Archive for the 'Hollywood: Artistic traditions' Category

Five critics, one of them a killer

Goodfellas (1990).

DB here:

Fourteen months of being house-bound gave me plenty of chance to catch up on my reading. But the reading was almost all devoted to the book I was writing on mystery plots in fiction, film, and other media. Now that it has been catapulted out to unwary publisher’s readers, it’s time for me to catch up on some 2020 books I like. In this batch, all have a connection to film criticism, and murder, attempted or consummated, creeps into more than one.

Movies for Muggles

Somebody ought to write a history of the one-movie monograph. Early on there were picture books, and roadshow attractions often produced pretty laminated books as souvenirs, filled with PR stories and color images. My vote for the first analytical monograph would be the very ambitious Tu n’as rien vu à Hiroshima! (1962). In the early 1970s, American academic presses began offering critical studies of single films; an early example was the FilmGuide series edited by Harry Geduld and Ron Gottesman. (My favorite entry was Jim Naremore‘s study of Psycho.) Since then many publishers have pursued the format, usually as part of a series.

Now we have 21st Century Film Essentials, newly launched at the University of Texas Press. The first two entries are pretty canon-busting. Dana Polan writes on The Lego Movie, and Patrick Keating on Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban. I haven’t seen Polan’s book, but Keating directly takes up the challenge of the series.

As a franchise film, as a work of digital cinema, as a work of collaborative authorship, and above all as a thoroughly engaging demonstration of the art of storytelling, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban is an essential work of twentieth-first century cinema.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

I confess I was skeptical, and still am a little. But Keating’s meticulous analysis and interpretation of the film does convince me that this is a ripe example of modern “hyperclassical” cinema. By that I mean a dense, “through-composed” revision of traditional narrative strategies and film techniques, working smoothly together to create effects at many levels. A hyperclassical film is more thoroughly classical than it “needs to be.” In other words, here’s another counterexample to the notion that “post-classical Hollywood” shows a collapse of traditional norms.

Keating’s argument for the film’s richness, I think, revolves around two central concepts. First is that of narrative viewpoint. Virtually all of Azkaban, unlike the earlier entries in the franchise, is filtered through the consciousness of Harry. We’re attached to him as he experiences the action. That doesn’t, Keating hastens to add, make the film radically subjective; indeed, there are relatively few shots from Harry’s optical viewpoint. Attaching the unfolding plot to a character doesn’t rule out a wider perspective, if only because cinema puts him within a wider frame of a shot or an edited sequence. There’s always the possibility of our registering action or other characters’ reactions. The end of the Quidditch flight is thick with these impacted viewpoints, and elsewhere Cuarón’s constantly moving camera nudges us toward implications that supplement, or sometimes contradict, what Harry is concentrating on.

Keating’s other main concept is connected to the broadening of viewpoint: worldbuilding. This idea is obviously central to Rowling’s achievement, as it has been to franchises since Star Wars. But Keating lifts the idea to a central role in how films engage us. The richly realized world of Potter is only an extreme instance of what every narrative does. Borrowing from critic V. F. Perkins, Keating suggests that any film narrative supplies us with the possibility of many stories that are only hinted at, or merely latent.

Most movies prune those secondary offshoots, the better to force us to concentrate on our protagonist. But Tom Stoppard showed that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern deserved their own play. Similarly, franchise films, with the ever-present prospect of sequels, crossovers, or reboots, make us aware that any character, even any item of furniture, secretes a new story, or a bunch of them. The Potter films are committed to this spinoff aesthetic, packing in as many suggestions of sidestories as the screen will bear. This principle finds tangible expression in the portraits jammed into the Gryffindor common room and dorms guarded by the Fat Lady.

Overwhelming us with characters and situations, many in motion, this gallery is perfectly in keeping with English traditions of floor-to-ceiling decor. It’s also a groaning feast of other stories that could yet, somehow, intersect with Harry’s fate. Keating’s shrewd commentary on worldmaking is one of the book’s highlights.

Keating ties these ideas to phases of production and division of labor, reviewing how the novel’s viewpoint and worldbuilding strategies are transposed and extended by script, camerawork, editing, performances, set and costume design, and music. Throughout he weaves what he takes to be the film’s binding theme, that of time. Is the future preordained, as Ms. Trelawney insists in her frantic, fumbling lectures? Or is it open, as Hermoine and others tell Harry? This makes the film’s tour de force climax with the Time Turner into a synthesis of restricted viewpoint (we’re with Harry as he witnesses an alternative future) and worldbuilding (the future is what you make it).

I might quarrel with Keating’s suggestion that the impulse driving Harry’s action is a struggle with the dementers. I saw his relation to Sirius Black as more than the subplot Keating considers it. Overall, though, Keating has produced not only a subtle, supple analysis of the film but also a model for how to understand cinematic storytelling in the age of the blockbuster.

Wiseguy’s progress

If Keating’s book is a classical sonata, Glenn Kenny’s Made Men: The Story of Goodfellas is bop. Keating offers a tidy analysis through crisply defined categories. Kenny provides a hardcopy approximation to a packed DVD.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

At the center is a 150 page scene-by-scene account of the film: a commentary track in your hands. Alongside that sit chapters that function as bonus materials. They include a brief introduction to the filmmaker just before he started work on the film, chapters on preproduction, the music (Kenny is an expert on pop and rock), the editing, the critical reception, and the ultimate fate of the real-life protagonist Henry Hill. Then, like the narrator of a Criterion video supplement, Kenny surveys Scorsese’s career after Goodfellas. Finally, an epilogue is virtually a monologue: Scorsese talks almost without interruption for twenty-five pages, as if this were the interview rounding off the disc. There’s also a bibliography, a timeline of the production, and the recipe for Henry Hill’s ziti.

It’s overwhelming. Kenny has evidently read everything about the real-life sources of the story, and his interviews turn fan service toward crime reporting. It is no small thing to pursue hard cases who were recruited for bit parts. Kenny has also garnered a lot of information from staff like AD Joseph Reidy, who are seldom given much attention. Keating would probably be happy to see Kenny’s narrative splinter into stories leading to other stories, such as the effects of the film on the careers of Barbara De Fina and Ileanna Douglas.

I compared the book’s central chapter to a DVD commentary. Anybody delivering a voice-over play-by-play regrets that you have to keep up with the film and can’t devote as much time to a big scene as you might like. Thanks to the print format, Kenny is able to pause the film and spiral out from it to fill in backstory or behind-the-scenes dynamics.

Early on, he can give us three pages on Tuddy, both his original (who died in prison) and Frank DiLeo, the actor playing the role. Kenny explains that DiLeo was a music executive who oversaw Michael Jackson’s “Bad” video, which included a Wanted poster of Scorsese in a subway scene, which ties to a sneaky reference to the “Smooth Criminal” video featuring a character named Frank Lideo, played by Joe Pesci. . . well, you get the idea. Likewise, in an astonishing cadenza, Kenny identifies every actor and wiseguy in the long POV tracking shot in the Bamboo Lounge.

His account of the cast rummages through filmographies and personal histories, and adds the sort of oversharing we welcome: “Behind the placid mook mug seen in the movie was a remorseless killer.”

All these exfoliating tales don’t conceal a sustained performance of film criticism. Kenny’s governing idea is that Goodfellas cons us through a bait and switch. Lured in by a rapid-fire opening that arouses a bemused attraction to these bad boys, we’re gradually forced to a more sober, even horrified, realization of their moral and emotional brutality. I think that this fairly reflects most viewers’ experience. But how does the trap work?

Kenny plots an “arc of disengagement” between the killings of Tommy and Spider. A rise-and-fall pattern links the parallel scenes of the Bamboo Lounge, the Copacabana, and the shabby tavern where the gang meets to whack Morrie. Kenny draws nuanced comparisons with The Godfather and is very detailed on Scorsese’s visual techniques, particularly the freeze-frames and fadeouts, which usually get less attention than the flashy camera moves. One of the book’s main points is that Scorsese, newly aware of how TV commercials trained viewers in quick pickup, deliberately decided to make his fastest-paced movie. And of course the music is central to managing our mood and commenting on the story.

As a seasoned reviewer, Kenny can write. “Frisky newlyweds still hot for each other; you love to see it.” Henry (“a walking appetite”) eventually pulls Karen into his schemes: “The revitalized marriage will find its sense of twisted teamwork.” And digression is welcome when it humanizes the author. Listening to Sid Vicious’ version of “My Way” is comparable to “say, eating the fried chicken from the Kansas City restaurant Stroud’s for the first time.” (The “say” makes the sentence.) A movie about food begs the critic to sample a little synaesthesia, with music evoking mouth-watering chicken. Come to think of it, that linkage of music and food is in Goodfellas too.

I especially enjoyed Kenny’s rebuke to fans who bust this carefully constructed work into “movie moments.” You probably know that one school of criticism thinks that films are more or less loose assemblages of scenes, out of which certain instants become incandescent. Certainly there are such moments in many movies, and sometimes they stand out from a gray pudding. But often strong moments ravish us because they’ve been prepared for by careful craft. So Kenny’s guided tour of Goodfellas shows its affinities with Keating’s holistic approach:

Serrano and his crew reduce movies to anthologies of “cool” or shocking moments, as opposed to fictions whose circumscribed worlds aspire to create beauty or sorrow or horror or joy in some formally coherent whole.

Mon semblable, mon frère.

Dead end at the ocean’s edge

La La Land (2016).

On the other hand, I ought to be out of sympathy with Mick LaSalle’s Dream State: California in the Movies. It’s unabashedly reflectionist, tracing how films project contradictory images of the Golden State. The screen image of California promises pure self-fulfillment, but that leads to loneliness, danger, conformity, and loss of dignity. If Kenny and Keating see movies as made by an army of artisans, LaSalle treats them as springing full-blown from American mythology. There is barely a mention of a director, let alone a sound mixer, in his account.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

Instead, California-ism makes its way to the screen through a surge of a “collective mentality.” For instance, the blockbusters’ endless images of urban annihilation spring from “a people disseminating and celebrating visions of their own obliteration. . . . Something is seriously wrong with the nation producing such visions.” He suggests that “the fear of extraterrestrials is the disguised fear of illegal aliens. . . . the fear of the apocalypse is the disguised fear of terrorism.” Hollywood takes dictation from mass anxieties.

I’ve explained elsewhere (here and here) why I find such claims unpersuasive. I think that reflectionism is every smart person’s mistaken idea about cinema. But sometimes, as with Susan Sontag’s essay “The Imagination of Disaster,” a reflectionist account of a film can activate some valuable ideas and information along the way, and it can host some entertaining writing. These benefits, I think, emerge throughout Dream State. In kaleidoscopic bursts, LaSalle provides suggestive takes on movies familiar and obscure, and the way they link to one another.

For example, he tracks recurring plot patterns. There’s California’s version of the One Great Night, when individual transformation takes place in a few hours of turbid activity (Superbad, Modern Girls). American Graffiti is the prototype, and in just two pages LaSalle evokes the way audience knowledge races ahead of the characters, far into the future. (Curt winds up in Canada, which probably has to be explained to young viewers today.)He’s very good on the cost-of-stardom plot, from What Price Hollywood to La La Land, this last the only film that faces the fact “that every great advance requires sacrifice, and that even though there is nothing like the joy of first love , there is nothing more important than the fulfillment of one’s inner self.”

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

LaSalle considers our willingness to take stars as surrogates for us, and here I was reminded of another critic who tried to pierce the Hollywood Hallucination, the great Parker Tyler. He had, I think, a more meta attitude toward the movies, since he avoided straight reflectionism by treating every film as a charade, a narcissistic exercise in make-believe. For Tyler, Hollywood movies were always primarily about Hollywood, filled with symbolic surrogates for their makers and their viewers. In this respect, LaSalle’s opening chapter is agreeably Tyleresque, positing The Wizard of Oz as a film enacting the flight to a dream city; the Emerald City as Hollywood. Like Tyler as well, LaSalle searches for what he calls a movie’s complex finish, as with a glass of wine. Wizard ends not on a note of ambiguity exactly, but on something like a chord that sets off contrary overtones. Tyler’s books were built on this chord.

Another critical avenue that LaSalle opened up for me was iconographic: the differences between LA movies and San Francisco movies. He deftly contrasts the ambience and topography of the cities. Noir and disaster films are primarily anchored in LA, while San Franciso movies tend to be steeped in nostalgia (e.g., Jobs, Milk). He keeps finding new angles to comment on. Avoiding the obvious effort to discuss California’s boom during and after the war, he skips back to the months around Pearl Harbor to bring to light films, mostly exploitation quickies like Secret Agent of Japan and Little Tokyo, USA, that rushed to treat Japanese Americans as potential spies. Meanwhile, the unoffending citizens were shipped off to internment. On a lighter note, anybody who’s bold enough to praise Gidget as a more mature film than Easy Rider gets my admiration (and agreement).

LaSalle, who came to California from the east, weaves in bits of memoir that highlight his main theme. And like Kenny, he writes with conversational wit.

“Home is horrible. Oz is horrible, too. . . but at least it’s in color.”

On Saturday Night Fever and Grease: “One seems tough, but it’s soft. (Of course, that’s the New York film.) One seems soft, but it’s hard. (Of course, that’s the Los Angeles film.)”

In Hollywood “integrity is so original it might just work as a strategy.”

In Out of the Past, “sex can kill you, but it’s worth it anyway.”

In San Francisco (1936) “if only to get Jeanette MacDonald to stop singing, the Earth had to intervene.”

Contrasting Monterey Pop to Woodstock‘s utopian fantasy, LaSalle nearly had me on the floor.

This is a model? Hundreds of thousands of intoxicated people, unable to wash, all but sitting in their own slop, cheering for a series of aristocrats that swoop down to entertain them and then leave? Meanwhile, the army flies in food and the slave classes clean out the Port-O-Sans? That’s sustainable as a societal model?

In addition to all this, through engaging appreciation, LaSalle has prompted me to seek out a great many films I hadn’t heard of. That’s another duty of the good critic. After seeing so much–pounding the beat every day–the movie reviewer can steer you to new discoveries.

Cinephile into cineaste and back again

He Said, She Said (1991).

All of these critics have participated in filmmaking. Mick LaSalle has written and produced documentaries. Glenn Kenny has been an actor in several films (including Soderbergh’s Girlfriend Experience). Patrick Keating, who has an MFA in cinematography, has been a DP on independent projects. Reciprocally, director Ken Kwapis started out wanting to be a film critic–in third grade, no less.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

In college he devoured classic movies and gorged on film criticism. Kwapis went on to become a director of consequence, overseeing many features (Sisterhood of the Traveling Pants, He’s Just Not That into You) and TV episodes (The Garry Shandling Show, The Office). Yet he didn’t leave his cinephilia behind. But What I Really Want to Do Is Direct: Lessons from a Life behind the Camera has an intellectual heft rare in career memoirs and moviemaking manuals. It’s at once thoughtful and practical, suffused throughout by an ethic of modesty, tenacity, and what I can only call a desire to remain both a good artist and a decent person. It also contains some first-rate film criticism.

Kwapis intercuts three sorts of chapters. There is the chronological account of the filmmaking process, with advice on taking meetings, establishing rapport on the set, giving actors “playable notes,” and coping with postproduction and marketing. Kwapis insists at every turn that you need to be both firm and flexible, open to every suggestion from the production team but still adhering to your conception of the project.

But this is not auteurism on steroids. If you’re not a Spielberg or a Nolan, the director has to learn tact and strategy. Kwapis emphasizes not abstract technique but the interactive, interpersonal demands of filmmaking, He suggests ways of responding to producers’ notes or actors’ complaints that allow everyone to keep their dignity. Just stepping away from the Video Village, that cluster of people around the monitor, and positioning yourself by the lens is a way of proactively steering the scene. He even gives good advice about bad reviews. His creative process? “I want to stand behind the camera and make sure there’s something alive going on in front of it, something recognizably human.”

A second batch of chapters shows this aesthetic/ethos in action through case studies from Kwapis’ career. Starting with Follow That Bird (1985), the Big Bird movie, and running up to A Walk in the Woods (2015), these chapters are about concrete problem-solving. How do you direct puppets? Or orangutans? Or Rip Torn? How do you support an actor who’s just not physically up to the role? There’s a fascinating account of staging options in The Office, where different situations force choices between developing the action in the “bull pen” or in the conference room.

The 1990s were rife with narrative experiments, and He Said, She Said (1991) was one of them. Unfolding over two days, its first part uses flashbacks to present Dan’s memory of his romance with Lorie, while the second part shifts to her version, with replays and gap-filling scenes that show the biases of his account. Kwapis and his wife Marisa Silver (Permanent Record) decided to divide responsibilities, with him directing the man’s scenes and her directing the woman’s. They also built in stylistic differences.

We pre-visualized each version to create as much contrast between Lorie’s and Dan’s personaities as possible. For example, I often show Dan’s literal point of view of Lorie, while Marisa uses camera movement and choreography to underscore how Lorie feels about herself (i.e., insecure).

They created specific ground rules for shooting the scenes. Kwapis’ portion came first, so that Silver could see it and fine-tune the replay. Kwapis is admirably specific about how their strategy shaped performance and plot, with minor characters in one half becoming major in the second.

In other words, a cinephiliac idea. (Kwapis prepared for his task by watching Rashomon, The Killing, and Citizen Kane.) The third type of chapter he offers is pure, sharp film criticism, always informed by the demands of craft. His account of American Graffiti is quite different from LaSalle’s, but no less appealing, emphasizing Curt’s visit to Wolfman Jack as an epiphany that needs no formal underlining (“no ham-fisted push-in”).

Other chapters scrutinize 2001, Lawrence of Arabia, The Graduate, I Vitelloni, and other classics. Without being pretentious Kwapis manages to invoke the “objective correlative” (e.g., shoes in Jojo Rabbit) and reflexivity (no big deal). I especially appreciated his detailed analysis of staging in a scene often overlooked in The Magnificent Ambersons: George’s confrontation with a gossipy neighbor, handled in one deftly choreographed close framing.

Kwapis designed the book to explore these three dimensions, but he isn’t puritanical about keeping them apart. Case studies and problem-solving pop up in the general advice sections, and the critical acumen shines through even brief examples of on-set tips (e.g., decisions about a score for Traveling Pants). It all flows together.

The result ranks with Sidney Lumet’s Making Movies and Alexander MacKendrick’s On Film-Making, the most acute personal reflections on Hollywood directing. But like those, it’s more than a testament to the power of craft. It’s also a vision of how, as the first chapter says, to go “beyond success and failure in Hollywood.” You do it, Kwapis maintains, by knowing your plan, respecting your co-workers, inviting discovery through accidents, and staying humane. I like to think that studying films as a critic helped him get there. Not every director, after all, can quote Jean Renoir.

“Only a hack cares about the goddam script”

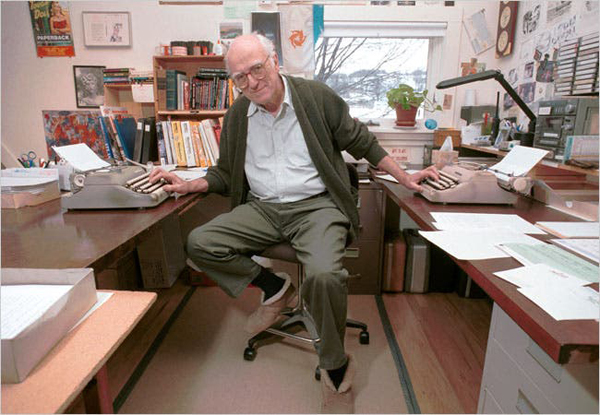

Donald Westlake (David Jennings for the New York Times).

I promised you a murderer, and he arrives in Donald E. Westlake’s Double Feature, a pair of novellas originally published as Enough (1977). The second, Ordo, takes place in Hollywood, when a sailor learns that his first wife has become a movie star and decides to look her up. It’s remarkable in several ways, but the story that grabbed me was A Travesty. On the first page a film critic kills his girlfriend.

True, it’s an accident, but even then he seems less distressed than he should be. He wipes down the crime scene and slips out. Of course he becomes a suspect. Once he seems to be cleared, the trusting cop lets him mosey along on later investigations. They discover that the critic has a knack for solving crimes, including an old-fashioned locked-room puzzle. He gets caught thanks to a plot twist that owes a good deal to Westlake’s early days writing happily overblown softcore porn.

True, it’s an accident, but even then he seems less distressed than he should be. He wipes down the crime scene and slips out. Of course he becomes a suspect. Once he seems to be cleared, the trusting cop lets him mosey along on later investigations. They discover that the critic has a knack for solving crimes, including an old-fashioned locked-room puzzle. He gets caught thanks to a plot twist that owes a good deal to Westlake’s early days writing happily overblown softcore porn.

The plot lives up to its title, being a travesty of whodunits and man-on-the-run thrillers. Westlake invokes mystery conventions like the dying message and the final twist: “As with all Least Likely Suspects, I was in reality the Murderer.” But this guilty protagonist is writing a profound essay on Top Hat and interviewing an over-the-hill director who undermines his belief in the auteur idea that “it’s up to the director to color and shape the material and so on.”

A: Yeah, that’s fine, but you got to have the material to start with. You got to have the story. You got to have the script.

Q: Well. . . . I thought the director was the dominant influence in film.

A: Well, shit, sure the director’s the dominant influence in film. But you still gotta have a script.

Well, that wasn’t any help. What was I supposed to do, go ask three or four screenwriters for suggestions?

A Travesty reveals that Westlake followed East Coast cinephile taste pretty closely. In the passage after this one, the killer regrets placing Brant so high in the Pantheon–a clear reference to Andrew Sarris’s writings. Better to ask a real director like Hawks or Ford or Hitchcock, or even Fuller.

Hip movie references are de rigueur in most mysteries today. (Grudge-reading The Woman in the Window, I thought: Just kill me now.) But how many thrillers in 1977 invoked Marion Davies or Manny Farber’s Negative Space? Our anti-hero argues with a girlfriend about circumstantial evidence in The Wrong Man and Call Northside 777. And as you’d expect, the big clues that reveal the killer to her come from Gaslight.

Westlake has long been one of my heroes; his Richard Stark novels get a chapter in that manuscript I mentioned at the outset. (Go here and here to gauge my dedication.) Like Elmore Leonard, he had a pragmatic approach to movie versions of his work. As far as I know, he complained only of Godard’s handling of The Jugger, which became Made in USA, not that anybody could tell. He wrote screenplays, notably The Stepfather (1987) and The Grifters (1990), and many of his stories have been adapted to the screen (Point Blank, The Outfit).

Nearly all his work I know has a zesty playfulness, and A Travesty is no different. It suggests that, after shooting down movies and destroying reputations, film critics have earned a chance to kill for real. They just turn out to be fairly bad at it.

My stack of reading has barely dwindled. I’ll try to file some more book reports as summer unfolds and the mosquitos discover our shady lawn.

Thanks to Patrick Keating and Mick LaSalle for sending me copies of their books, though I would have bought them anyway. Thanks especially to Patrick Hogan for telling me of his friend Ken Kwapis’s book.

Philip Pullman, a master of the sort of world-building Keating celebrates, argues against dwelling on the story spinoffs harbored by a richly realized milieu. He borrows the scientific idea of “phase space” to suggest that too great a concentration on the indefinitely large possibilities of a story world can freeze a narrative’s progress and distract the reader from the through-line. A story, he says, is a path through a forest and readers are best gripped by sticking to Red Riding Hood’s journey. (Compare Sondheim’s Into the Woods.) Interestingly, he compares this strategy to the cinematic idea of knowing the right spot for the camera, a spot that’s just as valuable for what it excludes as for what it shows. See Daemon Voices: On Stories and Storytelling (Vintage, 2017), 20-24, 122-123.

For more on Parker Tyler, see the chapter in my The Rhapsodes: How 1940s Critics Changed American Film Culture. Avoiding straight reflectionism, Tyler saw the film world as its own sealed-off realm. If the movies reflect anything, it’s not what America thinks but what Hollywood thinks that America thinks. Or rather, what Hollywood imagines that America dreams.

In this entry I write about some of the anti-Japanese films Mick LaSalle discusses.

This entry analyzes the pseudo-documentary style of The Office. I write about 1990s as an era of narrative experimentation in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies.

No admirer of Westlake can ignore the addictive Westlake Review or, of course, the official webpage maintained by his son Paul. Westlake’s motto: “My subject is bewilderment. But I could be wrong.”

American Graffiti (1973).

Oscar’s Siren Song (A Slight Return): Best Original Song

One Night in Miami (2020).

Jeff Smith here:

On Monday, I offered an overview of the five nominees for Best Original Score as well as a prediction regarding the winner. Today, I do the same for the Best Original Song nominees.

The usual caveats apply for those readers interested in the online betting markets. My picks are for “entertainment purposes only.”

As we’ll see, the race in the Best Original Song category is extremely competitive. Indeed, I almost flipped a coin to make my final decision. I didn’t. But the very fact that I thought about it indicates the low level of certainty I have about my prediction.

I should add that there are a few SPOILERS AHEAD. If you don’t want to know some of the key plot twists in Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga or a small but important plot point of The Life Ahead, you can skip to the last section.

Best Original Song: The Underdog

One striking detail about this year’s nominees is the fact that four of the five function as “needle drops” introduced as the film’s closing credits start to roll. Perhaps a steady diet of television episodes streamed during the pandemic has accustomed viewers to expect that this is the way songs now function in movies. Several shows, both old and new, have used these needle drops quite creatively. (I’m thinking here of Mad Men, The Marvelous Mrs. Maysles, and WandaVision. I’m sure you all have your own favorites.)

Set off from the narrative flow of the episode, music supervisors found they could use a song as a curtain closer to highlight elements of theme, tone, or mood without worrying about things like time period or the musical tastes of the show’s characters. Such transmedial influences eventually might establish this as the primary function of popular songs in films. If this year’s nominees are any indication, the trend is already well on its way.

The one exception is “Husavik (My Hometown)” from Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga. The film, of course, is a vehicle for star Will Ferrell. He plays an Icelandic version of his usual man-child persona. It adds, though, a musical competition element borrowed from other comedies, like Pitch Perfect, and from popular music shows, like American Idol.

Ferrell plays Lars Ericksong, a humble “meter maid” whose lifelong dream is to compete in the Eurovision Song Contest. Eurovision, of course, is an annual event in real-life. It remains the longest running internationally televised music competition. The contest played an instrumental role in launching the careers of artists like ABBA, Céline Dion, and Julio Iglesias.

Lars hopes to follow in their footsteps, but his ambitions are mocked by the other residents in his small town.

Lars’ only defender is Sigrit, his childhood friend and his partner in the musical duo Fire Saga. Fire Saga plays a vital role in the town’s musical culture, performing regularly at a local bar. Yet their audience mostly rejects their musical offerings. Instead, they prefer “Ja Ja Ding Dong,” a sexually suggestive nonsense song that is the antithesis of past Eurovision winners.

Sigrit, played winningly by Rachel McAdams, is steeped in Icelandic folklore. She makes offerings to a small den of elves that she hopes will prompt Lars to return her considerable affections for him. She also believes in the “speorg note,” a mystic tone that Sigrit’s mother tells her represents the truest expression of the self.

Fire Saga enters the national competition hoping to earn the honor of representing Iceland. During an Icelandic Public Television meeting, their song is picked at random simply to meet Eurovision’s requirements for a country’s eligibility. At Reykjavik, Lars and Sigrit nervously wait backstage for their performance. Sigrit wishes that she could sing in their native language since it would calm her down. Lars, though, warns against it noting that a song in Icelandic would never win Eurovision.

Fire Saga loses to a talented competitor named Katiana, played by Demi Lovato in a nice cameo. Embittered, Lars refuses to attend a party celebrating the winner and Sigrit joins him in solidarity. When the boat hosting the party explodes, killing everyone aboard, Fire Saga becomes the Icelandic entry as the only surviving runner-up.

Once in Edinburgh, the site of the 2020 competition, Lars and Sigrit clash regarding the best way to present their music. (In reality, the 2020 Eurovision contest was to be held in Rotterdam but was cancelled due to the pandemic.) Lars wants to wow the audience with elaborate costumes and stagecraft. He also hires a K-Pop producer to remix their recording, giving it a hip new arrangement. Sigrit would rather just let the music speak for itself.

During the semi-finals, Fire Saga’s performance of “Double Trouble” seems to be going well. But Lars’ desire for showmanship backfires when the absurdly long scarf he has given Sigrit gets caught in the gears of his giant hamster wheel.

Sigrit is able to free herself before she suffers the fate of Isadora Duncan. But the hamster wheel breaks free and crashes into the audience. Although Lars and Sigrit recover just in time to finish the song, they are initially met with stunned silence. This is followed by some snickers scattered amongst the crowd. Lars and Sigrit leave the stage dejected, smarting from their humiliation.

Crestfallen, Lars returns to Húsavik, reconciled to life as a fisherman rather than a musician. Sigrit stays behind to continue her dalliance with Alexander Lemtov, a rival contestant from Russia. Sigrit is gobsmacked when she learns that Fire Saga has been voted through to the finals, a plot twist perhaps inspired by the real-life hate-watching that produced surprisingly long runs by American Idol contestants like Sanjaya Malakar.

Lars makes a mad dash back to Edinburgh, both to participate in the finals and to declare his love for Sigrit. Looking like the Gorton Fish guy, Lars sneaks onstage just as Sigrit has begun “Double Trouble.” He stops her mid-phrase and persuades her to sing a new song even though he knows the change will result in Fire Saga’s disqualification. Sigrit begins tentatively but soon grows in confidence as she reaches the chorus, sung in Icelandic much to the delight of those watching in Húsavik. The song builds to its climactic final note, a high C# that is held for several seconds, leaving both the audience and Lars rapt in awe. This time Fire Saga’s performance is met with thunderous applause. In an aside just for the viewer, Lars exclaims, “The speorg note!”

There’s a lot wrong with Eurovision. Some of the film’s gags misfire badly. The race to get Lars from the airport to the auditorium features the kind of crazy stunt work that’s grown stale from overuse. (Think spinning car and reaction shots of screaming passengers!) And at 126 minutes, Eurovision has two or even three subplots too many.

Yet the filmmakers definitely stick the landing with Fire Saga’s triumphant performance of “Husavik (My Hometown).” Seeing Lars cede the spotlight to Sigrit and her rise to the moment brings a lump to the throat, just as it does in other show-biz success stories like 42nd Street (1932) and A Star is Born (2017). (It’s an old formula but a potent one.)

Moreover, the sequence pays off several dangling causes (the reference to Icelandic lyrics in the scene backstage, the rekindled romance of Lars’ father and Sigrit’s mother, the speorg note). Even Fire Saga’s disqualification strikes the right tone by making the duo the musical equivalent of Rocky. They win by losing, content in the knowledge they were worthy contenders and in the realization of what they truly value. Watching the folks back in Húsavik swell with community and nationalist pride is just the cherry on top of a very satisfying sundae.

Any one of Eurovision’s Europop pastiches would have been worthy of nomination. For example, the faintly ridiculous quality of Lemtov’s “Lion of Love” makes it a perfect surrogate for the character’s ostentation and vanity. But only “Husavik (My Hometown)” both tickles the fancy and tugs the heartstrings.

Still, despite its appositeness for Eurovision’s story, I think it is a long shot when it comes to claiming the trophy. You have to go back to The Muppets in 2011 to find an Oscar-winning song in a live action comedy. And that was a strange year in which there were only two nominees. Before that, you have to reach all the way back to 1984’s The Woman in Red. That year, the winner was “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” written and performed by the great Stevie Wonder. Despite its considerable craft, “Husavik (My Hometown)” seems unlikely to alter a trend that rewards songs in dramas rather than comedies.

The Bridesmaid (as in “Always the…”)

This past February, Diane Warren received her twelfth Academy Award nomination for “Io Sì (Seen),” featured in the Italian film, La Vita davanti a sé. Warren has won an Emmy, a Grammy, and two Golden Globe awards, but has yet to claim an Oscar. This puts Warren in some pretty good company. Her colleague, composer Thomas Newman, has been nominated fifteen times without winning. Composer Victor Young received 21 nominations before finally breaking through with Around the World in 80 Days (1956). Sadly, Victor Young didn’t live long enough to actually receive the award. He died at age 57 just months before the ceremony.

Warren’s latest effort, “Io Sì (Seen),” is the type of soaring power ballad she has spent much of her professional life perfecting. The song starts with a modest piano figure that accompanies Laura Pausini’s indomitable voice at a moderate tempo. The lyrics offer a simple but powerful declaration of emotional support regarding the need to be “seen.” Pausini’s voice rises in the chorus as she vows in Italian, “But if you want, if you want me, I’m here.” The addition of a string orchestra and tasteful percussion accents provides additional emotional heft.

The modest arrangement allows the song’s simple beauty to shine through. Its mood and Pausini’s vocal delivery seem miles away from the bombast that made Aerosmith’s “I Don’t Want to Miss a Thing,” one of Warren’s earlier nominees, a chart-topping single.

For me, though, that is all to the good. La Vita davanti a sé is itself an unassuming coming-of-age tale that depicts the unlikely friendship that develops between Madam Rosa, an elderly Holocaust survivor, and Momo, a 12-year-old orphan from Senegal.

Buoyed by Sophia Loren’s valedictory performance, the song reflects the strong filial bonds that form when Momo becomes Rosa’s ward. The lyrics’ reassurance that “I’m here” capture the ways in which Momo and Rosa have learned to care for one another. Placed just after the funeral ceremony that closes the film, “Io Sì (Seen)” sustains the scene’s bittersweet, melancholy tone and carries it into the credits. The song also reiterates the story’s central themes regarding the need for unconditional acceptance and love’s ability to overcome differences in gender, race, and age.

La Vita davanti a sé has become an unlikely hit for Netflix. At the peak of its popularity, it reached the streaming service giant’s top ten in 37 different countries. Perhaps that sleeper success will bolster Warren’s chances among Academy voters. She is eminently deserving of the award as a sort of career honor.

Could this be Warren’s year? Perhaps. Still, the fact that more famous songs by Warren, like “Because You Loved Me” and “How Do I Live,” also suffered defeat raises some doubts.

Panthers and Boxers and Yippies (Oh My!)

The three remaining nominees are all songs featured in films that look back at the legacy of sixties political activism. Unlike Eurovision Song Contest and La Vita davanti a sé, Judas and the Black Messiah, One Night in Miami, and The Trial of the Chicago 7 all received multiple nominations. Often the halo effect created by that reflected glow can make a difference in very competitive races. Moreover, the two titles receiving Best Picture nominations – Judas and Chicago – also benefit from the massive “For Your Consideration” ad campaigns that appear in trade publications like Variety. All of this suggests that, if you are looking for this year’s winner, you might look here.

Let’s start with “Fight for You,” the groovin’ track by H.E.R. that closes Shaka King’s Judas and the Black Messiah. The song self-consciously evokes music from the period depicted in the film. As H.E.R. told Variety, she wanted the music to have a hopeful vibe, but lyrics that connected to the Black Panthers’ historic fight against injustice. She drew upon the classic soul music of Marvin Gaye, Nina Simone, and Sly and the Family Stone, artists who made records that were both popular and politically astute.

The final product is a remarkable synthesis of these different elements. The syncopated brass and organ chords recall vintage Sly and the Family Stone tunes like “Stand.” The spare but funky bass line and the supple guitar melody wouldn’t be out of place on Gaye’s classic, “Let’s Get it On” while the doubling of H.E.R.’s voice, sometimes in octaves and sometimes in thirds, conjures up his masterful What’s Going On album. The string arrangements and choral melody also bring to mind Curtis Mayfield’s classic score for Superfly (1972) for good measure. Only one of the five nominees will make you want to get up dance, and this is it. With its Funk Brothers arrangement and uplifting social message, “Fight for You” educes a bit of folk wisdom from P-Funk guru George Clinton: “free your mind… and your ass will follow.”

Celeste and Daniel Pemberton’s “Hear My Voice” from The Trial of the Chicago 7 also evokes sixties soul, albeit with more of pop flavor and even a dash of Northern soul. Celeste grew up around Brighton on England’s southern coast. Her interest in music was nurtured by her early exposure to American jazz vocalists like Ella Fitzgerald and Billie Holiday. Those influences can be heard in Celeste’s elegant phrasing on “Hear My Voice.” (Beware ads.) But her vocal style has also drawn comparisons to more contemporary British soul singers like Amy Winehouse and Adele.

The end result doesn’t slavishly duplicate any of those other singers, emerging as something else entirely. In fact, although Celeste’s voice has a timbre all her own, to my ears, the slightly retro vibe of “Hear My Voice” evokes sixties pop and blue-eyed soul artists like Dionne Warwick and Dusty Springfield. The song itself is a mid-tempo ballad with a loping, syncopated beat and an arching upward melody furnishing the tune’s main hook. Pemberton’s arrangement heightens the pop elements in the recording by emphasizing the piano and strings climbing steadily upward.

The Trial of the Chicago 7’s title is fairly self-explanatory, dramatizing the prosecution of activists from the Black Panthers, the Yippies, and Students for a Democratic Society after protesters violently clashed with police at the 1968 Democratic Convention. David’s blog on Aaron Sorkin shows, among other things, how the screenwriter/director drew upon the “drama of ideas,” a tradition associated with “turn of the century” playwrights like Henrik Ibsen and George Bernard Shaw. In a slight break from that tradition, though, Sorkin sought to end the film on a note of optimism and hope that would yield a sense of empowerment.

According to Pemberton, the director’s first choice for an end-title song to reflect that tone was the Beatles’ classic from Abbey Road, “Here Comes the Sun.” The composer, though, gently persuaded Sorkin to try something fresh, a new song unburdened by the enormity of the Beatles’ legacy. He also reminded Sorkin of the huge licensing fees that any Beatles song would inevitably command. Pemberton and Celeste’s much-deserved Oscar nomination vindicates the composer’s instincts. Had Sorkin used “Here Comes the Sun,” viewers would have soaked in its upbeat vibe. But The Trial of the Chicago 7 would have gotten only five nominations rather than the six it ultimately received.

Last, but certainly not least, we have Leslie Odom Jr. and Sam Ashworth’s “Speak Now,” featured in Regina King’s directorial debut, One Night in Miami. The film offers a fictionalized account of a fabled meeting of four icons of the 1960s: Malcolm X, Jim Brown, Muhammad Ali, and Sam Cooke.

The group assembles in a room at the Hampton Hotel to celebrate Ali’s victory over then heavyweight champion Sonny Liston. Yet, with only some vanilla ice cream and a flask of booze as party favors, the good-natured banter soon devolves into a debate about the best ways to achieve social change on the path toward racial equality.

Both musically and lyrically, “Speak Now” seems keyed to an important scene in the film where Malcolm chides Cooke for recording trifling love songs rather than music that speaks to the ongoing struggle for civil rights. He pulls out a copy of The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan and plays “Blowin’ in the Wind.” Malcolm then asks Sam why it is that a white boy from Minnesota makes music that seems so perfectly attuned to the historical moment. Isn’t “Blowin’ in the Wind” the type of song Cooke should write? Malcolm’s criticism becomes a dangling cause that is picked up in the film’s epilogue. As a guest on The Tonight Show, Sam performs “A Change is Gonna Come” for the first time, showing how he embraced Malcolm’s challenge to him.

Beginning with a syncopated acoustic guitar riff, “Speak Now” not only recalls several moments of the film where Cooke pulls out his own guitar, but also evokes the type of folk music that was Dylan’s stock in trade during the early sixties. The guitar is soon joined by a swirling Hammond B-3 organ. The instrument’s timbre evokes both the gospel music that inspired Cooke throughout his career and Al Kooper’s distinctive organ stylings on two Dylan masterpieces recorded after he went electric: Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde on Blonde. Floating above both is Odom’s plaintive voice, urging the film’s viewer to “Listen, listen, listen.” Providing the link between past and present, the lyrics entreat the audience hear to the “echoes of martyrs” and the “whispers of ghosts.” Odom’s soaring falsetto suggests both vulnerability and hope. The song gradually builds, adding strings and percussion, until it reaches a rousing climax.

With its simple arrangement and its mixture of styles, “Speak Now” sounds like the musical child that Bob Dylan and Sam Cooke never had the opportunity to conceive. It provides a fitting end to One Night in Miami by reminding us that the struggle for civil rights continues, especially at a historic juncture where America is challenged to confront the structural and institutional foundations of white privilege and white supremacy.

Prediction

On Oscar night, I will be watching with bated breath to see if…..

…singer Molly Sandén hits the “speorg note” during the performance of “Husavik.” If she does, it will bring down the house (or at least break a few champagne glasses).

But the winner? Your guess is as good as mine. This is among this year’s most competitive races. In Variety, Jon Burlingame notes that Diane Warren’s past nominations made her the early favorite, but adds, “You can’t count out anyone, however, in this year’s level playing field.”

If the vote reflects the song that is most clearly integrated into the film’s story, it’s “Husavik.” It is also rumored to be making a late charge, aided by late campaigns by Netflix and the tiny town of the title.

If, on the other hand, the vote reflects the song that I’d want next in my iTunes queue, it’s “Fight For You.” It’s got a funky groove that just keeps on keepin’ on.

That being said, I don’t think either of those two songs will carry the day. Ever since the nominations were announced, it’s generally felt like a two-horse race: Diane Warren vs. Leslie Odom Jr. The voting could split between those who desire to finally recognize Warren after so many nominations and those who find Odom deserving of the award for Best Supporting Actor but who still voted for Daniel Kaluuya instead.

The fact that Odom is a double nominee would seem to help his chances. But his song’s social significance also gives it a slight edge. In 2015, Common and John Legend took home the prize for “Glory,” their inspirational song from Selma. Like “Speak Now,” the lyrics of “Glory” captured the zeitgeist surrounding the Black Lives Matter movement, particularly the protests in Ferguson, Missouri. The message of “Speak Now” is just as relevant and just as timely. It is possible that voters will want to acknowledge it for that very reason.

Still my gut tells me this is Diane Warren’s year. Thirty-three years ago, Warren sat in the venerable Shrine Auditorium as a first-time nominee. She came in with a fighter’s chance. Her song, Starship’s “Nothing’s Gonna Stop Us Now,” had a fighter’s chance having hit the top of the charts in five different countries, eventually earning gold or platinum record status in four of them. But it was aced out by an even more popular song, “(I’ve Had) The Time of My Life” from Dirty Dancing. It had gone to #1 in six countries and earned gold or platinum status in seven different markets.

Warren’s been waiting ever since for a chance to pop the cork in a champagne bottle at an Oscars afterparty. I think the bubbly finally flows for her this Sunday.

Once again, a shoutout to Jon Burlingame for his coverage in Variety of the Academy Awards’ music categories. His analysis of the Best Original Song nominees can be found here, here, and here.

To find short interviews with all of the songwriting teams, check out these items from The Hollywood Reporter and Billboard.

A podcast with H.E.R. discussing her collaboration with Tiara Thomas and D’Mile on “Fight For You” can be heard here.

A very long interview with Daniel Pemberton describing his work on The Trial of the Chicago 7 can be found here.

Leslie Odom Jr. talks about writing “Speak Now” here and here.

Finally, Diane Warren performs a medley of all twelve of her Oscar-nominated songs here.

Eurovision Song Contest: The Story of Fire Saga (2020).

Oscar’s Siren Song (A Slight Return): Original Score

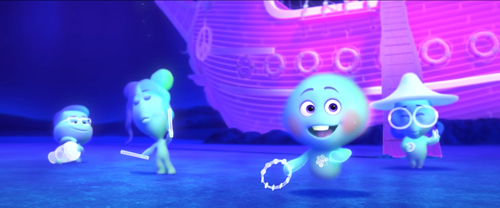

Soul (2020).

Jeff Smith here:

After a short hiatus, I’m back with a preview of this year’s Oscar nominees for Best Achievement in Music Written for Motion Pictures. As with everything else in the COVID pandemic, this year’s nominees represent a slight departure from previous years. With the massive shuffling of release schedules, some films like No Time to Die, Dune, and In the Heights that would have been strong contenders in these categories will have to wait until next year. At the same time, the closure of theaters, and the attendant changes regarding Oscar eligibility, meant that some smaller films’ fortunes were boosted by their availability on top streaming services like Netflix and Amazon Prime.

Here I survey the five scores that received nominations and offer a prediction regarding the eventual winner. Later this week, I’ll do the same for the Best Original Song nominees.

The usual caveats apply for those readers interested in the online betting markets. My picks are for “entertainment purposes only.”

Moreover, I admit that my track record hasn’t exactly been stellar. If memory serves, I’ve gone five for eight in my previous predictions. That’s about a 62% accuracy rate. Better than chance but hardly anything to brag about.

Consequently, I advise readers to treat both predictions as the equivalent of a handicapper’s pick for a daily double. It feels really good if you are right. But truth be told, odds are against it.

Let’s turn now to the nominees for Best Original Score. At first blush, it would be hard to imagine a more disparate group of nominated films. It includes a Western, an adventure film, a family drama, a retro-styled biopic, and a metaphysical comedy in cartoon form.

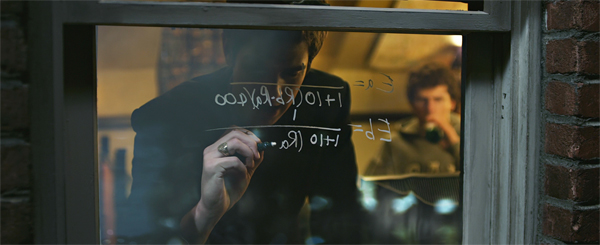

Composers Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross are heavy favorites going into Sunday as double nominees. They were recognized both for their jazz-flavored orchestral score for Mank and, along with fellow nominee Jon Batiste, for their electronic atmospherics in Soul. As previous winners for The Social Network (2010), they stand a good chance of adding more little gold men to their mantles.

The long shot

The Oscar betting markets have Terence Blanchard’s score Da 5 Bloods as the nominee with the longest odds. That is a shame insofar as Blanchard remains one of the most underrated composers writing for films. Using a 90-piece orchestra, Blanchard provides an epic sound for Spike Lee’s clever take on The Treasure of the Sierra Madre. I wouldn’t say Blanchard and Lee’s collaboration on Da 5 Bloods is a career best. For me, their peak is represented by the magisterial score in 25th Hour (2003), one of the best films of the 2000s. Still, Blanchard’s music for Da 5 Bloods is awfully, awfully good.

Besides the resources of a conventional orchestra, Blanchard also engaged the services of Pedro Eustache to play the duduk, an Armenian double reed instrument that adds an unusual tone color to some of the score’s melodies. The duduk adds a touch of exoticism as a reminder that the protagonist Paul and his crew of Vietnam vets are strangers in a strange land. Yet the score wisely avoids the kinds of Orientalizing musical gestures that are common in many Hollywood films with South Asian settings. The duduk is heard in a handful of cues that underscore Otis’ relationship with Tien, his old Vietnamese girlfriend.

In contrast, strings and brass are key to several cues pitched in an elegiac register. As Todd Decker notes in his book, Hymns for the Fallen: Combat Movie Music and Sound after Vietnam, this style of music became especially common in Hollywood war films after Samuel Barber’s famous Adagio for Strings was used so memorably in Oliver Stone’s Platoon (1986). A good example is “MLK Assassinated” where the squad reacts to Hanoi Hannah’s announcement of the civil rights leader’s death.

Blanchard, too, mines this vein in cues accompanying scenes where the crew recalls the death of their squad commander Stormin’ Norman Earl Holloway.

Da 5 Bloods is a film of greed and grief, rage and remorse. Blanchard’s score not only captures the frustrations occasioned by America’s racial reckoning, but also reveals the deep sadness beneath, paying tribute to the sacrifices Black soldiers made while serving in Vietnam.

The Newbie

Our second nominee is Minari, which features the music of composer Emile Mosseri. Mosseri studied film scoring at the prestigious Berklee College of Music in Boston. But he also is a member of an indie rock band, The Dig, which has released three albums and four EPs since their debut in 2010. Mosseri got his first major film assignment in 2019 when he wrote the score for Joe Talbot’s acclaimed debut, The Last Black Man in San Francisco. Mosseri soon established himself as an up-and-comer in the world of American Indie cinema. In 2020, Mosseri not only wrote the music for Minari, but also scored Miranda July’s Kajillionaire.

Minari tells the autobiographical story of a Korean-American family’s move to Arkansas in the 1980s. When Mosseri offered to help with the film’s music, director Lee Isaac Chung gave the composer only one directive. He told him not to do something Korean. Instead, Chung and Mosseri discussed the work of Maurice Ravel and Erik Satie, seeing their impressionistic, delicate tone as an idiom more fitting for the story. Mosseri took the unusual step of writing some sketches before production began. This assured that the tone of the score was “baked in” to the film throughout post-production. It also allowed Chung and his film editor to adjust the duration of shots and select takes to better fit Mosseri’s already existing music.

Given Ravel’s and Satie’s influence on the score, it is not surprising that Mosseri’s melodies and orchestrations emphasize piano and strings. Mosseri, though, varies the tonal palette by occasionally adding voices, winds, and vintage LFO synthesizers, instruments whose timbre helps to suggest the feeling of a “dream-memory” soundscape. Many of the cues unfold as patterns of slowly shifting harmonies. This is evident in “Outro” which can be heard below.

Mosseri notes that the real challenge in the film was to communicate Minari’s warm and gentle tone without being saccharine. The score’s modesty makes it appear to be the polar opposite of Blanchard’s epic style in Da 5 Bloods. Whereas Blanchard goes for emotional sweep and impassioned sorrow, Mosseri strives for reserve and subtlety. Moreover, although Blanchard writes for a 90-piece orchestra, Mosseri’s ensemble is less than half that size. Lastly, whereas Da 5 Bloods contains a lot of music — not just Blanchard’s score, but also another ten period-appropriate songs — Minari has a little over thirty minutes of underscore, heard for less than a third of the film’s 115-minute running time.

Still, Minari and Da 5 Bloods have one thing in common. A film composer’s first job is to serve the story, tailoring their music to the specific needs of each scene. Blanchard and Mosseri have done that as well as anyone this past year. I would be happy to hear either one of their names called out as the winner come Sunday night.

The Oater

The third film nominated for Best Original Score is the Paul Greengrass Western, News of the World. Unlike Mosseri, who is a first-time nominee, this is composer James Newton Howard’s ninth nomination. During a career in Hollywood that spans more than 35 years, Howard has enjoyed close collaborations with directors like M. Night Shyamalan and Francis Lawrence. His music has also been a vital component of popular franchises like The Hunger Games and the Harry Potter spinoff, Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them.

On a personal note, Howard played a key role in my own musical biography. Earlier in his career, Howard did string arrangements and played keyboards on Elton John’s Blue Moves (1976), an album that was among the first dozen or so I bought as a teenager. I also listened repeatedly to its biggest hit, “Sorry Seems to Be the Hardest Word,” trying to slavishly duplicate both Elton’s piano part and Howard’s nifty keyboard solo. Elton won last year for Rocketman in the category of Best Original Song. It somehow seems fitting that Howard could take home an Oscar this year for Best Original Score.

News of the World tells the story of Captain Jefferson Kyle Kidd, a Civil War veteran who travels across Texas, reading news stories aloud in frontier towns for both entertainment and edification. Early on, Kidd comes across an overturned wagon and discovers a lost child. Abducted by the Kiowa, Johanna was being escorted back to her family by a federal officer when their party was bushwhacked. Kidd learns that Johanna will have to wait several months for the return of the Bureau of Indian Affairs representative. So the Captain decides to deliver Johanna to her surviving family. The rest of the film dramatizes their growing bond as Kidd and Johanna make the 400-mile trek through hostile territory to her aunt and uncle’s homestead.

Adapted from Paulette Jiles’ 2016 novel, News of the World feels a bit like a mashup of The Searchers (1956) and the Coen Brothers’ remake of True Grit (2010). Its kidnapped-child premise seems inspired by the former while the picaresque journey structure and “father-daughter” emotional dynamic derive from the latter.

Several of the film’s plot elements, though, offer comment on contemporary politics. The brusque handling of Johanna by Union Army officials in Texas can’t help but remind us of the Trump administration’s family separation policies. Similarly, when Kidd and Johanna are stopped by brigands from a radical militia, they are taken to a town governed under White Supremacist principles, an episode that serves as a grim reminder of contemporary threats of domestic terrorism.

Like Mosseri’s score for Minari, much of Howard’s music in News of the World strives to capture the intimacy and deepening trust that develops between the central characters. That relationship is reflected in one of Howard’s main musical themes heard here in a cue entitled “Kidd Visits Maria.”

Howard’s cues often feature long languid melodies in the strings, but he also nominally adheres to genre convention by incorporating harmonica, mandolin, banjo, guitar, and scratchy fiddle airs to flavor the score with a folksy, period sound. For a handful of scenes involving shootouts, hazardous travel, and hair’s breadth escapes, Howard furnishes the rhythmic drive and dynamics that give them their emotional punch. But the score is most effective in its quiet and reflective moments. Kidd and Johanna both suffer from a sense of loss and loneliness. As they gradually come to realize how much they need each other, Howard’s music communicates that well of feeling, expressing what the characters themselves are too reticent to admit.

Souls and the Soulless

This brings us to the final two nominees: Mank and Soul. For Mank, Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross sought to create a score that would seem experimental if it were featured in a film made in 1940. To some extent, they succeed. By opting for an orchestral jazz sound, they evoke a style that did not become common until the 1950s when it was popularized by later Hollywood composers like Alex North, Elmer Bernstein, and Henry Mancini. Still, despite that disjuncture, Reznor and Ross’ score still seems period appropriate insofar as it recalls much of the popular music recorded during the 1930s.

In preparing Mank’s score, Reznor and Ross decided to write cues in two different, but related styles. One set of cues involved big-band and foxtrot arrangements that would underscore scenes involving studio politics. An example is the cue “Fool’s Paradise” heard below.

The other set of cues deployed an orchestral palette and speak more to Mank’s emotional journey over the course of the film.

Notably, Reznor also admits that they often referred back to Citizen Kane during the writing process. Not surprisingly, some cues, like “Welcome to Victorville” and “Absolution,” sound a bit “Herrmannesque” in their evocation of Kane’s famous score.

A few, such as “San Simeon Waltz,” are even in the lyric mode Bernard Herrmann used in scores like The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) and The Ghost and Mrs. Muir (1947). The latter, not coincidentally, was directed by Herman Mankiewicz’s younger brother, Joseph.

For the most part, Mank’s music hits all the right notes, as bracing as a warm breeze on a summer day. The score is aptly sweet and tender for the heart-to-heart talks between Mank and Marion Davies, arch and mischievous for moments that display Mank’s acrid wit. In fact, Mank’s score seems most period-appropriate on the rare occasions when it indulges a bit of “Mickey-mousing.” An example of this occurs in the scene where Mank drunkenly stumbles as he exits a car in front of Glendale Station. As Ross notes, the music “gets drunk” as well with muted horn figures that could easily have been pulled from an MGM or Warner Bros. cartoon. All that’s missing is the sound of Mank’s hiccup.

And then there’s Soul. Reznor and Ross’ collaboration with New Orleans musician Jon Batiste is a favorite with good reason. The film’s protagonist is a jazz pianist, an element of the story that makes music integral to the viewer’s experience. Such narrative motivation has certainly helped several previous winners, like La La Land, The Red Violin, and Round Midnight. It also helps that Soul has swept almost all of the year-end critics’ awards for Best Score as well as winning a Golden Globe, a BAFTA, and a Society for Composers and Lyricists Award.

Like the score for Mank, most of the music for Soul consists of two types. On the one hand, there is the earthbound jazz performed by Joe Gardner, the film’s protagonist. These cues provide Jon Batiste an opportunity to shine. Anyone who knows Batiste from his regular gig with Stay Human, the house band on Late Night with Stephen Colbert, are well aware of his enormous talent. For me, even more amazing is Pixar’s skill in animating Joe’s pianistic skills which mimic Batiste’s virtuoso scale runs and arpeggios.

On the other hand, though, we have the music Reznor and Ross wrote for the film’s depiction of the “Great Before,” the way station where counselors prepare unborn souls for their journey to Earth.

And for the zone, a place where souls can experience euphoria upon realizing their life’s passions.

Some reviewers have characterized these cues as spacey New Age music, and that description has a grain of truth to it. Yet, the sounds created by Reznor and Ross seem more like an extension of the electronic experiments they explored in their cutting-edge work on The Social Network, Gone Girl (2014), and Waves (2018).

According to Reznor, to convey the sense of the afterlife as a world both strange and comforting, he and Ross brought in some ideas about microphone placement, vocal textures, and scraping noises they had tried out in their studio. They also processed the sounds from samples and recordings of instruments to give them a slightly off-kilter quality. Such techniques were intended to underline the “imperfections of humanity” in an interesting way. The end product is a “very sublime synthetic score,” in the words of sound designer Ren Klyce. To it, Klyce added the sounds of waving wheat fields and children’s voices to create an environment that felt safe, peaceful, relaxing, and nurturing.

The tranquil score is a perfect fit for director Pete Docter’s vision of the “Great Before.” Yet it also feels a bit uncanny coming from Reznor, a pioneer of industrial music, a style of rock music as cacophonous, abrasive, and propulsive as its name implies. Reznor’s primal howl as the frontman for Nine Inch Nails remains a cultural touchstone of premillennial, post-adolescent angst. Reznor’s contributions to Soul not only show he has mellowed with age, but also that the guy has got extraordinary range.

Prediction

This is the easy one. Barring some groundswell of support that would produce a Minari sweep, Soul will take home the Oscar for Best Original Score. All of its previous awards are very strong indicators. It’s hard to see how the Academy will be any different from any of the 35 other organizations that have recognized Soul’s score as the best of the past year.

As always, my go to source for information about the Academy Awards’ music categories is Jon Burlingame, Variety’s film music specialist. Burlingame’s coverage of these races is always informative and insightful. Some examples of his reportage can be found here, here, and here.

The Hollywood Reporter also has published some useful articles about this year’s nominees, which can be found here.

Besides the interviews mentioned above, one can find many other interviews through the web. An interview with James Newton Howard about his work on News of the World can be found here.

Discussions with Emile Mosseri about the collaboration with Lee Isaac Chung can be found here, here, and here.

Terence Blanchard talks about the music for Da 5 Bloods and his long partnership with Spike Lee here, here, and here.

Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross discuss their approach to Mank here.

The duo are featured in a long video discussing and demonstrating their creative process here.

Lastly, a link to Todd Decker’s Hymns for the Fallen can be found here.

Soul.

THE TRIAL OF THE CHICAGO 7: Aaron Sorkin samples the menu

The Trial of the Chicago 7 (2020).

DB here:

Love him or hate him, you have to admit that Aaron Sorkin has carved out a unique position in contemporary Hollywood. If we want to understand craft practice from the position of media poetics—that is, the principles governing form, style, and theme in particular historical circumstances—we can usefully look at him as a powerful example.

He’s more than merely typical, of course. In an era when the f-word exchanges of Palm Springs pass muster as comic dialogue, it’s refreshing to watch a movie where smart characters, sparring for high stakes, make a retort that’s more stinging than a slap in the face. These movies are written through and through, and in distinctive ways.

More broadly, Sorkin’s distinctive career invites us to consider the nature of innovation and originality in the popular arts. Because of “progressive” accounts of art history, we’re inclined to emphasize the shock of the (utterly) new as the mainspring of change and the central source of quality. The history of modern painting is written as a series of breakthroughs after Post-Impressionism, from Cézanne through Picasso and Mondrian and so on—the leap to abandon the past, the “next logical step” in an advance toward…what? Abstract Expressionism? Then what? Similarly, from Wagner to Strauss to Schoebberg to Berg to Webern and then…? Boulez? And…?

If the history of an art is a surging procession of avant-gardes, what then do we do with the artists who don’t fit? There are eccentrics, such as Balthus or Satie, who turn out to “point forward” at angles and detours that the linear-progress story doesn’t allow. What about those artists who refine or revise tradition in fresh ways? Where do we put Deineka, recently noticed as no mere Socialist Realist hack, or Shostakovich and Sibelius? Or, in the orthodox history of the detective story (whodunits surpassed by hardboiled), Rex Stout?

In the popular arts particularly, we should expect to find historical patterns less like the Breakthrough Canon, a high-altitude survey of outsize rock formations, than something closer to the ground. Studying mass entertainments like film and popular fiction, we’re likely to find valleys revealing unexpected views of familiar landscapes. There are daisies in the crevices.

In contrast to the Breakthrough account, non-western art traditions valorize accumulation of options and preservation of precedent. An artist earns acclaim for finding fresh ways to realize long-standing craft principles. The Japanese renga poet, the Chinese painter or calligrapher, and the Ottoman carpet weaver revise inherited techniques to reveal new expressive possibilities. Actually, in the West we have the same situation. Come down from the bird’s-eye view, and we’ll see the same fine-grain fluctuations. E. H. Gombrich pointed out how painters, the masters and the minor players, develop their pictures on the basis of inherited patterns—schemas that they have learned and that provide a point of departure for original treatment.

In several places I’ve proposed that filmmakers work with schemas too—pictorial ones, but also narrative ones. The shot/reverse shot technique is a schema, but so is the framed flashback, the four-part plot, and the strategy of beginning your action at a point of crisis.

You see where I’m going with this. Sorkin is worth studying, I think, as a very skilled craftsman. Surveying just a few of his films showed me that he finds ingenious and sometimes powerful ways to rework the schemas from the tradition of American filmmaking—and, of course, from the theatre.

Ventilating the play

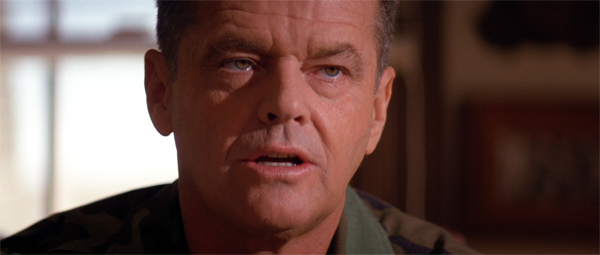

A Few Good Men (1992).

If you want to reach a broad audience in today’s American cinema, you need to either make films with large doses of physical action (as crossover indie directors have found) or to find a signature identity that cultivates a following. In Sorkin’s case, he has dared to rely on plot, dialogue, and a distinct worldview that he has managed to make entertaining. Sorkin’s first plays, followed by the huge stage success of A Few Good Men (1989), typed him as a “theatrical” talent. But over thirty years his film projects sought to “cinematize” what’s usually considered stage technique.

The obvious example is his reliance on “walk and talk,” the long backward tracking shot covering characters striding toward us and spitting out dialogue rapidly. This develops the verbal drama while also yielding some attention-grabbing visuals. But there are less apparent ways Sorkin has blended theatrical technique and cinematic narration.

Early twentieth-century playwrights tended to put the “point of attack”–the moment in the story when you start the play’s plot–fairly close to the climax. Associated with Ibsen and other pioneers of “new theatre,” the late point of attack was a solid convention by the 1910s. As in A Doll’s House and Ghosts, the action starts at a point of crisis, and offstage events leading up to it get revealed through dialogue, sometimes called “continuous exposition.”

The trial schema is a good example of the crisis structure. Typically a trial starts after a lot of stuff has already happened, so the continuous exposition is supplied through testimony and speeches by the defense and prosecution. By 1915, Elmer Rice’s play On Trial was inserting flashbacks that reenacted trial testimony, but some plays stick only to what happens in the courtroom. The Off-Broadway production of A Few Good Men used that linear, present-tense premise, in the vein of earlier plays like The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial (1954) and Inherit the Wind (1955). The investigation of the death of a young Marine is pursued by a prosecution team running up against the military code and a couple of hard-headed officers.

But in preparing the film version, Sorkin adapted to the menu of storytelling options on offer in 1990s moviemaking. For instance, the opening scene could be a grabber, a strong moment that aroused curiosity or suspense. (This might have been a reaction to the need to grab the viewer who’d later see the movie on cable or video.) So instead of letting everything be recounted in the trial, Sorkin’s screenplay for A Few Good Men chose an earlier moment in the story action–a literal “point of attack” showing Dawson and Downey assaulting Santiago.

Later, Sorkin ventilates the play in a traditional manner, supplying scenes that present the prosecutors taking the case and investigating the circumstances. The courtroom scenes don’t begin until about an hour into the film, and they alternate with strategy sessions among the legal team and the defendants. The result is a “moving spotlight” narration, mostly attached to Kaffee the lead prosecutor and Lieutenant Commander Joanne Galloway, but ready to shift to other characters.

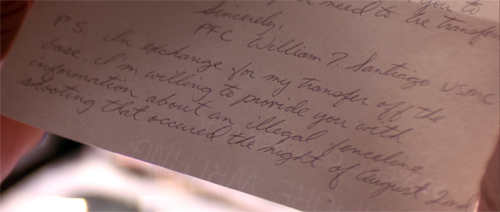

The timeline is chronological, except for a brief flashback dramatizing a letter initially voiced by Santiago. He appeals to Colonel Jessep to transfer him out of the unit for medical reasons. In exchange he offers to give information about an illicit fence-line shooting.

The flashback modulates to Jessep reading the letter aloud (an audio hook) and considering how to handle the situation.