Archive for the 'Festivals' Category

Taika Waititi: The very model of a modern movie-maker

Thor: Ragnarock (2017).

Kristin here:

Not every independent filmmaker secretly longs to direct a big Hollywood blockbuster. Jim Jarmusch made a name for himself 33 years ago with Stranger than Paradise (1984) and won well-deserved praise for Paterson last year. Like other independent directors, Hal Harley turned from filmmaking to streaming television, directing episodes of Red Oaks (2015-2017) for Amazon.

Still, in recent decades the big studios have picked young directors of independent films or low-budget genre ones to leap right into big-budget blockbusters, and those directors have taken the plunge. Doug Liman’s Go (1999) was one of the quintessential indie films of its decade, but his next feature was The Bourne Identity (2002). Colin Trevorrow’s modest first feature Safety Not Guaranteed (2012, FilmDistrict) led straight to Jurassic World (2015, Universal); Gareth Edwards’ low-budget Monsters (2010, Magnolia) was directly followed by Godzilla (2014, Sony/Columbia) and Rogue One (2016, Buena Vista); and Josh Trank went from a $12 million budget for Chronicle (2012, Fox) to ten times that for the $120 million Fantastic Four (2015, Fox).

Something similar happens occasionally with foreign directors. Tomas Alfredson went from the original Swedish version of Let the Right One In (2008, Magnolia) to Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy (2011), and the Norwegian team Joachim Ronning and Espen Sandberg, after making Bandidas (2006, a French import released by Fox) and Kon-Tiki (2012, a Norwegian import released by The Weinstein Company) were hired to do Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales (2017, Walt Disney Pictures) and the upcoming Maleficent 2.

Recently women have followed this pattern as well: Patty Jenkins, going from Monster (2003, Newmarket Films) via a long stint in television to Wonder Woman (2017, Warner Bros.), and Ava DuVernay, from two early indie features and Selma (2014, Paramount), again via television, to A Wrinkle in Time (forthcoming 2018, Walt Disney Pictures).

Some of these directors have made the transition smoothly and successfully and some have not. Perhaps the most spectacular success has been that of Christopher Nolan, who went from Memento (2000) via Insomnia (2002) to Batman Begins (2005) and far beyond. But more about him later.

Why have indie filmmakers been able to make this move into the mainstream, often quite abruptly? What about their work appeals to the studios? Of course, there are a variety of reasons, depending on the project and the producers involved. It might be worth following one filmmaker’s career up to the transition to see if there are any clues.

A recent example of this trend is the box-office hit Thor: Ragnarok (released November 3), in the Marvel universe, owned by Walt Disney Studios. Its director, New Zealander Taika Waititi, had directed a handful of modestly budgeted films in his native country. The most successful of those, Boy (2010) made $8.6 million worldwide. After a month in release, Thor will cross $800 million this coming weekend, if not before, and will ultimately gross more than 100 times as much as Boy.

Every filmmaker takes his or her own path before making this leap into blockbuster projects. Waititi did not set out with the ambition to direct a superhero movie with an absurdly high budget. But his career was so full of luck early on that it hardly could have gone better if he had planned it. If you sought a model path to blockbuster fame, you could do no better than to imitate him.

Start by getting nominated for an Oscar

Waititi was actually preparing for a career as a painter, but he was also doing a lot of performing: stand-comedy and film and television acting, perhaps most notably as one of the young flatmates in Roger Sarkies’ 1999 classic, Scarfies. His first brush with superhero movies came with a small role in Green Lantern, 2011. He also, however, made some short amateur films for the 48-Hour film project in Wellington. (Possibly I saw one of them, since I attended the program of shorts during my first visit to Wellington in 2003.) That led to his first professional film, the 11-minute Two Cars, One Night (above).

Virtually all indies made in New Zealand are funded by the New Zealand Film Commission, and in this case the NZFC’s Short Film Fund financed Two Cars. In January, 2004 it premiered at the Sundance Film Festival, with which Waititi soon became closely linked. It’s available on YouTube, but be prepared to pay close attention if you hope to understand the thick, rural Kiwi dialect of the charming non-professional child actors. (Waititi’s Wikipedia entry has a good rundown of his television and other work as well as his films.)

The film got nominated for a best live-action short Oscar, and although it didn’t win that, it picked up prizes from the Berlin, AFI, Hamburg, Oberhausen, and other festivals, as well as the New Zealand Film and TV Awards. In fact, the short effectively drove Waititi into filmmaking, as he described in a 2007 interview.

I spent years doing visual arts, doing painting and photography, and throughout that whole time I was acting quite a lot in theater and New Zealand film and television. But for that whole time I wasn’t really sure which one of those artforms I wanted to concentrate on, and eventually just started tinkering around with writing little short films. I made one short film which ended up doing really well, and then suddenly I was propelled into this job as a filmmaker. But actually I didn’t want to be a filmmaker, I just wanted to make short films to try it out! I still don’t really think I’m a filmmaker.

Perhaps not then, but the idea must be quite plausible to him by now.

Get support from the Sundance Institute ASAP

The short and its Oscar nomination launched Waititi’s move into feature filmmaking. In 2005 it was announced that Waititi had been accepted into the Sundance Directors and Screenwriters labs to develop A Little Like Love, which later became his first feature, Eagle vs. Shark.

It was really good for getting my feature made, because I kinda got fast-tracked in the funding process. In New Zealand, the only way of getting a movie done is through the Film Commission, the government agency that funds everything. So I got nominated for the Oscar in March 2005, I wrote the screenplay for Eagle vs Shark in May, then we went to the Sundance Lab in June, got funding from the Film Commission in August, and we were shooting in October.

In January, 2007, Eagle vs. Shark premiered at Sundance. It got a small release in the USA. Having followed filmmaking in New Zealand during work on my book The Frodo Franchise, I saw it here in Madison in a nearly empty theater.

Asked in the same interview about his experiences in the Sundance Directors and Screenwriters labs, Waititi replied:

It was just totally amazing, totally amazing! I think the biggest thing I took away from the lab was finding the tone for the film. In the marketing, it’s going to be presented as a comedy, and I think that’s where a lot of the problems will lie. Even in the criticism of the film, people don’t get that it’s not pure comedy.

The power of the Sundance Institute in supporting first feature films and in others ways promoting independent production worldwide is surprisingly little known. Most obviously the labs have aided the development of American indies like Miranda July’s Me and You and Everyone We Know (2005), as well as supporting Damien Chazelle’s Whiplash (2014) through the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program. The Institute’s impact goes beyond the USA. The first film made in Saudi Arabia, Haifaa Al Mansour’s Wadjda (2012), also was aided by the Sundance Institute Feature Film Program. Sundance’s website emphasizes that the grants and participation in labs is not just for a single film:

With more than 9,000 playwrights, composers, digital media artists, and filmmakers served through Institute programs over the last 35 years, the Sundance community of independent creators is more far-reaching and vibrant than ever before.

If you have been selected for any Institute lab program or festival, you are a member of this community. Sundance alumni receive support throughout their careers, including access to tools, resources and advice as well as artist gatherings and more. Alumni are also encouraged to actively contribute to the Institute’s creative community and to our mission to discover and develop work from new artists.

Waititi’s second feature, Boy, which premiered in January, 2010, carries the credit, “Developed With The Assistance Of Sundance Institute Feature Film Program.” What We Do in the Shadows, co-directed with comedy partner Jemaine Clement, premiered there in January, 2014, though without a credit to Sundance, but his most recent independent feature, Hunt for the Wilderpeople (January, 2016) gave “Special Thanks” to the Sundance Institute.

Asked about Sundance in 2016, when Hunt for the Wilderpeople had just premiered, he declared,

I’ve got a good relationship with them, I love coming here, and I do think that this festival suits my films rather than most of the festivals I’ve been to. I’m not going to Cannes, you know.

Waititi has taken his membership in this exclusive group seriously. In 2015, Sundance created the Native Filmmakers Lab, aimed at supporting Native American and other Indigenous filmmakers. Such support had been a policy in choosing filmmakers to participate in labs up to that point, and Waititi is mentioned as one of past participants. He also is listed as the only individual among a list of major institutions contributing to the Sundance Institute Native American and Indigenous Program:

The Sundance Institute Native American and Indigenous Program is supported by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation, Surdna Foundation, Time Warner Foundation, Ford Foundation, Native Arts and Cultures Foundation, SAGindie, Comcast-NBCUniversal, the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, the Embassy of Australia, Indigenous Media Initiatives, Taika Waititi, and Pacific Islanders in Communications.

Taika Waititi’s father was a member of the Te Whānau-ā-Apanui group of the Mãori people, and his mother was a Russian Jew. Waititi used the name Taika Cohen in his early years as an actor.

Live in Wellington, New Zealand

Part of Waititi’s luck consisted of starting his filmmaking career just as Peter Jackson and his team had transformed filmmaking in New Zealand by building up the state-of-the-art production and post-production facilities needed to made The Lord of the Rings (2001-2003). Peter Jackson, Richard Taylor, and Jamie Selkirk, the co-owners of The Stone Street Studios, Weta Workshop, and Weta Digital, offered services by these firms at cost to New Zealand filmmakers; Peter Jackson and Fran Walsh did the same with The Film Unit (later Park Road Post), a lab with sound-mixing and editing facilities. Indeed, it was the only lab for developing film in New Zealand.

From the start, Waititi could take advantage of this large support system. The credits for Two Cars, One Night (above) include Weta Digital for the special effects and The Film Unit for post-production. The credits of the 2005 short version of What We Do in the Shadows thanked Selkirk and Park Road Post, as well as Peter Jackson, who offered undisclosed further support. Beasts of the Southern Wild credits three companies for its special effects, including Weta Digital for the wild-pig episode and Park Road Post for sound-mixing, along with “Very Special Thanks” to the Sundance Institute.”

Having toured those companies in 2003 and 2004, I can state that few indie filmmakers have had access to such sophisticated facilities.

Make some good, eccentric films

Waititi’s first film to capture wide attention was Boy, based loosely on his experiences growing up in a village on the upper east coast of New Zealand’s north island. The director played the young protagonist’s irresponsible father, a comically incompetent gang leader who had deserted his family and returns home to dig up some stolen money he and his pals have buried in an enormous field–without marking where it is. He strives to be a good father, mostly by showing off, as when he tries to casually leap into his car through the window and ends up in a struggle that embarrasses Boy in front of his young friends (above).

It’s a film that brought the blend of poignancy and offbeat humor that Waititi had established in Eagle vs. Shark to maturity.

He followed it with a very different film, What We Do in the Shadows (2014), a mockumentary about three vampire flatmates living in Wellington. (The reference in Thor: Ragnarok to a three-pronged spear for killing multiple vampires is to the main characters of Shadows.) Here the poignancy is gone and the humor pushed to extremes in a fashion that recalls the Monty Python team. In fact, it’s similar to the silly humor of Thor.

Finally, Hunt for the Wilderpeople, a tale of a rebellious foster child going on the lam with his foster “uncle” in the wilds of New Zealand, ultimately made somewhat less money internationally than the other two but had an enthusiastic critical response in the US. There was some Oscar buzz surrounding it, though no nominations resulted. It was, however, a huge success at home, becoming the highest-grossing New Zealand film ever, taking that title away from Boy, which had taken it from the classic Once Were Warriors (1994). It also won best film, director, actor, supporting actress, and supporting actor at the New Zealand Film and TV Awards. Sam Neill’s participation in this film led to his cameo in Thor: Ragnarock.

Coming into the mid 2010s, Waititi had built a solid career as an independent maker of likable, entertaining, skillfully made–and funny– films.

Get tapped for a blockbuster

How and why did Marvel choose Waititi? One might suspect that it was because he already had a Disney connection. When Moana was in pre-production, they brought in many people native to Polynesia to help with planning and design. (Little-known fact: New Zealand is part of Polynesia.) Waititi was brought aboard and wrote a first draft of the script, most of which was altered in later drafts.

When asked if the Moana work had anything to do with the Marvel invitation, however, Waititi responded,

Well, they had not heard of the Disney thing so I know that wasn’t part of it. They have a record making out there and exciting choices and I think what they said to me was, “We want it to be funny and try a whole new tack. We love your work and do you think you can fit in with this?”

Waititi got the call from Marvel in 2015, when he was editing Hunt for the Wilderpeople. USA Today interviewed him in early 2016, when the film premiered.

“They were looking for comedy directors,” he says. “They had seen What We Do in the Shadows and Boy. They especially liked Boy.”

The result was exactly what the Marvel people were after, since the largely positive reviews have invariably cited the humorous, even self-parodic tone of the film. In interviews, Waititi has often spoken of the scene in which Thor and the Hulk have a fight and then sit down to talk about their feelings (top). He wanted to add it because it was the sort of thing that never happens in superhero movies. The Marvel people seem to have liked it. An excerpt provided the tag ending for the first official trailer.

Upstage your actors

I would wager that fans know more about what Taika Waititi looks like than they do about most of the other blockbuster directors mentioned above. He already enjoyed something of a fan base from his earlier films, largely the cult following of What We Do in the Shadows. He remains an actor, playing a major role in some of his own films (Boy, What We Do in the Shadows) and a minor one in others. He’s been a stand-up comic, so he can keep the patter going in interviews and fan-convention panels.

In July, he stole the Thor: Ragnarok Hall H panel at Comic-Con, cracking up the big stars on the panel and getting more laughs from the audience than all of them put together. Waititi’s public persona makes him resemble a character in one of his own films.

Indeed, he again played a supporting character in Thor: Ragnarok, though not exactly in persona proper: Korg, the fighter made of stone. Waititi did both the motion capture and the voice for Korg, and I found the first scene between him and Thor to be the funniest in the whole film.

Even before the release of the film, Waititi quickly gained a reputation for his eccentric clothing preferences. He wore a matching pineapple-print shirt and shorts to the Comic-Con panel (seen in two of the above images). Ava DuVernay was widely quoted as calling Waititi the “best-dressed helmer” in the entertainment world, including in The Hollywood Reporter‘s story on how the director has become a “fashion superhero.” Maybe Waititi is not yet as recognizable to the public as the stars in his film are, but that may not last long. On the day Thor: Ragnarok was released, GQ profiled him, with several photos in different outfits, declaring that he “drips with cool.”

Waititi does cool things that appeal to fans. To raise the money to release Boy in the North American market, he started a Kickstarter campaign with a goal of $90,000 and raised $110,796. He directed one of the popular series of comic Air New Zealand safety announcements based on The Lord of the Rings and The Hobbit, “The Most Epic Safety Video Ever Made,” with himself playing the Gandalf-like wizard (see bottom). He has 262 thousand followers on twitter and tweets frequently. (This does not count the many unofficial pages like TaikaWaititi Fashion, with 978 followers.)

One-for-them, one-for-me respectability

Once admired indie directors start making blockbusters, they often stress that it is a way of getting smaller budgets for more personal projects of the sort that made them admired to begin with. The generation of movie brats, such as Francis Ford Coppola, established this notion of trade-offs with the big studios.

Perhaps as successfully as anyone in Hollywood, Christopher Nolan has shown quite clearly that such trade-offs can work. Once Memento (2000) made his reputation, he followed it with one mid-budget film, Insomnia (2002) and reached the heights of superhero-dom with Batman Begins. The pattern of alternating personal and one-for-them films is evident from the budgets and worldwide grosses of his subsequent films–although he has become so popular that most studios would happily settle for his “one-for-me” grosses:

Memento (2000, reported budget $9 milion; worldwide about $40 million), Insomnia (2002, reported budget $46 million; worldwide $113 million), Batman Begins (2005, reported budget $150 million; worldwide $375 million), The Prestige (2006, reported budget $40 million; worldwide $110 million), The Dark Knight (2008, reported budget $185 million; worldwide, $1. 005 billion), Inception (2010, reported budget $160 million; worldwide $825 million), The Dark Knight Rises (2012, reported budget $250 million; worldwide $1.085 billion), Interstellar (2014, reported budget $165 million; worldwide $675 million), and Dunkirk (2017, reported budget $100 million, worldwide $525 million, with an Oscar-season re-release announced).

Waititi has invoked this notion of returning to his indie roots at intervals. In 2015 We’re Wolves, a sequel to What We Do in the Shadows, was announced, again to be co-directed by Jemaine Clement. Presumably, however, that project was put on hold, but not abandoned, for Thor. He has other scripts in the drawer and in one interview says, “I’m excited to go back and do those, and then I’d like to come back and do something else here. You know, a one-for-them, one-for-you kind of scenario.”

He has specifically said he would be up for another Thor film:

“I would like to come back and work with Marvel any time, because I think they’re a fantastic studio, and we had a great time working together,” Waititi told RadioTimes.com. “And they were very supportive of me, and my vision.

“They kind of gave me a lot of free reign [sic], but also had a lot of ideas as well. A very collaborative company.”

Specifically, he went on, “I’d love to do another Thor film, because I feel like I’ve established a really great thing with these guys, and friendship.

“And I don’t really like any of the other characters.”

The question is, will Hollywood let him go, at least for now?

Waititi’s first decade or so of filmmaking suggests some reasons why he was approached to make a $180 million epic. The Marvel producers were specifically looking for comedy. Comedies are supposedly harder to sell abroad, but put funny material into a big sci-fi film, and it can do just fine overseas. Many of the other indie filmmakers who made this transition started with genre films–low budget crime or sci-fi films.

Moreover, the Marvel producers who approached him were also willing to give him a free rein, so they were presumably trusting and open to someone whose work they admired. Not all producers would be so lenient. It no doubt helped that in this case, the studio was specifically looking for something original and funny–in short, different from the stolid reputation that the Thor films had gained among critics and viewers alike.

The Most Epic Safety Video Ever Made (c. 2014)

Dreyer, and more, in Houghton

La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc (1928).

DB here:

Erin Smith, of Michigan Technological University, distinguished herself during her years at Madison as a grad student in both English and Film. She’s moved more fully into media studies and production, including documentary work. When she invited me to visit 41 North Film Festival this coming weekend, how could I refuse?

There’s a lot going on, most elaborately a screening of Dreyer’s La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc with orchestral and choral accompaniment.

I’ve never attended a performance of Richard Einhorn’s score, so this should be quite something. (The Criterion DVD version of the film offers it as optional accompaniment.) In addition, there are several other films showing over the weekend. You can go here for the full schedule, which includes one of our recent favorites, Varda’s Faces/Places.

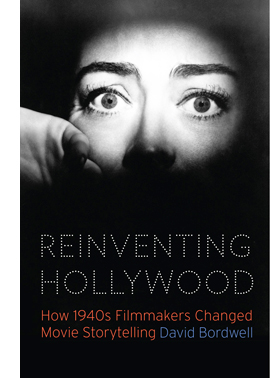

While Kristin and I are there, I’ll be doing a lecture on Dreyer and another talk based on Reinventing Hollywood.

My first book was a little guide to La Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, and my second book was a survey of Dreyer’s films. I’ve returned to him sporadically since then, and I’ve had occasion to rethink his role in film history–especially in light of my and others’ research on silent cinema. (For example, “The Dreyer Generation,” “Dreyer Re-Reconsidered,” “Nordisk and the Tableau Aesthetic,” and this blog entry on Criterion’s Master of the House release.)

Dreyer remains for me an impressive, enigmatic figure. He was sensitive to the changing styles of cinematic expression from the 1920s to the 1960s, and yet he went his own way. His early silents were au courant with trends in European filmmaking, especially kammerspiel. Yet Jeanne was one of the wildest movies of the era, a hallucinatory blend of Expressionism, French Impressionism, and Soviet Montage. It still seems to me resolutely unique, which partly secures its timelessness.

After the no less weird Vampyr (1932), Dreyer’s films seemed old-fashioned in their pacing; even Danish critics called Day of Wrath (1943) sluggish. Yet as things played out his “archaic” style in the sound era looks more and more prophetic. He said he learned from Antonioni, but Ordet (1955) and Gertrud (1964; below) go far beyond the deliberate pacing of European films of his day and look forward to Straub/Huillet and Béla Tarr.

Was he the first director of “slow cinema”? I now see him as integrating principles of the “theatrical” cinema of the 1910s–a style he rejected in his youth–into the modern sound cinema, in effect showing the continued viability of the approach, while pushing it to extremes. Just like what he did with editing and shot design in Jeanne, come to think of it. For such a quiet guy, he was pretty bold.

Michigan Tech is located in gorgeous country (the UP, as we midwesterners call it). Kristin and I look forward to our road trip, accompanied by old Orson Welles radio shows. We thank Erin and her colleagues for inviting us!

A view of Houghton, MI, from the Portage waterway.

Thrill me!

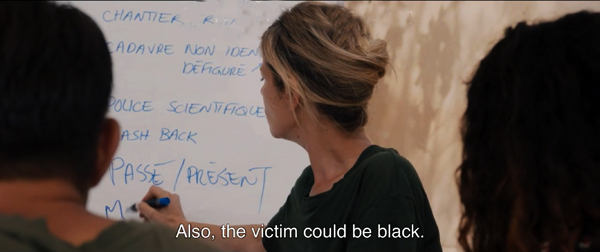

Based on a True Story (Polanski, 2017).

DB here:

Three examples, journalists say, and you’ve got a trend. Well, I have more than three, and probably the trend has been evident to you for some time. Still, I want to analyze it a bit more than I’ve seen done elsewhere.

That trend is the high-end thriller movie. This genre, or mega-genre, seems to have been all over Cannes this year.

A great many deals were announced for thrillers starting, shooting, or completed. Coming up is Paul Schrader’s First Reformed, “centering on members of a church who are troubled by the loss of their loved ones.” There’s Sarah Daggar-Nickson’s A Vigilante, with Olivia Wilde as a woman avenging victims of domestic abuse. There’s Ridley Scott’s All the Money in the World, about the kidnapping of J. Paul Getty III. There’s Lars von Trier’s serial-killer exercise The House that Jack Built. There’s as well 24 Hours to Live, Escape from Praetoria, Close, In Love and Hate, and Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile, featuring Zac Efron as Ted Bundy. Claire Denis, who has made two thrillers, is planning another. Not of all these may see completion, but there’s a trend here.

Then there were the movies actually screened: Based on a True Story (Assayas/ Polanski), Good Time (the Safdie brothers), L’Amant Double (Ozon), The Killing of a Sacred Deer (Lanthimos), The Merciless (Byun), You Were Never Really Here (Ramsay), and Wind River (Sheridan), among others. There was an alien-invasion thriller (Kiyoshi Kurosawa’s Before We Vanish), a political thriller (The Summit), and even an “agricultural thriller” (Bloody Milk). The creative writing class assembled in Cantet’s The Workshop is evidently defined through diversity debates, but what is the group collectively writing? A thriller.

Thrillers seldom come up high in any year’s global box-office grosses. Yet they’re a central part of international film culture and the business it’s attached to. Few other genres are as pervasive and prestigious. What’s going on here?

A prestigious mega-genre

Vertigo (Hitchcock, 1958).

Thriller has been an ambiguous term throughout the twentieth century. For British readers and writers around World War I, the label covered both detective stories and stories of action and adventure, usually centered on spies and criminal masterminds.

By the mid-1930s the term became even more expansive, coming to include as well stories of crime or impending menace centered on home life (the “domestic thriller”) or a maladjusted loner (the “psychological thriller”). The prototypes were the British novel Before the Fact (1932) and the play Gas Light (aka Gaslight and Angel Street, 1938).

While the detective story organizes its plot around an investigation, and aims to whet the reader’s curiosity about a solution to the puzzle, in the domestic or psychological thriller, suspense outranks curiosity. We’re no longer wondering whodunit; often, we know. We ask: Who will escape, and how will the menace be stopped? Accordingly, unlike the detective story or the tale of the lone adventurer, the thriller might put us in the mind of the miscreant or the potential victim.

In the 1940s, the prototypical film thrillers were directed by Hitchcock. I’ve argued elsewhere that he mapped out several possibilities with Foreign Correspondent and Saboteur (spy thrillers) Rebecca and Suspicion (domestic suspense), and Shadow of a Doubt (domestic suspense plus psychological probing). Today, I suppose core-candidates of this strain of thrillers, on both page and screen, would be The Ghost Writer, Gone Girl, and The Girl on the Train.

In the 1940s, as psychological and domestic thrillers became more common, critics and practitioners started to distinguish detective stories from thrillers. In thinking about suspense, people noticed that the distinctive emotional responses depend on different ranges of knowledge about the narrative factors at play. With the classic detective story, Holmesian or hard-boiled, we’re limited to what the detective and sidekicks know. By contrast, a classic thriller may limit us to the threatened characters or to the perpetrator. If a thriller plot does emphasize the investigation we’re likely to get an alternating attachment to cop and crook, as in M, Silence of the Lambs, and Heat.

Today, I think, most people have reverted to a catchall conception of the thriller, including detective stories in the mix. That’s partly because pure detective plotting, fictional or factual, remains surprisingly popular in books, TV, and podcasts like S-Town. The police procedural, fitted out with cops who have their own problems, is virtually the default for many mysteries. So when Cannes coverage refers to thrillers, investigation tales like Campion’s Top of the Lake are included.

In addition, “impure” detective plotting can exploit thriller values. Films primarily focused on an investigation, but emphasizing suspense and danger, can achieve the ominous tension of thrillers, as Se7en and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo do. More generally, any film involving crime, such as a heist or a political cover-up, could, if it’s structured for suspense and plot twists, be counted as part of the genre.

Yet tales of police detection aren’t currently very central to film, I think. Their role, Jeff Smith suggests, has been somewhat filled by the reporter-as-detective, in Spotlight, Kill the Messenger, and others. Straight-up suspense plots are even more common, as in the classic victim-in-danger plots of The Shallows, Don’t Breathe, and Get Out. Tales of psychological and domestic suspense coalesced as a major trend in Hollywood during the 1940s. It became so important that I devoted a chapter to it in my upcoming book, Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling. (You can get an earlier version of that argument here.)

By referring to “high-tone” thrillers, I simply want to indicate that major directors, writers, and stars have long worked in this broad genre. In the old days we had Lang, Preminger, Siodmak, Minnelli, Cukor, John Sturges, Delmer Daves, Cavalcanti, and many others. Today, as then, there are plenty of mid-range or low-end thrillers (though not as many as there are horror films), but a great many prestigious filmmakers have tried their hand: Soderbergh (Haywire, Side Effects), Scorsese (Cape Fear, Shutter Island), Ridley Scott (Hannibal), Tony Scott (Enemy of the State, Déja vu), Coppola (The Conversation), Bigelow (Blue Steel, Strange Days), Singer (The Usual Suspects), the Coen brothers (Blood Simple, No Country for Old Men et al.), Shyamalan (The Sixth Sense, Split), Nolan (Memento et al.), Lee (Son of Sam, Clockers, Inside Man), Spielberg (Jaws, Minority Report), Lumet (Before the Devil Knows You’re Dead), Cronenberg (A History of Violence, Eastern Promises), Tarantino (Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction, Jackie Brown), Kubrick (Eyes Wide Shut), and even Woody Allen (Match Point, Crimes and Misdemeanors). Brian De Palma and David Fincher work almost exclusively in the genre.

And that list is just American. You can add Almodóvar, Assayas, Besson, Denis, Polanski, Figgis, Frears, Mendes, Refn, Villeneuve, Cuarón, Haneke, Cantet, Tarr, Gareth Jones, and a host of Asians like Kurosawa Kiyoshi, Park Chan-wook, Bong Joon-ho, and Johnnie To. I can’t think of another genre that has attracted more excellent directors. The more high-end talents who tackle the genre, the more attractive it becomes to other filmmakers.

Signing on to a tradition

Creepy (Kurosawa, 2016).

If you’re a writer or a director, and you’re not making a superhero film or a franchise entry, you really have only a few choices nowadays: drama, comedy, thriller. The thriller is a tempting option on several grounds.

For one thing, there’s what Patrick Anderson’s book title announces: The Triumph of the Thriller. Anderson’s book is problematic in some of its historical claims, but there’s no denying the great presence of crime, mystery, and suspense fiction on bestseller lists since the 1970s. Anderson points out that the fat bestsellers of the 1950s, the Michener and Alan Drury sagas, were replaced by bulky crime novels like Gorky Park and Red Dragon. As I write this, nine of the top fifteen books on the Times hardcover-fiction list are either detective stories or suspense stories. A thriller movie has a decent chance to be popular.

This process really started in the Forties. Then there emerged bestselling works laying out the options still dominant today. Erle Stanley Gardner provided the legal mystery before Grisham; Ellery Queen gave us the classic puzzle; Mickey Spillane provided hard-boiled investigation; and Mary Roberts Rinehart, Mignon G. Eberhart, and Daphne du Maurier ruled over the woman-in-peril thriller. Alongside them, there flourished psychological and domestic thrillers—not as hugely popular but strong and critically favored. Much suspense writing was by women, notably Dorothy B. Hughes, Margaret Millar, and Patricia Highsmith, but Cornell Woolrich and John Franklin Bardin contributed too.

I’d argue that mystery-mongering won further prestige in the Forties thanks to Hollywood films. Detective movies gained respectability with The Maltese Falcon, Laura, Crossfire, and other films. Well-made items like Double Indemnity, Mildred Pierce, The Ministry of Fear, The Stranger, The Spiral Staircase, The Window, The Reckless Moment, The Asphalt Jungle, and the work of Hitchcock showed still wider possibilities. Many of these films helped make people think better of the literary genre too. Since then, the suspense thriller has never left Hollywood, with outstanding examples being Hitchcock’s 1950s-1970s films, as well as The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Seconds (1966), Wait Until Dark (1967), Rosemary’s Baby (1968), The Parallax View (1974), Chinatown (1974), and Three Days of the Condor (1975), and onward.

Which is to say there’s an impressive tradition. That’s a second factor pushing current directors to thrillers. It does no harm to have your film compared to the biggest name of all. Google the phrase “this Hitchcockian thriller” and you’ll get over three thousand results. Science fiction and fantasy don’t yet, I think, have quite this level of prestige, though those genres’ premises can be deployed in thriller plotting, as in Source Code, Inception, and Ex Machina.

Since psychological thrillers in particular depend on intricate plotting and moderately complex characters, those elements can infuse the project with a sense of classical gravitas. Side Effects allowed Soderbergh to display a crisp economy that had been kept out of both gonzo projects like Schizopolis and slicker ones like Erin Brockovich.

Ben Hecht noted that mystery stories are ingenious because they have to be. You get points for cleverness in a way other genres don’t permit. Because the thriller is all about misdirection, the filmmaker can explore unusual stratagems of narration that might be out of keeping in other genres. In the Forties, mystery-driven plots encouraged writers to try replay flashbacks that clarified obscure situations. Mildred Pierce is probably the most elaborate example. Up to the present, a thriller lets filmmakers test their skill handling twists and reveals. Since most such films are a kind of game with the viewer, the audience becomes aware of the filmmakers’ skill to an unusual degree.

Thrillers also tend to be stylistic exercises to a greater extent than other genres do. You can display restraint, as Kurosawa Kiyoshi does with his fastidious long-take long shots, or you can go wild., as with De Palma’s split-screens and diopter compositions. Hitchcock was, again, a model with his high-impact montage sequences and florid moments like the retreating shot down the staircase during one murder in Frenzy.

Would any other genre tolerate the showoffish track through a coffeepot’s handle that Fincher throws in our face in Panic Room? It would be distracting in a drama and wouldn’t be goofy enough for a comedy.

Yet in a thriller, the shot not only goes Hitchcock one better but becomes a flamboyant riff in a movie about punishing the rich with a dose of forced confinement. More recently, the German one-take film Victoria exemplifies the look-ma-no-hands treatment of thriller conventions. Would that movie be as buzzworthy if it had been shot and cut in the orthodox way?

Fairly cheap thrills

Non-Stop (Collet-Serra, 2014). Production budget: $50 million. Worldwide gross: $222 million.

The triumph of the movie thriller benefits from an enormous amount of good source material. The Europeans have long recognized the enduring appeal of English and American novels; recall that Visconti turned a James M. Cain novel into Ossessione. After the 40s rise of the thriller, Highsmith became a particular favorite (Clément, Chabrol, Wenders). Ruth Rendell has been mined too, by Chabrol (two times), Ozon, Almodóvar, and Claude Miller. Chabrol, who grew up reading série noire novels, adapted 40s works by Ellery Queen and Charlotte Armstrong, as well as books by Ed McBain and Stanley Ellin. Truffaut tried Woolrich twice and Charles Williams once. Costa-Gavras offered his version of Westlake’s The Ax, while Tavernier and Corneau picked up Jim Thompson. At Cannes, Ozon’s L’Amant double derives from a Joyce Carol Oates thriller the author calls “a prose movie.”

Of course the French have looked closer to home as well, with many versions of Simenon novels by Renoir, Duvivier, Carné, Chabrol (inevitably), Leconte, and others. The trend continues with this year’s Assayas/Polanski adaptation of the French psychological thriller Based on a True Story.

In all such cases, writers and directors get a twofer: a well-crafted plot from a master or mistress of the genre, and praise for having the good taste to disseminate the downmarket genre most favored by intellectuals.

Another advantage of the thriller is economy. There are big-budget thrillers like Inception, Spectre, and the Mission: Impossible franchise. But the thriller can also flourish in the realm of the American mid-budget picture. Recently The Accountant, The Girl on the Train, and The Maze Runner all had budgets under $50 million. Putting aside marketing costs, which are seldom divulged, consider estimated production costs versus worldwide grosses of these top-20 thrillers of the last seven years. The figures come from Box Office Mojo.

Taken 2 $45 million $376 million

Gone Girl $61 million $369 million

Now You See Me $75 million $351 million

Lucy $40 million $463 million

Kingsman: The Secret Service $81 million $414 million

Then there are the low-budget bonanzas.

The Shallows $17 million $119 million

Don’t Breathe $9.9 million $157 million

The Purge: Election Year $10 million $118 million

Split $9 million $276 million

Get Out $4.5 million $241 million

Of course budgets of foreign thrillers are more constrained, and I don’t have figures for typical examples. Still, overseas filmmakers tackling the genre have an advantage over their peers in other genres. Thrillers are exportable to the lucrative American market, twice over.

First, a thriller can be an art-house breakout. Volver, The Lives of Others, and The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo (2009) all scored over $10 million at the US box office, a very high number for a foreign-language film. Asian titles that get into the market have done reasonably well, and enjoy long lives on video and streaming. The Handmaiden and Train to Busan, both from South Korea, doubled the theatrical take of non-thrillers Toni Erdmann and Julieta, as well as that of American indies like Certain Women and The Hollers. Elsewhere, thrillers comprised two of the three big arthouse hits in the UK during the first four months of this year: The Handmaiden, a con-artist movie in its essence, and Elle, a lacquered woman-in-peril shocker.

Second, a solid import can be remade with prominent actors, as Wages of Fear and The Secret in Their Eyes were. Probably the most high-profile recent example was The Departed, a redo of Hong Kong’s Infernal Affairs. Sometimes the director of the original is allowed to shoot the remake, as happened with The Vanishing, Loft, and Hitchcock’s The Man Who Knew Too Much.

Even if the remake doesn’t get produced, just the purchase of remake rights is a big plus. I remember one European writer-director telling me that he earned more from selling the remake rights to his breakout film than he did from the original. He was also offered to direct the remake, but he declined, explaining: “If someone else does it, and it’s good, that’s good for the original. If it’s bad, people will praise the original as better.” And by making a specialty hit, the screenwriter or director gets on the Hollywood radar. If you can direct an effective thriller, American opportunities can open up, as Asian directors have discovered.

Thrillers attract performers. Actors want to do offbeat things, and between their big-paycheck parts they may find the conflicted, often duplicitous characters of psychological thrillers challenging roles. For Side Effects Soderbergh rounded up name performers Jude Law, Rooney Mara, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Channing Tatum. The Coens are skillful at working with stars like Brad Pitt (Burn after Reading). The rise of the thriller has given actors good Academy Award chances too. Here are some I noticed:

Jane Fonda (Klute), Jodie Foster (Silence of the Lambs), Frances McDormand (Fargo), Natalie Portman (Black Swan), Brie Larson (Room), Anjelica Huston (Prizzi’s Honor), Kim Basinger (L.A. Confidential), Rachel Weisz (The Constant Gardener), Jeremy Irons (Reversal of Fortune), Denzel Washington (Training Day), Sean Penn (Mystic River), Sean Connery (The Untouchables), Tommy Lee Jones (The Fugitive), Kevin Spacey (The Usual Suspects), Benicio Del Toro (Traffic), Tim Robbins (Mystic River), Javier Bardem (No Country for Old Men), Mark Rylance (Bridge of Spies).

Finally, there’s deniability. Because of the genre’s literary prestige, because of the tony talent behind and before the camera, and because of the genre’s ability to cross cultures, the thriller can be….more than a thriller. Just as critics hail every good mystery or spy novel as not just a thriller but literature, so we cinephiles have no problem considering Hitchcock films and Coen films and their ilk as potential masterpieces. On the most influential list of the fifty best films we find The Godfather and Godfather II, Mulholland Dr., Taxi Driver, and Psycho. At the very top is Vertigo, not only a superb thriller but purportedly the greatest film ever made.

I worried that perhaps this whole argument was an exercise in confirmation bias–finding what favors your hunch and ignoring counterexamples. Looking through lists of top releases, I was obliged to recognize that thrillers aren’t as highly rewarded in film culture as serious dramas (Manchester by the Sea, Moonlight, Paterson, Jackie, The Fits). But I also kept finding recent films I’d forgotten to mention (Hell or High Water, The Green Room) or didn’t know of (Karyn Kusama’s The Invitation, Mike Flanigan’s Hush). They supported the minimal intuition that thrillers play an important role in both independent and mainstream moviemaking.

And not just on the fringes or the second tier. Perhaps because film is such an accessible art, all movies are fair game for the canon. As a fan of thrillers in all variants, from genteel cozies and had-I-but-known tales to hard-boiled noir and warped psychodramas, I’m glad that we cinephiles have no problem ranking members of this mega-genre up there with the official classics of Bergman, Fellini, and Antonioni (who built three movies around thriller premises). Of course other genres yield outstanding films as well. But we should be proud that cinema can offer works that aren’t merely “good of their kind” but good of any kind. For that reason alone, ambitious filmmakers are likely to persist in thrill-seeking.

Thanks to Kristin, Jeff Smith, and David Koepp for comments that helped me in this entry. Ben Hecht’s remark comes from Philip K. Scheuer, “A Town Called Hollywood,” Los Angeles Times (30 June 1940), C3.

You can get a fair sense of what the Brits thought a thriller was from a book by Basil Hogarth (great name), Writing Thrillers for Profit: A Practical Guide (London: Black, 1936). A very good survey of the mega-genre is Martin Rubin’s Thrillers (Cambridge University Press, 1999). David Koepp, screenwriter of Panic Room, has thoughts on the thriller film elsewhere on this blog.

Having just finished Delphine de Vigan’s Based on a True Story, I can see what attracted Assayas and Polanski. The film (which I haven’t yet seen) could be a nifty intersection of thriller conventions and the art-cinema aesthetic. As a gynocentric suspenser, though, the book doesn’t seem to me up to, say, Laura Lippman’s Life Sentences, a more densely constructed tale of a memoirist’s mind. And de Vigan’s central gimmick goes back quite a ways; to mention its predecessors would constitute a spoiler. For more on women’s suspense fiction, see “Deadlier than the male (novelist).” For more on Truffaut’s debt to the Hitchcock thriller, try this.

The Workshop (Cantet, 2017).

Three women of Cannes: A guest entry by Kelley Conway

Visages Villages (2017).

DB here:

Kelley Conway, friend and colleague here at Madison, has just made her first trip to the Cannes festival. All her adventures won’t fit on one entry, so she focuses this report on encounters with three outstanding women in French film culture: Agnès Varda, Laetitia Dosch, and Nathalie Coste-Cerdan. Kelley is the author of several books and articles on French film. Her recent book is on Varda, which we reviewed here. She wrote for us earlier this year on La La Land, and last year on French films at Vancouver.

Sneakers or heels?

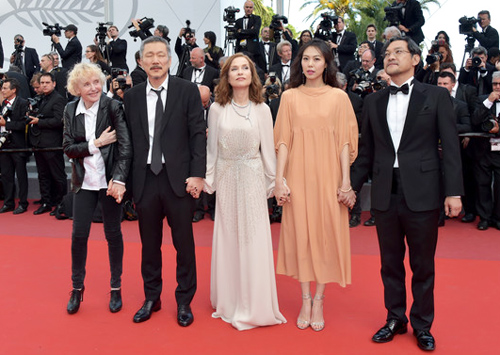

On the red carpet, Claire’s Camera creatives: Claire Denis, Hong Sangsoo, Isabelle Huppert, Kim Minheet, and Jeong Jinyoung.

The red carpet, replaced every day, is the epicenter. Standing on the edge, you’re mesmerized by the ritualized movement of humans across it. First, ordinary invitation-holders cross the carpet and move up the stairs and into the Grand Théâtre Lumière.

Once the mortals have taken their seats, the actors, directors, and L’Oréal models arrive. Women dressed in evening gowns pause and pose for the photographers while fans watch hungrily from beyond barriers and heavy security.

There are different styles of traversing the carpet. Dior-clad Rihanna took her time, striking vampy poses worthy of Theda Bara and apparently savoring every minute of the experience. No-nonsense legend Claire Denis moved briskly toward the stairs wearing a simple black pantsuit. Agnès Varda and JR, the photographer/muralist and co-director of Visages Villages, clowned it up.

Sometimes, in a gesture that is oddly moving, the director and actors who worked together on a film link arms, pose collectively, and stride the red carpet as one.

The videographers track the stars right into the theater. Once you get in and find a seat, you can follow other celebrities’ carpet progress thanks to a live feed. We watch them sit down and then we stand up, treating them to a standing ovation before and after the projection.

The videographers track the stars right into the theater. Once you get in and find a seat, you can follow other celebrities’ carpet progress thanks to a live feed. We watch them sit down and then we stand up, treating them to a standing ovation before and after the projection.

The whole thing seemed a little overwrought and absurd until I saw tears in eyes of Hong Sang-soo, Agnès Varda, and Laetitia Dosch, an actress you will soon adore. Cannes is a huge promotional machine and a herculean feat of event management, but flashes of humanity shine through.

Even bystanders are subject to a dress code. For afternoon screenings, I was allowed to wear my sneakers. For the evening screenings of the films in competition, heels are de rigueur for women. Men are allowed to retain their sneakers, but I set aside this injustice and contemplate other elements of the Cannes experience.

The mise-en-scène of women on the red carpet can make Cannes appear fatally retrograde; one must look to the screen and behind the scenes for evidence of the modern woman. Let’s take a look at three women (and there are many more, of course) who deserve a kind of scrutiny that exceeds the red carpet défilé: Agnès Varda, Laetitia Dosch, and Nathalie Coste-Cerdan. What have these women, a director, an actress, and an educational executive, contributed to Cannes?

The Director: Through the Eyes of Varda and JR in Visages Villages

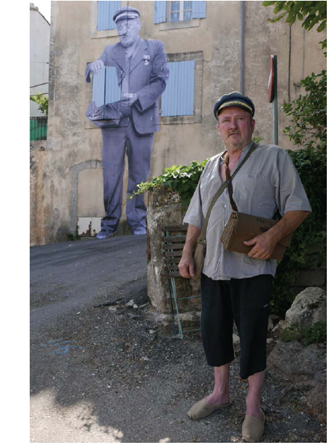

Visages Villages, which just won the Golden Eye Documentary prize at Cannes, is ostensibly a portrait of several small French villages. But it’s mainly a chronicle of a journey, an artistic collaboration, and a friendship between 30-something JR and 80-something Agnès Varda. JR is the hugely talented street artist and Instagram sensation, well known for his photographs and installations, notably his transformation of I.M. Pei’s glass pyramid at the Louvre in 2015.

As with Varda’s Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse and Les Plages d’Agnès, we accompany the filmmaker, this time with her new collaborator in their “photo truck,” as they travel through France, gleaning ideas and experiences. We meet retired coal miners, cheese makers, factory workers, a mail carrier, a waitress, and the stalwart wives of three dockers in Le Havre, and we watch Varda and JR create and display epic photographs of them. The resulting images render ordinary humans and their remote communities extraordinary.

As with Varda’s Les Glaneurs et la glaneuse and Les Plages d’Agnès, we accompany the filmmaker, this time with her new collaborator in their “photo truck,” as they travel through France, gleaning ideas and experiences. We meet retired coal miners, cheese makers, factory workers, a mail carrier, a waitress, and the stalwart wives of three dockers in Le Havre, and we watch Varda and JR create and display epic photographs of them. The resulting images render ordinary humans and their remote communities extraordinary.

As in her past work, Varda urges us to take a good look at people and places we have previously overlooked, exercising her extraordinary gift for making us care about strangers. But the film is not merely an empathetic social document on rural France. Visages Villages affirms the allure of art and art-making, or rather the “power of the imagination,” as Varda describes the focus of their film. We witness the various stages in the duo’s collaboration: planning, considerable horsing around, execution, and discussion of the outcome.

The film reminds me of Chronique d’un été (1961), which also sought to document the lives of ordinary people while chronicling a collaboration (between Jean Rouch, Edgar Morin and their friends). In Visages Villages the result of the collaboration is, typically, the creation of a monumental photograph of a person placed in an unlikely setting: the wall of a decaying building in an isolated village, a container at the port of Le Havre, a barn on a lonely farm. As Varda did with Mona in Vagabond, the lonely single mother of Documenteur, and the widows of Noirmoutier, Varda and JR imbue their subjects with dignity, while maintaining a respectful distance.

Visages Villages models a way of seeing and a way of being. JR and Varda laboriously plan and execute an installation consisting of a photo Agnès made in 1954 of the late photographer Guy Bourdin. JR and his crew construct a scaffold and paste the photo on the side of a massive bunker from W.W.II that had fallen from a cliff onto a Normandy beach.

We watch the whole thing come together beautifully via time lapse, only to learn that it was washed away by the tide within 24 hours. Instead of grieving the short life of the work of art, the pair move on, ready for their next adventure, which is how Varda has lived her whole life, fearlessly seeking new projects, curiosity and generosity intact.The human eyes and the spectre of Jean-Luc Godard are important motifs and Varda finds a way to merge them. A visit to Varda’s ophthalmologist, where she receives an injection to treat her macular degeneration, results in JR pasting a close-up of her eye on the cylindrical body of a gas truck.

JR propels Varda through the Louvre in a wheelchair, paying homage to Godard’s Bande à part and reminding us that looking at art has always been one of Varda’s passions. Near the end of the film, JR consoles Varda in Rolle after her old friend Godard callously stands her up, by finally offering her (but not us!) a glimpse of his eyes liberated from his habitual sunglasses.

In the hands of anyone else, this portrait of provincial people and an unlikely friendship might have resulted something thin and inconsequential. Instead, it’s a poetic window into the process of creation, an ode to the elevation of the ordinary, and a primer on the way to live.

The Actress: Jeune femme (aka Montparnasse Bienvenue, directed by Léonor Sérraille with Laetitia Dosch)

Two moments of stunning direct address bookend this beautifully acted, droll and moving film about a 31-year old woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown. The film opens with a scene of Paula (Laetitia Dosch) pounding furiously, first with her fists and then with her head, on the door of her unresponsive ex. While getting bandaged at a clinic, she rants extravagantly in direct address: “I was everything to him and now I’m nothing.” The final shot of the film reveals Paula staring directly at the camera again, this time calm and resolute, restored to a position of strength and hard-earned wisdom. Jeune femme is about a woman who comes to Paris to track down her ex, only to find a better version of herself.

I spoke with actress Laetitia Dosch about what it was like to create the role of Paula. Dosch worked in French boulevard theater and attended the prestigious two-year “Classe Libre” program of the acting school Cours Florent before enrolling at the Swiss National Conservatory, where she received a classical and avant-garde formation. Director Léonor Sérraille had recently won a screenwriting grant from the CNC and was looking for an actress to play the role of Paula when she saw footage of Dosch on YouTube. She wrote Dosch a letter and they soon began working together. Sérraille was busy during the day, but the two women found time to meet nearly every evening for six weeks. They discussed the character, explored Paris together, and saw films.

Dosch’s explosive performance in Jeune Femme, which is both highly verbal and often idiosyncratically physical, might lead one to assume that significant improvisation occurred during the shoot, but no. Sérraille’s script was meticulously written, even “écrit au millimetre,” Dosch said, which she appreciated, because it helped her “figure out how the character thinks.” The film charts the transformation of a slightly manic, spurned woman into a person who realizes she’s better off without her older, famous, photographer boyfriend, for whom she was a muse.

Dosch’s explosive performance in Jeune Femme, which is both highly verbal and often idiosyncratically physical, might lead one to assume that significant improvisation occurred during the shoot, but no. Sérraille’s script was meticulously written, even “écrit au millimetre,” Dosch said, which she appreciated, because it helped her “figure out how the character thinks.” The film charts the transformation of a slightly manic, spurned woman into a person who realizes she’s better off without her older, famous, photographer boyfriend, for whom she was a muse.

Our flawed protagonist leads a precarious existence. Essentially homeless at the beginning of the film, she benefits from the generosity of a lovely woman she meets on the subway by failing to correct the woman’s mistaken impression that Paula is her long-lost childhood friend from Lyon. She confiscates her ex-boyfriend’s cat and eventually abandons it at a vet clinic. But she cobbles together a life, babysitting a depressed little girl whose existence she brightens with cotton candy and aria singing; making repeated attempts to reconnect with her estranged mother; selling lingerie at a mall in Montparnasse, and making new friends, notably a single dad from Senegal with a degree in economics who works as a security guard at the mall. When circumstances force her to make some big decisions, she surprises us. As Dosch described her character, “This is the story of a muse who stopped being a muse, or rather became her own muse.”

It’s worth contemplating Jeune femme’s conditions of production. The crew was comprised mainly of women, most of whom graduated from France’s prestigious national film school, Fémis. The film was awarded an avance sur recettes by the CNC (Centre National du cinéma et de l’image animée), which afforded Sérraille the time to write the screenplay. Institutions such as Fémis and the CNC are the backbone of France’s celebrated cinema ecosystem. A portion of each film ticket sold goes to the CNC, which in turn, distributes the funds to nourish the entire system of film education, production, and exhibition.

Here, more than anywhere else in the world, state resources flow in the support of screenwriters, directors, and even exhibitors who make and show films that might not exist or thrive without aid. In 2016, for example, the French art et essai (art house) exhibition sector accounted for 22.4% of all film attendance in France and benefited from nearly 15 million euros in aid from the CNC. French films retain a relatively high local market share. They attract 35.8% of admissions, while 52.9 % go to American releases.

The Education Executive: Nathalie Coste-Cerdan

Fémis is an important part of the system. Nathalie Coste-Cerdan, until recently the Director of Canal +, is now the General Director of Fémis. Created as IDHEC in 1945, Fémis was restructured and renamed in 1986. The school, which graduates fifty students each year, is funded by the CNC and supervised by the French Ministry of Culture and Media and the Ministry of Higher Education. The current president of the school is Raoul Peck, who directed most recently I am Not Your Negro. Prestigious grads include Noémi Lvovsky, Arnaud Desplechin, François Ozon, Céline Sciamma, Marina de Van, and Rebecca Zlotowski.

Because the school is supported by the CNC, French students pay next to nothing (433 euros per year) for this four-year education. Foreigners must pay 10,670 euros per year, but this is still a bargain by American standards. Students must have a B.A. or M.A. before entering one of the six main programs at Fémis, which are directing, producing, screenwriting, sound, cinematography, and editing.

The school keeps adding programs. A new two-year program trains people who want to work in distribution and exhibition. Another new program, La Résidence, trains recent high school graduates in film production for one year and is aimed at enhancing diversity at the school. Yet another new program, also lasting one year, was created to train students in the writing of television series because “ambitious television series are not so common in France,” admitted Coste-Cerdan.

I attended a panel organized by the CNC at its beachfront headquarters at the Cannes Film Festival to hear about film education in France and elsewhere. Representatives from Fémis, Ciné-Fabrique in Lyon, and films schools in Poland and Argentina compared their schools’ structures, fees, curricular goals, and, especially, their efforts to support international exchanges. Coste-Cerdan asserted, “It’s impossible to be a national film school today without being international.” In line with this trend, Fémis accords 10% of its spots to foreign students, creates special programs for foreign students, and runs exchange programs with film schools in other countries.

Seeking to “encourage international co-productions, be on the cutting edge of the industry, and open students’ minds to other points of view,” the school sends each and every Fémis student abroad to study in a partner institution. Fémis students study screenwriting at Columbia University, documentary film at the Beijing Film Academy in China, or sound design at VGIK in Russia. Fémis sends students to, and accepts students from, CalArts, Tokyo University of the Arts, INSAS in Bruxelles, the Universidad del Cinea in Buenos Aires, and the Korean Academy of Film Arts in Seoul, among others.

One Fémis program, linked with the Filmakademie of Baden-Württemberg, offers a one-year course designed for aspiring producers. The training takes place in France, Germany, and England and includes sessions at the Cannes, Berlin, and Angers film festivals.

Fémis also offers yet another innovative tactic, a three-week program for European documentary filmmakers who wish to develop a documentary film based on archival material. Here, aspiring documentary makers get help with re-writing, the preparation of a dossier for financiers, tips for dealing with producers and broadcasters, and pitching skills.

The results have been encouraging. The “Gulf Summer University” at Fémis has had luck attracting nine students from the Gulf region for its 5-week training program. Recently, a young Chinese woman from the Beijing Film Academy came to Paris and made a “poetic, philosophical” documentary about the Chinese community in Belleville. Coste-Cerdan characterized the exchange programs as, among other things, an exercise in “soft power,” designed to export the ideals of French film system elsewhere and also to challenge French students by exposing them to other cultures.

Cannes is a mecca of glamour and an enforcer of hierarchies, of course, but it’s also a place where one can have a serious conversation about now to improve international film education. It’s a place where one can see comedies like Noah Baumbach’s The Meyerowitz Stories (New and Selected), which is really good, by the way, but also films like Abbas Kiarostami’s gorgeous 24 Frames and Karim Moussaoui’s En attendant les hirondelles, a superb Algerian film. It’s also a place where one can see director John Cameron Mitchell, whose How to Talk to Girls played at Cannes this year to mixed reviews, serve as DJ and perform with a punk band at the “Queer Party.” It’s also a place where a taxi driver raved about the dialogue in the films of Michel Audiard and color design in Pedro Almodóvar.

I’d like to come back here some day, but I want to wear my sneakers on the red carpet, even at night.

Thanks to Agnès Varda, Laetitia Dosch, Françoise Pams, Pierre-Emmanuel Lecerf, and Nathalie Coste-Cerdan for their kind cooperation.

The 1162 French film theaters categorized as art et essai received, on average, 12,820 euros each in 2016. See “La Réforme de l’art et essai,” Le Courrier art et essai, n. 256, May 2017, 12.

Red carpet photos by Zimbio and Pascal Le Segretain/Getty Images; Coste-Cerdan photo from Times Higher Education Supplement. Other photos by Kelley Conway.

P.S. 28 May 2017: Jeune Femme won the Caméra d’Or prize for best first film.