Archive for the 'PERPLEXING PLOTS (the book)' Category

Tarantino and the criticism of enthusiasm

Bullitt (1968).

DB here:

Critics who are carried away by a film want to share their excitement. Thus is born what the Cahiers du cinéma writers called a criticism of enthusiasm. The magazine’s editors suggested that the critic who most admired the film should write about it, on the premise that he (almost always a he) would make the best case for it.

Quentin Tarantino’s new book Cinema Speculation (HarperCollins) is a stirring instance of this mode. Fueled by the motormouth intensity of his interviews and the monologues in his movies, the sentences crackle with nerd exuberance.

The eagle-claws-through-the-chest initiation rite in A Man Called Horse blew my fucking mind. As did Barnabas Collins’ blood-squirting slow-motion wooden-stake evisceration in House of Dark Shadows. I remember, during both moments, staring at the screen with my mouth wide open, not quite believing a movie could do that.

Significantly, he took in these and other splendors as a child. Tarantino frames his essays on particular films within a memoir of moviegoing. Now approaching 60, he starts by explaining he started watching films at age 4, accompanying his parents and later the men his mother was dating as a single woman. Seeing the “adult” fare of the 1970s as a small boy gave him a lifelong love of exploitation, crime movies, and Black cinema. For him the Adolescent Window opened early.

The opening chapter culminates in a life-changing visit to Black Gunn, escorted by his mother’s boyfriend Reggie.

The opening chapter culminates in a life-changing visit to Black Gunn, escorted by his mother’s boyfriend Reggie.

To one degree or another I’ve spent my entire life since both attending movies and making them, trying to re-create the experience of watching a brand-new Jim Brown film, on a Saturday night, in a black cinema in 1972. . . . [At a climactic scene of violence] the massive theatre full of black males cheered in a way the nine-year-old little me had never experienced in a movie theatre before. At the time–living with a single mother–it was probably the most masculine experience I’d ever been a part of.

At the end of the book he pays homage to another Black movie mentor, Floyd Ray Wilson. Living with Tarantino and his mother, Floyd dated the mother’s friend and became Tarantino’s teenage tutor on rock and roll and Blaxploitation. Floyd taught Tarantino the virtues of Willie Best, Stepin Fetchit, and Don Knotts. Floyd also wanted to be a screenwriter, and he inspired Tarantino to try his hand too. Django Unchained, our author says, springs from his tenuous friendship with Floyd, who wrote a Black western.

Knowing full well how a range of readers will respond to these accounts of interracial male bonding, with his usual insouciace Tarantino plows on through a series of critical essays on films that shaped his tastes, all rendered in a pitch of high enthusiasm.

Old School enthusiam

You can argue that the most epic display of the criticism of enthusiasm appeared in the spring 1963 Film Culture magazine. There Andrew Sarris published a roster of Hollywood directors under the rubric “The American Cinema.” Each director was given a filmography and critical commentary. Most important, they were grouped into snappy categories: Pantheon Directors, Third Line, Esoterica, Beyond the Fringe, and so on. In 1968, Sarris published the material as a book, expanded by a long prefatory essay, considering more filmmakers, and using other labels. “Esoterica” became “Expressive Esoterica,” for example, and “Third Line” became “The Far Side of Paradise.” Some directors were also re-sorted; Anthony Mann moved up from Esoterica to the Far Side. The category “Fallen Idols,” which included many of the most revered directors (Wyler, Huston, Kazan, Lean, Wilder, Zinneman), was now the snarkier “Less Than Meets the Eye.”

You can argue that the most epic display of the criticism of enthusiasm appeared in the spring 1963 Film Culture magazine. There Andrew Sarris published a roster of Hollywood directors under the rubric “The American Cinema.” Each director was given a filmography and critical commentary. Most important, they were grouped into snappy categories: Pantheon Directors, Third Line, Esoterica, Beyond the Fringe, and so on. In 1968, Sarris published the material as a book, expanded by a long prefatory essay, considering more filmmakers, and using other labels. “Esoterica” became “Expressive Esoterica,” for example, and “Third Line” became “The Far Side of Paradise.” Some directors were also re-sorted; Anthony Mann moved up from Esoterica to the Far Side. The category “Fallen Idols,” which included many of the most revered directors (Wyler, Huston, Kazan, Lean, Wilder, Zinneman), was now the snarkier “Less Than Meets the Eye.”

The 1963 original and the 1968 book created a revolution in film taste. Sarris had been polemicizing in favor of “the auteur theory” for some time, but with his encyclopedic survey he created a canon. He claimed that he wanted only to launch a systematic history of American cinema, but the result was hardly historical in a strong sense. What mattered was critical evaluation. Writing a history of Hollywood would amount to appraising its directors.

Directors hadn’t wholly been ignored by earlier writers. Griffith, Chaplin, Lubitsch, Flaherty, Stroheim, and Welles had been considered significant creative forces for some time. What Sarris sought to do was to map out the whole terrain of Hollywood to reveal a network of strong creators with distinctive “directorial personalities.” They were not merely craftsmen; they had artistic visions.

Sarris’s strategy was triumphantly successful. He included in his Pantheon not only the noteworthy figures I just mentioned but those revered by the Cahers du cinéma critics: Ford, Hawks, Hitchcock, Keaton, Lang, Ophuls, Murnau, Renoir, and von Sternberg. At least as important were his arguments in favor of second-tier figures like Aldrich, Borzage, Cukor, Minnelli, McCarey, Sturges, and Walsh. And so on down the line as he weighed the virtues of Gerd Oswald, Richard Quine, and dozens of others.

Sarris’s legacy remains. To this day books and articles continue to be devoted to the works of these directors, famous and lesser-known. They are staples of Hollywood history. At the same time, researchers have expanded Sarris’s purview by elevating some of his choices (e.g., Curtiz) and discovering major films by minor figures (e.g., Ulmer). Martin Scorsese’s Personal Journey through American Movies (1996) is very much in the Sarris spirit, offering some different categories but still committed to the auteurist canon.

Film scholars today may question the tenets of the auteur theory, preferring to find involuntary cultural pressures in classic works, but to a surprising extent the big names remain central. And researchers discovering unexpected value in forgotten figures like Hugo Fregonese (subject of a retrospective at Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato this year) are fulfilling Sarris’s edict that every film and filmmaker deserve serious scrutiny. (One critic has suggested that Fregonese would fit comfortably into Expressive Esoterica.)

Film scholars today may question the tenets of the auteur theory, preferring to find involuntary cultural pressures in classic works, but to a surprising extent the big names remain central. And researchers discovering unexpected value in forgotten figures like Hugo Fregonese (subject of a retrospective at Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato this year) are fulfilling Sarris’s edict that every film and filmmaker deserve serious scrutiny. (One critic has suggested that Fregonese would fit comfortably into Expressive Esoterica.)

The book version of The American Cinema: Directors and Directions popularized Sarris’ aesthetic of classic Hollywood. Just as important, it was a tribute to enthusiasm-fueled cinephilia. Sarris might talk about research, but this was mostly about enjoyment, seeking out little-noticed pleasures in a vast flowering landscape. “If you received The American Cinema at the right moment in your life,” notes Kent Jones, “and many people including myself did, it came with the force of a divination, a cinematic Great Awakening.”

But films continue to be made, and how are we to appraise them? Some directors in Sarris’s survey continued their careers into the 1970s and beyond, but others emerged. Many of those became labeled the “New Hollywood.” From this perspective, Tarantino’s Cinema Speculation proposes a counter-canon, a cluster of filmmakers and films that demand to be appraised on terms that differ somewhat from those laid down by Sarris. Yes, they are solid artisans. Yes, they have “personal visions.” But their auteur artistry has its own commitments.

Sources of enthusiasm

Bullitt.

Central to those commitments is the idea of genre. In one of the richest essays in the book, Tarantino suggests that what follows Sarris’s period survey is a new Hollywood, which has two phases. In the first, Penn, Altman, and other filmmakers commit to criticize classic genres, pointing out their political and racial biases. The second phase consists of directors like Spielberg, Lucas, and De Palma who love genres and want to update and strengthen them, or to invent new ones, like the “Revengeamatic.” Tarantino appreciates both trends, but his sympathy lies with the second one. He praises some older genre directors like Don Siegel and is especially sensitive to New Hollywood filmmakers who either worked to update genres (Tobe Hooper) or balanced indulgence in the genre with some critique of it (Taxi Driver, Hardcore).

Tarantino’s favored 1970s genres are centered on violence: crime stories, westerns, urban adventures. In this, he follows audience tastes. Most people aren’t auteurists, least of all Tarantino’s 70s male mentors. He also focuses his attention on scripts, often providing backstory on how some of his favorites were revised in the production process.

More specifically, he’s interested in character and dialogue–again, mirroring what most moviegoers notice and enjoy. He analyzes character action and sometimes interprets it as reflecting public attitudes or the director’s temperament. He savors memorable lines of dialogue and reenacts the joy of audiences responding to them. In Taxi Driver:

Then the moment happened that made the whole theatre burst into hysterics. That one guy walking down the street, ranting and raving that he’s going to kill his woman (“I’ll kill ‘er! I’ll kill that bitch!”). We laughed so hard at that guy, we were a little disconnected from the movie for the next twenty minutes.

Travis Bickle’s Mohawk haircut triggers the same response. “The whole theatre burst out laughing. I’m talking hysterically laughing. I’m talking rolling in the aisles laughing–Get a load of that goddamn crazy fool!”

The concern for characters emerges further in Tarantino’s unabashed admiration for acting. Sarris’ American Cinema treated stars as plastic material for the director’s vision. For John Ford, John Wayne develops as a darkening version of western heroism. James Stewart is radically different in films by Capra, Preminger, and Anthony Mann. But Tarantino treats stars as bringing their own valences, which the director can fulfill more or less well. Steve McQueen is the privileged example.

The man embodies 1960s cool, and the films that respect that become singularly satisfying. Bullitt becomes a perfect vehicle for this paradigm of hip detachment.

This is the role he deserves to be remembered by. Because in this role he demonstrates what he could do that Newman and Beatty couldn’t.

Which is just be.

Just fill the frame with him.

There was craft at work here. Tarantino reveals that McQueen often trimmed his own dialogue, giving lines to others, because he knew the audience would be watching him. He could steal a scene with his pinky finger, as I tried to show here. But in Bullitt, he does so little that we watch him warily.

Tarantino doesn’t bother with description of how this minimalism works facially–the fixed blue-eyed stare, the enigmatic pinched lips, the flat brows. He goes straight to psychology: Bullitt doesn’t engage with anyone, so his mental states are opaque to us. His girlfriend admonishes him for his refusal to open up about his feelings. “Bullitt,” Tarantino says, “doesn’t explain to the audience or other characters what he’s doing or thinking. He just does them and we watch.” Here cool turns cold.

With performance as a central concern, Tarantino naturally reflects a lot on casting and performance. His vast knowledge of the genre and Hollywood actors, from stars to sidekicks, allows him to probe the actor’s development of the character, as he does with Burt Reynolds in Deliverance and Sylvester Stallone in Paradise Alley. He often speculates on what the film would be like if this role were filled by someone else. What if Lee Marvin replaced Burt Reynolds in Deliverance? What if The Getaway was recast making Stella Stevens McQueen’s wife, Richard Boone his major adversary, and Stuart Whitman the master mind? These “cinema speculations” are sometimes derived from actual casting choices, sometimes from Tarantino’s huge knowledge of Hollywood players.

Add in music, to which Tarantino is very sensitive, and you have an aesthetic tailored to audience pickup. He has almost no specific comments about imagery or camera technique, the sorts of things that audiences tend not to comment on. Above all, you know when you have a memorable movie moment if a line or character reaction or actions scene induces the audience to shriek in pleasure. From age 4, he claims, for him the thrill of cinema has been bound up with a crowd response. (I found this reassuring, as Perplexing Plots begins with an audience’s reaction to the climax of Pulp Fiction.)

Genre, character portrayal, memorable dialogue, performance filigree, the charisma of stars, and the immediate surge of audience appreciation–who else does this sound like? Pauline Kael.

Tarantino has called her the most influential person on his filmmaking; he pored over her collected reviews and channeled her voice. If Sarris was the impresario of classical studio production, Kael became the demanding guide to the New Hollywood. As Tarantino was absorbing the films, growing up with the flood of 70s features, he was tuning himself to the body of work that inspired her lyrical and indignant reviews. Sarris, who reviewed films for the Village Voice at the period, was always seeing the present in the terms of the past, but Kael’s New Yorker readers were happy for her electrifying assurance that some filmmakers were living in the moment. (Always the contrarian, she insisted that her readers inclined toward art films and ignored her recommendations about Hollywood’s output.) When she loved a film, her review was an orgy of enthusiasm–most notoriously, her piece on Last Tango in Paris (1972).

The only time I saw Kael in person, in fall of 1965, she shared a panel with Sarris at my college. Armed with a cigarette holder, she glittered by comparison with the rumpled, insomniac-looking man alongside her. He wanted to talk about Ophuls’ Lola Montès. She wanted to talk about The Cincinnati Kid and especially about its star, Steve McQueen. I usually resist symbolism, but it’s hard not to see this as part of a big change in tastes.

A fan’s notes

The Outfit (1973).

To get a sense of the strength of Tarantino’s criticism, consider his treatment of two genre masters. One is an old-timer who started in the 40s and had a vigorous career into the 1970s. The other is presented as a largely unappreciated director who helmed some of Tarantino’s favorites. Both illustrate the power of Tarantino’s enthusiasm and wide-ranging knowledge.

Across the 1950s and 1960s, Don Siegel developed a reputation for taut and violent action pictures, notably Riot in Cell Block 11, Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Baby Face Nelson, The Line-Up, The Killers, and Madigan. Sarris ranked Siegel with Budd Boetticher, Alan Dwan, Phil Karlson, and Joseph H. Lewis as “Expressive Esoterica.” But after Madigan (1968), starring Richard Widmark, Siegel became something of an A-list director. His status was reinforced by an alliance with Clint Eastwood for Coogan’s Bluff (1968), Two Mules for Sister Sara (1969), Dirty Harry (1971), and Escape from Alcatraz (1979). He worked with other top stars like Walter Matthau (Charley Varrick, 1973), John Wayne (The Shootist, 1976), and Charles Bronson (Telefon, 1977). For a time he had box-office success alongside the New Hollywood prodigies.

Tarantino pays lengthy homage to Siegel throughout Cinema Speculation. He sees him as a virtuoso not simply of action cinema but of screen violence, a pioneer of what would emerge in impact-based films of the 1970s like The French Connection and Straw Dogs. (The editing of Madigan‘s final shootout still looks daring today.) Tarantino declares that the rogue law-enforcement officer who pursues his “own self-determined version of justice. . . is practically the quintessential Siegel protagonist.” This quality sets the hero apart from his family, his peers, and society at large. Hence not only the bursts of brutality but also the curious lack of sympathy his cold, aloof men engender.

Tarantino celebrates several Siegel films but he focuses on Dirty Harry as a prototype and the director’s best. He traces the mutations of the script as the project moved from Universal to Warners, with John Milius adding the famous “I know what you’re thinking” line. In execution, the use of location shooting and many “movie moments” (Harry chewing his hot dog while firing at his prey, Harry’s foot pinning down the screaming Scorpio on a football field) show a master at work. Siegel excels in chase sequences, and Dirty Harry has plenty. Above all, the film aroused audiences. They were shocked by the violence and thrilled by “crowd-pleasing action set pieces.”

Tarantino answers criticisms of the film with some care. Dirty Harry isn’t, he claims a fascist film because it was responding to genuine anxieties of its audience. The film was tailored for older Americans unable to adjust to youth culture, civil rights, drugs, and other signs of apparent decay. Harry mostly doesn’t exceed reasonable behavior for an officer bent on justice. The exception is Harry’s torture of Scorpio; but that’s when the kidnapped girl might still be alive and the clock is ticking. Tarantino asks: “Would Billy Jack do any less?” Or, we might add, would Jack Bauer of 24?

More positively, Dirty Harry is the first significant serial-killer film, and it asks for a reconsideration of policing practices that are becoming outmoded after the Manson family and Zodiac. Scorpio is a new kind of villain who will flout the constraints of civil society. He seemed implausibly evil in 1971, but we hadn’t yet accustomed ourselves to the monstrous depravity of the obsessed killers out there. The film is a plea for “New Laws for New Crimes.”

Still, Tarantino calls the film “aggressively reactionary” in its reassurance that the audience’s fear of change is justified. He points out that the bank robbery has to be conducted by Blacks to fulfill its function of scaring the audience with the spectre of Black Power. Is it then a racist film? Siegel called Harry “a racist son of a bitch.” Tarantino modifies his case by calling Harry “both a troubled and a troubling character.” He doesn’t elaborate, but concludes that the ambivalence of the plot and its protagonist is overridden, Tarantino says, by the sheer professionalism of Siegel’s filmmaking. Today’s audiences, far from fascist or racist in their sensibilities, continue to enjoy the movie. As ever, the visceral response in the theatre is Tarantino’s touchstone.

John Flynn doesn’t feature in Sarris’s compendium, since his career directing features began in 1968. Mentored by Robert Wise, he had been assistant director on comedies and The Great Escape (1963) before his first feature, the repressed-gay drama The Sergeant (1968). His most famous film is the cult favorite Rolling Thunder (1977), a bloody revenge saga that makes highly inadvisable use of a kitchen garbage disposal. Seeing it at age 14, Tarantino reports that it “blew my fucking mind.” He followed its screenings across Los Angeles, and the book lovingly details all the venues he visited.

Over the years Rolling Thunder taught him that a film can criticize its own genre. He offers a comparative anatomy of the original script by Paul Schrader and the thorough rewrite by Heywood Gould. He finds that Gould’s screenplay improves the original, not least in an exchange between the two buddy heroes.

RANE: I’ve found the men who killed my son.

JOHNNY: I’ll just get my gear.

“That scene and those lines never fail to drive audiences wild wherever and whenever it’s projected. And trust me, I’ve seem Rolling Thunder with every type of audience imaginable.”

John Flynn’s other major work is The Outfit (1973), a story of a professional thief, Macklin, who avenges the murder of his brother by a series of assaults on businesses run by the syndicate. Ultimately the two launch an attack on the fortified mansion of the big boss. Tarantino praises the playing of Robert Duvall and especially Joe Don Baker’s swaggering performance as Cody, his wisecracking sidekick. “The hearty macho audience scattered around the little cinema made it even more fun. They laughed at everything Joe Don Baker said.”

It’s striking that Tarantino doesn’t mention the radical changes that Flynn, acting as screenwriter with assistance of Walter Hill, made to the original book. The Outfit (1963) is third in a long-running series of novels by Richard Stark (Donald E. Westlake) centering on the professional thief Parker. Tarantino professes himself a fan of the character, though he admits to not having read most of the books. In the novel, Parker is aiming to force the Outfit to pay the money it owes him from a double-cross. His strategy is to encourage several other thieves to hit Outfit enterprises on their own. The second half of the book is taken up with those robberies, each with a new gang targeting a business in different cities: a casino, a numbers operation, a heroin-smuggling enterprise, and a racetrack bookie scheme.

Parker drops out of these chapters, and Stark treats us to semidocumentary analyses of how each racket works. It’s a bold and fascinating approach, but the film avoids it, simply assigning some of the raids to Macklin and Cody. The result is a buddy movie. True, in the book Parker picks up a sidekick, Handy McKay, but their relationship is purely professional. Parker is a forbiddingly cold character, and no one can imagine him chortling, as Macklin does, at Cody’s final quip, “The good guys always win.”

Why did Tarantino ignore the book’s original plot structure? In Perplexing Plots, I devote a chapter to Westlake’s Stark novels because of their unique play with time. Every Parker novel but one is divided into four parts, and scenes are time-shifted within and between parts. Typically, one part leaves Parker’s viewpoint and whisks us from character to character within a fluid nonlinear chronology. In The Outfit, that section is the one tracing the gang’s guerrilla attacks on the syndicate, those in turn framed by the syndicate boss learning of them.

Most Stark adaptations drastically linearize the original plots. The most salient exception is Point Blank (1967), which pulverizes the action of The Hunter (1962) far more than Stark does. (Tarantino mostly scoffs at Boorman’s film, and I’m inclined to agree.) You’d think that Tarantino would notice how Flynn made the novel a more standard outlaw picture, whatever benefits it yielded.

The puzzle persists. Perplexing Plots has a chapter on Tarantino too, where I suggest that Stark’s structure has a deep affinity to the back-and-forth time schemes in Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction. This notion stems from from Tarantino’s claim that The Hunter and other Stark novels “were very influential on” Reservoir Dogs. Perhaps Cinema Speculation‘s ignoring of the structural changes in Flynn’s version of The Outfit better captures Tarantino’s youthful response, in which masculine bonding and high-intensity violence play the central part. (He saw it at age 11, well before he read any Stark novels.) In any case, I hope my argument for his films’ affinity for the looped patterning of the Parker books seems plausible.

Tarantino’s focus on the 1970s shouldn’t make us forget his connoisseurship in other realms, such as Hong Kong cinema and the spaghetti Western. Still, he’s a model of the post-Kael downmarket cinephile, rummaging through every quickie release and even TV movies to find moments of arousing filmmaking in “the greatest movie-making era in the history of Hollywood.” Accordingly, he betrays little interest in Hollywood classicism; he can’t imagine working in the old studio system, in which a director might have to shoot a script he doesn’t like. Moreover, I think he finds the elegance of classical film too fastidious compared to the rough antics on display in his favorites.

My own tastes overlap his, though I doubt I’ll ever admire some of his prize filmmakers as much as he does. I’m principally a Sarrisite, insofar as my top Hollywood filmmakers coincide with his, though I find more to admire in Wyler and others than he does. And we all live on our own timelines. While that kid Tarantino was being transported by exploitation pics in the 1970s, I was stunned by the revelations of classic Japanese films by Ozu, Mizoguchi, and others. I think highly of Jaws (1975), but it’s not sublime in the manner of Early Summer (1951) or Sansho the Bailiff (1954).

No news: Tastes differ. Critics owe it to us to whip up enthusiasm for the films that give them goosebumps of rapture. But they also owe us reasoned arguments for how and why that happens. Cinema Speculation is, for me, at its best when Tarantino supports his appraisals with analysis. But even when he doesn’t, it’s still a fucking blast.

Thanks to Jim Healy for assistance in preparing this entry.

Other film criticism by Tarantino can be found on the Beverly Cinema site, as well as in his many interviews. He traces his devotion to Pauline Kael at length in Lynn Herschberg’s podcast.

The Sarris/Kael split isn’t as drastic as I’m making it. Kael loved classic Hollywood too, especially in its frothier moments and in films that featured strong heroines. But she was generally opposed to treating the directors as having unified artistic visions; they seldom achieved much beyond engaging kitsch. She wanted to preserve the immediacy of contemporary cinema for current life and for its public. Sarris in turn was always ready to celebrate studio actors of the Golden Age, and he was eager to interpret current releases in light of politics–as was Kael, with her complicated but fervent feminism.

Kael’s use of audience response as a touchstone surfaces throughout her reviews. She tells of audience applause in Gance’s Napoléon, hisses and walkouts in a Mel Brooks screening, viewers’ empathy for Teri Garr in Tootsie, and the roars of laughter greeting 48 Hrs. (All these are in Taking It All In [Holt, Rinehart, Winston, 1983], pp. 144, 216, 432, and 440.) I wondered about these real-time reports, because she saw most films she reviewed in pre-release press screenings. Often, she says, she saw the film on Monday and turned in the New Yorker review the next day. She discusses her reliance on press screenings in George Malko’s 1972 profile, “Pauline Kael Wants People to Go to the Movies,” in Conversations with Pauline Kael, ed. Will Brantley (University of Mississippi Press, 1996), 15-30.

Stephanie Zacharek, film critic for Time, tells me that Kael often attended screenings with paying audiences, sometimes before filing her pieces, if the New Yorker‘s deadlines were flexible enough. “In addition, during the 1980s, she was often shut out of screenings by studios that didn’t want her to see their movies. In those cases, she would go to an early public showing.” Thanks to Stephanie for this background.

Tarantino’s other major literary effort, his quasi-novelization of Once Upon a Time . . . in Hollywood, is considered in this entry. It has fascinating resonance with many ideas in Cinema Speculation.

Rolling Thunder (1977).

PERPLEXING PLOTS now available!

Gone Girl (2014).

DB here:

Like a movie rolling out on a platform release, Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder, has several “publication dates.” The official pub date is 17 January of next year, and that’s when I expected to see it. Now Amazon lists a shipping date of 1 December. But I just got my author’s copies, and I learn that the book can be bought from Columbia University Press now–at a 20% discount! (As of this writing, Amazon offers no discount.) If you’re interested, go here. To get the discount, enter CUP20 in the promo code box.

As I indicated in an earlier entry, the book is an attempt to trace how mainstream audiences learned to understand and enjoy stories that play with linearity and viewpoint–what we now call the “New Narrative Complexity.” Except that it’s not so new. If we look at fiction, theatre, and film (even a little radio) from the nineteenth century to the present, and are willing to go beyond the canon in search of oddball experiments, we find that many of the subterfuges we associate with narrative innovation today were attempted earlier–sometimes achieving great popularity.

As I indicated in an earlier entry, the book is an attempt to trace how mainstream audiences learned to understand and enjoy stories that play with linearity and viewpoint–what we now call the “New Narrative Complexity.” Except that it’s not so new. If we look at fiction, theatre, and film (even a little radio) from the nineteenth century to the present, and are willing to go beyond the canon in search of oddball experiments, we find that many of the subterfuges we associate with narrative innovation today were attempted earlier–sometimes achieving great popularity.

I go on to argue that an important training ground for narrative gamesmanship was the realm of mystery, especially detective stories and suspense thrillers. I trace important developments in this domain and then analyze several of my favorite mystery-mongers, from Rex Stout and Donald Westlake to Patricia Highsmith and Laura Lippman. Yes, Griffith, Hitchcock, Tarantino, and other filmmakers are involved too.

I hope to devote some future blogs to filling out gaps in the book, such as discussing G. K. Chesterton’s Father Brown stories, considering Nero Wolfe’s relation to the FBI, and examining a now-nearly-forgotten mystery series that in its day sold millions of copies. And, given how Knives Out chimes with PP, I expect to have something to say about Glass Onion. In the meantime, you can check the Table of Contents and read early reactions from readers on the CUP website. Encouragingly, the book is now number 1 in Amazon’s list of new books on mysteries.

Thanks to the readers who have already expressed interest in the book!

The Great Piggy Bank Mystery (1946).

A Monument to Mystery: Martin Edwards’ THE LIFE OF CRIME

DB here:

In my early teens I bought murder mysteries from the legendary Claude Held of Buffalo. Lacking a checking account, I blithely sent through the mail dollar bills and even coins taped to the order. I still have S. S. Van Dine and Ellery Queen hardbacks from those days, but my most treasured item is a first edition of Howard Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story (Appleton-Century, 1941).

Published on the hundredth anniversary of Poe’s “Murders in the Rue Morgue,” Haycraft’s survey of mystery fiction sought to establish the legitimacy of the genre. It became the authoritative source on the subject, and it’s still worth reading. Even then I had the habit of writing notes in the margins, and I’m ashamed of the jejeune scrawls that dare to call Haycraft to account. (“This is quite incorrect.”) Still, Haycraft confirmed my love of the subject and showed me what a serious literary history might look like. (Once more the adolescent window.)

Thirty years later came another powerful overview of the genre’s history. Julian Symons’ Bloody Murder aka Mortal Consequences (Harper & Row, 1972) was a revision and partial rejection of the standard story. Haycraft was a critic, but Symons, who reviewed mystery fiction, was also an accomplished novelist. The book is often harsh in its critical judgments, as when Symons downgrades Sayers as “pompous and boring” and classifies many of her peers as Humdrums. Symons promoted instead what he considered the strongest contemporary trend, the shift from puzzles to character-driven and socially critical writing. His subtitle sums up his argument: “From the Detective Story to the Crime Novel.”

Now, fifty years after Bloody Murder, comes our most comprehensive and nuanced account of the entire genre’s development.

Now, fifty years after Bloody Murder, comes our most comprehensive and nuanced account of the entire genre’s development.

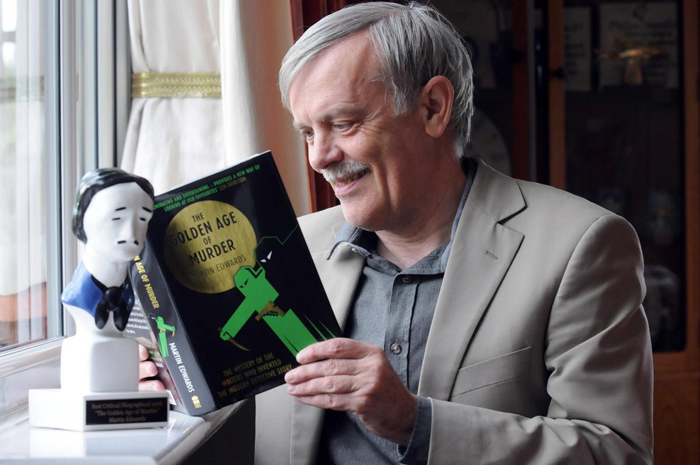

Martin Edwards’ Wikipedia entry makes your head swim: the man is a true polymath. Trained in the law and still a consulting solicitor, he’s a prolific, highly lauded mystery novelist as well. He has won virtually every literary prize in the field, not least the Diamond Dagger, the British Crime Writer’s Association highest award. His most recent novel, published on 1 September, is The Blackstone Fell.

Edwards is also recognized as the premiere historian of the genre in English, thanks to his many books, including The Golden Age of Murder (2016) and The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books (2017). As if all this didn’t keep him busy enough, he writes a lively blog, “Do You Write Under Your Own Name? And he’s incapable of composing a graceless sentence.

So it’s no surprise that The Life of Crime: Detecting the History of Mysteries and Their Creators is a monumental achievement. At 724 pages, resplendent with a burgandy string bookmark and beautiful colored end papers, it’s a triumph of modern publishing, and a stupendous bargain. (It’s currently going for $26.39 from the publisher.) The hardcover is currently ranked as #1 in Amazon’s Mystery and Detective Literary Criticism (with the audible book as #2).

The bulk and detail of The Life of Crime will incline many to treat it as a reference book. It functions superbly as that, thanks to a careful index, but it is even more. It provides a nuanced, reliable history of the genre; it offers rich insights into storytelling technique; and it teems with unforgettable stories of mystery authors. As the subtitle promises, it’s an account of both books and the people who create them.

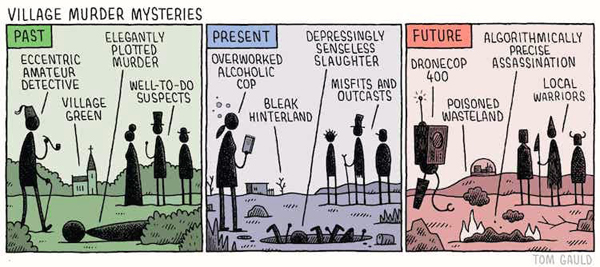

Crime waves

By Tom Gauld.

At the end of the 1930s, Haycraft’s Murder for Pleasure could confidently sum up the standard trajectory. The detective story developed from Poe to Gaboriau to Conan Doyle, and then to the Golden Age of Christie, Sayers, Carr, Van Dine, Queen, and many others. Haycraft acknowledges the accomplishments of the 1920s British school, their US counterparts, and the emerging hardboiled trend typified by Dashiell Hammett. (Chandler was still a secondary figure when Haycraft was writing.)

Following the most self-conscious writers of the 1930s, Haycraft recognizes the need for the mystery to move closer to prestige fiction. He suggests it do so through a greater emphasis on characterization and on social commentary: the “novel of character” and the “novel of manners.” He sees the hardboiled trend as a variant of the novel of manners and warns that in its pure form it will soon wane. It “is beginning to become just a little tedious from too much repetition of its rather limited themes.”

Time would prove him wrong. The 1940s saw new variations in the hardboiled school, most evident in the spectacular popularity of Mickey Spillane. In Bloody Murder Symons faulted Haycraft’s analysis on other grounds. He failed to discern the growing power of the “crime story” as distinct from the detective tale. Thanks largely to Hammett, violence, eroticism, abnormal psychology, and official corruption moved to the center of writers’ concerns.

For Symons the apparatus of footprints, altered wills, and bodies in the library was surpassed by the rise of suspense fiction and the police procedural. Patricia Highsmith, Symons declared, is “the most important crime novelist at present in practice.” She, along with Margaret Millar, John Bingham, and Symons himself (!) typified the potential of the modern crime story, with Ross Macdonald revising the classic detective plot through the concern for “personal identity and the investigation of the past.”

Edwards holds Symons in high regard but has a more pluralistic conception of the genre’s history. The Life of Crime reaches back to the eighteenth century (William Godwin’s Caleb Williams) and ends with surveys of Nordic noir, East Asian detection, the contributions of contemporary women and minority writers, and the fashion for historical mysteries. The 55 chapters are organized around periods, trends, and exemplary figures. They survey not only crime literature, but plays, films, and television shows.

The broad picture Edwards paints shows how changes in the genre coincide with broader social dynamics. He’s especially good on the impact of World War I on an entire generation of writers and readers. Likewise, he traces how World War II spurred the rise of psychological thrillers in fiction and film, as well as the new platform of paperback originals.

Edwards’ comparative approach shows that the clash of Golden Age and hardboiled tendencies isn’t as drastic as Symons suggested. Symons saw Hammett and Chandler as in rebellion against the “rules” of the classic whodunit. Edwards shows that the hardboiled writers respected not only many Golden Age authors but also many of their conventions. For Edwards, the mystery tradition offers writers a range of creative choices not limited to a single notion of form or style.

An unabashed fan of Christie, Sayers, and their peers, Edwards is especially good at tracing the continuing influence of the Golden Age on contemporary work around the world. Who would have predicted the obsession of contemporary Japanese novelists with impossible crimes and narrative tricks, stemming from the canonical Edogawa Ranpo’s love of classic artifice? Popular examples are Shimada Soji’s Tokyo Zodiac Murders (1981) and Higashino Keigo’s The Devotion of Suspect X (2006). Edwards introduced me to a remarkable “book” by Awasaka Tsumao, The Living and the Dead, which, thanks to the Golden Age trick of sealed pages, contains a short story that disappears as you read the novel. The author, not coincidentally, is a magician.

One of the most striking assets of the book is the endnotes at the end of each chapter. Far from academic citations, these notes are often wide-roaming discussions of topics mentioned in the text. So, for instance, R. Austin Freeman’s worry that fingerprints could be fabricated gets this elaboration in an endnote:

Fingerprinting was used by Scotland Yard from 1901, but Sherlock Holmes examined for a thumbprint eleven years earlier, in The Sign of Four. In the US, fingerprint identification was central to the plot of Pudd’nhead Wilson, by Mark Twain (Samuel Langhorne Clemens). But Freeman feared that reliance on uncorroborated fingerprint evidence could lead to miscarriages of justice. Hammett’s story “Slippery Fingers” reflects a similar concern, and some experts share it to this day (113, n8).

The dozens of reader-friendly endnotes offer a wealth of supplementary information, including recommendations for further reading. Any chapter’s supplements could provide scholars a host of leads for further research. These notes typify the generosity of the book, whose vastness conveys not pedantry but an eagerness to share information and excite the reader’s curiosity.

Edwards’ pluralism amounts to more than intellectual generosity. His book’s global sweep illustrates the astonishing fecundity of the genre in varying cultural contexts; it also shows how malleable its conventions are. I think he shows how fertile a tradition of popular storytelling can be–especially when it has the power to cross boundaries of time, place, and language. No reader of The Life of Crime can believe that this genre has run out of steam.

The toolbox

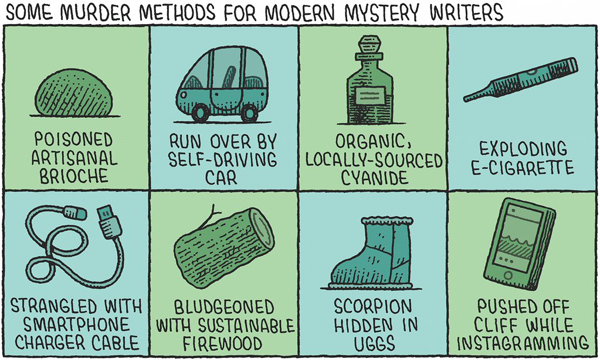

Tom Gauld, The Guardian (9 January 2016).

Most authors surveying the history of mystery discuss the narrative techniques employed by the various schools. Unlike most genres, mystery fiction’s identity depends on duplicitous manipulations of time, viewpoint, and narration. To conceal the crime and its perpetrator, the author must carefully select who knows what and when. The goal is to baffle both the investigators and the reader, with not only clues on the scene but also hints in the manner of telling. Needless to say, those clues and hints may be misleading.

Both Haycraft and Symons dutifully invoked the conventions of Golden Age bafflement. Haycraft treated them as the source of the genre’s distinctive pleasures, while Symons sometimes deplored their reliance on implausibility and coincidence. (He wasn’t, however, as demanding as Chandler, who famously remarked that “Fiction in any form has always intended to be realistic.”) As a writer sympathetic to Golden Age artifice, Edwards is eager to explore the whole range of devices available for mystery plotting. At this level, The Life of Crime is an encyclopedia of creative options available to the genre. Not surprisingly, Edwards’ wide compass shows that many “modern” techniques have distant historical precedents.

Aficionados recognize several ploys: false identity, faked death, slippery alibis, dying messages, equivocal clues, the absent clue (the dog that doesn’t bark in the night-time), the double bluff (X seems to have done it; wait, X is too obvious a suspect; nope, X actually did do it). Edwards goes beyond these to track how storytellers have used multiple narrators to cloud the situation and sharpen characterization. He shows the persisting power of the “inverted story,” the structure that shows the criminal committing the crime and then follows the detective’s exposure of guilt (the Columbo strategy). He devises a new term to accompany the “whodunnit” and the “howdunnit”: the whowasdunin, the plot that withholds the identity of the victim until the climax. This is a wider trend than I had realized. The same goes for the inclusion of letters and diaries in the text, which feels modern to us but actually goes back centuries.

And of course he doesn’t neglect reverse chronology, highlighted in one of those endnotes that can keep you busy for weeks:

This method of storytelling can dazzle, but only if the writers’ craftsmanship matches their courage. The possibilities are shown by Iain Pears’ novel Stone’s Fall, Jeffery Deaver’s The October List and Ragnar Jönasson’s Hulda Trilogy as well as by Simon Brett’s play Silhouette, Christopher Nolan’s film Memento, Harry and Jack Williams’ TV series Rellik, and Steve Pemberton and Reece Shearsmith’s “Once Removed,” a witty and brilliantly economical episode of Inside No. 9 (612n19).

In all, Edwards’ sensitivity to innovations allows his book to be a stimulating source of craft practices to anyone who wants to write a mystery.

Mystery and misery

Walt Kelly, “The Big Comical Book Business” (Pogo Possum no. 5, 1951).

Sara Paretsky took up crime writing after contemplating poisoning her husband. Composer George Antheil, outraged by the attacks on his Ballet mécanique, wrote a novel in which barely disguised music critics were extravagantly murdered. Mary Roberts Rinehart refused to make one of her servants her butler, and he retaliated by trying to shoot and stab her. Patricia Highsmith smuggled her pet snails into England by hiding them in her bra, “six to ten per breast.”

At least as intriguing as the crimes in their books are the personal histories of the authors. Edward starts most chapters of The Life of Crime with an arresting account of one writer’s life. It’s often a catalogue of miseries. Alcohol damaged Poe, Hammett, Chandler, Highsmith, Craig Rice, Cornell Woolrich, and innumerable others. Drugs figured in the careers of Wilkie Collins (laudanum) and S. S. Van Dine (morphine). Suicide attempts and mental illness were distressingly common as well.

These usual artworld excesses are enhanced by mystery-mongers’ distinctive dose of weirdness. After a devastating traffic accident, Patrick Hamilton, author of Rope and Gas Light, became obsessed with his brother Bruce. He refused to speak to Bruce’s wife and declared it was a pity that he, Patrick, wasn’t a woman; then he could have married Bruce. Bruce, a mystery writer himself, published a novel called A Case for Cain, in which one brother beats another to death with a golf club.

The juxtaposition of suffering and creative energy is marked. On the brink of financial ruin, morphine-addicted Willard Huntington Wright persuaded a distinguished publisher to issue three mystery novels under the pen name S. S. Van Dine. They sold in the millions and led to a long-running series. Rupert Croft-Cooke, after serving a prison term for homosexuality, fled England for Tangier and published dozens of detective novels under the name Leo Bruce. He also wrote twenty-seven volumes of autobiography called The Sensual World. Agatha Christie’s disappearance in 1926, probably due to temporary amnesia, was a response to her mother’s death and her husband’s infidelity. It didn’t hamper her immense productivity.

With his novelist’s eye, Edwards sympathizes with his subjects, but just reporting the facts still leaves you reeling. Of William Lindsay Gresham he records excessive drinking, occasional violence, and suicide attempts. When Nightmare Alley was bought for Hollywood, Gresham moved into a mansion. “He dabbled in folk-singing, and tried to ease his misery by exploring Dianetics, the precursor of Scientology, and taking an assortment of lovers. On one occasion he’d tried to hang himself on a hook, but it broke.” Years later, he killed himself with sleeping pills. “Legend has it that his pockets were stuffed with business cards bearing the inscription: No Address. No Phone. No Business. No Money. Retired.”

Edwards avoids sensationalism, but it’s good to remind us that much of the entertainment we enjoy was built on a lot of personal pain.

The Life of Crime is, then, a book in four dimensions: reference volume, historical survey, armory of literary techniques, and biographical accounts of major artists. To succeed with any one of these is remarkable; to succeed with all of them is something of a miracle. It will remain an indispensable guide to its subject.

Full, if belated disclosure: I read Martin’s book in manuscript and offered some comments, for which he kindly thanks me. He has also provided an endorsement of my forthcoming Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder.

The Life of Crime is already getting splendid reviews in the press and on the Net. There’s an illuminating interview with Edwards on the American Scholar podcast.

You’ll find plenty of funny cartoons on writing, including writing mysteries, from Tom Gauld here and here.

Martin Edwards. From the Warrington Guardian.

Enter Benoît Blanc: KNIVES OUT as murder mystery

Knives Out (2019).

DB here:

Now that a sequel, Glass Onion, has been announced for the Toronto International Film Festival, it seems a good time to look back at Rian Johnson’s first whodunit Knives Out. The effort has a special appeal for me because it chimes well with arguments I make in Perplexing Plots: Popular Storytelling and the Poetics of Murder.

I don’t analyze Knives Out in the book, but it would have fitted in nicely. The movie exemplifies one of the major traditions I study, the classic Golden Age puzzle, and it shows how the conventions of that can be shrewdly adapted to film and to the tastes of modern viewers. In addition, Johnson’s film supports my point that the narrative strategies of “Complex Storytelling” have become widely available to viewers, especially when those strategies are adjusted to the demands of popular genres. Historically, such strategies became user-friendly, I maintain, partly because of the ingenuity demanded by mystery plotting.

Needless to say, spoilers loom ahead.

Revisiting and revising

The prototypical puzzle mysteries are associated with Anglo-American novels of the 1920s-1940s, the “Golden Age” ruled by talents such as Dorothy L. Sayers, Anthony Berkeley Cox, John Dickson Carr, Ngaio Marsh, Ellery Queen, and many others–supremely by Dame Agatha Christie. Similar books are still written today, often under the guise of “cozies” because they supposedly offer the comforting warmth of familiarity. Golden Age plotting flourishes in television too, in all those (largely British) shows about murder in supposedly humdrum villages.

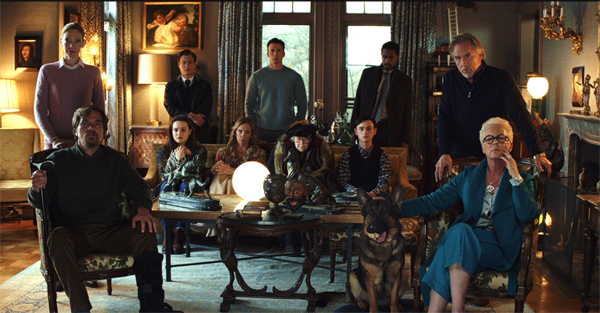

Knives Out relies on Golden Age conventions from top to bottom. A rich, odious family is overseen by a domineering patriarch, mystery novelist Harlan Thrombey. When he’s found dead in his mansion, apparently of suicide, his family members become nervous because each has a guilty secret. The conflicts are brought into focus when it’s revealed that Harlan changed his will so as to disinherit all his offspring. He leaves his fortune and his house to Marta Cabrera, the nurse who administered his medications and became his friend and confidant. Is there foul play? Investigating the case are are two policemen and the private investigator Benoît Blanc. They must decide whether Harlan’s apparent suicide is actually murder and if so, who’s the culprit.

Johnson organizes his plot around many classic techniques. In the Golden Age, writers tended to fill the action out to book length by adding more crimes, such as blackmail schemes or a series of murders. Both of these devices are exploited in Knives Out. Marta is apparently the target of an extortioner, and the family housekeeper Fran is the victim of a poisoner. The film also employs the least-likely-suspect convention (a favorite of Christie’s) and a false solution (another way to fill out a book). Johnson supplies traditional set-pieces as well: the discovery of the body, a string of interrogations of the suspects, the assembling of suspects to hear the will read, and a denouement in which the master sleuth announces the solution by recapitulating how the crime was committed.

The conventions are updated in ways both familiar and fresh. The sprightly music and the flamboyant bric-à-brac of Harlan’s mansion deliberately recall Sleuth (1972), another reflexive, slightly campy revisiting of murder conventions. Johnson wanted to evoke the all-star, well-upholstered adaptations of Christie novels like Murder on the Orient Express (1974, 2017) and Death on the Nile (1978, 2022). But he has courted younger audiences with citations (the title is borrowed from Radiohead) and social commentary, such as references to Trump, neo-Nazis, and illegal immigration. The Thrombey clan’s inability to remember what country Marta came from reminds us of something not usually acknowledged about Golden Age classics: they often provided satire and social critique of inequities in contemporary society. (In the book I discuss Sayers’ Murder Must Advertise as an example.)

Like earlier Christie adaptations, Johnson’s film has recourse to flashbacks illustrating how the crime was actually committed. In Benoît Blanc’s reconstruction of the murder scheme, rapidly cut shots illustrate how the family black sheep Ransom sought to kill Harlan by switching the contents of his medicine vials, which would make Marta the old man’s murderer. But her expertise as a nurse unconsciously led her to switch the vials again, so she didn’t administer a fatal dose. This forced Ransom to continually revise his scheme, chiefly by destroying evidence of Marta’s innocence and trying to murder Fran, who suspected what he had done.

All of this is carried by the now-familiar tactic of crosscutting Blanc’s solution with shots of Ransom’s efforts, guided by Blanc’s voice-over. At some moments, the alternation of past and present is very percussive, with echoing dialogue (“You’re not gonna give up that,” “You’ve come this far”). For modern audiences, this swift audio-visual revelation of the “hidden story” is far more dynamic than a purely verbal recitation like that on the printed page.

Johnson tries for a more virtuoso revision of a classic convention in treating the standard interrogation of the suspects. Lieutenant Elliott’s questioning, followed by questions posed by Blanc, consumes an astonishing sixteen minutes of screen time. Such a lump of exposition could have been dull. But the accounts provided by Harlan’s daughter Linda, her husband Richard, Harlan’s son Walt, his daughter-in-law Joni, and Joni’s daughter Meg are brought to life by flashbacks to the day of Harlan’s death. Aided by voice-over, we get a sharp sense of each character’s personality while the mechanics of who-was-where-when during the birthday party are spelled out. Some flashbacks are replayed in order to alert us to disparities in the stories, which stir curiosity and set up further lines of inquiry. The technique isn’t utterly new, though; in the book I show that such shifts across viewpoints emerged in mystery films from the 1910s onward.

The pace picks up when, instead of sticking to one-by-one witness accounts, Johnson starts to intercut them, showing varied responses to the same questions.

The editing creates a conversation among the witnesses, as one disputes the testimony of another. This freedom of narration, mixing different accounts in a fluid montage, plays to modern viewers’ abilities to follow fast, time-shifting narratives.

The use of voice-over to steer us through the flashbacks takes on new force when Elliott and Blanc question Marta. Her account of the fatal night is given not as testimony but as her memory. She recalls tending to Harlan after the party, starting a game of Go with him, and then discovering that apparently she gave him a lethal dose of morphine. She’s distraught, but he consoles her and instructs her in how to cover up her mistake. His scheme, which involves an elaborate disguise and a secret return to his bedroom, is designed to give Marta an alibi by showing her apparently leaving before he dies.

In her memory Harlan’s voice-over narrates her flashback as she executes his plan. But she doesn’t confess to Elliott and Blanc. Following Harlan’s instructions, Marta lies to exonerate herself. Her propensity to vomit when she tells a lie drives her to the commode, but the police don’t notice. She has apparently fooled Blanc, who considers that her account “sounds about right.”

In such ways Johnson retools scenes of the police interrogation for contemporary viewers. But he goes further in revising Golden Age tradition. Well aware of the tendency of the puzzle plot to indulge in plodding clue-tracing, he provides a deeper emotional appeal.

Immigrants get the job done

The Golden Age plot relies on an investigation, the scrutiny of the circumstances leading up to and following a mysterious crime, usually murder. Plotting came to be considered a purely logical game, a matter of appraising motives, checking timetables, pondering clues, testing alibis, and eventually arriving at the only possible solution. These conventions were canonized in books like Carolyn Wells’ Technique of the Mystery Story (1913) and in many writings by authors. But some writers recognized that the emphasis on a puzzle tended to eliminate emotion and promote a boring linearity in which the detective poked around a crime scene and questioned suspects one by one.

Authors sought ways to humanize the investigation plot. Sayers filled it out with romance, social commentary, and regional color. Hardboiled novelists like Hammett and Chandler, who relied on many Golden Age conventions, turned the investigation into an urban adventure, with the threat of danger looming over the private detective. Others tried to blend in elements of the psychological suspense novel, as Nicholas Blake does in The Beast Must Die (1938), which traces how a bereaved father searches for the hit-and-run driver who killed his son.

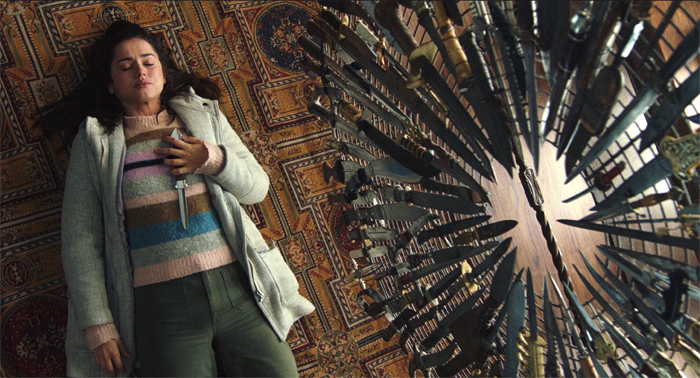

Rian Johnson tries something similar in Knives Out. Into the investigation of Blanc and the police, he inserts a woman-in-peril plot. Although we’re introduced to Marta early in the film, she’s pushed aside for about half an hour as the inquiry takes over in the interrogation sequences I’ve mentioned. Then Blanc takes a kindly interest in her and probes her knowledge of Harlan’s attitude toward his family. And then, after Lieutenant Elliott becomes convinced that it’s a suicide, Marta is questioned. At this point, she comes to the center of the film and becomes its sympathetic protagonist and central viewpoint character.

Her memory episodes reveal that she believes she accidentally killed Harlan. But out of self-preservation and obedience to his orders, she doesn’t confess. She tries to ease away from Blanc, but he asks her to be his “Watson.” The rest of the plot forces her to accompany the investigation. Panicked that her scheme will be revealed, she often tries to suppress evidence: futzing up surveillance footage, traipsing over the muddy footprints she left, trying to throw away a piece of siding that she dislodged that night. Marta’s situation recalls that in The Woman in the Window (1944) and The Accused (1949), and in the TV series Columbo, in which guilty protagonists must watch as their trail is exposed.

Marta’s only ally appears to be Ransom, Harlan’s ne’er-do-well grandson. He justifies his concern as partly selfish: If she gets away with it, she can share Harlan’s legacy with him. As in many domestic thrillers, this handsome helper is also a little sinister, but Marta accepts his advice for how to respond to an anonymous threat of blackmail. When Marta discovers that someone has nearly killed the housekeeper Fran, she vows to confess. By then, however, Blanc has solved the mystery and absolved her of guilt.

Johnson deliberately made Marta a center of sympathy as a way of humanizing the investigation.

Very early on in the game I wanted to relieve the audience of the burden of “Can we figure this out?”. . . . I don’t think that’s a very strong narrative engine to drive things. I think that’s very intellectual and that clue-gathering–after a while you recognize “No, I’m not gonna figure this out,” so you kind of sit back on your hands and wait for the detective to figure it out. . . .

So the notion of tipping the hand early and giving this false but very convincing picture from Marta’s perspective of “I’ve done this and I’m in a lot of trouble.” . . . Could we do that so you’re genuinely on the side of the killer?. . . Once you’ve done that it’s very interesting because of the mechanics of the murder mystery, the fact that you know the detective always catches the killer. . . . The looming threat is that we know how mysteries work and we know that the detective catches [the killer] at the end. And we’re worried for Marta. We’re worried, “How is she possibly going to get out of this situation?”

Johnson uses several other tactics to put us on Marta’s side. While the performances of the actors playing the Thrombeys leans toward grotesquerie, Ana de Armas plays Marta more naturalistically. In time-honored Hollywood fashion, Johnson also makes Marta ill-treated. She’s dominated by the family who pretends to love her, and as an immigrant she’s in danger of seeing her mother deported. When she is named Harlan’s heir, the family descends on her like predators. In the end, as in many psychological thrillers, the woman in peril turns into a resourceful combatant. She bluffs Ransom into confessing his scheme, and only when she vomits on him does he realize she’s fooled him with a lie. We can enjoy the innocent trapping the guilty.

The game’s afoot. Which one?

The Golden Age story is more than a puzzle. It’s posited as a game. Of course the murderer is at odds with the detective, with each trying to outwit the other. At another level, the game is a battle of wits between author and reader. John Dickson Carr sums it up.

It is a hoodwinking contest, a duel between author and reader. “I dare you,” says the reader, “to produce a solution which I can’t anticipate.” “Right!” says the author, chuckling over the consciousness of some new and legitimate dirty trick concealed up his sleeve. And then they are at it—pull-devil, pull-murderer—with the reader alert for every dropped clue, every betraying speech, every contradiction that may mean guilt.

Golden Age authors realized that the core mystery could be enhanced by techniques that both mislead the reader and drop hints about what’s really going on. The cultivated reader became alert not just for characters who might lie but for narration that was engineered to be misunderstood. Golden Age authors weaponized, we might say, every literary device to steer the reader away from the solution. The trick was to do this without cheating.

If this genre is a game, then, following sturdy British tradition, “fair play” becomes the watchword. Earlier detective writers, notably Conan Doyle, did not feel obliged to share all relevant information with the reader. The master sleuth was likely to discover a clue or a piece of background knowledge that he or she kept quiet, the better to flourish it in triumph at the denouement. Instead, Golden Age authors made a show of telling everything.

The concept of fair play was made explicit in Ellery Queen’s novels, which included a climactic “challenge to the reader” explaining that at this point all the information necessary to the solution was now available. (This device was replicated in the EQ TV series.) Even without this pause in the narration, Golden Age writers were careful to supply everything before the big reveal.

Knives Out is very much in the game tradition. It knowingly follows self-conscious “meta”-mystery films like Sleuth, The Last of Sheila (1973), and Deathtrap (1982), all of which flamboyantly exploit classic conventions (often with crime writers at the center of the plot). Accordingly, Johnson is aware of the need to play fair.

A straightforward example occurs in the interrogation sequence. Members of the Thrombey family tell Blanc and the police that Harlan’s last day with the family was a happy occasion. But the flashbacks reveal to us that they’re lying. We see Harlan fire Walt as his publisher, confront Richard with his infidelity, and cut off Joni’s funding for Meg’s tuition. Soon enough Blanc will intuit their deceptions and ask Marta for confirmation, but the flashbacks make sure we grasp their possible motives for killing Harlan.

But telling everything required telling some of it in deceptive ways. Otherwise, there’d be no puzzle. The craft of Golden Age fiction demanded skillfully planting crucial information that can be (a) recalled at propitious moments by the detective but (b) neglected by the reader (“I should have noticed that!”). Perplexing Plots traces various stratagems for achieving how authors muffled crucial information through ellipsis, distraction, and other tactics.

Consider Fran’s dying message. As Marta bends over her, Fran gasps, “You did this.” Since we’ve been led to believe that Fran is blackmailing Marta, it seems to confirm that she’s got proof of Marta’s guilt in the toxicology report. But the dying message turns out to be equivocal. Fran is actually saying, “Hugh did this”–identifying her would-be killer. Huh?

Early in the film when Ransom comes to the mansion, the police greet him as “Hugh Drysdale,” to which he replies, “Call me Ransom. Ransom is my middle name. Only the help calls me Hugh.” Fair play, but given to us in a distracting way. The line is played down: Ransom delivers it quickly as he’s turned from the camera and strides into the house, and the policemen’s reactions are more prominent in the shot.

To play fair, Johnson reiterates the name just before the revelation, when Blanc addresses him as “Mr. Hugh Ransom Drysdale.” Since in Fran’s scene we can’t tell the difference between “You” and “Hugh,” file this under Carr’s category of “legitimate dirty trick.”

As a result, anything can become a clue for interpretation/misinterpretation. But for Golden Age creators, authorial craft isn’t only a matter of producing clues. Clues are available to the investigators and are crucial to the solution. But at the same time the author can supply hints in the narration, addressed to us behind the backs of the characters. An instance in Knives Out is the title of one of Harlan’s books, glimpsed in a montage of his bookshelves. In a film reliant on syringes, The Needle Game would seem to be a tip-off.

Or a hint can become a clue eventually. After Marta’s wild night covering up her “crime,” she rushes home and takes refuge in front of the TV. As she nervously taps her foot, a close-up reveals a single bloodstain on her sneaker.

She’s unaware of it, but the stain opens the possibility that it could incriminate her later. The film lets us forget it until the very end, when Blanc says he knew she was involved in Harlan’s death from the start, when he spotted the bloodstain. The hint for us became a clue for him.

Golden Age plotting invites attention to minutiae of presentation. Although Agatha Christie is sometimes condemned as a clumsy writer, Perplexing Plots tries to show that she often mobilizes a flat style to mislead us. Similarly, the attentive viewer will notice little felicities in Knives Out. For instance, when we first see Marta return to the mansion through the forest path, a shot shows her leaving the tracks she’ll later try to smear over. But in Blanc’s reconstruction, we see Ransom returning to the mansion by balancing on the wall lining the path, so as to leave no traces in the mud.

Had Ransom walked on the path, Johnson would have been besieged by Twitter complaints.

All this is a matter of self-conscious artifice. As Johnson notes, few readers take seriously the task of solving the mystery themselves. One member of the Ellery Queen collaboration admitted: “We are fair to the reader only if he is a genius.” The fair-play convention is at once a pretext for the display of authorial ingenuity and a source of artistic power–proof that a plot can harbor a hidden intricacy unsuspected by the reader. One dimension of connoisseurship in the classic mystery is the reader’s admiration of artifice, a taste for elaborate construction. If it’s all in the game, then we’re no longer committed to mundane realism. A portrait can whimsically change from scene to scene.

Henry James argued for a through-composed form of the novel, where every detail was carefully judged for its effect and its balance with others. An unexpected legacy of Jamesian formalism, I think, was the Golden Age authors’ ambition to make each story a tour de force, a test of readers’ skills and a revelation of unexpected resources in storytelling technique. Mystery stories are ingenious, as Ben Hecht noted, because they have to be.

The film’s rapid pace, time-shifting, and looping replays exemplify current tastes for what’s been called Complex Storytelling. But one task of my book is to suggest that popular storytelling has been complex for quite a while. The techniques have become refined and revised, and their appeal has been sharpened by emerging audiences (e.g., in the 1990s) and new technologies (e.g., video that allows replays).

We were sensitized to these techniques by mystery fiction throughout the century. The play with incompatible viewpoints, reruns of action bearing new significance, the strategic use of ellipsis–all are there in the Golden Age tradition. Likewise, the notion of fair play persists in all those “twist” films that flash back to show us actions that take on a new significance. Golden Age strategies, and mystery plotting more generally, have prepared audiences to expect pleasurable but “fair” deception in all genres. Knives Out, among other accomplishments, helps us understand how today’s sidewinding stories have roots in a genre that’s too often dismissed as mere diversion.

The quotations from Rian Johnson come from the Blu-ray supplement to Knives Out, “Planning the Perfect Murder,” between 2:21 and 4:20. The supplementary material on the disc is exceptionally detailed and reveals Johnson’s keen knowledge of the history of mystery fiction and film.

Exceptional studies of Golden Age mysteries are LeRoy Lad Panek’s Watteau’s Shepherds: The Detective Novel in Britain (1979) and Martin Edwards’ Golden Age of Murder (2016), The Story of Classic Crime in 100 Books (2017), and The Life of Crime: Detecting the History of Mysteries and Their Creators (2022). See also Mike Grost’s encyclopedic site A Guide to Classic Mystery and Detection.

For another good example of Golden Age misdirection appropriated in cinema, see this entry on Mildred Pierce.

Perplexing Plots is available for pre-order here and here. This is a good place to thank Sarah Weinman and Yuri Tsivian for their favorable comments on the book, which are available on these sites.

P.S. 9 August: I now realize I neglected to mention that Joni’s daughter Meg isn’t as harshly characterized as the rest of the Thrombey clan. She’s a friend to Marta and Fran and seems genuinely to care about Marta’s fate. However, she’s still a pothead who walks out of her benefactor’s birthday party and who colludes with the family to call Marta to get information. In plot terms, she’s one more threat to Marta.

Although we didn’t discuss this point, I thank John Toner of Renew Theaters for amiable correspondence about Knives Out.

Knives Out (2019).