Archive for the 'Festivals: Torino' Category

Torino tour of world cinema

Synonymes (2019).

Kristin here:

After visiting museums on the one free day we allowed ourselves in Turin before the festival began, we launched into viewing films from around the world. Here are three of the best we’ve seen, to add to the ones David has discussed.

Synonymes (France/Israel/German, dir. Navad Lapid)

Israeli director Navad Lapid has become a familiar figure for us as we have visited past festivals in Vancouver. We blogged about his Policeman in 2011 and The Kindergarten Teacher in 2014. His latest film raises his profile considerably, having won the Golden Bear at Berlin and had its North American premiere at Toronto. (Ozon’s By the Grace of God, which we blogged about from Vancouver, won the Silver Bear.)

Synonymes started with an abrupt chase, with the camera bouncing about as it follows our hero, Yoav, as he dashes through the streets of Paris (above). I was worried that this loose style of shooting would dominate, but Lapid has something more disciplined involved. The unfastened camera is usually used for exteriors, while interiors are made up of static shots.

He arrives at a large empty flat that someone has loaned him, where the heat has apparently been turned off. He proceeds to take a cold shower, and, having neglected to lock the door, he finds his backpack and sleeping bag stolen. He is left naked with no possessions whatsoever. A wealthy young couple from downstairs rescue him from hypothermia and become fascinated with him, taking him in briefly. Émile gives him money, as well as clothes. He holds up a long series of colorful shirts, which he himself apparently never wears, judging from his own muted wardrobe.

Lapid matches these colors to the decor, especially the distinctive, bright mustard-hued overcoat that Yoav wears through much of the film. The coat makes him easy to spot and marks him as an outsider among the more conventionally dressed Parisians around him (see top).

We soon learn that he is fleeing from his oppressive life in Israel and wants to become a Frenchman as soon as possible, refusing to speak anything but French despite his elementary grasp of the language. (The title comes from his habit, when wandering around alone, of muttering a series of words with similar meanings.)

There’s not much of a goal operating here, apart from Yoav’s increasingly strained efforts to turn himself into a Frenchman and abandon the violence inculcated into him by his time in the Israeli army. His one conventional job is as a security guard at the Israeli consulate. His violent outbursts and willfully eccentric behavior increase as the film goes along.

The rather episodic film revolves around the driven performance of Tom Mercier, an Israeli theater student who knew no French and, remarkably, is making his film debut here.

Kino Lorber has released Synonymes (as Synonyms )in North America. For a plot summary and a list of theaters where it has played and will be playing into January of next year, see the company’s webpage.

True History of the Kelly Gang (Australia, dir. Justin Kurzel)

Bushranger films, of which True History of the Kelly Gang is one, are more or less the Australian version of American westerns. The tale of Ned Kelly and his gang is almost a mini-genre in itself, going back to what is claimed to be the world’s first feature film, The Story of the Kelly Gang (1906, dir. Charles Tait, partially surviving).

Justin Kurzel adopts a fresh take on the familiar Kelly tale, which is as much myth as fact. He based his film on Peter Carey’s novel of the same name, which won the Booker Prize and many other awards. By adding “True” to his title, Carey both acknowledged the fact that he was embroidering the national legend as much as adhering to the facts.

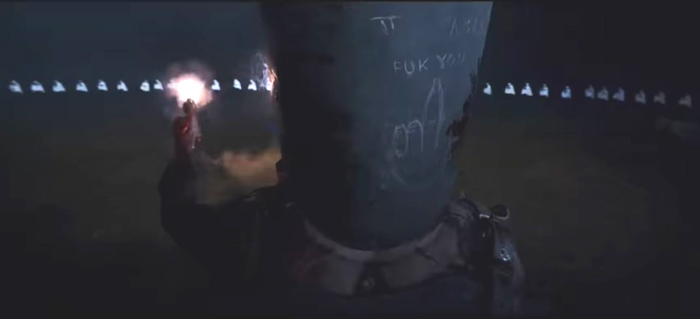

Kurzel does the same. A title appears on the screen: “Nothing you are about to see is true.” All of the words besides “true” fade out, and the rest of the film’s title fades in beside it. Those of us not steeped in Australian history and culture will not be able to fill in the inauthentic parts, but it doesn’t really matter. It’s a gripping story nonetheless.

The film opens when Ned is a boy, living with his mother Ellen and siblings in a bleak part of the bush consisting mainly of stubby dead trees (above). Although an honest lad to start with, he is drawn into the family’s long-time opposition to the local constabulary and military forces. Despite her fierce love for her family, Ellen sells him into apprenticeship to a putative merchant and herder (played with not quite too much gusto by Russell Crowe). The man turns out to be a highway robber, and Ned is reluctantly pushed toward a life of crime.

The film follows the novel in using a voiceover narration by Ned, reading from a diary purporting to be for his young daughter after his inevitable demise. (In fact the figures of the wife Mary and the daughter are part of the tale’s embellishment.) Indeed, we are nearly always in his presence and are led to sympathize with him because almost everyone around him except Mary exploits him.

The film is visually impressive, including some shots that leave one wondering how they were accomplished. At intervals there are fast drone shots above the sea of dead trees as Kelly and others ride horses through the landscape. One shot at night features an immense pool of light from above that moves smoothly with the horseman, keeping him visible as the stark gray trees appear from and disappear into the inky surroundings.

The climactic shootout between Kelly’s gang of four men in home-made armor and a large posse approaching from the distant background provides an unforgettable image. The last man standing, Kelly himself, back to camera, fires at a line advancing figures. They appear spread across the screen as tiny white figures–looking distinctly like Ku Klux Klan men in full garb. (See bottom.)

True Story of the Kelly Gang contains considerable strong profanity and violence, which would seem to warrant a risky hard-R rating in the US. Nevertheless, just before the film’s world premiere at Toronto, IFC acquired the North American rights to the film for a reported seven-figure sum, bidding against three other distributors. IFC will evidently release it in 2020. (The first trailer has just been posted on Youtube, but there is currently no mention of the film on the IFC website.)

Noura’s Dream (Tunisia/France/Qatar, dir. Hinde Boujemaa)

Increasingly female directors working in Middle Eastern and North African countries are gaining a foothold in the international film market. Recent notable films have been Saudi director Haifa Al Mansoor’s The Perfect Candidate in competition at Venice and Nadine Labacki’s Lebanese film Capernaum, Jury Prize winner at Cannes in 2018.

Tunisian director Hinde Bujemaa’s Noura’s Dream centers on a woman with three children who is awaiting an imminent divorce from her incarcerated husband, Jamel, so that she can marry her lover, a car-repairman, Lassaad. Meanwhile she is working in a laundry to enhance her government checks and support her family (above).

Though Tunisia is somewhat more liberal than other Muslim countries, Noura still faces traditional prejudices. In the opening scene, an official tries to talk her out of the divorce for the sake of her children–as if living with an abusive criminal for a father is more desirable than having a kinder stepfather.

Jamel is released unexpectedly early, and Noura must live with him for the few days until the divorce is final. She pretends to be considering staying with him, despite the fact that he returns to his criminal activities and abuses his family, at one point throwing them out of the house (above). As Bujemma points out in a Variety interview, however, Jamel is not all bad, not taking the option of betraying to the police Noura’s adultery with Lassaad, still a criminal act in Tunisia.

In a way Noura’s Dream seems to reflect the considerable impact that Asghar Farhadi’s Oscar-winning films have had on other directors in the region. The situation of an impending divorce recalls A Separation, yet Farhadi’s films tend to have quiet, “everyone has his reasons” plot arcs with twist revelations and moral ambituities. Here, telling such a story and eager to display the biases against women in Tunisian society. Bujemma takes a more melodramatic approach. Jamel is an unrepentant criminal and Noura is a brave, determined woman struggling to separate herself and her children from him. Lassaad is a decent fellow nevertheless ultimately driven to reject her when she shows no signs of leaving Jamel.

It’s a film that effectively builds up considerable sympathy for Noura, played by prominent Middle-Eastern star Hind Sabri, and withholds hope, or possible hope, until the last shot.

Noura’s Dream has played several festivals, including Toronto, London, and now Torino and has releases in Europe and its native country, but there is so far no North American distributor.

The Horror Thread

As David mentioned in our previous post, the Torino Film Festival includes a retrospective program each year. This time it was horror films, from Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari to Roy Ward Baker’s Dr Jekyll & Sister Hyde (1971, UK). I fit some of these into my schedule in between the new films.

There were 35mm prints of I Walked with a Zombie (1943, Jacques Tourneur), The Masque of the Red Death (1964, Roger Corman) and The Devil Doll (1936, Todd Browning), among the films I saw. The DCPs of The Body Snatcher (1945, Robert Wise) and The Innocents (1961, Jack Clayton), the latter shown immediately after the former, offered two gorgeous examples of black-and-white cinematography. In all the retrospective included 36 films, many of them probably being viewed by Italian attendees for the first time in their original languages, rather than dubbed versions.

We wish to thank Jim Healy, Emanuela Martini, Giaime Alonge, Silvia Saitta, Lucrezia Viti, Helleana Grussu, and all their colleagues for their kind help with our visit.

For more Torino images, visit our Instagram page.

True Story of the Kelly Gang (2019).

Women in charge: Highlights from Torino

Beanpole (2019).

DB here:

Every day we’ve spent at the Torino Film Festival has yielded us fine and sometimes superb film experiences. Herewith some examples, all probably coming to a screen (large, small) near you.

Extracurricular melodrama

Wet Season (2019).

From Anthony Chen (Ilo Ilo, 2013) comes a woman’s drama of professional and personal travail. Ling is a Malaysian teacher working in a Singapore boys’ school. She’s trying to get pregnant through in vitro fertilization , although her husband is reluctant. She takes care of her elderly father-in-law while pressing her mostly indifferent students to pass their Chinese examinations. Things take a drastic turn when, just as Ling’s husband drifts away from her, one boy becomes violently infatuated with her.

Poised and mild-mannered, Wet Season handles its melodramatic material with restraint. For instance, there’s the careful use of Ling’s car. She and her husband are introduced driving to work together, but the shots don’t show their faces. It’s an effective expression of their empty marriage. Similar shots recur throughout the film.

Denying us the standard view forces us to pay attention to the dialogue. Lest this be thought a simply byproduct of production constraints (it’s easier to shoot a rainy drive from the back seat), later we see Ling in a more standard angle.

The new framing allows us to see her accusing glance at Wei Lun.

Still other uses of the car enable Chen to stress Ling’s reactions to developments in the drama.

Here, as so often in film, simple but shrewd production choices can build strong emotional impact. By the end, when the typhoon has finally blown over, Ling can confront the future with some hope.

Horror diva

As indicated in our previous entry, the guest of honor for Torino’s horror retrospective was the star of 1960s Italian (and other) frightfests, Barbara Steele. She received the Gran Primio Torino during the festival. Several of her films were shown, reminding me of the delirious ways that Italian filmmakers revised the genre. Take the two features I saw.

Mario Bava’s Black Sunday (La maschera del demonio, 1960), which came out the same year as Psycho, is in some ways more shocking. The opening, in which a spike-studded iron mask is pounded bloodily into the face of a witch still makes you jump. What follows is essentially an old-dark-house plot, with one character after another prowling around a castle and getting killed off by the undead witch Asa and her brother. Asa targets her descendant, the beautiful Katia, in the belief that taking her blood will grant her immorality.

Barbara, with bat-wing eyelashes and magnificently tousled hair, plays both Asa and Katia. In a bravura image, Bava uses visual effects to give us the two women in a fine widescreen composition.

The film’s endless play of highlights and shadow is really something. Although I’ve seen it before, I never appreciated its visual splendor until I encountered this DCP restoration. Kristin pointed out that we can see how the eyelights on Asa are flicked on and off so that she seems throbbing with supernatural energy.

Two years later, Barbara made for director Riccardo Freda The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (L’Orribile Segreto del Dr. Hichcock). It’s close to 1940s Hollywood Gothics in centering on uxoricide. But in a typical giallo fantastic twist, the husband who dispatches one wife accidentally tries to kill a second to revive the first. There are 1940s motifs such as the sinister housekeeper (Rebecca), the dominating portraits of Wife #1, the efforts to gaslight Wife #2, and even a glowing glass of milk (Suspicion) with which Dr. H hopes to dispatch his new wife–played, of course, by Ms Steele.

Freda has recourse to the fog and sinister noises of Black Sunday, but Bava’s labyrinthine secret passages and torture chambers are replaced by rooms stuffed with sinister chachkies. And Hichcock is in Technicolor, so Freda gives the dank Victorian parlors a subdued color design. Barbara is right at home here too, rolling her eyes apprehensively as she’s given the poisoned milk.

In all, the Torino horror retrospective was a bracing reminder of a genre that has shaped popular cinema to this day. The presence of Ms Steele was a wonderful bonus.

Cops, moles, and femmes fatales

The Whistlers (La Gomera, 2019).

When a film is grounded in a basic genre formula, much of your enjoyment comes from seeing not only fresh twists of plot but also felicities of sound and image. That was my response to Corneliu Porumboiu’s The Whistlers (La Gomera), a quietly flashy neo-noir.

Everything is there. We have the intricate schemes of cops, crooks, and everybody in between in pursuit of mattresses stuffed with cash. There’s the tired, seen-too-much cop who works for the gang, not least because of the wiles of a stupendously gorgeous femme fatale. There are the Eurotrash thugs and heavies supervised by a calculating boss, and flashbacks that lead you to wonder who exactly is conning whom.

But Porumboiu tinkers with the familiar narrative mechanics. In an age of cellphones and video surveillance, the crooks must communicate in a frankly analog code: they whistle their messages, disguised as birdsong. The tough supervisor who suspects our protagonist is a mole isn’t the usual overbearing male, but rather a woman with her own femme fatale streak. She’s as suspicious of surveillance as the crooks, stepping outside her bugged office to negotiate extralegal stings with her staff.

Likewise, Porumboiu gives up the “free-camera” straying and fumblings that we see in so many films these days. He locks down his camera to create precise, radiant images. Here’s Gilda, yes, you heard that right, smoking and waiting for trouble.

It’s a pleasure to see crisp frame entrances and exits, along with tracking shots reserved for climactic moments, as when the gang steps into a police ambush mounted on a disused film set. A well-judged sense of framing enables an overhead shot in which the dark blood of a dead man at a work station flows into the mouse and lights it up in a discreet crimson flash.

The Whistlers isn’t as rich, I think, as the director’s earlier policier, Police, Adjective, but it’s a satisfying genre exercise. It yields dry wit (sleek fashionista gangsters struggling to load mattresses into a small car) and surprise twists–not least the epilogue, which brings back the coded whistles in an amusing sound gag.

Women at war

Beanpole (2019).

Another way to put it: The Whistlers is that rarity today, the thoroughly “designed” film. Here all the stylistic and narrative choices stand sharply revealed as part of what we are to notice, and enjoy. (Other instances: the Coens, Almodóvar.) Another example at Torino is the already widely-praised Russian drama by Kantemir Balagov, Beanpole.

Leningrad: World War II has recently ended, and two women must face the postwar world. Iya and Masha have been gunners at the front. Iya was invalided out because of episodes of “freezing,” seizing up in a sort of paralyzed trance and making clicking sounds until the spasm eventually passes. Now she works in a hospital patching up wounded soldiers and taking care of Masha’s child, born at the front. Masha eventually returns and takes a job at the hospital as well.

But their friendship suffers through a horrific accident that plunges the towering and slender Iya, the beanpole (dilda, “tall girl”) of the title, into shame and depression. Masha, more aggressive in remaking herself as the war ends, drives the second half of the film. She begins a pragmatic relationship with the weak soldier Sasha. When he brings her home to meet his parents, proud members of the Bolshevik bourgeoisie, she supplies all her backstory about life on the front that fills in crucial gaps.

Beanpole‘s few characters–the two women, Sasha, and a weary doctor supervising the clinic–throb with a Dostoevksian intensity. With her paralysis and quiet mournfulness, Iya recalls Prince Myshkin; some shots virtually sanctify her.

As in Dostoevsky’s novels, nearly every scene is worked up to a furious emotional pitch. The nosebleed that seems to pass contagiously among characters is virtually a sign of passions under pressure.

The tension is carried through lengthy, often silent stares shared between characters thrusting themselves at one another. Balagov relies on close-ups and tight two-shots running very long; there are about 325 shots in the film’s 131 minutes. Here Iya helps a dying soldier to smoke in a perfectly composed two-shot in the wide format.

Without prettifying Leningrad during and after the siege, the film’s pictorial design is ravishing. The main sets are designed to complement one another. The hospital is bathed in a creamy light, while the night streets radiate a dark golden glow.

The apartment Iya and Masha share is ripe in dark greens and reds, the result of years of tearing away layers of wallpaper. (See our top image.) The doctor’s apartment offers a warmer, less distraught balance of reds and greens.

The palatial home of Sasha’s parents yields another register, one of tidy, frosty elegance.

And the clinic is given a dose of red and green by the painted walls and the presence of little Pashka.

The pictorial harmonies and modulations are just one part of this gripping, exhilarating film. Beanpole will be distributed by Kino Lorber in the US and Mubi in the UK.

We wish to thank Jim Healy, Emanuela Martini, Giaime Alonge, Silvia Saitta, Lucrezia Viti, Helleana Grussu, and all their colleagues for their kind help with our visit.

Thanks as well to David Vandenbossche for a correction of a movie title.

For more Torino images, visit our Instagram page.

Cynthia Hichcock (Barbara Steele), trapped in a coffin by her husband, in The Horrible Dr. Hichcock (1962).

Torino images, preparing for the festival

DB here:

If you’re not a hardcore horror fan, you may not recognize the image that adorns this year’s Torino Film Festival publicity, but I bet you’re fascinated by it anyway. Barbara Steele, the diva supreme of 1960s scary cinema, is a fitting emblem for this year’s broad and deep retrospective of the horror genre. From The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1920) to Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde (1971), thirty-six films are on display, often in 35mm prints. Emanuela Martin, the curator of the series and director of the festival, has created a book devoted to her program. And the festival has welcomed the iconic Ms Steele as a guest.

In-depth commitment to a retrospective is typical of this enterprising festival. Kristin and I had been hearing about it for years from our friend, Wisconsin Cinematheque honcho Jim Healy, who has long been a contributing programmer here. Previous editions focused on “Amerikana,” De Palma, dystopian SF, Powell & Pressburger, and Miike Takashi.

Still, at Torino as elsewhere, the emphasis falls on new work. Dozens of films are screened both in and out of competition. Kristin and I are still assimilating items to report on in forthcoming blog entries. But we’ve already sampled the charms of this city, not least its monumental temple to film, its Museo del Cinema. But first, another municipal tribute to picture-making.

Pictures, some puzzling

The Galleria Sabauda in the Palazzo Reale teems with masterpieces, mostly from the collection of the Savoy dynasty. The non-masterpieces are worth studying too, and some, even in their weirdness, can prompt thinking about cinema (of course).

For instance, there’s this Antonio Tempesta painting, Torneo nella Piazza del Castello (1620), showing an aristocratic wedding procession in a Turin plaza. I liked its steep perspective with the commanding figure of the warrior in the foreground. Close observation, which the Sabauda permits, reveals tiny figures on the rooftop at the left.

Evidently the paining yields a lot of information about architectural projects of the day. All I could think of is what a swell film shot it would be.

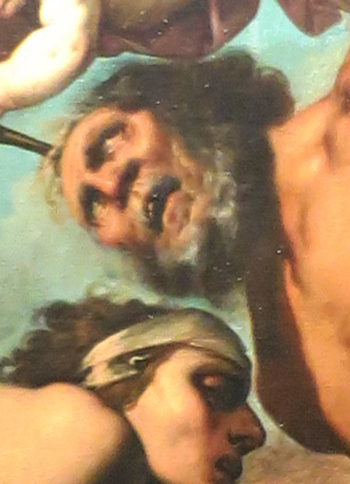

Instead of Testa’s high angle, which yields a centered and stable composition, consider Varallo’s punchier Saints Peter and Mark, from the same period (1626).

The low viewing angle on the two saints makes their muscular gestures dominate the middle of the format. That axis calls to their incredibly distended fingers caught in the act of dictating and writing. The angle also lets us enjoy the casually crossed leg of Mark and his tense, splayed toes, which seem to poke against the picture surface.

Angles again: This unidentified painting of the savage martyrdom of Saint Bartholomew (ca. 1635) grabbed me because of its even steeper low angle.

Apart from the Caravaggio spotlight effect (overexposed in my shot; I can’t find an image online), it reminded me of one of my fussier concerns.

Cinema lets us separate planes because of constant overlap, one layer of space moving against another. Painting can’t let us detect contours from movement, so when painters want to shove figures together they need to mark off overlapping planes in other ways, such as color or edge lighting.

Alternatively, painters can pack figures but leave little holes that let bits of background show through but still give a sense of movement. In the St. Bartholomew painting, the contours that specify the figures nearly graze each other.

I especially like the way that the brow and nose of Bartholomew’s tormentor fit like a puzzle-piece into the twist of the saint’s shoulder. Good old figure/ground technique, but pushed to a kind of minimal limit.

When these little gaps aren’t left, and only overlap and colors pick out planes, you can get some striking effects. The most mind-bending thing of this sort I saw at the Galleria was this Resurrection, perhaps by Antonio Campi, from around 1660. At the bottom of the picture a soldier is prodding a sleeping guard beside the sepulcher.

The soldier on the right is one strange creature. You can work it out that he’s wearing a thick, ribbed yellow doublet with a beast’s head attached at the shoulder. But the effect of the overlapping planes and the compositional contours is of a duck/rabbit shift, as if the beast is bent over the soldier.

The effect is enhanced by the sinewy leg of the soldier behind, which seems at first glance to be the right arm of the stooped beast. The absence of spacing between the foot and the spear helps the effect of a limb continuing the arc of the bent back.

Enough of amateur art appreciation. Turin houses another magnificent repository of artifacts, this one dedicated to our own obsessions.

Film history on a grand scale

Mole Antonelliana, Turin.

The Museo Nazionale di Cinema is housed in the Mole Antonelliana, a fascinating elongated building that towers over the city. An elevator shoots people up to a fancy spire with a panoramic view.

Pictures can’t do justice to the Museo inside. You enter through the biggest and most engaging collection of pre-cinema materials I’ve ever seen. Nearly every gadget, from the magic lantern to Edison’s Kinetoscope, is offered for you to tinker with. (An interactive sampling is here.) Once you’ve seen the entire archaeology of film, you step into a gigantic hall with a spiral ramp leading to level after level.

Nearly the first thing you meet is the god Moloch from Cabiria (1914), a film made when Turin was a major national production center. Not quite as big as in the film, he was enough to intimidate me.

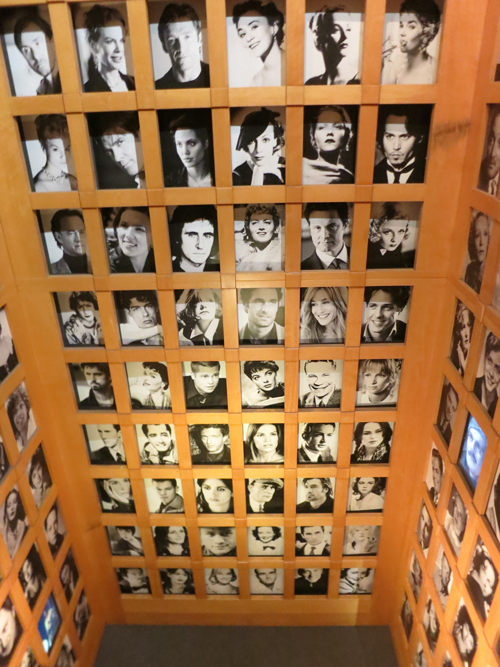

Various floors take you to theme areas. There’s one on film production with some classic cameras, another displaying a vast gallery of posters, and several devoted to changing exhibitions. (The current one was on facial expression in cinema, hooking to a big show of Lombroso’s physiognomic studies.) You can see a script page from Psycho or Citizen Kane, and stare in awe at a two-story display of star portraits.

Kristin and I visited a shrine to the beautiful Prevost editing table. (This is a 1930s one.)

There’s so much here that more than one visit is probably demanded. In all, the Museo makes a splendid anchoring point for the film festival. We’ll tell you more about that in upcoming entries.

We wish to thank Jim Healy, Emanuela Martini, Giaime Alonge, Silvia Saitta, Lucrezia Viti, Helleana Grussu, and all their colleagues for their kind help with our visit.

For more Torino images, visit our Instagram page.

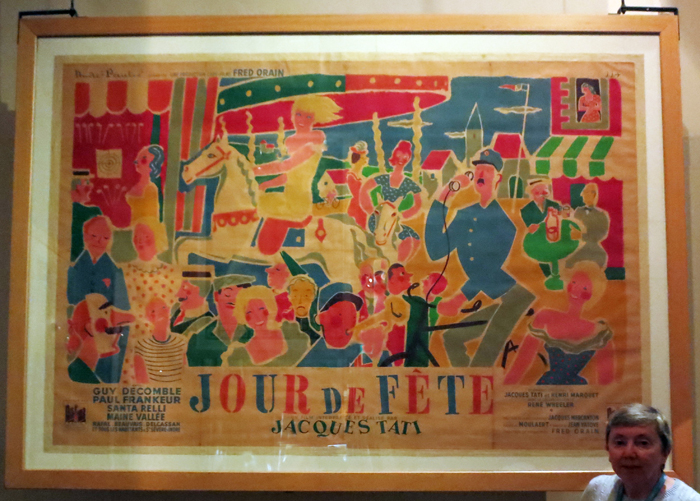

Kristin and a big poster for Tati’s Jour de fête.