Archive for the 'Directors: Scorsese' Category

Dead man talking

Confidence (2003).

DB here:

“So I’m dead.”

At the start of Confidence we hear Jake Vig’s voice as we see him lying bloodied on a pavement. As the protagonist of a neo-noir, Jake recalls the classic start of Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (1950). There Joe Gillis (an echo of gigolo?), floating face-down in a swimming pool, begins to recount his stay as a kept man of faded film star Norma Desmond. That opening has become a touchstone for the grim fatalism of film noir, as well as a mark of daring screenwriting. The guy telling the story is dead! How cool is that?

Anybody interested in how films tell stories has to be interested in narrators, those figures—either mere voices or tangible characters—who recount, recall, or replay the story action. And anybody interested in Hollywood film knows that such narrators are hallmarks of a giddy period of cinematic innovation, as recognizably “1940s” as flashbacks, moody subjective sequences, and twisty plots. In that era we find narrators well outside that terrain known as noir. Romantic dramas, family sagas, comedies, Gothics, musicals, and other genres made ample use of voice-over commentary, and it didn’t always suggest a doom-laden atmosphere.

Still, dead narrators seem to be pushing things. They flout realism (How can a dead person tell anything?) and they raise problems of logic (To whom is this person speaking?). Is it a chatty corpse (Wilder originally wanted a morgue opening introducing Gillis) or an ethereal spirit divorced from the dead body?

Dead narrators turn up surprisingly often in the 1940s. During this period, as I’ve argued on this site and in the book I’m working on, many storytelling techniques we take for granted coalesced. There emerged a rough menu for handling them, and ambitious filmmakers played with several possibilities. That play didn’t stop in the Forties; we still have new versions of flashbacks, subjectivity, and the like. So let’s look at posthumous narrators in the Forties, with some glances at a trio of more recent efforts.

As a non-dead and highly reliable narrator, I must warn you of spoilers ahead.

Guiding spirits

The Human Comedy (1943).

Most simply, posthumous narration can be motivated as letters (Letter from an Unknown Woman) or diary entries (Thatcher’s journal in Citizen Kane). Similarly, Heaven Can Wait (1943) gives us a dead man explaining episodes from his life to an inquisitive official in the afterlife. The more flagrant cases, however, involve dead narrators who recount the entire film we see in voice-over, as in our prototype Sunset Boulevard. Knowing that the protagonist is dead at the start shifts our attention to how he or she will die.

Posthumous narrators go back a fair bit. In literature, Edgar Lee Masters’ Spoon River Anthology (1915) presents the ruminations of the town dead, in the manner of the cemetery climax of Our Town (1938 play, 1940 film). Wilfred Owen’s poetic monologue “Strange Meeting” (1918) presents soldiers reuniting in Hell, ending with the poignant line, “Let us sleep now….” Addie Bundren, the dead mother of Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying (1930), narrates portions of the novel from her coffin. In a pulpish pastiche of Faulkner, Kenneth Fearing’s mystery novel Dagger of the Mind (1941) includes a chapter narrated by a man who’s been murdered. Radio drama also included voices from the beyond. Examples include “Ghost Ship” (1940), with a victim recounting his own murder, and Norman Corwin’s “Untitled” (1944), which reveals the narrator to be a dead soldier.

In film, World War II brings forth the prospect of dead servicemen returning to tell their tales. “I am Matthew Macauley,” says a face superimposed over imagery of radiant clouds. “I have been dead for two years. But so much of me is still living that I know now that the end is only the beginning.” This is indeed a beginning, of The Human Comedy (1943). Having died in the war, Matthew will guide us back to his hometown and his household’s daily routines.

Matthew’s voice-over goes on to introduce his family members, including son Marcus on duty in the army. After a scene in which a spectral Matthew joins his wife at her work, his voice discreetly retires. It recurs only twice before he and his now-dead soldier son faintly enter to watch the family welcome their new member, Marcus’s pal Toby.

“You see, Marcus, the ending is only the beginning.” Matthew’s address to us has become piece of fatherly advice.

The dead narrator of The Human Comedy never intervenes in the action on earth, but an all-seeing intelligence exercises more authority in The Seventh Cross (1944). Seven prisoners escape from a concentration camp, and Ernst Wallau’s narration launches the film. During the escape sequence he rapidly introduces each of his comrades.

Fairly soon all but one are captured and executed on crosses planted in the prison yard. The first man to be crucified is Wallau, our narrator. After he is killed, his voice-over continues: “I was dead. I could see.”

Wallau’s commentary chiefly follows his friend George Heisler, who manages to elude the Gestapo while the other escapees are found and killed. Wallau’s narration continues through the film, chronicling not only the fates of the other men but probing Heisler’s state of mind. Wallau tells us what Heisler is thinking, guides us into his memory, notes things that Heisler has forgotten, and even informs us what other characters will do in the future. Confronted with this numb, almost mute character, we need the continual commentary of Wallau to give access to his inner life.

Wallau is that rare voice-over narrator who flaunts his omniscience. Being dead, he has total access to our world and can witness anything happening there. Despite Wallau’s godlike power, in good Hollywood tradition his narration attaches itself chiefly to Heisler. But here that restriction reflects simply Wallau’s foreknowledge, signaled at the start, that only Heisler will survive. The question becomes: How?

The answer comes through Wallau’s goading Heisler to find faith in others. At the start, Heisler is close to despair, and his flight stems from sheer instinctual survival. At the film’s midpoint, all his comrades have been killed, and Wallau’s long-term escape plan has failed. Heisler can’t any longer mechanically follow his mentor’s instructions. He must forge a new goal, seize the initiative, and learn to trust people. He must learn what Wallau told him from the start: there remain traces of humanity in Germany.

As Heisler’s hopes grow and his network of allies expands, Wallau’s prodding voice-over subsides. It reappears near the end, at the moment Heisler realizes how much he owes others. Heisler speaks of his debts, and Wallau murmurs in antiphony the names of those who have helped him, including some Heisler has never met.

Now that Heisler has joined the struggle with full commitment, Wallau can vanish. “Goodbye, George Heisler. I can leave you now.”

Ghostly narrators like Wallau and Matthew Macauley call to mind the nosy angels and spooks of so many 40s films. Those have their counterparts in radio dramas like “Good Ghost” (1948) and the parodic mystery novel Dead to the World (1947), with a dead detective narrating his efforts to solve a case.

As usual, a lot depends on timing of information. If we learn that the narrator is dead at the start, as in the films just mentioned and in Scared to Death (1947), a certain amount of the action can seem foreordained. Alternatively, there can be a surprise. Radio plays, it seems, tended to reveal their dead narrators as a twist ending. With less fanfare, a film can simply seem to forget the opening commentary. The Gangster (1947) is initially narrated, without a frame situation, by the crooked protagonist. As a result, we expect him to survive. Yet he dies in the course of the action. The filmmakers faced a problem: To return to the narration at the end or not? To revive his voice-over might suggest that he endures in some supernatural realm. Instead, an impersonal external voice takes over to balance the opening.

With the convention of the dead narrator in place, a film could flirt with the possibility that the initial voice we hear has no living source. The opening credits of Woman in Hiding (1950) strongly suggest that a betrayed wife, racing down a hillside at night before crashing over an embankment into a river, has been killed. Her commentary rises up during a scene of the police dragging the river, and she seems to be mocking her husband from beyond the grave.

Is this a female variant of Joe Gillis’ voice-over? Watch the whole movie to find out.

In the same year as Woman in Hiding, Sunset Boulevard gave us another voice from the Beyond. If the film’s technique seems less original coming after a string of dead narrators, at least it can be credited with making the narrator the protagonist (unlike The Human Comedy and The Seventh Cross) and for using the device in a full-blown A picture (unlike Scared to Death and The Gangster).

In sum, the dead-narrator technique became a schema, a pattern which filmmakers could simply copy, as in Scared to Death, or tweak, as in the apparently dead narrator of Woman in Hiding. Wilder offered his own variant on the schema. We tend to remember his as the prime example, maybe even as the first one. But it often happens in the 1940s that the originality of a noteworthy film stems from a revision of a schema that was already in circulation, not only in film but in other media.

The weekend Laura died

Occasionally, the variety of options at the period sets up more dissonant relations. Laura (1944) is probably the most famous example.

Vera Caspary’s original book is divided principally into first-person blocks recounted by bon vivant Waldo Lydecker, detective Mark McPherson, and magazine editor Laura Hunt. Early versions of the screenplay attempted to capture multiple-viewpoint narration through flashbacks and voice-overs. What happened to this structure, however, reveals a process we’ll encounter elsewhere: fiddling with the film in post-production yielded some startling, perhaps unintended novelties.

Laura Hunt has apparently been murdered by a shotgun blast to the face. When the film starts, McPherson is calling on her mentor Waldo Lydecker, an effete columnist and radio commentator. McPherson lets Waldo accompany him on his inquiries before the two retire for a dinner at the restaurant Laura loved. There, via flashbacks and voice-overs, Lydecker recounts Laura’s rise to prominence. (In a scene cut from the final film, there’s an indication that Waldo’s tale is partly false—an early instance of a lying flashback.) The other characters’ flashbacks and voice-overs were abandoned in production, so the rest of the film is rendered objectively.

We later learn that the original victim was not Laura, which makes Laura either a new suspect or a target for the killer’s second try. At the climax, it’s revealed that Waldo is the culprit; he concealed the gun in an antique clock that he had given Laura. While his pre-recorded program is broadcast, he returns to her apartment and tries to kill her. Laura eludes him and as he wildly fires his gun, he is shot by McPherson’s team.

What makes the finale curious is the film’s framing device. The first scene starts with Waldo’s voice-over: “I shall never forget the weekend Laura died.”

This appears to cast the entire film as a flashback, starting with McPherson’s visit to Waldo. Within that flashback to the weekend, we have further flashbacks–that is, Waldo’s dinner-table explanations to McPherson. Such Russian-doll embedding is found elsewhere during the 1940s. At the end of the evening, when Waldo leaves, the camera lingers on McPherson and we become attached to him for nearly all that follows.

In screenplay drafts, this last shot would have initiated Mark’s voice-over narration, which would constitute a chunk parallel to Waldo’s. This is further evidence that Waldo’s string of flashbacks, including his opening voice-over, functions to write finis to “his” section of the film. But in the finished film, without McPherson’s voice-over block, Waldo’s initial voice-over hangs there, apparently framing the whole film. It would have been easy simply to cut that commentary and retain the opening camera movement revealing McPherson browsing among Waldo’s treasures, perhaps with some more nondiegetic music. Then Waldo’s offscreen admonition would bring in his voice for the first time. After this, Waldo’s later flashbacks and his voice-over narration would become neatly nested and perfectly conventional.

Clearly, decision-makers wanted to retain Waldo’s ripe commentary to open the film; it has expository value, and it introduces a very intriguing character. But we don’t hear that enveloping voice again, so for the rest of the film we might take Waldo’s remarks as akin to those that open Rebecca (1940) or Flamingo Road (1949). In these films and many others, a reminiscing character voice introduces the story action from an unspecified point in time and space. And the plot’s shift to McPherson’s activities seems to suggest that the whole opening stretch, including Waldo’s initial recounting, should be taken as a unit, “his” section of the film. So when Waldo is shot down and starts to die, we might have a situation like that of The Gangster, where the narrator is killed in the course of the action he introduced, and the film forgets what started it all.

Instead, Laura takes the option that The Gangster avoided: it brings back the dead man’s voice. After Waldo collapses, there’s a cut to McPherson and Laura leaving the frame. As the camera moves in on the shattered clock face, we hear, “Goodbye, Laura. Goodbye, my love.”

The line might be taken as Waldo’s dying words spoken offscreen, except that the line is miked far more closely than his speech earlier in the scene, when he’s actually closer to he camera. In its acoustic texture, this unsituated sign-off formally balances the unsituated opening. But it also raises the possibility that the dead Waldo has launched the whole story and now bids Laura farewell from that realm wherein defunct narrators dwell.

The opening does hint that something otherworldly is going on. A tart, suave voice wells up from sheer darkness, perhaps a noir equivalent to the sunny eternity from which Matthew Macauley speaks in The Human Comedy. Yet for a dead narrator, Waldo is either ill-informed or misleading. He speaks of “the weekend Laura died.” But if he lived through the events of the film, he knows that she did not die. Of course, his fib helps the film mislead us; the first half presupposes that Laura was the victim. If we remember that an unused scene was going to reveal that his flashback tales to McPherson contained lies, we may conclude that Waldo is as unreliable in death as he was in life.

Some of these inconsistencies apparently spring from late decisions in production. The original ending, as scripted and shot, lets Waldo survive. As he’s led off, he says, “Thank you for everything, my dear. . . You’re all I’ll be thinking of—till Time stands still—for me. Goodbye, Laura.” The speech is heard offscreen as the camera pans and holds on the clock.

Fox production head Darryl F. Zanuck was dissatisfied with many aspects of this conclusion and so a new version was filmed. In that version, Waldo is shot and dying. We see him speak the same lines, and only then does the camera pan to the clock. The release version, with Waldo’s simpler, closely miked farewell over the shot of the clock, was evidently decided on still later.

For what it’s worth, both the original shooting script and the revision distinguish between lines marked as “WALDO (narrating)” and “WALDO’s voice” for offscreen delivery. In neither version are Waldo’s dying lines marked as “narrating.” And in neither do we get an indication of the final camera movement that lets Laura and McPherson leave the shot in order to target the shattered clock face. Yet we do have a sonic texture in the last lines that is closer to a narrator’s voice.

In sum, while presenting a haunting conclusion—the clock was Waldo’s gift to Laura, and the shattered face recalls his first victim—the soundtrack firmly reminds us of the opening. Do we have a dead narrator? Some cues are there, but they’re sketchier than those in other films of the era. (For one thing, in those films, the narrator tells us he or she is dead.)

The unexplained return of Waldo’s voice, now gentle, has a surprising poignancy. Because of its loose ends, the final moments become more evocative, and more poetically enticing, than the tidy, explicit wrapup of Sunset Boulevard. In such ways, Laura’s final moments provide an eccentric revision of the dead-narrator schema. The result may have encouraged filmmakers who followed to risk inconsistency for the sake of powerful immediate effects.

In an earlier entry, I traced how studio pressures made the narration of Preston Sturges’ The Great Moment oddly off-balance. Evidently something like this happened with Laura. In the pressure to get a film finished and out the door, to retain striking bits that may ultimately not make sense when put together, Hollywood filmmakers can innovate by accident.

Dead men tell no tales

Auto Focus (2002).

Once the dead-narrator schema was available, Forties filmmakers were able to tweak it in various ways. And the changes didn’t end then. To see how the same process of schema and revision has continued, consider three much more recent examples.

Paul Schrader’s Auto Focus is a straightforward case. Bob Crane’s voice-over appears early in the film, though not at the very start, and recurs six times before the final scene. The brief comments punctuate Crane’s career decline and his descent into sex addiction. As happens with The Seventh Cross and other films using voice-over narrators, the second half employs the device less intensively than does the first. It’s as if in a film’s Development section we’re expected to be absorbed enough in the action not to need explanation, and we’re sufficiently primed to know what the important issues are.

When Crane’s head is bashed in by his companion in sexual buccaneering, we have a case comparable to The Gangster: the narrator doesn’t survive. Crane’s voice has been silent for 28 minutes, so we might assume that we’ve lost his voice-over. But it returns over his bloody body, recounting in an offhand way the aftermath of his death. His voice remains as perky as it has been early in the film, in both his commentary and his explanations to his wives. “I’m a normal guy,” he has insisted, and his bland wrapup shows him insouciantly unaware of the implications of living and dying as he did. He can’t condemn his killer. “He was a cool guy in his way. . . . Men gotta have fun.”

Martin Scorsese’s Casino (1995) reworks the dead-narrator schema in more complicated ways, in the process borrowing other 40s conventions. During that period, multiple-narrator films became quite common. Again we have a prototype—Citizen Kane (1941)—but again it wasn’t alone. Trial films featuring flashbacks that dramatize testimony had become fairly common in the 1930s, and a couple of detective films (e.g., Affairs of a Gentleman, 1934; Thru Different Eyes, 1942) used flashbacks to present different witnesses’ versions of events. It would become a staple of crime films like The Killers (1946). Julien Duvivier’s Lydia (1941) transposed the multiple-narrator technique to the melodrama, while The Affairs of Susan (1945) applied it to romantic comedy. Mankiewicz, who seems quite obsessed with the strategy, deployed it in A Letter to Three Wives (1949), All about Eve (1950), and The Barefoot Contessa (1954).

A less common 1940s convention is the replay—the passage that repeats a scene, usually in flashback and usually including information not shown in the first pass. The most famous example is Mildred Pierce (1945), which I’ve fretted at for years (in this entry and this video). We can find less crucial replays in, again, Kane (Susan’s opera debut) and in more obscure films like Beyond Glory (1948).

Casino draws on the replay and the multiple-narrator format and blends them with the dead-narrator one. The film innovates in a couple of striking ways. First, in 1940s multiple-narrator films, the individual narrations are presented in blocks; a solid chunk from one voice, another from another. True, we see some leakage in All about Eve, but basically the narrators’ tales are kept distinct. Scorsese and Nicholas Pileggi’s script for Casino hops between two principal narrators, Ace Rothstein (Robert de Niro) and Nicky Santoro (Joe Pesci).

Ace and Nicky’s voice-overs are mostly very brief, tagging a cascade of episodes tracing each man’s rise in Vegas, with equally fleeting flashbacks to their origins. The first twenty minutes toggles ten times between the two men’s clipped commentaries. This stretch constitutes a sort of training session, preparing us for the rapid switches in viewpoint that will dominate the film. Again, though, the voice-overs will subside for stretches in the middle, when the scenes become more fully developed. As a momentary, almost twitchy variant we get one extra voice-over—that of a go-between who, in a freeze frame, decides not to tell the mob boss about Nicky’s betrayal of Ace. Significantly, the film’s third major character, Ginger McKenna (Sharon Stone), is allotted no voice-overs.

So Scorsese and Pileggi have fractured the 1940s voice-over schema. But the to-and-fro commentaries I’ve mentioned come after an opening sequence that seems to announce that one of these wise guys is already dead. The first scene shows Ace being blasted out of his car by a bomb. A sprawling body, as if ejected from the explosion, floats through the opening credits. And Ace’s next voice-over launches the film’s cascade of flashbacks by saying they come from the period “before I got myself blown up.” We seem to be in the full-fledged presence of a dead narrator.

We are, but it’s not Ace. At the film’s climax, it will be Nicky who dies at the hands of his own crew. In replays of the car explosion, it’s revealed that Ace actually survived the blast. By 1995 Scorsese and Pileggi could revise the 1940s schema by splitting the narrators and misdirecting our expectations: the apparently living narrator is the one who will die.

What, finally, of Confidence? Jake’s admission that he’s dead fits snugly into the tradition we’re considering, especially since it’s a voice-over initiating a flashback. That flashback takes us to the moments before his execution at the hand of the triggerman Travis.

In those moments Jake explains how his team of grifters accidentally took money belonging to a gang boss and how they proposed to repay him with an even bigger con job. That central story action, itself peppered with backstory exposition, is interrupted by returns to the opening execution situation. Jake’s first voice-over, apparently addressed to us, is differentiated by sonic texture from his explanations to Travis, but when his voice leads us to the past, it has the same degree of auditory presence. In effect, it’s the same confusion of narrating levels that’s promoted in the first long stretch of Laura.

At the climax of Confidence, we see Jake shot not by Travis but by the moll Lily. Travis flees, and so does she. Now we’re back to the opening situation, and a replay of Jake’s opening line, “So, I’m dead.” He seems to sign off. But now more flashbacks reveal that Jake and Lily have staged her gunplay and that the whole scheme has been a very long con. The team reunites and goes off with their millions. Confidence has appealed to our knowledge of the dead-narrator convention to fake us out: the story action won’t end with his death because he’s stage-managed it.

Jake lied about being dead. But so did Ace when he referred to being “blown up.” So did Waldo, maybe. And so do those films that don’t signal that the protagonist has fallen into a dream or a reverie. Actually, narratives are incorrigibly deceptive and full of secrets. You can’t even trust dead guys.

As ever, we’re reminded that modern filmmakers inherit a vast tradition of narrative schemas. Those can be reiterated or revised in unpredictable ways. The tradition is kept alive and engaging, as long as novelty is balanced with familiarity, innovation with redundancy. (Let the narrators explain, throw in some replays,) The way Hollywoood tells it is always indebted to the ways Hollywood told it.

For more examples of dead narrators see the Wikipedia entry and TV Tropes. Long as they are, these lists tilt heavily toward contemporary examples, where posthumous narration seems very common. One reason I posted this entry was to acknowledge older instances of this convention.

Ray Collins was a well-known radio voice as well as a Welles Mercury player. As both Matthew Macauley and Wallau, he seems to have been the go-to man for reliable supernatural voice-over. He had a long Hollywood career, but most baby boomers remember him best as Lieutenant Tragg in the Perry Mason TV show.

I’m indebted to Neil Verma for information about the posthumous narrator in radio plays. Neil also mentions “The Hitch-Hiker” (1942), and these episodes of Quiet, Please: “Inquest” (1947), “In Memory of Bernadine” (1947), “Anonymous” (1948), and “I Always Marry Juliet” (1948). (Listen to any of these here.) Filmgoers probably encountered more dead narrators on radio than on film. Neil’s book, Theater of the Mind, is an excellent account of 1930s and 1940s radio narrative.

The shooting script of Laura is available here. The revised ending is included as well. See also the detailed comparison of the two endings by Despina Veneti at Preminger Noir. The first analysis of the different versions was, I believe, carried out by Jacques Lourcelles in “Laura: Scénario d’un scenario,” L’Avant-scène du cinéma no 211/212 (July-September 1978), 5-11. This publication includes a French-language transcript of the film as we have it, along with cut portions. A detailed account of Laura’s production is provided by Chris Fujiwara in The World and Its Double: The Life and Work of Otto Preminger (Faber and Faber, 2008), pp. 36-48. I’m grateful to Jeff Smith for his advice about the sonic texture of Waldo’s voice-over.

The narrational issues raised by Laura go beyond the deceased Waldo’s voice. In the film’s most famous scene, McPherson is becoming obsessed with the dead Laura and, after drinking heavily, he falls asleep in her apartment. The camera tracks slowly in on him as he drops off. There’s the noise of a door from offscreen, and Laura walks in. McPherson is astonished. Laura, released the same week as The Woman in the Window, might seem to be hinting that Laura has been revived in McPherson’s dream.

Kristin has traced the numerous dialogue motifs that reinforce this possibility. Yet most films of the 1940s mark a dream sequence very explicitly (e.g., wavy superimposed lines, dissonant music) or at the least with a dissolve and a close-up or track-in reinforcing the shift to subjectivity. Laura provides only two cues, the sleeping character and the track-in. But as Kristin indicates, these and other factors keep the dream option a possibility for a first-time viewer. See “Closure within a Dream? Point of View in Laura,” Breaking the Glass Armor: Neoformalist Film Analysis (Princeton University Press, 1988), 162-194. Kristin’s essay also offers a comprehensive discussion of the shifts in Waldo’s narration.

The presence of dead narrators would seem to pose a problem for those scholars who believe that in a movie every narrator must have a narratee on the same logical level. For these theorists, film narrators are part of a symmetrical system of communication among personified entities. Those entities are either embodied in the text (McPherson is Waldo’s narratee in the restaurant) or implicit in the very logic of narrative itself. No narrator without a narratee! According to this line of argument, there must be a narratee as dead as Waldo listening to his opening voice-over, but being very, very quiet.

In contrast, I’ve argued that films, and possibly all narratives, are freewheeling and illogical in their use of markers of communication. Films may mimic only parts of a communicative circuit in order to achieve specific effects. In provoking experiences in readers, films seem to me to rely on psychology, not ontology. I float this argument in this chapter of Poetics of Cinema. See also this blog entry.

Earlier entries have touches on the schema-and-revision dynamic of style and story in Hollywood. See for examples my discussion of 1913 films, a consideration of 1940s style, some remarks on walk and talk, a piece on high-school lipdubs, a discussion of replays, and the entry on Gone Girl. Searching “schema” will bring up more. A roundup of entries on peculiar 1940s narratives is here. I analyze narration in All about Eve here. For more on the debt of modern film to 1940s innovations, see The Way Hollywood Tells It.

Casino.

Cinematic storytelling: A podcast on narrative

The Wolf of Wall Street (2013).

DB here:

Michael Neelsen is a filmmaker and consultant based here in Madison. In a discussion on ReelFanatics Michael and I consider some ideas about cinematic storytelling. My allergies gave me some Clintonesque hoarseness, and there are some things I’d rephrase better if I were writing them down, but maybe you’ll find something of interest there.

A couple of blog entries are relevant to our conversation: one on The Wolf of Wall Street and another on American Hustle. The first of these links to a general analysis of film narrative originally published in Poetics of Cinema and available elsewhere on the site. Our discussion of suspense and surprise harks back to other entries too, in particular those about Hitchcock and the bomb under the table (here and here). In the podcast I mention the Godard film Adieu au langage as well because I was then working on this blog entry.

You can also visit Michael’s company site StoryFirst.

Thanks to Michael for an enjoyable discussion, and for sharing it via podcast.

Understanding film narrative: The trailer

The Wolf of Wall Street.

DB here:

At many points in The Wolf of Wall Street, we hear the voice of Jordan Belfort chronicling his exploits in building up a rapacious investment company. A few times he even addresses the camera.

What’s he doing? Well, he’s telling us a story, obviously. Stories are what many (not all) films present to us. But how, exactly, can we understand the storytelling process in film? What do the filmmakers do, and what do we do?

For my book Poetics of Cinema, I wrote a chapter called “Three Dimensions of Film Narrative.” This 2007 essay tries to come to grips with several questions. Some are pretty general. What makes a film a narrative? How does a narrative film shape our response? What roles do visual and auditory techniques play? What are the roles of emotional responses and broad cultural factors? How does characterization work in a movie?

Other questions are narrower. How revelatory is Hollywood’s three-act model of plot? How do we pick out a story’s protagonist? Do literary concepts like “narrator” and “implied author” apply to films?

Since the chapter is part of a larger book, some of these matters are dealt with at greater length in other chapters. Some are developed in other books, notably Narration in the Fiction Film, and elsewhere on this site. This essay was my attempt to boil down my thinking about filmic storytelling into one convenient, if sometimes sketchy, form.

Today I’m posting a corrected, slightly revised version of that chapter as a downloadable pdf file. Thanks to our web tsarina Meg Hamel, it has links as well. Students, teachers, researchers, and casual or ardent cinephiles: Make use of this as you like.

The essay is here.

This blog entry is a guide to the essay, or maybe just a trailer. As with a trailer, my use of The Wolf of Wall Street is illustrative; I’m not offering anything like a full analysis or even a review. And like most trailers, mine has spoilers.

The three dimensions I explore in the essay are narration, plot structure, and story world.

Dimension 1: Pushy narration

A film’s narration I take to be unfolding and organization of story information as the viewer encounters it, moment by moment. . (This is distinct from the term “voice-over narration,” like Jordan’s in The Wolf of Wall Street, though voice-over commentary is part of the overall narration.) Narration is designed to shape our itinerary through the film. It’s a complex array of cues that guide us in building up the story.

In The Wolf of Wall Street, the first dose of information we get is a TV commercial for the Stratton Oakmont investment company. We see busy, efficient brokers bent over their desks in a vast office as a lion paces the aisles. But then we get another view of the office, as partying staff prepare to launch a little man in a Velcro suit toward a target. The man is hurled, and one of the men who tosses him identifies himself as Jordan Belfort. We’re then launched into a sequence laying out Jordan’s lifestyle.

One thing this portion of the narration does is to peel back the staid, solid image of the brokering house and show the orgiastic self-indulgence behind it. What if Scorsese and his screenwriter Terrence Winter hadn’t included the commercial? Our sense of the contrast between public image and internal debauchery wouldn’t be so strong.

The quick scenes of Jordan’s lifestyle, driven by drugs, sex, and high living constitute a block of concentrated exposition. The narration could have introduced Jordan’s debauchery gradually through hints, but instead we’re told of it bluntly and swiftly. Jordan boasts that at age 26 he made nearly fifty million dollars a year. We’re coaxed to ask: How did he get so far?

This is, we might say, a curiosity question—a question about what in the past led up to the present. A film’s narration is often prodding us to ask just this question. A piece of narration may also provoke effects of surprise, as when the Velcro-target episode undercuts the corporate image. Surprise is central to narrative because knowledge is distributed unequally among characters and spectators; any character may have a secret.

There’s also suspense, which we can consider broadly as a sharpened anticipation of what might happen next. In The Wolf, I’d argue that there’s some suspense when Jordan, zonked on Quaaludes, must save Donnie from choking on a piece of ham. Curiosity, surprise, and suspense aren’t of course the only effects of storytelling, but they function as “master-effects,” in Meir Sternberg’s phrase. They are central to our comprehension of the story.

Style as narration

At the same time, narration is shaping our experience through film style. The staid tracking shot along the desks in the commercial, with the firm’s trademark lion prowling the aisles, clashes with the abrupt editing and freeze-frame that introduces Jordan. The actors’ performances, centrally the swaggering performance of DiCaprio, are part of narration as well. The soundtrack’s stylistic texture contributes a lot too, with Jordan’s voice-over and the music and effects creating a rousing, exhilarating effect. The narration’s use of film technique, I think, aims to summon up a shocked but fascinated and amused awareness of the decadent world that Jordan rules.

Throughout Wolf, Scorese’s stylistic choices serve narrational purposes. There are rapid montage sequences, commenting musical tunes, and dialogue hooks (“I won’t call him”/shot of Denham, called, approaching Jordan’s yacht). Scorsese’s fondness for rendering psychological states—here, druggy ones—is presented through classic “impressionist” techniques. As the film goes on, he starts to take us into characters’ minds through inner monologues and misperceptions (the smashed Ferarri). Stylistic patterning also contributes to the film’s tone of grotesque comedy, not just through the dialogue, delivery, and music but through editing. The potentially dramatic moment of Jordan rescuing Donnie with CPR is intercut with a Popeye cartoon: Jordan’s miraculous spinach is coke.

By shaping our knowledge, the narration also throttles the film’s emotional appeal up or down. For example, in one scene Jordan punches his second wife Naomi. Scorsese presents the action in a distant shot, in which a doorway allows us merely to glimpse the violence.

This choice lessens the impact of Jordan’s aggression. It gives us important information about the story action, but not nearly as forcefully as the tight close-ups of sexual and drug-fueled escapades in other scenes do. You could argue that closer and more visceral views (of the sort we get during Raging Bull’s domestic violence, as above) would make it harder to treat Jordan’s bad-boy high-jinks as entertaining.

A more detailed analysis would trace the overall development of the film’s narration. We’d consider, for instance, how it restricts our information at key points. Although the narration breaks with its attachment to Jordan to show Denham’s investigation, it doesn’t reveal Naomi’s scheme to divorce him. We learn of that only when he does. As we indicate in Film Art: An Introduction, “Who knows what when?” is a central question for understanding film narration.

Narration as inference-making

More generally, the essay develops in some detail a notion that’s central to understanding narration. I offer a mentalistic account of narrative understanding.

I think that a storytelling movie, through its narration, impels us to draw inferences. To follow a movie story is to turn the images and sounds into characters, actions, events, causes, and the like. This happens partly through fast, automatic inferences of the kind we make constantly in perceiving the world, and partly and more evidently through the inferences we make in building up that construct we call the movie’s story.

Everything I’ve been describing so far asks us to fill in, extrapolate, and draw conclusions at the level of comprehension. We take the Stratton Oakmont commercial as indicating trustworthiness. We’re encouraged to see the little-person-tossing scene as outrageous and boisterous but cruel, the amusement of people charged with a reckless energy. Jordan’s bragging montage sequence invites us see him as powerful, arrogant, and materialistic.

By saying that narration pushes us to make inferences I’m not suggesting that the inferences are models of deep thinking. They are, we say, commonsensical. In the multiplex, we’re not logicians. Understanding and responding to a story are processes based largely on folk psychology. In that respect, the chapter argues a point I’ve made elsewhere on the site.

Of course not all our inferences will be correct. It would be possible to knock down our first impressions of Jordan with information suggesting that beneath the sharkskin is a likable idealist. (That happens in Jerry Maguire.) Here, other sorts of moments steer our inferences astray. We’re led to think that Jordan drives his Lamborghini home safely, but that impression gets recalibrated the next morning. Earlier, when Denham visits Jordan on his yacht, the rather long, tense scene leads us to consider the possibility that the FBI agent is susceptible to bribery. His questions and facial expressions suggest that he’s weighing Jordan’s offer to help him with some investments. This interchange is conveyed in fairly tight shot/ reverse shots.

Only when Denham asks Jordan to repeat his offer does Scorsese cut to an angle showing that Denham’s colleague has, offscreen, quietly stepped close enough to bear witness to the bribe Jordan might offer.

Scorsese has choked off some information about the scene in order to yield a surprise, one that corrects the impression we were building up. One of cinema’s great pleasures is catching up with a narration that has been designed to lead us astray. Hitchcock fans, take note.

Dimension 2: Plot as pattern

You can also think about the narrative as having a more abstract, geometrical structure: that’s given to us as the plot. Narration creates on-line, moment-by-moment pickup; as viewers we go with the flow. The plot is more architectural, a sort of static anatomy of the film as a whole. We can think of it in a couple of ways.

As a map of a particular film, the plot consists of the overall arrangement of incidents. It lays out the story actions in time. It can proceed chronologically, as plots do most of the time, or it can rearrange incidents out of linear order. The Wolf of Wall Street follows the Stratton Oakmont commercial with the Velcro-target scene, and then presents Jordan at the height of his powers. But after the quick exposition of his lifestyle, the plot flashes back to his first day on Wall Street in 1987.

Now the film presents a mostly chronological layout. Jordan gets his broker’s license, loses his job, picks up a low-end one, and then rises to the spot running his company. This trajectory is sometimes interrupted by quick flashbacks filling in background on a character or a situation; we even get flashbacks within flashbacks. The overall time scheme is hazy, since we’re never shown exactly what point in time is “now.” There’s the suggestion that the initial flashback is rounded off when Jordan’s cohorts meet to plan the Velcro-tossing stunt, but that opening scene isn’t replayed, so we can’t be sure exactly when the opening flashback ends. The flashback must be finished at some indeterminate time late in the film, when Jordan’s fortunes decline and Naomi is alienated from him. But the narration whisks us along without establishing the firm framing devices of traditional flashback plotting.

From this perspective, every film establishes its own plot structure, based on the overall “geometry” of its scenes and sequences. There’d be a lot to say about this in The Wolf, such as the introduction of Denham (and the brief alternating scenes of his investigation) and the various lines of action that fill out the plot: Jordan’s addictions, his plan for an IPO, his two marriages, the SEC inquiry, his Swiss money-laundering schemes, and the like. The craft of screenwriting consists in large part of developing and braiding lines of action in this way. Several entries on this site, as well as many chapters of Narration in the Fiction Film and Poetics of Cinema, analyze how such plot patterns work in tandem with the narration’s unfolding.

Caught in the act(s)

Another way to think about plot structure is to consider how the particular film obeys broader principles of construction. Tragedy, comedy, melodrama, mystery stories, and other genres have distinct, widely-known conventions of plot geometry. There are as well traditions of plotting that cross genres.

In modern commercial cinema, the most famous structural convention is the three-act pattern. Kristin has proposed that Hollywood feature filmmaking is better thought of as adhering to a multiple-part principle based on characters’ goals. The film might have two, three, four, or more parts, depending on its running time and the ways it shows character goals created, reformulated, blocked, delayed, and fulfilled (or not). We’ve tested Kristin’s proposal in books (Storytelling in the New Hollywood, The Way Hollywood Tells it) and on this site (here and here and here and here).

The essay considers the matter more theoretically, but just to illustrate, I’ll hazard a layout of The Wolf of Wall Street’s plot structure. It’s nothing but spoilers, so I’ve flagged it all in olive green if you want to skip it.

Since Wolf runs about 173 minutes without credits, I think it can be usefully laid out in five large-scale parts. These are framed by a brief prologue (the commercial and the Velcro-target scene) and an epilogue summing up Jordan’s court sentence, his stay in a country-club prison, and his new career as “the World’s Greatest Sales Trainer.”

The Setup shifts from Jordan’s life at the pinnacle to his beginnings in the business and his rise as an entrepreneur. In the course of this portion he meets Donnie and the two assemble their team of eccentric, grotesque staff. After establishing Stratton Oakmont, Jordan demonstrates his sales technique and the script his salespeople will follow. This section consumes the first thirty-five minutes of the film.

What Kristin calls the Complicating Action, which resets the protagonist’s goals, centers on Jordan’s plan for an IPO and his affair with Naomi. Around the hour mark, Jordan is divorced and free to pursue the IPO, but now Denham of the FBI is following the company and the SEC is getting curious.

The Development section, which typically expands and delays the fulfillment of the goals set earlier, shows Jordan marrying Naomi, the firm’s frenzied launch of the IPO, and Jordan’s botched effort to bribe Denham. By about 96 minutes into the film, the two antagonists, Jordan and Denham, have faced off in a preliminary conflict. What remains is to see how Jordan will evade capture.

I’m inclined to see the fourth part as a second Complicating Action, because Jordan recalibrates his goal. Stratton Oakmont is making so much money he needs to find an offshore place for it. He decides on Switzerland, and the bulk of this section of Wolf focuses on whether he’ll be successful. But the SEC is breathing down his neck, and he momentarily considers quitting his firm. During a pep talk to his staff, his resolve weakens (he’s sold by his own rhetoric), and he decides to fight the regulatory battle. This is a turning point: now both the SEC and the FBI are on his tail with renewed vigor.

This section, a bit longer than the others, runs about forty minutes. I attribute that mostly to a wedged-in scene that’s almost pure delay: Jordan’s and Donnie’s wild night on Quaaludes, which ends with Jordan crawling toward his car, smashing it up, and saving Donnie from choking. Nearly all of this has no effect on the plot’s forward movement; Donnie survives and Jordan isn’t charged for the road mishaps. The only plot causality here is the fact that a wacked-out Donnie makes an incriminating call on Jordan’s home phone, which is tapped. This bit of action could have been handled much more briefly, but the Quaalude gluttony is so inherently funny, and forms such a plausible topper to the ‘lude motif throughout the film, that it’s expanded to a remarkable twelve minutes. This sort of delay is usually seen in Development sections, but because Jordan resets his goals in this section I’m considering it a Complicating Action.

The Climax (25 minutes) arrives when Jordan, hiding in Italy with Donnie and their wives, learns that Aunt Emma, his front for the Swiss money-laundering, has died. He must race back to Zurich to shift the money to a new account, and in the process the yacht is wrecked in a storm. He’s arrested and agrees to rat on his friends. Naomi divorces him. He tries to protect Donnie but fails and is sent to jail. In the epilogue he’s shown bouncing back, playing to an audience of suckers who share his dream of getting very rich.

Winter’s screenplay, with its parallelled and intertwined lines of goal-driven action and its reiteration of one large-scale component, a second Complicating Action, shows how the classical pattern can be expanded to fill out a longer-than-average running time.

Dimension 3: The story and its world

There’s a tendency to think of the story action as existing virtually before it becomes a plot and is presented through narration. It’s as if the story was already there, waiting to be turned into a film. To some extent, this can happen with documentary narratives and adaptations of novels, plays, and comic books. Nonetheless, as viewers we access a movie’s world only through narration and plot structures. In fact, “access” isn’t quite right. As I’ve indicated, I think that we construct the story inferentially, on the basis of the cues given by those other dimensions.

If every viewer has to build up the story herself, shouldn’t we have widely different senses of what happens? To some extent we do. People might fill in certain gaps differently, or draw divergent conclusions about what made something happen. Certain films, not typically Hollywood ones, do encourage more open explorations of the story situations. Here plot construction and narration may follow other conventions, such as those I’ve tried to chart in Narration in the Fiction Film and elsewhere.

Mostly, though, even in “independent films,” there’s a great deal of convergence among viewers’ inference-making. Sooner or later, we arrive at a common understanding of most of what happened and why. As we leave the shared realms of perception and comprehension, of course, viewers’ construals can diverge a lot. Once we get to abstract interpretations—such as whether The Wolf of Wall Street celebrates or condemns the anything-for-a-buck culture—we should expect a lot of variations. (I try to explain why this happens elsewhere in the book, in the essay “Poetics of Cinema.”)

“Three Dimensions of Film Narrative” considers the story and its world broadly, in terms of cues for causation and characterization. It focuses particularly on characters and how we understand them. Again I argue for an inferential model. This means that, as in real life, we’re practicing “mind-reading”—trying to figure out characters’ traits and temperaments on the basis of their behavior, trying to grasp their motives and goals. We build them up as persons on the basis of cues, and we ascribe to them many of the qualities we expect persons in the real world to exhibit. Again, folk psychology provides the ground: the film is likely to streamline and simplify the complexities of real-world personhood.

As viewers we don’t understand a character in isolation. Characters interact, and the narration and plot structure prompt us to compare them, rank them, sort them in different ways. In The Wolf, Jordan is handsome, brazen, and suave; Donnie, a classic weak friend, is awkward and homely, but he has a primal energy that matches Jordan’s slick élan.

Jordan’s father and most of his elders are more prudent and cautious than his crew, who are uninhibited. The guys are a bevy of misfits, distinguished from one another by looks and one or two tricks of demeanor.

Jordan’s first wife is a brunette hair stylist who voices doubts about his schemes; his second wife is a gorgeous blonde party girl who happily plunges into his lifestyle. In each case, the narration and the plot structure give us the necessary cues, usually redundantly. Jordan’s voice-over commentary reinforces the character information we get from the actors’ appearance and performance.

The essay also considers how films present character change. Sometimes characters come to learn more; they may not vary their distinguishing traits but they realize they have made a mistake. More deeply, characters may decide to get in touch with a suppressed side of themselves. That’s what happens, I think, in Jerry Maguire; he becomes the man his wife thinks he could be.

But very often characters don’t change. Jordan, in The Wolf of Wall Street, has an opportunity to confess, return the money he fleeced from his clients, and take his punishment. Instead, he insists that everything he’s done has been for his friends—the staff of the firm—and they deserve to succeed as he has. (Even though he is deceiving them too; he buys shares in his own IPO and orders the salespeople to push that stock.) What shocks many viewers about the film, I suspect, is that Jordan doesn’t become a better person in the course of his adventures. His punishment is light, he learns nothing, and by the end of the film he’s as amoral as he was when he started the company. (“Sell me this pen.”) As sometimes happens, the interest of the plot comes from watching a gifted, resourceful scoundrel adapt his techniques to changing situations.

But wait, there’s more

Okay, you may be asking impatiently. But why? Why offer these categories, carve things up, make supersubtle distinctions, concoct new terminology? Why not just do film criticism?

Well, partly because I want to articulate more than my response to a particular movie. I want to understand the more general ways in which films work and work upon us. I think we can usefully look for explanations of movies’ functions and effects, and these are things that ordinary film criticism doesn’t typically offer. For example, noticing how a film’s elements function with respect to narration, plot, style, and story world can do more than sensitize us to this or that movie. This sort of analysis can make us aware of broad norms of moviemaking and how particular films relate to those norms, currently and historically.

At the same time, the line of thinking I’m proposing casts light on the skills we deploy, mostly unawares, in experiencing films. No matter how simple-minded the movie, I think that we do things in following it; we exercise our narrative competence. On the other side, sorting things out this way can explain the range of choice and control open to the filmmaker. I think that the poetics of cinema I propose can help filmmakers become aware of the tools they are using–and perhaps encourage them to try other ones. My categories are derived from filmmaking craft, and perhaps they can in turn illuminate the practical tasks facing filmmakers.

A couple of final points. In the chapter I draw examples from a variety of films, many American (Cellular, Boyz N the Hood, You’ve Got Mail, etc.). Despite my consideration of Ashes of Time, Claire Dolan, Memento, and other films, some readers will ask why I don’t consider more non-Hollywood examples. The choice was strategic: Hollywood films throw the areas I’m charting into sharp relief. They provide clear-cut (not necessarily simple) examples of my points. And historically, the dominance of Hollywood film in the world’s theatrical market have given them a lot of influence. Much of what we think of as non-Hollywood is based on attempts to revise or reject those norms.

At the same time, I’m counting on readers cutting me some slack because I’ve written a lot about alternatives to Hollywood. My books on Eisenstein, Ozu, Dreyer, and Hong Kong cinema try to analyze diverse storytelling options. Elsewhere in Poetics of Cinema I discuss various narrative traditions, including varieties of network narratives and forking-path plots. Narration in the Fiction Film explores still other storytelling modes. And on this site I’ve had a lot to say about non-Hollywood constructive principles (for example, here and here).

The last section of the essay considers what is probably inside-baseball for many readers. Yet the underlying question is important. How adequately can film narrative can be understood on a model of literary narrative? Some theorists think that the basic principles of narrative are to be found in verbal storytelling, and narratives in other media must find equivalents for them. My own view is that narrative as a phenomenon gets mapped onto different media in varying ways. There may not be a single model that will be valid for plays, novels, dance, comic strips, radio drama, film, digital fiction, and so on.

For example, if Jordan Belfort were a character in a novel, certain weird things wouldn’t be happening onscreen. A first-person narrator in the novel can tell us only things that she or he knows about. But “inside” Jordan’s tale we get all kinds of scenes that he didn’t witness. True, he knew that FBI agent Denham was on his trail, but he couldn’t know the color of Denham’s office, or what Denham said to his colleagues. Nor could Jordan know exactly how the quarrel between his partner Donnie Azoff and his ally Brad Bodnik went down, even though we see the entire scene embedded in “his” telling.

Of course we can say that these scenes are just movie conventions. We accept that in film, first-person voice-over often includes scenes that the speaker didn’t witness, or maybe didn’t even know about. But that convention points to the limits of importing models of storytelling from literature to the study of cinema. A novel can’t wedge those things in without raising the question of how the narrator knows this. We just don’t ask such a question about Jordan.

By a path too winding to summarize here, these and other observations lead me to a counterintuitive conclusion: Narrative, at least in film, isn’t best understood as an act of communication from an author-like entity to a reader-like one. Why do I say that? How can film not be communication? Answer, too brief: What most people call communication I call converging inferences.

And to end my trailer, I suggest that we think of narrative in all media, most especially film, as inherently promiscuous. It will pull in anything that gets the immediate job done. That includes grabbing one element of ordinary conversation–a guy telling a story–without keeping the other bits of the communicative chain, such as feedback from a listener. Jordan is talking to us, but he doesn’t know we’re here, and we can’t interrupt him.

One more time: You can get the essay here. Thanks for reading!

In a way this post is a sequel to the previous entry; background on Meir Sternberg’s account of curiosity, suspense, and surprise can be found there. For more on the subject, see our category “Narrative strategies” and the essay “Common Sense + Film Theory = Common-Sense Film Theory?”

Many of the everyday terms we apply to stories are ambiguous or vague, so sometimes we need to define our terms or invent new ones. Take “narration.” In ordinary talk, can mean “voice-over commentary,” such as Jordan Belfort’s in The Wolf of Wall Street. But if we restrict our usage to just this form of sound, we don’t have a good term for the general flow of narrative presentation in the film, let alone films that don’t have voice-overs. So it’s useful to reserve “narration” for that general process and use “voice-over” in some form to describe the soundtrack’s role in that.

The same problem comes up with the term “point of view,” which has many different meanings. It might refer to first-person reportage, or what a character thinks and feels, or what she believes. (Obama is a good president from her point of view.) If we want to be precise in talking about these qualities of storytelling, we need to explain the terms we’re using.

And sometimes it’s just easier to introduce new terms. In the essay, I’ll sometimes call the plot the syuzhet and the story the fabula. Why the fancy terminology? Won’t “plot” and “story” do? Well, yes, up to a point. In this entry I did use those terms, and our textbook Film Art: An Introduction has done that ever since its first edition of 1979. Still, when we’re working within a research community, it helps to have terms, even unusual ones, which say exactly what we mean. The original readership for the “Three Dimensions” chapter knows that “plot” and “story” have different meanings in our culture, and so I tried to use terms that were less ambiguous. Not incidentally, I wanted as well to signal my debt to the Russian Formalist literary critics, perhaps our first modern narratologists.

Other chapters of Poetics of Cinema are posted online here.

P.S. 14 January 2014: Thanks to Steve Hilby for correcting me: I originally mis-identified Jordan’s car as a Ferrari.

P.S.S. 14 January 2014: My old friend Brian Rose signals his Academy interview with the filmmakers, in which Scorsese and Schoonmaker declare a lack of interest in “plot.” Pfui, says I.

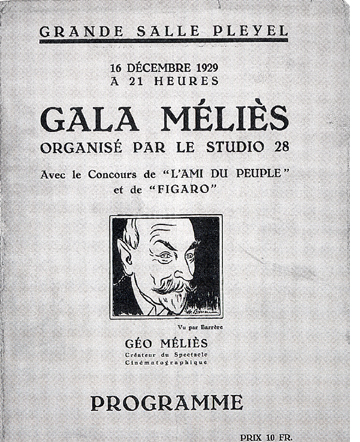

HUGO: Scorsese’s birthday present to Georges Méliès

Kristin here:

This is the 150th anniversary of the birth of Georges Méliès (1861-1938). I doubt that the release of Hugo was timed to coincide with the occasion. If it were, no doubt the press kits issued by Paramount would have stressed the fact. Still, it’s a happy coincidence.

Hugo is receiving a lot of press attention, not surprisingly. If you’ve read more than one or two of the reviews and articles about Martin Scorsese and his film, you already know the two main hooks that journalists have hung them on. (Whether these originate from the pressbook or are just so darned obvious that everyone can figure them out, I don’t know.)

One, Scorsese is passionate about film history and preservation, so Brian Selznick’s best-seller quasi-graphic novel for children, The Invention of Hugo Cabret, based on the old age of early director George Méliès, would be a natural source for him to adapt. Especially so, since Selznick designed the illustration-heavy book to imitate a film, with series of drawings suggesting camera movements.

Two, the subject of Méliès’ pioneering special effects in the service of fantasy would be the perfect vehicle for Scorsese’s first venture into 3D.

True, no doubt, both of those points, and necessary to ease viewers with no knowledge of film history into this fairly sophisticated film. Not that the critics provide much help with the film’s many allusions to Parisian culture of the first decades of the twentieth century. There are real popular songs and posters for many silent films. I didn’t see any reviews pointing out that James Joyce and Salvador Dalí can be glimpsed fleetingly in Madame Emile’s café. (I spotted Joyce but not Dalí, only learning of the latter’s presence from the credits.)

Apart from signalling such references, however, there is a great deal more that one can say about the film. Some aspects of it are obvious, as befits a movie made in part for children. Others are more subtle, as befits a movie made in part for adults. I’ll offer a few observations here.

By the way, reviewers have made much of the idea that Hugo is not really for children, who would be bored and perhaps frightened by it. I suspect that children under about the age of 10 would be, but older children and teenagers, especially those who read books, should be intrigued by and enjoy it. Like Pixar films or The Simpsons, it’s the sort of thing that can be enjoyed by adults as well as children.

Movies within movies

Hugo is centered around Méliès’ work and tries to recreate something of the magic of the making and viewing of these films. Yet beyond this, it is steeped in the forms and subjects of pre-World War I cinema in general, to the point where the plotlines of Hugo subtly imitate early films.

A turning point in Hugo‘s story comes when Hugo and Isabelle invite fictitious film historian René Tabard (whose name is borrowed from the popular, Chaplin-impersonating teacher young student in Zero for  Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

Conduct who starts the revolt) to screen A Trip to the Moon in Méliès’ apartment. At first the director happily describes his film career, but when he reveals its unhappy decline, he concludes despairingly, “Happy endings only happen in the movies.” Scorsese proves and yet contradicts this claim by providing happy endings in the subplots of the film. These subplots are presented as if they were short, early films, but divided up and played out as running vignettes that add up to simple stories.

In the book, the station’s Inspector, played by Sacha Baron Cohen, is a minor figure, glimpsed once from a distance by Hugo and finally coming to threaten him with arrest on page 412. His war wound and early life as an orphan are not part of his character. The Inspector is abetted by the café owner Madame Emile and the newsstand proprietor Monsieur Frick, sinister figures who appear only in this single late scene. They exist primarily to reveal the news of the discovery of the corpse of Hugo’s drunken uncle and to bear witness to Hugo’s thefts of croissants and milk from the café. The flower-shop girl, Lisette, whom the Inspector clumsily courts in the film, is not in the book at all.

What Scorsese very cleverly does is to expand these characters and have them play out what are in effect two brief narratives that could easily be imagined as early silent shorts. Madame Emile (Frances de la Tour) and Monsieur Frick (Richard Griffiths) are transformed from nasty busybodies into a charmingly comic elderly couple whose tentative flirtation is thwarted by Emile’s aggressive dachshund. In two scenes, the dog bites Frick, once on the finger and once on the ankle. In the third scene, Frick solves the problem by providing a lady dachshund to divert the pesky pooch’s attention. One could easily imagine this as a short film from around 1906, making these two the leads and concentrating on their courtship. The dog could thwart the news-vendor’s approaches a few times before the happy ending is achieved with the introduction of the second dog.

The overbearing Inspector’s romance with Lisette is developed at greater length, and one could imagine it as a one- or even a two-reeler of the early 1910s. The Inspector’s attempts to court the young lady could be contrasted with his chivvying of the pathetic young orphan, actions that make her reject his advances. At the end, she might witness him relenting and treating the boy kindly, as indeed happens in Hugo, leading to another happy romantic conclusion.

In general, the situations and characters that we encounter in Hugo are common in early cinema. How many films, especially French ones, involve gendarmerie with their round, flat-topped caps, chasing mischievous little boys? How many melodramas revolve around poor children made homeless by their parents’ or guardians’ drunkenness? How many gags involve men stepping on musical instruments and smashing them? While the most explicit cinematic reference is to the Harold Lloyd feature Safety  Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

Last, the world which Hugo and Isabelle and Papa Georges inhabit is like an early program of silent shorts, but one in which the actions blend in counterpoint.

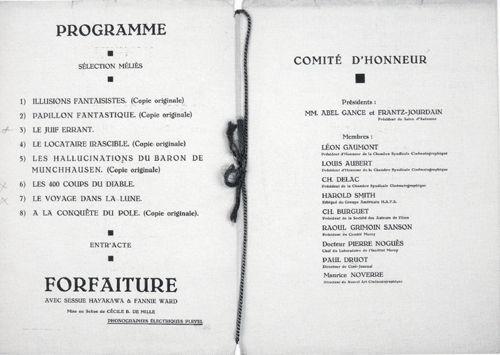

In a sense there are little topical and instructional films as well, with the reference to the dramatic historic accident at the Gare du Montparnasse on October 22, 1895, when a train crashed through its buffers and out the front wall of the station. (In reality, one death occurred: the wife of a news vendor who was minding the shop for her husband. Perhaps the Emile-Frick romance creates a happy ending of the cinematic variety to make up for that tragedy.) We also have the lesson in cinema history provided by Tabard. At one point in the flashback narrated by Méliès, apparent newsreel footage of World War I troops, touched up with hand-coloring, appears.

The film-like subplots all end happily, yet they are represented as being reality within Hugo. Perhaps for that reason, none of these brief narratives is the sort that Méliès would have used in his own films. They’re more like the non-fantastical comedies and chases made by Louis Feuillade and other directors.

The happy ending for Méliès occurs in Scorsese’s film, and yet it also happened in reality, if not quite the way it is shown here.

Cruelty, kindness, and the shape of the story

The structure of the narrative reflects the simplicity of each short film. It conforms well to the four-part narrative structure that I have claimed to be conventional practice in classical storytelling. Yet it also breaks neatly into two halves, the first about cruelty and the second about the sort of kindness that makes possible the happy endings. One can picture it as a V shape, with Hugo descending into greater loneliness and danger up to the mid-point and then climbing back toward happiness with the help of others.

Early on, both fate and other people are cruel. A museum fire has killed Hugo’s father, and his mother had earlier died of unspecified causes. Hugo’s drunken uncle wrests him from his home and school to live a fugitive life in the station. “Papa Georges,” whose full identity we do not learn until well into the film, seems unnecessarily harsh with the young Hugo. The Inspector obsessively hunts down stray children to send off to the orphanage. The bookseller Labisse, though generous in loaning books to Hugo’s friend Isabelle, looks upon Hugo with disdain. Even the two dogs, Madame Emile’s comic dachshund and the Inspector’s doberman are growling, threatening beasts.

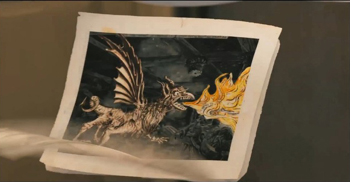

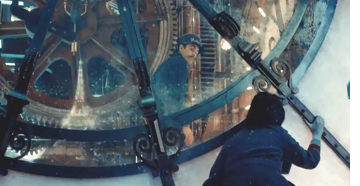

The automaton, of course, is the key to all. Once it provides the necessary clue by drawing the  famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

famous image of the rocket stuck in the Man in the Moon’s eye, Hugo and Isabelle go to the Méliès apartment and discover the box full of the master’s designs. This incident forms the central turning point, coming almost exactly midway through the film (61 minutes into a film that runs roughly two hours, not counting its credits).

Ordinarily at this point in a Hollywood film, there would come a section where the protagonist struggles against obstacles to achieve his goal. In Hugo, however, the crisis at the center leads immediately to a series of kind actions. Upon returning to the station after the drawings discovery, Hugo runs into M. Labisse, who unexpectedly gives him a book that the boy and his father had read together. Then Madame Emile urges the Inspector to speak to Lisette, whom he has admired from afar, and coaches him in how to smile pleasantly. His smile, plus his halting success in his first conversation with Lisette, motivate his eventual ability to take pity on Hugo.

This scene leads directly to the scene at the “Film Academy Library” (a giant fictitious room full, apparently, of books on cinema) where the film historian and Méliès fan, René Tabard, appears. He will provide the screening of A Trip to the Moon which finally draws Méliès out of his depression to some degree. Yet the filmmaker still despairs as he thinks of the disappearance of his studio, the rest of his prints, and his beloved automaton. Hugo rushes off to fetch the latter, and after an extended chase sequence returns it to Méliès with the help of the Inspector, who saves the machine and the boy from an oncoming train. Recognizing something of his own youth in the distraught boy, the Inspector turns him over to Méliès for the happy ending.

The exception to the cruelty/kindess division of the film is Isabelle. In the original book she is not such a pleasant character, often arguing with Hugo. She does not have the joyous desire for adventure that the Isabelle of the film displays. The change is an improvement. In part this is because Hugo is such a very grim and forlorn character through much of the book. Portraying him that way in the visual medium of film might make his plight too pathetic to be entertaining. Isabelle’s early sympathy for him and fascination with the mystery of the automaton carries a strong thread of hope across both halves of the narrative.

In the lengthy epilogue there is a gala screening of some recovered Méliès prints, and a party is held. All the significant characters are present, with their satisfactory futures assured. Hugo will seemingly become a magician (as he does in the book). Isabelle has apparently found her hoped-for purpose in life, for she starts writing down the story that we have just witnessed. (In the novel, Hugo himself writes The Invention of Hugo Cabret, though he attributes it to the automaton.)

A machine-made ending

The film ends with a tracking shot, independent of the characters’ points-of-view, into a nearby room where the automaton sits, still and alone. As we approach its enigmatic face, the image fades out. The moment ends the imagery that has continued through the film, of humans as machines and  machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

machines as humans. Hugo’s one hope as an orphan is to fix the automaton, his only link with his dead father. The moment that it is fixed leads to the drawings and Méliès’ breakdown, the first clues as to why he is so embittered. Hugo and Isabelle discuss how machines have purposes, and therefore people do, too. Papa Georges has lost his purpose and hence needs fixing. Once that is accomplished, with the help of the automaton, Hugo finds a new father figure and his happy ending.

The machine imagery goes further. The opening of the film dissolves from a set of moving clock gears to merge them graphically into a high view of the boulevards of Paris, which momentarily appears as a giant glowing, whirling machine with the Eifel Tower, symbol of the modern machine aesthetic, at its center. The repair of a wind-up mouse becomes the first small point of emotional contact between Méliès and Hugo. The Cinématographe camera/projector that fascinates Méliès even more than the moving images on the screen becomes the central machine, one which produces what one normally thinks of as the most private and mental of events, dreams.

All this machine imagery is fairly obvious, but it seems completely appropriate if we remember that this is, after all, a film partly for children. What I’ve been describing are things that a smart child could grasp, but the imagery and story aren’t done in anything like a condescending way.

The automaton, by the way, really did the drawing in the film itself, without CGI or other sorts of animation being used. For a three-minute film that ends with a fast-motion demonstration of its drawing capabilities, see here. For a demonstration of the restored Maillardet automaton in the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia, which Selznick used as his inspiration, see here, where it creates a drawing as complex as the one in the film. This automaton also revealed its origins when, after being restored, it signed its maker’s name.

[Dec 9: My claim that the automaton did the drawing without special effects was based on some statements by the company that made it (or more specifically, 15 versions of it). A recent article here interviews the film’s visual-effects supervisor Rob Legato reveals that the drawing scene was accomplished using magnets below the table: “The robot or automaton was not CG, although there were some CG doubles for some complex shots such as the train line fall. Prop builder Dick George constructed 15 automaton versions and some that actually could draw on paper. The VFX and special effects team solved the complex task by using magnets. Below the paper was a motion controlled magnetic system that traced the hand encoded drawing. The arm then moved to match the magnets and draw the famous picture. In a couple of shots if you could pause and really study the frame you might see that the pen nib, at those points, ‘is a ball point and not an ink well pen,’ comments Legato.” So the automaton did do the drawings, but not based on its complex system of gears and other clockwork visible inside it.]

How accurate is it?

Naturally the events of history are messier than the neat scenario of a mainstream film could encapsulate. Still, given the constraints involved, Hugo‘s modifications of the facts seem quite reasonable, and on the whole the general public will exit the theatre with a decent impression of Méliès’ career.

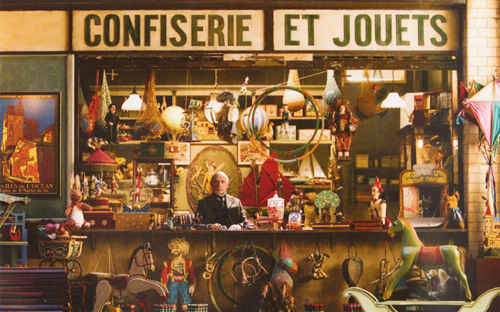

In fact he was married twice. Jehanne d’Alcy had been Méliès’ mistress well before they married in late 1925. They had both worked at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin before the cinema was invented, and d’Alcy appeared in many of Méliès’ films. (His first wife, Eugénie, died in 1913.) D’Alcy brought with her the ownership of a little candy-and-toy shop outside the Gare Montparnasse, which the couple transferred inside the station and ran together (see bottom). World War I did not cause the demise of Star Films. Méliès had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

had made his last films in 1912, and in 1913, owing money to Pathé Frères, he nearly had to give up his Montreuil studio to the larger company. Ironically, the war led to a freeze on such payments, and Méliès was able to hold onto the property until 1923.

As biographer Paul Hammond describes his decline, “Georges Méliès had become an anachronism, an artist left behind by economic and aesthetic developments.” In looking at Méliès’ late films, we might keep in mind that 1912 was the year of Albert Capellani’s remarkable serial adaptation of Les misérables. Max Linder was at the height of his popularity, and D. W. Griffith was making some of his finest one-reelers. The three great Swedish silent-era directors, Mauritz Stiller, Viktor Sjöström, and Georg af Klercker, all made their first films in 1912. The year 1913 would see a burst of cinematic inventiveness around the world, and Méliès would have seemed all the more old-fashioned by comparison had he continued to make movies. Nevertheless, he remains perhaps the only one of the very earliest generation of filmmakers whose work we return to not simply out of historical interest but for the fun and wonder of the films.