Archive for the 'Directors: De Palma' Category

Lie to me: MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE

Mission: Impossible (1996).

DB here:

Filmmakers rightly consider themselves problem-solvers. They deal with budget limits, scheduling constraints, temperamental staff and casts, and balky equipment. Some problems come with financial demands; others are self-imposed, such as: “Tell a story confined to a single room.” The artistic problems often demand solutions that guide viewers toward clarity, comprehension, and emotional impact.

Suppose your story situation is this. Character A is telling a story, but it’s a lie. Character B realizes it’s a lie, but doesn’t signal that recognition. This is really two problems in one: How do you tell the audience A is lying? And how do you convey that B knows but doesn’t reveal that knowledge?

These are at the crux of in an intriguing sequence in Mission: Impossible. The solutions found by screenwriter David Koepp and director Brian DePalma show how even a straightforward “entertainment movie” can pose interesting questions about cinematic expression.

Spoilers ahead. But I bet you’ve seen this movie.

The problem(s)

The Impossible Mission team has been sent to Prague, purportedly to retrieve a digital disc listing all CIA agents in Europe. They don’t know that this assignment is a pretext for finding a mole, a rogue agent who is selling secrets to foreign interests. While infiltrating a state gala, most of the team is killed. Only Ethan Hunt, point man in the mission, and Claire Phelps, the wife of the team leader Jim Phelps, survive. The IMF chief Kittridge accuses Ethan of being the mole so Ethan, along with Claire, needs to flee. But out of devotion to duty he insists on finding the mole. He learns that the mole under the alias of Job has offered to sell the NOC list to Max, a dealer in covert information. The bulk of the plot revolves around Ethan’s efforts to induce Max to reveal Job, which Ethan can do only by offering Max the NOC list—while at the same time making sure that it doesn’t really fall into Max’s hands.

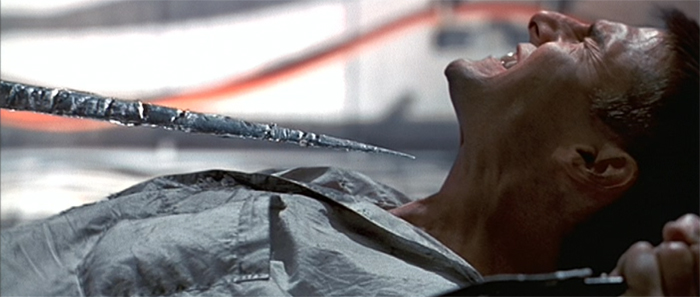

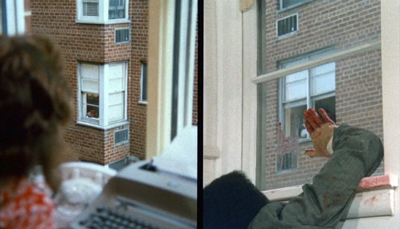

After a prologue, which I discussed in an earlier entry, the film’s first stretch revolves around the team’s invasion of the embassy party. As the scheme collapses, we see the deaths of the team members. Through cross-cutting and a moving-spotlight narration, the film shows us the technician Jack killed in an elevator shaft, Jim Phelps shot on a bridge and tumbling into the river, Sarah stabbed at a gate, and Hannah killed by a car bomb. The effects of these killings are registered largely through Ethan’s response. He hears Jack lose contact, watches video transmission of Jim’s bloody hands, finds Sarah impaled by a knife, and sees Hannah’s car explode. Later he, and we, will learn that Claire escaped.

At the start of the film’s climax, Ethan discovers that Jim Phelps is still alive. In a café, Jim explains that he survived the shooting and that he saw the killer: Kittridge. Kittridge is the mole, he claims. Jack brings Jim into his plan to meet Max on the Eurostar train and apparently give her the NOC list he’s stolen from Langley.

The twist is that Jim–Ethan’s mentor, friend, and surrogate father–is lying. He is Job the mole, and he has eliminated his own team, faking the attack on himself. Thanks to crosscutting, the first version of the attacks concealed from us the actions Jim takes to kill his colleagues. The narrative problems are: How and when to tell us of Jim’s treachery? And how to represent Ethan’s state of awareness? Is he misled by Jim’s account, or does he doubt it? And what is Claire’s role in all this?

Three solutions

Singin’ in the Rain (1952).

Every creative choice eliminates alternatives, and I’ve compared classical filmmaking to selecting from a menu of more or less favored options. That menu can offer filmmakers ways of solving narrative problems. One choice for the M:I revelation is simply to present Jim telling Ethan his lies in the café. Ethan then can react in horror, leaving us to assume that he doesn’t doubt him.

This option was actually tried out in an early script draft. Jim explains and Ethan, despite some hesitation (“Hold on, it’s taking me a minute to adjust here“), seems to accept his story. Only in their final confrontation on the Eurostar does Ethan reveal that he had long before figured out that Jim had betrayed the team. We had no inkling that in the café Ethan was merely pretending to accept Jim’s account. His awareness of Jim’s scheme was held back as a surprise.

Another narrative option appears in a later script draft. This time Jim’s explanation is accompanied by flashbacks illustrating his lies. He claims to have swum to shore, patched up his gunshot wound, and followed Ethan’s trail. He then tells Ethan it was Kittridge who shot him and killed Sarah, and these moments are illustrated with quick flashback imagery. These are lying flashbacks. As a neat fillip, two of these shots replay Ethan finding Sarah’s body nearby, as if to certify Jim’s story. “Ethan just stares at Phelps, his eyes wide with surprise.” Again, we’re led to think that Ethan trusts Jim’s tale, making the train confrontation a revelation of Ethan’s outplaying Jim.

We should remember that the Hollywood menu provides the lying flashback as an option, albeit rare. In Singin’ in the Rain, for instance, Don Lockwood’s voice-over interview portrays his early career as one of refined show-business accomplishment. “Dignity—always dignity.” But the images undercut this by showing him performing slapstick routines in burlesque. Since this is a comedy, we can understand that the film’s flashbacks are debunking his pretension. As for the second problem, that of conveying a listener’s skepticism, the present-time scenes reinforce the impression of Don’s puffery by showing his pal Cosmo’s eye-rolling reaction. Still, the interviewer and presumably the radio audience are taken in.

This second M:I script variant doesn’t include such hints that Ethan doubts Jim, so the problem of the conveying the listener’s true reaction is bypassed. But the final film supplies yet another solution.

After I drafted what you’ve just read, I heard from screenwriter David Koepp. I had written him to ask about the alterations, and he talked with De Palma about them.

Brian reminded me that the intention of the scene was built around an idea — can we show Jim lying, and simultaneously see Ethan figuring out those lies in his own mind? Without telling Jim that he knows it’s a lie, Ethan is picturing for us what the truth must (or might) have been. It’s a cool idea, and, typical of DePalma, highly visual. Actually seeing on screen versions of events that may or MAY NOT have happened is something we started playing around with in M:I, and then did to a greater degree in Snake Eyes, which we wrote right after that.

Neither one of us can remember in useful detail about why we might have tried several other versions first, but my guess is that the one with Jim simply verbalizing the lie was jettisoned in favor of images for obvious (and again, DePalma-esque) reasons, i.e., it’s better to see something than to hear it. The flashback showing Kittridge as the perpetrator was likely because we wanted to keep going for as long as possible with the character I’ve come to call the Principled Antagonist — POSSIBLY a villain, turns out not to be, but always diametrically opposed to the hero and his goals.

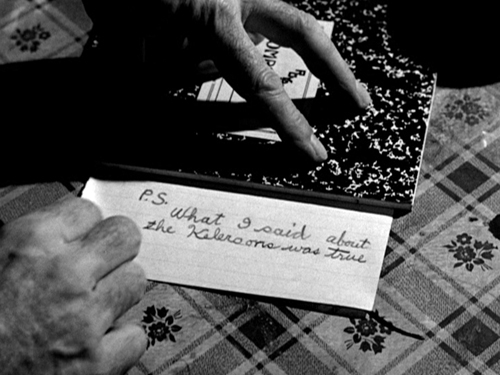

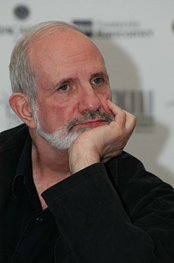

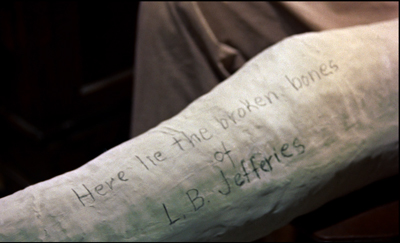

It was good to have my hunch confirmed, and to watch filmmakers sampling the menu of options from draft to draft. The final shooting script presents the new variant. Ethan, not Jim, spells out the scheme in dialogue. This leads Jim to assume that Ethan accepts Kittridge as the culprit. But the image track shows Jim committing the crimes. As the script puts it:

A reprise of PHELPS’s narrative only now ETHAN’S telling it and camera is showing the events as ETHAN sees they actually happened.

There’s still a potential obstacle, though. What if the viewer takes the flashbacks to show what really happened but doesn’t grasp that they’re Ethan’s imaginings? They might be only “the film telling us what really happened,” as in Singin’ in the Rain. How to establish that we’re following Ethan’s train of thought while he lies during his dialogue with Jim?

How to lie to a liar

Here’s the sequence as it appears in the film.

On the first problem, the sequence makes clear that Jim’s accusation of Kittridge is false. We’re introduced to Jim’s treachery with several shots showing Jim engineering Jack’s death in the elevator. Several more shots, stressed through slow-motion, illustrate how Jim faked his own death. And the knifing of Golitsyn and Sarah is attributed to Krieger. You can also argue that wily viewers will take Jim’s sidelong glance at Ethan as a tip-off to his treachery–a classic shot lingering on the Guilty One (as we’ve seen elsewhere).

Still, how can we be sure that Ethan sees “events as they actually happened”–especially since his shock and puzzlement at hearing Jim’s tale seem so genuine?

The sequence solves the second problem with two passages that strongly imply that the flow of images reflects what’s in Ethan’s mind.

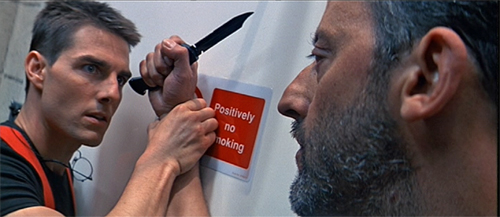

First, among phases of the stabbings at the gate, there’s the interpolated shot of Ethan pinning Krieger’s wrist to the wall during the Langley heist.

The two-shot of Ethan and Krieger, a flashback not part of Jim’s story, indicates Ethan’s realization that the knife he found in Sarah’s side was one of Krieger’s. Interestingly, this shot isn’t in the shooting script.

A stronger cue that we’re in Ethan’s mind comes with the “revised and corrected” version of Hannah’s death. Did “backup” take her out? The answer comes with a shot of Claire triggering the explosion and turning to look at the camera.

Claire’s look defies plausibility. It’s as if she is turning to glare, almost defiantly, at the Ethan who’s imagining this. Because he’s attracted to Claire, he wants to give her the benefit of the doubt. His imagination immediately proposes an alternative in which Jim sets off the bomb.

In the train at the climax, Jim will confirm Ethan’s hesitation: he was reluctant to suspect Claire. In the later stretch of the café scene, not included in my extract, the question of her loyalty is evoked as Jim urges Ethan to keep quiet about the scheme. When Ethan returns to Claire at the safe house, there remains the issue of whether her seduction of him is sincere or a further act of betrayal.

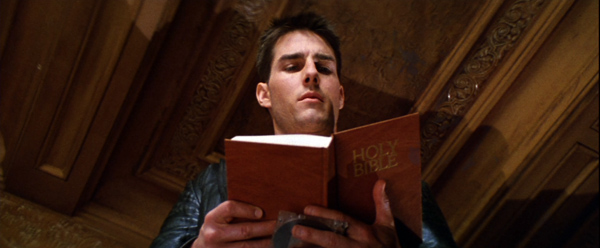

More immediately, the two problems are solved. Not only do we have the exposure of Jim’s lie, but we also get glimpses of how Ethan reconstructs what really happened. What makes this all particularly clever is that Ethan’s dialogue seems to confirm Jim’s tale. Ethan’s verbal duplicity is consistent with his talent for bluffing (as with Krieger and the fake NOC disc) and the earlier twinge of suspicion he had about Jim’s Palmer House Bible. When image and sound contradict one another here, we’re obliged to trust the image.

All of which charges Ethan’s final question–“Why, Jim? Why?”–with a double significance. Apparently asking about Kittridge’s motive, Ethan is pressing his mentor, almost desperately. Jim’s answer, about a refusal to accept the end of the Cold War, applies as much to him as to a CIA bureaucrat. We may not fully recognize it at the moment, but Ethan’s question marks the end of their friendship.

Someone might ask if every audience member will realize that the sequence solves both problems. Presumably even a ninny understands that Jim is lying; but maybe some viewers don’t get that Ethan is aware of the lie. My own inclination is to see the cues of Krieger’s knife and the revised version of Hannah’s death as pretty solid hints. Still, we might be in the realm, not unknown to Hollywood cinema, of a film that includes subtleties that not every viewer catches. I’m reminded of a screenwriter’s remark: “It’s not necessary that every viewer understand everything, only that everything can be understood.” This is presumably one reason we return to films and find more in them.

It’s also one reason it’s fun to analyze them.

Thanks to David Koepp and Brian De Palma for responding to my questions. David’s script archive is here.

The remark about understandable stories comes from Ted Elliott, as quoted in Jeff Goldsmith, “The Craft of Writing the Tentpole Movie,” Creative Screenwriting 11, no. 3 (May/ June 2004):, 53.

Mission: Impossible (1996).

The eyewitness plot and the drama of doubt

Looking is as important in movies as talking is in in plays. Thanks to optical point-of-view shots (POV) and reaction-shot cutting, you can create a powerful drama without words.

Everybody knows this, but sometimes it’s good to be reminded. (I did that here long ago.) Now I have another occasion to explore this terrain. But first: How I spent my summer vacation.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

After Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, I went to the annual Summer Film College in Antwerp. (Instagram images here.) I’ve missed a couple of sessions (the last entry is from 2015), but this year I returned for another dynamite program. There were three threads. Adrian Martin and Cristina Álvarez López mounted a spirited defense of Brian De Palma’s achievement. Tom Paulus, Ruben Demasure, and Richard Misek gave lectures on Eric Rohmer films. I brought up the rear with four lectures on other topics. As ever, it was a feast of enjoyable cinema and cinema talk, starting at 9:30 AM and running till 11 PM or so. The schedule is here.

Because I was fussing with my own lectures, I missed the Rohmer events, unfortunately. I did catch all the De Palma lectures and some of the films. Cristina and Adrian offered powerful analyses of De Palma’s characteristic vision and style. I especially appreciated the chance to watch Carlito’s Way again (script by friend of the blog David Koepp) and to see on the big screen BDP’s last film Passion, which looked fine. I confess to preferring some of his contract movies (Mission: Impossible, The Untouchables, Snake Eyes) to some of his more personal projects, but he takes chances, which is a good thing.

Two of my lectures had ties to my book Reinventing Hollywood. “The Archaeology of Citizen Kane” (should probably have been called “An Archaeology…) pulled together things touched on in blogs, topics discussed at greater length in books, and things I’ve stumbled on more recently. Maybe I can float the newer bits and pieces here some time.

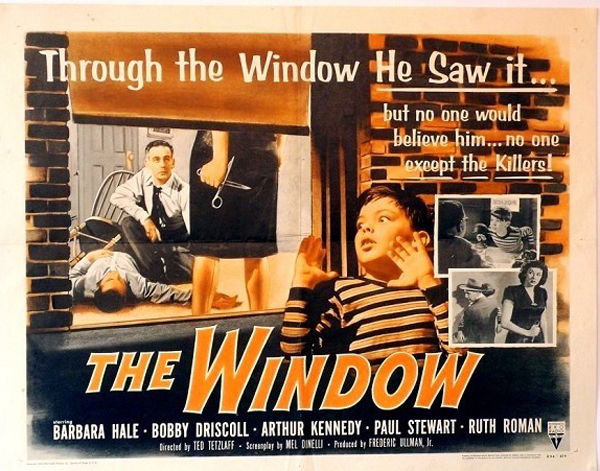

The other lecture took off from my book’s discussion of the emergence of the domestic thriller in the 1940s. We screened The Window (1949), a film that I hadn’t studied closely before. If you can see or resee it before reading on, you might want to do that. But the spoilers don’t come up for a while, and I’ll warn you when they’re impending.

Exploring the how

It is to the thriller that the American cinema owes the best of its inspirations.

Eric Rohmer

One strand of argument in Reinventing Hollywood goes like this.

During the 1930s Hollywood filmmakers mostly concentrated on adapting their storytelling traditions to sync sound and to new genres (the musical, the gangster film). By 1939 or so, those problems were largely solved. As a result, some ambitious filmmakers returned to narrative techniques that were fairly common in the silent era but had become rare in talkies. Those techniques–nonlinear plots, subjectivity, plays with viewpoint and overarching narration–were refined and expanded, thanks to sound technology and quite self-conscious efforts to create more complex viewing experiences.

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

Wuthering Heights, Our Town, Citizen Kane, How Green Was My Valley, Lydia, The Magnificent Ambersons, Laura, Mildred Pierce, I Remember Mama, Unfaithfully Yours, A Letter to Three Wives, and a host of B pictures and melodramas and war films and mystery stories and even musicals (Lady in the Dark) and romantic comedies (The Affairs of Susan)–all these and more attest to new efforts to tell stories in oblique, arresting ways. They seem to have taken to heart a remark from Darryl F. Zanuck (right). It forms the epigraph of my book:

It is not enough just to tell an interesting story. Half the battle depends on how you tell the story. As a matter of fact, the most important half depends on how you tell the story.

Put it another way. Very approximately, we might say that most 1930s pictures are “theatrical”–not just in being derived from plays (though many were) but in telling their stories through objective, external behavior. We infer characters’ inner lives from the way they talk and move, the way they respond to each other in situ. And the plot thrusts itself ever forward, chronologically, toward the big scenes that will tie together the strands of developing action. In this respect, even the stories derived from novels depend on this external, linear presentation.

In contrast, a lot of 1940s films are “novelistic” in shaping their plots through layers of time, in summoning a character or an omniscient voice to narrate the action, and in plunging us into the mental life of the characters through dreams, hallucinations, and bits of memory, both visual and auditory. We get to know characters a bit more subjectively, as they report their feelings in voice-over, or we grasp action through what they see and hear.

The distinction isn’t absolute. Some of these “novelistic” techniques were being applied on the stage as well, as a minor tradition from the 1910s on. I just want to signal, in a sketchy way, Hollywood’s 1940s turn toward more complex forms of subjectivity, time, and perspective–the sort of thing that became central for novelists in the wake of Henry James and Joseph Conrad.

In tandem with this greater formal ambition comes what we might call “thickening” of the film’s texture. Partly it’s seen in a fresh opennness to chiaroscuro lighting for a greater range of genres, to a willingness to pick unusual angles (high or low) and accentuate cuts. The thickening comes in characterization too, when we get tangled motives and enigmatic protagonists (not just Kane and Lydia but the triangles of Daisy Kenyon or The Woman on the Beach). There’s also a new sensitivity to audiovisual motifs that seem to decorate the core action–the stripey blinds of film noir but also symbolic objects (the snowstorm paperweights in Kane and Kitty Foyle, the locket in The Locket, the looming portraits and mirrors that seem to be everywhere). Add in greater weight put on density and details of staging, enhanced by recurring compositions, as I discuss in an earlier entry.

One genre that comes into its own at the period relies heavily on the new awareness of Zanuck’s how. That’s the psychological thriller.

I’ve written at length about this characteristic 1940s genre (see the codicil below), so I’ll just recap. The 1930s and 1940s saw big changes in mystery literature generally. The white-gloved sleuth in the Holmes/Poirot/Wimsey vein met a rival in the hard-boiled detective. Just as important was the growing popularity of psychological thrillers set in familiar surroundings. The sources were many, going back to Wilkie Collins’ “sensation fiction” and leading to the influential works by Patrick Hamilton (Rope, Hangover Square, Gaslight). In the same years, the domestic thriller came to concentrate on women in peril, a format popularized by Mary Roberts Rinehart and brought to a pitch by Daphne du Maurier. The impulse was continued by many ingenious women novelists, notably Elizabeth Sanxay Holding and Margaret Millar. The domestic thriller was a mainstay of popular fiction, radio, and the theatre of the period, so naturally it made its way into cinema.

Literary thrillers play ingenious games with the conventions of the post-Jamesian novel. We get geometrically arrayed viewpoints (Vera Caspary’s Laura, Chris Massie’s The Green Circle) and fluid time shifts (John Franklin Bardin’s Devil Take the Blue-Tail Fly). There are jolting switches of first-person narration (Kenneth Fearing’s The Big Clock), sometimes accessing dead characters (Fearing’s Dagger of the Mind). There are swirling plunges into what might be purely imaginary realms (Joel Townsley Rogers’ The Red Right Hand).

Ben Hecht remarked that mystery novels “are ingenious because they have to be.” Formal play, even trickery, is central to the genre, and misleading the reader is as important in a thriller as in a more orthodox detective story. No wonder that the genre suited filmmakers’ new eagerness to experiment with storytelling strategies.

Vision, danger, and the unreliable eyewitness

What does a thriller need in order to be thrilling? For one thing, central characters must be in mortal jeopardy. The protagonist is likely to be a target of impending violence. One variant is to build a plot around an attack on one victim, but to continue by centering on an investigator or witness to the first crime who becomes the new target. In Ministry of Fear, our hero brushes up against an espionage ring. While he pursues clues, the spies try to eliminate him.

Accordingly, the cinematic narration intensifies the situation of the character in peril. A tight restriction of knowledge to one character, as in Suspicion, builds curiosity and suspense as we wait for the unseen forces’ next move. Alternatively, a “moving-spotlight” narration can build the same qualities. In Notorious, we’re aware before Alicia is that Sebastian and his mother are poisoning her. Even “neutral” passages can mask story information through judiciously skipping over key events, as happens in the opening of Mildred Pierce.

Using point-of-view techniques to present the threats to the protagonist brought forth a distinctive 1940s cycle of eyewitness plots. Here the initial crime is seen, more or less, by a third party, and this act is displayed through optical POV devices. There typically follows a drama of doubt, as the eyewitness tries to convince people in authority that the crime has been committed. Part of the doubt arises from an interesting convention: the eyewitness is usually characterized as unreliable in some way. Sooner or later the perpetrator of the crime learns of the eyewitness and targets him or her for elimination. The cat-and-mouse game that ensues is usually resolved by the rescue of the witness.

The earliest 1940s plot of this type I’ve found isn’t a film, but rather Cornell Woolrich’s story “It Had to Be Murder,” published in Dime Detective in 1942. (It later became Hitchcock’s Rear Window. But see the codicil for earlier Woolrich examples.) The earliest film example from the period may be Universal’s Lady on a Train (1945), from an unpublished story by Leslie Charteris.

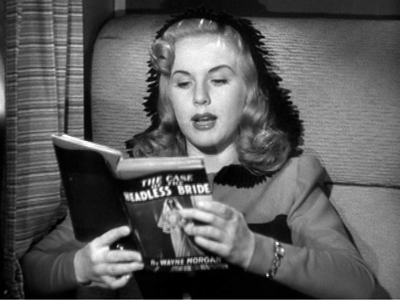

The opening signals that this will be a murder-she-said comedy. Nicki Collins is traveling from San Francisco to New York and reading aloud, in a state of tension, The Case of the Headless Bride (a dig at the Perry Mason series?). As the train pauses in its approach to Grand Central she comes to a climactic passage: “Somehow she forced her eyes to turn to the window. What horror she expected to see…” Nicki looks up from her book to see a quarrel in an apartment. One man lowers the curtain and bludgeons the other, and as Nicki reacts in surprise, the train moves on.

The over-the-shoulder framings don’t exactly mimic Nicki’s optical viewpoint, but they do attach us to her act of looking. Reverse-angle cuts show us her reactions. Her recital of the novel’s prose establishes her suggestibility and an overactive imagination. These qualities fulfill, in a screwball-comedy register, the convention of the witness’s potential unreliability. We know her perception is accurate, but her scatterbrained chatter justifies the skepticism of everybody she approaches. As the plot unrolls, her efforts to solve the mystery make her the killer’s new target.

More serious in tone was Lucille Fletcher’s radio drama, “The Thing in the Window” from 1946. In the same year, Cornell Woolrich rang a new change on the “Rear Window” theme with the short story “The Boy Who Cried Wolf,” and Twentieth Century–Fox released Shock. In this thriller an anxious wife waits in a hotel room for her husband, who has been away at war for years. Elaine Jordan’s instability is indicated by a dream in which she stumbles down a long corridor toward an enormous door that she struggles to open.

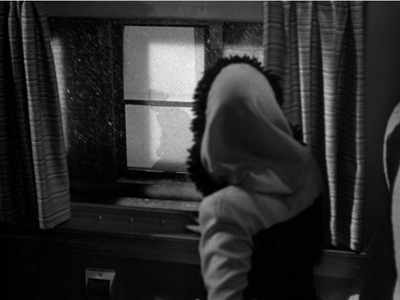

Awakening, Elaine nervously goes to the window in time to see a quarrel in an adjacent room. She watches as a man kills his wife.

Now she’s pushed over the edge. As bad luck would have it, the killer is a psychiatrist. When he learns that Elaine saw him, he takes charge of her case. He spirits her away to his private sanitarium, where he’ll keep her imprisoned with the help of his nurse-paramour.

I was surprised to learn of this eyewitness-thriller cycle because the prototype of this plot was for me, and maybe you too, was a later film, Rear Window (1954). Again, the protagonist believes he’s seen a crime, though here it’s the circumstances around it rather than the act itself. Accordingly a great deal of the plot is taken up with the drama of doubt, as the chairbound Jeff investigates as best he can. He spies on his neighbor and recruits the help of his girlfriend Lisa and his police detective pal.

Hitchcock, coming from the spatial-confinement dramas Rope and Dial M for Murder, followed the Woolrich story in making his protagonist unable to leave his apartment. Following Woolrich’s astonishingly abstract descriptions of the protagonist’s views, Hitchcock made optical POV the basis of Jeff”s inquiry. By turning Woolrich’s protagonist into a photojournalist, he enhanced the premise through use of Jeff’s telephoto lenses.

Woolrich and Hitchcock’s reliance on spatial confinement worked to the advantage of the unreliable-witness convention. How much could you really see from that window? Jeff can’t check on the background information his cop friend reports. Besides, Jeff is bored and susceptible to conclusion-jumping. “Right now I’d welcome trouble.”

Hitchcock, who kept an eye on his competitors, doubtless was aware of The Window (1949), an earlier entry in the cycle. Derived from Woolrich’s “Boy Who Cried Wolf,” this RKO film has some intriguing things to teach us about the mechanics of thrillers and about the 1940s look and feel.

Spoilers follow.

At the window, and outside it

On a hot summer night, the boy Tommy Woodry is sleeping on a tenement fire escape one floor above his family’s apartment. He awakes to see Mr. and Mrs. Kellerson murder a sailor they have robbbed. Next morning Tommy tries to report the crime to his parents and then the police, but no one will believe him because he’s long been telling fantastic tales. A family emergency leaves him alone in the apartment, and the Kellersons lure him out. After nearly being killed by them, he flees to a tumbledown building nearby. There he evades Mr. Kellerson, who falls to his death. With Tommy’s parents and the police now believing him, he’s rescued from his perch on a precarious rafter.

Woolrich’s original story confines us strictly to Tommy’s range of knowledge, but in the interest of suspense screenwriter Mel Dinelli uses moving-spotlight narration. When Tommy flees the fire escape, for instance, we follow the efforts of the Kellersons to rid themselves of the body. This becomes important to show how difficult it will be for Tommy to prove his story. There’s also a moment during their coverup when the camera lingers on Mrs. Kellerson, both in profile and from the back, as if she were hesitating about going along with the plan.

This shot prepares for the climax, when as her husband is about to shove Tommy off the fire escape, she blocks his gesture and allows Tommy to escape across the rooftops.

Likewise, Woolrich’s story simply reports that the young hero waited at the police station for the result of Detective Ross’s visit to the Kellersons. The film’s narration attaches us to Ross and creates a scene of considerable suspense when we wonder if Ross will discover any clues to the murder. And whereas in the story Tommy must worry about how Kellerson will get to him, through crosscutting between Kellerson in the kitchen and Tommy locked in his room we know everything that’s happening. This permits a wry passage of suspense in which Kellerson toys with Tommy by letting him think he’s retrieving the door’s key.

In contrast to the moving-spotlight approach, though, crucial passages are rendered with a limited range of knowledge. Optically subjective shots come to the fore here, as when Tommy witnesses the murder.

It seems likely that Hitchcock’s early American films heightened filmmakers’ awareness of subjective optical techniques, and here director Ted Tetzlaff puts them to good use. The script I’ve seen for The Window doesn’t indicate such pure POV shots, instead opting for something like what we get in Lady on a Train. “CAMERA is ON the pillow back of Tommy, so that we see his head in the f.g and the window in the b.g.” There is a shot matching these directions, but it’s surrounded by the straight POV imagery framed by Tommy’s frightened stare.

The decision by Tetzlaff and his colleagues to rely on optical POV is confirmed when, during Ross’s visit, he spots a stain on the floor.

Is this a bloodstain that will put Ross on the scent? Crucially, we haven’t seen the lethal scissors leave a trace. Kellerson explains the stain as coming from a leak in the ceiling. Obediently Ross looks up and, to prolong the suspense, so does Mrs. Kellerson, apparently as apprehensive as we are. That extra shot of her nicely delays the reveal: there is a leak above them.

In tune with the tendency to thicken the narrative texture, this POV dynamic reappears at other moments. Tommy sees his parents leave, and the reverse angle reveals that the Kellersons see them too, and so they know that Tommy is now unguarded.

At the climax in the abandoned tenement, Tommy spots his father and the policeman outside. He shouts to get their attention, but they can’t hear.

But Kellerman does hear Tommy and uses the sound to stalk him.

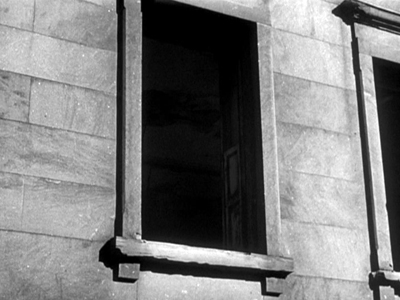

1940s stylistic thickening includes the use of audiovisual motifs that impose a distinctive look on the film. So a movie called The Window begins, after a couple of establishing shots of Manhattan street life, with a shot of a window.

This one has no special importance in the plot, but it announces the image that will recur throughout the movie. By shooting ordinary scenes through window frames, Tetzlaff reminds us that the locals live partly through those windows and the fire escapes outside.

Naturally enough, Kellerson plans to kill Tommy by having him tumble from the fire escape outside the window.

The film’s key image reappears at the end, when after Kellerson’s fall a new crop of witnesses take to their windows.

Another motif is the vertical link between the two apartments, given in looming shots of the staircase (a common piece of iconography in 1940s cinema) and in cutting that links Tommy’s bedroom to the Kellersons above him. He listens to their footsteps through his ceiling.

The next layer up, the rooftop, serves as a route from the families’ building to the abandoned one, and eventually the chase will play out there.

Vertical space more generally is important at the very start of the film. During Tommy’s mock ambush of his playmates, we look down over his shoulder. At the very end, Kellerson has trapped Tommy on the broken rafter.

The rooftop and rafter become part of another pattern, the circular one that rules the plot. Woolrich’s original story doesn’t feature the opening we have, showing Tommy in the abandoned tenement pretending to snipe at the other boys. Nor does the shooting script I’ve seen. Starting the film there establishes the locale of the climactic chase, while creating parallel scenes of Tommy hiding. We even get to see the broken rafter early on, when Tommy is prowling around his playmates.

The result is a pleasing, somewhat shocking symmetry of action: Tommy pretends to kill somebody at the start, and he succeeds in killing someone at the end.

The film offers a cluster of images that are recycled with variations, amplifying the basic story action through patterns of space and visual design.

The thickening of texture isn’t only pictorial. The drama of doubt involves a questioning of parental wisdom. Tommy’s mother actually endangers her boy by asking him to apologize to Mrs. Kellerson. More central is a testing of the father’s faith in his son. Tommy’s dilemma is to tell the truth even though he’ll be disbelieved by all the figures of social authority. The father’s increasingly desperate efforts to change Tommy’s story are revealed in Arthur Kennedy’s delicate portrayal of exasperation–at first gentle, then severe and nearly abusive.

Ed Woodry fails in his duty. The adults aren’t capable of protecting the child. A conventional plot would’ve had Ed redeem himself by rescuing his son, but the film we have leaves the killing to Tommy. It’s a grim condemnation of the people supposed to protect him.

Another convention, it seems, of the eyewitness film involves punishing the peeper. In Lady on a Train, Nicki has to brave a spooky house and risk death. Elaine of Shock suffers in the mental institution, and in Rear Window Jeff eventually falls from the very window that was his interface with the courtyard. Tommy, who acknowledges his inclination to tell whoppers, is subjected to a final burst of peril. After Kellerson has plunged to his death, Tommy is left in mid-air and he must jump to the firemen’s waiting net. In the epilogue, he announces that he’s learned his lesson, not least because of several brushes with death.

Revising the rules

The 1940s eyewitness cycle laid out some options for future thrillers. Rear Window, as we’ve seen, crystallizes the plot premise in rather pure form, and interestingly that was copied almost immediately in the Hong Kong film Rear Window (Hou chuang, 1955). Some passages are straight mimicry, albeit on a much smaller budget.

Thereafter, the eyewitness premise resurfaced, notably in Sisters (1973, with split screen) and with another child protagonist in The Client (1994).

In recent decades filmmakers have revised the premise in ways typical of post-Pulp-Fiction Hollywood. Vantage Point (2008) multiplies the eyewitnesses and uses replays to conceal and eventually reveal information. The Girl on the Train (2016), streamlining the multiple-viewpoint structure of the novel, alternates plotlines centered on three women. The novel and the film recast the eyewitness schema by making the eyewitness unable to recall exactly what she saw, thanks to an alcoholic blackout. (It’s a cousin to our old 1940s friend amnesia). This uncertainty raises the possibility that the eyewitness is actually the killer.

With its goal-directed protagonist and trim four-part plot structure, The Window is a completely classical film. As often happens, a forgivably flawed character gains our sympathy by being treated unfairly but triumphs in the end. And in the film’s integration of dramatic and pictorial elements, its alternation of subjectivity and wide-ranging narration for the sake of suspense, it nicely illustrates some ways in which 1940s filmmakers recast classical traditions for the thriller format and opened up new storytelling options.

Woolrich’s “The Boy Who Cried Wolf” is available under the title “Fire Escape” in Dead Man Blues (Lippincott, 1948), published under the pseudonym William Irish. Woolrich, ever the formalist, initially gave “It Had to Be Murder”/”Rear Window” my dream title: “Murder from a Fixed Viewpoint.” An earlier Woolrich story, “Wake Up with Death” from 1937, flips the viewpoint: A man emerges from drunken sleep to discover a murdered woman at his bedside and gets a call from someone who claims to have watched him commit the crime. Then there’s “Silhouette” from 1939, in which a couple witness a strangling projected on a window shade. See Francis M. Nevins, Jr.’s exhaustive Cornell Woolrich: First You Dream, Then You Die (Mysterious Press, 1988), 158, 186, 245. There are doubtless many earlier eyewitness thrillers, which the indefatigable Mike Grost could tabulate.

The screenplay by Mel Dinelli that I consulted, with help from Kristin, is a rather detailed shooting script dated 23 October 1947. It is housed in the Dore Schary collection at the Wisconsin Center for Film and Theater Research. Dinelli benefited from the thriller boom in his screenplays for The Spiral Staircase, The Reckless Moment, House by the River, Cause for Alarm!, and Beware, My Lovely.

There are plenty of discussions of thrillers on this site; try here and here. Apart from the chapter in Reinventing Hollywood, you can find overviews here and here. See also the category 1940s Hollywood. I discuss the sort of plot fragmentation characteristic of some current Hollywood cinema, built on 1940s premises, in The Way Hollywood Tells It.

For more images from my summer movie vacation, visit our Instagram page.

P.S. 24 July: Thanks very much to Bart Verbank for correcting my embarrassing name error in Rear Window! Also, if you’re wondering why I didn’t mention the very latest instantiation of the the eyewitness plot, A. J. Finn’s Woman in the Window, it’s because (a) I haven’t read it; and (b) I resist reading a book with a title swiped from a Fritz Lang movie.

DB accepts a fine Kriek from the Antwerp Summer Film College team: David Vanden Bossche, Tom Paulus, Lisa Colpaert, and Bart Versteirt.

Visual storytelling: Is that all?

Mission: Impossible (1996).

DB here:

The phrase “visual storytelling” is a very modern invention. It seems to be unknown before the mid-1940s, and it doesn’t really become common until the 1990s. It applies to film, of course, but it also refers to comic strips and other media. Sometimes it carries a prescriptive edge: In a pictorial medium, you should tell your stories visually—rather than, say, through lots of talk. The motto is sometimes summarized as Show, don’t tell.

Elsewhere on this site, I’ve argued that sometimes that advice should be ignored. A monologue about incidents in the past can sometimes be more powerful than a flashback depicting them. That power often owes something to the actors’ performances—which are, after all, no less visual than the story action being told us.

Similarly, who would attack great films like His Girl Friday for being too talky? An essential pleasure of American cinema from the 1930s on is the way that some scenes let dialogue take the lead. And it’s not just the words but how, and how fast, they are spoken.

Still, I do enjoy scenes that cut the gab and give us a flow of pictures that coax us to follow a story. My pantheon of great filmmakers includes Eisenstein, Keaton, Griffith, Lang, and many other silent masters. But mentioning them reminds me of something else that needs to be said.

Visual storytelling is seldom purely visual. In film, it needs concepts and music and noises and even dialogue to work most fully. We can learn a lot, I think, by starting with “purely visual” passages and see how they’re reinforced by other inputs.

Pictures, plus

Take the most vociferous defender of visual storytelling, Sir Alfred Hitchcock.

I want to put my film together on the screen, not simply to photograph something that has been put together already in the form of a long piece of stage acting. This is what gives an effect of life to a picture—the feeling that when you see it on the screen you are watching something that has been conceived and brought to birth directly in visual terms.

Yet Hitch needed words and music throughout his career. Put aside the talkathons that are Lifeboat, Rope, Under Capricorn, and Dial M for Murder. His silent films, including The Lodger and others, need written intertitles (dialogue-based, expository) to present the drama. The brilliant Albert Hall sequence in the first Man Who Knew Too Much (run here, analyzed here) would lose much of its power without the tight synchronization of shot-changes with the musical score. I yield to no one in my admiration for the climax of Notorious, which cuts rhythmically as the main characters gather in a knot and step slowly down a staircase. But the progress of the drama needs the snatches of dialogue no less than the close-up glances and POV shots, and they get integrated into the implacable beat of descent.

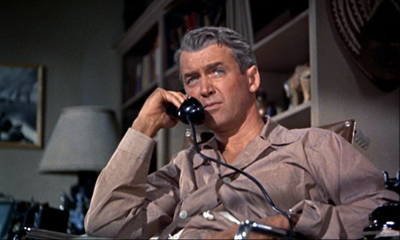

Then there’s Rear Window, which has a fascinating double opening. The first uses imagery, music, and sound effects to present the situation of Jeff laid up in his apartment over the courtyard. After a tour of the neighbors’ flats, seen from a distance, we’re shown why Jeff is lying there in a sweat.

But during the next scene Jeff gets on the phone with his editor. Now much of the information we got visually is reiterated in dialogue.

Jeff’s optical POV cuts during the phone conversation also recapitulate the neighbors’ routines that we’ve seen in the first sequence. By the end of this second scene, image and sound have explained his situation wholly, thanks to a division of labor. The first, wordless sequence is a kind of test for the viewer, and the second serves as the answer key.

Which brings me to Brian De Palma, Hitch’s self-conscious heir. Of the 1970s generation, he was the most explicit in defending the purity of the pictures in motion pictures.

1973: I always have very precise visual ideas and then try to construct a story around them as opposed to writing a story and then trying to figure out how I’m going to shoot it. . . . As far as I’m concerned, you are dealing with pure cinema—that is, with what is right on the screen—and you should try to think what it will look like.

1984: Images run through my brain all the time. Lately I’ve been thinking about rearview mirrors. You can see people in the next car out your rearview mirror. They’re always doing the most personal things—putting on makeup, fighting, kissing, whatever. I want to put that in a movie. Someone could see a murder in their rearview mirror.

1992: Do you really want to go to work every day and shoot two-shots of people talking to each other? Is that directing?

2002: I’ve been obsessed with this kind of visual storytelling for quite a while, and I try to create material that allows me to explore it. I did quite a lot of it in Femme Fatale. And it put me on a course of, “How can I find visual ideas and work them into the stories I want to tell?” That’s something that haunts me all the time.

Hence the famous De Palma set pieces. Usually scenes of violence, they’re handled through elaborate crosscutting, optical POV, steep high and low angles, slow-motion, bravura camera moves, and extreme deep focus (often with a split-focus diopter). We think of the murders in Sisters and Dressed to Kill, the stalking of Nancy Allen in Blow Out, the baby carriage in Union Station in The Untouchables, and the outrageous Cannes festival opening of Femme Fatale.

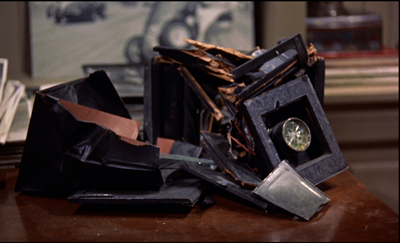

Then there’s the invasion of CIA headquarters by Ethan Hunt’s scratch team in Mission: Impossible (1996). In the director’s search for pure cinema, this might be the purest of all.

From here on in

The invasion sequence runs an astonishing eighteen minutes and, as typical of a film’s Development section, constitutes almost pure delay. You can imagine doing it in a couple of minutes, or a lot more.

The main portion of the sequence crosscuts several lines of action. The hacker Luther crouches over his monitor in the firetruck, tracking the parties in the building. Inside Claire tags and dopes the analyst Donloe. From the air duct the venal Krieger suspends Ethan on a rope as he drops down into the black vault (which is white). Ethan must dangle above the computer keyboard extracting the NOC list of agents. We also get occasional glimpses of Kittridge, Ethan’s nemesis, in a central control room.

These lines of action are conveyed through several striking visual ideas. We get the geometry of De Palma’s beloved bird’s-eye camera positions.

There’s extreme depth, jamming two dramatic elements into sharp relationships: Ethan and Donloe, Krieger and the rat approaching him from behind.

Even the rather perfunctory tag, the firing of poor Donloe (“Mail him his clothes”), is rendered in a flashy split-focus shot.

Compared to what we expect from a blockbuster, this sequence depends to a remarkable degree on a quiet flow of visual information. David Koepp, one of the screenwriters, explains De Palma’s plan:

He had another great idea, which was a reaction to the current state of summer movies at the time. He was tired of all the noise, of the bigger bigger bigger noisier noisier noisier setpieces, and desperately wanted to come up with one that used silence instead. He cackled at the idea of a big summer movie set piece that was predicated on silence.

The result is nice case study in visual storytelling. It also indicates how even a pure instance needs non-visual elements to be understood.

Top among those elements is genre. We know a heist situation when we see one, and that knowledge forms a kind of hollow form, a schema into which we slot the elements that generate suspense. What elements? There’s the need for silence and concealment. There’s Donloe, the oblivious analyst who comes in and out of the vault; he must be distracted, but he may still return at the wrong moment. There are unexpected obstacles—a suspicious guard, a curious rat, and a drop of sweat. There’s the risk of a telltale detail that may betray the invaders, such as Krieger’s dagger, dropped onto an arm rest. Over it all hovers a deadline, so that the heist becomes a race against time. (Not only is there a clock in the room, but a digital readout warns us of the rising temperature in the room, another potential giveaway.) Visual storytelling is enormously helped when we bring so much prior knowledge about the type of situation we confront.

“From here on in,” Ethan warns the team, “absolute silence.” For them, maybe, but not for us. The music continues a bit before subsiding for about ten minutes. Even then, the silence isn’t absolute. We hear the hum of the vault, the scratchy patter of the rat approaching Krieger in the ductwork, and the squeaking of the rope as Krieger pays it out and strains to keep Ethan poised above the floor.

Clearly, in his concern for visual storytelling De Palma isn’t ruling out noise and music. What he’s opposed to is talk. But there is talk, however discreet, here too. In M:I, I count about two dozen lines of dialogue once Krieger and Ethan get positioned above the vault. These chiefly involve Luther whispering information to Ethan about Donloe’s whereabouts. Granted, many of his lines are very terse (“He’s in the bathroom,” “Check,” “Good”). Still, dialogue serves as a good redundancy factor, accentuating the suspense of the situation and at one moment giving us access to Luther’s reaction, when he discovers that what Ethan has nabbed is the precious NOC list.

Just as important, our experience of the full suspense of the scene depends on talk we’ve heard earlier. Ethan has gathered his team on the train and is explaining how the security system at Langley works. Using a strategy that goes back to Lang’s M, M:I presents Ethan’s verbal walk-through of the procedures as a voice-over for footage of Donloe executing them. The sequence introduces us to Donloe, familiarizes us with the constraints of the heist, and maps out the normal going-and-coming rhythm that Donloe’s spasmodic upchucking will disrupt.

So the vault break-in can rely on relative silence partly because the situation has been given fully by Ethan’s verbiage. In a way, it’s the reverse order of the Rear Window tutorial: dialogue first, then images to give it dramatic impact.

Drop by drop

Let me close today’s entry with a less obvious but still nifty passage of (audio-) visual storytelling. It comes at the start of Mission: Impossible.

Instead of the usual and wasteful extreme long shots of the city we’re in, taken from a distance or coasting high above the streets, we start immediately, in the closet where Jack Harmon is bent over a monitor. Already we have two things to watch: the sting operation captured by a hidden camera, and the reactions of Jack as he watches.

Correction: Three things to watch. There’s also the owner of the feminine arm on the frame edge of the opening setup. The camera’s track-in eliminates it, but the reverse angle on Jack reminds us that some woman is there, in the right background and out of focus. The script calls her a “whorehouse waitress,” but that’s not apparent from what we see in the film.

Cutting back and forth between Jack and the monitor not only gives us his reaction, but reminds us of the woman, who changes position in the shots.

Once the official Kasimov has given the name Ethan needs, the team’s goal is achieved and Jack can search it on his computer. In the meantime, Kasimov needs to be dragged off without fuss, and so must be given a drugged drink. That, we now understand, is the task of the woman hovering in the background of Jack’s shots. We’ve also been primed by the tray with bottle and glasses in the first shot.

One option would be to pan or cut to the woman behind Jack and show her doping the drink. (This is what the shooting script seems to call for.) We might even see the woman’s face as she does it, but even if we don’t, a shot emphasizing her would give us a lot of other inessential information about the room.

De Palma makes another choice. This woman is important only in terms of what she does. Panning to her, or supplying a separate shot, and showing her face might make her seem as important a character as Jack, Ethan, or Claire. She’s not. So De Palma reduces her to her function: doping the drink. And for economy, she does it in the same setup previously devoted to Jack’s reaction. She’s kept in the background.

But the problem now is making sure the audience sees the gesture. De Palma could presumably have given us one of his split-focus shots, but here he does something more daring. The woman’s hand is above the upper frame edge, so all we see is the eyedropper in action. As it squeezes dope into the glass, all sound except Jack’s typing is cut from the track. We hear the drops very loudly, in what Jean Epstein called a “sonic close-up.” The precision of the sound compensates for the fact that the gesture is out of focus.

The bit ends when she slips out of the room in the background….

…and enters the scene shown on the monitor to serve the drink.

This is a tidy piece of classic continuity. If we don’t understand what’s happening, it’s not De Palma’s fault. Now that we see the serving woman more clearly, as one among several functionaries, there’s no reason for us to think she’ll be important in the action to come. By contrast, as Ethan revives Claire, we get tight reverse shots of them—not only underscoring their importance but setting up the quasi-affair that will be important in the plot ahead.

As often happens, the scene conforms to an action schema we have about crime and spy skullduggery: drugging your adversary’s drink. Here the schema is actualized in a way we don’t normally see, but the essential cues are present. And even this gesture has a larger purpose. We can expect the M:I team to drug somebody else, as indeed they will in the Langley exploit. Then we can get a proper close-up to understand that Claire’s task is accomplished. And of course drops will become pretty important when Ethan is dangling just above the vault floor.

I wish I had time to consider other examples of visual storytelling in Mission: Impossible. There’s the credits sequence, for instance. In reviving the TV series’ original glimpses of the episode to come, the sequence yields something that is very rare in feature film: anticipations of particular things we’ll see. TV network programming gave us bumpers that offered teasing previews of high points in the next show up. Did M:I, like I Spy, swallow up such “flashforwards” into its credit sequences? And how much did these TV credits owe to the anticipatory images in the credits of Goldfinger?

Above all, I’d like to spare time for the very clever flashbacks that, at the climax, show us how the initial murder of the team actually went. I call them clever because it’s not at that moment certain whether they are flashbacks constructed solely for us, to tip us off to the betrayal, or whether they also represent Ethan’s new understanding of that early bloodbath. But of course those quick flashbacks depend on nonvisual information as well, especially the voice-over that accompanies them.

Still, I hope I’ve said enough to suggest that “visual storytelling” in film needs both sound and more impalpable factors—context, familiar situations, genre conventions—to work. And those factors in turn depend on our knowledge of conceptual structures (schemas) that the film prompts us to lock in. As usual, narrative movies provide the audience an instruction kit, coaxing us to apply our knowledge to a fresh instance. In other words, the eye is part of the brain.

Many thanks to David Koepp for information about the production of Mission: Impossible. For some of David’s ideas about visual storytelling go here. The shooting script is available online here. Watch for David’s next directorial effort, the 60s-style intrigue comedy Mortdecai, coming 23 January!

My Hitchcock quotation comes from his 1937 essay, “Direction.” The version of that piece I’ve used is in Hitchcock on Hitchcock, ed. Sidney Gottlieb (University of California Press, 1995), 256. The De Palma quotations are all from Brian De Palma Interviews, ed. Laurence F. Knapp (University Press of Mississippi, 2003), 12, 84, 131, 177.

Why do Development sections tend to include delays? See Kristin’s blog entry here and her Storytelling in the New Hollywood. I discuss her layout of plot parts in another Mission: Impossible installment in “Anatomy of the Action Picture.” On the imagery of Dial M for Murder, there’s this blog entry.

Mission: Impossible.