Archive for October 2020

Little stabs at happiness 6: Breathe

Commander in Chief (2020).

Last summer, in hope of reviving spirits in these times, I ran a series of clips I admired for their ability to arouse and energize. They created a sort of disciplined exhilaration through adroit editing, camerawork, and music. They reliably gave me a lift, and maybe you too.

Now, in the Caligula phase of Trump’s presidency, it seems appropriate to pay my respects to a masterpiece of engaging agitprop. I’ve registered my reservations about the Lincoln Project in an earlier entry, but there’s no denying that these walking wounded of right-wing partisanship have recruited some very talented filmmakers. Their “Covita” assemblage was superb, and they have outdone themselves with this morning’s triumph.

Here it is:

Experience it–but then we should study it.

It’s an excellent example of what we call in Film Art associational form–a blending of images, sounds, and texts to imply ideas and provoke feelings, in the manner of lyric poetry. The text itself is a lyric poem, at once ode, elegy, and apostrophe. Demi Lovato’s choked, rising and falling vibrato is in itself powerfully expressive. Just as important, the audiovisual texture enriches the text. Sometimes it’s a matter of the image echoing the words, and sometimes the associations are purely visual. An element in one shot, such as a gesture or facial expression, will call up something similar, or a contrast.

The effects flash by quickly. Taken just as images, what do these shots have in common?

Nothing but a pulse: Labored breathing on a ventilator matches the flicker of an emergency vehicle’s turn signal, as if life is running out before our eyes..

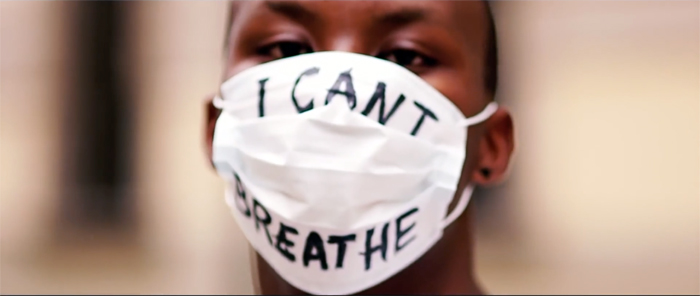

The structure mimics the song’s layout. We move from problem to solution, from crisis to resistance, from emptiness to crowds, ending on a resolution that puts action in the hands of the viewer. Threading it all together is the way “I can’t breathe” gets redefined. The phrase shifts from being associated with George Floyd and other victims of police atrocities, to the COVID-19 pandemic, before adding a twist: Trump’s own bout with the virus, capped in a direct address to him. How does it feel to be able to breathe? By the end breathing becomes metaphorically linked to voting. How does that feel?

As I mentioned in that earlier entry, contemporary agitprop reminds us how much every filmmaker owes to traditions. The techniques used in Commander in Chief stretch far back into the history of cinema; the upraised fists of the finale could have come straight out of Soviet montage.

It might seem pedantic to talk this way about such a powerful piece of cinema. But the point is that the things we study are really out there, crafted by creative filmmakers and having an impact on viewers. The art we care about has concrete effects, and in studying it we can clarify just how those effects are achieved. Analyzing forms and styles can broaden our sense of what cinema can do, and it can strengthen our respect for the filmmakers who explore it.

A similar analysis could be undertaken with many of the best current polemical documentaries, like Unfit and Totally Under Control. These galvanize us not just through their subjects and “messages” but through their fresh use of conventions of form and style. (The sequences of Totally Under Control devoted to First Capon Jared Kushner will remain models of satiric montage.) As with the best of Adam Curtis’s work, these are important contributions not just to political discourse but to the history of film as an art form.

Those goosebumps, that quivering gut, those tears? They come from cinema, grand synthesis of the arts.

Another documentary working in this vein, Leo Hurwitz’s Strange Victory, is discussed here. It’s completely appropriate to our current crisis.

For other reflections on the Trump coup attempt, go here and here and here and here.

P.S. 9 December 2020: After winning an Advertising Age award for the Lincoln Project campaign videos, Rick Wilson explains the strategy and assesses their success in the first of four parts.

P.P.S. 24 December 2020: More backstory on the making of these videos from producer/director Ben Howe.

Totally Under Control (2020).

Vancouver envoi: What happens in movies happens between your ears

Summer 85 (2020).

DB here:

One of the nicest things anybody ever said to me came from Jacques Aumont, the distinguished French film scholar. He was visiting us in the early 1980s and I showed him a book manuscript I had just sent to the publisher. He read the first three chapters and said, “You remind us of something important. The spectator is thinking.” The book eventually came out as Narration in the Fiction Film.

In emphasizing that the spectator thinks, at least a little, I was driven to pay special attention to openings. The opening is where a film sets up information about its story world, about the action that will take place in it. We usually call this exposition. But a film also attunes us to the how as well as the what: how the story will be told. Exposition, in other words, includes introducing us to the characters and their situation but also to the ways we’ll learn about them. In the book I called the latter the “intrinsic norms” of narration.

But exposition isn’t simply a part of the plot, a chunk of opening material we need to digest. Exposition, the narrative theorist Meir Sternberg shows, is a process. In revealing what we call “backstory,” circumstances that predate the first scenes we see, exposition can go on throughout a film. (Kristin talks about this in her entry on Inception, and in revised form in our Nolan book.) So it turns out that the spectator has to keep thinking, keep reevaluating what’s being told about the story world and the way the story is told.

Three films showcased at the Vancouver International Film Festival set me thinking about these matters. Two depended on surprises, and these stemmed from the way exposition was handled. The third had very sparse exposition, asking us to gradually fill in story background through drifts and whiffs of information. In all cases, our enjoyment depends on thinking.

Surprise!

Bettina Oberli’s My Wonderful Wanda updates the ingredients of classic bourgeois comedy for the modern world of migratory caregivers. Josef and Elsa Wegmeister-Gloor oversee their pampered and confused son and daughter. Into the household comes a servant who is exploited for sexual favors by the old man. Wanda, the nurse brought in from Poland, is today’s equivalent of the chambermaid lusted after by both father and son.

As in most domestic comedies of class relations, Wanda the worker is no fool. Her duties help support her father, mother, and sons back home, and she proves herself a shrewd negotiator from the start. When Elsa asks her to perform extra chores, she demands more money. And when Elsa’s stroke-felled husband is willing to pay for sex, she agrees. Their secret bargain will, in good farce fashion, come to light in the most embarrassing way possible.

I went into the film knowing much less of the plot than I’ve just told you, so I want to keep back the rest. (Alas, the trailer overshares.) I was able to appreciate the way that Oberli’s tight script kept the surprises coming. Her script finds an admirable balance between clear structure and unpredictable turns.

Here the exposition is, in Sternberg’s terms, mostly concentrated and preliminary. The early scenes fill us in on the basic situation. Wanda is among several women met at the bus by Elsa. This is a compact way to suggest how much this class depends on the arrival of emigrant labor. Wanda is then taken to the family’s sumptuous villa. We learn about the situation as she does, and this introductory stretch culminates in Wanda’s introduction to her cramped basement room. In good traditional fashion, the exposition quickly encourages us to sympathize with the protagonist by showing her treated unfairly. On the basis of the information we get, the film’s first “act” becomes a tensely rising action in which Wanda becomes victimized by the petty conflicts that wrack the family.

A second long section begins in a lighter key, with the dismissed Wanda returning after some months, in a scene parallel to the opening. This chunk provides another concentrated dose of information, bringing us up to date on the family’s situation. Comic complications emerge when the family has to cope with a new, more pressing set of demands.

In good Renoirian fashion, Oberli gives everyone a dose of sympathy. The frailties of the son and daughter get nuanced and softened, and we see this coddled pair as less selfish than self-destructive. The action tapers into cringe comedy (drunken embarrassment) and farce (an errant cow), but it’s steered by carefully modulated character revelation, particularly on the part of Elsa, who is played by an indominatable Marthe Keller.

My Wonderful Wanda keeps surprising you to the very end; it trains us not to take everything for granted. There’s even a classic theatrical denouement, itself twisty, which is undercut by a final shot of GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema) uncertainty. Yet after each reversal, you think it had to be that way. What happens later is consistent with the exposition we’ve built up.

Surprise, postponed

Concentrated exposition, gathered in an opening or elsewhere, sets our expectations, so new story information can modify or revise them. For instance, when Wanda is summoned late at night to Gunther’s bedside, I assumed he needed meds or some help going to the toilet. The expository scenes had set her up as a traditional caregiver. So I was surprised when she mechanically slipped into what became clear was a sexual routine. That prompted me to recalibrate my sense of their relationship, and it made me aware of the limits of what I’d assumed.

Which is to say that exposition as a process is usually partial. We don’t get everything in the backstory at once, and sometimes what’s suppressed is central (as in My Wonderful Wanda). A more extreme example is François Ozon’s Summer 85 (Été 85). Here the expository information is distributed much more widely across the film. We get the backstory only gradually and piecemeal. Because some important information is withheld, the film nudges us toward certain expectations that need to be adjusted.

Again, I have to be careful about spoilers, so let me talk generally. In the book that I mentioned and for many years since, I’ve written a lot about flashbacks. One common schema for flashbacks is the crisis structure. The plot starts near a story’s climax and then suspends the outcome in order to shift back into the past and show how the crisis came about. The crisis structure can provide a film’s overall intrinsic norm of narration, so we expect that this pattern will carry through from scene to scene.

Ozon, another elegant storyteller, knows we have learned the crisis structure. When the opening of Summer 85 shows the teenager Alex dragged into a corridor and then interviewed by police authorities, we’re encouraged to summon up our experience of other movies. A crime has been committed, and he’s either a witness or a suspect. Ozon sets up a familiar to-and-fro pattern between past and present, an investigation and the mysterious crime leading up to it.

The distributed exposition provides flashbacks that take us chronologically through the events leading up to the night of the arrest. Alex is drawn into a love affair with David, a charismatic older boy. With his mother David runs a shop on the beach. She is slightly scatterbrained and seems unaware of their passions, while Alex’s parents are likewise in the dark (and surely disapproving). When the English au pair Kate shows up on the beach, Alex fears David will abandon him, and we expect that a classic romantic triangle will drive the film forward.

Except that’s not quite what happens. As Alex’s jealousy deepens, we might expect a sort of Patricia Highsmith crime to ensue. Instead, Ozon dares to go with a less brutal but more plausible turn of events–one that makes us reevaluate why Alex is being investigated, and what his actual crime is. By distributing exposition slowly across the whole film, Ozon not only creates a lot of curiosity about what has actually happened, he’s able to arouse expectations that will get challenged by new revelations. He exploits the how of narration to modify our understanding of what has occurred–and, it turns out, why.

I’m sorry to be so cryptic, but I face the reviewer’s dilemma of not giving away plot twists that should take you by surprise. Here, though, the surprises aren’t short and sharp, as in My Wonderful Wanda. They unfold more gradually and allow you time to think–about the characters and their motivations, and about what you took for granted might have happened. You might even feel a bit ashamed for misjudging Alex, who turns out to be loyal and forgiving in ways we might call unexpected. Yes, dancing is involved.

Surprise?

My Wonderful Wanda has a straightforward arc of conflict and resolution. Summer 85 is more nonlinear, skipping to and fro through time, but it too can be plotted as a drama of tension and release. What then to say about Kala Azar? It’s another film that teaches us how to watch it, and how to think through it. But it seems to lack those traditional patterns of coherence.

Or rather, it has other patterns. Instead of a drama of conflict and change, it explores a situation built out of routines, gradually revealed and eventually varied. This is another plot strategy, one familiar from “art cinema.” It builds a mystery into not only the story action but into the way the story is told. What is going on? And why am I told about it in this way?

Start with the title. It refers to a severe infectious disease spread to animals and humans by sandflies. It’s currently raging as a pandemic in over seventy countries. But the film Kala Azar is less about the disease (although we spot some lesions on characters who might be infected) than about the relations of humans and animals–specifically, some marginal Greeks scrounging a living on the outskirts of a city, along with the dogs, cats, and other creatures that wander into their lives.

There are three strands of action, each with its own routines. Most prominent are the couple, a young man and woman working for a service that cremates household pets. The couple live mostly on the road in their van, gathering pet remains from households and bringing them back to a central facility. They then return the ashes (not always scrupulously preserved, it seems) to the waiting owners. Another couple, the woman’s father and mother, keep stray dogs in their house. A third line of action involves Orguz, a migrant worker glimpsed from time to time at a chicken farm nearby.

The central couple have started adding roadkill to their cargo, as if believing that these creatures too deserve a serious farewell to life. And at certain points the story strands meet, although glancingly. In something close to a traditional climax, the young man, provoked by seeing a shooting party, takes a decisive action.

All of what I’ve told you is built up through dozens of short scenes, usually without dialogue. There’s probably more going on here than I’ve been able to grasp on one viewing. But the sparse, widely distributed exposition, and the apparent looseness of the plot challenge us to fill in things as best we can. Just as important, by not providing a traditional dramatic arc, director Janis Rafa encourages us to shift our attention to other aspects of her film.

We’re invited, for instance, to examine shot composition, to explore the landscapes on which the camera dwells, to scrutinize textures and gestures. These items are sometimes seen at one remove, through dirty panes of glass or layers of focus or in slim apertures.

Entire scenes often chop off faces in order to emphasize the contact that the bodies make with their surroundings, or to turn bodies into pure pattern, as when two grieving pet lovers are shown dressed identically.

These visual strategies may seem a bit arty, but I think they build up a tactile sense of the environment of these routines. Rafa has said that she wanted to evoke the “animalistic” quality of the imagery, which isn’t only a matter of a low camera position. The sensuous quality of the vegetation, streams, and roaming dogs comes across strongly. Kala Azar earns its severe gravity through its patient attention to details of a world in which humans and animals interact in very tangible ways. Stray animals meet stray humans, and the visual style registers the encounter with quiet nuance.

From concentrated preliminary exposition, to distributed and elliptical exposition, to what we might call minimal exposition: This continuum shows some creative options available to filmmakers in telling their stories. Each one invites us to build up expectations, to reconsider new information in the light of what we knew (or thought we knew), and to assemble a coherent line of action. In other words, we think. That’s not all we do, but it’s a big part of how we watch movies.

As usual, special thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during this reliably exciting festival. This is usually the time of the year when Kristin and I wish we lived in Vancouver, and that feeling is sharpened by the health crisis now engulfing so many countries. Cinema helps keep us civilized.

These and other films we’ve reviewed should be making their way to other festivals, so we hope you have a chance to catch up with them.

For more on the narrative strategies I’ve discussed here, see Meir Sternberg’s magisterial Expositional Modes and Temporal Ordering in Fiction (1978). This is in my view one of the great books in narrative theory.

For more on narratives built on threads of routines, see this earlier entry on Chop Shop and other films at Ebertfest. An entry on editing pursues the between-your-ears theme.

Kala Azar (2020).

Vancouver: Continuing our world tour

Eyimofe (2020)

Kristin here:

Turning back from documentaries to international art cinema, I’m recommending three films, two from Eastern Europe and one from Nigeria.

Servants (2020)

Ivan Ostrochovsky, an established Slovak producer of documentaries, whose first feature Goat (2015) was successful on the festival circuit, has followed it up with a second. Servants showed in the Encounters program at Berlin and earned enthusiastic reviews (Variety, Screen Daily).

The film opens with a flashforward as a body is dumped on a dark country road–a scene that will later be replayed when we have more information as to who the victim is. Suddenly a title, “143 days earlier,” appears, and the plot focuses on two beginning seminary students, Juraj and Michal. Briefly we seem to following their personal stories, but their introduction to the seminary routine serves largely as exposition for us. Signs of Communist repression of Catholicism begin to surface. A defiant note anonymously posted leads to a confiscation of all the students’ typewriters (above) in a search for clues as to its author.

The organization behind the repression is an actual historical agency, “Pacem in Terris,” which spied on and controlled the Catholic Church, from 1971 to the early 1980s. (The film is set in 1980.) Its goal was to seek out any signs of political activity, i.e., rebellion, among the clergy and seminarians. Juraj and eventually Michal join a small clandestine group of students working against Pacem in Terris. They become the targets of a ruthless agent, “Doctor Ivan,” (seen at the right below). He is the man responsible for the body-dumping in the opening.

Servants, impressively shot in black-and-white, has been called a film noir, and it certainly has all the sinister tone, the chiaroscuro lighting, and the ill-fated heroes of that genre, mixed with the trappings of art cinema.

Ivanovsky demonstrates how much suspense and dread can be packed into a mere eighty minutes.

On the Quiet (2019)

Another short feature that packs a lot of drama into its 81 minutes is Hungarian director Zoltán Negy’s first feature, On the Quiet. It deals with the touchy subject of alleged sexual abuse of a minor. The film’s smart script, co-written by Negy, is credited as having been developed at the “My First Script Workshop” of the Zagreb Film Festival. As I have suggested elsewhere, such workshops run by festivals have come to play a major role in making such sophisticated storytelling possible.

The main strength of the script is how it maintains an utterly balanced ambiguity about the allegations at its core. The beginning introduces the protagonist, Dávid, first violinist in a student orchestra in a prestigious music school. The teacher-conductor, Mr. Frigyes, employs eccentric techniques with the players. When Dávid fails to perform his solo part adequately in rehearsal, Frigyes tells the other students to gather round to massage his shoulders. This apparently helps him improve.

Soon Frigyes is giving private lessons to 14-year-old Nóri, a pretty, inexperienced but talented cellist. The first lesson we witness has him relaxing her by having them toss a ball back and forth. He touches her elbow and shoulder to adjust her posture. That is all that we witness. Yet soon Nóri complains to Dávid that the teacher has done “weird” things to her, but she won’t specify except to say they were “intimate.” Disturbed by this, Dávid gives her his phone to secretly record a lesson with Frigyes. The resulting dialogue could equally be the teacher directing the girl’s cello technique or instructions about sexual caresses. Dávid’s girlfriend points out to him that Frigyes uses his touchy-feely approach with all the students, but he persists in trying to discover the truth.

The situation escalates as Dávid informs a female counselor, who interviews Nóri and her mother. The girl denies that anything untoward happened. Still, the gossip spreads and the situation eventually threatens Frigyes’s position at the school. Did he abuse the girl? Did he simply not realize how his hands-on guidance could make the girl uncomfortable? Is she naively over-reacting to teaching methods that don’t seem to bother the other students?

I have seen one review that simply declares that the teacher is a perverted abuser, but the film seems far more subtle to me. Without ever implying that Nóri’s complaints should be dismissed, the film explores the effects of the spreading rumor on all those involved. It does show that no real investigation of the claims, which would be the logical way to proceed, ever takes place. In short, it is a careful presentation of its sensitive subject.

The film is well directed, though far from flashy. It does have the occasional striking shot, as when Dávid ponders the situation one evening (above) or sits talking with Nóri on a playground merry-go-round in an overhead shot (see bottom) that hides their expressions and suggests his confusion.

An interview with Negy about the film suggests that he is a thoughtful as well as a promising director–and one with three more film scripts underway.

Eyimofe (2020)

From the early 1990s, Nigeria has built up a thriving production of low-budget, DIY and professional films. At first distributed on VHS tape and then on digital disk, these have had enormous success at home and among the African diaspora. Kunle Afolayan formed a company that commanded government support and product placement to finance October 1 (2014), which played at film festivals, mostly within Africa. More recently, Kemi Adetiba’s The Wedding Party (2016) premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival, and Kathryn Fasegha’s 2 Weeks in Lagos premiered at the 2019 Cannes festival, where it was somewhat overshadowed by Mati Diop’s Atlantics, playing in competition.

Now comes Eyimofe (This Is My Desire, in English, but much of the coverage on the internet uses the Yoruba title). It is directed by twins crediting themselves as Arie and Chuko, though their family name is Esiri. They have created an formally and stylistically impressive film that gives fascinating insights into the society of the sprawling conurbation of Lagos, an area with an estimated population of 21 million.

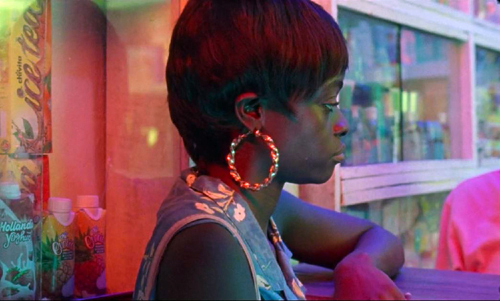

Arie Esiri studied Screenwriting and Directing at Columbia University’s School of the Arts, while Chuko Esiri earned an MFA, also in Screenwriting and Directing, from New York University’s Tisch School of the Arts. They wisely shot Eyimofe on 35mm, and the lush visuals exploit the bright colors of Sub-Saharan African clothing (see top of entry) and furnishings. Cinematographer Arseni Khachaturan adds bright colored light, especially at night and in shops, to create a gorgeous look (above and below).

The plot is split into two parts via titles: “Spain” and “Italy.” In each part, the main character is struggling to migrate. Mofe, an electrician, is gradually collecting the documents and money he needs for his move to Spain, where he will adopt the name Sanchez. Rosa, working both as a beautician and cocktail waitress, has similar aspirations to relocate to Italy, taking her younger sister Grace along. Both protagonists must scrape up money to pay for the passport, visa, fake letters promising employment, and other expenses. There are many complications, including a death in Mofe’s family and an unexpected revelation of the lengths to which Rosa and Grace will go to secure their passage.

The two stories are largely separate. There are moments when the characters pass each other briefly, and Grace even chats with Mofe at a little repair stand he sets up. Yet none of these chance encounters involves any causal connections between the two plots.

Early in the film Mofe visits an open-air “office” where a man who specializes in getting passports and visas–for a hefty fee (see top, where Mofe is on the right). In the background we glimpse a woman getting a passport photo taken against a white cloth. Late, near the beginning of the “Italy” section, we meet Rosa, having her passport photo taken in front of a similar backdrop (below). She’s in a different passport shop, however, suggesting that such informal establishments, vital for aspiring emigrants to cut through the red tape and delays of government procedures, are common in Lagos. It’s also the first of several parallels between her story and that of Mofe, clearly intended to suggest how common such struggles to leave for Europe are.

Unlike Mofe, Rosa aspires to a fun, modern social life, buying fancy clothes while sleeping with her landlord (who happens to be Mofe’s landlord as well) and then starting an affair with a wealthy Lebanese-American businessman. Her nightlife offers the occasion for flashy images, including the positively Godardian composition of her in a car with her friends (at the top of this section). As with Mofe, an unexpected death helps derail her plans, and we learn just how far she and Grace had been willing to go in their hopes for a better life abroad.

Eyimofe is a powerful film and well worth seeking out at a festival or on streaming. It’s having its UK premiere at the London Film Festival, which starts tomorrow. For a brief discussion by the directors about the film’s background, financing, and festival life, listen to this BBC radio interview. For a detailed description of the film’s success during its screenings during the Berlin festival from a Nigerian point of view, see here.

As a remarkably rich and successful festival draws toward its end, special thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during it.

On the Quiet (2019).

Vancouver: “It’s the Arts”

Frida Kahlo (2020)

Kristin here:

I wonder how many of my readers will recognize the source of this entry’s title. Is Monty Python’s Flying Circus still the perennial classic it was among young people for decades after its original series was broadcast? That brief sentence was the title of the sixth episode of the first season, shown in 1969, though I didn’t see it until some years later. The episode itself has little to do with the arts, but for some reason that particular title stuck with David and me, as few if any others did. Whenever we have encountered a TV program or a review, often something pretentious, one of us will turn to the other, or both simultaneously, and say, “It’s the Arts!”

The Vancouver International Film Festival has an admirable custom of showing many documentaries. They often deal with ecological issues and Canadian subject matter. One prominent thread, however, is documentaries about the arts. These are known as MAD, or “Music, Art and Design.” Although, as I mentioned in my previous entry, I tend to stick to the Panorama program of international fiction films, I always try to attend a few of these arts documentaries when they fit in with my interests. Most of these are in fact wonderful, not pretentious. Still, I am too accustomed to the phrase, and I think automatically, “It’s the Arts.”

Paris Calligrammes (2019)

One documentary that I was keen to see is Ulrike Ottinger’s autobiographical account of her years living in Paris during the 1960s. Ottinger is known, at least in the US, primarily for her experimental fiction films, like Freak Orlando (1981) and Joan of Arc of Mongolia (1989). I had not encountered her work since then and was eager to catch up with her at this year’s festival.

Ottinger did what many young people think of doing but never carry through on. She left home at the tender age of twenty for an exciting new life. In 1962, she moved from Germany to Paris, where she lived until 1969 before returning to West Germany. In France she lived among Bohemians and stayed long enough to witness the protests of May, 1968.

Naturally she was hugely influenced by her experiences. She tells of encountering artists and ideas: “In my euphoria, I wanted to convert all my experiences directly into art.” But how? Early on, she muses on how to convey those experiences of decades ago:

I ask myself that same question over fifty years later. How can I make a film from the perspective of a very young artist I remember, with the experience of the older artist I am today? In Paris, I followed in the footsteps of my heroines and heroes. Wherever I found them, they will appear in this film.

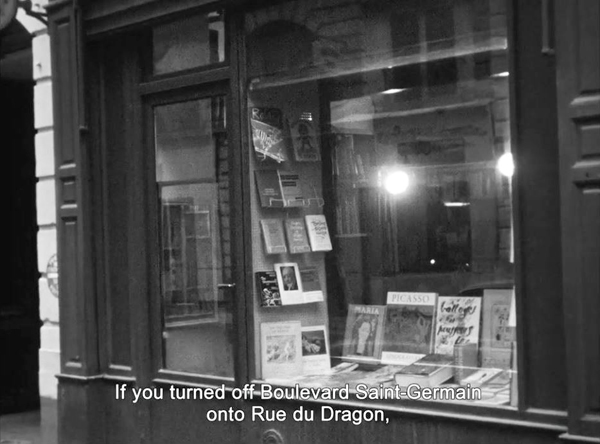

There is no footage of Ottinger from this period, and relatively few relevant photographs. Instead she wisely organizes the early portions of the film around her connection to an extraordinary bookshop that was a center of artistic and intellectual life at the time: Calligrammes (above), founded in 1951 by Fritz Picard, who had fled Nazi Germany in 1938. As a dealer in rare German and other books on the arts, Picard became host to innumerable avant-garde artists and intellectuals. Ottinger recalls buying many books on the German Expressionists and other avant-garde artists and movements of earlier decades.

(David bought some books for his dissertation on French Impressionist cinema at Calligrammes in the summer of 1973. Picard died in November of that year, though the shop was continued for a time by others.)

Ottinger became a friend of Picard and socialized with the patrons and visitors of the shop. Below, she’s in the black vest, sitting beside Picard at a party. She also was indirectly influenced by the great artists of the past, such as Hans Richter, who had frequented Calligrammes. In one sequence she flips through the guest-book signed by many a famous visitor, and we see clips from films like Ghosts before Breakfast, which influenced her.

Following this section, Ottinger gives us sequences on the effects of the Algierian war on her friends in Paris and describes the protests of May, 1968, some of which she was able to see from her apartment near the Sorbonne.

Perhaps inevitably, Paris Calligrammes reminded me of some of the Agnès Varda’s late autobiographical work. Ottinger is less lyrical and personal, as well as being more overtly political. There is more of a sense of name-dropping, at least in the early section. Still, who wouldn’t be interested in hearing about the early life of someone who has had such adventures? Ottinger also describes the influences on her by the artists she learned about and met. The brief clips from her own films should inspire a new generation of film buffs to seek out her work.

Like so many of the films at the Vancouver International Film Festival this year, Paris Calligrammes was shown in Berlin. For an enthusiastic and informative review done at the time, see Richard Brody’s piece in The New Yorker.

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)

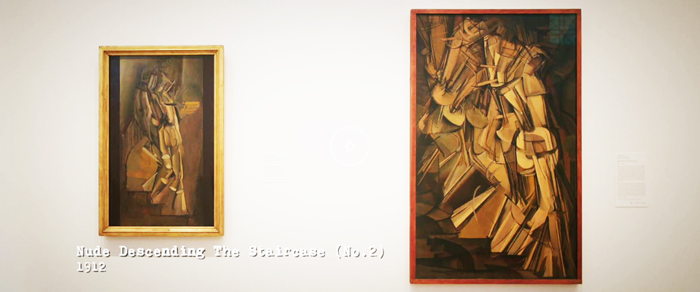

I am of two minds about Matthew Taylor’s documentary on Duchamp. It presents an excellent overview of the artist’s career and work, and one could learn a great deal from it. It makes clear, for example, the relationship between Duchamp’s early ready-mades and the fact that they were mostly subsequently lost and much later replaced by replicas–all with the artist’s cooperation. It puts his important early painting “Nude Descending a Staircase” (see bottom) in its historical context.

There are the usual experts explaining Duchamp’s intellectual approach to his artworks and his considerable influence on subsequent generations. We are not given much indication concerning who some of these experts are. The identifying labels often just say “Curator” or “Art historian” without linking the experts to any institution or publication. I tried looking one of them up on the internet and couldn’t find him. I’m sure, however, that they know Duchamp’s life and work well.

These experts are also almost all extremely enthusiastic about Duchamp’s work and especially the impact he has had upon art–not, as they emphasize, just specific trends but absolutely all subsequent art up to the present. Early on in the film, before we have been introduced to most of the talking heads, a voiceover declares, “Without him, imagine where we would be. We’d be painting in the style of Matisse or Picasso. That’s what modern art would be without Duchamp.”

(Ironic note: Duchamp’s stepson, Paul Matisse, is the grandson of Henri Matisse.)

That’s a pretty remarkable claim. It’s hard to think of a period that long in the post-Medieval era when art has just frozen in place for a century. Surely innovative styles and individual artists would have come along and produced distinctive work that did not depend on Duchamp’s main claim to fame, his demonstration that anything could become an artwork if we regard it as such. Did the Soviet Constructivists depend on Duchamp’s idea? Did the German Expressionists? Do highly individualistic artists? (See the section below.) Do manga and graphic novels, which are coming to be thought of as worthy of attention as art–not just because someone found them and declared them so, but because they contains qualities that were considered artistic well before Duchamp?

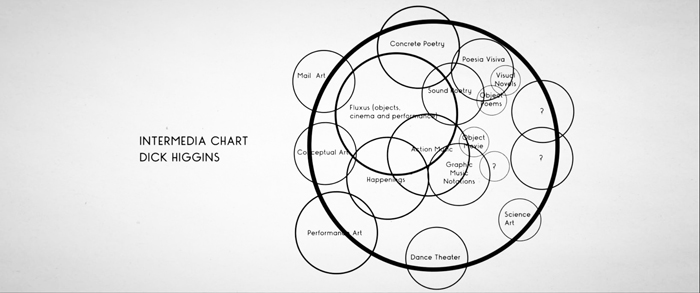

To be sure, Duchamp did have a huge impact, as this chart, shown in the film, suggests. It was devised by Dick Higgins, artist and co-founder of Fluxus. (The absence of Pop Art among the circles is rather puzzling, though it does figure in the film.) One could, however, devise many other circles for trends and institutions that do not reflect that impact.

Toward the end of the film, the experts go further, suggesting that Duchamp encourages the democratization of art by suggesting that anyone can be an artist, whether on their own or by taking and re-purposing existing artworks or objects or sounds. Yet would we say that the many outsider artists of the past century who have come to the recent attention of taste-makers had anything to do with Duchamp? And fanart, if that is included in this vast generalization, existed before Duchamp.

Despite the obvious excitement the experts display in extolling Duchamp’s work, someone watching the film might be less sympathetic, given the debatable state into which Postmodernism in general has led the art world. As one inevitably thinks, what’s next, Post-Postmodernism?

Duchamp himself seems, according to the film, to have had considerably less enthusiasm about his own artworks, preferring perhaps the idea of them rather than the execution. He took twelve years to complete the Great Glass and declared himself pleased with the results when an accident severely cracked its surface. He did not bother to keep track of his ready-mades, most of which disappeared. One wonders why he bothered to follow the initial venture into that area with “Fountain” (a urinal signed “R. Mutt 1911”), since subsequent ready-mades like “Hat Rack” (above) make the same intellectual point.

Late in life Duchamp seemingly gave up art-making to devote himself to competitive chess. After his death it turned out that from 1946 to 1966 he had been working on “Étant donnés,” a peep-show view of a spreadeagled nude woman, based on his mistress during part of that time. Despite the raptures expressed by the experts, it looks like it could be considered revenge porn. But only, presumably, if one calls it that.

Only one of the experts, Peter Goulds, departs from the general unquestioning idolization of Duchamp. Near the end he says,

Later in life, of course, he must have found it incredibly amusing to hear people latch onto his theories as though they were universal truths, when actually his whole life was about bucking those very conventions and defying them. So I’d like to suggest that his form of so-called conceptual art was a much more playful exchange. I’m not so sure about how even serious he was about it himself. Here he throws these things out as suggestions, with thought. Others, perhaps more needy than himself, would make these rules be therefore solely applicable.

Frida Kahlo (2020)

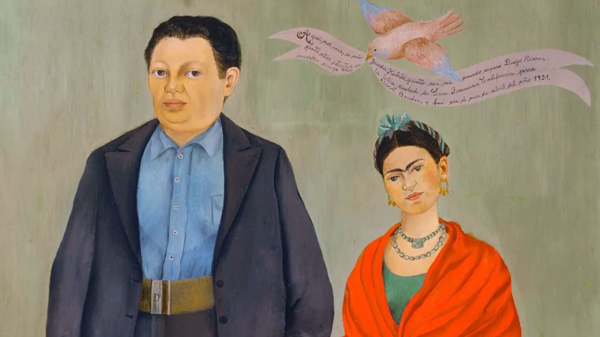

Frida Kahlo is one of those artists who don’t appear to owe much, if anything to the influence of Marcel Duchamp. As the film makes clear from the start, she was aware of European artistic movements and developments. Still, neither she nor her husband, muralist Diego Rivera, seem to have absorbed much from them. Kahlo always denied that her later work was Surrealistic, and one might rather attribute its fantastical elements derive more from the Latin American tradition of Magical Realism.

Indeed, the whole idea that Duchamp influenced all of modern art comes to seem remarkably Amero- and Euro-centric if one considers that it implicitly either scoops highly individual artists like Kahlo up into one enormous category or eliminates them from that category altogether.

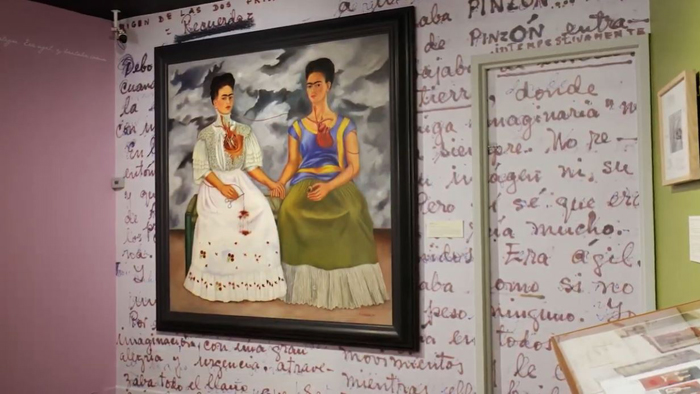

I found Frida Kahlo more satisfying than Marcel Duchamp. Its experts are all clearly identified as to their position and institution. Some are curators of the institutions which own her works, such as the Museo de Arte Moderno in Mexico City. There “The Two Fridas” is shown (see top) as the curator discusses it.

These experts are as enthusiastic about their subject as those in the Duchamp film, but they are focused entirely on recounting Kahlo’s life, her social context, and the influences on and changes in her style across her life. For example the simple presentation of “Frida and Diego Rivera,” an early portrait done shortly after their marriage, gives way to the more sophisticated and symbolic “The Two Fridas.”

Archival photographs and film clips illustrate the eras of the places where Kahlo lived and traveled. The impact of the lingering effects of her injuries in an extremely serious traffic accident in her youth, her travels with Rivera in the US, and the rockiness of their marriage are all discussed to help clarify the often cryptic visual references in her paintings.

In short, Frida Kahlo is a model of a staightforward and informative documentary on an artist. I was pleased to be introduced by it to its producers, Exhibition on Screen. In business since 2011, it has made twenty-six such documentaries. These are shown in theaters and festivals initially, before being made available on disc and streaming on their website. Frida Kahlo is promised for streaming on October 20.

Once again, thanks, as usual to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, Curtis Woloschuk, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

Marcel Duchamp: The Art of the Possible (2020)