Archie types meet archetypes

Wednesday | September 2, 2009 open printable version

open printable version

DB here:

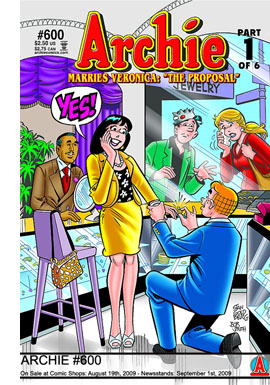

You heard about it in May, but the proof arrived in comic-book stores just lately. Archie has proposed to Veronica. At the midpoint of issue #600, he goes down on bended knee in Spiffany’s and pops the question.

The rest of the issue is devoted to other characters’ reactions. Mr. Lodge, at first outraged, says that Archie must come to work for him. Jughead is judgmental but ultimately forgiving, in his droopy-eyed way. Archie’s parents are delighted. Even Reggie shows a dash of gallantry. All of Riverdale is buzzing, but over the joyous news hangs a cloud of worry.

What about Betty?

She accidentally witnessed the proposal and at first broke down uncontrollably. Later we see her as surprisingly stoic—until she gets a phone call from Veronica (cruel? compassionate?) asking her to be maid of honor. The installment ends with Betty forlornly telling Veronica, “You—you won.”

She accidentally witnessed the proposal and at first broke down uncontrollably. Later we see her as surprisingly stoic—until she gets a phone call from Veronica (cruel? compassionate?) asking her to be maid of honor. The installment ends with Betty forlornly telling Veronica, “You—you won.”

DON’T MISS THE STORY THE WORLD HAS BEEN WAITING MORE THAN 60 YEARS TO READ! we read on the last page. Part Two, “The Wedding,” will follow next month, with four more parts after that. Archie Comics Publications has promised future episodes in which Arch and Ronnie procreate.

On her blog, Veronica is more or less gloating. Betty seems to have come to terms. On her blog she wrote:

What can I say? It is so sad.

Xoxoxoxo

Bets

Still, Betty suggests she feels the sting of mockery, and we can expect more pain in her future. Fan reaction has been far more furious. Mackenzie writes:

ARCHIE SHOULD HAVE MARRIED BETTY!! I MAY ONLY BE 10 BUT HE MUST MARRY BETTY. HOW COULD HE BE SO STUPID. I THINK HE IS TRYING TO BE RICH. POOR POOR BETTY.

One devotee, proprietor of a comics shop, sold his copy of Archie #1 in protest, and the $38,000 it fetched has not assuaged his discontent.

Like all boys I knew, I preferred Betty to Veronica. So I join in the mourning, and not just because it promises a sad married life for Arch. This upheaval threatens to destroy the Riverdale we loved. Betty working in a shop in Manhattan, Reggie in Atlanta selling cars, Moose running a burger joint in Staten Island: All dismally realistic options for today’s grads, but that’s small consolation. And what about Miss Grundy and Mr. Weatherbee and Pop Tate? Have we no cares for them?

In this crisis, panic is understandable. Yet I believe that older heads have a duty to assume leadership and calm the younger, more tempestuous spirits. A careful reading—well, okay, just a simple reading—of fateful issue #600 gives us a glimmer of hope. It also illustrates how a very old narrative convention can be revamped in popular culture.

A man of many parts

My acquaintance with the Archie series goes back to the mid-1950s. The books had already moved from the 1940s caricatural portrayal of Riverdale’s residents (above) to a more streamlined look reminiscent of Hergé’s clear line style.

Eventually the visual style would become still more minimal, offering little shading or detail and relying on a smaller repertoire of facial types, expressions, and gestures.

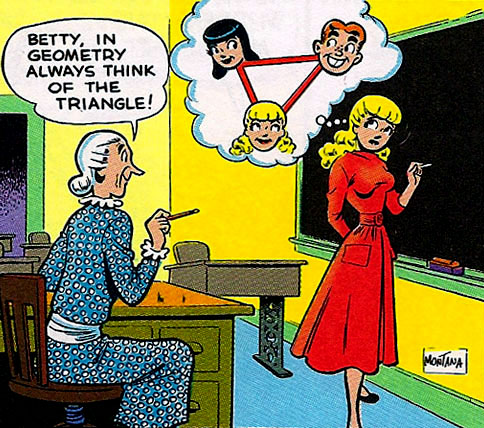

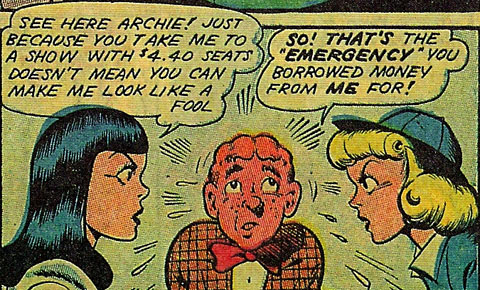

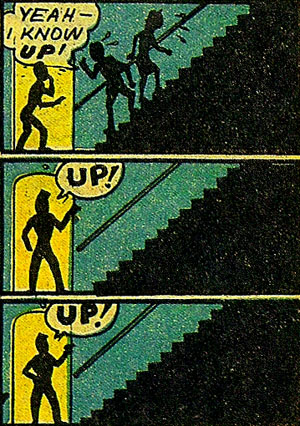

What I didn’t know then was that the first series artist, Bob Montana, was a gifted storyteller who made shrewd use of the graphic shorthand that adds so much to comics. In “Double Date” (#7, 1944), the issue that established the Eternal Triangle, Archie has wound up taking both girls to the same play. Of course neither knows that her rival is there. Archie escorts each one into the theatre and then races between Veronica in the orchestra and Betty in a distant balcony. Montana crisply renders Archie and Betty climbing past ushers to the nosebleed seats. Interestingly, this stack of panels must be read from bottom to top.

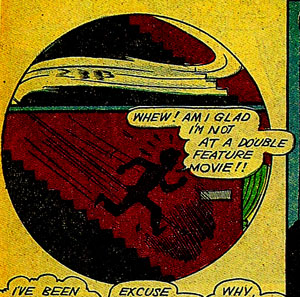

Archie races downstairs to check in with Veronica, and the swirl of his descent wraps inside the circular frame like baseball stitching. A horizontal stripe using the vertical panels’ green tone demarcates the movement between floors.

Once Betty discovers Archie’s perfidy, she stalks off, and Montana combines the two earlier framings, circle and square, yellow and green, in showing their zigzag descent.

Morover, in a story based on symmetries, each girl’s discovery of Archie’s perfidy is given a canted deep-focus framing that Orson Welles might have liked.

I wish I could find this sort of pictorial ingenuity in Archie #600, but like most of the 1950s and 1960s entries I’ve reread, this one is all about story. And fairly comedy-free story at that. Years ago boys like me followed Archie, but I suspect that now the prime readership is tween girls, so the romance-based pathos of Betty’s suffering may hit its target audience. Still, what the issue lacks in graphic sophistication may be made up for in its use of a narrative device that has become salient in popular culture, including movies.

The road not taken

In Poetics of Cinema I included an article called “Film Futures.” Originally a paper for a 2001 conference, it sought to analyze an emerging trend in filmic storytelling that has its roots in folktales and popular literature. That is the device of the hypothetical future.

The most famous example in literature probably remains A Christmas Carol, in which a ghost confronts Scrooge with a harrowing vision of his fate if he does not mend his ways. Dickens’ story showed how an alternative-future plot could be motivated by the supernatural, still a common way to show an alternative course of events. Later writers would rely on hallucination or science-fiction premises, such as time travel that allows a return to a point of choice. At various periods, films have drawn on these principles, from The Love of Sunya (1927) to Back to the Future II (1989). There are unmotivated instances of alternative futures as well in plays by J. B. Priestley, novels by Allen Drury, and art-comics by Chris Ware.

The central premise of this device goes back further. Many folktales from various cultures present brothers halting at a crossroads. Each brother picks a different road, and the plot is built out of their contrasting fates. Sometimes each road is marked with an enigmatic prediction about what will happen further along. O. Henry picked up the motif in his audacious 1903 story “Roads of Destiny,” which presents a single protagonist hypothetically taking each path in turn. His fate catches up with him whether he chooses one road or the other or just returns home.

In my essay I explore how the idea of forking-path futures was revived on film in Kieslowski’s Blind Chance (1987), Tykwer’s Run Lola Run (1998), Peter Howitt’s Sliding Doors (1998), and Wai Ka-fai’s Too Many Ways to Be No. 1 (1997). The essay aims to show how this plot formula, so apparently free-form, relies on a set of firm conventions. For example, in principle the character might have an indefinitely large set of fates, but the first parallel universe presented sets the premises–characters, issues, and the like–that will be varied in the other alternatives. The conventions, I argue, allow the filmmakers to establish a surprisingly narrow set of options, but this trains us to notice fine-grained differences.

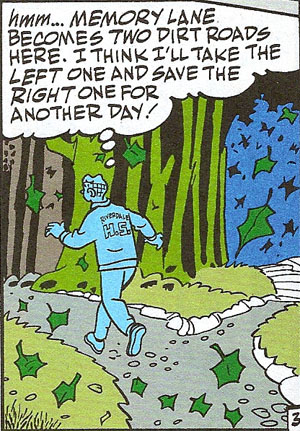

Archie’s proposal to Veronica, we learn, takes place in just such an alternative future. The present time of the narrative in issue #600 is the night of Archie’s last high-school rock concert. But Archie, facing the need to apply to college, goes out for a walk. He arrives at Memory Lane. Instead of walking down the lane—that is, into the past—he walks in the opposite direction, into the future. Suddenly he’s encountering his parents on the night of his graduation from college. A title intervenes.

Stop the presses! Did Mr. Andrews say Archie was graduating from COLLEGE? What happened to HIGH SCHOOL? By walking up Memory Lane, has Archie walked into his own FUTURE?

In short, yes. Everything we encounter from here on takes place four years after the initial scenes. Archie’s proposal and Betty’s fraught response are set in the future, as presumably will be the wedding and the eventual birth of Archie’s and Veronica’s children.

Already, then, there’s a way to set things right in Riverdale. That’s to change the future, to treat it as only one possible line of action. And in taking Archie up Memory Lane our plotters have relied on the folk archetype I’ve just mentioned.

This is quite a tease. The motif of pairs that we saw in “Double Date” returns with a vengeance. (A propos, it’s announced on the Internets that Archie and Veronica will have twins.) More important, the presence of a second road suggests that Archie has another future, one in which he doesn’t propose to Veronica. This device allows Arch to retreat at any time back along Memory Lane, and then back to the choice-point. Maybe there he will take the “right” road and eventually choose Betty? And is it an accident that the road on the left, drawing him toward marriage to Veronica, takes him into a gloomy forest, while the other one, paved in white stones, leads to a blue sky?

So the narrative leaves an escape hatch: Arch could retreat to this fork. Or he might even decide that he doesn’t want to know his other fate. In which case he could go back down Memory Lane, pass the point he entered, go further back in time, and return to his high school days, putting college—Archie a history major?—into a fuzzy future. But plot it yourself. Or follow the developments through the next five months.

Archie #600 may be offering its young readers a tutorial in understanding alternative-future plots–hence the redundant explanations in the panel quoted above. Historically,though, it’s behind the curve; the recent vogue for forking-path plots seems to have passed. Why did such plots become more common around the turn of the last century? We might invoke Steven Johnson’s argument, in Everything Bad Is Good for You, that audiences got smarter, so narratives became more complicated. Other students of “puzzle films” want to trace such narrative hijinks to postmodernity; no surprise there.

My own explanations can be found in the essay, where I look to factors like modern media’s intense demand for novelty, the quick spread (and exhaustion) of narrative innovations, and most specifically the conventions of storytelling established in things like branching-tree video games and the Choose Your Own Adventure books. Whatever the causes, at any point in history, very old narrative techniques lie waiting to be dusted off and given a fresh polish in the popular arts. Even Archie, going on seventy and still technically a bachelor, can get a makeover.

Archie Comic Publications has its website here. The story “Double Date” is reprinted in Charles Phillips, Archie: His First 50 Years (New York: Artabras, 1991), 34-44. An early published version of my “Film Futures” piece is here via library access, but the revised and expanded version in Poetics of Cinema is preferable. The “choice-of-roads” device is N122.0.1 in Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index of Folk Literature. It is discussed in Archetypes and Motifs in Folklore and Literature: A Handbook, ed. Jane Garry and Hasan El-Shamy (Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe, 2005), 333-341.

P.S. 14 August 2010: Archie’s multiple futures were only the beginning of a major rebranding effort.

P.P.S. 23 January 2017: Turns out that Forking-Paths Archie was a turning-point for both the hero and the company. See this fascinating Vulture story.