Manual labors

Friday | March 3, 2023 open printable version

open printable version

The Tin Star (1957).

DB here:

Type “screenplay writing” into Amazon and you’ll get over 6000 hits. Some of those books will be biographies of writers or screenplays of released films. But there’s still a huge number of DIY books with titles like How to Write a Movie in 21 Days and Writing Screenplays That Sell. A lot of people are apparently only one manual away from a finished script.

Screenplay manuals trigger suspicion. Can it really be that easy? Wouldn’t this be a paradise for grifters? A successful writer would hardly share trade secrets, so most of these books would be written by losers and wannabes. And if you read enough of the manuals, you’ll see the inevitable repetition of banalities. Make your protagonist “relatable.” Keep the conflicts going. Try for a twist.

Reading through them can be mind-numbing, but if you’re interested in how filmmakers tell stories, sometimes they can open up your thinking. Or so I’ll argue.

DIY scripting

The tide of manuals rose during the 1910s, when the emerging American studio system was seeking talent. The tide subsided between the 1930s and the 1960s, when screenwriting was contract labor in that system. But as filmmaking turned “independent,” ambitious people outside the industry could break in with an original script. Manuals, most famously Syd Field’s Screenplay (1979), began to pop up, and the market for how-to books expanded. Field’s book remains in vigorous circulation today, among many competitors.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

What should film researchers do with the manuals? Skepticism is warranted. Literary scholars don’t typically consider advice books and columns in The Writer to be significant bodies of evidence. But in other fields, manuals are valuable documents. Art historians study manuals devoted to composition, color preparation, and other techniques. Musicologists find evidence in primers on sonatas and fugues. At bottom, when we want to study craft practices, we look for any evidence we can find about the range of choices available within a tradition.

If your research touches on matters of style, you may find it illuminating to study the way practitioners pick solutions to practical problems. Which is to say that the manuals can point us toward norms. Norms are, I’ve argued, like a menu of more and less preferred options for treating the material. We developed this angle of inquiry in our Classical Hollywood Cinema, and now it seems well-established that the manuals can sometimes point us toward tacit norms of construction or visual style. For examples of how this can work, see Kristin’s Storytelling in the New Hollywood, my The Way Hollywood Tells It, and Patrick Keating’s Hollywood Lighting from the Silent Era to Film Noir. Many of our blog entries have also explored these paths. With screenplay manuals, we just have to be particularly careful to distinguish valuable data from bilge–which means checking the manual’s precept against many films.

And we shouldn’t expect the manuals or professional journals to identify every normalized device. For example, screenwriters now love to start scenes with friends greeting one another with “Hey” and “Hey,” but I doubt that there’s an explicit decision to avoid “Hi.” Similarly, I’ve never found anyone writing in the classic era who mentions the common Hollywood device of the double plot, with one line of action devoted to a goal-oriented activity and another, interdependent one devoted to heterosexual romance. Even the rather elaborate 180-degree classical editing system wasn’t apparently spelled out anywhere; it was learned by imitation and reinforced because it was economical and efficient. People can learn and follow rules that are simply taken for granted as “the way we do things.”

I think my soft spot for the manuals owes a good deal to my long-term affection for one item I saw in a 1913 guide. J. Berg Esinwein and Arthur Leeds’ Writing the Photoplay contains a lot of hints about standard practices of the period, but one of their diagrams changed my basic attitude about silent film technique.

The cinematic stage

In the late 1990s I became interested in the norms of scene staging in early film. I assumed that filmmakers had to call attention to story action without benefit of cutting to closer views, so I tried itemizing in a straightforward way the staging choices that could guide the viewer’s eye.

Many of the choices could be called “theatrical.” Lighting and setting could emphasize an actor’s gesture or facial expression. Performance factors operated as well, especially since actors were typically facing the viewer. Filmmakers’ reliance on these cues seemed to confirm the standard impression that early film was less “cinematic” than what came later.

Yet there were purely pictorial factors in play as well–notably, the placement of figures in the overall image. Composition of the frame, as in painting (and theatre) played a crucial role in guiding our attention.

There was something else. I was fascinated, for reasons sketched here, with the depth that many scenes in “tableau cinema” displayed. Here’s a quick example from Alfred Machin’s Le Diamant noir (1913). The entire film is available from the Belgian Cinematek.

The young secretary Luc is accused of stealing the missing diamond. He protests his innocence, but the accusation will force him to leave the country.

All the cues I’ve mentioned are at work here: centered figure placement, frontally facing characters, attention-grabbing gesture, favorable setting (the rear doorway and curtains highlight Luc’s arrival), and so on. In addition, a tunnel of information bores through the frame, leading from the distance and culminating in action in the foreground.

But this tunnel couldn’t fairly be considered “theatrical,” since if the action were played on a stage, not all viewers would have the optimal view presented in the shot. Most of the audience simply couldn’t see this alignment of players. Theatrical staging tends to be lateral and fairly shallow, so that people sitting in different seats can all see the scene. A good part of planning a stage production is calculating sightlines. But in film, there’s only one sightline, that of the camera lens.

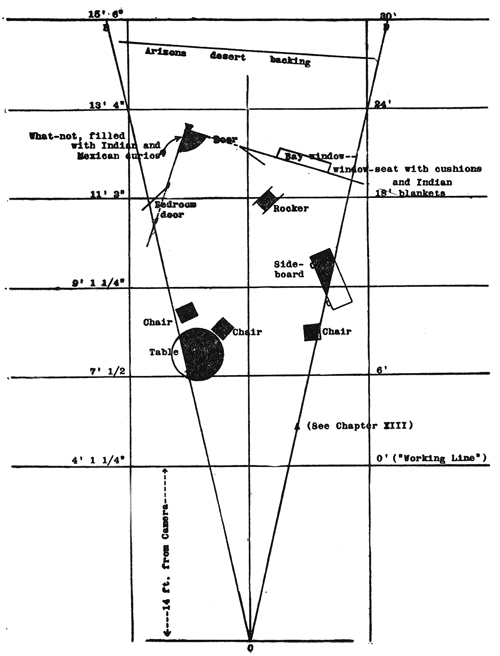

We tend to see film space as cubical, a room with a missing fourth wall. Actually, the playing space–what Esenwein and Leeds call “the photoplay stage”–is a tapering pyramid whose point touches the lens. Because the film image captures an optical projection, the space is narrow but deep. The authors provide a diagram of a scene to explain. (For the sake of clarity, I’ve removed some of their annotations; the full version is on p. 160 of their book.) The effect is of wedge shape that carves into what would be the wide space of a theatre scene.

In 1910s cinema, the camera lens (at point 0) is assumed to be some distance from the “working line,” the layer of maximal attention. For some filmmakers this line was nine or eleven feet from the camera, rather than the 14 feet assumed here. The rest of the space falls away in the distance, and depending on the lens and lighting used, these areas can be in more or less sharp focus. Filmmakers of the period often marked out the pyramid on the studio floor so that actors would know when they were out of shot.

This diagram makes explicit many of our taken-for-granted notions about film space. Someone moving closer to the camera gets larger, of course; but the figure also blocks out more and more of the background as the pyramid narrows. An actor’s forward movement on the stage inevitably takes up a small part of the overall area, but in cinema forward-thrusting action can dominate the frame.

Just as important, the fixity of the lens makes it possible to choreograph actors with a precision impossible in theatre. Luc’s confrontation with his employer in my second frame gives him pride of place, but once he’s slumped at the foreground desk, he can move his head and clear the central zone for us to see a servant waiting in the distance. In tableau cinema, staging isn’t just “blocking.” It’s blocking and revealing, a constant flow of information presented through shifting arrays of figures. I provide several examples in the lecture “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies.”

My heightened awareness of the visual pyramid made me more sensitive to staging in all periods of cinema. We might think that after the tableau cinema period, when filmmakers became more dependent on editing, their reliance on the “photoplay stage” vanished. But of course every shot, close or distant, presents us with the visual pyramid, and some filmmakers relied upon it to provide the graduated layers of space in an edited sequence. Specifically, the “deep focus” that became a favored technique of 1940s cinema around the world would seem a modernization of the principles of the 1910s recognition of wedge-shaped playing space. Here’s an outrageous example from Hawks’ Ball of Fire (1941), shot by Gregg Toland after Citizen Kane.

Less punchy imagery than this suggest that the skills of 1910s staging were never really lost. Another passage from Ball of Fire brings Professor Potts to the foreground in a way reminiscent of Machin’s film. Of course it helps when Gary Cooper is the tallest galoot in the scene.

Cinema’s visual pyramid becomes almost sadistic at the climax of Anthony Mann’s Tin Star (1957). The young sheriff stops a lynching by shaming the town bully. The bully responds as you’d expect, but not in the sort of shot you’d expect.

Mann’s earlier films had experimented with foregrounds thrusting out at the viewer, but this sequence carries the idea to a limit. The actor collapses against the camera, inadvertently proving how lines of cinematic sight converge at the lens–that is, at our viewpoint. Try doing this on the stage!

This entry is more a piece of intellectual autobiography than anything else. I doubt many other people were opened up to the intricacies of staging thanks to a diagram in an old book. I mean it just as an example of how reading manuals can set you thinking about the expressive possibilities of film, and taking you in directions that you couldn’t predict.

More recently, in writing Perplexing Plots, I poked into manuals for would-be fiction writers, an area that literary historians seem to have neglected. These manuals yielded a lot of principles of what people thought went into good storytelling. In particular, I found that while Henry James and Joseph Conrad were making arguments about viewpoint and chronology, so too were people writing how-to manuals. The books indicated a new awareness of these techniques among writers aiming at mass audiences.

Terry Bailey surveys and analyzes early manuals in “Normatizing the silent drama: Photoplay manuals of the 1910s and early 1920s,” Journal of Screenwriting 5, 2 (Jun 2014), p. 209 – 224. For a comprehensive overview, see Steven Price, A History of the Screenplay.

The main argument here is developed in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light: On Cinematic Staging.

Ball of Fire (1941).