Archive for June 2019

A hundred years ago, and less, at Cinema Ritrovato ’19

DB here:

Hundreds of films, thousands of passholders, sweltering heat (105 degrees Fahrenheit on Thursday). Dazzling tributes to Fox films, Youssef Chahine, Eduardo De Filippo, Henry King, Felix Feist, silent star Musidora, sound star Jean Gabin, and other themes. Many filmmakers from Africa, South Korea, and Europe, as well as master classes with Francis Ford Coppola and Jane Campion.

Yes, Cinema Ritrovato is on steroids this year.

And as we always say: There are so many tough, indeed impossible, choices. Kristin has been faithfully following the African series, while I’ve hopped between restored and rediscovered Hollywood classics and the films from 1919. Today I’ll report a bit on the latter, with an addendum on a major filmmaker’s ave atque vale.

1919 bounty

Song of the Scarlet Flower (1919). Production still.

By the end of the 1910s, the feature-length format had become well-established, and a bevy of directors in Europe and America were launching their careers. Abel Gance, Victor Sjöström, Mauritz Stiller, John Ford, Raoul Walsh, Cecil B. DeMille, Lois Weber, Charlie Chaplin, Douglas Fairbanks, William S. Hart, Mary Pickford, and many other figures had already made impressive work. 1919 brought us some outstanding titles. There was von Stroheim’s Blind Husbands, Griffith’s Broken Blossoms and True Heart Susie, Lubitsch’s Madame DuBarry, along with the lesser-known Victory of Maurice Tourneur, the first part of Sjöström’s Sons of Ingmar, and the overbearing, delirious Nerven of Robert Reinert.

Bologna showed none of these. Its massive 1919 lineup featured some classics in restorations, notably Capellani’s The Red Lantern (starring Nazimova), Dreyer’s debut The President, and Stiller’s Herr Arne’s Treasure. As a sidebar there was the 1919 Italian serial I Topi Grigi, a fun sub-Feuillade exercise in crooks and chases with some nifty shots. And there were a great many fragments and short films from that year, including a Hungarian entry by Mihály (Michael) Kertész (Curtiz).

Less known than Stiller’s official classics is The Song of the Scarlet Flower, a wonderful open-air drama about a young farmer’s wanderings and his heart-rending romances with three women. In a new digital version, it emerged as one of the most sheerly beautiful films I saw at Bologna. The central action sequence, in which the hero dares to ride a log through rapids to the very edge of a waterfall, gained even greater tension thanks to the swelling orchestral score by Armas Järnefelt–the only original score to be preserved for a Swedish silent.

1919, German style

Der Mädchenhirt (The Pimp, 1919). Production still.

Then there were two remarkable German films unknown to me, both by directors better known for later work. Der Mädchenhirt (The Pimp) was by Karl Grune, most famous for The Street (Die Strasse, 1923). The plot follows a shiftless young man who casually becomes a pimp and pulls women into prostitution. Introducing the film, Karl Wratschko pointed out that many Weimar films warned of sexual misbehavior, and certainly the young hero of this film gets ample punishment for his sins.

Stylistically, Der Mädchenhirt was typical of much European cinema of the late ‘teens, when the tableau style, which promoted intricate staging with few analytical cuts, was losing force. Grune mostly handles action in ensemble shots broken up by axial cuts to closer views. If German filmmakers weren’t quite as editing-prone as other European directors, that may be because they didn’t have access to American models. Not until January 1920 were Hollywood films of the war years imported into Germany.

Another film carried this moderate continuity style to an intriguing extreme. Tötet nicht mehr! (Kill No More!) framed a plea against capital punishment within a family drama. Sebald, the son of a by-the-book prosecutor, falls in love with the daughter of a former prisoner. When Sebald is cast out by his father, the couple take up a theatrical career playing Pierrot and Colombine. But then Sebald blocks the theatre director from seducing his wife, so the director blackballs them and they can’t get work in other shows. Visiting the director, Sebald quarrels with the man and kills him. He’s arrested, tried, and sentenced to death.

Tötet nicht mehr! displays some remarkable visual qualities. Cross-lighting in the climactic prison scenes sculpts Sebald, the priest, and the lawyer Landt in a bold variety of ways.

Director Lupu Pick (Sylvester, 1924) uses this dramatic lighting to enhance the tableau-plus-axial-cut approach. The police are examining the crime scene and questioning Sebald. A depth composition gives us the corpse in the lower foreground, the detectives in the middle ground, and way in the back, the barely-visible face of Sebald perched between the shoulders of the two central men.

One detective walks to the distant background to question Sebald. Anybody else would have staged this bit of action in the better-lit zone on the left, where a detective talks with his colleagues. Instead, far back, a single pencil-line of light picks out the edge of Sebald’s face and body.

An axial cut-in presents a tight two-shot of the cop and Sebald–again, made stark and tense by the lighting.

The plot of Tötet nicht mehr! is a generational one, starting with the tragedies befalling the woman’s father. These scenes introduce the sympathetic lawyer Landt, who tries to help the family throughout its troubles. Landt becomes the vehicle of the film’s message against capital punishment, which gets full airing in the boy’s trial.

In the films of the 1910s, courtroom scenes tend to be more heavily and freely edited than others. This is largely because of the need to cut among judges, jury, witnesses testifying, lawyers pontificating, and the onlookers. Pick exploits the situation with dozens of shots of participants. We also get optical point-of-view shots showing Sebald awaiting the jury’s verdict by staring at the doorknob of the jury room. There’s even a “lying flashback,” which dramatizes the prosecutor’s inaccurate reconstruction of the quarrel that led to the crime.

Most impressive, I think, is the pictorial progression in Landt’s impassioned plea to the jury to let Sebald escape execution. Among many reaction shots and reestablishing framings, Landt is rendered in increasingly close shots as he addresses the judges and the jury–and us.

The textural lighting and the ruthless elimination of the background reminded me of the trial scene of André Antoine’s Le Coupable of 1917, run at an earlier installment of Ritrovato.

There were plenty of other 1919 films on display, several of which I have yet to see. But this should give you an indication of the service that Cinema Ritrovato continues to render to the cause of understanding film history.

Not so long ago

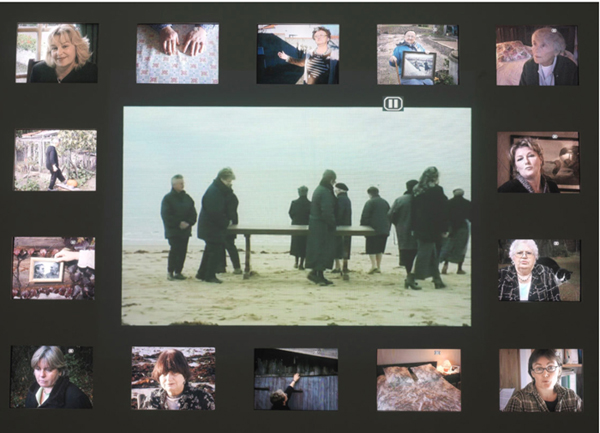

The Widows of Noirmoutier (2006).

Film history close to our time was the subject of Varda par Agnès, the filmmaker’s last statement on her career. Prepared during her final years of life and produced by her daughter Rosalie Varda, it’s a poignant and revealing account of what mattered to her in her work. It showed Varda’s wry, playful humor and her commitment to treating social issues in intimate human terms. It’s a body of cinema that grows ever more important each year.

Varda par Agnès also showed her characteristic sensitivity to overall form. It’s framed by bits of her talking to audiences in master classes, so she becomes the narrator. Some stretches are chronological, going film by film, but just as often the links are associational. The women of Black Panthers (1968) remind her of the abortion activists of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977). That’s about the friendship of two women, which suggests by contrast a film about a woman alone, Vagabond (1985). The beach of Vagabond summons up the plenitude of Le Bonheur (1965). And so on.

This might seem rambling, but it’s not. Varda explains that she often conceives her films with a strict structure–the strung-together tracking shots of Vagabond, the tight time frame and spatial coordinates of Cleo from 5 to 7 (1962). Varda par Agnès splits about halfway through, flashing back to Varda’s early still photography and adroitly linking that to her emergence as a “visual artist.”

She began mounting expositions like L’Îl et Elle, which housed cinema cabins (big transparent cubes made of ribbons of 35mm film) and Widows of Noirmoutier. Around a central image of collective grief, small screens show women sharing the everyday details of life without a partner. In just this clip, it’s almost unbearably touching. Apart from the resonance with Varda’s devotion to Jacques Demy, I was reminded of Chekhov’s line: “If you’re afraid of loneliness, don’t get married.”

We’ve been so busy with films, and queueing for films, that we’ve had little time to blog about our visit. Later entries will have to come after we’ve left Cinema Ritrovato.

Thanks as usual to the Cinema Ritrovato Directors: Cecilia Cenciarelli, Gian Luca Farinelli, Ehsan Khoshbakht, Marianne Lewinsky, and their colleagues. Special thanks to Guy Borlée, the Festival Coordinator.

The complete score for Song of the Scarlet Flower is available on CD and streaming.

For Varda’s last visit to Cinema Ritrovato, go here. We discuss Varda’s career and Kelley Conway’s in-depth study of it here. See also Kelley on Varda at Cannes. A forthcoming installment of our Criterion Channel series is devoted to Vagabond.

For more on the stylistics of 1910s films, see the category Tableau Staging. I discuss The President in the Danish Film Institute essay, “The Dreyer Generation.”

The Criterion Collection’s magnificent Bergman collection wins Best Boxed Set at the annual DVD awards, Cinema Ritrovato 2019. Congratulations to producer Abbey Lustgarten and all her colleagues!

Cine-Vienna

The Third Man (1949).

DB here:

En route to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato, Kristin and I paid a visit to this wonderful city. We wandered around, stomped through museums, ate tasty food, and saw a bit of the city’s film culture.

Visiting venues

Our first stop was the Austrian Film Museum. Founded in 1964 by the avant-garde filmmaker Peter Kubelka, the Museum has built up a collection of over 30,000 films. It contains a fine film theatre with features of the “Invisible Cinema” (above) that Kubelka and Jonas Mekas set up in Anthology Film Archive many years ago.

The Museum has been a pioneer in producing outstanding books and DVD editions devoted to an eclectic array of filmmakers (James Benning, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Straub/Huillet, Joe Dante). Exceptional as well are the Museum’s online offerings of films, clips, images, and paper documents.

Our host was our old friend, the ebullient curator Christoph Huber. Here he is with his colleagues Alexandra Thiele and Jurij Meden.

We didn’t have a chance to visit the classic Stadtkino in the same neighborhood, nor did we check out the highly esteemed Austrian Film Archive. But I did mosey down to the Gartenbaukino, a big, beautiful modernistic venue.

Built as a ballroom that occasionally screened films, the Gartenbau was made a permanent cinema in 1919. In 1960, after being redesigned by Robert Kotas, it opened as a showcase for widescreen motion pictures.

It’s now said to be the biggest theatre in Austria, with over 700 seats. Note the rising curtain, said to be a rarity these days.

The Gartenbaukino is equipped to project not only digital and 35mm but also 70mm. Managing Director Norman Shetler notes that it was the first Austrian theatre to boast large-format projection (for Spartacus) and was adapted for Cinerama as well.

More recently, the Gartenbau reactivated its 70mm equipment to show The Hateful Eight. The Phillips DP70 projectors now screen wide-gauge classics like Lawrence of Arabia and The Sound of Music. Picture and sound were excellent for The Dead Don’t Die, so I bet 70mm shows here are fantastic. Like the Stadtkino, the Austrian Film Archive, and the Film Museum, the Gartenbau is a venue for the city’s annual film festival, the Viennale.

Prater, not so violet

Plenty of movies have been set in Vienna, most notably The Joyless Street, Merry-Go-Round, Letter from an Unknown Women, and Amadeus. But for movie nerds the most flagrant example is The Third Man (1949). And Vienna hasn’t forgotten what this movie did for its local landscape, not least the amusement park set within the vast and beautiful park known as the Prater.

Said to be the oldest amusement park in the world, the Prater ‘s entertainment sector contains attractions that are shiny and enjoyable old-school rides: roller coaster, loop-the-loop, tilt-a-whirl, haunted house. There are shooting galleries, ice-cream stands, and even a Madame Tussaud’s.

But of course the looming attraction is the great Ferris wheel that Holly Martins (Joseph Cotten) and Harry Lime (Orson Welles) share during their ominous reunion. I’m sure I’m not the only viewer who always expects Harry to try to throw his old friend out of the cabin.

The big wheel has been declared a site of European film culture and decorated with a more or less accurate image of the coy Lime.

My ride in the wagon was gentle and elating. I tried to replicate Harry’s POV on the “ants” below, whose lives, he says, can’t matter much.

A studio-based version of the Prater featured in the now mostly lost Josef von Sternberg film, The Case of Lena Smith (1929).

Oh, yeah–we also paid a visit to a street named for one of my favorite auteurs. See below.

Next up: Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato!

For information about Viennese film culture, thanks to Christoph Huber, his colleagues, and the indefatigable Ted Fendt. Thanks as well to Norman Shetler and two staff members at the Gartenbau cinema. Christoph, by the way, is an exceptional critic. You’ll learn from reading his essays in Cinema Scope.

Cognitive film studies: The Hamburg Variations

Lobby, Von-Melle-Park 9, Universität Hamburg, with Murray Smith.

DB here:

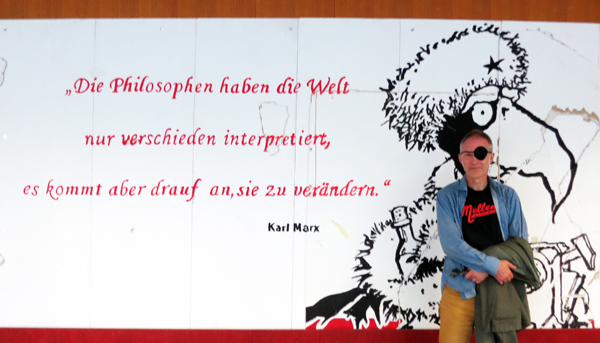

How many universities in the US would post a big quotation from Karl Marx in the lobby of a classroom building? (Answer: None.) But a cartoonish rendition of Marx’s killer app–the task of philosophy being not only to understand the world but also to change it–greeted the one hundred or so scholars attending the latest conference of the Society for Cognitive Studies of the Moving Image last week at the Universität Hamburg.

How much we’ll change the world remains to be seen. What is clear now is that thanks to the superb organization of Kathrin Fahlenbach, Maike S. Reinerth, and their team, the SCSMI had a lively four days of papers, discussions, and excursions–as well as a screening of a strong film by a skillful director previously unknown to me. In all, every good reason to go to a conference.

Big questions, candidate answers

Carl Plantinga, Dirk Eitzen, and Kathrin Fahlenbach on the Hamburg Harbor cruise.

The range was huge, as usual, because this is a very diverse group. Our community, as I’ve mentioned in earlier reports, hosts film scholars, scholars of other media (television, games, internet), psychologists, and philosophers. Recurring questions include: How do viewers comprehend media presentations? What is the role of morality in film and television? How do practitioners conceive their craft? How do media present and trigger emotions? What appeals are specific to certain genres or historical periods? Not least: How may we construct good theories to answer such questions?

Three sessions ran simultaneously at each time slot, so I missed many good presentations. Kristin and I occasionally doubled up. Many of the talks will eventually become published papers, several in the Society’s journal Projections, so let me just highlight a few strands.

For those of us interested in how style interacts with narrative, there were several significant presentations. James Cutting, who has pioneered the use of Big Data techniques in scanning large batches of films, provided a compact account of how “sequences” (as opposed to scenes) displayed patterns of coherence and grouping. Karen Pearlman discussed her films, and James examined them to reveal fractal patterns in their rhythms–patterns that match the dynamics of footsteps, heartbeats, and breathing.

Two papers added to our understanding of the Kuleshov effect, much discussed on this site. Marta Calbi and her collaborators conducted EEG testing on spectators exposed to a Kuleshovian film scene, while Anna Kolesnikov, another member of the team, traced the contradictory versions of the “experiments” that Kuleshov and his students purportedly constructed. Both were exciting contributions to our understanding of Kuleshov’s legacy, which as the years go by looks more complex than we had thought.

Other papers on visual style included Barbara Flückiger’s tour of the staggering resource she and her colleagues have devoted to the history of color in film–a database of images from 400 films illustrating a range of technologies, periods, and genres. She has also mounted a magnificent array of tools for detailed analysis of color. (Significantly, she has taken the images from film prints, not video copies.) Here’s one of several stunning images she has taken from Helmut Käutner’s Grosse Freiheit Nr. 7 (1944, Agfa nitrate).

Stephen Prince, whose book Digital Cinema has just been published, surveyed the emergence of “deep fakes,” manipulated images that have no basis in reality but which are indiscernible from an accurate image. Steve was once skeptical that digital images would ever cut us off entirely from photographic reality, but now machine learning has managed to do it. Sped up by social media, the rise of unverifiable “records” creates what he called “an attack on an information system we call society.”

Hitchcock, everybody’s idea of a shrewd filmmaker (when will cognitivists discover Lang?), came in for his usual close treatment. Todd Berliner proposed five ways in which story information can be set up and paid off in a narrative, and he used Psycho as an instance of at least four of those methods. Maria Belodubrovskaya countered Hitchcock’s constant claim that he relied on suspense and not surprise. She showed that both single sequences and overall plots (e.g., Suspicion, Psycho) were heavily dependent on surprise effects.

In the first day, the range of the “humanistic” side of SCSMI was on vivid display. Malcolm Turvey asked whether the give and take of philosophers’ arguments converged on a consensus about truth, the way that much of science progresses. To illustrate the process, he considered the return of an “illusion” theory of images put forth by Robert Hopkins. Later that day, Jeff Smith used the cognitive theory of confirmation bias to show how characters in Spike Lee’s Clockers systematically misunderstand the story situation. The result, enhanced by genre conventions and a violation of some traditions of the detective story, enmeshes the viewer in the same error.

On the other end of the spectrum, there were papers mobilizing empirical research. Timothy Justus drew upon Lisa Feldman’s work in How Emotions Are Made to suggest that a biocultural account of facial expression should not rely too strongly on Paul Ekman’s classic argument about universal, basic expressions. More room, Justus proposed, should be given to cultural forces that build “emotion concepts” that filmmakers and viewers draw on.

A more hands-on empirical project was that coming from a team at Aarhus university. Jens Kjeldgaard-Christiansen posed the question: What if sympathy for a film’s villain varies with the personality of the spectator? As he put it, “If you are like a villain, will you like a villain?” So via Amazon’s Mechanical Turk the team ran questionnaires testing how personality types matched tastes in villains. Not to spoil their public announcement, I’ll just say that the results seem to confirm the belief that the most dangerous creatures on earth are young human males.

There was a lot more here than I can report, including provocative keynote addresses from Professors Anne Bartsch and Cornelia Müller (presenting work done with Hermann Kappelhoff). There was also a moving tribute to Torben Grodal, a central force in SCSMI and a leading-edge theorist applying evolutionary psychology and embodiment theory to traditional genre studies.

And, since SCSMI wants to understand how creators create, there was a film and its maker.

Without bullshit

In the past, our conferences have featured Lars von Trier and Béla Tarr, talking with us about their work. This time the guest was Thomas Arslan, a prominent “Berlin-school” director, who brought his 2010 film In the Shadows (Im Schatten) to the lovely Cinema Metropolis.

The film is a dry, hard-edged crime exercise. Trojan, fresh out of prison, comes to his boss to claim his share of the loot. In a tense confrontation he manages to get some of what he’s owed, but he’s now a target for elimination. He searches for a new robbery scheme and settles on the heist of an armored car. As usual, things don’t go as planned, particularly due to the intervention of a crooked cop.

Shot in a laconic style, In the Shadows took advantage of the Red One camera to produce remarkable depth in dark surroundings. (We saw it as a print because in 2010 theatres weren’t quite ready to show digital files. The print looked fine.) The drab locations complemented the anti-psychological impact of the story. Characters barely speak, the music is spare and almost subliminal, and the framing doesn’t accentuate the action expressively. In his post-film discussion, Arslan explained that the style grew out of the small budget and the rapid schedule. The result was a sort of modern B-film, avoiding the excess of CinemaScope and explosive chase sequences.

Arslan refuses to glamorize his gangsters, but he summons up sympathy for Trojan by minimal means. The protagonist is a solid, efficient professional, and he’s loyal to his boss until he realizes he’ll be betrayed. And as Hollywood screenwriters would remind us, you can sympathize with someone who’s been treated unfairly. I liked the unfussy handling of the story; it was a bit reminiscent of Rudolf Thome’s bare-bones Detective (1968). Arslan would be a good director to shoot a Richard Stark noir. “He does it without bullshit,” Arslan said of his thieving protagonist. It’s a good description of Arslan’s own technique.

SCSMI continues its tradition of merging humanistic inquiry with findings from empirical science. We can fruitfully ask questions that cut across traditional boundaries if we ground those questions in clear concepts and solid evidence. Our gathering next year moves back to the States–Grand Rapids, no less. More fun on the way.

Go here for earlier years’ coverage of SCSMI conferences.

On Richard Stark noir novels, see here and here. In the Shadows would fit nicely into my discussion of conventions of the heist film.

My own SCSMI contributions were two: a tribute to Torben Grodal and a little talk on contemporary women’s domestic thrillers (Gone Girl, The Girl on the Train, etc.). I may post the latter as a video lecture later this summer.

James Cutting lecturing at the SCSMI conference.

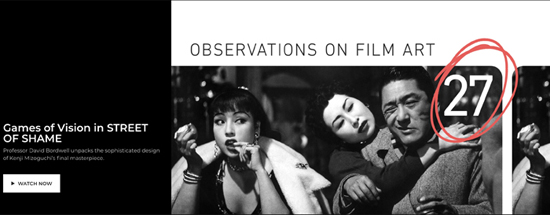

How to hypnotize the viewer: Mizoguchi’s STREET OF SHAME on the Criterion Channel

Street of Shame (1956).

Filmmakers must study the film image and its potential for expression. This is our primary responsibility.

Kenji Mizoguchi

DB here:

So much of contemporary film and TV takes pictorial space for granted. Yes, The Avengers: Endgame stuffs its frame with, well, stuff, but you’re seldom given time to see everything. Even in films not so dominated by CGI, if the the actors’ faces and gestures come across and you can hear the line readings, that’s pretty much enough. Most of the rest is there to fill out the very wide frame.

“Wait,” I hear someone saying. “Thanks to Steadicam, directors use camera movements to sweep through space all the time.” Yeah, that’s just my point: They sweep through. We’re following characters’ backs or fronts, not exploring space as such. Very seldom do we get a chance to probe what’s revealed, except in carefully wrought movies like Sunset (which tease you into trying to discern what’s not even in focus).

Moreover, today the pace of the editing is so fast, even in an “intimate” movie like Booksmart, that the actors’ faces dominate everything. For fifty years many directors have been “shooting for the box,” shoving their actors into close-ups that will read on TV, now on computers and smartphones. Like the endlessly moving camera, the big heads and the quick cuts refresh the image often enough to hold our interest in a distracting environment.

Granted, most filmmakers now supplement their fast-cut, rapid-pan close-ups with an occasional landscape shot that can look pretty, in a calendar-image sort of way. Overhead shots, now facilitated by drones, swoop us through the towering corridors of The City or across a swath of forest in a way that is undeniably impressive. This convention doesn’t count, for me, as pictorial intelligence unless somebody like Tony Scott does something, however nutty, with it.

I’m not against these stylistic choices per se; every style is valid if it’s pursued with imagination, rigor, and delicacy. Nor am I suggesting that the other extreme, so-called slow cinema, is inherently more virtuous. Long unmoving takes can be paralyzingly dull. Ozu made fast cutting just as “contemplative” as Hou or Tarr, because he knew how to design pictures.

It’s just that the norms of intensified continuity and the “free camera” have overwhelmingly dominated current practice. It’s worth remembering other ways moving pictures can be. One way to do that is to revisit film history, and the work of Mizoguchi Kenji is an ideal place to start.

His Street of Shame (1956) is the subject of this month’s Observations entry on the Criterion Channel. In it, I invite you to join me in attending a master class in staging.

The theme is Mizoguchi’s perennial one, that of the ways in which women succumb to or resist their oppression in a patriarchal society. We’re in the Dreamland brothel, where five–eventually, six–women are working at the very moment the government debates eliminating prostitution. Mizoguchi shows how they both cooperate and compete, trying to quit, deploying different strategies for managing their clients, and just getting by. It’s all done through what Mizoguchi called the “hypnotic power” of carefully choreographed images.

A personal note

In a way, Mizoguchi made me a film teacher.

During the week of 25 September 1969, what could you have have seen in Manhattan? I Am Curious: Yellow, La Chinoise, Closely Watched Trains, Miracle in Milan, Hell’s Angels ’69, Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Midnight Cowboy, The Killing of Sister George, De Sade, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, One Second in Montreal, <—->, Take the Money and Run, Alice’s Restaurant, Medium Cool, In the Year of the Pig, Easy Rider, Putney Swope, and programs of Kubelka and Jack Smith movies. There were many double bills on offer: The Wild Bunch and Ride the High Country, Yellow Submarine and The Gold Rush, King Kong and The Lady Vanishes, Seven Samurai and The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail, Monterey Pop and Don’t Look Back, The Deadly Affair and Funeral in Berlin, Little Sister and Alice in Acidland, Lonesome Cowboys and Flesh.

Yeah, those were the days before cable TV, home video, and streaming.

Yeah, those were the days before cable TV, home video, and streaming.

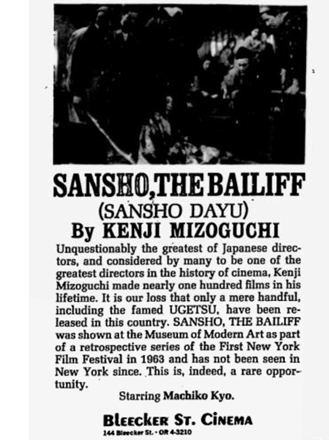

In the city for only a few hours, I didn’t go to any of those shows. There was yet another double bill at the Bleecker but I could catch only one title: not Lola Montès (I would see that in Paris a year later), but Mizoguchi’s Sansho the Bailiff.

As a teenager I had read books about cinema (Welles, Hitchcock) and in college I’d written movie reviews and participated in a film club. Now, newly graduated, I was teaching high school. The only Japanese films I’d seen were the Kurosawa standards our club programmed. Despite planning for a career in high-school teaching, I thought about film most of the time. In the pages of Film Culture and Movie I had read about Mizoguchi.

I came out of Sansho with tears streaming down my cheeks. I heard two young men in the lobby talking about the film. Did they go to NYU or Columbia or some such place? All I know was that they loved Mizoguchi’s long takes, as I did. Somehow, those takes had to be connected to the way the movie hit me. I thought something like: I’d like to study this sort of thing.

I returned to my apartment and began figuring out how to apply to graduate school.

Mizoguchi was still largely unknown, certainly unappreciated. The New York Times didn’t get around to reviewing Sansho until it resurfaced in a later run. Roger Greenspun made up for the neglect with a a gracious note.

“The Bailiff” is a film of breathtaking visual beauty, but the conditions of that beauty also change–from the etheral delicacy of its beginning (before the kidnapping), through the dark masses of the Bailiff’s compound, to the ordered perspectives of Kyoto and the governor’s palace, and finally to the spare symbolic horizons at the end.

In effect, it moves from easy poetry to difficult poetry. Its impulses, which are profound but not transcendental, follow an esthetic program that is also a moral progression, and that emerges, with supreme lucidity, only from the greatest art.

People talked that way then, with good reason.

Choreography all the way down

I didn’t see much Mizoguchi in the years following. There wasn’t much available. (And Ozu was unknown to us.) I did see Ugetsu and Street of Shame, though they didn’t grab me as fast as Sansho had. Fairly soon, though, New Yorker Films and Audio-Brandon made prints of other Mizoguchi titles available. I started using Mizoguchi films in my teaching, and the more I studied them the more I admired them. I was also inspired by critics Robin Wood and Noël Burch, who sought to explain the emotional and cinematic force of this filmmaker.

I began studying Mizoguchi’s films, traveling to Europe to see them all and make frames from prints. Eventually that work would inform my chapter on his staging in Figures Traced in Light. Although there he bested me two falls out of three, I think that discussion made some headway in analyzing his unique visual strategies. I tried to develop those ideas further in an online supplement to that chapter and in the blog entries “Secrets of the Exquisite Image” and “Sleeves.”

More skilfully and subtly than nearly anybody else, Mizoguchi arranges bodies in space to create powerful pictures. Yet his gorgeous shots aren’t just decoration. He never lets the images, elegant as they are, distract from the dramatic issues arising among the characters. The result, I argue, achieves the sort of “hypnotic power” that Mizoguchi claimed to seek.

In Mizoguchi, I suggest, a fairly dense image “becomes a story” as its elements start to mingle and separate out, letting our eye discover (with guidance) a drama as it emerges. A situation precipitates out of a rich mass of material, and the result is an accumulating tension that’s at once dramatic and pictorial. He evidently learned a lot from von Sternberg, but I think this thickening-and-release dynamic of story and style is reminiscent of Hitchcock or Lang as well.

The students were right: Mizoguchi is a master of the long take. The long take, he said, “allows me to work all the spectator’s perceptual capacities to the utmost.”

But we shouldn’t think of this technique in the sort of marathon-competition terms people apply to long takes nowadays. (The current example is Bi Gan’s Long Day’s Journey into Night.) Today’s long takes are often virtuoso traveling shots. While Mizo made wonderful use of camera movement, he knew the power of stillness. He showed that you can just clamp the camera on the tripod (or the crane) and sculpt the action in front of it.

Among Mizoguchians, there are some who find his later films stylistically compromised. Genroku Chushingura (1941-1942; below) and Loves of the Actress Sumako (1947), with their far-off figures and impeccable, “all-over” compositions, merge austerity and density in ways almost inconceivable today.

Given this radical approach, his greater reliance on closer views in the 1950s work can seem a step backward.

But Mizoguchi was a pluralistic director from his earliest days forward. As I try to show in Figures, he fitted his visual design to the needs of a scene, and even the most severe films draw on diverse techniques. Street of Shame shows his endless resourcefulness in enriching three-shots and two-shots and singles. He found choreographic possibilities at every shot scale, with small gestures and glances becoming as important as characters shifting around the set. In the last shot of the last film he made, a single darting eye commands the image and carries the drama.

Given the sustained shot, Mizoguchi fills it and drains it, re-fills it and thins it out and channels it to a climax, all with a graceful, unobtrusive choreography always driven by the emotions pulsing through the scene. I go back constantly to Philippe Demonsablon: “He emits a note so pure that the slightest variation becomes expressive.”

Mizoguchi works in melodrama. Some directors, such as Sirk, take intense situations and amp them up. But Mizoguchi, like Stahl and Preminger, is always banking the fires. His style presents hot emotions in a cool way, betting that detachment and restraint give the emotions a sort of stark purity. If more filmmakers studied his work, who knows what kind of cinema we might have? I hope you have a chance to check in on this entry.

We’re grateful as usual to Peter Becker, Kim Hendrickson, Grant Delin, and the whole fine Criterion team, and to Erik Gunneson of the UW Department of Communication Arts.

Street of Shame is also available on a generous Criterion Eclipse DVD set. Some years back Masters of Cinema series gave us beautiful Blu-ray transfers of many Mizoguchi films. The Street of Shame edition has a fine feature-length audio commentary by Tony Rayns. Alas, the set including the film has apparently gone out of print.

Robin Wood’s influential essay on Mizoguchi is “The Ghost Princess and the Seaweed Gatherer,” in Personal Views: Explorations in Film (Gordon Fraser, 1976), 224-248. Noël Burch’s revisionist account of Japanese cinema is To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in Japanese Cinema (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979), where chapter 20 is devoted to Mizoguchi. (The book is available online here.) Roger Greenspun’s review, “‘Bailiff’ Returns,” appeared in the New York Times (17 December 1969), 61.

For more on the place of Japanese directors in film culture, you can try this entry on Kurosawa and this one on Shimizu.

Street of Shame (1956). The sign reads “Cooperative Association Members” and “Confidential Membership.” Thanks to Steve Ridgely for the translation.