Pandora’s digital box: Pix and pixels

Monday | February 13, 2012 open printable version

open printable version

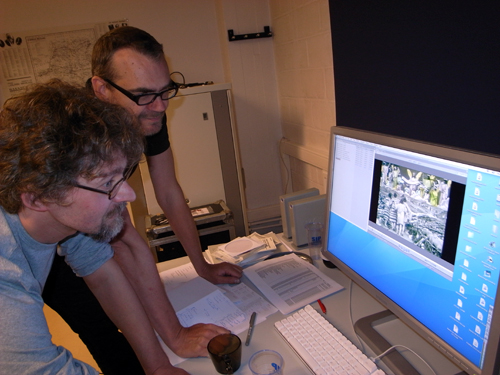

Peter Rotsaert and Vico De Vocht examine a digital version of a silent film at the Brussels Cinematek.

DB here:

Today Dawson City, in the Yukon Territory of Canada, has fewer than two thousand people, but in the 1890s tens of thousands passed through in search of gold. Movies came along too, but the remoteness of the place made it the end of the line for most prints. Many were stored in the basement of the Carnegie Library. In 1929, an enterprising bank worker shifted them to an abandoned swimming pool. The stacks of films were covered with planks, and they were in turn covered by earth, so the films were buried in the permafrost. The surface became an ice hockey rink.

In 1978, builders discovered the film cache. Sam Kula, then an archivist at the National Archives of Canada, stored the films temporarily in an ice house. The painstaking process of checking each reel began. Eventually the US Library of Congress was brought in because most of the 507 reels discovered were American. Among the finds were a Harold Lloyd short, a great deal of news footage, and a rich array of serials starring heroines of the 1910s.

Wellington, New Zealand, was another terminus for American movies during the old days. In 2009, a film preservationist from the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences learned that the New Zealand Film Archive held a lode of Hollywood films. The collection, reviewed here, includes many Westerns and Christie comedies, along with John Ford’s supposedly lost Upstream (1927). The restored Upstream played in festivals and special screenings during 2010 and 2011. Five American archives have been involved in restoring the seventy-five titles selected for repatriation.

Whatever the merits of the films revealed—literally unearthed, in the Dawson instance—discoveries like these are signs of hope. Who knows how much more of our film heritage remains to be rediscovered? For this reason, George Eastman House archivist Paolo Cherchi Usai prefers to list a film not as “lost” but rather as “not yet found.”

Given such discoveries, the archivists will set to work creating usable and enduring versions. But today such a task is much harder. Soon most of the films we make and show will not exist on photochemical stock. They’ll be digital files, and they need to be kept securely. But how?

Will today’s typhoon of ones and zeroes rip away our analog past? Will there ever be a digital Dawson City, a stockpile of files of lost movies? It seems likely that digital projection has, in unintended and unexpected ways, put the history of film in jeopardy.

Digital restoration: A success story

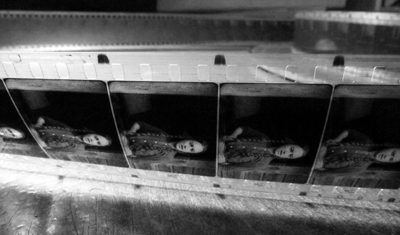

Nitrate decomposition; from Bill Morrison’s Decasia: The State of Decay (2004).

Of the tens of thousands of feature films produced worldwide in the silent era, approximately ten per cent survive.

Jan-Christopher Horak, Director, UCLA Film and Television Archive

The archives I’m speaking of are either public ones, like the Library of Congress, or privately supported ones like Eastman House and the Museum of Modern Art. These and hundreds of smaller archives are nonprofit institutions charged with protecting images and sounds we’ve deemed of cultural value. By contrast, a studio-based archive aims to maintain the firm’s investment in its property. Often studios deposit films of historical importance at nonprofit archives; some countries require by law that copies of films circulated there be deposited in the national archive. Both sorts of archives have done excellent work, but I’ll be talking largely of the nonprofit ones, which often receive films by donation, deposit, purchase, or accident.

Archivists distinguish between conserving and preserving. You conserve a film by taking it into the archive and storing it safely in temperature-and-humidity controlled vaults. You preserve it by cleaning and patching it, and if necessary transferring it to a more stable medium. Restoration, which is the archival task most visible to the film-loving public, goes further. It involves working to bring the film back to something like its original state.

Before the 1970s, archives conserved and preserved, but seldom restored. Archivists at public institutions balanced two duties: keeping films safe for the future and screening them for the public and researchers. Like art museums, archives guarded treasures while putting some of them on display.

Most often, archives preserved their material by making the best possible copies. A big part of the job was migrating films from one format to another. For example, some early American film companies copyrighted their product by submitting rolls of paper on which each frame of film had been printed. These “paper prints” had to be transferred, frame by frame, to motion-picture film. Likewise, films surviving only in rare formats, like 9.5mm, 22mm, and 28mm, had to be transferred to 35mm so they could be run on standard equipment. Tinted films on nitrate were reprinted on black and white safety film. 16mm films might be blown up to 35mm, and 35mm might be reduced to 16mm for circulation to schools, libraries, and film clubs.

Most famously, thousands of films in archive collections exist on nitrate stock. That was the professional standard before 1950 or so, when the industry abandoned it. Not only did nitrate film have a habit of exploding or catching fire, but it tended to decompose. Experimental filmmakers have found a sinister beauty in ruined footage, but archivists organized for funding to help transfer their collections to acetate. Then archivists learned that some acetate prints degenerated into a vinegary, contagious vapor. So migration to a new, polyester-based stock became necessary.

Most famously, thousands of films in archive collections exist on nitrate stock. That was the professional standard before 1950 or so, when the industry abandoned it. Not only did nitrate film have a habit of exploding or catching fire, but it tended to decompose. Experimental filmmakers have found a sinister beauty in ruined footage, but archivists organized for funding to help transfer their collections to acetate. Then archivists learned that some acetate prints degenerated into a vinegary, contagious vapor. So migration to a new, polyester-based stock became necessary.

Preservation, simply keeping films alive in long-lasting formats, remained central to archives. In the 1970s a number of archivists also began restoring films. For example, most silent feature films were released in tinted and toned prints, but many copies survived only in black-and white. Restorers, guided by surviving paper records, aimed to create prints that approximated the original color schemes.

Restorers naturally faced decisions about what would count as an original. In 1989 there were six different versions of Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, running from 119 minutes to 132 minutes. In uncertain cases, records of running times and postproduction work helped identify what was missing. If the footage couldn’t be found, still photos or even a blank screen might cover the gaps, as in restorations of Greed and the 1954 A Star Is Born. A musical score helped researchers measure how much footage from the original Metropolis remained to be found.

With the rise of cable television and home video, studios’ film libraries became more valuable. Ted Turner, owner of the MGM, Warner, and RKO libraries, was blamed for “colorizing” some classics for his cable channels, but at the same time he invested in restoring a great many of them. Other firms followed suit. Gone with the Wind and Disney perennials were reworked for cable and VHS release.

The 1980s and 1990s became the great age of restorations. Audiences were reintroduced to Napoleon, Becky Sharp, Lawrence of Arabia, and Vertigo. Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, working with Thames Television, reissued silent classics, with new scores by Carl Davis. Most of the era’s restorations wound up on video platforms. Today Turner Classic Movies is our great display case for studio and off-Hollywood restorations; it’s the closest thing we have to a Citizen’s Film Library.

At first, restoration was a photochemical affair. Every major archive employed experts in rephotography and lab work who knew how to optimize the look of a print. Archivists like Noël Desmet collected information about properties of old film stocks and tinting dyes. Faded films could be reprinted through filters that might bring back some of the old snap. The look of old films was much improved by wet-gate printing, which bathed the frames in a liquid that masked scratches on the base or emulsion.

But not much could be done about the blotchy nitrate decay that might invade a scene, or the dirt and dust that earlier copies of the film bequeathed to the current one. And those films for which no original negative could be found, including Citizen Kane and Singin’ in the Rain, would always be seen as the shadow of a shadow—new copies pulled from earlier, perhaps shabby ones.

The upside was that as long as you kept your source prints and your restorations on 35mm film stock in a cool, dry place, you had material that would last over 100 years. Some day you might find better tools for improving what you had.

That day came fairly soon. The Disney company had a steady income from theatrical and video re-releases of its animation classics, and a 1990 reissue of Fantasia employed some video-paint work to correct flaws in the frames. Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs was then given high-resolution treatment. Dust-busting and color adjustments were made frame by frame. Re-released in 1993, Snow White was the first feature to be restored digitally.

Since then, digital fixups have become a standard method for archival restoration. Footage is scanned into a file at 2K or 4K resolution. Either manually or automatically, the software can correct for jumpy or shaky imagery, do dust-busting, erase scratches, and balance exposure, contrast, and other factors. It can interpolate image areas in order to correct damages in the frame, and it can add tinting or toning. The finished files may then be saved as files or scanned back onto film, as Snow White was. You can see an example from the newly restored Marcel Carné film, Children of Paradise (Les Enfants du paradis).

Soon most restorations are likely to be finished and screened on digital formats, with virtually no 35mm prints circulating.

Born-digital, born-again digital?

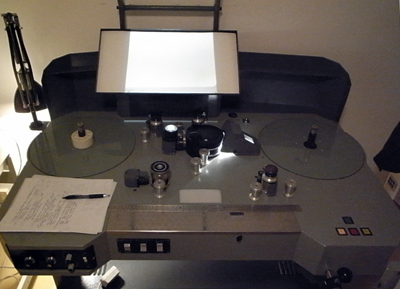

Decay of digital imagery, from Creative Applications.

The preservation of born-digital films is going to be the greatest challenge ever to face archivists.

Margaret Bodde, Executive Director of the Film Foundation

The new magical software has sometimes led to over-restoration. Grain has too often been polished out, creating a plastic sheen. Still, today no archivist can avoid using the new toolkit. The sadder story involves not restoration but conservation and preservation. A civilian might think: That’s simple. Just save film on film and digital on digital. But things are more complicated than that.

Let’s start with a movie like The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, which was shot with digital capture. After production and post-production, it was made available to theatres as both a Digital Cinema Package (that batch of files on a hard drive) and some 35mm prints. But there are several digital versions of the movie.

Digital source material. The original sound and image “content” may be captured in specific formats, either tape-based or file-based. Those formats can vary a lot among themselves. The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, for example, was shot with the Red One camera on the company’s proprietary format R3D. Other cameras don’t use that format. So the footage was converted to other sorts of files for viewing and postproduction work.

Any major film nowadays is likely to use many digital video and audio formats. All these assets are usually stored in the distributor’s vaults.

The Digital Source Master (DSM or DCM). This is the master copy of the finished film, somewhat comparable to a 35mm film negative. It can be in any format selected by the filmmakers. It’s the basis of the distribution master, the home video master, and a master version for archival storage.

The Digital Cinema Distribution Master (DCDM), in formats determined by the Digital Cinema Initiatives. This is the finished film unencrypted and uncompressed, providing “content” at 2K and/or 4K resolution. Roughly speaking, this is the digital counterpart of a 35mm release print.

The Digital Cinema Package (DCP). This is the film compressed and encrypted for theatrical playback. It’s roughly comparable to the delivery of a 35mm print on shipping reels.

The Digital Cinema Distribution Master as played (DCDM*) Once the DCP files are opened and decompressed, they yield image and sound identical to what’s encoded on the DCDM. The DCDM*’s place in the system is somewhat parallel to the projection of a 35mm print from platters.

Eventually, The Girl will show up on the optical disc formats DVD and Blu-ray, not to mention streaming video, cable transmission, and web-based platforms. (Actually, it’s probably already available for Darknet download.)

Many studio films are housed in nonprofit archives too, and until recently those movies have been deposited and stored as analogue copies. But what will those institutions now keep? There are only three minimally acceptable formats: the uncompressed and unencrypted DCDM, the DCP, and a 35mm print. Suppose your film archive is lucky enough to receive both a DCP and a 35mm print of The Girl.

First, how do you access the DCP files? A DCP is typically encrypted to block piracy. When The Girl played theatres digitally, each exhibitor was provided an alphanumeric password that would open the files for loading into the theatre’s server. By the time you the archivist get the files, that key may have expired or been lost. Without the key, the DCP is useless.

Then there’s the matter of storage. The 35 print of The Girl can simply be passively conserved, following the motto, “Store and ignore.” But all digital material, no matter how minor, requires proactive preservation. The future for digital storage is constant migration.

Archivists estimate the life of any digital platform to be less than ten years, sometimes less than five. All hard drives fail sooner or later, and they need to be run periodically to lubricate themselves. Tape degradation can be quite quick; one expert found that 40 % of tapes from digital intermediate houses had missing frames or corrupted data. Most of the tapes were only nine months old.

Moreover, hardware and software are constantly changing. One archivist estimates that over one hundred video playback systems have come and gone over the last sixty years. Archives currently recognize over two dozen video formats and over a dozen audio ones.

Periodically, then, the DCP files of The Girl will have to be checked for corruption and transferred to another tape or hard drive and eventually to another digital format. Such maintenance takes time; shifting a terabyte of data from one system to another may need at least three or four hours. Ideally, you’d want several copies for backup, and you’d want to store them in different locations.

There are hundreds of other films like The Girl awaiting processing at major archives. About 600-900 feature films are produced in the US each year. Currently the world is producing about 5500 features per year. At some point, they will all originate in digital capture.

Besides access and storage there’s the matter of cost. Storing 4K digital masters costs about 11 times as much as storing a film master. You can store the digital master for about $12,000 per year, while the film master averages about $1,100.

How do the overall costs of digitizing mount up? Look at the situation in Europe. The EU countries produce about 1100 features and 1400 shorts per year. An EU archival commission, the Digital Agenda for European Film Heritage, estimates that to conserve one year’s output would require 5.8 PB (petabytes) of storage. In 2015, the costs of archiving that year’s output (without restoration) are projected to be between 1.5 million and 3 million euros. Beyond initial conservation, long-term preservation of that year’s output would consume, though migration and backing up, about 1900 PB and cost about 290 million euros.

The access problem is soluble. Your archive could be given an unencrypted DCP of The Girl and then create its own key to prevent copying. Or the DCP could be assigned a generic key, perhaps for a specified time period, that will open the files in a secure milieu. They could then be migrated to a format under archive control. On the matter of software, archivists are working on establishing standard preservation file formats and codecs. To deal with the other problems, you’d have to press for increased budgets and personnel to cover the new duties that digital archiving creates. But the costs, including training personnel on ever-changing platforms, are of tidal-wave proportions.

Photochemical Armageddon?

The methods we have for securely storing comprehensible digital data are highly labour-intensive. Humans are too slow and they cost too much.

Bruce Sterling, science-fiction writer

So why don’t you preserve The Girl’s files on film? Film is universally recognized as the most stable platform for moving-image material. Properly stored, a film print can last a hundred years or more. Maintaining a print, as we’ve seen, is cheaper than maintaining digital files. It’s significant that the archives of most of the major studios continue to transfer all their current features to film via color separations on polyester stock.

Apart from the costs of making file-to-film transfer, which can amount to tens of thousands of dollars, the long-range problem is technology. The same forces that shoved out 35mm projection have made 35mm preservation much harder. The equipment for outputting digital files onto film will eventually cease to be available. With the rise of digital projection, demand for film stock plummeted. Eastman Kodak’s recent bankruptcy filing reflects the declining market for raw film, and even though Fuji promises to continue to make 35mm stock, it is likely to get more expensive. As David Hancock of IHS Screen Digest points out, the cost of silver, a necessary component of raw stock, is rising steeply after being low for many years.

Sensing a niche market, Kodak has announced that it will provide a new emulsion favorable to archival preservation. But at the moment, laboratories that can process and print any film stock are closing. Not for nothing does Nicola Mazzanti, Director of the Royal Film Archive of Belgium, suggest that an archive should consider buying a lab, which is likely to be available at a low price.

If preserving on film is increasingly unlikely, how about preserving on digital formats? Perverse as it sounds, can you take your 35mm print of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and store it as tape or files? Yes. This is called “digital reformatting.” Once film has been scanned, archives can make DCPs at low cost. But the initial scanning is costly, and high-end 35mm scanners, though still in use to make Digital Intermediates for 35mm releases, are likely to be costly for nonprofit archives. In any event, saving film digitally puts us back to the problems of digital conservation and preservation: cost, storage, maintenance, and access. (Surely the rights holders will want the archive to encrypt its home-made DCPs.)

Preserving on film may simply postpone Armageddon. As the most recent European report of the Digital Agenda for European Film Heritage concludes:

As a solution [digital migration to film] will only be viable as long as the analogue film ‘ecosystem’ (equipment, film stock, laboratories) exists. Instead of being a long-term solution, the risk is that it becomes a very short term one. In the long term it will make problems worse as it will increase the number of works that need to be digitised in the future. . . . At 25,000 euros to 100,000 euros per feature film, the going-back-to-film solution appears to be 20 to 80 times more expensive than digital preservation.

It’s hard to get your mind around the scale of the problem. Here is Ken Weissman of the Library of Congress:

Speaking very broadly, with 4K scans of color films you wind up in the neighborhood of 128 MB per frame. . . . Figure that a typical motion picture has about 160,000 frames, and you wind up with around 24 TB per film. And that’s just the raw data. Now you process it to do things like removing dust, tears, and other digital restoration work. Each of those develops additional data streams and data files. We’ve decided, based upon our previous experience, that it is best to save the initial scans as well as the final processed files for the long term. Now we are up to 48 TB per film. In our nitrate collection alone, we have well over 30,000 titles. 48 TB x 30,000 = 1,440,000 TB or 1.44 EB (exabytes) of data.

Weissman adds with a trace of grim humor: “And of course you want to have a backup copy.”

The girl with the photochemical tattoo

I think that film-on-film projection will ultimately become the sole purview of archives and museums.

Michael Pogorzelski, Director of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences Film Archive

Once you’ve found a way to conserve-preserve The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, what if you want to show it tomorrow? Or ten years from now? Or fifty?

If you have a DCP in good shape, and a projector that will show 2K/4K according to the Digital Cinema Initiative standard, you’re good to go. For now. But maybe not tomorrow.

Once the projector/ server market has saturated and everybody has DCI-compliant equipment, equipment manufacturers and software designers have to keep innovating to sell new machines. Many observers expect the D-cinema standard to be recast in the next ten to fifteen years, and projectors may be redesigned sooner than that. Mazzanti anticipates that there will be 8K resolution, greater bit depths, faster frame rates, laser projection, new sound formats, and other advances. Already innovations are leapfrogging DCI standards: last month, a new generation of projectors was showcased. If you program your digital version of The Girl for its twenty-fifth anniversary in 2036, you will probably have to reformat it for whatever your projector can then play.

So instead you hold on to your 35mm print. That will give you cachet, because within a decade all commercial cinemas will be digital, and, as Mike Pogorzelski mentions, only archives will show 35. But cachet takes cash. Archives, at least the major ones, will have to retain their 35mm inspection and projection gear, even though that will probably cease to be made and parts will be cannibalized. You’ll need vigilant, resourceful staff who know how to fix old machines.

Moreover, with the scarcity of raw stock and the shuttering of laboratories, archives will be less likely to make screening copies of their holdings. Virtually every 35mm copy you the archivist hold, from Red Desert to a Bowery Boys movie, becomes irreplaceable, what Mazzanti calls a “unique master.” Then film archives will truly become film museums, custodians of extremely rare artifacts.

At some point no one may risk running analog film, as the damage would be irreparable. In that worst-case scenario, archives will show digital copies, either derived from prints or supplied by whatever sources they can find (including, yes, Blu-ray or whatever comes after). One consequence may be the freezing of the canon. We’ll get more and better versions of old standbys like Metropolis and Napoleon, but less effort to retrieve lost or ignored items from scratch. New discoveries may simply be too expensive to maintain, especially if they lack the crowd-pleasing appeal of the most famous classics.

I biased the case by taking as typical a major studio production like The Girl. What about the hundreds of independently made shorts and features? I’m thinking of documentaries, DIY features, animated shorts, and experimental works. Each was made on whatever video or film format the filmmaker could find or could afford, and it was finished with almost no thought of how it would be preserved. The Science and Technology Council of the Academy recently published its second comprehensive study of “the digital dilemma” and were surprised that most of the filmmakers they interviewed were unaware of how perishable their work was. Says Milt Shefter, an author of the report:

They were concentrating on the benefits of the digital workflow, but weren’t thinking about what happens to their [digital] masters. They’re structured to make their movie, get it in front of an audience, and then move onto the next one.

Still more unaware, I imagine, are all the people making amateur footage.

Lumière’s La Petite fille et son chat was made in 1900 and is still around to charm us. The YouTube adventures of Maru, a LOLcat superstar, aren’t likely to last so long.

Envoi

Adroit archivists are trying to come to grips with these problems, and I’m sure they’ll make some headway. These are people of great expertise, good will, and idealistic obstinacy. As far as I can see, they’re somewhat divided. Some favor moving into digital preservation immediately, since that is going to be inevitable at some point. Others suggest keeping with film as long as possible. When the inevitable comes, the archive would preserve films and their associated technology as historical artifacts, somewhat like Japanese ukiyo-e prints or Fabergé eggs. Alexander Horwath of Vienna’s Filmmuseum writes:

The museum is not the worst place to end up, quite the opposite. Even in the most “unthinking” museum, the strange material shape of the artifact reminds visitors of alternative forms of social and cultural organisation and, therefore, that the currently dominant forms and norms are not the only ones imaginable: forms and norms are never “natural”, but historical and man-made. . . . Today, the expression ‘You’re history!’ is meant as an insult, not as a factual statement. Isn’t it essential, therefore, to side with those so insulted in order to keep alive any notion of historicity?

I’m not equipped to weigh in on this professional dispute. For my part, I’m hoping that this blog’s readership, mostly curious cinephiles, will sense the enormity of what archives face.

Most discussions of The Digital Revolution have concentrated on production, and no doubt that’s important. At the high end of studio-supported projects, though, 35mm is still widely used. But whether shot on film or digitally, as long as movies were distributed and screened on photochemical prints, we had, at least in principle, long-term access to them. As someone who studies films from many periods and places, on prints whenever possible, I’m grateful that film on film was the norm throughout most of my career.

Now it’s clear that the switchover to digital distribution and projection had a far more sweeping impact on film culture than almost anyone expected. It hastened the decline of the film manufacturers, who flourished when saturation booking and day-and-date release required thousands of prints. Digital projection helped push more filmmakers into digital capture, since it threatened to make 16mm and other small-gauge formats unshowable. It changed multiplexes, giving distributors and funders unprecedented oversight of screenings. It sacked projectionists, who were often bearers of practical wisdom and technical knowledge. It reconfigured theatre architecture. (Boothless projection is already here.) It forced small exhibitors to invest in expensive equipment. It threatened art house theatres that play unique roles in their communities. And it turned film archives into residual institutions that have to mop up after many cycles of media churn.

The digital gold rush, along with fear of piracy, favored short-term solutions and proprietary, incompatible software and hardware. There were too many ephemeral video formats chasing the consumer and prosumer market, with little thought of their afterlives. The days of 8mm, super-8mm, 16mm, 35mm, and 65/70mm were simple by comparison. We’re left with a plethora of transitory standards that will be impossible to recover. Nonprofit archives will struggle to maintain collections with any thoroughness. Choosing what to save, always necessary, will now become crucial. Only a fraction of what we have can be conserved–not preserved, merely kept.

And new discoveries? Brussels curator Nicola Mazzanti entitles his penetrating overview of the digital conversion, “Goodbye, Dawson City, Goodbye.” I asked Chris Horak of UCLA to imagine a scenario in which a future cache of digital movies has been discovered in an obscure place, permafrost or no permafrost. He answered:

If I found a reel of 35mm film in 500 years and didn’t know what it was, I could probably without too much trouble figure out a way to reverse engineer a projector. In any case, I can always look at the individual frames, even without a projector, and see what is there.

If I find a cache of Blu-rays and DCPs in 500 years, what do I have? Plastic waste. How do you reverse-engineer those media? Impossible. Without an understanding of the software and the hardware, you have zip. No way to look at it, no way to know even if it has any information on it.

This is the sixth entry in a series on the worldwide conversion to digital projection.

Arne Nowak provides an excellent overview of how new exhibition technologies are affecting preservation in “Digital Cinema Technologies from the Archive’s Perspective,” AMIA Tech Review (October 2010). A brief but informative lecture by Mike Pogorzelski on the subject is here. He explains how the Pixar crew found that they couldn’t access their original files from Toy Story. See also Leo Enticknap’s article “Electronic Englightenment or the Digital Dark Age? Anticipating Film in an Age without Film,” which argues that digital changes create crucial new responsibilities for film archives. It’s available in Quarterly Review of Film and Video 26 (2009), 415-424.

I took information about the digital capture of The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo from Jay Holben, “Cold Case,” American Cinematographer 93, 1 (January 2012), 34-36.

Much of the information I’ve cited comes from two crucial reports from the Science and Technology Council of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, both available online. The first, published in 2007, is The Digital Dilemma: Strategic Issues in Archiving and Accessing Digital Motion Picture Materials. It concentrates on strategies for safeguarding studio archives, but much of the information about archival storage is relevant generally. The Digital Dilemma 2: Perspectives from Independent Filmmmakers, Documentarians, and Nonprofit Audiovisual Archives, was published earlier this year.

I’m particularly grateful to Nicola Mazzanti of Brussels, who shared his ideas with me last summer and in correspondence afterward. I’ve drawn extensively on his “Goodbye, Dawson City, Goodbye,” in AMIA Tech Review (April 2011) and his PowerPoint presentation, “The Twin Black Hole: Key Findings and Proposals for the EU-Commissioned Study Digital Agenda for European Film Heritage,” EFG Conference, Bologna 30 June 2011. The final report of DAEFH is now available. If you think my assessment is glum, a little browsing in that report will make my entry look rosy. The quotation above is from p. 76.

Thanks as well to Antti Alanen of the National Audiovisual Archive of Finland, Schawn Belston of the Twentieth Century Fox library, Thomas Christensen of the Danish Film Archive, Grover Crisp of Sony Pictures Entertainment, Jan-Christopher Horak of UCLA, Alexander Horwath of the Austrian Film Museum, Mike Pogorzelski of the Academy Film Archive, Jeff Roth of Focus Features, and Quentin Turnour of the National Film & Sound Archive of Australia. For a nice web lead, thanks to Paul Rayton and John Belton.

For more on the effects of digital archivery, see Jan-Christopher Horak, “The Gap between 1 and 0: Digital Video and the Omissions of Film History,” Spectator 27, 1 (Spring 2007), 29-41, from which my first Horak quotation comes; and Charlotte Crofts, “Digital Decay,” The Moving Image 8, 2 (Fall 2008), xiii-35. Several quotations I’ve embedded are from participants in “Film Preservation: A Critical Symposium,” ed. Jared Rapfogel and Andrew Lambert, Cineaste 36, 4 (Fall 2011). Additional comments can be found online here.

Early premonitions of the problem of digital preservation came from science-fiction writer Bruce Sterling in his 2001 talk, “Digital Decay.” A later, still more pessimistic warning, is here. Another prescient early piece is also from 2001. Howard Besser’s “Digital Preservation of Moving Image Material?” appeared in The Moving Image 1, 2 (2001) and is available here.

Sam Kula’s account of the Dawson City collection can be read in “Up from the Permafrost: The Dawson City Collection,” in This Film is Dangerous: A Celebration of Nitrate Film, ed. Roger Smither and Catherine A. Surowiec (Brussels: FIAF, 2002), 213-218. On the Paper Print Collection and its use in avant-garde cinema, see Gabriel M. Paletz, “Archives and Archivists Remade: The Paper Print Collection and The Film of Her,” The Moving Image 1, 1 (Spring 2001), 68-93. A helpful overview of changing archival practices is offered by Sarah Ziebell Mann in “The Evolution of American Moving Image Preservation: Defining the Preservation Landscape (1967-1977), The Moving Image 1, 2 (Fall 2001), 1-20. My quotation from Alexander Horwath comes from a manuscript version of his contribution to Film: Tacita Dean (London: Tate, 2011).

On digital restoration, see Giovanna Fossati, From Grain to Pixel: The Archival Life of Film in Transition (Amsterdam University Press, 2009). Disney’s restorations of classics are discussed in David Heuring, “Disney’s Fantasia: Yesterday and Today,” American Cinematographer 72, 2 (February 1991), 54-65; Bob Fisher, “Off to Work We Go: The Digital Restoration of Snow White,” American Cinematographer 74, 9 (September 1993), 48-54; and Scott MacQueen, “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: Epic Animation Restored,” The Perfect Vision no. 22 [1994], 26-31.

PS 13 February 2012: Talk about your convergences. John Bailey’s always-interesting website takes up the same subject on the same day. And he has a further interview with Milt Shefter, whom I quote. Thanks to Stew Fyfe for the link.

PPS 14 February 2012: Howard Besser, author of an early piece on the prospects of digital preservation listed above, writes:

Even though I’ve been the voice of pessimism over these issues for more than a decade, I do see some possible positive outcomes (as in Chinese–crisis incorporates opportunity). One issue that I’ve spent a lot of time on over the past decade is getting filmmakers more involved in the preservation process–which not only eases the burden on archives, but also allows us to save not only rushes and early edits, and will allow us save a multitude of versions of a work with little extra overhead. Another opportunity is that the cost issue (which is much more of an infrastructure cost than of a per-film cost) may drive archives to be more cooperative with one another, with the financial burden forcing groups of archives to band together to share the cost of a digital archive.

Thanks to Howard for corresponding.

PPPS 15 February 2012: Another piece on the problems of digital preservation of 35mm, with comments by George Eastman House archivist Paolo Cherchi Usai. Sorry I didn’t know of it sooner for use in this post, but thanks to Kat Spring for the link.

PPPPS 13 March 2012: I’ve recast the portions about the various digital versions of a film to correct my previous, mistaken description of the nature of the Digital Source Master. I’ve added as well a mention of the DCDM*, in order to better explain the parallels between digital versions and analog ones.

Life is like a can of film: You never know what you’re gonna get.