Archive for January 2007

Weather Bird flies again

Road to Morocco.

From DB:

On one shelf, close to my desk, I keep books of essays that have satisfied me across the years. Lined up across about four feet, these remind me of the virtues of critical prose. Shaw, appropriately I suppose, sits on the far left, followed by Dwight Macdonald, Jacques Barzun, Gore Vidal, Robert Hughes, Christopher Hitchens, Frederick Crews, Kenneth Tynan, Susan Sontag, and a few others. Picking up any of these and rereading an essay pushes me to try to write more pungently and think more clearly.

I know nothing about jazz, but decades ago I enjoyed reading Gary Giddins’ Weather Bird column in the Village Voice. Then I picked up his 1992 essay collection, Faces in the Crowd and immediately he won a place on my shelf. His buoyant essays are compulsive reading. His piece on Jack Benny, “This Guy Wouldn’t Give You the Parsley Off His Fish,” kicks off the volume, and I think it’s a masterpiece. After reading it, you want to watch a string of Benny TV shows. It’s followed by another triumph, Giddins’ dynamic case arguing that Irving Berlin more or less invented American entertainment. This brace of pieces is just the start. As you’d expect, Giddins spends time on musical greats, from Billie Holliday to Larry Adler, but he shows a fine range, discussing Spike Lee, Robert Altman, Myrna Loy (in an essay titled “Perfect”), and writers from Faulkner to Elmore Leonard.

In an era when journalistic criticism is identified with either puffery or deflation, Giddins is the master of unabashed, admiring appreciation. His judgments are balanced, but he almost never resorts to the swordthrust beloved by his mentor Macdonald, who wrote some of the funniest and most insulting passages in all of American film criticism. You sense that if Giddins dislikes something, he’d rather not write about it. The French call it “the criticism of enthusiasm.”

When he likes something, he can merge dissective intelligence, subtle distinctions, and unfussy prose as very few writers about the popular arts can. Not for him the turbocharged syntax and hyphenated adjectives of fanboys. One word or phrase does the job. Watch how he brings Jack Benny before us, linking him to a tradition of comic types that is even echoed in the turns of the sentences:

The character he created and developed with inspired tenacity all those years–certainly one of the longest runs ever by an actor in the same role–was that of a mean, vainglorious skinflint; a pompous ass at best, a tiresome bore at near best. To find his equal, you have to leave the realm of monologists and delve into the novel for a recipe that combines Micawber and Scrooge, with perhaps a dash of Lady Catherine De Bourgh and a soupçon of Chichikhov; or better still, a serial character like Sherlock Holmes, who proved so resilient that not even Conan Doyle could knock him off.

Benny as Micawber plus Scrooge: perfect. At near best: perfect. And if you worry that “a soupçon of Chichikhov” teeters on pretentiousness, the “knock him off” at the end makes the sentence snap shut, reassuring you that Giddins writes in that American demotic which is our birthright.

The Benny essay is reprinted, justly, in Giddins’ 2006 collection Natural Selection: On Comedy, Film, Music, and Books. This book is twice as long as Faces in the Crowd, and it’s a feast. We get fine pieces on Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and the Marx Brothers, and sensitive celebrations of Antonioni, Lang, Doris Day (he loves her), and Harold Lloyd, along with in-depth studies of many classic films. “Cowardly Custard,” a sketch of Bob Hope, rises to the level of the Benny apologia. If you don’t rush immediately to see a Hope film after reading it, you’re not the man or woman I think you are. I turned to The Ghost Breakers and was rewarded with the moment when Hope peers around a pillar at Paulette Goddard and asks with a hesitant leer, “Am I protruding?”

The Benny essay is reprinted, justly, in Giddins’ 2006 collection Natural Selection: On Comedy, Film, Music, and Books. This book is twice as long as Faces in the Crowd, and it’s a feast. We get fine pieces on Chaplin, Keaton, Lloyd, and the Marx Brothers, and sensitive celebrations of Antonioni, Lang, Doris Day (he loves her), and Harold Lloyd, along with in-depth studies of many classic films. “Cowardly Custard,” a sketch of Bob Hope, rises to the level of the Benny apologia. If you don’t rush immediately to see a Hope film after reading it, you’re not the man or woman I think you are. I turned to The Ghost Breakers and was rewarded with the moment when Hope peers around a pillar at Paulette Goddard and asks with a hesitant leer, “Am I protruding?”

Lucky for us that The Perfect Vision, The New York Sun, and other venues have opened their doors to Giddins’ film writing. (For a sample, along with lots of other material, visit his site.) Although he occasionally scolds, it’s the criticism of enthusiasm that reigns. When he started to write about jazz clubs, “I could focus on what I admired–on what I wanted you to admire or at least know it existed.”

In his music criticism and biography (the wonderful Bing Crosby life Pocketful of Dreams), Giddins interweaves technical details, anecdotes, and thoughtful commentary. In writing about films he does much the same, blending observations about form and craft with insinuating evocations of how a movie plays on the screen. Not many film critics today would notice how the first shot of Lloyd’s masterful Girl Shy unobtrusively sets up its climax. He writes of The Letter:

From the opening nighttime pan of a rubber plantation, interrupted by a gunshot and fluttering cockatoo, and finished with an inexorable closing in on Better Davis, who has followed her victim on to the verandah and pumped five more bullets into him, you know you are in the hands of ardent filmmakers and can only hope that they sustain the inspiration for another 90 minutes. They do.

Or this:

Eyes without a Face begins with a lengthy traveling shot, as Alida Valli races through the night with a crumpled corpse in the backseat, enclosed by an endless line of skeletal trees and accompanied by Maurice Jarre’s funhouse score–imagine Philip Glass programming a carousel.

Giddins has an unapologetic respect for African American performers in studio movies. Of Ivie Anderson’s “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm” in A Day at the Races, he notes:

This scene was cut from TV for years and decried as racist by sensitive white liberals. They are free to skip it; the rest of us can head straight for DVD chapter 22 to see Anderson in clover. Racism manifested itself less in Catfish Row stereotypes than in the failure to cast her in other movies.

On Sammy Davis Jr. Giddins mixes sober praise with sorrow:

Davis had once been renowned as a performer of spectacular gifts who could do everything. Sadly, “everything” usually proves to be the most evanescent of talents. His early appearances were virtuoso displays of dancing, singing, and mimicry that defied indifference; he would stop at nothing until he brought the audience into his fold. . . . Davis’ besetting sin was not extravagance, philandering, imbibing, or reckless optimism concerning a president. It was trying to live life as if color did not matter. He was a naïf savant.

For Giddins fans who are cinephiles too, there’s a quiet satisfaction in learning from the autobiographical sketch that launches Natural Selection that he started as a film critic for The Hollywood Reporter. Of course he continues to write about music and literature, and his essay on Classics Illustrated comic books will tingle every baby boomer’s spine. Still, by circling back to movies, Giddins shows himself one of the great contemporary American film critics. In his hands criticism finds its justification as subtle, eloquent admiration.

P. S.

The Good German finally made its way to Madison, and so I’ve posted a quick postscript to my earlier blog on the film’s attempt to recapture 1940s film technique. Nice try, but….

My name is David and I’m a frame-counter

DB here:

Elsewhere on this site and in Figures Traced in Light (Chapter 1) and The Way Hollywood Tells It (second essay), I sometimes say rude things about the rapid editing in today’s films. But I’m actually a fan of fast cutting–when it’s precise, functional, and thoughtful. Most directors today don’t think about their cuts. Godard: “The only great problem of cinema seems to be more and more, with each film, when and why to start a shot and when and why to end it.”

My interest in fast cutting goes back to the 1960s, when I was first reading Eisenstein and seeing fims by Godard, Truffaut, Hitchcock, and, yes, Richard Lester. At first I would wind sequences backward and forward on a 16mm projector, stopping to pull the film off the reels to hold up to the light. For my dissertation on French cinema of the 1920s, I had a chance to examine films by Abel Gance, Jean Epstein, Germaine Dulac, et cie on editing tables or rewinds. In quickly-cut passages, the patterns of shot-length showed how a director could control the visual pace.

Over the years, when I studied 35mm film prints regularly, I periodically returned to my love of rhythmically cut passages. I studied Dreyer’s Passion de Jeanne d’Arc, the work of the Soviet Montage directors, and Asian action movies, from 1920s Japanese swordplay items to 1990s Hong Kong martial-arts sagas. Somewhat surprisingly, I found that Ozu, as in everything else, was there too; a lot of his intermediate spaces (landscapes, objects in rooms) are cut arithmetically.

By examining 16mm and 35mm prints, I could measure shot lengths in frames. In a sound film, a 24-frame shot would last a second on the screen. Things were trickier in gauging the cutting of silent films, since they were shown at rates between 16 and 24 frames per second. But at least the number of frames per shot gave me a sense of rhythmic relationships. A sequence in Jean Epstein’s Chute de la Maison Usher (1928) displays an arithmetical unfolding that would yield a distinct tempo at any projection speed of the era.

Directors have been counting frames for a long time. Experimental filmmakers like Brakhage did. Ozu had a special stopwatch built to register feet and frames during filming. Hitchcock cared about frame counting too. In Film Art‘s chapter on editing (pp. 224-225 of the new edition), we show how the gas station fire in The Birds gains impact from its steadily shorter shot lengths. The first shot lasts 20 frames, the second 18, the third 16, and so on down to 8 frames.

In sum, frame counting is one valuable way to find how a director can govern the pace of our pickup. When shots come this fast, our involvement can quicken as well.

When 35mm plays us false

For silent films, counting frames can be a problem if you have a “stretch-printed” copy. Since silent films often ran at something less than 24 frames per second (sound speed), some later film versions have been printed to repeat frames at certain intervals, to stretch out the print to 24 fps. That makes it easier to add a synchronized score to the print.

In the 1970s the Soviets were big fans of this procedure, rereleasing many classics by Eisenstein, Pudovkin, and others in stretch-printed 35mm and 16mm copies. The Soviet Montage filmmakers definitely counted frames, calculating the shots to play off each other rhythmically, so adding extra frames spoiled things. Worse, the stretch-printed versions often played sluggishly at sound speed, making the action spasmodic and blurring the figures. The result completely wrecked the rhythmic effects the directors were after. Even today, stretch-printed copies of Eisenstein’s Strike are in circulation.

Videotape and the 3:2 pulldown

Videotape arrived. The first Betavision players measured something–a little tally counter clicked away–but you couldn’t be sure what was being counted. Then came digital displays that measured hours, minutes, and seconds. But what about frames? When I tried to count frames on videotape, I found that the figures didn’t match those I got from film frames.

To see why, we have to remember that television developed its own frame rates. The technical details can get pretty daunting; see here for one account. I also recommend Jim Taylor’s DVD Demystified and Kallenberger and Cvjetnicanin’s Film into Video. Still, we non-engineers can get a general sense of what’s at stake.

There are two primary television standards, NTSC and PAL. NTSC (for National Television System Committee) is used primarily in North America and Japan. PAL (Phase Alternating Line) is common throughout Europe and Asia. Because NTSC video operates at a 60-Hertz refresh rate, the rate for individual frames is close to 30 per second. (Actually, it’s 29.97 fps.) The problem is this: Do you run 24-frame movies at 30 frames per second on television? This would make them look speeded up. Or do you pad out a second of film to fit a second of TV? American engineers took the second solution and created the so-called 3:2 pulldown.

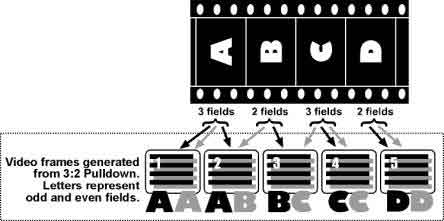

In interlaced video, each “frame” is really two venetian-blind image fields presented as one image on your screen.(1) In the 3:2 pulldown, some film frames are selectively repeated to fill out the video playback format. The film is converted to video by making two fields from one film frame and then three from the next frame. Here is a useful diagram from a site on video transfer.

The 3:2 pulldown preserves three of the original four film frames (video frames AA, CC, and DD above).

But you don’t see this exactly this result when you jog/shuttle through a videotape frame by frame because the VCR has been engineered to display the 3:2 pulldown slightly differently. Stepping through a videotape, we find that some frames will show phases of movement and some repeat a phase. Depending on your playback machine and the tape itself, you may get varying patterns. Usually I see four video freeze-frames decomposing a movement, then they’re followed by an extra frame in which nothing changes.(2) That process turns 4 film frames into 5 display frames. Adding 6 repeated frames to the original 24 frames yields 30 video frames a second. I find that you can get a rough sense of the number of frames in the original shot by ignoring the repeated frames in the video display, but the video frames showing decomposed movement may or may not correspond to the actual film frames.

Laserdiscs and the frame count

Those heavy, rainbow-flashing 12″ discs: Cinephiles loved ’em. They gave us a sharper picture, properly letterboxed, along with terrific sound. Aficionados today still prefer the rich digital sound of laserdiscs to the compression of many DVDs.

Most laserdiscs used the CLV (Constant Linear Velocity) format, which preserved and even exaggerated the effects of the 3:2 pulldown. Counting frames meant stepping through the stills and ignoring the repeated ones, as with videotape, but often the coupled frames (AB and BC above) shivered wildly. But in the high-end CAV (Constant Angular Velocity) format, laserdiscs were able to make each stored frame pristine. This is why people thought that laserdiscs would be used archivally, for storing paintings, photographs, manuscript pages.

A bonus of the CAV format was that in transferring motion pictures to disc, one film frame could be matched to a single video frame. In fact, each film frame was assigned its own number, so the counter display spit out digits with blinding speed. During normal playback, the 3:2 repeated frames were added in, but in STEP mode, CAV laserdiscs gave you the original film frames one by one–steady, crisp, and bright. Frame-counting gained a new piece of hardware.

DVD and frame counting

Laserdiscs used optical analog technology for the image track. But consumers wanted something easier to handle, on the model of the music CD, so in came digital image technology via MPEG-2 and the DVD.

Despite all the differences between digital video and film (color, resolution, artifacts, etc.), DVDs in the NTSC format gained one advantage over tape. Like CAV laserdiscs, they could preserve the 24-frames-per-second rate of film. Essentially MPEG-2 technology encodes the film frame by frame. Flags on the DVD instruct the player to regenerate extra frames during playback. For a more detailed explanation, go to Dan Ramer’s article here.

The result is that during freeze-frame viewing, a DVD can yield the original film frames. Watch the Universal DVD of The Birds, and the frame-counts correspond to the 20-18-etc. layout we discovered on a 16mm print. Your remote’s STEP button moves through the original frames, hiding the repeated ones that were shown during normal playback.

But not always. DVDs can sometimes play us false.

Before the DVD was a gleam in Warren Lieberfarb‘s eye, I studied King Hu’s wonderful A Touch of Zen on an editing table. There is a lot of frame arithmetic in the editing. During one swordfight, the mysterious stranger leaps away from the blows of Miss Yang and lands in a medium shot. He steps back, tipping up his face to reveal that she’s bloodied his head. He stares in astonishment. The shot lasts only 20 frames.

Yang stands still, holding her sword at the ready. The shot lasts a mere 9 frames, which dynamizes her stillness.

The stranger turns and runs out of frame in another twenty-frame shot. The static shot of Miss Yang now becomes an abrupt punctuation, and the stranger’s panic registers on us more sharply by being caught up in a repetitive rhythmic pattern.

Yang plunges after him, in a twelve-frame shot.

All four shots add up to less than three seconds of screen time, but they’re completely legible. It seems to me that the shots accentuate a pause in the fight by inserting a striking micro-rhythm, and then they dissolve that by letting the fighters continue the combat. Would that today’s filmmakers thought out their cuts so precisely! (If you want to learn more about King Hu’s editing style, see my Planet Hong Kong and the essay on him in the forthcoming Poetics of Cinema.)

But if you examine these shots on the US DVD of A Touch of Zen, you’ll find that the number of frames is way off from the film. The first and third shots run 25 frames each, not 20 frames; the second shot runs 11 frames (instead of 9), and the fourth 15 (instead of 12). Why? Inspection reveals our old friend, the 3:2 pulldown, at work. Improper authoring has left in the frames that should be jettisoned in step playback.

An even more severe instance: The sequence from Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher that I admired in my dissertation days. It has become hash on the US DVD. When I try to count frames, I find that apparently the silent original has been stretch-printed and subjected to the 3:2 pulldown. When I click through the frames on a DVD player, I find that many frames are repeated, and some shots have doubled in length.

The lesson: Not all DVDs are created equal, or equally accurate in their correspondence with the original film.

What about PAL?

NTSC interlaced video has a 60-Hertz refresh rate. But PAL has a 50-Hertz one. That means not 30 video frames per second but 25. What do you do in transferring a film? The obvious answer: You speed it up.

Films shot at 24 frames per second tend to run at 25 in PAL videos, both tapes and DVDs. As a result, many films on European video run shorter than they did in the theatre, or on American DVDs. For example, Preminger’s Where the Sidewalk Ends runs 94:41 on the Fox DVD, but the same film, known as Mark Dixon Detective, runs 90:49 on the French DVD release. That’s a difference of nearly four minutes. PAL video playback of a 24 fps movie runs about 4% shorter than the original. For this reason, some European films are shot at 25 frames per second, to facilitate transfer to PAL.

So counting frames on a PAL videotape or DVD won’t necessarily mislead you on the number of frames, since none is repeated. That’s the case with our Touch of Zen example. Both the UK and the French DVDs of King Hu’s film yield the correct frame-counts for the shots in question. We just need to remember that each frame is onscreen for a tiny bit less time. In other words, each shot will contain the right number of frames, but that shot will be briefer in screen duration .

Note to Sátántangó fans: Yes, that means a much shorter movie. The PAL DVD available from England’s Artificial Eye claims to run 419 minutes; if you disregard opening and closing credits, the film runs a shade under 400 minutes. But the 35mm version I clocked here runs 434 minutes sans credits. So if you want to add 34 minutes to your life, watch the import DVD.

Note to Asian cinema fans: For reasons I don’t understand, many Hong Kong DVDs yield very blurred and vibrating still-frame images, not corresponding to the frames of the original film. These discs may be using a downmarket authoring process, or there may be problems converting to and fro between PAL and NTSC.

Progressive scan

This all applies to interlaced video, the original television broadcast format. Now we have progressive-scan video, for plasma and LCD displays and computer monitors. A progressive display, still adhering to the 60-Herz standard, is rigged to preserve the right number of film frames without repeating any.

But it does so by in effect combining two film frames together, and the step function may skip over several frames, or create a blurred composite that isn’t there on any frame. This is especially apparent on media-player computer software.

When I run my Touch of Zen shots on my computer, I get wildly abbreviated frame-counts in Step mode. In WinDVD, for instance, the first shot of the UK DVD registers as 8 frames, not 20; the second as 3 frames, not 9; the third as 9 frames, not 20; and the fourth as 6, not 12. Same thing for Epstein’s Fall of the House of Usher. On a tabletop DVD player there are more frames than in the original film; on my player’s software, there are fewer.

For this reason, I’d avoid trying to count frames on a computer’s media player.

So…..

Frame-counting is a nifty tool for discovering some secrets of filmmaking, but when we work from a video copy, we need to keep in mind the constraints of the various formats. And whenever possible, check the film!

(1) To complicate things, the scanning of alternate raster lines never yields a single complete frame. Before the image is fully completed at the bottom, it’s being refreshed at the top! To this extent, the video frame doesn’t have the stable, singular identity of a film frame. It can be encoded to correspond to a film frame, but as an image display, even a frozen frame is always in the process of being filled in. It’s just that our eyes, not designed to track such small-scale processes, are fooled.

(2) A quick sampling of my old VHS tapes shows that occasionally a tape doesn’t exhibit effects of the 3:2 pulldown. My Facets VHS copy of Where Is the Friend’s Home? plays back on two machines without any repeated frames. Perhaps this comes from making the transfer from a PAL master tape?

Visionary outlaw mavericks on the dark edge; or, Indie Guignol

An American Crime

From DB:

In an article originally called “Sundance Movies Are Bad for You!” but now more tamely titled “The Trouble with Sundance,” Richard Corliss complains that indie movies have become so predictable that they form a genre in themselves. They focus on relationships, especially those of a dysfunctional family or a fumbling love affair, and treat their principals with a dutiful mix of pathos and humor. Where, he asks, are the more imaginative narrative and stylistic maneuvers fostered by the Coen brothers, Jarmusch, Tarantino, and the like?

That’s only half the story. True, indie films are often pallid comedies and melodramas. But just as often, and sometimes at the same time, they’re desperately sensationalistic. In these the formal conservativism to which Corliss objects is wedded to hot-button content. We call a bland Indie film quirky, but there are others we call dark. They’re Indie Guignol.

The very distinction is suspiciously simple, I admit. I don’t deny that there are independent films that manage to be riveting without being either cutesy or stomach-churning. Recent examples are Ramin Bahrani’s Man Push Cart, Phil Morrison’s Junebug, and Julia Loktev’s Day Night Day Night. Some of these even won praise at Sundance. But most such films don’t get the sort of enthusiastic applause that darker efforts do, nor are their makers heralded as iconoclasts.

Where did Indie Guignol come from? As with most things Indie, sex, lies, and videotape was surely an important model, though I suspect that another template was furnished by David Lynch’s Blue Velvet, that Hardy Boys mystery turned fetid. In any case, for a couple of decades the indie scene has taken on ever more provocative themes and subjects, from Suture and Boxing Helena through Happiness and Boogie Nights to Hard Candy and Little Children.

Reports from Sundance indicate that the trend isn’t flagging. There’s a docudrama about men having sex with horses. Hounddog, which Todd McCarthy portrays as a God’s Little Acre for the new century, is already better known as the Dakota Fanning Rape Movie. Reviewing An American Crime, a film about torturing a child, Screen International‘s Mike Goodridge tells us that it centers on “unspeakable and repeated violence and abuse.” Needless to say, he’s full of admiration. “Although often excruciating to watch, it is so well-crafted and well-acted that its portrait of casual savagery in the ‘burbs resonates long after the end credits roll.” In this climate, no wonder that the MPAA is politicking to rehabilitate the NC-17 rating, which would presumably help indie films from studio boutiques get onto more screens.

The central conceit of Indie Guignol is that to be creative in cinema you have to be dangerous. James Mottram’s book The Sundance Kids: How the Mavericks Took Back Hollywood is an informative overview of Indiewood, but too often it equates being a “maverick” and having a “vision” with an adolescent naughtiness. He approvingly reports Fincher’s reaction to the ending of Se7en. “While it reinforced the notion that justice will prevail, Fincher takes a private goulish pleasure in imagining Mills being ‘carted off to be gang-raped by prison inmates.'” Mottram notes, perhaps unnecessarily, that Fincher has a “sour vision of humanity” (155). Likewise, Sharon Waxman’s Rebels on the Backlot celebrates the fact that her “rebel auteurs” made movies that “combined their brutality with humor” (xi), as if violence and comedy didn’t ricochet off one another in virtually every student horror film ever made.

Producer Christine Vachon, who named her company Killer Films, likewise identifies creative energy with edginess. Her book A Killer Life provides informative glimpses into independent production while showing how to create an indie brand based on scandal. For Vachon, indie cinema is outsider art; she tries to “guard a filmmaker’s autonomy and agency” and let him or her tell “unconventional stories” (15).

Actually, only certain kinds of unconventional stories. When Vachon is told that The Laramie Project is focusing on Matthew Shepard’s murder, she replies that she’d rather make a film about the killers and “their reported meth addictions, and the speculation that they had known (and maybe even slept with) Shepard” (19). One in-the-works project is “about the Bakelite plastics family murder plus a little pinch of incest” (209); another is about the killing of the Scarsdale Diet doctor.

Vachon, like most of her colleagues, thinks the indie tradition is dangerous.

The most dangerous movies Killer has made are the ones that reflected the real world back with the least amount of artifice: Kids, Happiness, Boys Don’t Cry. . . What they are, are stories without clear heroes or redemptive “arcs.” People may or may not get what’s coming to them, and those plots spook an industry premised on wish fulfillment and getting the girl (75).

The dismissal of Hollywood genres is characteristic of the Indie attitude. A good movie can be based on getting the girl, as Girl Shy, The Awful Truth, A Man’s Castle, The Apartment, Jerry Maguire, and Tsui Hark’s The Chinese Feast show. Likewise, just because a movie spooks the suits doesn’t mean it’s good. A movie lacking heroes and redemptive arcs and a happy ending may still be a shoddy piece of work.

Perhaps Indie Guignol is picking up on the Gothic turn of the New York art gallery scene, seen in the lucrative Saatchi show “Sensation” and Matthew Barney’s fascination with innards and dismemberment. Just as likely, the indies’ grotesquerie shadows the rise of gore and splatter in the mainstream. From The Silence of the Lambs to Saw, Hostel, and last year’s The Hills Have Eyes, we’ve seen the horror film turn up the dial on nihilism and disgust, and both the low-budget indies and Indiewood have moved in sync. It would be ironic if the vaunted personal visions of Solondz, Larry Clark, and the like were made palatable and marketable by the hyperviolence of the dreaded megaplex movie.

Very often the predictable nonconformist is just as orthodox as the conformist. Long before the sort of recyclings that Corliss identifies, unconventional moviemaking turned out to have its own conventions–unfulfilling or risky sex, pedophilia, damaged self-images, chancy links among the characters. More surprisingly, the daring indie film often trades on the same clichés that haunt program pictures and prestige items. Sunny small towns harbor nasty secrets, manicured suburbs conceal rot, sex is degrading and only an excuse for power plays, rural folk are racist peckerwoods, corporations grind your soul, siblings vie for parental approval, serving in the military makes you a hairtrigger bully, high school is hell, and so is grade school. Dark visions these films may have, but the landscapes and populations they reveal are pretty familiar. The marketing genius of Miranda July’s You and Me and Everyone We Know was to blend Indie Quirky and Indie Guignol with the figures of the kooky woman and the lovable loser well known from romantic comedy.

Despite its well-worn materials, Indie Guignol is treated as trailblazing. Mottram, Waxman, and other admirers consider Fincher, Russell, Sofia Coppola, and their peers as unswerving rebels against the Hollywood tradition. That tradition, represented by Lubitsch, Ford, Hawks, Hitchcock, Borzage, Sternberg, McCarey, Minnelli, Lang, Preminger, and all the rest, is to be pitied for lacking today’s freedom of expression, or even that afforded in the holy 1970s. Yet this condescension doesn’t consider that these studio directors made virtues of their limitations and produced something far more enduring than almost anything on offer from our outlaws. I’m reminded of Truffaut’s remark on the breakdown of the studio system: “We said that the American cinema pleases us, and its filmmakers are slaves; what if they were freed? And from the moment that they were freed, they made shitty films.”

Mottram quotes Christine Vachon as saying of Todd Haynes’ Poison, “All of Todd’s movies confound expectation. That I think is their greatest strength. If people don’t keep making movies like that, the medium will get stagnant and die” (24). But shock value is only one way to thwart expectation. I grant that America’s oppressive political climate encourages us to think that rebellion is inherently virtuous; but some rebellion is just posturing. If Vachon really wanted to confound expectations and tell “unconventional stories,” she would back a film about a woman who voted Republican, served in the military with pride, found a job in a vets’ hospital tending to the Iraq wounded, and never once considered experimenting with autoerotic suffocation by means of a colostomy bag.

I’m not against visceral and disturbing filmmaking. I’ve written appreciatively about hard-edged Hong Kong movies, from Chang Cheh blood feasts to harrowing items like The Untold Story. Buñuel and Stroheim are worthy of respect, as are films like Godard’s Weekend and Cronenberg’s Videodrome. The point is simply that good filmmaking doesn’t have to flay its audience. Ozu, Mizoguchi, Naruse, Dreyer, Renoir, Ford, Tati, Keaton, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Kiarostami–the list could go on indefinitely–present distinctive views of the world. They don’t try to be outlaws; they don’t strut; they don’t trail brimstone; they are not cool. Their films display a mature tact that goes deeper than either quirkiness or bleeding-edge daring.

Most Indie Guignol flaunts itself as cynically knowing, tapping into some dark current that the squares can’t face. The filmmakers I’ve just mentioned have done something that’s rather different and that’s becoming increasingly rare. Their subject usually isn’t life’s corrupt underbelly but the poetry of the drab and the ordinary. Their work is formally innovative, but in quiet ways–ways that have taken us decades to understand. Their films, even when they’re pessimistic, have a poise, nuance, and complexity that most independent cinema never approaches. Instead of talking about being radical, these directors have made movies like grownups. They’ve counted art more important than attitude.

Too many toons? Then why are they making so much money?

Kristin here—

Back in my December 10, 2006, entry, I discussed some reasons why CGI animated features often seem better than their live-action competition.

In passing I mentioned that industry news sources were discussing whether there were too many CGI films made last year. “Studio executives and commentators continue to debate whether there are now too many CGI films coming out. Indeed, the November 24 issue of Screen International says, ‘Much has been made this year of the seeming over-saturation of studios/computer-generated titles, with critics and analysts pointing to growing movie-goer apathy.’”

I realize that industry pundits have to have something to write about at year’s end. Unlike the critics, they don’t have the ten-best lists and who-will-win-the-Oscar options, so they assess box-office trends. One year indies suddenly are in, the next year the big sequels have surged back, and the next year the indies are back. To read the trade papers, one would think that trends come in neat one-year cycles. Maybe studio executives plan their upcoming films according to these supposed trends, but films being greenlit now will only appear years in the future. By then the cycles will have turned over and over.

The “too many toons” issue looks to me like a tempest in a teapot. If you look at the various box-office lists for 2006, CGI animation did better proportionately than live-action films did.

Let’s start at the bottom. The December 25-31, 2006 issue of Variety ran Nicole LaPorte’s “2006: H’w’d diagnoses its duds.” (I’d link to the online version, but it seems inexplicably to have disappeared from Variety.com.) There she talked about the 10 biggest failures of the year. Despite the title, the diagnosis and choice of films was done not by studio employees but by an “inhouse Variety poll.” To be included, films had to be relatively big-budget items that could plausibly have been hits on the basis of the track records of their directors, stars, or source material. (e.g., Lady in the Water, Poseidon, A Good Year).

One animated feature made the list: Flushed Away. I have already expressed my liking for this film and made some suggestions about why it undeservedly failed. Presumably it is a coincidence that DreamWorks’ head of marketing is leaving the company to set up on her own. She had presided over many hits for DreamWorks, and her new firm will continue to work with its releases. Still, the Variety story announcing the move refers to the lackluster performance of Flags of Our Fathers but does not mention Flushed Away or earlier Aardman films.

OK, so one of ten flops as designated by Variety staff members was a CGI feature. Nine of them are live-action films.

Now let’s go to the top of the list. The ten highest domestic box-office grossers in 2006 included four CGI hits: Cars, #2, Ice Age: The Meltdown, #7, Happy Feet, #8, and Over the Hedge, #10. On the worldwide chart, these four films rank high as well: Ice Age: The Meltdown, #3, Cars, #5, Happy Feet, #10, and Over the Hedge, #11. In the domestic market, 6 other toons make the top 100. So, 4 out of 10 toons are in the top ten, while 6 out of 90 live-action films make that short-list. I’m no math whiz, but that looks like 40% versus 6.6% to me.

Of course, as I pointed out back in the infancy of this blog, grosses aren’t the best measure of success. How much a film cost obviously determines how profitable it will be. Casino Royale, the #9 domestic box-office pull in 2006, took in $164 million—it is unanimously hailed as a hit, but it cost a reported $150 million to make. There’s also the factor of “prints and advertising”: how much it costs to order thousands of copies of a film and how much is put into the various forms of publicity. As I noted, P & A costs are seldom announced.

Recently, however, Kagan, a company with access to proprietary industry figures, put out its list of the 10 most profitable films of 2006. (Only films that “open wide” are included. That used to mean something like 500 or 600 theaters, but as more films come out on thousands of screens, the term has become pretty vague.) Kagan does factor in P & A expenditures alongside the filmmaking budget to determine a figure for a film’s total costs. It also has a formula to calculate the total income from all major forms of distribution: not just theatrical box-office, but DVD and the various other video and TV income for a film. The result is about as accurate a notion of profitability as we outside the industry are likely to get.

Going by Kagan’s reasonably reliable profitability figures, how do animated features stack up? We all know that CGI is expensive. A live-action feature that depends very heavily on computer trickery might spend as much as half its budget on special effects.

Surprisingly, CGI animation can be profitable. Kagan pronounced Ice Age: The Meltdown the most profitable film of 2006. With total production, marketing, and other direct costs of $256.4 million and an estimated $1.05 billion worldwide gross from all distribution channels, the proportion words out to 4.11 on the “Kagan Profitability Index.” (A film generally is assumed to be profitable if it achieves a KPI rating of 1.75 or more.)

Three other animated films made the top ten on the Kagan KPI list: Cars was the 8th most profitable film, Over the Hedge the 9th, and Happy Feet the 10th. These figures are all the more remarkable when one considers that a high proportion of tickets sold for animated films tend to be at the lower children’s admission prices.

The real question isn’t really whether there are too many animated features coming out. It’s actually how large the G and PG markets are. Live-action films come in all ratings, so they are not all competing with each other. R-rated horror films compete with other edgy teen-oriented movies but not with family-friendly holiday movies. Toons tend to compete with each other, but they also compete with G and PG live-action films. Flushed Away was not done in because it opened on the same weekend as another CGI toon. It presumably sank partly because it was released on the same day as The Santa Clause 3.

In 2006, live-action films for children didn’t do as well among domestic grossers as animated ones did. Night at the Museum was #5 with $205 million, but the next highest film of this type, The Santa Clause 3, took in $84 million to end up at #22.

Bottom line—and that’s what we are talking about here—there doesn’t seem to be a glut of animated films so far. Let’s see what Shrek 3 and the other CGI toons of 2007 lead the pundits to diagnose a year from now.