Archive for the 'Film genres' Category

Figuring out MEN

Men (2022).

In an earlier entry I considered films identified as “prestige horror” and traced how the idea developed among critics and journalists in the mid-2010s. That entry was written just after I saw The Northman, Robert Eggers’ next film after The Lighthouse; it was also the first of four films being released this year and early next year, each directed by one of the four directors generally identified with the trend.

Now Alex Garland’s Men has quietly come and gone, at least in theaters. I write this a few days after distributor A24 showed a double feature of Men and Ex Machina, available for one day only, on their occasional “Screening Room” streaming series, which was launched in response to the pandemic with Minari on February 12, 2021.

Seeing Men a second time made it possible for me to take notes and get a better grasp on the complex and oblique narrative of the film. That narrative has apparently perplexed most critics and audiences, resulting in considerable annoyance. I could follow it reasonably well, and I understood what happened at the end on first viewing–a particularly annoying section for the perplexed. This second viewing confirmed that I had been right about the ending, though I find that it was set up even more carefully than I had noticed.

At first I thought I should wait until Men arrived in a more conventional continuous streaming fashion. In preparing this entry, though, I learned that the DVD and Blu-ray release date has been announced as August 9. No subscription streaming date has been announced, although one can now buy the film from several providers for $19.99. Kudos to A24 for committing (so far) to bringing out all its films on physical media as well as streaming.

So my timing may not be too premature, but I realize that many will not have had a chance to see the film yet. I should emphasize that there are major spoilers ahead. I am going to reveal what happens at the end in some detail, as well as analyzing the imagery in the film and making a stab at what it’s all about.

Challenging films

Before I launch in, I would like to say something about highly unconventional films that defy our expectations. Increasingly I read adverse reviews of such films. They seem to have upset the writer by not turning out to be what he or she expected upon entering the theater. I first noticed this response in watching László Nemes’s Sunset (2018) for the first time. Within ten minutes I was baffled but excited at the prospect of what was obviously a masterpiece. Despite my puzzlement, I think I got the gist of it and certainly sensed what Nemes was doing stylistically. I was startled to read the professional reviewers’ mostly negative notices, seemingly based on annoyance at being puzzled. Having the chance to see Sunset a second time on a screener, I understood it better and wrote up an analysis of it.

I’ve seen this sort of thing happen occasionally since, notably with Leos Carax’s Annette last year. I don’t think it’s Carax’s best film or as challenging as Sunset or even Men, but it deserved better than it got from a lot of reviewers.

I would assume that the duty of anyone writing about a film for publication, particularly one who gets paid to do so, is not to judge a film by whether it conforms to the expectations he or she brought into theater. If a film is challenging in the way these examples are, the obvious strategy is to try and figure out what the film is trying to do. How and why is it puzzling or unconventional? I remember that one professional critic who shall remain nameless wrote that she wanted to like Annette but wasn’t able to. I would say that the critic’s duty is not to like or dislike a film. That’s the realm of buffs reviewing on Facebook or Google or wherever. The critic’s duty is to understand it, to figure it out, or at least to make the attempt. I realize that such films really need to be watched a second time to get a better grasp on their strangeness, but even on a first viewing one can usually discern that a second viewing is worthwhile, and why.

Of course, trying to figure a film out may lead one to conclude that it really is bad. Maybe it’s not experimenting in original ways or it’s using flashy style gratuitously. But if the viewer does figure it out and it’s good, even a masterpiece, he or she has discovered something–a process that I find rewarding and pleasurable, whether or not I ultimately don’t much like the film.

I’m not claiming that Men is an undying masterpiece, though I do admire it more than many do. The point is that a significant number of adverse reviews reflect the same sort of unwillingness to engage with the film’s unconventionality.

This unwillingness makes me wonder what happened to the sort of openness to originality and even occasional experimentation that existed from the late 1940s, for several decades, when such films as Voyage to Italy, Hiroshima mon amour, 8 1/2, Pickpocket, Persona, Death by Hanging, and other unconventional films of the golden age of art houses. Would such challenging films be hailed and become long-treasured classics? I hope so, but …

The final and only girl

Again, I’m not going to point to particular reviewers, but many have gone for the obvious and describe the film solely in terms of the misogynistic males. Are all men misogynistic?

I do think that the title was a big mistake, inevitably egging critics on to batten onto the toxic masculinity displayed by all the male characters as the the obvious, straightforward point of the film. In that case it would be pretty simple and overly obvious. I think the form and style of the film make it more complex than that. I suspect that critics thought of the film as a sort of social commentary first and a horror film second. This may be one of the disadvantages of prestige horror. To some extent the films can be seen as art cinema rather than regular horror pictures, and therefore ripe for interpretation rather than analysis as horror films. In fact they seem to be a combination of art and genre types.

But however arty, Men is a horror film. The villains of horror and especially slasher films tend to be grotesque, often wearing masks and wielding chainsaws and the like. It’s a well-established convention. From at least Psycho on, these villains are seen as madmen, deviants, not representatives of the traits of an entire gender. They are basically monsters, some endowed with supernatural traits, as are the male characters in Men.

In struggling to figure what Garland was up to in Men, about halfway through it dawned on me that he had neatly reversed the “final girl” plot. This common structure in the slasher sub-genre of horror films was formulated by Carol Clover in her Men, Women, and Chainsaws: Gender in the Modern Horror Film (1992). Her insights have become common currency in the field, with “final girl” having its own Wikipedia entry. A crazed killer picks off a group of victims, often a bunch of male and female teenagers, in a shooting-gallery narrative. Clover points out that typically only one, usually a girl or woman, manages to survive and kill the group’s nemesis.

Men does exactly the opposite. There is a set of male villains, mostly characterized as simply obnoxious at first and becoming increasingly dangerous until they are revealed as murderous, supernatural monsters. (Samuel’s incongruous blonde female mask may be a reference to those worn by such villains.) There is no group of victims, no final girl, just the only girl, who manages to wipe them all out.

Harper is, to be sure, initially seen as a victim, pursued by the Naked Man early on and ultimately by Geoffrey, who tries to run her down in her own car before crashing it. (None of the village men apart from Geoffrey and the little boy, Samuel, is given a name. “Naked Man” seems to be what people use for him.) She is terrified in many scenes and forced to retreat to her rented house, which proves inadequate to keep these guys out. Occasional shots of her in the house are seen through the large windows, as if from a lurking villain’s point of view–a common convention of slasher films.

At one point she is nearly defeated, declaring to her friend Riley that she will give up her vacation and leave, though she seems more angry than frightened. Riley urges her to stay, however, and Harper fights back–ultimately successfully.

I’m not sure Garland is the only filmmaker to create such a reversal of this widespread convention. David and I happened to watch Edgar Wright’s Last Night in Soho (2021) recently, and one might say that something vaguely similar is going on. Again one woman wreaks her revenge on a series of monstrous males. There may be other such films, but I think Men is a particularly original and clever example.

They don’t call it Mother Nature for nothing

I obviously haven’t been able to read all the reviews, professional and amateur, of Men. I’ve read quite few, though, and I have yet to find one that deals with the motif of nature in the film, though some refer to the Green Man motif. The gender politics are obvious, however one interprets them, but they are bound up with the treatment of the natural world in the film. It’s a combination that both make the film more complex and give some depth and originality to the treatment of the dreadful men.

The early parts of the film stress the beauty of the English countryside, a major factor in Harper’s search for a place to recover from the grief and guilt she feels in the wake of her husband’s suicide. She rents a luxurious country house for two weeks. Upon arriving, she plucks and eats an apple from a tree in the front yard. Geoffrey, the landlord, takes the occasion to pretend that there is a rule against “stealing” the apples, and after Harper confusedly apologizes, he reveals it was a joke–albeit a mildly cruel one that suggests he isn’t entirely the jovial if awkward fellow he seems at first.

In the morning she seems not to know what to do in the house, and in a long sequence she takes a walk that gradually undermines the sense of the bucolic, restful countryside.

Harper enters a forest, the beauty of which is emphasized by the lush cinematography. The exteriors in this part of the film are dominated by bright spring greens and occasional flowers.

At one point she pauses, staring down into a valley at a tree. There seems to be nothing remarkable about it, apart from perhaps the fact that some of its branches are entirely green because of a thick coating of moss–something that appears on other trees as well. Her pause should cue us to pay attention to the forest as a possibly significant motif. This imagery of moss-covered trees appears in a cutaway outside the house in a later scene.

As Harper walks along a path, a gentle rain begins, and she stands delightedly listening to distant thunder and the patter of the rain. The moment is a sample of how this contact with nature delights this city dweller and could have a calming effect on her. The freedom to commune with nature in safety, however, is soon to be taken from her.

Harper approaches a tunnel that is the setting for the most widely praised scene of the film, one that will change the direction of the action radically. Again it takes place amid bright green foliage, which creates a sharp contrast with the darkness of the tunnel. As she calls out and moves into the tunnels, singing to hear the repeated echoes (which she does not notice do not always match her voice exactly), a cut takes us deep into the tunnel, with the darkness swallowing up the green forest, almost like an iris-out.

Another reverse shows an even smaller spot of green as Harper sees the silhouette of a man at the other stand up and run toward her. As she flees through the forest, there is a mysterious shot of the pursuing man, unidentifiable in the unfocused depth, while a single fluffy white seed drifts past in focus in the foreground (see image at the top of “Challenging Films.”) This sort of seed will itself become a minor, and mysterious, motif.

Hurrying out of the forest, Harper pauses to photograph a deserted house and spots a naked man. He apparently is not the man who pursued her; from the glimpses we get of him, he appears to be clothed.

Harper returns home, and this scene puts an end to her hopes to take walks in the countryside, something she does not do again. The bright greens become far less prominent, and later scenes tend to take place at night.

The next morning the Naked Man walks around outside the house and tries to break in. The Constable and his partner (the only local woman in the film) arrest him. The scene makes the intruder both threatening and pathetic, with his grubby skin and open sores.

The Naked Man will become linked to a motif introduced in the next scene. Harper goes to visit the nearby village, planning to see the church and try the local pub. In the church there is a carving on the front of a marble font (top image): the Green Man, an ancient, widespread medieval pagan figure associated with rebirth. It faces Harper as she walks forward along the central aisle.

We then see what she does not. On the opposite side of the font, invisible from the pews, is a female figure, a Sheela na gig, a sort of traditional pagan counterpart to the Green Man. She is invariably a seated women with spread legs pulling open her exaggeratedly large vagina. Despite both being of pagan origin, these two mythical characters have been part of the decoration of many churches in Ireland, the United Kingdom, and Europe, and quite a few still survive.

The Sheela na gig figure is framed in the foreground as Harper sits weeping at the memory of her husband’s suicide and the local Vicar appears dimly in the background.

There follows a scene in which the Vicar pretends to comfort Harper, initially seeming sympathetic but then suggesting that her refusal to forgive her husband when he struck her drove him suicide. She leaves indignantly, while he sits stroking the bench where she had been sitting.

There follows an enigmatic scene in the forest with none of the characters present. In extreme close-up, a fuzzy seed drifts into the hollow eye-socket of a decaying deer. A cut that seems to follow it into darkness leads to a shot of the Sheela na gig relief. In the light of what happens later, we should keep in mind that this relief is on the surface facing away from the congregation and into the space occupied by the Vicar for all the time he has worked in this church.

The next shot shows the Green Man face, made, as such figures are, of foliage. A brief series of shots of the Naked Man in a strange sort of den or cell, culminating in a close-up in which he peels some skin from his forehead and sticks a leave into his raw flesh. The camera then rises slowly from the carcass of the deer.

This interlude has not been any character’s subjective vision or dream. It is part of the motivic commentary on the action of the film and will come to make sense later on.

Immediately after this scene comes Harper’s visit to the pub where she learns from the Constable that the Naked Man has been released. At that point she calls Riley, saying she is leaving. But her friend urges her to stay and says she will drive to join her in defying the aggressive village men (and boy).

That ending

The ending seems to baffle most viewers.

All of the male characters show up at the house. Most threatening is the Vicar, who corners Harper in the large bathroom and declares his lust for her. He describes her in lewd terms that are based on the Sheela na gig figure–open legs, cave-like vagina, and an open mouth.

After this series of threats and attacks by the main male characters, Harper tries to flee in her car. She fails when she hits Geoffrey, who steals the car and tries to run her down. She takes refuge, if one can put it that way, in the garden in front of the house as Geoffrey crashes her car into wall outside, cutting off that method of escape.

At that point the Naked Man, now fully transformed into a semblance of the Green Man, enters. Now finally covered with leaves and twigs, he resembles the figure carved in the church. He is not a genuine Green Man, however, not being made of vegetation but having pressed all these leaves and twigs into his body.

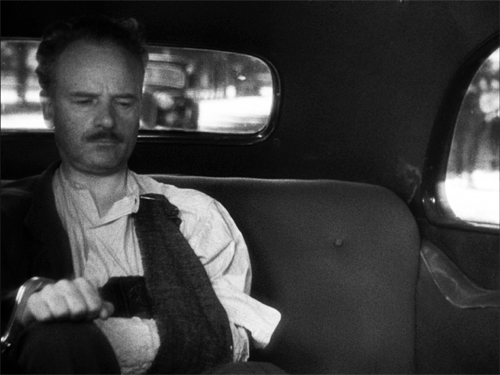

Launching an impressively intense foray into body horror, the Naked Man lies down and gives birth to Samuel, who kneels before Harper, his belly swelling (above) until he gives birth to the Vicar, who crawls feebly into the hallway as Harper turns away in contempt (frame atop the “Only Girl” section). He then gives birth to Geoffrey, who gives birth (or vomits?) Harper’s husband James through his mouth.

Unlike the others, James is not covered in blood and does not continue the male-birthing chain. He sits down and blames Harper for the injuries incurred during his suicide, which he still bears despite his “rebirth.” Nevertheless, he demands her love. She turns away, wearily sighing, “Yeah.” Cut to a large red title against black: MEN.

An epilogue follows immediately, with Riley arriving to find the door standing open and signs of bloody objects being dragged (see bottom). Ironically, she is revealed as pregnant, and the flowers return as she approaches the house (see bottom). She spots Harper sitting calmly on a stone stairway in the garden and joins her. The two women reunite happily.

That’s quite an ellipsis. What happened “during” the scene elided by the MEN title? It seemed obvious to me on first viewing that Harper killed James and any of the others who might still be living, though my impression is that each died after giving birth. What happened to the corpses? No idea. Maybe they magically disappeared, as they had magically arrived. After all, earlier we had seen two characters, the Constable and Geoffrey, instantly disappear into thin air. If that happened, why the bloodstains remain is a mystery. Still, one thing I was sure of: James and the others are all dead and gone.

How do we know this? The signals are clear, but one needs to watch carefully. Chekhov famously wrote several times in different variants that “If in the first act you have hung a pistol on the wall, then in the following one it should be fired. Otherwise don’t put it there.” The principal is known as “Chekhov’s gun.”

Garland follows this guideline and prepares for the final elided murder.

First, during the morning scene when Harper is working remotely and fails at first to notice the Naked Man outside, she goes to the kitchen and a close-up emphasizes her hand plucking one of three knives from a holder to cut an orange. Immediately afterward we see the Naked Man again as she resumes work, the orange beside her–reminding us that she does have a means of defense. He tries to come in, but she successfully locks the door and simply calls the police.

After Harper learns at the pub that the police have just given the Naked Man a bath and clothes and released him, she calls her friend Riley to report the various nasty encounters with the Vicar, Samuel, and the Constable. Riley offers to join her at the vacation house, adding, “If that fucking weirdo comes back, I’m gonna take that axe and chop his dick off, and he can fucking choke on it.”

Harper asks, “What axe?” and Riley says it’s behind her. As indeed it is. (The fireplace beside which it sits has been seen and mentioned already. Not that it’s ever lit, but it’s where the axe is.)

Now we’ve had two potentially deadly blades called to our attention. Knowing Chekhov’s rule, from this point on I was assuming Harper would use that axe in a climactic fight.

But since we don’t actually see the axe used with deadly force, Garland needs to show that she would kill someone with it if necessary. Hence the return of the knife.

At about sixty minutes in, the attacks on Harper in her house begin. The mysterious Constable who had released the Naked Man appears on the lawn and then vanishes instantly. Immediately one of the thugs from the pub tries to get into the house. Harper grabs the same knife and hides in the kitchen, where Samuel enters. She refuses to use it on a child, and when Geoffrey appears, she still trusts him. He pretends to search the garden before suddenly disappearing, as the Constable had done.

At that point the Naked Man returns and blows a handful of fluffy seeds into Harper’s face, seen from her POV. He has visibly made some progress toward turning himself into a Green Man.

The seeds seem to send Harper into a trance. She falls backward in slow motion and has a vision of herself possibly drowning. A quick montage of earlier scenes follows, but she recovers and manages again to slam and lock the door to keep him out.

At this point the Grand Guignol aspects of the action ramp up as the Naked Man sticks his arm through the mail slot and grabs Harper’s wrist. In a dramatic shot from below, she stabs his arm.

As Harper watches the Green Man withdraw his arm through the slot, its edges pull the knife through his forearm and hand, splitting them in two down the middle. (This horrendous wound is transferred to the other men who have harassed or endangered Harper.) Shortly thereafter, when the Vicar arrives (with the split arm), he accuses her of trying to control him with her carnal powers and nearly rapes her. She uses the knife again, this time to kill him.

By this point we should be thoroughly convinced that she would be equally capable of wielding an axe. Indeed, part of the suspense during the “rebirth” scene is when she will finally go and pick it up. She does so as Geoffrey “gives birth” to James. Garland emphasizes it with a low framing of it and the door through which James enters.

James collapses on the sofa, and Harper crosses to sit beside him. She doesn’t put down the axe, as we might expect her to do if she is considering admitting that she still loves him. It should be noted that he still has his broken leg (which is also shared with all the other males in the rebirth scene) and his other wounds from his suicide. He is not her real husband James but some simulacrum of a human, like the bloody monsters we have seen emerge during the rebirths. That has to be understood if we are to accept what is implied to happen next. In the last shot of the scene, Harper does not tell James she loves him or that she is sorry for having contributed to his suicide. She just sits fingering the blade of the axe. Cut to the “Men” title.

I think there’s no doubt that, unseen by us, that axe gets used. Chekhov was right. Clearly Garland, although he made us cheer on Harper as a strong woman, doesn’t want us to see her chopping up her husband, dead though he may actually be already, and we don’t want that either.

How hard is this to grasp when watching the film? Hard, maybe, but not impossible. Christen Warrington-Broxton posted a piece on Google’s page for amateur film reviews. She offers a cogent analysis of the film, including a response to those who claim that the final scene of the climax does not resolve the action. She points out that “our heroine is clearly calculating how she will dismantle that mess with the axe.” During the rebirth segment of the scene, “the modern woman walks away from the inevitable and pathetic rebirth of toxic masculinity that comes for her: the ex. She goes to wait to prepare herself emotionally, and physically with the weapon her female friend pointed out to her. She must destroy this presence in her life.” (Ms Warrington-Broxton also identifies the Sheela na gig, a figure I had not been aware of.)

Oddly enough, though, the Vanity Fair review presents a pretty cogent summary of the action and does not even speculate about what happened between James and Harper after that cut to the title. No mention of the axe or the possibility that violence occurred. Particularly odd for a piece entitled “Men: Let’s Unpack that Disturbing, Disgusting Ending.”

Finally, why bring in the Green Man and Sheela na gig imagery? What is the point of having all the males apart from James played by the same actor? Why make all the village males bear the same horrific wounds, even though only each wound was inflicted on only one man? And why do those wounds echo those of James as he lands impaled on an iron fence and with a grotesquely broken leg after his suicide jump? (Geoffrey suffers a similar leg wound when hit by Harper’s car.)

To be brief, Garland reverses the usual associations of the two mythical figures, who are generally regarded as positive forces–the Green Man as a emblem of rebirth and the Sheela na gig as a protector against evil and, not surprisingly, a fecundity symbol. The film presents them as grotesque and threatening or lewd. The males in the film are linked to them as if to the archaic beliefs, especially about women, of a long-gone time.

The similarities among the male villagers might simply be seen as a blanket condemnation of all men simply as misogynists. Since this is a horror film, however, the point is to make them all monstrous and grotesque in a similar way, sharing the atavistic instinct that drives their behavior toward Harper. The casting of Rory Kinnear as all of these men emphasizes this shared instinct. It also sets them apart from James, who is a classic domineering, guilt-tripping husband but not a literal monster until he joins in the chain of rebirth at the end.

Prestige horror going forward

The two films released since I wrote my first piece have not done well. As of July 18, Box Office Mojo listed Men as having earned $10,304,884, about three-quarters of which came from the North American market. The budget isn’t known, but it’s hard to imagine one so low that Men could come close to making a profit, even given that various forms of home-video are yet to come.

The Northman has been streaming for some time now, but again, with a budget estimated at $80-90 million, it does not look like a hit.

One thing is interesting to note, though. I pointed out in my first entry that the “prestige horror” films by the four directors discussed have all scored higher on Rotten Tomatoes among critics than among audiences. By contrast, more conventional horror films nearly always had higher marks from audiences than from critics. Men did worse on Rotten Tomatoes than any of the earlier prestige films listed in the previous entry had, with a 69% positive critical response and a 40% audience one. It’s quite a come-down, but the critics’ score fits the pattern by remaining higher. Last Night in Soho upheld my claim that more conventional horror films did better with audiences; it scored 76% with critics and 90% with viewers.

Whatever the outcome of Men‘s streaming life for A24’s bottom line, Garland apparently wants to quit directing and go back to writing. He has been saying this in interview after interview (too many to link–just Google “‘Alex Garland’ quitting directing,” and you’ll find pages of results). The first time was in an interview with the New York Times (behind a pay wall) on May 16, four days before the American release of Men. Thus the financial failure of the film was not the direct cause of this decision, but one cannot help but suspect he knew what was coming:

It’s the sort of movie that will leave people arguing about its intent, and about what it’s trying to say. You once told me that with “Ex Machina,” you wanted at least 50 percent of the film to be subject to the viewer’s interpretation.

Over the years, I have been consciously putting more and more into the hands of the viewer. There’s probably another element to it, too, if I’m honest, which is that it’s making the viewer complicit. This is another reason to pull back, because there’s a part of me which is really subversive and aggressive and is kind of [messing] with people. At times, I felt with “Men” that I’ve gone so far that it’s borderline delinquent.

The caption for the portrait of Garland atop the interview says that That could be discouraging, though if one makes a deliberately “subversive and aggressive film,” one shouldn’t be surprised.

In the wake of The Northman‘s release and financial disappointment, Eggers told interviewers that he was going to back off from epics on that scale and return to smaller films. In one conversation, he said, “I need to restrategize in terms of what I’m pitching to a studio. Like, how do I be me and survive in this environment? Because while they wouldn’t have me anyway, I wouldn’t want to direct a Marvel movie, and I’m also not going to try to get the rights to Spawn or something either.” This follows from what I wrote in my previous entry, that one interesting thing about these four directors is that none has followed the common pattern of using low-budget horror films as springboards to working in big franchises. Apparently this still holds. So far.

[August 6, 2024: Eggers latest film, Nosferatu, is most definitely in the horror genre; oddly, its American release by Focus is scheduled for Christmas day, 2024. An example of counterprogramming, I guess.]

Today the third “prestige horror” director’s film of the year, Jordan Peele’s Nope, goes into wide release. Box Office Mojo is predicting that “In all likelihood, Nope will become the top domestic grossing original film since the start of the pandemic.” That, added to the financial successes of Peele’s previous films, plus his links with Universal and Imax suggest that he may go in a different direction from the other three auteurs in this small group.

[July 24, 2022] I haven’t seen Nope yet, but Justin Chang’s positive review in the Los Angeles Times suggests that Peele remains true, at least for now, to prestige horror: “an unusually well-made and imaginative thriller that’s sometimes tripped up by its own high-mindedness.”

Ali Aster’s Disappointment Blvd., rumored to be a comic horror film in the region of four hours long, was announced as a 2022 release. Recently, however, that was put off until 2023, with possible hopes for a Cannes debut. We shall have to wait a while to see if the old gang is breaking up.

Film websites focusing on horror, fantasy, and/or sci fi tended to give Men far more positive notices. See, for example, Meagan Navarro’s piece on Bloody Disgusting, which catches the fertility imagery and the Grand Guignol quality of the ending, though she doesn’t mention the implication of what happens after the last shot of the climax.

A short time after my piece on Sunset was posted, a friend of ours in Hungary, who teaches and has many contacts in the film industry, told me that Nemes had asked him who this Kristin Thompson was. I assume our friend gave me a good report. I like to think that, among the many negative reviews, mine gave him some indication that he had accomplished what he intended in the film.

Rather to my surprise, Sunset is available for streaming on virtually every service that exists, Netflix, Amazon Prime, Hulu, etc. I hate to recommend seeing this beautiful widescreen film on a TV screen, but I suppose it’s better than nothing.

[August 6, 2024: Aster’s Disappointment Blvd. was renamed Beau Is Afraid (2023). Produced and distributed by A24, it was the studio’s most expensive film before Civil War; it did poorly at the box-office.]

Men (2022).

How did “prestige horror” come about?

Trailer, The Northman (2022).

Kristin here:

Ever since last August I have been venturing into our local multiplexes to see movies. Fully vaccinated, twice boosterized, wearing a mask, and attending weekday matinees in the company of maybe four to ten other people, I have felt safe. It’s great to see movies on the big screen again, and I’ve seen nearly twenty, starting with Annette in August and not counting the five I saw at the Wisconsin Film Festival.

The latest was The Northman, on April 25, a Monday. I had seen the trailer for it three or four times before I realized that it was by Robert Eggers, director of The Witch, which I liked well enough, and of The Lighthouse, which I admire very much.

Before the film there was the usual flood of trailers, including ones for Nope, Men, and The Black Telephone. It struck me as I watched them that despite the fact that I am not particularly fond of the horror genre, there I was, waiting to see a horror film–at least I’m classifying it as such under the rather casual criteria I’m using here. And if you doubt it’s a horror film, I present you with a frame of the character identified in the credits as the He Witch, holding the mummified head of Heimar the Fool. (The story is based on an ancient Scandinavian myth, the same one whence Hamlet was derived. This may be the equivalent of the Yorick scene.)

Not only was I there to see a horror film, but I was looking forward to seeing two of the three such films previewed: Jordan Peele’s Nope and Alex Garland’s Men. (Apparently these succinct titles are designed to avoid even the faintest whiff of a spoiler.) Later, musing on that confluence of horror films coming out this spring, it occurred to me that all three of these directors had concentrated exclusively on the genre in the features they have made so far–three apiece, coincidentally. And while all three had had some degree of critical, popular, and/or financial success, none of the directors has so far moved into the world of franchise blockbusters. It’s so common these days for indie directors to be swept from the world of low-budget art-house filmmaking to to heady heights of franchise series that I suspect one or more of the three have received nibbles from the studios.

One or more may eventually succumb to the blandishments that have attracted such indie directors as Taika Waititi, Guillermo del Toro, and Chloe Zhao into the world of Hollywood blockbusters. For now, though, it’s remarkable to find three directors with such similar careers in many ways who have stuck to the modest genre that brought them success when they probably had other options. It’s so common these days for an aspiring filmmaker to break into the industry with a low-budget horror film that becomes a hit and then immediately to be helming an epic with a budget distinctly into nine figures. (For a list of superhero-film directors who started in horror, see here; for a more general one of indie directors who jumped to blockbusters, here.)

There’s a fourth director who belongs with this group. I haven’t yet seen a trailer for Ari Aster’s Disappointment Blvd., which is being kept under wraps but is due out this year. It is described as a comic horror film. Gamerant has the fullest information on it that I’ve found. Excerpts:

Following the tradition of his previous movies, Aster will serve as both writer and director of Disappointment Blvd. While the movie is shrouded in mystery and doesn’t have a trailer yet, it will be a decades-spanning horror-comedy about a famously successful entrepreneur. And if Hereditary and Midsommar are anything to go by, it will be a genre-bending horror-comedy at that. In conversation with UC Santa Barbara students, Aster described Disappointment Blvd. as a 4-hour long “nightmare comedy,” though whether he was joking about its length remains to be seen.

A24 will distribute Disappointment Blvd. as well as co-produce it with Square Pegs: Ari Aster and producer Lars Knudsen’s production company. Disappointment Blvd. began production in June last year and is set for release later this year, though no official date has been given yet.

There is speculation that the movie will have its world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival due to take place from 17 to 28 May 2022. Fortunately, the festival announces its lineup on the 14th, so fans won’t have to wait long to find out.

Eggers, Peele, Garland, and Aster all unquestionably belong to a trend that has recently been given a name–in fact, two: “elevated horror” and “prestige horror.” Elevated horror as a concept began to gain currency after the release of Eggers’ first feature, The Witch, in 2015. I suspect that Garland’s Ex Machina, which came out in 2014, had something to do with that. Many would count it as science-fiction, but under my loose criteria here, it counts as horror–especially since Garland’s two subsequent films undeniably fall into the horror genre. Elevated horror, according to The Hollywood Reporter, is a treatment of films as quasi-art cinema, as well as a focus more on psychological dramas than gore.

I don’t care for the term “elevated horror,” since it could imply simply a ratcheting up of the level of horror included in the film. This is far from what these directors are doing, although The Northman has little interest in psychology and contains plenty of graphic dismemberment.

In recent years there has come to be a vituperative reaction against “elevated horror” among fans, who claim it implies that the rest of the genre is trivial, trash, whatever. I have no interest in the resulting debate, but google “elevated horror,” and you’ll find it.

The same basic debate simmers concerning the term “prestige horror,” with fans claiming that treating prestige as something new to horror films dismisses the many classics of the genre that have gained critical respect, awards, and status as classics. Yet The Exorcist, Rosemary’s Baby, Jaws, Children of Men, Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and others have been and remain well-respected. They have, in fact, prestige, as do the films of this younger group of filmmakers who have stuck to the horror genre. But the classics just listed were directed by people who worked in a variety of genres and did not stick to horror. I’ll use “prestige horror” here, since it seems to me to accurately describe what distinguishes the work of these four directors and other films (e.g., A Quiet Place, Saint Maud) from more conventional mainstream horror films. The term basically, I think, is a suggestion of something more respectable emerging from an era in which “torture porn” seemed to dominate the genre.

This entry doesn’t aim to present an overview of prestige horror. I have simply been intrigued to see what these four filmmakers, who have made a body of work which could be considered the core of the current prestige-horror trend, have in common and how those commonalities have helped create this new perception of a trend within the larger genre.

My interest arises from the fact that within a short period these directors have each made multiple reasonably successful feature-length horror films that have attracted favorable attention from critics, film festivals, fans, and institutions dishing out awards.

The Films

Annilhilation

Here is a chronology of the four directors’ films, with information relevant to explaining their prestige status.

2014

EX MACHINA (Alex Garland) Dist. A24

Budget: $15,000,000

Worldwide Gross: $36,869,414

Rotten Tomatoes: 92% critics 86% audience (6 points difference)

2015

THE WITCH (Roger Eggers) Dist. A24

Budget: $4,000,000

Worldwide gross: $40,423,945

Rotten Tomatoes: 90% critics 59% audience (31 points difference)

2016

None

2017

GET OUT (Jordan Peele) Prod. Blumhouse and Dist. Universal

Budget $4,500,000

Worldwide gross $255,407,969

Rotten Tomatoes: 98% critics 86% audience (12 points difference)

2018

ANNIHILATION (Alex Garland) Prod. Skydance Media and Dist. Paramount

Budget: $40,000,000

Worldwide gross: $43,070,915

Rotten Tomatoes: 88% critics 66% audience (22 points difference)

HEREDITARY (Ari Aster) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: $10,000,000

Worldwide gross $80,200,936

Rotten Tomatoes: 89% critics 68% audience (21 points difference)

2019

THE LIGHTHOUSE (Robert Eggers) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: est. $11,000,000

Worldwide BO $18,177,614

Rotten Tomatoes: 90% critics 72% audience (18 points difference)

MIDSOMMAR (Ari Aster) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: $9,000,000

Worldwide gross: $47,967,636

Rotten Tomatoes: 83% critics 63% audience (20 points difference)

US (Jordan Peele) Prod. Monkeypaw Productions and Dist. Universal

Budget $20,000,000

Worldwide gross $255,184,580

Rotten Tomatoes: 93% on RT, 60% audience (33 points difference)

2020

None

[DEVS, Alex Garland, 8-episode mini-series for Hulu]

2021

None

2022

THE NORTHMAN (Robert Eggers) Prod. by Regency and Dist. By Focus (specialty wing of Universal)

Budget: est. $70-90,000,000

Worldwide gross to May 4: $43,934,635

Rotten Tomatoes: 89% critics 66% audiences (23 points difference)

MEN (Alex Garland) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: Unknown. Collider refers to it as “a low-budget horror film.”

NOPE (Jordan Peele) Prod. Monkeypaw Productions and Dist. Universal

Budget: Unknown [July 23, 2022. Variety now reports the budget as $68 million.]

DISAPPOINTMENT BLVD. (Ali Aster) Prod. and Dist. A24

Budget: Unknown

Clearly the pandemic has delayed the completion and release of horror films, as it has with other genres, resulting in a rush of releases by all four directors in the same year. There might have been films by all four directors in 2019, but Garland was presumably busy producing, writing. and directing all eight episodes of the FX series Devs, which premiered on March 5, 2020. The series could be described as being a combination of the sci-fi and horror genres, rather like Ex Machina.

The prestige

Reviews, professional and amateur

These days, one indicator of public prestige, albeit a crude one, is the critical aggregator site, Rotten Tomatoes. It is striking that every film in this group has been rated more highly by professional critics than by audience members. Other films mentioned in discussions of prestige horror also see a similar split, as with Saint Maud (2019, Rose Glass, distributed by A24), which had a 93% critical rating versus 64% audience approval. On the other hand, Saw (2004, James Wan, distributed by Lions Gate), which is definitely not in the prestige category, had a 51% critics rating and 84% audience approval.

Festivals and Awards

It is perhaps going a bit far to call these art-house horror, since they usually play multiplexes. Still, some premiere at prestigious festivals dedicated mostly to indie films that do play art houses. These include Sundance for The Witch, Get Out, and Hereditary. Ex Machina and Us were first shown at SXSW, the latter as the opening night film–a position held by A Quiet Place the year before. The Lighthouse premiered out of competition at Cannes, and Men will do so later this month (and possibly Disappointment Blvd., see above). Announcing the latter, Deadline commented, “The non-competitive independent sidebar to the main Cannes festival has grown in reputation in recent years, having premiered pics such as Robert Eggers’ The Lighthouse, Sean Baker’s The Florida Project and The Rider by Oscar winner Chloé Zhao.”

For Nope, Peele took a more mainstream approach, revealing an extended trailer at Cinemacon on April 27, 2022.

Obviously awards signal prestige. To name some of the most notable, Eggers won for best director of a dramatic film for The Witch at Sundance. The Lighthouse won the critics’ FIPRESCI prize at Cannes, was nominated for an Oscar for best cinematography, and won the cinematography prize from the American Society of Cinematographers. Peele’s Get Out was nominated for four Oscars, winning best original screenplay. Peele made Time‘s list of the 100 most influential people in the world and the top-ten lists of the National Board of Review, the AFI, Time, and others. (He was also nominated as a producer of BlacKkKlansman.) Ex Machina surprised just about everyone by winning the Visual Effects Oscar in competition with Mad Max: Fury Road, The Martian, Star Wars: The Force Awakens, and The Revenant. The Hollywood Reporter considered its win “arguably the night’s biggest upset.”

These are some of the highly prestigious prizes. Festivals and prizes have proliferated in recent years. Local critics’ associations and proliferating specialist sci-fi/horror/fantasy festivals give out hundreds of awards, most of which never come to the general public’s attention. They do, however, stimulate interest among the core audience for horror films. (Extensive lists of such festival’s nominees and winners are provided on IMDB.)

Production and Distribution

The first three films on the above list made impressive profits on small budgets–especially Get Out. Ex Machina and The Witch were financed by cobbling together money from small, obscure companies and then picked up for distribution by A24. Both films came out one and two years respectively after A24 had released its first film in 2013, so relatively early in the company’s existence. They were among the many that have made A24 the most successful, admired producer and distributor of independent and foreign films. Ex Machina provided A24 with its first Oscar win.

The third, Get Out, made a spectacular amount of money on its modest budget.

These successes may have encourage Paramount to pick up the fourth, Annihilation, in the expectation of a similar success. Despite being one of the best films of the group (in my opinion), it was not popular and is the biggest money-loser of the group (though the final grosses for The Northman are yet to come).

The sub-genre bounced back with Heredity, which was (and may still be) A24’s biggest money-maker. The company then bankrolled Aster’s follow-up, Midsommar, which was profitable, if less so than Heredity. A24 also produced both films, so it was able to keep the entire take. These successes were perhaps some consolation for The Lighthouse‘s probable failure to break even. (A24 also produced it.) Eggers departed A24 for Regency, with an estimated $70-90,000,000 budget for The Northman–far and away the largest of any of the films released so far. Its worldwide gross as of May 4, two weeks after its release, is a bit under $44 million, making a profitable result unlikely.

The importance of A24 to the prestige horror film should be obvious. It has distributed six of the eleven films and produced three of those six.

A24 was formed in 2012. Today, the company’s astonishing list of films includes many indies of all types, including Moonlight, Minari, First Cow, The Florida Project, The Tragedy of Macbeth, and most recently Everything Everywhere All at Once.

A24 seems committed to Alex Garland, having announced that they will produce and release his next film beyond Men, entitled Civil War. That doesn’t sound like a horror film, but who knows?

A24 has clearly been crucial to the careers of Garland, Eggers, and Aster, but Peele has followed a different path to success. In 2002 he began as a stand-up comic and soon was appearing in occasional episodes of such shows as The Mindy Project and Fargo. He gained fame in the comedy series Keye & Peele, which ran from 2012 to 2015. He also produced it, forming his own production company, Monkeypaw Productions in 2012. Coincidentally this was the same year that A24 was formed, perhaps helping explain why the careers of these directors have progressed in parallel. He has continued to produce shows like Twilight Zone and Lovecraft Country. He turned to filmmaking in 2017 with Get Out, which was produced by Blumhouse, known for its low-budget, ordinarily less prestigious horror films. Universal distributed what became the most profitable film of the entire group, compared to its original budget, and soon formed a closer relationship with Peele.

In an interview with Indiewire, Peele described being cautious about asking for a larger budget for his next film, Us.

When he sat down with Universal, the studio that distributed “Get Out,” to pitch his sophomore feature, “the cards were kind of in my hands,” Peele said. “It didn’t feel like an audition. It was me telling them, ‘This is what I want to do, this is where I want to do it, how’s that sound?’” […]

“I had about five times the budget on this one, which by movie standards is still not that expensive of a film,” he said. “That was the key for me. Otherwise, I may not have had my freedom. As a filmmaker, I also thrive with a certain restriction. I didn’t want to overreach with the budget and all of a sudden have a studio being responsible on me.” He laughed. “There’s never been a point where they’ve expressed anything but wanting to make this.” When Universal gave Peele the green light to make “Us,” it also signed a first-look deal with his Monkeypaw Productions.

Universal financed and released the film, sending it to SXSW for its premiere. Remarkably, it and Get Out generated almost identical worldwide grosses. Indeed, they are far and away the top earners among this set of films. In 2019, the year Us came out, Universal signed Peele to a five-film contract, reportedly worth $300-400,000,000.

As a result of all this, Peele stands out from the rest of the group by being a very rich man. His worth in 2021 was widely estimated at $50,000,000.

This deal presumably included the recent remake of serial-killer film Candyman (2021), produced and written by Peele and directed by Nia DaCosta.

How much higher the budgets will be for these future films is impossible to predict. It is notable, however, that Nope was shot by Hoyte van Hoytema, cinematographer of Christopher Nolan’s Interstellar, Dunkirk, Tenet, and upcoming Oppenheimer. It was made on film and had sequences done in 65mm. It will be shown in Imax theaters, an obvious step up from the previous two films.

Moreover, Peele is among top Hollywood directors collaborating on Imax’s development of its next generation of cameras. Indiewire reports:

The new models are expected to be an improvement over IMAX’s current offering of cameras that utilize their proprietary 65mm film. The new cameras will be quieter, with a series of new features added to enhance usability. In addition to the four new cameras, many existing IMAX cameras and lenses are expected to be updated and improved.

If that was not exciting enough, the company will be collaborating with some of Hollywood’s top visual artists on the camera designs. Major directors including Christopher Nolan and Jordan Peele will weigh in on the new film cameras, as will top cinematographers including Hoyte van Hoytema (“Tenet”), Linus Sandgren (“No Time To Die”), Rachel Morrison (“Black Panther”), Bradford Young (“Arrival”), and Dan Mindel (“Star Trek”). Combined, those filmmakers account for many of the most acclaimed large-scale movies shot on film in recent years, in addition to even more that were shot digitally.

If Nope is a success, as Forbes is predicting it will be, will Peele branch out into other genres or continue to make prestige horror films on a bigger budget? His enthusiasm about Imax technology may hint at an inclination to break out of his current pattern for other effects-heavy genres. Still, perhaps a clue comes from the name he gave his production company, Monkeypaw Productions, invoking the classic Le Fanu horror story.

The distributors, and in the case of A24 producers, of these films have turned these directors into brand names elevated above most directors of horror films. The trailer for The Northman touted Eggers as “visionary” (top) while Paramount combined the signs of prestige in its poster: “new terror,” emphasizing Peele’s consistency as a director of horror; his “mind,” suggesting his genius for this sort of filmmaking; and naturally his record as an Oscar winner (above left).

Midsommar madness

Midsommar has emerged as one of the most admired films of the cycle, despite having had the lowest Rotten Tomatoes critics score and third lowest audience score. Its move toward prestige began quickly when less than two months after the film’s July, 2019 release, Aster appeared at the Scary Movies Festival at Film at Lincoln Center, introducing the Director’s Cut of the film. The length was increased from 148 to 171 minutes.

Martin Scorsese unexpectedly helped to raise Aster’s profile. Readers will remember his infamous remarks about MCU films not being cinema and his subsequent explanation of what he meant in The New York Times. There he listed some directors whose films exemplify genuine cinema:

Another way of putting it would be that they are everything that the films of Paul Thomas Anderson or Claire Denis or Spike Lee or Ari Aster or Kathryn Bigelow or Wes Anderson are not. When I watch a movie by any of those filmmakers, I know I’m going to see something absolutely new and be taken to unexpected and maybe even unnameable areas of experience. My sense of what is possible in telling stories with moving images and sounds is going to be expanded.

That’s pretty heady company for a director of horror films who has made two features, but there was more to come.

Scorsese followed up by writing an introduction to a book accompanying A24’s release of the Director’s Cut on Standard Blu-ray and 4K Ultra HD, available only directly from the company and packaged in jewel boxes charming enough that they could grace a Wes Anderson film. It shipped on July 20, 2020, about a year after the film’s release.

In early 2020, there was a considerable expectation among critics and fans that that the film would be nominated for Oscars. When that failed to happen, journalists’ lists of snubbed films often mentioned it indignantly. The Washington Post ran a story entitled, “The Oscars should get over their fear of horror films,” mentioning Midsommar, Us, and Heredity and especially Florence Pugh’s and Toni Colette’s performances. Indiewire listed Midsommar alongside The Farewell, Her Smell, Portrait of a Lady on Fire, Booksmart, and Uncut Gems as films unfairly receiving no nominations.

Remarkably, a protest of sorts against Midsommar‘s lack of nominations was mounted during the opening musical number of the 2020 Oscars show, on February 9. Janelle Monáe headlined and staged it, including a group of backup dancers, some of whom were dressed as various characters from some of the year’s best-picture nominees: Joker, Jojo Rabbit, and Little Women. Prominent among them, however, are four women in white Midsommar costumes, and to make the point completely clear, Monáe herself donned a copy of the protagonist’s floral May Queen dress for the last part of the number (see bottom). Pugh was in fact nominated for Best Supporting Actress that year, but it was for Little Women. She didn’t win, but she managed to get an implicit shout-out in the opener.

The extensive press coverage of the number suggested that the content was Monáe’s idea, but the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences must have approved and cooperated to some extent, given that it presumably provided the costumes and would have been aware during rehearsals that the film references in the song and dance gave the snubbed films equal or even greater attention than the nominated ones. The number inspired considerable coverage in the press, and many upset Midsommar fans posted tweets that suggested they were somewhat placated by the number.

The Academy made further amends two months later, when on May 9 the Academy Museum announced that it had put in the winning bid ($65,000) for the original May Queen dress from the film, which was sold in one of A24’s series of real movie props-and-costumes auctions for Covid-related charities (FDNYFoundation being the Fire Department of New York).

The dress was put on display in the Museum in time for the September 30, 2021 opening.

Based on a preview tour for journalists, on September 22 Timeout declared the dress one of the eleven coolest things to see at the Museum, a list which also included Judy Garland’s ruby slippers and the shark from Jaws. The first “prestige horror” film to be represented in the Academy Museum (I presume) had brought the genre a new level of respect. Maybe next year Alexander Skarsgård or Steven Yuen or Jessie Buckley or Rory Kinnear might actually receive actor nominations, not to mention some best-picture nods for the new films.

One final observation. The prestige phenomenon has been happening for some time now with foreign films seeking release in North American market. Making inexpensive horror films occasionally works as a way for unknown directors to break into an otherwise difficult market for unknown directors. Examples would include the Swedish film Let the Right One In (2008, Tomas Alfredson), the Icelandic Lamb (2021, the first feature of Valdimar Jóhannsson), which premiered at Cannes and was nominated for best international film this year, and currently the Finnish Hatching (2022, the first feature of Hanna Bergholm). Interestingly, the pattern of critics rating the films higher than audiences as measured by Rotten Tomatoes holds true for such films as well, with the three titles scoring respectively: 98%/90%, 86%/61%, and 92%/59%. Their distributors were, respectively: Magnolia Pictures (under its genre label, Magnet Releasing), A24, and IFC Midnight (ICF Films‘s genre label).

A few notes.

[Oct 31, 2022: for more on prestige horror and A24 see my analysis of Men and discussion of A24 as an “auteur studios.”

Scott Derrickson is an interesting case where a director has specialized in mainstream horror films before moving on to a MCU franchise blockbuster, Doctor Strange (2016). He was at work on the sequel when a disagreement of some sort with Marvel led to his departure. He has returned to horror with the upcoming serial-killer film The Black Phone (distributed by Blumhouse) which I mentioned seeing the trailer for. His announced projects appear to be mainstream horror and fantasy.

The prestigious horror films of the past that I mentioned all received Oscar nominations, with some wins (in bold), mainly in below-the-line categories. The Exorcist: adapted screenplay, sound, picture, actress, supporting actor, supporting actress, director cinematography, art direction, editing; Rosemary’s Baby: adapted screenplay, supporting actress; Jaws: sound, editing, musical score, picture; Children of Men: adapted screenplay, cinematography, editing; and Bram Stoker’s Dracula: costume, sound effects editing, makeup, set design.

Directors of modest horror films do sometimes return to the fold after making a blockbuster. After a string of horror films, Scott Derrickson directed Doctor Strange (2016) but now returns with The Black Phone. From the trailer referenced above, this looks like a conventional serial-killer film, apart from having Ethan Hawke as its villain. Guillermo del Toro returned to his more comfortable indie roots after Pacific Rim, and Taika Waititi apparently is keeping his word about alternating big projects (Thor: Ragnarok and an upcoming Thor film) and personal ones (Jojo Rabbit); among his many announced films are several franchise films, but also Tower of Terror, apparently a horror film.

[May 17, 2022] Alex Garland seems to be abandoning the horror genre, at least for his next film. As its title, Civil War, suggests, its an action film about that conflict. As he says in a recent interview, he’s even contemplating giving up directing and sticking to screenwriting.

[May 22, 2022] Collider‘s Chase Hutchinson has posted a list ranking A24’s twenty-one horror films from worst to best. (I don’t know when it was originally posted, but it was updated yesterday, presumably to include Garland’s Men.) As I said, I’m not a big horror fan, so I had never heard of most of these, so I’m obviously not one to quibble with the ranking–apart from the fact that I would put The Lighthouse higher than Midsommar and The Witch. I haven’t seen Jonathan Glazer’s Under the Skin, which tops the list, so I have no idea whether it really deserves to be number one.]

PERPLEXING PLOTS: On the horizon

DB here:

In the Before Times, I didn’t watch much fictional TV. Our modest monitor was chiefly a delivery device for news, DVDs, and Turner Classic Movies. We followed The Simpsons, and I came to like Deadwood and Justified, but usually the time commitment demanded by long-form series put me off. I gave my curmudgeonly reasons long ago on a blog entry.

But over the last nine months, forced to stay home, I dipped my toe in the water. Streaming made it easy to catch up with shows I’d never seen and offered a plethora, or rather a glut, of original series. This still-limited experience of long-form shows confirms the presence, if not the dominance, of what Jason Mittell in his excellent book calls Complex TV.

Many shows mix timelines with abandon. Both the documentary WeWork; or, The Making and Breaking of a $47 Billion Unicorn (2021) and the docudrama WeCrashed (2022) open near the end of the story action and then flash back to show what led up to it. (This crisis structure became especially common in 1940s Hollywood.) Billions, an older series I’d never followed, contains an episode (Season 2, 2016) that jumps to and fro among a funeral, scenes taking place before it, and scenes afterward, several attached to different characters. In the Hulu series Dopesick (2021) a sliding timeline graphic shifts among many periods and character viewpoints; to keep track of it all you’d need to make a spreadsheet. (It would amount to something like the whiteboard used in writers’ conference rooms to map out the unfolding series.) I can’t recall all the shows that friends have recommended as examples of daring play with narrative.

Of course all this isn’t news. For years both indie films and Hollywood blockbusters have offered complicated segmentations, broken timelines, and splintered viewpoints, with contradictory replays and unreliable narration. Still, it was good to be reminded that the problem I’m tackling in my latest book is still current—indeed, dominant. We may have to wait for the new Justified series to see a return to straightforward linear storytelling.

When and how did viewers develop the skills that lets them appreciate the New Narrative Complexity? This is at the center of Perplexing Plots: Popular Narrative and the Poetics of Murder.

Maybe we were always smart

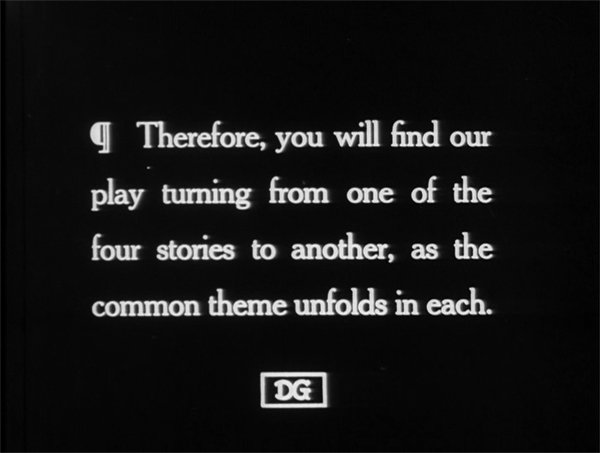

Intolerance (1916).

There’s a view, most eloquently posed by Steven Johnson in Everything Bad Is Good for You, that these comprehension skills are a fairly recent development. They stem from rising IQ levels, growing facility with video games, and other cultural phenomena after the 1970s. People are now smarter consumers of narrative than they were in the days of I Love Lucy.

I argue instead that popular narrative has been cultivating these skills across a much longer period, and they firmly took hold in mass culture at the start of the twentieth century. You can get a summary of my argument here on the Columbia University Press site.

Most broadly, a lot of (now-forgotten) mainstream plays and novels were as experimental in shifting point-of-view and juggling time frames as any we find today. For example, we celebrate backwards stories as typical of the demands of modern storytelling. The play and film Betrayal and the films Memento and Shimmer Lake are among many recent media products presenting the scenes in 3-2-1 order. But this possibility was discussed by a prominent critic in 1914, and soon a major woman actor wrote a play that used reverse chronology. There followed other examples, not least W. R. Burnett’s novel Goodbye to the Past (1934) and the Kaufman and Hart play Merrily We Roll Along (1934).

Some will argue that innovations of popular narrative are dumbed-down borrowings from modernist or avant-garde trends. I try to show this process as a two-way dynamic: modernism borrowing from popular forms, mainstream storytellers making modernist techniques more accessible. But we also find that popular storytelling has its own intrinsic sources of innovation, as with the reverse-chronology tale and Griffith’s application of crosscutting to different time frames in Intolerance (1916).

So it seems to me that audiences have long been capable of tracking the sort of fancy narrative devices we find now. They encountered them in many types of stories, and I devote the first part of Perplexing Plots to a quick survey of developments in novels and plays. (Yes, Stephen Sondheim is involved.) Audiences have learned to enjoy self-conscious artistry, an awareness of form and technique–what one disapproving reviewer of Wilkie Collins called “the taste of the construction.”

Such a taste was cultivated in depth in one mega-genre. That was a major training ground for giving us the skills to follow complex, sometimes deceptive storytelling.

Mystery on my mind

Pulp Fiction (1994).

Ever since my teenage years I’ve been a fan of mysteries on the page and on the screen. I’ve smuggled discussions of detective stories and crime thrillers into many of my books, and my last one, on 1940s Hollywood, did a lot with this form of storytelling–largely because it was so central to the films of that era.

Perplexing Plots in a way turns Reinventing Hollywood inside out. The earlier book put movies at the center while showing how filmmakers borrowed from mysteries in other media. The new one puts fiction, theatre, radio, and even comic books at the center, discussing how mystery conventions developed–and showed up in films as well. The two books complement each other, I guess, although the historical sweep of the new one runs from the 1910s to the present.

Mystery was essential to many classic novels, from Wuthering Heights to the tales of Henry James and Joseph Conrad. Dickens and Wilkie Collins made mystery a major attraction of “sensation fiction.” In the twentieth century, the Anglo-American whodunit, the suspense thriller, and the hardboiled detective tale–to take the three most well-known genres–trained audiences in appreciation of nonlinear plotting, misleading narration, and subterfuges of concealment.

A Western or a science-fiction tale may include a mystery, but it doesn’t have to. In mystery fiction, the suppression and misinterpretation of information is foundational to the genre itself. A mystery depends on a “hidden story,” which will often be revealed out of chronological order and refracted through the minds of several characters. At a meta-level, the genre cultivates a gamelike approach, where we expect the author to give with one hand and take away with the other. Across history, a mass audience became sophisticated consumers of complex narratives.

I trace how this happened with Agatha Christie, John Dickson Carr, Marie Belloc Lowndes, E. C. Bentley, Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Daphne du Maurier, Cornell Woolrich, and many other authors. I spend a lot of time analyzing both plot structure and the texture of the writing. If nothing else, I hope to show that this genre encourages not only great ingenuity in plotting but also subterfuges of style.

I trace this process into the 1940s, when in my view the basics of contemporary techniques crystallized and become widespread. The book then looks at some case studies of how crime novels and films have explored the various possibilities of broken timelines, disparate viewpoints, and misleading narration. I devote chapters to Erle Stanley Gardner, Rex Stout, Patricia Highsmith, Ed McBain, Donald Westlake, Quentin Tarantino, and Gillian Flynn.

I could have gone much farther. Every reader will have a long list of authors I’ve omitted. But I had to stop somewhere! And I decided to concentrate on some of my favorites. The result is, if nothing else, appreciations of the verbal artistry of some underestimated storytellers.

This isn’t to say that audiences of 1920 could have easily followed Inception (2010) or Everything Everywhere All At Once (2022). Storytellers have pushed forward, revising schemas that are widely known and teaching us to recognize the tweaks they’ve introduced. Audiences have accumulated a repertory of skills, built upon their experiences of other formal experiments. Those experiences, I want to show, have been crucially shaped by the conventions of mystery narratives.

Looking back on other things I’ve written, I find that I’m repeatedly concerned with finding beauty in popular genres and modes of storytelling. My studies of Hollywood, Hong Kong cinema, Japanese films, and other forms of cinema have taught me that mass entertainment harbors not only pleasures but also precise craft and daring artistry. While I’ll never give up my love of disruptive and “difficult” work, I find that films appealing to wide audiences, from His Girl Friday and Meet Me in St. Louis to the masterworks of Ozu and Hitchcock and Lang, have a unique power. Fortunately, we don’t have to choose.We can have them all. Perplexing Plots is my effort to show that storytelling craft in its humblest forms can yield its own rapture.

Advance appraisals of the book can be found here. (Click on “Reviews.”) It’s due to be published in January 2023. In the months ahead, from time to time I hope to blog more about the ideas in the book. In the meantime, I wait for the new installment of Slow Horses.

There are too many people to thank here; my debts are recorded in the book’s Acknowledgments. But at least I want to thank John Belton for supporting the project, and Philip Leventhal and Monique Briones at Columbia University Press for their swift and efficient work on the manuscript. And love to Kristin, who took care of me while I finished the book and recuperated from surgery.

The Lady Vanishes (1938).

Learning to watch a film, while watching a film

The Hand That Rocks the Cradle (1992).

DB here:

“Every film trains its spectator,” I wrote a long time ago. In other words: A movie teaches us how to watch it.

But how can we give that idea some heft? How do movies do it? And what are we doing?

Many menus

Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (2011).

In my research, I’ve found the idea of norms a useful guide to understanding how filmmakers work and how we follow stories on the screen. A norm isn’t a law or even a rule; it’s, as they say in Pirates of the Caribbean, more of a guideline. But it’s a pretty strong guideline. Norms exert pressure on filmmakers, and they steer viewers in specific directions.

Genre conventions offer a good example. The norms of the espionage film include certain sorts of characters (secret agents, helpers, traitors, moles, master minds, innocent bystanders) and situations (tailing targets, pursuits, betrayal, codebreaking, and the like). The genre also has some characteristic storytelling methods, like titles specifying time and place, or POV shots through binoculars and gunsights.

But there are other sorts of norms than genre-driven ones. There are broader narrative norms, like Hollywood’s “three-act” (actually four-part) plot structure, or the ticking-clock climax (as common in romcoms and family dramas as in action films). There are also stylistic norms, such as the shoulder-level camera height and classic continuity editing, the strategy of carving a scene into shots that match eyelines, movements, and other visual information.

Thinking along these lines leads you to some realizations. First, any film will instantiate many types of norms (genre, narrative, stylistic, et al.). Second, norms are likely to vary across history and filmmaking cultures. The norms of Hollywood are not the same as the norms of American Structural Film. There are interesting questions to be asked about how widespread certain norms are, and how they vary in different contexts.

Third, some norms are quite rigid, as in sonnet form or in the commercial breaks mandated by network TV series. Other norms are flexible and roomy (as guidelines tend to be). There are plenty of mismatched over-the-shoulder cuts in most movies we see, and nobody but me seems bothered.

More broadly, norms exist as options within a range of more or less acceptable alternatives. Norms form something of a menu. In the spy film, the woman who helps the hero might be trustworthy, or not. The apparent master mind could turn out to be taking orders from somebody higher up, perhaps somebody supposedly on your side. One scene might avoid continuity editing and instead be presented in a single long take.

Norms provide alternatives, but they weight them. Certain options are more likely to be chosen than others; they are defaults. (Facing a menu: “The chicken soup is always safe.”) An action film might present a fight or a chase in a single take (Widows, Atomic Blonde), but it would be unusual if every scene in the film were played out this way. Not forbidden, but rare. Avoiding the default option makes the alternative stand out as a vivid, willed choice.

Very often, critics take most of the norms involved for granted and focus on the unusual choices that the filmmakers have made. One of our most popular entries, the entry on Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy, discusses how the film creates a demanding espionage movie by its manipulations of story order, characterization, character parallels, and viewpoint. It isn’t a radically “abnormal” film, but it treats the genre norms in fresh ways that challenge the viewer.

Because, after all, viewers have some sense of norms too. Norms are part of the tacit contract that binds the audience to creators. And the viewer, like the critic, looks out for new wrinkles and revisions or rejections of the norm–in other words, originality.

Picking from the menu

Norms of genre, narrative, and style are shared among many films in a tradition or at a certain moment. We can think of them as “extrinsic norms,” the more or less bounded menu of options available to any filmmaker. By knowing the relevant extrinsic norms, we’re able to begin letting the movie teach us how to watch it.

The process starts early. Publicity, critical commentary, streaming recommendations, and other institutional factors point up genre norms, and sometimes frame the film in additional ways–as an entry in a current social controversy (In the Heights, The Underground Railroad), or as the work of an auteur. You probably already have some expectations about Wes Anderson’s The French Dispatch.

Then, as we get into the film, norms quickly click into place. The film signals its commitment to genre conventions, plot patterning, and style. At this point, the film’s “teaching” consists largely of just activating what we already know. To learn anything, you have to know a lot already. If the movie begins with a character recalling the past, we immediately understand that the relevant extrinsic norm isn’t at that point a 1-2-3 progression of story events, but rather the more uncommon norm of flashback construction, which rearranges chronology for purposes of mystery or suspense. Within that flashback, though, it’s likely that the 1-2-3 default will operate.

As the film goes on, it continues to signal its commitment to extrinsic norms. An action scene might be accompanied by a thunderous musical score, or it might not; either way, we can roll with the result. The characters might let us into their thinking, through voice-over or dream sequences, or we might, as in Tinker, Tailor, be confronted with an unusually opaque protagonist whose motives are cloudy. The extrinsic norms get, so to speak, narrowed and specified by the moment-by-moment working out of the film. Items from the menu are picked for this particular meal.

That process creates what we can call “intrinsic norms,” the emerging guidelines for the film’s design. In most cases, the film’s intrinsic norms will be replications or mild revisions of extrinsic ones. For all its distinctiveness, in most respects Tinker, Tailor adheres to the conventions of the spy story. And as we get accustomed to the film’s norms, we focus more on the unfolding action. We’ve become expert film watchers. We learn quickly, and our “overlearned” skills of comprehension allow us to ignore the norms and, as we stay, get into the story.

Narration, the patterned flow of story information, is crucial to this quick pickup. Even if the film’s world is new to us, the narration helps us to adjust through its own intrinsic norms. The primary default would seem to be “moving spotlight” narration. Here a “limited omniscience” attaches us to one character, then another, within a scene or from scene to scene. We come to expect some (not total) access to what every character is up to.

In Curtis Hanson’s Hand That Rocks the Cradle, we’re initially attached to the pregnant Claire Bartel, who has moved to Seattle with her husband Michael and daughter Emma. When Claire is molested by her gynecologist Dr. Mott, she reports him. The scandal drives him to suicide, and his distraught wife miscarries. She vows vengeance on Claire. Thereafter, the plot shuttles us among the activities of Claire, Mrs. Mott, Michael, the household handyman Solomon, and family friends like Michael’s former girlfriend Marlene. The result is a typical “hierarchy of knowledge”–here, with Claire usually at the bottom and Mrs. Mott near the top. We don’t know everything (characters still harbor secrets, and the narration has some of its own), but we typically know more about motives, plans, and ongoing action than any one character does.

More rarely, instead of a moving spotlight, the film may limit us to only one character’s range of knowledge. Again, scene after scene will reiterate the “lesson” of this singular narrational norm. That repetition will make variations in the norm stand out more strongly. Hitchcock’s North by Northwest is almost completely restricted to Roger Thornhill, but it “doses” that attachment with brief asides giving us key information he doesn’t have. Rear Window and The Wrong Man, largely confined to a single character’s experience, do something similar at crucial points.

Sometimes, however, a film’s opening boldly announces that it has an unusual intrinsic norm. Thanks to framing, cutting, performance, and sound, nearly all of Bresson’s A Man Escaped rigorously restricts us to the experience of one political prisoner. We don’t get access to the jailers planning his fate, or to men in other cells–except when he communicates with them or participates in communal activities, like washing up or emptying slop buckets.

The apparent exception: The film’s opening announces its intrinsic norm in an almost abstract way. First, we get firm restriction. There are fairly standard cues for Fontaine’s effort to escape from the police car that’s carrying him. Through his optical POV, we see him grab his chance when the driver stops for a passing tram.