Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

Il Cinema Ritrovato: More and more

Il Cinema Ritrovato Book Fair (photograph Margherita Caprilli).

Kristin here:

I mentioned in my entry on the African thread at this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato that I filled in blank spaces in my program with a miscellany of intriguing films. Here are some of those films I saw, and others that David saw.

O Pão (1959)

Manoel de Oliveira’s first film, the gorgeous black-and-white documentary short, Douro, Faina Fluvial, was released in 1931. His last, Um Século de Energia, another documentary short, came out in 2015, the year of his death aged 106 (as did Visita ou Memórias e Confissões, a deliberately posthumous legacy film shot in 1982). That’s an 84-year career. I doubt any other filmmaker can claim as much.

Initially that career proceeded in fits and starts. He made more documentary shorts in the 1930s and then a black-and-white feature, Aniki-Boko (1942), during the war under an authoritarian regime. After the war he could not find funding and decided to study color filmmaking in Germany. During the 1950s he applied his resulting expertise to two documentaries: O Pintor e a Cidad (“The Painter and the City,” 1956) and O Pão (Bread). A beautiful print of the latter was shown in this year’s Ritrovati e Restaurati thread. It was to be his last film before he turned to feature filmmaking, though he never entirely gave up documentaries, particularly near the end of his life.

This hour-long film slowly follows the entire progress of bread, from wheat-fields to milling to baking to consumption. The images, whether in field or factory, are lovely, showing that Oliveira had indeed learned a great deal about color.

There is no voice-over narration, even during a lengthy scene in a large mill where technicians perform mysterious tests on samples of flour. The slow progression creates a soothing, almost mesmeric tone. Only toward the end does some social criticism emerge. A hungry urchin stealthily retrieves a roll dropped by a shopper, only to have it snatched away by a little street thug. Clearly bread, despite the lyricism of its production, is not for everyone.

Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Avval, Ghazieh-e Shekl-e Duvvum (1979)

Another must-see was Abbas Kiarostami’s early film, First Case, Second Case, also presented in the rediscovered-and-restored thread. Like Oliveira, Kiarostami began in documentary work. This remarkable film was started before the 1979 Iranian Revolution and finished after it–and then banned.

The film’s beginning rather resembles other Kiarostami openings, with a simple scene in a classroom. A teacher drawing the anatomy of an ear on a blackboard is interrupted by a knocking noise caused by one of his students. No one confesses or reveals who caused the noise, and the teacher suspends seven of the boys, who spend the next days in the hall outside the classroom.

This scene is revealed to be a 16mm film being shown to a succession of teachers, government officials, religious leaders, and the fathers of some of the boys. In the latter cases, some variant of the framing above is shown, with an arrow pointing to the son of the father being interviewed. Unseen, Kiarostami asks them the same question: did the boys do right in refusing to reveal who disrupted the class? Some of these interviewees became key figure in the Islamic Revolution. (Jason Sanders’ program notes for a screening of the film provide some information about this historical context.)

This “documentary” has of course been carefully staged. A page from Kiarostami’s script reveals how he designed the passing days of the boys’ suspension, with different ones standing or sitting each time. The illustration is from Ritrovato programmer Ehsan Khoshbakht’s blog entry on the film, where he credits First Case, Second Case with introducing the interview technique into the director’s work.

This first case shows the boys maintaining their refusal to identify the culprit. In a new scene, the second case, an alternative outcome shows one of the boys naming the guilty classmate to his teacher. Again, Kiarostami interviews many of the same people as to whether they believe the boy’s decision can be morally justified.

If not as charming as some of Kiarostami’s later work, First Case, Second Case contains a familiar combination of complexity and simplicity, as well as a fascination with people telling their own versions of events.

The film has been picked up by Janus in the USA, which should mean that it becomes available from Criterion on Blu-ray and/or its streaming service, The Criterion Channel.

Twelve O’Clock High (1949)

In recent years, Il Cinema Ritrovato has featured the films of a major Hollywood director as one of its main threads. This year it was Henry King. I managed to miss nearly all of his films. In part I feared that, since the auteur du jour is always one of the the more popular items in the program, the screenings would be crowded. Word of mouth suggested that they were.

Still, I had an afternoon free, and I wanted to guarantee myself a good seat for Varda par Agnès, showing later in the day. I went to an earlier screening in the same theater, and I was glad I did. Twelve O’Clock High is an impressive and entertaining film, if not an outright masterpiece.

Fitting into David’s set of innovations typical of the 1940s, the action is enclosed by a framing situation. A man we eventually discover was an American officer posted in England during World War II bicycles out into the countryside and visits the derelict remains of the military airport where he served. (Above, played by Dean Jagger in a role that won him a best-supporting-actor Oscar).

For a long time the story concentrates on General Frank Savage (Gregory Peck), who takes over command of an underperforming bomber unit in the same air station we saw at the beginning. He proves an absolute stickler for discipline, initially alienating the pilots he commands. Eventually he wins their respect, of course, and he learns to unbend a bit.

Eventually a series of air battles occur, with some very impressive and genuine combat footage, including aerial views of bombs exploding on their German targets. The film was presented in a nearly pristine 35mm print, which certainly contributed to my pleasure at having ended up at that screening somewhat by chance.

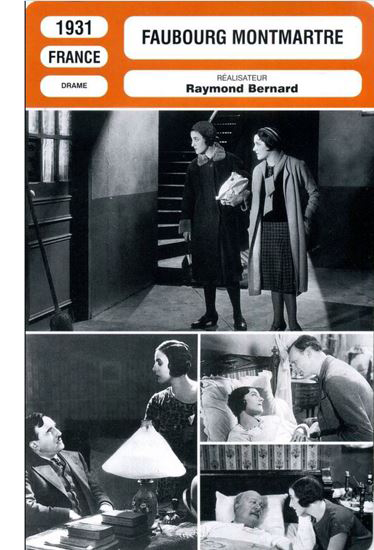

Faubourg Montmartre (1931)

I definitely planned from the start to see this film. I very much admire director Raymond Bernard’s 1932 World War I drama Wooden Crosses, his next feature after Faubourg Montmartre. Indeed, I had done a video on it for The Criterion Channel (“Observations on Film Art” #16 “The Darkness of War in Wooden Crosses“)

While a slighter film than Wooden Crosses, Faubourg Montmartre is quite stylish and technically impressive, considering that it was Bernard’s first sound film. In it he abandons his concentration during the silent era on historical epics (his best-known being The Miracle of the Wolves, from 1924).

Here he tackles a melodrama in a contemporary setting, centering around Ginette, a somewhat naive young working-class woman, played by popular star Gaby Morlay. She and her older sister Céline live and work in the titular district of Paris, the disreputable area of cheap entertainment and brothels. Céline works as a prostitute but tries to protect Ginette from such a life. Becoming more dependent on drugs, however, she nearly dupes Ginette into following her into prostitution.

Despite its grim setting, the film has many light moments, mostly provided by the amiable Morlay. It also contains some impressive musical numbers, one a variety number by Florelle and a café song about prostitution by Odette Barencey.

The film was yet another in the festival’s Ritrovati and Restaurati thread.

Georges Franju

There was an unaccustomed focus on documentaries this year, which presumably was the occasion for devoting a small thread to Franju. Of the thirteen shorts which he made or at least is tentatively credited with (most of them commissioned documentaries), eleven were shown. Judex, his fiction feature paying homage to the serial of the same name by Louis Feuillade, was also on the program.

I tried to see all the Franju shorts, since only Le Sang des bêtes (above) and Hôtel des Invalides are well-known in the US. The prints shown ranged widely in quality, some being in 35mm and some 16mm. En passant par la Lorraine was almost unwatchable, though most of the rest were in varying degrees acceptable.

The most interesting revelations were perhaps Mon chien (1955), a melancholy narrative based on the common habit of people abandoning their pets in the countryside. The amazingly callous parents of the little heroine dump her beloved German shepherd in the woods on their way to a vacation spot. The film follows the faithful animal’s trek home, only to find a locked house and a dog-catcher waiting. An empty cage signals that the animal was euthanized, with the voiceover of the girl calling forlornly for her pet. The other was Les poussières (1954), a lyrical survey of many kinds of dust generated in the world, ending in a strong anti-pollution message.

It was a pleasure to see this body of work brought together, but the screenings also demonstrate the pressing need to restore many of these films.

A Gabin tribute

DB here (with films I saw in boldface):

Jean Gabin has become emblematic of French cinema from the 1930s and after, so the several films devoted to him were welcome. Programmer Edward Waintrop included the classic Pépé le Moko (1936) but correctly assumed he didn’t have to show this crowd La Grande Illusion (1937), La Bête Humaine (1938), and Le Jour se Lève (1939). Edward’s catalog entry wisely emphasized how much Gabin owed to Julien Duvivier, an underrated director who helped the young actor find starring roles.

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

From the heroic thirties, we got the less-seen but still fabled Cœur de Lilas (1931), in which a detective disguises himself as a workman and plunges into the underworld to investigate a murder. The chief suspect, Lilas, is protected by the surly Gabin.

In her book on popular song in French cinema, our colleague Kelley Conway has written a superb analysis of Cœur de Lilas, and you can find a clip of Gabin’s big musical number here. Director Anatole Litvak handles his performance in a long tracking shot that keeps our attention fastened on Gabin’s half-scornful, half-boastful mug as he spits out lines about his girlfriend’s bedroom calisthenics (“The rubber kid. . . She dislocates you”).

Gabin plays the third point of a love triangle in Cœur de Lilas, but he’s somewhat more central to the lesser-known Du Haut en Bas (1933), a sort of network narrative that reminds us that The Crime of M. Lange (1936) isn’t the only film tracing the tangled passions in a courtyard community. More easygoing here but still a force to be reckoned with, Gabin plays a footballer with his eye on an aspiring teacher forced to work as a maid. Other plotlines, including Michel Simon’s raffish wooing of his landlady, intermingle in this thoroughly agreeable movie by the great G. W. Pabst.

A generous sampling of Gabin’s later career included La Marie du Port (1949), Le Plaisir (1951), Maigret tend un piège (1957), and the brutal Simenon adaptation Le Chat (1970), the first film I saw on my first visit to Paris. En Cas de Malheur (1957), an efficient plunge into sex and crime by Autant-Lara, features Gabin as a prestigious but dodgy lawyer drawn to the pouting self-regard of Brigitte Bardot. In youth and age, as a sort of French Spencer Tracy, Gabin could exude both relaxed joie de vivre and stolid menace. An icon, as we say.

Americana, urban and rural

State Fair (1933).

Speaking of Spencer Tracy, it was a pleasure to see this Milwaukee native in a long-neglected racketeer drama. Quick Millions (released May 1931) arrived in the middle of the first big gangster cycle and was overshadowed by two Warners hits, Little Caesar (January 1931) and The Public Enemy (May 1931). As part of Dave Kehr’s welcome second Fox cycle, Quick Millions had its own pungent force.

It traces the familiar trajectory of a working stiff, trucker “Bugs” Raymond, who claws his way to the top of the mob. Thanks to blackmail and crooked labor maneuvers (“The brain is a muscle,” he tells his moll), he winds up triggering a spate of gangland killings that eventually swallows him up.

Quick Millions was noticed as one of the earliest films to find a smart tempo for talkies, one that relies less on long speeches than snappy scenes delivering one point apiece. The passage of time is signaled by changing license plates, and the ending is a shrug, shoving Bugs’ death offscreen and giving him none of the tragic flourishes of Little Rico or Tom Powers. For almost every scene, the little-known director Roland Brown finds an unexpected twist in visuals or performance . Who else would film a sidling George Raft jazz dance from a high angle and then supply inserts of his legs, from behind no less?

Fox found more success with a folksy Grand Hotel variant based on the popular novel State Fair (1932). Henry King’s 1933 film was planned as an “all-star” vehicle, and it did boast Will Rogers, Janet Gaynor, and Lew Ayres. An Iowa family heads to the fair, aiming for blue ribbons in pickle preserving and hog-fattening. The son has a surprisingly carnal affair with a trapeze artist, while the daughter meets a roguish reporter who makes her rethink her engagement to a hick back home. State Fair‘s script gives the plot a happier ending than the book did, but that’s not necessarily a problem; we want these kind souls to enjoy a bit of glory.

Henry King became famous for rustic realism with Tol’able David (1921), a model for Soviet filmmakers, and Ehsan Khoshbakht’s King retrospective reminded us that he worked this vein a long time. From 1915 Twin Kiddies (a Marie Osborne vehicle) to Wait ‘Till the Sun Shines, Nellie (1952), this loyal Fox craftsman showed himself, like Clarence Brown at MGM, an adaptable director with an unpretentious gift for celebrating small-town life.

Still more, more…

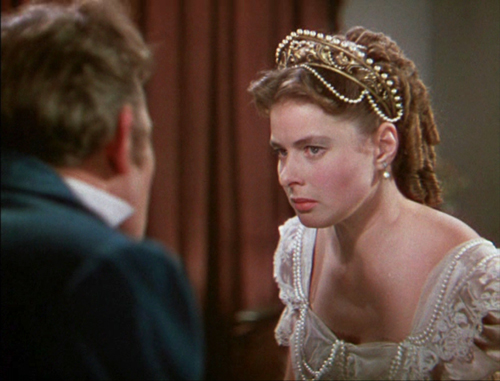

Under Capricorn (1949).

I could go on about other films, such as Zigomar: Peau d’Anguille (“Zigomar, the Eelskin,” 1912), Victorin Jasset’s forerunner of Feuillade’s delirious master-criminal sagas. (In one episode, an elephant’s trunk fastidiously picks the lock on a circus wagon and drags away a strongbox.) Our next entry will spend a little time looking at a neat Genina film from 1919. In the meantime, I’ll sign off by mentioning two other high points.

The pretty Academy IB-Tech print of Under Capricorn (1949) made me like the film quite a bit better than previous viewings. As ever, one high point was La Bergman’s virtuoso soliloquy admitting her guilt. Any other director of the time would have reenacted the crime in a flashback, but, in the shadow of Rope (1948), Hitchcock makes her squeeze out her confession in a ravishing single-take monologue running almost eight minutes.

Its power comes partly from the fact that the framing withholds the facial response of the man who loves her. He’s slowly understanding the depth of her devotion to her husband during penal servitude. “How did you live all those years?” he murmurs. How’d you think? Her glance flicks over him, in both guilt and defiance (above).

Finally, no film gave me more pure pleasure than the restoration of Boetticher’s Ride Lonesome (1959). Sony archivist Grover Crisp explained that the original prints had all been made from the camera negative (!) and so he had no internegatives or fine-grain masters to work from. Nevertheless, this digital version, made in 4K with wetgate scanning, looked superb.

I tend to judge Boetticher westerns by the strength of the villains, meaning that Seven Men from Now (Lee Marvin) and The Tall T (Richard Boone) sit at the top of my heap, but it’s hard to resist the laconic dialogue Burt Kennedy supplied everybody in Ride Lonesome. And the antagonists facing Randolph Scott here–Lee Van Cleef (brief but unforgettable), Pernell Roberts (the good-bad rascal), and sweet-natured dimwit James Coburn (on his way to rangy knife-wielding in The Magnificent Seven)–add up pretty powerfully. Against them stands Scott as vengeance-driven Brigade, an unyielding chunk of sweating mahogany.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Mariann Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator. Thanks also to Dave Kehr, Grover Crisp, Mike Pogorzelski, and Geoffrey O’Brien for talk about many of the classics on display.

The entire Ritrovato ’19 catalogue, with full credits and essays, is online here. There are also videos of many events, including master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Quick Millions was remembered several years after its release for “the rapid rhythm of its continuity.” See Janet Graves, “Joining Sight and Sound,” The New York Times (29 November 1936), X4.

John Bailey’s introduction to Under Capricorn included a revealing short explaining the Technicolor dye-transfer process. For further information there’s the remarkable George Eastman House Technicolor research site and of course James Layton and David Pierce’s superb book The Dawn of Technicolor.

Kristin discusses Kiarostami’s landscape techniques in a Criterion Channel Observations entry. In American Dharma, discussed by David here, Errol Morris reveals that Twelve O’Clock High was an inspiration for Steve Bannon’s political career.

The Ritrovato program notes credit Fréhal as the working-class singer in Faubourg Monmartre, but Kelley Conway’s Chanteuse in the City: The Realist Singer in French Film (linked above) identifies her as Odette Barencey, a lesser-known chanteuse of the period who resembled Fréhal.

Opening shot of Ride Lonesome (1959).

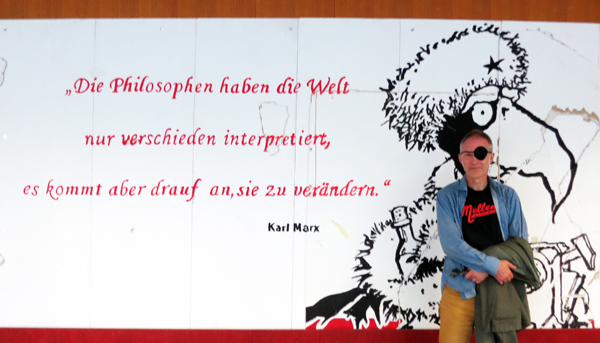

Cognitive film studies: The Hamburg Variations

Lobby, Von-Melle-Park 9, Universität Hamburg, with Murray Smith.

DB here:

How many universities in the US would post a big quotation from Karl Marx in the lobby of a classroom building? (Answer: None.) But a cartoonish rendition of Marx’s killer app–the task of philosophy being not only to understand the world but also to change it–greeted the one hundred or so scholars attending the latest conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image last week at the Universität Hamburg.

How much we’ll change the world remains to be seen. What is clear now is that thanks to the superb organization of Kathrin Fahlenbach, Maike S. Reinerth, and their team, the SCSMI had a lively four days of papers, discussions, and excursions–as well as a screening of a strong film by a skillful director previously unknown to me. In all, every good reason to go to a conference.

Big questions, candidate answers

Carl Plantinga, Dirk Eitzen, and Kathrin Fahlenbach on the Hamburg Harbor cruise.

The range was huge, as usual, because this is a very diverse group. Our community, as I’ve mentioned in earlier reports, hosts film scholars, scholars of other media (television, games, internet), psychologists, and philosophers. Recurring questions include: How do viewers comprehend media presentations? What is the role of morality in film and television? How do practitioners conceive their craft? How do media present and trigger emotions? What appeals are specific to certain genres or historical periods? Not least: How may we construct good theories to answer such questions?

Three sessions ran simultaneously at each time slot, so I missed many good presentations. Kristin and I occasionally doubled up. Many of the talks will eventually become published papers, several in the Society’s journal Projections, so let me just highlight a few strands.

For those of us interested in how style interacts with narrative, there were several significant presentations. James Cutting, who has pioneered the use of Big Data techniques in scanning large batches of films, provided a compact account of how “sequences” (as opposed to scenes) displayed patterns of coherence and grouping. Karen Pearlman discussed her films, and James examined them to reveal fractal patterns in their rhythms–patterns that match the dynamics of footsteps, heartbeats, and breathing.

Two papers added to our understanding of the Kuleshov effect, much discussed on this site. Marta Calbi and her collaborators conducted EEG testing on spectators exposed to a Kuleshovian film scene, while Anna Kolesnikov, another member of the team, traced the contradictory versions of the “experiments” that Kuleshov and his students purportedly constructed. Both were exciting contributions to our understanding of Kuleshov’s legacy, which as the years go by looks more complex than we had thought.

Other papers on visual style included Barbara Flückiger’s tour of the staggering resource she and her colleagues have devoted to the history of color in film–a database of images from 400 films illustrating a range of technologies, periods, and genres. She has also mounted a magnificent array of tools for detailed analysis of color. (Significantly, she has taken the images from film prints, not video copies.) Here’s one of several stunning images she has taken from Helmut Käutner’s Grosse Freiheit Nr. 7 (1944, Agfa nitrate).

Stephen Prince, whose book Digital Cinema has just been published, surveyed the emergence of “deep fakes,” manipulated images that have no basis in reality but which are indiscernible from an accurate image. Steve was once skeptical that digital images would ever cut us off entirely from photographic reality, but now machine learning has managed to do it. Sped up by social media, the rise of unverifiable “records” creates what he called “an attack on an information system we call society.”

Hitchcock, everybody’s idea of a shrewd filmmaker (when will cognitivists discover Lang?), came in for his usual close treatment. Todd Berliner proposed five ways in which story information can be set up and paid off in a narrative, and he used Psycho as an instance of at least four of those methods. Maria Belodubrovskaya countered Hitchcock’s constant claim that he relied on suspense and not surprise. She showed that both single sequences and overall plots (e.g., Suspicion, Psycho) were heavily dependent on surprise effects.

In the first day, the range of the “humanistic” side of SCSMI was on vivid display. Malcolm Turvey asked whether the give and take of philosophers’ arguments converged on a consensus about truth, the way that much of science progresses. To illustrate the process, he considered the return of an “illusion” theory of images put forth by Robert Hopkins. Later that day, Jeff Smith used the cognitive theory of confirmation bias to show how characters in Spike Lee’s Clockers systematically misunderstand the story situation. The result, enhanced by genre conventions and a violation of some traditions of the detective story, enmeshes the viewer in the same error.

On the other end of the spectrum, there were papers mobilizing empirical research. Timothy Justus drew upon Lisa Feldman’s work in How Emotions Are Made to suggest that a biocultural account of facial expression should not rely too strongly on Paul Ekman’s classic argument about universal, basic expressions. More room, Justus proposed, should be given to cultural forces that build “emotion concepts” that filmmakers and viewers draw on.

A more hands-on empirical project was that coming from a team at Aarhus university. Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen posed the question: What if sympathy for a film’s villain varies with the personality of the spectator? As he put it, “If you are like a villain, will you like a villain?” So via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk the team ran questionnaires testing how personality types matched tastes in villains. Not to spoil their public announcement, I’ll just say that the results seem to confirm the belief that the most dangerous creatures on earth are young human males.

There was a lot more here than I can report, including provocative keynote addresses from Professors Anne Bartsch and Cornelia Müller (presenting work done with Hermann Kappelhoff). There was also a moving tribute to Torben Grodal, a central force in SCSMI and a leading-edge theorist applying evolutionary psychology and embodiment theory to traditional genre studies.

And, since SCSMI wants to understand how creators create, there was a film and its maker.

Without bullshit

In the past, our conferences have featured Lars von Trier and Béla Tarr, talking with us about their work. This time the guest was Thomas Arslan, a prominent “Berlin-school” director, who brought his 2010 film In the Shadows (Im Schatten) to the lovely Cinema Metropolis.

The film is a dry, hard-edged crime exercise. Trojan, fresh out of prison, comes to his boss to claim his share of the loot. In a tense confrontation he manages to get some of what he’s owed, but he’s now a target for elimination. He searches for a new robbery scheme and settles on the heist of an armored car. As usual, things don’t go as planned, particularly due to the intervention of a crooked cop.

Shot in a laconic style, In the Shadows took advantage of the Red One camera to produce remarkable depth in dark surroundings. (We saw it as a print because in 2010 theatres weren’t quite ready to show digital files. The print looked fine.) The drab locations complemented the anti-psychological impact of the story. Characters barely speak, the music is spare and almost subliminal, and the framing doesn’t accentuate the action expressively. In his post-film discussion, Arslan explained that the style grew out of the small budget and the rapid schedule. The result was a sort of modern B-film, avoiding the excess of CinemaScope and explosive chase sequences.

Arslan refuses to glamorize his gangsters, but he summons up sympathy for Trojan by minimal means. The protagonist is a solid, efficient professional, and he’s loyal to his boss until he realizes he’ll be betrayed. And as Hollywood screenwriters would remind us, you can sympathize with someone who’s been treated unfairly. I liked the unfussy handling of the story; it was a bit reminiscent of Rudolf Thome’s bare-bones Detective (1968). Arslan would be a good director to shoot a Richard Stark noir. “He does it without bullshit,” Arslan said of his thieving protagonist. It’s a good description of Arslan’s own technique.

SCSMI continues its tradition of merging humanistic inquiry with findings from empirical science. We can fruitfully ask questions that cut across traditional boundaries if we ground those questions in clear concepts and solid evidence. Our gathering next year moves back to the States–Grand Rapids, no less. More fun on the way.

Go here for earlier years’ coverage of SCSMI conferences.

On Richard Stark noir novels, see here and here. In the Shadows would fit nicely into my discussion of conventions of the heist film.

My own SCSMI contributions were two: a tribute to Torben Grodal and a little talk on contemporary women’s domestic thrillers (Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, etc.). I may post the latter as a video lecture later this summer.

James Cutting lecturing at the SCSMI conference.

REINVENTING HOLLYWOOD in paperback: Welcome to the Variorum

Happy Death Day (2017).

DB here:

Reinventing Hollywood: How 1940s Filmmakers Changed Movie Storytelling came out about eighteen months ago in hardcover. Amazon and other sellers have been offering it at robust discounts. Now there’s a paperback, priced at $30, though that could also be discounted. I hope all these options put it within the range of readers interested in the period, in Hollywood generally, and in the history of storytelling in commercial cinema.

But of course time doesn’t stand still. Since I turned in the manuscript around Labor Day 2016 I’ve encountered some intriguing things that were more or less relevant to my research questions. (I’ve also found a few errors, most of them corrected in the paperback edition. Meet me in the codicil if you’re curious.) In this blog entry and some followups, I’ll discuss some films, books, and DVD releases that came out after I finished the book. They don’t force me to change my case, I think, but they’re things I wish I could have cited, if only in endnotes.

The first entry in this series is here.

Seeing Happy Death Day 2U reminded me of one of the central arguments of Reinventing. But before I get to that, let me talk about English drama of the years 1660-1710. No, really.

500 plays and more

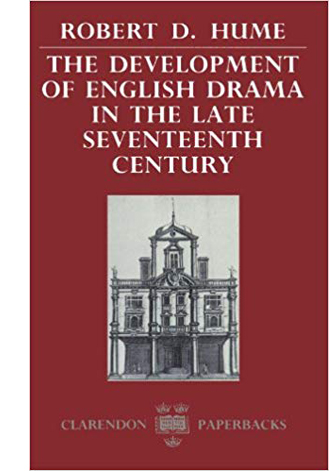

In the late 1960s a young scholar named Robert D. Hume became curious about Restoration drama. Going beyond the canon, he started reading minor works, eventually discovering a collection of microform cards that included virtually all English plays between 1500 and 1800. The set cost about 10% of his pre-tax annual salary, and he struggled to read the bad reproductions of 17th century printing. Still, the effort revealed something important. “All the modern criticism was so radically selective that the critics had no grasp at all of what was really being performed in the theatre.”

In the late 1960s a young scholar named Robert D. Hume became curious about Restoration drama. Going beyond the canon, he started reading minor works, eventually discovering a collection of microform cards that included virtually all English plays between 1500 and 1800. The set cost about 10% of his pre-tax annual salary, and he struggled to read the bad reproductions of 17th century printing. Still, the effort revealed something important. “All the modern criticism was so radically selective that the critics had no grasp at all of what was really being performed in the theatre.”

Hume’s method was simple and drastic. He read all of the preserved plays publicly performed in London between 1660 and 1710. Along with revivals, pageants, translations, and adaptations, there were about five hundred “new” plays, and these he concentrated on. They included famous ones like Marriage à la Mode and The Way of the World, as well as many obscure pieces.

The result was The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century (Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1976). Its first part surveys the conventions and formulas found in subgenres of comic and serious drama (sentimental romance, horror tragedy, and many others). In the second part Rob traces the development of these types across the period.

From the standpoint of my research I was fascinated to see that Rob reveals a teeming set of variations on generic schemas. Characters, situations, and plot twists are mixed and matched. A plot based on romance leading to marriage commonly shows the couple outwitting blocking characters. Sometimes, though, the man must win the woman over. Or she must conquer him. Similarly, when extramarital seduction drives the action, a man may pursue a woman but

occasionally an amorous, often older woman is the pursuer (She wou’d if she cou’d; The Amorous Widow) or an ineffectual male, usually a henpecked husband, is a comic pursuer (Sir Oliver Cockwood in She wou’d).

In Planet Hong Kong I called this tendency of mass entertainment a “variorum” one, by analogy with editions that print all the versions of a major text.

Once a genre gains prominence, a host of possibilities opens up. Horror filmmakers are likely to float the possibility of demonic children, if only because the competition has already shown demonic teenagers, rednecks, cars, and pets. Similarly, once the male-cop genre is going strong, someone is likely to explore the possibility of a tough woman cop.

You might object that using the term “variorum” is just a fancy way to talk about the mechanical formulas of mass entertainment. But by putting the emphasis on variety within familiarity, the label points up the need for constant innovation, great or small. Fans of film genres readily recognize this churn, but what I began to realize is that it’s common as well in both folk narratives and more “industrialized” ones, like theatre and popular literature.

Monuments of scholarship like Hume’s Development remind us that the variorum principle is a primary engine of popular entertainment. The urge for novelty puts pressure on artists to try to fill every niche in the ecosystem, sometimes forcing competitors to strain for far-fetched possibilities. The wild treatment of noir conventions in Serenity is a recent example.

Beyond genre: Style and narrative

Cover Girl (1944).

Some time in the 1990s I began to realize that a lot of my research applies the variorum principle to domains outside genre. For instance, Figures Traced in Light and the last chapter of On the History of Film Style look at cinematic staging from this standpoint, showing how basic principles of staging got realized in many ways across film history. I applied the variorum principle to particular narrative techniques in some essays in Poetics of Cinema, considering the options of forking-path plots and network narratives.

Reinventing tries to trace a wide range of storytelling options as they consolidated in the 1940s. Rob Hume could study every preserved play, but I couldn’t do that for films. I managed to watch about 600. (Later entries in this blog series will mention some I missed.) Not surprisingly, I found the variorum principle at work in the narrative techniques on display.

I set out a couple of prototypes for the most common plots: the single-protagonist one (Five Graves to Cairo) and the plot based on a romantic couple (Cover Girl). Beyond those, I considered less common plot options, such as multiple protagonists and network narratives. Then I went on to consider narrational strategies that cut across all types. What strategies were available for mounting flashbacks, or expressing subjective states? In effect, I tried to reconstruct Forties Hollywood’s storytelling menu, largely independent of genre.

Another way to put this is that I was tracking norms. But the variorum principle shows that a norm isn’t just a mandate: Do this. Any normative practice is a cluster of stronger and weaker options.

These options lead to a cascade of further (normative) choices. Shoot a dialogue scene in a two-shot and you’ll need to adjust performances for viewer pickup. Shoot using a lot of close-ups and you’ll need to cut among your actors more frequently to keep everybody “in the scene”–that is, salient for the audience.

Choose a flashback and you’re forced to decide how far back to start it, what to include that’s relevant to the present action, and how to remind the audience of action that preceded the flashback. Of course you may also choose to try to make viewers forget, because you’ve misled them. That’s what happens in Mildred Pierce and Pulp Fiction.

Usually we find the variorum principle working among several films. What if creators put the principle to work within a single film?

The first day of the rest of your life

Every now and then filmmakers try out forking-path narratives. These plots, I suggest in this essay, trace out alternative futures for their characters. Blind Chance and Run Lola Run are prototypes, though there are plenty of examples earlier and later.

Sometimes the protagonist is dimly aware of the options. The protagonists of Blind Chance and Run Lola run seem to learn from their mistakes in the parallel lines of action. This can yield “multiple draft” narratives in which later story lines show characters struggling to achieve the best revision of circumstances they can.

I’d distinguish plots like these from Groundhog Day, which presents not alternative futures but identical replays of a specific time period. What makes each iteration different is that Phil, realizing he’s living the same day over and over, struggles to behave differently. This pattern has come to be called a time-loop narrative.

The time-loop and forking-path patterns usually provide only changes in the story-world elements of each track. Phil’s changing his routines takes place against a background of recurring situations. Similarly, the protagonist of Source Code gets to try out different ways to stop a train bomber.

What, though, if a looped or forking-path movie tried to survey several alternative genre conventions? That would give us a sense that the variorum idea has been swallowed up within a single film.

This happens, I think, in Happy Death Day. By now it’s not a spoiler to indicate that this slasher movie borrows the Groundhog Day premise and loops a single day in the life of mean girl Tree Gelbman. Each day she’s killed by a stalker in a babyface mask. Each time she dies, she awakes in the bed of Carter Davis, who brought her to his dorm room (without sexytime) to recover from a night of partying. As the days repeat, Tree becomes more desperate to avoid her fate and tries a variety of stratagems. They fail, until they don’t. In the course of them Tree learns to become a nicer person.

What’s interesting to me is that several variorum alternatives of the slasher genre are squeezed into this one film. The stalker kills Tree in a shadowy underpass, in a bedroom during a frat party, in her sorority bedroom, under a friend’s window, on a campus trail, and after chasing her through a hospital, a parking ramp, and a highway. She’s knifed, bludgeoned, hanged, run over, and stabbed with a broken bong.

Of course the shooting-gallery premise of slasher films often generates a string of variations across the film. Boyfriends, girlfriends, figures of authority, and passersby are dispatched by Jason or Freddie Krueger in ever more exotic ways. But in Happy Death Day, the sense of genre replay is heightened by Tree’s being the sole target of the ten variant homicides (one of which is a forced suicide). It’s as if we were watching a performer auditioning for screen tests in which she might be cast as one victim or another. But here the victim is always the Final Girl.

The comedy that haunts many slasher films is enhanced by the preposterous premise that Tree will survive. The deaths become vivid as replays by virtue of their tongue-in-cheek humor, as each slaying tries to outdo the earlier ones and as Tree sarcastically comments on her fate.

With the time-loop convention put into place by Groundhog Day, our interest goes beyond changes in the story world and concentrates more on narrative structure. We watch for scenes we’ve already seen, expecting them to be revised in surprising ways. The handling of the replays foregrounds film technique as well, as when in Happy Death Day Tree’s frantic walk across the quad after a late reset is rendered in distorted imagery reflecting her confusion. We register this as a variant on her earlier stride down the same route–hung-over, but not yet desperate.

One virtue of such repetitions for low-budget cinema is that the variant passages can be shot quite economically. You can save time on location by reusing camera setups, with the actors altering their performance, or their costumes and makeup. In the DVD bonus material, director Christopher Landon talks of following this production strategy. Why does low-budget cinema explore odd narrative options? They can come cheap.

Variants times 2 or 3

Happy Death Day 2U (2019).

A film series often self-consciously varies the story world that the continuing characters confront. In the studio era, Charlie Chan went to the circus and the opera, Mr. Moto got involved in a prizefight scheme, and Ma and Pa Kettle visited Waikiki. Today’s superhero franchises rely on fully-furnished, constantly changing story worlds. Back to the Future, though, launched a series that did more than present a story world that shifted from film to film. The trilogy self-consciously reorganized its plot structure and narration, with replays and alternative outcomes enabled by a time-travel premise. We’re expected to appreciate the altered replays as part of the film’s experience.

The sequel Happy Death Day 2U has just been released in that Dead Zone in which low-end American genre cinema flourishes. I have a lot to say about it, but it’s probably too soon. Still, it’s no spoiler to indicate that it offers a set of variants on the givens of the first film. For one thing, what caused the time loop of the original is now explained. The birthday motif gets elaborated via Tree’s backstory, with strong doses of sentiment. And suspects who were eliminated in the initial film step forward as plausible culprits in this one.

Just as important, there’s an added structural premise that gives the new entry an acknowledged affinity with Back to the Future II and other forking-path tales. To top things off, the second installment supplies a revised version of the outcome of the first one.

Although the sequel isn’t thriving at the box office, perhaps there will be a third entry.

I have the third movie and I have already pitched it to Blumhouse. Everybody is ready to go again if this movie does well. I keep shifting the tone, genre a little bit. The third movie I know is going to be a little different. It’s going to be really bonkers and really fun.

Bonkers or not, having another version would show that the Variorum never sleeps.

Two last points. First, a film I discussed last time, Confession (1937), internalizes the variorum impulse in a milder way, by replaying a key scene from a different character’s viewpoint. More unusually, Confession is a remarkably close remake of a German film, Mazurka, and thus constitutes a homegrown variation on the original.

Secondly, why study the variorum principle? Hume points out:

To insist on analyzing the famous writers and plays in isolation is a mistake: much may be learned by viewing them as they originally appeared–variably successful in the midst of a prolific, unstable, and rapidly changing theatre world.

So one argument is that we can best understand and appreciate masterful filmmaking against the background of normal practice. That seems right to me, but I think there are other good reasons to ask these questions.

For one thing, through bulk viewing of a lot of films, you may discover accomplished works. Many well-regarded films have gained their renown through accidents of release and critical reception. (His Girl Friday is one such.) Good films lurk in many crevices of film history.

I also think that the norms are of interest in themselves. They can show that craft practices harbor more variety than we sometimes think. Studying norms can also reveal offbeat possibilities that are sketched for future development. In Reinventing, I sometimes point to films, either obscure or awkwardly constructed or both, which anticipate trends to come. One example would be the strange, time-shifting exercise Repeat Performance (1947). It’s a Forties counterpart to Dangerous Corner (1934), a two-path plot looking toward more elaborate forking-path storytelling. It shows as well that rather unusual options can float around the edges of the variorum.

My quotations from Rob Hume come from correspondence and The Development of English Drama in the Late Seventeenth Century, pp. ix and 129. Thanks to Rob for sharing the backstory of the book’s composition. Readers interested in his method can learn much more about it in his later study Reconstructing Contexts: The Aims and Principles of Archaeo-Historicism (Oxford, 1999).

This entry relies on a distinction among a film’s story world, its plot structure, and its narration. The idea is explained in this essay and applied to a single film in a blog entry on The Wolf of Wall Street. Plots with loops and forking paths are connected with the idea that “form is the new content” in films from the 1990s and after. I try to chart that ecosystem in The Way Hollywood Tells It: Story and Style in Modern Movies. See also this entry for a quick summary of early examples of multiple-draft plotting. For more on the virtues of Charlie Chan and Mr. Moto, go here.

The following errors in the hardcover version of Reinventing Hollywood are corrected in the paperback.

p. 9: 12 lines from bottom: “had became” should be “had become”. Oops.

p. 93: Last sentence of second full paragraph: “The Killers (1956)” should be “The Killing (1956)”. Arrgh. Elsewhere on this site I discuss Kubrick’s heist film at some length.

p. 169: last two lines of second full paragraph: Weekend at the Waldorf should be Week-End at the Waldorf.

p. 334: first sentence of third full paragraph: “over two hours” should be “about one hundred minutes.” Doggone.

We couldn’t correct this slip, though: p. 524: two endnotes, nos. 30 and 33 citing “New Trend in the Horror Pix” should cite it as “New Trend in Horror Pix.”

Whenever I find goofs like these, I take comfort in this remark by Stephen Sondheim:

Having spent decades of proofing both music and lyrics, I now surrender to the inevitability that no matter how many times you reread what you’ve written, you fail to spot all the typos and oversights.

Sondheim adds, a little snidely, “As do your editors,” but that’s a bridge too far for me. Instead I thank the blameless Rodney Powell, Melinda Kennedy, Kelly Finefrock-Creed, Maggie Hivnor-Labarbera, and Garrett P. Kiely at the University of Chicago Press for all their help in shepherding Reinventing Hollywood into print.

Happy Death Day (2017).

Vancouver 2018: Crime waves

Burning (2018).

DB:

It’s striking how many stories depend on crimes. Genre movies do, of course, but so do art films (The Conformist, Blow-Up) and many of those in between (Run Lola Run, Memento, Nocturnal Animals). The crime might be in the future (as in heist films ), the ongoing present (many thrillers), or the distant past (dramas revealing buried family secrets).

Crime yields narrative dividends. It permits storytellers to probe unusual psychological states and complex moral choices (as in novels like Crime and Punishment, The Stranger). You can build curiosity about past transgressions, suspense about whether a crime will be revealed, and surprise when bad deeds surface. Crime has an affinity with another appeal: mystery. Not all mysteries involve crimes (e.g., perhaps The Turn of the Screw), and not all crime stories depend on mystery (e.g., many gangster movies). Still, crime laced with mystery creates a powerful brew, as Dickens, Wilkie Collins, John le Carré, and detective writers have shown.

We ought, then, to expect that a film festival will offer a panorama of criminal activity. Venice did last year and this, and so did the latest edition of the Vancouver International Film Festival. Some movies were straightforward thrillers, some introduced crime obliquely. In one the question of whether a crime was committed at all led–yes–to a full-fledged murder.

Smells like teen spirit

Diary of My Mind.

Start with the package of four Swiss TV episodes from the series Shock Wave. Produced by Lionel Baier, these dramas were based on real cases–some fairly distant, others more recent, all involving teenagers. The episodes offer an anthology of options on how to trace the progress of a crime.

In Sirius a rural cult prepares for a mass suicide in expectation they’ll be resurrected on an extraterrestrial realm. The film focuses largely on Hugo, a teenager turned over to the cult by his parents. Director Frédéric Mermoud gives the group’s suicide preparations a solemnity that contrasts sharply with the food-fight that they indulge in the night before. Similarly, The Valley presents a tense account of a young car thief pursued by the police. Locking us to his consciousness and a linear time scheme, director Jean-Stéphane Bron summons up a good deal of suspense around the boy’s prospects of survival in increasingly unfriendly mountain terrain.

Sirius and The Valley give us straightforward chronology, but First Name Mathieu, Baier’s directorial contribution, offers something else. A serial killer is raping and murdering young men, but one of his victims, Mathieu, manages to escape. The film’s narration is split. Mathieu struggles to readjust to life at home and at school, while the police try to coax a firm identification from him. This action is punctuated by flashback glimpses of the traumatic crime. The result explores the parents’ uncertainty about how restore the routines of normal life, the police inspector’s unwillingness to press Mathieu too hard, and the boy’s self-consciousness and guilt as the target of the town’s morbid curiosity.

This insistence on the aftereffects of a crime dominates Diary of My Mind, Ursula Meier’s contribution to the series. This too uses flashbacks, mostly to the moments right after a high-school boy kills his mother and father. But there’s no whodunit factor; we know that Ben is guilty. The question is why. Ben’s diary seems to offer a decisive clue (“I must kill them”), but just as important, the magistrate thinks, is his creative writing under the tutelage of Madame Fontanel, played by the axiomatic Fanny Ardent. Because she encouraged her students to expose their authentic feelings, Ben’s hatred of his father had surfaced in his classroom work. Perfectly normal for a young man, she assures the magistrate. No, he asserts: a warning you ignored. The shock waves that engulf onlookers after a crime, the suggestion that art can be both therapeutic and dangerous, the question of a teacher’s duty to both her pupils and the society outside the classroom–Diary of My Mind raises these and other themes in a compact, engaging tale.

Last hurrah of (movie) chivalry

Chinese director Jia Zhangke is no stranger to criminal matters. His films have dwelt on street hustles, botched bank robberies, and hoodlums at many ranks. Ash Is Purest White is a gangster saga, tracing how a tough woman, Qiao, survives across the years 2001-2018. Initially the mistress of boss Bin, Qiao rescues him from a violent beatdown using his pistol. She takes the blame for owning a firearm. Getting out of prison, Qiao tracks down the now-weakened Bin, who has taken up with another woman.

Ash Is Purest White tackles a familiar schema, the fall of a gang leader, from the unusual perspective of the woman beside him, who turns out to be stronger than he is. Most of the film is filtered through her experience, and along with her we learn of Bin’s decline and betrayal, along with his integration into the corrupt and bureaucratic capitalism of twenty-first century China. The second half of the film shows Qiao forced to survive outside the gang’s milieu. A funny scene plays out one of her scams: picking a prosperous man at random, she announces that her sister, implicitly his mistress, is pregnant. Just as important, Qiao’s adventures allow Jia to survey current mainland fads and follies, including belief in UFO visits.

Among those follies, Bin suggests, is a trust in mass-media images. As Ozu’s crime films (Walk Cheerfully, Dragnet Girl) suggested that 1930s Japanese street punks imitated Warner Bros. gangsters, so Jia’s mainland hoods model themselves on the romantic heroes of Hong Kong cinema. They raptly watch videos of Tragic Hero (1987) and cavort to the sound of Sally Yeh’s mournful theme from The Killer (1989). They derive their sense of the jianghu--that landscape of mountains and rivers that was the backdrop of ancient chivalry–not from lore or even martial-arts novels but from the violent underworld shown on TV screens.

Bin’s decline is portrayed as abandoning those ideals of righteousness and self-sacrifice flamboyantly dramatized in the movies. But Qiao clings to the imaginary jianghu to the end. She explains to him that everything she did was for their old code, but as for him: “You’re no longer in the jianghu. You wouldn’t understand.” You can respect his pragmatism and admire her tenacity, but he’s still a feeble figure, and she’s left running a seedy mahjongg joint–one much less glamorous than the club she swanned through at the film’s start. Appropriately for someone who got her idea of heroism from videos, we last see her as a speckled figure on a CCTV monitor.

From dailiness to darkness

Burning.

Often the crime in question is presented explicitly, but two films leave it to us to imagine what shadowy doings could have led to what we see. In Manta Ray, by Phuttiphong “Pom” Aroonpheng, we get the familiar motif of swapped identity. A Thai fisherman finds a wounded man in the forest and nurses him back to health. The victim is a mute Rohinga whom the fisherman names Thongchai. They share a home and the occasional dance and swim, even a DIY disco.

But who attacked Thongchai in the forest, and why? And what is the connection to the unearthly gunman who paces through the forest, bedecked in pulsating Christmas bulbs? And what makes the foliage teem with gems glowing in the murk? Somewhere, there has been a crime.

Manta Ray accumulates its impact gradually, with the scenes of the men’s routines giving way to mystery when the fisherman vanishes and Thongchai (named by the fisherman for a Thai pop singer) is trailed by a ninja-like figure clad in a red cagoule. A disappearance and a reappearance (of the fisherman’s wife) punctuate moody scenes of trees and sea. The opacity of the action makes a political point: offscreen, Thais brutally hunt down the refugee Rohingas. But the critique of anti-immigrant brutality is intensified by the lustrous cinematography (Aroonpheng was a top DP). You can feel the texture of the planks in the cabin and the sharp edges of the gems that fingers root out of the forest floor. This is probably the most tactile movie I saw at VIFF.

Then there was Lee Chang-dong’s Burning. Lee started his career strong and has stayed that way. The slowly paced, Kitanoesque gangster story Green Fish (1997) and Peppermint Candy (1999), with its reverse-order chronology, both achieved local popularity and established him as a fixture on the festival circuit. Oasis (2002), a daring romance of a disabled couple, won a special prize at Venice. Secret Sunshine (2007) brought Lee even more widespread fame. Like the episodes of Shock Waves, it dealt with the aftereffects of a horrific crime. Virtually everyone I know who saw the film remembers most vividly a particular scene: the heroine, having converted to Christianity and at last ready to forgive the perpetrator, visits him in prison. It’s one of the most nakedly blasphemous scenes I’ve ever seen, carried off with a shocking calm. Crime–this time, a gang rape–is also at the center of Poetry (2010), with another mother facing familial tragedy.

Most of these plots, particularly Poetry, are rather busy, but Burning is more stripped down (though not short). Lee Dong-su maintains the shabby family farm while his father is in jail awaiting trial. In town Dong-su meets Haemi, a former classmate now running sidewalk giveaways.

She lures him into her life by asking him to feed her cat while she’s in Africa, but before she leaves they start an affair. But he seldom breaks into a smile, favoring a puckered-lip passivity. After their coupling, we get his POV on a blank wall.

This turns out to be the first of many disquieting passages. Between bouts of tending livestock, feeding Haemi’s cat, and masturbating to her picture, Dong-su gets mysterious phone calls with no one on the line. He meets Haemi at the airport only to discover that she’s formed a friendship (or more?) with the suave Ben, whose gentle courtesy makes Dong-su feel an even bigger bumpkin. Soon the three are hanging out together, but at parties Dong-su can only stare at Ben’s yuppie friends. Dong-su, who wants to be a writer, is a fan of Faulkner, but Ben compares himself to the Great Gatsby.

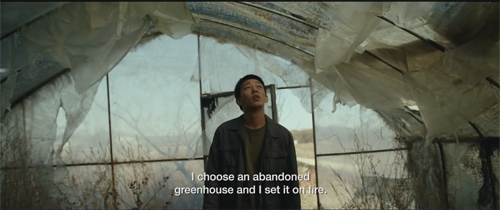

After a long night of relaxing at the farm, with the men watching Haemi dance topless, she disappears. A black frame, a dream of a burning greenhouse, and Dong-su is left alone halfway through the movie. What happened to Haemi? And why does Ben say he enjoys torching greenhouses? Dong-su turns detective,

Lee is a master of pacing, and the deliberateness of the film delicately turns a romantic drama into a critique of entitled lifestyles and then into a psychological thriller. We are locked to Dong-su’s consciousness except for a couple of telltale shots of Ben calmly studying his rival from afar. We get Vertigo-like sequences of Dong-su trailing Ben and probing for clues and perhaps having more dreams. At the same time, Dong-su starts writing, as if Haemi’s disappearance has inspired him, but he finds more violent ways to release his simmering bewilderment.

After only one viewing, I didn’t find Burning as devastating a film as Secret Sunshine or Poetry, but I’d gladly watch it again and probably I’d see more in it. Lee manages to sustain over two and a half hours a plot centering on three, then two principal characters. He has earned the right to soberly take us into the mundane rhythm of a loner’s life and then shatter that through an encounter with two enigmatic figures who may be playing mind games. As with Manta Ray, we have to infer some of the action behind the scenes, but that just shows that in cinema, classic or modern, crime can pay.

Thanks as ever to the tireless staff of the Vancouver International Film Festival, above all Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Shelly Kraicer, Maggie Lee, and Jenny Lee Craig for their help in our visit.

Snapshots of festival activities are on our Instagram page.

Japadog, a Vancouver landmark.