Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

Welcoming Jews as heroes in an alternate 1924 Vienna

The City without Jews (1924).

Kristin here:

Once again Flicker Alley has released a restoration of a film that few have ever heard of. But we all should have heard about this one. And we should have wanted to see it. Now we can.

The City without Jews (Die Stadt ohne Juden) is an Austrian silent film released in 1924 and directed by H. K. Breslauer. It falls into the brief cycle of films about Jews released in the first half of the 1920s. I’ve written about this briefly in regard to Flicker Alley’s earlier Blu-ray of another film in this cycle, E. A. Dupont’s Das alte Gesetz (1923). The other notable Jewish-themed films are the Expressionist classic Der Golem: Wie er in der Welt kam (Paul Wegener and Carl Boese, 1920) and Carl Dreyer’s first German film, Die Gezeichneten (“The Stigmatized Ones,” called in Danish Elsker hverandre, or “Love One Another,” 1922). Thus The City without Jews is, as far as I know, the last entry in this cycle.

The Russian Revolution and civil war had driven many “Eastern Jews” into Europe, and they, created an anti-immigrant sentiment that grew into a more generalized intolerance toward the more assimilated Jews already in these countries. The earlier films had made little reference to the current growth of antisemitism in Europe and particularly in Germany and Austria. Der Golem was a period fantasy, Dreyer’s film dealt with pogroms in 1905 Russia, and Das alte Gesetz was a drama largely about conservative attitudes toward assimilation within the Jewish community.

Beslauer’s film was based on a satirical novel of the same name (1922) by Hugo Bettauer. It has proven his most famous novel, though undoubtedly in film circles he is best known as the author of Der freudlose Gasse, the source for G. W. Pabst’s 1925 classic of New Objectivity. Bettauer was a controversial figure, given the rising right-wing extremism in the mid-1920s. Perhaps spurred by the release of the film, a dental technician and member of the National Socialist Party assassinated Bettauer in early 1925; the assassin was sentenced to 18 months in a mental clinic and then walked free.

Despite an initial success in Vienna, The City without Jews was shown only a few times abroad, in various censored or abridged versions. The last known screening was in the Netherlands in 1933, as a anti-Nazi film. Portions of an incomplete print of that version, added to reels found in 2015 in a Parisian flea market, formed the basis of the current restoration. Given its sources, the result can hardly be identical to the original, but it plays very smoothly, and there are no noticeable remnants of gaps or re-editing. An account of the restoration is offered by Anna Dobringer as one of several brief essays in the booklet accompanying the dual DVD/Blu-ray release by Flicker Alley.

A satirical, serious picture of antisemitism

Of the four Jewish-themed films mentioned above, The City without Jews is the only overtly political one. Beslauer’s film, the action takes place in “Utopia,” a thinly disguised Vienna (where the film was shot), and many of the main characters are the Councillors and Chancellor.

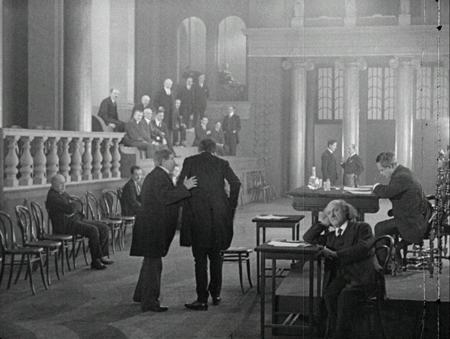

The film starts by emphasizing that assimilated Jews already established in Utopia worship alongside the recent Eastern Jews, as suggested by the two foreground figures in the opening synagogue scene (see top). The government finds it convenient to blame various problems, such as rising prices and unemployment, as well as the fall of the country’s currency, on the Jewish population. With mounting popular unrest, the Chancellor accedes to the idea of expelling all Jews from the city.

The result is a rather uneasy balance in the early portions of the film between satirical views of the local politicians, officials, and businessmen, and the very real sufferings of the Jews and their Christian supporters and spouses. (The film is a quite polished and expensive production, as the legislative chamber, above, shows.) The Christian officials are treated as caricatures, rather similar to the way officials are portrayed in Soviet films of the second half of the 1920s–which Breslauer, of course, could not have seen.

The scenes of the entire Jewish population being expelled, on the other hand, is treated quite seriously and fairly realistically. Scenes of families being dragged out of their homes are not at all humorous, and the departure en masse by train calls to mind methods that were to be used in reality little over a decade later–though here the trains are ordinary passenger ones rather than cattle-cars.

A rather odd premise which the film emphasizes is the impact that the expulsion has on marriages between Jews and Christians. No fewer than five mixed couples of various classes are made prominent, and all are ripped apart. One involves a rabid anti-Semite, portrayed as a drunken dolt. His daughter has married a Jewish man, and they have a daughter. The scene of the husband’s departure shows the anti-Semite (in dark coat at the center below) grieving along with his daughter as they watch the little girl saying good-bye to her father.

The author and filmmakers seem to understand well the familiar phenomenon of the bigot who is only brought to sympathize when people who are discriminated against turn out to be members of their own family.

Pure satire takes over

Once the Jews are gone, the satirical approach fully takes over. It turns out that the Jews had been the foundation of everything good and strong in the Utopian society. Businesses collapse, the currency falls, foreign countries boycott Utopia, and foreign banks (being controlled by Jews) refuse to loan the failing government money. The Chancellor and his allies lament that they no longer can blame the Jews for these problems.

More amusingly, the culture falls apart. High society people who had only dressed elegantly because Jews did decide that they don’t need to buy the latest fashions. One powerful businessman who runs an expensive ladies’ clothes emporium discovers that his establishment is no longer profitable (below left). Austrian men abandon their dignified suits and revert to their casual clothes and giant tankards of beer (right). The sophistication associated with the Jews has disappeared. (All this forgets the recently arrived Eastern Jews, with the action concentrating on the very much assimilated ones.)

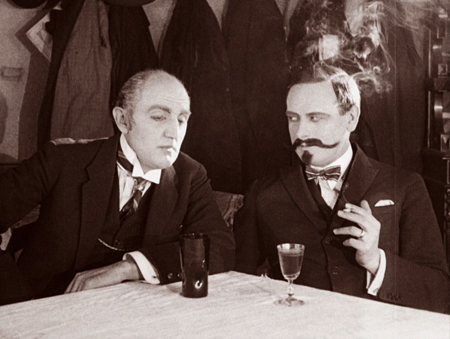

Among the five Jewish-Christian couples separated by the expulsion is Leo Strakosch, who is engaged to the daughter of one of the local Councillors. He emerges as the film’s protagonist, returning to Utopia in the persona of a Parisian painter and Roman Catholic. His disguise makes him look like a thinner version of Dr. Mabuse (top of this section), and one suspects that Lang’s two-part film, released in 1922, had not gone unnoticed.

Like Mabuse, Leo manipulates the dire political situation, campaigning for a repeal of the expulsion order and a return of the Jews as the only way to save Utopia’s situation. He does so, of course, in a good cause. Ultimately the decision concerning the repeal hangs on a single vote lacking for the two-thirds majority needed to rescind the order.

Leo gets one of the Councillors drunk and sends him away during the vote, thus causing the repeal to succeed.

The result is a huge success. Jews return, sales and the currency rise, mixed couples are re-united, and the government now credits the returning Jews with the restoration of the country’s health. Strakosch, now out of his disguise, is greeted as the first returnee by cheering crowds and bouquets.

Expressionism as revenge

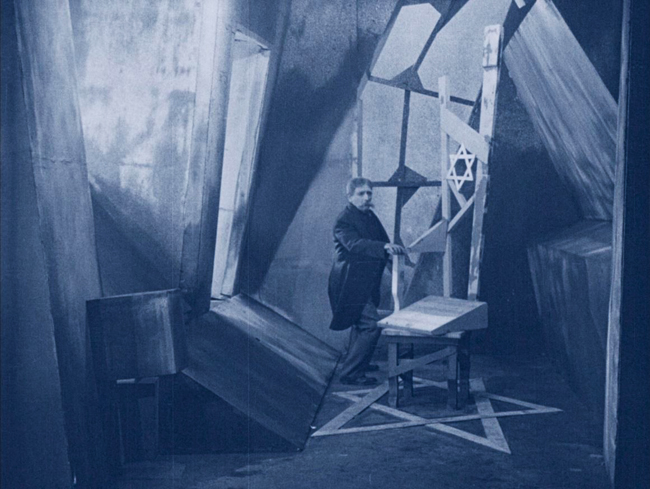

The drunken Councillor whose lacking vote caused the return of the Jews ends up in a scene that quite explicitly imitates the end of The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. He dreams of being imprisoned in a cell with Jewish stars built into the scenery (see bottom). He recoils in horror at the sight. This is followed by a shot of a doctor (above) who declares, “A strange case of delirium, my dear colleague. The man imagines himself to be a Zionist.” I dearly hoped that he would go on to say, “I think I know how to cure him now,” but it was not to be. Obviously the diagnosis is completely wrong, since the Councillor is terrified by the Jewish imagery in his cell. But of course, Dr. Caligari’s diagnosis may have been wrong as well.

The film is accompanied by a charming score, provided by pianist Donald Sosin and violinist Alicia Svigals. For a list of bonus materials, click on the link at the top of this post.

The City without Jews has fallen into the state of an obscure film, no doubt, but it deserves more attention now than it received at the time of its release. It has become a cliché to point out that a film of the past speaks to our current world situation. Still, this film does.

Thanks to Jeffery Massino and the team at Flicker Alley!

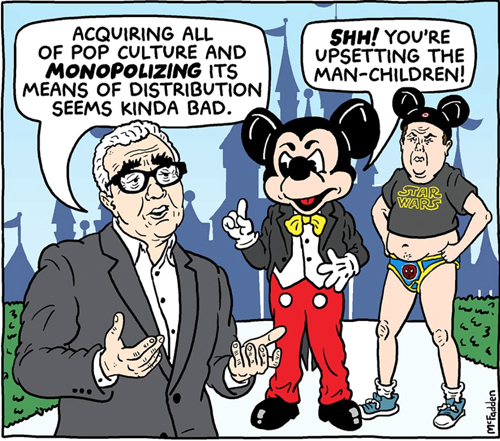

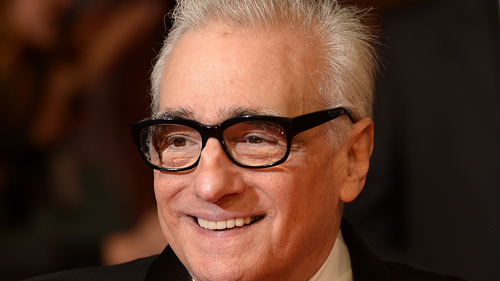

Captain Cinephilia: Scorsese strikes back

Brian McFadden, No One Is Safe: Martin Scorsese Roasts Your Fandom.”

DB here:

It started with a brief, almost offhand remark.

“I don’t see them,” [Scorsese] says of the MCU [Marvel Cinematic Universe]. “I tried, you know? But that’s not cinema. Honestly, the closest I can think of them, as well-made as they are, with actors doing the best they can under the circumstances, is theme parks. It isn’t the cinema of human beings trying to convey emotional, psychological experiences to another human being.”

When I learned about this interview (Empire, November issue), I took it as simply a roundabout statement of personal taste. Scorsese doesn’t find Marvel movies, and perhaps other comic-book sagas of superheroes, to his taste. He gave them a fair shot, but he now no longer sees them. He considers them visceral stimulation, like carnivals or theme parks. They’re not cinema, if you consider cinema as emotional expression of psychological conflicts.

In the massive responses to Scorsese, people pointed out that viewers often respond emotionally to superhero films. They root for certain characters, they’re amused or thrilled by certain situations, and many claim to be deeply moved by the heroes and villains (Loki, even Thanos). In fact, it’s exactly the “emotional, psychological experiences” embedded in the Marvel and DC plots that some fans say distinguish them from crude comic-book movies that went before. Much the same could be said of the Bond films, which became more humanized with Quantum of Solace, though intermittently before.

As for the claim that the superhero films “aren’t cinema,” I wasn’t really upset. Over the decades we’ve heard that 1910s films “aren’t cinema” (too theatrical), or that adaptations of novels or plays “aren’t cinema” (too literary or stagebound), or that narrative films “aren’t cinema” (usually proposed by avant-gardists). When the claim relies on a notion of some cinematic essence (editing, or pure visual form) that’s missing from this or that movie, you might be able to have a productive conversation. But if “This isn’t cinema” comes down to “I don’t like films like this,” we’re back to personal taste.

On other occasions Scorsese went on to say a lot more. The ultimate result was a 7 November article in the New York Times. I think we should take this as his most thoroughgoing effort to explain his thinking. We can supplement that with some remarks he made in interviews and Q & A sessions.

Herewith my attempts to figure out Scorsese’s argument. Trying to sort this out might teach us some important things about film now.

Scorsese in defense of Cinema

Scorsese’s Times article, “I Said Marvel Movies Aren’t Cinema. Let Me Explain,” begins by disclaiming any hatred for Marvel movies as such. “The fact that the films themselves don’t interest me is a matter of personal taste and temperament.”

But everyone’s taste gets shaped by their moviegoing experience, and in his youth Scorsese was attracted to films from America and Europe. These yielded “revelation—aesthetic, emotional, and spiritual revelation.” The films were, he felt, about characters who were complex, sometimes contradictory in their minds and behavior.

Moreover, these films showed that cinema was an art form, one existing in both commercial and more experimental spheres. Hollywood studio output (Ford Westerns, Hitchcock thrillers), European imports (Bergman, Godard), and avant-garde work (Scorpio Rising)—all these showed that cinema had powers equal to those of music, dance, and literature. These films were technically accomplished, sometimes virtuoso, but at their hearts were intense, complex emotional appeals that assured that they would be watched for decades later.

Today the Marvel pictures, often skillfully made, lack “revelation, mystery, or genuine emotional danger.” They are repetitive, adhering to a basic formula, “defined as variations on a finite number of themes.” By contrast, the films of Paul Thomas Anderson, Claire Denis, Wes Anderson, and other directors offer new and unpredictable experiences, and they expand the possibilities of the art form. “The unifying vision of an individual artist” is essential to cinema.

It’s exactly the exploratory filmmakers who are being stifled by the Marvel releases, and indeed all the franchises. These more personal films aren’t just constrained by lower budgets; they can’t get much exposure on theatre screens either. “Around the world, franchise films are now your primary choice if you want to see something on the big screen.” Most filmmakers design their films for that scale and that communal experience, but the blockbuster films are pushing smaller pictures into streaming outlets.

The franchise mentality is a corporate one. The products are “market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption.” As often happens, the business constrains the art. But you might say, what about the old studio system? Wasn’t that as mercenary as today’s franchise juggernaut? No, because the studios set up a creative tension between the business end and the artistic end that yielded outstanding works, even masterpieces. Today’s franchise producers are indifferent to art and hold a view of film history that is both “dismissive and proprietary.”

As a result we have two domains: worldwide audiovisual entertainment vs. cinema. They overlap less and less, and it seems likely that the financial power of one will dominate and belittle the other.

I think that some of these arguments are plausible, while others deserve more probing.

Film art: Who’s the artist?

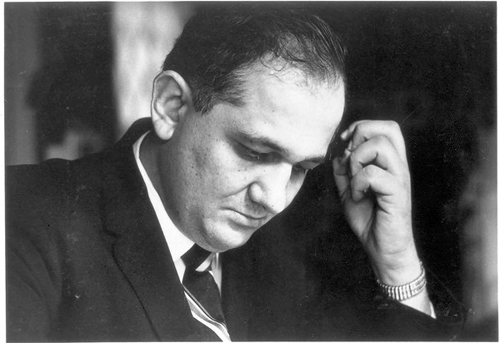

Andrew Sarris.

During the 1950s and 1960s, this general argument was promulgated by the so-called auteur critics around Cahiers du cinéma and was developed and promoted by Andrew Sarris in the US and Movie magazine in the UK. Scorsese was deeply influenced by these ideas. He was one of many cinephile directors-in-training who assumed that the best films bore the “unifying vision of the individual artist,” who was the auteur (author) of the film.

What was considered the “auteur theory” is too complicated to explore fully here. Minimally, it’s the idea that, all other things being equal, in many movies (often the best ones) the director can be considered the source of the film’s distinctive artistic qualities. The director may achieve this by exercising near-total control (e.g., Chaplin), or working with close collaborators (Powell and Pressburger, Donen and Kelly) or serving as a “filter” for the offerings of various contributors (probably most filmmakers).

This is the minimal case. The maximal one rests on the idea that once we make the director the central power, we then discover a “unifying vision.” At this level the distinctive features of form, style, and theme coalesce into a personal conception of human life. For Ford, that might include the value of traditions and the costs they demand of those subscribing to them. Hitchcock’s recurring concern, Robin Wood famously argued, is the realization that complacency, a trust in social order, is vulnerable to disruption.

The difference between the two versions I’m sketching isn’t hard and fast. Still, it often holds good. A friend, for instance, grants that Tony Scott is a distinctive filmmaker. “He just has nothing to say.” The idea that an auteur has something consistent and personal to “say,” deliberately or unconsciously, from film to film, is a hallmark of auteur criticism at its most ambitious. And the greatest auteurs, perhaps, show development in what they say across their careers. John Ford’s attitude toward the frontier can be said to change from The Iron Horse (1924) to Cheyenne Autumn (1964).

The minimalist auteur concept isn’t new. From the 1920s on, historians and critics often attributed creative authority to Griffith, Chaplin, De Mille, Hitchcock, and European and Soviet directors. And in most film industries, executives recognized that the director had the most responsibility for the film’s look and feel.

One revolutionary edge of auteur criticism was to discover auteurs nobody had noticed before–largely unknown filmmakers working alongside humbler folk. And the critics went further, suggesting that some of these filmmakers could be considered auteurs to the max.

Typically auteur critics didn’t examine the concrete context of production to determine who did what in particular cases. They inferred directorial expression by watching lots of films and tracing recurring strategies of style and theme. Sometimes they backed their conclusions up by interviews with–who else?–the director.

Minimal versions of the auteur idea are central to film culture now. Festivals promote directors, as do studio marketers. Movie lists in reference books and search sites give directors the pride of place. Variety and Hollywood Reporter reviews usually don’t name producers, cinematographers, and other contributors, but the director is always mentioned (and blamed or praised for the film). Academics and cinephile critics ascribe more maximalist “personal visions” to directors around the world, from David Lynch and Spike Lee to Wes Anderson to Wong Kar-wai and Jane Campion.

Auteur +genre = ?

Black Panther: Danai Gurira (Okoye), Ryan Coogler on the set.

Despite the prominence of some directors, they’re usually not what draws audiences. In most countries, the mass-market cinema is dominated by genres that are populated by well-known stars.

Sarris and others assumed that auteurs built upon the foundations provided by genre conventions and star images. Ford gave the Western a new force not only through his images and use of music but also by redefining the star personas of John Wayne and Henry Fonda. Hitchcock and Lang worked with and against the conventions of the thriller, while Ophuls gave the melodrama a melancholic elegance. Or so goes auteur gospel.

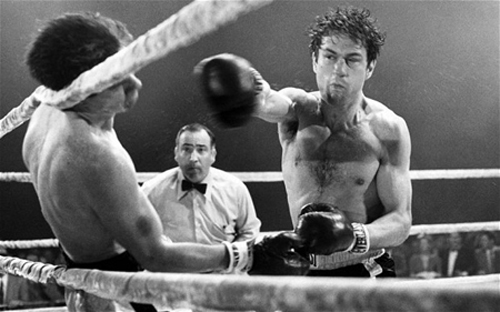

The 1970s New Hollywood auteurs embraced genre filmmaking as well. Bogdanovich, Coppola, Altman, Woody Allen, and others tested themselves in a variety of genres. Even Scorsese tried a “woman’s picture” (Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore), a musical (New York, New York), and a biopic (Raging Bull). They are only roughly parallel to today’s indie filmmaker who, after a breakthrough project at Sundance or SxSW, signs on to make a franchise picture.

As a generous and enthusiastic cinephile, Scorsese has long subscribed to a version of auteurism. Perhaps one source of his misgivings about Marvel and its counterparts is that he can’t detect auteurs in these movies. Does that mean they aren’t there? Is today’s studio cinema largely a genre cinema, minus the classic bonus of high-end auteur expression?

One of his comments has attracted little notice. Scorsese remarks of the theme-park picture:

The technique is very well done but there is only one Spielberg, there is only one Lucas, James Cameron. It’s a different thing now.

This implies that even the franchise genres could sustain some degree of what Sarris called “directorial personality.” Admirers of Taika Waititi’s Thor: Ragnarock, James Gunn’s Guardians of the Galaxy, Ryan Coogler’s Black Panther, or Patty Jenkins’ Wonder Woman might agree. This has been one line of defense in the pushback to Scorsese’s comments.

Or maybe we should attribute whiffs of personal expression today to the producers (Bruckheimer, Kathleen Kennedy, Kevin Feige). Even in Hollywood’s heyday, we sense Gone with the Wind and Duel in the Sun as Selznick productions. Then there’s Walt Disney, surely a producer as auteur. I suspect that Scorsese finds these old films more inspiring than today’s behemoths.

Closing the drawbridge on Fort Multiplex

Avengers: Endgame (2019).

A genre can rise and fall in popularity. As the Western and the musical declined in the 1970s, horror and science-fiction gained traction as both programmers and A-list blockbusters. Add in the rise of fantasy, crystallized in the prestige accorded the Lord of the Rings installments. Oddly, as comic book sales declined, comic-book movies came to be a central contemporary genre. The superhero film proved a powerful blend of all these trends.

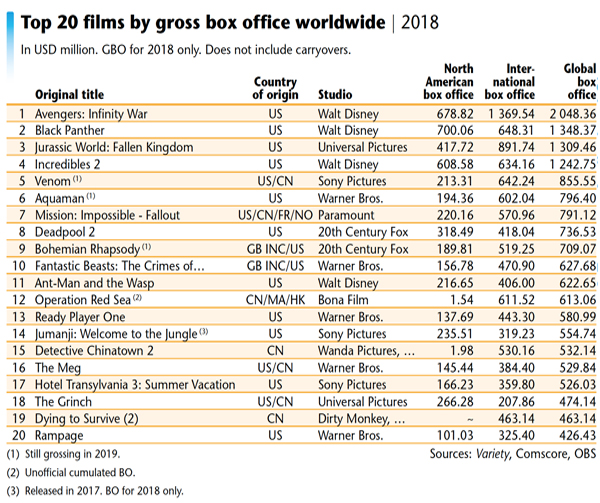

Today, the stifling presence of the fantasy/SF/comic-book franchises seems obvious. Look at two snapshots.

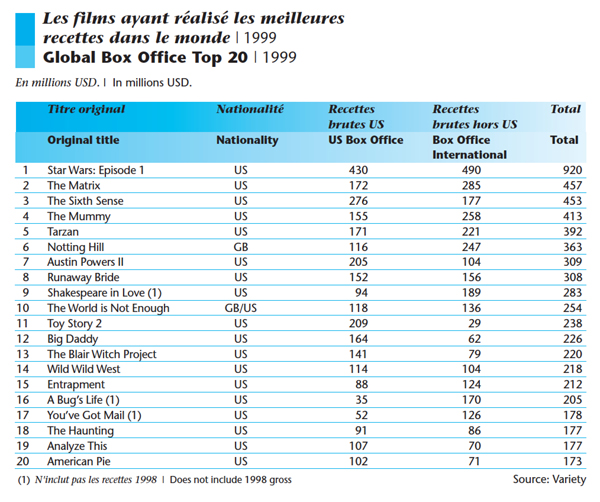

In 1999, the world’s top-grossing film was Star Wars: Episode 1. Among the twenty top hits were fantasy/SF blockbusters The Matrix and The Mummy, as well as a Bond entry. But there were also lower-budget horror films (The Sixth Sense, The Blair Witch Project). Most surprisingly, the top twenty include many comedies, mostly star-driven.

Now consider the 2018 situation.

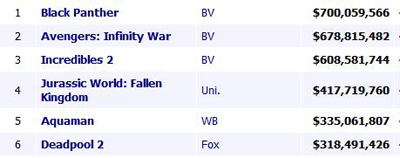

Five of the global top ten were superhero films. The big winner was Avengers: Infinity War, which earned over two billion dollars globally–nearly twice as much as second-place Black Panther. Among the top ten are Venom, Aquaman, and Deadpool 2. Add The Incredibles as a sixth superhero film if you want. At 11 is Ant-Man and the Wasp. Most of the remaining titles are also franchise entries. There’s also the fantasy/SF blend Ready Player One, the monster movie Rampage, and the action thriller The Meg. Only China is offering live-action comedy (Detective Chinatown 2) and drama (Dying to Survive).

Of course nobody knows better than Scorsese that the big-budget fantasy/SF film has long been with us. His New York, New York (1977) came out the same year as Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind, while 1980 saw the release of both Raging Bull and The Empire Strikes Back. But in those years straight-up genre films had a fighting chance. Smokey and the Bandit, The Goodbye Girl, 9 to 5, Airplane!, and others won big box-office.

Scorsese films have landed in the top twenty occasionally (e.g., The Color of Money and The Wolf of Wall Street). On the whole, though, I’m not suggesting that Scorsese now sees himself as competing with the biggest grossers. He’s surely right that today’s superhero films dominate the landscape. But do they squeeze out other films to the degree he suggests?

In some venues, probably yes. Small towns with one or two multiplexes may not have space for the minor-key movie. But bigger towns and midsize cities can be quite hospitable to them. In one week, alongside the big releases, multiplexes in my town of Madison, Wisconsin (pop. about 250,000) played Motherless Brooklyn, Jojo Rabbit, Parasite, The Lighthouse, The Current War, Brittany Runs a Marathon, and documentaries on Molly Ivins and Miles Davis. At least some of these qualify as original vehicles. At its widest release, The Lighthouse played on nearly 1000 US screens, and Jojo Rabbit arrived at over 800.

These are merely data points, not systematic samplings. And you might argue that we’re in the middle of Oscar qualifying season, so more offbeat films are numerous now. Okay, go back to July, the most competitive month for domestic releases. Nationally, the big pictures didn’t prevent the release of Yesterday, Midsommar, Late Night, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, Booksmart, The Dead Don’t Die, The Biggest Little Farm, The Farewell, The Art of Self-Defense, Amazing Grace, and Once Upon a Time…in Hollywood.

Again, not all of these count as auteur vehicles, and several failed domestically, but they still squeezed into multiplexes. The Tarantino film obviously commanded a wide release, but many of the titles I mentioned played on between 1000 and 2000 screens. Booksmart opened on over 2500, Midsommar on 2700.

The industry doesn’t depend on the smaller or more personal titles, but then it seldom has. The biggest box-office successes in the heyday of the studio system were almost never auteur classics. Variety reported that the top domestic hits of 1943 were For Whom the Bell Tolls, Song of Bernadette, This Is the Army, Stage Door Canteen, Random Harvest, Hitler’s Children, Casablanca, Madame Curie, Star Spangled Rhythm, and Coney Island. True, Frank Borzage struck gold with Stage Door Canteen, but it’s not typical of his work. Lubitsch (Heaven Can Wait) and Hitchcock ( Shadow of a Doubt) were far down the list, bested by the likes of Sam Wood, Clarence Brown, and Henry King.

Or take 1952, ruled by The Greatest Show on Earth (De Mille), Quo Vadis, Ivanhoe, The Snows of Kilimanjaro, Sailor Beware, The African Queen (Huston), Jumping Jacks, High Noon (Zinneman), and Singin’ in the Rain (Donen/Kelly). True, The Quiet Man hit number 12, and Mann’s Bend in the River number 13. But of the top hundred the only other auteur pictures seem to be Pat and Mike (no. 39), Monkey Business (no, 47), Carrie (no. 54), The Lusty Men (no. 76), and Five Fingers (no. 85).

It seems plausible, then, that in Hollywood “audiovisual entertainment” has overwhelmingly dominated the market for decades. Auteurs seldom win the biggest grosses. But again Scorsese’s career history may have influenced his judgment.

There was a moment, the Holy 1970s, when genre cinema with a personal-vision inflection was occasionally lucrative. The Godfather, One Flew over the Cuckoo’s Nest, American Graffiti, Blazing Saddles, Alien, Apocalypse Now, The Shining, and other notably original productions did earn money and awards. Yet in retrospect that seems an interregnum. The top rentals of the following decade, the 1980s, were dominated by Spielberg and Zemeckis. Then there were the usual array of star-driven comedies and action pictures. Genres came back strong, and auteurs had to work within them, or around the edges.

Such is pretty much the case right now. At the top end, perhaps the superhero films are roughly equivalent to the biblical sagas, historical pageants, and theatrical adaptations that roadshowed throughout the 1950s and 1960s. Now as then, a number of auteur films are still getting theatrical releases. The blockbusters keep the lights on and the popcorn moving so that theatres can afford to wedge straight-up genre pictures and offbeat indies into their week. It seems that you can’t run Avengers: Endgame on all 22 screens.

Art vs. craft?

Anthony and Joe Russo directing Avengers: Endgame.

But maybe we shouldn’t think of the big pictures as “audiovisual entertainment.” What’s opposed to that? “Cinema,” Scorsese said. I’d propose that this formulation means “artistic cinema.” Which is to say that we’re in the realm of the classic distinction between art and entertainment.

This has given an opening to the people riled up by Scorsese’s remarks. Admirers of Marvel, DC, and comparable pictures can say that they find them as emotional, revelatory, inspiring, etc. as anything he finds in Bergman or Sam Fuller. They feel it in their bones. And who’s to gainsay that? Scorsese doesn’t have their bones, and neither do you or I.

On more objective grounds, I suggest that Scorsese has floated another distinction. Forget calling some things “cinema” and some things not. I think that he’s distinguishing craft from art.

Let’s say provisionally that craft is the skillful manipulation of the medium to produce the desired effects. Art, on this understanding, can be considered something more. It’s usually grounded in craft, but not always. It’s also formally and emotionally complex, original in its relation to what came before, and offering new experiences on repeated exposure (rather than replays of the original response). Many, like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, would add that art induces reflection on ourselves and the world, making us wiser and deepening our humanity.

From this angle, Scorsese’s recognition of the “talent and artistry” of franchise films can be seen as a nod to craft competence. “The technique,” he says, “is very well done.” Our blockbusters are comparable to many of those anonymous hits of the studio era, turned out by skillful but impersonal artisans.

In response, the MCU advocates would need to show that the films go beyond craft. For example, some advocates find in these films the kind of character complexity Scorsese attributes to Hitchcock. He finds that Roger Thornhill in North by Northwest suffers “painful emotions” and an “absolute lostness.” Marvel fans will say something like this about moments in the stories of Tony Stark, Captain Marvel, Captain America, and the Winter Soldier.

Scorsese might reply that these are not complex characters. Yet for many years people said the same about the work of Hitchcock and other Hollywood auteurs. When people started to study them, we saw things differently. Only closer analysis of the comic-book films can give us better grounds to argue about whether their characters exhibit the “contradictory and sometimes paradoxical natures” Scorsese champions.

Realism and its rivals

Captain America: The Winter Soldier (2014); Raging Bull (1980).

A few scattered speculations and I’m done.

I don’t know that we’ve fully recognized that these SF and fantasy franchises descend from earlier forms. Silent crime serials and installment films featuring Dr. Gar el-Hama and Judex had the same reliance on secret identities and world-threatening master villains. Chinese wuxia films gave their knight-errants the power to soar into the air (the “weightless leap”) and emit blasts of energy (“palm power”). The bullet ballets of Hong Kong films have obviously influenced Hollywood action pictures, but we haven’t acknowledged how our comic-book movies incorporate fantasy martial arts techniques. Hollywood owes Asian action cinema more than we usually admit.

But the silent policiers and the fantasy wuxia are flagrantly unrealistic. And Scorsese, more than many of his colleagues, is committed to realism. He couldn’t, I think, make Big Trouble in Little China or Kill Bill. I’d suggest he’s intrinsically out of sympathy with quasi-supernatural action. (Hugo is a historical film, and it’s about a sacred era of Cinema past.) Superhero dramaturgy, I hazard, rubs him the wrong way, and not just because it lacks psychological depth.

I’ve argued elsewhere on this blog that Scorsese makes forays into expressionist and impressionist technique, but they usually issue from a base of harsh realism. His commitment to realism may make it hard for him to engage with the more outrageous narrative conventions of the superhero film.

Here another classic dichotomy suggests itself. If you have to choose between basing your story on plot or character, Scorsese will choose character. In fantasy films, though, character motive and reaction are based on elaborate plot machinations. These films depend a lot on elaborate fake identities, as well as recognitions of hidden kinship. She’s my sister! He’s my father! Such devices serve to provide intricate genealogies and networks of relationships for fan homework.

Likewise, theatrical melodrama and adventure fiction from the nineteenth century supply superhero sagas with orphans of mysterious parentage, duels, hairbreadth escapes, family secrets, coded documents, precious but mysterious objects, and other franchise conventions. These are woven into complex schemes and counter-schemes of the sort found in the silent crime serials. But all these features run counter to the psychological conflicts that animate Scorsese’s plots.

Recognitions of kinship rely in turn on a plot strategy that’s worth discussing a little more; I suspect it yields much of the emotional resonance that fans enjoy. These films rely on courtship and romantic rivalries throughout, of course, as well as friendships forged and broken. These are standard for most American genres. But I’ve been surprised at how often family relations are developed in complicated ways.

It’s not just Star Wars. The Marvel Universe relies heavily on kinship to sustain its plots, as well as its pathos. Tony Stark and Pepper Potts have a daughter, as does Scott Lang. Hawkeye has a family, as does T’Challa, whose cousin N’Jadaka becomes a prime adversary. Nebula and Gamora are pressured to be dutiful daughters to Thanos. Thor and Loki share a mother, Frigga. You can argue that Tony Stark becomes a father-figure for Peter Parker. Other characters are more isolated, but for some of them, notably Natasha and Bucky, the Avengers team constitutes a surrogate family.

Marvel’s focus on the family asks us to exercise the skills we must bring to classic mythology, nineteenth-century novels, and TV soap operas. We need to keep track of who’s related to whom, and what in their past encounters can arouse obligations and conflicts. I don’t think that plots resting on such dense kinship relations are of great appeal to Scorsese; his families, when they’re present at all, are pretty small-scale (Raging Bull, Cape Fear, Shutter Island, The Age of Innocence).

Most of all, when Scorsese speaks of these films shying away from risk, I suspect he’d include their avoidance of narrative risk. In fantasy and SF, nobody need really die. Hero, villain, love interest, and sidekick can return in a parallel world, or they can be resuscitated through a new gadget. The worst outcome need not be the worst, as when Avengers: Endgame uses nanotech and time travel to rewrite the past. Plot mechanics again. Despite all the assurances that Tony Stark is really, really gone, we could find a way to bring him back if Downey wanted to sign on again. (Black Widow is being resurrected for a prequel adventure.) But there’s no bringing back Sport from Taxi Driver or Rodrigues from Silence—except in a prequel, another convention that Scorsese would likely disdain.

I’m just spitballing here, but for Scorsese and other stylized realists like Michael Mann, the comic-book convention of eternal return might seem merely juvenile wish fulfillment. Something really has to be at stake, and ultimates must be faced’ Danger and death are real. This is grown-up drama.

I’m not intrinsically opposed to the conventions ruling comic-book movies myself. In general, I think that plot is as underrated as character is overrated. (I’d rather give up the distinction altogether, but that’s another story.) Superhero films are mostly not to my taste, but I think they’re worth studying as intriguing contributions to trends in modern cinema. My point is just that the personal aesthetic of Scorsese, as both cinephile and cineaste, doesn’t fit very well with the elaborate, ever-changing rules of the magical MCU. He finds enough magic in a sinuous tracking shot, or a carefully synced doo-wop song, or an unexpected angle, or a wiseguy shouting match. That is Cinema.

There are other questions we might ask about Scorsese’s remarks. For instance, when he celebrates the thrill of communal moviegoing as a central feature of Cinema, he seems to ignore the fact that the franchise pictures are our prime multiplex attractions. Many viewers slot the more “personal films” into a future Netflix queue, but they commit themselves to seeing the big films on the big screen. That choice can yield contemporary viewers some of the electricity that Scorsese found at a screening of Rear Window. And when they’re not checking their text messages or chatting loudly with their pals, they might even give themselves up to laughs, screams, and applause, just as in the old days.

Since I wrote this, though, something much more draconian than superhero pictures may threaten non-franchise pictures. On Monday, Assistant Attorney General Makan Delrahim said that the Department of Justice is moving to end the consent decrees that have governed Hollywood studio conduct since 1948. (See here and here.)

The implications of this are staggering. We may see the return of block and blind booking, the prospect that a studio could own a theatre chain (and give favored place to its own pictures), and the decline of independent producers and art houses that favor smaller films. Nonsensically, Delrahim quoted an earlier Scorsese remark about his craft: “Cinema is a matter of what’s in the frame and what’s out.” Delrahim went on: “Antitrust enforcers, however, were not cast to decide in perpetuity what’s in and what’s out with respect to innovation in an industry.” Thus the ideology of predatory “disrupters” goes on, and even auteurs are unwillingly recruited to the enterprise.

Thanks to Jim Danky for calling my attention to the McFadden comic, and to Jeff Smith for discussions of Scorsese’s arguments. Thanks as well to Colin Burnett for discussion of the Bond saga.

My lists of top-twenty films come from the European Audiovisual Observatory’s publications Focus 1999 and Focus 2019.

I’ve left aside other writers’ analyses of Scorsese’s views. I benefited from reading Ben Child and Helen O’Hara in The Guardian, Christopher Orr’s older review in The Atlantic, and Zachary Zahos at Playback. Also pretty forceful is Kevin Feige’s defense of the MCU, which I discovered only after writing this entry. He argues for Marvel films’ value on several grounds, including their display of positive social values. And just before I posted this, the Russo brothers weighed in.

Here are other Scorsese comments made before the New York Times piece appeared. After his BAFTA David Lean lecture on 12 October, he reiterated his view.

Theatres have become amusement parks. That is all fine and good but don’t invade everything else in that sense. That is fine and good for those who enjoy that type of film and, by the way, knowing what goes into them now, I admire what they do. It’s not my kind of thing, it simply is not. It’s creating another kind of audience that thinks cinema is that. If you have a child and the child wants to see the picture, what are you going to do? It’s up to you. The audience that sees them now, the fans that see those pictures now, they were raised on pictures like that.

The technique is very well done, but there is only one Spielberg, only one Lucas, James Cameron, it’s a different thing now. It’s an invasion, so to speak, in the theatre. . . .

We are in a moment not only of evolution but of revolution, in pretty much the whole world, everything we know, the old political systems, it’s almost as if the 21st century is beginning now and technology has gone with it and that means cinema goes with it.

Yes, see a movie in a theatre, it’s the best with an audience, but the actual concept of cinema has become something that is not definable. Something can play as a hologram, something can play as virtual reality, maybe there is going to be an extraordinary epic in virtual reality at some point. We have to start expanding what we think of as narrative, music, literature, art and particularly the visual image.

Granted, this whole passage is a bit baffling. It’s not completely clarified in a press conference the next day at the BFI London Film Festival. The relevant section starts at 16:26.

It’s also interesting that Benedict Cumberbatch (aka Dr. Strange) defends the need for auteurs.

Some comments on Sarris’s career and the vagaries of auteur theory are here. I discuss Black Panther and its debt to classical Hollywood storytelling here.

Francis Ford Coppola, Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, George Lucas (2007).

Could Hollywood possibly be in a box-office slump? Yet again?

Kristin here:

Speculative articles are presumably a lot cheaper for a news publication to run than are those pieces that involve travel, time-consuming research, and tracking down experts to weigh in on important events. The reporter need just sit at a computer, look at whatever evidence is at hand or a phone-call away, and opine on what one might expect to happen in the future. In part, of course, the opinion will be based on what happened in the past. The question is, what sort of information from the past would be most helpful in speculating with some likelihood of being right.

Not that it matters too much, since it’s pretty rare that months after events happen anyone goes back and checks on predictions made about them. That goes for prognosticators of award winners and of future hits and flops.

What might happen?

Facebook profile image for The Numbers research service

In this era of shrinking news media and burgeoning everything-else media, speculation has run rampant. It sustains the 24-hour news channels between breaking stories and a lot of print publications as well. Politics can generation all sorts of guesses and opinions, especially now, since there are so many players who can’t be expected to behave rationally. Variety and The Hollywood Reporter (both of which have advertising-supporting online versions) were once full of useful, hard-news articles that we film historians could snip and file away for, oh, say, cyclical revisions of a film-history textbook. Now David and I still subscribe to both and consider ourselves lucky if an issue has one or two truly informative pieces.

Not that these venerable publications are overwhelmingly full of speculative pieces. There’s the gossip, the real-estate section, the fashion section, the ten or twenty-five or one hundred most-powerful [fill in the blank] in show business, and so on.

But speculation seems to dominate in trade journals devoted to entertainment and film. There are obviously the predictions for Oscars and Emmys and other awards, which have become a year-round occupation. (The Oscars were given out in February, and almost ever since we’ve been getting lists of possible nominees for 2019, many for films not coming out for months.) Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and other trades indulge in awards-prediction coverage far more extensively than they used to, since it presumably extends the period during which film studios and distributors take out expensive “For your consideration” ads.

Box-office trends are often interesting and even useful to read after the fact, in the year-end analyses. They are, however, pretty vapid when presented piecemeal, month by month. There are a great many clichés that writers trying to fill page-inches with speculation can treat as if they are news. One particularly persistent and illogical one is that the industry must be in a slump when total grosses go down after a record-breaking year. We’re now at that stage in 2019 when enough films have come out to allow comparison with last year’s figures by this date.

Pamela McClintock recently wrote such an article for The Hollywood Reporter: “Will Red-Hot Avengers Blaze the Path to a Sizzling Summer?” in the April 30 print edition, and, with the strange habit that these trade papers have of changing articles’ titles for the online version, “‘Avengers: Endgame’ Will Need More Help to Save Summer Box Office”. Just after Avengers: Endgame opened, McClintock wrote that

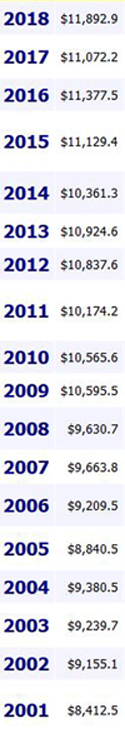

North American revenue is still down 13.3 percent year-over-year during the January-to-April corridor, throwing cold water on predictions that 2019 could eclipse the best-ever $11.9 billion of 2018. (Before Disney’s Endgame unfurled April 26, revenue year-to-date was running nearly 17 percent behind last year, its lowest clip in at least six years.)

Nonetheless, analysts remain cautiously optimistic that Hollywood can at least match, if not best, 2018’s mark by Dec. 31, with predictions for the global haul settling a new benchmark of north of $41 billion.

These predictions are based on optimism about the plethora of upcoming sequel items and reboots: Aladdin, The Lion King, Toy Story 4, The Secret Life of Pets 2, Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbs & Shaw, Spider-Man, and Godzilla: King of the Monsters.

Let me point out three things.

First, in virtually all cases of year-to-year comparison are based on dollars unadjusted for inflation. Inflation is different in different countries, so trying to achieve a total global figure for any given year would involve a separate calculation for every country where movies are shown—which is close to, if not totally, impossible to do. Adjusted figures are helpful for some purposes, especially for comparing domestic grosses within the USA. For example, virtually everyone was claiming that the three Hobbit films outgrossed the original three Lord of the Rings films. In adjusted dollars, though, LotR is still the champ.

Here’s a helpful hint. Box Office Mojo has an inflation adjuster in its upper-right corner. If someone were to want to compare the domestic gross of Avengers: Endgame to that of some older film, say, Avatar, it would be informative to use the figure shown below instead of, or at least alongside, its gross in 2009 dollars: $749,766,139. (All figures in this entry stated to be in adjusted dollars were done using this feature, and all charts are from BoxOffice Mojo as well.)

Seeing film grosses go up year after year can give the impression that the industry can go on expanding its earnings forever. Even after a record year like 2002 or 2009 or 2018, pundits seem to assume a slump if the following year sees lower box-office results. But every year can’t be a record year (except in movie executives’ dreams). The list at the left gives the total domestic gross of each year from 2001 to 2018 in millions of unadjusted dollars. Part of the rise is due to inflation. Part of it comes from ticket prices  being raised beyond the inflation rate—which is part of inflation, especially from the ticket-buyer’s point of view. We all know, however, that the number of actual tickets sold is flat or declining, even if it spikes in a record year.

being raised beyond the inflation rate—which is part of inflation, especially from the ticket-buyer’s point of view. We all know, however, that the number of actual tickets sold is flat or declining, even if it spikes in a record year.

Second, usually a very few high-grossing films determine when there are record years. Avatar was the big film of 2009–but it had some help. More on this below.

Third, those high-grossing films are usually released in the summer and in the Thanksgiving-Christmas seasons. True, that cycle is breaking down in the current attempts by studios to avoid releasing the biggest films opposite or even near each other. Black Panther, the top grossing film of 2018, came out in February 16. The studio probably didn’t expect it to do as well as it did, but the very fact that a traditionally “summer”-type film came out that early and topped the charts will just reinforce the industry decision-makers’ believe that there can be big hits at any time of year.

The point, though, is that if really big films come out late in the year, their grosses earned after the New Year are counted for the following year’s total. So for example, Avatar came out on December 18, 2009, and well over half of its domestic earnings came in 2010: $466,141,929 out of the $749,766,139 total. As the list shows, total domestic earnings across the industry jumped by close to a billion dollars between 2008 and 2009, but there was almost no decline in 2010, partly because all but the first two weeks of Avatar’s run came then and partly because Toy Story 3 came out. As for 2009, it may have been the year of (two weeks of) Avatar, but it was also the year of Transformers: Revenge of the Fallen, Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, and The Twilight Saga: Full Moon.

Thus in talking about record BO years and why they happened, it helps to look at when the top earners of the previous year were released.

Take another example, 2002, which for years was considered the target to shoot for when it came to setting new records for grosses. That was the first year that the domestic gross was over $8 billion, and 2001 had been the first year over $7 billion.

The year 2002 was cited as the benchmark for the industry because it had four really major films come out–a relatively rare event, or at least it was then. Three of them were from some of the top franchises of all time, and one established what is now the top franchise of all time: Spider-Man, Star Wars Episode II: Attack of the Clones, The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets.

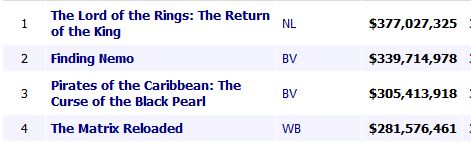

The last two titles were released on December 19 and November 15, so they helped make the 2003 total even slightly higher than the 2002 one—helped out by the top four of that year: The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, Finding Nemo (is Pixar itself a franchise?), Pirates of the Caribbean: The Curse of the Black Pearl, and The Matrix Reloaded.

In fact, no year between 2002 and 2009 went below the 2002 gross except 2005. In 2003, three films had grossed over $300 million domestically (below right), while in 2005 only one, Star Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith did. The number two film, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, led to two sequels (from a seven-book series) that fared significantly worse at the box office.

Wars Episode III: Revenge of the Sith did. The number two film, The Chronicles of Narnia: The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, led to two sequels (from a seven-book series) that fared significantly worse at the box office.

Beyond that, however, was the fact that there was relatively little continuing box-office income being generated by 2004 films in early 2005. The top three films had all been released early in 2004: Shrek (May 19), Spider-Man 2 (June 30), and The Passion of the Christ (Feb 25). The number four film, Meet the Fockers (Dec 22), contributed a healthy $103,501,600 to the 2005 grosses, but number five, The Incredibles (Nov 5) was largely played out by the end of 2004 and gave only $8,760,254 to the 2005 total.

Consider the calendar

I’m not going to say whether 2019’s gross domestic box office will surpass that of 2018, because it doesn’t matter that much. Annual figures fluctuate but have been remarkably steady over the years (adjusting for inflation). The industry will make a lot of money as a whole, and Disney will do extremely well. There will be the occasional modestly budgeted film that becomes a hit. Every year has its A Quiet Place or Crazy Rich Asians, numbers 16 and 17 among box-office leaders last year.

I can, however, point out some relevant contributing factors.

First, as in 2005, there’s an unusually small amount of money carried over from films released late last year and still playing early into 2019.

The top four films for 2018, Black Panther, Avengers: Infinity War, Incredibles 2, and Jurassic Park: Fallen Kingdom all came out in the summer or earlier. The fifth, Aquaman, is the exception,  released on December 21, it grossed $335,061,807, of which $196,040,927 was earned in 2019. The next “late” release in the top ten, Dr. Seuss’s Grinch (Nov 9) carried over a mere $2,167,215 into 2019, and Bohemian Rhapsody (Nov 7) a bit more with $25,026, 514 earned after the New Year. Thus 2019 has far less carry-over money contributed by 2018 releases than most years would. That’s presumably one reason–probably the main reason–why the first few months of the year have shown such a drop from the comparable period last year. That’s a little strike against 2019’s total that the pundits tend to ignore. Thus the early-2019 “slump” doesn’t necessarily mean that people are less interested in movie-going or that streaming services have suddenly made a huge impact. It just means that the biggest hits were released too early in the year to carry over much late income. It’s not necessarily a slump. It’s just that box-office income doesn’t really go by calendar years, even though we measure it that way.

released on December 21, it grossed $335,061,807, of which $196,040,927 was earned in 2019. The next “late” release in the top ten, Dr. Seuss’s Grinch (Nov 9) carried over a mere $2,167,215 into 2019, and Bohemian Rhapsody (Nov 7) a bit more with $25,026, 514 earned after the New Year. Thus 2019 has far less carry-over money contributed by 2018 releases than most years would. That’s presumably one reason–probably the main reason–why the first few months of the year have shown such a drop from the comparable period last year. That’s a little strike against 2019’s total that the pundits tend to ignore. Thus the early-2019 “slump” doesn’t necessarily mean that people are less interested in movie-going or that streaming services have suddenly made a huge impact. It just means that the biggest hits were released too early in the year to carry over much late income. It’s not necessarily a slump. It’s just that box-office income doesn’t really go by calendar years, even though we measure it that way.

Given this rare disadvantage, can this year’s blockbusters make up the difference and match or top 2018’s total grosses? Let’s do what Box Office Mojo does: look at what the last film of the franchises made. Let’s do that in adjusted 2019 dollars.

I should note that now more big tentpole films are grossing a very large amount of the total box-office. The three top films that helped create last year’s record made over $600 million domestically: Black Panther at $700.1 million, Avengers: Infinity War at $678.8 million, and Incredibles 2 at $608.6 million. Compare this to the 2003 chart above, where the top earners were making in the $300+ million range. That shift can’t be wholly accounted for by inflation, which isn’t that high.

How many films this year can do that, or at least get over $500 million? Even as I post this, Avengers: Endgame is hovering on the brink of passing $800 million. How about Toy Story 4 (which deserves to, if only for its incredibly clever and funny trailers)? Toy Story 3 made, in 2019 dollars, $480.6 million. Beauty and the Beast made $511.8 million, and The Jungle Book $375.8 million. Disney has two of these remakes coming out this year, Aladdin and especially The Lion King. These three seem the likeliest possibilities.

Beyond that, The Secret Life of Pets made $389.0 in 2019 dollars. On the lower side, The Fate of the Furious made $227.5 and Godzilla $217.2.

The weirdest thing about the current speculation is that the prognosticators aren’t even talking about the entire year. Despite McClintock’s mention of total grosses for 2019 at least matching those of 2018 by December 31, the latest film that she mentions is Fast & Furious Presents: Hobbes & Shaw, due out August 2. But why are we worrying about a slump when it’s plausible that just the films released up to that point could by themselves bring the total at least close to last year’s? We’re witnessing a film that will make as much as two ordinary blockbusters and possibly become the top grosser of all time (in unadjusted dollars, at least). We’ve already seen one low-budget film become a hit. Us grossed $174,580,800–oddly enough, very close to the total for Crazy Rich Asians, which did the same last year. As I’ve suggested, we could anticipate at least two or three summer blockbusters grossing in the $500-600 million range.

But more importantly, there are, after all, films to come after August 2. Big films. Most notably, Frozen 2 on November 22. Frozen made $441.8 in adjusted dollars. There’s the untitled Jumanji sequel; the previous Jumanji entry made $404,515,480. (The BoxOffice Mojo adjuster isn’t adjusting 2017 or 2018 to 2019 dollars yet.) There’s Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker. The last Star Wars movie, Solo, was an exception to the saga’s fortunes, making only $213,767,512; so let’s take the previous one, Star Wars: The Last Jedi, which made $620,181,382 domestically. Beyond these there is a bunch of somewhat more modest sequels (Terminator: Dark Fate, It Chapter Two), as well as some potentially big stand-alones (Cats, A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood, Rocketman). I personally am rooting for Jojo Rabbit (below) to become an unexpected hit. We’ll see.

The lack of attention to films coming out late in the year does make some sense. Right now the industry is concerned to promote its summer films. That’s what marketing people want to talk about with trade-media journalists. November is a long way off. Plenty of time to start speculating about holiday box-office and the awards season come August.

All in all, taking the factors that I’ve laid out into account, it looks like a pretty safe year for Hollywood. I can’t quite help feeling that the hand-wringing over this putative slump just makes for a more dramatic story than one declaring that the 2019 box office is doing fine, thanks. Of course, it’s especially fine for Disney. The heads of other studios might be doing some justifiable hand-wringing.

Update, July 3, 2019: Now we’re into the summer season, and the pundits are still worried because this year hasn’t caught up with last year, where the high-grossing films came earlier in the year than usual. That said, I tried watching The Secret Life of Pets 2 on a transatlantic flight and was so bored I turned it off after about half an hour. That part of Rebecca Rubin and Brent Lang’s Variety article I can believe.

David has written an entry about a related ongoing trope in trade-journal coverage of the movie business. The box-office coverage during “slumps,” real or imagined, often gets linked to the “death of cinema” notion, which David discusses here.

Jojo Rabbit.

Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker

Thor: Ragnarock (2017).

Kristin here:

Not every independent filmmaker secretly longs to direct a big Hollywood blockbuster. Jim Jarmusch made a name for himself 33 years ago with Stranger than Paradise (1984) and won well-deserved praise for Paterson last year. Like other independent directors, Hal Harley turned from filmmaking to streaming television, directing episodes of Red Oaks (2015-2017) for Amazon.

Still, in recent decades the big studios have picked young directors of independent films or low-budget genre ones to leap right into big-budget blockbusters, and those directors have taken the plunge. Doug Liman’s Go (1999) was one of the quintessential indie films of its decade, but his next feature was The Bourne Identity (2002). Colin Trevorrow’s modest first feature Safety Not Guaranteed (2012, FilmDistrict) led straight to Jurassic World (2015, Universal); Gareth Edwards’ low-budget Monsters (2010, Magnolia) was directly followed by Godzilla (2014, Sony/Columbia) and Rogue One (2016, Buena Vista); and Josh Trank went from a $12 million budget for Chronicle (2012, Fox) to ten times that for the $120 million Fantastic Four (2015, Fox).

Something similar happens occasionally with foreign directors. Tomas Alfredson went from the original Swedish version of Let the Right One In (2008, Magnolia) to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011), and the Norwegian team Joachim Ronning and Espen Sandberg, after making Bandidas (2006, a French import released by Fox) and Kon-Tiki (2012, a Norwegian import released by The Weinstein Company) were hired to do Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017, Walt Disney Pictures) and the upcoming Maleficent 2.

Recently women have followed this pattern as well: Patty Jenkins, going from Monster (2003, Newmarket Films) via a long stint in television to Wonder Woman (2017, Warner Bros.), and Ava DuVernay, from two early indie features and Selma (2014, Paramount), again via television, to A Wrinkle in Time (forthcoming 2018, Walt Disney Pictures).

Some of these directors have made the transition smoothly and successfully and some have not. Perhaps the most spectacular success has been that of Christopher Nolan, who went from Memento (2000) via Insomnia (2002) to Batman Begins (2005) and far beyond. But more about him later.

Why have indie filmmakers been able to make this move into the mainstream, often quite abruptly? What about their work appeals to the studios? Of course, there are a variety of reasons, depending on the project and the producers involved. It might be worth following one filmmaker’s career up to the transition to see if there are any clues.

A recent example of this trend is the box-office hit Thor: Ragnarok (released November 3), in the Marvel universe, owned by Walt Disney Studios. Its director, New Zealander Taika Waititi, had directed a handful of modestly budgeted films in his native country. The most successful of those, Boy (2010) made $8.6 million worldwide. After a month in release, Thor will cross $800 million this coming weekend, if not before, and will ultimately gross more than 100 times as much as Boy.

Every filmmaker takes his or her own path before making this leap into blockbuster projects. Waititi did not set out with the ambition to direct a superhero movie with an absurdly high budget. But his career was so full of luck early on that it hardly could have gone better if he had planned it. If you sought a model path to blockbuster fame, you could do no better than to imitate him.

Start by getting nominated for an Oscar

Waititi was actually preparing for a career as a painter, but he was also doing a lot of performing: stand-comedy and film and television acting, perhaps most notably as one of the young flatmates in Roger Sarkies’ 1999 classic, Scarfies. His first brush with superhero movies came with a small role in Green Lantern, 2011. He also, however, made some short amateur films for the 48-Hour film project in Wellington. (Possibly I saw one of them, since I attended the program of shorts during my first visit to Wellington in 2003.) That led to his first professional film, the 11-minute Two Cars, One Night (above).

Virtually all indies made in New Zealand are funded by the New Zealand Film Commission, and in this case the NZFC’s Short Film Fund financed Two Cars. In January, 2004 it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, with which Waititi soon became closely linked. It’s available on YouTube, but be prepared to pay close attention if you hope to understand the thick, rural Kiwi dialect of the charming non-professional child actors. (Waititi’s Wikipedia entry has a good rundown of his television and other work as well as his films.)

The film got nominated for a best live-action short Oscar, and although it didn’t win that, it picked up prizes from the Berlin, AFI, Hamburg, Oberhausen, and other festivals, as well as the New Zealand Film and TV Awards. In fact, the short effectively drove Waititi into filmmaking, as he described in a 2007 interview.

I spent years doing visual arts, doing painting and photography, and throughout that whole time I was acting quite a lot in theater and New Zealand film and television. But for that whole time I wasn’t really sure which one of those artforms I wanted to concentrate on, and eventually just started tinkering around with writing little short films. I made one short film which ended up doing really well, and then suddenly I was propelled into this job as a filmmaker. But actually I didn’t want to be a filmmaker, I just wanted to make short films to try it out! I still don’t really think I’m a filmmaker.

Perhaps not then, but the idea must be quite plausible to him by now.

Get support from the Sundance Institute ASAP

The short and its Oscar nomination launched Waititi’s move into feature filmmaking. In 2005 it was announced that Waititi had been accepted into the Sundance Directors and Screenwriters labs to develop A Little Like Love, which later became his first feature, Eagle vs. Shark.

It was really good for getting my feature made, because I kinda got fast-tracked in the funding process. In New Zealand, the only way of getting a movie done is through the Film Commission, the government agency that funds everything. So I got nominated for the Oscar in March 2005, I wrote the screenplay for Eagle vs Shark in May, then we went to the Sundance Lab in June, got funding from the Film Commission in August, and we were shooting in October.

In January, 2007, Eagle vs. Shark premiered at Sundance. It got a small release in the USA. Having followed filmmaking in New Zealand during work on my book The Frodo Franchise, I saw it here in Madison in a nearly empty theater.

Asked in the same interview about his experiences in the Sundance Directors and Screenwriters labs, Waititi replied:

It was just totally amazing, totally amazing! I think the biggest thing I took away from the lab was finding the tone for the film. In the marketing, it’s going to be presented as a comedy, and I think that’s where a lot of the problems will lie. Even in the criticism of the film, people don’t get that it’s not pure comedy.

The power of the Sundance Institute in supporting first feature films and in others ways promoting independent production worldwide is surprisingly little known. Most obviously the labs have aided the development of American indies like Miranda July’s Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005), as well as supporting Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash (2014) through the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program. The Institute’s impact goes beyond the USA. The first film made in Saudi Arabia, Haifaa Al Mansour’s Wadjda (2012), also was aided by the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program. Sundance’s website emphasizes that the grants and participation in labs is not just for a single film:

With more than 9,000 playwrights, composers, digital media artists, and filmmakers served through Institute programs over the last 35 years, the Sundance community of independent creators is more far-reaching and vibrant than ever before.

If you have been selected for any Institute lab program or festival, you are a member of this community. Sundance alumni receive support throughout their careers, including access to tools, resources and advice as well as artist gatherings and more. Alumni are also encouraged to actively contribute to the Institute’s creative community and to our mission to discover and develop work from new artists.

Waititi’s second feature, Boy, which premiered in January, 2010, carries the credit, “Developed With The Assistance Of Sundance Institute Feature Film Program.” What We Do in the Shadows, co-directed with comedy partner Jemaine Clement, premiered there in January, 2014, though without a credit to Sundance, but his most recent independent feature, Hunt for the Wilderpeople (January, 2016) gave “Special Thanks” to the Sundance Institute.

Asked about Sundance in 2016, when Hunt for the Wilderpeople had just premiered, he declared,

I’ve got a good relationship with them, I love coming here, and I do think that this festival suits my films rather than most of the festivals I’ve been to. I’m not going to Cannes, you know.

Waititi has taken his membership in this exclusive group seriously. In 2015, Sundance created the Native Filmmakers Lab, aimed at supporting Native American and other Indigenous filmmakers. Such support had been a policy in choosing filmmakers to participate in labs up to that point, and Waititi is mentioned as one of past participants. He also is listed as the only individual among a list of major institutions contributing to the Sundance Institute Native American and Indigenous Program:

The Sundance Institute Native American and Indigenous Program is supported by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, Surdna Foundation, Time Warner Foundation, Ford Foundation, Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, SAGindie, Comcast-NBCUniversal, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Embassy of Australia, Indigenous Media Initiatives, Taika Waititi, and Pacific Islanders in Communications.

Taika Waititi’s father was a member of the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui group of the Mãori people, and his mother was a Russian Jew. Waititi used the name Taika Cohen in his early years as an actor.

Live in Wellington, New Zealand

Part of Waititi’s luck consisted of starting his filmmaking career just as Peter Jackson and his team had transformed filmmaking in New Zealand by building up the state-of-the-art production and post-production facilities needed to made The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003). Peter Jackson, Richard Taylor, and Jamie Selkirk, the co-owners of The Stone Street Studios, Weta Workshop, and Weta Digital, offered services by these firms at cost to New Zealand filmmakers; Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh did the same with The Film Unit (later Park Road Post), a lab with sound-mixing and editing facilities. Indeed, it was the only lab for developing film in New Zealand.

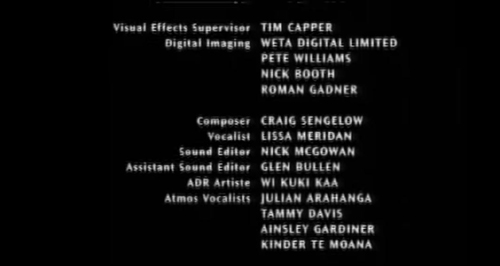

From the start, Waititi could take advantage of this large support system. The credits for Two Cars, One Night (above) include Weta Digital for the special effects and The Film Unit for post-production. The credits of the 2005 short version of What We Do in the Shadows thanked Selkirk and Park Road Post, as well as Peter Jackson, who offered undisclosed further support. Beasts of the Southern Wild credits three companies for its special effects, including Weta Digital for the wild-pig episode and Park Road Post for sound-mixing, along with “Very Special Thanks” to the Sundance Institute.”

Having toured those companies in 2003 and 2004, I can state that few indie filmmakers have had access to such sophisticated facilities.

Make some good, eccentric films

Waititi’s first film to capture wide attention was Boy, based loosely on his experiences growing up in a village on the upper east coast of New Zealand’s north island. The director played the young protagonist’s irresponsible father, a comically incompetent gang leader who had deserted his family and returns home to dig up some stolen money he and his pals have buried in an enormous field–without marking where it is. He strives to be a good father, mostly by showing off, as when he tries to casually leap into his car through the window and ends up in a struggle that embarrasses Boy in front of his young friends (above).

It’s a film that brought the blend of poignancy and offbeat humor that Waititi had established in Eagle vs. Shark to maturity.

He followed it with a very different film, What We Do in the Shadows (2014), a mockumentary about three vampire flatmates living in Wellington. (The reference in Thor: Ragnarok to a three-pronged spear for killing multiple vampires is to the main characters of Shadows.) Here the poignancy is gone and the humor pushed to extremes in a fashion that recalls the Monty Python team. In fact, it’s similar to the silly humor of Thor.

Finally, Hunt for the Wilderpeople, a tale of a rebellious foster child going on the lam with his foster “uncle” in the wilds of New Zealand, ultimately made somewhat less money internationally than the other two but had an enthusiastic critical response in the US. There was some Oscar buzz surrounding it, though no nominations resulted. It was, however, a huge success at home, becoming the highest-grossing New Zealand film ever, taking that title away from Boy, which had taken it from the classic Once Were Warriors (1994). It also won best film, director, actor, supporting actress, and supporting actor at the New Zealand Film and TV Awards. Sam Neill’s participation in this film led to his cameo in Thor: Ragnarock.

Coming into the mid 2010s, Waititi had built a solid career as an independent maker of likable, entertaining, skillfully made–and funny– films.

Get tapped for a blockbuster

How and why did Marvel choose Waititi? One might suspect that it was because he already had a Disney connection. When Moana was in pre-production, they brought in many people native to Polynesia to help with planning and design. (Little-known fact: New Zealand is part of Polynesia.) Waititi was brought aboard and wrote a first draft of the script, most of which was altered in later drafts.

When asked if the Moana work had anything to do with the Marvel invitation, however, Waititi responded,

Well, they had not heard of the Disney thing so I know that wasn’t part of it. They have a record making out there and exciting choices and I think what they said to me was, “We want it to be funny and try a whole new tack. We love your work and do you think you can fit in with this?”

Waititi got the call from Marvel in 2015, when he was editing Hunt for the Wilderpeople. USA Today interviewed him in early 2016, when the film premiered.

“They were looking for comedy directors,” he says. “They had seen What We Do in the Shadows and Boy. They especially liked Boy.”

The result was exactly what the Marvel people were after, since the largely positive reviews have invariably cited the humorous, even self-parodic tone of the film. In interviews, Waititi has often spoken of the scene in which Thor and the Hulk have a fight and then sit down to talk about their feelings (top). He wanted to add it because it was the sort of thing that never happens in superhero movies. The Marvel people seem to have liked it. An excerpt provided the tag ending for the first official trailer.

Upstage your actors

I would wager that fans know more about what Taika Waititi looks like than they do about most of the other blockbuster directors mentioned above. He already enjoyed something of a fan base from his earlier films, largely the cult following of What We Do in the Shadows. He remains an actor, playing a major role in some of his own films (Boy, What We Do in the Shadows) and a minor one in others. He’s been a stand-up comic, so he can keep the patter going in interviews and fan-convention panels.

In July, he stole the Thor: Ragnarok Hall H panel at Comic-Con, cracking up the big stars on the panel and getting more laughs from the audience than all of them put together. Waititi’s public persona makes him resemble a character in one of his own films.

Indeed, he again played a supporting character in Thor: Ragnarok, though not exactly in persona proper: Korg, the fighter made of stone. Waititi did both the motion capture and the voice for Korg, and I found the first scene between him and Thor to be the funniest in the whole film.

Even before the release of the film, Waititi quickly gained a reputation for his eccentric clothing preferences. He wore a matching pineapple-print shirt and shorts to the Comic-Con panel (seen in two of the above images). Ava DuVernay was widely quoted as calling Waititi the “best-dressed helmer” in the entertainment world, including in The Hollywood Reporter‘s story on how the director has become a “fashion superhero.” Maybe Waititi is not yet as recognizable to the public as the stars in his film are, but that may not last long. On the day Thor: Ragnarok was released, GQ profiled him, with several photos in different outfits, declaring that he “drips with cool.”

Waititi does cool things that appeal to fans. To raise the money to release Boy in the North American market, he started a Kickstarter campaign with a goal of $90,000 and raised $110,796. He directed one of the popular series of comic Air New Zealand safety announcements based on The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, “The Most Epic Safety Video Ever Made,” with himself playing the Gandalf-like wizard (see bottom). He has 262 thousand followers on twitter and tweets frequently. (This does not count the many unofficial pages like TaikaWaititi Fashion, with 978 followers.)

One-for-them, one-for-me respectability

Once admired indie directors start making blockbusters, they often stress that it is a way of getting smaller budgets for more personal projects of the sort that made them admired to begin with. The generation of movie brats, such as Francis Ford Coppola, established this notion of trade-offs with the big studios.

Perhaps as successfully as anyone in Hollywood, Christopher Nolan has shown quite clearly that such trade-offs can work. Once Memento (2000) made his reputation, he followed it with one mid-budget film, Insomnia (2002) and reached the heights of superhero-dom with Batman Begins. The pattern of alternating personal and one-for-them films is evident from the budgets and worldwide grosses of his subsequent films–although he has become so popular that most studios would happily settle for his “one-for-me” grosses:

Memento (2000, reported budget $9 milion; worldwide about $40 million), Insomnia (2002, reported budget $46 million; worldwide $113 million), Batman Begins (2005, reported budget $150 million; worldwide $375 million), The Prestige (2006, reported budget $40 million; worldwide $110 million), The Dark Knight (2008, reported budget $185 million; worldwide, $1. 005 billion), Inception (2010, reported budget $160 million; worldwide $825 million), The Dark Knight Rises (2012, reported budget $250 million; worldwide $1.085 billion), Interstellar (2014, reported budget $165 million; worldwide $675 million), and Dunkirk (2017, reported budget $100 million, worldwide $525 million, with an Oscar-season re-release announced).

Waititi has invoked this notion of returning to his indie roots at intervals. In 2015 We’re Wolves, a sequel to What We Do in the Shadows, was announced, again to be co-directed by Jemaine Clement. Presumably, however, that project was put on hold, but not abandoned, for Thor. He has other scripts in the drawer and in one interview says, “I’m excited to go back and do those, and then I’d like to come back and do something else here. You know, a one-for-them, one-for-you kind of scenario.”

He has specifically said he would be up for another Thor film:

“I would like to come back and work with Marvel any time, because I think they’re a fantastic studio, and we had a great time working together,” Waititi told RadioTimes.com. “And they were very supportive of me, and my vision.

“They kind of gave me a lot of free reign [sic], but also had a lot of ideas as well. A very collaborative company.”

Specifically, he went on, “I’d love to do another Thor film, because I feel like I’ve established a really great thing with these guys, and friendship.

“And I don’t really like any of the other characters.”

The question is, will Hollywood let him go, at least for now?