Archive for the 'Film industry' Category

A man and his Focus

James Schamus on State Street, hailed by local livestock.

DB here:

“I wish,” one of my students said during a James Schamus visit to Madison back in the 1990s, “I could just download his brain.” Probably many have shared that wish. James is an award-winning screenwriter who has become a successful producer and head of a studio division, Focus Features (currently celebrating its tenth anniversary). No one knows more about how the US film industry works than James does. Yet he’s also deeply versed in the history and aesthetics of cinema. He teaches in Columbia’s film program, and his courses involve not filmmaking but film theory and analysis. How many people who can greenlight a picture have written an in-depth book on Dreyer’s Gertrud?

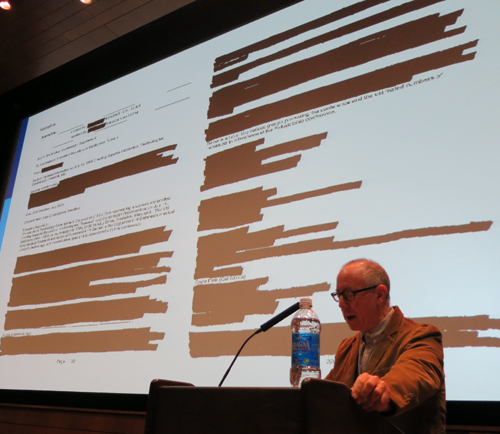

James came to campus last month for our Wisconsin Film Festival. His official event, sponsored by the University Center for the Humanities, was a talk called “My Wife Is a Terrorist: Lessons in Storytelling from the Department of Homeland Security.” That was quite an item in itself, tracing how James’ wife Nancy Kricorian discovered that she had a Homeland Security file. Pursuing that led him to broader meditations on digital surveillance in modern life. If he’s invited to present this in a venue near you, you’ll want to catch this provocative tutorial in how to read a redacted document.

While he was here, James spent a couple of hours in J. J. Murphy’s screenwriting seminar, and of course I had to be there. Herewith, some information and ideas from a sparkling session.

All battleships are gray in the dark

Hulk.

“This is not writing,” Schamus said. By that he meant that a screenplay isn’t parallel to a piece of creative writing, an autonomous work of art. Nobody ever walked out of a movie saying, “Bad film, but a great script.” In this he echoed Jean-Claude Carrière at the Screenwriting Research Network conference I visited back in September. A screenplay is “a description of the best film you can imagine.”

What sort of description? For certain directors, sparse indications are best. Collaborating with Ang Lee, Schamus knows he must under-write. Lee doesn’t want a movie that’s wholly on the page: “Ang wants to solve puzzles.” But for a studio project, the screenplay has to be airtight, since it functions as an insurance package for any director the producers hire. “A script has to be a battleship that no director can sink.”

James pointed out a bit of history. Back in the 1910s Thomas Ince rationalized studio production by using the script as the basis of all planning—budget, schedule, locations, and deployment of resources. The same happens today, with the Assistant Director breaking down the script for different phases and tasks of production. But on a studio project not everything is tidily planned in advance. Scripts can be rewritten during shooting or even later. Sometimes there are “parallel scripts”: stars can hire writers who spin out “production rewrites” to be thrust on the director. James, who has prepared the screenplay for Hulk and done his share of uncredited rewrites on other big films, speaks from experience.

Independent companies rely on screenplays too; Focus is writer-friendly. But in this zone of the industry, the writer needs to create a “community” around a script idea—a director or group of actors and craft people that support it. These are as valuable as a polished screenplay in getting a film funded.

What about the current conventions, like the three-act structure? James rejects the Syd Field formula. He thinks that the writer will spontaneously devise some intriguing incidents and arresting characters without recourse to beats, arcs, and plot points. “You can’t have half an hour go by without giving your characters something to do, or to shoot for.”

He also suggests that the writer’s second draft should be an exercise in rethinking the whole thing. “Don’t write your second draft from the first-draft file.” In your redraft, use flashbacks, play around with structure, or tell the action from a different point of view. This will engage you more deeply with the material and show you possibilities you hadn’t imagined. In terms I’ve floated in various places: take the same story world, but recast the plot structure or the film’s moment-by-moment flow of information (that is, its narration). Or try choosing a different genre. For The Wedding Banquet, James turned the original script, a melodrama, into a situation derived from screwball comedy.

Down in the mosh pit

Jim Carrey in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind.

James has been both an independent producer, in partnership with Ted Hope at Good Machine during the 1990s, and a specialty-division producer with Universal for Focus. The moment of passage for him came when, rewriting Ang Lee’s first feature, Pushing Hands, James realized that he had to get the whole project in shape for filming. After that, and The Wedding Banquet and Eat Drink Man Woman, producing followed naturally.

When James started, a single person could cover most producer duties on an indie film, but now it’s very difficult. Finding material, gathering money, signing talent, checking on principal photography and post-production, planning marketing and distribution across many platforms, tracking payments after release—it’s all a daunting task for one individual. Today an indie movie may list seven to twenty producers. Some probably helped by finding money, some worked especially hard to get material, and a few just slept with somebody.

A traditional producer’s job is to keep the budget under control. Today, with digital filming making special effects cheaper, screenwriters and directors think naturally of more elaborate visuals. This can work with something like Take Shelter, James suggested, but on the whole he thinks that directors shouldn’t jump to extremes. He recalled that using “handcrafted effects” cut the original budget of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind by a third, and that led to more unusual creative results, like outsize sets and in-camera trickery.

The “independent cinema” scene has always been quite varied. Again James had recourse to history: in the 1960s both United Artists and Roger Corman were labeled independents. The artier independent side developed through the infusion of foreign money and new technology. From the 1970s onward, overseas public-television channels invested in US films by Jarmusch and others, while cable and home video needed product and so financed or bought indie projects. The video distributor Vestron, for instance, could not acquire studio films, so, armed with half a billion dollars, the company began generating its own content. In the same era, pornography was shot on 35mm, and many crafts people learned in that venue and transferred their skills to independent cinema.

Today, however, the indie market is both more fragmented and more fluid. The spectrum space between tentpole Hollywood and DIY indies is being filled by net platforms and cable television. James pointed to the ease with which Lena Dunham moved from Tiny Furniture to the HBO series Girls. Downloading and streaming add to the churn. IFC and Magnolia distribute films, but these companies are owned by cable channels and hold theatrical venues as well. They acquire scores of new films a year, using theatrical releases to get reviews that can support VOD and DVD. Focus can tier its marketing in similar ways, using DVD and VOD outlets to lead viewers to content online under the rubric Focus World.

These new “paramarkets,” James suggests, are porous, overlapping, and still evolving. Traditional windows, he says, have become a mosh pit.

James had a lot more to say, and I expect to be referencing more of his ideas on VOD in a blog to come. But this gives you a taste of the energy and breadth of his thinking. He’s constantly busy but never less than enthusiastic and generous. He always has time to share ideas about anything, from politics to cinephilia. The most exhilarating thing about talking with him is that you know more excellent work lies ahead.

Apart from titles I’ve already mentioned, James Schamus’ screenplays include The Ice Storm, Ride with the Devil, Taking Woodstock, Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon, and Lust, Caution, Films that he produced and/or distributed include Poison, The Brothers McMullen, Safe, Walking and Talking, Happiness, The Pianist, 21 Grams, Lost in Translation, Shaun of the Dead, A Serious Man, Coraline, Brokeback Mountain, The Motorcycle Diaries, Eastern Promises, Atonement, Reservation Road, In Bruges, Milk, Sin Nombre, Greenberg, The Kids Are All Right, The Debt, Pariah, Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy…and plenty more.

Schamus provides a video review of the top ten Focus titles chosen by viewers for the company’s anniversary.

J. J. Murphy blogs about screenwriting, the avant-garde, and independent film here. His most recent book is The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol.

More on the concepts of story world, plot structure, and narration can be found in “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative,” in my book Poetics of Cinema. A brief account is here.

James Schamus lecturing, University of Wisconsin–Madison Center for the Humanities, 19 April 2012.

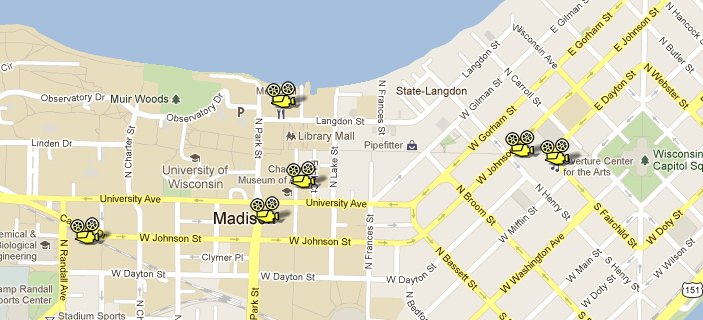

One summer does not a slump make

Kristin here:

Nor does an entire year. Yet at the end of 2011, the press was trumpeting the fact that the film industry was suffering a slump that might become permanent. After all, “the movies are in a slump!” makes for more catchy copy than “the movies have sunk back to normal” or “the movies are in a downturn from which they will probably recover.” The Hollywood Reporter went for a particularly dramatic approach to year-end coverage of the slump, as evidenced by the title/illustration (see above) of Pamela McClintock’s analysis, appearing in the January 13, 2012 print issue and online.

McClintock cited a number of factors. Young people are no longer going to the movie theaters. The studios are too dependent on big, familiar franchise pictures: “But exhibitors worry that moviegoers are growing impatient with Hollywood’s love affair with the familiar and shortage of original ideas (hello, Avatar!). In 2011, for the first time ever, all of the 10 top-grossing films domestically were franchise titles and spinoffs.” (But wouldn’t that mean that moviegoers are more than ever thrilled with Hollywood’s franchises?) She cites also the rise in admission costs, with ticket prices going up by 5% from 2009 to 2010.

That reason seems the most plausible. People really are tired of ticket prices that have risen faster than inflation. The industry may have pushed the cost up past a point that makes an evening at the movies seem attractive. If, as seems likely, the industry will raise the cost of 2D tickets rather than dropping the cost of 3D ones, we may see a real slump.

The 800-pound thanator in the room

Hollywood box office has its ups and downs, which is only to be expected. One year the successful releases cluster together; another year, they spread out or drop off a little. Any decline will be seized upon by many reporters as a slump, a sign that people are souring on the movies and turning to the many other forms of pop-culture entertainment available in the digital age.

Careful commentators have pointed out that naturally 2011 would be lower than 2010. As the AP’s film reporter, David Germain put it at the end of 2011, “An ‘Avatar’ hangover accounted for Hollywood’s dismal showing early this year, when revenues lagged far behind 2010 receipts that had been inflated by the huge success of James Cameron’s sci-fi sensation.”

Just how much did Avatar affect 2010’s box-office total? The film achieved a worldwide total gross of $2,782,275,172. Of that $1,786,146,809 came in during 2010. That’s comparable to, say, two Harry Potter films.

Predictably, Avatar ran for a long time. It was released on December 18, 2009 and ran for 238 days (34 weeks), closing on August 12, 2010. Naturally its most intense box-office period in 2010 would have been in the early months. Alice in Wonderland opened on March 5, on its way to crossing a billion dollars in international gross. This was a highly unusual synchronization of steamroller films. Still, in early 2011, the fact that the box office was off 20% from 2010 was immediately proclaimed as a signal of doom and gloom to come. Richard Verrier and Ben Fritz suggested that, putting aside some under-performing films, “even hits like Justin Bieber’s ‘Never Say Never,’ ‘The King’s Speech’ and ‘Battle: Los Angeles’ pale in comparison with the early 2010 blockbusters ‘Avatar’ and ‘Alice in Wonderland.’” Given that the first few months of the year are typically the dumping ground for films deemed unlikely to set the box-office on fire, early 2011 was a return to business as usual. Avatar and Alice in Wonderland hardly made for a realistic comparison.

The tentpole effect

We’ve seen that Avatar’s 2010 box office was comparable to two major blockbusters. Now consider the fact that two films released in 2010 grossed over a billion dollars each: Toy Story 3 ($1,063,171,189) and Alice in Wonderland ($1,024,299.904). (Here and throughout this entry, the amounts are given in unadjusted dollars.)

That’s the equivalent of having four very high-grossing films in one year. The only other time a similar pattern emerged was in 2002, when four of the top franchises brought forth a film: Spider-Man ($821,708,551), Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets ($878,979,634), The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers ($926,047,111), and Star Wars: Episode II – Attack of the Clones ($649,398,328). It was a perfect storm that has so far not been repeated.

These are exceptional years, so one would expect the box-office to sink afterward. Yet somehow the industry and the world of entertainment journalism see years with such big box-office spikes as forming the new norms against which all other years should be judged. Studio executives seem to think that 2002 or 2010 indicate a realistic goal that they could achieve all the time, if only they could put out the right films. Almost inevitably, articles on declines in box office end with the notion that the films released in that particular year or quarter were just not appealing enough. But of course, there’s no way to deliberately achieve such a combination of blockbusters. Many blockbusters fail, and the big special-effects-laden ones take years to lumber through production. By sheer coincidence, some blockbusters converge.

The lesson to be learned here is that the really big films make so much money that just a few of them–or one James Cameron epic–can by themselves create the sense of the entire Hollywood output going way up or way down. They average out. If Hollywood attendance is dropping, it’s happening very slowly. Other factors are making up for that gradual attrition, as we’ll see below.

2002 was 2002

Journalists in particular have long been using 2002 as a benchmark to measure how badly Hollywood has been doing since. Ben Fritz and Amy Kaufman, in an otherwise good analysis written for the Los Angeles Times, resort to this comparison: “The box-office figure known in the industry as the ‘multiple’—the final box-office take compared to a movie’s opening weekend ticket sales—has dropped 25% since 2002.” The 2002 figure might have been skewed slightly by the fact that the three parts of The Lord of the Rings had an extraordinarily high incidence of repeat viewings and hence were in first run far longer than most films. For The Two Towers, the opening weekend was 18.2% of its total domestic gross (up from 15.1% for the previous part, The Fellowship of the Ring, which was in first run from mid-December, 2001 to August, 2002, half a week longer than Avatar). Spider-Man’s opening was a more typical 28.4% of the total; Attack of the Clones was 26.5%, and Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets, 33.7%. A more recent film with above average repeat business, Inception (2010), drew only 21.5% in its opening weekend. With Iron Man 2 (2010), the opening was 41.0% of the total gross. Good word of mouth is another possible explanation for some films’ steady or even growing performances after their opening weekends. By the way, the fact that Fellowship of the Ring was in theaters for seven months in 2002 boosted the total box-office beyond the rise created by the four franchise films that premiered within that calendar year.

It’s not clear that the growth in the proportion of the box-office take represented by the opening weekend is directly related to the drop in attendance, as Fritz and Kaufman suggest. One might instead point to the growth in the number of screens, with new megaplexes opening and existing ones adding screens. In 2002 there were 35,500 US screens, but by 2011 there were over 39,300–an increase of nearly four thousand screens. They provide more exposure to the title on opening weekend.

Further evidence is the expansion of opening weekend releases. It was unheard of in the early 2000s to have even a major blockbuster open on 4000 screens. Now it’s not uncommon. At its widest release, The Two Towers was in 3622 theatres, while Iron Man 2 was in 4390. With that many theaters, the number of people able to get tickets for the opening weekend grows, which means that, unless a film generates significant repeat attendance or excellent word of mouth, the box-office take will fall off more rapidly than it used to. But the fall-off doesn’t necessarily mean that fewer people have bought tickets.

Oops! Never mind

The story of the slump suddenly began to look very different as soon as the new year began. At the end of February 2012, Variety reported that domestic box office for the first two months was up 21% over the same months of 2011. It so happens that in the same period of 2011, box office was down 20% against the early months of 2010. And the early months of 2010 saw Avatar going very strongly after its mid-December debut.

The Variety article’s author, Andrew Stewart, pointed out the fact that Avatar had unbalanced the 2010 results. He also pointed out that the fast start out of the 2012 box-office gate resulted from a larger number of films making less on average. But this year’s likeliest high-grossers are yet to come: The Hunger Games, The Dark Knight Rises, and the first part of The Hobbit, with The Bourne Legacy and The Amazing Spider-Man possible mega-hits as well. There are also new films in the Madagascar, Ice Age, and Men in Black franchises coming out. Ann Thompson weighed in a few days after Stewart, pointing out that the increased number of films was not necessarily a problem, since more theaters are being built at a fast clip around the world. More theaters theoretically need more product. (More on that below.)

But an important point about the early hits of 2012 is that they were relatively modest films. They could have been expected to earn far less than blockbusters but still perform well in relation to their production and distribution costs. The Vow, the first film of the year to cross $100 million, is a romance; Safe House a Denzel Washington thriller; and Journey 2: The Mysterious Island a mid-budget family adventure film. This is pretty much what a normal, non-Avatar year looks like early on. (In 2008, David wrote about one early-in-the-year release that was a modest hit, Cloverfield.)

Soon thereafter Chronicle, made on an announced $12 million budget, had pulled in about ten times that internationally and proven that young men, contrary to industry fears, were still willing to go to see movies in theaters. Then The Lorax became the first iron-clad blockbuster. Neither of these is part of a franchise. Talk of a 2011 slump has disappeared. I suspect it may resurface a year from now as a benchmark showing how extraordinarily well Hollywood films did at the box office in 2012.

The 3D effect

2009 and 2010 were the best years for 3D, with Avatar not only dominating world film screens but also luring producers to imitate its success. But in 2011, the advantage provided by the higher ticket prices that 3D permitted began to fade. Last summer I discussed the decline at some length, here and here. I won’t rehash that here. In 2009, 3D films made on average 71% of their box-office grosses from 3D screens, and in 2010 the figure was 67%. In 2011, 56% of business for 3D films came from 3D screens.

The decline may represent the end of the novelty appeal of 3D, as well as the increasing number of 3D films competing in the market. Anecdotal evidence suggests that moviegoers are tired of paying premium prices. The fact that 3D animated features took in a slim one-third of their grosses from 3D screens in 2011 suggests that the cost of a whole family attending together, especially if the younger children can’t keep the glasses on, has begun to hamper the format.

Thus 3D may have contributed to an artificial, temporary rise in total box-office figures in 2010. This would inevitably be reflected as a decline in 2011, as more people opted for 2D screenings of popular films.

(Figures from Screen Digest, February, 2012, p. 37.)

It’s a big, wide, ticket-buying world out there

All the box-office reports and prognostications discussed above are based on domestic box-office grosses, which in practice means the USA and Canada. But in parallel to the reports of a slump in 2011 BO figures, there were reports of impressive growth in foreign film markets.

Take the United Kingdom, traditionally a top consumer of Hollywood films. 2011 saw the total box-office gross surpass £1.5 billion for the third straight year. That total grew by 5% over 2010. Films from Hollywood’s Big Six studios took 74% of the market. Local productions had a particularly good year, with three in the top ten: The King’s Speech, The Inbetweeners Movie, and Arthur Christmas. Even if that success continues, however, Hollywood will have a healthy share of the market.

More generally, Variety announced in mid-January, “It was business as usual at the 2011 international box office. And business is booming.” (“International” refers to all markets apart from the USA and Canada.) The Russian market is growing quickly, with its total gross of $1.16 billion in 2011 representing a rise of 20% from 2010. Russian films make up only 14.7% of the market, with the rest mostly coming from Hollywood.

The Chinese market is huge, passing $2 billion for the first time in 2011, up 29% over the previous year. (See below.) There is a Chinese quota of 20 foreign films per year, but a recent decision to allow more 3D and Imax films in may herald a gradual opening of the market. Certainly the blockbusters that make their way into China are popular. According to Hollywood Reporter, for the first time, China was Paramount’s highest grossing foreign territory, with $303 million at the box office, largely thanks to Transformers: Dark of the Moon. Still, China yields only about 15 cents on the dollar back to the distributor, a situation likely to change only slowly.

Brazil, India, and Eastern Europe have seen healthy expansion as well.

Even Hollywood comedies, notoriously hard to sell abroad, are becoming more popular. In 2011, Bad Teacher, Just Go With It, and Friends With Benefits all made around $100 million outside North America. Very unusually for comedies, they also grossed more money abroad than domestically.

The major studios’ box-office grosses abroad were: Paramount, $3.19 billion; Warner Bros., $2.86 billion; Disney, $2.2 billion; Fox, $2.15 billion; Sony, $1.83 billion; and Universal, $1.3. (These figures represent the total amount paid for tickets; only a portion returns to the studio.) I take this information from Hollywood Reporter, which notes that the big studios are increasingly buying local, foreign-language films to distribute within those domestic or regional markets.

There’s more to Hollywood than tickets

One might conclude from all the stories about the box-office slump of 2011 that the big studios’ profits would be down, at least a little. Actually, a studio had to work hard not to see profits rise last year. That’s partly because they make things other than movies and partly because movies make a lot of money that has no direct connection with theatrical distribution.

The February 24, 2012 issue of The Hollywood Reporter published a helpful summary, “2011 Profitability: Studio vs. Studio.” (The online version is behind a paywall.) As the authors point out, the studios calculated their profitability on different criteria, so direct comparisons among them are difficult. Nevertheless, the article shows that most studios were profitable and suggests why.

Time Warner’s filmed entertainment wing had a 15% rise in profits from 2010 to 2011. That resulted in part from the release of the final Harry Potter film. Beyond that, however, there was the fact that WB now manufactures video games and shipped 6 million copies of Batman: Arkham City. (That game wouldn’t exist without the film series, so we see synergy at work here.) It also produces over 30 TV programs, including The Big Bang Theory and Two and a Half Men.

News Corps.’s film studio, Twentieth Century Fox, saw profits rise 9%. Rise of the Planet of the Apes boosted the bottom line, but so did strong home-entertainment sales. The TV wing produced Glee and Modern Family. “Films licensed to pay TV and free TV helped, as did digital content-licensing deals. The TV licenses are estimated to have been worth about $200 million in the second half of the year.” Thus quite apart from their box-office takings, films made a lot of money for the studio.

The profit from Sony’s film unit jumped an impressive 95%. $278 million of that was a one-time sale of merchandising rights for the new Spider-Man movie. The Smurfs was the studio’s top earner at the box-office, and according to The Hollywood Reporter, “The division also benefited from stronger-than-expected DVD sales of The Green Hornet and Battle: Los Angeles.”

Disney was the only studio to face a decline in profitability. Its profits slipped 20.5%, though they were hardly meager at $656 million. The disappointments of Mars Needs Moms and Cars 2 are largely to blame. Disney’s current attempt to create a new blockbuster franchise in John Carter clearly won’t reverse the trend.

Paramount’s profits were the lowest but improved the most in 2011: 128%. The growth seems due largely to the Transformers franchise and high income from a 2010 deal between Epix (Paramount’s 51%-owned VOD channel) and Netflix.

The Hollywood Reporter was unable to obtain figures for Universal.

This overview hints at the underlying factors that make assessing the health of the film industry through box-office figures alone a shaky process. Ideally we would have figures on DVD and Blu-ray sales, as well as on licensing deals for streaming and other digital distribution systems. But this information isn’t made public by the studios.

The uncertainties and appeal of post-theatrical markets

This is a pity, since the real crisis facing the film industry today is not fluctuations in box-office income. It’s how to deal with the rapidly changing post-theatrical revenue stream: the sudden proliferation of other ways to sell or rent films for viewing on the tablets, game consoles, cell phones, computers, and other devices now driving the death of tape- or disc-based home entertainment. Studios see new ways to make money and are at war with exhibitors about how short a window there would be between theatrical release and the various forms of video release.

Early in this proliferation of online-based distribution, studios continued to concentrate on selling DVDs and later Blu-rays. They licensed the rights to rent films on DVD or via streaming to Netflix and other companies. Now they’re beginning to realize that they don’t need the middleman, but they haven’t found models for handling all forms of post-theatrical distribution themselves. In the meantime, Redbox kiosks rent DVDs for a pittance and make the home-video experience seem like something that barely needs to be paid for–and certainly isn’t an Event.

The decisions the studios make about post-theatrical are crucial to the health of the film industry. Movie City News publisher David Poland recently summed up the situation, pointing out that the theatrical release is still far and away the biggest single generator of income per viewer for the industry. His essay is worth reading in full, but here is the gist in terms of how home-entertainment revenues relate to theatrical income:

1. Post-theatrical is already a blur for consumers and it will only get more so. People will expect access at all times on any device for a low, low price… either in a subscription model or a per-use price point of $2 or less.

2. Theatrical will soon be the ONLY revenue opportunity that stands apart from that post-theatrical blur. No other revenue stream will ever again generate as much as $10 a person… or even $5.50 per person.

3. Consumers adjust to whatever window you offer. But history tells us, the shorter the theatrical-to-post-theatrical window for wide-release movies, the more cannibalism of the theatrical.

4. Just as the DVD bubble could not be pumped back up after it was deflated by pricing aggression, theatrical will not survive a significantly shorter window to post-theatrical as we now know it… and once it is broken, it will not be able to be fixed. And that revenue stream will NOT be replaced by what is now post-theatrical. It is simply money that will be lost, never to be recovered.

Theatrical will never be The Drink again. You’re looking at a 2 month window for most studio films vs decades of post-theatrical revenue opportunities. It’s not an even fight. But take a deep breath and look at the obvious… for theatrical to still be as much as 40% of the revenue of a studio film is bloody amazing. It’s not the past. It’s not ’39 or ’69 or even ’89. But it’s a LOT of money. And it is insane to take it for granted or to dismiss it, because there is no proof out there that I have ever heard that suggests that theatrical revenues gets in the way of post-theatrical revenues… only the other way around. Why? Because theatrical is the unique proposition. It’s post-theatrical that really has to compete with EVERYTHING the world has to offer.

(David’s post came in response to one by Mike Fleming on Deadline.)

If the studios start selling their films in various digital forms for a dollar or two, and do so in ways that cannibalize the theatrical market, there will come a point where many people stop going to theaters and stay home to do their movie viewing. So there will need to be many more purchasers of that film than there currently are to make up the difference between that cheap sale and the price of a movie ticket. Without a boost in consumers, post-theatrical income would fall, and the studios wouldn’t be able to afford to make the sorts of films that currently generate the most money.

Whether David’s analysis is too pessimistic remains to be seen. But he points to a far bigger problem than a largely illusory drop in box-office figures.

Jumping to conclusions

The notion that 2011 saw a serious slump results from comparisons that make for catchy headlines. But sometimes a situation can prove misleading. Consider the title of a Variety article from February 23 of this year: “Imax profit plunges to $6.3 million.” Can this be the end of Imax? Yet read on:

Imax profit fell last quarter to $6.3 million from $54 million, mostly on a major tax benefit the year before. Revenue eased by $2 million to $67 million.

Without the tax and other items, income fell to $9 million from $14 million, in line with expectations given a soft box office.

The company said 2011 was a year of record signings and installations, with 497 Imax theaters installed in commercial multiplexes, up 33%, led by China, Russia and North America. CEO Rich Gelfond said the company will add focus on South America, including four new theaters in Brazil, Western Europe and India, where a recent deal will bring Bollywood titles to Imax. It will expand local film production from China into Russia and France.

(Note: The title of this story was subsequently changed to “Imax, Dish, Liberty stocks rise” when it was revised to add the fact that Imax’s stock rose 4.5% on the above news.)

The moral is, the obvious interpretation is not always the correct one. The implication of box-office fluctuations needs analysis beyond a simple comparison of ups and downs from one year to the next.

Moviegoers at the Super Cinema World in the Metro City shopping mall, Shanghai, China

John Ford and the CITIZEN KANE assumption

Kristin here:

A few days ago I was reading the February 24 issue of Entertainment Weekly. I started subscribing to EW during the days when I was working on The Frodo Franchise. Being a Time Warner publication, it tended to feature The Lord of the Rings a lot (Time Warner also owns New Line Cinema). I was trying to keep track of the popular-press coverage of the film, and EW was a helpful source. It also used to be a bit more substantive in those days. In recent years it has become more fluffy. Still, it’s handy for reading over lunch or when brushing one’s teeth.

Turning to page 66, I found Chris Nashawaty’s “The Most Overrated Best Picture Winners.” The double-page spread was slathered with photos of My Fair Lady, Out of Africa, Gandhi, The King’s Speech, and Shakespeare in Love. (The piece is online, but as a gallery rather than an article, lacking the introduction.)

I like putdowns of overrated and/or over-rewarded films as much as anyone, so I settled in to read. I was shocked, however, to find that the first film on the list was How Green Was My Valley.

I happen to think the How Green is one of the very greatest American films. Probably no Best Picture winner in the history of the Oscars has been a more fitting recipient of that award. Why lump it in with Shakespeare in Love?! (I think you know what’s coming.)

Nashawaty gives his reasons. He admits that How Green has three pluses going for it: “It’s got beautiful cinematography, John Ford as a director, and a three-hankie plot about a Welsh mining village.” He goes on: “The minuses: mismatched accents and the still-outrageous fact that it beat Citizen Kane.”

Mismatched accents as a reason not to win Best Picture? The notion belittles the brilliant ensemble acting in Ford’s film, with Donald Crisp, Sarah Allgood, Barry Fitzgerald, Maureen O’Hara, Walter Pigeon, and many others giving fabulous performances, career bests in some cases. It is a joy to watch them interact. Of course most of these people sound more Irish than Welsh, but frankly, who cares?

By the way, I’m assuming Nashawaty means the mismatch of Irish accents to a Welsh setting, not a miscellany of accents among the cast, which is common in Hollywood films. Besides, isn’t accuracy of accents—think Meryl Streep—one of the criteria used to judge the very Oscar-winners that Nashawaty is decrying? I’ve never seen Gandhi, but I’ll bet Ben Kingsley did a heck of an authentic accent. Accents are one of the easiest aspects of performances to notice, so it’s not surprising that they are so often a factor in Oscar-nominated and -winning roles.

But it’s not really the accents that bother people about How Green. No, it’s really the “beat Citizen Kane” part that grates on film fans. Quite possibly it has led them to dismiss or undervalue one of Ford’s greatest films.

I’m going to be heretical and say that How Green deserved to win over Kane.

For years Kane has been sitting atop many lists of the greatest films of all times, including polls of professional film critics. The notion that Kane really is the greatest film of all time has become so engrained that people seem seldom to question it. Back when that idea arose, critics were unaware of the films of Yasujiro Ozu, probably the world’s greatest film director to date. Play Time was for years ignored and only recently has begun to be recognized for the masterpiece it is. With the rise of film restoration in the 1970s and the spread of film festivals and retrospectives, we now know vastly more about world cinema than we did before. Yet Kane has settled into its top slot for many people, including entertainment journalists. I can think of many films I would rank above Kane.

No doubt it’s a great film, with a marvelously tricky plot, another great ensemble of actors, splendidly distinctive cinematography, and innovative special effects masquerading as cinematography. It was hugely influential at the time and remains so to this day. Of course, Welles has declared time and again that he learned filmmaking by watching Stagecoach over and over, so Kane would probably not be as good as it is without Ford’s influence. Not that such influence proves that How Green is better than Kane, but it shows Welles’s respect for Ford. More on that below.

Middlebrow and proud of it

I think another reason why How Green tends to be dismissed as merely the film that cheated Kane out of its best-picture Oscar is that it is resolutely middlebrow. Indeed, in that way it fits in with all the other films Nashawaty writes about. They’re all resolutely middlebrow, too. Middlebrow films are for those people who look down upon popular genres and want to feel they’re seeing something worthwhile.

Despite this attitude, most of the great American films fit into popular genres: Keaton’s The General (or substitute your favorite Keaton film), Kelly and Donen’s Singin’ in the Rain, and Hitchcock’s Rear Window (or, if you will, Shadow of a Doubt or Notorious or Psycho). This is one thing that the auteur theory, somewhat indirectly, taught us. Howard Hawks’s modern reputation rests partly on his ability to waltz into any American genre and make one of its best entries. The Godfather is technically a gangster film, but one could argue that by taking it from a bestseller and making it into a glossy A picture, Coppola pushed his film into the middlebrow range far enough for the Academy to dub it Best Picture—twice. The one Best-Picture winner of recent decades that arguably did thoroughly deserve the prize was a serial-killer thriller, The Silence of the Lambs. I think a lot of people were surprised that the strait-laced Academy members could accept such subject matter in a nominee, let alone a winner.

Like Hawks, Ford moved easily among genres and excelled at least once in every one he touched. He made arguably the greatest war film ever, the underrated They Were Expendable, and the greatest Western, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (or Stagecoach or My Darling Clementine). He also pulled the turgid middlebrow genre of the 1930s biopic into greatness with Young Mister Lincoln. There’s no doubt that Ford was an uneven director, and arguably his worst films arose from his attempts to go for middlebrow respectability. The Fugitive is almost unwatchable in its pretentiousness, and the mid-1930s brought forth such items as Mary of Scotland and The Informer. But starting in 1939, he produced an almost unbroken string of masterpieces and near masterpieces, culminating in They Were Expendable and My Darling Clementine.

We should recall also that Welles himself adapted a middlebrow bestseller for the film he made directly after Kane: The Magnificent Ambersons. Had the studio not meddled so extensively with it, it probably would have been one of the American cinema’s great middlebrow classics, fit to sit alongside How Green.

Earned sentimentality

Welles himself probably would have felt honored by that comparison. In a 1967 interview he described his taste in films:

Old masters—by which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford. With Ford at his best, you feel that the movie has lived and breathed in a real world—even though it may have been written by Mother Machree.

In other words, Welles recognized that sentiment did not take away from the brilliance of Ford’s best work, and How Green is definitely in that category. Welles was too big an egotist not to have been annoyed at losing the Best Picture award to Ford, but he probably understood why How Green won better than most people do today. Today, apart from groups of women who go to see heartwarming female-oriented fare, audiences tend to shy away from sentimentality.

To his credit, Nashawaty lists sentimentality as a plus for How Green. (“Three-hankie plot” has a dismissive ring to it, but I’ll chalk that up to the requirements of infotainment journalese.) But I’m sure that many people who underrate How Green do so because it’s essentially a family melodrama where everything starts out in an Edenic state and the situation slowly goes downhill to a distinctly unhappy ending for all concerned. A lot of people simply dismiss sentimentality in all its manifestations, presumably as too naive, hitting us below the belt for an easy emotional appeal. In this day and age, it is much easier to admire cynicism than unembarrassed emotion. Despite its subject matter of environmental depredation by greedy companies, How Green is resolutely focused on the joys and sorrows of the family. Kane is cynical in a very modern way. Yet I cannot believe that we care nearly as much about the characters in Kane, even Susan, as we do in How Green.

Sentimentality is not a bad thing in itself. Sure, it’s an easy thing to evoke. Easy sentimentality is banal and cloying because there’s so little underpinning it except conventional romance and cute babies and long-suffering mothers and the like. Then there is what I call earned sentimentality. (A similar distinction is often made between sentiment and sentimentality.) Films with this quality are rich with original characters and situations that might make even a viewer who dismisses easy sentimentality pull out a hankie. The sentimentality in Chaplin’s films sometimes achieves this, and his Little Tramp character has been widely praised over the decades for his mastery of this emotion. Even those who dismiss sentimentality can forgive Chaplin, since humor usually undercuts the cloying quality just a bit. In a less obvious way, Harold Lloyd sometimes proves himself a master of sentimentality, as in The Kid Brother. And earned sentiment is not dead. It pervades Big Fish, another film that has been underrated or at least largely forgotten, perhaps in part due to its sentimentality. It has eccentrics galore and an original plot idea, but it doesn’t have that edgy, weird quality that sophisticated viewers treasure in Tim Burton’s work. There’s even sentimentality in the Wallace & Gromit films, though again humor makes the emotion palatable. Art cinema has its own sentimental masterpieces: Bicycle Thieves, Jules et Jim, Tokyo Story, Sansho the Bailiff, Distant Voices, Still Lives, and the list could go on and on. True, all these films are grimmer in part or in whole than the average Hollywood film, but so is How Green.

By the way, Welles himself delivers one of the sublime sentimental passages of world literature in the heartbreakingly nostalgic “chimes at midnight” speech in Falstaff, which has other passages of the same emotion. The Magnificent Ambersons is a sentimental film of a different sort.

For my money, How Green earns its sentimentality as well as any film ever made.

On everyone’s syllabus

You may be asking at this point, if How Green is so fantastic, why didn’t Bordwell and Thompson use it as their central example of a narrative film in Film Art? Why is Kane in that spot? There’s a simple answer to that: Kane is a very teachable film, and How Green, to say the least, is not. Our challenge was to find a film that most teachers used, or would happily start to use, and that demonstrated many concepts about film narrative and style that we wanted to describe.

Some films are just more teachable than others. They use a lot of different techniques, both stylistic and formal, in a way that students can notice. Hitchcock is probably the most teachable director overall, and I would bet that his films show up on introductory-film-class syllabi more often than any other director’s. It’s just that with Hitchcock, there’s no one film that’s self-evidently more useful for teachers than others. I sometimes think that one could almost write an entire introductory textbook using nothing but examples from Lang’s M. There are other classics like that. But Kane beats them all: a complex but clear flashback structure, obvious and varied technique, a complex soundtrack born of Welles’s radio experience, and examples of many things teachers want their students to learn about. It’s a classical Hollywood film, but it has touches of art-cinema ambiguity about it. It’s entertaining, at least to motivated students, so they’re likely to pay attention rather than dismissing it. They may come into the class knowing that it’s a revered classic and hence be interested in seeing it. It may even reconcile them to watching black-and-white films.

How Green, however, is difficult to teach. David has found this to be true. Our colleague Lea Jacobs occasionally offers a seminar on Ford, and How Green is among the most challenging films by a director whom students tend to be slow to warm up to. She attributes this partly to changing tastes and partly to the subtlety of the style of its cinematography. It’s very hard to make students, and indeed almost anyone who isn’t already a believer, see why How Green is a masterpiece.

Kane is not only teachable, but it’s highly conducive to analysis, and no doubt these two traits are closely related. David’s first widely seen article was a study of Kane, and I wrote the sections of chapters in Film Art dealing with it. I don’t mean that it’s simple; Kane is a complex film that has provided material for many different essays and books. But How Green has so many ineffable qualities that it resists cold, precise analysis. It has been one of my favorite films for over three decades, and occasionally I have contemplated writing something in-depth about it. I can’t, however, think what one could possibly write. One would just have to throw up one’s hands and say, “You either get it or you don’t.”

It reminds me of when I was nearing the end of my undergraduate career. I didn’t “get” Godard. I found his work pretentious and boring. But given how many people whose opinions I respected admired Godard, I persisted. I think I suffered through seven features, and at about number eight (Weekend), I got Godard. Maybe Ford, at least for his non-Western films, is somewhat the same sort of challenge. I’ve written analyses of two of Godard’s more difficult films, Tout va bien and Sauve qui peut (la vie). I’m still scared to try to deal with How Green.

(Stagecoach is much easier. For several editions of Film Art we included an analysis of it, which I wrote. Eventually it got replaced, but it’s still available here.)

A few hints

Since I doubt I will ever thoroughly analyze How Green, here I’ll offer just a few hints as to why it deserved to take home Best Picture and leave Kane an also-ran.

Nashawaty mentions the beautiful cinematography. Arthur C. Miller was 20th Century-Fox’s A-list cinematographer, having shot some of the Shirley Temple films in the 1930s, films that kept the studio afloat during the Depression. He teamed with Ford only on Tobacco Road and How Green, though he apparently helped with Young Mr. Lincoln uncredited. Miller won his first Oscar for How Green, his second for Henry King’s The Song of Bernadette (the main virtue of which is it looks a lot like How Green), and his third for Anna and the King of Siam. Few of Miller’s non-Ford films like The Ox-Bow Incident and Gentlemen’s Agreement are watched much today. He did lens somewhat minor films by major directors (Hitchcock’s Lifeboat, Preminger’s Whirlpool), but he is less famous than he deserves.

Just a few examples. How Green contains some of the same techniques that are so admired in Kane, but in a less flamboyant fashion. Deep focus, for example:

Admittedly, the people at the right rear are slightly out of focus, but the shot was done in-camera. No special effects.

The interiors of How Green have a distinctive touch: patches of light on the ceilings. Implausible, when you start to think about where the light must be coming from, but beautiful nonetheless. Miller (or at least Fox) almost had a patent on this way of lighting a room. With Kane getting so much credit for adding ceilings to sets, we should remember that Ford has done so in Stagecoach and does it here as well. It’s not as in-your-face as Kane’s ceilings, but it’s an example of the subtlety that pervades How Green. The first shot (below) is part of the series of scenes at the beginning setting up the happy home life of the large and relatively prosperous Morgan family; the father is about to dole out allowances to his sons on payday. The second comes much later, as the last two grown sons prepare to depart abroad in search of work after the mine has declined.

Kane is admired for both its long takes and its dynamic editing. Ford seldom used either. He held a shot long enough to be effective but not long enough to turn into showing-off. Take the scene after Angharad’s marriage to the wealthy mine-owner’s son. Mr. Gruffydd, the minister whom she actually loves, has performed the ceremony. As has been pointed out many times, Ford filmed the final shot without doing any close views to be cut in later. (Indeed, most of How Green was edited in the camera by Ford, so that most of the footage he shot ended up on the final version. It was his way of keeping control over his film.) By happy accident, a breeze caught Angharad’s veil, sending it soaring and twisting through the shot. Perhaps it was a reflex gesture on the part of the actor playing the mine-owner’s son, but he reaches out and holds the veil down as his bride climbs into the coach; it perfectly captures his cold, proper nature. For a split second before the coach pulls away out right, Angharad glances back toward the church, where Gruffydd remains inside. Once the coach is gone, Ford holds, and Gruffydd appears on the hillside at the rear, watching and then turning to go inside. No cut-in mars the perfection of the shot.

There’s one of the hankie moments. I get tears in my eyes during this scene, partly out of sympathy of the sundered couple and partly from aesthetic pleasure. If ever there was a single shot that exemplifies Ford’s combination of sentiment and discretion, this is it.

The last of these five frames belongs to the visual motif that appears in the opening sequence, as Angharad waves to her father and Huw on the beautiful distant hillside (see above), as well as in the final scene, where Angharad struggles in her fine clothes across a similar hillside, swathed in smoke, to reach the mine after the disaster that traps her father (see below). Such moments create a quiet measure of the gradual degradation of the valley and the dwindling of the family’s happiness.

Did Ford realize how brilliant this shot was? We can be confident that Welles was well aware of how daring and wonderful his techniques in Kane were. It shows in the film. With Ford, one can only suspect that he knew exactly what he had accomplished here and elsewhere.

Another thing How Green shares with Kane is a flashback structure. It largely consists of one big flashback told by the protagonist, not a series of embedded stories by witnesses. Nevertheless it’s unusual, since we never come out of the flashback. The tale opens with the valley in severe decline, the village nearly deserted, and the hero about to depart for a better life. We witness the decline of his family as he grows, gets educated, and opts to follow his father and brothers into a job in the mine. By the end his elder brothers have scattered all over the world, his father is dead, and we don’t know what has become of his mother and sister. (One plausible assumption is that his mother has recently died, prompting his departure in the opening scene.) Yet the ending gives us a series of shots of the family as they had been in their prime, with the protagonist-narrator declaring, “Men like my father can never die.” Like Kane, it is a film about the power of memory, but in this case the power to comfort rather than to baffle.

One thing that makes How Green stand apart from some of Ford’s other films is that it for once controls the director’s penchant for mixing in broad humor. His stable of supporting actors playing minor characters who love to drink and fight can be trying. There is a particularly ill-advised moment in The Searchers when, after the epiphanic moment when Ethan has lifted Debbie as if to kill her and then embraced her, Ford cuts to the Ward Bond character having a wound on his posterior dressed, to the derision of his comrades. That Ford should undercut such a scene with a vulgar moment of comedy combines with another flaw or two in the film keep if off my list of Ford’s very best films. And much though I love the first three-quarters of The Quiet Man, that climactic brawl just goes on and on.

In How Green, the characters Dai Bando and Cyfartha provide humor, but they are held in check. They play reasonably significant roles in the action, helping Huw deal with the school bullies and his sadistic teacher. Many of the family scenes involve amusing moments as well, moments that arise naturally from the situations and have no air of mere comic relief. In screenwriter Philip Dunne’s introduction to the published version of his screenplay, he finds fault with several scenes and actors. Maybe he’s right that the scene when the mine owner visits the Morgan family is played for broad comedy, but it’s not as broad as elsewhere in Ford’s work. Luckily Ford’s brother Francis does not return for yet another of his bit parts as a drunk.

In 1972, when Ford was dying of cancer, the Directors Guild held an evening gathering to honor him. He was asked to choose one of his films to be projected, and he named How Green. He had consistently said he considered it his finest film.

There’s no budging Kane

I doubt that the notion of Citizen Kane as the Greatest Film of All Time will go away anytime soon. Changing (and unchanging) tastes are reflected in the decadal Sight & Sound poll of critics concerning the ten greatest films of all times. They started in 1952 and have continued to 2002, with another due this year. The lists reflect the fact that apparently critics can somewhat agree on the greatest older classic, though fashions in these come and go, but they cannot agree on much of anything that has been made since 1970:

1952

- 1. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica)

- 2. City Lights (Chaplin)

- 2. The Gold Rush (Chaplin)

- 4. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 5. Intolerance (Griffith)

- 5. Louisiana Story (Flaherty)

- 7. Greed (von Stroheim)

- 7. Le Jour se lève (Carné)

- 7. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 10. Brief Encounter (Lean)

- 10. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

1962

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 3. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 4. Greed (von Stroheim)

- 4. Ugetsu Monogatari (Mizoguchi)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. Bicycle Thieves (De Sica)

- 7. Ivan the Terrible (Eisenstein)

- 9. La terra trema (Visconti)

- 10. L’Atalante (Vigo)

1972

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 4. 8½ (Fellini)

- 5. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 5. Persona (Bergman)

- 7. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 8. The General (Keaton)

- 8. The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles)

- 10. Ugetsu Monogatari (Mizoguchi)

- 10. Wild Strawberries (Bergman)

1982

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Règle du jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Seven Samurai (Kurosawa)

- 3. Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly, Donen)

- 5. 8½ (Fellini)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. L’avventura (Antonioni)

- 7. The Magnificent Ambersons (Welles)

- 7. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 10. The General (Keaton)

- 10. The Searchers (Ford)

1992

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. La Regle du Jeu (Renoir)

- 3. Tokyo Story (Ozu)

- 4. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 5. The Searchers (Ford)

- 6. L’Atalante (Vigo)

- 6. The Passion of Joan of Arc (Dreyer)

- 6. Pather Panchali (Ray)

- 6. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 10. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick)

2002

- 1. Citizen Kane (Welles)

- 2. Vertigo (Hitchcock)

- 3. La Regle du Jeu (Renoir)

- 4. The Godfather, parts I and II (Coppola)

- 5. Tokyo Story (Ozu)

- 6. 2001: A Space Odyssey (Kubrick)

- 7. Battleship Potemkin (Eisenstein)

- 7. Sunrise (Murnau)

- 9. 8 ½ (Fellini)

- 10. Singin’ in the Rain (Kelly and Donen)

There is much that could be said about these lists. Most readers will probably be astonished to see Bicycle Thieves at the head of the first list, with Kane not even present. Brief Encounter above La Regle du jeu. Louisiana Story, of all things, and Le Jour se léve. By 1962, tastes had changed. Italians won the day, with three films, while Eisenstein, whose Ivan the Terrible, Part 2 had finally been released in 1957, had two films chosen. Two French films and two American. But it was in this year that Kane appeared, immediately bouncing to number one, a position from which it has never budged. I suspect it will sit atop the 2012 list, simply because now so many critics assume it’s the best film ever–and even if they don’t assume that, they won’t be able to agree on an alternative.

Ford has had only one film on the lists, The Searchers, in 1982 and 1992. For a time it was the Ford film du jour, until in 1992 Hitchcock zipped past it with Vertigo, which settled into the second spot after Kane in 2002. Mizoguchi has been on only one list, in 1972 with Ugetsu Monogatari. Ozu’s first film to became well known in the west didn’t make the list until decades later, in 1992, and yet despite the discovery of Late Spring and Early Summer and An Autumn Afternoon, Tokyo Story remains the Ozu film. Tati has never appeared on the list. Neither has Bresson. I’ll buy the idea that critics are out there voting for Bresson like mad, but all for different films. But Play Time, surely one of the very greatest films ever made, should be easy to converge around. Finally, the only post-1970 film on here (and not by much) is the Godfather pair. I was still working on my master’s degree when the first one came out.

I suppose by now, with so many smaller countries starting to make movies and so many festivals making them widely available, it becomes impossible to anoint new classics in the way critics used to. Kiarostami’s Koker Trilogy, in whole or in part, would seem to be such a classic, but there are so many great competing films. Does one have enough perspective to choose more recent films when others, like Sunrise, have stood the test of time? Play Time is 45 years old now, and I think it’s a greater film than most of those on the 2002 list–certainly including the number one. Possibly it will make the list this year.

Why is Kane so fixed at the top, when other films move up and down and ladder, and some appear and disappear? Perhaps the simple assumption that if it has been up there so long, it must really be the greatest film ever made.

I think this business of polls and lists for the greatest films of all times would be much more interesting if each film could only appear once. Having gained the honor of being on the list, each title could be retired, and a whole new set concocted ten years later. The point of such lists, if there is one, is presumably to introduce people who are interested in good films to new ones they may not have seen or even known about.

Such an approach is not wholly unthinkable. Each year the National Film Registry maintained by the Library of Congress chooses 25 films deemed to be national treasures worthy of special priority in preservation. There’s probably some assumption that the best films were on the early lists and that each new 25, especially coming annually rather than at longer intervals, must be of less interest than its predecessors. But on the whole it’s a pretty egalitarian exercise, one that treats all kinds of films as fair game, not just fiction features, and it really does draw attention to obscure films that deserve to be better known. Given how many films have been made in the USA, it will be a long time before the Registry is scraping the bottom of the cinematic barrel. The entire world could supply so many more.

At any rate, I don’t insist that justice will not be done until How Green or some comparable Ford masterpiece appears on Sight & Sound‘s poll, any more than I would say that it’s having won the Best Picture Oscar proves that it’s a great film. I think we all know that the whims of the Academy members are hard to fathom, then and perhaps even more so now. But why call it overrated just because it beat Kane for that dubious honor? If anything, How Green is underrated for that very reason. Had it been made in a different year and won the Oscar against some other films that weren’t Kane, would it be any better or worse?

If you have never seen How Green and are not wholly opposed to earned sentimentality, give it a try. Just make sure you have at least three hankies handy.

PS March 8, 2012. Our friend Antti Alanen points out that Maureen O’Hara said the shot with the veil was carefully planned. She disagrees with Philip Dunne’s claim that the wind catching it was a happy accident, as Joseph McBride recounts in Searching for John Ford:

Dunne thought Ford had “one of the greatest strokes of luck a director ever had” when the wedding veil suddenly caught a gust of wind and billowed behind Mareen O’Hara as she walked down the steps from the church. O’Hara recalled, “Everybody said, ‘Oh, that Ford luck! How wonderful that was! What an effect it has!’ Rubbish! It wasn’t ‘Ford luck.’ It was three wind machines placed by John Ford, and I had to walk up and down those steps many times while he worked out that the wind machine would do exactly that.” As she climbs into the carriage, the ator playing her husband, Marten Lamont, reaches out to catch her veil. Dunne thought, “The man shouldn’t have touched it when the veil spiraled up. My God, what a shot! Luckily, Joe LaShelle, who was the operator, just gave it a little tilt with the camera.” I told Dunne I thought the gesture of restraining the veil (probably planned by Ford, like the rest of this meticulously composed shot) is an eloquent metaphor for the repressiveness of Angharad’s loveless marriage. “Well, I guess so,” the screenwriter responded. “I didn’t think beyond that. I said, ‘My God, you get a break like that, you leave it alone.'” (p. 332)

PPS March 11, 2012. Thanks to Przemek Kantyka for pointing out that Ugetsu actually figured on the 1962 and 1972 lists.

Pandora’s digital box: From films to files

“Up ahead was Pandora. You grew up hearing about it, but I never figured I’d be going there.”

DB here:

Actually it wasn’t originally a box but a jug. And it might not have been filled with all the world’s misfortunes; it might have housed all the virtues. In Greek mythology, the gods create her as the first woman, sort of the ancient Eve. We get our standard idea of her story not from the ancient world, however, but from Erasmus. In 1508 he wrote of her as the most favored maiden, granted beauty, intelligence, and eloquence. Hence one interpretation of her name: “all-gifted.” But to Prometheus she brought a box carrying, Erasmus said, “every kind of calamity.” Prometheus’ brother Epimetheus accepted the box, and either he or Pandora opened it, “so that all the evils flew out.” All that remained inside was Hope. (Don’t think there isn’t a lot of dispute about why hope was cooped up with all those evils.)

The idea of Pandora’s box spread throughout Western culture to denote any imprudent unleashing of a multitude of unhappy consequences. It’s long been associated with an image of an attractive but destructive woman, and we don’t lack examples in films from Pabst to Lewin. But there’s another interpretation of the maiden’s name: not “all-gifted” but “all-giver.” According to this line, Pandora is a kind of earth goddess. In one Greek text she is called “the earth, because she bestows all things necessary for life.”

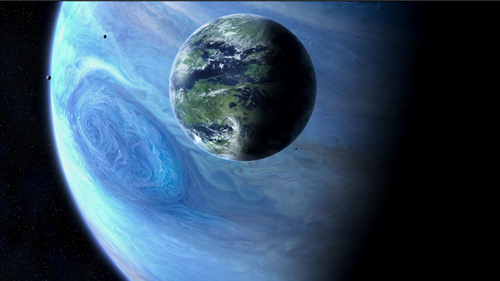

The less-known interpretation seems to dominate in Avatar. Pandora, a moon of the huge planet Polyphemus, is a lush ecosystem in which the humanoid Na’vi live in harmony with the vegetation and the lower animals they tame or hunt. Nourished by a massive tree (they are the ultimate tree-huggers), they have a balanced tribal-clan economy. Their spiritual harmony is encapsulated in the beautiful huntress Neytiri. As the mate for the first Sky-Person-turned-Na’vi, Avatar Jake, she’s also an interplanetary Eve. And by joining the Na’vi on Pandora, Jake does find hope.

The irony of a super-sophisticated technology carrying a modern man to a primal state goes back at least as far as Wells’ Time Machine. But the motif has a special punch in the context of the Great Digital Changeover. Digital projection promises to carry the essence of cinema to us: the movie freed from its material confines. Dirty, scratched, and faded film coiled onto warped reels, varying unpredictably from show to show (new dust, new splices) is now shucked off like a husk. Now images and sounds supposedly bloom in all their purity. The movie emerges butterfly-like, leaving the marks of dirty machines and human toil behind. As Jake returns to Eden, so does cinema.

Avatar or atavism?

Kristin suggested the title for this series of blog entries, and I liked its punning side. For one thing, Avatar was a turning point in digital projection. 3D, as we now know, was the Trojan Horse that gave exhibitors a rationale to convert to digital. Avatar, an overwhelming merger of digital filmmaking (halfway between cartoon and live-action) and 3D digital projection, fulfilled the promise of the mid-2000s hits that had hinted at the rewards of this format.

With its record $2.7 billion worldwide box office, Avatar convinced exhibitors that digital and 3D could be huge moneymakers. In 2009, about 16,000 theatres worldwide were digital; in 2010, after Avatar, the number jumped to 36,000. True, theatre chains also benefited from JP Morgan’s timely infusion of about half a billion dollars in financing in November 2009, a month before the film’s release. Still, this movie that criticized technology’s war on nature accelerated the appearance of a new technology.

Throughout this series, I’ve tried to bring historical analysis to bear on the nature of the change. I’ve also tried not to prejudge what I found, and I’ve presented things as neutrally as I could. But I find it hard to deny that the digital changeover has hurt many things I care about.

The more obvious side of my title’s pun was to suggest that digital projection released a lot of problems, which I’ve traced in earlier entries. From multiplexes to art houses, from festivals to archives, the new technical standards and business policies threaten film culture as we’ve known it. Hollywood distribution companies have gained more power, local exhibitors have lost some control, and the range of films that find theatrical screening is likely to shrink. Movies, whether made on film or digital platforms, have fewer chances of surviving for future viewers. In our transition from packaged-media technology to pay-for-service technology, parts of our film heritage that are already peripheral—current foreign-language films, experimental cinema, topical and personal documentaries, classic cinema that can’t be packaged as an Event—may move even further to the margins.

Moreover, as many as eight thousand of America’s forty thousand screens may close. Their owners will not be able to afford the conversion to digital. Creative destruction, some will call it, playing down the intangible assets that community cinemas offer. But there’s also the obsolescence issue. Equipment installed today and paid for tomorrow may well turn moribund the day after tomorrow. Only the permanently well-funded can keep up with the digital churn. Perhaps unit prices will fall, or satellite and internet transmission will streamline things, but those too will cost money. In any event, there’s no reason to think that the major distributors and the internet service providers will be feeling generous to small venues.

Did this Pandora’s box leave any reason to be optimistic? I haven’t any tidy conclusions to offer. Some criticisms of digital projection seem to me mistaken, just as some praise of it seems to me hype or wishful thinking. In surrendering argument to scattered observations, this final entry in our series is just a series of notes on my thinking right now.

What you mean, celluloid?

First, let’s go fussbudget. It’s not digital projection vs. celluloid projection. 35mm motion picture release prints haven’t had a celluloid base for about fifteen years. Release prints are on mylar, a polyester-based medium.

Mylar was originally used for audio tape and other plastic products. For release prints of movies, it’s thinner than acetate but it’s a lot tougher. If it gets jammed up in a projector, it’s more likely to break the equipment than be torn up. It’s also more heat-resistant, and so able to take the intensity of the Xenon lamps that became common in multiplexes. (Many changes in projection technology were driven by the rise of multiplexes, which demanded that one operator, or even unskilled staff, could handle several screens.)

Projectionists sometimes complain that mylar images aren’t as good as acetate ones. In the 1940s and 1950s, they complained about acetate too, saying that nitrate was sharper and easier to focus. In the 2000s they complained about digital intermediates too. Mostly, I tend to trust projectionists’ complaints.

But acetate-based film stock is still used in shooting films, so I suppose digital vs. celluloid captures the difference if you’re talking about production. Even then, though, there’s a more radical difference. A strip of film stock creates a tangible thing, which exists like other objects in our world. “Digital,” at first referring to another sort of thing (images and sounds on tape or disk), now refers to a non-thing, an abstract configuration of ones and zeroes existing in that intangible entity we call, for simple analogy, a file.

George Dyson: “A Pixar movie is just a very large number, sitting idle on a disc.”

Big and gregarious

Sometimes discussion of the digital revolution gets entangled in irrelevant worries.

First pseudo-worry: “Movies should be seen BIG.” True, scale matters a lot. But (a) many people sit too far back to enjoy the big picture; and (b) in many theatres, 35mm film is projected on a very small screen. Conversely, nothing prevents digital projection from being big, especially once 4K becomes common. Indeed, one thing that delayed the finalizing of a standard was the insistence that so-called 1.3K wasn’t good enough for big-screen theatrical presentation. (At least in Europe and North America: 1.3K took hold in China, India, and elsewhere, as well as on smaller or more specialized screens here.)

Second pseudo-worry: “Movies are a social experience.” For some (not me), the communal experience is valuable. But nothing prevents digital screenings from being rapturous spiritual transfigurations or frenzied bacchanals. More likely, they will be just the sort of communal experiences they are now, with the usual chatting, texting, horseplay, etc.

Of course, image quality and the historical sources and consequences of digital projection are something else again.

Irresolution

It’s a good thing the pros kept pushing. Had filmmakers and cinephiles welcomed the earliest digital systems, we might have something worse. Here’s George Lucas in 2005, talking less about photographic quality than the idea of the sanitary image.

The quality [of digital projection] is so much better. . . . You don’t get weave, you don’t get scratchy prints, you don’t get faded prints, you don’t get tears. . . The technology is definitely there and we projected it. I think it is very hard to tell a film that is projected digitally from a film that is projected on film.

And he’s referring to the 1280-line format in which Star Wars Episode I was projected in 1999.

Probably the widespread skepticism from directors and cinematographers helped push the standard to 2K. (So did the adoption of the Digital Intermediate.) Optimistic observers in the mid-2000s expected the major studios to make 4K the standard right away. Given the constraints of storage at that time, the 2K decision might be justified. But like the 24 frames-per-second frame rate of sound cinema, it was a concession to the just-good-enough camp.

At the same time, George seems to grant that progress will be needed in the area of resolution.

You’ve got to think of this [our current situation] as the movie business in 1901. Go back and look at the films made in 1901, and say, “Gee, they had a long way to go in terms of resolution. . . .”

Actually, in films preserved in good state from 1901, the resolution looks just fine—better than most of what we see at the multiplex today, on film or on digital.

The invisible revolution

Speaking of sound cinema: Is the changeover to talkies the best analogy for what we’re seeing now? Mostly yes, because of the sweeping nature of the transformation. No technological development since 1930 has demanded such a top-to-bottom overhaul of theatres. Assuming a modest $75,000 cost for upgrading a single auditorium, the digital conversion of US screens has cost $1.5 billion.

In an important respect, though, the analogy to sound doesn’t hold good. When people went to talkies, they knew that something new had been added. The same thing happened with color and widescreen. And surely many customers noticed multi-track sound systems. But what moviegoers notice that a theatre is digital rather than analog? Many probably assume that movies come on DVDs or, as one ordinary viewer put it to me, “film tapes.” Anyhow, why should they care?

There was a debate during the 2000s that audiences would pay more for a ticket to a digital screen. But that notion was abandoned. People aren’t that easy to sucker. So we’re back with 3D as the killer app, the justification for an upcharge. Whether 3D survives, dominates, or vanishes isn’t really the point. It’s served its purpose as the wedge into digital installation.

By the way, according to one industry leader, 2D ticket prices are likely to go up this year while 3D prices drop. Is this flattening of the price differential a strategy to get more people to support a fading format?

Mommy, when a pixel dies, does it go to heaven?

Digital was sold to the creative community in part by claiming that at last the filmmaker’s vision would be respected. Every screening would present the film in all its purity, just as the director, cinematographer et al. wanted it to be seen.

Last week I went to see Chronicle with my pal Jim Healy. The projector wasn’t perpendicular to the screen, so there was noticeable keystoning. The masking was set wrong, blocking off about a seventh of the picture area. And two little pink pixels were glowing in the middle of the northwest quadrant throughout the movie. I’m assuming that Chronicle’s director didn’t mandate these variants on his “vision.”

Jim went out to notify the staff, and two cadets came down to fiddle with the masking. The movie had already been playing in that house for several days. Maybe the masking hadn’t been changed for months? And of course the projector couldn’t be realigned on the fly. As for those pixels: There’s nothing to be done except buy a new piece of gear. Chapin Cutler of Boston Light & Sound tells me that replacing the projector’s light engine runs around $12,000. At that price, there may be a lot of dead pixels hanging around a theatre near you.

Video to the max

Not so long ago, the difference was pitched as film versus video. That was the era of movies like The Celebration and Chuck and Buck. Then came high-definition video, which was still video but looking somewhat better (though not like film). But somehow, as if by magic, very-high-definition video, with some ability to mimic photochemical imagery, became digital cinema, or simply digital.

We have to follow that usage if we want to pinpoint what we’re talking about at this point in history. But damn it, let’s remember: We are still talking about video.

The Film Look

Ever since the days of “film vs. video,” we’ve been talking about the “film look.” What is it?

I’m far from offering a good definition. There are many film looks. You have orthochromatic and panchromatic black-and-white, nitrate vs. acetate vs. mylar, two-color and three-color Technicolor, Eastman vs. Fuji, and so on. But let’s stick just with projection. Is there a general quality of film projection that differentiates it from digital displays?

Some argue that flicker and the slight weaving of film in the projector are characteristic of the medium. Others point to qualities specific to photochemistry. Film has a greater color range than digital: billions of color shades rather than millions. Resolution is also different, although there’s a lot of disagreement about how different. A 35mm color negative film is said to approximate about 7000 lines of resolution, but by the time a color print is made, the display yields about 5000 lines—still a bit ahead of 4K digital. But each format has some blind spots. There’s a story that the 70mm camera negative of The Sound of Music recorded a wayward hair sticking straight out on the top of Julie Andrew’s head. It wasn’t visible in release prints of the day, but a 4K scan of the negative revealed it.

Film fans point to the characteristic film shimmer, the sense that even static objects have a little bit of life to them. Roger Ebert writes:

Film carries more color and tone gradations than the eye can perceive. It has characteristics such as a nearly imperceptible jiggle that I suspect makes deep areas of my brain more active in interpreting it. Those characteristics somehow make the movie seem to be going on instead of simply existing.