Archive for the 'Directors: Griffith' Category

Wisconsin Film Festival: Cutting to the chase, and away from it

Nocturama (2016).

DB here:

Despite my recent jab at D. W. Griffith, I gladly give him credit for making crosscutting a central technique of narrative cinema. Using editing to switch our attention from one story line to another is a fundamental resource of moviemaking everywhere.

Crosscutting is most apparent in those passages of quickly alternating shots that build tension during chases and last-minute rescues. That’s a prototype of what we credit Griffith with consolidating. But crosscutting is used outside such climactic stretches. Hollywood silent features often crosscut story lines throughout the film, without pressure of a deadline and without much happening in some lines of action. It seems to be a way that filmmakers found to keep the audience aware of many story strands.

Crosscutting is a cinematic version of a very old narrative strategy, that of alternating presentation. Once you have several story lines, you can switch among them. Homer does this in the Odyssey, interweaving Ulysses’ wanderings, Telemachus’ efforts to find him, and Penelope’s holding off the suitors.

Homer initially handles these lines in large blocks, in separate “books.” After attaching us to Telemachus in Books 1-4, Homer shifts us to Ulysses for a long stretch. Such interlacing can be found in medieval narrative too, and of course it dominates modern novels, with chapters shifting among action lines and character viewpoints.

Crosscutting large chunks can give way to shorter bursts. Ulysses’ travels occupy several books, but as he approaches Ithaca, Homer interrupts Book 15 to switch back and forth between him and Telemachus, also headed for home. In cinema, this sort of accelerated crosscutting, often driven by a deadline, has become identified with Griffith’s The Lonely Villa (1909), A Girl and Her Trust (1912), and other Biograph shorts. He lifts the principle of crosscutting to a vast scale in his features. The Birth of a Nation (1915) alternates North and South, home front and battlefront, carpetbaggers and Klansmen in a novelistic fresco.

Crosscutting usually implies some degree of simultaneity. While Telemachus searches for his father, Ulysses leaves Calypso and the suitors run riot in the palace. The notion of actions taking place at more or less the same moment is especially important in chases and last-minute rescues.

As a plot reaches its climax, there can be a sort of site-specific crosscutting too. Once Ulysses and Telemachus have joined forces to slaughter the suitors, Homer’s narration sometimes switches among areas of the fight, as in the battle scenes of the Iliad. While father and son hold off the suitors in the main hall, two servants capture one suitor in a storeroom. We recognize this technique of adjacent alternation when novels and films gather all the major characters in one spot for the climax and shuttles among them.

Crosscutting remains a basic filmmaking tool for most movies on our screens. Where would the Fast and Furious franchise be without it? But some contemporary filmmakers have made fresh uses of the technique. In Inglorious Basterds, Tarantino adopts the big-segment option, alternating lengthy blocks of action before using faster crosscutting when characters converge at the climax. Christopher Nolan has experimented with various tactics, including crosscutting different phases of the same action (Following) and crosscutting among embedded segments, dreams within dreams (Inception).

So there are still lots of options out there to be explored. Just look at some films shown at our Wisconsin Film Festival. Beware, though, of light and heavy spoilers.

Attachment plus anxiety

Frantz (2016).

At one end of the spectrum: Must you always use crosscutting? Wigilia, a charming short feature by Graham Drysdale, suggests not.

It’s built on two Christmas eves a year apart. In the first, a Polish refugee who cleans house for a brusque businessman is alone for the holiday and in his apartment prepares the traditional holiday meal—not for herself but for her absent family. She’s interrupted by the businessman’s vaguely hippy brother, and the two learn about each other as they share the meal. In the second evening, after the businessman has left the apartment to his brother, she returns and they bond more intensely.

Apart from an inserted dream sequence, we stay within the apartment. This concentration derives from the production circumstances; Graham explains that he was given a chance to make the film in short order, and to keep it manageable he came up with the idea of limiting the locale. He shot 53 minutes of footage in five days in the apartment, then did the two final scenes in two days. The narrowly focused drama, with many lines improvised, has no need for the free-roaming tactics we associate with crosscutting.

Crosscutting tends to give us a fairly unrestricted range of knowledge; often we know more than any one character. In The Girl and Her Trust, the telegraph operator holding off the robbers can’t be sure that her boyfriend is rushing to her rescue, and he can’t know how close the robbers are to seizing her. Alternatively, when we’re mostly restricted to one character, we don’t find a great deal of crosscutting.

That’s the case in François Ozon’s Frantz, a remake of Lubitsch’s Broken Lullaby (1932), also shown at WFF. Anna’s fiancé Frantz has been killed in the Great War. Out of sympathy his parents have taken her in and treat her as a daughter. But when she sees Adrien, a melancholy Frenchman, haunting Frantz’s grave, she gets curious. Most of the ensuing film is restricted to what Anna learns,

Adrien visits the family. Flashbacks lead us to think he’s what he hesitantly claims to be: a friend of Frantz from prewar Paris. But he has been pressed to tell the parents what they wished to hear. Adrien actually came to the village to beg their forgiveness for killing Frantz on the battlefield, where they met for the first time. Although we surely have reservations about the sad, apprehensive young man, we don’t learn the truth until Anna does, at about the midpoint of the film’s running time. By this time she has fallen in love with him.

There is some alternation of viewpoint in the film. A few scenes attach us to Adrien during his stay in the village, chiefly when he confronts bitter locals who still consider France their enemy. Still, these scenes don’t give us much direct information about the true backstory. And after Adrien has left and Anna has sought to keep the parents in the dark about the past, we remain attached to her. No crosscutting shows us Adrien’s return to France and his life there. As a result, we’re able to feel curiosity and suspense when Anna decides to track him down. The revelation of his civilian life raises a set of unexpected conflicts.

Both Wigilia and Frantz show that avoiding crosscutting can be a powerful way to keep our attention fastened on characters, the better to let their words and behaviors, as well as their inner lives, get primary emphasis. Crosscutting yields a panorama, while refraining from it can aid portraiture.

Crosscutting as usual

The Student (2016).

More toward the center of the spectrum lies ordinary crosscutting, the alternation among scenes that provide a broad perspective on the action. In Arturo Ripstein’s Western Time to Die (1965), the plot alternates between scenes featuring the returning convict Juan Sayago and episodes showing the reactions of different townsfolk—chiefly the sons of the man he killed. We also learn of efforts from women in the town to prevent the sons from taking revenge. This “moving-spotlight” narration isn’t perfectly omniscient, though. The plot gradually fills in information about what led up to Sayago’s crime, while revealing that the sons’ mission would amount to avenging a dishonorable father.

A similar sequence-by-sequence approach is seen in The Student, aka The Disciple, a Russian film by Kirill Serebrennikov. A fanatical teenager has become the scourge of the classroom, barraging teachers and pupils with Bible quotations and denunciations of bikinis. His mixed-up fundamentalism, which leads him at one point to challenge evolution by donning a gorilla outfit, is unpredictable and a pure power trip, Biblical bullying.

His mother can’t manage him, the administrators are reluctant to take stern action, and the school priest sees him as a potential recruit to the clergy. Only one teacher, Elena, challenges him with a mix of humor and sympathy. But to combat his increasingly wild behaviors, which include making himself a full-size cross which he can stretch out on, she too sinks into Scripture. She hopes to quote the Bible back at him and dislodge his dogmatism, but she too becomes obsessed and estranges herself from her boyfriend. Meanwhile, Venya gets his one true disciple, a limping underdog, and his campaign against homosexuality, science, and secularism turns violent.

A good part of the narration locks us in to Venya’s Dostoyevskian ferocity, thanks to a restless use of the “free camera” in lengthy following shots. (The film has only about 150 shots in 113 minutes.) But we do range more widely to get a broader view. The moving spotlight shows the mother’s frantic consultations with school officials, and Elena’s clashes with them, as well as with her boyfriend. Still, the climactic scene, which assembles all but one of the characters in a single meeting, has no need of a broader view. Like Wigilia, The Student draws its final power from drilling down into a confrontation around a table.

Gaps and folds in time

Killing Ground (2016).

Griffith rang many changes on his last-minute-rescue template, and one of the most startling occurs in Death’s Marathon (1913). A dissolute husband, bored with his life, decides to commit suicide and notifies his wife by phone. She calls the family friend, who races to prevent the death. Surprise: He’s too late.

A hundred-plus years later, crosscutting builds and then deflates suspense in the Romanian film Dogs, by Bogdan Mirica. There are two protagonists: Roman, a city fellow who has inherited his grandfather’s idle farm, and Hogas, the police chief. Both face off against sadistic hoodlum Samir and his thugs. A human foot has popped up (literally, in the first shot), and Hogas tries to trace its owner, while Roman decides how to dispose of the farm. Samir explores other possibilities, none very savory.

At first we’re restricted to Roman, who is frightened by distant lights and gunshots out on the property, and Hogas, who doggedly pursues his investigation. The alternation between them keeps Samir offscreen for some time. When he surfaces in a suspenseful drinking bout with Roman, and when Roman’s girlfriend comes to pay a visit, the threats start building.

The climax starts out as pure Griffith. Mirica crosscuts Roman’s drive back to rescue his girlfriend, Hogas’ pain-ridden walk to the farmhouse, and Samir’s ominous approach to the isolated woman. Interestingly, the pace of the cutting doesn’t much accelerate in these last moments; there isn’t a lot of alternation, and the emphasis is on prolonged actions (Hogas’ trudging pace, interrupted by coughing up blood, and Samir’s laconic dialogue with the girlfriend).

By the time Hogas arrives, he finds he’s too late. The conventional mystery and suspense of the first stretch are undercut by showing us only the eerie aftermath of a violent climax. Art-cinema norms can de-dramatize crosscutting, but the maneuver remain a revision of what Griffith tried for in 1913.

Three years after Death’s Marathon, Griffith showed the possibility of crosscutting radically different time frames. Intolerance (1916) interweaves four historical epochs while using crosscutting within each one as well. Since then, crosscutting has sometimes been used to juxtapose past and present (The Godfather Part II, The Hours), or alternative futures (Sliding Doors), or a real story and a fictional one (Full Frontal). Interestingly, Griffith is a bit more daring than these directors. These films usually alternate sequences or entire blocks. At first Intolerance does that too, using titles to mark the shift among its four eras. But as the film reaches its climax, Griffith cuts freely from one period to another. These shot-to-shot time shifts, jumping centuries in the burst of a cut, remain an audacious formal discovery.

In all these examples, we’re cued to realize when we move to another period. But Killing Ground, a grueling Australian thriller by Damien Power, doesn’t announce its time-shifting. It exploits our default assumption that crosscutting implies more or less simultaneous action.

At first Killing Ground does give us rough simultaneity, alternating between the yuppie couple, Ian and his fiancée-to-be-Sam, and a pair of gun-loving locals. But then the couple make camp near another family’s tent.

Through careful use of eyeline matches and other continuity cues, the narration welds together actions that are actually taking place at different times. The family’s evening meal and their foray into the woods happen well before Ian and Sam arrive, but the cutting implies that the two groups are living side by side.

Like Griffith, at moments Power shifts between the two periods on a shot-by-shot basis. Small disparities, like a baby bonnet and the placement of the campers’ vehicles, accumulate. By the time Ian follows one of the psychopaths into the woods, we realize that earlier events have been salted through the present-time action, the better to delay revealing the family’s fate. From then on, orthodox crosscutting takes over as Ian runs for help and Sam tries to hold the rampaging peckerwoods at bay.

The kids aren’t alright

At the distant end of the spectrum, how about building a whole movie out of full-blown crosscutting? A sustained example at WFF was Bertrand Bonello’s Nocturama. (Major spoilers ahead.)

For the first fifty minutes or so, we follow nine young people silently threading their way through Paris. They ride the Métro, pace along the street, pair up, separate, crisscross, and assemble at four sites—a line of parked cars, an office building, a Ministry, a statue of Joan of Arc. They’re setting bombs.

We can identify them only through their looks and behaviors. David and Sarah touch fingers fleetingly on a train. We learn from flashbacks that Samir and Sabrina are sister and brother, and their friend is the younger African Mika, all presumably from emigrant families. Flashbacks also show them meeting to plan their action and, once set on course, dance the night away.

There’s an unexpected shooting, but the bombs go off more or less as planned. The group assembles in an upscale department store to meet another confederate, the security guard Omar who will host them overnight. This brief “nodal” moment of unification melts away. Crosscutting follows them as they wander from floor to floor in a parallel to their passages through Paris.

The first section merges the art cinema’s best friend, the prolonged walk, with a thriller-based suspense: we don’t really know what they’re up to until we see a pistol at around 18 minutes and bomb materials somewhat later. The threads knot when we see a quick montage of the bombs.

This fine-grained crosscutting looks ahead to the fragmentary handling of the action in the department store, where the moving spotlight shifts rapidly as the conspirators disperse, assemble in pairs or trios, and disperse again.

Crosscutting is the principal way filmmakers imply simultaneous action, but a lesser option, often favored by Brian De Palma, is the split screen. Bonello uses this device to show the result of the bombings. The shot looks forward to the quiet surveillance-camera display in the security office as the police prowl the shopping aisles. We see the kids moving from quadrant to quadrant, with an occasional flare marking a nearly soundless kill.

The terrorists’ motives are barely sketched, and they’re a cross-section of middle-class and working-class kids. Some are unemployed, others have low-end jobs, while others are on track for professional careers. A flashback shows several, perhaps meeting for the first time, while waiting for job interviews. The film’s second large part paints them as victims of consumer lust as they try on upscale fashions and make-up, but the point isn’t hammered home. To some extent they’re just killing time in what they think is a safe house.

Nocturama‘s crosscut climax balances, in more condensed form, the first section, as the conspirators are discovered by the police. At one point, an innocent who has come upon them by accident gets more emphasis than the gang members. His final moments are replayed through multiple viewpoints, as if the stranger’s fate drives home to them what death looks like up close. Soon enough each one will know exactly.

It might seem the height of film nerdery to join up films seen at a festival through their different uses of one technique. But is it any more of a strain than those journalistic accounts of how a batch of festival choices reflects The Way We Live Now? Every Berlin or Cannes or Toronto seems to bring forth think pieces looking for a common thread among radically different films, hoping to find today’s social mood in movies begun perhaps years before? Like most zeitgeist readings, they’re pretty easy to whip up.

But technical choices are more concrete than hints of the mood of the moment. Moreover, if you’re interested in cinema as an art, it can be enlightening to reveal the variety of creative options that are still available. The art may not progress, but our understanding of it can. And it’s heartening to find filmmakers refreshing traditional techniques to give us powerful experiences.

Just as important, studying how our contemporaries find new possibilities in something as old as crosscutting can encourage ambitious filmmakers today. The menu is open-ended. There’s always something new, and rewarding, to be done.

We had a wonderful time at this year’s Wisconsin Film Festival. Thanks to all the people and institutions involved, and especially the programmers Jim Healy, Mike King, and Ben Reiser. Each year it just gets better.

Wigilia is currently streaming on Amazon. Nocturama has just gotten a US distributor, the enterprising Grasshopper Film.

Good discussions of interlaced plotting in medieval tales are William W. Ryding, Structure in Medieval Narrative (Mouton, 1971) and Carol J. Clover, The Medieval Saga (Cornell University Press, 1982). Yes, it’s Carol “Final Girl” Clover.

For Tarantino’s use of block construction and time-bending, go here. We discuss Nolan’s penchant for crosscutting in this entry and that one, and at greater length in our e-book on his work.

Off-center 2: This one in the corner pocket

DB here, again:

We got a keen response to my entry on widescreen composition in Mad Max: Fury Road. Thanks! So it seemed worthwhile to look at composition in the older format of 4:3, good old 1.33:1–or rather, in sound cinema, 1.37: 1.

The problem for filmmakers in CinemaScope and other very wide processes is handling human bodies in conversations and other encounters (such as stomping somebody’s butt in an an action scene). You can more or less center the figures, and have all that extra space wasted. Or you can find ways to spread them out across the frame, which can lead to problems of guiding the viewer’s eye to the main points. If humans were lizards or Chevy Impalas, our bodies would fit the frame nicely, but as mostly vertical creatures, we aren’t well suited for the wide format. I suppose that’s why a lot of painted and photographed portraits are vertical.

By contrast, the squarer 4:3 frame is pretty well-suited to the human body. Since feet and legs aren’t usually as expressive as the upper part of the body, you can exclude the lower reaches and fit the rest of the torso snugly into the rectangle. That way you can get a lot of mileage out of faces, hands and arms. The classic filmmakers, I think, found ingenious ways to quietly and gracefully fill the frame while letting the actors act with body parts.

Since I’m watching (and rewatching) a fair number of Forties films these days, I’ll draw most of my examples from them. after a brief glance backward. I hope to suggest some creative choices that filmmakers might consider today, even though nearly everybody works in ratios wider than 4:3. I’ll also remind us that although the central area of the frame remains crucial, shifts away from it and back to it can yield a powerful pictorial dynamism.

Movies on the margins

Early years of silent cinema often featured bright, edge-to-edge imagery, and occasionally filmmakers put important story elements on the sides or in the corners. Louis Feuillade wasn’t hesitant about yanking our attention to an upper corner when a bell summons Moche in Fantômas (1913). A famous scene in Musketeers of Pig Alley (1912) shows Griffith trying something trickier. He divides our attention by having the Snapper Kid’s puff of cigarette smoke burst into the frame just as the rival gangster is doping the Little Lady’s drink. She doesn’t notice either event, as she’s distracted by the picture the thug has shown her, but there’s a chance we miss the doping because of the abrupt entry of the smoke.

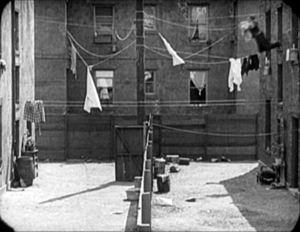

In Keaton’s maniacally geometrical Neighbors (1920), the backyard scenes make bold (and hilarious) use of the upper zones. Buster and the woman he loves try to communicate three floors up. Early on we see him leaning on the fence pining for her, while she stands on the balcony in the upper right. Later, he’ll escape from her house on a clothesline stretched across the yard. At the climax, he stacks up two friends to carry him up to her window.

Thankfully, the Keaton set from Masters of Cinema preserves some of the full original frames, complete with the curved corners seen up top. It’s also important to appreciate that in those days there was no reflex viewing, and so the DP couldn’t see exactly what the lens was getting. Framing these complex compositions required delicate judgment and plenty of experience.

Later filmmakers mostly stayed away from corners and edges. You couldn’t be sure that things put there would register on different image platforms. When films were destined chiefly for theatres, you couldn’t be absolutely sure that local screens would be masked correctly. Many projectors had a hot spot as well, rendering off-center items less bright. And any film transferred to 16mm (a strong market from the 1920s on) might be cropped somewhat. Accordingly, one trend in 1920s and 1930s cinematography was to darken the sides and edges a bit, acknowledging that the brighter central zone was more worth concentrating on.

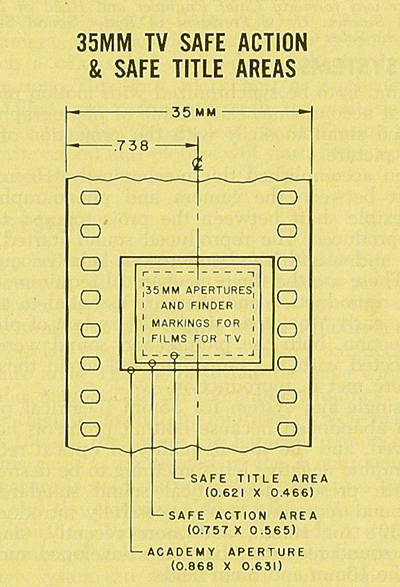

That tactic came in handy with the emergence of television, which established a “safe area” within the film frame for video transmission. TV cropped films quite considerably; cinematographers were advised in 1950 that

All main action should be held within about two-thirds of the picture. This prevents cut-off and tube edge distortion in television home receivers.

Older readers will remember how small and bulging those early CRT screens were.

By 1960, when it was evident that most films would eventually appear on TV, DP’s and engineers established the “safe areas” for both titles and story action. (See diagram surmounting this section.) Within the camera’s aperture area, which wouldn’t be fully shown on screen, the safe action area determined what would be seen in 35mm projection. “All significant action should take place within this portion of the frame,” says the American Cinematographer Manual.

Studio contracts required that TV screenings had to retain all credit titles, without chopping off anything. This is why credit sequences of widescreen films appear in widescreen even in cropped prints. So the safe title area was marked as what would be seen on a standard home TV monitor. If you do the math, the safe title area is indeed 67.7 % of the safe action area.

These framing constraints, etched on camera viewfinders, would certainly inhibit filmmakers from framing on the edges or the corners of the film shot. And when we see video versions of films from the 1.37 era (and frames like mine coming up) we have to recall that there was a bit more all around the edges than we have now.

All-over framing, and acting

Yet before TV, filmmakers in the 40s did exploit off-center zones in various ways. Often the tactic involved actors’ hands–crucial performance tools that become compositional factors. In His Girl Friday (1940), Walter Burns commands his frame centrally, yet when he makes his imperious gesture (“Get out!”) Hawks and DP Joseph Walker (genius) have left just enough room for the left arm to strike a new diagonal.

The framing of a long take in The Walls of Jericho (1948) lets Kirk Douglas steal a scene from Linda Darnell. As she pumps him for information, his hand sneaks out of frame to snatch bits of food from the buffet.

As the camera backs up, John Stahl and Arthur Miller (another genius) give us a chance to watch Kirk’s fingers hovering over the buffet. When Linda stops him with a frown, he shrugs, so to speak, with his hands. (A nice little piece of hand jive.)

The urge to work off-center is still more evident in films that exploit vigorous depth staging and deep-focus cinematography. Dynamic depth was a hallmark of 1940s American studio cinematography. If you’re going to have a strong foreground, you will probably put that element off to one side and balance it with something further back. This tendency is likely to empty out the geometrical center of the shot, especially if only two characters are involved. In addition, 1940s depth techniques often relied on high or low angles, and these framings are likely to make corner areas more significant. Here are examples from My Foolish Heart (1950): a big-head foreground typical of the period, and a slightly high angle that yields a diagonal composition.

Things can get pretty baroque. For Another Part of the Forest (1948), a prequel to The Little Foxes (1941), Michael Gordon carried Wyler’s depth style somewhat further. The Hubbard mansion has a huge terrace and a big parlor. Using the very top and very bottom of the frame, a sort of Advent-calendar framing allows Gordon to chart Ben’s hostile takeover of the household, replacing the patriarch Marcus at the climax. The fearsome Regina appears in the upper right window of the first frame, the lower doorway of the second.

In group scenes, several Forties directors like to crowd in faces, arms, and hands, all spread out in depth. I’ve analyzed this tendency in Panic in the Streets (1950), but we see it in Another Part of the Forest too. Again, character movement can reveal peripheral elements of the drama.

At the dinner, Birdie innocently thanks Ben for trying to help her family with their money problems and bolts from the room, going out behind Ben’s back. The reframing brings in at the left margin a minor character, a musician hired to entertain for the evening. But in a later phase of the scene he will–still in the distance–protest Marcus’s cruelty, so this shot primes him for his future role.

At one high point, the center area is emptied out boldly and the corners get a real workout. On the staircase, the callow son Oscar begs Marcus for money to enable him to run off with his girlfriend. (As in Little Foxes, the family staircase is very important–as it is in Lillian Hellman’s original plays.) Ben watches warily from the bottom frame edge. Nobody occupies the geomentrical center.

Later, on the same staircase, Ben steps up to confront his father while Regina approaches. It’s an odd confrontation, though, because Ben is perched in the left corner, mostly turned from us and handily edge-lit. Marcus turns, jammed into the upper right. Goaded by Ben’s taunts, he slaps Ben hard. Here’s the brief extract.

The key action takes place on the fringes of the frame, while the lower center is saved for Regina’s reaction–for once, a more or less normal human one. Even allowing for the cropping induced by the video safe-title area, this is pretty intense staging.

The corners can be activated in less flagrant ways. Take this scene from My Foolish Heart. Eloise has learned that her lover has been killed in air maneuvers. Pregnant but unmarried, she goes to a dance, where an old flame, Lew asks her to go on a drive. They park by the ocean, and she succumbs to him. Here’s the sequence as directed by Mark Robson and shot by Lee Garmes (another genius).

In the fairly conventional shot/ reverse-shot, the lower left corner is primed by Eloise’s looking down at the water and Lew’s hand stealing around her.

Later, when Lew pulls her close, (a) we can’t see her; (b) his expression doesn’t change and is only partly visible; so that (c) his emotion is registered by the passionate twist of his grip on her shoulder. Lew’s hand comes out from the corner pocket.

Perhaps Eloise is recalling another piece of hand jive, this time from her lost love.

For many directors, then, every zone of the screen could be used, thanks to the good old 4:3 ratio. It’s body-friendly, human-sized, and can be packed with action, big or small.

Mabuse directs

In other entries (here and here) I’ve mentioned one of the supreme masters of off-center framing, Fritz Lang. Superimpose these two frames and watch Kriemhilde point to the atomic apple in Cloak and Dagger (1946).

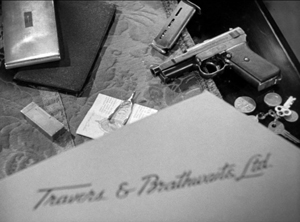

From the very start of Ministry of Fear (1944), the visual field comes alive with pouches, crannies, and bolt-holes. The first image of the film is a clock, but when the credits end the camera pulls back and tucks it into the corner as the asylum superintendant enters. (The shot is at the end of today’s entry.) Here and elsewhere, Lang uses slight high angles to create diagonals and corner-based compositions.

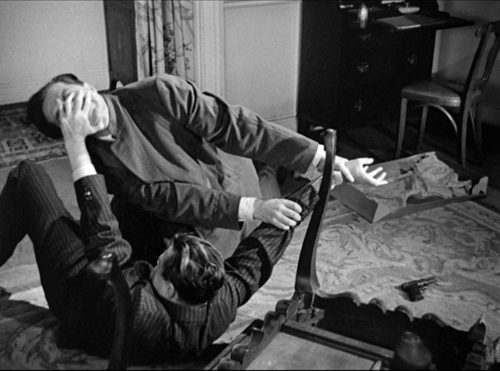

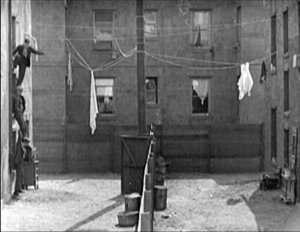

In the course of the film, pistols circulate. Neale lifts one from Mrs. Bellane (strongly primed, upper left), keeps her from appropriating it (lower center), and secures it nuzzling his left knee (lower right).

Later, Neale’s POV primes the placement of a pistol on the desktop (naturally, off-center), so that we’re trained to spot it in a more distant shot, perilously close to the hand of the treacherous Willi.

Amid so many through-composed frames, an abrupt reframing calls us to attention. Unlike Hawks and Walker’s handling of Walter in His Girl Friday, Lang and his DP Henry Sharp (great name for a DP, like Theodore Sparkuhl and Frank Planer) gives things a sharp snap when Willi raises his hand.

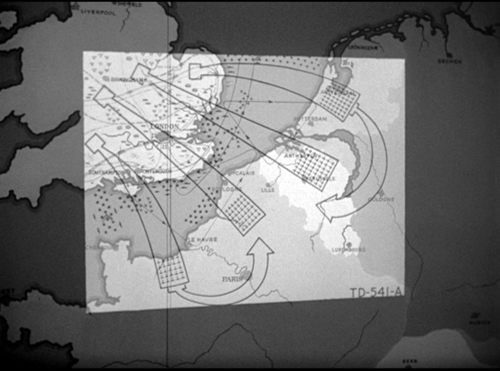

Lang drew all his images in advance himself, not trusting the task to a storyboarder. Avoiding the flashy deep-focus of Wyler and company, he created a sober pictorial flow that can calmly swirl information into any area of the frame. It’s hard not to see the stolen attack maps, surmounting today’s entry, as laying bare Lang’s centripetal vectors of movement. No wonder in the second frame up top, as Willi and Neale struggle in a wrenching diagonal mimicking the map’s arrows, that damn pistol strays off on its own.

Sometimes film technology improves over time. For instance, digital cinema today is better in many respects than it was in 1999. But not all changes are for the better. The arrival of widescreen cinema was also a loss. Changing the proportions of the frame blocked some of the creative options that had been explored in the 4:3 format. Occasionally, those options could be modified for CinemaScope and other wide-image formats; I trace some examples in this video lecture. But the open-sided framings in most widescreen films today suggest that most filmmakers haven’t explored the wide format to the degree that classical directors did with the squarish one.

More generally, it’s worth remembering that the film frame is a basic tool, creating not only a window on a three-dimensional scene but also a two-dimensional surface that requires composition–either standardized or more novel. Instead of being a dead-on target, the center can be an axis around which pictorial forces push and pull, drift away and bounce around. After all, we’re talking about moving pictures.

Thanks to Paul Rayton, movie tech guru, for information on 16mm cropping.

My image of the safe areas and the second quotation about them is taken from American Cinematographer Manual 1st ed., ed. Joseph C. Mascelli (Hollywood: ASC, 1960), 329-331. The older quotation about cropping for television comes from American Cinematographer Handbook and Reference Guide 7th ed., ed. Jackson J. Rose (Hollywood: ASC, 1950), 210.

I hope you noticed that I admirably refrained from quoting Lang, who famously said that CinemaScope was good only for…well, you can finish it. Of course he says it in Godard’s Contempt (1963), but he told Peter Bogdanovich that he agreed.

[In ‘Scope] it was very hard to show somebody standing at a table, because either you couldn’t show the table or the person had to be back too far. And you had empty spaces on both sides which you had to fill with something. When you have two people you can fill it up with walking around, taking something someplace, so on. But when you have only one person, there’s a big head and right and left you have nothing (Who the Devil Made It (Knopf, 1997), 224).

For more on the stylistics and technology of depth in 1940s American film, see The Classical Hollywood Cinema: Film Style and Mode of Production to 1960 (Columbia University Press, 1985), which Kristin and I wrote with Janet Staiger, Chapter 27, and my On the History of Film Style (Harvard University Press, 1997), Chapter 6. Many blog entries on this site are relevant to today’s post; search “deep-focus cinematography” and “depth staging.” If you want just one for a quick summary, try “Problems, problems: Wyler’s workarounds.” Some of the issues discussed here, about densely packing the frame, are considered more generally in “You are my density,” which includes an analysis of a scene in Lang’s Hangmen Also Die (1943).

Ministry of Fear (1944).

What next? A video lecture, I suppose. Well, actually, yeah….

DB here:

We’ve said several times that this website is an ongoing experiment. We started just by posting my CV and essays supplementing my books. Then came blogs. We quickly added illustrations to our entries, mostly frame enlargements and grabs. Eventually, video crept in. In 2011 we ran Tim Smith’s dissection of eye-scanning in There Will Be Blood. Last year, in coordination with our new edition of Film Art: An Introduction, we added online clips-plus-commentary (an example is on Criterion’s YouTube channel), and near the end of the year Erik Gunneson and I mounted a video essay on techniques of constructive editing.

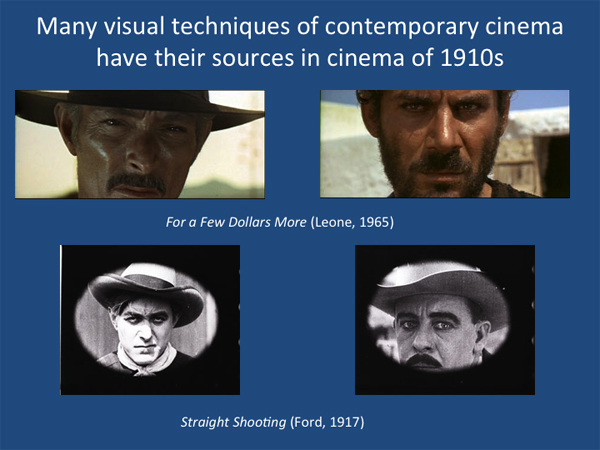

Today something new has been added. I’ve decided to retire some of the lectures I take on the road, and I’ll put them up as video lectures. They’re sort of Net substitutes for my show-and-tells about aspects of film that interest me. The first is called “How Motion Pictures Became the Movies,” and it’s devoted to what is for me the crucial period 1908-1920. It quickly surveys what was going on in cinema over those years before zeroing in on the key stylistic developments we’ve often written about here: the emergence of continuity editing and the brief but brilliant exploration of tableau staging.

The lecture isn’t a record of me pacing around talking. Rather, it’s a PowerPoint presentation that runs as a video, with my scratchy voice-over. I didn’t write a text, but rather talked it through as if I were presenting it live. It nakedly exposes my mannerisms and bad habits, but I hope they don’t get in the way of your enjoyment.

“How Motion Pictures Became the Movies” is designed for general audiences. I’ve built in comments for specialists too, in particular, some indications of different research approaches to understanding this period of change.

The talk runs just under 70 minutes, and it’s suitable for use in classes if people are inclined. I think it might be helpful in surveys of film history, courses on silent cinema, and courses on film analysis. If a teacher wants to break it into two parts, there’s a natural stopping point around the 35-minute mark.

Some slides have several images laid out comic-strip fashion, so the presentation plays best on a midsize display, like a desktop or biggish laptop. A couple of tests suggest that it looks okay projected for a group, but the instructor planning to screen it for a class should experiment first.

I plan to put up other lectures in a similar format, with HD capabilities. Next up is probably a talk about the aesthetics of early CinemaScope. I’d then like to spin off this current one and offer three 30-minute ones that go into more depth on developments in the 1910s.

The video is available at the bottom of this entry, but it’s also available on this page. There I provide a bibliography of the sources I mention in the course of the talk, as well as links to relevant blogs and essays elsewhere on the site.

If you find this interesting or worthwhile, please let your friends know about it. I don’t do Twitter or Facebook, but Kristin participates in the latter, and we can monitor tweets. Thanks to Erik for his dedication to this most recent task, and to all our readers for their support over the years.

A variation on a sunbeam: Exploring a Griffith Biograph film

Kristin here:

On April 21 a young Spanish film student uploaded his remarkable little film, Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 onto Vimeo. There it languished, like so many contributions to the internet, good and bad. In the first four months of its presence on the site, it attracted 17 views.

Then, on August 17, Variation was viewed twice and earned its first “Like.” (One has to be a member of Vimeo to Like a film, so one cannot assume that none of its viewers to that point had enjoyed it.) That first Like, and perhaps both views were by Kevin B. Lee, best known for his many video essays on classic films. (See here for an index; I contributed the commentary for the La roue entry.) Over the next week and a half there were five additional views, four on August 28. I suspect some or all of these last ones were repeat visits by Kevin, since on August 31 he was the first to post an essay on Variation: The Sunbeam, David W. Griffith, 1912 (hereafter Variation), along with some information on its maker, Aitor Gametxo.

The immediate result was a flurry though not a stampede of views: 33 on August 31, along with a second Like; and 15 on September 1, with a third Like. One of those views and the third Like were mine. On September 2, there were 12 views, dwindling to 2 on September 3 and 1 on September 4.

(Among the viewers after the Fandor entry was Evan Davis, University of Wisconsin-Madison film-studies alumnus, who read Lee’s blog, watched the film, and passed the links along to us. Thanks, Evan!)

It’s a pity that more attention has not been paid to this charming, clever, and informative film. Not only would people enjoy it, but it could easily be used as a tool for those teaching, or indeed researching silent cinema. So here’s my bid to help it go viral.

Variation is a found-footage film based on Griffith’s American Biograph one-reeler The Sunbeam, made in December, 1911, and released on March 18, 1912. It is not among the most famous of the nearly 500 one- and two-reelers Griffith directed at AB between 1908 and 1913, but it’s better known than most. In the opening, a sick mother dies, and her little girl, thinking her mother is asleep, goes out into the hallways of their working-class apartment building. She tries to find someone to play with, but everyone rebuffs her until she manages to charm two lonely people, a bachelor and spinster, who live opposite each other on the floor below the child’s home.

Aitor noticed three key things about the film. First, the action takes place in a very limited space, with the three apartments and hallway all close to each other. Second, the doorways through which the characters pass between these rooms are on the edges of the screen, so that when they exit through the doorway in one shot and after the cut enter the space on the other side of the doorway, there is often a sort of elusive match on action formed (what I termed a “frame cut” in The Classical Hollywood Cinema, p. 205 and figures 16.36 and 37). Third, and perhaps most importantly, Griffith was intercutting actions that were happening simultaneously, so that at many of the cuts, he jumped from the end of an action in one space back in time to catch up with what had been happening in another space. At times he would jump back twice if simultaneous actions were happening in three spaces.

Aitor has taken the individual shots and redone them, putting them into a grid of six small frames, three on the bottom and three at the top. Scenes in the child’s upstairs apartment are shown only in the upper left, the top of the stairway in the upper center, and the two apartments on the ground floor at the sides, with the hallway and bottom of the stairs between them. (See above.) These are roughly the actual positions these spaces occupy in relation to each other in the building represented in the film. The shots run in their true temporal relations, so that there is no jumping back.

I suggest that before reading further, you watch The Sunbeam, especially if you have never seen it before. It would be impossible, I think, to entirely follow the story just from seeing Variation. The shots are so reduced in size to fit into the grid that small but important gestures and details get lost. Here is the original film, from YouTube.

With Aitor’s kind permission, we present his take on Griffith’s one-reeler. (The Sunbeam runs about 15 minutes, but due to the simultaneous presentation of many shots, Variation is only about 10 minutes.) Click on the “Vimeo” logo in the lower right corner for a larger image:

A fascinating film, isn’t it? I think many viewers would reach the end of Variation and wish that the same sort of presentation could be created for other films–at least, early ones that are short enough to make such rearrangement viable. Kevin Lee is enthusiastic about the idea: “Imagine this multi-dimensional, real-time approach being applied to footage from other films, as a way of not just mapping out scenes in a movie, but also gaining insight into filmmaking technique.” It might be possible, but the six-rectangle grid used here would not work for very many films. Aitor has chosen the ideal film for such an approach. Not only are there a limited number of significant characters, but they also live in the same building, with three rooms and a hallway, all viewed from the same direction, making them fit perfectly into a “doll-house” style scene.

Had Griffith not routinely shot directly toward the back wall in all his sets, placing the shots directly side by side across the grid would not work, at least not so neatly. Many other directors of this era were exploring shooting into corners and having doorways for entrances and exits centered at the rear. Perhaps filmmakers like Aitor could still place different shots side by side, but the actors’ movements from one space to another would not be so smooth. One of the attractions of Variation is that those movements are smooth, and as a result the action plays as if it were part of a continuous, “real” film.

Even other Griffith films shot in the style of The Sunbeam would be far more difficult to lay out on a similar grid. Longer rows of more rectangles would need to be added, or the upper row would have to represent actions taking place at a distance and the lower one actions taking place within a building. (I’m thinking here of something like The Lonely Villa, where action in a series of contiguous rooms is intercut with the husband’s race from a distant locale back to his house.) The placement of the bachelor’s room opposite the spinster’s, on either side of the hallway through which all of the minor characters pass, is crucial to Aitor’s project. A complex film with many characters and locales might create a grid with rectangles too small to be grasped by the viewers. Ways of indicating techniques like flashbacks would have to be devised. And of course, not all films contain simultaneous action.

Variation has some technical disadvantages. The titles appear in the upper right corner of the screen, since no locale opposite the child’s apartment is ever shown. The titles are small and difficult to read, and since they pop up simultaneously with the action, it’s almost impossible to read them anyway. One cannot tell where the titles originally came in the flow of shots, though one can always check the original film. Another problem is the cropping of the images on all four sides. The DVD copies are somewhat cropped, and more of the image is eliminated in the Variation frames; the action of the little heroine hiding a hairpiece in the spinster’s home, an important motivation for later action, can barely be grasped because it is so small a detail and happens at the very bottom of the frame; in the DVDs it can be clearly seen.

The Griffith Project and our knowledge of his techniques

I do not intend by any means to diminish what Aitor has accomplished when I say that the three main techniques he works from have been known to Griffith scholars for years. Variation offers a new way of examining and explaining those techniques.

Griffith has, of course, been one of the most closely studied filmmakers in history. A vast summary of and contribution to the research on Griffith was recently compiled by “Il Giornate del Cinema Muto” film festival in Pordenone, Italy. From 1997 to 2008, the festival mounted a nearly complete retrospective of Griffith’s work, hampered only by those films which still exist only as negatives or in other forms that could not be projected. A team of experts divided up the work and wrote extensive program notes for every single film Griffith made, whether it was shown at the festival or not. The notes, some more general essays, and Griffith’s writings were edited into twelve volumes jointly published by the festival and the British Film Institute (1999-2008). I had the privilege of contributing notes to most of the volumes, and although I cannot claim to know Griffith’s entire œuvre intimately, I got to know the films assigned to me quite well and learned a great deal about his methods.

The program notes for The Sunbeam were written by Griffith specialist Russell Merritt (Volume 5, 2001). As these excerpts from his description of the film’s setting indicate, the doll-house arrangement of the sets in The Sunbeam were distinctive, but not atypical of Griffith’s approach:

This was the second of Griffith’s three December tenement films (falling between The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls); spatially it is his simplest. Griffith uses only five setups (fewer than half what he works with in The Transformation of Mike and The String of Pearls.), but far from feeling cramped or monotonous, the three rooms and two hallways spaces seem perfectly designed for the playful romps, the practical jokes, and the unfolding of the gentle love story.

By 1911, the Griffith apartment set had developed a personality of its own, or more precisely, had become both distinctive and flexible enough to accommodate a broad range of narratives. Griffith’s planimetric style, with the camera always aimed straight on into the back wall with at least one side of the room aligned to the margin of the frame, had become as much a Biograph signature as the last-minute rescue, the fade-out, parallel editing, and the stock company of actors [….] In The Sunbeam, the familiar hallway and one-room apartments turn into something resembling a row of a child’s wooden blocks or the rooms in a child’s dollhouse, albeit with a dead mother in the garret. In each space, whether the hallway, the spinster’s apartment or the bachelor’s one-room across the hall, there is something to play with or play upon. The prank with the string stretched across the hallway literally links the two apartments and provides the perfect center of a the film–a gag that depends upon the mirror symmetries of the rooms and the tug-of-war actions of the two incipient sweethearts. (p. 196)

For the prank with the stretched string made symmetrical spatially as well as temporally, see below.

Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs’ book Theatre to Film (1997) points out that cutting among multiple adjacent interior rooms was typical of Griffith’s work in this period: “By early [1911] a film like Three Sisters has a climactic sequence of 28 shots alternating between three set-ups–long-shot views of three rooms, a kitchen, a hall, and a bedroom, which movements from room to room that coincide with cuts establish as side by side.” (p. 189) My own notes for The Griffith Project volumes discuss adjacent sets and room-to-room movements using frame cuts. (See the end of this entry for a list.)

Griffith’s use of editing to convey simultaneous events, as well as to portray thoughts and flashbacks has been extensively discussed in the literature on the director.

What is remarkable is that a 22-year-old film student has noticed these devices and found a simple, elegant method to demonstrate what we already knew, but with greater precision and vividness than could be done with prose analysis. To experts, that is what should make Aitor’s film so appealing.

For example, the precision of Griffith’s matches on action at the frame cuts is illustrated time and again in Variation:

Were it not for the fact that Griffith’s camera is closer to the action in the smaller hallway set than it is in the two outer rooms, the spinster’s move through the door would almost appear to be a single smooth glide. Unless one freezes the frame, as I have done here, some of these movements look uncannily continuous.

For those teaching or reading Film Art: An Introduction, Variation also provides a clear example of story time versus plot time. Griffith’s The Sunbeam presents us plot time, with its jumps backward to cover all the action in multiple locales. Aitor’s film presents story action as we ordinarily would reconstruct it only in our minds. Usually we describe story action with synopses or outlines. To see it played out in real time is a rare treat.

The filmmaker

Aitor has a blog, which contains primarily many lovely still photographs taken in Spain, Ireland, and the United Kingdom. It offers, however, minimal information about him. Kevin Lee wrote to ask him for information, which is included in the Fandor entry linked above. I also emailed Aitor with some questions to further contextualize Variation, and he provided a short summary of his background and his interest in Griffith.

My name is Aitor Gametxo. I was born in Bilbao in 1989 and have been living in Lekeitio. I started the Communication and Film degree in the University of the Basque Country, but I moved to the University of Barcelona to finish it this year. I’m currently living and working in Barcelona, and I’m going to do a “Creative Documentary” masters degree this upcoming year. I really enjoy taking pictures of everyday things and places, as a way of reporting reality. I also love film, specially documentaries, found footage films and cinema-essay pieces. I honestly believe in the power films have to make us think about things. Not only because of the topic the film is about, but also about the way in which the film is made (a kind of dialectics between Bill Nichols’ expository and reflexive modes). I love watching old (and odd) films and thinking about things that are different from the purpose they were created for. (As I told Kevin) we are able to take some footage which is temporally and geographically unconnected to us and remodel, or refix, or remix… it, giving birth to another work. This is the way I see the found-footage praxis.

About this particular film, The Sunbeam, I watched it for the first time just before doing the variation. I knew other works made by Griffith, such as “Intolerance” (quoted in several film history books). But this was unknown for me, so that the first watching was crucial. While I was enjoying it, I was wondering what the place where it was shot looked like. I suddenly imagined it as a two-floor house, where the characters cross in some moments. Also the doors were essential to fix one part with another. This was the main idea where I worked on. It was great fun doing it.

The result is this variation in real-time action of the classic work where we can see how Griffith worked on. It’s like returning back to Griffith’s mind, to the first idea, as he imagined one hundred years ago (!) how The Sunbeam would look like. This is the magic of cinema.

My contributions to The Griffith Project‘s program notes for the Biograph years are these. In Volume 2, January-June 1909: Those Boys; The Fascinating Mrs. Francis; Those Awful Hats; The Cord of Life; The Brahma Diamond; Politician’s Love Story; Jones and the Lady Book Agent; His Wife’s Mother; The Golden Louis; and His Ward’s Love. In Volume 3, July-December 1909: Lines of White on a Sullen Sea; In the Watches of the Night; What’s Your Hurry?; Nursing a Viper; The Light That Came; The Restoration. In Volume 4, 1910: A Child’s Faith; The Italian Barber; His Trust; His Trust Fulfilled; The Two Paths; and Three Sisters. In Volume 5, 1911: The Lonedale Operator; The Spanish Gypsy; The Broken Cross; The Chief’s Daughter; A Knight of the Road; and Madame Rex. In Volume 6, 1912: The Unwelcome Guest; The New York Hat; My Hero; and The Burglar’s Dilemma. In Volume 7, 1913: The Hero of Little Italy; The Perfidy of Mary; and A Misunderstood Boy.

Like the other contributors, I found myself dealing with a few famous films (e.g., the wonderful Lines of White on a Sullen Sea) and others that were largely unknown. Each little cluster of titles assigned to us consisted of films that had been made sequentially, so that each of us could get an intensive look into Griffith’s work over the course of a few weeks. It proved to be a rewarding way of approaching the study of the director. The general editor for the series was Paulo Cherchi Usai, assisted by Cindi Rowell.

The Sunbeam is also available in the U.S. in two DVD sets: Image’s “D. W. Griffith: Years of Discovery: 1909-1913” and Kino’s “D. W. Griffith’s Biograph Shorts Special Edition.” (The discs can also be bought separately.)