Archive for June 2011

Unquiet silents

DB here:

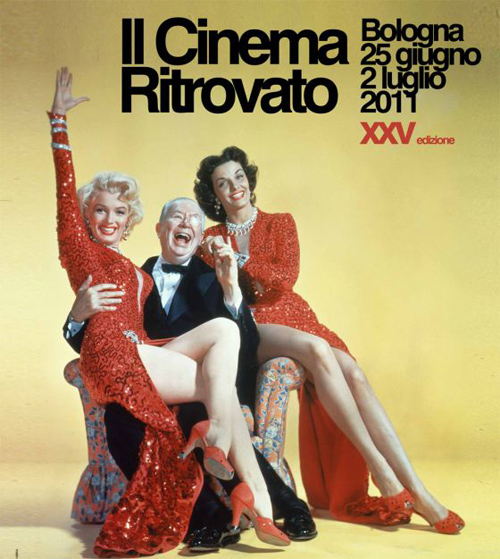

It happens every year: the Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna is offering something for everyone. It’s officially dedicated to film history, but its organizers understand that history includes today. This year you can watch films from 1898 (Gaumont shorts) to 2011 (The Actor, hot from Cannes). Silent cinema is given its due, but so are films from the 1930s-1950s, with glimpses of the 1960s (Petri’s The Assassin, the new La Dolce Vita) and 1970s (Kevin Brownlow’s little-seen Winstanley).

The director retrospectives alone are overwhelming. We have a chance to watch great swatches of films by the celebrated Alice Guy, the underappreciated Luigi Zampa, the effortlessly lyrical Boris Barnet, and the still-being-discovered master of the 1910s, Albert Capellani. Oh yeah, then there’s a guy called Hawks, with a complete set of all his surviving silents filled out with little items like Twentieth Century, Tiger Shark, and thanks to Grover Crisp a lab-fresh restoration of Only Angels Have Wings that had even hard-core Ritrovato veterans gaping.

Not to mention sidebars dedicated to images of socialism and utopia, the development of color cinema, and the annual “100 Years Ago” series curated by Mariann Lewinsky, who brought a stunning array of 1911 films into our ken. With Ayn Rand’s gospel of egoism and selfishness finding ever more adherents these days, a screening of the original Italian version of We the Living (Noi Vivi) reminds us that, contrary to the evidence of this year’s Atlas Shrugged, you can make a pretty good movie from one of her books. (Of course the great Rand adaptation is the out-sized Fountainhead.) In the evenings, on the Piazza Maggiore, items like The Thief of Bagdad and Taxi Driver regale a thousand people or more.

In short, a feeding frenzy for the cinephile. We’ve been here before; you can read reports from the last four years in the category Festivals: Cinema Ritrovato. But this time things are even more intense. A fourth venue has been added, the ample and modern Cinema Jolly, so the decisions about what to see are even more pressing.

Kristin has concentrated her viewing on the 1910s, although so far she’s found time for Wind Across the Everglades and an episode of Barnet’s charming Miss Mend. (She wrote about the Flicker Alley DVD of this here). Her upcoming blog entry will concentrate on Capellani. For now, I find that a mere two films give me something to chew on.

From talky silents to talking movies

Upstream.

Ford and Hawks are very different directors, but two 1927 films, both made at Fox, allow us to see their work blending into a broad trend.

Upstream, recently rediscovered and shown to admiring audiences around the world, takes place largely in a boarding house for struggling vaudevillians. A knife-thrower is in love with his assistant, who is in love with a self-centered ham hired to play Shakespeare. Among the roomers are a declining classical actor and the song-and-dance brothers Callahan and Callahan, one of whom is Jewish. The ham accidentally becomes a star, in the process forgetting the girl he once wooed. But her marriage to the knife-thrower is threatened when the ham returns to the boarding house.

The film has the drawling, anecdotal quality of many Ford comedies. The plot is simple, but it’s decorated with character bits and an overall tone of self-aware corn. The latter was enhanced in the Ritrovato screening by the brash musical accompaniment designed by Donald Sosin, with him on piano and Guenter A. Buchwald on violin. Sosin, like Ford, knows hokum when he sees it, and both know that you must revel in it.

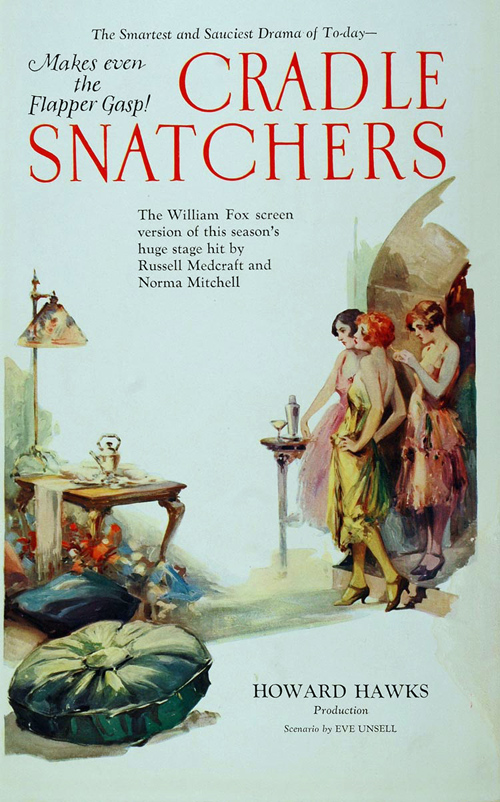

Cradle Snatchers, Hawks’ third film, shows a trio of cheated wives exacting revenge on their philandering husbands. The women arrange for three penniless college boys to pretend to court them so that their husbands can become jealous. Even though some portions are missing, the first reel is intact, and it’s instructive. Instead of opening with the women’s plight, as the source play does, the film starts with the fraternity brothers and mostly anchors our viewpoint to theirs. Variety noticed.

Probably the most remarkable angle of transplanting this “smash” comedy to celluloid lies in the manner in which the three college youths have been duplicated. As a screen threesome they overshadow the women who play the neglected wives. . . Each of the male youngsters does exceptionally well and Hawks has directed them splendidly.

Once Hawks turned it into a male-centered plot, he could indulge in the gay-play that would crop up in his later work. A title points out that “When a roommate takes a girlfriend, he becomes only half a roommate.” One of the boys hangs up on his girlfriend in order to chat up a sexy dame strolling by, but she turns out to be a frat brother in drag (the same Sammy Cohen playing Callahan frère in Upstream). Still, the gags provide equal-opportunity innuendo, as when Louise Fazenda flounces in from a massage and is asked “What have you been doing?” She replies: “I’m not doing, I’ve been done.”

Visually the films are remarkably similar. Removed from Monument Valley, Ford doesn’t give us vistas, deep focus, or even scenes organized around doorways. At home in sparky comedy, Hawks doesn’t provide the graceful, pell-mell staging we get in Twentieth Century and His Girl Friday. Instead, we have classical American silent technique, already by the early 1920s quite polished (as can be seen in the 1922 Ritrovato entry from another master, The Real Adventure by King Vidor).

This silent technique turns out rather talky. Dialogue titles constitute seventeen percent of the shots in Upstream and sixteen percent of the shots in Cradle Snatchers. This isn’t a late 1920s development, since The Real Adventure contains nearly twenty percent dialogue titles. Why are these figures interesting?

The 1920s, the era of the “mature silent cinema,” led many filmmakers and critics to expect that filmmakers would shift toward purely visual methods of storytelling. Keaton’s Our Hospitality (1923), Lloyd’s Girl Shy (1924), and Lubitsch’s Lady Windermere’s Fan (1925) remain dazzling exercises in getting maximum impact from the flow of images, with dialogue titles adding another layer of dramatic interest.

Ideally, the aesthetes thought, one could make a film entirely without titles. German films like Der letzte Mann (1924) are the most famous examples, but there were American experiments along these lines too, such as The Old Swimmin’ Hole (1921). The arrival of sound threatened this trend toward “purely cinematic” narration. Now, critics fretted, filmmakers would be forced to rely on language to make dramatic points. The visual side of cinema would be secondary to “theatrical” methods.

Actually, however, alongside the consummate pictorial storytelling of Keaton, Lloyd, Lubitsch, and others, something else was happening. During the 1920s, quite a lot of American cinema became dependent on language. This happened, paradoxically, because of what critics then and since called the increasingly “cinematic” qualities of movie storytelling.

Not having either Cradle Snatchers or Upstream available for illustration, here’s an example from a film not playing here. In Henry King’s Winning of Barbara Worth (1926), Holmes the engineer is calling on Barbara before he sets out on a mission. He tells her that he plans to go back east, and he’d like her to join him. He’ll be back in a week for her decision.

At the purely imagistic level, the scene is presented in standard continuity, with a long shot establishing the kitchen, then a series of reverse-angle medium-close shots of Holmes and Barbara as they talk flirtatiously.

The conversation is interrupted by a cutaway to Abe outside, coming in the gate, which serves as a transition to a two-shot of Holmes and Barbara.

It’s from that framing that Holmes leaves, and she lingers at the doorway.

But the scene is even more broken down than this. Of its twenty-eight shots only eighteen are images; the other ten are dialogue titles. They are sandwiched in between the tight singles of Holmes and Barbara, as here:

In effect, breaking the scene down “cinematically” into close views of each character may seem to pull cinema away from theatre. Yet it works to frame and underscore each line of dialogue. The pattern is speaker/ title/ speaker. Even the more distant shots, like the opening establishing shot and the final two-shot framing, are broken up by inserted titles.

Across the 116 seconds of the passage, nearly 36% of the shots consist of dialogue. Of course this proportion wouldn’t be sustained across the whole film, since many sequences are filled with physical action and have no conversation. But in this and many other films American directors were creating a silent-film dramaturgy that incorporated dialogue into the texture of the cutting. Dialogue titles became editing units that could maintain a rapid pace and, combined with legible singles and two-shots, made for cogent storytelling.

This is what happens in Upstream and Cradle Snatchers. They are dialogue-driven vehicles (one a short-story adaptation, the other taken from a play), and both Ford and Hawks, idiosyncratic stylists in other genres and at other times, accept the dominant norms of their moment for these projects. These films employ speaker/ title/ speaker cutting, the singles and firm two-shots, and the careful eyeline matching. In fact, Ford uses a clever “impossible” eyeline match when the ham star looks up from the dinner table and the answering shot shows the distraught Gertie in her room upstairs, looking down, as if at him.

So were films like Upstream, Cradle Snatchers, The Real Adventure, and The Winning of Barbara Worth “preparing” for sound? In the sense of underscoring dialogue, yes. But the detailed breakdown into singles was not the most common option in most talkie scenes, at least in US cinema. (Japan is another story; cf. Ozu’s 1930s films.) The default for most scenes was the two-shot framing, with characters conversing within a sustained shot. This strategy is present at the end of our Barbara Worth scene, and it can be found throughout 1920s cinema. In other words, given the choices already established during the 1920s, sound-era filmmakers usually preferred the two-shot over singles. Accordingly, the cutting rate slowed down in most sound cinema. (The over-the-shoulder shot, a sort of single-plus, was another fairly rare option in the 1920s, but that too came into its own in the talking film.)

As often happens, Hollywood style offers a menu, with some options becoming more common at different periods. For sound filming, directors relied upon what had been an alternative option in the silent era, the two-shot. They saved singles for key moments. Today, with the dominance of what I’ve called intensified continuity, we seem to be back in the late 1920s. Filmmakers are inclined to present a line of dialogue with a tight single of the speaker, as happens in the Ford, Hawks, Vidor, and King films–but this time, of course, sync sound does duty for the intertitles.

This is one of the things that Ritrovato does best—provoke you into seeing new connections and trying out fresh ideas. Of course, it shows you a wonderful time in the process.

Kristin’s 2010 blog entry on Capellani is here. She will update it and write a new one after she’s assimilated the Ritrovato experience. The Variety review of Cradle Snatchers is from 1 June 1927, p. 16. We discuss dialogue intertitles in American cinema throughout The Classical Hollywood Cinema (1985), particularly in the chapters written by Kristin.

Triple play

The Disciple of Hong Kong.

First, if you haven’t yet visited Jim Emerson’s Scanners blog entry on “Geriatric Noir,” you must do it pronto. It confirms once more the spontaneous genius of the American people. We are the world’s very best at smart-alec, disrespectful, shameless humor.

Second, I’ve just received an advance copy of Jac and Johan’s film The Disciple of Hong Kong. It’s an essay on Tarantino’s debt to Hong Kong film. Twitch announced it here, and you can watch the trailer here.

This is a fan’s fever dream. It features interviews with many HK film experts like Roger Garcia and Bey Logan, along with local legends Raymond Chow, Ringo Lam, Simon Yam, and Gordon Liu, below. The movie is a load of fun, with many clever retro touches, and I learned a lot from it.

I wander in from time to time, with probably my most significant line being “Excuse me, do you have any syrup?”

It’s coming up on 26 June on a French channel dedicated to action films. I don’t know exactly when it will be available otherwise. For some clues to the identity of directors Jac and Johan, go here. Frederic Ambroisine, another HK film expert, was involved with the project as well. His site is a remarkable video resource, and he currently writes at actionqueens.com and alivenotdead.com.

Third and finally, Kristin and I are soon off to Bologna’s Cinema Ritrovato. We will be blogging.

Speaking of shameless: To get more of my take on HK cinema, visit the Hong Kong national cinema category below. If you’re really devoted, or just at a loss for how to spend $15, pick up a copy of my e-book Planet Hong Kong.

Rukik Sallé (Mad Movies), Fred Ambroisine, Jac, and Johan. Hong Kong, 2011.

Pike’s peek

The Lady Eve.

DB here:

Hollywood is supposedly making movies for mass audiences, and up to a point that’s true. But there’s an in-group aspect of Hollywood as well. There are moments in the movies when the writers and directors and actors seem to be talking more among themselves than to outsiders. We’re probably more familiar with this nowadays, as when Tarantino and Soderbergh cast Michael Keaton as the same character in both Jackie Brown and Out of Sight. Not only does the gesture suggest solidarity between two directors of roughly the same generation. I think it’s also a sign that the directors respect Elmore Leonard’s concern to let a character from one novel pop up in another.

You see the same attitude in those in-jokes we occasionally find in Hollywood movies. The most famous, I suppose, is Cary Grant’s warning, in His Girl Friday, that the last man who thought he’d beaten him was Archie Leach, “just a week before he cut his throat.” Archie Leach was of course Grant’s real name. In the same film, Grant as Walter Burns tells the platinum blonde Angie to seduce Bruce Baldwin. How will she know him? He looks like that fella in the movies, he says, “You know, Ralph Bellamy.” Angie replies with simple lack of interest, “Oh, him?” Since Bruce is played by Bellamy, this is a little cruel; both character and actor are treated as losers.

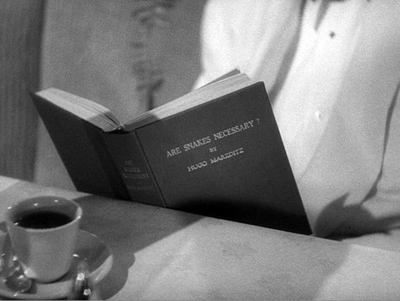

Preston Sturges liked such playfulness, as when in The Lady Eve (1941) he used his birthday as the date on a check. In the same movie, the protagonist reads a book called Are Snakes Necessary?

No such book exists, more’s the pity. The title pays comic reference to James Thurber’s 1929 best-selling satire on marriage manuals, Is Sex Necessary? and confirms the snake-as-phallus imagery that isn’t exactly underplayed in the rest of the film. Sturges revisited the gag phrase when he proposed Is Marriage Necessary? as the title for a later picture. Unsurprisingly, it didn’t pass the censor, and instead we got a more anodyne title, The Palm Beach Story (1942).

These are comedies, though. On Saturday night, I saw an instance of in-group crosstalk where I hadn’t expected it. The Long Night (1947) is Anatol Litvak’s somber remake of Le Jour se lève. Unlike Hawks and Sturges, Litvak wasn’t exactly known for cockeyed humor, nor was screenwriter John Wexley (The Roaring Twenties, City for Conquest, Hangmen Also Die!). Yet in one shot, there it was, a citation as plain as a pikestaff.

Over several years I’ve been gathering material for a blog or web essay on product placement. (I’m mostly in favor of it.) So I tend to scrounge around among hand props and other bits of flotsam in the frame, hoping to catch a brand name. Usually this task-driven visual search comes to naught, but The Long Night paid me back.

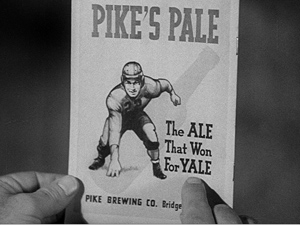

In Sturges’ The Lady Eve, you’ll remember, Henry Fonda plays Charles Poncefort Pike, heir to the vast fortune of the Pike brewery. The firm’s success rests upon Pike’s Pale Ale. A flyer for the product convinces Jean and her father that Charles should be the target of their next con job.

Pike’s Pale and its tagline run through the movie as a comic motif. But no such product then existed. It features on a list of fake movie products in a 2006 New York Times story.

All the more surprising, then, is a scene in The Long Night six years later. The rapacious magician Maximilian (Vincent Price) takes Joanne (Barbara Bel Geddes) to a symphony concert. She reads the program avidly, and on the back we can glimpse a familiar brand.

The advertisement even features the same text and layout as the flyer in Sturges’ film.

If it’s an in-joke à la His Girl Friday, what’s the punchline? And how did it even get there? We have two different studios (Paramount, RKO) and different genres (satiric romantic comedy, gloomy romantic drama). Was the ad just lying around a props warehouse? Did Fonda, who plays the hero of The Long Night, keep the flyer as a souvenir of The Lady Eve and ask the producers to include it as a shout-out to Sturges? Was there a company specializing in making printed props for the studios and here it just recycled something it had done for Paramount? Or is it just a case of Hollywood gratuitously referencing itself?

I’d be eager to hear from anybody who knows or has an educated guess. In the meantime, I’ll keep scanning frames, and being diverted by the ways that the Hollywood In-Crowd creates a world of off-center echoes and cross-references. It’s as if movies fertilized each other, but promiscuously, creating an eccentric world behind the screen, where stray images and lines of dialogue jostle against one another. Of one thing we can be sure: It will be unpredictable.

Today there is a real Pike’s Pale Ale. The proprietors of Seattle’s Pike Brewing company didn’t know about The Lady Eve when they conjured up their brew. I’ve never tasted it, but you might count this a case of blog product placement. Mmmmm, pale ale….

Ian Patrick displays an imaginative gouache called “Are Snakes Necessary?” here.

Incidentally, The Long Night is another of those 1940s movies with a flashback within a flashback, of the sort I considered in an earlier post.

I top and tail the entry with pictures of Slim because he looks swell when he’s thinking.

The Long Night.

PS 19 June: Rapid Response Dept: Alert reader Sean Weitner points out the reappearance of the same newspaper page in a bevy of TV shows. The evidence is here. Thanks to Sean!

PPS 21 June: More bulletins from alert readers. Leo Rubinkowski points out the source of the recurring newspage on Slate here. This wouldn’t, I think, explain the reappearance of Pike’s Pale, but maybe…. Andrea Comiskey has found that Douglas Sirk was apparently fond of certain foil-etched items. The films are All That Heaven Allows and Written on the Wind, and the pix are here and here and here and here. Leo and Andrea are UW grad students, so I’m especially happy to thank them.

Julie, Julia, & the house that talked

Enchantment.

DB here:

For the last couple of decades, American filmmakers have been exploring storytelling options that break up timelines. Flashbacks are the most obvious examples, but so too are time-travel and parallel-universe stories; Source Code was a recent example, which I talked about here. Elsewhere I’ve mentioned that these new formats revive narrative innovations that we find in 1940s Hollywood movies—the topic of my course at the Zomerfilmcollege in Antwerp in July. While planning that course, I’ve come up with an intriguing pair of movies that can tell us something about how the romance film, drama or comedy, handles a couple of features of storytelling we probably don’t think enough about.

When parallel lines meet

Julie & Julia.

What is a story made of? Minimally, characters and their doings. Some theorists of narrative offer a more abstract description. Stories, they say, consist of agents (characters) who exist in states of affairs (John was married to Mary) and who perform actions (John tried to divorce Mary). Still talking abstractly, a narrative organizes the agents’ states of affairs and actions according to certain principles.

Principles of time, indicating sequence and duration. John married Mary, then after a while he tried to divorce her. Some theorists think that ordering events and states of affairs in time is the essential feature of narrative.

Principles of causality. John is tried to divorce Mary because he fell in love with Audrey. Perhaps not all narratives exhibit causality, but most surely do.

Principles of space, a place in which the story unfolds. John met Mary at the supermarket and they fell in love at the beach, but at work one day John was introduced to Audrey, the new head of his department and they had coffee at Starbucks…. Some stories rely on a very specific sense of locale (e.g., a tale of a man buried alive), while others evoke the environment rather vaguely (as in jokes beginning with a priest, a rabbi, and a minister walking into a bar).

These core ingredients look very general, but they can be good guides in starting to analyze a story. We can ask how time is organized, what causes what to happen, and how space is patterned, and the answers can reveal intriguing things about the way the narrative works.

There’s one more principle worth remembering. Most narratives involve parallelism. That occurs when characters, situations, actions, or other factors are likened to or contrasted with one another. (I don’t say “compared or contrasted” because “comparison” means pointing out both likenesses and differences. Call me fussy.) So our hypothetical tale might include another man, John’s friend Jack, who lives a happy married life with Jill. In fact, romantic comedies often include subplots, as when we get a secondary love affair between friends of the main couple. Serendipity, discussed in another blog entry, is a straightforward instance.

Sometimes a filmmaker can create an entire plot out of parallels. Griffith did it in Intolerance, drawing comparisons among different historical epochs. More common is the film that gives two or three protagonists equal weight and likens or contrasts their situations. In Wedding Crashers, John’s romantic pursuit of a woman is counterpointed with the raunchier efforts of Jeremy to escape a woman pursuing him. Kristin has proposed that some plots create “parallel protagonists” who pursue separate goals but converge because one of them tries to meet the other, as in Desperately Seeking Susan and The Hunt for Red October. And in what Variety calls “criss-crossers,” or what I call “network narratives,” many characters become fairly salient as they intersect, and each can be compared to another. Examples would be Grand Hotel, Tales of Manhattan, and Love, Actually, which depend largely on contrasts.

Kitchen stories

Julie & Julia.

So parallelism can operate at greater or lesser strength, as a minor accessory to the flow of time, causality, and space; or it can become a firmer principle shaping the story.

This sort of firming up is visible in Nora Ephron’s Julie & Julia. We have two sets of characters in two time frames: Julia and her husband Paul in the late 1940s and 1950s, and Julie and her husband Eric in the early 2000s. The two stories are crosscut, so that we alternate between them as each one develops.

What links them? Most explicitly, some causal factors. Julie is dissatisfied with her thankless job. Since she loves to cook, she decides to devote a year to trying all the recipes in Julia Child’s famous Mastering the Art of French Cooking. At Eric’s suggestion she writes a blog chronicling her daily efforts, and gradually she finds an audience, eventually making her a celebrity. So Julia’s cookbook becomes a central cause in changing Julie’s life.

What about Julia? In her postwar plotline, she is also unfulfilled in her career, but she loves to eat. She learns French cuisine and revels in creating elaborate dishes. At the urging of Paul, she collaborates with two friends in writing, and eventually publishing, a cookbook for “servantless” American housewives. So Julia’s efforts are presented as another chain of cause and effect.

The parallels are obvious. Both women turn to cooking in search of personal fulfillment. Both take up writing, to share their knowledge and experiences with others, and both become published authors. Both have supportive husbands who inspire them. The film is about love, but each couple’s bond isn’t threatened by an outside figure, as in other romance films. Their bond is strengthened by the love of food, not to mention good-hearted sex.

Some more detailed parallels emerge as well. There are spatial contrasts: Julia is exhilarated by Paris and their lush apartment, while Julie’s depression is deepened by their cramped Queens walkup, perched above a pizza joint. Both Julie and Julia encounter initial disappointment in their efforts to reach an audience. Julie’s blog initially finds only her mother as a reader, while Julia’s manuscript is at first turned down by publishers.

Both couples enjoy sharing their food with friends, although Julie’s college pals, now self-centered businesswomen, aren’t as supportive as Julia’s writing partners. Both couples undergo a strain, with Paul being interrogated by McCarthyite politicians and Eric made annoyed by Julie’s growing obsession with Julia and the blog’s readership. Even specific motifs, like butter, lobsters, and boning a duck, draw out parallels between the two heroines. Montage sequences highlight the linkages, as when pairs of shots show both women cooking and tasting the same dishes.

Julie in fact becomes what Kristin in Storytelling in the New Hollywood calls a parallel protagonist. Often in such plots, one protagonist becomes fascinated with the other, as Salieri gets obsessed by Mozart in Amadeus. Julie is captivated by Julia’s charisma, to the point of wearing her signature pearl necklace.

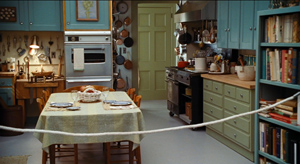

Julie and Julia never meet; it’s hinted that in her old age Julia is miffed by Julie’s blog. Yet the plotlines meet in a spatial parallel. Julie and Eric visit the Smithsonian reconstruction of Julia’s kitchen. He takes a picture of it.

After they’ve left, the display shifts into an image of the original kitchen, where Julia and Paul get the news that her book has been printed. The scene finally conjoins the couples and reaffirms each woman’s success and each man’s pleasure in it.

Two times in one space

Two times blend within a single domestic space in another movie built out of parallels, Irving Reis’s Enchantment (1948). Again the action plays out in different eras: a turn-of-the century story of love and jealousy within the Dane family, and tale of awkward courtship set during the blitz.

In the first story, the widower John Dane adopts an orphan girl, Lark. After his death, the eldest daughter Selina rules the house, coddling her brothers Pelham and Rollo but treating Lark like a servant. Once they have grown, both men come to love Lark (Teresa Wright), and she reciprocates with love for Rollo (David Niven). Selina blocks their union through several stratagems, relying partly on Rollo’s reluctance to challenge her, and Lark leaves to marry an Italian count. She becomes the great lost love of Rollo’s life.

An old bachelor, Rollo lives in the family home until his grandniece Grizel (Evelyn Keyes) arrives from America, posted to help the British war effort. Grumbling at first, Rollo eventually comes to enjoy having her in the house, especially when Grizel attracts the attentions of a Canadian flyer, Pax (Farley Grainger). She fends him off, on the grounds that she’s already been hurt in love once and doesn’t want to risk it again. At the climax, as a bombardment begins, Rollo urges Grizel to go to Pax. He says, acknowledging his wasted life, that if she loves him, she can’t wait a moment; things can change in an instant.

In effect, Rollo acknowledges the parallels between the two generations, seeing Grizel on the verge of making his mistake. “Don’t stop to bargain for happiness.” Grizel races out and finds Pax as the bombs fall. She achieves the happiness that Rollo foolishly lost. Back at the house, Rollo is killed when a bomb strikes the house.

I’ve presented the two plotlines sequentially, but like Julie & Julia, the film alternates them, treating the distant past as flashbacks from the wartime drama. Like Ephron’s film, Enchantment puts the climaxes side by side. The big scene of Rollo’s losing Lark to the count is followed immediately by the climax in the present, when Pax declares his love, Rollo advises Grizel to follow him, and the house is damaged, though not destroyed, by the bombardment. Again, there is a basic causal link between the eras, this time based on kinship: because Grizel is a relation she bivouacs with old Rollo. The parallels are likewise highlighted by motifs, not least the necklace that Rollo gave Lark as a pledge of love. She returned it as she departed, but after he has come to love his great-niece, he gives it to her as a token of her happiness. “She wore it one night. You’ll wear it a lifetime.”

Enchantment is based on a novel by Rumer Godden, probably best known to cinephiles as the author of Black Narcissus and The River, both turned into extraordinary films. The novel, Take Three Tenses: A Fugue in Time (1945), has a more complicated parallel structure than Reis’s film. It creates several time zones: the marriage of Dane senior and his frail wife Griselda; the growth of their children; their young adulthood; and the blitzkrieg period we see in the film. In addition, as perhaps a redundancy device, the central male is given a different name at different stages: Rolly as a child, Rollo as a young man, and Rolls as an old man.

Enchantment is more conventionally focused. Griselda is a central character in the book, but the film drops her and picks up the family saga after her death. Even then, it devotes only four short scenes to the childhood of the siblings. The result is to concentrate on the youthful Rollo-Lark romance, but it loses a string of parallels involving courtship and marriage, particularly the contrast between Grizelda and her modern namesake.

In a mildly experimental gesture characteristic of much popular fiction of the forties, Godden’s novel treats time in an unusual way. The World War II scenes are given in the past tense, but all the earlier periods are rendered in the present tense. So you get passages that mix different eras.

Proutie took it up to Rolls in his dressing room, where Rolls was sitting.

“The post, Mr. Rolls.”

“Go away,” said Rolls. “Leave me alone.”

Proutie put the letter on the table at Rolls’ elbow and went away.

Years before there is another letter, a letter written by Rolls in answer to many letters of Selina’s.

She reads it in her room sitting in the blue-and-white armchair on which this afternoon, dressing to have tea with Pax, after she had been asleep, Grizel tossed down her pyjamas and left, standing by it on the rug, a pair or swansdown slippers that she called her “scuffs.”

Selina as a girl has a swansdown muff, dyed violet with a rose in it, but she keeps it tidily in tissue paper in the cupboard; she does not throw her things about nor leave them on the floor. As she reads Rolls’s letter, Selina is not a girl; she is an elderly woman and that day she feels old. You ask me, Lena, why I don’t come home. That is a question that is rather difficult to answer. I seem to have a distaste for the house.

Call it dumbed-down Proust or Faulkner if you want. In any case, the fluid shifts from past to present are given not only through adjustments of tense but also by emblematic objects, like the letters and the swansdown accessories, that lead us, stepwise, through time. It’s almost as if Godden were mimicking cinematic technique, dissolving from one image to another (letter to letter, slippers to muff).

The film picks up the hint and does sometimes dissolve from the present to the past. More original, and perhaps closer to the seamless uniting of periods, is the way the narration revives a rare device. In Caravan (1934), the returning Countess Wilma turns to her old governess, asking if she remembers the last day she was in her bedroom. The camera pans left to the governess, who gets a faraway look in her eyes.

Then she scrunches up her face and commands Wilma to come to her. Pan right to Wilma, now a child, in a tantrum.

Interestingly, the whole flashback is played in this one shot, ending on the governess recalling the scene and tracking back to a full shot of the grown-up Wilma.

Similarly, several Enchantment transitions are handled in a single shot, but here the panning movements typically highlight enduring parts of the house. Old Rollo has grudgingly let Grizel stay in Selina’s bedroom. As Rollo says, in an auditory flashback, “There’s no such thing as an empty room,” we see Grizel at the dressing table. The clock stops and as she puts it up to her ear, she looks screen right.

The camera pans to the door, with a maid calling, “Miss Selina,” and then pans back to show Selina as an adolescent at the dressing table.

Nearly all of these single-shot transitions pivot around items that have remained in the house over the years, like a clock or a chandelier or the central staircase. These reflect passages in Godden’s novel that itemize household furnishings across the years or use them to tie together two scenes in different years.

No such thing as an empty room

While speaking of those years, I’ve oversimplified a bit. In Take Three Tenses, even the World War II era, the most recent setting of the action, is enclosed in a frame given in what we might call the persisting present. The book begins:

The house, it seems is more important than the characters. “In me you exist,” says the house.

There follows a past-tense account of the elderly Rollo’s learning that his family’s lease on 99 Wilshire Court is up. Then we have a several-page tour, in the present tense, of the house from top to bottom. It’s launched by this sentence:

In the house the past is present.

Moreover, Godden takes literally the house’s claim that “In me you exist.” She confines all the novel’s directly presented action to the building. What happens outside, we learn through reports. At the book’s end the opening tour is echoed in miniature. There various lines of dialogue from all periods mingle, and the narration insists that the house will endure “in its tickings, its rustlings, its creakings” and ends “In me you exist.” So the house, past, present, and future, enfolds all the dramas played out in it.

The sovereignty of domestic structure is provided by the novel’s chapter structure, which, after an initial “Inventory,” presents “Morning,” “Noon,” “Four o’Clock,” “Evening,” and “Night.” The headings gather only scenes taking place at the named time of day, though the scenes are gathered freely from across many years. (Take that, Alan Ayckbourn.) The fugal voices come together at these nodal points. Once again, the house sets the rules, the household routines being more important than a chronological or causally-driven time scheme.

Godden’s effort to suggest layers of the past in any room or time of day is difficult to capture on film. Perhaps Richard McGuire, working in the medium of comics, comes closer with his famous 1989 piece “Here.” A room’s corner is invaded by events from many periods.

An approximate cinematic equivalent is Ivan Ladislav Galeta’s Two Times in One Space (1976/1985), with a time delay that creates ghostly figures from moments 219 frames apart.

Only the room remains stable in this out-of-phase presentation of a meal prepared and eaten. (Perplexingly, the action on the distant balcony unfolds in standard duration.)

Galeta’s version isn’t an option for a classical Hollywood film like Enchantment. The closest analogy comes during a parallel between Rollo as a young officer out to meet Lark, and Pax as he hurries to meet Grizel. A graphically matched dissolve puts Pax in Rollo’s place.

This device, however, doesn’t convey the persistent presence of the house. Enchantment finds another way to shelter its interchange between past and present. It lets the house talk.

As the film opens, the camera approaches 99 Wilshire Court and the house introduces itself to us in voice-over commmentary. “You almost passed me.” The house invites us to “see what the mirrors have seen.” It turns mournful. “I miss my people. In me they live.” The camera coasts through empty rooms, as we hear voices welling up from different parts of the past.

We don’t know the speakers yet, but the device prefigures the dramas to come, as well as suggesting Godden’s idea that the house endures as a repository of fugitive, phantom life. As the camera reveals Rollo talking with his solicitor, the voice-over explains, “The house is his story.”

Although we might not recognize it on first viewing, this is another single-shot flashback, since in the initial present, that of the deserted house, Rollo is already dead. The narration is taking us back to the opening phase of the wartime plotline.

Trimming back Godden’s ensemble plot, the narration gives us a protagonist and identifies what happens to the house with what has happened to him. Yet the house takes precedence, in that the flashbacks aren’t triggered by his or anyone else’s memory. This is rare in classical cinema of the period, which usually motivated returns to the past by someone recounting or recalling earlier events. It would be too glib to say that these flashbacks are “the house remembering,” but the fact that transitions are more objectively anchored than usual does yield a sense that time has a shape that we sense more acutely than the characters can.

Subjectivity does enter, at least apparently, in Rollo’s imaginary dialogues with Lark. At various points she speaks to him in imagination, or in some realm the lovers share. Again, though, we can’t ascribe those voices to his mind. After he has been killed, the camera tracks back from his body.

As in the beginning, voices haunt the parlor. During the camera movement the young Lark asks, “We shall always be in love, won’t we?” “Yes,” Rollo replies. “Even when we’re old?” “Even when we’re old.”

The film doesn’t confine its action as strictly to the house as Godden’s novel does. We follow Grizel to her job at the military post, and the young Rollo to a shop to buy Lark a necklace. Nevertheless, the sense of enclosure, not to mention closure, is provided after we’ve seen Rollo felled by the German bombardment. The camera continues backward, through a window as the house’s voice-over narration assures us that no story really ends. The house seems to have cheered up in the course of the narrative; no longer missing its people, it looks forward to a new generation. Echoing the future-oriented ending of Take Three Tenses, the house concludes: “In me, the young will live again, with the heart’s lease on life.”

Sometimes we expect that recent films will be more complex than older ones, and that’s often true. But an older film often turns out to have more angles than we get nowadays. Julie & Julia is an amusing and touching entry in the American Cinema of Quality. (Is Scott Rudin today’s Samuel Goldwyn?) And it’s true that Enchantment doesn’t multiply its parallels as ingeniously as Julie & Julia does. Yet Ephron entertains us with clever reiterations of the basic comparison of the two women, given in the title anyway. Enchantment avoids such detailing in search of a wider emotional range.

Julia is admirable, and Julie grows by imitating her, but their stories don’t carry the bittersweet resonance of the stories of Rollo and his descendants. You can argue that Enchantment softens some of the novel’s harsher side; there Rollo loses Lark by prevaricating, while in the film he is partly the victim of bad luck. (The trains stopped running.) Even so, the film preserves the severe self-denial we find in Grizel, who sees her fear of passion as “the Dane vice,” and the bitter self-reproach of the lonely Rollo. Then there’s the house as a wise reliquary of human lives, humming with voices from the past. Julie & Julia makes its locales simply part of many tidy parallels. Enchantment lives by comparisons too, but it also lets space come forward as a factor that can, at least momentarily, become as engaging as other dimensions of storytelling.

The approach to narrative theorizing I started out with is, roughly speaking, action-oriented. The ideas of time, causality, and space emerge logically out of a concern with how the plot lays out its arcs of action. An alternative approach, no less fruitful, is agent-oriented. It treats action as secondary to the portrayal of character traits and psychological activity. The agent-centered perspective is especially useful for studying narratives in which the characters seem larger than life and their vividness exceeds their role in the narrative patterning (in Dickens, for instance), or when there is very little external action (as in Beckett). The classical narrative tradition of Hollywood, despite its powers of characterization (helped out by the star system), seems to me to to concentrate most on organizing action. There plot is usually primary. And there’s nothing wrong with that!

For more on flashbacks and their degrees of subjectivity, see “Grandmaster Flashback” on this site.

My quotation from Take Three Tenses: A Fugue in Time (Boston: Little Brown, 1945) comes from p. 174. John R. Frey argues that the tense shifts in the novel are actually more subtly discriminated than I’ve indicated. Godden uses, he claims, the present and the imperfect for the main action and the perfect and the past perfect for the flashbacks. See “Past or Present Tense? A Note on the Technique of Narration,” The Journal of English and Germanic Philology 46, 2 (April 1947), 205-208.

Promoting space as a narrative factor, rivaling time and causality, is something Kristin and I have written about in various places. See in particular Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema, Chapters 6 and 7.

A short film inspired by McGuire’s “Here” is, well, here. Chris Ware, who wrote an essay, “Richard Mcguire and ‘Here’–A Grateful Appreciation,” Comic Art no. 8 (2008), 4-7, seems to have been inspired by it in certain installments of his Building Stories; also try here, searching under “Building Stories.”

Galeta’s Two Times in One Space is available on this DVD collection of his works.

Julie & Julia.