Archive for the 'Directors: Jackson' Category

The Gearheads

Mourning.

DB here:

At the Wisconsin Film Festival I saw the best film I’ve seen over the last six months. I can’t really say much about it, but I’ll do what I can. My remarks make most sense, I think, if I embark on a pretty long detour.

The frame-rate shuffle

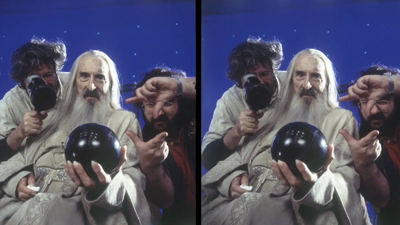

3D still photographs by Peter Jackson taken during the filming of the Lord of the Rings trilogy.

In the wake of April’s convention of the National Association of Theater Owners, the biggest press tumult surrounded Peter Jackson’s ten-minute demo from The Hobbit. Fulfilling what James Cameron had called for at the 2011 NATO confab, Jackson has been shooting at 48 frames per second, and the demo was screened at that rate. Cameron and Jackson are concerned that there’s too much image judder and strobing in digital cinema, especially 3D. They propose a higher frame rate to smooth things out.

Opinion on the Hobbit footage was divided. Some theatre owners and operators were happy with it, but others were uneasy. The higher frame rate tends to eliminate motion blur and create a sharpness that recalls, for some viewers, the brittle look of HD sports broadcasts. “It looked to me like a behind-the-scenes featurette,” said one.

Jackson, who has been preparing for this initiative on his Facebook page, defended his decision. He maintains that audiences will adapt to it, just as his production team has. Many exhibitors seem to have dismissed the new initiative as too expensive, particularly at a time when many are still paying off the digital conversion. But the Regal Entertainment Group, the largest cinema chain in the US, announced plans to outfit up to 2700 screens so that The Hobbit can be screened at 48 fps. It now seems possible that The Hobbit may be shown in no fewer than six formats: 2D, 3D, and Imax, and in each there will be both 24 fps and 48 fps presentations.

Not being present to watch the footage, I have to withhold judgment about how it looks. I haven’t though, withheld my opinion about how Cameron and Jackson, along with George Lucas, have used their roles as superstar directors to prod exhibitors to adopt expensive new technology. They acted as the figureheads for the switch to digital in 2005, using 3D as the incentive for exhibitors to convert. A few years later, after proposing 3D television, Cameron upped the ante by urging higher frame rates for film. Jackson has joined him by actually making a film at 48 fps. Cameron has said he prefers 60 fps, which may mean that the goal posts get shifted again when Avatar 2 or something else comes along.

You can go to my earlier post for more thoughts on their tactics. My book on the digital conversion, due out on this site in a few days, offers a fuller account. In the meantime, I’m going to try to understand this frame-rate fracas in a wider historical context.

The palette

Cinema technology has been surprisingly stable, as befits its status as the last surviving nineteenth-century engine of popular entertainment. The dimensions of the film strip, the rate of shooting and showing, and other fundamental factors have altered relatively little. The coming of sound and then the replacement of nitrate-based film by acetate are perhaps the biggest alterations in the basic technology. Below this macro-level, though, innovation has been constant.

From the 1920s through the 1960s, most of the change came in the production sector. The adoption of panchromatic film stock; color processes, principally Technicolor and the monopack systems like Agfacolor and Eastman Color; the development of various lighting units (carbon-arc, incandescent, Xenon); the shift from optical sound recording and reproduction to magnetic processes; the emergence of different sorts of camera support (varieties of tripod, dollies, and cranes, along with handheld devices)—all of these shaped how movies were made but had relatively little effect on how they were shown.

Some 1950s innovations launched in the production sector, notably widescreen cinema, stereophonic sound, and 3D, reshaped exhibition more drastically, because they came at a moment when theatres were anxious to lure back their clientele. Other revampings of exhibition, like wide-gauge film (65mm/70mm) and Cinerama, were never intended to be the universal standard. They were designed for a distribution system that included roadshow exhibition. Dedicated screens showcased big films like The King and I and Lawrence of Arabia for long, well-upholstered runs before the film hit the neighborhoods and the suburbs.

Producers innovate and exhibitors hesitate. Exhibitors must be cautious and conservative; they risk revamping their venue at great cost only to find that the new technology isn’t catching on. The roadshow system repaid exhibitors well, until it collapsed in response to the rise of saturation booking in the 1970s. For similar conservative reasons, exhibitors looked askance at the digital sound reproduction technologies that emerged from the 1970s through the 1990s. At one point, a house had to accommodate four different sound systems, some of them subject to periodic upgrades.

When technologies emerge in the production sector, they mostly promise to enlarge the filmmaker’s palette. A 1950s film could be made black-and-white or color, deep-focus or soft-focus, with arc or incandescents, flat or anamorphic, and so on.

In practice, of course, not everything was possible on every project. Budgets, as ever, limited options, and many directors and DPs disliked shooting in color or CinemaScope but were obliged to do so. And there were some trade-offs. Filmmakers of the 1930s could not shoot on orthochromatic stock, and after the mid-1950s, it was hard to make a film destined for the classic 1.37 Academy ratio. Still, there were few absolutely forced choices, and many directors explored different options from project to project.

The prospect of an enhanced palette is in fact one reason that some filmmakers embraced new technologies. Sergei Eisenstein (who trained as an engineer) was eager to try out sound, color, and even television because they expanded creative choice. Orson Welles saw in the RKO effects department, which had pioneered sophisticated optical-printer work, a way to create images that couldn’t be generated in the camera. As is now widely known, many of Citizen Kane’s most famous “deep-focus” shots were achieved through special effects. Similarly, Stanley Kubrick renewed the power of his images through his eager adoption of new technologies, including long lenses for Paths of Glory, the handheld camera in Dr. Strangelove, faster lenses for Barry Lyndon, and the Steadicam for The Shining. These filmmakers wanted to multiply options, not foreclose them.

Share our fantasy

The changes that Cameron and Jackson propose are more sweeping. Now that digital projection is an accomplished fact, there will be backward pressure to create a wholly digital workflow. Filmmakers who want to shoot on 35mm will be reminded that they will eventually be fiddling with a digital intermediate, and that the final version will be digital, not film-based. A selling point of digital cinema to the creative community was the promise of complete control over the film’s look and sound, so that the audience gets exactly what the filmmaker envisioned. To assure that integrity, the director will have to shoot and finish the project on digital. That will take away an entire dimension of choice—specifically, shooting on film.

The pressure to shoot 3D adds to this. Martin Scorsese and Ang Lee showed up at the same NATO convention to praise the format. Now films that aren’t tentpole items can be made in 3D, they agreed. According to Variety, Scorsese claimed that “2D projection [sic] will eventually go the way of black-and-white—used primarily as a stylistic choice—as auds will soon acclimate to depth even in indie films.” This sounds like a widening-of-the-palette defense, as does his reaction to new frame rates. “You can do anything you want [in post-production] with that image at that level of clarity, can’t you?”

In contrast to Scorsese’s offhand pluralism, Cameron, Jackson, and their confrère Lucas may be creating a scorched-earth policy. Their conception of cinema, I would say, is now largely that of the Gearhead. Their notion of artistry has become quite mechanical, in that they see progress to depend almost wholly on improved hardware (and software).

They represent three mini-generations of Hollywood techno-lover: Lucas, who began in animation; Cameron, who started as a model-builder; and Jackson, the 1980s fanboy who played with King Kong action figures. They are directors who treat cinema as a delivery system for stories grounded in genre conventions. Fantasy is their touchstone, and realism of any sort bears only on how vividly we perceive the images, not what the films show or say or suggest.

Back in 1999, Lucas noted frankly that film was becoming a form of painting, “unfixing the image.”

You have news footage, you have documentary footage—which are supposedly realistic images—and then you have movies, which are completely fantasy images. There’s nothing in a movie that’s true or real—ever . . . . The people in the movie are actors playing parts. The characters are not real. The sets are not real. If you go behind that door you’ll see there’s no building—it’s just a big flat piece of wood. Nothing is real. Not one little tiny minutia of detail is real.

The Hollywood cinema was then putting fantasy and special effects at the center of its aesthetic, and Lucas understood that every film—action picture, romantic comedy, even dramas—would rely on special effects to a new extent.

Here’s Cameron saying the same thing in defending 3D in 2008.

Godard got it exactly backwards. Cinema is not truth 24 times a second, it is lies 24 times a second. Actors are pretending to be people they’re not, in situations and settings which are completely illusory. Day for night, dry for wet, Vancouver for New York, potato shavings for snow. The building is a thin-walled set, the sunlight is a Xenon, and the traffic noise is supplied by the sound designers. It’s all illusion, but the prize goes to those who make the fantasy the most real, the most visceral, the most involving. This sensation of truthfulness is vastly enhanced by the stereoscopic illusion.

It’s hard to believe that Lucas and Cameron don’t know the long tradition of debate in the arts about realism. Realism can be considered a question of subject matter, plot plausibility, random detail, psychological revelation, and many other things; it isn’t just about trompe l’oeil illusion. Moreover, documentary and experimental filmmakers have suggested that cinema can capture moments of unplanned truth. And André Bazin and others have argued that even when presenting fictional tales, photographic cinema gives us unique access to some essential qualities of phenomenal reality. For Bazin, even an awkwardly shot scene could preserve the sensuous surface of things with a conviction that no painterly manipulation can equal—not perfection but brute facticity. Instead, Lucas and Cameron offer a Frank Frazetta notion of realism: glistening, overripe, academically correct rendering of things we’ve seen many times before.

Turnstile dynamics

NATO’s 2005 ShoWest convention: Lucas, Robert Zemeckis, Randal Keiser, Robert Rodriguez, Cameron.

I see a valid place for a cinema of splendor and spectacle, especially in certain genres. There’s nothing wrong with seeking new methods of pictorial representation, as Spielberg did in Jurassic Park, a genuine triumph of veridical realism. Nor am I trashing Lucas and Cameron wholesale; I admire their early films a fair amount. But they’re forcing their conception of cinema on all filmmakers.

Am I being unfair? I don’t think so. When directors say that digital or 3D or 48 fps is the future of cinema, they’re implying wholesale conversion is in the offing. Although Scorsese says that 2D or another frame rate will remain an option, Cameron and Jackson aren’t quite so open-handed. Because they’re convinced that the result is much more immersive, and immersion is always good, the technology should suit every kind of movie. Cameron again:

It is intuitive to the film industry that this immersive quality is perfect for action, fantasy, and animation. What’s less obvious is that the enhanced sense of presence and realism works in all types of scenes, even intimate dramatic moments.

Both directors usually add that they’re not insisting that every film is suited to the new bells and whistles, that it has to suit the plot and so on—the usual boilerplate about the primacy of “story.” “Stereo [imagery] is just another color to paint with,” says Cameron.

But they sound as if not having 3D or 48 fps puts the movie at a disadvantage. Cameron in 2008:

Every time I watch a movie lately, from 300 to Atonement, I think how wonderful it would have been if shot in 3D.

Jackson in 2011:

You get used to this new look [48 fps] very quickly. . . Other film experiences look a little primitive. I saw a new movie in the cinema on Sunday and I kept getting distracted by the juddery panning and blurring. We’re getting spoilt! . . . There’s no doubt in my mind that we’re headed toward movies being shot and projected at higher frame rates.

As happened before, the pronouncements of the directors mesh well with the initiative of the manufacturers. Back in 2005, Cameron, Lucas, Jackson, Robert Rodriguez, and Bob Zemeckis took to the NATO stage to help sell the Digital Cinema Initiatives program to skeptical exhibitors. Their support (and the box-office numbers of the 3D Chicken Little) aided the projector manufacturers Christie, Barco, NEC, and Sony in rolling out units. The number of digital screens in the US and Canada jumped from ninety in 2004 to over 300 at the end of 2005.

This year, with about two-thirds of all US screens fully converted, Christie circulated a promotional leaflet tied to Jackson’s demo. A few years ago, the future was all about 3D, but now, the text states flatly, “The future of cinema is all about high frame rates.” The cards are on the table.

At just 24 FPS, fast panning and sweeping camera movements that are a critical part of any blockbuster are severely limited by the visual artifacts that would result. . . .

The “Soap Opera Effect” has been derisively used to describe film purist perceptions of the cool, sterile visuals they say is [sic] brought on by digital.

But the success of Hollywood, Bollywood and big-budget filmmakers around the world has little to do with moody art-house films. The biggest blockbusters are usually about immersive experiences and escapism—big, vibrant, high-action motion pictures.

The HFR system, then, aims to spiff up franchises and tentpoles, and all other filmmaking must be dragged along and adjust. Although Jackson says he has heard no plans to charge more for 48 fps shows, Christie thinks we would pay for this treat:

Beyond the simple turnstile dynamics of “must-see” movies, a new, higher standard of movie-going should support premium pricing. Managed right, hotly-anticipated 3D HFR should empower ticket up-charges.

By all signs, the churn won’t stop. “Every three months you’re behind,” says Ang Lee. “We’re guinea pigs.” David S. Cohen, technology writer for Variety, believes that 48 fps is a transitional technology and that 60 fps will win out (“but not soon”). He adds: “Bizzers in both TV and movies are going to be making creative and financial decisions about HFR for years—maybe forever.”

Lucas and Cameron, and then Jackson, grasped that if cinema technology went wholly digital, it would change in fundamental ways. It would turn a medium into a platform, like a computer operating system. The most basic technology of showing a movie would become subject to rapid, radical, ceaseless remaking. It would demand versions, upgrades, patches, fixes, tweaks, and new software and hardware indefinitely.

I’m not sure that NATO’s members have fully realized this. They went into the deal lured by the chance to raise ticket prices and thus offset flat or slumping admission numbers. But attendance is still stagnant, even with the occasional stupendous successes like Avatar and The Avengers. Interestingly, AMC, one of the Big Three circuits that invested heavily in digital projection, is reportedly in talks to sell out to Chinese investors, and other chains are on the auction block. The studios are proceeding with VOD plans that may thin theatrical attendance even more.

Meanwhile, exhibitors face a long future of payouts. When cinema goes IT, as Steve Jobs might put it, we should expect a big bag of pain.

And now for something completely different

I saw Morteza Farshbaf’s Mourning (Soog) on a so-so DigiBeta copy at the Wisconsin Film Festival. This Iranian feature was shot on some godforsaken digital format, certainly nothing that Cameron and Company would approve. For all I know, its camera movements may have strobed unacceptably. I didn’t care.

Cameron et al. claim to worship the god of Story, but no film they’ve made has this subtle a grasp of narrative. Mourning gives us a plot so full of twists—in terms of what happens and how we learn about it—that I can’t summarize even the basic situation without subtracting some of your pleasure. A man and a woman are driving a little boy through a landscape. That’s about all I can tell you.

The film critics at Christie would consider it a moody art-house film. It’s also simple, suspenseful, and surprising, even shocking. It is formally inventive, emotionally poignant, and respectful of its characters and its audience. It is gentle but also unflinching. It’s the closest thing to Chekhov I’ve seen onscreen in a long time.

Was I immersed? Yes, but not in the way Cameron et al. define that state. I was trying to figure out what had already happened, what was happening at the moment, and what might happen next. And maybe I wasn’t seeing things “realistically,” in the 3D sense, but I was seeing something that captured the world we live in—our surroundings (and their stubborn physicality) and our relations to others. That world was also poetically heightened through the most straightforward means: camera placement, lighting, cutting, sound design. The film was, in other words, working in ways that we have always considered central to cinema’s creative mission.

Mourning is part of the fine Global Lens program of circulating features. Here’s a schedule of where and when films in the program are playing. Ask your local festival or art house to book Mourning, or try to see it when it’s available online or on disc. It’s even worth an upcharge.

Lucas’s remarks on realism come from “Return of the Jedi,” an interview with Don Shay in Cinefex no. 78 (July 1999), 18. Figures on the adoption of digital cinema are taken from the report, “Digital Cinema Roll-Out Begins,” Screen Digest (April 2006), 110. A detailed video explaining Hobbit production methods is here, as part of the video diaries on Jackson’s Facebook page. For more from a veteran, see “‘The Hobbit’: Douglas Trumbull on the 48 Frames debate.”

After writing this, I found that Devin Faraci of Badass Digest has a vigorously critical entry on the footage and even calls Jackson and Cameron “gearhead directors.” So I can’t claim originality, but it’s nice to know I have a badass ally.

Thanks to Jim Cortada, author of the forthcoming Digital Flood and Co-Director of the Irvington Way Institute, for explaining IT matters to me.

P.S. 11 May: Christopher Nolan, still embracing film-as-film, claims he’s no gearhead.

It’s good to be the King of the World

DB here:

Every spring the National Organization of Theatre Owners holds a convention and trade show in Las Vegas. It’s now called CinemaCon, but in earlier times it was known as ShoWest. The gathering assembles thousands of exhibitors from around the world. Directors and stars show up to publicize summer and fall releases. There are screenings, award ceremonies, display booths, and panels about everything from sound systems to popcorn pricing.

The convention is always an extravaganza, but in 2005 things were particularly stirring. Then fewer than a hundred US screens were digital. To ShoWest 2005 came three of the most financially successful directors in history: George Lucas, James Cameron, and Robert Zemeckis. Robert Rodriguez joined them, and Peter Jackson participated in a prerecorded video clip. Their mission: to sell digital cinema.

Battle angels

James Cameron and George Lucas at CinemaCon 2011.

Cameron and company knew that the exhibitors needed a rationale for switching that would actually enhance their business. The killer app for digital screening, these directors and others had decided, was 3D.

Lucas claimed that he was hoping to re-release the first Star Wars in 3D in 2007. “We’re giving you two years,” he said pleasantly. Zemeckis announced two 3D films in preparation. In a 3D film clip, Jackson said, “I’m looking forward to one day seeing Hobbits in 3D.” Cameron, who had started working with 3D back in the 1990s, was fresh off the January release of Aliens of the Deep in IMAX 3D. He promised the exhibitors Battle Angel, telling Lucas, “You can have all my theatres when Battle Angel moves out.”

One argument was that 3D offered a way to build the business. 3D screenings would bring in new audiences who seldom went to ordinary movies. More important, the enhanced format would justify higher ticket prices. But of course 3D would necessitate moving to digital projection.

No Battle Angel and no Star Wars IV showed up in 3D, but the celebrity directors kept their word to some extent. Zemeckis led the pack with Beowulf (2007), and Avatar (2009) cemented the deal. With its record $2.7 billion worldwide box office, the latter convinced exhibitors that digital and 3D could be huge moneymakers. In 2009, about 16,000 theatres worldwide were digital; in 2010, after Avatar, the number jumped to 36,000. 3D was the killer app, or Trojan Horse, that pressured exhibitors into going digital.

But here’s the funny thing. At the 2005 confab, the directors summoned up an explanation that goes back to the days when TV threatened the movie trade: You need something special to yank viewers off their couches. In 1953, the bonus was widescreen color images and stereo sound. In 2005, the bonus was stereoscopic projection. All tentpole pictures, Cameron claimed, would be in 3D. “With digital 3D,” he said, “we now have a reason to get people out of their houses from in front of their flatscreen, high-definition TVs and back to the movies.” The premise was that 3D wouldn’t be feasible at home.

Now let’s jump ahead. It’s the 2011 conference of the National Association of Broadcasters. 3D TV is starting to arrive. Celebrity director James Cameron visits with his business partner Vince Case, who have formed the Cameron Pace Group. According to Variety his message to the TV people is:

Your business is about to go 3D. . . . [He said that] the transition to 3D televison as going to happen much faster than usually predicted, even as soon as five years [when] “everything is in 3D and people demand 3D the way people used to demand color, and if you’re not broadcasting in 3D you’re not playing the game and you’re not getting any revenue.”

In 2005 Cameron told filmmakers and exhibitors to shoot in 3D to outrun television. Six years later, when nearly half of movie screens are digital, he advised broadcasters to adopt 3D as fast as possible.

It’s probably not irrelevant that the Cameron Pace Group supplies 3D cameras and assistance to both filmmakers and TV production companies. During the following year, the group announced, it was a 3D equipment provider for CBS Sports and ESPN.

Lest Cameron’s message be missed, he and Pace reiterated it earlier this month. At NAB’s convention he said that sports was only the beginning. Episodic television can also be shot quickly in 3D and easily converted to 2D. Television can’t confine itself to one-off shows or a 3D channel: “We have to hit a critical mass of enough entertainment in 3D.” “The future of 3D,” he told an interviewer, “will be defined by TV.”

Leapfrog

James Cameron and Vincent Pace.

Where does this leave film? Having convinced exhibitors to go digital and to install 3D rigs in their booths, what does Cameron propose to offset the rise of 3D TV? He came to last year’s CinemaCon with a new “incentive”—now all stick and no carrot.

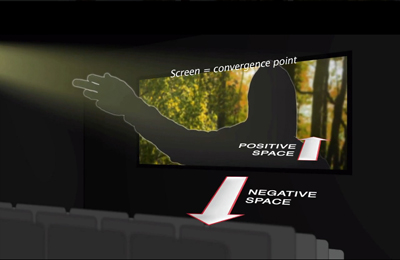

It’s well known that one problem with 3D cinema is a dimmer image. If a vibrant 2D film image is about 16 foot-lamberts, many 3D films are shown at less than four. This turned out to be a problem with screenings of Avatar, which in some venues ran at two foot-lamberts. So Cameron is proposing that exhibitors fit their projectors with gear that permits higher frame rates. Shooting and showing at 48 frames per second (or even 60 fps) instead of the traditional 24 will yield a brighter, sharper picture. Interestingly, 3D TV doesn’t have the same problem with light output, so it’s possible, notes Steven Poster of the ASC, that a 3D HD image would have whiter whites and blacker blacks than a 3D film screening.

Moreover, Cameron prepared a demonstration that showed that in 3D, figure movement and camera movement strobe noticeably at the 24fps rate. They look much smoother at 48fps. This is probably true, but I haven’t noticed problems of strobing in 35mm films by Mizoguchi, Jancsó, Welles, Renoir, and other camera-movement masters. Since they didn’t use our modern 3D, they didn’t encounter the artifacts that Cameron and his peers now brood over.

Having pressured exhibitors to go digital and 3D, Cameron is now asking them to change their equipment to permit him to shoot in a new way he likes better—and to compensate for a deficiency in the 3D system he thrust on them. But he assures them that revamping their projectors is merely a matter of “little tweaks . . . tiny things that make it better.” He has claimed it’s a matter of a software upgrade.

This holds good, evidently, only for the projectors made since January 2010, the so-called “second” series. Projectors made earlier may need replacing. Moreover, one report suggests that the projectors using the Texas Instruments system, the dominant technology in the field, will require not only new software but a new media block. Christie, a major projector manufacturer, says that it will have these available in June for $10,000 apiece.

You have to give Cameron credit for chutzpah. Once more he trots out the argument that theatres have to leapfrog home viewing:

With theatre owners already worried that audiences are abandoning the cinema for the comforts of their home entertainment centers, Cameron argued that exhibitors cannot afford to make the case that “What you’re going to see is special and better than what you have in your home, except the motion sucks.”

The message seems clear. Digital and 3D gave you a competitive advantage for a couple of years, but now it’s time to retool. Those of you who didn’t get 3D along with digital, better start moving, especially if you want Avatar 2 and 3. (Just what Lucas said in 2005 about Star Wars IV 3D, which still awaits us.) And upgrade to 48fps, or even 60. Cameron’s message got support in this year’s NATO convention, when Peter Jackson announced that he’d be trying to induce some theatres to play The Hobbit at 48 fps, the rate at which he’s shooting that 3D production.

Who died and made you King of the World?

I’m left with two observations.

First, there was a time when exhibitors called these directors’ bluff. When Lucas griped that there weren’t enough digital screens for Star Wars: Episode III—Revenge of the Sith (2005), John Fithian, president of the National Organization of Theater Owners, replied memorably: “I don’t put projectors in just for Star Wars.”

Now, it seems, the exhibitors are so scared of missing the next blockbuster that the filmmakers can dictate terms. It’s remarkable that these men can do something neither Griffith nor DeMille nor Disney nor any other powerful Hollywood filmmaker of the classic years dared do. They keep asking that the fundamental technology of cinema be changed so we can all watch a couple of their movies for a month or two every few years.

Second, if these guys are so passionately committed to quality, why don’t they make better movies?

For accounts of Cameron’s 3D explorations before Avatar see Christopher Probst, “Future Shock,” American Cinematographer 77, 8 (August 1996), 38-44; Ron Magid, “Digitizing the Third Dimension,” AC 77, 8 (August 1996), 45-50; Jay Holben. “Taking the Plunge,” AC 84, 7 (July 2003), 58-71; and John Calhoun, “Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea,” AC 86, 3 (March 2005), 58-69.

According to Cameron, he and Vincent Pace, an expert in underwater cinematography, have been working together since 1988. They began building an HD and 3D system in 1999 and finished their first one in 2000. See the GigaOM interview here. In the same interview Cameron mulls over the prospect of 4K television transmission.

A video showing Cameron’s ideas about digital cinema is available at Filmofilia.

As many have pointed out, higher frame rates were argued long ago for film screenings, notably by Doug Trumbull and Dean Goodhill. (See also Roger Ebert on Goodhill’s Maxivision.) Needless to say, Eastman Kodak enthusiastically supported this initiative, since it would step up film consumption.

This entry is a pendant to the series, Pandora’s Digital Box, which ran on this site earlier this year. That series, reorganized and expanded with new material and arguments, will be available in e-book form later this spring.

Avatar.

New Zealand is still Middle-earth: A summary of the Hobbit crisis

Richard Taylor during the October 20 anti-boycott march.

Kristin here:

Ordinarily I post about Peter Jackson’s Tolkien-adapted films on my other blog, The Frodo Franchise. But over the past five weeks a dramatic series of events has played out in New Zealand in regard to the Hobbit production. Those events tell us interesting things about today’s global filmmaking environment. As countries around the world create sophisticated filmmaking infrastructures, complete with post-production facilities, they are creating a competitive climate. Government agencies woo producers of big-budget films by offering tax rebates and other monetary and material incentives. Usually such negotiations go on behind closed doors, but the recent struggle over The Hobbit was played out more publicly.

Back in late September, the progress of Jackson’s project seemed slow. We Hobbit-watchers were mainly fretting over the lack of a greenlight for the two-part film “prequel” to The Lord of the Rings.

Of course, Tolkien’s LOTR (1954-55) was a sequel to The Hobbit (1937), but the films will have been made in reverse order. That’s due to MGM’s having the distribution rights back in 1995 when Peter Jackson went looking to use Tolkien’s novels to show off Weta Digital’s fancy new CGI abilities. Miramax bought the LOTR production and distribution rights and the Hobbit production rights.

Most of the news I was then blogging about related to MGM’s financial problems and how they would be resolved. Would Spyglass semi-merge with the ailing studio, convert its nearly $4 billion in debt into equity for its creditors, and bring it back into a position to uphold its half of the Hobbit co-production/co-distribution deal with New Line? Or would Carl Icahn push through his scheme to merge Lionsgate and MGM? The answer, by the way, came just this Friday, October 29, when the 100+ creditors voted to accept the Spyglass deal. I have been saying all along that the MGM situation was not the primary sticking point that was delaying the greenlight, even though most media reports and fan-site discussions assumed that it was. The greenlight having been given before this past week’s vote, I assume I was right. The real reason for the delay has not been revealed.

Meanwhile, other websites were speculating about casting rumors. Would Martin Freeman really play Bilbo, or were his other commitments going to interfere? (He will play Bilbo. Good choice, in my opinion. The man looks just like a hobbit.)

Then, on September 25 came the news that international actors’ unions were telling their members not to accept parts in The Hobbit. There was a boycott. The result was a maelstrom of events for the past five weeks or so. You may have heard about some of them. There were meetings and petitions. When Warner Bros. threatened to take the film to a different country, pro-Hobbit rallies followed. A visit by some high-up New Line and WB execs and lawyers to New Zealand led to hurried legislation to change the labor laws to reassure the studios that a strike wouldn’t happen. Finally, the government ended up raising the tax rebates for the production. Result: The Hobbit will be made in New Zealand after all. New Line, by the way, was folded into Warner Bros. by their parent company, Time Warner, after The Golden Compass failed at the box office. It remains a production unit but no longer does its own distribution, DVDs, etc.

The news that followed the launch of the boycott has come thick and fast, often involving misinformation. It was complicated, centering on an ambiguity in New Zealand labor laws as applied to actors and on a strange alliance between Kiwi and Australian unions. One of the biggest American film studios decided to use the occasion to demand more monetary incentives from the New Zealand government. I tried to keep up with all this and ended up posting 110 entries on the subject. (In this I was helped mightily by loyal readers who sent me links. Special thanks to eagle-eyed Paul Pereira.) That was out of 144 total entries from September 25 to now. There was plenty of other news to report. During all this, the MGM financial crisis was creeping toward its resolution, firm casting decisions were finally being announced, and the film finally got its greenlight. Whew!

For those who are interested in The Hobbit and the film industry in general but don’t want to slog through my blow-by-blow coverage, I’m offering a summary here, along with some thoughts on the implications of these events. Those who want the whole story can start with the link in the next paragraph and work your way forward. Obviously the links below don’t include all 110 entries.

In some cases the dates of my entries don’t mesh with those of the items I link to, given that New Zealand is one day ahead. I’ve indicated which side of the international dateline I’m talking about in cases where it matters.

September 25: Variety announces that the International Federation of Actors (an umbrella group of seven unions, including the Screen Actors Guild) is instructing its members not to accept roles in The Hobbit and to notify their union if they are offered one.

At that point, the film had not yet been greenlit, so it wasn’t clear how this would affect the production. The action against The Hobbit originated with the Australian union MEAA (Media Entertainment & Arts Alliance) and its director, Simon Whipp. Because relatively few actors in New Zealand are members of New Zealand Actors Equity, that small union is allied with the MEAA. The main goals of the union’s efforts were to secure residuals and job security for actors. The MEAA maintained that Ian McKellen (Gandalf), Cate Blanchett (Galadriel), and Hugo Weaving (Elrond) all supported the boycott; so far no evidence for this has been offered. Possibly they agreed to abide by it but were not in favor of it. Given the lack of a greenlight, none had been offered a role yet.

The main bone of contention has been a distinction made in labor laws in New Zealand. Actors are considered to be equivalent to contractors rather than employees, since they are hired on a temporary basis; it is illegal for a company to enter into negotiations with a union representing contractors. On that basis, Peter Jackson, who was first contacted in mid-August, refused to meet with the group. Besides, he isn’t the producer hiring the actors. Warner Bros., through New Line, is. As with all significant films, a separate production company, belonging to New Line, has been set up to make The Hobbit. It’s called 3 Foot 7. (The LOTR production company was 3 Foot 6, the average height of a hobbit being 3’6″.)

September 27. Peter Jackson responded angrily to the boycott, laying out the issues that would ultimately guide the New Zealand government’s response to the crisis:

“I can’t see beyond the ugly spectre of an Australian bully-boy using what he perceives as his weak Kiwi cousins to gain a foothold in this country’s film industry. They want greater  membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

membership, since they get to increase their bank balance.

“I feel growing anger at the way this tiny minority is endangering a project that hundreds of people have worked on over the last two years, and the thousands about to be employed for the next four years, [and] the hundreds of millions of Warner Brothers dollars that is about to be spent in our economy.”

Losing The Hobbit would leave New Zealand “humiliated on the world stage” and “Warners would take a financial hit that would cause other studios to steer clear of New Zealand”, Jackson said.

“If The Hobbit goes east [East Europe in fact], look forward to a long, dry, big-budget movie drought in this country. We have done better in recent years with attracting overseas movies and the Australians would like a greater slice of the pie, which begins with them using The Hobbit to gain control of our film industry.”

Various people and organizations in New Zealand soon line up behind one side or the other. Those siding with Jackson include Film New Zealand (which promotes filmmaking by foreign countries in New Zealand) and SPADA (the Screen Production and Development Association) and eventually the government. On the unions’ side is the Council of Trade Unions.

September 28. New Line, Warner Bros., and MGM weigh in with a statement that ups the ante. It dismisses the MEAA’s claims as “baseless and unfair to Peter Jackson” and continues:

To classify the production as “non-union” is inaccurate. The cast and crew are being engaged under collective bargaining agreements where applicable and we are mindful of the rights of those individuals pursuant to those agreements. And while we have previously worked with MEAA, an Australian union now seeking to represent actors in New Zealand, the fact remains that there cannot be any collective bargaining with MEAA on this New Zealand production, for to do so would expose the production to liability and sanctions under New Zealand law. This legal prohibition has been explained to MEAA. We are disappointed that MEAA has nonetheless continued to pursue this course of action.

Motion picture production requires the certainty that a production can reasonably proceed without disruption and it is our general policy to avoid filming in locations where there is potential for work force uncertainty or other forms of instability. As such, we are exploring all alternative options in order to protect our business interests.

Thus the specter of the production being not only delayed but also taken to another country is raised, and the implications of such a threat will gradually force the government to take measures to prevent that happening.

Peter Jackson also makes a statement to the Wellington newspaper that the Hobbit production might move to Eastern Europe. (The next day he reveals that WB is considering six countries for it.)

That night, a group of 200 actors met in Auckland, issuing a statement again asking the producers to meet for negotiations.

October 1. Jackson and WB voluntarily offer a form of residuals to Hobbit actors:

Sir Peter Jackson said New Zealand actors who did not belong to the United States-based Screen Actors’ Guild had never before received residuals – a form of profit participation. Warner Brothers had agreed to provide money for New Zealand actors to share in the proceeds from the Hobbit films.

It would be worth “very real money” to New Zealand actors. “We are proud that it’s being introduced on our movie. The level of residuals is better than a similar scheme in Canada, and is much the same as the UK residual scheme. It is not quite as much as the SAG rate.”

After much speculation, an announcement is made that Peter Jackson will definitely direct the film (which Guillermo del Toro had exited in May).

At about this time members of the filmmaking community begin campaigning actively against the boycott. An anti-boycott petition for New Zealand filmmakers and persons indirectly related to production to sign goes online; it ends with 3275 people having endorsed it.

October 15. The Hobbit is greenlit, but the possibility of moving the production out of New Zealand remains. Actors who have already been auditioned begin to be officially cast.

October 20. Actors Equity NZ is due to meet in Wellington. Richard Taylor (head of Weta Workshop) calls for a protest march. The actors’ meeting is called off due, the union says, to the “angry mob” that results. (Videos and photos posted online show a lengthy line of people walking through the streets in a peaceful fashion; that’s Richard talking to the press in the photo at the top. A person less likely to incite a “mob” to anger I cannot imagine.) An actors’ meeting scheduled for the next day in Auckland is also called off, putatively for the same reason, though no protest event had been planned there.

The turning-point day

October 21 (NZ). Jackson and his partner Fran Walsh issue a statement that implies that Warner Bros. has decided to move The Hobbit elsewhere:

“Next week Warners are coming down to New Zealand to make arrangements to move the production offshore. It appears we cannot make films in our own country even when substantial financing is available.”

Helen Kelly, president of the Council of Trade Unions calls Jackson “a spoiled little brat” on national television, helping turn the public against her cause.

Fran Walsh hints during a radio interview that WB might move The Hobbit to Pinewood Studios in England (where the Harry Potter films have been shot).

Prime Minister John Key says he hopes the production can be kept in New Zealand. Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee says he will meet with the WB delegation.

The international actors’ boycott against The Hobbit is called off.

October 21 (U.S.)/22 (NZ). WB is still considering moving the production, saying it has no guarantee that the actors will not go on strike. Key suggests that the labor law might be changed to provide that guarantee. The proposed legislation soon will become known as the “Hobbit bill.”

The Wall Street Journal suggests that a slight slip in the value of the New Zealand dollars against the American dollar is partly due to uncertainties about whether The Hobbit production will stay in the country.

WB announces the casting of Martin Freeman as Bilbo, plus several actors chosen as dwarves.

Bilbo Baggins by Tolkien and Martin Freeman, Bilbo-to-be.

A “positive rally” to convince WB to keep the production in New Zealand is announced. This eventually results in individual rallies in several cities and towns on October 25.

( U.S. time) Variety reports that unnamed sources within WB have said the studio is inclining toward keeping the production in New Zealand. This is the only hint of positive news from inside WB that comes out during the entire process.

Over the next few days, much finger-pointing takes place. Figures concerning the potential loss to NZ tourism if the film goes elsewhere are released. Helen Kelly apologizes for her “brat” remark.

October 25 (NZ). The WB delegation of 10 executives and lawyers arrive in Wellington. The pro-Hobbit rallies take place.

Pro-Hobbit rally in Wellington (Marty Melville/Getty Images).

October 26. News breaks that if The Hobbit is sent to another country, the post-production work (originally intended for Weta Digital and Park Road Post, companies belonging to Jackson and his colleagues) could take place outside New Zealand.

The WB delegation arrives at the prime minister’s residence in a fleet of silver BMWs. After the meeting ends, Key puts the chances of retaining the production at 50-50. He reiterates that the labor law might be changed.

Photo: NZPA

Presumably at this meeting, WB also puts forward a demand for higher tax rebates or other incentives; other countries it has been considering have more generous terms. Ireland has offered 28%, while New Zealand’s Large Budget Screen Production Grant scheme offers only 15%. This demand is not made public until later. During Key’s speech after the meeting, however, he mentions the possibility of higher incentives, but says the government cannot match 28%.

Editorials soon appear attacking the idea of changing a law at the behest of a foreign company.

The government’s deal with Warner Bros.

October 27. The New Zealand dollar again slips in relation to the American dollar, again attributed to uncertainty about The Hobbit.

Key and other government officials meet again with the WB delegation. The legal problem has been resolved to both sides’ satisfaction, but WB is holding out for higher incentives.

In the evening, Key announces that an agreement has been reached and the Hobbit production will stay in New Zealand:

As part of the deal to keep production of the “The Hobbit” in New Zealand, the government will introduce new legislation on Thursday to clarify the difference between an employee and a contractor, Mr. Key said during a news conference in Wellington, adding that the change would affect only the film industry.

In addition, Mr. Key said the country would offset $10 million of Warner’s marketing costs as the government agreed to a joint venture with the studio to promote New Zealand “on the world stage.”

He also announced an additional tax rebate for the films, saying Warner Brothers would be eligible for as much as $7.5 million extra per picture, depending on the success of the films. New Zealand already offers a 15 percent rebate on money spent on the production of major movies.

(The figure for the government’s contribution to marketing costs is later given as $13 million.)

October 28 (NZ). Peter Jackson returns to work on pre-production, which his spokesperson says has been delayed by five weeks as a result of the boycott. Principal photography is expected to begin in February, 2011, as had been announced when the film was greenlit. (The two parts are due out in December 2012 and December 2013.)

The Stone Street Studios. The huge soundstage built after LOTR is at the left; the former headquarters of 3 Foot 6 at the upper left.

In Parliament, a vote to rush through consideration of the “Hobbit bill” passes, and debate continues until 10 pm.

October 29 (NZ). The “Hobbit bill” passes in Parliament by a vote of 66 to 50, thus fulfilling the governments offer to WB and ensuring that The Hobbit would stay in New Zealand. It was known in advance that Key had enough votes going into the debate to carry the legislation.

It is revealed that James Cameron has been in talks with Weta to make the two sequels to Avatar in New Zealand. (Avatar itself was partly shot in New Zealand, with the bulk of the special effects being done there.) The timing has nothing to do with the Hobbit-boycott crisis. The two films are due to follow The Hobbit, with releases in December 2014 and December 2015.

October 30 (NZ). It is announced that the Hobbiton set on a farm outside Matamata will be built as a permanent fixture to act as a tourist attraction. (The same set, used for LOTR, was dismantled after filming, leaving only blank white facades where the hobbit-holes had been; nevertheless the farm has attracted thousands of tourists. See below.) Warner Bros. had been persuaded by the New Zealand government to permit this, though whether this was part of the agreement made with the studio’s delegation is not clear. I suspect it was.

It is also announced that the extended coverage of the 15% tax rebates specified in the “Hobbit bill” will apply to other films from abroad made in New Zealand—but only those with budgets of $150 million or more. (Presumably in New Zealand dollars.)

A remarkable outcome

In a way, it is amazing that a film production, even a huge one like The Hobbit, virtually guaranteed to be a pair of hits, could influence the law of a country–and make the legal process happen so quickly. Yet given the ways countries and even states within the USA compete with each other to offer monetary incentives to film productions, in another way it is intriguing that such pressure is not exercised by powerful studios more often. In most cases, a production company simply weighs the advantages and chooses a country to shoot in. Maybe countries get into bidding wars to lure productions or maybe they just submit their proposals and hope for the best. Certainly the six other countries considered briefly by WB were quick to jump in with information about what they could offer the Hobbit production.

In the case of Warner Bros. and The Hobbit, everyone initially assumed that the two parts would be filmed in New Zealand, just as LOTR had been. Yet the actors’ unions created an opportunity. The boycott gave Warner Bros. the excuse to threaten to pull the film out of New Zealand. Meeting with top government officials, WB executives demanded assurance that a strike would not occur–and oh, by the way, we need higher monetary incentives. As a result, a compromise was reached, the incentives were expanded, and there was a happy ending for the many hundreds of filmmakers of various stripes who would otherwise have been out of work.

Although there is considerable bitterness among the actors’ union members and those who supported their efforts, many in New Zealand see the tactics of the MEAA as extremely misguided. Kiwi Jonathan King, the director of the comic horror film Black Sheep, sums it up:

But this was all precipitated by an equal or greater attack on our sovereignty: an aggressive action by an Australian-based union taken in the name of a number of our local actors, backed by the international acting unions (but not supported by a majority of NZ film workers), targeting The Hobbit, but with a view to establishing a ’standard’ contract across our whole industry. While the actors’ ambitions may be reasonable (though I’m not convinced they are in our tiny market and in these times of an embattled film business), the tactic of trying to leverage an attack on this huge production at its most precarious point to gain advantage over an entire industry was grotesquely cynical and heavy-handed, and, as I say, driven out of Australia. Imagine SAG dictating to Canadian producers how they may or may not make Canadian films!

Whether the deal was unwisely caused by a pushy Australian union is a matter for debate. Whether the New Zealand government unreasonably bowed down to a big American studio is as well. But the deal that the two parties reached is a remarkable one, perhaps indicative of the way the film industry works in this day of global filmmaking.

Warner Bros. gets more money and a more stable labor situation. What’s in it for New Zealand? First, the incentives for large-budget films from abroad to be made in the country are raised. This comes not through an increase in the tax-rebate rate but an expansion of what it covers:

The Government revealed this week that the new rules would mean up to $20 million in extra money for Warner Bros via tax rebates, on top of the estimated $50 million to $60 million under the old rules.

While the details of the Large Budget Screen Production Grant remain under wraps, Economic Development Minister Gerry Brownlee said it would effectively increase the incentives for large productions to come to New Zealand.

The grant is a 15 per cent tax rebate available on eligible domestic spending. At the moment a production could claim the rebate on screen development and pre-production spending, or post-production and visual effects spending, but not both.

If the Government allowed both aspects to be eligible, it would be a large carrot to dangle in front of movie studios.

Mr Brownlee was giving little away yesterday but said the broader rules would apply only to productions worth more than US$150 million ($200 million).

It would bridge the gap “in a small way” between what New Zealand offered and what other countries could offer.

During this period, it was claimed that WB had already spent around $100 million on pre-production on The Hobbit, which has been going on for well over a year now. That figure presumably is in New Zealand currency.

There are some in New Zealand who oppose “taxpayer dollars” going to Warner Bros. As has been pointed out–though apparently not absorbed by a lot of people–Warner Bros. will spend a lot of money in New Zealand and get some of it back. The money wouldn’t be in the government’s coffers if the film weren’t made in the country. It’s not tax-payers’ money that could somehow be spent on something else if the production went abroad.

Another advantage for the country is the permanent Hobbiton set, which will no doubt increase tourism. There are fans who have already taken two or three tours of LOTR locations and will no doubt start saving up to take another.

One item that didn’t get noticed much during the deluge of news is that one of the two parts will have its world premiere in New Zealand. That’ll probably happen in the wonderful and historic Embassy theater, which was refurbished for the world premiere of The Return of the King. It was estimated that the influx of tourists and journalists for that event brought NZ$7 million to the city of Wellington. About $25 million in free publicity was provided by the international media coverage.

The Embassy in October 2003, being prepared for the Return of the King world premiere.

The deal also essentially makes the government of New Zealand into a brand partner with New Line to provide mutual publicity for The Hobbit. As I describe in Chapter 10 of The Frodo Franchise, the government used LOTR to “rebrand” the entire country. It worked spectacularly well and had a ripple effect through many sectors of society outside filmmaking. The country came to be known more for its beauty, its creativity, and its technical innovations than for its 40 million sheep. Now in the deal over The Hobbit, the government has committed to providing NZ$13 million for WB’s publicity campaign. But the money will also go to draw business and tourists. As TVNZ reported:

But the Prime Minister says for the other $13 million in marketing subsidies, the country’s tourism industry gets plenty in return.

“Warner Brothers has never done this before so they were reluctant participants, but we argued strongly,” Key said.

Every DVD and download of The Hobbit will also feature a Jackson-directed video promoting New Zealand as a tourist and filmmaking destination.

Graeme Mason of the New Zealand Film Commission says the promotional video will be invaluable.

“As someone who’s worked internationally for most of my life, you can’t quantify how much that is worth. That’s advertising you simply could not buy.”

If the first Hobbit film is as popular as the last Lord of the Rings movie, the promotional video could feature on 50 million DVDs.

Suzanne Carter of Tourism New Zealand agrees having The Hobbit production here is a dream come true.

“The opportunity to showcase New Zealand internationally both on the screen and now in living rooms around the world is a dream come true,” Carter said.

Marketing expert Paul Sinclair says the $13 million subsidy works out at 26 cents a DVD.

“It’s a bargain. It is gold literally for New Zealand, for brand New Zealand,” he said.

It’s not clear how the promotional partnership will be handled. There was a similar, if smaller partnership when LOTR was made. New Line permitted Investment New Zealand, Tourism New Zealand, the New Zealand Film Commission, and Film New Zealand to use the phrase, “New Zealand, Home of Middle-earth” without paying a licensing fee. (Air New Zealand was an actual brand partner during the LOTR years.) But for the government to actually underwrite the studio’s promotional campaign may entail more. That deal is more like the traditional brand partnership, where the partner agrees to pay for a certain amount of publicity costs in exchange for the right to use motifs from the film in its advertising. Has a whole country ever brand-partnered a film? I can’t think of one.

In my book I wrote that LOTR “can fairly claim to be one of the most historically significant films ever made.” That’s partly why I wrote the book, to trace its influences in almost every aspect of film making, marketing, and merchandising–as well as its impact on the tiny New Zealand film industry that existed before the trilogy came there. Years later, I still think that my claim about the trilogy’s influences was right. When an obscure art film from Chile or Iran carries a credit for digital color grading, it shows that the procedure, pioneered for LOTR, has become nearly ubiquitous. There are many other examples. The troubled lead-up to The Hobbit‘s production and the solutions found to its problems suggest that it will carry on in its predecessor’s fashion, having long-term consequences beyond boosting Warner Bros.’ bottom line. It will be interesting to see if other big studios announce they will film in one country and then find ways of maneuvering better terms by threatening to leave–or by actually leaving.

From Worldwide Hippies

Has 3-D already failed?

Kristin here–

Years ago, James Cameron announced that his upcoming film, Avatar, would only be released to theaters capable of showing it in 3-D. Since then, he has proselytized fervently at trade shows and fan cons, hoping that Avatar would be such a blockbuster that exhibitors would finally decide to make that expensive leap and invest to convert their auditoriums to add 3-D.

Many commentators seemed to assume that Cameron’s saying such a thing would make it so. Here’s what Popular Mechanics opined only a little over a year ago:

Cameron’s insistence on 3-D projection will likely force the industry to ramp up the installation of 3-D technology dramatically. “Cameron is going to be able to bully theaters into compliance,” says former Premiere magazine critic Glenn Kenny. “He’s got the clout, and he’s got the mojo to do it. Everybody is going to want his next film.”

Avatar will need about 4,000 screens for a 3-D-only release, estimates Doug Darrow, manager of DLP brand and marketing at Texas Instruments, which makes the chips that power theatrical 3-D projectors. Of course, once the Avatar-inspired infrastructure is in place, other 3-D-only releases will follow.

The problems with conversion are manifest. Number one is the expense. 3-D systems are digital, so first the theater owner must convert from 35mm projectors to digital. 3-D is an add-on system that entails additional expenditure. A digital conversion alone costs over $100,000, about five times the cost of a 35mm platter projector. Right now most “D” theaters have 2K projection, but 4K is gradually being introduced for both shooting and showing. (Che and District 9 were shot mostly on 4K.) What theater owner wants to buy an expensive projector that will be obsolete within a few years? And what was supposed to be the breakthrough year for 3-D sees us at what may be the bottom of a huge financial crisis. It has slowed down an already laggardly process.

Among commentators, there’s apparently a lot of support for Cameron’s position. This year, coverage of Avatar has been considerable and has mostly echoed his prediction that this is the future of cinema. Geeks who tend to love special-effects-heavy sci fi and fantasy films also tend to long for all of those films to be 3-D. Star Wars and The Lord of the Rings cannot be converted into 3-D fast enough for them. They run websites to express their fervor and to report every new technical innovation and every rumor about a future film perhaps being made in 3-D.

I’ll admit that the signs that 3-D is finally going to become a routine and frequent method for making and exhibiting films are clearer than ever this year. More theater chains are announcing conversion to digital projection after years of resistance. More films in 3-D, and good films, are appearing, like Coraline and Up. And I have to admit that I enjoyed Monsters vs. Aliens more than its tepid reviews had suggested I might.

But there are negative signs as well. Perhaps most notably, the major proponents of 3-D, after years of berating the exhibition wing of the industry for its slow adoption of digital and 3-D technology, are still berating it. Jeffrey Katzenberg, who had announced that all Dreamworks Animation features would henceforth be made in 3-D, is one such complainer. Cameron is another. As of now, roughly 320 of the U.K.’s 3600 screen are digital—which doesn’t entail that all have 3-D capacity. In the U.S. it’s 2500 out of 38,000.

These days, a major blockbuster may open on 4000 screens or more. Given Avatar’s massive budget, rumored at $237 million (not counting prints and advertising), Twentieth Century Fox couldn’t settle for showing only in 3-D, even if every properly equipped screen in the country showed it.

The recent theatrical free previews of scenes from Avatar in 3-D have renewed the claims that this approach is the future. Yet some commentators are cautious about that claim. The Guardian quotes Louise Tutt, deputy editor of Screen International: “It seems a little overambitious,” she says. “A little over-enthusiastic. I mean, take a film like 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days – who needs to see that in 3-D? So no, I don’t believe it will happen.” She sighs. “But then who am I to contradict James Cameron?”

Cameron is a mighty force for change, no doubt. The Abyss and Terminator 2 introduced the sort of morphing technology that made digital effects a reality. But oddly, there aren’t a lot of other directors quite that gung-ho about 3-D. They’re willing to praise it and suggest that they may make films in 3-D, but they don’t go around to trade shows pressuring exhibitors to convert their theaters.

Peter Jackson, for example, keeps hinting at such a possibility. Apparently his team is testing the new Red camera’s 3-D model with an eye to using it in the remake of The Dambusters. That’s slated to be produced by Jackson and directed by Christian Rivers. But if Jackson were as enthusiastic about the process as Cameron, wouldn’t The Lovely Bones be in 3-D? Steven Spielberg hasn’t been pushing 3-D, although there are rumors about the Tintin films being 3-D. But rumors and expressed interest don’t influence exhibitors reluctant to invest in upgrading theaters on the basis of the still-limited 3-D product that’s out there so far. Where’s Ridley Scott in this debate? Well, to be fair, he called the Avatar footage “phenomenal,” but I don’t see him making 3-D movies and demanding that they play only in properly equipped theaters. Where’s Tim Burton? Even George Lucas, Mr. Digital Technology, who keeps saying that Star Wars will be converted to 3-D, doesn’t have Cameron’s zeal.

Retro-fitting movies is hugely expensive, by the way. One of the few retro-fitted titles, Tim Burton’s The Nightmare before Christmas, has taken to returning annually, as if to remind us of that fact.

Even Pixar, which has said it will henceforth make all its films in 3-D, has been strangely low-key about its current project of re-doing the first two Toy Story films in 3-D and re-releasing them as a lead-up to the premiere of the third film, planned in 3D from the start. (This year the first two will be shown at the Venice film festival, which has added a 3-D prize.) Presumably they are content to provide both 3-D and 2-D prints.

We’re also not seeing a lot of directors in other countries clamoring for the option of making their movies in 3-D. Hollywood may dominate world cinema in terms of screen time occupied and tickets sold, but there are still thousands of movies made elsewhere each year.

There are still few enough theaters in the U.S. capable of showing 3-D movies that films end up with truncated runs. Coraline perhaps suffered most from being taken off screens while it still had commercial potential and before word of mouth had time to help it gain the audiences it deserved. The release of the partially 3-D Imax version of Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince was delayed by the fact that Transformers 2 was still occupying Imax theaters. I can’t help but wonder if there are some studio executives who look at this situation and, without announcing it to the world, decide that the films they’re about to greenlight will be made in 2-D. Plenty of those theaters to go around. (Well, not for all the independent films jostling each other in the market, but that’s another blog topic.)

Cameron has bowed to the inevitable and is allowing Avatar to play in both 3-D and 2-D theaters. It seems obvious that it will still take years before a film can go out into the world without 2-D 35mm prints being included in its distribution.

During those years, there’s the potential that 3-D will lose its luster for audiences. One of the main arguments always rolled out in favor of conversion is that theaters can charge more for 3-D screenings. Proportionately, theaters that show a film in 3-D will take in more at the box-office because they charge in the range of $3 more per ticket than do theaters offering the same title in a flat version.

But what happens when, say, half the films playing at any given time in a city are in 3-D? Will moviegoers decide that the $3 isn’t really worth it? Even now, would they pay $3 extra to see The Proposal or Julie & Julia in 3-D? The kinds of films that seem as if they call out for 3-D are far from being the only kinds people want to see. Films like these already make money on their own, unassisted by fancy technology.

Then there’s the fact that the extra $3 is not simply profit. There has to be an employee handing out the glasses, though sometimes the ticketseller does that. And those glasses in themselves cost money. Some will get damaged. When David and I saw Monsters vs. Aliens, there was a woman with a child, perhaps four years old, in front of us in the concession line. She handed both pairs of glasses to the kid while she dealt with paying for the refreshments. He had his fingers all over the lenses, of course.

If a theater is using the RealD 3-D system, it’s no big deal if kids with sticky fingers get hold of the glasses. They are so cheap as to be disposable, if the theater doesn’t want to bother collecting and re-using them. Problem is, the theater has to buy or rent a special silver screen to project on. The Dolby 3D system doesn’t require a special screen, but its glasses cost a whopping $50 apiece as of 2007. In Dolby theaters, you’ll find tense ushers waiting outside, making absolutely sure everyone returns theirs for washing and re-use.

[September 9: A Dolby representative informs me that the cost of the company’s glasses is currently $27.50, well as this information:

- The Dolby 3D glasses are high-performance, eco-friendly passive glasses that require no batteries or charging and can be reused hundreds of times without sacrificing image quality.

- The environmentally friendly and reusable glasses can be used repeatedly, significantly reducing the cost down to cents per pair per screening for exhibitors.

Thanks, Erin.]

No doubt 3-D enthusiasts would object that someday the system will be so routine that we’ll all have our own glasses and bring them along. That would cut the expenses to the theater, to be sure. But remember, different 3-D systems require different kinds of glasses. Are audiences willing to collect one of each and keep track of which they need to take along when they head for the theater—especially those $50 ones? (“Check the theaters listings, honey. Is it RealD or Dolby tonight?”) And there are more competitors entering the market, with their own glasses.

Is current audience enthusiasm permanent?

As usual, the studios take box-office figures to equal enthusiasm on the part of fans. In public, at least, they don’t speculate as to whether 3-D might again be, as it was in the 1950s, a mere fad or a specialized taste. But because spectators are willing to pay extra now because 3-D is still a novelty, does that mean they’ll maintain that attitude once 3-D is common?

Maybe not. And maybe even now not all filmgoers care. Some even dislike 3-D.

One vocal critic is Roger Ebert. His “D-Minus for 3-D” blog entry is an eloquent takedown of the technique on aesthetic grounds. He just doesn’t like watching movies in 3-D:

One vocal critic is Roger Ebert. His “D-Minus for 3-D” blog entry is an eloquent takedown of the technique on aesthetic grounds. He just doesn’t like watching movies in 3-D:

In my review of the 3-D “Journey to the Center of the Earth,” I wrote that I wished I had seen it in 2-D: “Since there’s that part of me with a certain weakness for movies like this, it’s possible I would have liked it more. It would have looked brighter and clearer, and the photography wouldn’t have been cluttered up with all the leaping and gnashing of teeth.” “Journey” will be released on 2-D on DVD, and I am actually planning to watch it that way, to see the movie inside the distracting technique. I expect to feel considerably more affection for it.

Ask yourself this question: Have you ever watched a 2-D movie and wished it were in 3-D? Remember that boulder rolling behind Indiana Jones in “Raiders of the Lost Ark?” Better in 3-D? No, it would have been worse. Would have been a tragedy.

He refutes the widespread argument in favor of realism:

There is a mistaken belief that 3-D is “realistic.” Not at all. In real life we perceive in three dimensions, yes, but we do not perceive parts of our vision dislodging themselves from the rest and leaping at us. Nor do such things, such as arrows, cannonballs or fists, move so slowly that we can perceive them actually in motion. If a cannonball approached that slowly, it would be rolling on the ground.

It’s true that the “coming at you!” effects in 3-D movies are disruptive. I remember the 3-D in Bwana Beowulf, excuse me, Beowulf primarily for those weapons thrusting out of the screen or the gratuitous overhead tracks past beams looking down toward the distant floor. More interesting, though, is that fact that although I saw Coraline and Up in 3-D, I remember them in 2-D. Those films didn’t throw spears at the spectator or otherwise seek to pierce that fourth wall with their props. Of course as I was watching, I noticed that the mise-en-scene had layers of depth and the figures a rounded look, but apparently my life-long movie habits filtered those aspects out as the films entered my memory. I look forward to seeing both films again on DVD, and given the fact that home-theater 3-D is still in its very early stages, I’ll probably see them flat. Fine with me.

Yes, Coraline was carefully designed with 3-D effects in mind, playing with skewed perspective to characterize the two worlds the heroine moves between. But as David showed by reproducing a frame here on our merely 2-D blog, the same motifs worked without the glasses. They’re quite similar, in fact, to the forced or distorted perspective used in German films of the 1920s.

We saw District 9 this week. No 3-D, and I for one am glad about that.

On August 26, TheOneRing.net, the premiere Tolkien site on the internet (for both novels and films), pointed to the current results of its ongoing poll. They asked, “Should the Hobbit films be in 3-D?” Many of the fans who frequent TORN do so because of the films. They have heard rumors over the years, mainly hints dropped by Peter Jackson, that The Hobbit might be made in 3-D. So what is their reaction as reflected by the poll? As of August 26, 55% say no, 13% say emphatically no (“Ugh … 3-D?”), 13% are sitting on the fence, and 13% say yes.

[Aug. 29: For some reason the poll “Should the Hobbit films be in 3-D?” has disappeared from TORN. It has been replaced by a discussion of the poll results on a discussion thread in the Message Boards.]

TORN subsequently checked with director Guillermo del Toro, who reassured them, “I can safely say that, as of this moment, there are absolutely NO conversations about doing the HOBBIT films in 3D.”

Of course, my title, “Has 3-D already failed?” was meant to be provocative. Its answer depends on how one defines success. If you’re Jeffrey Katzenberg and want every theater in the world now showing 35mm films to convert to digital 3-D, then the answer is probably yes. That goal is unlikely to be met within the next few decades, by which time the equipment now being installed will almost certainly have been replaced by something else.

Right now, the big proliferation is in tiny personal screens, iPod Touches, cell phones, portable gaming devices. Will teenagers allow themselves to look dorky by sitting with 3-D glasses staring at their phones? 3-D has the effect of making films that won’t play well on the very devices that studio heads would love to see playing their movies. So far, it is a remarkably inadaptable technology to try and force on people whose movie-playing gadgets change every few years. The big break-through, home-video 3-D, is aimed at a machine that people are supposedly abandoning in favor of other screens. 3-D movies on your computer? So much for inviting pals over for a sociable evening of popcorn and a movie in your impressive home theater.

Maybe Hollywood will forge ahead, despite all the obstacles I’ve mentioned. But it also seems possible that the powers that be will decide that 3-D has reached a saturation point, or nearly so. 3-D films are now a regular but very minority product in Hollywood. They justify their existence by bringing in more at the box-office than do 2-D versions of the same films. Maybe the films that wouldn’t really benefit from 3-D, like Julie & Julia, will continue to be made in 2-D. 3-D is an add-on to a digital projector, so theaters can remove it to show 2-D films. Or a multiplex might reserve two or three of its theaters for 3-D and use the rest for traditional screenings.

If that more modest goal is the one many Hollywood studios are aiming at, then no, 3-D hasn’t failed. But as for 3-D being the one technology that will “save” the movies from competition from games, iTunes, and TV, I remain skeptical. Given the banner year that Hollywood is having, I echo Daffy Duck in The Scarlet Pumpernickel when after his lover picks him up and, crying “Save me,” races from her forced marriage, he says,“So what’s to save?”

[September 17: On the occasion of the 3D Entertainment Summit, Variety has posted an article on the subject. It deals mainly with the losses of revenue from the fact that there are too many 3-D films jostling for too few equipped screens, saying that the format “is in danger of becoming a victim of its own success.”]