Archive for the 'National cinemas: Israel' Category

Everything new is old again: Stories from 2017

Silence.

DB here:

This is a sequel to an entry posted a year ago. Like many sequels, it replays the ending of the original.

I don’t want to leave the impression that as I’m watching new release a little homunculus historian in my skull is busily plotting schema and revision, norm and variation. I get as soaked up in a movie as anybody, I think. But at moments during the screening, I do try to notice the film’s narrative strategies. Later, when I’m thinking about the movie and going over my notes (yes, I take notes), affinities strike me. By studying film history, most recently Hollywood in the 40s, I try to see continuities and changes in storytelling strategies. These make me appreciate how our filmmakers creatively rework conventions that have rich, surprising histories.

Parts of those histories are traced in the book that came out in the fall, Reinventing Hollywood. Some of my blog entries have already served to back up one point I tried to make there: that contemporary filmmakers are still relying on the storytelling techniques that crystallized in American studio films of the 1940s.

Relying on here means not only utilizing but also, sometimes, recasting. In keeping with earlier entries (including one from the year before last), I want to explore some films from 2017. These show that the process of schema and revision creates a tradition. Hollywood is constantly recycling, and sometimes revitalizing, Hollywood.

Of course here be spoilers.

Back to basics

The Big Sick.

The US films I’ll be considering all adhere to canons of classical Hollywood construction. Some of these are laid out in the third chapter of Reinventing.

Classically constructed films have goal-oriented protagonists who encounter obstacles, usually in the form of other characters. The goals are often double, involving both romantic fulfillment and achievement in some other sphere. (Somewhere Godard says that love and work are the only things that matter. Hollywood often thinks so too.) Alternatively, the goal might be prodding someone else to action (Three Billboards outside Ebbing, Missouri). Often there’s a clash between the goals, as when work tugs the protagonist away from love (La La Land).

The plot is typically laid out in large-scale parts. A setup is followed by a complicating action that redefines character goals. In Downsizing, once Paul has gotten small, he has to reconceive his goals in the face of his wife’s last-minute defection from their plan. There follows a development section that delays goal achievement through characterization episodes, backstory, subplots, parallels, setbacks, digressions, twists, and new obstacles. That marvelous slab of show-biz schmaltz, The Greatest Showman, relies for its development on a potential love triangle and a secondary couple’s romantic intrigue.

There follows a deadline-driven climax that resolves the action and an epilogue (sometimes called the tag) that celebrates the stable state achieved and perhaps wraps up a motif or two. The Greatest Showman presents Barnum’s success in creating a genuine circus and reconciling with his family. The tag shows a big production number, with the subplot resolved (Carlyle embracing Anne) and the motif of swirling points of light—initiated in Barnum’s spinning Dreams gadget—washing over the final spectacle and his daughter’s ballet performance.

Classical narration—what’s usually called point of view—typically attaches us to the main characters. But not absolutely: we’re usually given access to things they don’t know, mostly for the sake of arousing curiosity and suspense. And throughout, the film is bound together through recurring motifs that reveal character (and character change) or significant plot information. Think of the roles Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2 assigns to “Brandy, You’re a Fine Girl,” Pac-Man, David Hasselhoff, and that “unspoken thing.”

Or take The Big Sick, a semi-serious romantic comedy. Kumail’s initial goal is success in standup comedy, but he also falls in love with Emily. His Pakistani-American family constitutes the main antagonist, as his mother and father want him to go to law school and submit to an arranged marriage. He hasn’t told his family about Emily, which precipitates the couple’s big quarrel: “I can’t lose my family.” Kumail’s goal shifts when Emily is stricken by a mysterious disease. In the development section , as she lies in a coma, he gets to know her parents, and a tense sympathy develops between them. The crisis comes when Kumail confesses his true goals to his parents, they disown him, and Emily’s disease hits a life-threatening phase.

In the climax portion, Emily revives and breaks off with him, his parents grudgingly accept his move to New York, and he mounts a somewhat successful one-man show there. The film is tightly tied to Kumail’s range of knowledge, so we’re surprised when he is—as when Emily’s parents decide to move her to another hospital, and when Emily pops up in his New York audience, ready to reconcile with him.

The Big Sick exploits many comic motifs: the parade of would-be fiancées Kumail’s mother invites to dinner, the photos he keeps of them (which ignite Emily’s jealousy), the repeated sit-downs he has with his family, the dumb catchphrases deployed by other comics, and especially Emily’s “Woo-hoo!” heckling, which eventually attests to the rekindling of their love.

The power of classical plotting is shown in its ability to spotlight a Pakistani-American protagonist, an Islamic family demanding that a son adhere to tradition, and the pathos of parents facing the death of a daughter. But that ability to flexibly absorb new subjects and themes and emotional registers has kept the classical template going for about a century.

Time travel

Wonder Woman.

One of the hallmarks of Forties cinema, I argue in Reinventing’s second chapter, is a eagerness to explore what flashbacks can do. Flashbacks were already well-established, but a more pervasive acceptance of nonlinear storytelling, so familiar to us now, became firmly part of Hollywood sound cinema in this period.

One-off flashbacks are so common now we don’t particularly notice them. In The Big Sick, when Kumail visits Emily’s apartment with her parents, he peeks into her closet, and we get glimpses of her wearing the outfits earlier in the film. In this case, flashbacks function as memories. At the climax of Guardians 2, Quill flashes back to moments of listening to music with his mother. Similarly, in Get Out, Chris recalls his childhood TV viewing and, at the climax, he remembers earlier moments at the Armitage garden party when he asks, “Why black people?”

Flashbacks usually aren’t pure representations of memory, though. They often include information that the character doesn’t or couldn’t know. In fact many flashbacks are addressed simply to us, coming “from the film” rather than from a character’s mind. These may remind us of things already seen, or fill in gaps, or plant hints about things that will develop.

So, for instance, in Logan Lucky, when Logan says, “I know how to move the money,” we get a flashback to him studying the pneumatic pipes that feature in the heist plan.

He’s not necessarily recalling the moment; the filmic narration seems merely to be tipping us the wink. At the climax, other “external” flashbacks plug gaps we didn’t notice earlier. These reveal some aspects of the heist we weren’t aware of, such as the extra bags of money carried off.

1940s filmmakers also explored how flashbacks could be “architectonic,” how they could inform the overall shape of the movie. Here the flashback rearranges story order to build up curiosity and suspense, and it may come from purely from the narration or be motivated as character memory.

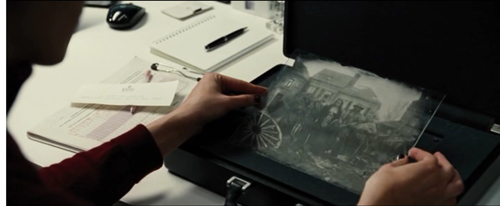

One large-scale pattern is the extensive embedded flashback, as in How Green Was My Valley, I Remember Mama, and innumerable biopics. Wonder Woman gives us a framed inset of this sort, when a modern-day Diana opens the chest harboring the World War I photo. That scene segues to the past. The origin story and war episodes are ultimately closed off by a return to the present, and a reminder of a motif—Steve’s watch (which, in one of the film’s jokes, stands in for something more private). The purpose of this is to provide what I call in the book “hindsight bias.” While building curiosity about the past, the opening primes us to expect certain things to have been inevitable (such as chance meetings).

Another common framing strategy begins at the climax and then a long flashback lays out the conditions that led up to it. A reliable source tells me that Pitch Perfect 3 does this, starting with an explosion followed by a title announcing that the action began three weeks earlier. In films like this, there may be no closing frame; the internal action of the flashback catches up, perhaps via a replay, with what we saw at the outset, and the film proceeds to the resolution and epilogue. The somewhat phantasmic opening number of The Greatest Showman comes to fruition during the finale.

To and fro

Loving Vincent.

Sustained blocks like this are fairly rare nowadays, I think. More common, as in the Forties, is an alternation of past and present. The main examples in Reinventing Hollywood include Passage to Marseille, The Locket, Lydia, Kitty Foyle, and Sorry, Wrong Number. Again, though, these are motivated as memories, while current examples tend to be more “objective.”

A simple instance is Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. Here clusters of events in 1981 alternate with incidents in 1979: Gloria Grahame returns to her young lover, and we flash back to their earlier affair. Neither protagonist is firmly established as recalling the 1919 events. Another feature of 1940s flashbacks, the replay from different viewpoints, comes in here as well. The couple’s crucial quarrel in New York is shown first from Peter’s perspective, and later from Gloria’s. He suspects her of infidelity, but we learn that her secret involves her cancer. As often happens, our restriction to the protagonist is modified by knowledge he doesn’t gain at the moment.

The alternation of past and present is given a more geometrical neatness in Wonderstruck. In maniacally precise parallels, Rose in 1927 runs away to Manhattan to find her mother, while in 1977 Ben runs there to find his father.

The parallels are reinforced by a host of motifs: wolves, movie references, the asteroid in the Museum of Natural History, a bookmark, and so on. The linear chronology gets straightened out, and the gaps filled, by an integrative flashback played out among miniatures and cutouts adapted to the scale model of Manhattan. The dovetailing flashbacks create a sense of cosmic design; in many films, convergences like these can suggest destiny.

For modern audiences, Citizen Kane is the prototypical flashback film of the 1940s, and its investigation structure, while not completely original, was hugely influential. I was surprised to see Kane’s schema revived this year in Loving Vincent. Once the postman has given Armand his mission, to take Vincent’s last letter to brother Theo, we embark on an inquiry into Vincent’s life and death. It’s refracted through the testimony of many who knew him during his sojourn in Arles. Armand’s goal gets recast when he learns of Theo’s death, but in the course of his travels he comes to understand how Vincent’s kindness and art touched many lives.

As in several Forties films, Loving Vincent’s past scenes jumbled out of chronological order, so we must piece together the story Armand gradually discloses. And there’s the driving force of mystery, a distinctive thrust in many Forties genres, for reasons I talk about in one chapter of Reinventing. Very modern, and not so much like the 1940s, is the brief, fragmentary quality of the flashbacks; I counted thirty-six of them.

The boldest experiment in nonlinear time I saw this year was Dunkirk. The film juxtaposes timelines consuming a week or so, a day, and an hour, and then aligns them in unexpected ways. In this staggered array, the distinction between flashbacks and flashforwards loses its force. Any cut may constitute a jump ahead of the moment just shown, or a jump back to an earlier incident. Christopher Nolan has acknowledged the influence of 1940s cinema on his thinking about time schemes, and here he explores yet again how crosscutting different lines of action can stretch or condense story duration.

Their eyes and ears

Get Out.

Like flashbacks, subjectively tinted storytelling has a long cinematic lineage. Silent films displayed dreams, visions, anticipations, and deformations of mind and eye. Those devices mostly dropped out of 1930s American cinema, which was to some extent more “objective” and “theatrical” in its mode of presentation. Subjectivity came roaring back in the Forties, which is why Reinventing Hollywood devotes two chapters and several other passages to various techniques that go beneath the surface.

Memory-based flashbacks are common options today, but the inward plunge can take other forms. For most of its length, Get Out restricts us to Chris’s range of knowledge, and it relies on optical POV in many stretches. Through his eyes we see Mrs. Armitage staring at him while stirring the tea.

More complex is his view of Georgina at the upper window. That’s followed by a shot going beyond his range of knowledge: she’s looking not at him but herself.

We take a deeper dive into Chris’s mind under hypnosis. The boy Chris sinks into a stellar cavity and becomes Chris staring at Mrs. Armitage as if she were appearing on the TV screen. The shift dramatizes his guilt at his mother’s death and his susceptibility to this Bad Mom figure.

Once Chris becomes a prisoner, the narrational range widens again to show Rod’s efforts to rescue him, along with the family’s plans for him. But the film tightly realigns us with Chris at the climax, so that the attacks from Rose, Jeremy, and others come as surprises.

Chris, a photographer, channels his experience through vision, though the hypnotism scene blends sounds from the present with the rain drizzling in the past. Subjectivity goes more fully sonic in Baby Driver, about a whey-faced lad who lives in the auditory ether.

Edgar Wright, now exercising straight the percussive dashboard details he parodied in Hot Fuzz, punches up the visual exhilaration of Baby’s rubber-shredding takeoffs and getaway 180s. He locks us into Baby’s auditory world as well. We’re almost completely attached to Baby, learning what he learns when he learns it. Notably, the robberies are rendered from his perspective, including optical POV shots as he waits in the getaway car.

Again, fragmentary flashbacks replay his mother’s death and the childhood damage to his hearing. We even get a fantasy, with Baby imagining his escape with Debora in black and white.

What’s just as subjective, though, is the music Baby incessantly cues up on his iPod. Blocking out the shriek of his tinnitus, it provides a soundtrack to his life—danceable tunes as he bops down the street, ballads when he flirts and falls in love with Debora, and pulsing rock during robberies (what the psycho Bats calls, “a score for a score”). Through volume and texture, Wright suggests that we hear the music as Baby does; only the loudest environmental sounds poke through. Sometimes, when he pulls out one earbud, the volume drops. His growing attachment to Debora is signaled by his dialing up a song using her name and sharing his precious buds.

Some scenes are handled objectively, as we witness the gang’s conversations in front of Baby. He can read lips, though, and he can keep the iPod cranked up. So a little bit of Baby’s custom soundtrack leaks in for us underneath others’ dialogue. At other times, the score takes over to become nondiegetic accompaniment, as when gunshots in a firefight land on the off-beats of “Tequila.”

As you’d expect, the music comments on the action throughout (“Never ever gonna give you up” when Baby defends Debora from Buddy) and supplies motifs. Queen’s “Brighton Rock,” Baby’s favorite heist accompaniment, briefly enables him to bond with Buddy.

A song about a couple’s devotion reminds us that both thieves are loyal to their women.

Momentary sound changes are rendered through our protagonist’s viewpoint. Wright lets us hear the whine of Baby’s tinnitus as Bats taps his ear. When Buddy blasts his pistols alongside Baby’s head, we suffer his hearing loss and the distorted voices that wobble through it.

Such streams of auditory perception occasionally emerged in early talkies (e.g., Gance’s Beethoven). Those experiments got normalized in 1940s manipulations of sound perspective in different environments. More fancily, in A Double Life (1947), party chatter subsides when the hero covers his ears, and in Pickup (1951), the gradually deafening protagonist hears high-pitched noises. Wright extends these one-off devices to the texture of an entire film.

Confidants

The Keys of the Kingdom (1945).

Large-scale and small-scale, the heritage of the 1940s seems to be everywhere. Many of the flashbacks and fantasies I mentioned already are primed by a track-in to a character’s face, just as in classic studio pictures. There’s also block construction, either unsignaled as in the Wonder Woman and Greatest Showman cases, or signaled, as in the date-stamping in the early alternations of Film Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool. We also get explicit chaptering, as in The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected) and Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer.

Voice-overs come along with flashbacks, as a way of guiding the audience to understand the time shifts. In the Forties, as I discuss in the book’s sixth chapter, voice-overs became more flexible and fluid. Sometimes they were external, issued from an all-knowing commentator (Naked City and other police procedurals). Sometimes they were sonic equivalents for letters and diaries, letting us in on what characters were writing. Deeper intimacy could come from voice-overs serving as inner monologues, the voice of a character’s mind. These, like flashbacks, are associated with film noir, but also like flashbacks they actually emerge in many genres–as they do today.

The voice-over can be perfunctory, as in All the Money in the World. Young Paul Getty, kidnapped in the opening reel, has a couple passages confiding in us, but he’s not heard from again. Moreover, his explanation of his grandfather’s rise to power (during the inevitable flashbacks) could have been supplied in other ways. Paul baldly tells us that we need to know all this to understand what follows (who’s he talking to?). He admits that he’s an expository shortcut. This is why voice-over is sometimes considered lazy storytelling.

It doesn’t have to be. Take Martin Scorsese’s Silence. In subject and strategy it reminded me of The Keys of the Kingdom (1945), which dramatizes the diary of a young missionary to China. Via this novelistic device, we get flashbacks to his youth and his years of service. We get as well the reaction of the skeptical priest whose voice reads the journal. This fairly straightforward schema is in effect revised by Scorsese and co-screenwriter Jay Cocks, who create a floating dialogue among voice-overs.

After initial exposition via an old letter from Father Ferreira, which is recited in his voice, two young priests set out for Japan. They hope to maintain the clandestine Christian community there, and they want as well to discover if Ferreira has truly renounced his faith . The bulk of their grim adventures is commented on through the voice-over of one of them, Father Sebastião Rodrigues. At first he’s vocalizing a letter, which he calls a report, summing up the struggles of the Jesuit mission and their encounters with Christian villagers. In the course of his report, we also get an embedded flashback narrated by Kichijiro, their guide and a sporadically lapsed believer himself.

But at a crucial moment, Father Sebastião’s report ceases to be such and turns into an inner monologue. Seeing a Christian village devastated by the shogun’s forces, he asks, “What have I done for Christ?”

Soon his voice presents a kind of stream of consciousness–praying for the villagers as they walk off in captivity, thanking God when he has a vision of Jesus on his prison wall. His inner voice urges his colleague Father Garupe, severely tortured, to apostatize.

In last stretch of the film, new voices are heard. There’s Jesus, perhaps filtered through Sebastião’s mind (subjectivity again), and then, more objectively, there’s an account from the Dutch trader Albrecht. He drily reports that Sebastião apostatized and followed Ferreira in leading a Japanese life. Albrecht’s narration is interrupted by a dialogue between Sebastião and Jesus, capped by the priest’s blurting out: “It was in the silence that I heard your voice.” Albrecht’s voice-over concludes the film, with his final claim that the priest was “lost to God” belied by the closing image.

From the 1940s onward, voice-over has been a rich resource–describing settings and external behavior, judging other characters’ motives, giving us access to the deepest thoughts of the speaker. I try to show these capacities at work in a fairly ordinary film, The Miniver Story, but for our time, the soundtrack of Silence is another vivid demo. In the juxtaposition of different voices, it achieves some of the density of a novel, and by the end we better understand the initial words and emotions of Father Ferreira, the priest whose apostasy launches the plot.

Passed-along voice-over gets a bigger workout in Dee Rees’s Mudbound. The original novel is somewhat like As I Lay Dying; its sections set various characters’ voices side by side, shifting viewpoint as each takes up a portion of the tale. Constant commentary and perfect alignment with a character’s range of knowledge are hard to sustain in cinema, so what we have onscreen are objectively presented scenes accompanied by an occasional voice-over. Still, it’s a rare option. If Silence gradually opens its voice-over horizons near the film’s end, Mudbound introduces polyphony from the start. Six characters share their thoughts and feelings in alternation, providing backstory and deepening our access to their reactions.

As in Silence, there’s a pattern to the voice-overs. The bulk of the film is an embedded flashback, triggered by the McAllen brothers setting out to bury their father and encountering the Jackson family riding by.

The intersection of two families sets up not only the flashback episodes but the floating voice-overs. As the visuals anchor us initially to the white family, the first voice-overs issue from Laura, the wife of Henry McAllen, and from Henry’s brother Jamie. In the flashback stretch, as America enters World War II, the voice-overs shift to the Jacksons, the father Hap and the mother Florence. The plot proceeds to add the voices of Henry and the Jacksons’ oldest son Ronsel. All the characters narrate the action in the past tense, as if recalling it from a distance in time, but no listener is ever specified–a common feature of voice-overs in the 1940s and afterward.

During the film’s second half, the development and climax sections, the voice-overs nearly vanish. For over an hour, we hear only Laura and Florence, and only once apiece. Jamie and Ronsel, both disaffected returning vets, don’t confide in us during their growing friendship or during the persecution of Ronsel by the local white men. The women are left to provide a sporadic chorus.

At the end, however, a spurt of brief commentaries give the men their inner voices back. We return to the present and see Hap Jackson help the McAllen men bury their father (the inciter of KKK violence against Ronsel). The epilogue features brief comments from Ronsel, Jamie, and Hap, and not the women. Ronsel gets the last word. Ironically, because of the KKK savagery, this narrator has become mute.

Again, I felt a current film’s kinship to those I studied for the book. Mudbound traces the rural home front, the military experiences of a white man and a black one, and the veterans’ problems of adjustment upon returning home. These elements hark back to some of the powerful films of the 1940s, including Home of the Brave and The Best Years of Our Lives. The sympathetic portrait of African-American families isn’t unprecedented either, as seen in Intruder in the Dust and Lost Boundaries. Mudbound‘s passed-along narration, like the ones we find in other modern films, constitute contemporary revisions of the shifting voice-overs we get in Citizen Kane and All About Eve.

Career women careening

Molly’s Game.

Molly’s Game and I, Tonya offer good wrapup examples of many of these strategies, with some unreliability thrown in.

As you’d expect in a film by Aaron Sorkin, the flashback organization of Molly’s Game is fairly complicated. Just as The Social Network intercut two arrays of flashbacks triggered by two legal inquiries, the new film scrambles together crucial moments in Molly’s childhood , scenes of her current legal troubles, and sequences showing her rise to become the Poker Princess, the arranger of high-stakes games. The film gains a bit of the structural symmetry of Wonder Woman by beginning and ending with a childhood defeat that Molly rises above.

The flashbacks are stitched together by Molly’s voice-over. A filmmaker who recruits a narrating voice has to choose. Do you show the narrating situation? Or do you leave it unspecified? In this last instance, the narration might be wholly internal, a mental summing up of events, or it might feel like a confidence shared with an intimate, even though we’re shown no listeners. In Molly’s Game, her bare-it-all confession might seem to be simply her unspoken thoughts, but at one point it’s suggested that what we’re getting is her book’s version of her life.

Molly’s attorney Charlie is reading her memoir while he researches her case, and he asks her about a passage we saw in a flashback: her boss chews her out for bringing him “poor people’s bagels.” The attorney suggests that nobody uses that phrase, and that probably the boss used a racial slur that she suppressed in the book. This throws a little bit into question the reliability of Molly’s flashback, while also hinting at something we learn later: she sanitized the book to spare the reputations of the high rollers she serviced.

I, Tonya takes another option. Again there are disordered flashbacks and bursts of subjectivity tied together by the voice track. Whereas Molly is the sole speaker in her film, though, Tonya shares the soundtrack with other characters, in the manner of Mudbound. But these commentaries aren’t private musings. They’re the self-justifying testimony of people talking to a documentary camera. (Even though these sequences are said to be occurring forty years after the earliest events, the format is an anachronistic 4:3–presumably to help us keep the time frames distinct.

Once you get characters in conflict recounting past events, you have the possibility of disparate stories. Forties filmmakers exploited this in Thru Different Eyes and a certain Hitchcock film too famous to mention. Tonya says explicitly that there are different versions of the truth. A brief scene shows her battering Nancy Kerrigan, and a more complicated one occurs in a tale recounted by her husband Jeff. She fires a shotgun at him and turns to the camera saying, “I never did this”–before briskly ejecting a shell.

The comic possibilities of to-camera address on display here were exploited in My Life with Caroline, Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House, and other 1940s films. Then the momentary breaking of the fourth wall was reserved for the frame story and kept separate from the embedded flashbacks. But I, Tonya‘s revision is easy to understand as a zany equivalent for her verbalized denial. Given the defiant way she brandishes the gun, we’re permitted to doubt her denial–which means that the film is refusing to settle the matter. The possibility that the overall filmic narration could be unreliable was rehearsed occasionally in the Forties, perhaps most vividly in Mildred Pierce (analyzed here, sampled here).

Other paths

Foxtrot.

The 1940s were important for other national cinemas too. The book’s last chapter suggests that filmmakers in Britain, France, Mexico, and other countries engaged in similar narrative explorations–sometimes in imitation of America, sometimes on their own. I go on to suggest that eventually non-Hollywood narrative models came to international attention, and still later those affected American cinema.

Italian Neorealism was a prime source of alternatives. A good example of its long-term impact, I think, is The Florida Project, which embraces a slice-of-life pattern. Once you’re committed to episodic plotting, you need to organize the incidents coherently. Sean Baker follows European and US indie precedent in tracing a rhythm of daily routines that change in sync with the characters’ relationships. So Halley’s quarrel with her friend Ashley means that Moonee can no longer claim leftover food from the diner, which helps push Halley toward prostitution, which leads to the intervention of child welfare authorities.

The drama arises less from crisply defined goals than from circumstances that alter life routines. In addition, like many Neorealist films and others in this vein afterward, the poignancy gets sharpened by the presence of children caught up in adults’ bad choices.

The Florida Project presents many actions elliptically, leaving us to infer what has happened offscreen. (I think, for instance, that it’s motel manager Bobby Hicks who contacts the authorities, but I don’t think it’s made explicit.) Moving to films made outside the US, Michael Haneke’s Happy End takes ellipsis even further.

Haneke uses the strategy of delayed and distributed exposition. He presents some apparently casual events at the outset, then gradually reveals what’s actually going on, all the while tracing out ultimate consequences. Instead of presenting a clear-cut chain of causes and effects, he asks us to fill in unspoken plans, offscreen actions, and hidden motives. Haneke has specialized in suggesting how vague forces can disturb rich, smug families and their shady schemes. His mystery-driven narrational tactics suit Happy End as well as Code inconnu and Caché.

I speculate in Reinventing Hollywood that the European art cinema’s story-based mysteries and narrational uncertainties owe something to 1940s American films. So too perhaps does the use of block construction, which emerged in overseas portmanteau films of the postwar era (e.g., Dead of Night, Le Plaisir, The Gold of Naples). Samuel Maoz’s Foxtrot is a striking example of block construction.

His Lebanon (2009) took POV restriction to a limit by confining its action to a military tank in the heat of battle. (This tactic has Forties precedents as well, as Lifeboat and Rope remind us.) Foxtrot operates differently. Broken into three parts, it looks at a single situation–a young soldier’s duties at a checkpoint–through shifts in time and viewpoint. The opening shot, at first enigmatic, gets specified in an epilogue that recasts all that went before. Maoz also incorporates monotonous routines into his plot, the better to throw a single shocking incident into relief.

So classical construction isn’t the only option available. But other choices have histories as well. As viewers we learn these alternative stoytelling traditions, and we use that knowledge to make sense of new examples. No less than the Hollywood model, these other formal strategies engage us through familiar pattern and unexpected novelty, schema and revision.

I don’t mean to obsess over this 1940s thing. Our current films owe debts to silent cinema and to other eras too. It’s just that I continue to be fascinated by finding repetitions and variants of storytelling strategies that got consolidated in the period I was studying. Denounce them as formulaic if you want, but I prefer to think that these and other recent films illustrate, in fine grain, the continuity and sometimes the vitality of a major cinematic tradition.

Maybe this is my hook to an entry for the start of 2019?

Many thanks to Michael Barker of Sony Pictures Classics for help on this entry.

On the four-part structure of classical films see Kristin’s 2008 entry and my essay “Anatomy of the Action Picture.” Today’s entry deploys the analytical categories trotted out at length in this essay and more briefly in this discussion of The Wolf of Wall Street.

Guardians of the Galaxy Vol. 2.

Middle-Eastern fare at VIFF

Winter Sleep.

Kristin here:

Iranian cinema moves on

Maybe it’s just the particular selection of Iranian films at this year’s festival, but I sensed a shift from the ones we’ve seen in previous years. Last year I titled one of my entries “Familiar Middle-Eastern filmmakers return to Viff.” This year familiar names are missing, including Kiarostami, Panahi, Rasoulof, and Farhadi. (Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s new feature, The President, was at Venice but not here at VIFF.) Moreover, all three of the Iranian fiction features this year depart from some conventions we’ve grown used to in the New Iranian Cinema of the past decades.

Whether A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night (2014) is actually an Iranian film is debatable, though it is listed as such in the program. Its director, Ana Lily Amirpour, was raised in England and subsequently moved to the USA, where she studied filmmaking at UCLA. A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night is her first feature and has American backing (including Elijah Wood as one of several executive directors) and was shot in California. Amirpour is of Iranian descent, and the film is in Farsi, which may be enough to have it considered Iranian.

It’s hard to imagine, however, such a film being made in Iran. It’s a vampire film, taking place in an imaginary town called Bad City, perhaps located in Iran but perhaps not. Its setting look distinctly like the less picturesque parts of the American West:

Amirpour has fashioned a remarkably good pastiche of an American widescreen, black-and-white genre film of the late 1950s or early 1960s, as this image and the one at the bottom of this entry demonstrate. As the Variety review points out, the look is also informed by graphic novels, notably Sin City. Indeed, this summer Amirpour has published a brief graphic novel with the same title as her film; it’s apparently a prequel to the movie’s story. Given that it is labeled #1, the artist presumably envisions a series.

The genre is the vampire film, though this one is hardly conventional. The vampire is the Girl of the title, and the director has taken amusing advantage of the resemblance between her triangular black hijab and the classic floor-length cloak worn by screen vampires, such as that of Bela Lugosi in the 1931 Dracula:

The heroine moves eerily through the streets of the town (see bottom), picking as her victims men who have exploited women. A romance develops between her and a more sensitive young man, clearly modeled on James Dean.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night played at Sundance and has been picked up for American Distribution by Kino Lorber, apparently with an October release planned.

The two other Iranian films are what David has dubbed “network narratives.” One is straightforwardly so, the other far less so.

Rakhshan Bani-Etemad’s Tales (2014) in some ways develops on the classic quest narrative of so many Iranian classics since the 1980s, where hero or heroine (often a child) doggedly set out to accomplish something, with the struggle laid out in detail. In Tales the questing characters are multiplied, with their paths crossing and sometime re-crossing.

Unlike in most of the earlier films, these quests don’t always yield results, and hence closure. The characters are mostly involved in seeking help of some sort, sometimes from other people, sometimes from a government institution. The cumulative effect is to suggest a society that has lost the ability or the will to respond, even to desperate pleas.

The film begins with a filmmaker riding in a friend’s cab, shooting the passing cityscape. He immediately drops out of the story, though he will return. Ironically, the story’s action begins with a failed attempt to help someone. The cab driver is hailed by a prostitute with a sick child. Recognizing her as an old friend of his family’s, he buys medicine and a toy for the child, only to find that the woman has disappeared into the night.

Arriving home, he tells his mother of this encounter. We then follow her in a scene in an office building, where she tries to fill out a form complaining about not having received her pension. A gentleman in the corridor helps her, and we follow him into a meeting with a petty bureaucrat who takes calls from his wife and mistress, ignoring what the man is trying to tell him.

A central scene returns to the mother, now on a bus of protestors. The same filmmaker whom we saw at the opening is making a film about their personal plights. We watch through the viewfinder as the mother pleads for help. It’s not clear whom the film is aimed at or who will eventually see it. Later in Tales, the filmmaker remarks that all films eventually get seen, but this seems far too vague to hold out much hope for those caught in a maze of bureaucratic red tape and neglect.

The network structure reportedly resulted from the fact that under the Ahmadinejad regime Bani-Etemad could only get a license to make a series of shorts. Subsequently she was able to weave these together into a feature.

Bani-Etemad, who also produced Tales, is considered Iran’s top female director. Here she brings back some characters from her earlier films, including Dr. Dabiri, from Gilaneh (2005), and Sarah, from Nargess (1992). The VIFF program quotes her as saying, “Tales returns to the characters of my previous films under today’s circumstances.”

Finally there is Fish and Cat (2013), which elicited mostly praising reviews when it debuted in Venice. (For an example, see our friend Alissa Simon’s take on it for Variety.)

Despite running a lengthy 134 minutes, director Shahram Mokri shot the entirety as one lengthy take, without benefit of CGI. A sinister mood is set up immediately when a title hints that it will concern some restaurant owners in a remote district who may have used human flesh in their meat dishes. Two owners of the restaurant are introduced in the opening scene, and we follow them as they set out on a path through the nearby woods, carrying weapons, tools, and a bag soaked in what looks like blood:

The pair chat until their path crosses that of Kazim, a young man participating in an annual kite-flying event to take place by a nearby lake; he’s trying to ditch his clinging father. We follow him to the lake, then leave him to latch onto Parviz, who is trying to organize the young people arriving for the event. And so it goes, until eventually the brief scenes between the people who meet and part begin to repeat, but from a different vantage point. Much of the action involves the camera tracking with the characters from behind, as in the frame above, resulting in an occasional difficulty in identifying whom we’re watching.

The tone remains ominous throughout, with the two thugs and a third accomplice intruding at intervals, perhaps with murderous intentions. There’s also plenty of dark humor as well, and despite the slow unrolling of the action, the film remains absorbing throughout. Some viewers will be tempted to see the film on DVD/BD again, trying to work out the complicated looping chronology of the plot–possibly diagramming it, as the filmmakers presumably had to.

Those who can’t do

We wrote about Israeli director Nadav Lapid’s first feature, Policeman, in our 2011 VIFF report. This year he is back with his second, The Kindergarten Teacher (2014).

The film is a psychological study of young woman, Nira, who is an apparently ordinary and devoted kindergarten teacher. She learns that one of her small charges, Yoav, a shy, uncommunicative five-year-old boy, has an odd habit. Occasionally he begins to pace back and forth, declaring “I have a poem” and then reciting a short poem that would do credit to an adult author.

Nira’s reaction to this apparent prodigy is shifting, occasionally ambiguous, and increasingly disturbing. We are confined almost entirely to what she observes and does, so we get no other view of Yoav except when his nanny and father talk with Nira.

Initially she seems inclined to take advantage of Yoav. We witness her reciting one of his poems as her own at a poetry-writing group that she attends. This premise is soon dropped, however, when Nira takes Yoav under her wing. She favors him over his classmates and encouraging his artistic impulses. Eventually she tries to take control of him, clearly picturing herself as gaining reflected glory from being a mentor to a great artist.

Given the limited point of view, we are encouraged to speculate as to how Yoav comes up with his poems and how far Nira will go in crafting the triumphant public career that she clearly wants for the boy. When she discovers that his boorish, business-minded father has no use for poetry, she increasingly tries to control Yoav, taking him to a public poetry-reading and getting him to recite onstage:

Cumulatively the film traces a slow and disturbing path toward her greater obsession. A subtly presented clue suggests the nature of Yoav’s recitations–to us, that is, if we catch it. Nira misses it, or chooses to ignore it.

Once again in Anatolia

Three years ago we wrote about Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s Once upon a Time in Anatolia as one of our favorite films of the 2011 VIFF. Now Ceylan is back with another long film, Winter Sleep (2014), and again it stood out among the films we saw this year.

The film was shot in the Cappadocia region of Anatolia in central Turkey. The area is a major tourist attraction, with caves, “fairy chimneys” and other spectacular stone formations, rock-cut chapels, and structures from antiquity.

The protagonist, Aydin, is an ex-theater actor now retired and running a hotel made up partly of rooms cut into the picturesque rock formations. It’s the winter season, with only a Japanese couple and a motorcycle devotee staying at the hotel, and Aydin has plenty of time to write columns for the local paper and bicker with his young wife Nihal and embittered, recently divorced sister Necla:

This time there is no crime investigation or mystery around which the plot centers. Instead the narrative is a character study, played out partly in long conversations between Aydin and the two women. There are also scenes in which Aydin reacts with indifference to the sufferings of his impoverished tenants.

The early part of the film is given over to Aydin, who at first seem mildly sympathetic, brilliant and creative. But as he converses with Necla in a lengthy central scene in his study, his remorselessly sardonic sister picks apart his flaws in a verbal duel between two equally witty characters. Later, Nihal feels beaten down by Aydin’s opposition to her charitable work, the only activity that gives her satisfaction in this isolated life, and she finishes the job of exposing Aydin’s selfishness.

The program notes compare the film to the plays of Chekhov, and there is a definite similarity, both in the conversations and in the contrasts between the wealthy family and the working-class people who resent being dependent upon them. Despite the fact that much of the film consists of long conversation scenes–and runs for 196 minutes–the large, sold-out audience with whom we watched the film were dead silent, clearly captivated by the story. Unlike Chekhov, in the end the film offers a glimmer of hope for the characters.

Ceylan has said that he shot in the distinctive landscapes of Cappadocia only reluctantly:

I actually didn’t want to use it, but I had to. I originally wanted a very simple, plain place, but the film had to be set in a tourist area, and I needed a hotel that is a little isolated, outside of town. Cappadocia was the only place I could find that in the winter time still had tourists.

I was afraid of shooting in Cappadocia because it might have been too beautiful, too interesting. But I didn’t show it too much, I hope.

Ceylan succeeded, I think. There are enough shots of the rock formations to impress us, but they are used sparingly. One might interpret the landscapes as reflections of the characters’ inner turmoil, in much the way that Maurice Stiller and especially Victor Sjöström used Scandinavian landscapes in their classic films of the 1910s and 1920s. (See top, where Aydin pauses to think near some rocky outcroppings.)

It certainly shows enough that Winter Sleep might cause a rise in tourism among art-cinema audiences. One hotel’s blog has already mentioned the film as a way of luring customers.

Winter Sleep won the Palme d’Or at Cannes this year and will receive an “awards-season” release in the USA by Adopt Films.

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night.

Familiar Middle-Eastern filmmakers return to VIFF

Closed Curtain (2013).

Kristin here:

Two years ago David and I wrote about a group of Iranian and Israeli films that featured prominently in the 2011 VIFF program. This year’s program boasted several more, many of them by the same directors.

Closed Curtain (Jafar Panahi and Kambuzia Partovi, 2013)

Despite still being banned from filmmaking and forbidden to leave Iran, Panahi has followed This is Not a Film with another fascinating feature that has made its way abroad. This time he co-directs with Kambuzia Partovi, who also plays one of the main characters, a screenwriter.

The writer flees to a seaside house (apparently Panahi’s) to hide his dog from a roundup of animals deemed “unclean” under Islam. Once ensconced, the writer tries to conceal his pet by sealing the many large windows with opaque curtains. Eventually their privacy is invaded by another refugee, a young woman sought by local police for participating in a nearby party.

This first section of the film seems to be a straightforward allegory for Panahi’s own situation, but well after the midpoint, Panahi himself appears and takes over as the main character. With the curtains removed, he stares at the pond behind the house, seemingly having a vision of himself amid the beauties of nature. He also gazes at the sea in front of the house, envisioning himself walking into it to commit suicide.

The opening stretches emphasize suspense, when the writer hears voices and sirens outside, and unseen officials hammer against the door. The result is an image of the creative artist forced to conceal himself from forces of authority. With Panahi’s appearance, the film becomes more subjective than allegorical, and the abrupt juxtaposition of the two parts of the film create a puzzling whole. But that whole is rigorously filmed and arouses interest throughout.

Manuscripts Don’t Burn (Mohammad Rasoulof, 2013)

In 2010, I posted about Rasoulof’s beautiful film, The White Meadows (2009), an overtly allegorical film about the sufferings of various sectors of Iranian society. At that point I wrote, “He was arrested alongside Jafar Panahi (who edited The White Meadows) and about a dozen others on March 2. Fortunately he was released fairly soon, on March 17. What his future as a director in Iran is remains to be seen.” Most immediately, he was given a prison sentence and banned from filmmaking. Neither condition evidently kept him from finishing the impressive Goodbye (2011), which I discussed here. More recently, upon returning to Iran from Europe, Rasoulof has had his passport seized and is unable to travel or to reunite with his family. Most observers believe that this treatment is a response to his harshly critical new film, Manuscripts Don’t Burn, which has attracted attention at several festivals.

Manuscripts Don’t Burn differs considerably from The White Meadows. There is no hint of allegory here as Rasoulof examines the state surveillance system.The plot centers around two dissident authors and their strategies for hiding their manuscripts and evading the authorities. While a ruthless, educated young official decides on two authors’ fates, two working-class men carry out the kidnapping, torture, and murders that he orders. The hitmenare seen as victims themselves, as one of them, trying to pay medical bills for a sick child, continually finds that his last job’s payment has not yet been transferred to his bank account. They endure stakeouts in chilly weather and grab takeout food on the fly. The whole film is shot in muted tones (in both Tehran and Hamburg) and conveys a sense of unrelenting grimness.

The plot is drawn from unspecified real-life events, and the film cautiously carries no credits for cast or crew. (For more information on the film’s background, see Stephen Dalton’s informative review from the film’s premiere at Cannes.)

The Past (Asghar Farhadi, 2013)

Since A Separation (2012; see our entry here) became the first Iranian film to win an Oscar for best foreign-language film, Farhadi has become the most prominent director working in that country. This is witnessed by the fact that his new film, The Past, has been put forth as Iran’s candidate for this year’s Academy nomination.

The plot of the new film draws upon familiar strategies that created a strong, moving situation in A Separation. Again a husband and wife are on the brink of divorce. In this case, the husband, Ahmad, is Iranian, and the wife, Marie is French. Clearly they had lived together for a time in France, since when Ahmad arrives from Tehran, he knows how to get around Paris. Marie has two daughters from a previous marriage and plans to marry the small-businessman Samir, by whom she is pregnant. Samir has a morose young son who resists the idea of having Marie as a mother.

With this larger cast of characters, disagreements and obstacles pile up. Marie is extremely strict and strong-willed. Her older daughter is rebellious and stays out late. Ahmad tries to mediate between Samir’s miserable son and Marie’s scolding, while Samir tries to please Marie and still help his son adjust to the upcoming marriage.

As in A Separation, The Past builds up a mystery about an unhappy event. Samir’s wife has attempted suicide. What led her to this desperate measure? Her chronic depression? An embarrassing argument with one of Samir’s customers? Or did she know of Samir’s affair with Marie? Ahmad’s attempts to solve this mystery provide a strong, intriguing subplot alongside the shifting conflicts among the main adult characters.

With so many characters involved, the accumulation of problems and unhappiness eventually threatens to tip over into an exasperating melodrama. But I think Farhadi juggles all these motivations and events so well that we never feel that he has gone too far.

There has been some controversy over the fact that the film was shot entirely in France and therefore has little Iranian about it. Indeed, the Farsi-speaking emigrés who attended the VIFF screening to hear their native language spoken were perhaps disappointed that it was all in French. Yet in an ensemble cast, Ahmad remains the central character, helping to reconcile the others and comfort the three children (as in a rare cheerful moment when he helps the younger ones get a toy out of a tree).

If not quite as satisfying a film overall as A Separation, The Past confirms Farhadi as an Iranian director who can make appealing films for an international audience.

Trapped (Parviz Shahbazi, 2012)

Trapped is probably closer than most Iranian films shown at festivals to the sort of thing seen by popular audiences in its home country. The program notes describe it as a “moral thriller.” It revolves around Nazanin, a studious first-year medical student (see image at bottom) forced through lack of dormitory space to share a flat with party-loving Sahar, who is trying to leave Iran. Sahar has borrowed money to pay for her exit visa and, unable to pay it back, is imprisoned. Nazanin struggles selflessly to help her out, including foolishly signing a promissory note taking on Sahar’s debt and even sharing the threat of imprisonment.

The plot reminded me of the “child quest” tales that were prominent in the golden age of the Iranian cinema of the 1980s and 1990s, such as The Mirror and Where Is My Friend’s Home. (Shahbazi was the assistant director of Panahi’s The White Balloon, as well as conceiving its basic premise.) Here the heroine is distinctly older than the protagonists of those films, but she retains a naivete that makes her seem more childlike than the other characters, who manipulate and ultimately threaten her.

While Trapped doesn’t have the simplicity and charm of those earlier films, it offers an absorbing story. It paints a grim picture of Tehran and gives some insight into the realities of life there. Like many Iranian films, it raises the prospect of emigration, though in this case Nazanin’s strong desire to stay in the country and become a doctor is held up as the better choice.

A Place in Heaven (Yossi Madmony, 2013)

Two years ago I also reported on Madmony’s Restoration. A Place in Heaven is a considerably more ambitious film. It traces the life of a military hero, known only by his wildly inappropriate nickname Bambi, across much of Israeli history. The title derives from a flashback scene early on, when a cook at a military camp praises Bambi’s brave deeds and remarks that he has already earned a place in heaven. A secular Jew, Bambi scoffs at the notion and signs an impromptu contract trading that place to the cook in exchange for a daily spicy omelet.

Although Bambi dotes on his son Nimrod, the boy grows up to become a strictly religious Jew who disapproves of much that his father does. Still, when Bambi is on his deathbed, Nimrod goes in search of the cook to get back the place in heaven. As with Restoration, the plot is largely based around the father-son relationship, though there is also a touching and tragically short relationship between Bambi and his beautiful wife.

Unlike the largely urban Restoration, this film shows off the bleakly beautiful landscapes of Israel’s desert.

There were many other striking and moving films on display at VIFF this year. David and I really can’t do justice to all of them, but in a final post he will consider Koreeda’s Like Father, Like Son, Jia’s A Touch of Sin, Johnnie To’s The Blind Detective, the Godard segment of 3x3D, and Oliveira’s Gebo and the Thief. Like the items I’ve invoked here, each deserves an entry to itself, but time limits and further travels force us to be quick. Still, we hope that you can tell from our entries, VIFF 2013 yielded an extraordinarily high level of quality. As usual!

P.S. 17 October 2013: Thanks to Hamidreza Nassiri for correcting the original entry: Panahi is not, as we had said, under house arrest.

Trapped (2013).