Tuesday | September 29, 2020

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs (2020).

Kristin here:

Among the always bounteous offerings of the Vancouver International Film Festival, my favorite section is “Panorama,” since I enjoy seeing new films from countries all around the globe. Often some of these are from Iran, and the two Iranian films featured this year did not disappoint. The sole Indian film turned out to be an engaging, imaginative tale from an area of the world seldom represented on the screen.

There Is No Evil (2020)

Vancouver is in part a festival of festivals, drawing upon international films already premiered in Berlin, Cannes, Rotterdam, and other earlier festivals. Of necessity, this year’s items come from the pre-Coronavirus festivals, with films from Berlin especially prominent in the schedule. Mohammad Rasoulof’s There Is No Evil, Golden Bear winner as best film, continued the director’s regular contributions to past Vancouver festivals. (For entries on other Rasoulof films we have seen at Vancouver, see here and here.) Christian Petzold’s Undine, discussed by David in the previous entry, won the Silver Bear as best actress for Paula Beer.

There Is No Evil is a deeply ironic title, since its four self-contained episodes deal with one of Iran’s notorious evils, its record for executing its citizens. As Peter DeBruge pointed out in his Variety review, “According to Amnesty Int’l statistics, Iran was responsible for more than half the world’s recorded executions in 2017. The number has since dropped, but the country continues to kill its citizens at alarming rates.”

Often the process of carrying through executions is assigned to hired civilians or is forced to be performed by soldiers. Rasoulof explores various ways in which such executions affect the willing or unwilling people who carry out the orders, as well as the effects on people they know and love. I don’t want to spoil the slow development of these consequences for the characters by describing the plots of each of the four episodes in too much detail. Suffice it to say that the revelation of those consequences are worked up to very slowly and occur dramatically.

The four episodes are shot in quite different styles. Those styles are to a considerable extent determined by the fact that the episodes move to increasingly remote locales.

The first begins in a bustling city and is shot in a bright, ordinary style befitting the depiction of a bourgeois lifestyle, with appointments to pick up spouses and children, shopping trips, and alternately bickering and affectionate conversation.

The second episode abruptly switches to a gloomy, desaturated color scheme of grays and muted browns and greens suited to a film noir (above). This segment begins with a military man assigned to perform an execution panicking because he cannot face killing anyone. During this episode, the tone and even the genre switch abruptly twice, from film noir to thriller to … something else.

The third story has a soldier on leave visiting a family of old friends, including the daughter whom he loves and hopes to become engaged to. Here the film is done in a lyrical, bright style, emphasizing scenes in the lush woods and in the happy rural home of a couple who foster a group opposing the government. Here the soldier talks with the mother of the family.

The fourth episode centers on a couple who have retired to a bee-keeping farm in a remote, mountainous area. They must contend with the visit of a niece, but neither is willing to answer her questions about the past.

I think the style in this part pays homage to Abbas Kiarostami, with numerous shots of the couple’s pickup on winding country roads (see bottom). There’s a specific echo of The Wind Will Carry Us in the motif of the girl’s repeated attempts to find cell-phone coverage to call her parents abroad.

Given the relatively large cast and considerable number of interior and exterior locales, one might wonder how Rasoulof, under an order to stop filmmaking, could make a two-and-a-half hour film critical of government policy. DeBruge’s review, linked above, also comments: “By subdividing the project like this, Rasoulof was able to direct the segments without being shut down by authorities — who are more carefully focused on features — and, in the process, he also builds a stronger argument.” In an earlier Vancouver report, we noted that Rakhshan Bani-Etemad’s Tales (2014) used a network-narrative structure because she could only get permission to make a series of shorts–which she then wove together into a feature.

As DeBruge writes, the reliance on episodic structure does not handicap Rasoulof. The slow accumulation of indifference, regret, and guilt demonstrates that executions have unnoticed, unforeseen, and undeserved effects. The stylistic shifts emphasize the differences in those effects and maintain interest across a long film.

The effectiveness of Rasoulof’s film has not gone unnoticed, however, and a Golden Bear is clearly not enough to protect him. On March 4, he was summoned to begin serving his long-delayed prison term, despite the widespread incidence of COVID-19 in Iranian prisons. (On March 1, three days before the summons, Indiewire published a history of government strictures on Rasoulof.) Many official protests have been launched, and one can only hope that once again the result will be yet another suspension of the enforcement of the sentences against him.

Yalda, a Night for Forgiveness (2019)

Yalda is the second feature by Iranian director Massoud Bakhshi, whose first, A Respectable Family, we recommended as “an unexpected gem” when it played in Vancouver in 2012. Yalda is another film that comes to Vancouver via this year’s Berlin International Film Festival, where it was nominated for a Crystal Bear. It also played at the Sundance Film Festival, where it won the Grand Jury prize in the “World Cinema – Dramatic” category.

The film centers around one episode of a television series, “Joy of Forgiveness,” based on the premise that each week someone convicted of a crime seeks to be forgiven by the victim or a relative of the victim. Although not an actual law, such forgiveness is encouraged in Iran under Islamic law. If forgiveness can be obtained, the criminal is typically absolved of the crime. There are now charities, celebrities (including film director Asghar Farhadi), and other forces working informally to foster forgiveness and free guilty people, though this may include a payment of “blood money” given to the person doing the forgiving. (A real TV show based on this premise, “Honey Moon,” was the inspiration for Yalda.)

In this case, a young, shy working-class woman, Maryam, who had been married to a wealthy older man, has been convicted of killing her husband. She insists, however, that it was an accident. As the film begins, Maryam’s mother brings her to the television station. The young woman is terrified and declares she does not want to participate. But since this would mean a death sentence being carried out, her mother and the production team of the show ignore her protestations and hurry her through the preparations.

Representing the victim is Mona, his daughter, who, as the title of the TV series suggests, is expected to provide the standard happy ending to the show by forgiving Maryam. Mona seems to have reasons to do so, since she would receive the blood money proffered by “Joy of Forgiving” and is planning to emigrate from Iran in the near future.

So far we seem to have a situation familiar from the films of Asghar Farhadi, with two or more people at odds who are gradually revealed to be flawed and to some degree at fault. The situation then typically ends in reluctant understanding between or among the opponents.

As the host interviews the two women, however, he shows a distinct bias toward Mona’s viewpoint. Rather than pleading her case humbly, as the television crew expects, Maryam becomes desperate and accusatory. Her exchanges with Mona grow more heated.

The producers begin to panic. As one points out, this show is occurring on Yalda, a festival held on the day of the winter solstice. The longest night of the year is believed to be unlucky, and traditionally Iranian families gather to eat, tell stories, read poetry, and generally cheer each other up through the night. Seeing a sad ending to the program would badly disappoint the audience.

Telling his story in what is essentially continuous time and at a brisk pace, Bakhshi starts out by sticking closely to Maryam, building up considerable sympathy for her as everyone ignores her pleas and bosses her around. Once the program begins, the increasing hostility of Mona generates a suspense that is well maintained up to the final twists of the ending–twists showing that Bakhshi is not going for a Farhadi-style resolution.

The script is tightly constructed and engrossing, so much so that one could imagine a Hollywood remake–if a plausible legal situation could be devised as the premise.

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs (2020)

The Shepherdess and the Seven Songs (director Pushpendra Singh) also was shown at the Berlin festival, in its Encounters section. It also won best director in the “Young Cinema Competition (World)” at the online competition for this year’s cancelled Hong Kong International Film Festival.

The film begins with a young man, Tanvir, struggling to lift and shoulder a heavy stone, a traditional test for a prospective husband among a tribe to which whom the beautiful shepherdess of the title, Laila, belongs. Soon a title is superimposed: “Song of Marriage,” the first of the seven songs. These songs are sung over the action–unsubtitled, unfortunately–and give a sense of the story taking place in some old folk tale. (Indeed, a title in the credits declares that the film is “Based on a Rajasthani folk-tale by Vijaydan Detha,” a well-known twentieth-century author of numerous such short stories.)

The fact that the tribes cook over open fires and follow what seem to be old traditions reinforces this impression, until a night scene where some of the men wield LED flashlights. Another title, “Song of Migration,” leads to a the journey of the nomadic tribe into which Laila has married herding their large flock toward the village that is their home base. They pass along modern highways, moving aside for traffic to pass, through landscapes that provide beautiful shots (see the top of this entry). This stretch of the film is lyrical and captivating, thoroughly drawing the spectator into the film.

Abruptly another modern touch, a radio carried by one of the men, thrusts the action into the troubled politics of the present. A newscaster declares, “In the Kashmir Valley protests against Article 5A have escalated.” Two protestors, he says, have been killed. The reference is to Pakistan and India’s dispute over control of Kashmir, and the Kashmiri struggle for independence from both. Laila, it later is revealed, is Kashmiri, while Tanvir’s tribe lives in an area controlled by India.

Laila’s beauty soon attracts the attention of the local Station-master and his subordinate, Mushtaq. They hint that as a Kashmiri she might possibly be a terrorist. This accusation comes to nothing, and Mushtaq’s clumsy attempts to seduce Laila lead to a switch in tone. A series of episodes, each a separate “song,” follow Laila promising trysts with him and then bringing her husband along on a pretext. Mushtaq’s continued gullibility in trusting that each new assignation is made in earnest lends a farcical comic touch to this lengthy passage of the film. At the same time, however, Laila is testing whether her husband, strong enough to lift the stone and win her as his bride, has the moral power to defend her rather than currying favor with Mushtaq by turning a blind eye to his designs on Laila.

I felt that the last portion of the film ran out of the energy it had sustained so well, since Laila is strong enough to turn her back on two unacceptable men but has no apparent sense of where to turn once she has done so. Still, overall The Shepherdess is beautifully filmed, as the frames at the top of this section and of the entry demonstrate. It also tells a thoroughly absorbing story.

So far David and I have reported on six films from this year’s Vancouver festival. Already it has become clear that our accumulated experiences from past years have allowed us to trace the development of promising young filmmakers into great ones and to discover promising new ones whom we hope to encounter at future festivals.

Thanks to Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, Jane Harrison, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

There Is No Evil (2020).

Posted in Film comments, National cinemas: India, National cinemas: Iran |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Vancouver: Three gems from Iran and India open printable version

| Comments Off on Vancouver: Three gems from Iran and India

Sunday | September 27, 2020

Big Tech as Pac-Man: The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

DB here:

Every festival has had to adjust to COVID-19. This year the venerated Vancover International Film Festival continues with some in-person events at the VIFF Centre and the Cinematheque, but most of the screenings are done remotely. The streaming resource is available only in British Columbia and is a wonderful option for regional cinephiles.

Over the next two weeks, we’ll continue our annual tradition of covering some of the outstanding films mounted by this superb festival. As usual, we hope to guide local viewers while the event is in progress and to signal readers about upcoming releases in their territories.

Deep dives

Undine (2020).

No lyrical drone vistas, no establishing shot, no title telling us where and when we are, no voice-over trying to lure us in. Just bam, here it is, deal with it. Any movie that starts with a reaction shot in OTS (over the shoulder) of a fiercely downcast woman gets points automatically. The fact that she goes on to threaten to kill the man she’s talking to is just a bonus.

That threat, made by the protagonist of Christian Petzold’s Undine, is about the only hint that she’s capable of homicide. She seems otherwise a well-adjusted young woman free-lancing as a guide in Berlin’s Urban Development Center. As in other Petzold films, thriller conventions are invoked but suspended while a deepening personal drama emerges. At first, we tag along with Undine in her rebound-affair with Christophe, an engineer specializing in repairing underwater equipment. All is going well enough, but there are signs of trouble, particularly a near-death experience in a lake. Then, after the midpoint, tension ratchets up with two quick twists that put new pressure on Undine to take violent action.

Sorry to be so oblique, but this is one of those movies with a real plot, and since it’s eventually coming to the US, I’m avoiding spoilers. Admittedly, the last twenty minutes take off into new territory, and I found myself unable to know what to expect next. (It’s one of those movies that seems to end several times. That is often a good thing.) But the unruffled precision of Petzold’s direction, the thriftily paid-out backstory, and his gift for suspenseful storytelling mitigate the quasi-supernatural tint of the twists. I tend to see them as GOFAC (Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema), ambiguous moments that may flow from the characters’ imaginations.

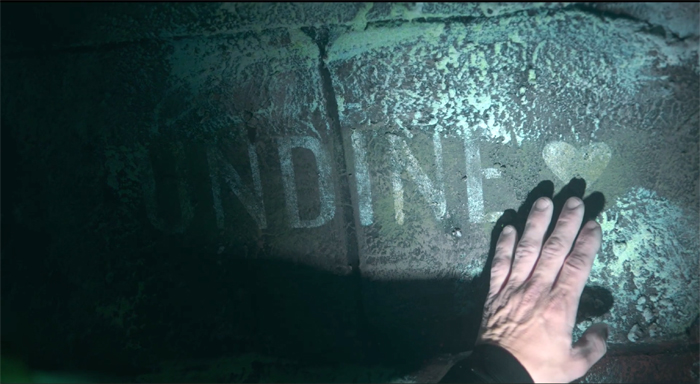

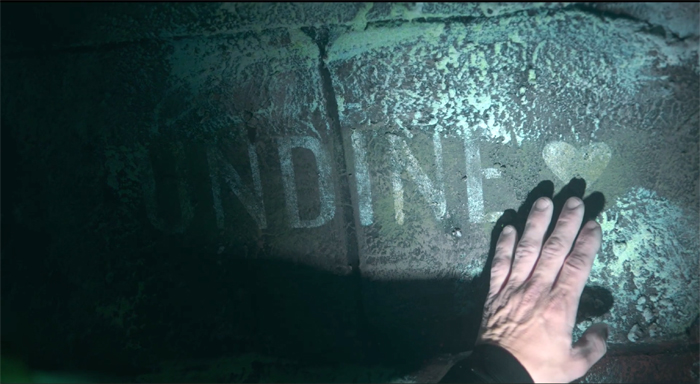

An undine is a water nymph, the heroine’s lover is a diver, her job is to lecture on the rebuilding of Berlin over the years, and his job is to explore a submerged city (which hosts a slab bearing her name). All this was for me a reminder that ambitious directors can invest genre conventions with poetic lyricism. Admirers of Barbara (2012), Phoenix (2014), and Transit (2018) will need no urging to visit a film I found completely absorbing.

A film from two billion years from now

Last and First Men (2020).

On the visual level, Jóhann Jóhannsson’s Last and First Men is a good example of what we call “abstract form” in our book Film Art. The filmmaker builds a film out of patterns of sensuous visual qualities. Everyday objects can yield these qualities (our example is Ballet Mécanique), but abstract form can also be found in unusual, even unidentifiable sources.

That’s what we get here. The shots reveal structures and textures in immense, brutal constructions of metal, stone, and cement. Are they sculptures? Totems of some bizarre religion? Remnants of blasted modernist buildings? Fragments of space ships crashed to earth? The moving camera reveals their shapes, textures, and off-kilter strains for symmetry. You lose all sense of scale: these might be the size of dinner tables or tabernacles. Most are set against the sky, alternately misty or searingly bright.

No story connects our views of these strange monuments. On the soundtrack, though, a woman’s voice recounts the history of the future. After two billion years, the narrator represents the “eighteenth species” of humans, and via telepathy she informs us of the impending end of human life on Neptune.

We never see any of those events, just the ruins calmly surveyed by the camera. Almost never does the commentary sync up with the shots. The woman’s account of future humans might at first seem to match the carved, staring blocks we see, but she goes on describe them as furry or translucent.

The disparity between description and depiction emphasizes the gap between tracks.

For most of the film, then, we have a split. The image track explores abstract, nonnarrative form. The soundtrack supplies a narrative, actually a Very Grand Narrative. The text, it’s revealed in the credits, comes from Olaf Stapledon’s 1930 science-fiction novel, Last and First Men.

There’s yet a third layer. Jóhannsson, a brilliant composer who died in 2018, gave us memorable concert music and film scores (Sicario, Arrival, The Miners’ Hymns). Along with the voice-over we hear a sometimes radiant, sometimes jarring orchestral accompaniment created by Jóhansson and electronic composer Yair Elazar Glotman. The music doesn’t cooperate much with the voice-over. As the commentary proceeds with a businesslike dryness, the music often flows and eddies on its own course.

The fact that the three channels of picture, voice, and music seldom converge actually sets your imagination free. There’s no need to see the images as illustrating the text, or the music as operatically enhancing either one. We’re allowed to keep the realms separate, or to test obscure correspondences. We can, for instance, see the expressive qualities of the shots as enduring remnants of human will–eccentric, obstinate, and obscure as it can be. The music’s alternation of drone passages, scraps of choral lyricism, and ominous rumbles might seem to chart humans’ up-and-down fate in the late Anthropocene. The narration, recited by Tilda Swinton, adds a quality of stoic dignity to the mix. And you’re invited to try out metaphors, as when cavities in what seems to be an elongated cathedral suggest eyeholes for staring across space.

The disparity of channels is enhanced by another mystery I haven’t seen mentioned in reviews. The images betray their origins on 16mm film. There are light leaks on the frame edges, specks of white suggesting dust on the negative, and even bits of grit and hair in the aperture. Perhaps you can see the hair snagged in the upper right of the image below.

These flaws have not been digitally removed. Indeed, the film’s opening moments linger on black frames flecked with white dust, priming us to watch for faults in these images.

The effect is to add an archaic quality, as if this is all found footage from long before the end recounted on the soundtrack. Since the narrator tells us that humankind goes through many near-extinctions until the big one, these relics may be from one of those future collapses–or, perhaps, from our own past, remnants of a calamity we’ve forgotten. The text speaks of “the debased rites of your religions long ago,” and those big-eyed humanoids are reminiscent of Australian aboriginal art.

In all, it’s a bleakly beautiful experiment. The film premiered with live orchestral accompaniment in the 2017 Manchester International Festival, and it must have been hypnotic. The film and soundtrack are now available on a CD/Blu-ray combination, as well as on vinyl.

Meet the New New Boss, same as the Old New Boss

The New Corporation: The Unfortunately Necessary Sequel (2020).

The scathing 2003 documentary The Corporation took seriously the idea that corporations were persons. Their behavior, considered clinically, is that of a sociopath. Now Joel Bakan and Jennifer Abbott’s followup shows how the 2008 financial crisis provoked corporations to rehabilitate. Hip CEOs admit the existence of racial bigotry, income inequality and the failures of conservative government. The solution? More corporate power. Did this make them any less dangerous?

Nope. Multinationals shape government policy as vigorously as ever, especially in the era of Trump and other demagogues. But the corporations’ new message is soft power. Posing as socially committed, emphasizing stakeholders as well as shareholders, Big Business is (a) trying to convince consumers that it’s on their side; and (b) arguing that the New Corporation will correct the shortcomings of government policy through privatization. In other words: We’ve learned our lesson. We get it. So let us run things. Besides, what choice do you have?

Bakan and Abbott shrewdly show that this ploy neatly fits an updated clinical symptom of the sociopath: “Use of seduction, charm, glibness, or ingratiation to achieve one’s ends.”

The film begins with a fascinating visit to the Davos Forum, where air-kissing one-percenters solemnly assure us that everybody wins when a corporation acknowledges the public good. The star player is Jamie Dimon, CEO of JP Morgan Chase. Having helped crush American cities in the financial crisis (and paying a derisory $13 billion fine), he is now playing rescuer by supporting the rebuilding of Detroit, to the benefit of his company’s image. The film goes on to trace how the public face of caring executives is belied by business as usual, most savagely British Petroleum’s catastrophes in Texas City and at Deep Water Horizon.

Bakan and Abbott marshall a great deal of evidence to show how the plutocracy, and especially those in the digital technology sector, have turned a market economy into a market society. For us, the role of worker-consumer redefines the other dimensions of civic life. You work without union protections and scramble to keep up. You give your personal information to Facebook, Google, and Amazon in exchange for convenience and lower costs. (The old adage holds: If something is free, the product is you.) Schools, postal delivery, war, water, and relationships are all ripe to be rendered as private enterprise. With AI algorithms, the customer-customized milieu of Minority Report is already here.

Talking heads, from Chomsky and Robert Reich to Diane Ravitch and Vandana Shiva, offer pithy critiques, and footage garnered from around the world illuminates each of the points in the Corporate Playbook. As a counterweight, later portions of The New Corporation show some pushback. Katie Porter poleaxes Mr. Dimon in a House hearing, and we glimpse AOC in her usual passionate eloquence. Still, the emphasis falls less on pols and more on citizens who struggle against corporate power.

Occupy Wall Street and the Bernie Sanders campaign are shown to be as important to the left as the Tea Party was to the right. The filmmakers give special attention to the efforts of many tough, idealistic people to run for public office. As one commenter puts it, “Even in the worst situations, people always fight.” In a remarkable passage, a dopy prankster from The Corporation is shown to have become a proud progressive after seeing the first film and joining the Sanders campaign.

The film is startlingly up-to-date, incorporating events around the George Floyd atrocity and the Black Lives Matter street actions. Some will say that the late sections drift a bit from the film’s core message of analyzing the fake social concerns of the New Corporation. But income inequality and environmental destruction, central drivers of new social movements, are invoked in corporate PR as vital concerns for companies’ new image, so the final sequences don’t seem to me tacked on. They show what real social engagement, as opposed to panting coverage in Forbes, looks like.

Where do you start? someone asks in Tout va bien. The answer: Everywhere at once. I think The New Corporation indicates that this might just work.

The three films I’ve discussed are exemplary of the strengths that have characterized the Vancouver festival for its 39 years. Here you can plunge into international auteur cinema, unusual experimental work, and documentaries committed to our noblest aspirations. Programmers Alan Franey, PoChu AuYeung, and their colleagues scour the world for provocative films, and the results have taught Kristin and me lessons about cinema we wouldn’t have learned otherwise. It’s worth noting that VIFF’s welcome to Canadian cinema has always been fruitful: The New Corporation, like its predecessor, is a British Columbia production and is featured in the festival’s ongoing True North series.

Fourteen years ago I wrote that Vancouver was the very model of a regional festival, at once deeply local and unpretentiously cosmopolitan. It still is. Take that, corornavirus! Nothing stops dedicated film lovers.

Thanks to Alan Franey, Jane Harrison, and their colleagues for their help during the festival.

A sensitive review of Undine is offered by David Hudson at the Criterion Daily.

A note on Last and First Men: In watching the film, I found myself constantly asking if these structures really existed, or whether they were CGI creations or miniatures or objects purpose-built for the film. Some reviews have revealed their secret identity, and knowing what they are does raise some interesting thematic implications. But I’m refraining from telling you because I think your first encounter with the film ought to include that mystery about what exactly you are seeing. If you want to know what they are, Google is at your service. There’s also this spoiler-filled behind-the-scenes video.

Jennifer Abbott has another documentary in this year’s festival: The Magnitude of All Things. I look forward to it.

Undine (2020).

Posted in Directors: Petzold, Experimental film, Festivals: Vancouver, FILM ART (the book), Film comments, Film music, National cinemas: Germany |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Vancouver: First sightings open printable version

| Comments Off on Vancouver: First sightings

Sunday | September 13, 2020

Careless Crime (2020)

Every September over the last three years, we’ve immensely enjoyed visiting the Venice International Film Festival. There David has participated in the Biennale College Cinema discussions with stimulating colleagues.

This year, alas, the coronavirus kept us home. But the festival did make available a selection of fourteen films online. Each could be viewed for five days at the very fair price of $6 per film. (Here is the array of choices. A few are still available, so hurry.)

We took advantage of this opportunity and watched several titles. Here are our thoughts about three of them. (The first section is by David, the second by Kristin.) We hope that if you get a chance to see them on the big screen or at home you’ll investigate.

GOFAC is back! Actually, it never went away

The Art of Return (2020).

Back in the late ’70s and early ’80s, I tried to analyze the conventions governing a certain approach to moviemaking, the one that’s come to be called “art cinema.” My examples were films by Fellini, Antonioni, Bergman, the French New Wave, and many of their contemporaries.

In the years afterward, I revisited the ideas and asked: Are these conventions still in force? My conclusion in an updated version of the essay in Poetics of Cinema (2008) was: yes. From Fassbinder to Wong Kar-wai, from Distant Voice, Still Lives (1988) to Maborosi (1995) and beyond, we can find art-cinema principles of storytelling and style. In that book, the extended example was Varda’s Vagabond (Sans toit ni loi, 1985), while other chapters traced how this tradition mobilized new options like forking-path narratives (e.g., Run Lola Run, 1998) and network narratives (e.g., Les Passagers, 1999). There’s a pirated pdf of the updated essay here.

Since then, it’s been fascinating to watch a younger generation of filmmakers take up this tradition. Every festival I visit furnishes examples, as you can see from our entries on this site. I had the same sense when watching Pedro Collantes’ The Art of Return (El Arte de Volver) and Christos Nikous’ Apples (Mila). Good Old-Fashioned Art Cinema is still with us.

The Art of Return is centered on Noemi, who returns to Madrid after six years in New York. She has come home to audition for a role in a telenovela, and in the course of twenty-four hours she encounters several people from her past. The film consists of a series of duologues, as Noemi visits her dying grandfather, quarrels mildly with her sister, reconnects with her actor friend Carlos, and learns through another friend what became of Alberto, her ex.

What makes The Art of Return a prototypical art film is the way sheer chronology replaces a strongly causal plot. Apart from attending her audition, Noemi doesn’t have a strong goal; she drifts from one encounter to another. Most of these long scenes are devoted to discussions of her past, with hints about why she left Spain, as well as reactions of others to her personality. The task for a filmmaker using this episodic structure is to create patterns of revelation for us and for the character.

We need backstory about Noemi, and Collantes shrewdly avoids supplying flashbacks that would supply that. Instead, her past is refracted through the reactions of characters who are reconnecting with her, after much that has happened in their own lives. Gradually we assemble a fragmentary sense of what impelled her to go to New York. This revelation of the past is in effect the “under-plot” of the action.

Along with this pattern of revelation for us there are revelations for Noemi herself. She learns about her friend Ana’s floundering artistic ambitions, about her ex Alberto, about Carlos’ judgments of her. In an art film, the keenest revelation for the protagonist comes through an epiphany, a moment in which the character–sometimes mysteriously–gains self-awareness.

The crucial epiphany in The Art of Return, I think, occurs in a quiet scene in the park, among the trees that Noemi feels have been sculpted by a mystical force. By chance–again–she sees something that gives her the strength to make a decision. Yet in a typical art-cinema move, the outcome of that decision is withheld from us, suspended in a shot reminiscent of The 400 Blows (1959).

Collantes skillfully creates a firm pattern, with the opening scene symmetrically balanced by the final audition. In between, as in La Dolce Vita (1960) and Angela Schanelec’s Passing Summer (2000), the protagonist’s encounters provide a sampling and survey of life in the city, from the bohemian artists to the Romanian migrant community. A College selection, The Art of Return has already been acquired for theatrical distribution in Spain and other territories.

Apples (2020).

Because the art-cinema tradition minimizes a goal-directed plot, it often creates patterning through routine actions that are modified across the film. The changes in the routines reveal changes in a character or a situation. A vivid example is given in the Greek film Apples. After we’ve seen our protagonist regularly buy and eat apples (lots of ’em), he learns from a grocer that apples sharpen memory. He immediately switches to oranges. What psychology can justify this strange piece of behavior?

We understand it completely, because what has gone before has created a compelling context. The era is vaguely pre-digital, though there are some anachronisms. In the midst of an epidemic of amnesia, the poker-faced Aris is taken to a clinic for memory recovery. His doctors have created an experimental technique to give him a new life by reenacting routines of childhood, adolescence, and young manhood. As he rides a bike, fishes in a stream, visits a costume party, and goes to a dance club, he records his actions on Polaroids. These will fill an album and serve as replacement memories.

So Aris has a goal, albeit a diffuse one. We haven’t been told his overall program, so we are left to slowly figure out the rationale behind his dressing up as an astronaut or getting a lap dance. The film’s narration is almost as laconic as its protagonist, although a couple of scenes with his doctors show some sardonic humor. They eat his cooking and ignore the pathos of his situation while also, probably, misdiagnosing him.

Crucially, his retraining regimen intersects with that of another amnesiac, a woman further along in the program. Their relationship gives the film a romantic subplot, as well as its two most exuberant scenes: a dance to “Let’s Twist Again,” in which Siri seems to suddenly recover muscle memory, and a drive that spurs him to sing along with “Sealed with a Kiss.” (Hints about the under-plot give these scenes a dose of mystery and ambiguity–two more appeals of art-cinema storytelling.) All of this takes place before the apples-to-oranges shift, which in this context becomes as dramatic a twist as one would find in a thriller.

Shot and paced with extraordinary rigor in the 4:3 format, Apples is a perfect example of how GOFAC can create a distinct blend of curiosity, surprise, humor, and suspense. The film’s revelations in the final stretch are carried out as unemphatically as everything else, lending the character’s secrets an austere dignity. Apples has been eagerly acquired for many territories, and the director, who worked with Yorgos Lanthimos on Dogtooth, is preparing an English-language project. It will be, he hopes, “more accessible/mainstream.” Not entirely, I hope.

A carefully artful Iranian film

Careless Crime (2020).

Back in 2014, we were introduced to the strange world of Iranian director Shahram Mokri with his second feature, Fish and Cat. It’s a 139-minute single-take movie with a twisty plot in which the camera runs into separate groups of people in a rural lake area, with events starting to repeat from different points of view as the camera circles back on its route. We saw it in Vancouver, but it had premiered in the Orrizonti program at the Venice International Film Festival in 2013; it won a special prize “For Innovative Content.”

This year Mokri was back in the Horizonti thread with his third feature, Careless Crime. This time Mokri didn’t win a Festival prize, but the film received a FIPRESCI award for Best Screenplay.

Careless Crime is even trickier than Fish and Cat. It’s one of those puzzling films that requires the spectator to figure out the time frames of the different plot threads–and indeed how many times frames there are–and keep track of many characters. It’s a bit like Lazlo Nemes’ Sunset in the way it demands that the viewer constantly keep on the alert for the most fleeting or oblique clues as to what’s going on. (It’s interesting that Nemes and Mokri both have a penchant for lengthy tracking shots following a character closely from behind, as in the frame above.) Apples is another film that provides only a few subtle clues abut a major plot premise that eventually provides a twist at the end

There are two major plotlines. A group of four scruffy men plan to set fire to a crowded cinema as a political protest. Their actions recall an actual event that was the inspiration for the story. In 1978 a group of four arsonists set fire to the Cinema Rex in Abadan, causing the deaths of over 400 people because the exits were blocked.The event is credited with having launched the Iranian Revolution of 1979.

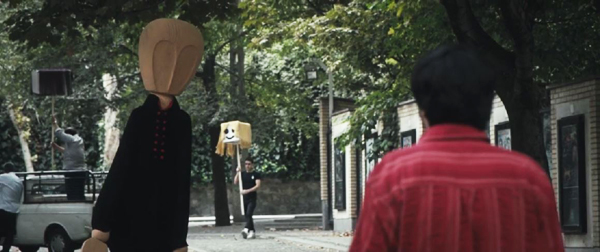

We follow the four men as they carry out inept preparations for their attack on the cinema. The group includes Faraj, a sad-sack who spends much of the early part of the film trying to get the nerve pills to which he is addicted. He tracks down a dealer who happens to be an employee at the local cinema museum and who is dressed in a large puppet costume, from the depths of which he digs out the precious bottle for Faraj.

The second plot involves a small, equally inept group of soldiers who have been sent to deal with an apparently unexploded missile deep in the countryside (see top). Contradictory information suggests that the missile landed some time ago and has been defused or that it landed the day before and needs urgent attention. Instead the men wander up into a local tourist area where two college girls are setting up an outdoor screening of the classic 1974 Iranian film, The Deer. This happens to be the film that had been screening at the Cinema Rex when the 1978 arson attack occurred. But the soldiers neglect their duty to solve the missile problem and spend their time waiting to see the young women’s film to find out if they are up to something nefarious. Thus two “careless crimes” may be involved. The the relationship between the two plotlines only becomes apparent late in the film.

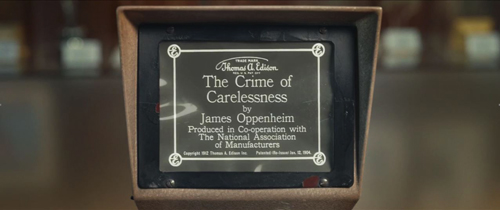

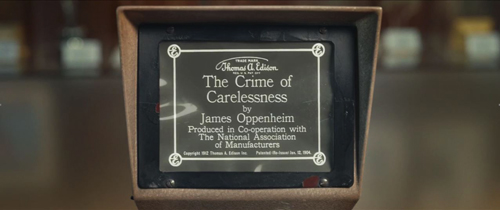

An obsession with cinema runs through both plots. The cinema targeted by the terrorists is apparently attached to the nearby museum and shows mostly art films, as is suggested by the posters for classic films that decorate the lobby. Young patrons and supporters of the cinema who hang around waiting for the show to start mention repeatedly that a friend has written an essay on The Deer, and we glimpse a poster for Kiarostami’s Close-Up. At one point Faraj, seeking the drug-dealer at the museum, sees a vintage film playing on an editing table.

It’s a 1912 Edison film, The Crime of Carelessness, in which poor safety conditions and a carelessly dropped cigarette led to a disastrous mill fire. At the end, a title in Farsi comes up, describing not the action of the silent film just shown but the 1978 Cinema Rex fire.

As all this suggests, there’s a good deal of magical realism in Careless Crime. At one point a single long take meanders around the open-air setting for the girls’ screening, picking up the same actions and dialogue repeated from different angles. During Faraj’s search for the drug-dealer, a museum employee guides him through the museum and its basement, again all in a single moving take. The seemingly endless basement is shot entirely against a black background, though at one point images of the two seemingly accompany them in the background.

Despite the grim subject matter, as in Fish and Cat, there is a good deal of self-conscious humor in Careless Crime. Little jokes are made about movies, and especially arty ones, as when a minor couple in the targeted cinema waits for the film to start. The woman looks at the screen (perhaps at a trailer?) and remarks, “I hate any film that has this laurel sign on it.” The reference is to one of the primary institutions of the international art cinema:

Is Mokri twitting the festival for not having chosen to show his films? As is now clear, his film’s repeat presence at Venice turned out to be an advantage in the long run. Although Careless Crime did not win a prize in the Horizonti competition, outside the official festival it received the FIPRESCI award for the best screenplay. Perhaps, when it finally becomes possible to return to the VIFF in person, we will see the next Mokri film and struggle not to be puzzled.

Thanks, as ever, to Alberto Barbera, Paolo Lughi, Savina Neirotti, Peter Cowie, and Michela Lazzarin for their assistance this year and in the past.

You can watch an extract of the Biennale press conference for Apples. The director discusses it in this Variety interview.

Our earlier entries on the Venice festival are here.

Apples (2020).

Posted in Art cinema, Festivals: Venice, National cinemas: Greece, National cinemas: Iran, National cinemas: Spain and Portugal |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice, virtually open printable version

| Comments Off on Venice, virtually

Sunday | August 30, 2020

Tiger on Beat (1988).

DB here:

Simple equipment includes, but is not limited to, knives, pistols, shotguns, ropes tied to shotguns, surfboards, chainsaws, etc.

Herewith another attempt to brighten your days with a choice film sequence that never fails to bring a foolish grin to my face. Apologies as ever to Ken Jacobs for my swiping his title.

Tiger on Beat (aka, but less pungently, Tiger on the Beat, 1988) is prime Hong Kong showboating. This final scene assembles some of the greats—Chow Yun-Fat, Gordon Liu Chia-Hui, Chu Siu-Tung (too little to do)–and near-greats like Conan Lee Yuen-Ba, who gets points for heedlessly executing the stunts Chow and Chow’s doubles can’t. Lau Kar-Leung (aka Liu Chia-Liang), one of Hong Kong’s finest directors, imbues both the staging and the editing with the crisp, staccato rhythm that this tradition made its own, and that few American directors have ever figured out. (It’s a long clip, so it may take a little time to load. In addition, our Kaltura operation is having problems, so you may want to try different browsers.)

Come to think of it, this little-stabs entry contains some fairly big stabs of its own.

The whole film is worth a look. Opening scenes feature Chow in outrageous threads, the very opposite of a cop in plainclothes, and there’s a fine car chase in which many risk life and limb. But this sequence, lit high-key so that every splash of saturated color pops, is for me the highlight, a tour de force of action cinema. Probably not for the kids, but what do I know about kids?

Sequences like this were what drove me to teach Hong Kong film and write Planet Hong Kong. They also impelled Stefan Hammond and Mike Wilkins to write Sex and Zen and a Bullet in the Head (1996), the most deeply knowledgeable fanguide to this glorious cinema. Stefan followed it up with Hollywood East: Hong Kong Movies and the People Who Made Them (2000). Now Stefan and Mike have effected a merger of these and updated and expanded them. They’ve also recruited a band of other Guardians of the Shaolin Temple: Wade Major, Michael Bliss, Jeremy Hansen, Jude Poyer, David Chute, Dave Kehr, Andy Klein, Adam Knee, Jim Morton, and Karen Tarapata.

The result is another indispensable volume, More Sex, Better Zen, Faster Bullets: The Encyclopedia of Hong Kong Film. The recommendations are sound, the plot synopses are nearly as much fun as the movies, and the authors have wisely retained chapter titles like “So. You think your kung fu’s. . . pretty good. But still. You’re going to die today. Ah ha ha ha. Ah ha ha ha ha ha.”

They weigh in on today’s sequence: “This gory Armageddon-duet consistently scores on Top Ten End-Battle Lists among HK film aficionados.” Makes me even more confident to recommend it to you. They add that the credits music is “a hard-rocking theme song by HK power diva Maria Cordero.” So I let it run.

I analyze this and other action sequences in this blog entry. An appreciation of Lau Kar-Leung is here.

For more little stabs, check out earlier entries in this series.

Chow Yun-Fat gets his daily dose of egg yolks (Tiger on Beat).

Posted in Books, Directors: Lau Kar-leung, Film technique: Editing, Film technique: Staging, Little stabs at happiness, National cinemas: Hong Kong, PLANET HONG KONG: backstories and sidestories |  open printable version

| Comments Off on Little stabs at happiness 5: How to have fun with simple equipment open printable version

| Comments Off on Little stabs at happiness 5: How to have fun with simple equipment

|