Archive for April 2011

Beyond praise 4: Even more DVD supplements that really tell you something

David Fincher, foreground left, lays out a scene for The Social Network

Kristin here:

Every year or so I write an entry on useful DVD supplements. These aren’t necessarily very recent ones, but items I’ve come across that actually reveal something interesting about the filmmaking process—as opposed to the litanies of mutual praise that making-ofs too often spend time on. For the three earlier entries, see here, here, and here.

These posts are aimed partly at fans, of course, but also offer suggestions to teachers who use Film Art concerning useful teaching tools to be found among the supplements.

Often the most elaborate DVD extras are those for big fantasy and science-fiction films. There’s certainly no shortage of clips and examples if you’re teaching special effects! The trouble is to find good supplements about the basic techniques of pre-production and filming. I’ve included some effects-heavy films in past entries, but I’m happy this time to have two dramas whose supplements don’t even mention special effects.

The Social Network (“Two-disc Collector’s Edition,” Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

As with many DVDs, the long, chronologically organized account of how the film was made is the least interesting of the supplements. But hang on, because the short, specialized ones that follow are terrific.

The feature-length documentary, “How Did They Ever Make a Movie of Facebook?” starts with pre-production, a section which is mildly interesting but basically uninformative. It then continues with four parts: “Boston,” “Andover,” and “Los Angeles,” and “The Lot.” The “Los Angeles” scene includes an excellent scene showing the camera on a dolly, rapidly tracking back in front of Eduardo (Andrew Garfield) as he hurries to confront Mark Zuckerberg (Jesse Eisenberg). This 92-minute making-of skips post-production and ends with a montage of self- and mutual congratulations.

I should add that there are moments during this film where the rehearsals and the exchanges between the actors and Fincher on set do reveal something about how performances are crafted. Someone who wanted to teach a unit on acting might find it helpful to pull out clips of these interesting moments and have students read David’s entry on the performances in the film.

Otherwise, save your 92 minutes and go straight to the “Additional Special Features.”

First is “Jeff Cronenweth and David Fincher on the Visuals.” At only 7 1/2 minutes, this is packed with good stuff. Cronenweth discusses why he and Fincher decided to go with Red HD cameras (below left) rather than the Vipers used for Zodiac and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. It well illustrates of what we talk about in Chapter 1 of the ninth edition of Film Art: technical decisions being made for aesthetic purposes. According to Cronenweth, digital cameras innately have greater depth of field than 35mm ones do, and the featurette explains how to manipulate depth of field in digital filmmaking in order to guide the attention of the viewer. Finally, there’s an enlightening example of how three cameras fastened together can take separate images that can be tiled into a long, panoramic space. The filmmakers can than create camera movements within that panorama, add lights, and otherwise manipulate the image in ways that will be imperceptible to the viewer.

“Angus Wall, Kirk Baxter, Ren Klyce on Post” is just as good if not better. It’s mostly about editing. About a minute in, Baxter, the editor, talks about how Fincher wanted him to conform to traditional rules of continuity editing, never crossing the axis of action. As he puts it, “We’re always doing basic film law, but it can just be done extremely rapidly.” In other words, the average shot length may be lower than in older Hollywood films, but the methods of handling space for clarity are still observed. One passage of this supplement shows the difficulty of keeping eyelines straight when shooting a group at a table (a topic we deal in Film Art using a simpler example from Bringing up Baby). Klyce, the sound designer, discusses being able to edit individual words from different takes to create exactly the dialogue the director wanted. He also points out that Fincher insisted that background noises be as loud as the dialogue being spoken by the principal characters present. That’s a pretty unconventional approach, as we mention in our sound chapter.

At several points in this supplement, the juxtaposition of two or more images in a black background helps illustrate the point, as in the frame at the top of this entry.

The innovative music in The Social Network has rightly drawn a great deal of attention, including an Oscar and other awards. It’s covered in “Trent Razor, Atticus Ross, David Fincher on the Score.” Again some of the concepts we lay out in Film Art show up here. The composers and director talk about how music affects the spectator’s expectations. They point out that variants of a key musical theme are used to connect three scenes (i.e., a musical motif links parts together to create a formal whole). That musical motif involves a slow, wistful piano tune played over a faintly ominous undercurrent of electronic tones. To indicate the progression across the film, the piano was recorded with the microphone at a different distance from the instrument each time, affecting its timbre.

“Swarmatron” is really an extension of the music supplement, this time focusing on a particular and eccentric musical instrument.

Finally, there’s a segment on the big night-club scene, “Ruby Skye VIP Room: Multi-angle Scene Breakdown,” which is about four minutes long. Multi-angle layouts of scenes juxtaposing the different camera angles within the frame have become fairly common on DVDs. Here, though, Kirk Baxter and Ren Klyce return to offer more insights into the post-production and how these disparate images and sounds were combined. This supplement is interactive, and one can choose which versions of the shots and sound to use. I didn’t try all possible combinations. Choosing “1) Composite view” and “2) Interviews” worked well, I thought.

Another Fincher film, Zodiac, has been discussed in our “Beyond praise” series. Evidently Fincher understands what makes for a useful supplement–at least when it comes to the ones that deal with specific aspect of filmmaking.

District 9 (“2-disc Edition,” Sony Pictures Home Entertainment)

To begin with, don’t bother with the three short “The Alien Agenda: A Filmmaker’s Log” films on the same disc as the feature. They’re perfunctory and uninformative, probably something produced for cable channels to run as publicity.

The good stuff is on the supplements disc. Which has previews on it. I expect previews before the film, but in front of the supplements?! Maybe I just haven’t noticed this before, but this is the first time I was actively annoyed by it. At least one can skip through them by pressing the “next” button three times.

The individual documentaries are pretty good of their type. “Metamorphosis: The Transformation of Wikus” focuses on the make-up designed for the main character, Wikus Van Der Merwe, in the portion of the film after he is infected by something that turns him into one of the aliens he has been trying to control. This is as straightforward and dramatic a demonstration of make-up as you’re likely to see.

A lot of the film’s acting involved improvising on camera, and “Innovation: The Acting and Improvisation of District 9” is an unusually interesting little supplement on acting. Again, teachers who want to teach an extensive unit on acting might want to use this. It creates a considerable contrast with the main Social Network making-of, where Aaron Sorkin states quite emphatically that there was no improvisation at all on his film.

“Conception and Design: Creating the World of District 9” goes into such topics as the design of the aliens’ weapons (below, top). It’s fairly typical of these sorts of supplements, but there is a discussion of how the space-ship design was consciously imitating the style of sci-fi films of the 1970s and 1980s. That is, Alien (1979) introduced the notion that space craft could be corroded and dingy(below, bottom)–as opposed to the squeaky-clean interiors of the ships in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968). Thus the idea of styles and genres having their own histories, which we bring up in Film Art, is exemplified.

“Alien Generation : The Visual Effects of District 9” has some interesting footage exemplifying the challenges of trying to shoot improvised acting with a hand-held camera while having a motion-capture camera filming the same action simultaneously. With both cameras, complete with separate small crews, move in unpredictable ways, they tend to get in each other’s way. There’s also a nice moment at the end when a technician shows off a rotating still camera on a tripod. It’s used to record the light coming from all directions, so that the digital effects can add in light that’s consistent with that on set.

The New World (New Line Home Entertainment)

Note: Both the theatrical version DVD and the “Extended Cut” one (which restores 35 minutes cut by Malick for the theatrical release and is also available in on Blu-ray) have the same supplements.

With all the anticipation building up around Terence Malick’s upcoming The Tree of Life, I wondered what a making-of for a Malick film would look like. Would the elusive Mr. Malick take part, or would he allow little or no behind-the-scenes footage?

Turns out he did not take part, but the makers of “Making The New World,” a one-hour supplement, took an imaginative approach by attaching themselves to the second unit. That’s the unit that typically films the action and landscape shots, scenes where the main actors are not delivering dialogue. In this case the unit had plenty of work to do. We see the filming of a fire at the fort, footage of the three ships sailing up the river in the marvelous opening scene, and a long battle between the Native Americans and colonists.

The documentary camera operators were allowed to tag along right behind or even in the midst of the cinematographer’s team, who clearly cooperated extensively. A lot of what we witness is actual filming, often glimpsed over the shoulders of assistants, still photographers, the second-unit assistant director, the fight choreographer, and others. (See below.)

I doubt very much of the coverage was planned in advance. The camera dodges around people who intrude unexpectedly into the foreground, and in a few cases the microphone is too far from what’s going on, and the filmmakers insert subtitles to let us know what was said. The interview footage clearly included anyone the documentarists could corral between takes, including various bit players, make-up people, the assistant director, just whoever was available. It comes as a shock when about half-way through Colin Farrell appears briefly to make a few remarks. In this brief interview with one of the Indian actors, people pass close by in the background, making noise that competes with what he says:

The result is a greater immersion in the filmmaking process than I’ve seen in any making-of. There’s no real attempt to explain any aspect of filmmaking–no voiceover narration, no superimposed titles apart from the ones identifying the people speaking.

Overall, this caught-on-the-fly footage gives the impression that any aspect of filmmaking can be interesting. So often the directors of supplements foreground the stars and try to inject drama into what is already a fascinating subject. Here there might be a plastic tarp being put over a camera during the rain or a camera assistant instructing extras on a ship to make sure that their water bottles aren’t in frame, and the supplement makers include it.

We do, of course, learn something about how Malick works. Experienced camera operators remark on how he doesn’t use artificial lighting, and we see shots of men ripping openings in thatched roofs to allow sunlight into a scene:

Christian Bale notes that Malick shoots 360 degrees around the space, so that crew members must be prepared to duck out of sight if he turns the camera their way. Others express surprise at the complete lack of storyboarding.

Being attached to the second unit also allowed the making-of team to show how the filmmakers cooperated with and included many Native Americans in the planning and execution of the film. It’s great to see American Indians not only pleased with the way their ancestors are being portrayed, but excited by being able to experience something of their ancestors’ way of life.

There’s a touching moment when Buck Woodard, a Native American advisor on the film, is being shown around the frame of an Indian dwelling by the production designer, Jack Fisk. Woodard looks around with a smile, and as Fisk moves off to the left, Woodard turns away from the camera and whispers almost inaudibly, “It’s just wonderful!”—clearly speaking to himself and not to Fisk or the microphone.

In short, this is a thoroughly ingratiating making-of—and how often do you see one of those?

One final note. Is it just me that’s getting annoyed by the time-lapse photography in supplements that are used to show lengthy actions like set-building or light-shifting really fast? That was kind of impressive for a while, but it’s a cliché by now. In The Social Network supplements the fast-motion is so fast that one can’t really see what’s going on. That sort of thing is cutesy, and it condescends to the viewer. (Even The New World supplements, which are much more casual, use this device once or twice.) I would like to see a set-building scene that actually shows something about how sets are built, not about how cool the supplement producers can make the process look.

The factors considered in these supplements tend to support David’s arguments in The Way Hollywood Tells It that there are basic continuities of style between traditional studio filmmaking and what some scholars have characterized as “post-classical” Hollywood.

The New World.

Arthouse suspense, in big and small doses

Le Quattro Volte.

DB here:

As happened last year, I had to flee Hong Kong for medical reasons. Beset by a wracking cough, I took off three days early and upon returning to Madison wound up in hospital. Current diagnosis: pneumonia. Duration of stay: six nights and counting. A drag. But I’m lucky: no disorderly orderlies, no homicidal doctors injecting me with mind-control drugs (“You will watch only Brett Ratner films for the rest of your life. Sleep, sleep…”). I’m taken care of by expert, calm, and good-natured people. Expect no less from the best city for men’s health and care.

So I’ve been tardy in writing this final HK blog. I just wanted to talk about two extraordinary films I saw in my final days and bring up a scrap of news for followers of Chinese film.

First, the news. Liu Jiayin, of Oxhide fame, was in Hong Kong briefly to accept an Asian Film Financing Forum award for her screenplay Clean and Bright. The other winner was Li Ruijun, for his project Where Is My Home? Liu was about to visit the US for screenings at Redcat, under the sponsorship of the tireless Bérénice Reynaud, and at Cinema Pacific in Portland. I had a chance to talk briefly with her just before she departed.

First, the news. Liu Jiayin, of Oxhide fame, was in Hong Kong briefly to accept an Asian Film Financing Forum award for her screenplay Clean and Bright. The other winner was Li Ruijun, for his project Where Is My Home? Liu was about to visit the US for screenings at Redcat, under the sponsorship of the tireless Bérénice Reynaud, and at Cinema Pacific in Portland. I had a chance to talk briefly with her just before she departed.

Regular readers of this blog know my admiration for Liu’s two Oxhide films. The good news is that she is at work on Oxhide III. She wouldn’t say much about it, except that she is still reworking the script, but it sounded quite far along. In addition, she hopes to shoot Clean and Bright, a more orthodox film about a family, fairly soon as well. Oxhide IV is also planned, with the series running up to perhaps eight installments.

For more on Oxhide, including purchase information for the DVD, check Kevin Lee’s dGenerate Films website.

Leaving us hanging

Too often we think of suspense as specific to certain genres, but it’s actually a fundamental resource of all storytelling. Creating expectations about an upcoming event, sharpening them, and delaying their fulfillment–all these strategies are basic, I think, to narrative experience in general. Although some plots emphasize suspense more than others, even most “character-centered” tales wouldn’t engage us without a dose of it.

True, sometimes there’s a sort of bait-and-switch, as when suspense is conjured up but eventually dissolved. Sooner or later we realize Godot isn’t going to show up, or that Anna in L’Avventura is likely not to be found. In those cases, suspense has led us to another terrain, usually thematic, in which we’re invited to consider something more significant than learning the outcome of events. (Sometimes, though, snuffing out suspense is just a sign of slack, or Slacker, storytelling.)

Suspense is usually associated with popular plotting, so many people expect Serious Films to be lacking in suspense. Which makes it all the more interesting that Iran, one of the most-favored nations on the festival circuit, has made something of a specialty of suspenseful art movies.

We don’t recognize often enough that Kiarostami’s early films are often structured as suspenseful quests, from the boy’s attempt to return his schoolmate’s notebook in Where Is the Friend’s Home? to the final shot of Through the Olive Trees. His scripts for other directors convey this quality even more clearly. The Key is almost Griffithian in showing how a four-year-old boy struggles to rescue his younger brother when they’re locked in a kitchen with a gas leak. The Journey (Safar) is positively Ruth Rendellian: A headstrong middle-class father leaving Tehran with his family forces another car off the road and flees the scene. Instead of resting at a summer retreat, he returns obsessively to the place of the accident to check the progress of the investigation: Will he give himself away? And it isn’t just Kiarostami. Look at the suspense structure in Makhmalbaf’s Moment of Innocence, or Reza Mir-Karimi’s The Child and the Soldier, or Panahi’s The Circle.

What gives Iranian suspense films their weight is partly the fact that they don’t rely so much on the old standbys (chases, stalkings, cliffhanging rescues) but rather on psychological maneuvers, carried out largely through dialogue. Characters in these movies tend to talk a lot, pushing their concerns forward with a stubbornness that we seldom see in other national cinemas. People stick up for themselves, and the suspense comes from a clash of testimonies, pleas, and self-justifications. But it also comes from a moral dimension. My earlier examples depend on our assessing what we ought to happen (the hero of the Journey should be punished) versus what we might want to happen (he should escape). Add a dash of mystery, as we have in Through the Olive Trees (what is Tehereh thinking?) and A Taste of Cherry (what is the job Mr. Badi is hiring for?), and you have artistically ambitious filmmaking that exploits some very traditional resources of the art form.

These resources were on display in Asgar Farhadi’s earlier About Elly, which I praised in these pages two years ago. Nader and Simin, A Separation has a comparable power to seize and hold our interest. A wife fails to get a divorce and leaves the household, which includes not only her husband Nader but his Alzheimer’s-addled father and their daughter Termeh. Without Simin to care for his father, Nader hires Razieh, a working-class woman who must bring her little girl with her. Soon the job overwhelms Razieh and, for reasons not disclosed till later, she goes missing. Nader and Termeh find the old man tied to the bed, unconscious.

For this early stretch of the film, the helper Razieh trembles on the verge of hysteria, and only later do we learn why. When she returns to the apartment, she confronts Nader’s wrath, which leads to yet another turning point, but one whose significance we realize only later. To complicate matters, Razieh’s hot-headed husband becomes furious with everyone. As in About Elly, a great deal turns on what characters know at one precise moment, and our memory of when they learned something can be as elusive as theirs. And as in Henry James’ novels, much of the action is registered through the reactions of onlookers, notably the pensive daughter Termeh (below), who turns out in the final scene to be as important as any other figure in the film.

The suspense builds on many levels: the progress of the divorce, the decline of the old man, the court case that involves Razieh’s place in the household (did she steal money?), and above all the responsibility for a death. Some of these lines of action are shown resolved; a crucial one remains suspended. And that does, as often happens, oblige us to think more broadly about the film’s treatment of parent/ child relationships. We are left with an exceptionally rich film, one reflecting on class differences, religious ones, and the effects of adult problems on the children around them. Suspense not only feeds our hunger for story; it can also tease us to moral reflection, and Nader and Simin does just that.

No suspense?

How much can you purge suspense from a movie? And if you play it down, what do you put in its place to hold our interest?

One answer to these questions comes in Michelangelo Frammartino’s Le Quattro Volte. It is one of those sedate observational pieces that covers a year in the life of a village, with not much discernible dialogue but lots of lovely landscape shots. It has a cyclical rather than linear structure, beginning and ending with smoldering wood turned into charcoal–itself a metaphor for the inevitable transmutations that govern plants, animals, and men. We follow an old goatherd who eventually dies; his goats pay homage by climbing precariously to his tiny home and occupying it. A young goat is born soon after the old man’s death. The townsfolk erect an enormous Christmas tree, which at the end of the holiday is chopped down into bits, which will in turn becomes charcoal. If Nader and Simin exists largely in medium-shot, here the extreme long-shot dominates. There are no psychological interactions or dramatic issues of the sort we find in Fahradi’s films. In the rustic spirit of Rouquier’s Farrebique, we get the sheer successiveness of things, the fact that life is one damned, or placid, moment after another.

So suspense can be replaced by sheer consecutiveness, but the task then becomes to make things interesting. Frammartino does so through careful framing, evocative sound, and crisp storytelling technique. The goats pick their way up to the old man’s hillside apartment; they jostle around inside; cut to a shot of the old man’s head as he lies dead; cut to the church, with people filing out as the bell tolls. In addition , you can find suspense at more micro-levels, working not at the level of plot action as a whole but rather within and across particular scenes. After the goatherd’s death, we see another kid born: this is familiar, even clichéd, the rhythm of nature. We follow the kid’s efforts to assimilate to the herd. But as winter comes, the kid strays off, becomes isolated, and ends up lost and shivering. We must assume that he dies. So much for the great cycle of life.

At a still more microscopic level comes the shot that everyone remembers from Le Quattro Volte. It’s so salient that critics who seldom notice imagery can’t help but mention it. I won’t describe it in detail, so as not spoil the surprises, but suffice it to say that it involves a church procession, some intransigent goats, a pickup truck, and a resourceful dog. Reminiscent of Tati or Suleiman, this long shot depends on ratcheting up our expectations about how several converging events might develop, onscreen or off, and then fulfilling those expectations in startling ways. We might call the result spatial suspense: How will this composition-in-time finally resolve itself?

We should, then, never underestimate the power of suspense, even in those films which might seem to forswear it. Melodrama or pastoral, any genre can find a way to excite us by asking what can come next.

Catching up: By leaving Hong Kong early I missed the second screening of The Turin Horse; my first impressions are here. Since I wrote that, I learned that Cinema Scope has published Robert Koehler’s sensitive appreciation of the film and his enlightening interview with the cinematographer Fred Kelemen.

Nader and Sinin, A Separation.

A matter of ‘Scope

Killer Constable.

DB here:

Like most cinephiles of my vintage, I love anamorphic widescreen, especially in its early years. Even though CinemaScope as a trademarked format is long gone, its aspect ratio of 2.35 or 2.40 to 1 became the standard, and we tend to call any widescreen film of those proportions a “‘Scope” production.

Nowadays many films are in ‘Scope; it’s sensed as a cool ratio. Too cool, actually: I’m not sure that Cop Out and The Hangover needed to be in ‘Scope. Things were quite different in Asian cinema during the 1960s and 1970s, where directors had to learn how to master and exploit the new acreage available to them. I was reminded of their problems, and some of their dazzling solutions, when I visited films that were part of two big retrospectives at the Hong Kong Film Festival this year.

The Shochiku touch

Festival goers tend to ignore their cities’ round-the-year programming. We’ve shown films at our Cinematheque that would have drawn more strongly if they had been presented under the umbrella of a festival. A festival is a big, ballyhooed event, and people set aside time to plunge into it. They take it as an occasion to explore cinema. But that impulse isn’t as strong, I think, in other seasons.

Accordingly, the HKIFF has developed a smart strategy. It often launches a retrospective during the festival period but then continues it after the festival is finished. This enables the festival to spotlight the series more vividly and to engage viewers to return in the weeks to come. The drawback is that the strategy tantalizes us visitors, who wish we could stay on to get a full dose of Shimizu Hiroshi (subject of a 2004 roundup) or Kinoshita Keisuke (2005) or Nakagawa Nobuo (2006). This year’s hors d’oeuvres were even more scanty: only two of the films of Shibuya Minoru played during the festival, which ended Tuesday. The rest come later in April.

At the venerable Shochiku studio, after assisting Naruse Mikio and Gosho Heinosuke, Shibuya worked with Ozu on What Did the Lady Forget? (1937) before launching his own directing career. He made over forty films, the last one released in 1966. My own awareness of Shibuya before my visit was limited to the family dramas A New Family (Atarashiki Kazoku, 1939) and Cherry Country (Sakura no kuni, 1941), both in a mildly, though not rigorously, Ozuian vein.

At the venerable Shochiku studio, after assisting Naruse Mikio and Gosho Heinosuke, Shibuya worked with Ozu on What Did the Lady Forget? (1937) before launching his own directing career. He made over forty films, the last one released in 1966. My own awareness of Shibuya before my visit was limited to the family dramas A New Family (Atarashiki Kazoku, 1939) and Cherry Country (Sakura no kuni, 1941), both in a mildly, though not rigorously, Ozuian vein.

The earlier film in the partial Shibuya retrospective was Righteousness (1957), an ensemble piece about a neighborhood still laboring under postwar hardships. The young Seitaro is in love with Michiko, but her mother offers her in marriage to her more prosperous roomer. Seitaro works as a mechanic for a bus company, where Fujita is a driver. Fujita has just married a young woman against his father’s wishes. The characters are introduced through the peripatetic Okyo, Seitaro’s mother, who peddles black-market goods to her neighbors. Fujita’s troubles mount up when his bus hits a child, and Seitaro must decide whether to reveal what he knows about the accident. The film builds well to two climaxes, the consequences suffered by Seitaro after he makes his painful decision and then Okyo’s denunciation of her neighbors. On the other side of the ledger, Fujita’s domestic troubles are resolved rather abruptly and implausibly. Still, Righteousness exemplifies the classic Shochiku formula of smiles mixed with tears, capped by a more-or-less upbeat resolution.

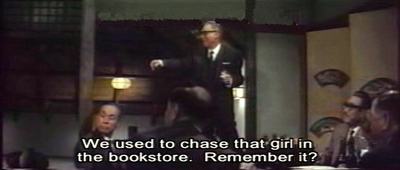

Shibuya was shadowed by Ozu even after the master’s death, for he was assigned to make a memorial film based on the last project planned by Ozu and screenwriter Noda Kogo. This was the film now circulating as Mr. Radish and Mr. Carrot (1965).

Chris Fujiwara has provided us an enlightening account of how Shibuya turned what would probably have been another subtle Ozu meditation on generational strife, in the manner of An Autumn Afternoon, into a more raucous comic melodrama. Yamaki is an executive who lives by strict routine, but he’s also pestered by his four daughters and his lothario brother. When a friend comes down with cancer and the brother reveals himself as an embezzler, Yamaki flees without warning. As his family fret about him, and quarrel among themselves, he settles in among working people, notably some prostitutes and a swindler selling Chinese medicine.

No one in the family displays much virtue, and even Yamaki is seen as cranky and oblivious to the needs of his wife and children. Radish and Carrot’s cynicism seemed to me too easy, and the physical comedy, such as Ryu Chishu’s bodily contortions, struck me as forced and overplayed. Stylistically, the film is eclectic and almost casual. It begins with a zoom and a whip pan. Thereafter, we get flash cuts, canted setups, and a fashion show. Unlike Righteousness, this film justifies Fujiwara’s claim, in a HKIFF catalogue essay not available online, that Shibuya sometimes embraced “visual excess.”

Ozu refused widescreen filming; he compared the ‘Scope frame to a roll of toilet paper. He may have realized that it would pose problems for his graphically matched cuts, deep and subtly imbalanced compositions, and other techniques he had refined over decades. Similarly, Radish and Carrot made me wonder if Shibuya was comfortable working in ‘Scope. He drops in some Ozuian corridor images, but at other times he mounts the sort of packed wide-angle shots common in 1960s Japanese anamorphic films.

When Ozu fills up his 4×3 frames, he gives us more to look at, along with more daring placement of figures. This is not your typical establishing shot.

Ozu’s signature shot is at a low height but seldom at a low angle. Shibuya’s compositions remind you what a real low-angle image looks like, with the camera tipped up considerably.

I know, it’s unfair to judge Shibuya’s film by the exalted standards of Late Autumn (1960), and we risk saddling him with purposes he didn’t have. He probably didn’t set out to make an Ozu pastiche. Yet we can, I think, fault Radish and Carrot sheerly on craft grounds. Two party scenes, one gathering men and one among wives, seemed to me almost haphazard in their spatial development. This cut, for instance, is more careless than anything I noticed in Righteousness.

In the second shot, on the far right side, a waitress is now in the frame next to the old man, and he has already turned and is talking to her instead of his classmates at the other table. When this film was made, younger directors, like Suzuki Seijun and Oshima Nagisa, were already handling ‘Scope with much more assurance. I look forward to seeing more Shibuya widescreen entries to learn if they made more polished use of the format.

Elegance and vulgarity

The other retrospective in question was devoted to Kuei Chih-hung (in Cantonese, Gwei Chi-hung), a Shaws director who has been overshadowed by the more famous Chang Cheh and Li Han-hsiang (here and here on this site). Kuei worked in several genres, including the sex movie and the horror film, and he was able to supply cheap items in quantity. But he stands out partly because he moved outside the opulent Shaw studio to shoot on locations. Working with an efficient crew and a lightweight camera, Kuei produced some films, like The Delinquent (1973) and The Teahouse (1974), that look forward to the social realism of the New Wave that followed. Like some New Wavers as well, Kuei highlighted the cruelty of class warfare in Hong Kong both past and present. Ironically, he ceased directing when he felt that the young generation had pushed things further than he could go.

The other retrospective in question was devoted to Kuei Chih-hung (in Cantonese, Gwei Chi-hung), a Shaws director who has been overshadowed by the more famous Chang Cheh and Li Han-hsiang (here and here on this site). Kuei worked in several genres, including the sex movie and the horror film, and he was able to supply cheap items in quantity. But he stands out partly because he moved outside the opulent Shaw studio to shoot on locations. Working with an efficient crew and a lightweight camera, Kuei produced some films, like The Delinquent (1973) and The Teahouse (1974), that look forward to the social realism of the New Wave that followed. Like some New Wavers as well, Kuei highlighted the cruelty of class warfare in Hong Kong both past and present. Ironically, he ceased directing when he felt that the young generation had pushed things further than he could go.

The crime-centered plots of The Delinquent, The Teahouse, and Big Brother Cheng (1975) manage a fair amount of outrage at policing and justice in Hong Kong, as do Kuei’s contributions to a series of omnibus films called The Criminals. His excursions into exploitation fare with Bamboo House of Dolls (1973), Killer Snakes (1974), and the Hex cycle (1980 and after) show, if nothing else, how anxious Shaws was to retain market share in the face of the thrusting popularity of Golden Harvest releases. Obliged to go gross, the man didn’t flinch. The Boxer’s Omen (1983), a supernatural kickboxing yarn, features one rite that demands that celebrants chew food, spit it out, and pass it along to be eaten by others. (No fakery, everything done in one shot.) My tastes run more to something like Killer Constable (1980).

It’s a shooting-gallery plot. Constable Leng and his team are sent to recover gold stolen from the Empress’s palace, and one by one the fighters are eliminated in skirmishes with the thieves. Kuei pointed proudly to the social criticism in the film: “I simply wanted to depict how insignificant commoners are and how, under totalitarian rule, they turn out to be the victims.” Leng, preferring to kill lawbreakers rather than bring them to trial, pursues the bandits with unblinking ferocity. When he finds a miller who helped the gang, he decapitates the man in front of his wife and squalling baby. But Leng’s brutality meets its match in the bandits, who devise comparably sadistic ways to decimate his posse.

Killer Constable comes near the tail end of the Shaws output, just a few years before the company largely abandoned theatrical film production in favor of television. Kuei is thus able to absorb and advance some of the studio’s signature techniques. His film starts out in the splendor of high-key lighting and saturated color typical of Shaws court epics, but soon enough, sword battles play out by torchlight or in semidarkness.

As for ‘Scope, Kuei had the benefit of a strong tradition. In action films, both Japanese and Hong Kong directors cultivated a “precisionist” use of the ratio that made parts of the composition–sometimes widely distant parts–click into place one by one, at a staccato pace. Here are phases of an early fight in Killer Constable.

The rhythm builds, from the cut to the new angle, then the peekaboo flip of the window, then the spotlighting of Leng in the lower right, and finally the thrusting hand of his victim in the extreme left, at which point the shot comes to rest.

‘Scope felicities like this may stem as much from the power of the tradition as from Kuei’s individual talent. In any case, his retrospective, like the Shibuya one, shows that we haven’t fully charted the range of expressive possibilities opened by popular Asian cinema in their early encounters with widescreen.

Chris Fujiwara’s survey essay, “Irony, Disenchantment, and Visual Excess: The Style of Shibuya Minoru,” appears in the HKIFF catalogue, available here. In Chapter 12 of Poetics of Cinema, I illustrate Japanese filmmakers’ relative laxity about the 180-degree matching system with a couple of shots from Shibuya’s A New Family. The passage in question may be one-off borrowing from Ozu.

The Hong Kong Film Archive book devoted to Kuei Chih-hung provides precious information not only on the director but also on the Shaws studio system. For more on widescreen style at Shaws see my online essay, “Another Shaw Production: Anamorphic Adventures in Hong Kong.” I discuss the rhythmic resources of Hong Kong combat in Chapter 8 of Planet Hong Kong.

Other continuing retrospectives at this year’s HKIFF are devoted to Abbas Kiarostami and Vietnamese cinema from 1962-1989. If you’re passing through town, you could do worse than check them out.

Thanks to Li Cheuk-to for correcting some information.

Opening title for Mr. Radish and Mr. Carrot.

The smoking section

Twenty Cigarettes.

DB here:

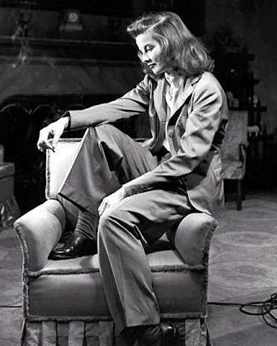

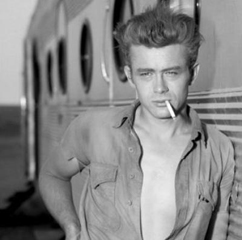

Reflect for a moment on the powerful role played by the cigarette in twentieth-century photographic portraiture. Before our recent worries about lung cancer, why were artists, movie stars, and other celebrities so often artfully posed with a tobacco product? Sometimes the imagery seems to evoke sophistication, presenting the subject as a man or woman of the world.

Or the portrait can suggest a relaxed, informal moment, a cigarette break.

That moment of relaxation can be extended to suggest contemplation or meditation, with the eyes gazing off into the middle distance. Despite the pretty face, this person is deep.

Alternatively, the cigarette can also suggest that painting or writing is a pretty casual affair. Smoking while working, the artist becomes an artisan. Maybe creating masterpieces is no more highfalutin than laying pipe.

And of course there’s the erotic side. A cigarette can make you look attractively dangerous.

In Golden Age studio portraiture, the smoke can become a compositional arabesque.

I’m not suggesting that James Benning set out to subvert this glamourous, stylized tradition in Twenty Cigarettes, which I caught at the Hong Kong Film Festival. But I think his film presents smoking as never seen before–defamiliarizing it, the Russian Formalist literary critics might say. And the movie’s not solely concerned with smoking. It resonates a bit with something I looked into in an earlier entry, on facial expressions in The Social Network. But here the film asks a different question: How expressionless can a face be?

Studied neutrality

A person in a medium shot smokes a cigarette. Repeat nineteen more times, showing smokers who suggest different ethnic and social identities. They are framed against outer walls, gardens, skies, or rooms. As in the Structural Film tradition, we witness an activity whose end is more or less known, and this forces us to study the minutiae of the process. But how much time the shot takes isn’t completely determined. Some smokers smoke faster than others, some shots run longer, and occasionally Benning halts the shot before the cigarette is quite finished.

In each shot, the smoker doesn’t talk and seldom looks at the camera. No one else is visible or audible (except, in one take, a voice distantly shouting, “Fuck you!”) Benning put himself out of sight during the filming of each take. By cutting the smokers off from all social intercourse, the film reminds us that it’s probably more usual for to people smoke while doing something else, like reading or watching TV or talking with friends. Benning forces us to watch the act of smoking in an almost artificially pure state. The film quickly becomes a study in smoking styles—quick non-inhalant puffs, luxuriant drags, little exhalations, slow streams curling out of nostrils. The ciggie is held tipped up in a dainty salute, or jammed between fingers. Solitary smoking becomes a sort of social-science experiment: If you can’t walk around, talk to others, window-shop, or whatever after you’ve lit up, how will you behave?

You’ll behave, Benning’s film suggests, by putting on the most blank expression possible. The portraits of artists and movie stars above use the cigarette to enhance the subject’s attitude–frankness, cool regard, disdain, pensiveness, intellectual seriousness. The cigarette, even the smoke, signifies. Nothing in the cigarette-portrait tradition prepares us for the almost frightening neutrality we see on the faces of Benning’s people. What are they thinking? Are they feeling anything?

It’s rather hard to maintain a poker face in a social interaction. Engaging with others, we spontaneously send signals of interest or mutual understanding, if only through raised eyebrows or a quick smile. But Benning’s lone smokers are eerily blank. Even what might seem to be an expression is often simply the person’s face at rest. (Some resting faces are read as non-neutral, as when an elderly person seems perpetually frowning or hangdog.) In the film, when the person’s expression changes, that’s usually because of the smoking; the twenty people squint or frown or tighten their jaw as they suck or exhale. For once facial movement is divorced from emotional signaling, and the result is a kind of anti-Shirin, Kiarostami’s portrait gallery of people caught up (apparently) in spontaneous bursts of emotion.

Benning’s film brings to mind the Warhol Screen Tests, and he has acknowledged the influence. Yet unlike Warhol, Benning gave his people the same specific task to execute. He’s like Hou Hsiao-hsien, who has explained that he got performances from his nonactors by letting them occupy themselves with eating and smoking. Warhol, as I recall, left things up to his performers, and so they might fiddle with props, run through a range of expressions, or simply stare innocently or challengingly at the camera. (To avoid reproduction rights problems, let me just send you here to sample some possibilities. On this page Nico the superstar seems herself to recreate the mystique of the classic studio portrait.)

Twenty Cigarettes yields something different from the Screen Tests I’ve seen. Using the cigarette as a constant feature, pulling smoking out of its usual place in our habits and social exchange, denying the tradition that shows smoking as connoting attitudes and emotions in people onscreen, Benning enables us to watch, across some ninety minutes, faces that aren’t dramatizing themselves or sending signals. No stars, these folks, let alone superstars. No narcissism either.

Yes, through dress and hair and demeanor we quickly characterize these men and women by type (housewife, hipster, working man). And each face carries marks of experience we can’t help but wonder about. At times I found myself looking for wrinkles and the other signs of smoking’s skin damage. And yes, the subjects know the camera is there, so to some extent they are posing themselves. Even granting all this, it seems to me that Twenty Cigarettes gives us a disconcertingly pure example of what happens when people make a tremendous effort to show as little of themselves as possible. We get to study what lived-in faces look like when they aren’t participating in social life but are aware that the camera is watching them.

Cigarette pictures, as if you didn’t know: Susan Sontag, Cary Grant, Louis Feuillade, Gary Cooper, Katharine Hepburn, Robert Rauschenberg, Jean-Luc Godard, Bette Davis, James Dean, Gary Cooper again, and Marlene Dietrich.

The website Celebrities with cigarettes includes many studio portraits. For examples from the Warhol Screen Tests, go here. On this page Nico the superstar seems herself to recreate the mystique of the classic studio portrait. Background on the making of Benning’s film can be found in this interview at Cinema Scope. On MUBI Neil Young provides a stimulating and painstaking analysis of Twenty Cigarettes.

Thanks to J. J. Murphy for discussions about Warhol, the subject of his forthcoming book, and of course to James Benning for his assistance.

Twenty Cigarettes.