Archive for April 2012

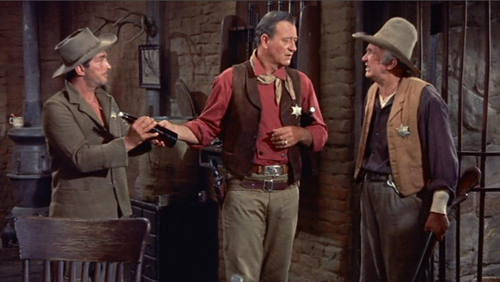

The Tao of RIO BRAVO; or, A Yakky Way of Knowledge

Too long has this scrolling site ignored the Sacred Text. In a gesture of penance, I return to the true path. Like all Sacred Texts, this one attracts worshippers in different degrees: the Seekers, the Initiates, the Adepts, and the Exegetes. There are Heretics too. Today, I wish merely to introduce you, who may not yet be even a Seeker, to the serenity of The Way.

The Word, in plenty

Seekers who have become Initiates agree: Their blinding moment of conversion came when they realized that the words of the Sacred Text speak to all times, all places.

Other Sacred Texts dispense a few trinkets of wisdom (“I have a bad feeling about this.” “We’re gonna need a bigger boat.” “Show me the money.”) These are tag lines, sound bites, not poetic glimpses of glory. Uniquely and universally, passages in our Text raise the spirit and cast out doubt and despair. But far from being otherworldly, they carry practical wisdom and illuminate every situation. What crisis in your life, brother or sister, would not be piercingly clarified if you were able to utter one of these lines?

It’s nice to see a smart kid for a change.

I’d say he’s so good he doesn’t feel he has to prove it.

That’s what I’d do if I were the kind of girl you think I am.

Sorry don’t get it done, Dude.

You look a little used.

Aw, I’m not gonna hurt him.

If I’m gonna get shot at, I might as well get paid for it.

Let’s take a turn around the town.

I’m glad we tried it a second time. It’s better when two people do it.

Borachone talking big.

You’d better go easy on that stuff.

Don’t set yourself up as being so special. You’d think you invented the hangover.

Aw, hell, what’s the difference? We’d all be dead by then.

Nobody’s run in here./ We’ll remember you said that.

Found yourself another knot-head who don’t know when he’s well off?

A game-legged old man and a drunk. That’s all you got?/ It’s what I’ve got.

Think you’re good enough?

Is he as good as I used to be?/ It’d be pretty close. I’d hate to have to live on the difference.

To become an Initiate, the Seeker must commit these to memory and meditate upon them intently. An Adept will be able to summon them up, half-consciously, in a range of situations–the more far-fetched, the more enlightening. One will always be appropriate.

The Name

Exegetes have pointed out that the figures of light in the Sacred Text do not have the usual names. They are, emblematically, called Stumpy, Dude (aka Borachone), Colorado, Feathers. He Who Is Called Chance is named John T., but even the middle initial is turned into an epithet (“T for Trouble”).

Far from being an accident, the names in the Sacred Text are there to impel the Initate into deeper mysteries. Is, for instance, Stumpy The Elder called Stumpy because of his lameness—always a sign of grace in sacred texts? Because of his inertness (as stiff as a stump)? Or because a tree, even though harvested, retains its attachment to the earth by remaining rooted? Perhaps He Who Is Called Stumpy is “grounded,” as the current saying has it.

The Text is figural, both metonymic and metaphoric. Young Colorado is son of Rocky Ryan from Denver. He Who Is Called Wheeler is a man of wagons. She Who Is Called Feathers wears feathered clothes, but also has a teasing lightness of manner. He Who Is Called Dude constitutes a crux. Is he a “dude,” an Easterner who has come west, or is he a dude because he favors fancy outfits? (See “Raiment,” below.)

The central fact is that in this text, the mystery of naming opens on to the Mystery of Being. Everyone is named something, but many are not named by their name.

Raiment

Once the devout Seeker has sensed the limitless depths of the The Words, the more inquisitive will turn to the images. In the opening scene of the Sacred Text, a largely wordless series of encounters in barrooms, a world is created before our eyes. It is a world of debasement, treachery, and sudden death. A contemporary text called Variety, secular but still enlightening, notes: “…gets off to one of the fastest slam-bang openings on record.”

Exegetes have long praised this eloquent passage. They note that a text so replete with Words benefits from an extended passage of muteness. Not silence, for the almost continuous music attributed to Dmitri Tiomkin provides its own wordless “commentary” on the action. This sordid, barbarous world will be redeemed; those who are left low on the saloon floor will rise three days afterward (note!) to triumph.

Serious study of the Text’s images drives the Adept to note the raiment in which the figures are clothed. The Nemesis Joe Burdette wears a bright cowhide vest, suggesting his animalistic anima. He Who Is Called Dude begins in dirty garments, earns the right to garb himself in splendor, but through weakness of soul he is once more soiled.

She Who Is Called Feathers manifests the most dazzling changes in raiment.

Hers receive commentary within the Text, while the garments of He Who Is Called Chance are noticed only by her.

Those things have big possibilities, but not for you.

Hey, Sheriff, you forgot your pants.

But these may be interpolations by later hands.

Disputed passages

Like all Sacred Texts, this contains stretches that excite puzzled commentary. What, in the opening scene, is Wheeler supposed to “tell his men”? Why so many flying insects at night? Why is He Who Is Called Chance once, and only once, seen awkwardly grappling with his rifle, trying to hold it while he shrugs into his jacket?

There is the curious verbal slippage in the song sung by He Who Is Called Dude. He sings of “My three good companions—my rifle, pony, and me.” To the heathen mind, this is a flagrant error. You can have a rifle and a pony as a companion, but you can’t have you as your companion. Can you?

To doubt the Sacred Text at this point is to underestimate the subtlety of the Authors. Recall that the tale told by the song is a dream (“It’s time for a cowboy to dream“). As in other venerable texts (e.g., Bible, Ramayana), dreams are to be taken as warnings, prophecies, or hints as to the true meaning of the story. And so it proves here. We know that He Who Is Called Dude is a divided man: Borachone and pistolero, drunk and deputy. The singer, as we’ve seen, has an untamed side that bursts out into violence against nearly everyone, including his Savior, He Who Is Called Chance.

Hence the split identity of the rider in the song. He is a me, but he also has a me. And around the bend, waiting for both of them, is another divided figure, a woman called “my sweetheart darling.”

There are Exegetes who would see in this passage the source of another worthy text, Western Redundancy Playhouse Theatre, but exploring that would take us too far afield.

More obvious is the Text’s great cosmic sign: The sun rises and sets on the same horizon.

No further proof is needed of the miraculous nature of this narrative.

Heresies

I do not refer to callow efforts to dishonor the Text (e.g., “I think we need a few more scenes in the jail”). Instead, I mention simply the most important efforts by believers, often Adepts, to sow petty doubts. There is, for instance, the efforts to replace the canonical status of this Text by later, more derivative ones (El Dorado; Rio Lobo). Uneven and fragmentary, they have never achieved widespread recognition of Sacredness. Other heresies claim our text itself is derivative, and one offers the biggest challenge to the devout.

I refer of course to the Heresy of the Spittoon.

In the Genesis section already mentioned, Nemesis Burdette flips a coin into a spittoon, and He Who Is Called Dude, needing to buy drink, stoops to retrieve it from the rancid vessel.

Only the intervention of He Who Is Called Chance saves He Who Is Called Dude from this act of degradation. This passage has a parallel later in the Text, when another nemesis must fish a coin out of a spittoon.

The reversal in power is also a step in the redemption of He Who Is Called Dude.

But Adepts have noticed that in Decision at Sundown, a text attributed to one Budd Boetticher and dated 1957 (the Sacred Text we have is dated 1959), a sheriff refuses to accept the money of the protagonist and drops the coins into a spittoon.

Consider another passage in another Boetticher-signed text of the era, Buchanan Rides Alone (confirmed to be from 1958). Here the protagonist, prosaically named Buchanan, disarms a young gunslinger and drops the boy’s bullets into a spittoon.

The vessel, offscreen below frame, announces its presence by the tinkling sound made by the falling rounds.

Heretics have hinted at plagiarism, especially in the light of a reference in another text of the period, Ride Lonesome (dated February 1959, two months before the appearance of our Sacred Text). Here a nemesis tells of a poster “gun-tacked to every tree and stump (!) between here and Rio Bravo.”

While undeniably puzzling, these correspondences do not point to plagiarism. There may have been an earlier, Ur-version of our Sacred text, that has simply not survived. In moments like these we must put our faith in the Authors.

Recurring formulae

Finally, we must return to the Word. Seeker, Initiate, Adept, Exegete: All acknowledge the Text’s verbal echoes. As with Homer’s wine-dark sea and Vergil’s pious Aeneas, formulaic tags recur in our tale, but with more variation than in classic texts.

Our first business is business.

We have important business …. Me and my friend we make our business alone.

I’ll tell you what I’m a lot better at, Mr. Wheeler. That’s minding my own business.

I figure why is not my business./ You’ve got peculiar ways of choosing what is your business.

You think I’ll ever get to be sheriff?/ Not unless you mind your own business.

As if to signal to the devout the importance of every word, the Text provides its own meta-commentary. As a French exegete has said: “Discourse cleansing discourse, backchat ruling over chatter and chitchat.”

I’ll go outside so you can talk more freely.

I guess I talk too much.

He’ll keep talking till we get out of here.

Can’t you talk plainer than that?

Young Colorado says that Nemesis Nathan Burdett is “talking now” through the Deguelo tune./ I guess we made him talk after all.

Me, I just talk all the time./ You most certainly do./ You’ll get used to that. You’ll have to. Either that, or start talking to me.

Now I’m running out of breath. You talk if you want to.

Like all Sacred Texts, for all this talk of talk, this one knows that the ultimate truth lies beyond words.

Just stop talking. Just let it be.

Good advice.

Before I followed the Way, the spittoon was a spittoon. As I began to learn the Way, the spittoon was more than a spittoon. When I had learned the way, the spittoon was once again a spittoon.

Addendum 15 April 2012: This humble guide to the Text has aroused further passion among Exegetes. Three have pressed even more fiercely the Heresy of the Spittoon, claiming that it derives from a much more ancient text than the Boetticher-attributed ones mentioned above.

Antonio of the Red Palace writes:

Regarding the scene involving the spittoon, I think it’s a shout-out to another one from Sternberg’s Underworld. You know, that one involving an equally “Borachone” character (Rolls Royce Wensel) being humiliated by “Buck” Mulligan. Interestingly, the “hero” (in this case Bull Weed) stands for the weak one.

Even in both films, the female character is called Feathers. ¿ Coincidence?

The Exegete declares a heartening willingness to believe, as all Seekers must, that There are no coincidences. From David Cairns, Sifu of Shadowplay, Exegete Extraordinaire of many other texts, comes further observations:

Like Antonio of the Red Palace, Shadowplay Sifu displays admirable historical awareness and interpretive ingenuity. But there is still room for disputation about sources and the path of influence. Here is Lea Jacobs of the School of the Badger to open another avenue:

The earliest version of the coin in the spittoon that I know is Underworld. Charles Furthman, brother of Jules [scribe who co-penned Rio Bravo], worked on the adaptation [of Underworld]. So I have always assumed the bit was “in the family.”

It is a measure of the spiritual power of the Sacred Text that it so stirs the imagination of the devout. And in truth, this scrolling blog’s little guide should have pointed out the strongest evidence for the Spittoon heresy (as well as the philological question of “Feathers”). These Exegetes are hereby thanked for extending the already vast commentary on the Text. But let us remember that the earlier text in question is regarded by many Adepts as itself derivative.

In Underworld, the nemesis who flings a ten-dollar bill into the spittoon is called “Buck” Mulligan–a transparent trace of literary lineage. For what readers text do not recognize the reference?

Stately, plump Buck Mulligan came from the stairhead, bearing a bowl of lather on which a mirror and a razor lay crossed.

Let us not forget that this literary “Buck Mulligan” has the proper first name Malachi, usually translated as “God’s messenger.” This surely changes our understanding of the blowhard who mockingly offers the ten-dollar bill to Rolls Royce; for he starts Rolls Royce on his path toward sobriety and self-respect.

For such reasons, Ulysses is most fruitfully read as a gloss on Underworld.

Nonetheless, consultation with wiser heads than this chronicler’s yields a change in the Canon. Henceforth the Heresy of the Spittoon will be known as the Cuspidor Crux.

Addendum 21 April 2012: Another Adept, Simone Starace, has disclosed more evidence for the Cuspidor Crux. She points to a passage in the secondary writ, Joseph McBride, Hawks on Hawks (1982), p. 131:

JMB: There are several things in Rio Bravo that are similar to Underworld, which you and Furthman also helped write.

HH: I stole two things, the dollar in the spittoon and the girl’s name, Feathers.

Simone adds that on page 159, according to McBride’s filmography: “Hawks claimed to have contributed to the script of Underworld.” The palimpsest thickens.

The 50-50-50 split

Independencia (Raya Martin, 2009); set photo by Alexis Tioseco. Our comment here.

DB here:

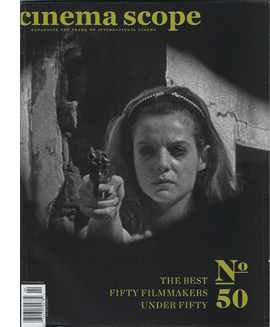

I received the newest Cinema Scope after we had posted our book roundup last week. Awkward timing, but I can still alert you to this splendid effort. In the tradition of Cahiers du cinema (every film magazine wants to be Cahiers), this enterprising Canadian journal has celebrated a benchmark issue with a compendium–issue 50 devoted to 50 filmmakers (all under 50).

It’s a gimmick, but a good one, and of ancient lineage. Cahiers and other French journals established an admirable tradition of obsessively gathering brief entries on filmmakers under a thematic rubric. (The organizing principle: alphabetical order.) In this contribution to the tradition, Mark Peranson, Andrew Tracy, and the rest of the Cinema Scope équipe have outdone themselves.

We get, of course, critics aplenty, and they offer short, sharp takes: Kent Jones on Maren Ade, Scott Foundas on Wes Anderson, Andrea Picard on Liu Jiayin, Shelly Kraicer on Pema Tseden, Chuck Stephens on Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and many more admirable matchups.

This sort of thumbnail catalogue works best when encapsulation is kept to the scale of American menu squibs, or even fortune-cookie apothegms. The phrases don’t have time to turn gently, so they careen. Tony Rayns on Jia Zhangke:

This sort of thumbnail catalogue works best when encapsulation is kept to the scale of American menu squibs, or even fortune-cookie apothegms. The phrases don’t have time to turn gently, so they careen. Tony Rayns on Jia Zhangke:

With a sensibility pitched at the exact mid-point between Robert Bresson and Arthur Freed….

Christoph Huber on Paul W. S. Anderson:

Brit-born Paul W. S. is the elder, least pretentious, and most consistently amusing Anderson of the current director trifecta: its termite artisan.

Michael Koresky on Kore-eda Hirokazu:

He’s at his best when there’s the least mess.

It’s not all praise, either. Adam Nayman contributes a vinegar-doused write-up of Paul Thomas Anderson, although he likes one cut in There Will Be Blood. Alex Ross Perry finds that Fincher’s latest work is uninspiring, but at least now “he can screw around all he wants.”

As if this weren’t enough, filmmakers (another Cahiers tradition) add their voices, and images, to the chorus. So there are Weerasethakul on Lucrecia Martel, Ben Rivers on Bertrand Bonello, James Benning on Sharon Lockhart, and Albert Serra on Zhao Liang, among others.

One purpose of such a Baedeker’s is to alert you to new work. I counted a dozen directors I hadn’t heard of, and another four or five whose films I hadn’t seen. But this kind of enterprise has long-range impact too, especially right now. Cinema Scope 50-50-50 is a bracing psychic antidote to the usual complaints about today’s empty, worthless cinema, and its inferiority to the dazzlement on view on HBO and AMC. For a recent example of this litany, see Wolcott, who yearns for the days of An Unmarried Woman. Projects like the Cinema Scope celebration lift your eyes to the horizon. You can start to believe in cinema’s future.

Are these directors marginal? Not really. The fretful, wayward margins can, when they hit critical mass, become a mighty phalanx. That’s what happened with auteurs in studio Hollywood, art-house movies in the 50s and 60s, new and young cinemas thereafter, etc. The future often lies on the periphery.

We get all this, along with the usual provocative columns by Cinema Scope regulars Peranson, Picard, Rosenbaum, Möller, and Stephens; a sort of storyboard for a new Benning project; Denis Côté musing on his Bestiaire; Hubler’s encyclopedic tribute to Sherlock Holmes movies; an interview with Hoberman (“The decline of the Voice has been going on longer than the death of cinephilia”), and much more. Even the ads are intriguing.

Sooner or later, you know you will obtain this. Why not now? A mere $5.95 Canadian, almost exactly the US price, at least today. This issue is so new that it apparently hasn’t been registered on the website yet, but go there anyway. You might as well subscribe.

Alps (Yorgos Lanthimos, 2011).

Bringing to book

Artists and Models.

Blushing from Bryce Renninger’s generous article about us and the new edition of Film Art can’t keep us from offering another of our occasional entries devoted to new books we like. Get ready for lots of peekaboo links.

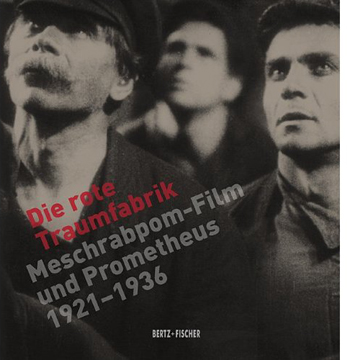

The rise of the Soviet Montage film movement of the 1920s and western countries’ knowledge of those films came about largely because of Germany. After pre-revolutionary film companies fled the Soviet Union, taking much of the country’s film equipment with

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

them, the re-equipment of studios with lighting equipment, cameras, and raw stock was made possible largely through imports from Germany. Once Eisenstein and other directors began making films, they were exported to Germany, where their theatrical success led to further circulation in France, the United Kingdom, the USA, and elsewhere.

There was a direct link between Soviet and German socialist film production and distribution that is too little-known today. In 1921, Willi Münzenberg forms the Internationalen Arbeiterhilfe (the IAH, known in Russia as Meschrabpom), based in Berlin. In 1924, the organization founded a film studio in Moscow, Rus. A year later, a sister company, Prometheus, was formed in Berlin. Both produced films, and they cooperated in distributing each other’s output.

Meschrabpom-Russ produced many of the familair Soviet classics: early on, Polikuschka and Aelita, and later the films of Pudovkin (including Mother and The End of St. Petersburg) and Boris Barnet (including Miss Mend and House on Trubnoya). Prometheus produced films highly influenced by the Soviet exports, both in terms of style and subject matter. These included Leo Mittler and Albrech V. Blum’s Jenseits der Strasse, Phil Jutzi’s Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück, and, mostly famously, Bertolt Brecht and Ernst Ottwald’s Kuhle Wampe oder wem gehört die Welt.

Prometheus, not surprisingly, disappeared in 1933. Meschrabpom-Russ continued until 1936.

A retrospective at the Internationale Filmfestspiele in Berlin in 2012 has occasioned a comprehensive, beautifully designed catalogue, Die rote Traumfabrik: Meschrabpom-Film und Promethueus 1921-1936. With numerous expert essays and beautifully reproduced illustrations, both in color and black and white, of posters, production photos, film frames, and documents, this is the definitive publication on the subject. Even those who don’t read German will be able to use the extensive filmography and the biographical entries on the directors and other people involved in the making of the films. The illustrations make this the perfect combination of academic study and coffee-table art book. (KT)

Closer to home, our friends have been very busy. From Leger Grindon, a deeply knowledgeable specialist in American film, comes Knockout: The Boxer and Boxing in American Cinema. The prizefight movie isn’t usually discussed as a distinct genre, but after reading this comprehensive and subtle study, you’ll likely be convinced that it’s been remarkably important. While discussing movies as famous as Raging Bull and as little-known as Iron Man (no, not that one; this one comes from 1931), Leger also introduces you to the finer points of genre criticism. The way he traces basic plot structures, key iconography, and historical patterns of change is a model of how thinking in genre terms can illuminate individual films.

Then there’s Tashlinesque: The Hollywood Comedies of Frank Tashlin. Ethan de Seife goes beyond the usual recounting of peculiar, often lewd gag moments to treat Tashlin as not only a gifted director but a representative figure in 1940s-1950s American cinema. Ethan traces how Tashlin became a program-picture director who never acquired the status of auteur, at least in the eyes of the studio system. The book situates Tashlin in the context of the Hollywood industry, both the cartoon shops (Tashlin did animation work for both Disney and Warners, among others) and the live-action production units. There’s as well a fascinating chapter on Tashlin’s influence on directors as different as Joe Dante and Jean-Luc Godard, who coined the adjective “Tashlinesque.” A blend of critical analysis, cultural commentary, and industry history, Tashlinesque is surely the definitive book on this cheerfully dirty-minded moviemaker. Ethan maintains a lively blog here.

Not strictly about cinema, but a book that’s indispensible for film researchers, is James Cortada’s History Hunting: A Guide for Fellow Adventurers. A founding member of the Irvington Way Institute, Jim is at once an IT guru, a historian of computer technology, and a scholar of Spanish history, particularly of the Civil War. History Hunting, the fruit of forty years of spelunking in archives, museums, and the world at large, is an enjoyable handbook on doing historical research. It ranges from help with genealogy (case study: the colorful Cortadas, from Spain to the US) to suggestions about how to frame a doctoral thesis. Jim reminds us that the historian must turn into an archivist: the materials you collect are documents for future historians to use. You are, to use the new buzzword, a curator. Jim provides a welter of practical suggestions along with his own tales of the hunt. Jim devotes part of a chapter to Kristin and me, which just goes to show his impeccable taste in neighbors.

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

Joseph McBride is known as a film historian—his biographical books on Ford, Welles, and Spielberg are scrupulous and insightful—but he also teaches screenwriting. Why not? He wrote the cult classic Rock and Roll High School. Writing in Pictures: Screenwriting Made (Mostly) Painless is a unique manual in that it minimizes how-to instructions. Joe acknowledges the centrality of the three-act structure, but he takes a step back and asks what engages us about stories to begin with. His advice is clear-sighted. Don’t follow trends; don’t worry about “high-concept” ideas or “character arcs” or “plot points.” Closely study the masters of storytelling in fiction and drama and film, and absorb not formulas but a feeling for the flexibility of narrative technique.

One of the most original aspects of Writing in Pictures is Joe’s emphasis on adaptation. This is sensible because (a) a great many films are adapted from other sources (today, even comic books); (b) a professional screenwriter is often called upon to reshape an earlier script draft by another writer; and (c) adapting a preexisting source swiftly gets the novice screenwriter thinking about the relative strengths of verbal and visual storytelling. Joe takes us through the script-building process step by step, each time reworking London’s story “To Build a Fire.” Somewhat like the European “conservatory” approach to film education, McBride’s emphasis on organic interaction with classic traditions is something new, even radical, in the world of American screenplay education.

Then there’s Film and Risk, edited by the boundlessly prolific and enthusiastic Mette Hjort. Probably the most conceptually bold cinema book of the year, it assembles several scholars and filmmakers to assess how films and filmmakers deal with risk. The subject is of course broad. There’s risk in performance; risk in breaking stylistic boundaries; risk within film institutions (such as producing); risk in social and political contexts such as facing censorship; environmental risks, as in the costs that filmmaking exacts from the natural world; and even the risks of viewing movies—exposing yourself to horrifying or depressing stories and images. Film scholars like Hjort, Paisley Livingston, and Jinhee Choi mingle with film producers and industry observers to reflect on how cinema takes chances.

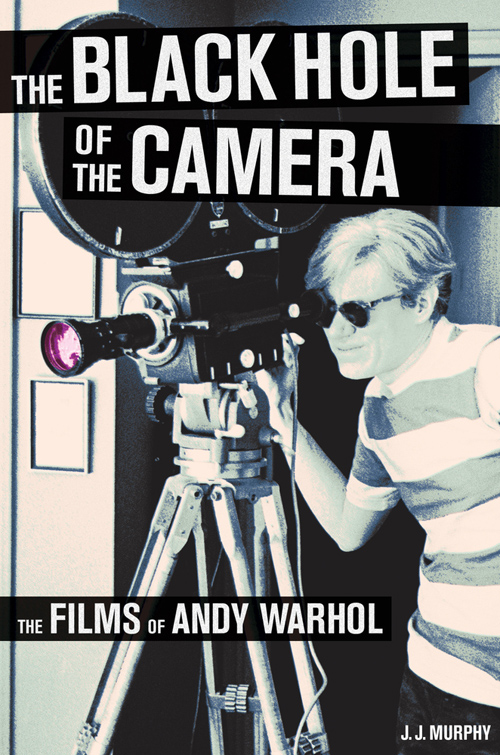

Our colleague J. J. Murphy has been researching and teaching the films of Andy Warhol for years, and today–literally, today–his monograph The Black Hole of the Camera: The Films of Andy Warhol comes out from the University of California Press. This is the most comprehensive, in-depth study of Warhol’s filmmaking that has ever been published, and of course a must-have for anyone interested in experimental film or the American art scene.

The ideas are fresh, especially the explorations of Warhol’s debt to psychodrama. At the same time, The Black Hole of the Camera clears away many misconceptions about Warhol (no, Sleep and Empire are not single-shot films) while also offering detailed information about and analysis of little-known stunners like Outer and Inner Space. There are several pages of color frames, which remind you that Warhol was as good at color as Tashlin was. JJ maintains a remarkable blog on independent cinema and is a leading figure in the Screenwriting Research Network.

Not a book, but a publication of great value: Three major researchers have collaborated on a cogent, nontechnical review of experimental investigations into film perception. All of the authors have had face time on this site. Dan Levin has executed breakthrough experiments on “change blindness”–how we miss discontinuities and anomalies in everyday life. (On another dimension, Dan’s film Filthy Theatre is coming up at our Wisconsin Film Festival.) James Cutting, a venerable figure in visual perception research, has ranged across many key areas in his consideration of cinema. He also wrote a wonderful book, available free here, on Impressionist painting. And Tim Smith, virtuoso eye-tracker, is author of one of our all-time most popular blog entries, “Watching you watch There Will Be Blood.”

With three top talents, you’d expect the collaborative paper to be a triumph of synthesis, and so it is. It supplies the best case I know for why we cinephiles should welcome psychologists who test the ways we watch movies. It should be required reading in every film theory course in the land. Access to the published paper requires a purchase or a library subscription, but you can read the preprint version here. Check in at Tim’s blog Continuity Boy for plenty of videos exploring his research (DB).

Finally, we’re sometimes asked why we don’t allow comments on our blog. The simple answer is that we’re not nearly as good at responding to comments as John Cleese is.

The cover of Joe McBride’s book pictured above is from the Faber & Faber edition, which makes a better still than the US edition from Vintage. Same good stuff inside, though.