Archive for the 'Narrative: Suspense' Category

Clocked doing 50 in the Dead Zone

DB here:

August’s final weekend fizzled. Ray Subers of Box Office Mojo writes:

The Expendables 2 repeated in first place on what was easily the lowest-grossing weekend of 2012 so far: the Top 12 added up to $83.8 million, or 12 percent less than the previous low (Feb. 3-5).

This late-summer slot is usually a problem. Here’s Subers on last year’s situation, which included Hurricane Irene.

The weekend as a whole . . . is poised to be one of the slowest of the year, hurricane or no. . . . This crop of new releases [Columbiana, Don’t Be Afraid of the Dark, Our Idiot Brother] is modest at best, though Irene has given Hollywood a convenient excuse.

With few exceptions, both winter and summer have stretches which make it hard for new releases to make headway. January through March and mid-August through September are forbidding Dead Zones. Is it a vicious cycle? Do audiences stay away at these times because most releases have little appeal? Or do the distributors treat these months as dumping grounds because people tend to stay away?

Some years back, I pointed out that often these barren months yield some good, unpretentious fruit. This is the realm ruled by our B films–the action pictures, romcoms, modest dramas, and low-budget fantasy and science fiction that give the theatres minimal reasons to stay open. Often the Dead Zone can yield modest, interesting movies that escape the hyperbole that surrounds bigger productions. My example in 2008 was Cloverfield, which actually made decent money in wintry down times. Last year, there were Lone Scherfig’s One Day, Steven Soderbergh’s Contagion, Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, and probably others I missed.

I saw only one new release in the 24-26 August window, Premium Rush. It seems to me one of the best mainstream movies I’ve seen this year, and its weak performance ($6 million on the weekend) just shows that you can’t judge by box-office numbers. I found it much more enjoyable as a movie, and more intelligent in its grasp of storytelling and audience uptake, than Marvel’s The Avengers (opening weekend $207 million) and The Dark Knight Rises ($424 million), the two hulks looming over the season.

If Truffaut is right that cinema gives us beautiful people who always find a parking space, Premium Rush is pure cinema. The gallery of characters presents hip youngsters of Benetton gorgeousness (white guy/ African American guy/ Hispanic woman/ Chinese woman/ Indian guy) up against a middle-aged white guy with an ominously overhanging lip that makes him look both stupid and perpetually peeved. Needless to say, Michael Shannon has fun with this. And the couriers always find a place to lock their bikes.

It’s also a real Manhattan movie, which is to say it invokes welcome prototypes: frantic bustle, fast talk, quarrelsome strangers, good cops, bent cops, dumb cops, collisions born of congestion, chance encounters that become significant, violence courtesy of a mafia (Chinese), and moments of casual kindness. We’re all Saroyans when it comes to the Big Apple. We endlessly sentimentalize this city in our movies, and they’re probably the better for it.

But to make a more analytical case that this is a smart, well-put-together movie, I must indulge in spoilers, which are coming right up.

Bike boy

Premium Rush is short: 83 minutes and 49 seconds, not counting credits. That’s also about the length of G-Men, The Ghost Goes West, Holiday, Shopworn Angel, Phantom Lady, The Dark Mirror, Pitfall, The Suspect, Baby Face Nelson, and the 1953 War of the Worlds. I’m not proposing length as a yardstick of value, only noting that our two-hour-plus blockbusters have forgotten what you can do in short compass.

In many B-pictures, both now and then, brevity can encourage you squeeze diverse possibilities out of a simple situation. In Premium Rush, the central situation exemplifies the screenwriter’s old adage: Swamp your protagonist with problems. Here they come fast.

At 5:17 pm, Manhattan bike messenger Wilee is assigned to pick up an envelope from Nima, a Chinese woman who works at Columbia University. He’s immediately pursued by a cop, Robert Monday, who wants what’s in the envelope. At the same time, Wilee and his girlfriend Vanessa, also a messenger, are quarreling because he missed her graduation ceremony. A heavy make is flung Vanessa’s way by Manny, an African American Adonis who’s Wilee’s only rival in virtuoso biking. And at intervals Wilee, who shoots through traffic with suicidal glee, is in the sights of a bulky bike cop. All jammed together we have a free-spirited protagonist who’s quit law school because he loves to ride, a love triangle, a sinister cop, and a mystery: What’s in the envelope? By 7:00 pm all is resolved.

The film displays the classic Hollywood double storyline–romance problems and work problems, intertwined. Still, the plot isn’t as linear as I’ve just implied. I think that the film exemplifies clever ways of working with the four-part structure that Kristin has identified as common in Hollywood features. (That’s discussed here and here and here.) My timings aren’t as exact as I’d like, but I think they’re decent approximations.

Setup (0-ca. 28:00)

After the flash-forward prologue, set at 6:33 pm, and the brief exposition of Wilee’s world view, we see him picking up the envelope at 5:17. It’s addressed to Sister Chen in Chinatown and it must arrive by 7:00.

In a chase Wilee evades Monday and the bike cop, and goes to a police station to file charges against Monday. But he has to take cover when Monday comes in. Now the film’s narration gives us a block of scenes that flashes back to earlier in the day, starting at 3:47. We see Monday lose thousands of dollars in Chinese gambling parlors. Punished by the loan shark’s thugs, he kills one of them. To make amends, he agrees to intercept a ticket that’s worth $50,000 that’s making its way to Chinatown. At the end of the flashback, Wilee, hiding in the police station’s men’s room, opens the envelope and sees that what’s inside is simply a movie stub with a Smiley scrawled on it.

In a chase Wilee evades Monday and the bike cop, and goes to a police station to file charges against Monday. But he has to take cover when Monday comes in. Now the film’s narration gives us a block of scenes that flashes back to earlier in the day, starting at 3:47. We see Monday lose thousands of dollars in Chinese gambling parlors. Punished by the loan shark’s thugs, he kills one of them. To make amends, he agrees to intercept a ticket that’s worth $50,000 that’s making its way to Chinatown. At the end of the flashback, Wilee, hiding in the police station’s men’s room, opens the envelope and sees that what’s inside is simply a movie stub with a Smiley scrawled on it.

Complicating action (ca. 28:00-48:00)

A plot’s second stretch is often a complicating action, something that changes the protagonist’s goals. Originally Wilee wanted to fulfill the delivery; now, with things getting dangerous, he decides not to. He goes back to Columbia to return the envelope to Nima.

At this point we get a flashback explaining that the ticket is a token from a Chinese crime lord, whom Nima has paid with her savings. In the meantime, Monday finds a new stratagem. Instead of trying to catch Wilee, he calls the messenger service and, citing the number on the receipt he has wrested from Nima, he changes the dropoff point. Raj, the dispatcher, gives the order to Manny, Wilee’s rival, and Manny fetches the envelope moments after Wilee has returned it.

We’re at about the midpoint of the film when Nima explains that the money is payment for her son’s illicit passage to America. Now Wilee is faced with a classic choice for an American protagonist: To mind your own business, or to risk your life and livelihood to help someone in distress. He chooses to be a hero, and that means catching up with Manny.

Development (48:00-64:00)

The development section usually doesn’t radically change the premises of the plot. Instead, it’s used to define character further, flesh out secondary aspects of the situation, rework motifs, build suspense, and, surprisingly, simply delay the conclusion. Premium Rush offers a good example of several of these functions. Pedaling frantically after Manny, Wilee phones him and offers him money to give him the envelope. Manny could have accepted, and that would initiate the climax right away.

But Manny is a competitor. We’ve seen that he has his eye on Vanessa and he’s convinced he could beat Wilee in a race. So Manny’s personality, agreeable but aggressive, motivates delay, in the form of a prolonged chase/race that, inevitably, brings in the bike cop yet again. Meanwhile, the fact that Vanessa happens to be Nima’s roommate, and that she first put Monday on Nima’s trail, puts her into the mix, pedaling fast to converge with the three men. When she and Wilee finally meet, he hides the ticket in his bike’s handlebar, creating preconditions for the climax.

But Manny is a competitor. We’ve seen that he has his eye on Vanessa and he’s convinced he could beat Wilee in a race. So Manny’s personality, agreeable but aggressive, motivates delay, in the form of a prolonged chase/race that, inevitably, brings in the bike cop yet again. Meanwhile, the fact that Vanessa happens to be Nima’s roommate, and that she first put Monday on Nima’s trail, puts her into the mix, pedaling fast to converge with the three men. When she and Wilee finally meet, he hides the ticket in his bike’s handlebar, creating preconditions for the climax.

This section builds to a pile-up that ends with what we saw at the film’s beginning: Wilee sailing across the frame and landing on the pavement. Dazed, he remembers meeting Vanessa at a bar, where he won a prize as top messenger–the prize being the bike he’s been riding. Each of the three sections we’ve seen includes a flashback, but this is the first one presented as a character’s memory.

Climax (64:00-83:49)

One sign of a climax is this: We know everything we need to know. We know what the ticket means, what all the characters want, and what the stakes are. Now we just have to watch their plans work. In the ambulance, Wilee is suffering from cracked ribs, and Monday bends over him, whacking the ribs to make him talk. Wilee admits that he’ll tell everything if he can get his bike back. This is the make-or-break moment: The hero has to find a subterfuge that will accomplish his goal. Recovering the bike will allow him to retrieve the ticket.

The film has relied on crosscutting throughout, but now the technique expands and accelerates. Nima heads for Chinatown. Wilee’s bike is taken to the police impound facility, but Vanessa has followed it there and gets inside. Soon Wilee arrives with Monday, who searches Manny. Inside, Wilee and Vanessa recover the ticket and escape, courtesy of some very flashy bike-riding. They split up: Wilee to deliver the ticket, and Vanessa to assemble a flashmob.

From the start, during Wiley’s voice-over exposition, we’ve been aware that the couriers form a sort of countercultural community, and a very early scene showed bikers stopping to help fallen comrades. (Good old foreshadowing.) Now, as Wilee goes to deliver the ticket, he faces Monday, who has again caught up with him. The messenger community appears and Monday realizes he can’t fight them all. He’s killed by a Chinese gang member, introduced in part 2 and seen en route to the Chinatown showdown.

Wilee delivers the ticket to Sister Chen, and she phones the snakehead in China to report that the boy’s passage has been paid. Nima thanks Wilee, and in a canonical wrapup Vanessa and Wilee embrace. A brief epilogue echoes the beginning by showing Wilee back whizzing through the streets. “Can’t stop. Don’t want to.”

In Storytelling in the New Hollywood, Kristin points out that a film of 80-90 minutes might have only three parts, each 20-30 minutes long. I prefer my layout because it lets each of the first three sections have its own flashback, and it highlights the midpoint–the crucial moment of choice for Wilee. But proponents of a three-act structure would claim that their model accounts for the movie too. The setup would then run to the point at which Wilee escapes from the police station and calls Raj to tell him he wants no part of the deal; the complicating action would consist of Manny’s pickup and the ensuing chase; and the climax, as with my breakdown, would start when Wilee confronts Monday in the ambulance. In this respect, I think Premium Rush would be an enjoyable film to use in teaching some different approaches to Hollywood dramaturgy.

Personal velocity

From another angle, the first three parts (or two, if you insist) are themselves flashbacks from the opening shots. We’re introduced to Wilee as he sails against the sky in slow-motion, hurled from his bike and en route to hitting the pavement. Then in a kind of prologue the narration takes us back to him enthusiastically pedaling through the streets at 5:10 that day. His voice-over confides his love of biking, his refusal to use gears or brakes, and his preternatural ability to avoid collisions. In Wait Frank Partnoy shows how well-practiced athletes slow down their perception of time, giving themselves 200 milliseconds or more to decide how to return a tennis serve or a cricket shot. Thanks to CGI that plays out Wilee’s options within a split second, we see that he has that gift.

You can criticize voice-over exposition like Wilee’s as lazy screenwriting, and sometimes it is. But given the time pressure, both in the story’s deadlines and by the movie’s length, it creates a concise lead-in that sets the rapid pace of the little adventure we’re going on. The same pace informs the layout of the situations.

During the prologue, Vanessa gets concisely characterized. Nearly sideswiped by a cab, she punishes the driver by using her bike chain to amputate his outside mirror. Six minutes into the movie, Wilee gets his assignment; three minutes later he’s picking up the package. A minute or two after that, he’s accosted by the cop Monday. Then we’re off on a swift chase scene, shot and cut with a precision and economy largely missing from the two movie hulks mentioned above. The many stunts–most of them practical ones, not CGI-created; and many quite funny–keep you riveted to the screen. Likewise, the cascade of deadlines gives every scene a time pressure that’s only enhanced by hairbreadth escapes and near-misses in traffic.

Rapid pacing lets you slip smart things in casually, like the fact that Monday goes by the alias of Forrest J. Ackerman. The use of vaguely Googleized 3D maps, with Wilee’s route traced in yellow and his hypothetical zigzags in white, keeps us oriented briskly. Wilee’s swift, insolent repartee yields comic motifs, which I won’t spoil by specifying. Even the product placement has a jokey quality: these purportedly cool kids are stuck in a Columbia movie, so they all must use Sony Ericsson cellphones (1.8 % global market share last year).

The film employs the redundancy necessary to the Hollywood tradition, but in quickfire fashion. So, for instance, we learn in little bursts that Wilee rides without gears or brakes: he tells us, then later we see his handlebars and axles in close-up, still later Manny mocks his Old School simplicity, and then we see close-ups of Manny’s high-end gear. Finding fresh ways to repeat information is a measure of craft skill. You don’t just restate it; you do it once in words, then images, then contrasting images, and so on. But you can do it all so fast it doesn’t seem redundant. The payoff occurs when Vanessa, warned by Wilee that using brakes will kill her, has a serious crash. In one brief shot she angrily whacks off her brakes, bringing herself closer to his hell-for-leather ethic. Blink and you might miss it.

The film’s use of some common current conventions, like impersonal flashbacks that jigsaw together earlier events in different lines of action, adds to the sense of compression. The replays that show how the lines knot together are quick and simple. Above all, I congratulate director David Koepp, who also wrote the film with John Kamps, on avoiding the obvious. Lesser minds would have called our hero Road Runner and made the futile cop the Coyote figure. Wilee the biker combines the Coyote’s cosmic persistence with the Road Runner’s speed and vocalizations. Joseph Gordon-Leavitt’s grinning giggle comes pretty close to a meep-meep.

Above all, the film’s momentum comes from a plot motored by deadline-driven chases. No other medium can render the exhilaration of sheer headlong velocity. From the early 1900s up to today, cinema is drawn toward people, animals, and machines hurtling across the screen. Vanishing Point, Speed and Premium Rush are tapping the appeals exposed by great chases like those in Keaton’s Cops and The General and less-known Harold Lloyd masterpieces like Girl Shy and For Heaven’s Sake. I sometimes complain about post-1960s Hollywood, but I’ve got to admit that the revival of flamboyant set-piece chases in Burt Reynolds and Clint Eastwood movies, Raiders of the Lost Ark, and the action-adventure movies that followed have paid big dividends. Screen action doesn’t have to be rapid, but when it is, and when it involves a race against time, it can be transporting. Sometimes you just want a movie to move.

True, the summer comic-book sagas shift their bulk, but leadenly. When these zeppelins accelerate, they often burst into disjointed imagery. Premium Rush could be a textbook in how to give fast action a clean, cogent profile. When we see energetic movement that’s coherent, unpretentious, and inventive, gracefulness comes along as a bonus. You get another blossom in the Dead Zone.

Assuming that the summer ended on 26 August, Indiewire offers its analysis of summer trends. The most striking news: Overseas box office is about 2/3rds of the total.

Business over Labor Day weekend, which might also be counted as the end of summer, was somewhat stronger, with one robust win (The Possession, at $21 million). Box Office Mojo‘s report from 2 September doesn’t even mention Premium Rush, which is projected to finish Monday with a total to date of about $13.5 million. See also Leonard Klady’s summer wrapup at Movie City News.

Kristin discusses the structural patterns of mainstream American movies in the first chapter of Storytelling in the New Hollywood and offers many examples in later chapters. I test it on more recent cases in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

P.S. 4 September 2012: Thanks to a tweet from K. J. Hargan, I learn of a suit from a writer claiming that the movie is based on a novel he wrote in 1998. [2013 update: The plaintiff lost the case in April.]

P.P.S. 5 September 2012: David Koepp has written me with more information about his goals in making the film.

Nothing about Premium Rush was easy. The extreme nature of the work on the city streets, the physical risks to the actors and stunt performers, and our determination to find our entertainment value in real physical performance rather than CG work (except in certain obvious situations where it was played for laughs) all raised the degree of difficulty in their own way.

But one of the most gratifying things about your analysis was your appreciation of our structure, and how hard we worked to make a film of breathless brevity, in the great tradition of B pictures for decades. I realize that, as far as aesthetic criteria go, “short” doesn’t sound like a terribly high-minded one, but to me it was an essential guiding principle and a hard one to pull off. Your understanding of the value of a brisk pace and a tight running time made me smile, and your respect for the amount of love and effort some of us put into genre work is much appreciated.

Many thanks to David for the kind note.

I Love a Mystery: Extra-credit reading

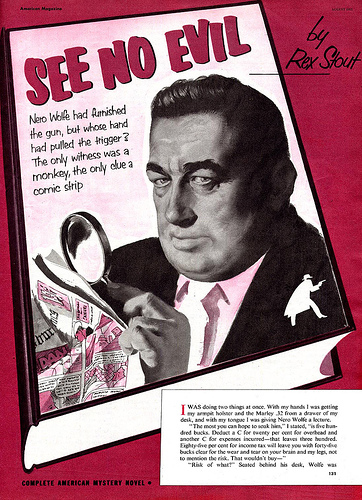

Thornton Utz illustration for Rex Stout novella from American Magazine, 1951. Obtained from the excellent site Today’s Inspiration.

DB here:

Over the next few months, I’ll be traveling with a talk on Hollywood cinema of the 1940s. The ideas I’ll propose are destined for a book about narrative norms during that period. Mystery fiction is important to that lecture, but I don’t have room there to supply much background about the relevant conventions. So I’m sketching in this background here, for people who might hear the talk somewhere or who might just be curious. Consider this as another experiment on the blog, using the web to supplement a lecture.

Although the lecture is mostly about cinema, this entry is mostly about novels and plays. But I’ll mention film here and there, and you’ll notice that some of the books and plays I mention were adapted for the screen.

A mega-genre

The first half of the twentieth century saw an explosive expansion in genres built around mystery and suspense. The most obvious genre is the detective story. In the wake of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes tales, a great many writers developed and elaborated on the idea of the master sleuth, the genius of observation and reason. Central to this tradition was the puzzle that could be solved by careful noting of clues and meticulous reasoning about them, supplemented by a good knowledge of human nature or local customs. The author needs to keep us in the dark about both the crime and the detective’s chain of reasoning; hence point-of-view figures like Watson, who can be appropriately confounded, relay the detective’s cryptic hints, and marvel at the final revelations.

Readers quickly learned the conventions, so writers had to innovate constantly. Sometimes a writer was original on more than one front. For example, R. Austin Freeman created a revamped Holmes surrogate in a scientific criminologist, Dr. Thorndyke, while also creating a new narrative structure: that of the “inverted” tale. The first section of the story follows the criminal who commits the crime; the second part details how Thorndyke, using evidence and inference, solves it.

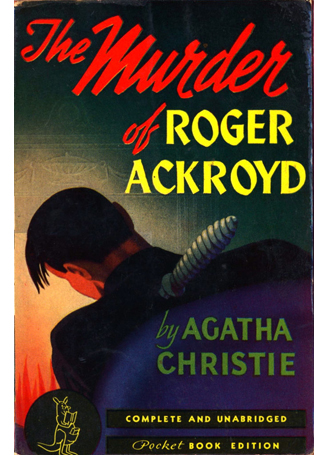

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

Historians of the detective story have a standard account that goes like this. The puzzle-centered plot developed to its apogee in the 1920s and 1930s, chiefly in Britain, and was picked up in the United States. In books like The Murder of Roger Ackroyd (Agatha Christie, 1926), The Canary Murder Case (S. S. Van Dine, 1927), The Unpleasantness at the Bellona Club (Dorothy L. Sayers, 1928), The Poisoned Chocolates Case (Anthony Berkeley, 1929), The Egyptian Cross Mystery (Ellery Queen, 1932), and The Crooked Hinge (John Dickson Carr, 1938), the crimes are deeply puzzling, even fantastical, and the solutions ever more recherché.

It’s hard for us to conceive today how massively popular these puzzle books were. Van Dine’s first novels were bestsellers comparable to Jonathan Kellerman’s books today. Just as important, the detective story was granted quasi-literary status. Magazines and newspapers that wouldn’t dream of reviewing romance or adventure fiction devoted space to detective stories, sometimes even setting up separate columns or sections for reviews. It was believed, rightly or wrongly, that whodunits had a more intellectual readership than Westerns or science fiction.

At about the same time, according to the standard account, a counter-current was swelling. In the pulp magazines of the 1920s, the “hard-boiled” detective emerged as an alternative to the master sleuth. The prototype is Dashiell Hammett’s Continental Op in stories through the late 1920s, to be followed by Sam Spade in The Maltese Falcon (1930). Strikingly, Hammett and other hard-boiled writers don’t wholly abandon the basic idea of solving a mystery through some sort of reasoning. The differences have to do with realism. The crimes, however, aren’t usually fantastical ones like the Locked-Room problem; the killings tend to be mundane. If the white-glove detective’s only real opponent is a master criminal like Professor Moriarty, the hard-boiled detective faces off against organized crime, or at least people who commit murder outside upper-crust parlors and remote country houses. Clues are less likely to be physical, and more psychological, depending on bits of behavior or flashes of temperament. Raymond Chandler and others took the hard-boiled initiative into the 1940s, and the brute detective, who solves crimes with boldness, insolence, and a pair of fists, occasionally supplemented by torture, found bestseller status in Mickey Spillane’s I, the Jury (1947) and subsequent novels.

I’d argue that some writers could blend the master-mind detective and the tough guy. Erle Stanley Gardner’s Perry Mason was one such hybrid, though leaning closer to the hard-boiled model. Rex Stout solved the problem neatly by creating two detectives: the insolent legman Archie Goodwin serves as a hard-boiled Watson to sedentary Nero Wolfe. But on the whole, historians tend to assume that the Holmesian superman and the puzzle-dominated plot were swept aside by the rise of the tough-guy detective solving mysteries that were grittier and more “realistic” than what had preoccupied Golden Age writers.

Two other major developments are typically highlighted by historians. There was the police procedural, perhaps initiated by Lawrence Treat’s V as in Victim (1945), and explored with great ingenuity in the novels of Ed McBain. There was also what Julian Symons has called the “crime novel,” the story of psychological suspense, with Patricia Highsmith’s Strangers on a Train (1950) serving as a good example. Both of these genres have proven popular to this day (CSI as a procedural, the films of De Palma as psychological thrillers).

A tree and its branches

Like most histories hovering fairly far above the ground, the standard account traces some main contours of the landscape but misses some interesting byways. By taking Doyle as the prototype, this account tends to identify mystery fiction with detective plots in the Holmes mold. But mysteries come up in other forms.

The standard account has trouble accommodating the development of the spy genre, which often involves solving a crime, but less through abstract reasoning than by putting the hero through hairbreadth adventures. Think for instance of The 39 Steps, both the 1915 novel and the 1935 film.

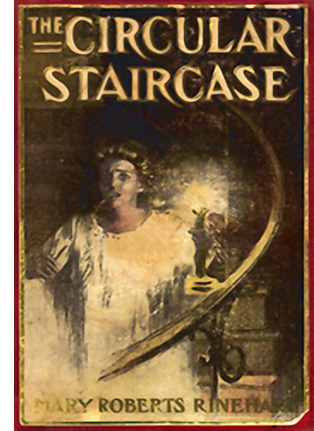

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

More seriously, by identifying solving mysteries with the activities of professional, overwhelmingly male, detectives historians have neglected the powerful and popular tradition of the revived Gothic or “sensation” novel of the mid-nineteenth century. This is typified by Wilkie Collins’ Woman in White (1859-1860) as much as by The Moonstone (1868), often considered the first detective novel (largely because a detective figures as one of the characters, even though he doesn’t solve the mystery). Collins’ novels, along with those of Mary E. Braddock, updated the Gothic format through more complex plotting and multiple points of view. In the next century, Mary Roberts Rinehart, with The Circular Staircase (1908), has to be considered as important as Freeman. Rinehart’s plot introduces the crucial conventions of the mysterious house, the curious and brave woman who explores it, and the threats lurking behind placid domesticity. While the classic white-glove sleuth isn’t usually in much danger, The Circular Staircase and other updated sensation novels make the investigating figure a woman in peril. The sensation novel replaces cool rationality with fear and desperation.

Jane Eyre is an obvious source for Rinehart and her successors, and perhaps the association with women’s writing in general made historians and practitioners of the Golden Age mock the revived Gothic as too feminine, too far removed from the bluff masculine camaraderie of 221 B Baker Street. The Gothicists had their revenge: Daphne Du Maurier’s Rebecca (1938) outsold every other mystery novel of its time and sustained a cycle of new sensation novels by Mabel Seeley (The Chuckling Fingers, 1941), Charlotte Armstrong (The Chocolate Cobweb, 1948), and Hilda Lawrence (The Pavilion, 1946). The genre is maintained today by Mary Higgins Clark, Nicci French, and many other writers.

So mystery and detection formed a broader tradition than literary historians sometimes acknowledge. Another marginal form was the suspense thriller. Again, we can point to a woman: Marie Belloc Lowndes, author of The Lodger (1913). An early instance of the serial-killer plot, it’s also a tour de force of point-of-view; unlike the film versions, it restricts itself quite rigorously to what certain secondary characters know. Choices about narration and viewpoint are no less crucial to the thriller than to the Great Detective tradition.

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

The psychological thriller was revived during the Golden Age, sometimes by practitioners of the puzzle-story. Anthony Berkeley Cox, writing as Anthony Berkeley, noted in The Second Shot (1930):

I personally am convinced that the days of the old crime puzzle pure and simple, relying entirely upon plot, and without any added attractions of character, style, or even humour, are, if not numbered, at any rate in the hands of the auditors. . . The puzzle element will no doubt remain, but it will become a puzzle of character rather than apuzzle of time, place, motive, and opportunity. The question will be not “Who killed the old man in the bathroom?” but “What on earth induced X, of all people, to kill the old man in the bathroom?”

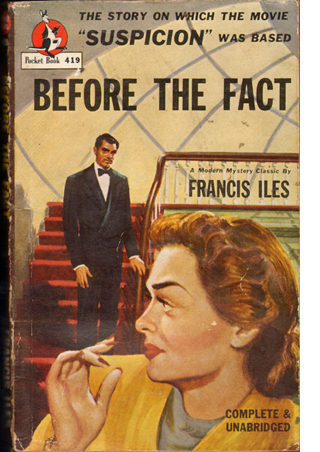

Cox went on to test his premises in Malice Aforethought (1931) and Before the Fact (1932). Both trace the schemes of wife-killers, but the first novel is told from the husband’s standpoint and the second from the wife’s. The latter book opens:

Some women give birth to murderers, some go to bed with them, and some marry them. Lina Aysgarth had lived with her husband for nearly eight years before she realized that she was married to a murderer.

There followed other domestic-crime psychological novels, notably Richard Hull’s The Murder of My Aunt (1934).

Sometimes suspense thrillers have a solid mystery at their center; this is common when the protagonist is a potential victim. Other thriller plots in effect present the first half of a Freeman “inverted” story, concentrating on the criminal’s execution of a crime and the resulting efforts to escape punishment. Both possibilities were on display in British stage plays of the 1920s and 1930s. In a sense Cox was beaten to the punch by Rope (1929), Blackmail (1929), and Payment Deferred (1931). Later examples are Night Must Fall (1935) and the woman-in-peril dramas Kind Lady (1935) and Gaslight (1938). Many of these plays were made into films.

The novel of suspense really came into its own in the 1940s, when it started to incorporate abnormal psychology. Patrick Hamilton, author of Rope and Gaslight, provided an influential novel as well, Hangover Square (1941). Cornell Woolrich and David Goodis, who mined this nightmarish vein, achieved posthumous cult status because, again, of the spell of film noir. Other suspenseful students of mania were Dorothy B. Hughes (In a Lonely Place, 1947), Charlotte Armstrong (The Unsuspected, 1945; Mischief, 1951, filmed as Don’t Bother to Knock), and Elizabeth Sanxay Holding (The Blank Wall, 1947, source of The Reckless Moment). Chandler called Sanxay Holding “the top suspense writer of them all.” We shouldn’t ignore the influence of Simenon’s romans durs, which were being translated and respectfully reviewed throughout the war years.

Yet another new wrinkle on the mystery thriller was the genre of courtroom novels. The Bellamy Trial (1927), which begins when the trial does and restricts itself almost completely to what transpires in the courtroom, popularized the pattern. Stage plays of the 1920s adopted the pattern too. The format proved irresistible for early talkies, as in adaptations of The Bellamy Trial (1929) and Thru Different Eyes (1929) and the radio-inspired Trial of Vivienne Ware (1932). Cox, who seemed to try his hand at every current trend, gave his own twist to the juridical mystery in Trial and Error (1937).

Most of these novels focused on the trial proceedings from the perspective of the defendant, but a few concentrated on those sitting in judgment. The Jury (1935), by Gerald William Bullett, characterizes the jurors singly before they gather and then shows the trial from their standpoints before taking us into the jury room to hear the arguments. Bullett’s novel finds an equally engrossing complement in Raymond Postgate’s Verdict of Twelve (1940). There were also Eden Philpotts’ The Jury (1927) and George Goodchild and C. E. Bechhofer Roberts’ The Jury Disagree (1934). We can immediately recognize the teleplay and film Twelve Angry Men as an updating of this minor line.

Merging and markets

The family tree of mystery, then, grew many branches in the 1920s and 1930s—the pure puzzle, the hard-boiled investigation, the spy story, the revised Gothic or sensation novel, and the suspense thriller, often of a psychological cast. Unsurprisingly, the genres began to mingle. Cox was perhaps the writer most interested in hybrids, but John Dickson Carr tried his hand at the thriller as well (The Burning Court, 1937), as did Agatha Christie in And Then There Were None (aka Ten Little Indians, 1940).

The process sped up during the 1940s, when writers began blending crime-solving with psychological suspense. We can get a sense of how the protagonist-in-peril side of the thriller melded smoothly with the enigma-based investigation by looking at the jacket copy of a fairly ordinary entry, Alarum and Excursion (1944):

Bit by bit, a gesture here, a sound there, Nick Matheny pieced together the awesome puzzle of the accident that had sent him to a sanitarium with traumatic amnesia. One by one he reconstructs, he probes the cirumstances of the explosion in his factory, the disappearance of his weak but beloved son, his wife’s strange attitude toward the new management of the business, and the status of the new synthetic fuel formula, which was so urgently needed.

As the dreadful picture unfolds itself, Nick escapes from the sanitarium to ferret out the sinister changes that have disrupted his business and brought his active life to an abrupt close.

Virginia Perdue, author of He Fell Down Dead, skillfully handles the difficult flash backs in this unusual psychological drama. There are many scenes where the tricks of thought, the tenseness of apprehension, the visions through the deserted streets of blacked-out memory poignantly work their stealth upon the mind of the reader.

Alarum and Excursion wasn’t adapted into a film, but reading this spoiler-filled jacket copy you can easily imagine the movie.

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

One more factor needs to be mentioned: the publication venues. Everybody knows that the hard-boiled tradition has its roots in Black Mask and other pulp magazines of the 1920s. What’s less often emphasized is the “slick-paper” market of the 1930s and 1940s. The Saturday Evening Post, Ladies’ Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, Cosmopolitan (rather different from what it is now), The American Magazine, and many other weekly magazines ran a great deal of fiction, both short stories and serialized novels. The high-paying slick market showcased soft-boiled mysteries involving Perry Mason and Nero Wolfe and welcomed suspense fiction too. Major suspense authors of the 1940s, such as Charlotte Armstrong and Vera Caspary, would garner tens of thousands of dollars in serialization rights. On the right is the cover of Collier’s for 17 October 1942, announcing the first installment of Ring Twice for Laura, later known simply as Laura.

As mystery genres proliferated, their popularity soared. Contrary to what historians imply, the puzzle novel with a brilliant sleuth was far from defunct. Christie’s Poirot and Sayers’ Wimsey retained their fame into the 1940s, significantly outselling Hammett and Chandler. Ellery Queen’s novels are not read much today, so it’s hard to imagine a time when over a million copies of them were in print. More generally, the public’s appetite for mystery novels and radio plays was intense. In 1940, 40 % of all titles published were mysteries, and in 1945, an average four radio shows devoted to mystery were broadcast every day, each drawing about ten million listeners.

Small wonder, then, that Hollywood came calling. Curiously, the master detectives popular with the reading public wound up in B-film series (Charlie Chan, Ellery Queen) or remained unexploited in the 40s (Nero Wolfe, Perry Mason). What came to the fore, as being more suitable for the dynamic medium of film, were the hard-boiled heroes of Hammett and Chandler. Because the rise of hard-boiled adaptations fed clearly into film noir, they have attracted the most attention. But mutating alongside them, and becoming at least as lucrative, were the films shaped by the updated Gothic and the psychological thriller. Variety noticed the trend in fall of 1944.

Plain murder as a film frightener is passé. Been done too long in the same old way. Theatregoers actually can yawn in the face of manslaughter as it’s been perpetrated for the whodunits during the past year or more. . . . The newer type of horror pictures, invested with psychological implications, deal with mental states rather than melodramatic events. . . . The typical tale in the new genre crawls with living horror, is eerie with something impending, and socks its suspense thrill well along toward the middle of the story instead of doing the crime victim in at the beginning and then building a whodunit and a detective quiz as the element of suspense.

The piece doesn’t respect today’s genre distinctions. Apart from using the term “horror” in a way we wouldn’t, the author lumps together suspense thrillers like The Lodger, Hangover Square, The Uninvited, and The Suspect; the Gothic Gaslight (“a perfect example of the new approach”); and spy thrillers The Mask of Dimitrios and The Ministry of Fear. Even Jane Eyre is included, without irony. (Surprisingly, Double Indemnity from spring 1944 isn’t mentioned.) Still, the article acknowledges that mystery had strong audience appeal and that while the classic whodunit had had its day on the movie screen, films could be given new energy by other literary trends.

Mystery as artifice

Mystery is the only genre I know that makes narrative strategies as such central to its identity. A musical, a Western, or a science-fiction saga can be presented in linear fashion, telling us everything step by step, and still retain a genre identity. But a mystery plot can’t be presented straightforwardly. The writer must manipulate plot structure and narration to some degree.

A mysterious situation or plot action is one whose causes are to some degree unknown. In the detective formula, both refined and hard-boiled: A person has been murdered; what led up to it? In the Gothic: There are sinister goings-on in the house; what’s causing them? In the suspense thriller: Someone wants to harm me; who and why? (And will I escape?) To generate mysteries, the plot-maker must suppress key information. That can be done by opening late in the story (say, after the crime has been committed), by employing flashbacks (often launched from a climactic moment), or by restricting the range of knowledge (via a Watson or a string of eyewitnesses). More subtle options involve ellipses, such as those in The Murder of Roger Ackroyd and the diary portion of The Beast Must Die (1938).

At the level of prose style, clues can be buried in descriptions or offhand remarks. The narration can creatively mislead us from the start, in the title (The Murder of My Aunt, The Murderer Is a Fox) or the diabolical opening sentence of Carr’s “The House in Goblin Wood.” And sometimes you get pure showing off. The first chapter of The Rynox Murder Mystery (1931) is entitled “Epilogue,” and the last chapter is entitled “The Prologue.” In addition, the book is broken not into parts and chapters but “reels” and “sequences,” a device creating a small meta-mystery (gratuitously, so far as I can tell.)

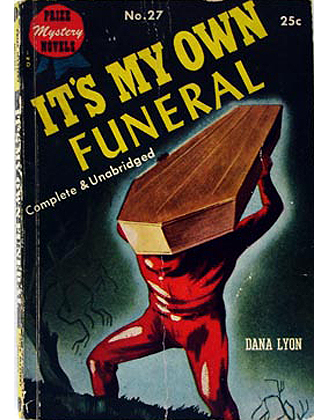

Given the proliferation and mixing of genres and the constant demand for innovation (echoed in Variety’s crack about things “being done too long in the same old way”), 1940s mystery writers were pressed to find new storytelling gimmicks. Everything had not been done, at least not yet. Historians of the detective story routinely praise the ingenuity of Christie and company in the 1930s, but the 1940s saw a positively baroque expansion of options. A dead detective pursues the investigation as a ghost. Another wakes up trapped in a coffin and starts telling us how he got there. Pat McGerr distinguished her work by replacing the question Whodunit? with others, such as: We know who’s guilty, but who’s been murdered?

Given the proliferation and mixing of genres and the constant demand for innovation (echoed in Variety’s crack about things “being done too long in the same old way”), 1940s mystery writers were pressed to find new storytelling gimmicks. Everything had not been done, at least not yet. Historians of the detective story routinely praise the ingenuity of Christie and company in the 1930s, but the 1940s saw a positively baroque expansion of options. A dead detective pursues the investigation as a ghost. Another wakes up trapped in a coffin and starts telling us how he got there. Pat McGerr distinguished her work by replacing the question Whodunit? with others, such as: We know who’s guilty, but who’s been murdered?

In the suspense mode as well, we find efforts to create novelty at the level of narration. With the emerging interest in psychoanalysis, the thriller began to probe the protagonist’s inner life and hidden traumas, producing not only the hallucinatory visions of Woolrich and Goodis but the crazy-lady divagations seen in The Snake Pit (1947), Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly (1948), and Patricia Highsmith’s early short story, “The Heroine” (1945). As in the purer tale of detection, a great deal depended on feints and fake-outs at the level of the prose. The cleverly misleading narration of Ira Levin’s A Kiss Before Dying (1953) turns on the use of a pronoun.

Hollywood filmmakers borrowed plentifully from the new genres, particularly the psychological thrillers that could appeal to women. Significantly, Rinehart’s pioneering 1908 novel was remade as The Spiral Staircase (1945), and Warner Brothers redid Collins’ classic Woman in White in 1948. Moreover, I think, filmmakers tried to find cinematic counterparts for the genre’s restricted narration, dream and fantasy passages, misleading exposition, and shrewd ellipses (e.g., Possessed, 1947; Mildred Pierce, 1945; Fallen Angel, 1945). The diversity of mystery fiction inspired Hollywood writers and directors to create a Golden Age of the mystery film, and the innovations of the period left a legacy for filmmakers ever since.

These genres had a wider impact too. That’s what I’ll concentrate on in my presentation, “I Love a Mystery: Narrative Innovation in 1940s Hollywood.”

The two major histories of mystery fiction are Howard Haycraft, Murder for Pleasure: The Life and Times of the Detective Story (1941) and Julian Symons, Mortal Consequences: A History from the Detective Story to the Crime Novel (1972). Both are very much worth reading, as is Leroy Lad Panek’s idiosyncratic An Introduction to the Detective Story. The best study of the 1920s-1930s puzzle tradition is Panek’s Watteau’s Shepherds: The Detective Novel in Britain 1914-1940. On A. B. Cox, see Malcolm J. Turnbull, Elusion Aforethought: The Life and Writing of Anthony Berkeley Cox.

The Variety article I quote bears the misleading title, “New Trend in Horror Pix; Laugh with the Horror.” It’s in the issue of 16 October 1944, p. 143.

Unlike The Rynox Murder Mystery, Cameron McCabe’s Face on the Cutting-Room Floor (1937) blends moviemaking and murder in a thoroughgoing, albeit wacko, fashion.

Other entries on this blog have dealt with some of my mystery favorites, especially Ellery Queen and Rex Stout.

P. S. 11 June: Mystery expert Mike Grost has kindly reminded me of his encyclopedic site, A Guide to Classic Mystery and Detection. By discussing authors both famous and forgotten, he displays the great diversity of this mega-genre.

Forking tracks: SOURCE CODE

Source Code.

DB here:

Who cares if the Source Code software is junk science? The muzzy premise forms the basis of an agreeable little thriller from the tail end of this year’s Dead Zone. Even if you don’t share my admiration for this movie, maybe I can persuade you that it points up an intriguing wrinkle in the recent history of American studio storytelling.

I surveyed this history in some books, but Source Code provides a nice occasion to update my argument. My main point remains: More than we often admit, today’s trends rely on yesterday’s traditions. Quite stable strategies of plotting, visual narration, and the like are still in play in our movies. When a movie does innovate in its storytelling, it needs to do so craftily. The more daring your narrative strategies, the more carefully, even redundantly, you need to map them out. The game demands clarity through varied repetition.

More generally, there’s a value in thinking of movies as combinations and transformations of inherited conventions. We’re used to considering conventions as matters of theme and genre, but I’m equally interested in conventions of technique and of narrative form. These are areas we’re still only starting to understand, although many entries on our site try to make progress in understanding changing norms of style and storytelling. (Check our Narrative Strategies category for further leads.)

If you haven’t seen Source Code, you shouldn’t read on. I reveal damn near everything.

He couldn’t come home

Colter Stevens awakes on a Chicago commuter train in the body of another man, Sean Ventress, who’s accompanying the attractive Christina Warren. Very soon the train explodes, and Colter reawakens in a pod in a military facility. He learns that after being shot down in Afghanistan he has been at the Nellis facility for two months, awaiting an experiment in “time realignment.”

Because a person’s brain activity does not cease immediately at death, memory modules can be accessed across an eight-minute period before full shutdown. Colter’s brain anatomy happens to be attuned to that of Ventress, so the experimenters can in effect insert his mind into Ventress’s body in the few minutes before the train explosion. The investigators know that the bomber is planning to set off a much bigger explosion in downtown Chicago, and Colter-as-Ventress could gather enough information to prevent it.

Under the tutelage of officer Goodwin and her superior, chief researcher Rutledge, Colter will be sent back in to the train, neurally speaking, to try to identify the bomber for them. He cannot prevent the train blowup, Rutledge insists. He can only hope to identify the bomber before the dirty bomb goes off downtown. But Colter can, in the shrinking time remaining, be sent back again and again, though it’s physically and emotionally punishing for him.

As a result, the film alternates between two zones of action. At the Nellis facility, time moves forward as Colter gradually comes to understand his circumstances and his mission. This action is under the pressure of a deadline: find the culprit before the dirty bomb is triggered. The other zone of action is the train, where the deadline is tighter (eight minutes before Ventress’s death) and the action is replayed as Colter tries different tactics to fulfill his charge.

Many incidents fill out this dynamic. In the pod, the early scenes are dominated by Colter’s efforts to understand the experiment he’s involved in and to grasp what has happened to him since his chopper crash. He is being kept alive artificially so that his brain activity can sync with Ventress’s. Eventually he breaks through Goodwin’s façade of coldness, converting her to sympathy for his plight. When she finally stares compassionately down at his broken body in its glowing casket, she resembles a mother or nurse looking down at a baby. On the train, the early scenes throw up some decoy suspects, most prominently an agitated man of vaguely Middle Eastern appearance. He is proven not to be the bomber, who’s eventually revealed as a dough-faced nerd. (Between the stereotyped Islamic terrorist and the stereotype domestic one, the plot opts for the latter.)

Colter not only blocks the Chicago bombing; with Goodwin’s help he is sent back one last time to stop the train bombing as well. In the course of that effort, he manages to reset the past, creating a parallel world in which the briefcase bomb never ignited and the bomber was captured before he left the train. Colter, dead at the Nellis facility, becomes Ventress wholly, able to spend a day with Christina and to send a text message to Goodwin promising that the Source Code has even bigger possibilities than Rutledge imagines. It can change the course of events. And she can reassure Colter’s original self, when he finally is sent on a mission: “Everything’s gonna be okay.”

It’s the new me

This plot is articulated in quite traditional ways. At less than 90 minutes, the film yields three large-scale parts or “acts.” The Setup introduces us to the premises, establishing the train bombing and the Nellis facility supervision; I’d argue that this ends at about 28 minutes. At this point Colter, has to rule out his chief suspect, the commuting businessman with motion sickness, when the train explosion takes place. The second stretch of the plot consists of more failed efforts, but culminates at about 56 minutes, when Colter correctly identifies the bomber, Derek Frost. Again, he can’t forestall the train bombing, but returning to his capsule he passes the key information to his masters, and they can arrest Derek before the dirty bomb hits Chicago. At this point his official mission is over. But the movie isn’t. Colter persuades Goodwin to let him go back one more time to stop the train bomb and save the passengers—effectively countermanding Rutledge’s injunction that the past can’t be altered. A three-minute epilogue starting around 82:00 wraps things up.

Filling out this structure is the characteristic double plot of classical Hollywood: heterosexual romance plus another, usually connected, line of action. The suspense plotline is organized as a series of goals, initially articulated by Goodwin. She tells Colter to find the bomb, which he does in the first replay. But as he can’t prevent the explosion, he needs to know more about who’s behind it. His next passes proceed in steps. He has to identify the guilty passenger; then he must try to steal the conductor’s pistol; then he searches for bomb-related paraphernalia.

About halfway through the film, however, Colter conceives purposes of his own. Inside the capsule, he probes Goodwin about what has happened to him. On the train, he starts to investigate the insignia of the agency controlling him, to trace his own fate in Afghanistan, to try to contact his father, and to phone the Nellis facility. He’ll eventually succeed in all these attempts, balancing the failures of the first chunk of the plot. Ultimately he’ll decide to try to save the train. Crucially, this last goal is formulated after he believes that having been more or less killed in Afghanistan, he is about to be terminated by the Source Code project. So he can now operate in a mode of pure self-sacrifice. As often happens in a classical film, a character finds the resources to throw off others’ demands and make decisions on his own.

In the romance plotline, by assuming the identity of Sean Fentress, Colter becomes attached to Christina. Now saving the train takes on a more personal weight; he will be saving her. The emotional dimension here is deepened by Colter’s backstory, his unresolved relation to his father. Eventually he is able to get closure by posing as Fentress and phoning tell the grieving old man that Colter indeed loved him. In screenwriters’ parlance, Colter is “exorcising his demons.”

Colter’s growing confidence in dealing with his past and the bomb threat changes his behavior toward Christina. No longer the skittish neurotic of his early incarnations, he becomes brisk and confident. Eventually he can relax, paying the standup comic across the aisle to entertain the other passengers. As often happens, character change is measured by a repetition. The first time Colter says, “It’s the new me,” he refers ironically to his discovery that he’s in another man’s body. But now, as the comic launches into his shtick, Christina points out that her companion has changed. He answers by saying, “It’s the new me,” which signals a deeper acceptance of his sacrificial role. He doesn’t expect to survive after he returns to the capsule, but he has saved the people on the train and he can for a moment celebrate a final moment of vitality.

This is not a simulation

These cascading goals and character arcs emerge gradually, thanks to cunning narration. At first we’re restricted largely to what Colter knows, but gradually our awareness widens. We come to learn about Goodwin’s role in the Source Code project and about Rutledge’s ruthless efforts to use Colter as a test case. By the climax, the film cuts freely between the two arenas, the train and the Nellis compound, creating classical suspense as Goodwin postpones erasing Colter’s memory while he races to prevent the train blowup. This is the Griffith heritage of the last-minute rescue.

For the viewer, the film starts with mystery—Colter is on the train and he doesn’t know who he is—and moves toward a mixture of curiosity about his past and suspense about how he will solve his problem. By the start of the climax, we have understood all the forces converging on Colter’s last mission, and sheer suspense takes over. There is, though, one final surprise, which seems to have worried other critics more than it does me. More on this shortly.

Even before the explicit widening of narrational knowledge, we’ve been given a dose of something enigmatic. The shifts from the train explosion to the Nellis pod are provided with whooshing transitions of blurred and fragmentary imagery that, as the film goes on, clarify a bit. At the film’s center, these images will be replaced by distorted flashbacks to his helicopter crash in Afghanistan, a passage that leads him to ask Goodwin: “Am I dead?”

One of the images glimpsed in the vortex montages is that of Anish Kapoor’s Cloud Gate sculpture, which Christina and Colter-as-Sean will visit in the epilogue.

Thematically, the image can be taken as an emblem of the lives Colter has saved, with a hazy overlay that reminds us of his floating consciousness for most of the movie. But the more basic question is about the status of these blurry visions. Are they Colter’s premonitions of a future to come? That assumption seems confirmed at the end when Colter, staring at the sculpture, asks Christina if she believes in Fate. At the same time, the images can be treated as coming from outside his ken, as if the film were providing teasing hints about how the action will resolve.

In these montages we see an interplay between destiny and chance common in Hollywood storytelling. (Christina answers Colter’s question by saying she’s “more of a dumb luck kind of girl.”) Very often, even if chance seems to govern the plot, a film’s overarching narration seems to “know” how things will turn out. Thus the film can have it both ways, acknowledging that life sometimes depends on chance but also recognizing that satisfying stories feel inevitable.

As usual, you will have eight minutes

Since the early 1990s, many films have resorted to what we might call“multiple-draft” plotting, the replaying of key scenes with important variations. Groundhog Day (1993) is our prototype, and it influenced Source Code screenwriter Ben Ripley. An earlier instance is the alternative futures revisited by Marty McFly in Back to the Future II (1989). Yet these films revived an older, although minor, trend going back quite far in Hollywood. The device was sometimes used to present alternative futures, as in The Love of Sunya (1927), but more commonly it presented different characters’ versions of what happened in the past. We find it in the courtroom drama Thru Different Eyes (1929), which dramatizes conflicting trial testimony, and in Crossfire (1947), which somewhat anticipates Rashomon‘s use of the strategy. Contradictory replays are used for more comic effect in The I Don’t Care Girl (1953) and Les Girls (1955).

What led to the resurgence of multiple-draft storytelling in our day? Partly, I think, the changing genre ecology of Hollywood. During the 1970s and 1980s, certain genres like the musical and the Western faded out, and horror and science-fiction/ technofantasy became more important. These genres, still going strong today, encourage playing around with subjective states (dreams, hallucinations), devising misleading narration, and creating branching and looping timelines (through time-travel, telepathy, multiverses, and the like). The filmic experiments probably owe something as well to the rise of popular writers in the vein of Stephen King and Michael Crichton, along with the revival of the work of Philip K. Dick.

Pop science also furnished new narrative possibilities. Researchers discovered the Butterfly Effect: change one little condition at the start of a process, and you get a different result. There was the Forking-Path, or Choose Your Own Adventure, option, whereby you can imagine taking a different path in your life. And there was the Multiple-Universe Hypothesis, whereby we can hop from one parallel world to another.

Even without the pseudoscientific justification, the reset-replay option showed up in films that were influenced by earlier storytelling. Film noir sometimes resorted to replaying scenes in ways that filled in information missing on the first pass (e.g., Mildred Pierce, 1945). Tarantino made no bones about being influenced by the overlapping flashbacks in The Killing (1955), themselves derived from Lionel White’s original novel Clean Break. So in the wake of Reservoir Dogs (1992) and Jackie Brown (1997), we got many thrillers and crime films that retold the same events from different characters’ viewpoints (Out of Sight, 1998), right up to an almost endless series of replays (Vantage Point, 2008).

All of these multiple-draft tactics made their way into global cinema too; Run Lola Run (1998) is a prominent example, but so too is the dazzling anime The Girl Who Leaped through Time (2006). In America, the market’s constant demand for something novel (but not too novel) pushed filmmakers toward all the variants we see in films as different as Thirteen Conversations about One Thing (2001) and Confidence (2003).

For mainstream filmmakers the key is redundancy. The reset-replay device has to be explained through dialogue, diagrams, intertitles, and sheer repetition so that we understand it going forward. (Contrast, say, Primer, which left most viewers behind.) Once we’ve grasped the similarities in the core situation, we can measure the differences in each iteration.

Source Code director Duncan Jones had already shown an interest in replays in Moon (2009), with its Möbius-band treatment of the crashed lunar vehicle, followed by Sam’s awakening in the infirmary. The mystery of the first encounter, in which Sam seems to find another version of himself in the vehicle, gets slowly cleared up through dialogue, the discovery of a secret repository, and not least important, a bandaged hand wound that allows us to keep the two Sams more or less distinct. Similarly, in Source Code, the returns to the train can be more elliptical as we master the situation: the introductory shots (duck pond, Colter waking up) can be skipped or compressed. Our training is guided by Colter’s, as he starts to predict the trivial incidents (coffee spill, cellphone call from Christina’s ex) and handle them matter-of-factly. These repetitions anchor us and allow us to register the different actions he undertakes in each module.

Those modules are ruled by another convention, what screenwriting manuals call the ticking clock. Usually reserved for the climax of films in all genres, even romantic comedies, the ticking clock plays a bigger role in Source Code. It governs both the macro-level (the deadline to stop the dirty bomb) and every return to the train. Strikingly, those replays are very strictly contained. Colter is assigned eight minutes for each mission, and by my count each of the developed train episodes before the climax consumes anywhere between four and eight minutes of screen duration, never more. His recurring deadline becomes a structural cell of the movie.

We have a chance to start over in the rubble

Déjà vu.

Multiple-draft storytelling promises to abandon the classic “linearity” of Hollywood storytelling, but the promise is largely a tease. The convention gestures toward unruly complication, but it tends to reinstall linearity, sorting everything out and making the final stretch of the film seem a logical consequence of what went before. Despite all the cycles and skip-backs of Groundhog Day, Phil changes incrementally into a kinder person and gets the woman he has come to deserve. In the money-drop sequence of Jackie Brown, the minute variations of point-of-view mesh into a single comprehensive account of how the scam went down. Part of the fascination of the technique for us may be similar to what a child feels after spinning around and stopping: the dizziness is fun, but so too is the bumpy readjustment to a stable world.

Source Code wants a happy ending. Does it prepare us sufficiently? We have the vortex transitions that look forward to the Cloud Gate epilogue, but are these enough? Don’t we need something at the level of plot action?

In his last visit to the train, Colter manages to disarm the briefcase bomb and capture Derek Frost. So now the train didn’t explode; the Nellis facility was never put on alert to forestall the dirty bomb; Rutledge and Goodwin never tried using Colter as their Source Code guinea pig. Rutledge earlier denied that this revision of the past would be possible, but the plot nonetheless moves us into a parallel world characteristic of forking-path plots like Run Lola Run and The Butterfly Effect (2004). And this reality has become sovereign, since Colter can now successfully send Goodwin a text message advising her about the unexpected success of the Source Code stratagem. This also means that as more or less a brain in a vat, the wounded Colter survives to serve in other missions.

Given the right sort of motivation, then, the forking-path option can be activated as a resolution device for multiple-draft plots. The film’s makers invoke a multiverse explanation explicitly in one piece of publicity for the film (trailer 2 here). More important, we’re prepared to accept such a switch on pretty slender evidence. Counterfactual thinking in terms of forking paths is a part of our folk psychology. If only we’d left the parking lot ten minutes earlier, we wouldn’t have hit this traffic. If I hadn’t taken this job, I wouldn’t have met my husband….and so on. Despite what experts like Rutledge say, when we see Colter disarm the lethal briefcase, we’re prepared to buy the possibility that everything afterward has changed.

Still, we need some elements in the movie itself to justify the jump. During his final questioning of Goodwin, Colter asks if she could imagine a world in which she didn’t get divorced, being “a woman who took a different fork in the road.” Colter insists that the course of events is changeable: Christina “doesn’t have to be dead.” At various points he says he thinks he can save the train, but like Rutledge, Goodwin reasserts that there’s only one reality, and its events have already happened.

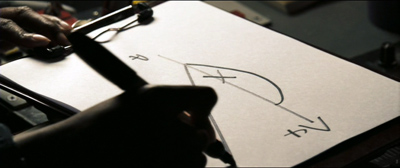

Interestingly, the debate itself might be a minor convention of the multiple-draft plot. In Tony Scott’s Déjà vu, (2006) a close analogue to Source Code, two scientists disagree about whether the past is malleable. Professor Denny says that you cannot change what’s already happened. “God’s mind is made up about this.” But his colleague Shanti adheres to the “branching universe theory,” which she helpfully draws on paper for our benefit (echoing Doc’s famous diagram in Back to the Future II). A significant event, Shanti maintains, can shift the course of events and create a new path. It can even, she claims, wipe out the branch that was initially taken as baseline reality.

Images of linearity deflected, of hiccups and branches off a main line, show up in Source Code too. The train bomb is fired off just as another train passes on a parallel track. But in the final replay, after Colter has set things right and paid the comedian to do his turn, we see “all this life”—the passengers frozen in amusement. The shot is a kind of marker that, as Shanti puts it, something big has changed. Abruptly we get a shot we haven’t seen before: a high angle of our train switching to another track. Then we cut back to Colter and Christina about to kiss, as the rival train passes safely. Our train’s new trajectory confirms that an alternate reality has been put in place. It also echoes an earlier line, when Christina, talking about her plans for the future, asks Colter: “Am I on the right track?”

This will end

Source Code appropriates the forking-path option in order to arrive at a final draft of Colter’s fate. This stratagem reflects a common tendency in the history of narrative forms. Over the years, as readers become more skilled in picking up conventions, authors can be more elliptical and oblique. Descriptions can be more bare-bones, and authorial commentary can be given in a phrase rather than a paragraph. (Elmore Leonard: “I leave out the parts that readers skip.”) Films that once needed to motivate alternative futures through dreams or fortune-telling now do so through scientific gadgetry, or just by referencing similar movies.

We surely lose something in a trend toward such laconic storytelling, but there are gains in speed and impact. What Déjà vu debates for minutes can be abbreviated in Source Code because audiences have caught on: a few cues suffice to let us figure out how this sort of story goes. For me, the very premise of the replay device, plus Colter’s raising the issue of forking paths with Goodwin, plus our commonsense psychology, plus the swooshes, plus the convention of the happy wrapup, not to mention the overall urge to reward our our hero for all his sacrifice—all this is enough to push the ending over the finish line.

More generally, you can invoke Steven Johnson’s argument that we’re getting smarter about picking up quickly-emerging conventions. Popular culture, he claims, is more intellectually demanding than it used to be; examples would be The Wire and Lost. I’m not wholly convinced, since Our Mutual Friend and other items consumed by generations past can be pretty complex, and twentieth-century middlebrow artists like Thornton Wilder, J. B. Priestley, and Alan Ayckbourn have flirted with formal experiment. I’d relate the intricacy of some popular narratives partly to the proliferation of more niche genres and specialized publics, along with the growth of pop connoisseurship. Aging hipsters and cool college-educated youngsters, fortified with high disposable incomes, now flaunt a nerdy side and enjoy avant-gardish innovations.

For whatever reasons, in a lot of mass storytelling, form is the new content. But that newness depends considerably on recasting long-standing traditions. Nothing comes from nothing. And it can be fun to trace the fluctuating dynamic of novelty and familiarity as it emerges in the movies that we see right now.

At Electric Sheep Duncan Jones elaborates on the forking-path dimension of his film.

This entry builds on work I’ve done elsewhere. For more on classical conventions of plotting and narration, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960, part one, and Narration in the Fiction Film, Chapter 9. On recent narrative innovations and their relation to classical premises, see The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies, 51-103. On forking-path plots and their relation to folk psychology, see the essay “Film Futures” in Poetics of Cinema. One essay in that volume discusses Mildred Pierce‘s tricky replay of the opening murder, while another surveys another contemporary trend, the network narrative.

On dividing a film’s plot into parts, see Kristin’s earlier entry and my essay on Mission: Impossible III. Go here to see what happens when Archie Andrews takes a forking path.

Yes, there’s something similar to be done with The Adjustment Bureau. But I leave that to others.

Source Code.

It was a dark and stormy campaign

How do you get people to believe that if you can’t get the press to make an honest assessment of it? You tell a story. “When it came down to a choice between my very life and my country, I chose my country.” That’s why the story’s important. Just as Obama’s story is important to him. I don’t gainsay it. You know, tell your story! —John McCain staff member and co-author Mark Salter

There was a mismatch between the way he was behaving and the narrative the press had bought into. It made reporters wonder, “Have we been had?”–Professor Marion Just, Wellesley, on John McCain

This political bullshit about narratives.–Peggy Noonan, Republican columnist

I’m David Bordwell and I approved this message.

A long time ago a student complained to me that we film academics were foisting upon them words that no professional filmmakers used. The student’s example was “genre.” Today of course filmmakers use the term all the time. Sometimes you hear “classical filmmaking,” and Variety tells us that Henry Jenkins’ label “transmedia” is starting to break through:

Famed s/f writer Larry Niven is working with “transmedia” (today’s new buzzword) production company Alchemic Productions to create a new game property called “Free Fall.”

More broadly, the terminology of Big Theory in the humanities has trickled into journalism and politics. For some time now “deconstruction” has been peppering mass-market discourse. Granted, it’s not employed in the way Derrida and his acolytes would like. It seems to mean a blend of “construction” and “destruction,” which can entail “analysis” or even just “pulling something apart.”

Deconstruct Black Ink: Your children can use chromatography to deconstruct black ink and find out what color the ink really is.

Scientists Deconstruct Clownfish Chatter

U. of Kansas Looks to Deconstruct Its School of Fine Arts

This election season has shown me that even the idea of the Other, considerably divorced from its use by Jacques “The Lack” Lacan, can show up. Nicholas Kristof claims that John McCain’s efforts to suggest that Barack Obama isn’t “sufficiently Christian” are an effort to “otherize” him.

But I think the term that has gotten the most play is “narrative.”

Discovering narrative

During my days as an undergraduate in literary studies and as a grad student in film studies, between 1965 and 1973, you scarcely ever heard the word. It doesn’t appear in the index of Wellek and Warren’s Theory of Literature (3rd ed., 1956) or Wimsatt and Brooks’ Literary Criticism: A Short History (1957) or Northrop Frye’s Anatomy of Criticism (1957). Story, tale, plot, dramatic structure: these words were common, but not “narrative”.

In American academia, the term began to gain currency with Robert Scholes and Robert Kellogg’s The Nature of Narrative (1966). The authors identify narrative with a broad literary tradition, embodied not only in the novel and short story but also in oral storytelling. And the definition is clearly language-based, in pointed contrast with drama.

By narrative we mean all those literary works which are distinguished by two characteristics: the presence of a story and a story-teller. A drama is a story without a story-teller; in it characters act our directly what Aristotle called an “imitation” of such action as we find in life. (4)

The Nature of Narrative was published the same year that Roland Barthes, in a special issue of the French journal Communications, published his essay “Introduction to the Structural Analysis of Narratives.” (1) His conception of narratives (récits) is far more generous than that of Scholes and Kellogg.

Narrative is first and foremost a prodigious variety of genres, themselves distributed amongst different substances—as though any material were fit to receive man’s stories. Able to be carried by articulated language, spoken or written, fixed or moving images, gestures, and the ordered mixture of all these substances, narrative is present in myth, legend, fable, tale, novella, epic, history, tragedy, drama, comedy, mime, painting (think of Carpaccio’s Saint Ursula), stained glass windows, cinema, comics, news item, conversation. (79)

Barthes’ essay, along with other Structuralist studies, initiated the academic field of “narratology,” the systematic study of storytelling as it is manifested in many media. From the 1970s to the present, this became a vast, varied, and exciting area of inquiry.

The questions are fascinating.

*What is a story? How does it differ from other things, such as a description or an abstract image? Are jokes narratives? Are dreams? Are riddles? Is the concept so broad that anything can be treated as a story?

*Why do stories engage us? What do we need to know, or do, to understand a story? What powers enable us to create stories? Are story-making and story comprehension distinctively human activities?

*Do stories rendered in language differ from those rendered in other media? Is the ability to make or follow stories dependent on our knowing language, even if the story is presented without words (as, say, a silent film)?

*How do narratives imply or suggest or symbolize broader meanings than the bare events they recount? What enables a narrative to stand for more than it seems to say?

*What patterns of narrative construction do we find in different traditions, periods, times, and places? How might they bear the traces of social and political views? How might they express varying conceptions of the world?

In retrospect, we can see that Aristotle, nineteenth-century theorists of the drama, and theorists like Walter Benjamin, Georges Polti, R. S. Crane, and Northrop Frye did reflect on the phenomenon as narratologists were beginning to conceive it. But very few thinkers had asked these particular questions, in quite the way that Barthes and other Structuralists had.

The questions may seem impossibly abstract or broad, but they get more manageable if we look at particular cases. Take film. We all assume that Hollywood movies belong to a storytelling tradition, one that some people consider formulaic. But if Hollywood movies are formulaic, they must adhere to conventions—conventions we might not find, say, in Homer’s epics or Ibsen’s dramas or Neorealist films. What are those narrative conventions? Where did they come from? How do they fit together? What might be their effects on viewers’ beliefs and experiences?