Beyond praise 3: Yet more DVD supplements that really tell you something

Wednesday | May 19, 2010 open printable version

open printable version

Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959)

Kristin here–

Every now and then I discuss a few DVD supplements that teachers might find useful for their classes, though they might be of interest to others as well. Previous installments can be read here and here.

Darby O’Gill and the Little People (Walt Disney Video)

Yes, you read that right. I can’t claim credit for having discovered this disc’s excellent supplement, “Little People, Big Effects.” Shortly after the second “Beyond praise” entry, Dan Reynolds, who teaches at the University of California Santa Barbara, wrote to recommend it.

Darby O’Gill was one of the few Disney live-action films I missed when I was growing up in the 1950s. I acquired the disc and started by watching the feature. I must say that this is one weird movie.

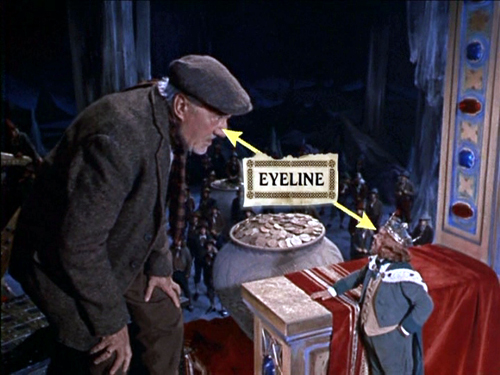

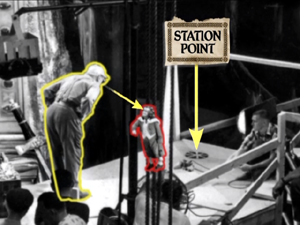

The “little people” of the title are leprechauns, and the special effects used to make them look small are mostly achieved through forced- perspective techniques. In less than eleven minutes, this supplement demonstrates the use of glass paintings, mattes, false perspective, and even a revived Schüfftan process, most famously used for Metropolis, where scale is manipulated by shooting into an angled, partially transparent mirror. Careful calculations allow for over-sized sets in the background to be lined up precisely with normal-scale ones in the foreground, so that the foreground person looks much larger then the background one. Since the two characters, here Darby and King Brian, are supposed to be conversing face-to-face, a manipulation of eyelines, a term we use a lot in Film Art, is necessary. (Despite what my spell-check keeps trying to tell me, “eyeline” is one word in the movie business, as demonstrated above.) In explaining how the actors knew where to look in the shot illustrated at the top, the film shows that “station points” were placed on the floor so that the characters’ eyelines would seem to match up (below). These days actors alone against blue or green screens often have to look at tennis balls to make the direction of their gaze match correctly.)

Clearly some behind-the-scenes footage was made during the production of Darby O’Gill, and this is incorporated into a documentary that includes interviews with master effects expert Peter Ellenshaw, who died in 2007. Ellenshaw worked as a matte painter on half the British classics of the 1930s and 1940s, including Black Narcissus (which has perhaps the greatest matte paintings ever). He then moved to Hollywood in 1950 and began a string of films with Disney that won him an Oscar for Mary Poppins. It’s good to have even these short clips of him demonstrating and discussing his work.

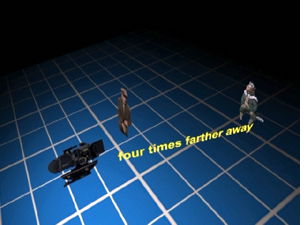

“Little People, Big Effects” should give students (and just about anyone else) a better grasp of perspective and its importance in the representation of depth on a flat screen. I would definitely show it as part of a study of cinematography. If a fifty-year-old film seems a bit out of date, point out to students that, as the narrator mentions, exactly the same techniques were used in many scenes of The Lord of the Rings to make the hobbits and dwarves look small. Similar demonstrations are provided in the supplements to the extended DVD version of The Fellowship of the Ring (Disc 1, “Visual Effects: Scale”).

Elijah Wood sits further from the camera than Ian McKellen in order to make him appear as small as a hobbit

Zodiac (“2-Disc Director’s Cut,” Paramount)

At the end of my first “Beyond praise” entry, I complained about the lack of supplements on the initial DVD release of Zodiac. Then, after the two-disc set with the supplements appeared in early 2008, I forgot to include it in the second entry. Better late than never, so I’m tackling it here. (The supplements are apparently the same for the Blu-ray set.)

As the “DVD Talk” review says. “The self-congratulatory praise is kept to a minimum.”

The main supplement is a 53-minute film called “Deciphering Zodiac.” It’s a good, objective, chronological summary of the film’s production. A lot of talking heads are included, such as the producer, scriptwriter, set decorator. That’s usually a good sign, since it shows that care was taken with the making-of and that enough of the crew members are participating that the account will probably be rounded. There’s a 15-minute making-of specifically on “The Visual Effects of Zodiac.”

Zodiac was primarily shot on professional-level digital cameras, apart from the slow-motion shots, which still need to be done on 35mm due to limitations of the digital technology. Hence there’s a lot of information here on digital techniques. Most of these techniques are used in ways that aren’t necessarily obvious to the viewer. If you want to show students some material on digital effects, this might be a good choice, since it avoids the flashy, obvious effects that so many fantasy and sci-fi DVD supplements concentrate on.

“Deciphering Zodiac” has shots showing the digital camera attached to an elaborate rig around a car, which was used to follow moving cars, including the famous opening tracking shot along a suburban street. The video-assist monitor is often visible in the shots.

One change that digital filming has made in production has been the frequent use of “digital dailies” rather than dailies on film. (Dailies are the unedited takes just as they come from the camera(s); directors and other key creative people typically watch them at the end of each day.) Several scenes of the “Deciphering” documentary show raw shots and are labeled as digital dailies, something which doesn’t seem to be a common feature of supplements. It’s pretty obvious that the shot of Jake Gyllenhaal below would need to be manipulated in post-production. There’s also informative coverage of the methods used to match location and studio-shot footage, particularly for the scene where the killer shoots a taxi driver.

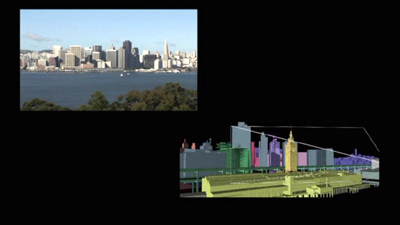

The visual effects documentary has good explanations of the early shot of a rapid move across the bay toward San Francisco as it looked in the period when the film’s action begins, a shot that was done entirely digitally.

Now that so many best-lists for the decade have included Zodiac, it seems to be an official modern classic. Perhaps a somewhat more dignified way of teaching special effects than using a Transformers movie.

The Dark Knight (Two-Disc Special Edition, Warner Home Video)

The supplements for The Dark Knight make a nice contrast with those for Zodiac. Here the makers of a spectacular action movie avoided digital special effects to a surprising extent. Instead they used practical effects, that is, effects accomplished via physical means while shooting rather than those done in post-production via laboratory or digital manipulation. Digital technology was used, of course, but often for rather modest tasks in planning and in erasure of unwanted elements. It’s also interesting as the first 35mm fiction feature to be shot partially on Imax cameras.

The main supplement is “Gotham Uncovered.” It begins by showing how the Imax camera was initially tested on a single action scene shot on location in Chicago. The results led to additional Imax scenes being added to the film. The advantages of Imax—primarily a huge gain in visual quality due to the larger size of the individual frames—are shown to be balanced against the camera’s limitations. The camera is much larger, making handheld shots difficult. It holds only three minutes of film and has a shallower depth of field. While interesting, this first section is surprisingly lacking in actual footage of the filming, often depending on still photos. We tend to assume that in this day and age, the making-of is taken into account from early on in a production. It’s surprising how often that turns out not to be the case.

A five-minute segment, “The Sound of Anarchy,” shows Hans Zimmer sitting at a computer and talking about the modernist, dissonant music for the Joker character. It’s mildly informative.

“The Chase” is perhaps the most useful section of the making-of. The decision was made to shoot the scene on Lower Wacker in Chicago. Here digital effects were kept to a minimum, with multiple cameras mounted on vehicles like the motorcycle below. These were special smaller Imax cameras. Only four such cameras existed at the time, though an accident reduced that to three!

One big moment in the chase has the Batmobile crashing into a garbage truck. Again, rather than resorting to digital effects, the crew built miniatures of the two vehicles and the set. The decision was also made to shoot a crash of an 18-wheeler on LaSalle Street using a real truck on location, and the scenes showing the practice sessions for this reveal the kind of planning that goes into the big action scenes that are so common in films these days.

A multi-vehicle crash scene was done with several cameras, which is common practice for unrepeatable actions. (Even on a big-budget film like this, no one would want to crash more than one Lamborghini.) The cameras often show up in each other’s shots, and the supplement shows the resulting footage and how CGI is later used to erase them—again, a very common use of digital tools. Here a camera on a crane is visible at the center left in the original footage of the crash:

In one scene, the Joker walks out of a hospital, which explodes behind him. A prime candidate for digital effects, one would think. Instead, the filmmakers opted to have a demolition company destroy a real building. CGI was used to plan the scene:

A shorter supplement, “The Evolution of the Knight,” deals mostly with the design process for Batman’s suit and the Batpod. Again the emphasis is on bringing reality into the filming. It’s pointed out that while much of Batman Returns was shot on sound stages, the team decided to try and shoot the sequel in the city streets as much as possible.

Beware of these

I have to admit, one reason that this series appears so rarely is that for every DVD with useful supplements that I find, there are two or three uninformative ones that I have to sit through–or at least sample. In addition to recommendations, let me warn you away from some of the ones I switched off.

I had expected the Slumdog Millionaire DVD extras to be interesting, given the mixture of digital and 35mm shooting, the location work, and so on. But obviously the filmmakers had no idea that the film would be a success, so they seem to have done little behind-the-scenes shooting as they made it. The result is a not terribly informative, bare-bones 18-minute making-of.

Supplements as praise-fests have not gone away. Musicals seem especially to bring them out. “Get Aboard! The Band Wagon” provides 36 minutes of mutual admiration. In “From Stage to Screen: The History of Chicago,” Chita Rivera unintentionally achieves a parody of the gushing movie star who lauds everyone she worked with.

David and I just watched Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. I had liked it when I saw it in first run, and predictably, David enjoyed it, too. It’s a clever, well-scripted, well-animated film. We hoped to learn something from its supplements, but the making-of seems to be aimed at children, and young ones at that. The co-directors and some of the other filmmakers look distinctly embarrassed to be participating, partly because a lame comparison of making a film to mashing food together forms a running motif. A pity, since the movie deserves better. As reviewers keep pointing out, the best animated films these days are made for adults as much as for children.