Dispatch from another 35mm outpost. With cats.

Friday | March 14, 2014 open printable version

open printable version

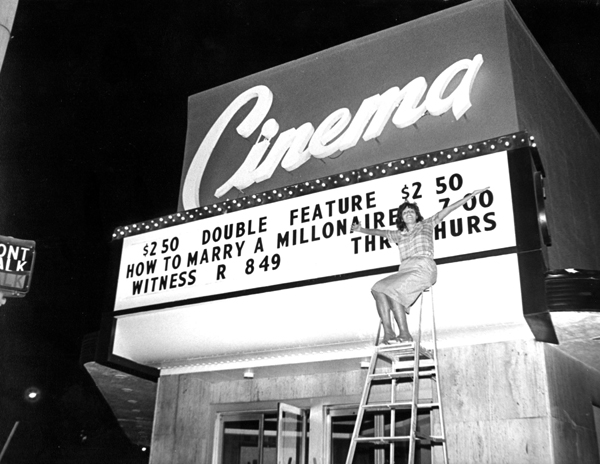

Cinema Theater, 1985, with JoAnn Morreale.

DB here:

For a while now I’ve been tracking the consolidation of digital cinema. After a blog series, I melded the entries with other information and created the e-book Pandora’s Digital Box. (To the readers who bought it, thanks!) Last year, in a blog called “End Times” I updated the information. Now we’re at post-End Times, I suppose.

David Hancock, who keeps meticulous account of these things, issued an IHS Technology Profile report on the state of things at end 2013.

*Of the world’s nearly 129,000 screens, over 112, 000, or 87%, are digital in some format. Most screens are compliant with the Digital Cinema Initiative standard used in the US, but India has pioneered the cheaper “electronic cinema” formats. Many of these e-screens will upgrade to the DCI standard.

*The UK and France have fully converted, along with most smaller European countries. Those countries benefited from various degrees of government support for the conversion.

*China now contains over half of the 32,642 digital screens in Asia.

*High concentrations of 35mm venues remain in Egypt, Morocco, Greece, Portugal, Ireland, and other areas with economic troubles. Other analog countries, such as Slovakia and Slovenia, lack public funding and contain mostly single-screen venues. The more multiplexes a country has, the greater the pressure to go DCI.

*In North America, out of about 40,000 screens, close to 93% have converted. That leaves about 3200 analog venues. It’s hard to know how many of those have closed or will close soon.

Most of the surviving analog sites, I suspect, are subsequent-run, like the five 35mm screens at our Landmark/Silver Cinemas ‘plex. And our Cinematheque and student-run Marquee continue to find and show excellent film prints. But clearly the moving finger has written. We at the University are striving for funding to make the changeover.

So too is a wonderful cinema I visited back in January. A family trip carried me back to my stomping grounds in New York’s Finger Lakes. I’ve already retailed some information about my hometown cinema, and a 1915 film that was discovered there. For now, let me tell you about a theatre I visited during a few days in Rochester.

Let George do it

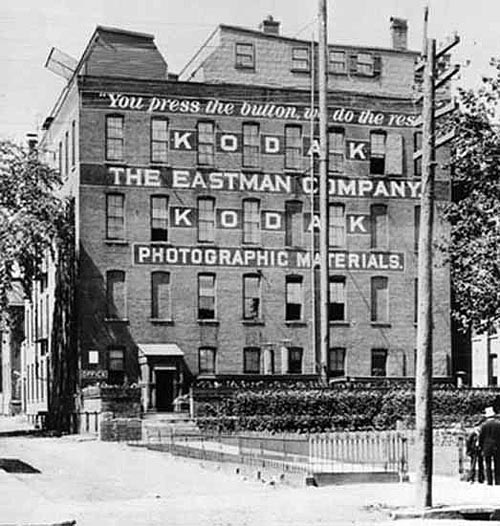

Eastman Company, 1892.

Before there was Hollywood film production there was New York film production. Before that, there was West Orange, New Jersey, where Mr. Edison and Mr. Dickson devised a movie machine. And somewhat before that, before movies themselves, there was Rochester.

Rochester was the home of the George Eastman company, founded in 1880. Eastman pioneered consumer still photography; he made up the word “kodak” to suggest the click of the shutter button. The company manufactured the flexible 35m film stock that formed the basis of the American cinema industry. Another Rochester industry, the venerable Bausch & Lomb provided camera and projector lenses, including those for CinemaScope in the 1950s.

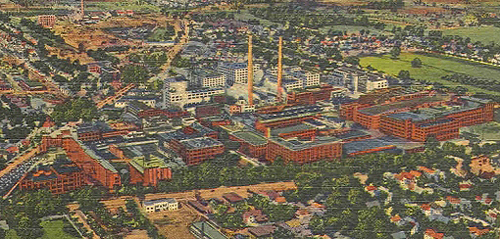

I suppose most people under thirty have never used a film-based camera, and for them the firm’s cheery yellow-and-red logo looks the way an ad for Packards looked to me in my teen years. Throughout most of the twentieth century, though, Eastman Kodak was one of America’s great technology firms. Here’s the Kodak Park facility ca. 1940.

The firm’s tragic decline will eventually get book-length treatments, but a short version is here.

Despite having invented the first digital camera, Kodak was overwhelmed by faster-moving competitors in that realm. As the firm mounted huge losses, the CEO, Antonio Perez, sought to leverage cash through Kodak’s many patents, but that tactic couldn’t stave off disaster. By 2011 Kodak stock was selling at about $1, down from the $25 it had been at when Perez arrived. In the same year, he was appointed to President Obama’s Council on Jobs and Competitiveness. Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the following year.

Kodak has tried to reinvent itself, but its collapse has damaged Rochester badly. Growing up, I encountered in Kodak a supreme example of paternalistic capitalism; George Eastman even paid for dental care for all of Rochester’s children. In the 1980s over 60,000 people in Rochester worked at the firm; now fewer than 7,000 do. As the company imploded, its pension funds fell behind. During my stay I met former employees who had counted on a secure retirement and are now struggling to make ends meet. There were also plenty of salty epithets aimed at Perez, who is said to receive an annual salary of over $1 million, along with millions more in other compensation.

Some argue that Rochester as a whole is recovering. If so, it’s a slow climb.

Still, for cinephiles, Rochester remains a remarkable city. There is the historic Little Theater. It’s one of the oldest art houses in the country and now has several screens, all but one of them digital. The theatre has been taken over by the local NPR outlet and presents indie and foreign titles, along with some live music events. There’s also the magnificent Dryden Theatre operating under the auspices of the George Eastman House, one of the world’s great archives. Its programming has always been stellar, and it continues to bring rare films to the city.

Then there’s a real survivor: the Cinema Theater.

The South Wedge upstart

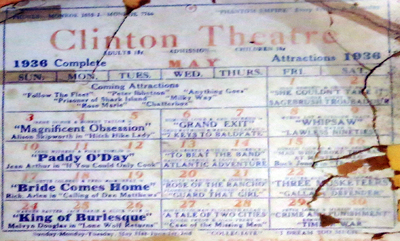

The Clinton Theatre, mid-1930s. The features are In Old Kentucky (1935) and The Return of Peter Grimm (1935).

It opened in 1914, smack in that period when motion pictures became the movies. It was initially called the Clinton Theatre because it occupies the corner of South Clinton Avenue and South Goodman Street. It offered minimal comforts. Donovan A. Shilling, in his colorful and nostalgic Rochester’s Movie Mania, tells of wooden benches and a dirt floor.

Those amenities couldn’t easily compete with the offerings of the Clinton’s more splendid rivals.

There was, for instance, the Piccadilly, opened in 1916. Advertised as a million-dollar house, the Piccadilly was built with a grand stairway and an orchestra pit for a sixteen-piece ensemble. Its auditorium could seat 1500 people in what the trade press announced as exceptionally comfortable seats. A beautiful exterior photo is here. Eventually the Piccadilly became the Paramount. Rochester was a pretty rich city then.

The Clinton closed in 1916, reopened briefly, closed again, and reopened in 1918. This time it held on. Located outside the central theatre district, in a neighborhood known as South Wedge or Swillburgh, the Clinton was a classic neighborhood second-run house. You might have to wait quite a while to see a release, which would play the downtown theatres first. But at least you benefited from a swift turnover. During one week of February 1929, you could see The Big Killing and Bachelor’s Paradise (on a double bill), Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Tim McCoy in Wyoming, The Crowd, and While the City Sleeps, starring Lon Chaney. These titles had been released in spring and early fall of the previous year.

The Clinton wasn’t part of a chain, but it hung on through Hollywood’s biggest studio years. In 1934 it was one of thirty-two Rochester theatres, some of them huge. The Century could hold 2500 people, the RKO Palace 3000. (Of course many such theatres hosted live shows as well.) With capacity of only 500 (about the same as the Little), the Clinton was in the same category as the Aster, the Broad, the Empress, the Hudson, the Lyric, the Majestic, and the Rexy. Admission was typically $.15, and that usually got you two pictures. Bills changed three times a week, with the big pictures running three days.

Surprisingly by our standards, the major films weren’t playing Friday and Saturday. I can’t prove this, but I’ve read that Sunday afternoons and evenings yielded the big audiences for neighborhood theatres–possibly because many people worked six-day weeks. (See the codicil for more information.)

But, as mentioned in an earlier entry, the late 1940s were problematic for exhibitors because attendance plummeted. In 1949, the Clinton was taken over by Jo-Mor Enterprises, a major Rochester chain. Renovated with the Art Deco façade it now has, the newly named Cinema played arthouse fare as well as subsequent-run Hollywood films.

The Cinema was headed for closure in the mid-1980s when it was saved by an unlikely heroine. Earth Science teacher JoAnn Morreale bought it and spent over $100,000 in improvements. She did everything from negotiating with distributors to cleaning toilets.

Her energy made the theatre what it had been in its heyday, a center for community activity. Locals came in with gifts and home-made treats. Some spent the day there, watching the double-feature matinee and the double-feature evening show. Six bucks got you four movies. Here’s the old beauty in 1992.

Two years ago the Cinema was bought by John Trickey. The house is still a second-run venue, but unlike most it still offers double bills. The night I visited with my sister Diane you could have seen Mandela and Gravity in one go. The prices have gone up only a little since the 1980s: $5 for adults, $3 for seniors, students, and kids under 12.

We met the Cinema’s majordomo Benjamin Tucker. By day Ben is a Curatorial Assistant at Eastman House, but he loves film history and is happy to help out the theatre.

The shows are still in 35mm, although Ben is coordinating a crowdfunding campaign to help out digital conversion.

Princesses

We met the staff, including the projectionists and the ticket lady Pat Russo, who has worked there for about ten years. She gives you real pasteboard tickets, not those flimsy, curly multiplex printouts.

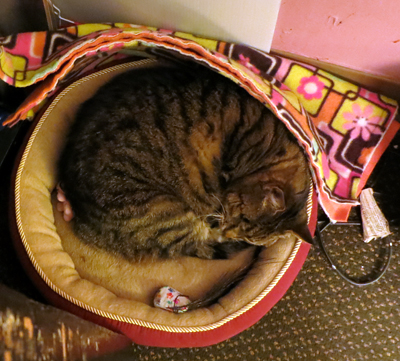

And there’s the proud lineage of Cinema Theater cats, starting with Princess to Princess the second (ruling for about fifteen years) up to Sue, who’s been in residence about six months.

The Princesses would circulate among the seats, startling patrons by rubbing up against their legs or leaping onto their laps. Sue has a habit of settling down for a snooze in the middle of the line at the concession stand, forcing customers to step over her on their way to the popcorn.

I never visited the Cinema in my salad days (the 1960s). It wasn’t playing so much arthouse fare, I think, so I tended to visit the Little or the Dryden. I wish I had sought out the Cinema. This is one of the oldest continuously operating theatres in the country. Long may it flourish.

Thanks to Ben Tucker for information and images, to Jim Healy for tipping me off to the theatre, and to Diane and Darlene Bordwell for their company.

The image of the mid-1930s Clinton comes from Shilling’s Rochester’s Movie Mania; Carl Baxter supplied the original photo. More Clinton/Cinema Theatre memories here. The Rochester Subway site hosts stupendous, recently discovered photos of the RKO and Loew’s picture palaces.

PS 16 March 2014: Alert reader Andrea Comiskey supplies some background on the Clinton’s scheduling three programs per week during the classic years.

Mae Huettig (Economic Control of the Motion Picture Industry, 1944) says that only theaters that did not have to block-book (majors’ affiliates, members of large chains, etc.) got to choose films’ playdates. Whether this was really as absolute as she makes it sound, who knows? But what this means for when the “best films” (typically the A pictures) would tend to appear is tough to determine. On the one hand, you could imagine that distributors would want the strongest, most appealing films showing on the weekends when they could bring in the biggest crowds. On the other hand, you could imagine distributors trying to force underperforming/weaker films onto bills on the busier days since there’d be higher baseline business regardless of the merits of the films on the program. Exhibitors that didn’t get to pick playdates certainly did complain.

In an interview published in Kings of the B’s, (1975) Monogram’s Steve Broidy says that Saturday is the busiest day, at least for small-town exhibs. He also says that these exhibs liked flat-rate rentals on Saturdays so they could run up the profits and echoes the idea that the particular film didn’t matter a ton since people were going out to the movies regardless.

As was the case with your Rochester example, theaters that changed programs 2 or more times a week (which, at least in big cities, were more likely to be sub-run houses) often split the weekend days across two programs, with many theaters adding an extra feature exclusively for the Saturday kiddie matinee. I’ve seen just about every possible permutation, but for a twice-weekly changeover, Sun-Wed & Thurs-Sat was a pretty common pattern. For thrice-weekly, Sun-Tues, Wed-Thurs, & Fri-Sat was common. But I’ve also got plenty of examples of theaters that showed the same program Sat. & Sun.

Andrea is writing a dissertation about distribution and playdate patterns in the 1930s. I’m happy to get her clarification here, which shows, as usual, that film history is always more complicated than it seems at first.

The Cinema, 2014. Photograph by Darlene Bordwell.