has planned a murder game in which he’s the victim, but that puzzle collapses the first evening when Blanc solves it instantly. A new crime emerges: Duke abruptly dies of poisoning. And soon someone shoots Andi. Blanc gathers the suspects and announces he nearly has a solution. “It’s time I finished this. . . . Only one person can tell us who killed Cassandra Brand.”

In the spirit of Golden Age whodunits, Johnson has poured out a cascade of mysteries, big and small. Who sent Blanc the extra box? Why did Andi, still smarting from her courtroom loss to Miles, show up at his party? When Duke died, he drank from Miles’s glass, so who was trying to kill Miles? Duke’s pistol mysteriously disappears; who took it? The same person who killed Andi?

Johnson’s narration can be both reliable and unreliable. During the drinking session a quick long shot reveals that Miles forced Duke to take the poisoned glass. This is a daring gesture toward Fair Play (that some of us noticed), but Johnson will try to cancel our impression. He will soon offer a lying replay to blot this out.

To further swerve suspicion from Miles, Johnson uses viewpoint. We see Miles reacting in shock to a POV image of the fallen glass with his name on it, as if he were just realizing he, not Duke, was the target.

Of course he’s faking, but by privileging his viewpoint in order to underscore his reaction Johnson suggests he’s innocent. Cheating? Not really, just misleading. Johnson gives with one hand, takes away with the other–as his mentor Agatha Christie does in prose (as I try to show in the book).

Fugue states

So Blanc has a lot to explain. But instead of continuing the traditional summing-up denouement, Johnson pauses and in effect replays the first half of the film by concentrating on the detective’s offstage activities.

Turns out, Blanc has been much busier and less naive than he seemed in the first part. A conventional assembly-of-the-suspects climax would have included explanations of his scheming, but Johnson daringly fleshes these out to forty minutes that annotate scenes that we’ve already witnessed. In this play with linearity, gaps are filled, and new information is provided.

The second part starts with a young woman delivering the wrecked puzzle box to Blanc. She is not Andi but her twin sister Helen. (Yes, Johnson unblushingly taps the convention of false identity, with twins no less.) Andi is dead, killed by carbon-dioxide fumes in her garage. Helen suspects not suicide but murder and gives Blanc an account of Andi’s career through flashbacks. These bursts of nonlinearity skip freely from the gang’s youthful days to Miles’s cheating of Andi.

Moved, Blanc coaxes Helen to impersonate Andi and go to the party, as if accepting Miles’s invitation. (Blanc will convince the authorities to suppress news of Andi’s death for a time.) The two of them form a team to investigate Miles’s posse and find Andi’s killer. So now two puzzles–who sent Blanc the box? why did Andi, or rather “Andi,” show up at the island?–are set to rest. Just as important, as Knives Out focused our empathy on Marta, this second half gives us Helen as a sympathetic figure, so the puzzle element is enhanced by emotion.

Blanc’s saunters around the compound are now replayed as more purposeful, while “Andi” stands revealed not simply as an intruder but a snoop. Some scenes are only sampled, while others are fleshed out through viewpoint shifts. In addition, the narration offers hypothetical flashbacks when Helen and Blanc play with the possibilities of who might have killed Andi.

Driving the second part is the search for a crucial piece of evidence that would have won Andi the court case: the Glass Onion napkin on which she jotted down a plan for the company. After the trial she found it and told Miles’s circle; her murder was triggered by the killer’s plan to recover the napkin. When Helen finds it, she can confront Miles. In a final twist, it’s revealed that the bullet that apparently killed Helen was blocked by Andi’s diary. At her return to the group, Blanc can launch a proper summing-up and denunciation of the guilty.

The annotated replays run about 37 minutes. These incidents could have been much more concisely presented as part of Blanc’s explanation, but as Jason Mittell pointed out to me, this new plot structure gives the second part a dynamic we associate with another genre: a film tracing a big con, like The Sting. There’s a pleasure in seeing how scenes we interpreted one way now stand out as manipulated by Blanc and Helen.

Blanc’s explanations, and Miles’s efforts to block it, take another sixteen minutes. Eventually the Disruptors unite to support Andi, and Miles is facing murder charges. The film ends not with a shot of the complacent Blanc but of the righteous Helen/Andi, the co-protagonist of the second part, a figure of vengeance and vindication.

Replays that amplify and contextualize scenes we’ve already seen are common in mysteries and other genres. Johnson’s originality comes in building one long segment out of such replays. To make it work he relies on our memory of the chronological order of previous scenes to create a double-entry plot structure in which the detective’s backstage scheming revises and corrects our perception of the core action. You could lay out the action on a table of the sort I occasionally resort to in Perplexing Plots.

Johnson’s pride in folding the second half of the film back over the first part is teased when a guest at Birdie’s party explains the fugue that Miles has embedded in the puzzle box. “A fugue is a beautiful musical puzzle based on just one tune. If you layer this tune on top of itself, it starts to change and turns into a beautiful new structure.”

Johnson’s virtuoso play with segmentation has a place in the mystery story tradition; Perplexing Plots reviews several Golden Age examples. (One somewhat similar novel is Richard Hull’s Excellent Intentions of 1938.) You can imagine a version of Glass Onion that attaches its viewpoint to Blanc and Andi from the start, with the “infiltration” strategy of something like Notorious (1946) or Mission: Impossible II (2000). But that wouldn’t engage us through its gamelike, self-consciously artificiality. No film I can recall has so thoroughly routed the offstage activities of the detective onto a track parallel to that of the unfolding crime. Creating a double-column plot like this shows not only the cleverness of design demanded by mystery stories but something I stress throughout the book: the eager drive of popular storytelling toward innovation and novelty–within familiar boundaries.

Thanks to Jason Mittell for a stimulating correspondence and to Erik Gunneson and Peter Sengstock for further suggestions.

Johnson discusses how he shaped the guest assembly on the pier around Blanc’s viewpoint in “Notes on a Scene” in Vanity Fair. A lengthy piece in Vulture explains some of the citations and in-jokes in the film.

P.S. 13 January: Thanks to Antti Alanen and Fiona Pleasance for correction of two names!

Glass Onion.

Ellery who?

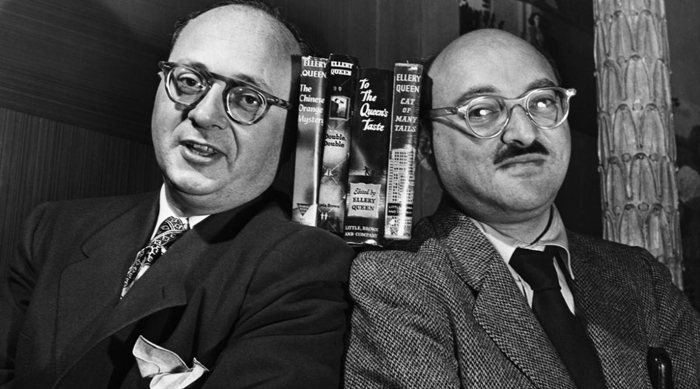

Manfred Lee and Frederic Dannay.

DB here:

My new book, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder, offers many critical discussions of classic mystery writers. But I couldn’t include every writer or work that interested me. So occasionally I’ll post blog entries that will fill in areas I skipped over. Some portions of the book analyzed work by Ellery Queen, but here I want to fill in some gaps–and remind contemporary readers of two writers who deserve more attention than they currently attract.

Many best-selling novels of the 1930s and 1940s in America remain familiar to us, if only because movies were made from them: Gone with the Wind, The Good Earth, Lost Horizon, The Grapes of Wrath, Mrs. Miniver, The Robe, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Forever Amber, The Razor’s Edge, The Naked and the Dead, and others. Maybe you’ve even read some of the books. But many best-sellers don’t endure. What about Singing Guns (Max Brand), Fast Company (Marco Page), Earth and High Heaven (Gwethalyn Graham), and The Forest and the Fort (Hervey Allen)?

Many best-selling novels of the 1930s and 1940s in America remain familiar to us, if only because movies were made from them: Gone with the Wind, The Good Earth, Lost Horizon, The Grapes of Wrath, Mrs. Miniver, The Robe, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, Forever Amber, The Razor’s Edge, The Naked and the Dead, and others. Maybe you’ve even read some of the books. But many best-sellers don’t endure. What about Singing Guns (Max Brand), Fast Company (Marco Page), Earth and High Heaven (Gwethalyn Graham), and The Forest and the Fort (Hervey Allen)?

In particular, what about The Dutch Shoe Mystery, The Egyptian Cross Mystery, The Chinese Orange Mystery, and The New Adventures of Ellery Queen? Each of these had sold over 1.2 million copies by 1945. Scarcely anyone today remembers them, or recognizes their author’s name.

Yet eighty years ago they were part of a multimedia franchise. The books bearing the “Ellery Queen” byline were said to have sold over ten million copies by the end of World War II. There was a spinoff juvenile series by “Ellery Queen, Jr.” and some comic books. There were nine Ellery Queen films and a weekly radio series that ran sporadically from 1939 to 1948, along with “Ellery Queen’s Minute Mysteries.” The Queen name adorned countless anthologies of mystery short stories, and Ellery Queen’s Mystery Magazine, still the most prestigious venue for short mystery fiction, was founded in 1941. You couldn’t visit a newsstand or bookstore without seeing the Queen name.

“Ellery Queen” was the pseudonym of two Brooklyn cousins, Frederic Dannay (né Daniel Nathan) and Manfred B. Lee (né Emanuel Benjamin Lepofsky), both born in 1905. While working in advertising, they collaborated on a mystery novel they submitted for a magazine prize. It won, but the magazine went out of business, so The Roman Hat Mystery was brought out as a book in 1929. Dannay and Lee took up detective fiction in earnest, turning out at least one book a year during the 1930s.

Sensitive to the power of PR, they built up the enigma of the author’s identity, with one or the other sometimes giving a lecture in a mask. When they started another series as by “Barnaby Ross,” the two would appear masked and debate one another. (Shamelessly, Queen wrote a newspaper article praising a Ross novel.) By 1939, they embraced radio and films as major vehicles for their brand, and so their pace of book publishing slackened while they churned out screenplays and radio scripts.

Sensitive to the power of PR, they built up the enigma of the author’s identity, with one or the other sometimes giving a lecture in a mask. When they started another series as by “Barnaby Ross,” the two would appear masked and debate one another. (Shamelessly, Queen wrote a newspaper article praising a Ross novel.) By 1939, they embraced radio and films as major vehicles for their brand, and so their pace of book publishing slackened while they churned out screenplays and radio scripts.

Construed most narrowly, the Queen reign lasted from 1929 to 1958, with The Finishing Stroke taking us back to the days of the first novel. The cousins’ biggest bestsellers were 1930s titles reissued during the 1940s boom in paperbacks. Thereafter they were beset by money troubles and poor health, and so were forced to keep turning out product.

After 1958 the result was a bewildering array of books of varying authorship. Lee had a spell of writer’s block, while publishers pressed them for less detection and more straight crime. Ghost writers produced non-Ellery mysteries under the Queen name and historical novels under the Ross pseudonym. Dannay plotted one novel written by a ghost, while Lee was able to rejoin him for other novels such as Face to Face (1967) and their last joint effort A Fine and Private Place (1971). After Lee died in 1971 and Dannay’s wife died a year later, Dannay brought the series to a close.

For many years the books were out of print, but Otto Penzler, always vigilant for ways to keep the great traditions alive, began bringing out uniform editions (including the ghost-written books) in 2018. Before that, probably the most vivid reminder of the saga was the NBC television series of 1975-1976, starring Jim Hutton and David Wayne. I’ve been surprised by the number of people who remember it fondly. But the books? Not so much. Which is a pity.

From cold logic to social comment

In his definitive Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection, Francis M. Nevins has argued that the saga develops in four phases. First, there are the pure puzzles–complex crimes demanding elaborate solutions. (Hence the titles flaunting the “mystery” of this or that.) The stories abide strictly by the fair-play principles articulated in Golden Age precept: a careful reader should have all the information necessary to solve the case. The novels flaunted this premise with the famous “Challenge to the Reader” inserted before each climax.

As befits puzzle plots, Phase 1 presents Ellery as a drawling, bloodless intellectual, flaunting his erudition in the manner of the then-popular and more insufferable Philo Vance of S. S. Van Dine. At the same time Lee and Dannay establish some of the devices they’ll use again and again. We encounter cryptic dying messages, missing clues (the dog that doesn’t bark in the nighttime), tempting false solutions, and murderers with a penchant for elaborate crimes. Dannay’s plotting is intricate, but the clarity of Lee’s prose (and his willingness to repeat information) helps the whole contraption work.

As the early books go along, Ellery becomes somewhat less priggish, but he gets quite down to earth in Phase 2, at the end of the 1930s. The plots loosen up, Ellery gains a (mild) sex life, and the romantic escapades of secondary couples occupy more space. Why? Mystery writers were discovering that serializing or condensing their novels in slick-paper magazines could yield big financial rewards. This market, aimed chiefly at women and families, discouraged the pure puzzle and urged more emphasis on characterization. The cousins managed to sell The Devil to Pay (1938) and The Four of Hearts (1938), intrigues set in Hollywood, as condensations to Cosmopolitan.

As the early books go along, Ellery becomes somewhat less priggish, but he gets quite down to earth in Phase 2, at the end of the 1930s. The plots loosen up, Ellery gains a (mild) sex life, and the romantic escapades of secondary couples occupy more space. Why? Mystery writers were discovering that serializing or condensing their novels in slick-paper magazines could yield big financial rewards. This market, aimed chiefly at women and families, discouraged the pure puzzle and urged more emphasis on characterization. The cousins managed to sell The Devil to Pay (1938) and The Four of Hearts (1938), intrigues set in Hollywood, as condensations to Cosmopolitan.

Phase 3 Queen, throughout the 1940s and early 1950s, is generally considered the pinnacle of the series. Endowed with literary ambitions and a range of cultural references, the books showed a new depth of psychological, political, and social sensitivity. In the space I have today, I pick out my favorites, each of which has been considered by one critic or another as Queen’s best. Among their distinctions, they show Dannay experimenting with what we would call “worldmaking” and Lee exploring new stylistic resources. All make invigorating reading today.

“Mr. Queen Discovers America” is the title of the opening chapter of Calamity Town (1942). Ellery gets off the train in Wrightsville, a small New England town. He has come to find a quiet place to write his next novel, and Wrightsville’s apple-pie ordinariness makes it the ideal sanctuary. It’s apparently as pure as the Grover’s Corners of Wilder’s play Our Town (1938) and the idealized Carville of the Andy Hardy movies; the same folksy milieu would figure in William Saroyan’s Human Comedy (book and film, 1943). Ellery manages to rent a house next to the town’s first family, the Wrights, and he’s taken into their social circle.

Quickly the novel activates another motif of American popular culture: the sinister forces that seethe underneath a small town’s cheery surface. This runs back to Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) and Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) right up to Blue Velvet (1986) and TV shows like Twin Peaks and Fargo. In Calamity Town, the Wrights’ household is disrupted by the return of one daughter’s runaway fiancé and the couple’s sudden marriage. But soon murder intervenes and vicious gossip swallows up the family in scandal. At the end of the book, Ellery reflects, “There are no secrets or delicacies, and there is much cruelty, in the Wrightsvilles of this world.” The Wright family is shattered, and the shocking solution forces Ellery to realize he could have prevented a murder consummated before his eyes.

the novel activates another motif of American popular culture: the sinister forces that seethe underneath a small town’s cheery surface. This runs back to Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) and Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919) right up to Blue Velvet (1986) and TV shows like Twin Peaks and Fargo. In Calamity Town, the Wrights’ household is disrupted by the return of one daughter’s runaway fiancé and the couple’s sudden marriage. But soon murder intervenes and vicious gossip swallows up the family in scandal. At the end of the book, Ellery reflects, “There are no secrets or delicacies, and there is much cruelty, in the Wrightsvilles of this world.” The Wright family is shattered, and the shocking solution forces Ellery to realize he could have prevented a murder consummated before his eyes.

In plotting the book, Dannay provided Lee a panorama wider than they had used before. Calamity Town has dozens of named characters, mostly serving as local color but many playing important roles. The mystery itself is less complex than those in Phase 1, but the book is filled out with a cross-section of life in Wrightsville. Low Village is populated by:

people named variously O’Halleran, Zimbruski, Johnson, Dowling, Goldberer, Venuti, Jacquard, Wladislaus, and Broadbeck–journeyman machinists, toolers, assembly-line men, farmers, retailers, hired hands, white and black and brown, with children of unduplicated sizes and degrees of cleanliness. . . . Mr. Queen’s notebook was rich with funny lingos, dinner-pail details, Saturday-night brawls down on Route 16, square dances and hep-cat contests, noon whistles whistling, lots of smoke and laughing and pushing, and the color of America, Wrightsville edition.

This Capraesque vision of vibrant Americana, coming early in the book, is questioned immediately by Lola, the renegade Wright daughter, who calls her town “wormy and damp, a breeding place of nastiness.” Lee’s task is to show both sides of Wrightsville through incidents tracing the town’s reaction to the murder. Ellery is always captivated by the calendar-image look of the place, as when in winter it resembles a Grant Wood painting.

But in town there were people, and sloppy slush, and a meanness in the air; the shops looked pinched and stale, everybody was hurrying through the cold; no one smiled. In the Square they had to stop for traffic; a shopgirl recognized Pat and pointed her out with a lacquered fingernail to a pimpled youth in a leather storm-breaker.

Lee rose to the challenge of portraying the fragility of a social network that can’t respond to a shock to placid lives.

The result is the most wide-ranging and emotionally complex book in the Queen franchise so far. The cousins were unable to sell it for serialization, and from then on, no slick magazines bought a Queen novel for many years.

Class relations and inner turmoil

The Murderer is a Fox (1945) takes Ellery back to Wrightsville, but under very different circumstances. Pilot Davy Fox is welcomed back home for his outstanding record in killing the enemy and rescuing his comrades. But like many a returning vet he has PTSD, which emerges as an urge to strangle his wife Linda. The couple consult Ellery, who speculates that Davy is haunted not just by his combat experiences but by the fact that his father Bayard was imprisoned for poisoning his mother.

In order to investigate the case, Ellery persuades the authorities to release Bayard under supervision. He must answer the question: Who poisoned the grape juice that Jessica Fox drank–and shared with others–on the fateful day? Suspects include Bayard’s brother Talbot, his wife Emily, a duplicitous pharmacist, an overbearing cop, and a few others. Dannay’s plotting is intensely focused on a middle-class family quite different from the patrician Wrights, and Lee’s problem is to fill out a fairly minimal situation to novel length.

In order to investigate the case, Ellery persuades the authorities to release Bayard under supervision. He must answer the question: Who poisoned the grape juice that Jessica Fox drank–and shared with others–on the fateful day? Suspects include Bayard’s brother Talbot, his wife Emily, a duplicitous pharmacist, an overbearing cop, and a few others. Dannay’s plotting is intensely focused on a middle-class family quite different from the patrician Wrights, and Lee’s problem is to fill out a fairly minimal situation to novel length.

Lee’s solution is to recast his narrational approach, turning the book’s first section into a suspense thriller. For once our viewpoint isn’t initially attached to Ellery. The opening chapters alternate the Fox family awaiting Davy’s train with scenes of Davy on board. All the scenes are deeply subjective, with flashbacks plunging us into the family background and, more harrowingly, Davy’s war experiences. The seamy side of Wrightsville is exposed again and again. Against the bunting and chattering crowd of the train-station homecoming welcome, with the American Legion band “tossing the sun from their silver helmets,” Lee replays Davy’s memories of his father’s shame.

How Davy loathed them, the jeering kids. Because they had known, the whole town knew. The kids and the shopkeepers in High Village and the Country Club crowd and the scrubskinned farmers who drove in on Saturdays to load up–even the hunks and canucks who worked in the Low Village mills. Especially the shop hands of Bayard & Talbot Fox Company, Machinists’ Tools, who merely jeered the more after the Bayard & one day vanished from the side of the factory, leaving a whitewashed gap, like a bandage over a fresh wound.

Asked on the train about the thrills of battle, Davy conjures up:

Being caught on the ground with Zeros twisting and tumbling all over the sky and falling flat on your face in the stinky guck of a Chinese rice field, or pulling Myers out of his cockpit with his stomach lying on his knees after he brought his old P-40 down only God knows how. . . . Having your coffee grinder conk in the middle of a swarm of bandits and belly-landing in scrub on the knife-edged hills–seeing Lew Binks’s coffin drop like lead aflame, and Binks hitting the silk, trustful guy, and then the hornet Japs zapping around him with their spiteful traces hemstitching the sky.

Obliged to evoke the war, Lee summons up a muscular, sometimes lyrical prose unknown in the books of Phases 1 and 2.

Davy’s trauma turns the early chapters into an account of a man driven to murder. Like other novels and films of the 1940s, The Murderer is a Fox shares his nightmares and dissects his compulsion. While a loving, confused Linda tries to lure Davy into an embrace, he struggles to keep away from her.”The game was to stay in his bed. To stay in his bed so that he would not go over to the other bed and obey the prickling of his thumbs. . . . “

The viewpoint shifts to Ellery once he starts to reconstruct how Jessica might have died. In the course of this, family indiscretions are exposed and characterization deepens. In particular, Bayard is revealed as a man of severe principle, who stoically accepts a life sentence of murder. Revealing the true cause of Jessica’s death leads Ellery to a conclusion that could become another Wrightsville scandal. The book ends with Ellery smiling grimly at the prospect of one secret that the town gossip will never exhume.

In Phase 3, Dannay indulged his penchant for elaborate “pattern mysteries,” crimes based on cultural givens like the alphabet, dates of the year, nursery rhymes, and the like. But this ploy demands either a madman (driven by obsession with the pattern) or a super-schemer. Knowing that the pattern would attract the hyperintellectual Ellery, the schemer could then frame someone else as being enslaved to it. Ellery will then confidently call out the wrong suspect, with sometimes dire consequences.

This tendency toward a master-mind, an omniscient “player on the other side,” is at the center of Ten Days’ Wonder (1948). Now a new layer of Wrightsville society is peeled back. Plutocrat Diedrich Van Horn is an industrialist who has indulged his son Howard in every way. But Howard is plagued by bouts of amnesia and tendencies toward suicide. Worse, he has fallen in love with Diedrich’s young wife Sally, and they have committed adultery. A blackmailer has discovered their affair and they are terrified that their love letters will be exposed. Into this Oedipal scenario steps Ellery, whom the couple beg to help them. Against his better judgment, he agrees.

Now the social landscape of Wrightsville matters less than the labyrinth of psychosexual tensions that Ellery confronts. He has to play double agent. For Diedrich, he is an innocent guest writing his new novel in lavish seclusion. For others, he becomes a go-between to save the couple. Inevitably, the blackmail plot deepens and Ellery is obliged to lie to the police and the townsfolk. The whole situation spirals into an orgy of betrayal and murder that leads Ellery to a false solution based on a monstrously blasphemous pattern of crimes. He eventually realizes that his ingenuity makes him profoundly predictable, and manipulable. Ellery confesses to the player on the other side:

Now the social landscape of Wrightsville matters less than the labyrinth of psychosexual tensions that Ellery confronts. He has to play double agent. For Diedrich, he is an innocent guest writing his new novel in lavish seclusion. For others, he becomes a go-between to save the couple. Inevitably, the blackmail plot deepens and Ellery is obliged to lie to the police and the townsfolk. The whole situation spirals into an orgy of betrayal and murder that leads Ellery to a false solution based on a monstrously blasphemous pattern of crimes. He eventually realizes that his ingenuity makes him profoundly predictable, and manipulable. Ellery confesses to the player on the other side:

“You’ve destroyed me. . . . You’ve destroyed my belief in myself. How can I ever again play little tin god? . . . It’s not in me . . . to gamble with the lives of human beings.”

Dannay planned this bleak book as the last in the Queen saga.

Appropriately, Lee’s prose texture matches the introspective bent of the plot. The subjective narration applied to Davy Fox is now given to Ellery, in a moment-by-moment italicized inner monologue that heightens his reaction to Howard’s and Sally’s situation. Howard says he was the seducer:

“I was the one who made the love, who kissed her eyes, stopped her mouth, carried her into the bedroom.”

Now we show the wound, now we pour salt on it.

Lee’s technique builds up the suspense when Ellery responds mentally to new plot twists.

“Last night there was another robbery.”

Last night there was another robbery.

“There was? But this morning no one said–“

“I didn’t mention it to anyone, Mr. Queen.”

Refocus, but slowly. . . .

“The cash is missing.”

Cash. . .

The inner monologue also passes bitter judgment.

“I could tell him and say I wanted him to divorce Sally and that I’d marry her, and if he hit me I could pick myself up from the floor and say it again.”

I believe you could, Howard. And even get a sort of pleasure from it.

Italicized inner monologues and streams of consciousness became common in popular fiction from the 1920s on, as Perplexing Plots explains. Lee came late to this technique, but he fitted it perfectly to a story that, more deeply than any other, traces the agonizing tensions that confront Ellery as someone meddling in human affairs he doesn’t fully grasp. Dannay said that he designed Ten Days’ Wonder as “an exposure of detective novels and of fictional detectives.”

Cat on the prowl

Between The Murderer is a Fox and Ten Days’ Wonder came a smaller-scale exercise in worldmaking, There Was an Old Woman (1943). Shoe magnate Cornelia Potts rules as eccentric matriarch over a family of ill-assorted children and others. Their estate consists of a gigantic bronze shoe on a pedestal, a tower in which daughter Louella concocts her mad experiments, and a cottage enclosing Horatio, a man who has decided to live in perpetual boyhood. The eldest son Thurlow occupies his time fruitlessly suing outsiders who appear to disrespect him. More normal are the three youngest children Bob, Mac, and Sheila, all despised by old Cornelia.

With its pattern based on the nursery rhyme, the novel offers another version of the devious master-mind trapping Ellery. But it remains somewhat awkward in its uneasy mix of zany comedy and serious murder. (Nevins plausibly suggests that Dannay was trying something akin to the screwball mysteries of Craig Rice.) A tacked-on ending shows Ellery gaining his secretary-girlfriend Nikki Porter, already a mainstay of the films and radio plays. But the effort to create an enclosed milieu of domestic fantasy, which Dannay sometimes called “Ellery in Wonderland,” fits Dannay’s urge, seen more earnestly in the Wrightsville tales, to expose the vulnerability of the supersleuth who must confront the occasional illogicality of the world.

With its pattern based on the nursery rhyme, the novel offers another version of the devious master-mind trapping Ellery. But it remains somewhat awkward in its uneasy mix of zany comedy and serious murder. (Nevins plausibly suggests that Dannay was trying something akin to the screwball mysteries of Craig Rice.) A tacked-on ending shows Ellery gaining his secretary-girlfriend Nikki Porter, already a mainstay of the films and radio plays. But the effort to create an enclosed milieu of domestic fantasy, which Dannay sometimes called “Ellery in Wonderland,” fits Dannay’s urge, seen more earnestly in the Wrightsville tales, to expose the vulnerability of the supersleuth who must confront the occasional illogicality of the world.

That urge finds its fullest expression in Cat of Many Tails (1949). Bearing the traces of police procedural films like Naked City (1948), this presents a serial killer stalking apparently random victims through Manhattan. Men and women, white and Black, are found strangled with cords of tussah silk. Although he withdrew from criminal affairs after his failure in Ten Days’ Wonder, Ellery is pressed to serve as the public face of the investigation. Facing several million suspects, he is baffled, forced to wander the streets, revisiting the crime scenes obsessively, imagining the victims meeting their fate.

Ellery eventually discloses the pattern behind the killings, but the novel’s development is dominated by a vision of a city under siege and citizens responding in panic. Lee responds with a narrative panorama far exceeding what we saw in his treatment of Wrightsville. He surveys Manhattan neighborhoods high and low. The victims are given detailed lives and routines and backstories; their friends and family are characterized as well. Here is a potential victim’s father:

Frank Pellman Soames was a skinny, squeezed-dry-looking man with the softest, burriest voice. He was a senior clerk at the main post office on Eighth Avenue at 33rd Street and he took his postal responsibilities as solemnly as if he had been called to office by the President himself. Otherwise he was inclined to make little jokes. He invariably brought something home with him after work–a candy bar, a bag of salted peanuts, a few sticks of bubble gum–to be divided among the three younger children with Rhadamanthine exactitude. Sometimes he brought Marilyn a single rosebud done up in green tissue paper. One night he showed up with a giant charlotte russe, enshrined in a cardboard box, for his wife.

The shifts in public response are charted through vivid, often frightening incidents. People stay home or avoid dark streets. Vigilante groups form. The press goes wild, keeping readers in tension with cartoons of a cat stalking the city and brandishing tails like nooses. All of this comes to smash in a virtuoso chapter describing a town meeting at which, when a woman screams, and the crowd becomes a stampeding mob.

The shifts in public response are charted through vivid, often frightening incidents. People stay home or avoid dark streets. Vigilante groups form. The press goes wild, keeping readers in tension with cartoons of a cat stalking the city and brandishing tails like nooses. All of this comes to smash in a virtuoso chapter describing a town meeting at which, when a woman screams, and the crowd becomes a stampeding mob.

“HE’S HERE!”

Like a stone, it smashed against the great mirror of the audience and the audience shivered and broke. Little cracks widened magically. Where masses had sat or stood, gaps appeared, grew rapidly, splintered in crazy directions. Men began climbing over seats, using their fists. People went down. The police vanished. Trickles of shrieks ran together. Metropol Hall became a great cataract obliterating human sound.

On the platform the Mayor, Frankburner, the Commissioner, were shouting into the public address microphones, jostling one another. Their voices mingled, a faint blend, lost in the uproar.

The aisles were logjammed, people punching, twisting, falling toward the exits. Overhead a balcony rail snapped; a man fell into the orchestra. People were carried down balcony staircases. Some slipped, disappeared. At the upstairs fire exits hordes struggled over a living, shrieking carpet.

Suddenly the whole contained mass found vents and shot out into the streets, into the frozen thousands, in a moment boiling them to frenzy. . . .

Dannay gave Lee the chance to compose scenes of cinematic excitement. No wonder the cousins thought that this novel might sell to the movies.

This extroverted narration is counterweighted by Ellery’s deepest plunge into self-analysis. Once more his proposed solution fails and leads to more deaths, and he is left feeling only a sense of waste. He consults an old psychoanalyst to confirm his conclusion and confess his inadequacy. “I’m too late again. . . . All right, I’m really through this time. I’ll turn my bitchery into less lethal channels. I’m finished, Herr Seligmann.” After consoling him that his efforts were not in vain, Seligmann says: “You have failed before, you will fail again. This is the nature and the role of man.” And he reminds Ellery of humility and mortality: “There is one God; and there is none other but he.” After this, as subsequent novels show, Ellery is able to go on–fallible but still holding to an ideal of truth.

For many critics, Cat of Many Tails is the cousins’ supreme accomplishment, a tour de force of mystery, suspense, and social and psychological observation. Their correspondence shows them at the absolute nadir of their relationship, exchanging long, hurtful letters about their disagreements. Yet their rancorous disputes yielded a novel that holds up better than much crime fiction of the 1940s. It’s a remarkable instance of how the “pure puzzle” story could, over the years, mutate into something rivaling the best of “prestige fiction”–an entertainment that is also an ambitious, moving literary achievement. Many mysteries are forgettable. This one is not.

Other Queen novels of Phase 3 are well worth reading. I’m a particular fan of The Scarlet Letters (1953), where Ellery intuits the solution watching a workman paint the G of “logical” in the sign for the New York Zoological Garden. Nevins considers Phase 4, which includes the more strained and fantastic puzzles of the late years, as of interest but not on a par with 3, and I’d agree. Still, the overall career of two Brooklyn cousins across four decades remains a major achievement of the American detective story, and a powerful lesson in how flexible and engaging popular storytelling can be.

Thanks to members of the UW Filmies for answering questions about their familiarity with Ellery Queen.

My figures on American bestsellers are derived from Alice Payne Hackett, Fifty Years of Best Sellers (Bowker, 1945) and subsequent editions of this book, as well as Frank Luther Mott, Golden Multitudes: The Story of Best Sellers in the United States (Bowker, 1947).

My photo of a masked Lee (or is it Dannay?) comes from the very curious article by Ellery Queen, “To the Queen’s Taste; or, Judge by Formula,” New York Herald Tribune (16 July 1933), F3. Here Queen proposes a 10-point chart for deciding on how good a mystery is. Barnaby Ross beats Agatha Christie.

To Nevins’ definitive Ellery Queen: The Art of Detection should be added the excellent resource Ellery Queen: A Website on Deduction. Another valiant defender of the Queen canon is Jon L. Breen, who wrote a spirited inquiry into why the books have been neglected by contemporary readers. See “The Ellery Queen Mystery” in the Weekly Standard, reprinted in Breen’s lively collection A Shot Rang Out: Selected Mystery Criticism.

Illuminating correspondence between Dannay and Lee is available in Blood Relations: The Selected Letters of Ellery Queen, 1947-1950 (Perfect Crime, 2012). The informative Wikipedia article lists all the Queen novels, noting the ghosted ones.

A note on names: Dannay and Lee admitted that in their youthful ignorance they didn’t know the slang term queen could refer to a gay man. Ellery, the name of a childhood friend of Dannay’s, evokes New England blue blood. Through the early books, Ellery comes off as a straight WASP. But during Phase 3, Dannay wrote to Lee: “After all, even though we would be subtle about it, the authors of the books are Jews, and in all the deepest senses, so is Ellery Queen the character” (Blood Relations, 93).

A recent example of a film using “Golden Age” principles of fair play is Knives Out, discussed here. I think Lee and Dannay would have approved.

Ellery (Jim Huttton) breaks the fourth wall to extend his “Challenge to the Viewer” in the last episode of the NBC series Ellery Queen Mysteries, “The Adventure of the Disappearing Dagger” (29 February 1976), directed by Jack Arnold.