Archive for July 2007

Summer camp for cinephiles

Bruges, Belgium is a tourist haven. This reconstructed medieval city boasts museums, canals, cafes, an impressive town square, and other attractions guaranteed to keep credit cards flowing through. It’s a wonderful place to stroll in the sunshine, shop, or watch windmills slowly spin.

In alternating summers, though, Bruges plays host to people who prefer to sit in the dark. This strange cult includes professors, students, and cinephiles from all walks of life. For a small fee Belgians and Netherlanders can plunge into eight intensive days of viewing, lectures, and discussions. While tourists shuttle by unsuspecting, the devout are gathered to watch such items as Rebel without a Cause, the entire Niebelungen, and Destroy All Monsters.

It’s the Zomerfilmcollege, funded by the Flemish side of the Belgian government and run by the Flemish Service for Film Culture in partnership with the Royal Film Archive. In English we’d call it Film Summer Camp. There are no papers or grades. It’s a college in the original sense, a gathering of minds for purposes of deepening knowledge and expanding ideas.

It’s held in the Lumière cinema, a central three-screen moviehouse specializing in arthouse fare (and, for part of our stay, The Simpsons Movie). On the ground floor is a cozy bar, which also serves the lunches and dinners for the collegians. The whole building, like the atmosphere of the event, is unpretentious and welcoming.

Typically there are two principal courses and a sidebar. This year, one course was on Fritz Lang, the other was on widescreen film, and the sidebar was devoted to the French cinematographer Henri Alékan (La Belle et la Bête, Wings of Desire). The schedule is fairly full. At 9:00 AM there’s a lecture, followed by a film screening, then lunch. After lunch, another lecture and another screening. Dinner follows at about 6:30, and evening events follow, with a film or special presentation at 8:00 and then at least one more film afterward. All films are in 35mm prints.

A real workout

Kristin and I had been lecturers here several times, but this year I came alone. The Lang cycle was to have been handled by Tom Paulus, who gave us Hawks last time, but illness kept him away. He was replaced by several other fine Flemish scholars: Hilde D’haeyere, Steven Jacobs, and Roel Vande Winkel. They supplied lectures on Lang and architecture, on his relationship to the German “street film,” on his relation to the Nazi regime, and on his American work. The retrospective gave a good sampling, running from the Dr. Mabuse films (1922) to Moonfleet (1955; very nice print). For Alékan, there was the filmmaker/ archivist/ novelist Eric DeKuyper, for whom Alékan shot A Strange Love Affair (1984), and the Belgian professor Muriel Andrin, who incisively introduced us to visual influences on Alékan’s aesthetic.

Most lectures are in Dutch, but fortunately for me some are conducted in English. In previous years I’ve lectured on modern Asian film, Hollywood in the 1970s, and the history of film staging. This year my topic was anamorphic widescreen. The talks grew out of my research for an essay to appear this fall in my collection Poetics of Cinema.

The week is now about three-quarters done, and I’ve had a great time. Using clips and slides, I started with a block tracing CinemaScope in the US, with my main examples being Rebel, River of No Return, Moonfleet (intersecting with Lang), The Girl Can’t Help It, and Compulsion. Tonight we’ll get our example of modern usage of the widescreen with a showing of Three Kings.

The next three sessions concentrate on non-US usage of the anamorphic format. Le mépris screened today and will be discussed tomorrow. Oshima’s The Catch will represent a Japanese approach. On Sunday, we end with Johnnie To Kei-fun’s The Mission as illustrating one Hong Kong approach. By nice synergy, To’s Election and Election 2 are playing on other Lumière screens, so collegians can sneak off for some extracurricular viewing.

I enjoy visiting the college, and not just because I like to lecture. A schedule of screenings negotiated by what’s available in a good print from the archive or a distributor forces me to confront films I haven’t studied before. Even for those I know pretty well, seeing them big and beautiful can stimulate new musings. And as any teacher will tell you, even going back over familiar material shows you something fresh.

No lack of scope

For example, I had always loved the way Nicholas Ray used deep space to link his young protagonists in the police station at the start of Rebel. But this time I noticed how Dean’s performance was fitted to the wide frame: He begins the movie prone and pretty much ends there.

I also noticed how Jim’s gesture of covering the toy monkey at the start is echoed by his and Judy’s protective covering of Plato, and by the climax when Jim’s father covers him.

Viewers more familiar with Rebel than me have probably noticed these rhyming gestures and attitudes, but finding them on my own, innocently if you like, fueled my interest in teaching a film I had never studied closely.

Likewise, I wasn’t aware that the glasses motif in Compulsion is linked to imagery of blinding light, a kind of supernatural authority that not only points to the guilty party but also leads the monstrous, pathetic Judd to mercy. The dynamic is given diagrammatically in the closing and opening credits.

My previous post was about watching movies small and super-slow; now I’m reaping the advantage of watching films big and normally. Today, watching Godard’s Contempt on the screen I was able to enjoy those motifs of color, light, and composition that move almost musically through every Godard film (See top of entry.) I was able to identify some more citations (the novel adorning BB’s fanny is John Godey’s noir Frapper sans entrer) and feel the full force of the bold geometry of the framings. I hadn’t noticed before that the first image of the table lamp in the apartment sequence prepares, inversely, for the villa steps in Capri.

And I’d never noticed before how the last time Paul sees Camille, at the rocky outcropping that overlooks the seascape, she becomes that nymph seen in Lang’s rushes and identified as Penelope of the Odyssey.

Perhaps Camille is Penelope for Paul, but not necessarily for us. One task of the film is surely to make us suspicious of neat parallels between contemporary and classical culture; what Godard gives us graphically he often qualifies or negates elsewhere in the film. (1)

I expect to have some further fun with The Catch and The Mission, both of which will look splendid on the Lumière screen.

I turned sixty on the day I showed Rebel. Being here, though, I don’t feel so old. I have to keep up with the collegians and the dedicated archive team–Stef, Tim, Vico, Esther, and Joost. Their energy turns a medieval city into an exuberant adventure in cinema.

(1) After preparing my lecture, I discovered a wonderful website on citations in Godard, with special focus on Le mépris.

The Zommerfilmcollege gang, in 2.35 Scope. Photo by Esther Dijkstra.

Watching movies very, very slowly

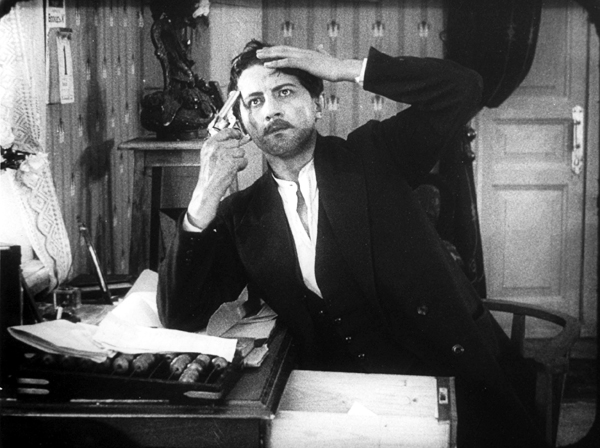

Children of the Age (1915).

DB here:

Before DVD and consumer videotape, how could you study films closely? If you had money, you could buy 8mm or 16mm prints of the few titles available in those formats. If you belonged to a library or ran a film club, you could book 16mm prints and screen them over and over. Or you could ask to view the films at a film archive.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

I started going to film archives in the late 1960s, when they were generally more concerned with preserving and showing films than with letting researchers have access. Over the 1970s and 1980s this situation changed, partly because several archivists grew hospitable to the growing field of academic film studies.

At first archives found it easier to screen films for researchers in projection rooms, but eventually many let visitors watch the films on stand-alone viewers. That way the researcher could stop, go forward and back, and take notes. In researching my dissertation in the summer of 1973, I watched films at George Eastman House in 16mm projection, but a few weeks later in Paris, Henri Langlois of the Cinémathèque Francaise allowed me time on Marie Epstein’s visionneuse (a term I’ve admired ever since).

Over the years Kristin and I have visited archives in various countries. We’ve become particularly close to the Royal Film Archive of Brussels, partly because back in the 1980s the head, Jacques Ledoux, believed that Kristin’s research was worthwhile and allowed us to visit regularly. Without the cooperation of Ledoux and his successor Gabrielle Claes, we couldn’t have done a great deal of our research. No wonder it helped us so much: the Belgian Cinémathèque is arguably the most diverse archive in the world.

Case in point: My current visit. I came with two goals. First, I had to prepare for my lectures in Bruges later in the month. These consist of eight talks on anamorphic widescreen. So I planned to watch four early CinemaScope films, plus Oshima’s The Catch (1961) and the SuperScope version of While the City Sleeps.

I also wanted to fill in a big gap in my knowledge about a major silent filmmaker. More on him shortly.

Viewing on a visionneuse

If you’ve never watched a film on a viewer, let me explain. The classic viewer is a flatbed, or viewing table. It’s the size of an executive desk. Two platters or spindles hold a feed reel and a take-up reel. Motors drive the film through a series of sprocketed gates, past a projection device (usually a prism) and across a sound head. The film appears on a smallish screen. There’s usually a little surface space to set a notepad, along with a lamp on an articulated arm.

Before digital editing came along, such machines offered the only way filmmakers could cut sound and picture. (Now most phases of editing are done on computer, with physical editing reserved for late stages of postproduction.) Eventually flatbeds were offered in simpler versions for playback rather than editing.

The most common American-made viewer was the Moviola, which was initially not a flatbed but an upright machine. Eventually the German Steenbeck and KEM became the high-end standards for editing picture and sound. The Brussels archive relies on the Prévost, an Italian machine that is very easy to maintain. The Prévost, seen above, beams the image from the prism onto a mirror hanging over the machine, which bounces the picture onto the screen.

35mm films are mounted on 1000- or 2000-foot reels, the latter yielding about twenty minutes of film at sound speed. A feature film will consist of four or more 2000-foot reels. Even if you watch a film straight through, without stopping to make notes, it takes time to change the reels, so a two-hour movie will probably consume nearly three hours on a 35mm flatbed. And of course researchers stop a lot to take notes and move to and fro across a scene. If I’m studying a film intensively, I probably consume about an hour per 2000-foot reel. Across my life, I wouldn’t dare calculate how many months I’ve spent in visionneuse viewing.

Viewing on an individual viewer has both costs and benefits. Sometimes details you’d notice on the big screen are hard to spot on a flatbed. But with your nose fairly close to the film, you can make discoveries you might miss in projection. (Ideally, you would see the film you’re studying on both the big screen and the small one.) In addition, of course, you can stop, go back, and replay stretches. Above all, you get to touch the film. This is a wonderful experience, handling 35mm film. Hold it up to the light and you see the pictures. You can’t do that with videotape or DVD.

The scary part of any flatbed viewing, at least for me, is watching the film whiz along under your nose at ninety feet per minute. If you haven’t threaded the thing properly, or if the print has a weak splice or torn sprocket hole, you can rip the film. For this reason, archives typically don’t allow a researcher to handle films they hold in only one copy.

The average film you watch on a flatbed has an optical soundtrack, that squiggly line that is read by an optical valve. But early CinemaScope films had magnetic tracks so that they could provide stereophonic sound. In the picture below you can see that strips of magnetic tape, like those in tape cassette players, run along both edges of the film strip. For my Scope films, I was obliged to use a Prévost that could handle mag sound–and of course one that could be fitted with an anamorphic lens to unsqueeze the image to the proper proportions.

Hell on Frisco Bay (1954) was a color movie, but this print, like many from the period, has faded to bright pink. The Eastman color stock of the period was unstable, and many prints were processed carelessly. (In unsqueezing the frame, I’ve eliminated the color cast for better clarity.) Restoring color to films of this period is one of the major tasks facing film archivists. Cinema is a fragile art form.

Hours and hours of Bauers and Bauers

At the Giornate del Cinema Muto in Pordenone in 1989, Yuri Tsivian’s retrospective on Russian Tsarist cinema convinced a lot of us that good filmmaking in that country didn’t start with the Bolshevik revolution. Along with that retrospective came a wonderful book, Silent Witnesses, edited by Yuri and Paolo Cherchi Usai. Unfortunately hard to find now, it’s filled with information about pre-Soviet filmmaking.

Although I enjoyed the Tsarist films, I didn’t know exactly what to watch for. It took me some years to appreciate their artistry, and some of my ideas about them showed up in On the History of Film Style (1997) and Figures Traced in Light (2005). In those places I studied 1910s “tableau” staging and used some examples from Yevgenii Bauer, by common consent the most pictorially ambitious Russian director of the period. Kristin and I also used Bauer as an example of tightly choreographed mise-en-scene in Film Art (p. 143). I thought it was time I examined his work more systematically, and I knew that the Royal Film Archive held some Bauer prints, which they acquired from Gosfilmofond of Moscow.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Bauer had a brief but prolific career. He started directing in 1912 and completed eighty-two films before his death in 1917. Unhappily, only twenty-six of his works survive. Just as bad, most of those lack their original intertitles, so we don’t have the expository and dialogue titles we expect in silent films. The placement of the titles is sometimes signaled by two Xs marked on two successive frames. Without titles, the storylines can get obscure. Yuri, Ben Brewster, and other scholars have sought to reconstruct something approximating the original titles by studying the plays and novels that Bauer adapted. Three of the reconstructed films are available on a DVD called Mad Love, and Yuri has also created an innovative CD-ROM (right) that takes us through works of Bauer and his contemporaries.

Although he made comedies, Bauer is most famous for his somber psychological melodramas, often centering on class exploitation. A woman becomes a rich man’s mistress; when she abandons her husband and takes their baby, he commits suicide (Children of the Age). A serving maid is seduced by her master and callously tossed aside when he marries a flirt (Silent Witnesses). Things can get pretty dark. This is the director who made films entitled After Death (1915) and Happiness of Eternal Night (1915). In Daydreams (1915), a widower sees a woman who strikingly resembles his dead wife. Like Scottie in Vertigo, he follows her and becomes increasingly obsessed. Did I mention that he keeps a ropy braid of his dead wife’s hair in a glass box?

Seeing several films again confirmed my view that Bauer knew better than most directors how to organize a shot. His contemporary Louis Feuillade favored a quiet, sober virtuosity, but Bauer developed a flashy visual style. He’s most known for his ambitious use of light (Frigid Souls, below) and big, textured sets packed with columns, trellises, drapes, brocades, embroidered pillowcases, and other elements that add abstract patterns to a scene (Children of the Age, below).

Even a hammock can be stretched and framed to create a swooping web around the innocent heroine of Children of the Age, ensnared by the demimondaine.

In particular, I admire Bauer’s constant inventiveness in moving his actors around the set in smooth ways that always direct our attention to what’s happening at the right moment. European directors of this period seldom cut up a scene into several shots of individual actors; the frame typically shows us the entire playing space. Directors were obliged to shift their actors across the frame and arrange them in depth, like chesspieces.

This master-shot, single setup approach might seem hoplelessly restrictive. Today we expect films to have lots of cutting and camera movement. How does the filmmaker sculpt the action, moment by moment within a static frame?

Blocking, as in blocking the view

I trace some principles of this approach in the books I already mentioned. I’ll mention two strategies here, and if you want to know more you can follow up in On the History of Film Style and Figures Traced in Light.

Filmmakers of the 1910s created intricate choreography by moving actors left or right, up to or away from the camera. Often they set up unbalanced compositions and then rebalanced them, creating a kind of spatial tension that parallels the drama. In the course of the action, actors close to the camera might conceal those that are farther away. The blocking of the actors, in other words, also sometimes blocks our view.

In Leon Drey (1915), Bauer tells the story of a cynical womanizer. In one scene, he’s dallying with his latest conquest when another of his lovers bursts into his apartment. The first phase of the shot is very unbalanced; most directors would have put the mistress at the door on one side of the frame and Leon and the woman in his arms at the opposite side. Immediately, though, the woman flees to the bed in the back of the shot and activates the right area of the frame.

As the mistress rushes to the woman in the rear, Leon strides to the foreground and his burly body blots out the drama between the two women. We’re forced to concentrate on his cold indifference to both of his lovers. Eventually his mistress comes to the foreground to remonstrate with him. Now, at the high point of the scene, we have a balanced frame. Note that Leon continues to conceal the first woman; the scene’s not yet about her.

The mistress leaves, angry and desperate, and Leon placidly pays her no mind. As the door closes, he hurries to lock it and summons the first woman, now visible, back from his bed. He will have little trouble convincing her to return to his arms.

The dramatic curve of the scene has been expressed in compositional asymmetry and symmetry, concealing space and then opening it up.

Most directors of the period used principles like these to turn dramatic conflict into vivid choreography. Bauer also tried more unusual tactics. He was especially good at shifting actors’ heads very slightly to open or close off channels of action behind them. Here’s an instance from Her Heroic Feat (1914).

The butler informs Lina and her mother that the scandalous ballerina Klorinda is calling on them. At first Lina’s head is solidly blocking the doorway in the rear. As the butler goes to the rear door, Lina pivots a little to clear our view of that doorway.

Klorinda sashays in, and who could miss it? She’s wearing a bright dress, she’s centrally positioned, and she’s moving toward us. The other women refuse to look at her, but their immobility assures that we keep our eye on Klorinda. When she stops to greet them, then they move, pivoting away; Lina’s head goes back to blocking the doorway. Imagine how things would have gone if her head had been there when Klorinda appeared in the background.

Of course, we should also study the performance techniques of Bauer’s actors–a subject examined in a fine book by Ben Brewster and Lea Jacobs, Theatre to Cinema. The compositional tactics employed here work to draw our attention to the actors’ expressions and body language.

Still, not everything in 1910s ensemble staging owes a debt to the theatre. The changes in Lina’s head position, or Leon Brey’s calculated blockage of the women behind him, wouldn’t work on the stage; most of the audience wouldn’t see the exact alignment we get onscreen. Live theatre depends on varying sightlines, but in cinema, we all see the action from one position, that of the camera. Bauer, Feuillade, and their contemporaries realized that they could organize the action, down to the smallest detail, around what the camera could and could not take in.

The fluent choreography developed by 1910s directors is almost unnoticeable when you’re watching in real time. You’re supposed to register the what–the point of interest in the frame–rather than the how, the slight shifting of actors that highlights this face, then that gesture. By the time you realize that something has happened, the first stages of the process have slipped away, inaccessible to memory.

So there’s a need for slow viewing. Filmmakers have thousands of secrets, many that they don’t know they know. Sometimes we have to stop the movie, go back, and trace precisely how directors achieve their effects. Really slow viewing can help us discover how deep film artistry can be. All hail the visionneuse and the archives that allow scholars to use her.

For background on Bauer, see William M. Drew’s excellent career survey. I discuss Bauer’s relation to narrative painting in another blog entry.

In production and distribution of the period, the titles and inserts (close-ups of newspapers or messages) were sometimes stored on separate reels. In many cases, only the image reels have survived.

Several other Bauer films are available on Milestone’s invaluable DVD set Early Russian Cinema.

Cautious, that’s c-a-u-t-i-o-u-s optimism concerning The Hobbit

Image from: www.filmski.net/vijesti/dugometrazni-film/4253

Kristin here—

On June 10 I posted my most recent entry on the situation with the Hobbit film, editorializing a bit on the dispute between New Line Cinema and Peter Jackson. That received a gratifying amount of attention from fans, so here’s a little update.

To the general public, it would appear that not much has happened since then. There are signs of progress, however, glacial though it be.

In an interview with the New York Post on July 10 (timed to publicize the release of his second directorial effort, The Last Mimzy, on DVD), New Line’s co-president Bob Shaye discussed the situation:

“And, speaking of fantasies, Shaye hints we should never say never at the idea of Jackson, whom he labeled ‘arrogant’ last year, directing ‘The Hobbit’ someday.

‘There’s nothing I can really talk about except to say that I believe ‘The Hobbit’ will be made,’ says Shaye, choosing his words carefully like the lawyer that he is. ‘There’s a bunch of issues and elements that have to be addressed.

‘I don’t like to have issues with anybody. Any issues with Mr. Jackson, I would prefer to have them closed rather than open.’”

This statement doesn’t go much further, if at all, than what Shaye and co-president Michael Lynne said at Cannes Film Festival in May, quoted in my June 10 entry.

Now, however, there comes a statement from Ian McKellen that suggests that progress is being made. In Singapore as part of his extensive tour playing in King Lear and The Seagull, McKellen said on July 19:

“I detect that there is some movement and it’s movement in the right direction. I’ll be seeing Peter when we tour [New Zealand] next month. I hope it will happen.”

I think this is probably the most optimistic public statement by a person who is in a position to have some behind-the-scenes knowledge. It also matches some vaguer rumors I had heard myself.

The decision makers at New Line may not be aware of just how much sentiment there is among fans to have this film directed by Peter Jackson. The three and a half years since the release of the third part of the trilogy haven’t dimmed the enthusiasm. Bob Shaye could gain vast credit with these people by reconciling with Jackson and inviting him to direct The Hobbit. And a lot of these people are the same core constituency that would be interested in The Golden Compass.

[For earlier posts on the Hobbit project, see here, here, and here.]

Fantasy franchises or franchise fantasies?

Kristin here–

While David is watching films in Brussels, I’m back in Madison, overseeing some house renovations, moving into the publicity phase of The Frodo Franchise in anticipation of its release, and generally enjoying a chance to catch up on my reading.

I’ve also finally tackled one of those “someday we really must …” projects. Not surprisingly, a considerable portion of our home is given over to storing books, journals, file folders, DVDs, videotapes, laserdiscs, negatives, and slides. For all too long a heap of old magazines has been sitting on the floor in the aisle between two of our bookshelves, on the assumption that someday we really must triage these and file the clippings in subject folders where we might actually have a chance of finding them.

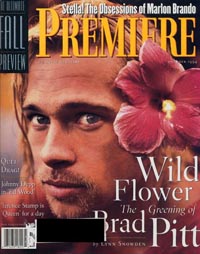

Most of these magazines are old issues of Premiere, mainly from the 1990s. Premiere ceased publication as of April, and I can’t say that I miss it greatly. It had slid distinctly by then, but back in the nineties it was actually pretty good. (J. Hoberman was writing regularly for it!) Every issue I’ve examined so far has at least one item worth saving, and sometimes two or three.

These issues aren’t in chronological order, so the first stack I scooped up to look through was a random batch, with the October 1994 issue on top. It featured a  big close-up of Brad Pitt on its cover. He was just on the brink of becoming a star, being best known to that point for his supporting roles in Thelma and Louise and A River Runs Through It. He had just finished Interview with the Vampire.

big close-up of Brad Pitt on its cover. He was just on the brink of becoming a star, being best known to that point for his supporting roles in Thelma and Louise and A River Runs Through It. He had just finished Interview with the Vampire.

What interested me more was an ad that greeted me as I flipped the first few pages: the famous fake-worn-dust-jacket ad for Pulp Fiction. Odd that I had happened to begin with an issue from the season when one of the most influential films of the past two decades was being touted in preparation for its October release.

Indeed, the April issue happened to contain Premiere’s “Ultimate Fall Preview.” Naturally I got sucked into checking out what other films had been released that season. Given all the complaints these days about franchise films dominating Hollywood and pushing out the worthwhile films, I wondered just how good the good old days were.

To get a sense of what was going on in 1994, let’s start with the 10 top-grossing films of the year. Based on Box Office Mojo’s list of domestic grosses (in unadjusted dollars), they are: Forrest Gump, The Lion King, True Lies, The Santa Clause, The Flintstones, Dumb and Dumber, Clear and Present Danger, Speed, The Mask, and Pulp Fiction.

From our current perspective, the lack of franchise films on this list is striking. Only Clear and Present Danger, the second film starring Harrison Ford as Jack Ryan, belongs to part of an exiting series. The only film in a long-established franchise that came near the top was Star Trek: Generations at #15. Other sequels appear further down the top 50: The Naked Gun 33 1/3: The Final Insult (#23), City Slickers II: The Legend of Curly’s Gold (#32), Beverly Hills Cop III (#34), and Major League II (#45). No wonder sequels got a bad reputation!

On the other hand, several films in the top 10 spawned sequels: The Santa Clause, Dumb and Dumber, Speed, and The Mask. (Dumb and Dumber and The Mask both had their sequels considerably delayed by New Line Cinema’s inability to meet Jim Carrey’s skyrocketing salary demands and his resultant departure from the studio.)

In 1994, Hollywood was still in the early days of the franchise trend. After Batman in 1989, its sequel, Batman Returns, had come out in 1992, but that wasn’t enough to establish a pattern. Jurassic Park had appeared the year before but hadn’t yet seen a sequel. Aliens (1986) and Terminator 2: Judgment Day (1991) had both appeared seven years after the first films, suggesting that there was not exactly an automatic impulse to generate franchises. In fact, in 1994 we might expect to find Hollywood relatively untainted by franchise fever. Hence it should also very different from Hollywood today—if it’s true that franchises drive out other films. If all the anti-franchise critics are right, 1994 should also be a distinctly better year for auteurist fare, art-house movies, and stand-alone popular films.

What do we find in Premiere’s fall preview? In some ways it looks like a strong season. Apart from Pulp Fiction and Interview with the Vampire, there are Tim Burton’s Ed Wood, Robert Altman’s Prêt-à-Porter, Woody Allen’s Bullets over Broadway, Luc Besson’s Léon (aka The Professional), Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption, and Alan Rudolph’s Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle. Notable as well are Quiz Show and Nell. Buried in the “Also in Season” box at the end are Frederick Marx’s documentary Hoop Dreams, Clerks (with Kevin Smith not even mentioned), and Krysztof Kieslowski’s Red.

Alongside these films, though, there are the usual forgettable items: Junior (the Arnold Schwarzenegger-gets-pregnant comedy), Little Women, Disclosure, The Pagemaster, Radioland Murders and a bunch of other films that don’t get watched much anymore.

Putting aside the huge blockbusters of 2007, the fall season of 1994 doesn’t look all that different from the kind of fare Hollywood puts out now. Many of the same auteurs are with us. Burton is making Sweeney Todd (again with Johnny Depp). Allen continues to direct at his usual fast clip, albeit now in Europe. Besson promises more “Arthur” animated features. Darabont’s Stephen King adaptation, The Mist, is due out in November. Jordon’s thriller, The Brave One, starring Jodie Foster, is announced for September. Smith’s Clerks II came out last year. Tarantino tried to find inspiration by moving from dime novels to grindhouse movies, this time without success. The influence of his 1994 classic, however, is still very much with us. Even the unexpected success of Hoop Dreams is echoed by the recent vogue for documentaries. We have lost some of our major directors since 1994, of course, including Altman and Kieslowski, and Rudolph seems finally to have ceased being able to fund his eccentric independent films.

Is the fall season of 1994 typical? Premiere also used to run a chart of the year’s major releases called “Critics Choice,” which used a one-to-four-stars system to show how favorably each film was received by fifteen popular reviewers. Looking at the rest of 1994’s more memorable films, we find more familiar current directors , including Spike Lee (Crooklyn), the Coen Brothers (The Hudsucker Proxy), Ron Howard (The Paper), Oliver Stone (Natural Born Killers), John Waters (Serial Mom), Ben Stiller (Reality Bites), Zhang Yimou (To Live), Bille August (The House of the Spirits), Ang Lee (Eat Drink Man Woman), Kenneth Branagh (Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein), Ken Loach (Ladybird Ladybird), James Cameron (True Lies), Robert Zemekis (Forrest Gump), Peter Jackson (Heavenly Creatures) and on, and on. Steven Spielberg would be there, too, if Schindler’s List and Jurassic Park hadn’t both come out in 1993. There is also the smattering of adorably eccentric (Four Weddings and a Funeral, The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert) or beautifully acted (The Madness of King George) English-language imports of the sort that find an audience each year—not to mention the unclassifiable Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould. And 1994 was no richer in subtitled fare than recent years have been: apart from Red and To Live, the only other notable foreign-language import is Queen Margot.

I don’t want to push the similarities between this randomly chosen season and the current Hollywood situation too much. There certainly are some differences. The rise of blockbuster franchises has changed the pattern of releases, with the big series films occupying the summer and Christmas seasons. It’s interesting, for example, to note that the year’s top grosser, Forrest Gump, was released in July (a week before True Lies), while today it would probably be given a fall slot. That’s just a matter of timing, though. Even there we have distributors using counter-programming for smaller films, some of which inevitably become surprise successes, like The 40 Year Old Virgin.

So just what is it that got pushed out by franchises?

(For more on sequels and franchises, see the May discussion by the Badger squad and Henry Jenkins on the third Pirates of the Caribbean film. A lot of comments have been added to the latter since I first linked it. I see that Henry’s post was also cited by Lee Marshall in an article in the June 22, 2007 issue of Screen International, “The People’s Choice.” Marshall makes the point that reviewers who lambaste big franchise films often do so in a condescending way that implicitly criticizes the public for liking them.)