Archive for the 'Hollywood: The business' Category

Catching up

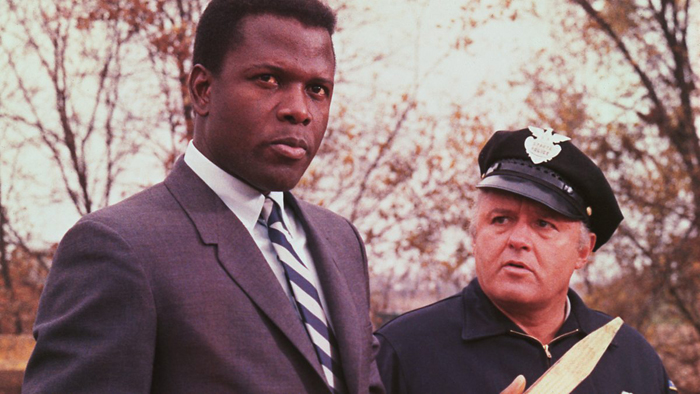

In the Heat of the Night (1967; production still).

DB here:

Some health setbacks have delayed my plans for a new blog entry, but as I clamber back from a bout of pneumonia, I thought I’d signal a couple of things I’ve read and enjoyed recently.

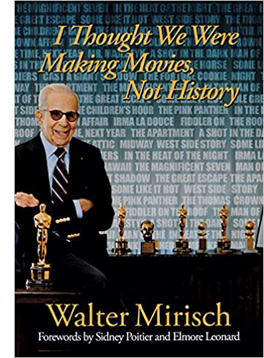

Walter Mirisch’s I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History is a discreet but still informative account of the career of a major producer (In the Heat of the Night, Some Like It Hot, West Side Story, The Magnificent Seven, and many other classics). Apart from offering some vivid vignettes of working with stars, Mirisch (UW grad) is very good on the corporate maneuvering that created, then sideswiped, United Artists. He swam with sharks and survived. Bonus: introduction by Elmore Leonard.

Stylish Academic Writing by Helen Sword is a lively guide to perking up your prose. Unlike most tips-from-the-top manuals, this is based on systematic research that yields some surprises. (Yes, scientific reports are allowed to use personal pronouns. No, literary theory isn’t the most opaque writing on earth: Educational research is.) There’s a lot of good advice here. I wish I’d read it before revising Perplexing Plots.

A shrewd, funny analysis of (a) the current prevalence of mystery stories and (b) streamers’ shotgun programming policies is offered by J. D. Conner in “Going Klear: A Glass Onion Franchise in the Wild” in the Los Angeles Review of Books. This wide-ranging essay ponders franchises, viewer tastes, and other current concerns. Extra points for noticing the Columbo revival.

Way back in 1964, crime reporter Fred Cook caused a stir with The FBI Nobody Knows. After decades of celebrating the agency and its boss (a “confirmed bachelor” not yet revealed as in the closet), Cook’s chronicle of a frighteningly powerful force in the government inspired Rex Stout to write his top-selling Nero Wolfe book, The Doorbell Rang. Cook’s review of FBI history doesn’t out Hoover, and it does praise his ability to disclose WWII spy rings. But it concentrates on how his obsession with persecuting leftists had a long, ugly history. Today, when right-wingers are accusing the agency (staffed mostly with Republicans), it’s salutary to be reminded that the feds were long committed to ruining the lives of “communists” like Martin Luther King and ignoring the real danger of organized crime. Cook is helped by a whistleblower who reports mind-bending tales of peer pressure among agents. A lot of US history is crammed into this exciting, well-documented book.

I hope, when I can type (and think) more fluently, to post a new entry. On, I think, the power of crosscutting. Or maybe Puss in Boots: The Last Wish….

Clyde Tolson and J. Edgar Hoover in 1937. Source: The New Yorker.

P.S. 14 February 2023: In a stroke of serendipity, I learn that Paul Kerr’s new book, a historical-critical study of the Mirisch Company, is coming out next month. Knowing Paul, an expert on American independent production, I’m sure it will be deeply researched and an absorbing read. Congratulations, Paul!

P.S. 25 February 2023: Sad news: Walter Mirisch died yesterday. He was 101. The Variety report is here.

A24: the studio as auteur

Kristin here:

Regular readers of this blog may remember that back in early May I posted an entry trying to answer, at least to my own satisfaction, the question “How did ‘prestige horror’ come about?” As I wrote at the time, the piece wasn’t motivated by any particular interest in the horror genre. Instead it resulted from the confluence of three films considered to be in that category being released during the summer season: The Northman, Men, and Nope, all by interesting directors. That’s when I discovered the phenomenon of prestige horror as a trope among reviewers. I also discovered that the indie producer-distributor A24 has been a major contributor to the small group of films usually mentioned when anyone writes about prestige horror. (For a good summary of A24’s impact on the horror genre, see here.)

Later, having seen A24’s next release, Alex Garland’s Men and quite liked it, I read some uncomprehending and dismissive reviews of it. (These were largely from mainstream critics; horror buffs who wrote about it tended to “get it.”) I decided to analyze this challenging film and posted the result here.

Two days before Men was released on May 20, Variety Intelligence Platform posted an article by Kaare Eriksen, “Can A24 sustain its box office boom?” (This specialty wing of Variety is behind a pay wall; for those who subscribe, find it here.) Everything Everywhere All at Once was already about six weeks into its unexpectedly lucrative run. Eriksen commented of A24, “Its next film, ‘Men,’ which releases nationwide on Friday, may extend this momentum.”

Not surprisingly, Men did not extend that momentum. As Eriksen points out, it was made on a small budget–though how small we don’t know, as I have seen no figures on the cost of the production. Its worldwide gross of a little over $11 million seems unlikely to have made it even slightly profitable. It appeared on streaming services not long after the film went out of theatrical circulation, which was not typical of A24’s approach. Ordinarily they have left a longer window between theatrical and streaming. Men quickly became available as VOD from several services. How much it made in that fashion is unknown.

I wondered how much impact the failure of Men would have on A24’s financial well-being and decided to find out. It turns out, not much. Perhaps the studio’s head will move away from prestige horror a bit, but A24 was never a specialist in horror in the way Blumhouse is. A24’s films have ranged from high-profile Oscar winners like Room and Moonlight to the modest animated feature Marcel the Shell with Shoes on (bottom). It isn’t shying away from more conventional horror films as the recent releases of X, Bodies, Bodies, Bodies, and Pearl show.

[October 31: Will Pearl boost Ti West’s series into the prestige horror category? (The series will become a trilogy with MaXXXine.) As with Ari Astra’s films, Martin Scorsese has again gained A24 attention by describing his reaction to Pearl: “I was enthralled, then disturbed, then so unsettled that I had trouble getting to sleep. But I couldn’t stop watching.” Several news outlets covered his laudatory remarks.]

Festivals and awards

There’s nothing like a premiere at a major film festival or the bestowal of a big award to signal prestige. I mentioned in my prestige-horror piece that A24 had films in that sub-genre premiere at SXSW (Ex Machina, which also won a visual effects Oscar) and Sundance (The Witch). This year the studio took a leap upward with three films premiering at the Venice International Film Festival (above, from A24’s twitter page). Two were in competition: The Whale, by Darren Aronofsky, and The Eternal Daughter, by Joanna Hogg. One premiered out of competition: Pearl, by Ti West, an origin story for and sequel to X (2022).

Festival director Alberto Barbera, asked about blockbuster films at this year’s festival, said: “We had discussions with all the studios. There wasn’t really a blockbuster similar to Joker or Dune, but we still have great presence from the U.S. studios: WB, Sony, Searchlight, Universal, Netflix, Amazon. And for the first time we have two films from A24. I’m really glad we could make it work with them and hope it’s the first of many collaborations.” Barbera is presumably talking about the number of films in competition. Apparently he is anticipating future A24 films on upcoming programs. None of A24’s films won an award at the festival, though one result was that Brendan Fraser has joined the Oscar buzz for a best-actor nomination.

A24’s The Inspection, a film about a gay Black man determined to join the Marines, was chosen as the closing film at the New York Film Festival on October 14.

It has already played at the Toronto Film Festival.

Will A24 feature among the Oscar nominees? “In Hollywood it’s never too early to start thinking about the Oscars,” as Clayton Davis wrote in a July 28, 2022 article, “Award Season Preview: Despite Industry Changes, Winning Oscars Remains Top Studio Priority.” Studio by studio, he comments on their chances for nominations:

There’s already a pair of populist contenders in Paramount’s blockbuster “Top Gun: Maverick” and A24’s metaverse action-dramedy “Everything Everywhere All at Once,” which have cemented themselves in the best picture discussion.[…] With “Everything Everywhere All at Once” becoming the highest-grossing film in the history of independent studio A24, they may have more capital to play with to get Michelle Yeoh an overdue nomination for best actress. They’ll also give a qualifying run to “The Whale” from “Black Swan” (2010) by Oscar-nominated director Darren Aronofsky, said to have the comeback performance of the year from Brendan Fraser. They’re also partnering with Apple Original Films once again for “Causeway,” formerly “Red, White and Water” from Lila Neugebauer and starring Jennifer Lawrence, who also produces.

Having already started lists of predictions for the top Oscar contenders, Davis puts Everything Everywhere All at Once at number 6 for best picture. (Davis includes films yet to premiere, especially at Toronto.) Michelle Yeoh tops his best-actress category.

[November 4, 2022: Variety‘s Cynthia Littleton has this to say in a recent story on The Whale‘s Oscar chances: “A24, which is releasing ‘The Whale’ in theaters, is known for the NYC swagger that befits a top indie distributor.”]

[December 3, 2022 A24’s films won four awards from the New York Film Critics Circle awards, the highest number won by any studio.]

Other signs of continued prestige include a brief weekly series called “Post-Horror Summer Nights” that recently ran at the Barbicon in London. Two of the four films were from A24: The Witch and Hereditary. Also, A24 has picked up the North American distribution for Close, Lukas Ohont’s Grand Prix winner at Cannes this year.

The brand

A24 probably is the most widely recognized indie studio. It has its own devoted fans, many of them in that younger demographic so beloved of movie producers and exhibitors. It works hard to maintain that brand recognition. Naturally it has its own Facebook and twitter pages and is undoubtedly elsewhere on social media sites I ignore. It also has a podcast. It re-designs its logo in eye-catching ways to fit each film, as with the Green Knight opener above.

A24 has its own line of merchandising, selling limited-edition items. Some bear its logo and others relate to specific films.

As the notes in these examples indicate, the majority of items on the shop page are sold out.

Blu-rays of some of their films, often in fancy collectors’ editions, are available. There are soundtracks as well, only on vinyl. A red-vinyl release of the Men soundtrack with a slipcase “featuring six interchangeable covers with watercolors by Julian Gross” (top). It is not shipping until December, so it’s an iffy choice for a Christmas gift. It’s also apparently the only option if you want the soundtrack on physical media; it is otherwise available only for download.

The items are fairly pricey, though I doubt they affect the studio’s bottom line much. Nevertheless, I suspect that they give fans a feeling of connection with A24 and endow it with a quirky aura that fixes it in people’s minds.

Since they are only sold through the studio’s own shop, at least all the income goes to A24 and not to amazon. Theoretically, that is. Someone bought up a batch of the Green Knight vinyl track (green, naturally), which is now sold out on A24’s shop. That entrepreneur is currently selling them through amazon for $99. The soundtracks originally cost $35 from A24. I guess this is another indication of prestige or at least fan devotion among people potentially willing to purchase a copy despite the considerable markup.

The devotion seems genuinely to be there. In a conversation about “The A24 Effect,” Sam Sanders and Nate Jones are discussing the studio’s skill at marketing films and creating a brand through merchandising:

SS: How much of that is the merch? I don’t think I’ve ever experienced a movie studio in which people in my circles are actually excited about the merch. One of my friends yesterday was raving about his A24 fleece. […] What is that?

NJ: That’s a very big part of it. No one’s walking around in a Focus Features hoodie the way that they are in A24 stuff. It goes back to the marketing, the realization that plugging into these downtown fashion circles is another way to cut through the noise. And they do these limited-edition drops that create this sense of exclusivity that mirrors the way that these films are so treated in the cultural conversation.

Sanders calls A24 “the coolest movie studio around.” The “special recipe” they detect consists of three strands: youth culture, horror, and “auteur-prestige cinema,” such as Room, Lady Bird, and Moonlight.

The finances

Despite the unfortunate failure of Men, A24 is doing quite well.

For one thing, on August 1, HBO Max recently added 28 films from A24 to its offerings, mostly films the company only distributed in its early years. Variety predicts that this list will grow as the studio’s deals with Apple+ and Showtime expire.

More importantly, A24 is expanding based on new investments. On September 1, The Economist took note in an article entitled “The Rise and Rise of A24” (behind a pay wall):

The bosses of A24 declined to talk on the record, coyly hoping their output speaks for itself. It has proved persuasive to financiers as well as awards juries. In March the company was valued at $2.5bn as it took in $225m in investment; the lead investor is Stripes, a private-equity firm that helps businesses grow. The funds will let A24 boost its production capacity. It has opened an office in London (and poached two BBC commissioners); it hopes to make films and TV programmes in other territories soon, possibly in foreign languages.

In Erikson’s “Can A24 Sustain Its Box Office Boom?” (linked above), he mentioned “A24’s reported exploration of a $2.5 billion to $3 billion sale last year, with newer streaming entrant Apple apparently interested at one point. This apparently was a result of the pandemic-related slump rather than any underlying vulnerability on A24’s part.

In another symptom of financial health, in October 2021, A24 signed a 15-year lease on four floors of a major new office building at 1245 Broadway. This building was just finished last month. I presume the studio will soon transfer its headquarters from its current modest headquarters, one floor in 31 West 27th Street, to which it moved in 2015 (above). Given the rather bare-bones appearance of the current office, I presume this is a considerable expansion and a more prestigious location. A24 seems confident that it will be around for quite some time.

I am not a fan of the studio itself, only some of the films it has made. Apparently a common accusation leveled against A24 is that it is pretentious, or its films are, or its fans are. But “pretentious” is a word used freely, depending on the tastes of the person using it. Many of the great filmmakers of cinema history are thought of as pretentious by some. The strengths of A24 are that it is surviving in an industry context where films with modest budgets are struggling in the theatrical market and franchise films dominate. In the same “The A24 Effect” podcast linked above, critic Alison Willmore points out that the studio owns no intellectual property that has generated a franchise and that its films are mostly originals or based on fairly obscure literary sources. This helps account for the considerable variety in the types of films A24 releases. It is good to see an indie studio managing to survive and even thrive these days.

Marcell the Shell with Shoes on (2022)

Streaming media: All you can eat, until it eats you

DB here:

In 2013 Spielberg and Lucas declared that “Internet TV is the future of entertainment.” They predicted that theatrical moviegoing would become something like the Broadway stage or a football game. The multiplexes would host spectacular productions at big ticket prices, while all other films would be sent to homes. Lucas remarked: “The question will be: ‘Do you want people to see it, or do you want people to see it on a big screen?’”

I wrote the preceding paragraph two years ago, and the Covid outbreak and enhanced technology have made the split between theatrical distribution and streaming distribution even sharper. (And as the Movie Brats predicted, multiplexes are raising ticket prices.) A crisis point was reached last month when Netflix glumly reported that instead of adding 2.5 million customers as it had expected, it lost some 200,000. Worse, the firm announced a likely loss of 2 million more in the next quarter. The news led Netflix stock to fall by over 30%, wiping out over $45 billion in value.

This stunning decline, coupled with Warner Bros. Discovery’s decision to cut the recently launched CNN+, sent shock waves through the industry. Stock values dropped for Disney, Warners, Paramount, and Roku as well, even though some had strong subscription growth. At the moment, disillusion seems to be settling in. A Wall Street analyst has noted:

We think the industry is facing a point of no return in which the economics of the old models look increasingly frail while the potential of the brave new world now appears overly hyped.

Discussions of mergers, acquisitions, and big company restructuring are ongoing, with layoffs already starting.

As researchers, we at The Blog try to see past current convulsions to larger patterns. But it seems plausible that we are approaching some significant changes. Without trying to predict much, and being no expert on streaming tech, I still thought I’d try to think through some ideas about the state of streaming and its historical significance.

An interim report

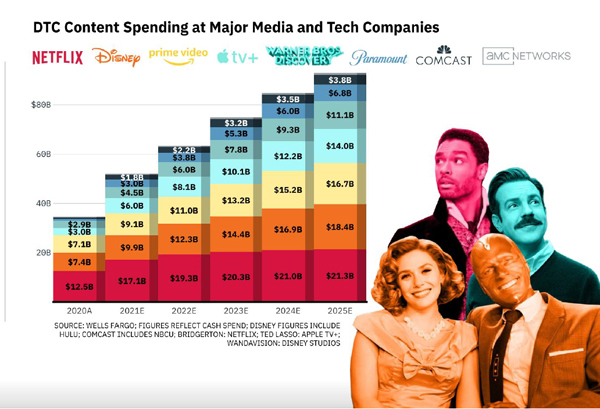

The Future of Content, Variety Intelligence Platform April 2022, p. 10.

Best to start with some basic information. Here’s what I came up with, all subject to correction and nuancing.

Streaming is now firmly established as a distribution/exhibition platform. It’s now the focus of all major US media conglomerates and it’s a market force every independent producer and company must reckon with. Broadcast television is waning. Viewership is declining, and this year saw a ten-year low in the number of pilot shows ordered by the networks. Cable subscriptions are likewise plummeting. Over the last ten years, cable channels lost 30-50% of viewers. Only the Discovery channel managed to grow, and live sports (e.g., ESPN) hung on, though damaged by the pandemic. Globally, streaming is growing rapidly, with both Hollywood majors and national and regional media firms plunging in.

Theatrical film, severely curtailed by the pandemic, is staggering. In nearly every country of the world, 2021 attendance was half or less that of 2017-2019. Studios are now releasing far fewer features, even in the crowded summer months. About 1000 theatre locations have not reopened since early 2020. Los Angeles has lost the Arclight and Pacific Theatres chains and the Landmark Pico theatre. In my home town a five-screen second-run house shuttered during the pandemic, and a six-screen multiplex is rumored to close soon.

As Lucas and Spielberg foresaw, the films that fill multiplexes are blockbuster franchises. So far this year, Spider-Man: No Way Home and Dr. Strange in the Multiverse of Madness have done robust business, and exhibitors confidently expect big turnout for Top Gun: Maverick and Jurassic World Dominion. The surprise success of Everything Everywhere All at Once ($47 million box office) doesn’t mitigate the bleak prospects for most offbeat theatrical fare. Prestige films, romantic comedies, arthouse films, and many genre pictures can’t usually yield big enough returns, and the aftermarket–cable, DVD, and other ancillary outlets–which helped support them in the past scarcely survives.

Which leaves streaming as a primary source of filmed entertainment. At least 86% of US households access streaming services, either by subscription (SVOD) or as ad-supported services. The result is an immense amount of choice. You can browse studio libraries, imports, straight-to-streaming features (e.g., the latest Pixar releases) and series (e.g., Inventing Anna, Tokyo Vice).

Except for Netflix, Amazon Prime, and Apple+, the major streaming services are aligned with US entertainment conglomerates. Indeed, streaming made Netflix and Amazon entertainment behemoths, as attested by recent Academy Awards and Emmys.

Exact figures fluctuate, but the principal subscription streamers vary enormously in scale. At the beginning of this year, pre-meltdown, Netflix declared a global subscription base of about 220 million, with Disney+ at 196 million. Paramount claimed about 56 million (incuding Showtime and other offshoots), Discovery 22 million, and Peacock 24.5 million, including both paid and free. According to Amazon, over 200 million Prime members streamed material in 2021. As of March, Apple+ was estimated to have 25 million paid subscribers, with about twice that number benefiting from access via promotions (e.g., purchase of Apple hardware).

The simultaneous theatrical/streaming release (Dune, Wonder Woman 1984) is becoming rare as audiences return to theatres, but it remains an option (e.g., Firestarter). More common is a strategic delay far less than the usual ninety-day window that was common before the pandemic. The Batman opened in multiplexes on 4 March and was streaming 18 April. Universal and Paramount are prepared to send a feature online 17 days after theatrical release.

Fickle audiences and fluctuating “content” create churn. As a monthly subscription transaction, paid streaming lets consumers depart at will. Canceling cable subscriptions was difficult due to long-term contracts and obstreperous bureaucracy. Unsubscribing to Netflix or Apple+ is a lot easier. In addition, cable programming had a considerable stability, with long seasons and evergreen attractions. Studios signed extensive licenses for films and series, since cable was a perpetual money machine. Moreover, a movie might be available on several cable outlets. Now, however, the streaming industry faces audience churn.

Defections are common, especially among the young. An April survey found that nearly a third of Gen X subscribers and nearly half of Millennial and Gen Z subscribers have both added and dropped at least one streaming service in the last six months. Overall, nearly a third of subscribers say they have canceled at least one service in the same period. Web-experienced viewers are adept at hopping onto and off the latest thing.

Churn is accentuated by the exclusivity of the new media oligopoly. As the majors discovered the money to be made, they regained control of their library licenses. Netflix had The Office, its most popular attraction, until Warners took it back in 2019–soon after Netflix had renewed it for $100 million. The turnover is ongoing: this month Netflix lost Top Gun, the Ninja Turtles, the Muppets, Marvel TV series, and the first six seasons of Downton Abbey. The majors have gradually reasserted the exclusivity of their product.

As competition has intensified, streamers have been forced to acquire their own programming, both films and series. The pool must be refreshed to retain current subscribers and attract new ones. The problem is that once the new material has run its course, viewer loyalty can wane. This is especially true when the streamer dumps a full season of a series for bingeing: it encourages newcomers to sign up briefly and then defect. Disney has executed a powerful balancing act between legacy material and new offerings (Pixar features, Marvel spinoffs) that keep audiences faithful.

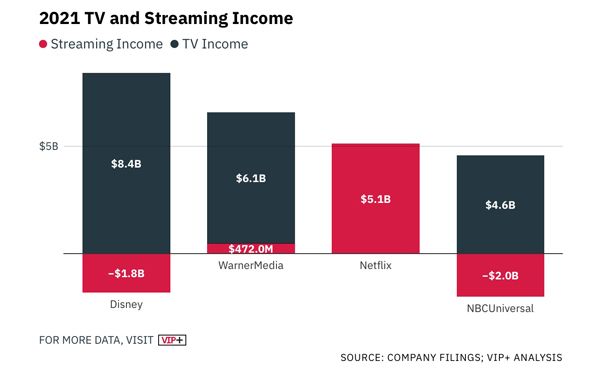

Streaming is not yet profitable. Broadcast and cable television are far more lucrative because they gain revenue from advertising and fees. Disney and Universal each lost about$2 billion on streaming in 2021.

Hence the concern over Netflix’s April report of decline in subscriptions. Streaming is its core business. A loss of $2 billion for the Disney conglomerate (parks, cruises, ABC TV, etc.) amounts to a rounding error. The majors’ deep pockets can sustain streaming enterprises for some time, but Netflix is far more vulnerable.

The streaming services are investing huge amounts in new “content.” The major providers are estimated to spend $50 billion acquiring projects this year. Producers are in a powerful position to demand big budgets to outmatch the competition. The costs are exacerbated by the high demands of talent, who now expect to be paid largely up front, since there is little opportunity for the deferred fees and back-end deals that depend on ancillary revenue.

No wonder then that several services have raised subscription rates. More drastically, in its current crisis Netflix has announced plans to offer an ad-supported tier of the sort already provided by Universal/NBC’s Peacock. Other services, Disney included, will probably shift to a similar option, especially since there is some evidence indicating that consumers will accept commercial interruptions in exchange for lower fees. Netflix also plans to control password-sharing, which helped it grow recognition but in the face of intense competition depletes its audience. It may be harder to combat the use of virtual private networks, aka VPNs, which allow roundabout access to region-based offerings.

One monetization strategy seems to be the rebirth of windows. Once a high-demand film is released to streaming, the service can add an upcharge for accessing it. Blockbusters like The Batman and the new Spider-Man trilogy were launched online with an extra fee for initial viewing. Over time, the prices fell gradually, just as in the old first-run/ second-run days. Even classics can benefit from premium treatment: The Godfather is free on Paramount+, but a rental costs $3.99 on Amazon Prime and Apple+. Arthouse fare is even more privileged; I paid $19.99 to see Drive My Car in its online release, though now it’s free on HBO Max.

It’s still TV

Bill Amend, Foxtrot.

In the late 2000s, streaming video entertainment was the province of mostly smallish, scattered companies like Twitch, Pluto, and others. Netflix and YouTube also took the plunge. Hulu, a consortium of Fox, Universal, and Disney, represented the majors’ initial effort to explore the market. As download speeds improved, problems with buffering and latency were overcome by new streaming protocols.

Soon enough, a familiar cycle emerged. Tim Wu’s book The Master Switch shows that mass information technologies (telegraph, telephone, film, TV) tend to consolidate into oligopolies. Major companies buy or kill off the competition. This happened with streaming, as one by one the big players came to the foreground. Netflix had early-mover’s advantage, having pioneered the distribution of DVDs by mail, and Amazon had a massive customer base in place already. The studios had helped Blockbuster wipe out small video-store chains, which had demonstrated the existence of a massive market, then turned their attention to selling discs directly to consumers. In 2019 the big players began to consolidate control over the expanding streaming landscape.

By acquiring other services (e.g., Paramount’s buying Pluto) and assembling proprietary components already in hand (e.g., WarnerMedia’s repurposing HBO Go), the firms have come up with integrated platforms. Disney+ launched in 2019, Peacock and HBO Max in 2020. Discovery+ and Paramount+ appeared in 2021, and Amazon bought MGM earlier this year. Sony, while licensing its film releases to its counterparts, has focused on animation by picking up Crunchyroll, which will absorb Sony’s Funimation service.

It’s early in the game, and it will take time for the companies to reassemble libraries that have licenses yet to expire. Doubtless many titles will be available for premium rental on rival sites, since no company wants to leave money on the table. Still, it seems clear that a considerable siloing of “content” will enable firms to enhance their power over their intellectual property. From this standpoint, we can think of streaming as a new phase in the development of home video.

In the earlier entry, I argued that home video formats gave the consumer a great deal of freedom. Even cable promoted “appointment viewing,” but tape, and then DVD, allowed the consumer a lot of flexibility. You could buy or rent a movie and watch it when you pleased. You could copy it too. Convenience is always a plus in a consumer item, and home video added to it a welcome price point: renting a tape or disc was cheaper than buying a movie admission, and in discount bins you could find a DVD for a few bucks.

With physical media, movies became manipulable by the audience. Ripping a DVD yielded a file that could be remade. Mashups, Gifs, and other transformations were feasible. Video essays changed film studies, and satire, homages, and fan analyses filled the internet. You could play with your movies.

Streaming withdrew this flexibility but offered greater convenience. A platform combines the array of a video store (think of those tiled pages as display racks) with push-button access. You still have the option of time-shifting, and you can share home viewing with others. But there’s no longer a physical medium. You don’t own or rent the film as object; you have bought access to it as a display, and only when you’re online. (“Buying” a digital copy is no guarantee of possession, if the service loses its license to the title.)

For decades, movie exhibition was a service business. We paid for the experience. Briefly, between 1980 and 2020, films became consumer artifacts as well. Ordinary folk enjoyed the sense of possession shared by film collectors of earlier decades. But with the decline of discs, we are once more paying for the experience while the object lies elsewhere.

Because of Hollywood’s preternatural fear of piracy, turning the artifact back into a service is a way to secure intellectual property. Not that people will stop trying to make personal copies. It’s possible to record streaming transmission, but the majors are counting on several factors. Just as people became tired of piling up DVDs they probably won’t watch, they could tire of filling hard drives with rips.

A few hardcore headbangers will enjoy sticking it to the man, but most people will reckon if you already pay for streaming the movie, why copy it? Given customer inertia and the convenience of streaming, why bother to pirate a movie that’s probably on streaming somewhere, available whenever you want? The trouble and expense of ripping may be greater than simply signing up for another subscription service. There are certainly overseas markets for pirated streaming shows, but as the companies expand their platforms abroad, piracy may diminish.

In sum, streaming has become the next step in the majors’ reassertion of control over their IP. It surpasses the old video store’s inventory, offers the convenience of click-ordering and time-shifting, and retains the advantages of in-home consumption. All we relinquish is ownership of a copy. Now that SVOD services are generating new attractions, providing long-running series with spaced-out hour-long episodes, and exploiting advertising-supported tiers, we are getting a version of fully on-demand cable TV.

We can glimpse this prospect in the demand for bundling, or aggregation. Customers’ biggest complaint is that there’s too much choice. The 200 channels of maximal cable are dwarfed by the streaming torrent. Nielsen estimates that as of last February there were 817,000 unique program titles available. Hence the emergence of streaming MVPDs, the “multichannel video programming distributors.” They provide a mix of movies, broadcast network series, classic TV, sports, and cable news. The best example is YouTube Live, which charges $64.99 per month, far beyond most of its SVOD competitors and reminiscent of classic cable fees. Yet YouTube Live is the most popular MVPD.

Add to this the number of FAST outlets, free ad-supported streamers such as Pluto, Tubi, Roku, Freevee, et al. With MVPDs these already constitute about a third of streaming offerings. One survey found that 34% of US consumers would prefer a free streaming service with 12 minutes of ads per hour. Streaming is starting to look like. . . well, just good old TV. The free platforms approximate broadcast TV, and the paid ones are cable reborn.

It takes time to make a classic

Atom Egoyan, Artaud Double Bill (2007).

Streaming demands a constant flow of new material, compared with the relative stability of broadcast TV, so the problem has been how to release it all. Netflix made a splash by dumping entire seasons at once, encouraging bingeing and getting immediate buzz and uptake. Viewers came to expect the big gulp. One survey found that over half of viewers under sixty now want firms to provide all the episodes of a series at once. But this strategy can damage long-term subscriptions by encouraging churn.

It also makes the product forgettable. Most direct-to-streaming films have a short shelf life. Does anybody watch War Machine (2017) or Bird Box (2018) now? Most auteur efforts seem to me to have had little cultural impact, not even Scorsese’s The Irishman (2019, with a mild theatrical release as well) or Soderbergh’s The Laundromat (2019). They came and went fairly quickly. A rolled-out theatrical film had an afterlife, it could circulate through the culture in many ways, and it could find niche audiences. Could The Godfather (1972) have its standing today if it were released straight to SVOD? Are there now “classic” streaming features?

This applies to art films too, I suspect. The international festival circuit allowed films to trickle from the big events to national and regional festivals over months, so outstanding films could build critical response and whet audience interest. Eventually some would find commercial distribution city by city. The pandemic compressed that process as festivals began to allow remote viewing of their screened titles, sometimes to audiences outside the locality. Kino Lorber’s Kino Marquee plan, which allowed simultaneous online access to new releases across the country, was a creative effort to maximize a film’s reach. Sponsored by local theatres, the plan in effect yielded a quick nationwide release on a scale that couldn’t easily be matched in pre-Covid days. It’s hard to imagine, though, that L’Avventura (1960) would have its standing today if it had played so quickly throughout the country.

Producers are belatedly realizing that the slow rollout characteristic of classic film distribution had the advantage of building audience awareness. A theatrical trailer is targeted toward habitual moviegoers and word of mouth. Theatrical releases garner promotion and extensive critical coverage that last longer than a Twitter alert. Theatrical screening can make a film an event–not always successfully, but at least it offers a chance. At a 19 May Cannes panel, a Swiss distributor pointed out that theatrical releases do better on streaming than straight-to-streaming ones.

The rationale is partly financial, of course. Here is the new head of Warner Bros. Discovery David Zaslav:

When you open a movie in the theaters, it has a whole stream of monetization. But more importantly, it’s marketed and builds a brand. And so when it does go to a streaming service, there is a view that that has a higher quality that benefits the streaming service.

There’s also the fact that a film on the big screen has a force that even a home theatre display can’t match. Another executive notes: “The undivided attention you get from an audience in a theater is where franchises are born.”

Classics, too. Even if most people see most films on monitors and personal screens, there need to be places for the proper display of them–living museums of cinema, in archives and cinémathèques but also in multiplexes and art houses. If streaming is making films ephemeral, we need to hang on to screening situations that let films claim our full engagement. If cinema becomes more like opera, as Lucas and Spielberg prophesied, let’s all become patrons and devotees, even snobs. Let films ripen over the years in a shared cultural space. Then we may get future masterpieces. Or so we might hope.

Thanks to Erik Gunneson, Peter Sengstock, and Jeff Smith for information and ideas.

Hunting Deplorables, gathering themes

The Hunt (2020).

DB here:

I recently participated in a Film Comment podcast with Nic Rapold and Imogen Sarah Smith. It was fun. Yes, The Hunt was involved.

And last month I posted a “blog lecture” for my seminar on Poetics of Cinema. Because it included references to classroom material, I thought it was too insular for general consumption, so I posted it privately. Encouragingly, some of our regular readers wrote to ask about accessing it, so today I’m putting up a more broadly-aimed version. Again, yes, The Hunt is involved.

We like to watch (and listen)

First and fast, some foundations. As Paul Krugman might say, wonkish ones.

Most basically, I’m interested in two questions: How do films work? How do they work on us? The first question, I think, can productively start with filmmaking craft and the norms that filmmakers work with in their historical situation. Within and against those norms, filmmakers create work that blends tradition and innovation. I’m interested in conventions–the conventional side of “unconventional” works, and the unconventional side of more apparently rule-abiding ones. I sometimes say I want to know filmmakers’ secrets, even the secrets they don’t know they know.

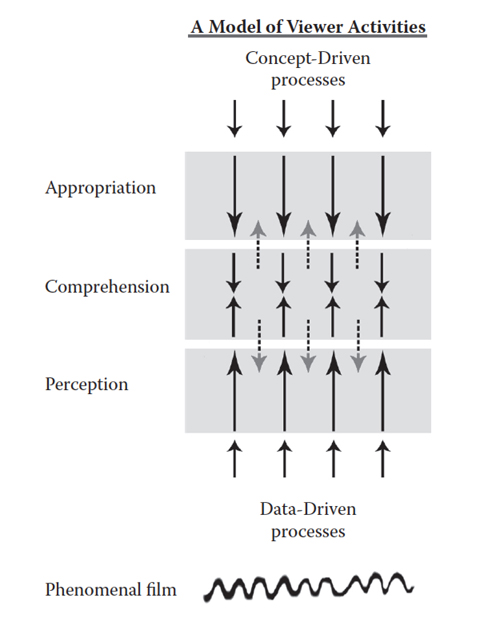

But asking how films work on us has driven me to posit a conception of spectators’ activities. After all, in any art it’s legitimate to try to explain how the design features of a work are shaped to elicit effects, ranging from perceptual and emotional ones to broader effects of comprehension and what I call appropriation. I assume that in every sphere “the beholder’s share” in watching movies is considerable, and active.

Using a common psychological distinction, I’ve argued we can roughly understand this process with a diagram, above.

The activity proceeds both “from the bottom up” via the fast, mandatory, specialized activities of visual and auditory perception. The process works as well as from the “top down” via more deliberative mental acts. Comprehension, typically of story patterns, operates in the middle. So you “just see” a man in tights walking across the shot. Thanks to story comprehension skills you “just see” Batman striding to face off against a crook. Thanks to your wider conceptual schemes, you can appropriate that as patriarchy in action, or the pain of vigilante justice, or a template for an action figure you might buy, or whatever. Where’s emotion? At all stages, I think.

And all these processes seem to me inference-based to some degree. In grasping artworks, even perception has an inferential dimension, going beyond the information given. Patches and contours on the screen are grasped as people, places, and things; sound waves are grasped as speech and music. The process is inferential because these perceptual conclusions are defeasible, as most illusions are. Things might be otherwise than they seem; we bet (fast, unreflectingly) that things are as they seem until other information pulls us up short. Similarly, story comprehension relies on skills of inference we’ve developed since childhood, built partly upon our social intelligence. And appropriation is obviously inferential, building hypotheses about the meanings and uses we can ascribe to film.

Perception and comprehension are strongly shaped by the film’s form and style. But as we go up from perception, the filmmaker’s power decreases and the viewer’s power increases. Viewers wield most power in appropriation, those top-down, concept-driven inferences that pull the film, or at least the viewer’s construct of the film, into wider projects.

Let’s think of appropriation as most basically using the film for myriad personal or social ends. That activity involves, for want of a better term, themes–ideas, categories, dualities, pop-culture memes, right up to wider beliefs about the world. Cultural processes, affecting the lower levels to some degree, are at work here most explicitly.

At this moment, when many people are sheltering at home, they are appropriating films for many purposes–to distract them, to entertain the kids, to learn more about health policy or the effects of pandemics. Fans, I assume, are seizing the pretext to binge on a saga they love, or check out a series they’ve put off. Online critics, pressed to turn in copy, are mustering their new listicles, recommendations of films to watch while we’re in lockdown.

This situation is just a special case of appropriation, of finding aspects of the film that can be recruited for purposes that may or may not accord with the filmmakers’ original intentions. No producer planned for Outbreak (1995) or Contagion (2011) to serve as audiovisual aids during a plague.

As my Batman example indicates, interpretation is a rich instance of appropriation, displaying how resourceful people can be in their inferential elaborations.

I wrote the book Making Meaning: Inference and Rhetoric in the Interpretation of Cinema (1989) as an attempt to spell out my ideas. I concentrated on two critical institutions, journalistic criticism and academic interpretation. But I think my claims could be applied to “amateur” critics and fandoms too. (This blog entry on Room 237 gestures in these directions.) Another article on this site, “Film Interpretation Revisited,” is a summary of the book, as well as a reply to critics.

So much for “the beholder’s share.” Can we go back to the “maker”? In a later section I’ll float some ideas about the place of thematics in relation to form and style. I’ll also consider how artists can anticipate and manipulate the appropriation process–a sort of meta-strategy to grab control higher up the chain.

Yes, spoilers for The Hunt are involved.

Interpretation, whys and wherefores

Interpretation seems to me to involve two tasks. First, there’s problem-solving: How should I interpret this film (or show, or whatever?) Second, there’s argument, or rhetoric: How should I make the case that this interpretation is worthwhile? Making Meaning has a lot to say about critical rhetoric, but I’ll concentrate on the problems interpreters set themselves.

I assume that interpretation ascribes meanings to films. What sorts? I start with referential meanings (a big category including building the story world as well as tapping into real-world information, like specific times and places). In The Hunt, recurring TV images of polar bears struggling on melting ice floes nudge us to remember the climate crisis.

There’s an extra referential layer in the chyron, which expresses Fox-News style skepticism about climate change. That line helps confirm the right-wing ideology that supposedly permeates the quickee mart.

The other sorts of meaning I identify are more abstract. They include explicit meaning, usually given in language. In The Hunt, Athena expresses her disdain for the Deplorables whom she has gathered her friends to kill. She articulates a part of the film’s explicit meaning: The elite treat their social inferiors as prey.

There’s also implicit meaning, suggested through many cues, not just verbal ones. Crystal, the fierce fighter who confronts Athena at the end, is too laconic to speechify, and she never asserts that the underclass can be resilient and pitiless. But we are to grasp that meaning through her behavior–as the prey fighting the predator. Story comprehension feeds our interpretive move. By the end of the film we may take the polar-bear footage as implying that the Politically Correct hunters care more for these beasts than their vulnerable fellow humans.

Referential meaning, explicit meaning, and implicit meaning are typically under the control of the filmmakers. Clearly Craig Zobel, Damon Lindelof, Nick Cuse, and their colleagues want us to make the inferences I just made, along with many others. But it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that some implicit meanings escape the filmmakers. I’ll try to show later that filmmakers sometimes try to back up and frame their films to cover those unintended implications.

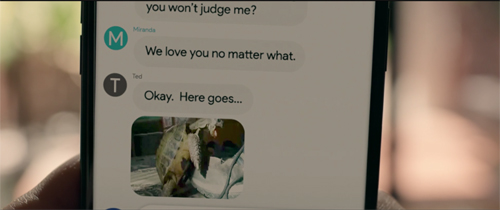

We can argue about some of these meanings. In The Hunt, Crystal recalls a childhood story of a race between a rabbit and a turtle. The rabbit lost through laziness, but he took revenge on the turtle by killing him and his family. The tale becomes part of a motif: Early in the film we see a video of a turtle humping a boot, while at the end we see a bunny hop into a gory kitchen.

After telling the story, Crystal declares she’s not sure whether she’s the rabbit or the turtle in the hunt. I think we’re supposed to think about whether the underclass (if it’s the turtle) can ever win more than a temporary victory. This sort of equivocation about implicit meaning is common in artworks. Indeed, the clash of implications encourages us to interpret them. The tactic might seem designed only for “difficult” films, but it’s surprisingly frequent in mainstream movies, as I’ll suggest later.

A fourth sort of meaning, I think, is what people have come to call symptomatic meaning. Here the film says more than it intends. It reveals, like a psychoanalytical symptom, an “unconscious” problem with the explicit and implicit dimensions put forth. (This is the “hermeneutics of suspicion,” which Susan Sontag discusses in “Against Interpretation” in relation to Marx and Freud.)

Critics may say that cheerful Eisenhower-era comedies betray anxieties about gender and identity. Some consider superhero franchises as unwittingly betraying a commitment to fascistic authority. From this perspective, Indiana Jones is less an adventurer than an imperialist. Symptomatic meanings leak out and can’t be contained. If implicit meaning is the filmmaker being more or less subtle, symptomatic meaning works behind the filmmaker’s back.

The Hunt is of course ripe for symptomatic interpretation, as I’ll mention below. However much its sympathies may seem to lie with the prey, it seems unable to avoid double-edged gags at their expense.

For all of these types of meaning, the process I posit is the same. The viewer maps, from the top down, concepts onto cues and patterns found in the film. Given the results of perception and comprehension, the viewer selects certain items to bear the meanings we bring to the task.

For example, I said that Athena articulates the predatory view of the oligarchy. Why did I pay attention to her and her words rather than, say, the layout of comestibles on the kitchen island? Because I have a rough but well-practiced mental schema for personhood. That’s more salient in building up a narrative than spotting bits and pieces of scenery. (These details can become salient, as the cheese-slicer will eventually, but the filmmaker has to make them so, as hand props or in close-ups or whatever.)

Making movies mean (but not like Zahler does)

The information in a film is most simply a flow of images and sounds. Perceptually I go beyond that information to recognize a person. Given that my person schema is furnished with properties like beliefs, desires, consciousness, and so on, I can build up a sense that Athena is stating her views on late capitalism.

Similarly, my repertoire of person schemas enables me to build up a sense of Crystal’s character, based on her appearance, speech, and actions. She too has beliefs (she’s being hunted), desires (she wants to survive), plans (she will fight), and attitudes (she scorns the sissified elites). She has character traits. In certain relevant respects, she’s like us and the people we know.

Filmmakers are practical psychologists. They know, from having consumed films as well as made them, how to highlight information and make it vivid and salient, so that we’ll lock in our concepts easily. For lots of reasons, we’re interested in other people, so that gives film artists an immediate purchase on using characters and their actions to convey abstract or general meanings.

For symptomatic interpretation, the same process holds. Character recognition and construction will be important for finding the flaws and failings of the film’s primary meanings. Of course, the symptomatic critic may “read against the grain” and look for less salient items that betray the film’s unconscious meanings. The fact that the climactic confrontation takes place in a kitchen could suggest that the filmmakers, for all their flaunting of strong women, are assuming a patriarchal ideology: Woman’s place, even as a killer, is in the home.

And the very end of the film, with Crystal strutting out as a fashionista, suggests that she has bought into the shallow values of the elite.

She’s not leading a revolution but killing her way to upward mobility.

I emphasize character as a site of interpretive elaboration because it’s so central to all critical schools, from fandom and journalism to the upper reaches of Academe. It’s not the only set of cues that get mobilized, though. Small details dropped in can serve too. A jar of Pickled Pigs Lips in a fake quickee mart reveals the sneering disdain of the hunters who’ve set up the display, but some viewers may find that it nudges us to mock trailer-trash taste.

The glimpse we get of the jars before the camera pans away seems to be the sort of cue aimed at “committed viewers,” willing to freeze the frame in playback to look for touches like this.

In Making Meaning, I talk about structural patterns as well, like journeys and character relationships, which prompt us to assign interpretations. There are stylistic cues too–not just the soundtrack with its dialogue and not just written language, but also camera movements, cutting, lighting, and so on. All these can be recruited to bear meanings. Critics often interpret a low angle as conferring power on a figure. Style, at bottom aimed at guiding attention and creating emphasis through the line of least resistance, can sometimes come forward and fill less concrete and fundamental functions–that of suggesting implicit or symptomatic meanings.

To wax wonkish again, Making Meaning suggests that the abstract meanings critics map onto cues are organized as semantic fields,which are in turn processed by assumptions and hypotheses. All that machinery is put into motion through schemas (prototypes and mental models) and heuristics (short-cut reasoning routines provided by social milieu or personal proclivity). The result is a “model film,” the film as interpreted by the critic.

You need lose no sleep over these matters. I simply argue that interpretation is a rational, fairly systematic process of informal reasoning operating within institutions that reward certain activities. Academics reward novel “readings,” while arts journalism does less elaborate versions as well. Even the “male gaze,” though stripped of its Lacanian baggage, has found its way into mainstream criticism (and the film industry).

Themes are memes, sometimes

“Themes come cheap,” I said one night in the seminar, rather flippantly. “They’re practically free.”

What I was suggesting was that themes are often obvious in a way style and overall form aren’t. They rise out at us unbidden. Before people watched The Hunt, they had been alerted to look for certain meanings. Mass media, critics, and the filmmakers had primed us to catch the big ideas the film was laying out.

That’s because films take meanings not only as effects but also materials. Films are made out of images and sounds, but they’re organized through form and style . . . and themes. If we look at it from the filmmaker’s standpoint, themes (like subject matter) can be treated as stuff to be worked on through technique. Like subject matter, they can float “obviously” on the surface, protruding a bit but still tugged by the flow of form and style.

In the Poetics Aristotle posited the category of “thought” as a component of tragedy. This term appears to mean something rather special. “Thought” isn’t what characters in drama think, or even what the playwright thinks. Rather, it’s what the characters say: their efforts to crystallize ideas and feelings in statements. The functions of thought in this sense “are demonstration, refutation, the arousal of emotions such as pity, fear, anger, and such like, and arguing for the importance or unimportance of things.”

The plot, Aristotle says, must create its effects through events and their patterning, “but these must appear without explicit statement, whereas in the spoken language it is the speaker and his words which produce the effect.” Thought in Ari’s sense spells out what action leaves tacit.

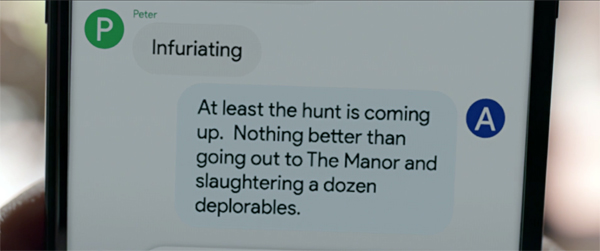

The Hunt does both. Ideas, images, and stereotypes circulating in US society have been taken by the filmmakers as already-fairly-processed material to be reworked into images and sounds and story. The explicit and implicit meanings critics build out from the film are the result of form and style shaping all this stuff into a perceptible, comprehensible experience. At moments, though, the oligarchs and the Deplorables state their sociopolitical views pretty frankly, as in the text message above. As Ari puts it, “they argue for the importance and unimportance of things.” Thought-as-theme is a prime cue for interpretation.

Themes can become not only material but also pattern. Certain genres of narrative are heavily “thematized” in that their organization is based on explicit or implicit meanings. Allegory is a classic instance. The Pilgrim’s Progress has a thematic armature, crystallized in the journey of Pilgrim to the Heavenly City. Ditto Animal Farm, which is usually taken as an allegory of the Russian Revolution. (Interestingly, The Hunt cites Animal Farm.) I expect that right now some grad students are writing papers about The Hunt as an allegory of working-class resistance.

Other heavily thematic genres are parables, fables, and the like. Crystal’s childhood story of the rabbit and the turtle becomes a parable of social injustice.

There are lots of ways that themes provide formal architecture. Some early films, like One Is Business, the Other Crime (1912), depend on thematic contrast. Here the fate of a poor man forced into thievery is juxtaposed with the law’s ignoral of a rich man’s transgressions. (Class resentment didn’t start with The Hunt.) Griffith’s Intolerance (1916) tries for a four-way thematic comparison/contrast of prejudice through the ages.

We also have “social cross-section” films, where stages of the narrative enact encounters with various institutions. As critics have noted, in The Bicycle Thieves(1948), Ricci’s search for his stolen bike brings him into contact with the labor union, the government, the church, and the bourgeoisie–none of whom are of help. A similar cross-sectional dynamic suggests social critique in Mizoguchi’s Life of Oharu (1952) and Fellini’s La Dolce Vita (1960).

Granted, in such modes, the film’s thematic skeleton can seem obvious. Other films leave meaning more free-floating, and even allegories can be less clear-cut than they may seem. (Think of Kafka.) I just want to signal, for the sake of comprehensive coverage, that filmmakers, like other artists, draw upon abstract ideas and meanings as materials to be reworked by their art.

To be good critics, we ought to be aware of both the materials and the transformations that come from them. I suggest this in a piece I’ve flagged before, “Zip. Zero. Zeitgeist.”

The filmmakers fight the power (of viewers)

The filmmaker’s power wanes as we move toward appropriation. But not completely. Filmmakers can use themes to manage a film’s reception.

For example, the Russian Formalist literary theorists floated the idea of the “biographical legend.” This is a public version of the artist’s life that can guide interpretations of the work. Boris Eichenbaum suggested that the Americans had one biographical legend for O. Henry, but the Russians built up a different one.

Critics and commentators build up the biographical legend in order to support interpretations, but the artist can contribute to the process. When Christopher Nolan tells us that as a youth he loved Star Wars, noir movies, and experimental fiction, he’s inviting us to put his own “intellectual blockbusters” in a certain perspective. He’s flagging certain cues, inviting certain mental sets, coaxing us toward certain inferences.

It’s not news. Contemporary critics took Douglas Sirk’s 1950s melodramas as glossy reflections of the superficial values of Eisenhower America. But when he was interviewed by Jon Halliday, he presented himself as offering a Brechtian critique of those values. Later critics eagerly started scanning the films for narrative and stylistic cues that suggested implicit meanings that subverted the suburban bourgeoisie. Chabrol, typically jaundiced, put it this way:

I need a degree of critical support for my films to succeed: without that they can fall flat on their faces. So, what do you have to do? You have to help the critics with their notices, right? So, I give them a hand. “Try with Eliot and see if you find me there.” Or “How do you fancy Racine?” I give them some little things to grasp at. In Le Boucher I stuck Balzac there in the middle, and they threw themselves on it like poverty upon the world. It’s not good to leave them staring at a blank sheet of paper, not knowing how to begin. . . . “This film is definitely Balzacian,” and there you are; after that they can go on to say whatever they want.

If critics can use the artist to interpret the film, why can’t the artist use the critics to steer us toward preferred interpretations?

It isn’t just the filmmaker doing this. Auteur personas created by the filmmaker, the industry, and critical discourse can be seen as pushing us toward certain thematic interpretations.

Now to finish with a point I suggested above. It’s often in a filmmaker’s interest to avoid consistent and clear presentation of themes. I’ve come to think that many ambitious Hollywood films are systematically ambivalent about what they are “saying.” Rather than make a weighted, compact statement of “thought” in Ari’s sense, they scuttle and shuttle between alternate thematic possibilities. Or rather, they shuffle several disparate “thought” statements to counterbalance one another.

This has many benefits. It can stoke controversies. Is The Dark Knight in favor of vigilantism, or does it celebrate anarchy, or does it hold out hope of noble self-sacrifice? Nolan says:

We throw a lot of things against the wall to see if it sticks. We put a lot of interesting questions in the air, but that’s simply a backdrop for the story. . . . We’re going to get wildly different interpretations of what the film is supporting and not supporting, but it’s not doing any of those things. It’s just telling a story.

Another benefit: If someone objects to one piece of thematic material, you can always say, “But look, we offset that with this…” It’s a way of widening the film’s appeal to many lines of thinking, while marketing the film as complex.

The creators of The Hunt claim to have aimed the film at smugly woke people like themselves in an effort to humanize the Other.

So we heightened the reality as much as we could. Some of the people who are being hunted are literally the guy with the tiki torch or a guy posing next to a dead animal; they’re two-dimensional stereotypical representations of what liberals see conservatives as. And then we had to do the same thing with the liberals. But there had to be one character in the movie, the hero who defied the conventions of stereotyping, who when you look at her you basically say, “Oh, she has an accent like this. She wears clothes like this. This is who she is.” And let’s be wrong about her. Let’s let the movie be about the cautionary tale of, here’s what happens when you get it wrong.

I think that the idea the audience wants Athena to be wrong about Crystal is maybe our own interior desire to say, “Maybe I’m wrong about my uncle who I’m screaming at at Thanksgiving. Maybe there’s a little bit more to him than meets the eye. Maybe I’m trying to put him in this specific lane because we have to choose a side, but maybe there’s many sides and there’s a little bit more nuance in the conversation.”

The caricaturing of the woke characters allows woke viewers to recognize the satire (and since woke viewers are likely to be educated, they know that satire exaggerates). Presentation of the Deplorables is exaggerated too, confirming that “There’s many sides.”

But there’s a kink for a symptomatic reading: Crystal may not be an actual Deplorable. We never learn her politics. She has been kidnapped in error, mistaken for a fierce Trumpist with the same name. So again the film manages to have it many ways. “Getting it wrong” here doesn’t mean disparaging a right-winger but rather not knowing whether somebody is right-wing or not. The real conversation is postponed because of a mistake. (No mistakes, no stories.)

I don’t mean to sound cynical about this. Art is opportunistic. We just ought to be aware that filmmakers can make the meta-move, using whatever means they can to close off interpretations that they might not prefer. Ultimately, since appropriation is top-down, they can’t control everything we might ascribe to the film. (See Room 237 again.) But there is a bit of a struggle there. Filmmakers will always try to join and constrain the hunt for meaning in their movies.

There’s a lot more to be said about interpretation, but I hope that readers will find something worth considering here. I may redo other Private seminar entries as public ones when time permits.

Thanks to Nic Rapold of Film Comment and Imogen Sarah Smith for a pleasant discussion. My citation of Aristotle on “thought” is from Stephen Halliwell, The Poetics of Aristotle: Translation and Commentary (Chapel Hill, 1987), 53. The reinterpretation of Sirk’s melodramas was undertaken in Jon Halliday’s interview book Sirk on Sirk (Secker and Warburg, 1971). The Chabrol quote is from Making Meaning (Harvard University Press, 1989), 210.

Phoenix (2014), one of the Christian Petzold films discussed in the Film Comment “At Home” podcast.